Summary

Nitric oxide’s expansive physiological and regulatory roles have driven the development of therapies for human disease that would benefit from exogenous NO administration. Already a number of therapies utilizing gaseous NO or NO donors capable of storing and delivering NO have been proposed and designed to exploit NO’s influence on the cardiovascular system, cancer biology, the immune response, and wound healing. As described in Nitric Oxide Release Part I: Macromolecular Scaffolds and Part II: Therapeutic Applications, the preparation of new NO-release strategies/formulations and the study of their therapeutic utility are increasing rapidly. However, comparison of such studies remains difficult due to the diversity of scaffolds, NO measurement strategies, and reporting methods employed across disciplines. This tutorial review highlights useful analytical techniques for the detection and measurement of NO. We also stress the importance of reporting NO delivery characteristics to allow appropriate comparison of NO between studies as a function of material and intended application.

1. Introduction

Nitric oxide is endogenously generated by a heme-containing enzyme called nitric oxide synthase (NOS) via the 5-electron oxidation of the amino acid L-arginine to L-citrulline generating one equivalent of NO.1, 2 Due to the importance of NO in a number of signaling pathways, interruption in the homeostasis of the NOS enzymes directly or indirectly may lead to and/or is characteristic of a particular disease state.3 As such, therapeutics that either regulate NOS activity or produce NO exogenously have become an important research area. Indeed, the number of scaffolds that chemically store and deliver NO include NO-releasing proteins,4 nanoparticles,5, 6 and polymers7, 8 (see Nitric Oxide Release Part I: Macromolecular Scaffolds). These exogenous sources of NO have been investigated as potential medicinal agents for cardiovascular,2, 9 cancer,10 antibacterial,11, 12 and wound healing11, 13 therapies as discussed in Nitric Oxide Release Part II: Therapeutic Applications. However, the knowledge that NO’s effects are concentration-dependent demands accurate quantification and reporting of the NO levels released from such scaffolds to determine which formulations are most promising and suitable for specific therapeutic applications. Although a number of analytical methods are available to quantify NO, this review provides a comparison of the three most common techniques: Griess reaction,14, 15 chemiluminescence,14, 16 and electrochemistry.14, 17, 18 Equally important, we stress the need for reporting exogenous NO delivery with respect to the NO release vehicle (i.e., gas, NO donor, formulation) and amount (i.e., volume, mass, surface area). Careful and consistent reporting criteria are vital to both understanding and disseminating the concentration dependence of NO’s beneficial and detrimental influence on biology.3, 19–31

Many initial studies of NO’s importance to physiology have focused on exposing biological targets to different concentrations of NO and observing/noting changes to cellular activity. As shown in Table 1, these works have contributed to the realization that NO’s biological activity is concentration dependent.3 At low concentrations (< 1–30 nM), NO functions primarily through a cGMP-dependent pathway.19, 20 The activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) triggers a reaction cascade that ultimately results in the vasodilatory and angiogenic effects common to NO.20 As NO concentrations rise, NO induces phosphorylation of protein kinases that may subsequently initiate apoptosis protection.21–24 For example, phosphorylation of the pro-apoptotic protein Bad promotes its sequestration in the cytoplasm thereby preventing reaction with target genes in the nucleus and reducing the incidence of Bad-triggered apoptotic events.25 As NO concentrations approach 100 nM, tissue injury protection is also observed.26, 27 HIF-1α, a protein that mediates hypoxic effects on tissues, becomes stabilized and in turn regulates the effects of low oxygen concentration on vital cellular mechanisms.27 Whereas NO concentrations <100 nM result in protection against apoptosis, the effects of NO at concentrations >400 nM induce pro-apoptotic responses that are particularly important for antibacterial and anticancer applications.28 For example, phosphorylation of p53, a cell cycle regulator, occurs at elevated NO concentrations and results in protein activation and subsequent cell cycle arrest.28 Concentrations of NO approaching and exceeding 1 µM similarly result in apoptotic effects via protein nitrosation.29–31 In summary, low concentrations of NO have been linked to protective and anti-apoptotic action while larger NO concentrations often result in apoptosis and full cell cycle arrest.

Table 1.

Concentration dependence of NO’s cellular activity.

| Nitric Oxide Concentration | Signal Transduction Mechanism | Physiological Results | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 1 – 30 nM | Phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK) | Mediation of proliferative and protective effects | 3, 18,19 |

| 30 – 60 nM | Phosphorylation of Akt (protein kinases B) | Apoptosis protection | 3,20–24 |

| 100 nM | Stabilization of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) | Tissue injury protection | 3,25,26 |

| 400 nM | Phosphorylation and acetylation of p53 | Cytostatic to apoptotic responses, cell cycle arrest | 3,27 |

| > 1 µM | Protein nitrosation (poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase, caspases) | Apoptosis, full cell cycle arrest | 3, 28–30 |

2. Measuring Nitric Oxide

2.1 Challenges of Measuring NO

Understanding the effects of specific NO concentrations administered to physiological loci is crucial. However, NO’s rapid diffusion, high reactivity, and short half-life make accurate and precise measurements challenging.14 When NO is administered over a period of time, insight into both instantaneous NO concentrations and total amounts of NO delivered is required to properly evaluate the efficacy of NO as a therapeutic. Furthermore, the system in which NO measurements are performed must closely mimic the environment of the proposed application. For example, the amount of available NO released from a material in blood will be significantly lower than when the same material is placed in phosphate buffered saline. Additionally, only those NO-release triggers relevant to the intended application should be utilized as obviously the NO release mechanism will dictate NO flux and duration. For example, NO released from a nitrosothiol-based NO donor proposed for a systemic application should only be triggered by physiologically relevant conditions (e.g., 37 °C or glutathione, not light). Next, we introduce the three most popular analytical methods for measuring NO in biologically relevant media. Highlights of the basic methodology, limits of detection, detection ranges, and interferences associated with these measurement techniques are discussed to provide insight on the most ideal method for a particular NO release scaffold and/or application.

2.2 Griess Assay

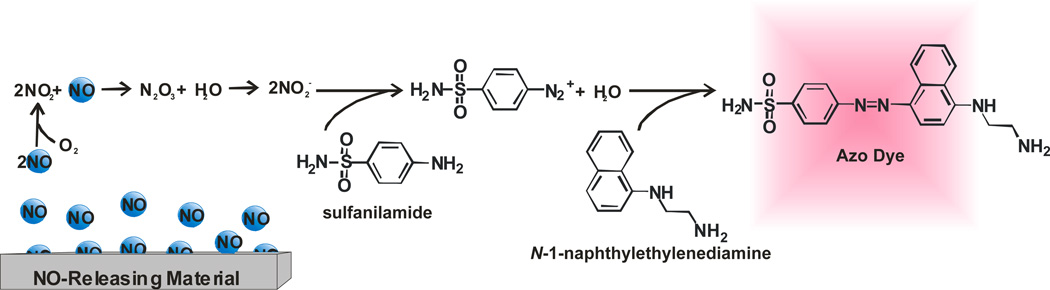

The Griess assay is the most popular method for the analysis of NO based on price (low cost), simple execution, and straightforward data analysis.14 First developed in 1879, the Griess assay measures NO indirectly as nitrite (NO2−), a product of NO’s autooxidation.32 As shown in Scheme 2, NO2− reacts with sulfanilamide to form a diazonium salt intermediate that subsequently reacts with N-(1-napthyl)ethylenediamine to form an azo dye. The formation of the azo dye is then monitored spectroscopically at 540 nm.

As shown in Figure 1, NO that is released from the sample is converted to NO2− that subsequently reacts with the Griess reagents (sulfanilamide and N-(1-napthyl)ethylenediamine). Following this reaction, the absorbance of the solution is measured and compared to the absorbance of similarly treated NO2− standards via a calibration curve. Of note, care should be taken to remove the scaffold or any other species from the analyte solution that may skew absorbance measurements. Assuming that NO2− was not formed as a byproduct during the synthesis/evaluation of a given NO-release scaffold, the NO2− concentration measured is proportional to the concentration of NO released. As such, solutions containing nitrite and/or materials that liberate nitrite and NO will result in erroneous data unless care is taken to resolve nitrite from NO. The limit of detection for commercially available Griess reagent kits is roughly 2.5 µM in ultrapure deionized distilled water.33 Unfortunately, the sensitivity of the Griess assay is highly dependent on solution composition (i.e., buffer and matrix), and thus often results in non-uniform dynamic ranges and varying limits of detection for different systems. Furthermore, the reaction of NO and oxygen may form other decomposition products such as nitrate (NO3−), resulting in superficially low NO values.34 Real-time analysis of NO generation using the Griess assay is not possible due to both the necessary chemical reactions and the indirect nature of detection. Despite such drawbacks, the commercial availability of reagent kits and the ability to employ high throughput 96-well microtiter plates make it a useful method for studying NO release. Nevertheless, care must be taken in reporting NO release using the Griess assay, particularly for quantitative work (e.g., correlating NO concentration and/or reaction kinetics to biological activity) since this assay will overestimate NO in the presence of nitrite and/or nitrite release.

Figure 1.

The reaction of nitrite (NO2−) with Griess assay reagents forms an azo dye that is easily detected spectrophotometrically to extrapolate NO concentrations released from the sample.

2.3 Chemiluminescence

Although more costly due to the required instrumentation and maintenance, NO analysis by chemiluminescence provides significantly more detailed information about NO release. In contrast to the Griess assay, NO is measured directly using chemiluminescence. Thus, precautions must be taken to minimize side reactions of NO before analysis as these will lead to artificially low concentrations. In particular, the system (i.e, media, flask) must be free of oxygen to reduce depletion of NO (via nitrogen dioxide formation) prior to analysis. After establishing an anaerobic environment, the NO-releasing material may then be introduced and monitored.

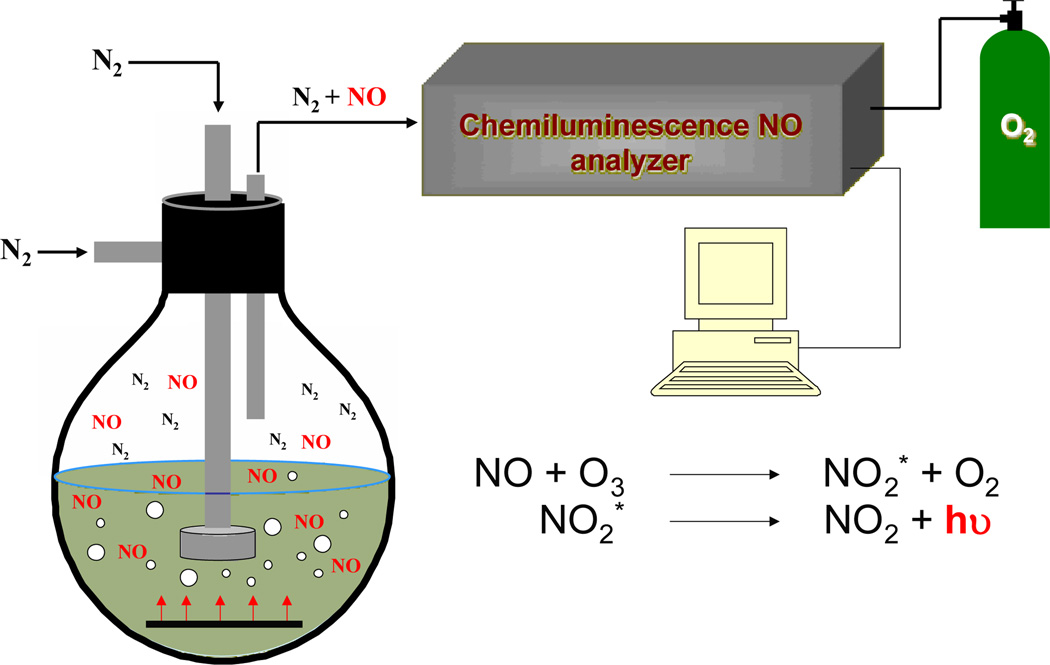

The NO that is produced or present is then carried by a continuously flowing stream of inert gas (i.e., nitrogen or argon) to a reaction cell within the chemiluminescence instrument (Figure 2). In the reaction cell, NO reacts with ozone that is generated in situ to form nitrogen dioxide in its excited state (NO2*). The subsequent decay of NO2* to its ground state results in the emission of a photon (between 600–875 nm) that is measured using a photomultiplier tube (PMT).16 In this respect, the analytical signal is proportional to the instantaneous concentration of NO.14, 16 Optical filters may be placed in front of the PMT to prevent interferences from other species that may react with ozone (e.g., ethylenes, carbonyls, sulfur compounds).16 The gas phase analysis requires the use of a carrier gas, which prevents the transfer of water soluble interferents including nitrite and nitrate that may be present in the sample flask. A standard calibration curve is constructed using a NO filter as a zero point and commercially available premixed nitric oxide gases of known concentrations. Of note, the method by which the calibration gases are introduced to the instrument should mimic the experimental setup as closely as possible. Commercially available chemiluminescence instruments offer numerous advantages for quantifying NO, including minimal response to interfering species, a wide dynamic linear range (typically 0.5 ppb to 500 ppm NO), and near real-time monitoring that is essential for assessing NO’s transient behavior.35 Of note, the NO levels measured are highly dependent on the system (vessel) configuration, flow rate (pressure) of the carrier gas, and deadspace between the sample and the reaction cell. Changes in these parameters during a given experiment will greatly influence the ensuing data particularly kinetics of NO release. Lastly, the system must be well sealed (i.e, free of leaks) to ensure all NO is carried to the analyzer.

Figure 2.

The detection of NO using chemiluminescence involves the reaction of NO with ozone (O3) to form NO2*. Upon relaxation to NO2, a photon is emitted, which is then detected and is proportional to the concentration of NO released from the sample.

2.4 Electrochemistry

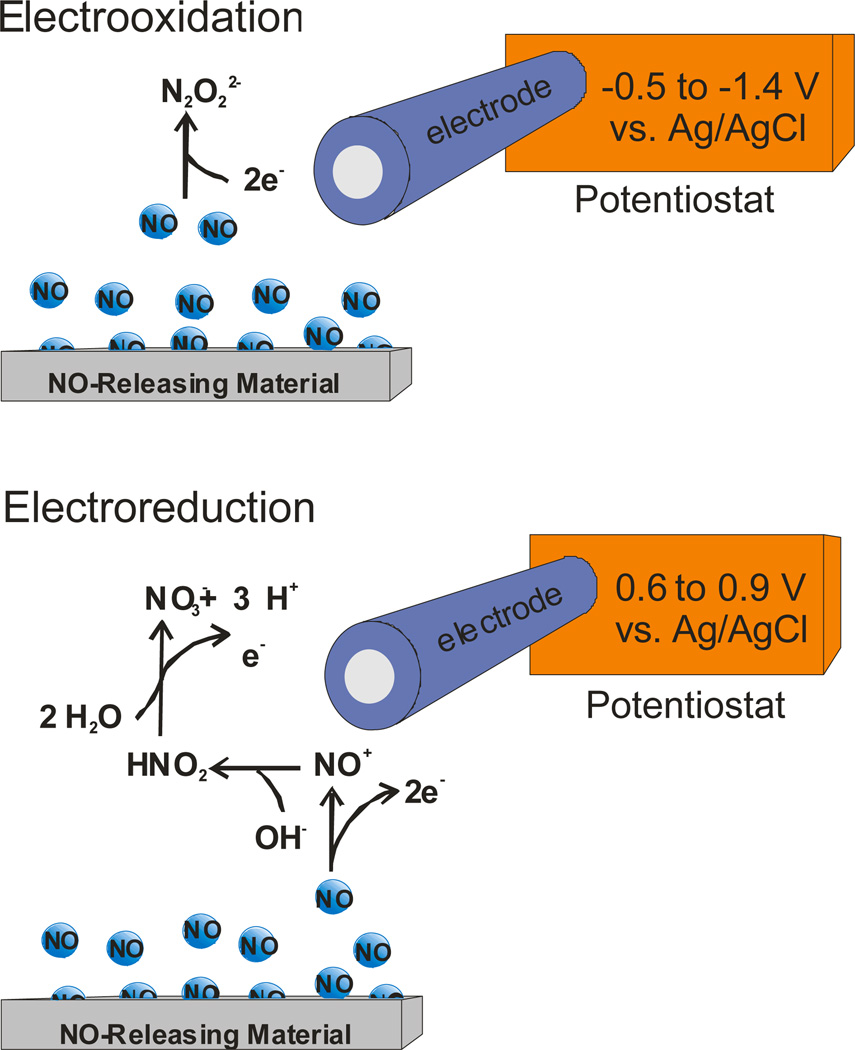

In contrast to chemiluminescence analysis, electrochemistry and more specifically the use of electrochemical sensors and related instrumentation are more economical, easily miniaturized, and capable of in situ NO analysis.18 As shown in Figure 3, the electrochemical detection of NO released from a sample may be carried out via either a two electron reduction of NO to N2O22− (at −0.5 to −1.4 V vs. Ag/AgCl)36 or the more commonly used three-step three-electron oxidation of NO to NO3− (at 0.6 to 0.9 V vs. Ag/AgCl).17 Current is measured and compared to a calibration curve to determine the concentration of NO.

Figure 3.

Electrochemical detection of NO can be achieved through the oxidation or reduction of NO.

While electroreduction is promising due to a decrease in the effect of interfering species, its utility is limited by poor sensitivity, oxygen interference, and diminished response at physiological pH.18 Alternatively, electrooxidation is characterized by enhanced sensitivity and utility at physiological pH and represents the preferred method of electrochemical NO detection despite interference from numerous biological species (i.e., carbon monoxide, acetaminophen, nitrite, dopamine).18 Selectivity over interfering species is often required when measuring small concentrations of NO and may be achieved by coating the electrode with a permselective polymer membrane. Nafion,37 polystyrene36 and (heptadecafluoro-1,1,2,2-tetrahydrodecyl)trimethoxysilane xerogel membranes38 have all been used as sensor membranes to enhance NO selectivity by decreasing/eliminating diffusion of ionic interferents through the membrane coating. Due to the wide variety of permselective polymers employed as NO sensor membranes, sensitivity for NO and selectivity over interfering species vary widely based on sensor design. To date, limits of detection for NO as low as 83 pM have been reported with dynamic linear ranges of 0.2 nM – 4.0 µM.38 The ability of these sensor platforms to be miniaturized and used for real-time measurements in biological milieu represents a significant advantage for using electrochemistry over alternative methods of NO detection. Furthermore, the small size of many NO sensor platforms allows for detection at/near the NO source, minimizing analyte loss due NO’s inherent reactivity.18 Although long-term sensor performance is often compromised in complex environments (i.e., in situ or in vivo), sensors are generally affordable and thus electrochemical detection remains a popular method for NO analysis.

3. Reporting Nitric Oxide Release

The formulation and investigation of potential NO-release scaffolds as therapeutics have increased due to the physiological and medicinal effects attributed to NO. The range of biomedical applications for NO may necessitate multiple formulations including gaseous NO, low molecular weight molecules, and macromolecular particles, gels and coatings. For example, polymeric device coatings capable of releasing NO in a controlled manner have been shown to decrease bacterial infection and improve tissue integration and/or blood compatibility for subcutaneous glucose sensors,7, 39 orthopedic devices,40, 41 and vascular stents.42 Macromolecular NO release scaffolds are also being developed as stand-alone therapeutics against pathogens43, 44 and cancer,10 with much of their efficacy related to their ability to deliver large NO payloads directly to cells. Due to the assorted methods for measuring NO and the related diverse data, direct comparison across NO release scaffold types is both challenging and important. Unfortunately, reports of NO release characteristics often do not contain sufficient information for understanding and comparing therapeutic efficacy. The rate of release, NO flux, release duration, and release half-life all represent essential parameters for describing a NO source. Furthermore, NO release characteristics must be normalized to the amount/volume of the source (e.g., scaffold) for accurate representation of therapeutic efficacy.

3.1 Surface-generated NO Release

The release of NO from a surface is attractive for antibacterial and antithrombic applications. For example, NO-releasing coatings on medical implants may prevent infection and device-induced thrombosis/restenosis (as discussed in Nitric Oxide Release Part II. Therapeutic Applications). Depending on the characteristics of the implant, surface-generated NO may be achieved by various means including self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) of NO donors on metal and silica surfaces45, 46 or the casting of thin polymer films on substrates.8, 47, 48 The thickness of a coating will impact NO release duration and flux; it is thus essential to report the total amount of material deposited on the substrate or device used for analysis. The total NO release ([NO]T) must then be normalized per unit mass of the material deposited (mol NO mg−1) and per unit area (mol NO cm−2) of the coated material.

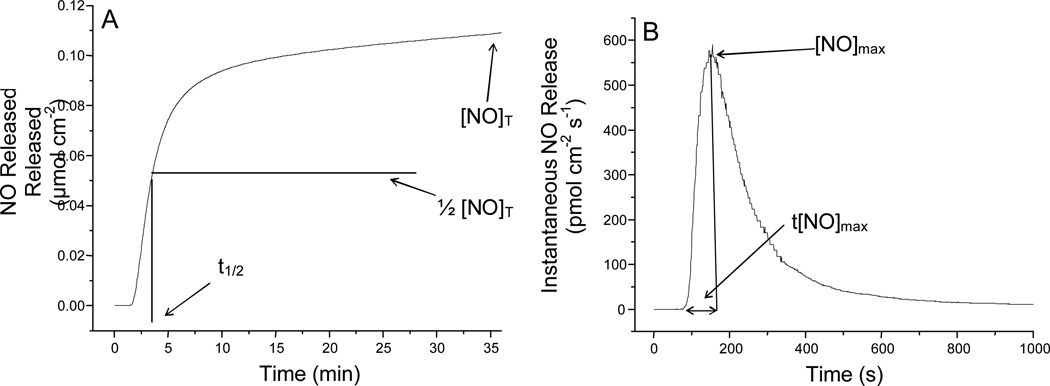

Other parameters that should be used to characterize NO release include the duration (td) and half-life of release (t1/2) to indicate the period over which the scaffold actively releases NO (Figure 4A). In addition to [NO]T and td, the amounts of NO released at specific times within the lifetime of the NO-releasing polymer are arguably the most important NO release parameters due to the rapid reactivity and paradoxical effects that high and low local concentrations of NO elicit.49 As shown in Figure 4B, instantaneous levels of NO generated from a surface including the maximum instantaneous NO release ([NO]max), should also be normalized both per unit mass (mol NO mg−1 sec−1) of the scaffold and per unit area of the substrate (mol NO cm−2 sec−1), as both are influenced by substrate size and coating thickness.

Figure 4.

Graphical representation of (A) total NO release from a surface including designations for total NO release ([NO]T) and half life of NO release (t1/2) and (B) instantaneous NO release from a surface with maximum NO flux ([NO]max) and the time to [NO]max (t[NO]max) indicated.

While the indirect nature of the Griess assay makes accurate quantification of instantaneous levels of NO difficult compared to chemiluminescence and electrochemistry, mathematical modeling (i.e., curve fitting and integration) can allow for average NO flux values to be calculated over extended period.33 Electrochemical detection of NO from a surface may be complicated due to the spatial dependence of the sensor in relation to the NO-releasing material. Maintaining consistent electrode-to-material distances are thus crucial for reproducible and comparable measurements. Although often difficult to measure, the surface flux of NO at any given time is important for the determination of potential side effects (e.g., cytotoxicity to healthy cells) that may be caused by high concentrations of localized NO release (e.g., at the [NO]max). Furthermore, NO fluxes are paramount to determining the lifetime of therapeutic utility as NO release thresholds have been determined for many of NO’s physiological effects. For example, fluxes >21 pmol cm−2 s−1 have been found necessary to reduce bacterial adhesion. In turn, materials proposed for antimicrobial applications must be characterized with surface fluxes at or above this level.12 Intermittent flux values (mol NO cm−2 sec−1 vs. time) and durations that a material is capable of releasing NO above levels relevant to the proposed application should be determined to provide the greatest insight into the temporal behavior of the therapeutic material.

3.2 Molecular/particulate NO Release

The use of small molecule and nanomaterial-based NO release vehicles to modulate cellular activity has generated considerable interest about NO’s therapeutic action from a pharmacological standpoint. Several research groups have created NO-release scaffolds capable of delivering NO to specific locations such as tumors and infections. Small molecules,50, 51 dendrimers,52, 53 proteins,4 gold monolayer protected clusters,5, 54 and silica nanoparticles6, 55–57 have been investigated as potential NO-donor scaffolds (see Nitric Oxide Release Part I: Macromolecular Scaffolds). Whereas surface generated NO is normalized per area, molecular/particulate NO release quantification should be normalized per unit mass of the material administered for all necessary characteristics including total NO released (e.g., mol NO mg−1) and temporal characteristics (e.g., mol NO mg−1 sec−1) such as the maximum NO release level. Since many applications of NO-releasing nanotherapeutics are analogous to current medicines, this representation of activity is essential in order to draw comparisons between drugs with different mechanisms of action. The NO-release half-life and duration of NO release are once again essential parameters to be reported because NO donors are capable of releasing NO over wide concentrations and durations.

3.3 Gaseous NO

Nitric oxide’s delivery from a gas cylinder has limited utility/application relative to NO delivered from macromolecular scaffolds.58, 59 Nevertheless, inhalation of gaseous NO can be used to selectively induce vasodilation of pulmonary areas whereas circulating NO prodrugs produce systemic vasodilation and hypotension effects.60, 61 Treating chronic wounds with gaseous NO has also been investigated as a strategy to reduce infection and enhance wound healing.11, 62

With respect to measuring gaseous NO, chemiluminescent detection is clearly the most ideal method as the NO analysis is conducted in the gas phase.16, 35 The dose is reported as ppm or ppb. The gaseous concentration administered, the duration of exposure, and the observed effects (e.g., wound closure time, toxicity) are parameters required to study/compare NO’s biological action. Of note, the comparison of gaseous NO and macromolecular NO donors with respect to concentrations and pharmacological efficacy is challenging due to delivery/exposure means (gas versus solution) and reaction kinetics.59

4. Conclusion

While the potential of NO release as a therapy is becoming more clear, irregular reporting of NO-release parameters continues to limit the development of NO-based therapeutics because comparisons between reports is difficult. Thorough analysis and reporting of NO-release characteristics of proposed therapeutics must remain at the forefront of NO efficacy studies. Although a number of sensitive methods exist for the quantification of NO, both their selection and the ensuing data collection/analysis require careful consideration depending on the NO source and biological matrix. Nitric oxide release characteristics including [NO]T, td, and instantaneous concentrations (e.g., NO flux) must be normalized by the amount (e.g., mass or surface area) of material employed to have relevance regarding NO’s efficacy for a particular condition. As research laboratories inherently utilize distinct NO analysis methods due to availability, expense, and area of study, NO release must be represented using standard conventions to allow for comparison of NO payloads and therapeutic activity between NO scaffolds. Furthermore, the actual NO levels achieved within a biological system (e.g., cell or tissue) should be addressed and may require tools not described herein such as molecular probes and/or ultramicroelectrodes.14

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from National Institute of Health (EB000708).

Biographies

Peter N. Coneski earned his PhD in Chemistry from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2010. His dissertation research was focused on the design, synthesis, and characterization of nitric oxide-releasing polymeric materials. He is currently an American Society for Engineering Education Postdoctoral Fellow at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory in the Materials Chemistry Branch working on biodegradable polymers, antifouling materials and hybrid organic/inorganic composites.

Mark Schoenfisch is a Professor of Chemistry in the Department of Chemistry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-Chapel Hill). Dr. Schoenfisch received undergraduate degrees in Chemistry (BA) and Germanic Languages and Literature (BA) at the University of Kansas prior to attending the University of Arizona for graduate studies in Chemistry (PhD). Before starting at UNC-Chapel Hill, he spent two years as a National Institutes of Health Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Michigan. His research interests include analytical sensors, biomaterials, and the development of nitric oxide release scaffolds as new therapeutics.

References

- 1.Schulz R, Rassaf T, Massion PB, Kelm M, Balligand J-L. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2005;108:225–256. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu VWT, Huang PL. Cardiovascular Research. 2008;77:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas DD, Ridnour LA, Isenberg JS, Flores-Santana W, Switzer CH, Donzelli S, Hussain P, Vecoli C, Paolocci N, Ambs S, Colton CA, Harris CC, Roberts DD, Wink DA. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2008;45:18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hrabie JA, Saavedra JE, Roller PP, Southan GJ, Keefer LK. Bioconjugate Chemistry. 1999;10:838–842. doi: 10.1021/bc990035s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polizzi MA, Stasko NA, Schoenfisch MH. Langmuir. 2007;23:4938–4943. doi: 10.1021/la0633841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shin JH, Metzger SK, Schoenfisch MH. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129:4612–4619. doi: 10.1021/ja0674338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoenfisch MH, Rothrock AR, Shin JH, Polizzi MA, Brinkley MF, Dobmeier KP. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 2006;22:306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou Z, Meyerhoff ME. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:780–789. doi: 10.1021/bm049462l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Archer SL, Huang JMC, Hampl V, Nelson DP, Shultz PJ, Weir EK. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1994;91:7583–7587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mocellin S, Bronte V, Nitti D. Medicinal Research Reviews. 2006;27:317–352. doi: 10.1002/med.20092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghaffari A, Miller CC, McMullin B, Ghahary A. Nitric Oxide. 2006;14:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hetrick EM, Schoenfisch MH. Biomaterials. 2007;28:1948–1956. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Witte MB, Barbul A. The American Journal of Surgery. 2002;183:406–412. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00815-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hetrick EM, Schoenfisch MH. Annual Reviews of Analytical Chemistry. 2009;2:409–433. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anchem-060908-155146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsikas D. Journal of Chromatography B. 2007;851:51–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bates JN. Neuroprotocols. 1992;1:141–149. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bedioui F, Villeneuve N. Electroanalysis. 2003;15:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Privett BJ, Shin JH, Schoenfisch MH. Chemical Society Reviews. 2010;39:1925–1935. doi: 10.1039/b701906h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas DD, Espey MG, Ridnour LA, Hofseth LJ, Mancardi D, Harris CC, Wink DA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101:8894–8899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400453101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas DD, Ridnour LA, Espey MG, Donzelli S, Ambs S, Hussain SP, Harris CC, DeGraff W, Roberts DD, Mitchell JB, Wink DA. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:25984–25993. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602242200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prueitt RL, Boersma BJ, Howe TM, Goodman JE, Thomas DD, Ying L, Pfiester CM, Yfantis HG, Cottrell JR, Lee DH, Remaley AT, Hofseth LJ, Wink DA, Ambs S. International Journal of Cancer. 2007;120:796–805. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pervin S, Singh R, Hernandez E, Wu G, Chaudhuri G. Cancer Research. 2007;67:289–299. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pervin S, Singh R, Freije WA, Chaudhuri G. Cancer Research. 2003;63:8853–8860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pervin S, Singh R, Chaudhuri G. Cancer Research. 2003;63:5470–5479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chong ZZ, Li F, Maiese K. Histology and Histopathology. 2005;20:299–315. doi: 10.14670/hh-20.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brahimi-Horn MC, Pouyssegur J. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2007;73:450–457. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paul SA, Simons JW, Mabjeesh NJ. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2004;200:20–30. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hussain SP, Hofseth LJ, Harris CC. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2003;3:276–285. doi: 10.1038/nrc1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ridnour LA, Thomas DD, Mancardi D, Espey MG, Miranda KM, Paolocci N, Feelisch M, Fukuto J, Wink DA. Biological Chemistry. 2004;385:1–10. doi: 10.1515/BC.2004.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cleeter MW, Cooper JM, Darley-Usmar VM, Moncada S, Schapira AH. FEBS Letters. 1994;345:50–54. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00424-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borutaite V, Brown GC. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2006;1757:562–566. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Griess P. Chemische Berichte. 1879;12:426–428. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Promega Corporation. Griess Reagent System Technical Bulletin, TB229. 2010 http://www.promega.com/tbs/tb229/tb229.pdf.

- 34.Tracey WR. Neuroprotocols. 1992;1 [Google Scholar]

- 35.General Electric Company. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kitamura Y, Uzawa T, Oka K, Komai Y, Ogawa H, Takizawa N, Kobayashi H, Tanashita K. Analytical Chemistry. 2000;72:2957–2962. doi: 10.1021/ac000165q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bedioui F, Trevin S, Devynck J. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry. 1994;377:295–298. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shin JH, Privett BJ, Kita JM, Wightman RM, Schoenfisch MH. Analytical Chemistry. 2008;80:6850–6859. doi: 10.1021/ac800185x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin JH, Marxer SM, Schoenfisch MH. Analytical Chemistry. 2004;76:4543–4549. doi: 10.1021/ac049776z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mowery KA, Schoenfisch MH, Saavedra JE, Keefer LK, Meyerhoff ME. Biomaterials. 2000;21:9–21. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hetrick EM, Prichard HL, Klitzman B, Schoenfisch MH. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4571–4580. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou Z, Meyerhoff ME. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6506–6517. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deupree SM, Schoenfisch MH. Acta Biomaterialia. 2009;5:1405–1415. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hetrick EM, Shin JH, Paul HS, Schoenfisch MH. Biomaterials. 2009;30:2782–2789. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.01.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Etchenique R, Furman M, Olabe JA. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2000;122:3967–3968. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sortino S, Petralia S, Compagnini G, Conoci S, Condorelli G. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2002;41:1914–1917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marxer SM, Rothrock AR, Nablo BJ, Robbins ME, Schoenfisch MH. Chemistry of Materials. 2003;15:4193–4199. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Riccio DA, Dobmeier KP, Hetrick EM, Privett BJ, Paul HS, Schoenfisch MH. Biomaterials. 2009;30:4494–4502. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lancaster JR. Nitric Oxide. 1997;1:18–30. doi: 10.1006/niox.1996.0112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Keefer LK, Nims RW, Davies KM, Wink DA. Methods in Enzymology. 1996;268:281–293. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)68030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miller MR, Megson IL. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2007;151:305–321. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stasko NA, Schoenfisch MH. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128:8265–8271. doi: 10.1021/ja060875z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stasko NA, Fischer TH, Schoenfisch MH. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:834–841. doi: 10.1021/bm7011746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rothrock AR, Donkers RL, Schoenfisch MH. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2005;127:9362–9363. doi: 10.1021/ja052027u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang H, Annich GM, Miskulin J, Stankiewicz K, Osterholzer K, Merz SI, Bartlett RH, Meyerhoff ME. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003;125:5015–5024. doi: 10.1021/ja0291538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shin JH, Schoenfisch MH. Chemistry of Materials. 2008;20:239–249. doi: 10.1021/cm702526q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carpenter AW, Slomberg DL, Rao KS, Schoenfisch MH. ACS Nano. 2011 doi: 10.1021/nn202054f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scatena R, Bottoni P, Pontoglio A, Giardina B. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2010;17:61–73. doi: 10.2174/092986710789957841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nakao A, Sugimoto R, Billiar TR, McCurry KR. Journal of Clinical Biochemistry and Nutrition. 2009;44:1–13. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.08-193R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Radermacher P, Santak B, Wust HJ, Tarnow J, Falke KJ. Anesthesiology. 1990;72:238–244. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199002000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fratacci MD, Frostell CG, Chen TY, Wain JC, Robinson DR, Zapol WM. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:990–999. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199112000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miller CC, Miller MK, Ghaffari A, Kunimoto B. Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 2004;8:233–238. doi: 10.1007/s10227-004-0106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]