Abstract

The oxidized glutathione mimetic NOV-002, is a unique anti-tumor agent that not only has the ability to inhibit tumor cell proliferation, survival, and invasion, but in some settings can also ameliorate cytotoxic chemotherapy-induced hematopoietic and immune suppression. However, the mechanisms by which NOV-002 protects the hematopoietic and immune systems against the cytoxic effects of chemotherapy are not known. Therefore, in the present study we investigated the mechanisms of action of NOV-002 using a mouse model in which hematopoietic and immune suppression was induced by cyclophosphamide (CTX) treatment. We found that NOV-002 treatment in a clinically comparable dose regimen attenuated CTX-induced reduction in bone marrow hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs), and reversed the immunosuppressive activity of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), which led to a significant improvement in hematopoietic and immune functions. These effects of NOV-002 may be attributable to its ability to modulate cellular redox. This suggestion is supported by the finding that NOV-002 treatment upregulated the expression of superoxide dismutase 3 and glutathione peroxidase 2 in HSPCs; inhibited CTX-induced increases in reactive oxygen species production in HSPCs and MDSCs; and attenuated CTX-induced reduction of the ratio of reduced glutathione (GSH) to oxidized glutathione (GSSG) in splenocytes. These findings provide a better understanding of the mechanisms whereby NOV-002 modulates chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression and immune dysfunction, and a stronger rationale for clinical utilization of NOV-002 has the potential to be utilized to reduce chemotherapy-induced hematopoietic and immune suppression.

INTRODUCTION

Many cancer patients receiving chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy develop hematopoietic and immune suppression that can lead to dose reductions and delays in therapy [1–4]. Dose reductions and treatment delays can compromise the outcomes of cancer therapy and decrease overall survival and disease-free survival [1, 4–7]. However, strategies to effectively reduce the undesirable collateral effects of these therapies, and accelerate the recovery of depressed hematopoietic and immune functions after chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy remains a major clinical problem.

An increasing body of evidence suggests that chemotherapy and radiation impair hematopoietic and immune functions not only by causing direct damage to DNA but also via increasing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [8–12]. Increases in ROS production in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) can lead to bone marrow (BM) suppression through induction of HSPC apoptosis and senescence. The later effect is primarily attributed to ROS-mediated stimulation of HSPC cycling and activation of the p38-p16 senescent pathway [13–20]. In addition, increased production of ROS is one of the key mechanisms by which myeloid derived suppressive cells (MDSCs) inhibit various immune functions [21–30]. Therefore, antioxidant therapy has been proposed to have the potential to reduce chemotherapy and radiation-induced hematopoietic and immune suppression. However, its use has been limited because of concerns that antioxidants can also compromise tumor cell response to chemotherapy and radiation.

NOV-002 is the oxidized form of glutathione disulfide (GSSG) that has exhibited significant anticancer activity when combined with cytotoxic chemotherapy (Figure 1A) [31–36]. Interestingly, clinical and preclinical data also suggests that the addition of NOV-002 can reduce chemotherapy-induced hematologic toxicity and immune suppression [34, 36]. Because of its potential hematopoietic promoting and immunomodulatory activities, it has been suggested that NOV-002 may be particularly useful in combination with certain hematopoietic and immune suppressive chemotherapy agents such as cyclophosphamide (CTX) to treat cancer patients [36].

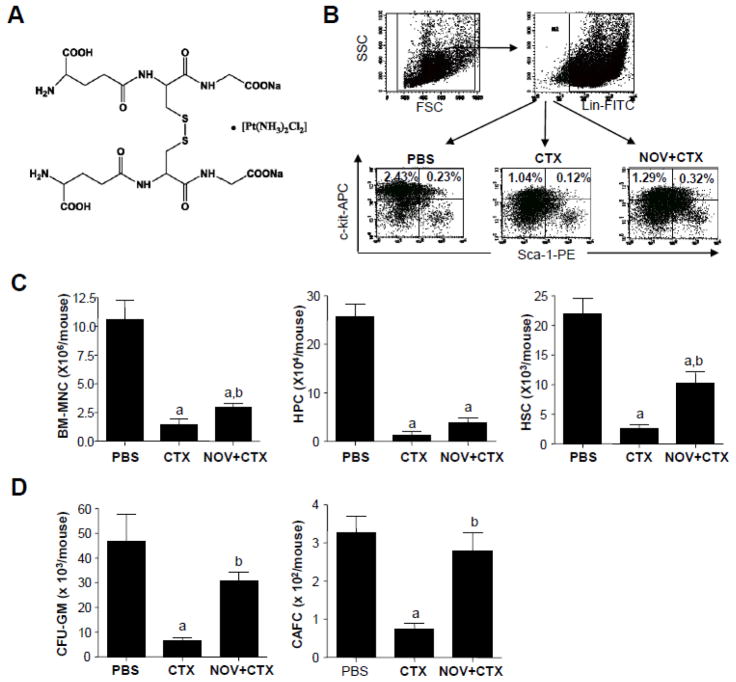

Figure 1. NOV-002 reduces CTX-induced myeloid suppression.

Mice were treated with vehicle (PBS), CTX alone (CTX) or CTX plus NOV-002 (NOV+CTX). Three days after the treatment(s), BM cells were harvested for analyses of numbers and functions of HPCs and HSCs by flow cytometry and CFC and CAFC assays, respectively. A. Structure of NOV-002. B. Representative gating strategies for the analyses of HPCs (Lin−, c-Kit+, Sca-1−) and HSCs (Lin−, c-Kit+, Sca-1+) in BM-MNCs by flow cytometry. The numbers presented in the flow charts are the frequencies (%) of each cell population. C. Average numbers of BM-MNCs, HPCs, and HSCs in each mouse. D. Average numbers of CFU-GMs and day-35 CAFCs in each mouse. The data are presented as mean ± SDEV of 4 to 5 independent experiments. a, p<0.05 vs. PBS; b, p<0.05 vs. CTX.

However, the mechanisms of action of NOV-002 in modulating the responses of the hematopoietic and immune systems to chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy have not been well characterized. It has been suggested that the pharmacologic effects of NOV-002 may be attributable to the modulation of cellular redox through its GSSG component [33, 35, 36]. Such modulation may underlie its clinical actions, including promotion of hematologic recovery and immunostimulation in the face of chemotherapy-induced hematopoietic and immune dysfunction that have been observed in some earlier studies [33, 35, 36]. To test this hypothesis, we examined the effects of NOV-002 on CTX-induced hematopoietic toxicity and immune suppression in a mouse model. Our results showed that NOV-002 treatment induced the expression of superoxide dismutase (SOD) 3 and glutathione peroxidase (GPX) 2 in HSPCs, inhibited CTX-induced increases in ROS production in HSPCs and MDSCs, and attenuated CTX-induced reduction of the ratio of reduced to oxidized glutathione in the spleen. These effects led to a significant improvement in hematopoietic and immune functions. These findings provide a better understanding of the mechanisms of action of NOV-002 in modulating chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression and immune dysfunction and provide a rationale of further clinical study of NOV-002 to promote BM recovery and enhance immunity during cytotoxic chemotherapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Male C57BL/6 (Ly5.2) mice were purchased from The Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Mice were housed 4 in a cage and received food and water ad libitum. All mice were used at approximately 8 - 12 weeks of age. They were divided into three groups with a minimal of three to five mice per group: control, CTX, and NOV-002 plus CTX (NOV-002 +CTX). Control mice were treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) only; CTX mice were given an intraperitoneal (ip) injection of CTX (200 mg/kg, from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) on day 0; and NOV-002 plus CTX mice were treated with up to 7 consecutive daily ip injections of 25 mg/kg of NOV-002 (Novelos Therapeutics, Newton, MA) starting on the day prior to CTX. At days 3 and 7 after CTX treatment, mice were euthanized with CO2 and by cervical dislocation for the collection of BM cells as described below. Pmel-1 transgenic (Ly5.2) mice originally obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine) were bred in the AAALAC-certified animal facility of the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC). T cells from Pmel-1 transgenic mice express the Vα1/Vβ13 T cell receptor (TCR) specifically recognize the H-2Db-restricted human gp10025–33 epitope (KVPRNQDWL: gp10025–33). This peptide represents an altered form of the murine gp10025–33 (EGSRNQDWL) with improved binding to the MHC class-I. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of MUSC and the University of Miami approved all experimental procedures used in this study.

Isolation of bone marrow mononuclear cells (BM-MNCs) and preparation of splenocytes

The femora and tibiae were harvested from the mice immediately after they were euthanized. BM cells were flushed from the bones into Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 2% fetal calf serum (FCS) using a 21-gauge needle and a 5-ml syringe. Cells from three to five mice were pooled to obtain sufficient number of cells and centrifuged through Histopaque 1083 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to isolate BM-MNCs. Spleen single-cell suspensions were prepared as previously described [20., 37]

Quantitative analysis of BM hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs)

Briefly, 1×106 BM-MNC were incubated with biotin-conjugated rat antibodies against CD3ε, CD45R/B220, Gr-1, Mac-1 and Ter-119 and then with streptavidin-FITC. After incubation with anti-CD16/CD32 antibody, they were stained with anti-Sca-1-PE and anti-c-kit-APC antibodies. All these antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA). Lin−c-kit+sca1+ cells represent enriched HSCs and lin−c-kit+sca1− cells are HPCs. For each sample, a minimum of 200,000 cells were analyzed on a FACS Caliber (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA), and the data were analyzed using the CellQuest software (BectonDickinson) after gating on viable cells.

Colony forming cell (CFC) assay

Colony forming unit-granulocyte macrophage (CFU-GM) was analyzed by CFC assay to measure HPC function. Briefly, BM-MNCs were suspended in MethocultM3434 medium (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC) at 2 × 104 viable cells/mL and seeded in wells of 24-well plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 in air for 7 days. Colonies of 50 or more cells were scored under an inverted microscope.

Cobblestone area-forming cell (CAFC) assay

The CAFC assay was done according to the procedures developed by Pleomacher et al. with modifications as we previously reported [37–39]. Briefly, stromal layers were prepared by seeding 103/well FBMD-1 stromal cells to wells of flat-bottom 96-well plates (Falcon, Lincoln Park, NJ). One week later, BM-MNC were overlaid on these stromal layers in 6 dilutions, 3-fold apart, and consisting of 20 wells per dilution to allow limiting dilution analysis of the precursor cells forming hematopoietic clones under the stromal layer. Cultures were fed weekly by changing half of the medium. The frequencies of CAFCs were determined at 35 days of culture to measure the clonogenic function of HSCs as previously described [37–39].

Analysis of the frequencies of erythroid progenitors in BM-MNCs by flow cytometry

Briefly, 1×106 BM-MNCs were incubated with anti-CD16/CD32 antibody (BD Biosciences) to block antibody nonspecific bindings. The cells were then stained with PE-conjugated Ter-199 antibody (BD Biosciences) to label erythroid progenitors. Phenotypic analysis of erythroid progenitors was performed using a FACS Caliber (Becton Dickinson) and the data were analyzed using the CellQuest software (BectonDickinson) after gating on viable cells.

Analysis of ROS production in BM HSPCs

BM lineage negative hematopoietic cells (Lin− cells) were isolated as described previously [8, 9]. Lin− cells (1 × 106/ml) stained with anti-Sca-1-PE and anti-c-Kit-APC antibodies were suspended in PBS supplemented with 5 mM glucose, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgSO4 and 5 mg/ml BSA and then incubated with CM-H2DCFDA (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) (10 μM) for 30 minutes at 37°C. The levels of ROS in Lin− cells, HPCs, and HSCs were analyzed by measuring the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) using a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson). For each sample, a minimum of 200,000 Lin− cells was acquired and the data were analyzed using CellQuest software (Becton-Dickinson). In all experiments, PE and APC isotype controls and other positive and negative controls were included as appropriate.

Analysis of the frequencies of MDSCs in peripheral blood and the spleen by flow cytometry

Peripheral blood and cell suspensions from spleens were incubated with APC-conjugated anti-CD11b and PE-conjugated anti-Ly6G antibodies (BD Biosciences). Percentage of double positive cell populations was determined using a FACS Calibur flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson). For each sample, a minimum of 200,000 events were acquired and the data were analyzed using CellQuest software (Becton-Dickinson).

In vitro T cell suppression assay

Splenocytes were incubated with APC-conjugated anti-CD11b and PE-conjugated anti-Ly6G antibodies (BD Biosciences). CD11b+Ly6G+ MDSCs were isolated by cell sorting using an Aria cell sorter (BD Biosciences). CD3+ T cells were isolated using magnetic beads (BD Biosciences) following manufacturer’s instructions. MDSCs and T cells were co-cultured at the indicated ratios and stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 coated beads (BD Biosciences) at 1:1 bead to T cell ratio. Five days after culture, cells were pulsed with 3H-thymidine overnight and the incorporation of 3H-thymidine was determined by a scintillation counter. Percentage suppression of T cell proliferation was calculated as: CPM from wells containing MDSCs x 100/CPM from wells without MDSCs.

In vivo T cell suppression assay

C57BL/6 mice (Ly5.2+) were treated with PBS, CTX, or NOV-002 and CTX as described previously. At day seven after CTX injection mice were adoptively transferred with 1×107 splenocytes from Pmel mice (Ly5.1+). Recipient mice were vaccinated with 100 μg of mouse gp10025–33 melanoma peptide24 hrs after the cell transfer. The frequencies of transferred Pmel T cells were determined 3 days after vaccination by flow cytometry to detect Ly5.1+ donor T cells.

Analysis of ROS production in MDSCs

Briefly, BM cells were incubated at 37°C in the presence of 5μM CM-H2DCFDA for 30 min after immunostaining with APC-conjugated anti-CD11b and PE-conjugated anti-Ly6G antibodies (BD Biosciences). For induced activation, cells were cultured simultaneously with CM-H2DCFDA and 30 ng/mL phorbolmyristate acetate (PMA, from Sigma-Aldrich). Analysis of ROS production in CD11b+Ly6G+ MDSCs was then conducted by flow cytometry as described above.

Analysis of GSH/GSSG ratio

Spleen sections from the same mice were cryopreserved in PBS (GSH sample) or in 30 μl of scavenger solution (GSSG sample) (Oxford Biomedical Research, Oxford, MI). The amounts of GSH and GSSG were assayed using a microplate assay kit (Oxford Biomedical Research, Oxford, MI) after thawing and deproteination with a 5% metaphosphoric acid solution. Concentrations of GSH and GSSG were extrapolated from a calibration curve and the ratio was calculated as follows: Ratio = GSHt – 2GSSG/GSSG.

Analysis of mRNA expression of antioxidant enzymes in HSPCs by real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from purified HSPCs (Lin−c-kit+sca1+ cells) using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Sciences, Germantown, MD) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA using Super Script II first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen) as we previously described. PCR primers for SOD1, SOD2, SOD3, catalase, GPX1, GPX2, peroxiredoxin (PRDX) 1, PRDX2, and thioredoxin reductase (TXNRD) 1 were customer-designed and obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA) and the sequences of the primers are listed in Table 1. The threshold cycle (Ct) value for each gene was normalized to the Ct value of glyceraldehyde 3 phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). The relative mRNA expression was calculated using the comparative CT (2−ΔΔCt) method.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for real time RT-PCR

| GENE | GeneBank® Accession Number | Sequences of Ologonucleotide Primers |

|---|---|---|

| SOD1 | NM_011434 | S: 5′-GTATGGGGACAATACACAAGGCTGTAC-3′ A: 5′-AATGCTCTCCTGAGAGTGAGATCACAC-3′ |

| SOD2 | NM_013671 | S: 5′-CACATTAACGCGCAGATCATGCAG-3′ A: 5′-ACCTGAGTTGTAACATCTCCCTTG-3′ |

| SOD3 | NM_011435 | S: 5′-ATGGAGCTAGGACGACGAAGGGAG-3′ A: 5′-AGACTGAAATAGGCCTCAAGCCTG-3′ |

| Catalase | NM_009804 | S: 5′-TGCAAGTTCCATTACAAGACCGACCAG-3′ A: 5′-ACGTCCAGGACGGGTAATTGCCATTGG-3′ |

| GPX1 | NM_008160 | S: 5′-TCAGTTCGGACACCAGGAGAATGG-3′ A: 5′-CACTGGGTGTTGGCAAGGCATTCC-3′ |

| GPX2 | NM_030677 | S: 5′-AACCAGTTCGGACATCAGGAGAAC-3′ A: 5′-GGCAAAGACAGGATGCTCGTTCTG-3′ |

| PRDX1 | NM_011034 | S: 5′-GTCATCTGGCATGGATTAACACAC-3′ A: 5′-CCCTGAAAGAGATACCTTCATCAG-3′ |

| PRDX2 | NM_011563 | S: 5′-CACCCACCTGGCGTGGATCAATAC-3′ A: 5′-AAAGAGACCCCTGTAAGCAATGCC-3′ |

| TXNRD1 | NM_001042513 | S: 5′-CCTCTTGGGACCAGATGGGGTCTC-3′ A: 5′-CCAGTCATGCTTCACTGTGTCTTC-3′ |

| HPRT | NM_013556 | S: 5′-AGCAGTACAGCCCCAAAATGGTTA-3′ A: 5′-TCAAGGGCATATCCAACAACAAAC-3′ |

S, Sense; A, Antisense

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using two-sided t test and non parametric Mann-Whitney U test. Differences were considered significant at p<0.05. All of these analyses were done using GraphPad Prism from GraphPad Software, Inc. (San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

NOV-002 reduces CTX-induced myelosuppression by protecting HSPCs

To elucidate the mechanisms by which NOV-002 reduces chemotherapy-induced BM toxicity, we first examined the effects of NOV-002 treatment on CTX-induced myelosuppression using a murine model. In this model, mice were given a single dose of CTX with or without daily NOV-002 injections starting on the day prior to chemotherapy. This daily regimen closely resembles the dosing schedule of NOV-002 utilized in clinical trials. On day 3 after CTX treatment, mice were sacrificed for harvesting BM cells. The frequencies of HSCs (lin−c-kit+sca1+ cells) and HPCs (lin−c-kit+sca1− cells) in BM-MNCs were analyzed by flow cytometry (Figure 1B). The number of these cells was calculated according to the total number of BM-MNCs and averaged for each mouse in the same treatment groups. An initial experiment showed that mice treated with NOV-002 alone did not exhibit any significant changes in various BM indices compared with vehicle-treated controls (data not shown). Therefore, in the subsequent experiments, this group was omitted from the study. As shown in Figure 1C, treatment with CTX resulted in a significant reduction in the number of BM-MNCs, HPCs, and HSCs. This reduction was attenuated by treatment with NOV-002. To test if the clonogenic function of HPCs and HSCs can also be protected by NOV-002 treatment, we performed CFU-GM and CAFC assays, respectively. In concordance with our previous findings, CTX significantly reduced the clonogenic function of both HPCs and HSCs [9]. However, daily NOV-002 injections resulted in significantly higher levels of HSC clonogenic function as measured by day-35 CAFCs compared to CTX alone. Likewise, the levels of HPC clonogenic function measured by CFU-GMs were also significantly higher in NOV-002-treated mice than these in CTX alone treated mice, but to a lesser extent than what were observed with HSCs (Figure 1D).

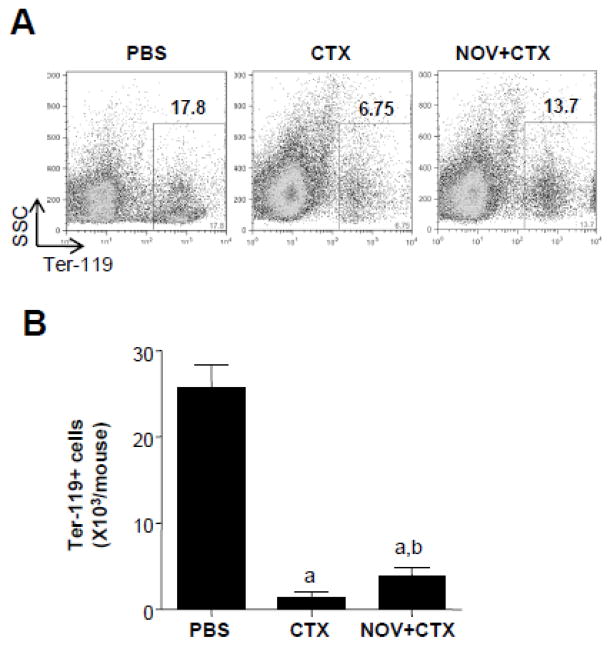

Since some previous clinical studies with NOV-002 in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy have reported a decrease in anemic events [36, 40], we examined whether NOV-002 treatment had an effect on the CTX-induced damage to erythroid precursors. To this end, BM cell suspensions were harvested from mice on day 3 after PBS or CTX injection with or without NOV-002 treatment. The cells were stained with an antibody against the erythroid marker Ter-119. Figure 2A shows a representative dotplot of BM cells from each experimental group. We found significantly higher levels of Ter-119 positive cells in BM cells from NOV-002-treated mice at day 3 post CTX relative to mice that received CTX only (Figure 2B). Greater numbers of megakaryocyte-erythrocyte progenitors (MEPs) which give rise to megakaryocyte-erythrocyte lineages were also observed in BM of mice treated with NOV-002 on day 3 after CTX treatment than these of mice with CTX treatment alone (data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that NOV-002 treatment can ameliorate CTX-induced BM toxicity not only by reducing the decrease of HSCs and HPCs, but also by preserving their hematopoietic function.

Figure 2. NOV-002 protects erythrocyte precursors against CTX-induced toxicity.

Mice were treated with vehicle (PBS), CTX alone (CTX) or CTX plus NOV-002 (NOV+CTX). Three days after the treatment(s), BM cells were harvested for analysis of Ter-119+erythroid cells. A. Representative gating strategies for the analysis ofTer-119+erythroid cells in BM-MNCs by flow cytometry. The numbers presented in the flow charts are the frequencies (%) of Ter-119+erythroid cells in BM-MNCs. B. Average numbers of BM Ter-119+ cells in each mouse. The data are presented as mean ± SDEV of 3 independent experiments. a, p<0.05 vs. PBS; b, p<0.05 vs. CTX.

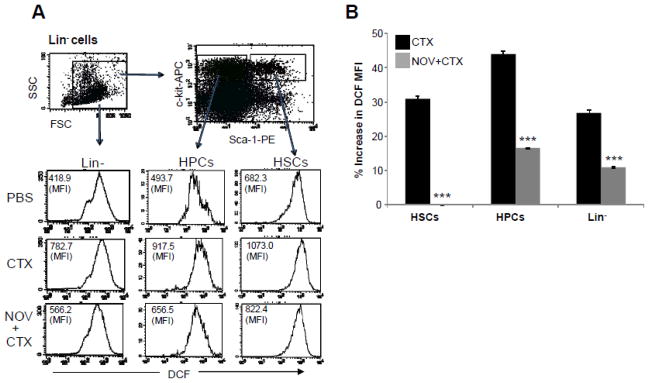

NOV-002 inhibits CTX-induced increase in ROS production in HSPCs

Increases in ROS production in HSPCs can occur under various pathological conditions that lead to inhibition of HSPC function and BM suppression, because ROS can induce HSPC apoptosis and senescence in a dose-dependent manner [13–20]. We examined whether NOV-002 as a redox modulator can reduce CTX-induced BM suppression in part by downregulation of ROS production in HSPCs. As shown in Figure 3, the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of DCF in Lin− BM hematopoietic cells, HPCs, and HSCs from CTX-treated animals was significantly greater than that in the cells from PBS-treated mice. This change is unlikely caused by the differences in the uptake of CM-H2DCFDA and efflux of DCF between the cells from PBS-treated mice and those from CTX-treated animals as they showed a similar DCF MFI after the cells were incubated with irradiated CM-H2DCFDA (data not shown). In addition, Mn (III) meso-tetrakis (N-ethylpyridinium-2-yl) porphyrin, a superoxide dismutase mimetic and a potent antioxidant, could inhibit CTX-induced increases in DCF MFI in HSPCs (data not shown). These results suggest that CTX treatment elevates ROS production in hematopoietic cells. Interestingly, the increases were abrogated in HSCs and attenuated in Lin− cells and HPCs by the treatment with NOV-002. These results demonstrate that indeed NOV-002 has the ability to reduce CTX-induced increase in ROS production in HSPCs, which may confer a significant protection of HSPCs against CTX-induced toxicity.

Figure 3. NOV-002 inhibits CTX-induced ROS production in BM HSPCs.

Mice were treated with vehicle (PBS), CTX alone (CTX) or CTX plus NOV-002 (NOV+CTX). Three days after the treatment(s), BM cells were harvested and analyzed. A. Representative analysis of ROS production in BM lineage negative hematopoietic cells (Lin−), HPCs and HSCs by flow cytometry. The numbers presented in the flow charts are the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of DCF. B. Percent increases in ROS production by Lin− cells, HPCs and HSCs after treatment with CTX or CTX plus NOV-002 compared to PBS-treated cells according to the changes in DCF MFI. The data are presented as mean ± SDEV of 3 independent experiments. ***, p<0.05 vs. CTX.

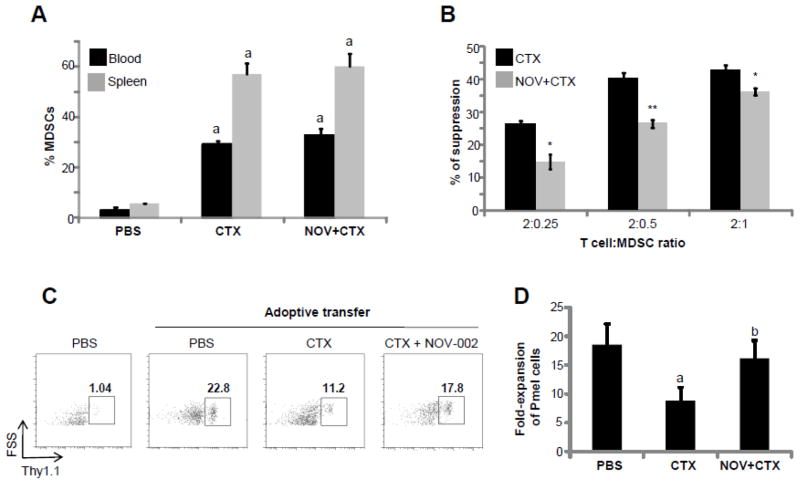

NOV-002 does not reduce the induction of MDSCs by CTX, but decreases their immunosuppressive activity

Our group and others have previously reported that CTX treatment can increase circulating MDSCs (CD11b+Ly6G+ cells) both in mice and humans [22, 41–46]. MDSCs are strong suppressors of T cell-mediated responses [28, 47], and therefore may contribute to CTX-induced immune suppression [46]. We examined if the treatment with NOV-002 can also impact on CTX-induced immune suppression by modulating the induction and activity of MDSCs. As shown in Figure 4A, CTX significantly increased the frequencies of MDSCs in the spleen and peripheral blood. The increases were not affected by NOV-002 treatment. We then determined whether NOV-002 treatment had an effect on the immunosuppressive activity of MDSCs. To this end, T cells were co-cultured with purified MDSCs at different T cell to MDSC ratios, and then activated with beads coated with monoclonal antibodies against CD3 and CD28. The proliferation of T cells was determined by 3H Thymidine incorporation, and the percentage suppression of T cell proliferation was calculated relative to the proliferation observed in the absence of MDSCs. Figure 4B shows a significant decrease in the percentage of suppression of T cell proliferation by MDSCs isolated from mice treated with CTX + NOV-002 when compared with MDSCs isolated from mice treated with CTX only.

Figure 4. NOV-002 does not reduce the induction of MDSCs by CTX but decreases their immunosuppressive activity.

Mice were treated with vehicle (PBS), CTX alone (CTX) or CTX plus NOV-002 (NOV+CTX). Seven days after the treatment(s), peripheral blood cells and splenocytes were harvested for analysis of CD11b+Ly6G+ MDSCs by flow cytometry. A. Percentages of MDSCs in peripheral blood cells and splenocytes. The data are presented as mean ± SDEV of 3 independent experiments. a, p<0.05 vs. PBS. B. Percent suppression of in vitro T cell proliferation by MDSCs isolated from the spleens of mice treated with CTX or NOV-002 + CTX. The data are presented as mean ± SDEV of 3 independent experiments. *, p=0.05 and **, p=0.01 vs. CTX. C. Gating strategy to determine the expansion of donor-derived Pmel T cells (Thy1.1+) after adoptive transfer and vaccination. The numbers presented in the flow charts are the frequencies (%) of donor-derived Pmel T cells in the spleen Thy1.1 positive T cells. D. Fold-increase in the expansion of donor –derived Pmel T cells after vaccination compared to mice without adoptive transfer. The data are presented as mean ± SDEV of 5 independent experiments. a, p<0.02 vs. PBS; b, p<0.01 vs. CTX.

Next, we examined the effect of NOV-002 treatment on the in vivo immunosuppressive activity of CTX-induced MDSCs. In this study, C57BL/6 (Ly5.2) mice were injected with PBS, CTX, or CTX+ NOV-002 as described before. After 7 days of treatment, mice were adoptively transferred with 1×107 splenocytes from Pmel mice (Ly5.1+). One day after transfer, recipient mice received 100 μg of cognate gp100 peptide, and three days later the frequency of Pmel cells in the peripheral blood was determined by flow cytometry according to Ly5.1 staining among host lymphocytes as shown in Figure 4C. Figure 4D shows a robust expansion of Pmel lymphocytes in response to activation with cognate peptide in mice that did not receive CTX. However, this expansion was significantly reduced after CTX treatment presumably due to the suppressive effect of CTX-derived MDSC [23, 28, 29]. By contrast, daily NOV-002 injections after CTX treatment, were able to attenuate the reduction in Pmel cell expansion. These results suggest that NOV-002, while unable to alter the overall expansion of CTX-induced MDSCs as shown in Figure 4C, is able to reduce their ability to suppress T cell responses.

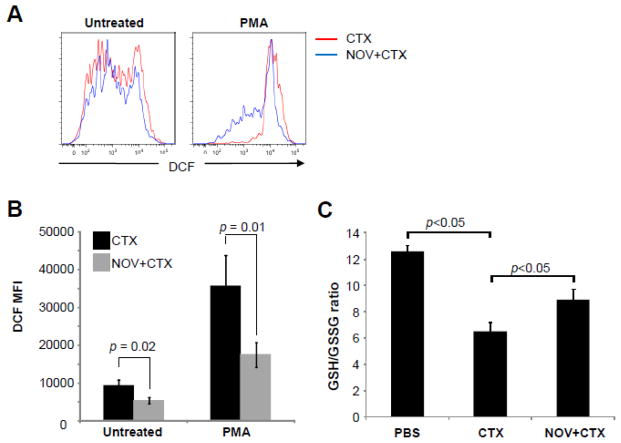

NOV-002 treatment inhibits ROS production by CTX-induced MDSCs and increases the ratio of GSH/GSSG in MDSCs from CTX-treated mice

To further elucidate the mechanism associated with the reduction of the immunosuppressive activity of CTX-induced MDSCs after NOV-002 treatment, we measured the levels of ROS in MDSCs from mice treated with CTX or CTX + NOV-002, because it has been suggested that increased production of ROS can increase the immunosuppressive activity of MDSCs [23, 28–30]. ROS production by MDSCs from mice receiving CTX and/or NOV-002 treatment were determined by flow cytometry with or without PMA stimulation as shown in Figure 5A. Treatment of mice with NOV-002 significantly reduced ROS production in unstimulated MDSCs from CTX-treated mice by approximately 44%. As expected, stimulation of MDSCs from day 7 CTX-treated mice with PMA (30 ng/ml) led to further increase in ROS production. However, the increase again was significantly reduced by NOV-002 treatment (Figure 5B). In addition, we analyzed the overall levels of GSH and GSSG in spleen and calculated their ratio and found that CTX treatment significantly reduced the GSH/GSSG, while NOV-002 treatment attenuated the reduction (Figure 5C). These results suggest that treatment with NOV-002 decreases the production of ROS by CTX-induced MDSCs, which may contribute to the reversal of MDSC-mediated immune suppression of T cell function.

Figure 5. NOV-002 treatment inhibits ROS production by CTX-induced MDSCs and associates with an increase in the GSH/GSSG ration in splenocytes from CTX-treated mice.

Mice were treated with CTX alone (CTX) or CTX plus NOV-002 (NOV+CTX). Seven days after the treatment(s), ROS production in BM CD11b+Ly6G+ MDSCs with or without PMA stimulation was determined by flow cytometry and the levels of GSH/GSSG in splenocytes without PMA stimulation were quantified for calculation of the GSH/GSSG ratio. A. Representative analyses of ROS production in BM CD11b+Ly6G+ MDSCs by flow cytometry. B. Average ± SDEV (n=5) of DCF MFI from untreated or PMA-activated MDSCs isolated from BM. C. Average ± SDEV (n=5) of the GSH/GSSG ratio in splenocytes from mice treated with PBS, CTX alone, or CTX plus NOV-002.

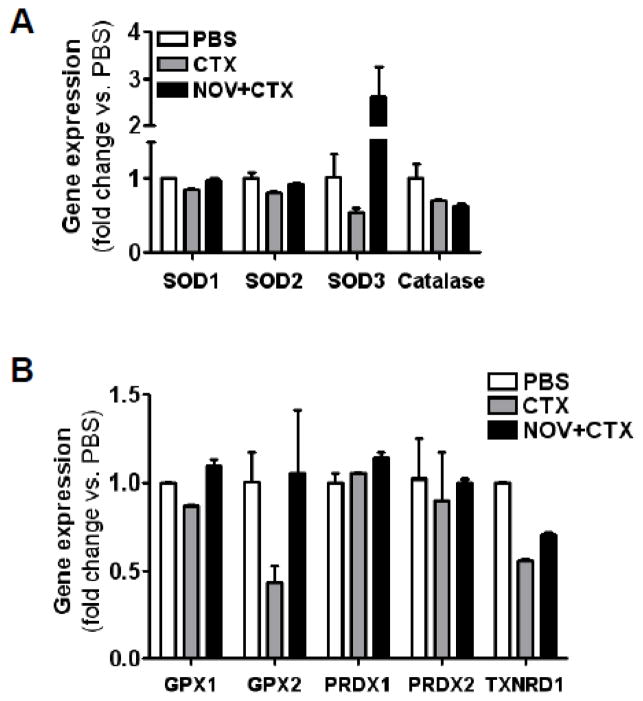

NOV-002 treatment increases SOD3 and GPX2 expression in HSPCs

In order to gain more insights into the mechanisms by which NOV-002 regulates ROS production in HSPCs after CTX treatment, we analyzed the expression of mRNA of several important antioxidant enzymes by real-time RT-PCR. As shown in Figure 6, the expression of SOD3 and GPX2 mRNA in HSPCs was downregulated more than 50% by the treatment with CTX, while the expression of all other antioxidant enzymes examined was not significantly changed by CTX injection. The downregulation of the expression of SOD3 and GPX2 mRNA in HSPCs was completely inhibited by NOV-002 treatment. More interestingly, the expression of SOD3 mRNA was actually increased about 2.5 fold in the cells from NOV-002-treated mice than that in the cells from PBS-treated mice. These findings suggest that NOV-002 can inhibit CTX-induced oxidative stress in HSPCs at least in part by upregulating the expression of SOD3 and GPX2.

Figure 6. Effects of NOV-002 treatment on the expression of selective antioxidant enzyme mRNA in HSPCs.

Mice were treated with vehicle (PBS), CTX alone (CTX) or CTX plus NOV-002 (NOV+CTX). Three days after the treatment(s), HSPCs were purified by cell sorting and their expression of selective antioxidant enzyme mRNA was quantified by real-time RT-PCR. The data are presented as mean ± SDEV of fold changes vs. PBS-treated cells (n=3).

DISCUSSION

Hematologic toxicity and immune suppression are common complications of chemotherapy in cancer patients [6, 48]. The mechanisms by which chemotherapeutic agents cause these complications are not yet completely understood, but may be attributed in part to the induction of increased production of ROS in HSPCs [49–54] and MDSCs [23, 29].

It has been well established that increased production of ROS contributes to the BM suppression induced by total body irradiation [9]. However, the role of ROS in mediating BM suppression induced by chemotherapeutic agents such as CTX was not well understood. Our present studies suggest that ROS may also play an important role in CTX-induced myelosuppression. First, we have found that increased production of ROS is associated with CTX-induced hematopoietic toxicity. Furthermore, our study shows that the addition of the glutathione disulfide mimetic NOV-002 to CTX, a widely used chemotherapeutic agent, results in protection of BM HSPCs against the cytotoxic effects of CTX, including the preservation of the number of BM HSPCs and their clonogenic activities. The protective effects of NOV-002 against CTX may be attributable to its ability to modulate cellular redox. This suggestion is supported by the finding that NOV-002 treatment upregulated the expression of SOD3 and GPX2 in HSPCs; inhibited CTX-induced increases in ROS production in HSPCs and MDSCs; and attenuated CTX-induced reduction of the ratio of GSH/GSSG in MDSCs. However, the mechanisms by which ROS mediates CTX-induced HSPC injury have yet to be elucidated. However, it has been shown that ROS can impair HSPC function by induction of HSPC apoptosis and senescence. The induction of HSPC apoptosis is primarily attributed to ROS-produced oxidative damage. In contrast, the induction of HSPC senescence may result from ROS-mediated stimulation of constant HSPC cycling and activation of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38)-p16Ink4a pathway. It has yet to be determined whether CTX causes BM suppression by induction of HSPC apoptosis and/or senescence through ROS. In addition, it appears that the protective effect of NOV-002 on HSCs was greater than that on HPCs as shown in Figure 1C and D. This may be attributable to the higher sensitivity of HSCs to oxidative damage than HPCs as shown in previous studies [9, 15–17]. Although NOV-002 can effectively protect HSPCs by inhibiting CTX-induced ROS production, it is unlikely that NOV-002 will increase the risk of cancer patients to secondary malignancies. This is because it has been well established that increase in ROS production is the underlying mechanism whereby chemotherapy and radiation cause genetic instability that can lead to the induction of leukemia and cancer.

MDSCs are a heterogenous population of immature myeloid cells whose numbers can increase rather dramatically in a variety diseases, including cancer, autoimmune disease, trauma, burns and sepsis as well as in response to certain immunosuppressive chemotherapeutic drugs, such as CTX [21–23, 28, 29]. Initial studies on MDSCs have occurred mostly in the setting of cancer, focusing on the ability of MDSCs to suppress T-cell activation through several mechanisms, including generation of ROS, depletion of GSH, nitrosylation of T cell receptor, depletion of extracellular arginine (essential micronutrient for T-cells), and secretion of immune inhibitory cytokines and molecules (such as IL-10 and prostaglandins) [21–30]. Our group and others have previously shown an association between CTX-containing chemotherapy and increased levels of circulating MDCSs, which can suppress T-cell activation in various preclinical and clinical settings [22, 42–45]. Our results presented here showed NOV-002 had no impact on overall the levels of CTX-induced MDSCs. However, MDCSs from mice treated with NOV-002 showed decreased immunosuppressive capabilities. Since one of the immunosuppressive mechanisms of MDSCs is through the generation of ROS, we examined whether NOV-002 affected the ability of MDSCs to generate ROS. Our findings suggest that daily treatment with NOV-002 was able to reverse T-cell suppression by CTX-derived MDSCs in vivo, through downregulation of ROS production as seen in HSCs/HPCs.

These findings suggest that pharmacological modulators of the redox pathway, such as NOV-002, maybe an alternative to growth factors for ameliorating chemotherapy-induced hematologic toxicities and immune suppression. This is particularly important when concerns about widespread use of erythopoiesis-stimulating agents decreasing survival and/or leading to poorer cancer related outcomes in cancer patients have restricted their use, and no other alternatives currently exist other than blood transfusions. Moreover, our results also demonstrate that NOV-002 was able to modulate the suppressive effects of CTX-derived MDSCs. These studies further our understanding of the hematologic effects of NOV-002. One previous randomized phase 2 trial in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) receiving platinum based chemotherapy +/− daily NOV-002 injections reported that patients receiving NOV-002 in combination with chemotherapy had reduced hematologic toxicities from the chemotherapy as evidenced by significantly higher peripheral leukocyte counts, hemoglobin, as well as higher lymphocyte counts [36]. However, these findings were not observed in a subsequent larger randomized phase 3 trial. Our results here suggest that this improvement in hematologic indices by the addition of daily NOV-002 observed in some clinical trials may be attributable in part to the ability of this compound to inhibit ROS production in HSPCs in response to chemotherapy. However, unlike other redox modulating agents, particularly various antioxidants, NOV-002 does not protect tumor cells against chemotherapy. Therefore, NOV-002 may be of particular beneficial in amelioration of chemotherapy-induced hematologic toxicities and immune suppression in cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mrs. Aimin Yang for her excellent technical assistance and Mr. Richard Peppler and Dr. Haiqun Zeng at the Hollings Cancer Center Flow Cytometry & Cell Sorting Shared Resource for the flow cytometric analysis and cell sorting. This study was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Herbst C, Naumann F, Kruse EB, Monsef I, Bohlius J, Schulz H, Engert A. Prophylactic antibiotics or G-CSF for the prevention of infections and improvement of survival in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD007107. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007107.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daniel D, Crawford J. Myelotoxicity from chemotherapy. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:74–85. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weycker D, Malin J, Edelsberg J, Glass A, Gokhale M, Oster G. Cost of neutropenic complications of chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:454–460. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lyman GH, Michels SL, Reynolds MW, Barron R, Tomic KS, Yu J. Risk of mortality in patients with cancer who experience febrile neutropenia. Cancer. 116:5555–5563. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hershman DL, Wang X, McBride R, Jacobson JS, Grann VR, Neugut AI. Delay of adjuvant chemotherapy initiation following breast cancer surgery among elderly women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;99:313–321. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9206-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohlius J, Herbst C, Reiser M, Schwarzer G, Engert A. Granulopoiesis-stimulating factors to prevent adverse effects in the treatment of malignant lymphoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD003189. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003189.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bohlius J, Tonia T, Schwarzer G. Twist and shout: one decade of meta-analyses of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in cancer patients. Acta Haematol. 125:55–67. doi: 10.1159/000318897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naka K, Hirao A. Maintenance of genomic integrity in hematopoietic stem cells. Int J Hematol. doi: 10.1007/s12185-011-0793-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Liu L, Pazhanisamy SK, Li H, Meng A, Zhou D. Total body irradiation causes residual bone marrow injury by induction of persistent oxidative stress in murine hematopoietic stem cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 48:348–356. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prus E, Fibach E. Effect of iron chelators on labile iron and oxidative status of thalassaemic erythroid cells. Acta Haematol. 123:14–20. doi: 10.1159/000258958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghaffari S. Oxidative stress in the regulation of normal and neoplastic hematopoiesis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1923–1940. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Naka K, Muraguchi T, Hoshii T, Hirao A. Regulation of reactive oxygen species and genomic stability in hematopoietic stem cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1883–1894. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hole PS, Pearn L, Tonks AJ, James PE, Burnett AK, Darley RL, Tonks A. Ras-induced reactive oxygen species promote growth factor-independent proliferation in human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 115:1238–1246. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-222869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hosokawa K, Arai F, Yoshihara H, Nakamura Y, Gomei Y, Iwasaki H, Miyamoto K, Shima H, Ito K, Suda T. Function of oxidative stress in the regulation of hematopoietic stem cell-niche interaction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;363:578–583. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ito K, Hirao A, Arai F, Takubo K, Matsuoka S, Miyamoto K, Ohmura M, Naka K, Hosokawa K, Ikeda Y, Suda T. Reactive oxygen species act through p38 MAPK to limit the lifespan of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:446–451. doi: 10.1038/nm1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jang YY, Sharkis SJ. A low level of reactive oxygen species selects for primitive hematopoietic stem cells that may reside in the low-oxygenic niche. Blood. 2007;110:3056–3063. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-087759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyamoto K, Araki KY, Naka K, Arai F, Takubo K, Yamazaki S, Matsuoka S, Miyamoto T, Ito K, Ohmura M, Chen C, Hosokawa K, Nakauchi H, Nakayama K, Nakayama KI, Harada M, Motoyama N, Suda T, Hirao A. Foxo3a is essential for maintenance of the hematopoietic stem cell pool. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schraml E, Fuchs R, Kotzbeck P, Grillari J, Schauenstein K. Acute adrenergic stress inhibits proliferation of murine hematopoietic progenitor cells via p38/MAPK signaling. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:215–227. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheng KC, Pietersz GA, Tang CK, Ramsland PA, Apostolopoulos V. Reactive oxygen species level defines two functionally distinctive stages of inflammatory dendritic cell development from mouse bone marrow. J Immunol. 184:2863–2872. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Kellner J, Liu L, Zhou D. Inhibition of p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Promotes Ex Vivo Hematopoietic Stem Cell Expansion. Stem Cells Dev. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuenca AG, Delano MJ, Kelly-Scumpia KM, Moreno C, Scumpia PO, Laface DM, Heyworth PG, Efron PA, Moldawer LL. A Paradoxical Role for Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells in Sepsis and Trauma. Mol Med. 17:281–292. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diaz-Montero CM, Salem ML, Nishimura MI, Garrett-Mayer E, Cole DJ, Montero AJ. Increased circulating myeloid-derived suppressor cells correlate with clinical cancer stage, metastatic tumor burden, and doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:49–59. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0523-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greten TF, Manns MP, Korangy F. Myeloid derived suppressor cells in human diseases. Int Immunopharmacol. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haile LA, von Wasielewski R, Gamrekelashvili J, Kruger C, Bachmann O, Westendorf AM, Buer J, Liblau R, Manns MP, Korangy F, Greten TF. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in inflammatory bowel disease: a new immunoregulatory pathway. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:871–881. 881 e871–875. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoechst B, Ormandy LA, Ballmaier M, Lehner F, Kruger C, Manns MP, Greten TF, Korangy F. A new population of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma patients induces CD4(+)CD25(+)Foxp3(+) T cells. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:234–243. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoechst B, Voigtlaender T, Ormandy L, Gamrekelashvili J, Zhao F, Wedemeyer H, Lehner F, Manns MP, Greten TF, Korangy F. Myeloid derived suppressor cells inhibit natural killer cells in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma via the NKp30 receptor. Hepatology. 2009;50:799–807. doi: 10.1002/hep.23054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marigo I, Dolcetti L, Serafini P, Zanovello P, Bronte V. Tumor-induced tolerance and immune suppression by myeloid derived suppressor cells. Immunol Rev. 2008;222:162–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: linking inflammation and cancer. J Immunol. 2009;182:4499–4506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao F, Obermann S, von Wasielewski R, Haile L, Manns MP, Korangy F, Greten TF. Increase in frequency of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in mice with spontaneous pancreatic carcinoma. Immunology. 2009;128:141–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03105.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenderny S, Lin H, Garrett T, Tew KD, Townsend DM. Protective effects of a glutathione disulfide mimetic (NOV-002) against cisplatin induced kidney toxicity. Biomed Pharmacother. 64:73–76. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Townsend DM, Findlay VL, Tew KD. Glutathione S-transferases as regulators of kinase pathways and anticancer drug targets. Methods Enzymol. 2005;401:287–307. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)01019-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Townsend DM, He L, Hutchens S, Garrett TE, Pazoles CJ, Tew KD. NOV-002, a glutathione disulfide mimetic, as a modulator of cellular redox balance. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2870–2877. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Townsend DM, Tew KD. Pharmacology of a mimetic of glutathione disulfide, NOV-002. Biomed Pharmacother. 2009;63:75–78. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uys JD, Manevich Y, Devane LC, He L, Garret TE, Pazoles CJ, Tew KD, Townsend DM. Preclinical pharmacokinetic analysis of NOV-002, a glutathione disulfide mimetic. Biomed Pharmacother. 64:493–498. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Townsend DM, Pazoles CJ, Tew KD. NOV-002, a mimetic of glutathione disulfide. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17:1075–1083. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.7.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meng A, Wang Y, Brown SA, Van Zant G, Zhou D. Ionizing radiation and busulfan inhibit murine bone marrow cell hematopoietic function via apoptosis-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:1348–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ploemacher RE, van der Sluijs JP, Voerman JS, Brons NH. An in vitro limiting-dilution assay of long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells in the mouse. Blood. 1989;74:2755–2763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ploemacher RE, van Os R, van Beurden CA, Down JD. Murine haemopoietic stem cells with long-term engraftment and marrow repopulating ability are more resistant to gamma-radiation than are spleen colony forming cells. Int J Radiat Biol. 1992;61:489–499. doi: 10.1080/09553009214551251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diaz-Montero CMPN, Onicescu G, Zhu Y, Verma N, Garrett-Mayer E, Schuhwerk KC, Pazoles CJ, Glück S, Montero AJ. Daily injections of the glutathione disulfide mimetic NOV-002 ameliorates hematologic toxicities from neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients enrolled in the NEO-NOVO trial, and significantly increases circulating dendritic cells [abstract]. CTRC-AACR San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, Edition; San Antonio. 2008. p. Abstr 2141. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Honeychurch J, Glennie MJ, Illidge TM. Cyclophosphamide inhibition of anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody-based therapy of B cell lymphoma is dependent on CD11b+ cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7493–7501. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salem ML, Al-Khami AA, El-Naggar SA, Diaz-Montero CM, Chen Y, Cole DJ. Cyclophosphamide induces dynamic alterations in the host microenvironments resulting in a Flt3 ligand-dependent expansion of dendritic cells. J Immunol. 184:1737–1747. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salem ML, Diaz-Montero CM, Al-Khami AA, El-Naggar SA, Naga O, Montero AJ, Khafagy A, Cole DJ. Recovery from cyclophosphamide-induced lymphopenia results in expansion of immature dendritic cells which can mediate enhanced prime-boost vaccination antitumor responses in vivo when stimulated with the TLR3 agonist poly(I:C) J Immunol. 2009;182:2030–2040. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Salem ML, El-Naggar SA, Cole DJ. Cyclophosphamide induces bone marrow to yield higher numbers of precursor dendritic cells in vitro capable of functional antigen presentation to T cells in vivo. Cell Immunol. 261:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salem ML, Kadima AN, El-Naggar SA, Rubinstein MP, Chen Y, Gillanders WE, Cole DJ. Defining the ability of cyclophosphamide preconditioning to enhance the antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell response to peptide vaccination: creation of a beneficial host microenvironment involving type I IFNs and myeloid cells. J Immunother. 2007;30:40–53. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000211311.28739.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pelaez B, Campillo JA, Lopez-Asenjo JA, Subiza JL. Cyclophosphamide induces the development of early myeloid cells suppressing tumor cell growth by a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2001;166:6608–6615. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Serafini P, Borrello I, Bronte V. Myeloid suppressor cells in cancer: recruitment, phenotype, properties, and mechanisms of immune suppression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2006;16:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crawford J, Dale DC, Lyman GH. Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia: risks, consequences, and new directions for its management. Cancer. 2004;100:228–237. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu Y, Cederbaum A. The mode of cisplatin-induced cell death in CYP2E1-overexpressing HepG2 cells: modulation by ERK, ROS, glutathione, and thioredoxin. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:1061–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martins NM, Santos NA, Curti C, Bianchi ML, Santos AC. Cisplatin induces mitochondrial oxidative stress with resultant energetic metabolism impairment, membrane rigidification and apoptosis in rat liver. J Appl Toxicol. 2008;28:337–344. doi: 10.1002/jat.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pratheeshkumar P, Kuttan G. Ameliorative action of Vernonia cinerea L. on cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppression and oxidative stress in mice. Inflammopharmacology. 18:197–207. doi: 10.1007/s10787-010-0042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Asmis R, Wang Y, Xu L, Kisgati M, Begley JG, Mieyal JJ. A novel thiol oxidation-based mechanism for adriamycin-induced cell injury in human macrophages. FASEB J. 2005;19:1866–1868. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2991fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pratheeshkumar P, Kuttan G. Cardiospermum halicacabum inhibits Cyclophosphamide Induced Immunosupression and Oxidative Stress in Mice and also Regulates iNOS and COX-2 Gene Expression in LPS Stimulated Macrophages. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 11:1245–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Durken M, Agbenu J, Finckh B, Hubner C, Pichlmeier U, Zeller W, Winkler K, Zander A, Kohlschutter A. Deteriorating free radical-trapping capacity and antioxidant status in plasma during bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:757–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]