Abstract

Objective

To evaluate whether obese patients overestimate or underestimate the level of respect that their physicians hold towards them.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of data from questionnaires and audio-recordings of visits between primary care physicians and their patients. Using multilevel logistic regression, we evaluated the association between patient BMI and accurate estimation of physician respect. Physician respectfulness was also rated independently by assessing the visit audiotapes.

Results

Thirty-nine primary care physicians and 199 of their patients were included in the analysis. The mean patient BMI was 32.8 kg/m2 (SD 8.2). For each 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI, the odds of overestimating physician respect significantly increased [OR 1.32, 95%CI 1.04–1.68, p=0.02]. Few patients underestimated physician respect. There were no differences in ratings of physician respectfulness by independent evaluators of the audiotapes.

Conclusion

We consider our results preliminary. Patients were significantly more likely to overestimate physician respect as BMI increased, which was not accounted for by increased respectful treatment by the physician.

Practice Implications

Among patients who overestimate physician respect, the authenticity of the patient-physician relationship should be questioned.

Keywords: Obesity, patient-provider, respect

1. Introduction

A core element of the patient-physician relationship is respect, which has been defined as “the recognition of the unconditional value of patients as persons” [1]. Beach et al showed that physician respect varies across patients [2]. The same study found that physicians exhibited different communication behaviors during encounters with patients whom they respected, such as sharing more information and having a more positive emotional affect [2]. Although the philosophical ideal of respect should be independent of a patient’s personal characteristics, studies have shown that increased patient body mass index (BMI) is negatively associated with physician respect [3] and multiple studies document health professionals’ overall negative regard towards patients with obesity [4–9].

Despite negative provider attitudes, other studies find that obese patients are satisfied with their healthcare providers [10–13]. These paradoxical findings may result from patients’ inability to accurately perceive providers’ negative regard. Societal discrimination towards obese persons is common in work, educational and social settings [14–15]. Therefore, we theorize that obesity may alter a person’s ability to accurately perceive the attitudes of others during interpersonal interactions, either through desensitization or over-sensitization to disrespectful behaviors. For example, if an obese patient is desensitized to disrespectful behaviors, then he/she may interpret biased treatment from their physician as normal, and consequently overestimate physician respect. Conversely, a patient who has heightened awareness of any disrespectful attitude may underestimate physician respect. This idea of inaccurate estimation of physician attitudes among obese patients is supported by work from Brandsma [16]. In Brandsma’s study, dyads of physicians and their obese patients were recruited to participate in a survey about general attitudes regarding obesity. When physicians’ attitudes were compared to how their patients perceived the physicians’ views, the patients perceived less positive attitudes than those reported by physician. This survey asked questions regarding attitudes towards obese individuals in general, and did not ask about physician attitudes toward the patient surveyed. To date, no studies have compared patient and physician perspectives to evaluate how obesity impacts the patient’s ability to accurately estimate his/her physician’s level of respect.

Obese patients’ ability to accurately estimate their physicians’ attitudes may have implications regarding the authenticity of these patient-physician relationships. Beach and Inui conceptualized authenticity as the physician not only acting respectfully towards a patient, but also actually having respect for that patient [17]. Arnason described an authentic conversation as when patient and physician participate in a dialogue in which the subjectivity of both is respected [18]. While the association between authenticity and patient outcomes has yet to be evaluated, authenticity is considered an ethical principle in patient-physician relationships [17–18]. Authentic conversations may facilitate shared decision-making and reduce alienation between patients and physicians [18]. If obese patients are not able to accurately estimate their physicians’ regard, then the authenticity of these patient-physician relationships may be compromised.

In this study, we aimed to justify our theory that obesity alters one’s ability to accurately perceive the attitudes of others during interpersonal interactions by examining whether patients’ weight influences their ability to accurately estimate levels of physician respect. We hypothesized that higher patient BMI would be associated with both overestimation and underestimation of physician respect. In addition, we assessed the level of physician respect as rated by an independent third party, in order to assess differences in physician respectfulness that may have contributed to over- or underestimation of respect.

2. Methods

2.1 Study design, subjects, and setting

We carried out a cross-sectional study by performing a secondary analysis of data from the baseline visit of the Patient-Physician Partnership Study (Triple P Study). The Triple P Study was a randomized controlled trial of a patient-physician communication intervention to improve patient adherence and blood pressure control [19]. The study included urban, community-based primary care physicians seeing their established patients for routine follow up. Primary care physicians were recruited from 15 practices in Baltimore, MD between January 2002-January 2003. Adult hypertensive patients were recruited from the participating physicians’ panels between September 2003-August 2005. Additional details regarding patient and physician recruitment have been published previously [19]. The Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board approved this study. Patients and providers provided written consent prior to inclusion in the study.

2.2 Data collection methods for the parent study

At time of physician enrollment into the Triple P study, physicians completed a survey that included demographic information and medical practice characteristics. At time of patient enrollment, patients completed a survey that included demographic information and health status. A single outpatient encounter was audio-recorded for each patient at baseline. These visits were a part of ongoing clinical care, and not specifically scheduled for the study. Immediately following the audio-recorded encounter, both the patient and physician completed post-visit questionnaires to assess their attitudes about the visit and perceptions of one another. Post-visit physician questionnaires assessed the physician’s regard for that patient including respect, while post-visit patient questionnaires assessed how the patient felt regarded by his/her physician including level of respect. While the patient and physician questionnaires for the Triple P study contained multiple questions assessing different attitudes and perceptions, for this secondary data analysis, we used only one physician question and one patient question that assessed level of physician respect.

2.3 Selection of study sample

The parent study included 42 physicians and 279 of their patients. We excluded from this analysis any encounters where the outpatient visit was not audio-recorded (n=35), patients lacked documentation of BMI (n=9), or the patient and/or physician did not complete the question assessing the level of physician respect for the patient (n=36). Our final sample included 39 physicians and 199 of their patients.

2.4 Primary analyses

2.4.1 Outcome measure

The primary outcome was the accuracy of patient-estimated level of physician respect. To our knowledge, only one previous study has examined this concept of accuracy of patient-estimated level of physician respect [2]. In that study, Beach et al constructed this variable by comparing the amount of respect the physician reported with the level of respect the patient perceived.

In order to create this variable, we first needed to evaluate the level of physician-reported respect. In the previous study, Beach et al asked physicians to respond to the statement, “Compared to other patients, I have a great deal of respect for this patient,” on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree) [2]. They then created three categories of physician-reported level of respect. The categories were high level of respect (strongly agree), medium level of respect (agree), and low level of respect (neutral or disagree). Beach et al chose this categorization because so few physicians disagreed and no physician strongly disagreed that they had respect for their patient [2]. When the Triple P study was designed, the investigators planned to evaluate physician respect using the same statement and scale as in the Beach study. However, pilot testing with a group of primary care physicians found the wording of this question and scale unacceptable. The investigators changed the final phrasing of the question and scale responses in order to address these concerns. Physicians answered the question, “How much respect do you have for this patient?” on a 5-point Likert scale (much more than average, more than average, average, less than average, much less than average). When we examined the distribution of responses from the physicians in our study, we found 50 reports of ‘much more than average,’ 73 reports of ‘more than average,’ 72 reports of ‘average,’ and 3 reports of ‘less than average.’ No physicians reported ‘much less than average.’ We conceptualized that responses of ‘much more than average’ and ‘more than average’ indicated the physician having more than average respect for the patient. As a result, we decided to dichotomize physician-reported respect as “high” (much more than average or more than average) versus “low” (average or less than average) for the main analysis.

The second step needed to create this variable was to examine the patient-estimated level of physician respect. In the previous study, Beach et al asked patients to respond to the statement, “My doctor has a great deal of respect for me,” on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree) [2]. They then created three categories of patient-estimated level of physician respect. The categories were high (strongly agree), medium (agree), and low (neutral or disagree). In the Triple P study, the investigators used the same question and scale responses as Beach et al [2]. When we examined the distribution of responses, we found that 60 patients ‘strongly agreed,’ 134 patients ‘agreed,’ and 4 patients were ‘neutral.’ No patients disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement. We conceptualized that both responses of strongly agree and agree with the statement indicated the patient perceiving that the physician had a great deal of respect for him/her. Therefore, we dichotomized patient-estimated physician respect as “high” (strongly agree or agree) versus “low” (neutral) for the main analysis.

The final step in creating this variable was to compare the parallel categories of physician-reported and patient-estimated respect. We defined accurate patient estimation of physician respect when what the patient perceived equaled what the physician reported; otherwise the pair was identified as either overestimating or underestimating physician respect.

2.4.2 Independent variable and covariates

The independent variable of interest was BMI. BMI was calculated from height and weight obtained from the medical record for each patient. For analyses, we scaled BMI by 5 kg/m2. Based on prior studies, our primary covariates of interest were patient age and physician familiarity with the patient. Both of these measures have been previously associated with physician level of respect [2–3]. Age was modeled as a continuous variable. Physician familiarity with the patient was assessed via a question on the physician post- visit questionnaire that asked, “How well do you know this patient?” Physicians responded on a 5-point Likert scale (very well, moderately well, somewhat, slightly, not at all). When examining the distribution of responses, there were 74 responses of ‘very well,’ 93 responses of ‘moderately well,’ 22 responses of ‘somewhat,’ 4 responses of ‘slightly,’ and 4 responses of ‘not at all.’ We dichotomized this variable as “knows well” (very well or moderately well), versus “knows less well” (somewhat, slightly, or not at all).

2.4.3 Statistical analyses

All analyses were performed using STATA 11.0 (College Park, TX). We performed descriptive analyses of all variables. To examine the association between BMI and inaccurate estimation of physician respect, we used multilevel logistic regression analyses. These models employed random intercepts to account for clustering of patients by physician. All models were adjusted for patient age and physician familiarity with the patient, as described above [2, 3]. We refer to this model as “main analysis” in our results.

2.4.4 Sensitivity analyses

We also performed sensitivity analyses using different categorizations of physician-reported and patient-estimated physician respect. Similar to the categories created by Beach et al [2], we categorized physician responses as “high” (much more than average), “medium” (more than average), and “low” (average or less than average). Also similar to the categories created by Beach et al [2], we categorized the patient responses as “high” (strongly agree), “medium” (agree), and “low” (neutral). We then defined accurate patient estimation of physician respect in two ways. First, we defined accurate patient estimation of physician respect when what the patient perceived equaled what the physician reported; otherwise the pair was identified as either overestimating or underestimating physician respect. This method was modeled after the strategy used by Beach et al [2]. Second, we created a more restrictive definition using the above categories. Overestimation of respect was defined only when a patient perceived a “high” level of physician respect but the physician reported a “low” level of respect. Underestimation of respect was defined only when a patient perceived a “low” level of physician respect but the physician reported a “high” level of respect. These categories were conceptualized to be true discrepancies in estimation of respect. All other combinations were identified as accurate estimation. These alternate measures of the primary outcome were also used in the multilevel logistic regression analyses described in the section above to examine the association between BMI and inaccurate estimation of physician respect. We refer to these models as “sensitivity analysis A” and “sensitivity analysis B” in our results, respectively.

2.5 Secondary analysis

In addition to the primary analysis, we assessed how an independent rater perceived the level of physician respect using the audio-recordings of all patient-physician encounters. We used the Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS) to assess the audio-recordings. RIAS is a coding system for the assessment of patient-physician communication with established reliability and validity [20]. Two trained RIAS coders listened to and evaluated the audiotape dialogue for several aspects of global affect including respectfulness of the physician. Coders were asked to base the global affect ratings on their own life experiences and understanding. For respectfulness, coders began with an anchor point of 3, then could assign down to a 1 or 2 for those visits where they sensed less respect or could assign up to a 4 or 5 for higher respectfulness. The reliability of the global affect ratings was calculated as percent agreement. As per RIAS protocol, assignments were considered “in agreement” if both coders rated the affect within one point of each other [21]. The agreement between coders for respectfulness was 80%. We incorporated this independent evaluation in order to address concerns that patients who underestimated respect actually saw physicians who behaved less respectfully, and vice versa, patients who overestimated respect saw physicians who behaved more respectfully.

We examined the level of respectfulness noted by coders across the categories of patient estimation of physician respect. To evaluate the association between estimation of physician respect and coder-rated level of physician respect, we used a multilevel linear regression analysis to account for clustering of patients by physician. These models employed random intercepts to account for clustering of patients by physician. Similar to the primary analysis, we adjusted these models for patient age and physician familiarity with the patient.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive characteristics for 199 patients in the study sample. Overall, the mean patient BMI was 32.8 kg/m2 (SD 8.2). Table 1 displays the distribution of patient BMI according to the NIH standard classifications of weight. The majority of patients were women (63%) and black (61%). Table 2 shows the descriptive characteristics for the 39 physicians in the study sample. The majority of physicians were female (54%).

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of patients in the study sample

| Patients (n=199) | |

|---|---|

| Age in years | |

| Mean | 61.5 (SD 12.0) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 126 (63%) |

| Race | |

| Black | 121 (61%) |

| Non-black | 78 (39%) |

| Body mass index in kg/m2 | |

| Normal (≤24.9) | 28 (14%) |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9) | 57 (29%) |

| Class I obesity (30.0–34.9) | 51 (26%) |

| Class II obesity (35.0–39.9) | 30 (15%) |

| Class III obesity (≥40.0) | 33 (17%) |

| General health status | |

| Mean PCS SF-12 | 39.7 (SD 12.4) |

| Depressive symptoms | |

| CES-D score ≥ 16 | 59 (31%) |

| Education | |

| ≥ High school graduate | 136 (68%) |

| Physician familiarity with the patient | |

| Knows well | 167 (85%) |

| Knows less well | 30 (15%) |

SD standard deviation; PCS SF-12 physical component score of the Short Form-12; CES-D Center for Epidemiologic Studies - Depression Scale.

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of physicians in the study sample

| Physicians (n=39) | |

|---|---|

| Age in years | |

| Mean | 42.9 (SD 8.8) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 21 (54%) |

| Race | |

| Black | 12 (31%) |

| White | 16 (41%) |

| Other | 11 (28%) |

| Years in practice | |

| Mean | 11.3 (SD 7.8) |

SD standard deviation

In the main analysis, 124 patients accurately estimated respect (62%), 73 overestimated physician respect (37%), and 2 underestimated physician respect (1%). Table 3 shows the number of patients in each respect estimation category by BMI classification. Given the small number of patients who underestimated physician respect, we only compared patients who accurately estimated physician respect to those who overestimated physician respect in all regression models. We found that for each 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI, the odds of overestimating physician respect significantly increased [OR 1.32, 95%CI 1.04–1.68, p=0.02]. This result was obtained from the multilevel logistic regression models adjusted for patient age and physician familiarity with the patient.

Table 3.

Number of patients in each respect estimation category by BMI classification for main analysis

| Normal Weight BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 |

Overweight BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2 |

Class I Obesity BMI 30–34.9 kg/m2 |

Class II Obesity BMI 35–39.9 kg/m2 |

Class III Obesity BMI ≥40 kg/m2 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Underestimation | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Accurate estimation | 22 | 35 | 34 | 18 | 15 |

| Overestimation | 6 | 21 | 16 | 12 | 18 |

Table 4 demonstrates the number of encounters according to physician reported and patient perceived level of respect used in the main analysis and the two different sensitivity analyses. Table 5 displays the results from our sensitivity analyses. We compared the three different ways to define the outcome variable of patient-estimated physician level of respect. As displayed in Table 5, the number of patients that fall into the different categories of respect estimation varies substantially between the three analyses. Of note, sensitivity analysis B has very few people who fall into the overestimation group (12%) and even fewer that fall into the underestimation group (<1%). In the main analysis and in sensitivity analysis A, we found that the odds of overestimating physician respect significantly increased for each 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI [Main Analysis OR 1.32, 95%CI 1.04–1.68, p=0.02; Sensitivity Analysis A OR 1.38, 95%CI 1.05–1.83, p=0.02]. However, in sensitivity analysis B, we found that the odds of overestimating physician respect increased non-significantly for each 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI [Sensitivity Analysis B OR 1.17, 95%CI 0.81–1.58, p=0.48]. The direction of effect was the same for sensitivity analysis B; however, the effect size and statistical significance were attenuated as compared to the main analysis and sensitivity analysis A.

Table 4.

Distribution of number of encounters by physician reported and patient estimated levels of respect for three different analyses

| Main Analysis* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Physician reported level of respect | |||

| Patient estimated level of respect | Low | High | |

|

|

|||

| Low | 2 | 2 | |

| High | 73 | 122 | |

| Sensitivity Analysis A** | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician reported level of respect | ||||

| Low | Medium | High | ||

|

|

||||

| Patient estimated level of respect | Low | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Medium | 50 | 47 | 38 | |

| High | 23 | 25 | 12 | |

| Sensitivity Analysis B*** | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician reported level of respect | ||||

| Low | Medium | High | ||

|

|

||||

| Patient estimated level of respect | Low | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Medium | 50 | 47 | 38 | |

| High | 23 | 25 | 12 | |

Black shaded areas represent encounters where patients accurately perceived their physicians level of respect. Gray shaded areas represent encounters where patients overestimated physician respect. White shaded areas represent encounters where patients underestimated physician respect.

The variables are dichotomized and then used to define accurate estimation, overestimation, and underestimation.

The variables are categorized and then used to define accurate estimation, overestimation, and underestimation, which were modeled after Beach et al [2].

The variables are categorized and then used to create more restrictive definitions of overestimation and underestimation, as detailed in section 2.4.4.

Table 5.

Comparison of results from three different analyses

| Main Analysis* | Sensitivity Analysis A** | Sensitivity Analysis B*** | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

|

Sample sizes

| |||

| Accurate estimation | 124 (62%) | 61 (31%) | 175 (88%) |

| Overestimation | 73 (34%) | 98 (49%) | 23 (12%) |

| Underestimation | 2 (1%) | 40 (20%) | 1 (<1%) |

|

| |||

|

Association of BMI per 5 kg/m2 with overestimation of physician respect****

| |||

| Unadjusted OR | 1.41 (1.13–1.76, p<0.01) | 1.47 (1.13–1.92, p<0.01) | 1.17 (0.88–1.57, p=0.29) |

| Adjusted OR | 1.32 (1.04–1.68, p=0.02) | 1.38 (1.05–1.83, p=0.02) | 1.13 (0.81–1.58, p=0.48) |

In the main analysis, the variables are dichotomized and then used to define accurate estimation, overestimation, and underestimation.

In sensitivity analysis A, the variables are categorized and then used to define accurate estimation, overestimation, and underestimation. All aspects of this strategy are modeled after the methods used by Beach et al [2].

In sensitivity analysis B, the variables are categorized and then used to create more restrictive definitions of overestimation and underestimation. Please see section 2.4.4 for additional details.

Odds ratios calculated using multilevel logistic regression accounting for clustering by physician. Adjusted analyses account for patient age and physician familiarity with the patient.

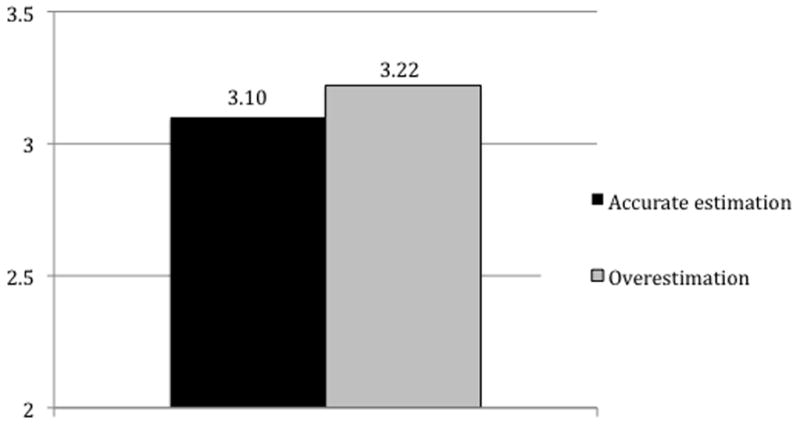

Figure 1 shows the results of the adjusted multilevel linear regression analysis of mean ratings of physician respectfulness by coders according to the categories of either accurate patient estimation of physician respect or patient overestimation of physician respect. These models were also adjusted for patient age and physician familiarity with the patient. The level of respectfulness noted by coders did not differ between accurate estimation and overestimation of physician respect. There were no differences in the mean score assigned by the coder when comparing the group who accurately estimated respect with those who overestimated respect [β 0.12, 95%CI −0.02–0.25, p=0.09].

Figure 1. Coder ratings of physician respectfulness by patient estimation of physician respect.

Mean coder rating of physician respectfulness by categories of patient estimation of physician respect was calculated by using multilevel linear regression analyses adjusted for patient age and physician familiarity with the patient. There was no significant difference between the groups.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1 Discussion

In this study, we found that overestimation of respect was significantly associated with increasing BMI. These results support our theory that obese patients may overestimate physician level of respect, which we hypothesized may be due to past experiences that have desensitized them to disrespectful behaviors. Underestimation of respect occurred infrequently. Overestimation of physician respect is unlikely to be a consequence of overly respectful physician behaviors, as there was no difference in mean physician respectfulness rated by coders between categories of respect estimation. First, we will discuss the theoretical questions raised by our study, and then, we will describe the limitations of this study to explain why we feel our results should be considered preliminary findings.

Our study raises an interesting issue to consider. Does it matter if patients overestimate physician respect? If an obese patient leaves a physician encounter with a sense of having been respected more than they actually were, has any harm been done? One could argue that we should be glad that the physician did not behave disrespectfully, despite documented negative attitudes towards obese patients among physicians [3–9]. We could reassure ourselves that the physician respected the patient well enough not to demonstrate lower regard. While physicians may be successfully playing the part, the lack of true respect suggests inauthentic relationships. The idea of inauthentic encounters has also raised concern in the medical education field, specifically related to using simulated patients to teach empathy [22–23]. Students learn that communication is a checklist of behaviors, rather than a process through which empathic connections are made with patients [23].

In our study, physicians provided an outward show of respect, but did they form genuine ties with their patients? Those concerned with authentic patient-physician relationships may have qualms about whether this situation puts the patient at a disadvantage [17]. Authentic relationships should foster open dialogue and create an environment of mutual trust and responsibility in decision-making between patients and physicians [18]. In an inauthentic conversation, does the physician truly take into account the best interests and wishes of the patient when the physician does not truly respect the patient in question? The inauthentic physician may fail to recommend treatments that could benefit the patient or advise treatments that could put them at additional harm. The patient in an inauthentic relationship may be less truthful in disclosing negative behaviors to the physician, because he/she is afraid of losing that perceived respect. This patient might also be over-inclined to trust the physician’s judgment. Indeed, Mechanic and Meyer found that patients emphasized physician’s interpersonal competence as the main driver of trust in physicians, which included respectful treatment [24]. While the physician’s judgment is perhaps well intentioned, it may be formed based on a biased or inaccurate picture of that patient as a person and lead to different treatment. Hebl and Xu found that a patient’s weight led to significant differences in how physicians viewed and treated patients [25]. Physicians were more likely to prescribe more tests for obese patients, despite being presented with the same clinical scenarios for all patients regardless of weight [25]. These theoretical issues would benefit from future empirical research.

Our results should be interpreted cautiously. We feel that our findings support the theory that obesity could alter one’s ability to accurately perceive the attitudes of others during interpersonal interactions. This hypothesis warrants confirmation and future evaluation examining associations with physician communication behaviors, quality of care measures and health outcomes. We feel that our results should be considered preliminary and make this statement in light of the limitations of this study as described below and lack of prior studies examining this concept in general.

Our study has several limitations concerning the measures used to evaluate respect. Respect is a nuanced concept [2], and the physicians, patients, and RIAS coders in our study may have been using different conceptualizations of respect when forming their answers. We have identified only one prior study that examines the accuracy of estimation of physician respect by patients in general [2]. While we originally planned to perform an analysis modeled after the study by Beach et al [2], we identified concerns with using this strategy. First, our phrasing of the physician question and scale was different. Second, conceptual issues were raised regarding the significance of different responses and subsequent labeling into categories of accurate estimation, overestimation and underestimation. In an effort to be transparent, we have presented the results from all three different analyses in Table 5. All three analyses show an effect in the same direction; however, the effect size and statistical significance are attenuated in sensitivity analysis B. This analysis used the strictest definitions of overestimation and underestimation, which resulted in only a small number of patients meeting criteria for overestimation. Overall, our struggle with these conceptual issues highlights how this area of investigation needs additional studies to determine the best way to measure and define estimation of respect between patients and physicians.

There are additional limitations to our study. This study was conducted in the primary care setting, where patients and physicians usually form long-term relationships. Findings may be different in settings where impressions form more quickly. We also did not link our results with quality of care or clinical outcomes; thus, we do not know whether patients who accurately estimate physician respect receive higher quality of care and achieve better health outcomes than patients who cannot accurately estimate physician respect.

4.2 Conclusion

Patients are significantly more likely to overestimate physician respect as BMI increases. These results support the theory that obesity can alter one’s ability to accurately perceive the attitudes of others during interpersonal interactions. Future work is needed to confirm this hypothesis, and identify how overestimation of physicians’ attitudes may affect quality of care for patients with obesity.

4.3 Practice implications

Respectful treatment during the patient encounter may help create a strong therapeutic alliance between patient and physician. However, it is unknown how the physician’s internalized negative attitudes towards obese patients may impact the quality of care for patients who overestimate respect. Do physicians who harbor less respectful attitudes for obese patients differ in their diagnostic and treatment recommendations? Further investigation needs to clarify if obese patients who overestimate physician respect are receiving equitable care and achieving equivalent health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (LAC; R01HL069403, K24HL083113)(MCB; 5RO1HL088511-02) and the National Center for Research Resources (MMH; 1KL2RR025006). KAG was supported by a training grant from the Health Resources and Service Administration (T32HP10025-16-00). KAG had full access to study data and takes responsibility for the accuracy of the analysis. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Beach MC, Duggan PS, Cassel CK, Geller G. What does ‘respect’ mean? Exploring the moral obligation of health professionals to respect patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:692–695. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0054-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beach MC, Roter DL, Wang NY, Duggan PS, Cooper LA. Are physicians’ attitudes of respect accurately perceived by patients and associated with more positive communication behaviors? Patient Educ Couns. 2006;62:347–354. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huizinga MM, Cooper LA, Bleich SN, Clark JM, Beach MC. Physician respect for patients with obesity. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1236–1239. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1104-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teachman BA, Brownell KD. Implicit anti-fat bias among health professionals: is anyone immune? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1525–1531. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz MB, Chambliss HO, Brownell KD, Blair SN, Billington C. Weight bias among health professionals specializing in obesity. Obes Res. 2003;11:1033–1039. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jay M, Kalet A, Ark T, McMacken M, Messito MJ, Richter R, Schlair S, Sherman S, Zabar S, Gillespie C. Physicians’ attitudes about obesity and their associations with competency and speciality: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:106. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrante JM, Piasecki AK, Ohman-Strickland PA, Crabtree BF. Family physicians’ practices and attitudes regarding care of extremely obese patients. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:1710–6. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogden J, Bandara I, Cohen H, Farmer D, Hardie J, Minas H, Moore J, Qureshi S, Walter F, Whitehead MA. General practitioners’ and patients’ models of obesity: whose problem is it? Patient Educ Couns. 2001;44:227–33. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein L, Ogden J. A qualitative study of GP’s views of treating obesity. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:750–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wadden TA, Anderson DA, Foster GD, Bennett A, Steinberg C, Sarwer DB. Obese women’s perceptions of their physicians’ weight management attitudes and practices. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:854–860. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.9.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wee CC, Phillips RA, Cook EF, Haas JS, Puopolo AL, Brennan TA, et al. Influence of body weight on patients’ satisfaction with ambulatory care. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:155–159. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.00825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fong RL, Bertakis KD, Franks P. Association between obesity and patient satisfaction. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:1402–1411. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson DA, Wadden TA. Bariatric surgery patients’ view of their physicians’ weight-related attitudes and practices. Obes Res. 2004;12:1587–95. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puhl R, Brownell KD. Bias, discrimination, and obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9:788–805. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puhl RM, Heuer CA. The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:941–964. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brandsma LL. Physician and patient attitudes toward obesity. Eat Disord. 2005;13:201–11. doi: 10.1080/10640260590919134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beach MC, Inui T. Relationship-centered care. A constructive reframing. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21 (Suppl 1):S3–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnason V. Towards authentic conversations. Authenticity in the patient-professional relationship. Theor Med. 1994;15:227–42. doi: 10.1007/BF01313339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Bone LR, Larson SM, Miller ER, Barr MS, et al. A randomized controlled trial of interventions to enhance patient-physician partnership, patient adherence and high blood pressure control among ethnic minorities and poor persons: study protocol NCT00123045. Implement Sci. 2009;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roter D, Larson S. The Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS): utility and flexibility for analysis of medical interactions. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46:243–51. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:907–15. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steele DJ, Hulsman RL. Empathy, authenticity, assessment and simulation: a conundrum in search of a solution. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71:143–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wear D, Varley JD. Rituals of verification: the role of simulation in developing and evaluating empathic communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71:153–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mechanic D, Meyer S. Concepts of trust among patients with serious illness. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:657–68. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hebl MR, Xu J. Weighing the care: physician’s reactions to the size of a patient. Int J Obes. 2001;25:1246–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]