Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the risk of second cancer (SC) in long-term survivors of retinoblastoma (Rb) according to classification of germline mutation, based on family history of Rb and laterality.

Patients and Methods

We assembled a cohort of 1,852 1-year survivors of Rb (bilateral, n = 1,036; unilateral, n = 816). SCs were ascertained by medical records and self-reports and confirmed by pathology reports. Classification of RB1 germline mutation, inherited or de novo, was inferred by laterality of Rb and positive family history of Rb. Standardized incidence ratios and cumulative incidence for all SCs combined and for soft tissue sarcomas, bone cancers, and melanoma were calculated. The influence of host- and therapy-related risk factors for SC was assessed by Poisson regression for bilateral survivors.

Results

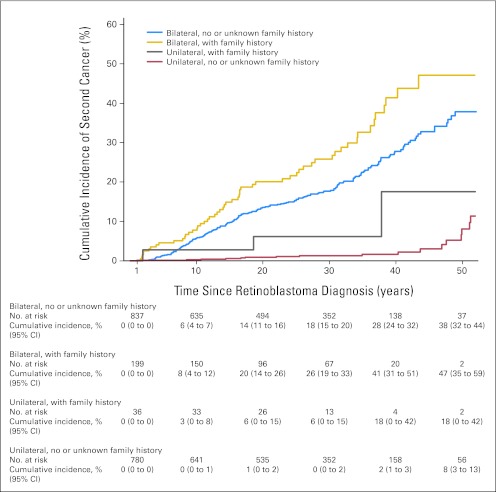

We observed a relative risk (RR) of 1.37 (95% CI, 1.00 to 1.86) for SCs in bilateral survivors associated with a family history of Rb, adjusted for treatment, age, and length of follow-up. The risk for melanoma was significantly elevated for survivors with a family history of Rb (RR, 3.08; 95% CI, 1.23 to 7.16), but risks for bone or soft tissue sarcomas were not elevated. The cumulative incidence of SCs 50 years after diagnosis of bilateral Rb, with adjustment for competing risk of death, was significantly higher for survivors with a family history (47%; 95% CI, 35% to 59%) than survivors without a family history (38%; 95% CI, 32% to 44%; P = .004).

Conclusion

Rb survivors with bilateral disease and an inherited germline mutation are at slightly higher risk of an SC compared with those with a de novo germline mutation, in particular melanoma, perhaps because of shared genetic alterations.

INTRODUCTION

Retinoblastoma (Rb) is a rare childhood tumor that is caused by mutations in the RB1 tumor suppressor gene. Twenty-five percent to 35% of children with Rb develop tumors in both eyes (bilateral) as a result of a germline mutation in the RB1 gene, and the other 65% to 75% of children with Rb develop tumors in only one eye (unilateral) usually caused by somatic mutations in the RB1 gene.1 Although all bilateral survivors are presumed to have a germline mutation, only approximately one third have inherited a mutation from a parent, whereas the other two thirds have a de novo germline mutation that occurs during formation of the sperm or egg from an unaffected parent.2,3 However, it has been estimated that up to 15% of children with unilateral Rb likely have a germline mutation.3–5 The presence of an inherited germline mutation in bilateral and unilateral survivors is often inferred based on a positive family history of Rb in the absence of mutation testing data.

Long-term survivors of bilateral Rb are at high risk of developing and dying from a second primary nonocular cancer (SC), whereas survivors of unilateral RB are at much lower risk.6–9 The risk for many of these SCs, such as bone and soft tissue sarcomas, has been attributed to genetic susceptibility and past treatment with radiotherapy.6,10,11 Studies of SC risk in Rb survivors have not assessed how the risk varies according to whether a RB1 germline mutation is inherited or de novo. This information could provide insight into biologic mechanisms and influence the screening recommendations for Rb survivors. We have estimated the risk of SCs according to laterality and family history of Rb, as a surrogate for mutation status, accounting for other host- and therapy-related factors that influence the risk of SC.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Population

We assembled a retrospective cohort of 1,991 Rb survivors who were diagnosed from January 1, 1914, to December 31, 1996, at two major medical centers in New York City and Boston. This cohort has been described in detail previously.11 We excluded 35 bilateral and 83 unilateral survivors who did not survive at least 1 year, 13 survivors who died out of country, one survivor without Rb, two survivors with consultation only, and five survivors with missing Rb diagnosis date, resulting in 1,852 Rb survivors eligible for analysis.

On the basis of data abstracted from medical records by trained abstractors from the two medical centers, we classified survivors according to laterality of their Rb, either bilateral (n = 1,036, 55.9%) or unilateral (n = 816, 44.1%), and family history of Rb (positive, negative, or unknown). Because data were collected retrospectively for survivors diagnosed over many decades, we learned about additional family members with Rb including offspring for some survivors in the medical records or at a later interview. Therefore, we restricted the definition of family history to first- or second-degree relatives with Rb, excluding offspring, who were mentioned in the medical records. We then cross-classified survivors into one of the following four groups: group 1, bilateral and positive family history (n = 199, 10.7%); group 2, bilateral and negative or unknown family history (n = 837, 45.2%); group 3, unilateral and positive family history (n = 36, 2.0%); and group 4, unilateral and negative or unknown family history (n = 780, 42.1%). Because genetic testing data were not available for all of the survivors in this study, we used laterality and family history as a surrogate for an inherited (groups 1 and 3) or de novo germline mutation (group 2).

Follow-Up Procedures

For survivors who were diagnosed with Rb from 1914 to 1984 (n = 1,599), abstractors recorded baseline information from hospital records on diagnosis, laterality, treatment, and family history of Rb as well as any mention of an SC. In addition, any SCs diagnosed up through December 31, 2001, were obtained by trained interviewers through three separate telephone interviews with survivors or parents, as described elsewhere.12 For survivors diagnosed after 1984 (n = 253), medical record abstraction took place in 1996, and parents of survivors were interviewed in 1998. In addition, periodic searches of the National Death Index were conducted to ascertain information on vital status and causes of deaths.11 The Special Studies Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Institute as well as the institutional review boards of the two participating medical centers approved the study.

Invasive SCs were confirmed by pathology reports whenever possible (62.8%), hospital or physician records (15.2%), autopsy (3.4%), or death certificates (18.6%). We excluded all in situ (except bladder cancer), benign tumors, and nonmelanoma skin cancers from this analysis. Pineoblastoma, an intracranial tumor often referred to as trilateral Rb, was included as an SC. A nosologist coded all confirmed cancers according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology.13

Statistical Analysis

Accrual of person-years of follow-up began 1 year after diagnosis and ended on the date of SC diagnosis, date of death, date last known alive, or end of study (December 31, 2001, for survivors diagnosed earlier than 1985 and December 31, 1998, for survivors diagnosed with Rb in 1985 or later), whichever occurred first.

Standardized incidence ratios.

We estimated the standardized incidence ratio (SIR) and 95% CIs for all SCs combined, excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer, and for seven of the most common SCs in Rb survivors (cancers of the bone, soft tissue, eye/orbit, nasal cavities, and brain, melanoma, and pineoblastoma) for the four Rb groups defined earlier. We compared the observed number of cancers to the expected number of SCs based on the age-, sex-, and 5-year (calendar year) –specific incidence rates from the Connecticut Tumor Registry for 1935 to 1972 and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program from 1973 onward, not adjusted for race or ethnicity. For expected cancer rates before 1935, when the Connecticut Tumor Registry began, we used rates for 1935 to 1939. Comparisons of SIRs were based on the χ2 test of homogeneity.14

Cumulative incidence.

The cumulative incidence for all SCs combined was calculated individually for the four Rb groups by decade up to 50 years after Rb diagnosis. In addition, we calculated the cumulative incidence for cancers of the bone, soft tissue sarcoma, and melanoma in bilateral survivors with and without a family history of Rb at 20 and 50 years after Rb diagnosis. We used the cumulative incidence method of Gray implemented in the cmprsk package in R statistical software.15 For the cumulative incidence of all SCs combined, we treated deaths from Rb or from noncancer causes as competing risks, whereas for cumulative incidence of specific cancers, we also treated death from SCs other than the specific cancer of interest as a competing risk.

Univariate and multivariate analyses.

Because SCs mainly occurred in bilateral survivors, we limited the evaluation of risk factors to this group. We also excluded bilateral patients whose radiotherapy or chemotherapy status was unknown. The main variables of interest were family history (yes v no or unknown), sex, age at Rb diagnosis (< 12, 12 to 23, or ≥ 24 months), calendar year of Rb (< or ≥ 1970) to reflect changes in treatment patterns after 1970, radiotherapy for Rb (yes or no), chemotherapy for Rb (yes or no), and attained age (ie, age at end of follow-up; < 10, 10 to 19, 20 to 29, 30 to 39, or ≥ 40 years). We fitted a Poisson regression model that examined the association of each variable individually (unadjusted relative risk [RR]) and simultaneously (adjusted RR) for all SCs and individually for bone cancer, soft tissue cancer, and melanoma using Epicure software (HiroSoft International, Seattle, WA).16 We fitted the model excluding survivors with unknown family history, and because the results remained essentially the same, they were retained in the model. We defined soft tissue sarcomas by morphology codes to be consistent with previous analyses in this cohort.17

The statistical significance of each factor was assessed by a likelihood ratio test18 comparing the model with the factor of interest and the model without the factor. All P values are two-sided.

RESULTS

Survivor Characteristics

Table 1 lists selected demographic and treatment characteristics by laterality and family history of Rb. Overall, 13% of all Rb survivors had a positive family history of Rb (11% bilateral and 2% unilateral). We compared characteristics of the bilateral survivors with a negative family history (78%) with survivors with unknown family history (22%), and we found significant differences only in calendar year of Rb diagnosis and attained age, because there were a lot less survivors with unknown family history in the more recent years. Otherwise, both groups of bilateral survivors were similar (Appendix Table A1, online only).

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of 1,852 1-Year Survivors of Retinoblastoma, Diagnosed From 1914 to 1996

| Demographic or Clinical Characteristic | Bilateral Survivors (n = 1,036) |

Unilateral Survivors (n = 816) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family History |

No Family History* |

P | Family History |

No Family History† |

P | |||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |||

| Survivors | 199 | 10.7 | 837 | 45.2 | 36 | 1.9 | 780 | 42.1 | ||

| Sex | .626 | .564 | ||||||||

| Male | 107 | 53.8 | 434 | 51.8 | 20 | 55.6 | 395 | 50.6 | ||

| Female | 92 | 46.2 | 403 | 48.2 | 16 | 44.4 | 385 | 49.4 | ||

| Age at Rb diagnosis, months | < .001 | < .001 | ||||||||

| < 12 | 153 | 76.9 | 454 | 54.2 | 19 | 52.8 | 173 | 22.2 | ||

| 12-23 | 29 | 14.6 | 251 | 30.0 | 10 | 27.8 | 224 | 28.7 | ||

| 24+ | 17 | 8.5 | 132 | 15.8 | 7 | 19.4 | 383 | 49.1 | ||

| Calendar year of Rb diagnosis | < .001 | .448 | ||||||||

| < 1960 | 45 | 22.6 | 252 | 30.1 | 5 | 13.9 | 178 | 22.8 | ||

| 1960-1969 | 48 | 24.1 | 245 | 29.3 | 8 | 22.2 | 205 | 26.3 | ||

| 1970-1979 | 45 | 22.6 | 195 | 23.3 | 12 | 33.3 | 196 | 25.1 | ||

| 1980+ | 61 | 30.7 | 145 | 17.3 | 11 | 30.6 | 201 | 25.8 | ||

| Median year | 1970 | 1966 | 1975 | 1970 | ||||||

| Radiation | .344 | < .001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 184 | 92.5 | 747 | 89.3 | 20 | 55.6 | 138 | 17.7 | ||

| No | 14 | 7.0 | 87 | 10.4 | 16 | 44.4 | 635 | 81.4 | ||

| Unknown | 1 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0.9 | ||

| Chemotherapy | .358 | .784 | ||||||||

| Yes | 72 | 36.2 | 349 | 41.7 | 5 | 13.9 | 101 | 12.9 | ||

| No | 123 | 61.8 | 474 | 56.6 | 31 | 86.1 | 669 | 85.8 | ||

| Unknown | 4 | 2.0 | 14 | 1.7 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 1.3 | ||

| Attained age, years | .002 | .077 | ||||||||

| < 10 | 47 | 23.6 | 183 | 21.9 | 3 | 8.3 | 113 | 14.5 | ||

| 10-19 | 55 | 27.6 | 139 | 16.6 | 5 | 13.9 | 101 | 12.9 | ||

| 20-29 | 29 | 14.6 | 136 | 16.2 | 13 | 36.1 | 169 | 21.7 | ||

| 30-39 | 46 | 23.1 | 224 | 26.8 | 11 | 30.6 | 186 | 28.9 | ||

| 40+ | 22 | 11.1 | 155 | 18.5 | 4 | 11.1 | 211 | 27.0 | ||

| Median follow-up, years | ||||||||||

| Median | 19 | 26 | 25 | 28 | ||||||

| Range | 1-55 | 1-69 | 1-56 | 1-77 | ||||||

Abbreviation: Rb, retinoblastoma.

Includes 653 survivors with no family history and 184 survivors with unknown family history.

Includes 641 survivors with no family history and 139 survivors with unknown family history.

SIRs

The risk of SCs, excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer, compared with the general population rates revealed significantly elevated SIRs for bilateral survivors with a family history (SIR, 36; 95% CI, 27 to 46) compared with survivors without a family history (SIR, 19; 95% CI, 16 to 22; P < .001; Table 2). A significantly higher risk was noted also for melanoma among bilateral survivors with a family history compared with those without a family history (SIR, 66; 95% CI, 29 to 129; and SIR, 20; 95% CI, 11 to 32, respectively; P = .003), and likewise for pineoblastoma (SIR, 584; 95% CI, 214 to > 1,000; and SIR, 44; 95% CI, 5.4 to 161, respectively; P = .004). We noted similarly increased risks for cancers of the bone, soft tissue, eye/orbit, and nasal cavities in bilateral survivors independent of family history. Among unilateral survivors, the risk for SCs was statistically significantly increased for survivors with a family history based on only three SCs (soft tissue sarcoma, melanoma, and Hodgkin's lymphoma), but not for survivors without a family history (SIR, 7.1; 95% CI, 1.5 to 21; and SIR, 1.52; 95% CI, 0.9 to 2.3, respectively; P = .004).

Table 2.

Risk of Second Cancer in 1,852 1-Year Survivors of Retinoblastoma, Diagnosed From 1914 to 1996

| Second Cancer | Bilateral Survivors |

Unilateral Survivors |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family History (n = 199) | No or Unknown Family History (n = 837) | Family History (n = 36) | No or Unknown Family History (n = 780) | |

| No. of person-years | 4,065 | 19,739 | 898 | 20,504 |

| All cancers (ICD-O 140-172, 174-207) | ||||

| Observed No. of cancers | 56* | 188† | 3‡ | 22§ |

| Expected No. of cancers | 1.6 | 10.1 | 0.4 | 14.5 |

| SIR | 35.8 | 19 | 7.1 | 1.52 |

| 95% CI | 27 to 46 | 16 to 22 | 1.5 to 21 | 0.9 to 2.3 |

| AER∥ | 133 | 90 | 29 | 3.7 |

| Bone (ICD-O 170) | ||||

| Observed No. of cancers | 15 | 62 | 0 | 0 |

| Expected No. of cancers | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.17 |

| SIR | 459 | 388 | 0 | 0 |

| 95% CI | 259 to 757 | 297 to 497 | 0 to 460 | 0 to 21 |

| AER∥ | 37 | 35 | −0.09 | −0.08 |

| Soft tissue (ICD-O 171, 192.4, 192.5) | ||||

| Observed No. of cancers | 10 | 25 | 1 | 0 |

| Expected No. of cancers | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.23 |

| SIR | 233 | 118 | 106 | 0 |

| 95% CI | 112 to 428 | 76 to 174 | 2.7 to 594 | 0.0 to 16 |

| AER∥ | 24 | 13 | 11 | −0.11 |

| Cutaneous melanoma (ICD-O 173, M872-M879) | ||||

| Observed No. of cancers | 8 | 15 | 1 | 0 |

| Expected No. of cancers | 0.12 | 0.77 | 0.03 | 0.99 |

| SIR | 65.5 | 19.6 | 35 | 0 |

| 95% CI | 29 to 129 | 11 to 32 | 0.9 to 193 | 0 to 3.6 |

| AER∥ | 19 | 7.2 | 6.3 | −0.5 |

| Eye/orbit (ICD-O 190) | ||||

| Observed No. of cancers | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Expected No. of cancers | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.05 |

| SIR | 177 | 155 | 0 | 0 |

| 95% CI | 21 to 640 | 67 to 305 | 0 to > 1,000 | 0 to 73 |

| AER∥ | 4.9 | 4.0 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| Nasal cavities (ICD-O 160) | ||||

| Observed No. of cancers | 7 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| Expected No. of cancers | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.03 |

| SIR | 2,000 | 1,041 | 0 | 0 |

| 95% CI | 803 to > 1,000 | 652 to > 1,000 | 0 to > 1,000 | 0 to 132 |

| AER∥ | 17 | 11 | −0.01 | −0.01 |

| Brain, CNS (ICD-O 191, 192.0-192.3, 192.9) | ||||

| Observed No. of cancers | 2 | 9 | 0 | 2 |

| Expected No. of cancers | 0.12 | 0.57 | 0.03 | 0.63 |

| SIR | 16.7 | 15.7 | 0.0 | 3.2 |

| 95% CI | 2.0 to 60 | 7.2 to 30 | 0 to 146 | 0.4 to 11 |

| AER∥ | 4.6 | 4.3 | −0.28 | 0.7 |

| Pineoblastoma (ICD-O 194.4) | ||||

| Observed No. of cancers | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Expected No. of cancers | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.0 | 0.04 |

| SIR | 584 | 44.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 95% CI | 214 to > 1,000 | 5.4 to 161 | 0 to > 1,000 | 0 to 82 |

| AER∥ | 14.7 | 1.0 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

Abbreviations: AER, absolute excess risk; ICD-O, International Classification of Diseases for Oncology; SIR, standardized incidence ratio.

Other cancers include two digestive (one colon and one small intestine), one other respiratory, one acute lymphocytic leukemia, and two of unknown primary site.

Other cancers include two tongue, two salivary gland, two nasopharynx, two colon, three lung, three other respiratory, eight female breast, one male breast, five corpus uteri, one testis, one kidney, three bladder, two thyroid, one non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, two Hodgkin's lymphoma, one lymphocytic leukemia not otherwise specified, and six of unknown primary site.

Other cancer includes one Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Other cancers include seven female breast, two thyroid, two uterine corpus, one rectum, one prostate, one kidney, one Hodgkin's lymphoma, one acute myeloid leukemia, and four of unknown primary site.

Observed No. − expected No./person-years × 10,000.

Univariate and Multivariate Analyses

We noted a borderline elevated risk in SCs associated with a family history of Rb in bilateral survivors (adjusted RR [RRadj], 1.37; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.86; P = .05; Table 3). Risk of SCs decreased significantly with increasing age at Rb diagnosis from RRadj of 1.0, 0.81, and 0.50 for survivors treated at less than 12, 12 to 23, and ≥ 24 months of age (P = .005). Female sex was related to a borderline increased RR of SC (RRadj, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.00 to 1.66; P = .05). Other risk factors significantly related to an increased risk of SCs were radiation treatment for Rb (P = .001) and older attained age at SC (P < .001). Among survivors diagnosed with a bone cancer, radiotherapy (P = .006), chemotherapy (P = .03), and older attained age (P < .001) were all significantly related to an increased risk, but not family history of Rb (P = .79). Significantly increased risks for soft tissue sarcoma were associated with radiotherapy (P = .006) and older attained age (P < .001), and significantly decreased risks were related to older age at Rb diagnosis (P = .008).

Table 3.

RR of Second Cancer in 1,015 1-Year Survivors of Bilateral Rb

| Factor | All Second Cancers |

Bone Cancer |

Soft Tissue Sarcoma* |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Cancers | Crude Analysis |

Adjusted Analysis |

No. of Cancers | Crude Analysis |

Adjusted Analysis |

No. of Cancers | Crude Analysis |

Adjusted Analysis |

|||||||||||||

| RR | 95% CI | PLRT | RR | 95% CI | PLRT | RR | 95% CI | PLRT | RR | 95% CI | PLRT | RR | 95% CI | PLRT | RR | 95% CI | PLRT | ||||

| Family history of Rb | .08 | .05 | .99 | .79 | .89 | .97 | |||||||||||||||

| No/unknown | 187 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | 62 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | 50 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 52 | 1.33 | 0.97 to 1.79 | 1.37 | 1.00 to 1.86 | 13 | 1.00 | 0.53 to 1.76 | 0.92 | 0.48 to 1.64 | 10 | 0.96 | 0.46 to 1.80 | 0.99 | 0.47 to 1.87 | ||||||

| Sex | .05 | .05 | .72 | .73 | .35 | .30 | |||||||||||||||

| Male | 114 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | 42 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | 36 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||||||||||||

| Female | 125 | 1.29 | 1.00 to 1.66 | 1.29 | 1.00 to 1.66 | 33 | 0.92 | 0.58 to 1.45 | 0.92 | 0.58 to 1.46 | 24 | 0.78 | 0.46 to 1.30 | 0.76 | 0.45 to 1.27 | ||||||

| Age at Rb diagnosis, months | .01 | .005 | .48 | .34 | .01 | .008 | |||||||||||||||

| < 12 | 153 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | 47 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | 36 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||||||||||||

| 12-23 | 65 | 0.84 | 0.62 to 1.11 | 0.81 | 0.60 to 1.08 | 20 | 0.84 | 0.49 to 1.39 | 0.89 | 0.51 to 1.49 | 22 | 1.20 | 0.70 to 2.03 | 1.14 | 0.66 to 1.93 | ||||||

| 24+ | 21 | 0.53 | 0.33 to 0.82 | 0.50 | 0.31 to 0.78 | 8 | 0.66 | 0.29 to 1.32 | 0.71 | 0.31 to 1.43 | 2 | 0.21 | 0.04 to 0.70 | 0.19 | 0.03 to 0.64 | ||||||

| Calendar year of Rb diagnosis | .02 | .61 | .46 | .76 | .21 | .69 | |||||||||||||||

| < 1970 | 182 | 1.41 | 1.06 to 1.92 | 1.09 | 0.79 to 1.52 | 49 | 0.83 | 0.52 to 1.36 | 0.93 | 0.57 to 1.55 | 46 | 1.46 | 0.82 to 2.75 | 0.87 | 0.45 to 1.75 | ||||||

| 1970+ | 57 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | 26 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | 14 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||||||||||||

| Radiotherapy for Rb | < .001 | .001 | < .001 | .006 | .004 | .006 | |||||||||||||||

| No | 12 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | 1 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | 1 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 227 | 2.37 | 1.39 to 4.47 | 2.37 | 1.37 to 4.52 | 74 | 9.26 | 2.06 to 163.3 | 7.05 | 1.55 to 124.8 | 59 | 7.38 | 1.63 to 130.4 | 7.16 | 1.55 to 127.1 | ||||||

| Chemotherapy for Rb | .06 | .18 | .02 | .03 | .15 | .29 | |||||||||||||||

| No | 127 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | 34 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | 30 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 112 | 1.28 | 0.99 to 1.65 | 1.20 | 0.92 to 1.56 | 41 | 1.75 | 1.11 to 2.78 | 1.71 | 1.07 to 2.76 | 30 | 1.45 | 0.87 to 2.42 | 1.32 | 0.78 to 2.23 | ||||||

| Attained age, years | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | |||||||||||||||

| < 10 | 49 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | 23 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | 10 | 1.0 | (Ref) | 1.0 | (Ref) | ||||||||||

| 10-19 | 80 | 1.90 | 1.34 to 2.73 | 1.98 | 1.39 to 2.85 | 41 | 2.07 | 1.26 to 3.51 | 2.12 | 1.28 to 3.59 | 19 | 2.21 | 1.05 to 4.95 | 2.30 | 1.09 to 5.15 | ||||||

| 20-29 | 34 | 1.06 | 0.68 to 1.64 | 1.12 | 0.71 to 1.73 | 7 | 0.47 | 0.18 to 1.03 | 0.48 | 0.19 to 1.07 | 6 | 0.92 | 0.31 to 2.47 | 0.98 | 0.33 to 2.66 | ||||||

| 30-39 | 46 | 2.47 | 1.65 to 3.69 | 2.61 | 1.71 to 3.97 | 3 | 0.34 | 0.08 to 0.98 | 0.36 | 0.08 to 1.05 | 19 | 4.99 | 2.37 to 11.18 | 5.52 | 2.51 to 12.93 | ||||||

| 40+ | 30 | 3.77 | 2.37 to 5.91 | 4.51 | 2.77 to 7.24 | 1 | 0.27 | 0.01 to 1.27 | 0.33 | 0.02 to 1.60 | 6 | 3.70 | 1.26 to 9.95 | 5.01 | 1.64 to 14.20 | ||||||

NOTE. Adjusted RR is from multivariate Poisson regression model adjusting for all other variables in the table. Twenty-one survivors whose radiotherapy or chemotherapy information was unknown were excluded from analysis.

Abbreviations: LRT, likelihood ratio test; Rb, retinoblastoma; Ref, reference; RR, relative risk.

Includes International Classification of Diseases for Oncology morphology codes M8800-8804, 8810-8814, 8830-8833, 8850-8855, 8890-8891, 8894-8895, 8900-8902, 8920, 8990, 9040, 9120, and 9560.

Family history of Rb significantly increased melanoma risk three-fold compared with bilateral survivors with no family history (RRadj, 3.08; 95% CI, 1.23 to 7.16; P = .02; Table 4). Other risk factors significantly associated with melanoma were Rb diagnosis before 1970 (P = .03) and attained age of 25 years and older (P < .001).

Table 4.

RR of Melanoma in 1,015 1-Year Survivors of Bilateral Rb

| Factor | Melanoma |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Melanomas | Crude Analysis |

Adjusted Analysis |

|||||

| RR | 95% CI | PLRT | RR | 95% CI | PLRT | ||

| Family history of Rb | .02 | .02 | |||||

| No/unknown | 15 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||||

| Yes | 8 | 2.55 | 1.03 to 5.86 | 3.08 | 1.23 to 7.16 | ||

| Sex | .15 | .12 | |||||

| Male | 9 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||||

| Female | 14 | 1.82 | 0.80 to 4.38 | 1.92 | 0.84 to 4.65 | ||

| Age at Rb diagnosis, months | .42 | .29 | |||||

| < 12 | 16 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||||

| 12-23 | 5 | 0.61 | 0.20 to 1.57 | 0.52 | 0.17 to 1.36 | ||

| 24+ | 2 | 0.48 | 0.08 to 1.70 | 0.45 | 0.07 to 1.62 | ||

| Calendar year of Rb diagnosis | .001 | .03 | |||||

| < 1970 | 22 | 9.74 | 2.05 to 174.3 | 5.99 | 1.15 to 110 | ||

| 1970+ | 1 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||||

| Radiotherapy for Rb | .70 | .50 | |||||

| No | 2 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||||

| Yes | 21 | 1.31 | 0.39 to 8.21 | 1.46 | 0.40 to 9.32 | ||

| Chemotherapy for Rb | .79 | .68 | |||||

| No | 13 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||||

| Yes | 10 | 1.12 | 0.48 to 2.54 | 0.83 | 0.35 to 1.95 | ||

| Attained age, years | < .001 | < .001 | |||||

| < 25 | 6 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||||

| 25+ | 17 | 7.41 | 3.08 to 20.53 | 6.28 | 2.55 to 17.8 | ||

NOTE. Adjusted RR is from multivariate Poisson regression model adjusting for all other variables in the table. Twenty-one survivors whose radiotherapy or chemotherapy information was unknown were excluded from analysis.

Abbreviations: LRT, likelihood ratio test; Rb, retinoblastoma; Ref, reference; RR, relative risk.

Cumulative Incidence of SCs

Figure 1 illustrates the cumulative incidence of SCs by decade for each of the four Rb groups up to 50 years after Rb diagnosis. The cumulative incidence of any SC for bilateral survivors at 50 years after diagnosis of Rb was significantly higher for those with a family history than those without a family history (47%; 95% CI, 35% to 59%; v 38%; 95% CI, 32% to 44%, respectively; P = .004). Among the unilateral survivors, the cumulative incidence reached 18% (95% CI, 0.0% to 42%) at 50 years for survivors with a family history and 8% (95% CI, 3% to 13%) for survivors without a family history, although the number of cancers was sparse in the unilateral family history group.

Fig 1.

Cumulative incidence percent of second cancers by decade up to 50 years after retinoblastoma diagnosis in 1,852 1-year survivors of retinoblastoma by family history and laterality.

The cumulative incidence of bone cancer and soft tissue sarcoma after bilateral Rb did not differ by family history (Table 5), although there was a three-fold difference in the cumulative incidence of soft tissue sarcomas at 50 years compared with 20 years. At 20 years, only three melanomas had occurred in survivors with family history, whereas none had occurred in survivors without a family history. Fifty years after Rb, the cumulative incidence of melanoma was 9% (95% CI, 3% to 15%) for survivors with a family history versus 2% (95% CI, 0.9% to 4%) for survivors with no family history.

Table 5.

Cumulative Incidence of Second Bone Cancer, Soft Tissue Sarcoma, and Melanoma in 1,036 1-Year Survivors of Bilateral Retinoblastoma by Family History of Retinoblastoma

| Second Cancer | Years Since Retinoblastoma Diagnosis |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 Years |

50 Years |

|||||

| No. of Cancers | Cumulative Incidence (%) | 95% CI (%) | No. of Cancers | Cumulative Incidence (%) | 95% CI (%) | |

| Bone cancer | ||||||

| No/unknown family history | 55 | 7 | 5 to 9 | 62 | 9 | 7 to 11 |

| With family history | 13 | 8 | 4 to 11 | 15 | 10 | 5 to 16 |

| Soft tissue sarcoma (morphology) | ||||||

| No/unknown family history | 26 | 3 | 2 to 5 | 51 | 11 | 8 to 15 |

| With family history | 6 | 4 | 1 to 7 | 11 | 9 | 4 to 15 |

| Melanoma | ||||||

| No/unknown family history | 0 | 0 | 15 | 4 | 1 to 6 | |

| With family history | 3 | 2 | 0 to 4 | 8 | 7 | 2 to 12 |

DISCUSSION

Using bilaterality and positive family history as a surrogate for the presence of an inherited germline RB1 mutation, we found that bilateral Rb survivors with a presumed inherited germline mutation had a borderline significant 37% increased risk of an SC compared with survivors who had a presumed de novo germline mutation. This is the first report, to our knowledge, to estimate the risks for SCs by Rb mutation classification (inherited or de novo) taking treatment and other factors into account. As expected, SIRs compared with the general population were elevated for three of the four Rb survivor groups (bilateral with and without family history and unilateral with family history). We noted that the SIR for all SCs combined for bilateral survivors with a family history was significantly greater than the risk for bilateral survivors without a family history of Rb. Restricting the analysis to an internal comparison of SC risk in bilateral survivors allowed us to evaluate the influence of family history in the presence of other risk factors that have been linked to SCs, including radiotherapy, chemotherapy, young age at Rb diagnosis, and attained age, and to simultaneously control for genetic susceptibility.

Among the three most common SCs occurring after bilateral Rb (bone and soft tissue cancer and melanoma), family history of Rb was consistently significantly associated with risk for only melanoma in both the SIR and the multivariate analyses. Melanoma likely accounted for some of the significant excess risk of SCs in bilateral survivors with a family history of Rb in the SIR analysis. Treatment for Rb exerted a stronger effect than family history for the risks of bone and soft tissue sarcomas (ie, radiation for soft tissue sarcoma and radiation and chemotherapy for bone). An increased incidence of bone cancer after Rb has been previously been associated in a dose-dependent manner with chemotherapy, in addition to a dose-related increased risk with radiotherapy,19,20 whereas a radiation dose-related increased risk of soft tissue sarcomas after Rb has been observed.10 In this cohort, approximately 70% of the bone and soft tissue sarcomas occurred in the radiation field.10,17

Not unexpectedly, melanoma risk was significantly related to older attained age and earlier calendar year of Rb diagnosis, because melanoma risk usually starts to increase at age 20 years in the general population.21 Two of the 23 survivors reported multiple melanomas, but family history of melanoma was not specifically queried. The site distribution of the melanomas was consistent with the distribution in the general population.21 Ultraviolet exposure is a strong risk factor for melanoma; however, we did not have sufficient data to evaluate this exposure. Additionally, the cumulative incidence for melanoma was related to both family history of Rb and time since Rb diagnosis. Taken together, these findings indicate that having an inherited germline mutation is more likely than a de novo germline mutation to predispose to melanoma. An explanatory mechanism is not obvious but may be related to other shared genetic changes.

In contrast, the cumulative incidence for bone and soft tissue cancer did not differ by family history; however, the cumulative risk for soft tissue sarcomas increased three-fold from 20 to 50 years after Rb, consistent with a previous report of increased risk for leiomyosarcomas between ages 30 and 50 years in this cohort.17 The cumulative risk of bone cancer did not differ appreciably between 20 and 50 years after Rb because the majority of bone cancers usually occur by age 29.9 The cumulative risk for bone cancer at 20 years in this cohort (7% for no family history and 8% for family history) agrees with a report by Hawkins et al19 of a cumulative risk of 7.2% at 20 years among 3-year survivors of heritable Rb.

Several other cancers also occurred in excess in the bilateral survivors, but only the SIR for pineoblastoma was greater in bilateral survivors with a family history. However, the small number of cases precluded any meaningful analysis. On the basis of the higher incidence of pineoblastomas from a meta-analysis, additional pineoblastomas may have occurred in this cohort and been missed because they were attributed to metastatic Rb.22

Not surprisingly, the risks for SCs differed among survivors with unilateral Rb by family history. Although we had only 36 unilateral survivors with a family history of Rb who developed three subsequent cancers, it was clear that the risk for a SC was approximately five times greater compared with unilateral survivors without a family history. Despite this increased risk, we did not combine these unilateral with bilateral survivors, because those with unilateral Rb were phenotypically different and their germline mutations may represent mosaicism or mutations with lower penetrance. We do not have the data to adequately address this issue. Interestingly, the proportion of mosaics has been reported to differ only slightly among bilateral survivors (5.5%) and unilateral survivors (3.8%).5

A weakness of the present study is that we did not confirm the presence of germline mutations, but relied on reports of family history from medical records. For a proportion of bilateral and unilateral survivors, family history was unknown, and it is possible that some of the bilateral and unilateral survivors were misclassified and actually had a family history of Rb. The proportion of survivors with a positive family history is consistent with some population-based studies23–25 and other clinical or register-based series26,27; however, the generalizability of these results is limited to other hospital-based series. Although there are survivors older than 50 years of age, the cumulative incidence at 50 years is based on sparse data.

These data provide new clinical information for survivors, their parents, and their health care providers on the risk of SCs according to family history of Rb and presumed classification of germline mutation, which has not been available previously. The risk for melanoma seems to be higher for bilateral survivors with a family history of Rb, or an inherited germline mutation, compared with survivors with a de novo mutation in this large cohort of long-term survivors. All bilateral survivors, especially those with a family history of Rb, and their affected family members should be alert to the risk of melanoma, especially that posed by excessive sun exposure. Genotyping bilateral survivors with a melanoma should further elucidate the genetic link between these two cancers. Unilateral survivors with a family history of Rb should be screened for SCs according to the same guidelines as bilateral survivors.

Appendix

Table A1.

Distribution of Key Characteristics Among 821 1-Year Survivors of Bilateral Rb With No Known Family History or Unknown Family History of Rb

| Characteristic | Family History of Rb |

P* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No |

Unknown |

||||

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| No. of survivors | 639 | 77.8 | 182 | 22.2 | |

| Sex | .34 | ||||

| Male | 338 | 52.9 | 89 | 48.9 | |

| Female | 301 | 47.1 | 93 | 51.1 | |

| Age at Rb diagnosis, months | .32 | ||||

| < 12 | 350 | 54.8 | 96 | 52.7 | |

| 12-23 | 195 | 30.5 | 51 | 28.0 | |

| 24+ | 94 | 14.7 | 35 | 19.2 | |

| Calendar year at Rb diagnosis | < .001 | ||||

| < 1960 | 179 | 28.0 | 72 | 39.6 | |

| 1960-1969 | 187 | 29.3 | 53 | 29.1 | |

| 1970-1979 | 136 | 21.3 | 50 | 27.5 | |

| 1980+ | 137 | 21.4 | 7 | 3.8 | |

| Radiotherapy for Rb | .816 | ||||

| Yes | 572 | 89.5 | 164 | 90.1 | |

| No | 67 | 10.5 | 18 | 9.9 | |

| Attained age, years | < .001 | ||||

| < 10 | 102 | 16.0 | 79 | 43.4 | |

| 10-19 | 110 | 17.2 | 29 | 15.9 | |

| 20-29 | 109 | 17.0 | 20 | 11.0 | |

| 30-39 | 185 | 29.0 | 36 | 19.8 | |

| 40+ | 133 | 20.8 | 18 | 9.9 | |

| Chemotherapy for Rb | .59 | ||||

| Yes | 365 | 57.1 | 108 | 59.3 | |

| No | 274 | 42.9 | 74 | 40.7 | |

NOTE. Sixteen bilateral Rb survivors whose radiotherapy (n = 3) or chemotherapy (n = 13) information was unknown were excluded from analysis.

Abbreviation: Rb, retinoblastoma.

P value from χ2 test.

Footnotes

Supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health and the National Cancer Institute.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Ruth A. Kleinerman, Margaret A. Tucker

Provision of study materials or patients: David Abramson, Johanna Seddon

Collection and assembly of data: Ruth A. Kleinerman, David Abramson, Johanna Seddon

Data analysis and interpretation: Ruth A. Kleinerman, Chu-ling Yu, Mark P. Little, Yi Li, Johanna Seddon, Margaret A. Tucker

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Knudson AG., Jr Mutation and cancer: Statistical study of retinoblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971;68:820–823. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.4.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dryja TP, Mukai S, Petersen R, et al. Parental origin of mutations of the retinoblastoma gene. Nature. 1989;339:556–558. doi: 10.1038/339556a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Little MP, Kleinerman RA, Stiller CA, et al. Analysis of retinoblastoma age incidence data using a fully stochastic cancer model. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:631–640. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richter S, Vandezande K, Chen N, et al. Sensitive and efficient detection of RB1 gene mutations enhances care for families with retinoblastoma. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:253–269. doi: 10.1086/345651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rushlow D, Piovesan B, Zhang K, et al. Detection of mosaic RB1 mutations in families with retinoblastoma. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:842–851. doi: 10.1002/humu.20940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Draper GJ, Sanders BM, Kingston JE. Second primary neoplasms in patients with retinoblastoma. Br J Cancer. 1986;53:661–671. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1986.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eng C, Li FP, Abramson DH, et al. Mortality from second tumors among long-term survivors of retinoblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1121–1128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.14.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fletcher O, Easton D, Anderson K, et al. Lifetime risks of common cancers among retinoblastoma survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:357–363. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marees T, Moll AC, Imhof SM, et al. Risk of second malignancies in survivors of retinoblastoma: More than 40 years of follow-up. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1771–1779. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wong FL, Boice JD, Jr, Abramson DH, et al. Cancer incidence after retinoblastoma: Radiation dose and sarcoma risk. JAMA. 1997;278:1262–1267. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.15.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu CL, Tucker MA, Abramson DH, et al. Cause-specific mortality in long-term survivors of retinoblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:581–591. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kleinerman RA, Tucker MA, Tarone RE, et al. Risk of new cancers after radiotherapy in long-term survivors of retinoblastoma: An extended follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2272–2279. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fritz AG. ed 3. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology: ICD-O. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical methods in cancer research: volume II—the design and analysis of cohort studies. IARC Sci Publ. 1987;82:1–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16:1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Preston DL, Rubin JH, Pierce DA, et al. Seattle, WA: HiroSoft International; 1993. Epicure: User's Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleinerman RA, Tucker MA, Abramson DH, et al. Risk of soft tissue sarcomas by individual subtype in survivors of hereditary retinoblastoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:24–31. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cox CE, Hinkley DV. London, United Kingdom: Chapman and Hall; 1974. Theoretical Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hawkins MM, Wilson LM, Burton HS, et al. Radiotherapy, alkylating agents, and risk of bone cancer after childhood cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:270–278. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.5.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tucker MA, D'Angio GJ, Boice JD, Jr, et al. Bone sarcomas linked to radiotherapy and chemotherapy in children. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:588–593. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198709033171002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradford PT, Anderson WF, Purdue MP, et al. Rising melanoma incidence rates of the trunk among younger women in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:2401–2406. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kivelä T. Trilateral retinoblastoma: A meta-analysis of hereditary retinoblastoma associated with primary ectopic intracranial retinoblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1829–1837. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.6.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Draper GJ, Sanders BM, Brownbill PA, et al. Patterns of risk of hereditary retinoblastoma and applications to genetic counselling. Br J Cancer. 1992;66:211–219. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacCarthy A, Birch JM, Draper GJ, et al. Retinoblastoma in Great Britain 1963-2002. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:33–37. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.139618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vogel F. Genetics of retinoblastoma. Hum Genet. 1979;52:1–54. doi: 10.1007/BF00284597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Houdayer C, Gauthier-Villars M, Lauge A, et al. Comprehensive screening for constitutional RB1 mutations by DHPLC and QMPSF. Hum Mutat. 2004;23:193–202. doi: 10.1002/humu.10303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marees T, van Leeuwen FE, Schaapveld M, et al. Risk of third malignancies and death after a second malignancy in retinoblastoma survivors. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2052–2058. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]