Abstract

The use of tandem mass spectrometry to identify and characterize sites of protein adenosine diphosphate (ADP) ribosylation will be reviewed. Specifically, we will focus on data acquisition schemes and fragmentation techniques that provide peptide sequence and modification site information. Also discussed are uses of synthetic standards to aid characterization, and an enzymatic method that converts ADP-ribosylated peptides into ribosyl mono phosphorylated peptides making identification amenable to traditional phosphopeptide characterization methods. Finally the potential uses of these techniques to characterize poly ADP-ribosylation sites, and inherent challenges, are addressed.

Keywords: ADP-ribosylated peptide, mono ADP-ribosylation, poly ADP-ribosylation, fragmentation pattern, tandem mass spectrometry

1. Biological Significance/Diversity of Modification

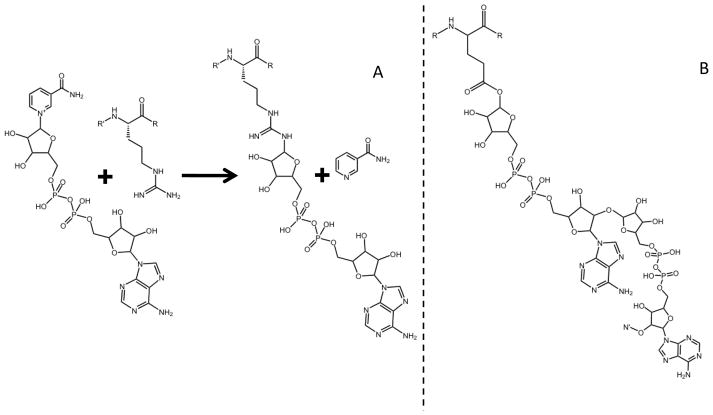

ADP-ribosylation is one of many biologically important, but under studied protein post-translational modifications (PTMs). Cellular processes associated with mono ADP-ribosylation of proteins range from cell signaling and DNA repair to bacterial pathogenesis. ADP-ribosyl transferases (ADPRTs) catalyze the transfer of ADP-ribose from β-NAD+ to target proteins (Figure 1A), commonly at arginine, glutamine, and asparagine residues [1]. Members of the ADPRT family modify a diverse set of target proteins but share little sequence homology. For example, the mammalian ADP-ribosyltransferase, ART-1, modifies defensin-1 which ultimately blocks the antimicrobial and cytotoxic effects of the defensin HNP-1 [2]. From the opposite perspective of bacterial infection of mammalian hosts, bacterial ADPRTs have been implicated in pathogenicity through the inactivation of host proteins ranging from cytoskeletal to G proteins (e.g. Vibrio cholerae, Bordetella pertussis and Streptococcus pyogenes [1]).

Figure 1.

A) Transfer of ADP-ribose from β-NAD+ to arginine is catalyzed by ADP-ribosyl transferases and B) Poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP-1) catalyzes ADP-ribosylation and subsequent ADP-ribose polymers (N′).

An additional role of ADP-ribosyl protein modification, in the form of a branched polymer, serves as a recruitment signal for nuclear repair proteins. In response to cellular stress or injury, ADP-ribose protein modifications are produced by poly ADP-ribose polymerases (PARPs) that catalyze a similar reaction as ADPRTs. However, after a target protein is initially ADP-ribosylated, PARPs add additional ADP ribose groups to the first ADP-ribose creating heterogeneous branched chains of ADP-ribose polymers (Figure 1B). Poly ADP-ribosylation is known as a “short-term regulator” as the modification is rapidly cleaved by poly-(ADP-ribose)-glycohydrolase (PARG) [3]. The modification alone is very large and carries many negative charges. The latter fact strongly suggests that PARP modifications on target proteins sterically disrupt protein function, protein-protein interactions, as well as protein-DNA interactions [4]. The most common PARP, PARP-1, recognizes DNA single strand breaks (SSBs) and sequesters repair proteins. Although the primary target of PARP-1 is PARP-1 itself, this enzyme also modifies various nuclear proteins involved in DNA synthesis, transcription and modulation of chromatin structure [4]. In normal cells PARP-1 activity is low; however, PARP-activity increases in cells that have been exposed to DNA-damaging agents like ionizing radiation [5]. As a result, PARP inhibitors have been developed as an adjuvant to existing cancer chemo-therapeutic regimens that stimulate DNA damage [6–7].

Despite numerous molecular assays demonstrating the importance of ADP-ribosylation, the exact site of ADP-ribosylation and number of modification targets remain unknown for most mono ADPRTs and PARPs. Although not as commonly studied as phosphorylation or acetylation, over the past decade the use of tandem mass spectrometry for identifying ADP-ribosylation sites has increased. While structurally similar to glycation and glycoslation, processes where carbohydrate moieties covalently modify amino acid residues, the addition of ADP-ribose to a protein is slightly more complex due to the labile pyrophosphate and adenine moieties. One potential reason for the lag of site identifications is the interference of ADP-ribose fragment ions that are present in collision induced dissociation (CID) peptide tandem mass spectra.

A common analytical method to identify sites and protein targets of PTMs in complex biological samples uses high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled to electrospray ionization (ESI) tandem mass spectrometry (LCMS2) [8–9]. In this analysis CID is typically employed as the main fragmentation method during data-dependent ion selection based LC-MS2 acquisitions because instrumental duty cycle is high, allowing for a large number of peptides to be fragmented in an automated fashion leading to high sequence coverage of identified proteins. Typically, using CID to sequence unmodified peptides is relatively straightforward as the majority of fragment ions primarily result from predicted peptide fragmentation pathways [10]. However, the presence of a PTM on a peptide can redirect CID fragmentation patterns such that sequence may not be assigned using a traditional database search [11]. One of the first papers displaying the tandem mass spectrum of an ADP-ribosylated peptide, Margarit et al. (2006) [12], demonstrated that CID of an ADP-ribosylated peptide did not result in “typical” peptide fragmentation, complicating facile sequence interpretation. Subsequently, several groups have investigated a range of fragmentation techniques and acquisition schemes in the attempt to characterize ADP-ribosylated peptide fragmentation and increase throughput of modified peptide identifications.

2. Preliminary Work

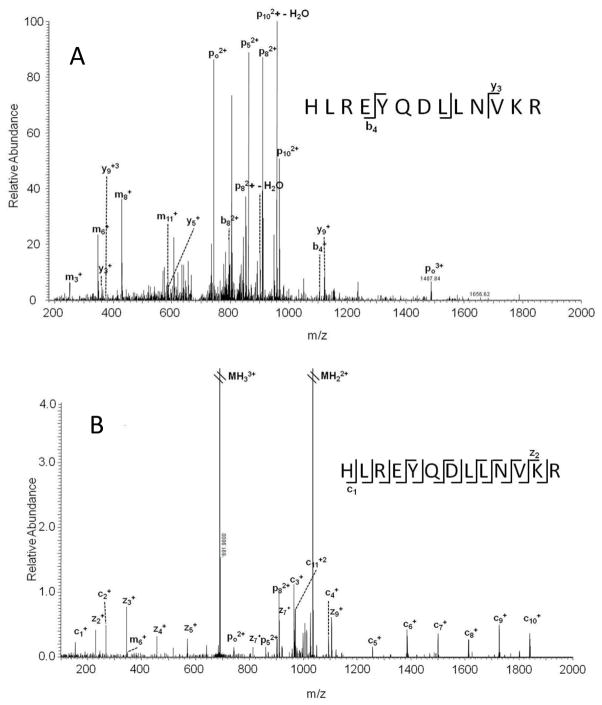

It has been demonstrated that the presence of ADP-ribose on a peptide influences the CID and infrared multiphoton dissociation (IRMPD) fragmentation patterns to the extent that ADP-ribosylation can obstruct peptide sequencing [13–15]. With CID, the major sites of fragmentation occur at the pyrophosphate bond and terminal adenine of the ADP-ribose backbone (Figure 2A). Other fragmentation events along the ADP-ribose backbone are often seen at lower intensities, and in general few b or y ions are observed. In contrast, electron capture dissociation (ECD) or electron transfer dissociation (ETD) of the same peptide will generate fragment ions that primarily correspond to peptide backbone fragmentation and allow for peptide sequencing (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Representative tandem mass spectra of ADP-ribosylated peptides using A) CID or B) ECD fragmentation [16].

Two main techniques have been suggested for the identification of mono ADP-ribosylated peptides with tandem mass spectrometry. Both are based on the observation that ADP-ribose, opposed to smaller and less labile modifications such as methylation oxidation and acetylation, influences the fragmentation pattern of ADP-ribosylated peptides to the extent that traditional database searches specifying an optional 541 Da (the net mass addition to a peptide from ADP-ribosylation) will not adequately identify all modified peptides. The first method [13] described for characterization of ADP-ribosylated peptides is referred to as the “marker ion” approach. In the marker ion approach, peptide ions detected in a first pass LCMS2 experiment that display putative ADP-ribose marker ions are targeted for ECD fragmentation in a second LCMS2 experiment. To detect the presence of ADP-ribose specific marker ions in thousands of tandem mass spectra from the automated LCMS2 experiment, Hengel et al. developed PERL scripts that searched CID and IRMPD peptide tandem mass spectra for the presence of specified diagnostic ions. The precursor masses of the tandem mass spectra of putative ADP-ribosylated peptides are then targeted in a second LCMS2 experiment using ECD and an inclusion list. The inclusion list prioritizes data-dependent precursor ion selection from a specified list of ions for ECD fragmentation. However, if an ion from the list is not detected in the precursor ion scan then the normal data-dependent ion selection process proceeds until the next MS scan. The ECD data are searched for ADP-ribosylated peptides using a traditional proteomic search algorithm specifying the addition of 541 to arginine or other modified amino acids. The large ADP-ribose moiety remains covalently attached to the peptide during ECD fragmentation, a common feature of electron based fragmentation methods. While this method has the disadvantage of requiring multiple LCMS2 acquisitions, the marker ion strategy has the advantage that select diagnostic ions are not specific to arginine fragmentation and can be used with any ADPRT independent of amino acid specificity. Additionally, the marker ion strategy utilizes the high duty cycle of a linear ion trap together with highly efficient CID to increase precursor ion sampling and dynamic range. If users had access to instrument control language the two LCMS2 experiments could be combined into one, by triggering additional tandem MS events based on the observation of an ADP-ribose fragment ion. However instrument manufactures currently limit user access to underlying instrument control code.

The second method proposed and implemented by Osago et al. [14] exploits the observation that ADP-ribosylated arginine residues fragment to form ornithine upon CID or in-source dissociation. The intact peptide containing ornithine in the tandem mass spectrum is then subjected to MS3 analysis for peptide sequencing, and the data is searched with a −42 Da optional modification on arginine, generating arginine to ornithine peptide identifications. The main benefit of this method is that data are acquired from a single LCMSn analysis, however, it is limited to amino acids that form ornithine upon fragmentation i.e. arginine. In the cases of bacterial ADPRTs and PARPs that target amino acids other than arginine, such as glutamic acid, a different MS method for detection and identification would be required.

Shortly after these initial studies were reported, Zee et al. suggested use of ETD to sequence an ADP-ribosylated peptides [15]. ETD has the advantage over ECD in that it is becoming more readily available in a wider range of mass analyzers than ECD that requires an ion cyclotron resonance (ICR) cell mass analyzer for implementation. Further, ETD may prove to be more useful for biologists as it has a sensitivity advantage occurring in ion trap mass analyzers over ECD where ion transfer to the ICR cell is often inefficient. However, it is important to note that the same general trend is seen with both fragmentation methods: CID produces ions from events primarily along the ADP-ribose backbone while electron specific methods produce ions that are from peptide backbone fragmentation.

Despite the need for electron based fragmentation methods, or MS3, for complete characterization of ADP-ribosylated peptides, searching CID data against a database of protein sequences with a 541 mass adduct on amino acids of interest is also a reasonable first approach for the average laboratory without access to ECD or ETD. For example, in limited cases where b and y ions are present (although at much lower intensity than ADP-ribose fragment ions) in tandem mass spectra, select peptide sequences have been identified as ADP-ribosylated from the CID tandem mass spectrum alone [16–17]. However, lack of sequence specific ions may increase the complexity of data analysis, and limit the ability to assign the specific amino acid that is modified. Additionally, the large range of potential peptide sequences, length, and basicity found in biological samples warrant further fundamental studies on tandem mass spectrometry of ADP-ribosylated peptides. It is also worth noting that Oetjen et al. observed a decrease in MS signal of ADP-ribosylated peptide after processing the sample with acid present, and suggested that exposure of ADP-ribosylated peptides to acid should be minimized while preparing samples to prevent loss of the modification [17]. While no reports are out as yet, the complimentary top-down [18] and bottom up analysis of large ADP-ribosylated peptides and small proteins is of interest as it will provide a direct means to catalog modification sites. Increasing the “library” of known ADP-ribosylated peptide/protein tandem mass spectra would be a large asset for designing automated ADP-ribosylation analyses, both for acquisition methods and database searching tools.

3. Nomenclature

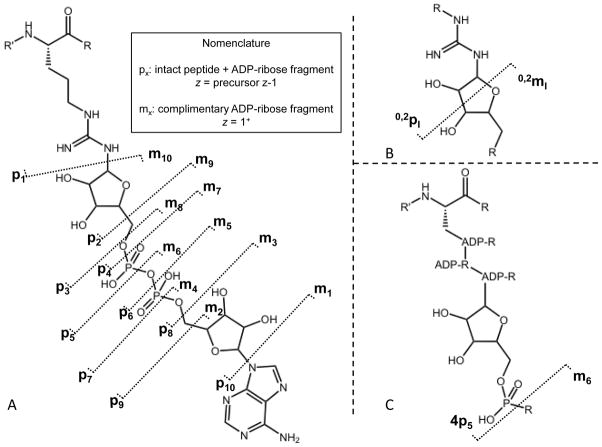

Due to the complex nature of ADP-ribosylated peptide fragments, where fragment ions potentially consist of the intact peptide with or without a range of ADP-ribose fragments, ADP-ribose fragments alone, or predicted peptide backbone fragments, a systematic nomenclature was suggested for spectral annotation [13]. The proposed scheme by Hengel et al. is independent of amino acid linker and allows for annotation of both free ADP-ribose fragment ions and ADP-ribose containing peptide counterparts. The scheme accounts for fragmentation at the ten single bonds on the ADP-ribose backbone with either a lower-case letter m indicating a peptide-free modification fragment ion, or p indicating an intact peptide plus ADP-ribose fragment covalently attached. Each of the letters is followed by a subscript number that indicates the site of fragmentation (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

A) Proposed ADP-ribosylated peptide fragment ion nomenclature as suggested by Hengel et al., B) cross ring fragmentation annotation, and c) poly ADP-ribosylation annotation.

For the instance of cross-ring fragment ions, the system of Domon and Costello for carbohydrate fragmentation nomenclature [19] was adapted by Hengel et al. such that each carbohydrate ring is assigned a Roman numeral (i.e. I for the ribose closest to the peptide, then II, etc.). Cross-ring fragment ions were notated as numbers indicating which cross ring bond was broken. Similar to the single bond fragments along ADP-ribose, m and p were used to designate on which side of the ring the charge was observed. For example, a fragmentation event at the ribose ring, adjacent to the guanidine functional group, between bonds zero and two would be designated as 0,2pI or 0,2mI depending on which side the charge is observed (Figure 3B).

Given the thorough nature of the Hengel nomenclature, it could be easily adapted to annotate poly ADP-ribosylated peptide fragmentation analysis as well. In this case there is a need to account from which of the many ADP-ribose monomeric units a particular fragment originated. For annotation of poly-ADP-ribosylated proteins and peptides, addition of a number preceding the p or m would indicate which ADP-ribose unit contained the site of fragmentation: i.e. 4p5 would denote a fragment ion consisting of the intact peptide and three full ADP-ribose structures plus a ribose-phosphate unit of the fourth ADP-ribose in the chain (Figure 3C).

Most publications have annotated spectra by either joining lines from the fragment ion to a bond on the structure of ADP-ribose, or have annotated spectra with chemical abbreviations (i.e. AMP etc…) indicating precursor masses that lost a portion of ADP-ribose with a minus sign; e.g. M – xxx etc. [14–15, 17]. Tao et al. [20] annotated spectra with lowercase letters for five potential fragmentation sites on ADP-ribose, including an apostrophe if the fragment ion contained the intact peptide. B and y ions were annotated with an * if the peptide contained ribose phosphate. Although this system adequately annotates the spectra in their manuscript, applying it to spectra that may contain other fragmentation events along the ADP-ribose backbone would require expansion of their nomenclature, and peptide fragments containing other portions of ADP-ribose would require additional symbols. Furthermore, it may be confusing to some to annotate spectra with the letters c and b in reference to ADP-ribose fragment ions when these letters are commonly used to indicate fragmentation along the peptide backbone. Thus, we suggest the more complete nomenclature of Hengel et al. [14] be adopted for use with ADP-ribosylated peptides and poly-ADP-ribosylated peptides.

4. New Findings

In addition to the original mass spectrometry studies on arginine ADP-ribosylated peptides [13–15, 17], two other reports have expanded on the use of tandem mass spectrometry for identifying ADP-ribosylation sites. These are important because in biological systems, ADP-ribosylation occurs on multiple amino acids in addition to arginine. Fedorova et al. were the first to investigate the fragmentation pattern for a synthetic lysine ADP-ribosylated peptide [21]. They observed similar ADP-ribose fragment ions to those that were detected in the arginine ADP-ribosylated peptide studies, and demonstrated increased peptide backbone fragmentation with the use of ECD. Due to the labile nature of the modification, it is not surprising that fragmentation of the pyrophosphate group was observed upon matrix assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI), even at low energies, and that ESI provided a better precursor ion signal. Interestingly, Fedorova et al. proposed the use of cyanoborohydride for reduction of the keto-group to increase precursor ion signal; the 2 Da shift functions in a similar way to 18O labeling for precursor ion recognition after mixing with an untreated sample [21]. Tryptic digestion incorporates two oxygen atoms from water while cleaving proteins at the n-terminal side of lysine or arginine. If this reaction occurs in heavy (18O) water, the mass of the peptide produced increased by 4 Da. Mixing the heavy labeled peptides with the unlabeled peptides prior to MS analysis will produce a series of peaks in the MS spectrum that are 4 Da apart, corresponding to heavy and light peptides, often providing quantitative information for two different sample treatments. Similarly, mixing peptides that were ADP-ribosylated followed by cyanoborohydride reduced peptides with non-modified peptides will produce a similar pair of ions in the mass spectrum, 2 Da apart, which is useful for determining which species are ADP-ribosylated in a complex mixture.

The first mass spectrometry study to report a non-arginine ADP-ribosylated peptide focused on modification to the automodification domain of PARP-1 [20]. A mutant of PARP-1 (where E998Q alters activity to prevent PARP-1 from further polymerizing ADP-ribose chains: essentially changing the enzyme from a poly ADP-ribosyltransferase to a mono ADP-ribosyltransferase) was used by Tao et al. to identify auto ADP-ribosylation sites. As expected the modifications were observed in or near the automodification domain on glutamic acid and aspartic acid residues. Similar to other reports a strong signal in the tandem mass spectra from cleavage at the ADP-ribose pyrophosphate bond was observed.

While a majority of the studies of ADP-ribosylated peptides to date have been conducted with some form of a high resolution hybrid instrument (e.g. an LTQ oribtrap or LTQ-FT), both of which allow some form of electron based fragmentation methods, others have been successful with less complicated mass analyzers (summarized in Table 1 Hengel et. al RCMS 2010 [16]). It is worth noting that because of the predictable nature of the fragmentation pathways of ADP-riobsylated peptides (i.e. cleavage of the pyrophosphate and terminal adenine bonds) that use of MS3 or SRM methods on triple quadrupoles, linear ion traps, and Q-TOFs present equally acceptable approaches to the electron based methods.

5. Standard Preparations

The use of synthetic standards of modified peptides to study ionization and fragmentation is an important step for identifying novel post-translational modifications in a biological system. Such standards allow the MS1 and MSn behavior of a chemically modified peptide to be determined under controlled conditions ahead of trying to interpret similar data from complex biological mixtures. However, in the case of ADP-ribosylated peptides chemical synthesis is not trivial. Early attempts at ADP-ribosyl peptide standard production relied on the use of transferase enzymes, or produced low yields with chemical modification [13, 22]. Recently, two routes of chemical synthesis have been proposed to make relatively pure ADP-ribosylated peptide, or protein, standards without the use of an enzyme. The first approach involves synthesis of protected ribosylated asparagines and glutamine building blocks that are incorporated into peptides via solid phase synthesis, and then undergo reaction to generate ADP-ribosylated peptides [23]. The second method uses aminooxy functionalized amino acids for the incorporation of ADP-ribose onto specific amino acid functional groups [24].

The ability to generate ADP-ribosylated peptide standards with high purity opens the door for a large range of biological experiments. For example, modified peptides can be incubated with PARP-1 to test for substrate specificity for ADP-ribose polymerization. They may also be used as an affinity probe for ADP-ribose binding proteins, or developed as haptens to stimulate ADP-ribose modification antibodies for protection against bacterial infection. In general, choosing which modified peptide standard to use is not a trivial matter, as the behavior of the peptide standard during mass spectrometry experiments can dictate success or failure of the study. In the case of ADP-ribosylation, for optimum results the best standard peptide will be of similar amino acid sequence, length, and contain the same modification site as the predicted ADP-ribosylation sites in the biological system. If some or all of these are unknown, then a range of mixed standards will increase the likelihood of success.

6. Poly-ADP Ribosylation

To date, there are no published poly-ADP-ribosylated peptide tandem mass spectra. This is likely due to many problems with these large branched chain polymers attached to peptides or proteins. For example, the known heterogeneity of the carbohydrate modification will lead to low signal to noise for any single structure making it difficult to detect and characterize. Additionally, attempts to simplify the heavily branched structure by enzymatic treatment will result in loss of the connectivity that one seeks to determine. Thus, the use of tandem mass spectrometry to characterize this branched chain polymer presents an interesting challenge. While anti-PAR antibodies or vicinal cis diol capture reagents such as immobilized boronic acid (used to isolate glycation/glycosylation products containing vicinal cis diols [25]), might be used to enrich poly ADP-ribose modified proteins from a complex biological sample, the challenge of assigning structure to the peptidoglycan-like modification remains. Simplification of the original polymer through enzymatic or chemical cleavage of the ADP-ribose moieties from the protein or peptide to increase the signal to noise of modified peptides and decrease heterogeneity of the ADP-ribose component may be the most likely strategy for success, despite loss of structural detail of the modification. Ideally this would be done in a way that leaves a small chemical tag consisting of part of the original ADP-ribose structure on the peptide that could be used to confirm the amino acid site of modification.

For poly ADP-ribosylated peptides, the large heterogeneity present in the glycan portion of the molecule may preclude any characterization without first reducing the glycan to its most basic subunit. As mentioned above this would aid characterization of the peptide modification site, but would result in loss of the structural detail contained in the glycan structure. Therefore, it may be necessary to utilize alternate approaches to identify and characterize poly-ADP-ribosylated peptides other than those discussed for mono-ADP-ribosylation analysis, or modification site identification and polymer characterization may require two separate analyses. One way this has been successfully explored is to stop the polymerization reaction with the addition of ADP-ribosylhydrolase 3 (ARH3), which hydrolyzes ester linkages between ADP-ribose units. This method was used by Messner et al. to identify PARP-1 targets on histone N terminal tails [26]. However, the method will allow for the identification of mono ADP-ribosylated peptides only in the cases where the modified amino acid is not negatively charged (i.e. glutamic or aspartic acids). Otherwise the entire modification will be cleaved from the amino acid linker. The work of Messner et al. successfully demonstrated that PARP-1 targets amino acids other than glutamic acid. Alternatively, another approach that may prove successful for identification of the site of peptide poly ADP-ribosylation is the use of snake venom phosphodiesterases (PDE). PDEs have historically been used to cleave the pyrophosphate bond between ADP-ribose units for quantification and characterization of poly ADP-ribose units generated by PARP-1[27]. If snake venom PDE was used to cleave the pyrophosphate bond on an ADP-ribosylated peptide, then the resulting peptide-ribose-phosphate moiety (Figure 4) would be more amenable to sequence assignment via CID (as well as ECD and ETD) because this would decrease heterogeneity in the glycan to a single structure.

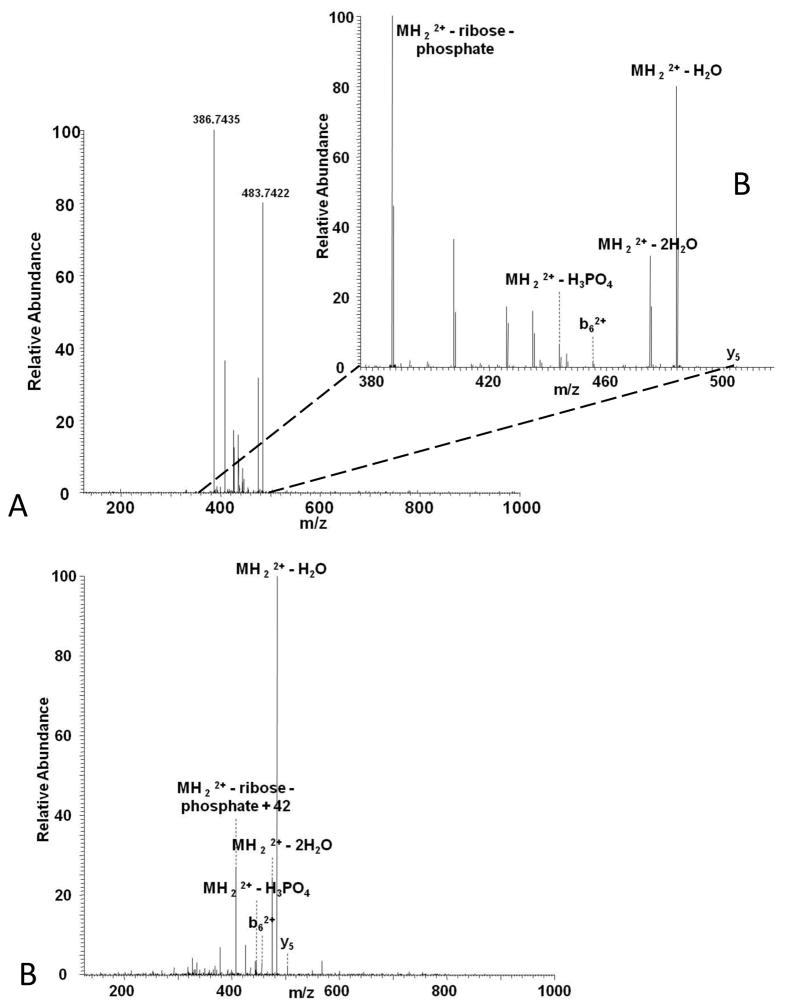

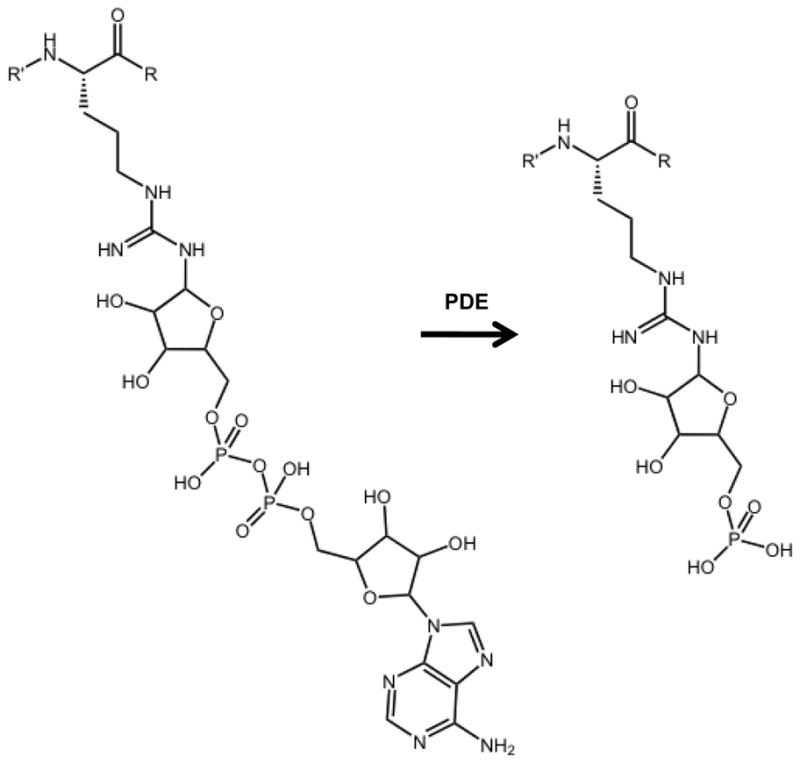

Figure 4.

Phosphodiesterase (PDE) treatment of mono ADP-ribosylated peptide yields a ribose mono-phosphate peptide adduct.

As a preliminary test, Hengel [28] incubated ADP-ribosylated Kemptide with purified PDE using manufacturer’s suggested conditions at room temperature overnight and analyzed as previously described [13]. Notably, the CID tandem mass spectrum of PDE treated ADP-ribosylated Kemptide (Figure 5A) generated a very different fragmentation pattern compared to ADP-ribosylated Kemptide. In this case the main fragment ion corresponds to a neutral loss of ribose mono-phosphate (Figure 5B). As with CID of ADP-ribosylated Kemptide, very little peptide sequence information was observed. From these experiments however, it was noted that a prominent neutral loss of ribose mono-phosphate was observed, similar to the neutral loss of phosphate by phosphorylated peptides subjected to CID [8]. This provides another approach for characterization of ADP-ribosylated peptides through MS3 triggering with observed ribose mono-phosphate neutral loss or multistage activation (MSA), both of which may be initiated in real time during LCMS2 experiments. While MSA based CID tandem mass spectra of ribose mono-phosphate modified Kemptide (Figure 5C) did not allow for further peptide sequencing, it is predicted from this data that MSA of PDE treated ADP-ribosylated peptides of different sequences would provide greater sequence information. Thus, use of PDE to aid in the analysis of mono-ADP-ribosylated peptides in combination with MS3 triggered peptide sequencing on the aforementioned neutral loss will be a viable alternative where access to ECD is not feasible, and is a potential means for poly ADP-ribosylated peptide analysis.

Figure 5.

A) CID tandem mass spectrum of PDE treated Kemptide, B) zoomed in m/z range of CID spectrum, and C) MSA CID spectrum of PDE treated ADP-ribosylated Kemptide.

7. Conclusions

In conclusion, mass spectrometry is a powerful tool for the assignment of mono ADP-ribosylation sites. Due to the labile nature of the peptide-ADP-ribose bonds, MS acquisition schemes have been tailored for the specific detection and identification of ADP-ribosylated peptides. The use of electron based fragmentation methods are extremely useful in preserving the modification upon fragmentation, while CID produces unique fragment ions that are useful for confirming the presence of ADP-ribose. Because of the unique fragment ions observed when fragmenting ADP-ribosylated peptides, the use of a consistent nomenclature as suggested herein would be advantageous to the community. Additionally, the use of synthetic standards is predicted to increase the breadth of ADP-ribosylation studies, further demonstrating the importance of ADP-ribosylation in biology.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants NIH 1U54 AI57141-02, NIH AI064515, NIH Pharmacological Sciences Training Grant (T32 GM07750), National Center for Research Resources Grant 1S10RR-017262-01. This work was also supported in part by the University of Washington’s Proteomics Resource, grant UWPR95794.

Acronyms

- ADPRTs

ADP-ribosyl transferases

- ADP

adenosine diphosphate

- CID

collision induced dissociation

- ECD

electron capture dissociation

- ETD

electron transfer dissociation

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- IRMPD

infrared multiphoton dissociation

- LCMS2

liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- MALDI

matrix assisted laser desorption ionization

- MSA

multistage activation

- PARG

poly-(ADP-ribose)-glycohydrolase

- PARPs

poly ADP-ribose polymerases

- PDE

phosphodiesterases

- PTMs

post-translational modifications

- SSBs

single strand breaks

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Corda D, Di Girolamo M. Functional aspects of protein mono-ADP-ribosylation. EMBO J. 2003;22:1953–1958. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paone G, Wada A, Stevens LA, Matin A, Hirayama T, Levine RL, Moss J. ADP ribosylation of human neutrophil peptide-1 regulates its biological properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8231–8235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122238899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diefenbach J, Burkle A. Introduction to poly(ADP-ribose) metabolism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:721–730. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4503-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Amours D, Desnoyers S, D’Silva I, Poirier GG. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation reactions in the regulation of nuclear functions. Biochem J. 1999;342( Pt 2):249–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petermann E, Keil C, Oei SL. Importance of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases in the regulation of DNA-dependent processes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:731–738. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4504-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubinstein WS. Hereditary breast cancer: pathobiology, clinical translation, and potential for targeted cancer therapeutics. Fam Cancer. 2008;7:83–89. doi: 10.1007/s10689-007-9147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haince JF, Rouleau M, Hendzel MJ, Masson JY, Poirier GG. Targeting poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation: a promising approach in cancer therapy. Trends Mol Med. 2005;11:456–463. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huddleston MJ, Annan RS, Bean MF, Carr SA. Selective Detection of Phosphopeptides in Complex-Mixtures by Electrospray Liquid-Chromatography Mass-Spectrometry. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 1993;4:710–717. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(93)80049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunter AP, Games DE. Chromatographic and Mass-Spectrometric Methods for the Identification of Phosphorylation Sites in Phosphoproteins. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 1994;8:559–570. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1290080713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dookeran NN, Yalcin T, Harrison AG. Fragmentation reactions of protonated alpha-amino acids. Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 1996;31:500–508. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eng JK, Mccormack AL, Yates JR. An Approach to Correlate Tandem Mass-Spectral Data of Peptides with Amino-Acid-Sequences in a Protein Database. J Am Soc Mass Spectr. 1994;5:976–989. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Margarit SM, Davidson W, Frego L, Stebbins CE. A steric antagonism of actin polymerization by a salmonella virulence protein. Structure. 2006;14:1219–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hengel SM, Shaffer SA, Nunn BL, Goodlett DR. Tandem mass spectrometry investigation of ADP-ribosylated kemptide. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2009;20:477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osago H, Yamada K, Shibata T, Yoshino K, Hara N, Tsuchiya M. Precursor ion scanning and sequencing of arginine-ADP-ribosylated peptide by mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2009;393:248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zee BM, Garcia BA. Electron transfer dissociation facilitates sequencing of adenosine diphosphate-ribosylated peptides. Anal Chem. 2010;82:28–31. doi: 10.1021/ac902134y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hengel SM, Icenogle L, Collins C, Goodlett DR. Sequence assignment of ADP-ribosylated peptides is facilitated as peptide length increases. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2010;24:2312–2316. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oetjen J, Rexroth S, Reinhold-Hurek B. Mass spectrometric characterization of the covalent modification of the nitrogenase Fe-protein in Azoarcus sp. BH72. FEBS J. 2009;276:3618–3627. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu S, Lourette NM, Tolic N, Zhao R, Robinson EW, Tolmachev AV, Smith RD, Pasa-Tolic L. An integrated top-down and bottom-up strategy for broadly characterizing protein isoforms and modifications. J Proteome Res. 2009;8:1347–1357. doi: 10.1021/pr800720d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domon B, Costello CE. A Systematic Nomenclature for Carbohydrate Fragmentations in FAB-MS/MS Spectra of Glycoconjugates. Glycoconjugate Journal. 1988;5:13. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tao Z, Gao P, Liu HW. Identification of the ADP-ribosylation sites in the PARP-1 automodification domain: analysis and implications. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:14258–14260. doi: 10.1021/ja906135d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fedorova M, Frolov A, Hoffmann R. Fragmentation behavior of Amadori-peptides obtained by non-enzymatic glycosylation of lysine residues with ADP-ribose in tandem mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2010;45:664–669. doi: 10.1002/jms.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kharadia SV, Graves DJ. Relationship of phosphorylation and ADP-ribosylation using a synthetic peptide as a model substrate. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:17379–17383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Heden van Noort GJ, van der Horst MG, Overkleeft HS, van der Marel GA, Filippov DV. Synthesis of mono-ADP-ribosylated oligopeptides using ribosylated amino acid building blocks. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5236–5240. doi: 10.1021/ja910940q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moyle PM, Muir TW. Method for the synthesis of mono-ADP-ribose conjugated peptides. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15878–15880. doi: 10.1021/ja1064312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furth AJ. Methods for Assaying Nonenzymatic Glycosylation. Anal Biochem. 1988;175:347–360. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90558-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Messner S, Altmeyer M, Zhao H, Pozivil A, Roschitzki B, Gehrig P, Rutishauser D, Huang D, Caflisch A, Hottiger MO. PARP1 ADP-ribosylates lysine residues of the core histone tails. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:6350–6362. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah GM, Poirier D, Duchaine C, Brochu G, Desnoyers S, Lagueux J, Verreault A, Hoflack JC, Kirkland JB, Poirier GG. Methods for biochemical study of poly(ADP-ribose) metabolism in vitro and in vivo. Anal Biochem. 1995;227:1–13. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hengel SM. Proteomic mass spectrometry: from data-independent proteome profiling to the characterization of post-translational modifications. University of Washington; 2010. [Google Scholar]