The authors found that duplicated ureters was not a contraindication to robot-assisted laparoscopic radical cystoprostatectomy in this case.

Keywords: Duplicated ureter, Robotic cystoprostatectomy, Intracorporeal robotic Studer pouch formation, Invasive bladder cancer, Ureter anomaly, Frozen section

Abstract

Objectives:

Ureteric duplication is a rarely seen malformation of the urinary tract more commonly seen in females.

Materials and Methods:

We report 2 cases of robot-assisted laparoscopic radical cystoprostatectomy (RALRCP) with bilateral extended pelvic lymph node dissection and intracorporeal Studer pouch formation in patients with duplicated right ureters.

Results:

Two male patients (53 and 68 years old) underwent transurethral resection of a bladder tumor that revealed high-grade muscle invasive transitional cell carcinoma, with no metastases. We performed RALRCP and intracorporeal Studer pouch formation. A duplicated right ureter was observed during the procedures in both patients. Left ureter distal segment was spatulated 2cm long and anastomosed using running 4/0 Vicryl to the right ureter at its bifurcation where it forms a single lumen without spatulation. All 3 ureters were catheterized individually. A Wallace type uretero-ileal anastomosis was performed between the ureters and the proximal part of the Studer pouch chimney. Although ureteric frozen section analysis suggested ureteric carcinoma in situ in patient 1, postoperative pathologic evaluation was normal. Frozen section and final postoperative pathologic evaluations were normal in patient 2.

Conclusions:

Duplicated ureters might be underdiagnosed on CT. The presence of a duplicated ureter is not a contraindication to RALRCP and intracorporeal Studer pouch formation. The da Vinci-S surgical robot is very safe for performing this complicated procedure. Frozen section analysis of ureters during radical cystectomy for bladder cancer might not reliably diagnose the pathologic condition and might overestimate the disease in the ureters.

INTRODUCTION

Ureteric duplication is seen in 0.75% of the population. It is a congenital malformation of the urinary tract more commonly seen in females.1 Open radical cystectomy (RC) with urinary diversion remains the gold standard approach for the treatment of patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer and those with high-grade, recurrent, noninvasive tumors.2 However, minimally invasive surgical approaches including robot-assisted laparoscopic radical cystectomy (RALRC), which duplicates the surgical principles of the open approach, have attracted the attention of both surgeons and patients. Urinary diversion is performed extracorporeally according to most of the published literature regarding RALRC. Very few authors3–10 have reported their experience with robot-assisted intracorporeal Studer pouch formation. None of these authors had reported any experience with ureteric duplication. Therefore, we aimed to report our experience on the robotic management and doability of one of the unexpected variations of the urinary system at the time of surgery. To the best of our knowledge, robotic management of this condition has not been reported before.

Herein, we present 2 challenging cases of right ureteric duplication that we detected while performing bilateral neurovascular bundle (NVB)-sparing robot-assisted laparoscopic radical cystoprostatectomy (RALRCP) with extended pelvic lymph node (LN) dissection and intracorporeal Studer pouch formation in 53- and 68-year-old male patients with invasive bladder cancer.

CASE REPORT

Between December 2009 and December 2010, we performed 27 RALRC procedures (25 males, 2 females) with robot-assisted bilateral extended pelvic LN dissection. Of these, intracorporeal Studer pouch was performed in 23 patients, intracorporeal ileal conduit was performed in 2 patients, and open Studer pouch was performed in 2 patients. Right ureteric duplication was detected in 2 male patients in whom we performed RALRCP and intracorporeal Studer pouch formation.

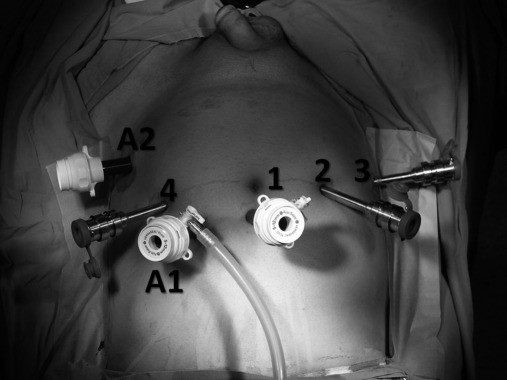

Overall, 6 trocars were used for this procedure: a 12-mm port for robotic 3D lens, three 8-mm robotic ports for robotic arms, a 12-mm port for assistant surgeon, and a 15-mm port for introducing the bowel stapler (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Appearance of the abdomen with inserted trocars for performing robot-assisted laparoscopic radical cystoprostatectomy and intracorporeal Studer pouch formation. 1: camera-port site (12mm) 2, 3 and 4: robotic-port sites (8mm) A1: assistant port-site (12mm) A2: assistant port-site used for introducing tissue stapler (15mm).

Case One

A 53-year-old male patient underwent transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TUR-BT) located on the left posterolateral aspect of the bladder, which revealed high-grade muscle invasive transitional cell carcinoma (TCC). The patient was then referred to our institution. No metastatic disease was detected on radiological evaluation of the patient including abdominopelvic ultrasound, computerized tomography (CT), and chest X-rays. Minimal dilatation of the both ureters and collecting systems of the kidneys were demonstrated on CT. The patient's preoperative International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) score was 51.

Surprisingly, incomplete duplication of the right ureter was observed during the procedure. Distally, both ureters were joining and running as a single segment at about 2cm in length before entering the bladder. Intraoperative frozen section analysis of the biopsy taken from this segment revealed carcinoma in situ; therefore, the distal right ureter was excised until the beginning of the duplication. Another frozen section biopsy was sent at this level, which revealed normal ureteric tissue without any tumor. Frozen section analysis of the biopsy taken from the left distal ureteric end was reported as normal.

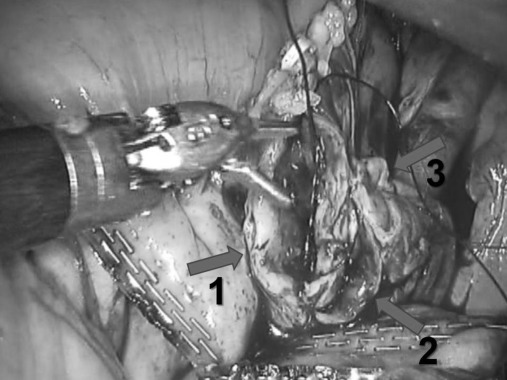

Following preservation of the 20-cm long distal segment of the terminal ileum, a 45-cm long ileum segment was used to form a Studer pouch intracorporeally. The left ureter distal segment was spatulated in 2-cm lengths. The spatulated left single ureter was anastomosed to the right ureter at the level of its bifurcation where it forms a single lumen without spatulation by using running 4/0 Vicryl (Figure 2). All 3 ureters were catheterized individually with 3 ureter catheters, and a Wallace type uretero-ileal anastomosis was performed between the ureters and the proximal part of the Studer pouch chimney. Then, the uretero-ileal anastomosis segment was retroperitonealized.

Figure 2.

Spatulated left ureter is anastomosed to duplicated right ureter at the level of bifurcation. 1: Left single ureter 2 and 3: Duplicated right ureters.

Extended lymph-node dissection was carried out up to the level of the aortic bifurcation and the presacral area. The whole procedure was completed successfully in 9 hours without any complications, and intraoperative blood loss was 150cc.

No residual tumor was detected (pT0) on postoperative pathological evaluation of the cystoprostatectomy specimen with negative surgical margins (SMs). Although intraoperative frozen section analysis was reported as carcinoma in situ (CIS) concerning the ureteral margins submitted for frozen section, no tumor was reported on final pathologic evaluation. A total of 26 lymph nodes (LN) were removed, none of which were metastatic. Currently, the patient is at the postoperative 7-month follow-up without metastatic disease on radiologic imaging. His IIEF score is 5 without any daytime incontinence.

Case Two

A 68-year-old male patient underwent TUR-BT, which revealed pT1G3 TCC of the bladder. After 1 month, a re-TUR-BT was performed that revealed high-grade muscle invasive bladder TCC. No metastatic disease was detected on radiological evaluation of the patient including abdomino-pelvic ultrasound, CT, and chest X-rays. His preoperative IIEF score was 55.

Similar to the previous patient, incomplete duplication of the right ureter was observed during the procedure that was not detected on preoperative abdomino-pelvic CT. Studer pouch and ureteric reconstruction and uretero-ileal anastomosis were performed as explained above. During performance of extended pelvic LN dissection, a 0.5-cm vena cava injury occurred that was repaired robotically. The whole procedure was completed in 10.5 hours, and intraoperative blood loss was 300 cc.

Both intraoperative frozen analysis of the ureteral margins and postoperative final pathologic evaluations were negative for tumor and/or CIS. Final postoperative pathological evaluation of the cystoprostatectomy specimen revealed a pT2a tumor with negative SMs. A total of 27 LNs were removed, none of which were metastatic. Currently, the patient is at the postoperative 5-month follow-up without metastatic disease on radiologic imaging. His IIEF score is 5 with mild daytime incontinence (1 to 2 pads/day).

DISCUSSION

Muscle invasive bladder cancer has a <15% survival rate in 2 years time if left untreated.11 It is the fifth most frequently seen malignancy and the fourth most common cause of cancer deaths in the United States.12 Currently, the standard treatment of choice for muscle invasive bladder cancer is open RC and urinary diversion, which carries the risks of significant morbidities and even mortality, although the surgical techniques have significantly improved.13

The first laparoscopic cystectomy, which is a minimally invasive procedure with less morbidity than open surgery, was reported in 1992 by Parra et al.14 Following the use of the da Vinci surgical system (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA) in urology, many centers published their experience with robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. In 2003, the first robot-assisted laparoscopic RC was reported by Menon et al.15

During RALRC, urinary diversion can be performed extracorporeally or intracorporeally. Most robotic urologic surgeons have performed extracorporeal urinary diversion following RALRC, and very few authors have reported their experience with robot-assisted intracorporeal Studer pouch formation.3–10 In addition, none of these authors has reported the presence of ureteric duplication and its robot-assisted management.3–10 Therefore, a clear answer can not be given to the question of whether robot-assisted laparoscopic reconstruction of ureteric duplication is feasible during performance of intracorporeal Studer pouch formation. To the best of our knowledge, no report has been published regarding this condition. Increased operative time seems to limit the procedure of intracorporeal pouch formation with the da Vinci robot.13 However, recent publications4 suggest that with increased experience operation time decreases significantly.

Our console surgeon (MDB) completed all procedures successfully without facing any difficulties by using the da Vinci-S 4-arm surgical robot with its advantages of 3-dimensional optical magnification, dexterity in motion, and the ability to perform tremor-free and delicate movements with 3 independent robotic arms in addition to the camera arm.

Very recently, Ng et al16 reported a comparison of postoperative complications in open (n=104) versus robotic (n=83) cystectomy. In the robotic group, blood loss and length of hospital stay were shorter compared to the open surgical group. On the 30th postoperative day, overall and major complication rates were lower in the robotic group compared to the open surgical groups. On the 90th postoperative day, the number of major complications was lower in the robotic group, whereas overall complication rates were similar in both groups. Similarly, Coward et al17 reported that operation time was longer in the robotic cystectomy group, whereas the amount of blood loss was greater and duration of hospital stay was longer in the open cystectomy group in their series.

In our patients, the duplicated ureters on the right side were not demonstrated on the preoperative abdominal CT; however, they were detected intraoperatively, which was a surprising finding for the console surgeon. Recently, Eisner et al18 evaluated the ability of CT in detecting ureteral duplication to determine how frequently these anomalies are underdiagnosed in 14 patients with known ureteric duplication. The sensitivity of axial CT with contrast material, axial CT without contrast material, and coronal CT without contrast material was 96%, 59%, and 65%, respectively, in their study.18 The negative predictive value of axial CT with contrast material, axial CT without contrast material, and coronal CT without contrast material was 95%, 65% and 67%, respectively.18 They demonstrated that duplicated ureters are underdiagnosed on CT and stated that urologists should be aware of this limitation.18 Similarly, right duplicated ureters were not recognized on preoperative CT in our case.

The rate of CIS in the distal ureters at the time of RC has been reported to be between 8.5% and 33%.19 Recently, Touma et al19 evaluated the reliability of frozen-section analysis of ureteral sampling during RC for bladder cancer. The sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values were 96.1%, 71.9%, 63.9% and 97.2%, respectively.19 Table 119–23 summarizes the rates of urothelial CIS of the ureteral margins excised during RC for bladder cancer evaluated during intraoperative frozen section and postoperative final pathological analysis, which suggests that ureteral frozen section has a low positive predictive value and a tendency to overestimate the tumor at the ureteral margin.19 Our case (Case 1) further supports this finding. Due to the multifocal nature of CIS, it is not possible to rule out that a negative frozen section ensures that CIS is not more proximal.19 Therefore, controversy exists concerning the ability of ureteral frozen section analysis in detecting ureteral involvement by TCC or CIS, and it might be best to rely on the final pathological evaluation of the tissues. However, risk factors for upper urinary tract recurrence including the presence of diffuse bladder CIS, multiple bladder tumors, intramural ureteral CIS, history of previous ureteral tumor, prostatic and urethral TCC involvement should be considered in the follow-up of these patients.19,20,24–26 After performing a Wallace type uretero-ureterostomy, a nephroureterectomy for upper urinary tract recurrence would be clearly a difficult surgery. However, in case such a surgery would be needed, revision and reconstruction of the remaining afferent loop and ureteric anastomoses would have been done at the same time with the removal of the unit with TCC recurrence. Since the presence of CIS does not always warrant surgical management, we preferred to complete the preplanned minimally invasive surgery. Luckily, the final pathology came back as negative for any tumor at the distal ends of the ureters that obviated the need for possible removal of the unit.

Table 1.

Rates of Urothelial CIS of the Ureteral Margins Excised at Radical Cystectomy for Bladder Cancer Evaluated During Intraoperative Frozen Section and Postoperative Final Pathological Analysis

| Author | Ref | Year | No. of patients | Ureteral Frozen section analysis (+) for CIS | Final ureteral pathologic evaluation (+) for CIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silver et al | 20 | 1997 | 401 | 6.2% | 3.7% |

| Schumacher et al | 21 | 2006 | 805 | 4.8% | 3.6% |

| Herr et al | 22 | 1987 | 105 | NR | 29% |

| Raj et al | 23 | 2006 | 1330 | 6% | NR |

| Touma et al | 19 | 2010 | 301 | 9.9%* | 6.4%* |

Includes atypia, dysplasia, or solid urothelial carcinoma in addition to CIS.

CIS=carcinoma in situ; NR=not reported (Table modified from ref. 19).

CONCLUSION

Currently, RALRC and intracorporeal Studer pouch formation is increasingly being performed successfully. In a patient with a preoperatively known ureteric duplication, one might choose open surgery rather than laparoscopy or robot-assisted laparoscopy to perform radical cystoprostatectomy with Studer pouch formation. However, as we experienced and demonstrated in our cases, duplicated ureters might be underdiagnosed on CT, and we do not think that this rare entity is a contraindication to use the robot in this complicated procedure. Because the literature lacks publications concerning the use of the surgical robot in the presence of ureteric duplication during Studer pouch formation, it is not very easy to draw a strict conclusion from our 2 cases and warrants further published reports. But, our experience which is the very first report in the English literature to the best of our knowledge, supports the idea that ureteric duplication can be successfully managed robotically at the time of RALRC, even if not diagnosed in the preoperative radiologic evaluations. However, we think that the da Vinci-S robot has many advantages and is very safe in the presence of ureter anomalies encountered when RALRC and intracorporeal Studer pouch formation are performed, enabling delicate dissection of the tissues. Frozen section analysis of ureters during RC for bladder cancer does not seem to be a reliable method and might overestimate the disease in the ureters.

References:

- 1. Braga LH, Moriya K, El-Hout Y, Farhat WA. Ureteral duplication with lower pole ureteropelvic junction obstruction: laparoscopic pyeloureterostomy as alternative to open approach in children. Urology. 2009;73:374–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huang GJ, Stein JP. Open radical cystectomy with lymphadenectomy remains the treatment of choice for invasive bladder cancer. Curr Opin Urol. 2007;17:369–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pruthi RS, Nix J, McRackan D, et al. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic intracorporeal urinary diversion. Eur Urol. 2010;57:1013–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schumacher MC, Jonsson MN, Wiklund NP. Robotic cystectomy. Scand J Surg. 2009;98(2):89–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beecken WD, Wolfram M, Engl T, et al. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical cystectomy and intra-abdominal formation of an orthotopic ileal neobladder. Eur Urol. 2003;44:337–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Balaji KC, Yohannes P, McBride CL, Oleynikov D, Hemstreet GP., 3rd Feasibility of robot-assisted totally intracorporeal laparoscopic ileal conduit urinary diversion: initial results of single institutional pilot study. Urology. 2004;63:51–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hubert J, Chammas M, Larre S, et al. Initial experience with successful totally robotic laparoscopic cystoprostatectomy and ileal conduit construction in tetraplegic patients: report of two cases. J Endourol. 2006;20:139–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Golijanin DJ, Singer EA, Marshall J, et al. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical cystectomy with intracorporeal ileal conduit urinary diversion: initial clinical experience. In: American Urological Association Annual Meeting; April 2009; Chicago IL J Urol. 2009;181:A1006 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Akbulut Z, Canda AE, Ozcan MT, Atmaca AF, Ozdemir AT, Balbay MD. Robot assisted laparoscopic radical cystoprostatectomy with intracorporeal Studer pouch formation: first 12 cases. J Endourol. 2010;24(Supplement 1):PS15–6, A114 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guru KA, Nyquist J, Perlmutter A, Peabody JO. A robotic future for bladder cancer? Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Prout GR, Marshall VF. The prognosis with untreated bladder tumors. Cancer. 1956;9:551–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Malkowicz SB, van Poppel H, Mickisch G, et al. Muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Urology. 2007;69:3–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Woods ME, Wiklund P, Castle EP. Robot-assisted radical cystectomy: recent advances and review of the literature. Curr Opin Urol. 2010;20:125–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Parra RO, Andrus CH, Jones CP. Laparoscopic cystectomy: initial report on a new treatment for the retained bladder. J Urol. 1992;148:1140–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Menon M, Hemal AK, Tewari A, et al. Nerve-sparing robot assisted radical cystoprostatectomy and urinary diversion. BJU Int. 2003;92:232–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ng CK, Kauffman EC, Lee MM, et al. A comparison of postoperative complications in open versus robotic cystectomy. Eur Urol. 2010;57:274–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coward M, Smith A, Kurpad R, et al. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical cystectomy for bladder cancer: peri-operative outcomes in 85 patients and comparison to an open cohort. J Urol. 2009;181(suppl):365 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eisner BH, Shaikh M, Uppot RN, Sahani DV, Dretler SP. Genitourinary imaging with noncontrast computerized tomography–are we missing duplex ureters? J Urol. 2008;179(4):1445–1448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Touma N, Izawa JI, Abdelhady M, Moussa M, Chin JL. Ureteral frozen sections at the time of radical cystectomy: reliability and clinical implications. Can Urol Assoc J. 2010;4(1):28–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Silver DA, Stroumbakis N, Russo P, et al. Ureteral carcinoma in situ at radical cystectomy: does the margin matter? J Urol. 1997;158:768–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schumacher MC, Scholz M, Weise EK, et al. Is there an indication for frozen section examination of the ureteral margins during cystectomy for transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. J Urol. 2006;176:2409–2413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Herr H, Whitmore WF., Jr Ureteral carcinoma in situ after successful intravesical therapy for superficial bladder tumors: incidence, possible pathogenesis and management. J Urol. 1987;138:292–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Raj GV, Tal R, Vickers A, et al. Significance of intraoperative ureteral evaluation at radical cystectomy for urothelial cancer. Cancer. 2006;107:2167–2172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johnson DE, Wishnow KI, Tenney D. Are frozen-section examinations of ureteral margins required for all patients undergoing radical cystectomy for bladder cancer? Urology. 1989;33:451–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schoenberg MP, Carter HB, Epstein JI. Ureteral frozen section analysis during cystectomy: a reassessment. J Urol. 1996;155:1218–1220 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sanderson KM, Cai J, Miranda G, et al. Upper tract urothelial recurrence following radical cystectomy for transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: an analysis of 1,069 patients with 10-year follow-up. J Urol. 2007;177:2088–2094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]