Abstract

Purpose

Interstitial deletions of chromosome 5q are common in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), pointing toward the pathogenic role of this region in disease phenotype and clonal evolution. The higher level of resolution of single-nucleotide polymorphism array (SNP-A) karyotyping may be used to find cryptic abnormalities and to precisely define the topographic features of the genomic lesions, allowing for more accurate clinical correlations.

Patients and Methods

We analyzed high-density SNP-A karyotyping at diagnosis for a cohort of 1,155 clinically well-annotated patients with malignant myeloid disorders.

Results

We identified chromosome 5q deletions in 142 (12%) of 1,155 patients and uniparental disomy segments (UPD) in four (0.35%) of 1,155 patients. Patients with deletions involving the centromeric and telomeric extremes of 5q have a more aggressive disease phenotype and additional chromosomal lesions. Lesions not involving the centromeric or telomeric extremes of 5q are not exclusive to 5q− syndrome but can be associated with other less aggressive forms of MDS. In addition, larger 5q deletions are associated with either del(17p) or UPD17p. In 31 of 33 patients with del(5q) AML, either a deletion involving the centromeric and/or telomeric regions or heterozygous mutations in NPM1 or MAML1 located in 5q35 were present.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that the extent of the affected region on 5q determines clinical characteristics that can be further modified by heterozygous mutations present in the telomeric extreme.

INTRODUCTION

The most common karyotypic abnormality in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) is an interstitial deletion of the long arm of chromosome 5 (del[5q]), occurring in 10% to 15% of cases.1 The presence of an isolated del(5q), a blast count of less than 5% in the bone marrow and less than 1% in the peripheral blood, and absence of Auer rods are required for the current WHO definition of a classical 5q− syndrome.2 Patients with 5q− syndrome show a relatively uniform clinical phenotype and a low rate of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) progression.3,4 Cases of non-5q− syndrome myeloid disorders with losses of genetic material involving chromosome 5 have consistently been associated with poor prognoses.5,6

Single-nucleotide polymorphism arrays (SNP-A) have been applied for high-resolution whole-genome scanning in myeloid malignancies, in which copy number changes and recurrent copy neutral loss of heterozygosity have been shown to be common.7 We have also shown that the higher resolution of SNP-A may be used to find cryptic abnormalities and to precisely define the topographic features of the genomic lesions.8

The common deleted regions (CDR) among 5q disorders have been extensively studied, with two CDRs reported: a distal CDR deleted in the 5q– syndrome and a proximal region in higher-risk MDS and AML.9,10 However, most patients have large deletions encompassing both CDRs, precluding precise discrimination between different disorders using conventional cytogenetics. In addition, commonly retained regions (CRRs) associated with del(5q) disorders have not been systematically studied.

To better address the genetic and genomic complexity of 5q abnormalities in myeloid malignances, we analyzed a large series of cases with SNP-A–based karyotyping to define (1) the extent of the 5q deletion, investigating whether loss of genes is different among 5q disorders; (2) minimally deleted region(s); (3) associated non-5q genomic lesions with 5q abnormalities; and (4) the association of genomic abnormalities with clinical features.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Informed consent was obtained according to protocols approved by the review boards of participating institutions. Presentation bone marrow (BM) aspirates were collected from 1,155 patients and studied using SNP-A. Diagnoses, including pathology specimens, were reviewed at each of the participating centers and adapted, when required, to WHO 2008 criteria.2

Metaphase Cytogenetics

Chromosome preparations were G-banded using trypsin and Giemsa, and karyotypes were described according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature.11

SNP-A Analysis

Affymetrix Genome-Wide Human SNP Array 6.0 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) and Illumina HumanCytoSNP-12 (Illumina, San Diego, CA) were used for SNP-A analysis of BM DNA as previously described.8 Germline-encoded copy number variations and nonclonal areas of uniparental disomy (UPD) were excluded from further analysis by a bioanalytic algorithm on the basis of lesions identified by SNP-A in an internal control series (n = 1,003) and reported in the Database of Genomic Variants.12 Size and location criteria (telomeric > 8.7 Mb and interstitial ≥ 25 Mb in size) were used for identification of somatic UPD. In four cases of 5q UPD involving the CDRs, additional germline analysis was performed.

Polymerase Chain Reaction Direct Sequencing Assays

Primer sequences are shown in the Data Supplement.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons of proportions and ranks of variables between groups were performed by χ2 test, Fisher's exact test, t test, or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. We used the Kaplan-Meier and the Cox method to analyze overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS), with a two-sided P value ≤ .05 considered to be significant. In Cox models, examination of log (−log) survival plots and partial residuals was performed to assess that the underlying assumption of proportional hazards was met.

RESULTS

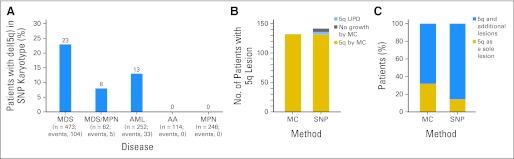

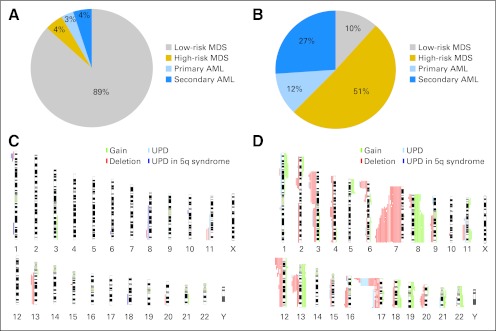

Using SNP-A karyotyping, deletions of 5q were identified in 142 (12%) of 1,155 patients among MDS, MDS/myeloproliferative neoplasms, and AML subsets (Fig 1A). Four additional patients harbored somatic UPD of 5q and are presented separately later. Metaphase cytogenetics (MC) identified 5q deletions in each of the cases detected by SNP-A, except for six patients in whom no interpretable metaphases were obtained (Fig 1B). With increased resolution, there was a shift toward more complex karyotypes and increased identification of additional lesions among the patients with 5q aberrations (Fig 1C). By SNP-A, previously cryptic lesions were identified in 52% of the patients who otherwise showed a singular del(5q) lesion by MC. In 11 cases, MC identified putative monosomy 5; in all cases, SNP-A analysis found retained chromosome 5 material, primarily from the short arm, most likely contributing to marker chromosomes found by MC analysis.

Fig 1.

Frequency of detection of 5q abnormalities by metaphase cytogenetics (MC) and single-nucleotide polymorphism array (SNP-A). (A) Distribution of 142 patients with 5q deletion, among the 1,155 SNP-A–tested patients with myeloid malignancies, according to WHO classification. (B) Number of patients with 5q loss of heterozygosity seen on MC and SNP-A. Lesions were observed in 132 of 1,155 and 142 of 1,155 patients when using MC and SNP-A, respectively. Additional 5q lesions were found in noninformative MC (n = 6) or presence of uniparental disomy (UPD; n = 4). (C) Percentage of patients with a sole 5q lesion versus accompanied by other abnormalities as identified by MC and SNP-A. Sole 5q lesions were observed in 44 of 142 versus 21 of 142 patients by MC and SNP-A, respectively. AA, aplastic anemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MPN, myeloproliferative neoplasms.

The 5q deletion cohort included men (52%) and women (48%) with a median age of 65 years (interquartile range, 57 to 72 years). The median size of the 5q deletion within the entire cohort was 71.4 Mb by SNP-A analysis (range, 1.9 Mb to 131.28 Mb [whole arm]). Segmental UPD involving 5q, proven somatic by germline analysis, was found in four patients; two of these defects (L034 and L035) presented with secondary AML. In addition to UPD5q, patient L027 showed trisomy 19. A complex SNP-A–based karyotype (one microdeletion, three UPDs) was detected in patient L035.

Interestingly, two patients showed a UPD segment encompassing the del(5q) CDR and a normal MC study. Patient SMD076, with a diagnosis of refractory anemia with ring sideroblasts, was found by SNP-A to have an isolated UPD from 5q23.2 to 5q31.3. Morphologically, the patient's BM revealed numerous small hypolobated megakaryocytes and marked erythroid hypoplasia with a peripheral platelet count of 298,000/μL. He subsequently became transfusion dependant 1 year after presentation. Patient SMD077 presented with UPD5q (from 5q14.2 to the 5q telomere) with normal MC. A cryptic small clone containing a deletion of 5q32q34 further increased the cytogenetic complexity. This patient presented with transfusion-dependent macrocytic anemia, a normal platelet count, and a mild increase in the megakaryocyte number in the BM with predominance of small forms. He was treated with lenalidomide, achieving transfusion independence followed by lenalidomide-refractory relapse.

Commonly Deleted and Retained Regions as Defined by SNP-A

CDR-1.

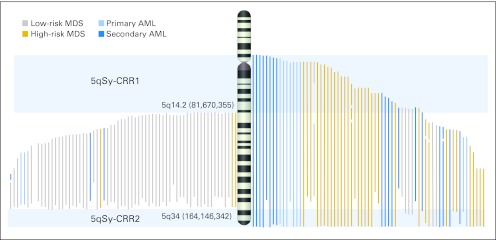

All 5q deletions detected by SNP-A in the 29 patients with 5q syndrome were interstitial (Appendix Fig A1, online only). The CDR in this subset spanned 8.5 Mb and was located between 5q32 and 5q33.2 (145,279,940 to 153,809,148). The proximal and terminal regions of the long arm of chromosome 5 were always retained, and we were therefore able to define proximal and distal commonly retained regions (CRR1 and CRR2, respectively). CRR1 spanned 81.7 Mb and ended at band 5q14.2 (1 to 81,670,355). CRR2 encompassed 1.7 Mb, beginning at 5q34 (164,146,342 to 180,857,866). Henceforth, we refer to both CRR1 and CRR2 as 5q− syndrome CRRs (5qSy-CRRs).

CDR-2.

In other forms of MDS with patients with del(5q) and 5q AML, the CDR stretched from base pair 137,528,564 to 139,451,907 and had a size of approximately 1.92 Mb. This region, centered on a subsection of bands 5q31.2 and 5q31.3, is defined by the lesion found in patient L30. This patient showed dyserythropoiesis with dysplastic megakaryocytes, a markedly high platelet count at diagnosis, and a complex chromosomal rearrangement event (Data Supplement). No CRR could be identified in this subset of patients.

Correlations Between Size/Location of the Lesions and Disease Characteristics

The definition of the 5qSy-CRRs and the observation that most of the 5q AML deletions occupied the proximal and/or telomeric extreme portions of the q arm enabled discrimination of two subsets of patients: those whose deletion involved, or spared, the regions retained by patients with 5q− syndrome (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Identification of commonly retained regions and their association with disease subtypes. Mapping of deletions detected by single-nucleotide polymorphism array in the cohort separated according the involvement (right) or not (left) of 5q– syndrome commonly retained regions. Deletions have been colored depending on the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) risk group at diagnosis (myelodysplastic syndrome; MDS) or de novo or secondary origin (acute myeloid leukemia; AML). Low-risk MDS includes low and intermediate-1 IPSS groups. High-risk MDS includes intermediate 2 and high-risk IPSS groups.

Appendix Figure A2 (online only) illustrates the distribution of genomic lesions in each group, with those patients with the 5qSy-CRRs characterized by (1) a lower number of genomic lesions per patient (1.1 v 5.8; P ≤ .001); (2) absence of whole-chromosome UPDs, deletions, or gains; (3) a lower median size of lesions (10 v 20.9 Mb; P ≤ .04); and (4) the absence of 17p loss of heterozygosity (LOH) cases.

Of 67 patients, 38 (54%) showed 5qSy-CRRs but did not fulfill the diagnostic criteria of 5q− syndrome. These patients had predominantly lower-risk disease (n = 29, 80%).

Associated genomic lesions.

None of the 29 patients with 5q− syndrome had additional copy number changes involving other chromosomes. However, regions of UPD were found in six patients within segments of 1p, 1q, 6q, 10q, and 18q (Fig 2).

Among the 137 patients in our del(5q) MDS and AML cohort (29 5q− syndrome, 75 other forms of del[5q] MDS, and 33 del[5q] AML cases), we found 143 deletions of 5q (four and one patient had two and three separate segments deleted, respectively). Del(7q) was the most common del(5q)-associated lesion present, occurring in 27 of 137 patients, 23 of whom had AML or higher-risk MDS. This was followed closely by LOH 17p, seen in 26 of 137 patients, of whom eight of 26 were UPDs. Similar to patients with 7q, all patients had advanced stages of MDS or AML at diagnosis. All patients with LOH 17p spanned TP53; in 15 patients, DNA was available to be sequenced: TP53 mutations were found in 13 cases. Mutation characteristics are summarized in the Data Supplement.

Clinical correlates.

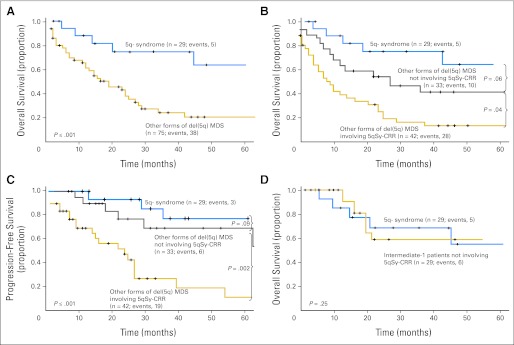

Because of the relatively scarce number of patients in the del(5q) AML group, we focus this section on the clinical and prognostic features of the 104 patients with MDS and del(5q). With a median follow-up of 42 months (interquartile range, 29 to 72 months), the median OS in the 5q− syndrome group has not been reached, whereas patients with others forms of MDS with del(5q) had a worse prognosis, with a median OS of 22 months (Fig 3A). Considering age, transfusion requirements at diagnosis, dysgranulopoiesis, presence of UPD, and platelet count as potential prognostic factors for OS, we found that only the presence of additional UPD (P = .022; hazard ratio [HR] = 6.5; 95% CI, 1.3 to 32.4) and an age greater than 70 years (P = .025; HR = 6.1; 95% CI, 1.1 to 34) were statistically significant. Although three (10%) of 29 patients with 5q− syndrome progressed to higher-risk MDS or AML, advanced disease was observed in 25 (33%) of 75 patients with other forms of del(5q).

Fig 3.

Differences in survival outcomes and progression-free survival in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) with del(5q). P values presented correspond to the Cox regression between the groups indicated. (A) Comparison of survival outcomes between 5q- syndrome and other forms of del(5q) MDS. (B, C) Patients with other forms of del(5q) MDS were divided according to the involvement of the 5q– syndrome (5qSy) commonly retained region (CRR). (D) There was no difference in survival when comparing 5q syndrome patients with those patients with del(5q) whose lesions did not involve CRR but who could not be classified as 5q– syndrome because of the presence of an additional cytogenetic aberration or more than 5% bone marrow blasts (intermediate-1 International Prognostic Scoring System score).

When patients with other forms of del(5q) MDS were analyzed, those whose 5q deletion did not include the CRR presented with a higher platelet count (171 v 84 × 105/uL; P ≤ .001), and lower proportion of erythroblasts (15% v 27%;P ≤ .03) than those with deletions including the CRR (Table 1). Median OS in this group was 32 months versus 14 months in patients whose lesions did involve CRRs (P = .04; HR = 1.9; 95% CI, 1.2 to 3.8 CI; Fig 3B). Similarly, patients with smaller lesions had lower rates of transformation to higher-risk MDS or AML than those involving the extremes of 5q (P = .002; HR = 2.2; 95% CI, 1.4 to 4.1; Fig 3C).

Table 1.

Comparison of Clinical Characteristics Between Patients With 5q– Syndrome and Other Forms of del(5q) MDS Grouped According to the Involvement of 5qSy-CRR

| Characteristic | 5q– Syndrome (n = 29; A) | P (A v B) | Other Forms of del(5q) MDS not Involving 5qSy-CRRs (n = 33; B) | P (B v C) | Other Forms of del(5q) MDS Involving 5qSy-CRRs (n = 42; C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | .79 | .19 | |||

| Median | 65 | 65 | 67 | ||

| Range | 57-69 | 54-71 | 59-76 | ||

| Sex, % | |||||

| Male | 33 | .5 | 42 | .26 | 57 |

| Female | 67 | 58 | 43 | ||

| WBC count, ×109/L | .9 | .5 | |||

| Median | 4.0 | 3.8 | 4.1 | ||

| IQR | 3.5-5.7 | 2.5-4.9 | 2.6-9.6 | ||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | .2 | .6 | |||

| Median | 10 | 9.7 | 9.4 | ||

| IQR | 8.8-11 | 8.4-10.3 | 8.5-9.7 | ||

| Mean corpuscular volume | .06 | .03 | |||

| Median | 103 | 98 | 86.6 | ||

| IQR | 94-111.5 | 86.8-104.8 | 83-96 | ||

| Platelets, ×109/L | .09 | ≤ .001 | |||

| Median | 198 | 112 | 55 | ||

| IQR | 119-442 | 70-223 | 30-81 | ||

| Erythroblasts in BM, % | .6 | .03 | |||

| Median | 15 | 17 | 31 | ||

| IQR | 10.5-20.5 | 10.7-28 | 12-50 | ||

| Presence of monolobated megakaryocytes in BM, % | 100 | .006 | 49 | .04 | 22 |

| IPSS risk group, % | .079* | ≤ .001* | |||

| Low | 93 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Intermediate-1 | 7 | 87 | 25 | ||

| Intermediate-2 | 0 | 9 | 59 | ||

| High | 0 | 4 | 16 | ||

| MC IPSS group, % | ≤ .001 | ≤ .001 | |||

| Good | 100 | 40 | 6 | ||

| Normal | 0 | 45 | 30 | ||

| Poor | 0 | 15 | 64 | ||

| First-line treatment received, % | .8† | .09† | |||

| Supportive care | 45 | 38 | 20 | ||

| Hypometilating agents | 0 | 12 | 27 | ||

| Lenalidomide | 42 | 33 | 20 | ||

| Hypometilating agent plus lenalidomide | 0 | 10 | 13 | ||

| Intensive chemotherapy (AML-like ± BMT) | 0 | 0 | 17 | ||

| Others | 12 | 8 | 3 |

NOTE. Boldface indicates significant P values.

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; BMT, bone marrow transplantation; del(5q), deletion of 5q; IPSS, International Prognostic Scoring System; IQR, interquartile range; MC, metaphase cytogenetics; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; 5qSy-CRR, 5q– syndrome commonly retained region.

P value of comparing IPSS groups dichotomized as low and intermediate-1 IPSS group v intermediate 2 and high-risk IPSS group.

P value of comparing first-line treatment received dichotomized as supportive care (including erythropoiesis and granulocyte colony-stimulating stimulating factor) v other therapies.

There were a number of patients with del(5q) whose lesions did not involve CRR but who could not be classified as having the 5q− syndrome because of the presence of an additional cytogenetic aberration or more than 5% BM blasts (n = 29). When these patients were compared with those with 5q− syndrome, no significant differences were found with respect to outcome (Fig 3D), median platelet count, median corpuscular volume, median percentage of erythroblasts in the BM, median WBCs, or median hemoglobin levels at diagnosis (all P > .05).

The presence of deletions involving the 5qSy-CRRs did not show independent prognostic value in a multivariate model including the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS; P = .157). To test the validity of SNP-A findings as the karyotyping variable within the IPSS in patients with del(5q) MDS, three independent Cox multivariate models were developed (Table 2). In each model, the nonkaryotyping IPSS variables (ie, BM blast percentage and number of cytopenias) were retained, whereas a different karyotyping variable was included (IPSS metaphase cytogenetic categories, involvement of the 5qSy-CRRs, and an SNP-A variable categorized as good, not involving 5qSy-CRR; intermediate, involving 5qSy-CRR; and poor, involving 5qSy-CRR plus 17p LOH).

Table 2.

Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Models Testing the Prognostic Value of SNP-A as the Genetic Variable in the IPSS

| First Multivariate Cox Model |

Second Multivariate Cox Model |

Third Multivariate Cox Model |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | P | HR | 95% CI | Variable | P | HR | 95% CI | Variable | P | HR | 95% CI |

| BM blasts* | .03 | 1.9 | 1.2 to 2.9 | BM blasts* | .01 | 1.7 | 1.1 to 2.7 | BM blasts* | .004 | 1.7 | 1.1 to 2.7 |

| No. of cytopenias† | .04 | 2.1 | 1 to 4.3 | No. of cytopenias† | .05 | 2 | 0.9 to 4.1 | No. of cytopenias† | .05 | 2 | 0.9 to 4.1 |

| Cytogenetic category‡ | .04 | 1.5 | 1.1 to 2.2 | Involvement of 5qSy-CRR | .04 | 2.3 | 1.1 to 5 | SNP array category§ | .003 | 2.9 | 1.5 to 3.5 |

Abbreviations: BM, bone marrow, HR, hazard ratio; 5qSy-CRR, 5q– syndrome commonly retained region; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Three BM blasts categories according to the percentage described: < 5; 5 to 10; and 11 to 20.

No. of cytopenias categories defined as good: 0 to 1; and poor: 2 to 3. Cytopenias defined as hemoglobin < 10 g/dL, absolute neutrophil count < 1.8 × 109/L, and platelets < 100 × 109/L.

Cytogenetic categories defined as good: normal, -Y, del(5q), del(20q); poor: chromosome 7 anomalies, complex (3 or more abnormalities); and intermediate: all others.

SNP array category defined as good: not involving 5qSy-CRR; intermediate: involving 5qSy-CRR; and poor: involving 5qSy-CRR plus 17p loss of heterozygosity.

The second and third model support the validity of SNP-A findings as a karyotyping variable in the IPSS in the context of del(5q) MDS. In addition, these three SNP-A–defined groups showed statistical trend to add independent prognostic information to the IPSS when both were included in a Cox regression analysis (SNP-A– defined groups: P = .057, HR = 1.2, 95% CI, 0.99 to 1.4; IPSS: P ≤ .001, HR = 2.2, 95% CI, 1.5 to 2.4).

Exploring the Extremes of 5q for Point Mutations: MAML1 and NPM1

Five patients presented with AML, but their deletions did not involve the CRRs. To explain their exceptional aggressive course, we hypothesized that the CRRs may contain mutations leading to inactivation/haploinsufficiency of a predicted suppressor genes in this area. We chose to screen six genes related to the TP53 pathway and located in the corresponding centromeric or telomeric regions of 5q: ENC1 (5q13.3), SNCB (5q35.2), TAF9 (5q13.2), MAPK9 (5q35.3), MAML1 (5q35.3), and NPM1 (5q35.1).13–18 In four of five patients, we found one of these genes mutated: one patient shared NPM1 type A (tandem duplication of TCTG in exon 12) and a MAML1 mutation (N800T); two patients had a MAML1 mutation (S360C, D441Y); and one patient had a NPM1 mutation A. In addition, we tested 20 patients with del(5q) AML, 41 with del(5q) MDS (10 with 5q– syndrome), and 20 with non-5q AML, without finding any mutations in these six genes.

DISCUSSION

Knowledge of the CDR on the q-arm of chromosome 5 has been essential for the identification of pathogenic genes that determine the clinical features of the dysplastic clone, but no genomic aberration has been able to explain clone inception or progression to AML. In this study, we took advantage of high-resolution SNP-A to accurately define the extent of chromosomal lesions in a large cohort of patients with myeloid malignancies involving deletion of the long arm of chromosome 5. Our analysis demonstrated that deletions not involving the centromeric and telomeric extremes of 5q are associated with a more indolent course and fewer associated chromosomal abnormalities. No major prognostic differences in outcome could be discerned between patients with classical 5q syndrome and those with low-grade MDS with del(5q) of the same extent. In agreement with this observation, 31 of 33 patients with 5q AML had either a deletion involving the centromeric and/or telomeric regions, or, if the lesion did not involve the CRR, heterozygous mutations in NPM1 or MAML1 located in 5q35 were present.

The relatively indolent course of 5q– syndrome patients has been associated with genomic stability.19 However, we found regions of somatic UPD in 25% 5q– syndrome patients, a lower proportion than previously described.20 We attribute this difference to a more stringent algorithm allowing for exclusion of germline copy number variants.

Most previous studies did not find an association between outcome and the extension of the deletion.21,22 The presence of chromosome 5q material in all our cases with apparent monosomy 5 (n = 11) by conventional MC serves as an illustration for SNP-A-based mapping allowing for a more precise definition of the breakpoints and is, in principle, comparable to results obtained previously for chromosome 20 and 17.8,23 In addition, 48% of MC results localized both the beginning and end of the deletion to a different band than SNP-A, and in only 9% of cases, MC and SNP-A boundaries coincided. Interestingly, in a recent study using 11 different 5q fluorescent in situ hybridization probes in 43 cases with isolated del(5q) deletions, the centromeric breakpoints always fell distally to RP11-80K5 (band 5q14.1), and only one of those patients had a deletion involving the NPM1 locus (band 5q35.1).24 Although not strictly comparable to our WHO-defined 5q– syndrome cohort, those results support our definition of 5qSy-CRRs.

In our AML cohort, only five patients showed a deletion not involving the 5qSy-CRRs: four of them displayed either NPM1 and/or MAML1 heterozygous mutations. NPM1, the most commonly mutated gene in normal cytogenetic AML, is associated with myeloid and lymphoid malignancies in haploinsufficient mice,25,26 and MAML1 expression levels have been recently shown to influence cellular sensitivity to cytotoxicity by coactivations of different pathways.17 These findings indicate that decreased gene dosage for NPM1 and MAML1 in patients with large 5q deletions or point heterozygous mutations could contribute to the aggressiveness of MDS. A recent study identified novel inactivating Notch pathway mutations, including MAML1 mutations, in patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia27; our study extends the presence of somatic MAML1 mutations to patients with del(5q) AML.

The CDR defined in our 5q– syndrome patients, though with wider limits, encompasses the CDR described by Boultwood et al.28,29 The CDR in patients with advanced del(5q) MDS and AML is centered on a subsection of bands 5q31.2 and 5q31.3 and includes the defect initially mapped by Le Beau et al.30 Although a strong phenotype–genotype relationship is generally not seen in the 5q AML, illustrating the potential limitations and general applicability of defining the boundaries of CDRs with particularly rare exceptional cases, follow-up studies investigating the candidates in our minimal CDR were successful in identifying epigenetic inactivation of CTNNA1 as a potential MDS to AML disease progression marker.31

Mutations of TP53 have been associated with advanced primary del(5q) MDS and with therapy-related del(5q) MDS and AML.19,31 We showed previously that complex karyotypes with 5q and 7q abnormalities without del(17p) often harbor copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity 17p, a lesion that is cryptic unless analyzed by SNP-A.23 We confirmed this finding in the present study. In addition, all 17p LOH in our cohort were present in patients whose 5q deletion involved the centromeric and/or telomeric regions. Castro et al32 suggested that the loss of chromosome 5q13.3 locus (within our centromeric 5qSy-CRR) precedes mutations in TP53, conferring a proliferative advantage to the dysplastic clone. Fifteen of the 19 17p LOH in our cohort were present in patients with 5q deletion involving the band 5q13.3. Two variables detectable only by means of SNP-A, the involvement of 5qSy-CRR and the presence of 17p LOH, allowed us to define three SNP-A categories that, in our del(5q) series, show a suitable prognostic value as the karyotyping variable in the IPSS. Of note, two patients with 5q isolated somatic UPD showed almost a classical 5q– syndrome phenotype. However, LOH due to UPD questions the mechanisms of haploinsufficiency and raises the possibility of gain of imprinting in these cases.

In summary, the present study of 5q disorders shows that SNP-A can complement traditional MC, not only by finding cryptic abnormalities, but also by precisely defining the extent of the lesions. Our results strongly suggest that although genes widely deleted among 5q disorders may be responsible for the characteristics of the dysplastic clone, the loss of an additional gene or genes in the proximal and telomeric extremes of 5q may be responsible of increasing genomic instability, favoring AML transformation.

Supplementary Material

Appendix

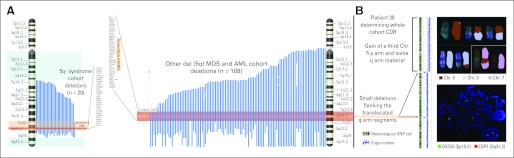

Fig A1.

(A) Mapping of 5q deletions detected by single-nucleotide polymorphism array (SNP-A) in our cohort. Blue lines indicate the deleted regions in each case. On the left, 5q– syndrome subset deletions are shown with a lighter red rectangle encompassing the commonly deleted region (CDR) in our subset. In darker red, Boultwood's27,28 CDR and genes involved are shown as reference. The blue rectangles highlight the two commonly retained regions along the long arm of chromosome 5. On the right, other forms of deletions of patients with del(5q) myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and del(5q) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) are shown. Again, the lighter red rectangle indicates the CDR in this subset and the darker red rectangle references Le Beau's29 CDR. (B) For patient 30, metaphase cytogenetics (MC) detected three copies of chromosome 5: one normal homolog and two copies with a segmental deletion of 5q. However, SNP-A (left) demonstrated that although the p-arm portion had been duplicated, the q arm, with the exception of two small microdeletions approximately 1.35 Mb and 1.92 Mb in length, showed a normal diploid set. We hypothesized that fragments of the q arm had been translocated to other regions in the genome before duplication had occurred and had remained undetectable in the MC analysis. To confirm these results, we performed multicolor SKY (upper right) and found that chromosome 5 material (red) had indeed been displaced to both chromosomes 3 (light blue) and 7 (pink) with a reciprocal translocation of chromosome 3 material occurring on the abnormal chromosome 5. In addition, when we performed fluorescent in situ hybridization analysis (bottom right) using probes for early growth response protein 1 (EGR1) at 5q31.2 (red signal) and for D5S23 at 5p15.2 on the short arm (green signal), the results of SNP-A karyotyping were confirmed, showing only one hybridization signal for EGR1 located in the region affected by the microdeletion. Chr, chromosome.

Fig A2.

(A, B) Distribution of disease subtype among patients with deletions (B) involving the 5q - syndrome CRRs or (A) not. (C, D) Additional single-nucleotide polymorphism–detected genomic lesions separated according the same criteria as previously stated. UPD, uniparental disomy.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health (Grants No. R01 HL082983 to J.P.M., U54 RR019391 to J.P.M. and M.A.S., and K24 HL077522 to J.P.M.); Department of Defense (Grant No. MPO48018 to M.A.M.); Fundacion Caja Madrid; and a charitable donation from Robert Duggan Cancer Research Foundation.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Andres Jerez, Lukasz P. Gondek, Jaroslaw P. Maciejewski

Provision of study materials or patients: Ramon V. Tiu, Michael A. McDevitt, Ghulam J. Mufti, Jaroslaw P. Maciejewski

Collection and assembly of data: Andres Jerez, Lukasz P. Gondek, Anna M. Jankowska, Ramon V. Tiu, Michael A. McDevitt, Ghulam J. Mufti, Jaroslaw P. Maciejewski

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Solé F, Espinet B, Sanz GF, et al. Incidence, characterization and prognostic significance of chromosomal abnormalities in 640 patients with primary myelodysplastic syndromes: Grupo Cooperativo Espanol de Citogenetica Hematologica. Br J Haematol. 2000;108:346–356. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.01868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tefferi A, Vardiman JW. Myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1872–1885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0902908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patnaik MM, Lasho TL, Finke CM, et al. WHO-defined ‘myelodysplastic syndrome with isolated del(5q)' in 88 consecutive patients: Survival data, leukemic transformation rates and prevalence of JAK2, MPL and IDH mutations. Leukemia. 2010;24:1283–1289. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nimer SD. Clinical management of myelodysplastic syndromes with interstitial deletion of chromosome 5q. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2576–2582. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grimwade D, Walker H, Oliver F, et al. The importance of diagnostic cytogenetics on outcome in AML: Analysis of 1,612 patients entered into the MRC AML 10 trial—The Medical Research Council Adult and Children's Leukaemia Working Parties. Blood. 1998;92:2322–2333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrd JC, Mrozek K, Dodge RK, et al. Pretreatment cytogenetic abnormalities are predictive of induction success, cumulative incidence of relapse, and overall survival in adult patients with de novo acute myeloid leukemia: Results from Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 8461) Blood. 2002;100:4325–4336. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gondek LP, Tiu R, O'Keefe CL, et al. Chromosomal lesions and uniparental disomy detected by SNP arrays in MDS, MDS/MPD, and MDS-derived AML. Blood. 2008;111:1534–1542. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-092304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huh J, Tiu RV, Gondek LP, et al. Characterization of chromosome arm 20q abnormalities in myeloid malignancies using genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism array analysis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2010;49:390–399. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boultwood J, Fidler C, Strickson AJ, et al. Transcription mapping of the 5q- syndrome critical region: Cloning of two novel genes and sequencing, expression, and mapping of a further six novel cDNAs. Genomics. 2000;66:26–34. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai F, Godley LA, Joslin J, et al. Transcript map and comparative analysis of the 1.5-Mb commonly deleted segment of human 5q31 in malignant myeloid diseases with a del(5q) Genomics. 2001;71:235–245. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaffer LG, Slovak ML, Campbell LJ. International Standing Committee on Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature: An International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature. Switzerland: Basel; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centre for Applied Genomics. Database of Genomic Variants. http://projects.tcag.ca/variation/

- 13.da Costa CA, Masliah E, Checler F. Beta-synuclein displays an antiapoptotic p53-dependent phenotype and protects neurons from 6-hydroxydopamine-induced caspase 3 activation: Cross-talk with alpha-synuclein and implication for Parkinson's disease. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37330–37335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306083200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polyak K, Xia Y, Zweier JL, et al. A model for p53-induced apoptosis. Nature. 1997;389:300–305. doi: 10.1038/38525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uesugi M, Verdine GL. The alpha-helical FXXPhiPhi motif in p53: TAF interaction and discrimination by MDM2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14801–14806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang C, Ma WY, Li J, et al. Arsenic induces apoptosis through a c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-dependent, p53-independent pathway. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3053–3058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao Y, Katzman RB, Delmolino LM, et al. The notch regulator MAML1 interacts with p53 and functions as a coactivator. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:11969–11981. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608974200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grisendi S, Bernardi R, Rossi M, et al. Role of nucleophosmin in embryonic development and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;437:147–153. doi: 10.1038/nature03915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fidler C, Watkins F, Bowen DT, et al. NRAS, FLT3 and TP53 mutations in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and a del(5q) Haematologica. 2004;89:865–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang L, Fidler C, Nadig N, et al. Genome-wide analysis of copy number changes and loss of heterozygosity in myelodysplastic syndrome with del(5q) using high-density single nucleotide polymorphism arrays. Haematologica. 2008;93:994–1000. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giagounidis AA, Germing U, Haase S, et al. Clinical, morphological, cytogenetic, and prognostic features of patients with myelodysplastic syndromes and del(5q) including band q31. Leukemia. 2004;18:113–119. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mallo M, Cervera J, Schanz J, et al. Impact of adjunct cytogenetic abnormalities for prognostic stratification in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and deletion 5q. Leukemia. 2011;25:110–120. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jasek M, Gondek LP, Bejanyan N, et al. TP53 mutations in myeloid malignancies are either homozygous or hemizygous due to copy number-neutral loss of heterozygosity or deletion of 17p. Leukemia. 2010;24:216–219. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.La Starza R, Matteucci C, Gorello P, et al. NPM1 deletion is associated with gross chromosomal rearrangements in leukemia. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Falini B, Mecucci C, Tiacci E, et al. Cytoplasmic nucleophosmin in acute myelogenous leukemia with a normal karyotype. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:254–266. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sportoletti P, Grisendi S, Majid SM, et al. Npm1 is a haploinsufficient suppressor of myeloid and lymphoid malignancies in the mouse. Blood. 2008;111:3859–3862. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-098251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klinakis A, Lobry C, Abdel-Wahab O, et al. A novel tumour-suppressor function for the Notch pathway in myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2011;473:230–233. doi: 10.1038/nature09999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boultwood J, Fidler C, Lewis S, et al. Molecular mapping of uncharacteristically small 5q deletions in two patients with the 5q− syndrome: Delineation of the critical region on 5q and identification of a 5q− breakpoint. Genomics. 1994;19:425–432. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boultwood J, Fidler C, Strickson AJ, et al. Narrowing and genomic annotation of the commonly deleted region of the 5q− syndrome. Blood. 2002;99:4638–4641. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Beau MM, Espinosa R, 3rd, Neuman WL, et al. Cytogenetic and molecular delineation of the smallest commonly deleted region of chromosome 5 in malignant myeloid diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:5484–5488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ye Y, McDevitt MA, Guo M, et al. Progressive chromatin repression and promoter methylation of CTNNA1 associated with advanced myeloid malignancies. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8482–8490. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castro PD, Liang JC, Nagarajan L. Deletions of chromosome 5q13.3 and 17p loci cooperate in myeloid neoplasms. Blood. 2000;95:2138–2143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.