Abstract

The accumulation of mutations causes cell lethality and can lead to carcinogenesis. An important class of mutations, which are associated with mutational hotspots in many organisms, are those that arise by nascent strand misalignment and template-switching at the site of short repetitive sequences in DNA. Mutagens that strongly and specifically affect this class, which is mechanistically distinct from other mutations that arise from polymerase errors or by DNA template damage, are unknown. Using Escherichia coli and assays for specific mutational events, this study defines such a mutagen, 3′-azidothymidine [zidovudine (AZT)], used widely in the treatment and prevention of HIV/AIDS. At sublethal doses, AZT has no significant effect on frame shifts and most base-substitution mutations. AT-to-CG transversions and deletions at microhomologies were enhanced modestly by AZT. AZT strongly stimulated the “template-switch” class of mutations that arise in imperfect inverted repeat sequences by DNA-strand misalignments during replication, presumably through its action as a chain terminator during DNA replication. Chain-terminating 2′-3′-didehydro 3′-deoxythymidine [stavudine (D4T)] and 2′-3′-dideoxyinosine [didanosine (ddI)] likewise stimulated template-switch mutagenesis. These agents define a specific class of mutagen that promotes template-switching and acts by stalling replication rather than by direct nucleotide base damage.

Keywords: genotoxicity, replication inhibitor, quasipalindrome, repeated sequence, DNA damage

The agent 3′-azidothymidine [zidovudine (AZT)] is a frontline drug in the treatment of HIV/AIDS. Its therapeutic effects arise by its incorporation during HIV reverse transcription, resulting in chain termination. Azidothymidine is genotoxic, particularly to mitochondria, presumably because mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma readily incorporates AZT during DNA synthesis (reviewed in Ref. 1). However, AZT also induces formation of micronuclei, sister chromatid exchange events, and various chromosomal aberrations, suggesting it may also be incorporated into nuclear DNA at some level (2). Using the bacterium Escherichia coli as a model, we have shown that AZT blocks DNA replication and causes formation of single-strand DNA gaps and double-strand breaks (3). E. coli cells appear to tolerate a certain level of AZT by the combined action of the DNA damage response, homologous recombination, and exonuclease excision. The chain-terminating azidothymidine monophosphate does not appear to be removed by intrinsic DNA polymerase proofreading; rather, the exogenous 3′ to 5′ dsDNA exonuclease, exonuclease III (an ortholog of human APE1), is likely the enzyme that removes the residue from DNA during sublethal exposure, because ExoIII− (xthA) mutants are highly sensitive to the drug and have an enhanced DNA damage response (3). A 75 ng/mL dose of AZT reduces viability of xthA mutants about 10,000-fold; because this dose has negligible effects on wild-type cells, many AZT-monophosphate lesions can be removed by ExoIII to sustain replication and proliferative capacity.

In this study we investigate the mutagenicity of AZT, at chronic, sublethal doses ∼100-fold lower than that used in therapy, using lacZ reporter strains specific to particular classes of mutations. At this dose, we expect AZT to be incorporated into DNA and subsequently excised by Exonuclease III; bacterial cells at this exposure proliferate, albeit more slowly, to form colonies. The mutations assayed include all base substitutions, frameshift mutations in nucleotide runs, deletions at microhomology and quasipalindrome-associated template-switch mutations (4). We assayed 12 or more strains and calculated mutation rates by the fluctuation methods described previously (4). Increases in mutation rate may be caused by two factors: increased likelihood of mutation incidence or decreased probability of its correction. To remove the latter contribution, we assayed AZT effects where appropriate with mutational reporters in a mutS mutant genetic background; this disables mismatch repair, which efficiently corrects frame shifts and most base substitutions. AZT, as well as other replication blocking agents (5), induces the “SOS response” to DNA damage in E. coli through the production of ssDNA gaps (4), including expression of error-prone, translesion polymerases (as reviewed in Ref. 6). Contribution by the SOS response to AZT mutational effects was ascertained with an allele of the LexA repressor protein, lexA3, that blocks SOS induction.

We suspected that AZT would have particularly strong effects on classes of mutation that arise, not by simple polymerase errors, but from gross nascent strand misalignments during replication. These have been called “template-switch” mutations because strand misalignment at short repetitive sequences can provoke DNA polymerization on an incorrect template (Fig. 1). Template-switching has been implicated in genomic rearrangements at microhomologies (including “copy number variation” or “structural variation”) in both bacteria (7) and humans (8, 9). These include the expansion of triplet repeats underlying hereditary neurological diseases in humans (10). Because blocks to replication may trigger DNA polymerase dissociation and subsequent strand unpairing and misalignment, we expected template-switching to be stimulated by AZT chain-termination.

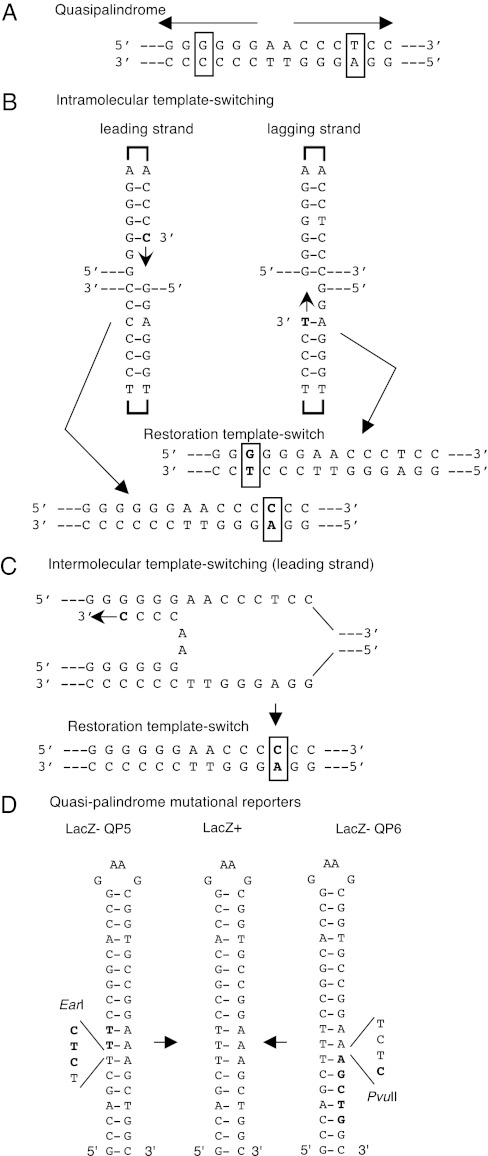

Fig. 1.

Quasipalindrome-associated template-switch mutations. (A) Example of a quasipalindrome with imperfect inverted symmetry; boxed residues are unpaired and targets for mutagenesis. (B) An intramolecular template-switch in a hairpin structure. Leading and lagging strand synthesis target different residues for mutation. A second “restoration” template-switch resumes replication, producing a premutational mispair. (C) An intermolecular template-switch across the replication fork. (D) Mutational reporters in lacZ, QP5 and QP6, detect template-switch generated Lac+ revertants on the leading and lagging strand, respectively.

Results

One class of mutational hotspots involves misalignment at imperfect inverted repeats (“quasipalindromes”); examples of quasipalindrome-associated mutations derive from bacteriophage, bacteria, yeast, and mammals (11–16). Experimental evidence supports the notion that template-switching during replication allows one arm of the inverted repeat to template mutations in the other arm (15, 17) (Fig. 1 A–C), confirming a mechanism first proposed by Ripley (13). Nascent strand misalignments may occur in the context of a hairpin structure formed between the repeats or by mispairing between the repeats across the replication fork (Fig. 1 B and C). We recently devised lacZ mutational reporters that specifically revert to Lac+ by template-switching associated with leading or lagging strand replication (Fig. 1D). Mutations detected in these assays are not subject to avoidance by mismatch repair (4).

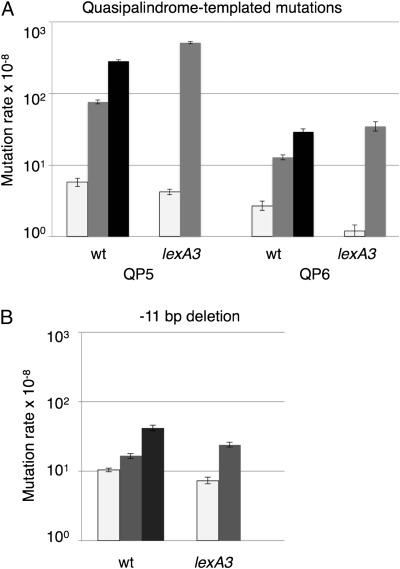

AZT had an extraordinarily strong effect on this class of mutation (Fig. 2), with a 50-fold stimulation of events templated on the leading strand (QP5 reporter) and an 11-fold elevation of lagging strand mutations (QP6 reporter) during chronic exposure to 10 ng/mL AZT; a lower dose of AZT (3 ng/mL) enhanced mutagenesis at the QP5 and QP6 reporters 13-fold and fivefold, respectively. Inactivation of the SOS response by a lexA3 allele exacerbated the mutagenic effect of AZT at the lower dose, causing an increase in mutagenesis of 120-fold at QP5 and 29-fold at QP6 relative to no treatment. This suggests that the DNA damage response plays an antimutagenic role in the tolerance of AZT and that the SOS-induced DNA polymerases are not responsible for the observed mutagenic effects of AZT.

Fig. 2.

Stimulation of templated mutations by AZT. Mutation rates without (white bars) and with 3 ng/mL (gray) or 10 ng/mL (black) AZT. Mutational events include a templated 4-bp frameshift on the leading strand (QP5) and lagging strand (QP6) (A) or a 11-bp microhomology deletion assayed in wild-type (wt) and lexA3 strain backgrounds (B). The higher dose could not be used in lexA3 experiments, because of enhanced lethality and selection for genetic suppressors. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals for mutation rates, mutations per cell generation.

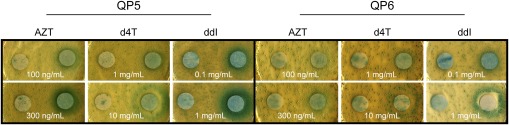

To extend these findings, using a disk-diffusion assay and lactose-papillation plates, we measured the effects of other known antiviral chain-terminators on template-switch mutagenesis (Fig. 3). On the papillation medium, Lac+ revertants stain blue with the chromogenic β-galactosidase substrate, X-gal, and outgrow from a white Lac− bacterial lawn (4). A blue halo of growth surrounding the discs impregnated with AZT provides a visual demonstration of the mutagenicity of the drug using the template-switch Lac-reversion reporters, QP5 and QP6. Dideoxyinosine (ddI, didanosine) and didehydro-deoxythymidine (D4T, stavudine) has been shown to be about 10-fold and 10,000-fold less potent, respectively, than AZT in inducing DNA damage in E. coli (18); a comparable mutagenic effect of the drug is clearly seen with the disk diffusion/papillation assay (Fig. 3). A potent effect of ddI, a purine derivative, shows that the mutagenic effect is not restricted to thymidine analogs.

Fig. 3.

Disk diffusion assay for Lac reversion using QP5 or QP6 and lactose X-gal papillation medium. Each disk on the right was impregnated with 40 μL of the drug (AZT, ddI, or D4T) at the indicated concentration whereas the control disk on the left was spotted with 40 μL of water.

A second class of mutational hotspots consists of deletion at short direct repeats (19, 20) that have to shown to arise from misalignment between nascent and template strands during DNA replication (21). Mutations in many components of the E. coli replication machinery strongly elevate deletion (22), leading us to suspect that they would be influenced by AZT. An 11-bp tandem repeat deletion events scored by our lacZ assay are not influenced by the mismatch-repair pathway (4).

Deletion of an 11-bp repeat in lacZ occurred at high rates; AZT induced rates of deletion in a dose-dependent manner, with a fourfold stimulation at 10 ng/mL AZT (Fig. 2). As seen for the templated mutations in quasipalindromes, blocking the induction of the SOS response enhanced the effects of AZT on 11-bp deletion rates.

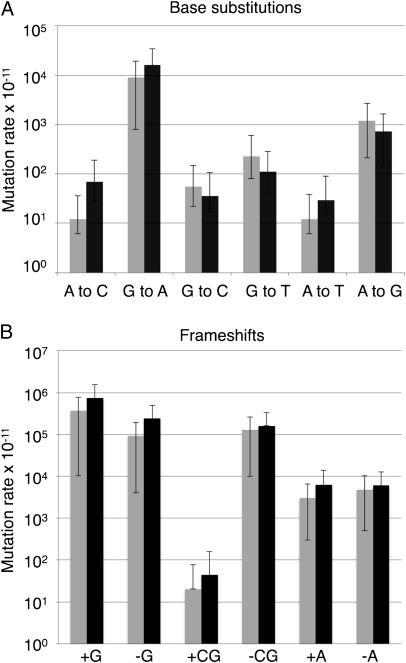

In a survey of base substitutions and frameshift mutations in a strain in which the mismatch repair pathway had been disabled, AZT had little effect, with stimulation at most 2.6-fold (Fig. 4). The notable exception was A-to-C transversions, which were stimulated six- to sevenfold, indicating that AZT exposure increases the occurrence of AT to CG mutations. The reason for this effect is not clear and may possibly be indirect through titration of repair factors or induction of the DNA damage response. This base substitution can result from either AG or TC mispairing. Adenine mispairs readily with oxidized guanine, 8-hydroxyguanine (23). Interestingly, TC mispairs are considerably more stable at the ends of duplexes (24), such as produced by AZT-mediated chain termination.

Fig. 4.

Effect of AZT on base substitutions (A) and frameshift mutations (B). Shown are rates for each specific mutation in mutS strains, without (gray bars) and with 10 ng/mL (black) AZT. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals for mutation rates, mutations per cell generation.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that although AZT is largely nonmutagenic for frameshift mutations and most base substitutions, it has especially potent effects on mutations associated with template-switching. Elevation of template-switch mutagenesis was shared by other chain-terminating nucleosides analogs used in HIV therapy, including ddI and D4T. This not only sheds light on potential side effects of chronic antiretroviral therapy in humans but also establishes these chain terminators as a specific class of mutagen, because of their potential to block DNA replication.

Several distinct mechanisms may contribute to AZT-provoked mutagenesis. AZT stimulated AT-to-CG transversions, independent of mismatch repair, consistent with stabilization of TC or AG mispairs. Deletions between short repeats were substantially induced by AZT, especially in strains that cannot mount the SOS response to DNA damage. This class can arise from a rearrangement-prone, template-switch repair pathway (25). Finally, template-switch-generated mutations in imperfect inverted repeat sequences (quasipalindromes) were strongly stimulated by AZT and may arise from release of DNA polymerase after chain termination, allowing more frequent nascent strand excursions and subsequent misalignments before or after the AZT-monophosphate moiety has been removed by exonuclease III. These may potentially occur during repair events of the single-strand DNA gaps or double-strand breaks in DNA that are promoted by AZT exposure (3).

Quasipalindrome-associated mutations are an important and undercharacterized mutational class and have been documented in bacteriophage, bacteria, yeast, and humans (11–16). It is unclear how widespread are such vulnerable targets, although evidence suggests that template-switch mutations are common in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Quasipalindrome-associated mutational hotspots are associated with two of the four loci in E. coli for which there are mutational spectra, thyA and rpsL (15, 16) but not lacI or rpoB (25, 26). A number of mutations causing human genetic syndromes are of this class (11); in addition, they comprise at least 5% of mutations that inactivate p53 in human tumors (12). Template-switching also is implicated in expansion of trinucleotide repeats associated with human genetic disease (10). Recent evidence shows that template-switch-generated mutations are prevalent outcomes of recombinational DNA double-strand break repair in yeast (27, 28). During the gene conversion events accompanying repair of an HO-induced break in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, template-switch mutations inactivating URA3 at natural quasipalindromes are elevated over 2,400 times that in spontaneous mutational spectra; intermolecular template-switching to ectopic sites is also detected (29). LYS2 mutations are elevated 3,000-fold during break-induced replication in S. cerevisiae, including a hotspot consistent with a template-switch at a 6-bp quasipalindrome sequence (28). Template-switching has been proposed as a driving force for structural variation in human genomes (8, 9).

Based on our understanding of the template-switch mechanism and its connection with replication difficulties, it is likely that other therapeutic agents will have properties similar to AZT, provoking mutations in quasipalindromes, as well as deletion and expansion of DNA direct repeats. This includes other antiviral chain-terminating nucleosides and replication inhibitors, such as hydroxyurea and topoisomerase II inhibitors used in cancer chemotherapy.

Materials and Methods

The mutational reporter strains used in this study have been described (4) and are derivatives of E. coli K-12 MG1655 and publicly available from the E. coli Genetic Stock Center (CGSC) (Yale University, New Haven, CT). The lexA3 mutation was introduced into mutational reporter strains constructed by P1 transduction with linked malF3190::Tn10-kan (strain STL6471), selecting kanamycin resistance and screening for UV sensitivity. Mutation rates per cell generation and 95% confidence intervals were determined using the Ma–Sandri–Sarkar method (29) as described previously (4) for at least 12 independent cultures grown in LB medium, with and without chronic exposure to azidothymidine (Sigma-Aldrich) at the indicated doses. QP-associated mutations were confirmed by restriction digestion of at least 12 independent revertants as described (4).

Lactose X-gal papillation plates (4) were used to detect mutations in the disk diffusion assayed. A lawn of ∼2 × 108 cells of strain STL14553 (QP5) or STL15654 (QP6) was spread on the plate. AZT, D4T (Sigma-Aldrich), or ddI (Sigma-Aldrich) were dissolved in water at the indicated concentrations, and 40 μL was spotted onto 15-mm Whatman no. 1 filter disks overlain on the bacterial lawn; controls included 40 μL of water spotted on a second disk. Plates were incubated at 37° for 2–3 d.

Acknowledgments

We thank Alexander Ferrazzoli for help with figure preparation and Deani Cooper for help with D4T assays. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 GM51753 and T32 007122 and National Science Foundation Grant MCB 064585.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Olivero OA. Mechanisms of genotoxicity of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2007;48:215–223. doi: 10.1002/em.20195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Agency for Research on Cancer Some antiviral and antineoplastic drugs and other pharmaceutical agents. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2000;76:1–521. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper DL, Lovett ST. Toxicity and tolerance mechanisms for azidothymidine, a replication gap-promoting agent, in Escherichia coli. DNA Repair (Amst) 2011;10:260–270. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seier T, et al. Insights into mutagenesis using Escherichia coli chromosomal lacZ strains that enable detection of a wide spectrum of mutational events. Genetics. 2011;188:247–262. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.127746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sassanfar M, Roberts JW. Nature of the SOS-inducing signal in Escherichia coli. The involvement of DNA replication. J Mol Biol. 1990;212:79–96. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90306-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jarosz DF, Beuning PJ, Cohen SE, Walker GC. Y-family DNA polymerases in Escherichia coli. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lovett ST. Encoded errors: Mutations and rearrangements mediated by misalignment at repetitive DNA sequences. Mol Microbiol. 2004;52:1243–1253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hastings PJ, Ira G, Lupski JR. A microhomology-mediated break-induced replication model for the origin of human copy number variation. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JA, Carvalho CMB, Lupski JR. A DNA replication mechanism for generating nonrecurrent rearrangements associated with genomic disorders. Cell. 2007;131:1235–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shishkin AA, et al. Large-scale expansions of Friedreich's ataxia GAA repeats in yeast. Mol Cell. 2009;35:82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bissler JJ. DNA inverted repeats and human disease. Front Biosci. 1998;3:d408–d418. doi: 10.2741/a284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenblatt MS, Grollman AP, Harris CC. Deletions and insertions in the p53 tumor suppressor gene in human cancers: Confirmation of the DNA polymerase slippage/misalignment model. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2130–2136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ripley LS. Model for the participation of quasi-palindromic DNA sequences in frameshift mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:4128–4132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.13.4128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stewart JW, Sherman F. Yeast frameshift mutants identified by sequence changes in iso-1-cytochrome C. In: Miller MW, editor. Molecular and environmental aspects of mutagenesis. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1974. pp. 102–127. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viswanathan M, Lacirignola JJ, Hurley RL, Lovett ST. A novel mutational hotspot in a natural quasipalindrome in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 2000;302:553–564. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshiyama K, Higuchi K, Matsumura H, Maki H. Directionality of DNA replication fork movement strongly affects the generation of spontaneous mutations in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:1195–1206. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dutra BE, Lovett ST. Cis and trans-acting effects on a mutational hotspot involving a replication template switch. J Mol Biol. 2006;356:300–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mamber SW, Brookshire KW, Forenza S. Induction of the SOS response in Escherichia coli by azidothymidine and dideoxynucleosides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1237–1243. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farabaugh PJ, Schmeissner U, Hofer M, Miller JH. Genetic studies of the lac repressor. VII. On the molecular nature of spontaneous hotspots in the lacI gene of Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1978;126:847–857. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schaaper RM, Danforth BN, Glickman BW. Mechanisms of spontaneous mutagenesis: An analysis of the spectrum of spontaneous mutation in the Escherichia coli lacI gene. J Mol Biol. 1986;189:273–284. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90509-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lovett ST, Feschenko VV. Stabilization of diverged tandem repeats by mismatch repair: Evidence for deletion formation via a misaligned replication intermediate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7120–7124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saveson CJ, Lovett ST. Enhanced deletion formation by aberrant DNA replication in Escherichia coli. Genetics. 1997;146:457–470. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.2.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maki H, Sekiguchi M. MutT protein specifically hydrolyses a potent mutagenic substrate for DNA synthesis. Nature. 1992;355:273–275. doi: 10.1038/355273a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanhommerig SA, van Genderen MH, Buck HM. A stable antiparallel cytosine-thymine base pair occurring only at the end of a duplex. Biopolymers. 1991;31:1087–1094. doi: 10.1002/bip.360310908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garibyan L, et al. Use of the rpoB gene to determine the specificity of base substitution mutations on the Escherichia coli chromosome. DNA Repair (Amst) 2003;2:593–608. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(03)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaaper RM, Dunn RL. Spectra of spontaneous mutations in Escherichia coli strains defective in mismatch correction: The nature of in vivo DNA replication errors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6220–6224. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.17.6220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Deem A, et al. Break-induced replication is highly inaccurate. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hicks WM, Kim M, Haber JE. Increased mutagenesis and unique mutation signature associated with mitotic gene conversion. Science. 2010;329:82–85. doi: 10.1126/science.1191125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarkar S, Ma WT, Sandri GH. On fluctuation analysis: A new, simple and efficient method for computing the expected number of mutants. Genetica. 1992;85:173–179. doi: 10.1007/BF00120324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]