Abstract

Batterer intervention programs primarily work with individuals mandated to participate. Commonly, attrition is high and outcomes are modest. Motivational enhancement therapy (MET), most widely studied in the substance abuse field, offers a potentially effective approach to improving self-referral to treatment, program retention, treatment compliance, and posttreatment outcomes among men who batter and who abuse substances. A strategy for using a catalyst variant of MET (a “check-up”) to reach untreated, nonadjudicated perpetrators is described in detail. Unique challenges in evaluating the success of this approach are discussed, including attending to victim safety and determining indicators of increased motivation for change.

Keywords: abusers, check-up, motivational

Over the past decade, several major national surveys reported high rates of violence against women committed by current or former intimate partners. For instance, Tjaden and Thoennes (2000) reported findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey that included more than 8,000 American women 18 years of age or older. Their results indicated that approximately 1.3 million American women are physically assaulted by an intimate partner each year.

Over the past 25 years, a variety of programs have been developed for adult men who are abusive. Many of these programs started as small, nonprofit organizations working closely with battered women’s shelters (see Edleson & Tolman, 1992). Since then, many have evolved into larger organizations or have become part of existing shelter and mental health organizations. Most bring together, on a weekly basis, men who batter with one or two professional group facilitators for periods ranging from 12 to 52 weeks (Austin & Dankwort, 1999).

Dozens of evaluation studies examining the impact of batterer intervention programs (BIPs) have been published, but only a few utilized experimentally controlled designs. Four recent reviews of experimentally controlled BIP evaluations have come to somewhat varying conclusions, with their differences being partially influenced by which studies the authors included in their reviews (see Babcock, Green, & Robie, 2004; Bennett & Williams, 2001; Feder & Wilson, 2005; Gondolf, 2004). These reviewers mostly agree that “(1) batterer intervention programs have modest but positive effects on violence prevention and (2) there is little evidence supporting the effectiveness of one BIP approach over another” (Bennett & Williams, 2001, p. 3).

Two decades ago, 80% to 90% of partner-abusive men entered treatment without a court order (see, e.g., Edleson & Brygger, 1986). Twenty years later, these figures have reversed themselves, with the great majority of those in treatment being court referred (see Gondolf, 2002). In this period, the number of BIP services available and the number of men receiving these services have grown exponentially.

Many men who batter drop out of treatment before completion. Studies comparing program completers to dropouts have found higher rates of nonviolence among completers (see Gondolf, 2004). Daly and Pelowski’s (2000) review of 16 studies of BIPs showed that “dropout rates are consistently high, ranging from 22% to 99%” (p. 138). They found that low motivation among participants was a significant factor in predicting program dropout.

Many men who batter also abuse alcohol and/or other drugs. Holtzworth-Munroe and Stuart (1994) suggest that substance use varies considerably among different types of men who batter, with the most antisocial perpetrators reporting the most substance abuse. Brookoff and colleagues reported that 86% of men who batter used alcohol and 14% used cocaine on the day of the assaults (Brookoff, O’Brien, Cook, Thompson & Williams, 1997). In this same study, family members indicated that 45% of the men had “used drugs or alcohol to the point of intoxication on a daily basis for the past month” (p. 1371). Most recently, Fals-Stewart (2003) reported that on days when men who batter were drinking, the likelihood of violence increased elevenfold.

Limitations in the Provision of Services to Men Who Batter and Who Abuse Substances

In summary, there appears to be a heavy overreliance on the criminal justice system as the route for men entering batterer intervention services. For many, an arrest occurs only after an ongoing period of abusive behavior. Second, attrition from treatment, an indicator of less successful outcomes, is commonly at high levels in most programs. Third, few programs provide interventions for co-occurring battering and substance abuse.

We propose in this article that innovations in substance abuse intervention offer promising models for reaching the many men who will either never come into contact with the criminal justice system or will do so only after a lengthy period of harmful behavior. These innovations hold potential for motivating the abusive individual to voluntarily seek services, enhancing active engagement in the treatment process, reducing attrition, and increasing the percentage of successful outcomes.

In the sections that follow, we first introduce the concept of stages of change. We then discuss a motivational enhancement treatment catalyst intervention (a “checkup”) based on the stages-of-change concepts and suggest how this model might be adapted to motivate men who batter and who abuse substances to seek services. We describe the design of the Men’s Domestic Abuse Check-Up (MDACU) and finally raise several methodological, ethical, and intervention challenges in evaluating a check-up intervention with this population.

The Stages-of-Change Model Is Applicable to Early Intervention

A rapidly growing empirical literature is emerging with a focus on testing interventions for individuals who are contemplating but not yet committed to behavior change. The stages-of-change model (SCM) has greatly influenced the design of these interventions (DiClemente & Prochaska, 1982, 1985; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983).

The SCM proposes that individuals approaching a behavior change move from precontemplation to contemplation, and later to preparation (sometimes called determination or decision making), action, and finally maintenance of change or relapse. Data from cigarette smokers and psychotherapy clients suggest that different psychological and social processes are important at different stages of readiness for change (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983; Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992). Individuals in the precontemplation stage, by definition, will not voluntarily seek treatment because they are not yet considering behavior change. Awareness of the problem or need for change must first increase through some combination of education, social pressure, and self-reevaluation.

Participants in the contemplation stage are weighing the pros and cons of change and need information, feedback, and the opportunity to reflect on their personal dissatisfaction in order to tip the scales in favor of change (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983). An important component of interventions with contemplators is facilitating a self-examination process through the provision of information, fostering disclosure, discussing ambivalent feelings, and comparing the costs and benefits of behavior change. Attempting to jump directly into behavior change efforts during the contemplation stage without fostering the client’s sense of resolve and motivation for change may engage the client’s defenses and be countertherapeutic (Miller & Rollnick, 2002).

Challenges have been made to the empirical basis for the SCM, particularly the suggestion that stages are mutually exclusive and that an individual progresses through the stages in a linear fashion (see Littell & Girvin, 2002). Nonetheless, the concepts remain useful for heuristic purposes in considering the design of interventions tailored to fit well with a client’s motivational level.

Although the SCM has been extensively researched with reference to addictive behaviors, it has received little attention in the field of domestic violence. This literature, almost entirely clinical in nature, suggests the applicability of the SCM to both victims and perpetrators. For example, Brown (1997) suggests that the SCM is applicable to battered women and the considerations they bring to bear in seeking differing levels of support. Murphy and his colleagues (Daniels & Murphy, 1997; Murphy & Baxter, 1997; Murphy & Eckhardt, 2005) argue that current approaches to intervention with men who batter may decrease motivation to change by being ineffectual in reducing the individual’s resistance. They suggest that strategies based on the SCM may be the most promising avenues for improving outcomes with men who batter. Similarly, Begun, Shelley, Strodthoff, and Short (2001) suggest the adoption of the SCM in working with men who batter.

Motivational Enhancement Therapy to Reach Those Early in Readiness to Change

How does one work with a man in an early stage of readiness for change? Conceptually, one promising strategy would be to increase his motivation to seek change-oriented services. Motivational enhancement therapy (MET), a brief intervention modality, has shown promise in promoting treatment entry and enhancing both retention and successful outcomes with a number of hard-to-reach populations. MET is an intervention modality involving an assessment interview and personal feedback about assessment responses. One variant of MET, that is, a check-up, is tailored for the non–treatment seeker, with the intention of eliciting voluntary participation in a “taking stock” experience designed to enhance motivation for change. The check-up either can be offered to those who first have been screened and found to present selected risk factors (e.g., patients seen in a primary care setting and indicating risk for alcohol disorders) or can be freestanding, with a recruitment process that widely publicizes the service and invites inquiry from those who are interested. Structural issues, marketing options, ethical constraints, staff training, and other design challenges associated with in-person, telephone, and computerized adaptations of check-up interventions are discussed in a recent publication by Walker and colleagues (Walker, Roffman, Picciano, & Stephens, 2007).

The employment of a counseling style termed motivational interviewing is of key importance to MET interventions. Motivational interviewing is an empathic, reflective therapeutic style that is intended to elicit the client’s concerns and thoughts while discussing feedback from the initial assessment interview. The general principles of motivational interviewing are (a) express empathy, (b) develop discrepancy, (c) roll with resistance, and (d) support self-efficacy (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). The therapist uses reflective listening to express empathy regarding the client’s ambivalence rather than confront him or her with the need to change. The assumptions are that acceptance facilitates change and that ambivalence is normal among individuals who are contemplating such change.

One important goal of motivational interviewing is to facilitate the client’s awareness of a discrepancy between the client’s present behavior and his or her personal goals in order to motivate change. In motivational interviewing, however, it is important that the client rather than the therapist present the reasons for change. Arguments with the client over the need to change are assumed to be counterproductive, and client resistance becomes a signal to the therapist to change strategies. “Rolling with resistance” refers to reframing a client’s ambivalence, turning the question or problem back to the client, and allowing the client to accept what he or she wants from the interaction. The therapist also works to support the client’s perception that he or she is capable of making changes. Self-efficacy is fostered through the therapist’s optimism and confidence in the client. Clients who are interested are provided a menu of change options, including self-change, support groups, and more formal treatment possibilities.

In a number of controlled trials, MET interventions with substance-abusing populations have shown promise in several respects: reducing substance use among individuals seeking substance abuse treatment (Aubrey, 1998; Baker, Boggs, & Lewin, 2001; Bien, Miller, & Boroughs, 1993; Carey, Purnine, Maisto, & Carey, 2002; Daley, Salloum, Zuckoff, Kirisci, & Thase, 1998; Saunders, Wilkinson, & Phillips, 1995; Stephens et al., 2000; Stotts, Schmitz, Rhoades, & Grabowski, 2001), increasing treatment attendance (Aubrey, 1998; Davis, Baer, Saxon, & Kivlahan, 2003; Swanson, Pantalon, & Cohen, 1999), increasing active participation in the treatment process (Brown & Miller, 1993; Carey et al., 2002; Daley & Zukoff, 1998; Longshore, Grills, & Annon, 1999; Martino, Carroll, O’Malley, & Rounsaville, 2000; Swanson et al., 1999), and reducing attrition (Daley & Zukoff, 1998; Lincourt, Kuettel, & Bombardier, 2002; Martino et al., 2000; Swanson et al., 1999). Not all of the findings of MET trials with substance abusers have been positive, however. Donovan, Rosengren, Downey, Cox, and Sloan (2001) found no effect on treatment entry, retention, or outcome in clients on a waiting list for drug treatment. In two other trials (Booth, Kwiatkowski, Iguchi, Pinto, & John, 1998; Schneider, Casey, & Kohn, 2000), there were no differential effects on treatment entry when MET was compared with an alternative approach. Finally, Miller, Yahne, and Tonigan (2003) reported no effects on drug use outcomes when MET was added to inpatient or outpatient treatment. On balance, however, these findings offer considerable support for continuing study of MET interventions with non–treatment seekers for the purpose of increasing treatment entry, engagement, and retention.

The Check-Up

One early example of the brief check-up MET intervention is the Drinker’s Check-Up (DCU). The DCU was developed to reach and motivate problem drinkers to seek treatment or self-initiate change (Miller & Sovereign, 1989). The intervention was promoted via news media as a free assessment and feedback service for drinkers who wanted to find out whether alcohol was harming them. Recruitment announcements emphasized that the check-up was confidential, not part of any treatment program, and not intended for alcoholics, and that it would be up to the individual to decide what, if anything, to do with the feedback (Miller, Benefield, & Tonigan, 1993).

The initial check-up session involved a structured interview and the completion of questionnaires. A brief neuropsychological assessment was included. The feedback given to the client in the second session, with the clinician employing motivational interviewing skills, was largely normative and risk related in nature. It included a comparison of the amount the client drank per week with the amount an average American drinker consumes per week, the peak blood alcohol content of the client during a typical week of drinking and during more heavy periods, the extent of family risk for alcohol problems, and the severity of problems associated with the client’s alcohol use related to research norms and cut-points.

Interestingly, most of the individuals who sought out the DCU were similar to clients already in treatment on measures of alcohol abuse and related problems (Miller et al., 1993; Miller, Sovereign, & Krege, 1988). This brief intervention resulted in significant decreases in drinking at 12 months and 18 months posttreatment and increased future treatment involvement (Miller et al., 1988, 1993). Participants in a recent computerized version of the DCU reduced their drinking by 50% and also reduced alcohol-related problems. These reductions were sustained a year following the intervention (Hester, Squires, & Delaney, 2005).

Motivational Enhancement Therapy Interventions With Men Who Batter

Existing conceptualizations of the nature of battering fit well with both the SCM and the hypothesis that a brief check-up intervention will be effective with untreated, nonadjudicated men who batter. Defense dynamics attributed by current theory to men who batter hold much in common with characterizations of individuals with addictive disorders, for example, minimizing the severity of consequences, blaming others for causing the behavior, and making excuses for one’s actions. Because the DCU ostensibly reduced resistance in its participants, a similar MET intervention may hold promise with adults who are engaging in battering behaviors. Moreover, resistance reduction strategies that are central to motivational interviewing appear to be particularly pertinent in enhancing motivation for change in individuals whose difficulties with power and control manifest as abusive behaviors. Anecdotal evidence from the domestic violence clinical literature points to episodes of remorse (i.e., motivational conflict or ambivalence) among men who batter that suggest compatibility with theory pertaining to stages of change.

The check-up is publicized as being confidential, brief, and respectful of the participant’s autonomy in determining his relative level of risk, his goals, and his readiness to change. These qualities of the intervention may enhance its cultural relevance for men of color, many of whom are members of communities that give high priority to the influences of extended kin and the collective (Williams, 1998). African American men, in particular, who are disproportionately represented in the court system and often feel targeted by correctional systems (Gondolf & Williams, 2001; Stone, 1999), might welcome the nonconfrontational style of motivational interviewing.

Other factors suggest that MET is well suited as an approach for motivating change among untreated, nonadjudicated men who batter and who abuse substances. Alcoholic husbands who engage in battering are more likely to have interaction styles that are defensive and confrontational with their partners compared with nonviolent alcoholic husbands (Murphy & O’Farrell, 1997). MET is designed to work with individuals with these characteristics and has demonstrated greater efficacy with such individuals. For example, findings from a large-scale alcoholism intervention trial (Project MATCH) revealed that MET was more efficacious for reducing alcohol use with patients high in anger (Project MATCH Research Group, 1997) and that therapist directiveness mediated this relationship (Karno & Longabaugh, 2004). Taken together, these findings suggest that MET may be particularly suited for precontemplative and contemplative men engaging in both battering and substance abuse.

The Men’s Domestic Abuse Check-Up (MDACU)

The MDACU is a federally funded telephone-delivered intervention trial currently being conducted by the University of Washington and University of Minnesota Schools of Social Work. Adapted from the DCU, the MDACU was developed to engage and motivate substance-abusing male batterers into action. It is designed for men who are ambivalent about their behaviors and who are in the precontemplation or contemplation stages of change.

MDACU’s major goal is to motivate participants to self-refer into domestic violence and/or substance abuse treatment. Eligibility criteria include being a man 18 years or older, engaging in domestic abuse and use of alcohol or drugs, and neither in counseling nor undergoing adjudication.

Eligible men are randomly assigned to receive a telephone-delivered individual feedback counseling session (MET condition) or mailed educational materials on domestic violence and substance abuse (education condition). With guidance from a counselor, MDACU offers the MET participant an opportunity to take stock of his behaviors and think through his options. Participants in the education condition are also invited to receive the individual feedback counseling session following their final follow-up assessment interviews.

Reaching Men in the Community

Reaching a community sample of substance-abusing men who batter is a major challenge. An advertising agency and a group of consultants collaborated with us in designing a recruitment plan. In addition to consultants who are domestic violence specialists with experience working with men who batter and with battered women, men who have battered in the past and who have successfully completed a BIP were recruited to serve in focus groups and respond to various draft iterations of the project’s marketing products. Reports concerning the effectiveness of previous social marketing campaigns designed to recruit men engaging in domestic violence were also reviewed.

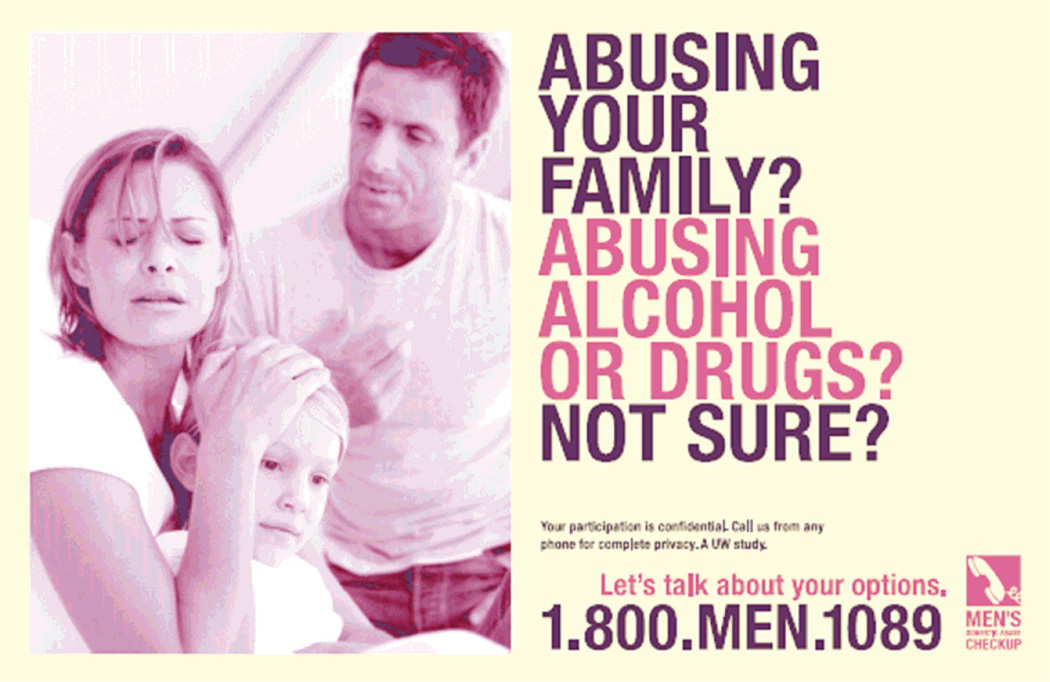

Based on earlier marketing research, feedback from the consultants, and the tenets of SCM, a marketing campaign was designed to be nonjudgmental and engaging and to appeal to men who are in the precontemplation and contemplation stages of change. The marketing strategies involve a variety of images and text that are relevant to individuals from diverse socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds. In advertisements, images of diverse individuals are linked with hypothetical statements that reflect the thinking and experiences of men who are engaging in battering and concerned about their behaviors. Newspaper display ads include three images and messages: (a) a close-up photo of a child, and the text: “Ever wonder how to make the fear in their eyes disappear?”; (b) a photo of a family in which the father appears to be upset with the mother and child, and the text: “Abusing your family, abusing alcohol or drugs, not sure?”; (c) the image of a man forcefully grabbing his partner, and the text: “She’s afraid of you. Does it have to be that way?” All ads include a privacy statement, the project’s logo, the toll-free phone number, and a message: “Let’s talk about your options.” Figure 1 is an example of the marketing materials developed for this project.

Figure 1.

Example of Marketing Material Developed for the Men’s Domestic Abuse Check-Up

Reprinted with permission of Innovative Programs Research Group/University of Washington.

Recruitment efforts include generating coverage in the form of feature or news stories in the mainstream press, radio, and television; display ads in daily and weekly newspapers and metro bus lines; radio ads; and project flyers distributed widely in health, social services, and criminal justice venues. Monitoring the effectiveness of each recruitment strategy is facilitating ongoing modifications in the messages and/or channels used.

Increasing the Check-Up’s Desirability

Inherent in the check-up variant of MET are several attributes likely to increase the desirability of the experience in the eyes of the potential participant. The intervention is brief (i.e., two sessions), it is described as a “taking stock” experience rather than counseling to affect change, and it is emphasized that it is up to the participant to decide how to make use of the feedback. Delivering the MET intervention by telephone and permitting participants to enroll confidentially or anonymously are two additional elements used to lower barriers to reaching the target population.

Providing Personalized Feedback

Personalized feedback provided during MET sessions is structured using a personalized feedback report (PFR). In the MDACU, an individualized PFR is generated for each man from information obtained in his screening and baseline assessment interviews. The PFR is then mailed to the participant, either to an address he provides or to a post office box if he prefers to remain anonymous. Several days later, the therapist and client meet by phone to review the PFR in the MET session. Once the session is completed, the man is provided with a handout, “Understanding Your Personal Feedback Report,” that offers detailed explanations of the content of the PFR.

The content of the PFR for the MDACU was modeled after PFRs that have been designed to address other behaviors including alcohol use (Miller & Sovereign, 1989), marijuana use (Walker, Roffman, Stephens, Berghuis, & Kim, 2006), and risky sexual behavior (Picciano, Roffman, Kalichman, Rutledge, & Berghuis, 2001). The PFR is printed as a small booklet divided into two sections, with the first section devoted to relationship behavior (i.e., domestic violence) and the second section presenting feedback regarding alcohol and other substance use.

Both sections of the PFR include four common components: review of relevant behavior, normative feedback, review of consequences of behavior, and risk factors. Feedback regarding the participant’s behaviors in the first section presents specific abusive behaviors that the client has reported (e.g., “using threats to make your partner have oral or anal sex” and “beating your partner up”). For alcohol and other substance use, the review of behavior lists the frequency and quantity of the participant’s reported alcohol consumption and the frequency of the primary substance used other than alcohol, if any.

Normative feedback, a second common component, is integrated with the summary of behavior. A number of studies have documented that people tend to overestimate the frequency and prevalence of a wide range of behaviors, including alcohol use (Borsari & Carey, 2003), other substance use and risky sex behavior (Kilmer, et al., 2006; Martens et al., 2006), tobacco use (Linkenbach & Perkins, 2003), and gambling (Larimer & Neighbors, 2003). These misperceptions have been suggested to be a causal factor in perpetuating problematic behavior. Moreover, individuals who engage in problematic behaviors tend to have the largest misperceptions. Consequently, many MET-based interventions provide actual behavioral norms designed to reduce the misperceived normality of a given behavior and to put the participant’s own behavior into perspective. Normative feedback has been shown to be effective as a stand-alone intervention (e.g., Neighbors, Larimer, & Lewis, 2004) but has been more commonly included as a component in MET-based interventions. The majority of the evidence supporting this approach has been established in adolescent and college populations, but the approach has also been incorporated, at least for alcohol, in health care and treatment settings (Fleming, Barry, Manwell, Johnson, & London, 1997; Project MATCH Research Group, 1997) as well as in the general population (Cunningham, Koski-Jannes, Wild, & Cordingley, 2002). In the PFR, participants are provided feedback regarding their perceptions of the prevalence of specific behaviors that they have reported engaging in themselves and the actual prevalence rates estimated in the population. Thus, a participant who reports having thrown something at his partner may estimate that 45% of other men have also thrown things at their partners. In the MET session, the therapist might present this information in the following way, “You reported having thrown something at your partner. You also said you thought about 45% of other men have thrown something at their partners at one time or another. Recent national estimates of the prevalence of this behavior suggest that only about 12% of men have thrown something at their partners. What do you make of that?” This information is intended to help participants understand that abusive behaviors are not as common as they might think and that their own behavior is atypical. Similar discussions center on the prevalence of alcohol and other substances in the second section of the PFR.

The third and fourth components of the PFR involve reviewing the consequences of behavior and risk factors. Again, this content is based on the participant’s own reports. Examples of domestic abuse consequences include “going to a hospital or doctor due to a fight with your partner” and “losing respect for yourself.” Consequences of domestic abuse to children are also highlighted. Examples of consequences due to alcohol and other substances include “missing work or school” and “problems with other people such as family members, friends, or people at work.” In both sections, risk factors focus on family history. Tolerance is also discussed as a risk factor for alcohol.

Mailed Educational Materials Condition

Participants randomized to the education condition receive a visually friendly informational brochure on domestic violence and substance abuse. The brochure includes definitions of domestic violence and substance abuse; incidence and prevalence data; and their impact on the individual, family, and society. With reference to domestic violence, the content includes legal consequences and penalties, types of adverse impact resulting from intimate partner violence, and special circumstances faced by immigrants. The substance abuse section clarifies the distinction between substance abuse and dependence, discusses substance abuse and driving, considers the impact on physical and mental health, and identifies its cost to society.

Screening, Assessment, and Follow-Up

Participants complete four assessment phone calls: two pretreatment screening interviews and two follow-up calls after receiving one of the two interventions, either the feedback session or mailed educational materials. The screening calls, held during the 1st week, are conducted by assessors and are designed to (a) engage the caller in a conversation about his situation, (b) fully inform prospective participants about the project, and (c) determine the caller’s eligibility and interest in participating. During the participant’s 2nd week, counselors conduct the baseline assessment, a structured interview designed to (a) collect domestic violence and substance abuse data for a PFR that guides the MET session, (b) collect baseline data to measure change from program entry to follow-up, and (c) begin to establish rapport between the counselor and participant.

At 1 week and again at 30 days after receipt of either condition (MET or education), assessors conduct structured follow-up assessments to measure any change in outcomes and obtain participants’ feedback on the overall project.

Evaluating the MDACU

Evaluating a MET catalyst check-up with men who batter and who abuse substances and who are neither in treatment nor being adjudicated presents unique methodological and treatment challenges. We conclude this article by discussing several ethical, methodological, and intervention design issues we confronted as we designed a MET intervention with this population. The study will enroll more than 100 men in a randomized controlled trial. Two issues confronted in designing the evaluation were (a) considerations that must be given concerning the safety of the victim or victims and (b) identifying appropriate primary and intermediate outcomes for this kind of intervention. We discuss each below.

Participant’s Rights and Victim Safety

Intervention research with men who batter presents complex issues with reference to the participant’s rights and the importance of attending to the partner’s safety. The challenges in mounting a MET check-up are greater due to the inclusion of an anonymity option and delivering services by telephone. In addition to attending to adult and child victim safety, a project such as this needs to fulfill ethical responsibilities to the participant by providing him with full information concerning mandated reporting requirements.

During the consent process, prospective participants are informed of the exceptions to their confidentiality while enrolled in the study: (a) Suspected child abuse and neglect must be reported to Child Protective Services, and (b) a report will be made to a mental health professional (i.e., therapist) or other authority if a participant indicates he is planning to hurt or kill himself or another person.

An inherent risk to the victim, not unlike risks faced by other services for abusive men, is the possibility that the man will misrepresent to his partner or spouse the nature of the intervention and his level of involvement in it. For example, because confidentiality is assured, a spouse cannot contact project staff to confirm her partner’s enrollment. Also, the spouse or partner may be at risk if the participant misrepresents his involvement in the check-up as receiving treatment.

Successful Outcomes

The primary intended outcome for the MET check-up intervention is self-referral to treatment. Various intermediate treatment-seeking actions, including calling an agency for an appointment, requesting that printed information be sent, going to an agency to inquire, and applying for acceptance in a treatment program, all can be considered as indicators of enhanced motivation.

In this study, we have adopted another intermediate behavioral outcome indicative of enhanced readiness for change. We offer men in both the MET and education conditions the opportunity to attend an optional in-person session on learning about and considering counseling options in the community. Participants are told that this session focuses on community treatment resources (i.e., their treatment components and philosophies, duration, and costs). We hypothesize that more men in the MET condition will attend these sessions, and we expect that attending this session will increase the likelihood that men subsequently will enroll in domestic violence and substance abuse services in the community.

Interim Findings Concerning Feasibility

Recruitment over approximately a 14-month period is intended to enroll 124 participants at the rate of 2 per week. At the halfway point, recruitment was on schedule, with 73 participants having joined the study. Participants have a mean age of 44 (range = 21–67, SD = 10.8), and 73% are White non-Hispanic. Thus far, treatment completion (i.e., assessment and feedback session) and participation in the 1-week and 30-day follow-up assessment interviews have been quite positive at 85%, 86%, and 83%, respectively. Of the various publicity mechanisms being used to recruit, radio advertisements appear to be of greatest effectiveness.

Conclusion

Evaluations of programs for men who batter show modest positive effects, but there is a dire need to develop empirically tested methods for motivating more men to seek treatment earlier and to stay the course of intervention. Motivational strategies have been proven to be effective with other hard-to-reach populations and conceptually offer promise for similar success with men who batter and who abuse substances.

We have adapted and are evaluating a brief MET catalyst (i.e., a check-up) for men who batter, abuse substances, and have neither been involved in domestic abuse legal actions against them nor enrolled in a BIP. There are several possible benefits to such an approach. First and foremost, if participation leads to an increased readiness to change, that readiness may be manifested by earlier and voluntary enrollment in treatment. A consequence of early voluntary enrollment is likely to be the prevention of injury and abuse that otherwise would have continued until arrest and adjudication in the criminal justice system. Other potential benefits include more active client engagement in program activities, higher rates of program completion, and greater intervention efficacy in terms of decreasing or ending violent behaviors and abusive use of alcohol or drugs. Results of our and others’ studies will indicate if this approach will be a fruitful endeavor aimed at enhancing intervention with substance-abusing men who batter living in our communities.

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1 RO1 DA017873.

Biographies

Roger A. Roffman is a professor of social work at the University of Washington, where he also serves as director of the Innovative Programs Research Group.

Jeffrey L. Edleson is a professor of social work at the University of Minnesota, where he also serves as director of the Minnesota Center Against Violence and Abuse.

Clayton Neighbors is an associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Washington.

Lyungai Mbilinyi is a research assistant professor on the faculty of the University of Washington School of Social Work. She is project director of the Men’s Domestic Abuse Check-Up.

Denise Walker is a research assistant professor on the faculty of the University of Washington School of Social Work. She is clinical director of the school’s Innovative Programs Research Group.

Contributor Information

Roger A. Roffman, University of Washington

Jeffrey L. Edleson, University of Minnesota

Clayton Neighbors, University of Washington.

Lyungai Mbilinyi, University of Washington.

Denise Walker, University of Washington.

References

- Aubrey LL. Motivational interviewing with adolescents presenting for outpatient substance abuse treatment (Doctoral dissertation, University of New Mexico) Dissertation Abstracts International. 1998;59(3):1357. [Google Scholar]

- Austin JB, Dankwort J. Standards for batterer intervention programs: A review and analysis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14:152–168. [Google Scholar]

- Babcock JC, Green CE, Robie C. Does batterers’ treatment work? A meta-analytic review of domestic violence treatment. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;23:1023–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2002.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker A, Boggs TG, Lewin TJ. Randomized controlled trial of brief cognitive-behavioral interventions among regular users of amphetamine. Addiction. 2001;96:1279–1287. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96912797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begun AL, Shelley G, Strodthoff T, Short L. Adopting a stages of change approach for individuals who are violent with their intimate partners. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma. 2001;5:105–127. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett L, Williams OJ. Controversies and recent studies of batterer intervention effectiveness. Harrisburg, PA: National Electronic Network on Violence Against Women (VAWnet, PCADV/ NRCDV); 2001. [Retrieved June 21, 2007]. from http://www.vawnet.org. [Google Scholar]

- Bien TH, Miller WR, Boroughs JM. Motivational interviewing with alcohol outpatients. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 1993;21:347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Kwiatkowski C, Iguchi MY, Pinto F, John D. Facilitating treatment entry among out-of-treatment injection drug users. Public Health Reports. 1998;113(Suppl. 1):116–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookoff D, O’Brien KK, Cook CS, Thompson TD, Williams C. Characteristics of participants in domestic violence: Assessment at the scene of domestic assault. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;277:1369–1373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J. Working toward freedom from violence: The process of change in battered women. Violence Against Women. 1997;3:5–26. doi: 10.1177/1077801297003001002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JM, Miller WR. Impact of motivational interviewing on participation and outcome in residential alcohol treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1993;7:211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Purnine DM, Maisto SA, Carey MP. Correlates of stages of change for substance abuse among psychiatric outpatients. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16:283–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JA, Koski-Jannes A, Wild TC, Cordingley K. Treating alcohol problems with self-help materials: A population study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:649–654. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley DC, Salloum IM, Zuckoff A, Kirisci L, Thase ME. Increasing treatment adherence among outpatients with depression and cocaine dependence: Results of a pilot study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155:1611–1613. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley DC, Zuckoff A. Improving compliance with the initial outpatient session among discharged inpatient dual diagnosis clients. Social Work. 1998;43:470–473. doi: 10.1093/sw/43.5.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly J, Pelowski S. Predictors of dropout among men who batter: A review of studies with implications for research and practice. Violence and Victims. 2000;15:137–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels JW, Murphy CM. Stages and processes of change in batterers’ treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 1997;4:123–145. [Google Scholar]

- Davis TM, Baer JS, Saxon AJ, Kivlahan DR. Brief motivational feedback improves post-incarceration treatment contact among veterans with substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;69:197–203. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00317-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO. Self-change and therapy change of smoking behavior: A comparison of processes of change in cessation and maintenance. Addictive Behaviors. 1982;7:133–142. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(82)90038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO. Processes and stages of self-change: Coping and competence in smoking behavior change. In: Shiffman S, Wills TA, editors. Coping and substance use. New York: Academic Press; 1985. pp. 319–343. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan DM, Rosengren DB, Downey L, Cox GC, Sloan KL. Attrition prevention with individuals awaiting publicly funded drug treatment. Addiction. 2001;96:1149–1160. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96811498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edleson JL, Brygger MP. Gender differences in self-reporting of battering incidents: The impact of treatment upon report reliability one year later. Family Relations. 1986;35:377–382. [Google Scholar]

- Edleson JL, Tolman RM. Intervention for men who batter. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W. The occurrence of partner physical aggression on days of alcohol consumption: A longitudinal diary study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:41–52. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.71.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder L, Wilson DB. A meta-analytic review of court-mandated batterer intervention programs: Can courts affect abusers’ behavior? Journal of Experimental Criminology. 2005;1:239–262. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming MF, Barry KL, Manwell LB, Johnson K, London R. Brief physician advice for problem alcohol drinkers: A randomized controlled trial in community-based primary care practices. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;277:1039–1045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gondolf EW. Batterer intervention systems: Issues, outcomes, and recommendations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gondolf EW. Evaluating batterer counseling programs. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;9:605–631. [Google Scholar]

- Gondolf EW, Williams OJ. Culturally focused batterer counseling for African American men. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 2001;2:283–295. [Google Scholar]

- Hester R, Squires D, Delaney H. The Drinker’s Check-Up: 12-month outcomes of a controlled clinical trial of a stand-alone software program for problem drinkers. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Stuart GL. Typologies of male batterers: Three subtypes and the differences among them. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:476–497. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karno MP, Longabaugh R. What do we know? Process analysis and the search for a better understanding of Project MATCH’s anger-by-treatment matching effect. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:501–512. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmer JR, Walker DD, Lee CM, Palmer RS, Mallett KA, Fabiano P, et al. Misperceptions of college student marijuana use: Implications for prevention. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:277–281. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Neighbors C. Normative misperception and the impact of descriptive and injunctive norms on college student gambling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:235–243. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincourt P, Kuettel TJ, Bombardier CH. Motivational interviewing in a group setting with mandated clients: A pilot study. Addictive Behaviors. 2002;27:381–391. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linkenbach JW, Perkins HW. MOST of us are tobacco free: An eight-month social norms campaign reducing youth initiation of smoking in Montana. In: Perkins HW, editor. The social norms approach to preventing school and college age substance abuse: A handbook for educators, counselors, and clinicians. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. pp. 224–234. [Google Scholar]

- Littell JH, Girvin H. Stages of change: A critique. Behavior Modification. 2002;26:223–273. doi: 10.1177/0145445502026002006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longshore D, Grills C, Annon K. Effects of a culturally congruent intervention on cognitive factors related to drug use recovery. Substance Use and Misuse. 1999;34:1223–1241. doi: 10.3109/10826089909039406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Page JC, Mowry ES, Damann KM, Taylor KK, Cimini MD. Differences between actual and perceived student norms: An examination of alcohol use, drug use, and sexual behavior. Journal of American College Health. 2006;54:295–300. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.5.295-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Carroll KM, O’Malley SS, Rounsaville BJ. Motivational interviewing with psychiatrically ill substance abusing patients. American Journal of Addictions. 2000;9:88–91. doi: 10.1080/10550490050172263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Benefield GS, Tonigan GS. Enhancing motivation for change in problem drinking: A controlled comparison of two therapist styles. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:455–461. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Sovereign RG. The check-up: A model for early intervention in addictive behaviors. In: Loberg T, Miller WR, Nathan PE, Marlatt GA, editors. Addictive behaviors: Prevention and early intervention. Amsterdam: Swets & Zeitlinger; 1989. pp. 219–231. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Sovereign RG, Krege B. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers: II. The Drinker’s Check-Up as a preventive intervention. Behavioural Psychotherapy. 1988;16:251–268. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Tonigan SJ. Motivational interviewing in drug abuse services: A randomized trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:754–763. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, Baxter VA. Motivating batterers to change in the treatment context. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1997;12:607–619. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, Eckhardt CI. Treating the abusive partner: An individualized cognitive-behavioral approach. New York: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, O’Farrell TJ. Couple communication patterns of maritally aggressive and nonaggressive male alcoholics. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:83–90. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: Efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciano JF, Roffman RA, Kalichman SC, Rutledge SE, Berghuis JP. A telephone based brief intervention using motivational enhancement to facilitate HIV risk reduction among MSM: A pilot study. AIDS and Behavior. 2001;5:251–262. [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1983;51:390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC. In search of how people change. American Psychologist. 1992;47:1102–1114. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.9.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. Project MATCH secondary a priori hypotheses. Addiction. 1997;92:1671–1698. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders B, Wilkinson C, Phillips M. The impact of a brief motivational intervention with opiate users attending a methadone programme. Addiction. 1995;90:415–424. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.90341510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider RJ, Casey J, Kohn R. Motivational versus confrontational interviewing: A comparison of substance abuse assessment practices at employee assistance programs. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2000;27:60–74. doi: 10.1007/BF02287804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Roffman RA, Williams CD, Adams SE, Burke R, Campbell A. The marijuana check-up outcomes; Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy; New Orleans, LA. 2000. Nov, [Google Scholar]

- Stone C. Race, crime, and the administration of justice: A summary of the available facts. National Institute of Justice Journal. 1999;239:26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Stotts AM, Schmitz JM, Rhoades HM, Grabowski J. Motivational interviewing with cocaine-dependent patients: A pilot study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:858–862. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.5.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson AJ, Pantalon MV, Cohen KR. Motivational interviewing and treatment adherence among psychiatric and dually-diagnosed patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1999;187:630–635. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Full report of the prevalence, incidence, and consequences of violence against women. Washington, DC: Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Walker D, Roffman R, Stephens R, Berghuis J, Kim W. A brief motivational enhancement intervention for adolescent marijuana users: A preliminary randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:628–632. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DD, Roffman RA, Picciano J, Stephens RS. The check-up: In-person, computerized, and telephone adaptations of motivational enhancement treatment to elicit voluntary participation by the contemplator. [Retrieved June 21, 2007];Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2007 2(2) doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-2-2. from http://www.substanceabusepolicy.com/content/2/1/2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams O. Healing and confronting the African American male who batters. In: Carillo R, Tello J, editors. Family violence and men of color: Healing the wounded male spirit. New York: Springer; 1998. pp. 74–94. [Google Scholar]