Abstract

Helper-dependent adenoviral vectors deleted of all viral coding sequences have shown an excellent gene expression profile in a variety of animal models, as well as a reduced toxicity after systemic delivery. What is still unclear is whether long-term expression and therapeutic dosages of these vectors can be obtained also in the presence of a preexisting immunity to adenovirus, a condition found in a high proportion of the adult human population. In this study we performed intramuscular delivery of helper-dependent vectors carrying mouse erythropoietin as a marker transgene. We found that low doses of helper-dependent adenoviral vectors can direct long-lasting gene expression in the muscles of fully immunocompetent mice. The best performance—i.e., 100% of treated animals showing sustained expression after 4 months—was achieved with the latest generation helper-dependent backbones, which replicate and package at high efficiency during vector propagation. Moreover, efficient and prolonged transgene expression after intramuscular injection was observed with limited vector load also in animals previously immunized against the same adenovirus serotype. These data suggest that human gene therapy by intramuscular delivery of helper-dependent adenoviral vectors is feasible.

Replication-deficient adenoviral (Ad) vectors deleted of one or more early genes (first- and second-generation Ad vectors) are among the most efficient vehicles for in vivo gene delivery, but their utilization for therapeutic purposes is limited by the transient nature of transgene expression and the systemic toxicity, which are both due to inflammatory and immune responses triggered by the residual expression of viral proteins (1–5). The development of Ad vectors deleted of all viral coding sequences offers the prospect of a safer and more efficient way to deliver genes (6). Production of fully deleted Ad vectors, also called helper-dependent (HD) Ad vectors, is possible thanks to the supply in trans of the viral proteins required for replication and packaging by a helper first-generation virus (7).

Previous studies by several laboratories have shown improved performances of HD vs. first-generation vectors after intravenous (i.v.) injection as to efficacy of transduction, longevity of transgene expression, and systemic toxicity (8–11). These studies strongly suggested that latest generation adenoviruses may be useful for human applications. However, delivery of Ad vectors (including HD vectors) to human recipients may be rendered particularly difficult when a preexisting immunity against an adenovirus serotype identical to, or cross-reactive with, the one used for gene transfer has previously developed as a consequence of a natural infection. This interfering effect is expected to be particularly pronounced in the case of i.v. delivery, because transducing vector particles will be exposed to circulating neutralizing antibodies before reaching the main target organ, the liver. It is therefore important to evaluate performance, therapeutic efficacy, and dosage of HD vectors also in alternative organs or tissues where they can be topically injected.

In recent years skeletal muscle has emerged as an important target tissue for replacement therapy for a number of reasons: (i) muscle constitutes as much as 40% of total body mass and is readily accessible; (ii) skeletal myocytes can be transduced in vivo; (iii) skeletal myofibers have a relatively long half-life, and are therefore a stable platform in which to express recombinant genes; and (iv) muscle is highly vascularized and skeletal muscle cells can efficiently secrete recombinant proteins into the systemic circulation (12, 13). These properties explain the large number of preclinical and clinical gene transfer studies to muscle with both viral and nonviral vectors (14, 15).

Although preliminary studies of this type have been previously conducted in mice also with fully HD vectors, they were not able to provide the appropriate answers because of the use of preparations heavily contaminated by helper virus particles and because of their short duration. In light of these considerations we have decided to carefully investigate the behavior of lastest generation HD vectors after intramuscular (i.m.) delivery in a variety of conditions important for future clinical applications. To this end, we studied transduction efficiency and longevity of expression after i.m. delivery of an HD vector expressing mouse erythropoietin (mEPO).

Materials and Methods

Animals.

BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Italy (Lecco, Italy). Unless noted otherwise, all mice were 8–9 weeks old at the time of injection. Injections were performed in the quadriceps muscle of the left hind limb in a 50-μl volume or in the tail vein in a 100-μl volume, using 28G1/2 needles.

Ad Vectors Ad-mEPO, HD-mEPO, and C4AFO-mEPO.

Construction and preparation of Ad vectors Ad-mEPO, HD-mEPO, and C4AFO-mEPO has been described (11, 16). Infectious titers were determined by infection of HeLa cells in parallel with Ad-mEPO as described (11, 16). Comparison of the amount of mEPO secreted in the culture supernatant allowed the estimation of the infectious titers of HD-mEPO vectors based on the plaque-forming unit titer of Ad-mEPO. Vectors were diluted in PBS for injection.

Blood Measurements.

Blood was obtained by retroorbital puncture. Hematocrits (Hcts) and mEPO levels were determined as described (11, 17).

Histological Analysis.

Mice were euthanized at the indicated time points after i.m. injection of the HD vector. Quadriceps muscles were surgically removed, immediately fixed for at least 16 h in 4% formaldehyde buffered at pH 7.2, and embedded in paraffin. About 5-μm serial sections were cut from paraffin blocks, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE), and examined under a light microscope.

RNAase-Protection Analysis (RPA).

Quadriceps muscles were surgically removed and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was extracted by homogenizing the tissues in Ultraspec-II RNA isolation system (Biotecx Laboratories, Houston) with a Polytron homogenizer (Kinematica, Lucerne, Switzerland); RPAs were performed with the mCD-1 and mCK-3b probe sets of the RiboQuant MultiProbe RNase Protection Assay System (PharMingen, San Diego), following the instructions furnished by the manufacturer.

Vector Genome Quantification.

Mice were euthanized at the indicated times after i.m. injection of the Ad vector. Necropsies were performed aseptically with a separate set of sterile instruments for each animal to avoid cross-contamination. The removed tissues were frozen in liquid nitrogen, and DNA was isolated by using proteinase K and extractions with phenol/chloroform. After precipitation with ethanol, DNA samples were diluted to ≈100 μg/ml. TaqMan real-time PCR (Perkin–Elmer) was used to measure the amount of HD genomes relative to the amount of mouse muscle DNA.

Neutralizing Antibody Assay.

Neutralizing antibody titers were determined as previously described (11).

Statistical Analysis.

A one-way ANOVA was used for statistical analysis of significance.

Results

Superior Performance of HD Vector vs. First-Generation Vector After i.m. Delivery.

We have previously shown that i.v. injection of small amounts of HD-mEPO, an HD Ad vector carrying the mEPO cDNA under the control of the elongation factor 1α (EF-1α) gene promoter in the STK120 backbone, gave rise to both stable mEPO production and Hct elevation that persisted for over 1.5 years in immunocompetent mice, whereas i.v. injection of Ad-mEPO, a first-generation Ad vector carrying the same expression cassette, induced only transient mEPO production and Hct elevation (11).

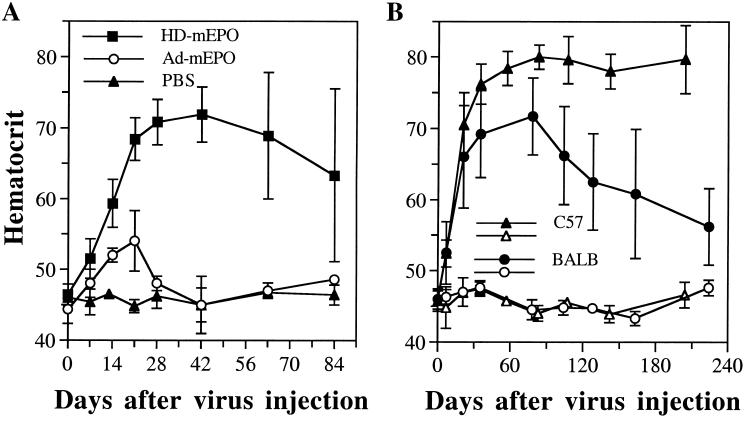

To determine whether the two vectors show different behavior also after i.m. administration, 3 × 106 infectious units (i.u.) of the two viruses were injected into the quadriceps of BALB/c mice. As expected, in mice injected i.m. with Ad-mEPO, Hct increased only slightly (maximum 54%), peaked at day 21 postinjection (p.i.), and rapidly returned to baseline at day 42. In contrast, BALB/c mice injected with the same number of i.u. of HD-mEPO displayed strongly increased Hct (maximum 70–72%), significantly different from that of both Ad-mEPO (P < 0.0001) and PBS-injected (P < 0.0001) mice, and this increase stayed high at day 84 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

(A) In vivo comparison between HD-mEPO and Ad-mEPO: 3 × 106 i.u. of the two viruses were injected side-by-side in the quadriceps muscle of BALB/c mice (n = 6). (B) Longevity of Hct increase induced by HD-mEPO in various mouse strains. Groups of C57BL/6 (C57; n = 5), and BALB/c (BALB; n = 4) mice were injected in parallel in the quadriceps muscle with 3 × 106 i.u. of HD-mEPO virus (filled symbols) or with PBS (empty symbols). Hcts and standard deviations are shown.

However, contrary to what observed after i.v. injection of the same HD-mEPO preparation (ref. 11 and data not shown), mice injected i.m. began showing great variability starting 63 days p.i. (Fig. 1A). In the same injection group some animals (Table 1, nos. 1, 2, 3, and 6) had a sudden drop of circulating mEPO between day 28 and day 63 p.i., followed by a decrease of the Hct, whereas others (nos. 4 and 5) maintained mEPO expression well above preinjection levels and elevated Hct for 1 year (64% and 70% at day 365 p.i., respectively). This phenomenon is highly reproducible, as it was observed in four different injection experiments for a total of 21 mice (see below).

Table 1.

Hct and mEPO levels in individual mice at various time points after HD-mEPO i.m. injection

| Mouse no. | Measurement | Days after vector

injection

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 14 | 21 | 28 | 42 | 63 | 84 | ||

| 1 | Hct, % | 45.5 | 63.5 | 70 | 74 | 77 | 72 | 60 |

| mEPO, mU/ml | 8.2 | 38 | 73 | 60 | 25 | 0.3 | 0 | |

| 2 | Hct, % | 43.5 | 61 | 71 | 73 | 68.5 | 66.5 | 62.5 |

| mEPO, mU/ml | 14 | 47 | 50 | 9.7 | 2.7 | 4.2 | 0.4 | |

| 3 | Hct, % | 44 | 57 | 67.5 | 69.5 | 66.5 | 54 | 46.5 |

| mEPO, mU/ml | 10 | 35 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | |

| 4 | Hct, % | 46 | 58.5 | 68.5 | 69 | 74.5 | 80 | 77.5 |

| mEPO, mU/ml | 10 | 81 | 103 | 51 | 69 | 38 | 35 | |

| 5 | Hct, % | 46.5 | 53.5 | 63 | 66 | 73 | 74.5 | 77 |

| mEPO, mU/ml | 8.7 | 27 | 36 | 24 | 24.6 | 19.5 | 28 | |

| 6 | Hct, % | 45 | 62 | 70.5 | 73.5 | 72 | 66.5 | 55.5 |

| mEPO, mU/ml | 10 | 77 | 138 | 81.5 | 0.9 | 0 | 0 | |

When the same HD-mEPO preparation was injected i.m. into C57BL/6 mice, which are known to have a less vigorous response to Ad vectors (18, 19), Hct remained uniformly elevated for the entire duration of the experiment in five of five injected C57BL/6 mice (Fig. 1B). Moreover, as late as 204 days after injection, mEPO levels were significantly higher in the five virus-injected mice as compared with the PBS-injected mice [63.4 ± 24.9 milliunits (mU)/ml vs. 21.6 ± 15.2 mU/ml, respectively; P = 0.0126]. Therefore, no C57BL/6 mouse lost transgene expression for at least 29 weeks after vector administration.

In conclusion, these data, while confirming HD as an improved vector compared with first-generation adenovirus also for i.m. delivery, they further indirectly suggest that local delivery of these vectors may induce host immune responses that limit duration of transgene expression.

Loss of Gene Expression in a Subset of Mice Injected i.m. with HD Vector Is Caused by Inflammatory and Immune Responses.

To gain insight into this phenomenon, BALB/c mice were injected i.m. with 3 × 106 i.u. of HD-mEPO and euthanized at various times p.i., and muscles were used to perform histological analysis and RPAs. In addition, mEPO levels were monitored both before injection and weekly until euthanization.

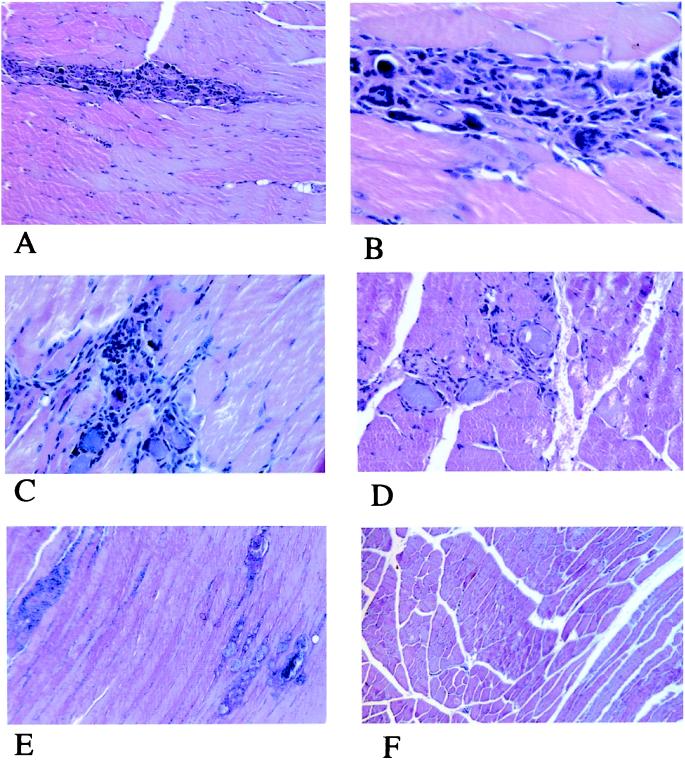

Histological examination showed progressive time-related lesion of single myocytes or small groups of them (Fig. 2). At 7 days the dominant feature was the presence of foci of infiltrated mononucleated cells (Fig. 2A) associated with a basophilic appearance of muscle cells often lacking nuclei (Fig. 2B); at this magnification the inflammatory cells are clearly morphologically detectable as macrophages and lymphocytes. At 14 days the lesions were multifocal, with an increased number of damaged myocytes; lymphocytes were the prevalent inflammatory cells (Fig. 2C). The same picture was observed at 21 days, together with more evident regressive changes of the muscle cells involved, often calcified (Fig. 2D). At 28 days the inflammatory process was turned off and multifocal fibrosis and myocyte calcification were the only changes observed (Fig. 2E). None of the described features were observed, at any time, in the contralateral muscle (Fig. 2F) used as control.

Figure 2.

Histology. (A) Quadriceps muscle 7 days after injection. Mononucleated cell infiltration is evident in a needle-shaped pattern. (HE; original magnification ×4.) (B) Quadriceps muscle 7 days after injection. The muscle cells involved in the lesion appear more basophilic than those not involved and often lack nuclei. (HE; original magnification ×25.) (C) Quadriceps muscle 14 days after injection. The inflammatory infiltration is more extensive and lymphocytes are collected around the suffering myofibers. (HE; original magnification ×10.) (D) Quadriceps muscle 21 days after injection. The inflammatory cells are scarce while the basophilic appearance of the nuclei lacking myofibers is more pronounced. (HE; original magnification ×10.) (E) Quadriceps muscle 28 days after injection. No inflammatory infiltration is present and only foci of calcified muscle cells (left) and fibrosis (right) are evident. (HE; original magnification ×4.) (F) Uninjected quadriceps muscle 14 days after injection in the contralateral muscle. No lesions are detectable. (HE; original magnification ×4.)

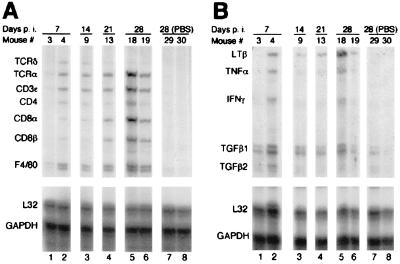

We next analyzed the extracted RNA by RPA with a set of probes specific for mouse T cell and macrophage surface antigens. In agreement with the histological findings, the appearance of a CD3ɛ-protected fragment 7 days p.i. confirmed the presence of infiltrating T cells, the majority of which were T cell receptor (TCR)α-bearing T cells (Fig. 3A, lane 2). Cytotoxic and helper T cells were both present, judging by the comparable intensities of the bands protected by the CD4 and CD8 RNA probes (Fig. 3A, lane 2). Macrophages were also present, as the F4/80 probe (a murine macrophage-restricted cell surface glycoprotein; ref. 20) was also protected (Fig. 3A, lane 2). Interestingly, 21 and 28 days p.i. the majority of infiltrating lymphocytes expressed the CD8 coreceptor (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 and 5). At these times the intensity of the CD8α-protected probe was equal to or higher than that of the F4/80-protected probe (Fig. 3A, lanes 4 and 5).

Figure 3.

RPA was performed on RNA extracted from muscles of mice euthanized at the indicated times. RPA used the mCD-1 (A) or the mCK-3b (B) probe. The identities of the RNA-protected probes are indicated. L32 ribosomal protein (L32) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) RNAs are shown as controls.

Signals for lymphotoxin β (LTβ), tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), transforming growth factors β1 (TGFβ1) and β2 (TGFβ2) were also observed in the same RNA samples (Fig. 3B, lanes 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6). In particular, there was a good correlation between the intensity of the TCRα, CD3ɛ, CD8α, and CD8β bands (which can all derive from CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes) and that of LTβ (Fig. 3). No signal was detected in RNA from PBS-injected muscles (Fig. 3, lanes 7 and 8) or from contralateral muscles of vector-injected mice (data not shown).

Interestingly, the pattern of fragments protected by the mRNAs of infiltrating cells was present in roughly 50% of injected mice (Fig. 3, lanes 1 and 2; data not shown), in agreement with the percentage of mice that lost transgene expression (Table 1; see below). It is also worthy of notice that mice with more abundant lymphocytic infiltrate experienced a sudden drop in the circulating mEPO levels at the time of euthanization (mouse no. 18: 24 mU/ml 14 days p.i; 1.4 mU/ml 28 days p.i.), whereas mice that showed lower inflammatory infiltrate maintained EPO expression (mouse no. 19: 24 mU/ml 14 days p.i.; 32 mU/ml 28 days p.i.). Therefore, persistence of transgene expression correlated inversely with the degree of immune and inflammatory response.

Finally, we assessed whether the immune response affects the stability of vector genomes. For this purpose, DNA was extracted from the muscles of BALB/c mice injected i.m. with 3 × 106 i.u. of HD-mEPO and which showed over time a divergent pattern of gene expression (Table 2). Group 1 (mice 27/2, 26, and 27) maintained increased serum mEPO levels at day 105 and elevated Hct at day 257, whereas group 2 (mice 28, 29, and 30) lost EPO expression and experienced return to baseline Hct at the same time points. A third group of animals (group 3) was used as control to monitor DNA uptake 24 h after injection. Persistence of vector DNA was assessed by a quantitative PCR (Q-PCR), which detected 1 copy of vector genome per 105 nuclei (see Materials and Methods). Interestingly, in mice that did not loose transgene expression (group 1), there was no significant difference between the vector genomes detected 24 h p.i. and 257 days p.i. (compare groups 1 and 3 in Table 2; P = 0.124). In contrast, in mice that lost transgene expression (group 2) the number of vector genomes detected was significantly lower (P = 0.027). After i.m. administration of 3 × 106 i.u. of HD-mEPO, no vector genome was found in the liver of injected mice (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hct, mEPO levels, and number of vector genomes in individual mice at various times after HD-mEPO i.m. injection

| Group | Mouse no. | mEPO, mU/ml

|

Hct, %, day 257 | Day of euthanization | Vector

genomes

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 14 | Day 105 | Injected muscle | Liver | ||||

| 1 | 27/2 | 83 | 42 | 69 | 257 | 2,057 | 0 |

| 26 | 22 | 21 | 72.5 | 257 | 4,697 | ND | |

| 27 | 29 | 36 | 69 | 257 | 1,391 | 0 | |

| Mean | 45 ± 33 | 33 ± 10 | 70 ± 2 | 2,715 ± 1,748 | |||

| 2 | 28 | 22 | 4.8 | 45 | 257 | 404 | ND |

| 29 | 58 | 3.3 | 46 | 257 | 208 | 0 | |

| 30 | 40 | 0.2 | 49 | 257 | 173 | 0 | |

| Mean | 40 ± 18 | 2.8 ± 2.3 | 46 ± 2 | 262 ± 124 | |||

| 3 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 1,396 | ND |

| 2 | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 807 | ND | |

| 3 | NA | NA | NA | 1 | 1,418 | ND | |

| Mean | 1,207 ± 346 | ||||||

NA, not applicable; ND, not determined.

The above data show that an inflammatory and immune response is associated with clearance of HD-mEPO vector DNA in a subset of BALB/c mice with consequent loss of gene expression.

An Improved HD-Ad Backbone Allows Increased Persistence of Gene Expression After i.m. Delivery.

The immune response observed after i.m. injection of HD-mEPO does not seem to be an inherent property of the HD vector for three reasons: it is not observed in all i.m. injected BALB/c mice, it is not observed in i.m. injected C57BL/6 mice, and it is not observed at all in i.v. injected animals (11).

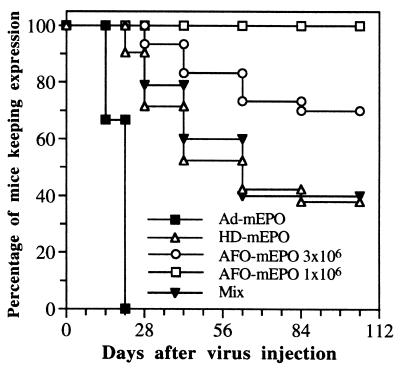

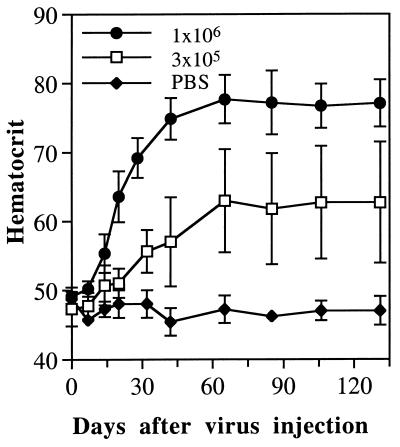

We recently generated C4AFO-mEPO, an HD vector with a modified backbone and the same mEPO expression cassette (16). Vector C4AFO-mEPO was delivered i.m. at the dose of 3 × 106 i.u. and its biological effect compared with that obtained with the other vectors, all injected into BALB/c mice at the same dose. A striking difference emerged from the analysis of long-term EPO expression data in a large number of animals (summarized in Fig. 4). All mice injected with Ad-mEPO (n = 12) lost transgene expression by day 21, and 60% of mice injected with HD-mEPO (n = 21) lost transgene expression by day 63. To our surprise, only 30% of C4AFO-mEPO injected mice (n = 30) lost transgene expression, and with kinetics slower than the other two groups (Fig. 4). However, when 3 × 106 i.u. doses of the two vectors were mixed and injected, the percentage of mice loosing transgene expression was identical to that in the group of mice injected with HD-mEPO only (Fig. 4). More interestingly, when BALB/c mice were injected i.m. with only 1 × 106 i.u. (n = 13) or 3 × 105 i.u. (n = 13) of C4AFO-mEPO, no mouse lost mEPO expression (Fig. 4 and data not shown) and, as a consequence, all mice maintained constantly elevated Hcts for the duration of the experiment (Fig. 5). Moreover, as in the case of i.v. delivery (11), 3 × 105 i.u. was the lowest dose able to induce significant and prolonged Hct elevation also after i.m. delivery.

Figure 4.

Percent of mice maintaining transgene expression after Ad vector i.m. injection. A mouse was considered to have lost transgene expression at a given time if mEPO levels dropped at least 5-fold compared with the previous time point and if the Hct dropped at least 10 percentage points in the following 2 months (see as example Table 1).

Figure 5.

Longevity of Hct increase induced by low doses of C4AFO-mEPO vector. Groups of healthy adult female BALB/c (n = 7) mice were injected in the quadriceps muscle with the indicated doses of C4AFO-mEPO Ad vector. Hcts and standard deviations are shown.

Intramuscular Injection of C4AFO-mEPO Ad Vector Overcomes Preexisting Immunity to Adenovirus.

In the previous section we showed that an improved HD vector gives rise to persistent gene expression after i.m. delivery. The HD vectors are currently packaged by using an adenovirus type 5 helper virus and are, therefore, coated by serotype 5 capsid proteins. A major concern for the future clinical application of Ad vectors is the possibility that preexisting immunity to an adenovirus of the same or cross-reactive serotype may strongly limit vector efficacy. This holds particularly true for adenovirus type 5, because of a high seroprevalence in the adult human population (21, 22). We therefore determined how a preexisting anti-adenovirus type 5 immunity can affect i.m. delivery of C4AFO-mEPO.

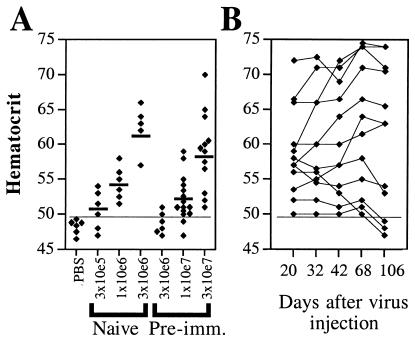

For this purpose, 36 BALB/c mice were immunized by i.v. injection of 1 × 1010 physical particles (p.p.) of H14, a first-generation Ad vector derived from adenovirus type 5 (16). Anti-adenovirus neutralizing titers were determined 35 days after injection: 33 of 36 mice had neutralizing titers ranging from 1:130 to 1:1200 and were divided into three groups with average neutralizing titer of ≈1:500, which were challenged by i.m. injection of 3 × 106, 1 × 107, or 3 × 107 i.u. of C4AFO-mEPO. Age-matched naïve mice (n = 5 or n = 6 each) were injected i.m. with 3 × 105, 1 × 106, or 3 × 106 i.u. of C4AFO-mEPO, respectively. The Hcts were measured at day 14 and the results are shown in Fig. 6A. The dose–response observed showed that at the highest dose, 3 × 107 i.u., all preimmunized animals responded and the average Hct increase of the group (59.1%) was higher than that of age-matched naïve mice injected with a 30-lower amount of vector (54.2%); mEPO levels were comparable between the two groups (14 ± 9 mU/ml in the preimmunized injected with 3 × 107 i.u. vs. 15 ± 3.4 mU/ml in the naïve injected with 1 × 106 i.u.). The Hct of the mice challenged with the 3 × 107 i.u. C4AFO-mEPO dose was followed over time. Surprisingly, Hct remained stable or even increased until day 68 p.i. (Fig. 6B). Even at day 106 p.i. (last time point tested), 9 of 12 mice still maintained transgene expression, in agreement with what happens in naïve mice (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

Gene transduction by C4AFO-mEPO injection in preimmunized mice. (A) Hcts 14 days after C4AFO-mEPO injection. The short thick lines indicate the average Hct of mice challenged i.m. with C4AFO-mEPO. The doses injected are shown. (B) Longevity of Hct increase in individual preimmunized mice challenged with 3 × 107 i.u. of C4AFO-mEPO. The days p.i. are shown. The thin horizontal line in both panels indicates the level above which the Hct is significantly different from the average Hct of age-matched PBS-injected mice.

Discussion

HD vectors give rise to sustained liver gene expression after i.v. delivery in both naïve small laboratory animals (8, 9, 11, 16) and nonhuman primates (10). This important property, together with the observation that their systemic inoculation does not cause significant liver damage and toxicity (8, 9, 23, 24), makes HD vectors the best available Ad vectors for somatic gene transfer, opening up possibilities for their future clinical use. However, systemic inoculation of Ad vectors in a clinical setting might be rendered inefficient by the presence of circulating neutralizing antibodies to the same or cross-reactive serotype as a consequence of a natural infection. Up to 50% of human subjects have a detectable immune response to adenovirus type 5 (21, 22); thus the capacity to overcome a preexisting immunity is a fundamental problem. Indeed, we observed that when BALB/c mice, preimmunized with a first generation adenovirus type 5 vector and showing an average neutralizing antibody titer of 1:500, were injected i.v. with 3 × 108 i.u. of the C4AFO-mEPO vector (D.M. and R.S., unpublished work), 60% (6 of 10 mice) did not show a Hct increase and the remaining 40% showed EPO expression levels comparable to those obtained in naïve mice injected with 1000-fold less virus (11). This observation, together with the reasoning that local administration may require smaller dosages of viral vectors, with a further limitation of inflammatory and toxic effects, prompted us to evaluate skeletal muscle as an alternative tissue for HD vector delivery.

In this paper we present strong evidence that when injected i.m. into naïve mice, HD vectors give rise to prolonged gene expression for several months, whereas the same number of infectious particles of a first-generation vector carrying the same expression cassette is less efficient and its biological effect is of much shorter duration. Therefore, the HD vector proved to be superior to first-generation vectors also in the case of i.m. delivery. Our finding is important because long-term gene expression in muscle with a fully deleted Ad vector administered to adult immunocompetent mice had not been reported previously. In fact, previous studies were either short term (25) or carried out in newborn animals (26, 27), which are known to have an immature immune system. An in-depth demonstration that this type of vector had useful properties for stable gene transfer to muscle was therefore missing.

Our results, however, indicate that long-term gene expression in muscle is difficult to achieve even with an HD vector. Indeed, in a subset of injected mice we have observed local inflammation (see the presence of inflammatory cells and macrophage cell markers at day 7 p.i.) followed by a cytotoxic immune response (suggested by the presence of a CD8+ cell infiltrate, with the highest intensity at day 28), which terminate in the lysis of transduced cells and loss of vector DNA; it should be noted that the preparation was found to be sterile and endotoxin-free (data not shown). Instead, we never observed liver inflammation after i.v. delivery of HD-mEPO at all injected doses (ref. 11 and D.M., C.D.R., and R.S., unpublished data). Interestingly, when we used a more advanced HD backbone, which had been selected to have improved replication and gives rise to higher-titer preparations less contaminated by helper virus (16), the percentage of mice loosing transgene expression decreased (Fig. 4). It is unlikely that the cause of the observed immune response is the first-generation helper adenovirus, which is known to contaminate HD preparations at the level of 0.1–1%, because we performed reconstitution experiments in which a fixed dose of 3 × 106 i.u. of C4AFO-mEPO was injected with increasing amounts of H14 helper virus, and we noticed that artificially increasing the helper virus contamination up to 10% did not increase the percentage of mice that lost transgene expression (D.M., P.G., and R.S., unpublished data). Although the expression cassette contained in the vector is driven by a ubiquitous promoter, which can drive mEPO expression in non-muscle cells (such as dendritic cells), the immune response is not directed against mEPO, as the animals do not become anemic, as has been observed after the development of an autoimmune response (11). An alternative possibility is that small amounts of impurities present in the vector preparations remain at the site of injection and induce the observed local inflammation. The transduced fibers may then be subjected to attack and lysis by CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes, as they may directly present the incoming viral proteins as antigens, as has been proposed in one study (28). By contrast, after i.v. delivery of the same vector in the caudal vein, the same impurities may be filtered out by the lung capillaries or diluted in the circulation (29), and consequently do not colocalize with the HD vector into hepatocytes. It can be speculated that the C4AFO HD backbone, which replicates more efficiently (16), gives rise to higher-titer preparations less contaminated by cellular debris. This speculation fits with the observations that C4AFO-mEPO consistently shows a better performance after i.m. delivery and that when the two vectors are mixed the percentage of mice losing transgene expression is identical to that in the group of mice injected with HD-mEPO alone (Fig. 4). In particular, the latest observation argues against the hypothesis that the inflammatory or immune response of individual mice may be determined solely by stochastic factors, but rather suggests that something in the HD-mEPO preparation increases the likelihood that individual mice mount an immune response. The nature and identity of the putative contaminant may be investigated by means of HPLC and SDS/PAGE (30).

The minimal effective i.m. dose of C4AFO-mEPO in naïve animals is 3 × 105 i.u. and had to be increased only 30- to 100-fold in mice preimmunized with the same serotype to achieve 87% or 100% gene expression, respectively, and stable Hct elevation. Therefore, HD vector delivery i.m., but not i.v., can completely bypass a preexisting humoral immunity. Although a recent study also reported effective injection of a first-generation Ad vector encoding β-galactosidase only to the muscle and not to the liver (31), this study addressed only short-term expression 24 h p.i., because of the transient nature of first-generation Ad vectors. Indeed, Svensson et al. (32) previously showed that, after i.m. injection of 108 i.u. of an E1/E3-deleted Ad vector carrying mEPO, a second administration of the same virus was unable to further increase Hct, even when performed as late as 9 months after the first injection. In conclusion, the observed prolonged gene expression after i.m. HD vector delivery in preimmunized animals is a further demonstration of the superior properties of these vectors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Manuela Emili for artwork and David Ngai and Edward Brown for performing sterility and endotoxin tests. We are grateful to Janet Clench, Fabio Palombo, Carlo Toniatti, Alfredo Nicosia, and Paolo Monaci for critically reading this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- Ad

adenoviral

- HD

helper-dependent

- mEPO

mouse erythropoietin

- Hct

hematocrit

- i.u.

infectious units

- HE

hematoxylin and eosin

- mU

milliunits

- RPA

RNase-protection analysis

- p.i.

post injection

- TCR

T cell receptor

References

- 1.Yang Y, Nunes F A, Berencsi K, Furth E E, Gonczol E, Wilson J M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4407–4411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Y, Wilson J M. J Immunol. 1995;155:2564–2570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lochmuller H, Petrof B J, Pari G, Larochelle N, Dodelet V, Wang Q, Allen C, Prescott S, Massie B, Nalbantoglu J, et al. Gene Ther. 1996;3:706–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kajiwara K, Byrnes A P, Charlton H M, Wood M J, Wood K J. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:253–265. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.3-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan J M, Armentano D, Sparer T E, Wynn S G, Peterson P A, Wadsworth S C, Couture K K, Pennington S E, St. George J A, Gooding L R, Smith A E. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:45–56. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.1-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morsy M A, Caskey C T. Mol Med Today. 1999;5:18–24. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(98)01376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parks R J, Chen L, Anton M, Sankar U, Rudnicki M A, Graham F L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13565–13570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morsy M A, Gu M, Motzel S, Zhao J, Lin J, Su Q, Allen H, Franlin L, Parks R J, Graham F L, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7866–7871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.7866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiedner G, Morral N, Parks R J, Wu Y, Koopmans S C, Langston C, Graham F L, Beaudet A L, Kochanek S. Nat Genet. 1998;18:180–183. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morral N, O'Neal W, Rice K, Leland M, Kaplan J, Piedra P A, Zhou H, Parks R J, Velji R, Aguilar-Cordova E, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:12816–12821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maione D, Wiznerowicz M, Delmastro P, Cortese R, Ciliberto G, La Monica N, Savino R. Hum Gene Ther. 2000;11:859–868. doi: 10.1089/10430340050015473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Svensson E C, Tripathy S K, Leiden J M. Mol Med Today. 1996;2:166–172. doi: 10.1016/1357-4310(96)88792-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall D J, Leiden J M. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;8:360–365. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80094-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kay M A, Manno C S, Ragni M V, Larson P J, Couto L B, McClelland A, Glader B, Chew A J, Tai S J, Herzog R W, et al. Nat Genet. 2000;24:257–261. doi: 10.1038/73464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Losordo D W, Vale P R, Isner J M. Am Heart J. 1999;138:132–141. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70333-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandig V, Youil R, Bett A J, Franlin L L, Oshima M, Maione D, Wang F, Metzker M L, Savino R, Caskey C T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1002–1007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rinaudo D, Toniatti C. BioTechniques. 2000;29:218–220. doi: 10.2144/00292bm03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barr D, Tubb J, Ferguson D, Scaria A, Lieber A, Wilson C, Perkins J, Kay M A. Gene Ther. 1995;2:151–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schowalter D B, Himeda C L, Winther B L, Wilson C B, Kay M A. J Virol. 1999;73:4755–4766. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.6.4755-4766.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKnight A J, Macfarlane A J, Dri P, Turley L, Willis A C, Gordon S. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:486–489. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piedra P A, Poveda G A, Ramsey B, McCoy K, Hiatt P W. Pediatrics. 1998;101:1013–1019. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.6.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Molnar-Kimber K L, Sterman D H, Chang M, Kang E H, ElBash M, Lanuti M, Elshami A, Gelfand K, Wilson J M, Kaiser L R, Albelda S M. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:2121–2133. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.14-2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morral N, Parks R J, Zhou H, Langston C, Schiedner G, Quinones J, Graham F L, Kochanek S, Beaudet A L. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:2709–2716. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.18-2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aurisicchio L, Delmastro P, Salucci V, Paz O G, Rovere P, Ciliberto G, La Monica N, Palombo F. J Virol. 2000;74:4816–4823. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.10.4816-4823.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clemens P R, Kochanek S, Sunada Y, Chan S, Chen H H, Campbell K P, Caskey C T. Gene Ther. 1996;3:965–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen H H, Mack L M, Kelly R, Ontell M, Kochanek S, Clemens P R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1645–1650. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen H H, Mack, Choi S Y, Ontell M, Kochanek S, Clemens P. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:365–373. doi: 10.1089/10430349950018814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kafri T, Morgan D, Krahl T, Sarvetnick N, Sherman L, Verma I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11377–11382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cook M J. In: The Mouse in Biomedical Research. Foster H L, Small J D, Fox J G, editors. Vol. 3. Boston: Academic; 1983. pp. 102–136. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lehmberg E, Traina J A, Chakel J A, Chang R-J, Parkman M, McCaman M T, Murakami P K, Lahidji V, Nelson J W, Hancock W S, et al. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 1999;732:411–423. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(99)00316-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen P, Kovesdi I, Bruder J T. Gene Ther. 2000;7:587–595. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Svensson E C, Black H B, Dugger D L, Tripathy S K, Goldwasser E, Hao Z, Chu L, Leiden J M. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:1797–1806. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.15-1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]