The authors suggest that the small bowel be assessed in all appendectomy cases for a pathological Meckel's diverticulum.

Keywords: Meckel's diverticulum, Appendicitis, Laparoscopic, Internal hernia, Omphalomesenteric duct, Small bowel obstruction

Abstract

Background:

Meckel's diverticulum is a congenital anomaly resulting from incomplete obliteration of the omphalomesenteric duct. The incidence ranges from 0.3% to 2.5% with most patients being asymptomatic. In some cases, complications involving a Meckel's diverticulum may mimic other disease processes and obscure the clinical picture.

Methods:

This case presents an 8-year-old male with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting and an examination resembling appendicitis.

Results:

A CT scan revealed findings consistent with appendicitis with dilated loops of small bowel. During laparoscopic appendectomy, the appendix appeared unimpressive, and an inflamed Meckel's diverticulum was found with an adhesive band creating an internal hernia with small bowel obstruction. The diverticulum was resected after the appendix was removed.

Conclusion:

The incidence of an internal hernia with a Meckel's diverticulum is rare. A diseased Meckel's diverticulum can be overlooked in many cases, especially in those resembling appendicitis. It is recommended that the small bowel be assessed in all appendectomy cases for a pathological Meckel's diverticulum.

INTRODUCTION

Meckel's diverticulum is the most common congenital abnormality of the gastrointestinal tract.1–4 It is a true diverticulum containing all layers of the intestinal wall.5 This embryonic remnant arises from the antimesenteric border of the ileum.5 The diverticular remnant of the omphalomesenteric or vitelline duct was described in detail by Johann Meckel in 1808.1,5 As the embryonic yolk sac enlarges, it develops a connection to the primitive gut via the vitelline duct. Typically this duct obliterates in the embryo by the fifth to ninth week during the progression and rotation of the foregut and hindgut. As this occurs, the yolk sac also begins to atrophy.6 In 0.3% to 2.5% of the population, this vitelline duct persists to become a Meckel's diverticulum.1,6,7 The yolk sac is supplied by 2 vitelline arteries, one of which degenerates as the yolk sac atrophies, while the remaining artery develops into the superior mesenteric artery.6 When one of the vitelline arteries fails to degenerate, it develops into a peritoneum covered fibrous band, or a mesodiverticular band.6 It is usually attached from the tip of the Meckel's diverticulum to the ileal mesentery and is often the cause of a small bowel obstruction, as is presented in this case.

CASE REPORT

An 8-year-old male presented to the emergency room with complaints of abdominal pain with nausea and vomiting for 2 days. He described crampy pain in the periumbilical region with associated episodes of diarrhea. The pain was accompanied by a loss of appetite for 2 days and a subjective fever. The past medical history was significant for astigmatism. There was no surgical history. The patient's family and social history was noncontributory.

On examination, vital signs revealed a temperature of 97.3°F, blood pressure of 121/72, heart rate of 102, and respirations of 20. The patient appeared to be in distress and remained in a fetal position during examination. The abdominal examination revealed a distended abdomen with the presence of normal bowel sounds. There was tenderness to palpation in the periumbilical region and right lower quadrant with the presence of rebound tenderness across the lower abdomen. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable. Laboratory testing revealed a mild leukocytosis of 13,400 cells/mm3. The remainder of the blood cell count and electrolytes were normal, including amylase and lipase levels.

Flat and upright abdominal films showed multiple mildly distended small bowel loops with the presence of air fluid levels. An ultrasound of the abdomen revealed a dilated tubular viscus in the right lower quadrant with a large amount of fluid in the pelvis. A CT was recommended for suspicion of acute appendicitis. The abdominal CT demonstrated a dilated and inflamed appendix with distended loops of small bowel and free fluid in the pelvis.

METHODS

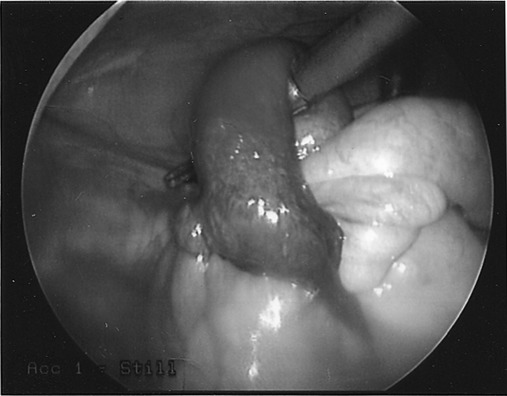

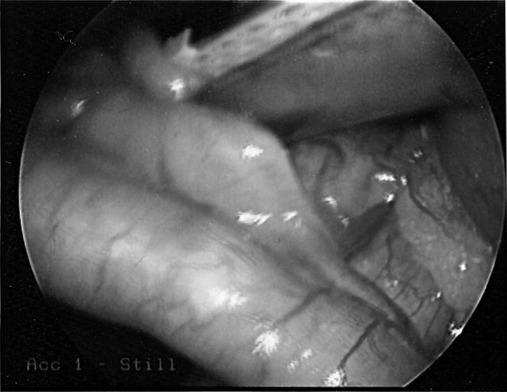

Emergent laparoscopy revealed a mildly inflamed appendix. However, the extent of inflammation was not sufficient to explain the patient's overall presentation. After the appendectomy was performed, the remainder of the bowel was re-assessed. Although not seen initially, careful laparoscopic exploration of the small bowel revealed an extensively inflamed Meckel's diverticulum in the distal ileum. An adhesive band from the Meckel's diverticulum had created an internal hernia resulting in a partial small bowel obstruction (Figure 1). There was no evidence of necrosis or ischemia. The band was divided with electrocautery and a diverticulectomy was performed with an endoscopic gastrointestinal stapler (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Meckel's diverticulitis and adhesive band causing internal hernia.

Figure 2.

Meckel's diverticulitis.

RESULTS

The patient's hospital course was uneventful, leading to a discharge on postoperative day 3. The final pathology report revealed an acutely inflamed Meckel's diverticulum without the presence of ectopic gastric or pancreatic mucosa. The appendix was mildly inflamed. At 2-week follow-up, the patient was without pain and was tolerating a regular diet.

DISCUSSION

The lifetime risk of complications of a Meckel's diverticulum, including diverticulitis, bleeding and obstruction, is approximately 4% to 6%,2–4,8,9 and 40% of these occur in children younger than age 10.9 It is difficult to diagnose preoperatively, because its presentation commonly mimics such disorders as appendicitis, peptic ulcer disease, and Crohn's-appendicitis being the most common preoperative diagnosis.1,10 Therefore, a complicated Meckel's diverticulum should be considered in any patient with unexplained abdominal pain, particularly younger patients.

The most common complications of Meckel's diverticulum are inflammation and obstruction caused by an adhesive fibrous band or internal hernia.1–3,11 Small bowel obstruction is associated with approximately 30% of symptomatic diverticula,3,12 and is a common cause of small bowel obstruction in the virgin abdomen.11 In a few reported cases, small bowel obstruction was also caused by enterolithiasis and phytobezoars.12,13 A retrospective study in 1996 of 84 patients with Meckel's diverticula reported a 10% incidence of symptomatic enterolithiasis.13 A thickened portion of the diverticulum may also suggest ectopic gastric or pancreatic tissue. Ectopic mucosa carries an incidence of 10% to 20% and requires resection of the involved segment of ileum to prevent further complications such as bleeding.7 The average size is 3cm, with 90% between 1cm and 10cm. Larger diverticula are more susceptible to complications.14

Rarely has a Meckel's diverticulum been known to result in intussusception. The first such reported case to be treated laparoscopically in 2003 involved an ileoileal intussusception diagnosed by small bowel enteroclysis with a bird-beak appearance at the distal ileum. The intussusception was reduced laparoscopically followed by a segmental ileal resection and extracorporeal anastomosis.15 Bleeding and intussusception tend to occur more often under the age of 2, while obstruction and inflammation are more common in adults.3,4,7

Efficacy of diagnostic imaging varies with this disease process. Plain films are usually nonspecific. Radionuclide scintigraphy will detect 85% of Meckel's cases if ectopic gastric mucosa is present in the diverticulum. Enteroclysis may also detect a smaller percentage of diverticula, ranging up to 75%.3,4 Abdominal CT may yield a high rate of diagnosis when small bowel obstruction is present (81% to 96%), but a Meckel's etiology is difficult to identify as a cause due to the inability to distinguish a diverticulum amongst loops of small bowel.3

In a 2005 retrospective study, Ueberrueck et al16 analyzed the significance of Meckel's diverticulum in cases diagnosed as appendicitis. In a 26-year period, a total of approximately 10 000 appendectomies were performed. The bowel was explored to search for a Meckel's diverticulum in approximately 80% of these cases. The presence of a Meckel's was discovered in 3% of these cases, while 9% of these diverticula were found to have pathology, including obstruction, diverticulitis, perforation, and intussusception. This study concluded in establishing the importance of exploring the bowel in all appendectomy cases.16

After removal of a complicated Meckel's, the postoperative morbidity has been reported to be 12% while mortality is 2%. In incidentally removed diverticula, the rates are 2% and 1%, respectively.1,4,14,17 Although controversial, many surgeons recommend removing incidentally discovered Meckel's based on the low postoperative complication rate. These rates were found in a definitive study at the Mayo Clinic in 1994, supporting the role of prophylactic diverticulectomy. The risks of complications of Meckel's diverticula remained constant over all age groups at 6.4%, while the postoperative morbidity and mortality rates were much more favorable in asymptomatic, incidental diverticulectomies (Table 1).4,14,17

Table 1.

Morbidity and Mortality

| Meckel's Diverticulectomy | Morbidity | Mortality |

|---|---|---|

| Pathologic | 12% | 2% |

| Incidental | 2% | 1% |

CONCLUSION

Meckel's diverticulum is the most common congenital gastrointestinal abnormality. Although present in only a small percentage of the population, the complications of a Meckel's diverticulum can be severe. Due to the difficulty in diagnosing a pathologic Meckel's preoperatively, many surgeons recommend prophylactic diverticulectomy in those found incidentally. This recommendation is based on lower morbidity rates when compared to resection of pathologic diverticula. This is also supported by evidence that all age groups have an equal incidence of developing a complicated Meckel's diverticula. A thorough exploration of the small bowel should also be performed in suspected cases of appendicitis. Laparoscopy is feasible and ideal in such cases and can be performed safely in the hands of experienced surgeons.10

References:

- 1. Altinli E, Pekmezci S, Gorgun E, Sirin F. Laparoscopy- assisted resection of complicated Meckel's diverticulum in Adults. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2002;3:190–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Matthews P, Tredgett MW, Balsitis M. Small bowel strangulation and infarction: an unusual complication of Meckel's diverticulum. J R Coll Surg Edinburgh. 1996;41:54–56 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Murakami R, Sugizaki K, Kobayashi Y, et al. Strangulation of small bowel due to Meckel diverticulum: CT findings. Clin Imaging. 1999;23:181–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nath DS, Morris TA. Small bowel obstruction in an adolescent. A case of Meckel's diverticulum. Minn Med. 2004;46–48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vork JC, Kristensen IB. Meckel's diverticulum and intestinal obstruction- report of a fatal case. Forensic Sci Int. 2003;138:114–1145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yoo JH, Cerqueira DS, Rodrigues AJ, Jr., Nakagawa RM, Rodrigues CJ. Unusual case of small bowel obstruction: persistence of vitelline artery remnant. Clin Anat. 2003;16:173–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Parente F, Anderloni A, Zerbi P, et al. Intermittent small bowel obstruction caused by a gastric adenocarcinoma in a Meckel's diverticulum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:180–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gamblin TC, Glenn J, Herring D, McKinney WB. Bowel obstruction caused by a Meckel's diverticulum enterolith: a case report and review of the literature. Curr Surg. 2003;60:63–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Prall RT, Bannon MP, Bharucha AE. Meckel's diverticulum causing Intestinal obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3426–3427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Senthilkumar R, Madankumar MV, Kavalakat AJ. Laparoscopic management of symptomatic Meckel's diverticula: a simple tangential stapler excision. JSLS. 2008;12:66–70 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tashjian DB, Moriarty KP. Laparoscopy for treating a small bowel obstruction due to a Meckel's diverticulum. JSLS. 2003;7:253–255 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Frazzini VI, English WJ, Bashist B, Moore E. Case report. Small bowel obstruction due to phytobezoar formation within Meckel diverticulum: CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1996;20:390–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pantongrag-Brown L, Levine MS, Buetow PC, Buck JL, Elsayed AM. Meckel's enteroliths: clinical, radiologic, and pathologic findings. Am J Radiol. 1996;167:1447–1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tan YM, Zheng ZX. Recurrent Torsion of a giant Meckel's diverticulum. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:1285–1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Karahasanoglu T, Memisoglu K, Korman U, Tunckale A, Curgunlu A, Karter Y. Adult intussusception due to inverted Meckel's diverticulum. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13:39–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ueberrueck T, Meyer L, Koch A, Hinkel M, Kube R, Gastinger I. The significance of Meckel's diverticulum in appendicitis-a retrospective analysis of 233 cases. World J Surg. 2005;29:455–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cullen JJ, Kelly KA, Moir CR, Hodge DO, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Surgical management of Meckel's diverticulum. An epidemiologic, population based study. Ann Surg. 1994;220:564–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]