This report of an atypical cause of bowel obstruction suggests that laparoscopic intervention may be successfully used in the diagnosis and treatment of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia.

Keywords: Intrathoracic gallbladder, Bowel obstruction, Laparoscopic surgery, Right diaphragmatic hernia, Delayed diaphragmatic rupture

Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Diaphragmatic rupture is a serious complication of both blunt and penetrating abdominal trauma. In the acute setting, delay in diagnosis can lead to severe cardiovascular and respiratory compromise. Chronic cases can present years later with a plethora of clinical symptoms. Laparoscopic techniques are being increasingly utilized in the diagnosis and treatment of traumatic diaphragmatic hernias.

Method:

We describe a case of a 70-year-old female who presented with signs and symptoms of a small bowel obstruction. She was ultimately found to have an obstruction secondary to a chronic traumatic diaphragmatic hernia with an intrathoracic gallbladder and incarcerated small intestine. A cholecystectomy and diaphragmatic hernia repair were both performed laparoscopically. This case report presents an atypical cause of bowel obstruction and reviews the current literature on laparoscopic management of traumatic diaphragmatic hernias.

Results and Conclusion:

Laparoscopy is increasingly used in the diagnosis and treatment of traumatic diaphragmatic hernias with good results.

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic diaphragmatic hernias have been well described after blunt trauma. Diaphragmatic ruptures can occur in up to 0.8% to 7% of blunt abdominal trauma, with large left-sided defects being the most common.1–4 If the injury is not recognized, progressive herniation of abdominal contents may ensue. It is estimated that approximately 40% to 62% of ruptured diaphragms are missed during the acute hospital stay.1 The time delay to presentation has been reported to be from several weeks to 50 years.3

Although minimally invasive techniques have been utilized in the surgical repair of both acute diaphragmatic lacerations and chronic traumatic diaphragmatic hernias, its use has not been well defined or universally accepted.

CASE REPORT

A 70-year-old female was admitted after being found obtunded at home secondary to a possible narcotic overdose. The patient was found to have rhabdomyolysis and treated accordingly.

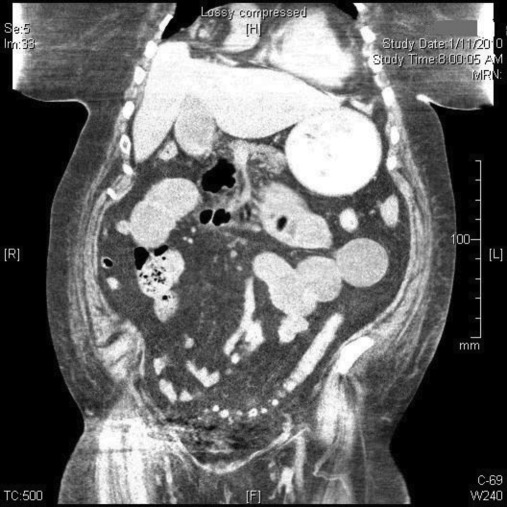

She then developed nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. A computed tomography (CT) scan of her abdomen and pelvis was obtained, and revealed severely dilated proximal small bowel loops with evidence of a decompressed distal small bowel consistent with a small bowel obstruction (Figure 1). She was initially treated with nasogastric tube decompression.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography (CT) scan of abdomen and pelvis showing proximal small bowel obstruction, note gallbladder in the right pleural cavity.

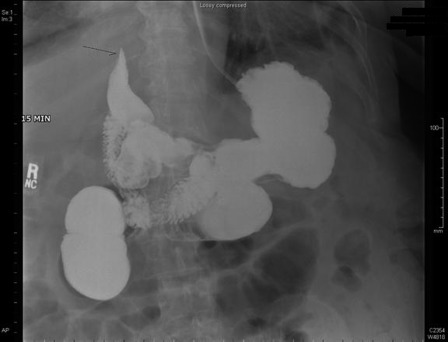

After 72 hours, it was felt that the patient had failed conservative management. She underwent a small bowel follow through (SBFT) that showed emptying of the stomach into the duodenum with flow in the proximal jejunum; however, a bird's beak appearance was found in the right upper quadrant (Figure 2). Because of her unresolved obstruction and uncommon finding on SBFT, the patient was taken to the operating room for a diagnostic laparoscopy.

Figure 2.

Small bowel follow through (SBFT) showing bird's beak appearance in the right upper quadrant.

Intraoperatively, the patient was found to have a bisected liver along the common hepatic duct at Cantrell's line. A chronic, right traumatic diaphragmatic hernia containing the gallbladder and a transition point at which the small bowel was obstructed were identified. The patient had a remote history of a motor vehicle accident 41 years earlier that resulted in a “liver fracture,” which was treated nonoperatively, although she relayed that she was in the intensive care unit for “quite some time.” The gallbladder itself was inflamed, so a cholecystectomy with intraoperative cholangiogram (IOC) via the cystic duct stump was performed. The IOC verified an elongated common hepatic duct, cystic duct, and common bile duct. There was no extravasation, and the contrast flowed nicely into the duodenum without evidence of choledocholithiasis.

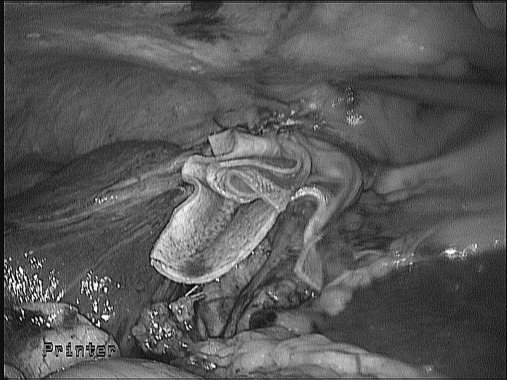

With all the contents fully reduced from the diaphragmatic hernia, lung tissue was clearly identified. There was also evidence of chronic inflammation of the pleura that was adherent to the posterior wall of the diaphragmatic defect. A plug and patch was constructed out of a piece of biologic mesh (Flex HD, Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH) to fill the defect. Utilizing intracorporeal 0-Ethibond sutures, the biologic mesh plug was tacked to the anterior, medial, and lateral aspects of the hernia defect (Figure 3). The posterior margin was the common duct, and no sutures could be place here. The end result was a strong repair of the diaphragmatic hernia performed laparoscopically using a biologic mesh. The patient was taken to the surgical intensive care unit where she was extubated on the first postoperative day. Her nasogastric tube was removed on postoperative day 2, and she was discharged to an extended care facility on postoperative day 6.

Figure 3.

Biologic mesh plug tacked to the anterior, medial and lateral aspects of the hernia defect.

Unfortunately, the patient was readmitted one week later with a bile leak and a bilious effusion of the right pleural space. She underwent an ERCP with stent placement, and a right VATS procedure with pleurodesis for an empyema. Because the mesh plug was of biologic material, it did not necessitate removal. The patient went on to recover uneventfully from this complication and was discharged to an extended care facility.

DISCUSSION

Abdominal organ herniation was first described by Sennertus in 1541. Since then, multiple reports have detailed the mechanism of injury, a variety of presenting symptoms, various unusual hernia contents, and techniques for repair. There have only been a few case reports in the literature describing liver, gallbladder, kidney, and even ovarian contents in the thorax as a result of chronic traumatic diaphragmatic hernia.2,5–7 There have also been 12 reported cases in the literature of a tension fecopneumothorax related to traumatic diaphragmatic hernia.8 The majority (90%) of herniations occur on the left side.9 This is thought to be because the liver protects the right hemidiaphragm from injury and the relative weakness of the posterolateral area of the left hemidiaphragm as it originates from the pleuroperitoneal membrane.

The major challenge in caring for traumatic diaphragmatic hernias is the diagnosis. Missed diaphragmatic ruptures may present years after the inciting trauma with mutivisceral herniation as well as risk of life-threatening complications, such as visceral strangulation or perforation, cardiovascular, or respiratory compromise.10–12 Despite advances in imaging technology, 30% to 50% are missed during the initial presentation, especially if on the right. CT scans often fail to pick up right-sided lesions, because this side blends in and is virtually inseparable from the contour of the liver.3 MRI scans have a better diagnostic yield, although they add a significant cost and, as with CT scans, should only be done on stable patients. With the advancement of minimally invasive techniques, thoracoscopy and laparoscopy have been found to have both excellent diagnostic and promising therapeutic benefits.

Both thoracoscopic and laparoscopic approaches have been described in the repair of diaphragmatic hernias.9,13–15 The advantages of these repairs over open surgery include minimal trauma, earlier recovery, and decreased hospital stay. While laparoscopy allows for better reduction of hernia contents and evaluation of both hemidiaphragms, thoracoscopy only allows for inspection of one hemidiaphragm at a time. Ideally, repair of the defect is performed primarily with horizontal mattress nonabsorbable suture.1 In the case of larger defects, prosthetic mesh may be needed. In our case, we used a biologic mesh (FlexHD) for repair as cholecystectomy was needed. In retrospect, this decision was prudent in light of the empyema that developed as a result of the bile leak. This biologic mesh did not require removal, as a prosthetic mesh in an infected field likely would have. The disadvantage of using a biologic mesh is the long-term durability of the mesh. A recent multicenter, prospective, randomized trial by Oelschlager et al16 comparing primary diaphragm repair with primary repair buttressed with a biologic prosthesis concluded that the radiologic hiatal hernia recurrence was significantly higher (P=0.04) with primary repair (24%) than with buttressed repair (9%) after 6 months; however, the second phase of this trial determining the long-term durability of biologic mesh-buttressed repair revealed that at a median follow-up of 58 months, recurrence rates reached 59% in the primary repair group and an increase to 54% in the buttressed repair group (P=.7).17 A literature review regarding use of biologic mesh and hiatal hernia repairs by Antoniou et al18 describes a range of recurrence rates from 3.8% to 54%.

The use of therapeutic laparoscopy should be limited to the treatment of trauma patients with an isolated diaphragmatic injury, because the rate of missing associated abdominal injuries is as high as 41%.14 Because the role of diagnostic laparoscopy in the trauma patient is still evolving, and most patients will have a clinical or radiographic indication for laparotomy, most patients will not be candidates for laparoscopic repair in the acute period. If, however, concomitant injuries can be ruled out, laparoscopy may be considered. Protocols for the selection of these patients are not currently in place and are a promising area of continued research. In the chronic setting, laparoscopy is a useful tool for both diagnosis and treatment and seems to offer the same patient benefits seen with the laparoscopic repair of congenital diaphragmatic defects.

CONCLUSION

Diagnosis of a traumatic diaphragmatic hernia in the acute setting can be very challenging. In the chronic period, a myriad of symptoms and radiologic findings may arise. Though right-sided traumatic diaphragmatic hernias occur much less frequently than left-sided ones, they are being discovered with increasing frequency. Plain films, CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and even diagnostic laparoscopy can aid in the diagnosis. Laparoscopy is a safe and feasible method for repairing traumatic diaphragmatic hernias, especially in the chronic setting, with the advantage of evaluating the entire abdomen and both hemidiaphragms simultaneously.

References:

- 1. Crandall M, Popowich D, Shapiro M, West M. Posttraumatic hernias: historical overview and review of the literature. Am Surg. 2007. September;73(9):845–850 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seket B, Henry L, Adham M, Partensky C. Right-sided posttraumatic diaphragmatic rupture and delayed hepatic hernia. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009. Mar-Apr;56(90):504–507 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Singh S, Kalan MM, Moreyra CE, Buckman RF., Jr Diaphragmatic rupture presenting 50 years after the traumatic event. J Trauma. 2000. July;49(1):156–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wood NE, Stutzman FL. Right diaphragmatic hernia secondary to trauma; with report of two cases. Calif Med. 1959. November;91:25–254 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Neal JW. Traumatic right diaphragmatic hernia with evisceration of stomach, transverse colon and liver into the right thorax. Ann Surg. 1953. February;137(2):281–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rimpiläinen J, Kariniemi J, Wiik H, Biancari F, Juvonen T. Post-traumatic herniation of the liver, gallbladder, right colon, ileum, and right ovary through a Bochdalek hernia. Eur J Surg. 2002;168(11):646–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Evans CJ, Simpson JA. Fifty-seven cases of diaphragmatic hernia and eventration. Thorax. 1950. December;5(4):343–361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Khan MA, Verma GR. Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia presenting as a tension fecopneumothorax. Hernia. 2011. February;15(1):97.9 Epub 2010 Jan 7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rossetti G, Brusciano L, Maffettone V, et al. Giant right post-traumatic hernia: laparoscopic repair without mesh. Chir Ital. 2005. Mar-Apr;57(2):243–246 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Peker Y, Tatar F, Kahya MC, Cin N, Derici H, Reyhan E. Dislocation of three segments of the liver due to hernia of the right diaphragm: report of a case and review of the literature. Hernia. 2007. February;11(1):63–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Christie DB, 3rd, Chapman J, Wynne JL, Ashley DW. Delayed right-sided diaphragmatic rupture and chronic herniation of unusual abdominal contents. J Am Coll Surg. 2007. January;204(1):176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Purdy MR. Large-bowel obstruction as a result of traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. S Afr Med J. 2007. March;97(3):180–182 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mizobuchi T, Iwai N, Kohno H, Okada N, Yoshioka T, Ebana H. Delayed diagnosis of traumatic diaphragmatic rupture. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009. August;57(8):430–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McCutcheon BL, Chin UY, Hogan GJ, Todd JC, Johnson RB, Grimm CP. Laparoscopic repair of traumatic intrapericardial diaphragmatic hernia. Hernia. 2010. December;14:647–649 Epub 2009 Dec 1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ver MR, Rakhlin A, Baccay F, Kaul B, Kaul A. Minimally invasive repair of traumatic right-sided diaphragmatic hernia with delayed diagnosis. JSLS. 2007;11:481–486 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA, Hunter J, et al. Biologic prosthesis reduces recurrence after laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2006. October;244(4):481–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA, Hunter J, et al. Biologic prosthesis to prevent recurrence after laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: long-term follow-up from a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2011. June 28 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Antoniou SA, Pointner R, Granderath FA. Hiatal hernia repair with the use of biologic meshes: a literature review. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011. February;21(1):1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]