Abstract

A key feature of the mammalian brain is its capacity to adapt in response to experience, in part by remodeling of synaptic connections between neurons. Excitatory synapse rearrangements have been monitored in vivo by observation of dendritic spine dynamics, but lack of a vital marker for inhibitory synapses has precluded their observation. Here, we simultaneously monitor in vivo inhibitory synapse and dendritic spine dynamics across the entire dendritic arbor of pyramidal neurons in the adult mammalian cortex using large volume high-resolution dual color two-photon microscopy. We find that inhibitory synapses on dendritic shafts and spines differ in their distribution across the arbor and in their remodeling kinetics during normal and altered sensory experience. Further, we find inhibitory synapse and dendritic spine remodeling to be spatially clustered, and that clustering is influenced by sensory input. Our findings provide in vivo evidence for local coordination of inhibitory and excitatory synaptic rearrangements.

INTRODUCTION

The ability of the adult brain to change in response to experience arises from coordinated modifications of a highly diverse set of synaptic connections. These modifications include the strengthening or weakening of existing connections, as well as synapse formation and elimination. The persistent nature of structural synaptic changes make them particularly attractive as cellular substrates for long-term changes in connectivity, such as might be required for learning and memory or changes in cortical map representation (Bailey and Kandel, 1993; Buonomano and Merzenich, 1998). Sensory experience can produce parallel changes in excitatory and inhibitory synapse density in the cortex (Knott et al., 2002), and the interplay between excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission plays an important role in adult brain plasticity (Spolidoro et al., 2009).. Excitatory and inhibitory inputs both participate in the processing and integration of local dendritic activity (Sjostrom et al., 2008), suggesting they are coordinated at the dendritic level. However, the manner in which these changes are orchestrated and the extent to which they are spatially clustered are unknown.

Evidence for the gain and loss of synapses in the adult mammalian cortex has predominantly used dendritic spines as a proxy for excitatory synapses on excitatory pyramidal neurons. The vast majority of excitatory inputs to pyramidal neurons synapse onto dendritic spine protrusions that stud the dendrites of these principal cortical cells (Peters, 2002) and to a large approximation are thought to provide a one-to-one indicator of excitatory synaptic presence (Holtmaat and Svoboda, 2009). Inhibitory synapses onto excitatory neurons target a variety of subcellular domains, including the cell body, axon initial segment, dendritic shaft, as well as some dendritic spines (Markram et al., 2004). Unlike monitoring of excitatory synapse elimination and formation on neocortical pyramidal neurons, there is no morphological surrogate for the visualization of inhibitory synapses. Inhibitory synapse dynamics has been inferred from in vitro and in vivo monitoring of inhibitory axonal bouton remodeling (Keck et al., 2011; Marik et al., 2010; Wierenga et al., 2008). However, imaging of pre-synaptic structures does not provide information regarding the identity of the post-synaptic cell nor their subcellular sites of contact. In addition, monitoring of either dendritic spine or inhibitory bouton dynamics has thus far utilized a limited field of view, and has not provided a comprehensive picture of how these dynamics are distributed and potentially coordinated across the entire arbor.

Here we simultaneously monitored inhibitory synapse and dendritic spine remodeling across the entire dendritic arbor of cortical L2/3 pyramidal neurons in vivo during normal and altered sensory experience. We found that inhibitory synapses on dendritic shafts and spines differ in their distribution across the arbor, consistent with different roles in dendritic integration. These two inhibitory synapse population also display distinct temporal responses to visual deprivation, suggesting different involvements in early versus sustained phases of experience-dependent plasticity. Finally, we find that the rearrangements of inhibitory synapses and dendritic spines are locally clustered, mainly within 10 μm of each other, the spatial range of local intracellular signaling mechanisms, and that this clustering is influenced by experience.

RESULTS

Simultaneous In Vivo Imaging of Inhibitory Synapses and Dendritic Spines

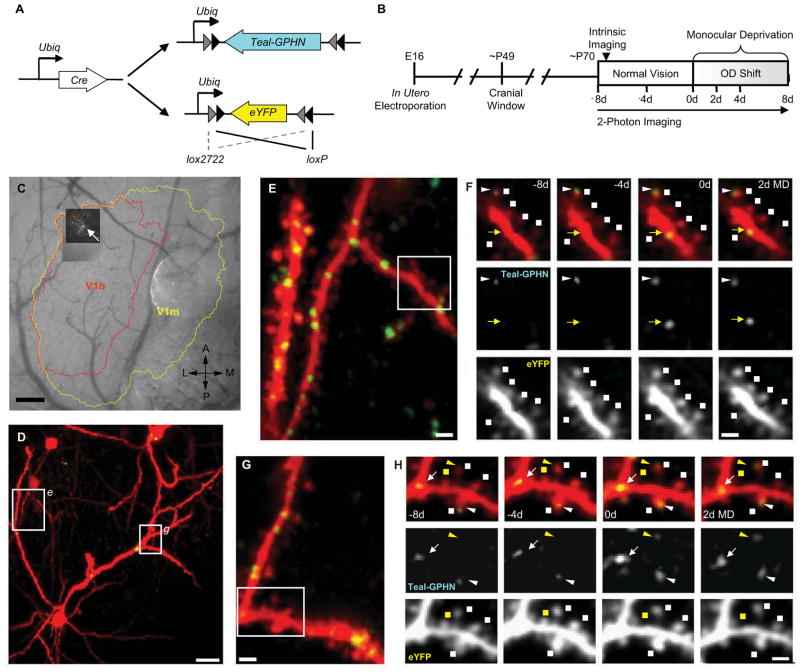

To label inhibitory synapses for in vivo imaging, we generated a Cre-dependent plasmid expressing Teal fluorescent protein fused to Gephyrin, a post-synaptic scaffolding protein exclusively found at GABAergic and glycinegic synapses (Craig et al., 1996; Schmitt et al., 1987; Triller et al., 1985), (Teal-Gephyrin) (Figure 1A). This construct was co-electroporated with two additional plasmids: a Cre-dependent enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (eYFP) plasmid to label neuronal morphology, and a Cre construct. Cre-dependent expression of Teal-Gephyrin and eYFP was achieved through of the use of a ‘double-floxed’ inverted open reading frame (dio) system (Atasoy et al., 2008) in which each gene was inserted in the antisense orientation flanked by two incompatible sets of loxP sites. Co-electroporation at high molar ratios of Teal-Gephyrin and eYFP and low molar ratios of Cre favored a high incidence of co-expression of both fluorophores, with the sparse neuronal labelling required for single cell imaging and reconstruction. Electroporations were performed in utero on E16 embryos of pregnant C57/BL6 mice, targeting the lateral ventricle to label cortical progenitors at the time of L2/3 pyramidal neuron generation (Figure 1B). Mice were subsequently reared to 6–8 weeks of age and then implanted with bilateral cranial windows over the visual cortices. Allowing 2–3 weeks for recovery (Lee et al., 2008), labeled neurons were identified and 3D-volume images were acquired using a custom built two-channel two-photon microscope.

Figure 1.

Chronic in vivo two-photon imaging of inhibitory synapses and dendritic spines in L2/3 pyramidal neurons. (A) Plasmid constructs for dual labeling of inhibitory synapses (Teal-GPHN) and dendritic spines (eYFP) in cortical L2/3 pyramidal neurons. Cre/loxP system was used to achieve sparse expression density. (B) Experimental time course. (C) CCD camera image of blood vessel map with maximum z-projection (MZP) of chronically imaged neuron (white arrow) superimposed over intrinsic signal map of monocular (yellow) and binocular (red) primary visual cortex. (D) Low-magnification MZP of acquired two-photon imaging volume. (E,G) High magnification view of dendritic segments (boxes in [D]) with labeled dendritic spines (red) and Teal-GPHN puncta (green). (F,H) Examples of dendritic spine and inhibitory synapse turnover (boxes in [E] and [G], respectively). Dual color images (top) along with single-color Teal-GPHN (middle) and eYFP (bottom) images are shown. Dendritic spines (squares), inhibitory shaft synapses (arrows), and inhibitory spine synapses (triangles) are indicated with stable (white) and dynamic (yellow) synapses or spines identified. An added inhibitory shaft synapse is shown in [F]. An added Inhibitory spine synapse and eliminated dendritic spine is shown in [H]. Scale bars: (C), 200 μm; (D), 20 μm; (E,G), 5 μm; (F,H), 2 μm.

Imaging of eYFP-labeled neuronal morphology and Teal-labeled Gephyrin puncta was performed by simultaneous excitation of eYFP and Teal and separation of the emission spectra into two detection channels, followed by post-hoc spectral linear un-mixing (see Experimental Procedures, Supplemental Experimental Procedures and Figure S1). In addition, functional maps of monocular and binocular primary visual cortex were obtained by optical imaging of intrinsic signals, and blood vessel maps were used to identify the location of imaged cells with respect to these cortical regions (Figure 1C). At least 70% of the entire dendritic tree was captured within our imaging volume. Cells in binocular visual cortex were imaged at 4 day intervals, initially for 8 days of normal visual experience followed by 8 days of monocular deprivation by eyelid suture (MD) with an intermediate imaging session after 2 days MD.

In vivo imaging of electroporated neurons showed distinct labeling of neuronal morphology by eYFP with clear resolution of dendritic spines (Figure 1D–G, see also Movie S1). Teal-Gephyrin expression could be visualized as clear punctate labeling along the dendritic shaft and on a fraction of dendritic spines (Figure 1D–G, see also Movie S1), down to 200–250μm below the pial surface (Figures S1C, S3B–D). The majority of Teal-Gephyrin puncta were stable and could be reliably re-identified over multiple days and imaging sessions, but examples of dynamic puncta were also observed.

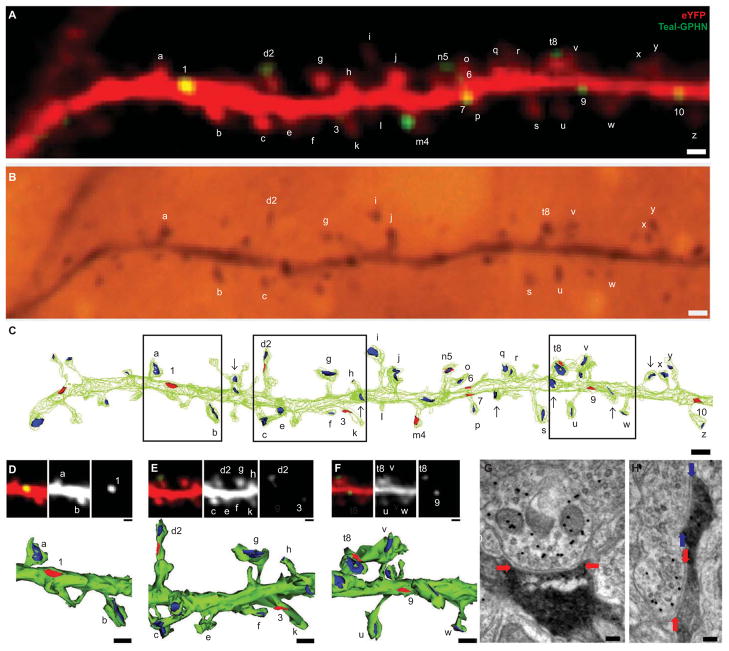

Teal-Gephyrin Puncta Correspond to Inhibitory Synapses

To demonstrate that Teal-Gephyrin puncta visualized in vivo correspond to inhibitory synapses, we performed serial section immuno-electron microscopy (SSEM) on an in vivo imaged L2/3 pyramidal neuron dendrite labeled with eYFP/Teal-Gephyrin (Figure 2A). Immediately after two-photon imaging, the brain was fixed, sectioned, and stained with an antibody to eYFP followed by a biotin-conjugated secondary and detected with nickel-diaminobenzidine (DAB) (Figure 2B). A ~30μm dendritic segment with strong DAB staining was relocated and then further cut into serial ultrathin sections and processed for post-embedding GABA immunohistochemistry to discriminate between inhibitory and excitatory presynaptic terminals.

Figure 2.

Teal-Gephyrin puncta correspond to inhibitory synapses. (A) In vivo image of an eYFP (red) and Teal-Gephyrin (green) labeled dendrite. Letters indicate identified dendritic spines, numbers indicate identified inhibitory synapses. (D) Re-identification of the same imaged dendrite in fixed tissue after immunostaining for eYFP. (F) Serial-section electron microscopy (SSEM) reconstruction of the in vivo imaged dendrite (in green) with identified GABAergic synapses (in red), non-GABAergic synapses (in blue), and unidentified spine-synapses (arrows). (D–F) High magnification view of region outlined in [C] with merged (top-left panels), eYFP only (top-middle panels), Teal-Gephyrin only (top-right panels) in vivo images and SSEM reconstruction (bottom panel) (G) Electron micrograph of inhibitory shaft synapse ‘1’ in [D] identified by a GABAergic pre-synaptic terminal visualized by post-embedding GABA immunohistochemistry with 15 nm colloidal gold particles (black circles identify GABAergic pre-synaptic terminal) contacting eYFP-labeled dendritic shaft (DAB staining, red arrows mark synaptic cleft). (H) Electron micrograph of doubly-innervated dendritic spine ‘d2’ in [E] with inhibitory synapse (red arrows mark synaptic cleft) and excitatory synapse (blue arrows mark synaptic cleft). Scale bars: (A–C), 1 μm; (D–F, top panels), 1μm; (D–F, bottom panels), 500nm; (G,H), 100 nm.

The robustness of the nickel-DAB staining was such that it frequently obscured most of the post-synaptic dendritic compartment, including the post-synaptic density, of many synaptic contacts. Visualization of the post-synaptic density is considered an important criterion for identifying synapses, and in some cases a post-synaptic membrane specialization could be discerned despite the DAB staining, but other important criteria include aggregation of synaptic small vesicles at the pre-synaptic junction, and a clear synaptic cleft structure between the pre- and post-synaptic junction. Contacts were categorized as synapses only if all or at least two of these criteria were present in at least a few serial ultrathin sections (Figure S2A, B). The densities of GABA marker colloidal gold particles were clearly different between GABA-positive and -negative pre-synaptic terminals, and a terminal was categorized as GABA-positive if a high particle density was found in the pre-synaptic terminal across multiple serial ultrathin sections.

The reconstructed segment contained twenty-six dendritic spines observed in vivo which were re-identified after SSEM-reconstruction and all found to bear synaptic contacts (Figure 2C, see also Movie S2). Six additional spines each with a single excitatory synapse were identified by EM but not visualized in vivo likely due to their orientation perpendicular to the imaging plane. Eleven filopodia-like structures without synaptic contacts were also found. These possessed very thin necks (50–250 nm in width) and were also unresolved by two-photon microscopy. This suggests that while dendritic spines imaged in vivo indeed closely represent excitatory synaptic contacts, in vivo imaging potentially underestimates their true number by as much as 20%.

All 10 of the Teal-Gephyrin puncta visualized in vivo corresponded with GABAergic synapses found by EM. Six were localized on the dendritic shaft while 4 were located on dendritic spines (Figure 2C–G, S2A). Three out of the 4 dendritic spines bearing inhibitory synapses were found to be co-innervated with an excitatory synapse (Figure 2H, S2B). While a co-innervated excitatory synapse was not found on the remaining spine this is likely due to known limitations of the EM reconstruction (Kubota et al., 2009). The proportion of doubly-innervated dendritic spines observed on this segment is comparable to previously reported results (Kubota et al., 2007). Further SSEM reconstruction of the surrounding neuropil revealed additional GABAergic processes touching the imaged dendrite without forming synaptic contact. No Teal-Gephyrin puncta were observed in vivo at these points of contact (Figure S2C–E). These results confirm that imaged Teal-Gephyrin puncta correspond one-to-one with GABAergic inhibitory synapses.

Differential Distribution of Inhibitory Spine and Shaft Synapses

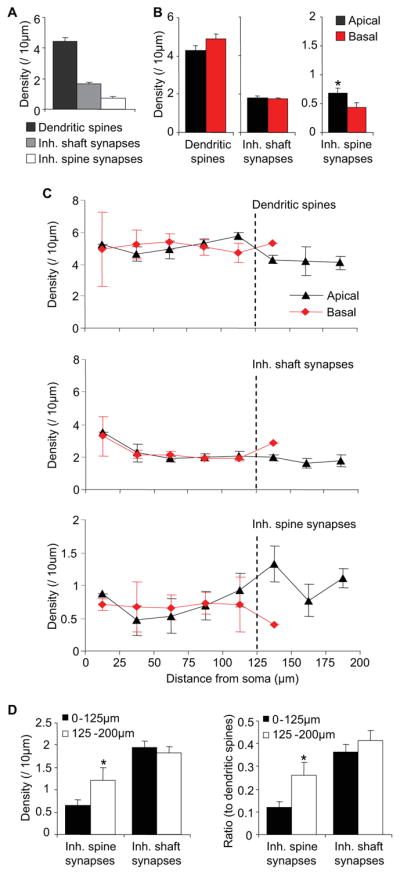

To date, inhibitory synapse distribution on L2/3 pyramidal cell dendrites and its relation to dendritic spine distribution have been estimated from volumetric density measurements (DeFelipe et al., 2002). We first used Teal-Gephyrin/eYFP labeling to characterize the distribution of inhibitory synapses on both shafts and spines, as well as dendritic spine distribution on the same L2/3 pyramidal cells imaged in vivo. The density of dendritic spines was 4.42 ± 0.27 per 10 μm length of dendrite (Figure 3A). While likely a slight underestimate based on our EM observations, this is in agreement with previous in vivo two-photon measurements (Holtmaat et al., 2005). A fraction of these spines (13.60 ± 1.38%) bore inhibitory synapses with a density of 0.71 ± 0.11 per 10 μm. Inhibitory synapses along the dendritic shaft were approximately twice as abundant with a density of 1.68 ± 0.08 per 10 μm. While dendritic spine density and inhibitory shaft synapse density were similar on apical versus basal dendrites, apical dendrites contained a higher density of inhibitory spine synapses than basal dendrites (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.05) (Figure 3B). When spine and inhibitory shaft synapse distribution were measured along the dendrite as a function of distance from the cell soma, their density along both apical and basal dendrites was found to be constant regardless of proximal or distal location (Figure 3C). In contrast, the density of inhibitory spine synapses on apical dendrites increased with distance from the cell soma, and was two-fold higher at locations greater than 125μm from the cell soma as compared to proximal locations along the same dendritic tree (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.05) (Figure 3D), resulting in a two-fold increase in the ratio of inhibitory spine synapses to dendritic spines (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.05) (Figure 3E). Identical analysis performed ex vivo in 50μm coronal sections yielded the same results, validating the reliability of our in vivo imaging-based quantifications and showing that imaging depth does not diminish the fidelity of synapse scoring in the depth range that we are imaging (Figure S3). These findings demonstrate that while the distribution of inhibitory shaft synapses is constant throughout the dendritic field, inhibitory spine synapses are distributed non-uniformly, with higher densities at distal apical dendrites.

Figure 3.

Dendritic distribution of inhibitory shaft and spine synapses. (A) Dendritic density of dendritic spines, inhibitory shaft synapses, and inhibitory spine synapses per cell. (B) Density per dendrite in apical versus basal dendrites of dendritic spines (left), inhibitory shaft synapses (middle), inhibitory spine synapses (right). (C) Dendritic density as a function of distance from the cell soma in apical (black) and basal (red) dendrites for dendritic spines (top panel), inhibitory shaft synapses (middle panel), and inhibitory spine synapses (bottom panel). (D) Density of inhibitory spine (left) and inhibitory shaft (right) synapses in proximal (0–125μm from soma) versus distal (125–200μm from soma) apical dendrites. (E) Ratio of inhibitory spine (left) and inhibitory shaft (right) synapses to dendritic spines in proximal (0–125μm from soma) versus distal (125–200μm from soma) apical dendrites. (n = 14 cells from 6 animals for [A,C–E]; n = 43 apical dendrites, 40 basal dendrites for [B]) (*P < 0.05). Error bars, s.e.m.

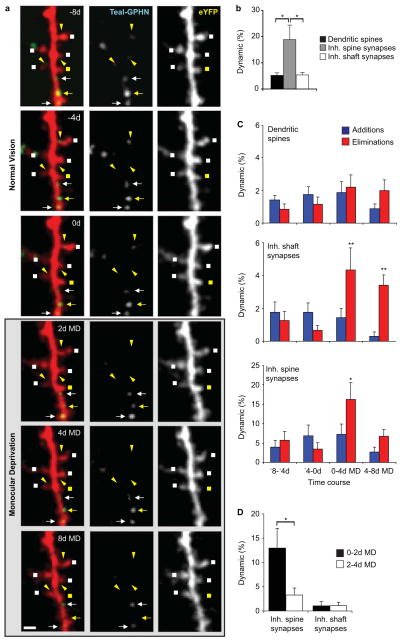

Inhibitory Spine and Shaft Synapse Remodeling are Kinetically Distinct

Given the distinct anatomical distributions of inhibitory spine and shaft synapses, we next asked if these two populations also differ in their capacities for synaptic rearrangement during normal and altered sensory experience (Figure 1B, 4A). The majority of inhibitory synapse rearrangements observed were persistent (persisting for at least 2 imaging sections), with only a small fraction of events transiently lasting for only one imaging session, 4.20 ± 2.56% of all events in the case of inhibitory shaft synapses and 9.00 ± 3.97% for inhibitory spine synapses (Figure S4A, B). Given the low incidence of these transient events within the population of dynamic events, they were excluded from analysis, and only persistent changes were scored. In the case of dendritic spines, it has been established that spines that are persistent for 4 days or more always have synapses (Knott et al., 2006). Given that our imaging interval is typically 4 days, our scoring rationale in this case has some biological meaning rather than being purely methodological. In order to be consistent with measurement of spine dynamics (see further in the manuscript) our methods for scoring transient and persistent inhibitory synapses are similar to those for dendritic spines, Analysis of persistent changes during normal experience revealed similar fractional turnover rates for inhibitory shaft synapses and dendritic spines, with 5.36 ± 0.97% of shaft synapses and 5.26 ± 0.89% of dendritic spines remodeling over an 8 day period (Figure 4B). Inhibitory spine synapses, whether stable or dynamic, were exclusively located on stable, persistent spines. These synapses were fractionally more dynamic as compared to dendritic spines and inhibitory shaft synapses with 18.84 ± 5.50% of inhibitory spine synapses appearing or disappearing over an 8 day period of normal vision (dendritic spines versus inhibitory spine synapses, Wilcoxon rank sum test, P < 0.05; inhibitory shaft synapses versus inhibitory spine synapses, Wilcoxon rank sum test, P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Inhibitory spine and shaft synapses form two kinetic classes. (A) Example of dendritic spine and inhibitory synapse dynamics of L2/3 pyramidal neurons in binocular visual cortex during monocular deprivation. Dual color images (left) along with single-color Teal-GPHN (middle) and eYFP (right) images are shown. Dendritic spines (squares), inhibitory shaft synapses (arrows), and inhibitory spine synapses (triangles) are indicated with stable (white) and dynamic (yellow) synapses or spines identified. (B) Fraction of dynamic dendritic spines, inhibitory shaft synapses, and inhibitory spine synapses during control conditions of normal vision. (C) Fraction of additions or eliminations of dendritic spines (top), inhibitory shaft synapses (middle), and inhibitory spine synapses (bottom) at 4 day intervals before and during monocular deprivation. (D) Fraction of eliminations of inhibitory spine inhibitory and inhibitory shaft synapses at 0–2d MD and 2–4d MD. (n = 14 cells from 6 animals) (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005). Error bars, s.e.m.

In the adult mouse, prolonged MD produces an ocular dominance (OD) shift in the binocular visual cortex, characterized by a slight weakening of deprived-eye inputs and a strengthening of non-deprived eye inputs (Frenkel et al., 2006; Sato and Stryker, 2008). As previously described (Hofer et al., 2009), we observed no increase in spine gain or loss on L2/3 pyramidal neurons during MD (Figure 4C). However, MD doubled the fraction of inhibitory shaft synapse loss during the first four days of MD (repeated measures ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test, P < 0.01). This increased loss persisted throughout the entire 8 days of MD. A decrease in inhibitory shaft synapse additions was also observed at 4–8d MD (repeated measures ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test, P < 0.005). A larger than 3-fold increase in inhibitory spine synapse loss was observed during the early period of MD (repeated-measures ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test, P < 0.05). Analysis at 0–2d MD and 2–4d MD intervals shows that the increase inhibitory spine synapse loss was specific to the first two days of MD (Wilcoxon rank sum test, P < 0.05) (Figure 4D). Imaging over a 16-day period in control animals showed no fractional change in inhibitory synapse additions or eliminations across the imaging time course, indicating that the inhibitory synapse losses observed were specifically induced by MD (Figure S4C). These findings demonstrate that inhibitory shaft and spine synapses are kinetically distinct populations and that experience can differentially drive their elimination and formation.

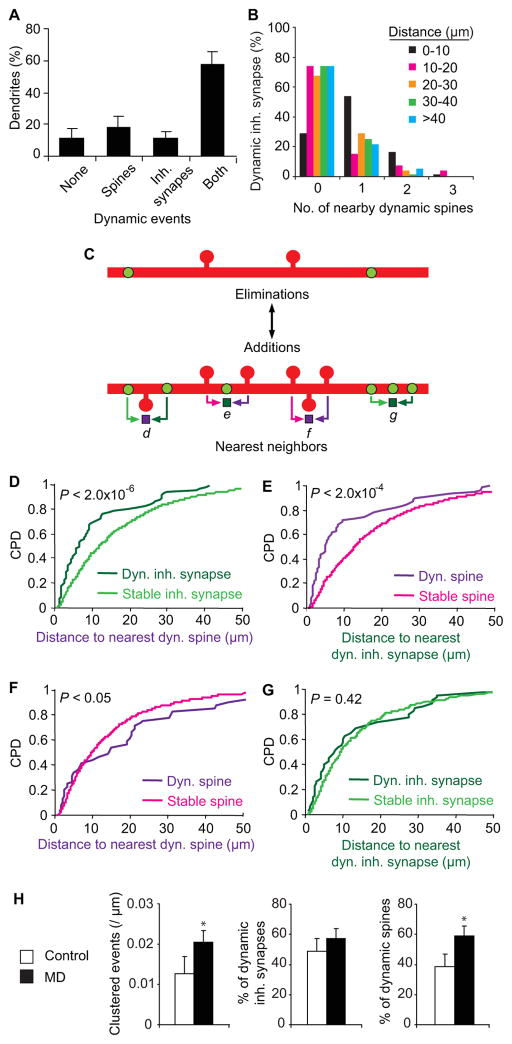

Inhibitory Synapse and Dendritic Spine Changes are Locally Clustered

Long-term plasticity induced at one dendritic spine can coordinately alter the threshold for plasticity in nearby neighboring spines (Govindarajan et al., 2011; Harvey and Svoboda, 2007). Electrophysiological studies suggest that plasticity of inhibitory and excitatory synapses may also be coordinated at the dendritic level. Calcium influx and activation of calcium-dependent signaling molecules that lead to long-term plasticity at excitatory synapses can also induce plasticity at neighboring inhibitory synapses (Lu et al., 2000; Marsden et al., 2010). Conversely, inhibitory synapses can influence excitatory synapse plasticity by suppressing calcium-dependent activity along the dendrite (Miles et al., 1996). Given the limited spatial extent of these signaling mechanisms (Harvey and Svoboda, 2007; Harvey et al., 2008), we looked for evidence of local clustering between excitatory and inhibitory synaptic changes.

We first looked at the distribution of dynamic events resulting in persistent changes (both additions and eliminations) on each dendritic segment (68.1 ± 2.9 μm in length) as defined by the region from one branch point to the next or from branch tip to the nearest branch point. During normal visual experience, 58.2 ± 7.6% of dendritic segments per cell contained both a dynamic inhibitory (spine or shaft) synapse and a dynamic dendritic spine (Figure 5A). On these dendritic segments, a large fraction of dynamic inhibitory synapses and dendritic spines were found to be located within 10 μm of each other, suggesting that these changes were clustered (dynamic spines to nearby dynamic inhibitory synapses, repeated-measures ANOVA, P < 1 × 10−10; dynamic inhibitory synapses to nearby dynamic spines, repeated-measures ANOVA, P < 0.0005) (Figure 5B, S5A). To determine whether clustering of dynamic inhibitory synapses with dynamic spines were merely a reflection of the dendritic distribution of inhibitory synapses and spines, we performed nearest neighbor analysis between every monitored dynamic and stable inhibitory synapse and every dynamic and stable spine (Figure 5C). We found that inhibitory synapse changes occur in closer proximity to dynamic dendritic spines as compared to stable spines (K–S test, P < 2.0 × 10−6) (Figure 5D). Conversely, dendritic spine changes occur in closer proximity to dynamic inhibitory synapses as compared to stable inhibitory synapses (K–S test, P < 2.0 × 10−4) (Figure 5E). Interestingly, dendritic spine changes were not clustered with each other, and indeed occurred with less proximity to neighboring dynamic spines as compared to stable spines (stable spines versus dynamic spines, K–S test, P < 0.05) (Figure 5F). We observed no difference in nearest neighbor distribution between dynamic inhibitory synapses and their dynamic or stable inhibitory counterparts (Figure 5G). These results demonstrate that dendritic spine-inhibitory synapse changes are spatially clustered along dendritic segments while dendritic spine-dendritic spine changes and inhibitory synapse-inhibitory synapse changes are not. Clustered dynamics was the same for inhibitory shaft or spine synapses in relation to the nearest dynamic dendritic spine (Figure S5B).

Figure 5.

Inhibitory synapse and dendritic spine dynamics are spatially clustered. (A) Distribution of dendritic segments with no dynamic events, only dynamic spines, only dynamic inhibitory synapses, and both dynamic spines and inhibitory synapses. (B) Fraction of dynamic inhibitory synapses with nearby dynamic spines as a function of proximal distance from dynamic inhibitory synapse. (C) Simplified diagram of possible clustered events between dynamic inhibitory synapses and dynamic dendritic spines. For the purpose of illustration, only a sample of clustered events are shown, however, for quantifications in D–H all dynamic events were scored, including inhibitory spine and shaft synapses, additions and eliminations. ‘d’ illustrates a stable inhibitory synapse (light green arrow) and dynamic inhibitory synapse (dark green arrow) with neighboring dynamic spine (purple square). ‘e’ illustrates a stable spine (pink arrow) and dynamic spine (purple arrow) with neighboring dynamic inhibitory synapse (dark green square). ‘f’ illustrates a stable spine (pink arrow) and dynamic spine (purple arrow) with neighboring dynamic spine (purple square). ‘g’ illustrates a stable spine (light green arrow) and dynamic spine (dark green arrow) with neighboring dynamic inhibitory synapse (dark green square). (D–G) Cumulative probability distribution (CPD) of nearest neighbor distances comparing stable and dynamic counterparts and their nearest dynamic spine or inhibitory synapse. Stable vs. dynamic inhibitory synapse to nearest dynamic dendritic spine for [D]. Stable vs. dynamic dendritic spine to nearest dynamic inhibitory synapse for [E]. Stable vs. dynamic dendritic spine to nearest dynamic dendritic spine for [F]. Stable vs. dynamic inhibitory synapse to nearest dynamic inhibitory synapse for [G]. (H) Comparison of clustered events (within 10 μm) between dynamic spines and inhibitory synapses before and during MD. Frequency of events is shown on the left panel. Fraction of dynamic inhibitory synapses participating in clustered events is shown on the center panel. Fraction of dynamic spines participating in clustered events is shown on the right panel. (* P < 0.05) (n = 14 cells from 6 animals for [A,H]; n = 83 dendrites for [B]; n = 2230 dendritic spines, 1211 inhibitory synapses for [D–G]). Error bars, s.e.m.

We next asked how altering sensory experience through MD affects clustering of inhibitory synapse and dendritic spine changes. We found that clustering between dynamic inhibitory synapses and dendritic spines persisted during MD (Figure S5C) with a similar spatial distribution compared to control conditions (Figure S5D). We compared the frequency of clustered events during normal vision and MD by quantifying the number of inhibitory synapses and dendritic spine changes occurring within 10μm of each other. MD increased the frequency of clustered events from 0.013 ± 0.004 to 0.020 ± 0.003 per μm dendrite (Wilcoxon rank sum test, P < 0.05) (Figure 5H). Since MD increases inhibitory synapse but not dendritic spine dynamics, we asked how an increase in clustered events could occur without a concurrent change in dendritic spine remodeling. We found that while the fraction of dynamic spines did not increase in response to MD (Figure 4B–D), the fraction of dynamic spines participating in clustered events increased from 38.4±9.0% to 59.0±7.7% during MD (Wilcoxon rank sum test, P < 0.05).

A small fraction of spines in the SSEM were unaccounted for in the imaging. In all cases, these were z-projecting dendritic spines, obscured by the eYFP –labeled dendrite above or below. Generally, we find little or no image rotation along the x- or y- axis from session to session. Thus, z-projecting spines would potentially appear as very stubby protrusions from the shaft or not at all, and according to spine scoring criteria (see methods), would potentially be unscored. Unless Z-projecting spines differ from x- or y-projecting spines in their capacity for plasticity (which is unlikely or at least has not been observed), this should not affect our understanding of spine turnover data. Since we are measuring the fractional kinetics, these unidentified spines should have no bearing on our measures of plasticity. In the case of Teal-Gephyrin puncta, all were found to correspond with inhibitory synapses seen SSEM, and conversely 100% of inhibitory synapses seen by SSEM were also visualized in vivo. The identification of Teal-Gephyrin puncta are not susceptible to such artifacts given the sparse distribution of these puncta and the absence of other Teal-labeled structures that could obscure these puncta from view. In fact, z-projecting inhibitory spine synapses could be readily identified in the image stacks and aided in the identification of their corresponding dendritic spine, explaining their highly reliable identification.

To rule out the possibility that the increased clustering during MD is simply the result of the increased presence of dynamic inhibitory synapses, we calculated the likelihood that a dendrite with a dynamic spine and dynamic inhibitory synapse would be located within 10μm of each other assuming these events were not clustered. Based on the density of dendritic spines, 8.3±0.5 spines are located within 10μm of a dynamic inhibitory synapse. During MD, 6.4±1.0% of spines are dynamic, 88.9±8.3% of which are located on dendrites with dynamic inhibitory synapses. If changes are not clustered, we calculated a 44.1±7.2% probability that a dynamic spine would be within 10μm of a dynamic inhibitory synapse. However, we find that a significantly larger number, 74.3±7.6% of dynamic spines are within 10μm of a dynamic inhibitory synapse (Wilcoxon rank sum test, P<0.005). Conversely, 4.8±0.3 inhibitory synapses are located within 10μm of a dynamic spine. During MD, 13.6±2.0% of inhibitory synapses are dynamic, 83.1±4.8% of which are located on dendrites with dynamic spines. We calculated a 50.5±5.0% probability that a dynamic spine would be within 10μm of a dynamic inhibitory synapse, if changes are unclustered. Here again, we find a significantly larger number of 75.2±5.1% of dynamic inhibitory synapses located within 10μm of a dynamic spine (Wilcoxon rank sum test, P<0.001). These results demonstrate that the percent of clustered dynamic spines and inhibitory synapses in response to MD is significantly higher than would be expected simply based on the increased fraction of dynamic inhibitory synapses. This suggests that while MD does not alter the overall rate of spine turnover on L2/3 pyramidal neurons, it does lead to increased coordination of dendritic spine rearrangement with the dynamics of nearby inhibitory synapses.

DISCUSSION

By large volume imaging of inhibitory synapses directly on a defined cell type, L2/3 pyramidal neurons, we have characterized the distribution of inhibitory spine and shaft synapses across the dendritic arbor and have measured their remodeling kinetics during normal experience and in response to MD. We find that inhibitory synapses targeting dendritic spines and dendritic shafts are uniquely distributed and display distinct temporal kinetics in response to experience. In addition, by simultaneous monitoring of inhibitory synapses and dendritic spines across the arbor we found that their dynamics are locally clustered within dendrites and that this clustering can be further driven by experience.

We speculate that the differential distribution of inhibitory spine and shaft synapses may reflect differences in connectivity patterns across dendritic compartments as well as the role inhibitory synapses play in the processing of local dendritic activity. Functionally, dendritic inhibition has been shown to suppress calcium-dependent activity along the dendrite (Miles et al., 1996), originating from individual excitatory synaptic inputs as well as back-propagating action potentials (bAPs) from the soma. Local excitation arising from dendritic and NMDA spikes can spread for 10–20 μm and evoke elevated levels of calcium along the dendrite (Golding et al., 2002; Major et al., 2008; Schiller et al., 1997). Our finding that shaft inhibitory synapses are uniformly distributed across dendrites, whereas inhibitory spine synapses are twice as abundant along distal apical dendrites compared to other locations suggest that these two types of synapses have different roles in shaping dendritic activity. The regular distribution of inhibitory shaft synapses may reflect their ability to broadly regulate calcium activity from multiple excitatory synaptic inputs and from bAPs, influencing the integration of activity from mixed sources.

The non-uniform distribution of inhibitory spine synapses may reflect differences in the relative sources of calcium influx at their respective locales. For example, the amplitude of bAPs along dendrites decreases with increasing distance from the soma. While bAPs can routinely produce calcium influx into the most distal parts of basal dendrites, detectable calcium influx into the more distal regions of apical dendrites has only been demonstrated under the most stringent conditions (Larkum and Nevian, 2008). The increased density of inhibitory spine synapses at distal apical dendrites, a region where calcium activity is likely to be more dominated by synaptic inputs than bAPs may reflect an increased relevance in the modulation of individual synaptic inputs. Indeed, we along with others (Jones and Powell, 1969; Knott et al., 2002; Kubota et al., 2007) have shown that dendritic spines with inhibitory synapses are co-innervated with an excitatory synapse, suggesting that they may gate synaptic activity of individual excitatory synaptic inputs. The distribution of inhibitory spine synapses may also relate to the different sources of excitatory connections onto the apical dendrite, suggesting they may be involved in gating specific types of inputs. The apical tuft of L2/3 pyramidal neurons receives a larger proportion of excitatory inputs from more distant cortical and subcortical locations compared to other parts of the dendritic arbor (Spruston, 2008). Subcortical afferents have been identified as the excitatory input that co-innervates spines with inhibitory synapses (Kubota et al., 2007), suggesting that these inhibitory contacts are ideally situated to directly modulate feed-forward sensory-evoked activity in the cortex. Interestingly, we find that all of these co-innervated spines are stable both during normal experience and during MD, regardless of the dynamics of the inhibitory spine synapse. This suggests that subcortical inputs entering the cortex onto dually innervated spines are likely to be directly gated by inhibition at their entry level, the spine, but due to the structural stability of these feed forward inputs, their functional modification would have to rely on removal/addition of the gating inhibitory input. This particular type of excitatory synapse may be much more directly influenced by the inhibitory network than excitatory synapses on singly innervated spines that are exposed to the inhibitory network only at the level of the dendrite.

Inhibitory synapses are quite responsive to changes in sensory experience. Recently, focal retinal lesions have been shown to produce large and persistent losses in axonal boutons in the adult mouse visual cortex (Keck et al., 2011). Our ability to distinguish inhibitory spine and shaft synapses provide new insight into the degree of inhibitory synapse dynamics in the adult visual cortex. We find that in binocular visual cortex, MD produces a relatively large initial increase in inhibitory spine synapse loss. Acute changes in inhibitory spine synapse density have also been observed in the barrel cortex after 24 hours of whisker stimulation (Knott et al., 2002), further supporting the notion that these synapses are highly responsive to and are well suited to modulate feed-forward sensory-evoked activity. While inhibitory spine synapses are responsive to the initial loss of sensory input, the sustained increase in inhibitory shaft synapse loss we observe parallels the persistent absence of deprived-eye input and may serve the broader purpose of maintaining levels of dendritic activity and excitability during situations of reduced synaptic drive. These losses in inhibitory synapses are consistent with findings that visual deprivation produces a period of disinhibition in adult visual cortex (Chen et al., 2011; He et al., 2006; Hendry and Jones, 1986; Keck et al., 2011) that is permissive for subsequent plasticity (Chen et al., 2011; Harauzov et al., 2010; Maya Vetencourt et al., 2008).

Finally, models for synaptic clustering have been proposed as a means to increase the computational capacity of dendrites (Larkum and Nevian, 2008) and as a form of long-term memory storage (Govindarajan et al., 2006). These models have generally been derived from evidence of coordinated plasticity between excitatory synapses (Govindarajan et al., 2011; Harvey and Svoboda, 2007). We find that clustered plasticity at the level of synapse formation and elimination can also occur between excitatory and inhibitory synapses and that these changes occur mainly within 10 μm of each other. This is a distance at which calcium influx and calcium-dependent signaling molecules from individual excitatory inputs can directly influence the plasticity of neighboring excitatory synapses (Govindarajan et al., 2011; Harvey and Svoboda, 2007; Harvey et al., 2008). Activation of excitatory inputs can also induce translocation of calcium-dependent signaling molecules to inhibitory synapses resulting in enhanced GABA(A) receptor surface expression (Marsden et al., 2010). Further experiments using GABA uncaging also demonstrate selective inhibition of calcium transients in dendritic regions less than 20 μm from the uncaging site (Kanemoto et al., 2011). These findings and ours suggest that spatial constraints may influence coordinated plasticity between inhibitory and excitatory synapses along dendritic segments. While we and others (Hofer et al., 2009) observe no increase in spine gain or loss on L2/3 pyramidal neurons during adult OD plasticity, the increased clustering of inhibitory synapse-dendritic spine remodeling in response to MD suggests that experience produces coordinated rearrangements between dendritic spines and inhibitory synapses. In the case of dually innervated spines, gating of the excitatory inputs can also be modified by the addition/elimination of inhibitory spine synapses. Thus, MD may still influence excitatory synaptic plasticity in this cell type without altering the overall rate of spine turnover. These findings provide evidence that experience-dependent plasticity in the adult cortex is a highly orchestrated process, integrating changes in excitatory connectivity with the active elimination and formation of inhibitory synapses.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation of Expression Plasmids

For construction of the Cre expression plasmid (pFsynCreW), a Cre insert with 5′ NheI and 3′ EcoRI restriction sites was generated by PCR amplification from a WGA-Cre AAV vector (Gradinaru et al., 2010) and subcloned into a pLL3.7syn lentiviral expression plasmid (Rubinson et al., 2003). The Cre-dependent eYFP expression plasmid (pFUdioeYFPW) was constructed by subcloning a ‘double’ floxed inverse orientation (dio) eYFP expression cassette (a gift from K. Deisseroth) into the pFUGW lentiviral expression plasmid (Lois et al., 2002), replacing the GFP coding region between the 5′ BamHI and 3′ EcoRI restriction sites. The Cre-dependent Teal-Gephyrin expression plasmid (pFUdioTealGephyrinW) was constructed as follows. First, a Teal insert was generated by PCR amplification of Teal (Allele Biotech, San Diego, CA) with added 5′ NheI and 3′ EcoRI restriction sites and subcloned into the pLL3.7syn lentiviral expression plasmid. Next, Gephyrin with 5′ BsrGI and 3′ MfeI restriction sites was generated by PCR amplification from a GFP-Gephyin expression plasmid (Fuhrmann et al., 2002) and subcloned into the Teal expression plasmid using the BsrGI and EcoRI sites to generate a Teal-Gephryin fusion protein. Finally, Teal-Gephyrin with 5′ BsiWI and 3′ NheI restriction sites was PCR amplified from this plasmid and subcloned into the Cre-dependent eYFP expression plasmid described above, replacing eYFP in the dio expression cassette.

In Utero Electroporation

L2/3 cortical pyramidal neurons were labelled by in utero electroporation on E16 timed pregnant C57BL/6J mice (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) as previously described (Tabata and Nakajima, 2001). pFUdioeYFPW, pFUdioTealGephyrinW, pFUCreW plasmids were dissolved in 10 mM Tris±HCl (pH 8.0) at a 10:5:1 molar ratio for a final concentration of 1μg/μl along with 0.1% of Fast Green (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The solution, containing 1–2 μl of plasmid, was delivered into the lateral ventricle with a 32 gauge Hamilton syringe (Hamilton Company, Reno, NV). Five pulses of 35–40V (duration 50ms, frequency 1Hz) were delivered, targeting the visual cortex, using 5mm diameter tweezer-type platinum electrodes connected to a square wave electroporator (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA).

Cranial Window Implantation

Mice born after in utero electroporation were bilaterally implanted with cranial windows at postnatal days 42–57 as previously described(Lee et al., 2008). Sulfamethoxazole (1 mg/ml) and trimethoprim (0.2 mg/ml) were chronically administered in the drinking water through the final imaging session to maintain optical clarity of implanted windows.

Optical Intrinsic Signal Imaging

For functional identification of monocular and binocular visual cortex, optical imaging of intrinsic signal and data analysis were performed as described previously (Kalatsky and Stryker, 2003). Mice were anesthetized and maintained on 0.5–0.8% isofluorane supplemented by chloroprothixene (10 mg/kg, i.m.), and placed in a stereotaxic frame. Heart rate was continuously monitored. For visual stimuli, a horizontal bar (5° in height and 73° in width) drifting up with a period of 12 seconds was presented for 60 cycles on a high-refresh-rate monitor positioned 25 cm in front of the animal. Optical images of visual cortex were acquired continuously under 610 nm illumination with an intrinsic imaging system (LongDaq Imager 3001/C; Optical Imaging Inc., New York, NY) and a 2.5×/0.075 NA (Zeiss, Jena, Germany) objective. Images were spatially binned by 4×4 pixels for analysis. Cortical intrinsic signal was obtained by extracting the Fourier component of light reflectance changes matched to the stimulus frequency whereby the magnitudes of response in these maps are fractional changes in reflectance. The magnitude maps were thresholded at 30% of peak response amplitude to define a response region. Primary visual cortex was determined by stimulation of both eyes. Binocular visual cortex was determined by stimulation of the ipsilateral eye. Monocular visual cortex was determined by subtracting the binocular visual cortex map from the primary visual cortex map.

Monocular Deprivation

Monocular deprivation was performed by eyelid suture. Mice were anesthetized with 1.25% avertin (7.5 ml/kg IP). Lid margins were trimmed and triple antibiotic ophthalmic ointment (Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY) was applied to the eye. Three to five mattress stitches were placed using 6-0 vicryl along the extent of the trimmed lids. Suture integrity was inspected directly prior to each imaging session. Animals whose eyelids did not seal fully shut or had reopened were excluded from further experiments.

Serial Section Immunoelectron Microscopy

For post-hoc localization of previously in vivo imaged dendrites, blood vessels were labeled with a tail vein injection of fixable rhodamine dextran (5% in PBS, 50uL; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) delivered 30 minutes prior to perfusion. Animals were fixed and perfused with an initial solution of 250 mM sucrose, 5 mM MgCl2 in 0.02 M phosphate buffer (PB; pH 7.4) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde containing 0.2% picric acid and 0.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M PB. Following perfusion and fixation, cranial windows were removed and penetrations of DiR (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were made into cortex around the imaged region. Brains were removed, 50μm thin sections were cut parallel to the imaging plane and visualized with an epifluorescence microscope. The brain section containing the branch tip of interest was identified by combining in vivo two-photon images and blood vessel maps with post-hoc blood vessel labeling and DiR penetrations. The identified section was prepared for immuno electron microscopy as previously described (Kubota et al., 2009). Imaged dendrites were stained by immunohistochemistry using an antiserum against eGFP (1: 2000; kind gift from Dr Nobuaki Tamamaki, Kumamoto University, Japan), followed by biotin-conjugated secondary antiserum (1:200; BA-1000, Vector Laboratories) and then the ABC kit (PK-6100, Vector Laboratories). The neurons were labeled with 0.02% DAB, 0.3% nickel in 0.05 M Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.0. Prepared sections were then serially re-sectioned at 50 nm thickness using an ultramicrotome (Reichert Ultracut S, Leica Microsystems). The ultrathin sections were incubated with an antiserum against GABA (1:1000; A-2052, Sigma) in 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.05 M Tris-HCl buffer, followed by 15nm colloidal gold conjugated secondary antiserum (1:100; EM.GAR15, British Biocell International) (Kawaguchi and Kubota, 1998). While DAB staining can obscure post-synaptic structures, post-embedding GABA immunoreactivity has been demonstrated to detect 100% of inhibitory pre-synaptic terminals (Kawaguchi and Kubota, 1998). The stained dendrite was imaged from 136 serial ultra thin sections using TEM (Hitachi H-7000 equipped with AMT CCD camera XR-41, Hitachi, Japan). Image reconstruction and analysis was performed with Reconstruction (http://synapses.clm.utexas.edu/tools/index.stm).

Two-Photon Imaging

Starting at three weeks after cranial window surgery, allowing sufficient time for recovery, adult mice were anesthetized with 1.25% avertin (7.5 ml/kg IP). Anaesthesia was monitored by breathing rate and foot pinch reflex and additional doses of anaesthetic were administered during the imaging session as needed. In vivo two-photon imaging was performed using a custom-built microscope, including a custom-made stereotaxic restraint affixed to a stage insert and custom acquisition software modified for dual channel imaging. The light source for two-photon excitation was a commercial Mai Tai HP Ti:Sapphire laser (Spectra-Physics, Santa Clara, CA) pumped by a 14-W solid state laser delivering 100 fs pulses at a rate of 80 MHz with the power delivered to the objective ranging from approximately 37–50 mW depending on imaging depth. Z-resolution was obtained with a piezo actuator positioning system (Piezosystem Jena, Jena, Germany) mounted to the objective. The excitation wavelength was 915 nm, with the excitation signal passing through a 20×/1.0 NA water immersion objective (Plan-Apochromat, Zeiss, Jena, Germany). After exclusion of excitation light with a barrier filter, emission photons were spectrally separated by a dichroic mirror (520nm) followed by bandpass filters (485/70nm and 560/80nm) and then collected by two independent photomultiplier tubes. An initial low resolution imaging volume (500nm/pixel XY-resolution, 4μm/frame Z-resolution) encompassing a labelled cell was acquired to aid in selecting the region of interest for chronic imaging. All subsequent imaging for synapse and dendritic spine monitoring was performed at higher resolution (250nm/pixel XY-resolution, 0.9μm/frame Z-resolution). Two-photon raw scanner 16-bit data was processed for spectral linear unmixing (see Supplementary Methods) and converted into a 8-bit RGB image z-stack using Matlab and ImageJ (National Institutes of Health).

Spectral Linear Unmixing and Image Processing

Spectral linear unmixing is based on the fact that the total photon count recorded at each pixel in a given channel is the linear sum of the spectral contribution of each fluorophore weighted by its abundance. For a dual channel detection system, the contribution of two fluorophores can be represented by the following equations:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where J is the total signal per channel, I is the fluorophore abundance, and S is the contribution of that fluorophore. These equations can be expressed as a matrix:

| (3) |

whereby the unmixed image [I] can be calculated using the inverse matrix of [S]:

| (4) |

Assuming the detected signal in both channels represents the total spectral contribution for both fluorophores:

| (5) |

| (6) |

[S] was determined experimentally by dual channel acquisition of single excitation two-photon images of cell culture with single fluorophore expression, adjusting laser power and dwell time to achieve photon count levels approximating in vivo signal intensity. (Figure S1A–B). The mean contribution for each fluorophore into each channel representing the reference spectra from the acquired images was calculated using Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA). These values were subsequently used for spectral linear unmixing of dual channel 16-bit two-photon raw scanner data into a 8-bit RGB image z-stack using Matlab and ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). [S] measured from in vivo labelled samples was similar to the in vitro determined value, and spectral unmixing with either the in vitro or in vivo values yielded essentially the same result (Figure S1A–B). Simulations were performed to validate that the 200–250μm imaging depth used for our data acquisition is well within the signal intensity range where spectral unmixing can work reliably (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures and Figure S1C–F).

Data and Statistical Analysis

For whole cell dendritic arbor reconstruction and analysis of dendritic morphology, 3-D stacks were manually traced in Neurolucida (MicroBrightField, Inc., Williston, VT). The main apical trunk of each cell was excluded from analysis as its orientation was perpendicular to image stacks and thus could not be reconstructed at high resolution. Dendrites are defined as dendritic segments stretching from one branch point to the next branch point or from on branch point to the branch tip. Dendritic spine and inhibitory synapse tracking and analysis was performed using V3D (Peng et al., 2010). Dendritic spine analysis criteria were as previously described (Holtmaat et al., 2009). Using these scoring criteria, the lack of image volume rotation from imaging session to session may have resulted in some z-projecting dendritic spines being left unscored. This did not influence quantification of spine dynamics due to their low incidence and the fractional scoring. Inhibitory synapses were identified as puncta co-localized to the dendrite of interest with a minimal size of 3×3 or 8–9 clustered pixels (0.56 μm2) with a minimal average signal intensity of at least 4 times above shot noise background levels. Comparing the measured pixel dimensions of two-photon imaged synapses with their size measured after EM reconstruction, shows that the pixel dimensions of these synapses range from 8 – 31 pixel clusters and correlate with their true physical dimensions (Figure S2G). This confirms that a threshold of 3×3 pixels would be sufficient for identifying virtually any synapse.

Transient changes were defined as dendritic spines or synapses that appeared or disappeared for only one imaging session. For persistent changes, spines or synapses that appeared and persisted for at least two consecutive imaging sessions were scored as additions, with the exception of additions occurring between the second-to-last and last imaging session. Spines or synapse that disappeared and remained absent for at least two consecutive imaging sessions were scored as eliminations, with the exception of eliminations occurring between the first and second imaging session (see Supplemental Experimental Procedures). Only persistent spine and synapse changes were used for measuring turnover rates and clustered dynamics. In total, 2230 dendritic spines and 1211 inhibitory synapses from 83 dendritic segments in 14 cells from 6 animals were followed over 6 imaging sessions.

For each cell, the fractional rate of additions and eliminations were defined as the percentage of dendritic spines or inhibitory synapses added or eliminated, respectively, between two successive imaging sessions out of the total number of dendritic spines or inhibitory synapses divided by the number of days between imaging sessions. Wilcoxon rank sum test, Mann Whitney U-test, or repeated measures ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc test were used for statistical analysis of time course data or dendritic density where n indicates the number of cells or dendritic segments. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used for statistical analysis of nearest neighbor distance distributions where n indicates the number of dendritic spines or inhibitory synapses. All error bars are s.e.m.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Simultaneous in vivo two-photon imaging of inhibitory synapses and dendritic spines

Differential distribution and kinetics of inhibitory spine and shaft synapses

Experience differentially drives inhibitory spine and shaft synapse dynamics

Inhibitory synapse and dendritic spine dynamics are locally clustered

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Nedivi lab and Dr. W.C.A. Lee for comments on the manuscript; K. Deisseroth, J. Coleman, and Y. Murata for plasmid reagents; S. Hata and H. Kita (NIPS) for serial EM reconstruction; G. Flanders for immunohistochemistry. This work was sponsored by a grant to E.N. from the National Eye Institute (R01 EY017656). J.W.C. was supported in part by the Singapore-MIT Alliance-2 and Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology. Y.K. was supported by a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas: Neural creativity for communication (No.4103) (22120518) of MEXT, Japan.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions: J.L.C. and E.N. designed in vivo imaging studies; J.L.C. and K.V. performed research and analyzed data; Y.K. performed electron microscopy studies and their interpretation; J.W.C and P.T.S. contributed new reagents/analytic tools for dual color two-photon microscopy; J.L.C. and E.N. wrote the paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Atasoy D, Aponte Y, Su HH, Sternson SM. A FLEX switch targets Channelrhodopsin-2 to multiple cell types for imaging and long-range circuit mapping. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7025–7030. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1954-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey CH, Kandel ER. Structural changes accompanying memory storage. Annu Rev Physiol. 1993;55:397–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.55.030193.002145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonomano DV, Merzenich MM. Cortical plasticity: from synapses to maps. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1998;21:149–186. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JL, Lin WC, Cha JW, So PT, Kubota Y, Nedivi E. Structural basis for the role of inhibition in facilitating adult brain plasticity. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:587–594. doi: 10.1038/nn.2799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AM, Banker G, Chang W, McGrath ME, Serpinskaya AS. Clustering of gephyrin at GABAergic but not glutamatergic synapses in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3166–3177. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-10-03166.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFelipe J, Alonso-Nanclares L, Arellano JI. Microstructure of the neocortex: comparative aspects. J Neurocytol. 2002;31:299–316. doi: 10.1023/a:1024130211265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel MY, Sawtell NB, Diogo AC, Yoon B, Neve RL, Bear MF. Instructive effect of visual experience in mouse visual cortex. Neuron. 2006;51:339–349. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann JC, Kins S, Rostaing P, El Far O, Kirsch J, Sheng M, Triller A, Betz H, Kneussel M. Gephyrin interacts with Dynein light chains 1 and 2, components of motor protein complexes. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5393–5402. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-13-05393.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding NL, Staff NP, Spruston N. Dendritic spikes as a mechanism for cooperative long-term potentiation. Nature. 2002;418:326–331. doi: 10.1038/nature00854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan A, Israely I, Huang SY, Tonegawa S. The dendritic branch is the preferred integrative unit for protein synthesis-dependent LTP. Neuron. 2011;69:132–146. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan A, Kelleher RJ, Tonegawa S. A clustered plasticity model of long-term memory engrams. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:575–583. doi: 10.1038/nrn1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradinaru V, Zhang F, Ramakrishnan C, Mattis J, Prakash R, Diester I, Goshen I, Thompson KR, Deisseroth K. Molecular and cellular approaches for diversifying and extending optogenetics. Cell. 2010;141:154–165. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harauzov A, Spolidoro M, DiCristo G, De Pasquale R, Cancedda L, Pizzorusso T, Viegi A, Berardi N, Maffei L. Reducing intracortical inhibition in the adult visual cortex promotes ocular dominance plasticity. J Neurosci. 2010;30:361–371. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2233-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey CD, Svoboda K. Locally dynamic synaptic learning rules in pyramidal neuron dendrites. Nature. 2007;450:1195–1200. doi: 10.1038/nature06416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey CD, Yasuda R, Zhong H, Svoboda K. The spread of Ras activity triggered by activation of a single dendritic spine. Science. 2008;321:136–140. doi: 10.1126/science.1159675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He HY, Hodos W, Quinlan EM. Visual deprivation reactivates rapid ocular dominance plasticity in adult visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2006;26:2951–2955. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5554-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendry SH, Jones EG. Reduction in number of immunostained GABAergic neurones in deprived-eye dominance columns of monkey area 17. Nature. 1986;320:750–753. doi: 10.1038/320750a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer SB, Mrsic-Flogel TD, Bonhoeffer T, Hubener M. Experience leaves a lasting structural trace in cortical circuits. Nature. 2009;457:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature07487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmaat A, Bonhoeffer T, Chow DK, Chuckowree J, De Paola V, Hofer SB, Hubener M, Keck T, Knott G, Lee WC, et al. Long-term, high-resolution imaging in the mouse neocortex through a chronic cranial window. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1128–1144. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmaat A, Svoboda K. Experience-dependent structural synaptic plasticity in the mammalian brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:647–658. doi: 10.1038/nrn2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmaat AJ, Trachtenberg JT, Wilbrecht L, Shepherd GM, Zhang X, Knott GW, Svoboda K. Transient and persistent dendritic spines in the neocortex in vivo. Neuron. 2005;45:279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG, Powell TP. Morphological variations in the dendritic spines of the neocortex. J Cell Sci. 1969;5:509–529. doi: 10.1242/jcs.5.2.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalatsky VA, Stryker MP. New paradigm for optical imaging: temporally encoded maps of intrinsic signal. Neuron. 2003;38:529–545. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanemoto Y, Matsuzaki M, Morita S, Hayama T, Noguchi J, Senda N, Momotake A, Arai T, Kasai H. Spatial distributions of GABA receptors and local inhibition of Ca2+ transients studied with GABA uncaging in the dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Kubota Y. Neurochemical features and synaptic connections of large physiologically-identified GABAergic cells in the rat frontal cortex. Neuroscience. 1998;85:677–701. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00685-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck T, Scheuss V, Jacobsen RI, Wierenga CJ, Eysel UT, Bonhoeffer T, Hubener M. Loss of sensory input causes rapid structural changes of inhibitory neurons in adult mouse visual cortex. Neuron. 2011;71:869–882. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott GW, Holtmaat A, Wilbrecht L, Welker E, Svoboda K. Spine growth precedes synapse formation in the adult neocortex in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1117–1124. doi: 10.1038/nn1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott GW, Quairiaux C, Genoud C, Welker E. Formation of dendritic spines with GABAergic synapses induced by whisker stimulation in adult mice. Neuron. 2002;34:265–273. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota Y, Hatada S, Kondo S, Karube F, Kawaguchi Y. Neocortical inhibitory terminals innervate dendritic spines targeted by thalamocortical afferents. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1139–1150. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3846-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota Y, Hatada SN, Kawaguchi Y. Important factors for the three-dimensional reconstruction of neuronal structures from serial ultrathin sections. Front Neural Circuits. 2009;3:4. doi: 10.3389/neuro.04.004.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkum ME, Nevian T. Synaptic clustering by dendritic signalling mechanisms. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008;18:321–331. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WC, Chen JL, Huang H, Leslie JH, Amitai Y, So PT, Nedivi E. A dynamic zone defines interneuron remodeling in the adult neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19968–19973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810149105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois C, Hong EJ, Pease S, Brown EJ, Baltimore D. Germline transmission and tissue-specific expression of transgenes delivered by lentiviral vectors. Science. 2002;295:868–872. doi: 10.1126/science.1067081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YM, Mansuy IM, Kandel ER, Roder J. Calcineurin-mediated LTD of GABAergic inhibition underlies the increased excitability of CA1 neurons associated with LTP. Neuron. 2000;26:197–205. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major G, Polsky A, Denk W, Schiller J, Tank DW. Spatiotemporally graded NMDA spike/plateau potentials in basal dendrites of neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:2584–2601. doi: 10.1152/jn.00011.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marik SA, Yamahachi H, McManus JN, Szabo G, Gilbert CD. Axonal dynamics of excitatory and inhibitory neurons in somatosensory cortex. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markram H, Toledo-Rodriguez M, Wang Y, Gupta A, Silberberg G, Wu C. Interneurons of the neocortical inhibitory system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:793–807. doi: 10.1038/nrn1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden KC, Shemesh A, Bayer KU, Carroll RC. Selective translocation of Ca2+/calmodulin protein kinase IIalpha (CaMKIIalpha) to inhibitory synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20559–20564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010346107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maya Vetencourt JF, Sale A, Viegi A, Baroncelli L, De Pasquale R, O’Leary OF, Castren E, Maffei L. The antidepressant fluoxetine restores plasticity in the adult visual cortex. Science. 2008;320:385–388. doi: 10.1126/science.1150516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles R, Toth K, Gulyas AI, Hajos N, Freund TF. Differences between somatic and dendritic inhibition in the hippocampus. Neuron. 1996;16:815–823. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80101-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng H, Ruan Z, Long F, Simpson JH, Myers EW. V3D enables real-time 3D visualization and quantitative analysis of large-scale biological image data sets. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:348–353. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters A. Examining neocortical circuits: some background and facts. J Neurocytol. 2002;31:183–193. doi: 10.1023/a:1024157522651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinson DA, Dillon CP, Kwiatkowski AV, Sievers C, Yang L, Kopinja J, Rooney DL, Zhang M, Ihrig MM, McManus MT, et al. A lentivirus-based system to functionally silence genes in primary mammalian cells, stem cells and transgenic mice by RNA interference. Nat Genet. 2003;33:401–406. doi: 10.1038/ng1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Stryker MP. Distinctive features of adult ocular dominance plasticity. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10278–10286. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2451-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller J, Schiller Y, Stuart G, Sakmann B. Calcium action potentials restricted to distal apical dendrites of rat neocortical pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 1997;505(Pt 3):605–616. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.605ba.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt B, Knaus P, Becker CM, Betz H. The Mr 93,000 polypeptide of the postsynaptic glycine receptor complex is a peripheral membrane protein. Biochemistry. 1987;26:805–811. doi: 10.1021/bi00377a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjostrom PJ, Rancz EA, Roth A, Hausser M. Dendritic excitability and synaptic plasticity. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:769–840. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spolidoro M, Sale A, Berardi N, Maffei L. Plasticity in the adult brain: lessons from the visual system. Exp Brain Res. 2009;192:335–341. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1509-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruston N. Pyramidal neurons: dendritic structure and synaptic integration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:206–221. doi: 10.1038/nrn2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata H, Nakajima K. Efficient in utero gene transfer system to the developing mouse brain using electroporation: visualization of neuronal migration in the developing cortex. Neuroscience. 2001;103:865–872. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triller A, Cluzeaud F, Pfeiffer F, Betz H, Korn H. Distribution of glycine receptors at central synapses: an immunoelectron microscopy study. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:683–688. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.2.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierenga CJ, Becker N, Bonhoeffer T. GABAergic synapses are formed without the involvement of dendritic protrusions. Nat Neurosci. 2008 doi: 10.1038/nn.2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.