Abstract

The Tristetraprolin (TTP) protein family includes four mammalian members (TTP, TIS11b, TIS11d, and ZFP36L3), but only one in Drosophila melanogaster (DTIS11). These proteins bind target mRNAs with AU-rich elements (AREs) via two C3H zinc finger domains and destabilize the mRNAs. We found that overexpression of mouse TIS11b or DTIS11 in the Drosophila retina dramatically reduced eye size, similar to the phenotype of eyes absent (eya) mutants. The eya transcript is one of many ARE-containing mRNAs in Drosophila. We showed that TIS11b reduced levels of eya mRNA in vivo. In addition, overexpression of Eya rescued the TIS11b overexpression phenotype. RNA pull-down and luciferase reporter analyses demonstrated that the DTIS11 RNA-binding domain is required for DTIS11 to bind the eya 3′ UTR and reduce levels of eya mRNA. Moreover, ectopic expression of DTIS11 in Drosophila S2 cells decreased levels of eya mRNA and reduced cell viability. Consistent with these results, TTP proteins overexpressed in MCF7 human breast cancer cells were associated with eya homologue 2 (EYA2) mRNA, and caused a decrease in EYA2 mRNA stability and cell viability. Our results suggest that eya mRNA is a target of TTP proteins, and that downregulation of EYA by TTP may lead to reduced cell viability in Drosophila and human cells.

Keywords: eyes absent, tristetraprolin, Drosophila, AU-rich element, RNA stability.

Introduction

Gene expression in eukaryotic cells is a highly dynamic process, involving transcription, splicing, mRNA export, mRNA localization, mRNA stabilization, and translation. In mammals, a genome-wide study estimated that 40-50% of changes in gene expression in response to cellular signals occur at the level of mRNA stability 1. The AU-rich elements (AREs) in mRNA 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) are recognized by a subset of RNA-binding proteins that modulate RNA stability 2. Tristetraprolin (TTP) proteins bind AREs and destabilize mRNA 3. This family is comprised of three proteins in man and four in rodents 4, including TTP (also called TIS11, ZFP36, NUP475, or G0S24), TIS11b (ZFP36L1, ERF1, BRF1, or CMG1), TIS11d (ZFP36L2, ERF2, or BRF2), and the rodent-specific ZFP36L3 5. All TTP proteins have a highly conserved C3H tandem zinc finger (TZF) domain, which binds to AREs and promotes the deadenylation and destruction of ARE-containing target sequences 6,7.

In macrophages, TTP affects inflammation by negatively regulating the expression of pro-inflammatory factors such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor 8,9. In Drosophila melanogaster, there is only one protein in the TTP family, DTIS11. Expression levels of antimicrobial peptides are regulated by the effects of DTIS11 on mRNA stability 10,11. Biological function analyses have shown that overexpression of TTP family members induces apoptosis in a variety of cell lines, including HeLa, U20S, SAOS1, 3T3, and B cell lymphoma cells 12-14. Both TTP and TIS11b target cIAP2 mRNA to regulate apoptosis 15,16.

Using systematic genomic approaches, several mRNA targets of TTP proteins have been identified 17-19. The Drosophila ARE database (D-ARED) indicates that ~16% of Drosophila genes contain the mammalian ARE signature, an AUUUA pentamer within an AU-rich context 20. In Drosophila, DTIS11 temporally regulates gene expression through ARE-mediated mRNA decay 20. To better understand TTP function in vivo, we overexpressed TTP proteins in the fly retina. Strikingly, this resulted in a phenotype that was similar to eyes absent (eya) loss of function. We further demonstrated that eya mRNA is a TTP binding target, and that eya mRNA is downregulated in response to TTP in vivo. We performed similar analyses in MCF7 cells, a human breast cancer cell line, and found that TTP overexpression destabilized EYA2 mRNA. These results suggest that the interaction between TTP proteins and eya mRNA is a conserved regulatory mechanism that functions in a number of species and cell types.

Materials and methods

Plasmid constructs

Drosophila Gateway technology was used to generate plasmids for expressing tagged proteins. Mouse TIS11b was PCR amplified from cDNA derived from mouse RAW264.7 cells (forward primer 5′-CACCATGACCACCACCCTCGTGTC-3′, reverse primer 5′-TTAGTCATCTGAGATGGAGAG-3′). DTIS11 was PCR amplified from Drosophila EST clone LD36337 (NHRI, Taiwan) (forward primer 5′-CACCATGTCTGCTGATATTCTGCAG-3′, reverse primer 5′-TTAGAGTCCCAAATTGGACTG-3′). PCR fragments were cloned into pENTR/D-TOPO vector (Invitrogen), confirmed by sequencing, and then transferred into Drosophila Gateway vectors pTFW and pTGW (gifts from Dr. M.-T. Su) via the Clonase II reaction (Invitrogen) to generate FLAG-tagged and GFP-tagged protein expression plasmids, respectively. The 3′ UTR of eya was PCR amplified from cDNA derived from fly heads (forward primer 5′-GAAAGGCCAAACTGTAAGGG-3′ [hereafter, F primer], reverse primer 5′-ATAGAGTGCGTTGCTGTTGG-3′ [R primer]). The resulting PCR fragment was ligated into pCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen), sequenced, and transferred into the 3′ end of pCMV-FLAG-Luciferase (Stratagene) for use in reporter assays. The 3′ UTR was separated into three fragments via PCR using the following primers: fragment 1, F primer and 5′-CGGGTACCGATCGTTGATTAGGTGTTTA-3′; fragment 2, 5′-GTAACAATTCTCGCACGAAG-3′ and 5′-CAGCCAGGATGCGTATC-3′; fragment 3, 5′-GAGAAGCGGAGCAAACAC-3′ and R primer. These fragments were ligated into the 3′ end of pCMV-FLAG-Luciferase. Coding sequences for mouse TIS11b and TIS11d were PCR amplified from cDNA derived from RAW264.7 cells that had been treated for 2 h with lipopolysaccharide. For TIS11b, forward and reverse primers were 5′- ATGACCACCACCCTCGTGTC-3′ and 5′-TTAGTCATCTGAGATGGAGAG-3′, respectively. For TIS11d, forward and reverse primers were 5′-ATGTCGACCACACTTCTGTCAC-3′ and 5′-TCAGTCGTCGGAGATGGAGAGGCG-3′, respectively. After sequencing, PCR fragments were subcloned into pCMV-Tag2B (Stratagene) and pEGFP-C2 (Clontech) for expression in mammalian cells. The cloning of mouse TTP has been described 21.

Site-directed mutagenesis

DTIS11F158N and mTTPF118N mutants were generated using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). For these reactions, pTGW-DTIS11, pCMV-FLAG-DTIS11, and pCMV-FLAG-TTP were used as templates. Primers containing the desired mutation (underlined) were designed as follows: DTIS11, forward 5′-GAAGTGCCAGAACGCCCATGGA-3′ and reverse 5′-TCCATGGGCGTTCTGGCACTTC-3′; TTP, forward 5′-CAAGTGCCAGAATGCTCACGGC-3′ and reverse 5′-GCCGTGAGCATTCTGGCACTTG-3′. All mutations were verified by sequencing.

Fly stocks

eya2, UAS-eya, UAS-GFP, tub-Gal80ts, and eq-Gal4 flies were from Y. Henry Sun (Institution of Molecular Biology [IMB], Academia Sinica, Taiwan); UAS-Bcl, UAS-p53DN, UAS-p35, UAS-DIAP, UAS-mCD8GFP, Lz-Gal4, and GMR-Gal4 flies were from the Bloomington Stock Center; and UAS-dTIS11RNAi flies were obtained from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center. All fly stocks were maintained in 23º or 26ºC environmental insect culture chambers. The pUAS-FLAG-DTIS11, pUAS-FLAG-mTIS11b, pUAS-GFP-mTIS11b, pUAS-GFP-DTIS11, and pUAS-FLAG-DTIS11F158N expression vectors were introduced into flies by traditional germ-line transformation at the IMB.

Cell culture

Drosophila Schneider (S2) cells were grown at 25ºC in Schneider's Drosophila medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco-BRL). Human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells were grown at 37ºC and 5% CO2 in DMEM supplemented with 3.7 g/L sodium bicarbonate and 10% FBS. Human breast cancer cells (MCF7) were cultured in MEM supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 0.1 mM non-essential amino acids, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.01 mg/mL bovine insulin, and 10% FBS. All three cell lines were purchased from Bioresource Collection and Research Center (BCRC, Taiwan)

Immunoblotting analysis

Fly heads or cultured cells were harvested and extracted in whole-cell extract buffer (25 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 0.5 mM DTT). Whole-cell extracts (20 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and detected using anti-FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich), anti-GFP (GeneTex), anti-Eya (Drosophila Hybridoma Bank), or anti-γ-H2AX (Cell Signaling). The peroxidase labeled goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (KPL) in combination with Western Lightning- enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (PerkinElmer) were used for detection on X-ray film from FUJIFILM Corporation.

RNA immunoprecipitation (RNA-IP)

Whole-cell extracts (300 μg) from control fly heads or fly heads expressing FLAG-mTIS11b were adjusted to 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.1% (v/v) Triton X-100, 0.5 mM DTT, and 1 U/μL RNasin. Samples were pre-cleaned with protein A-Sepharose (Amersham Pharmacia) for 1 h. After centrifugation, anti-FLAG-Sepharose (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the supernatants and rotated at 4ºC for 2 h. Beads were washed three times using NT2 buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.05% NP-40) and then incubated with 100 μL NT2 buffer containing 5 U RNase-free DNase I (Ambion) for 15 min at 30ºC. Beads were washed once with NT2 buffer and then incubated in 100 μL NT2 buffer containing 0.1% SDS and 0.5 mg/mL proteinase K at 55ºC for 15 min. For RT-PCR, RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen). cDNAs of interest were amplified using 4% of the RT reaction in a 20-µL PCR reaction containing 10 pmol forward and reverse primers, respectively: eya, 5′-CCTGGCTACAGATACGCTCG-3′ and 5′-TGGAGGTTACCAGCACGTTG-3′; rp49, 5′-GCGCACCAAGCACTTCATC-3′ and 5′-GTAAACGCGGTTCTGCATGAG-3′. PCR products were separated using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. FLAG-tagged TTP and TTPF118N were expressed in MCF7 cells, and whole-cell extracts were isolated to perform RNA-IP. After RNA isolation and reverse transcription, human EYA2 and β-actin mRNA were detected by PCR using the following primers: EYA2, 5′-GGACAATGAGATTGAGCGTGT-3′ and 5′-ATGTGGGGTTGAGTAAGGAGT-3′; β-actin, 5′-GCACCAGGGCGTGATGG-3′ and 5′-GCCTCGGTCAGCAGCA-3′.

RNA pull-down analysis

To overexpress mouse TTP family proteins and DTIS11, 1 × 107 HEK293T cells were transfected with GFP-TTP, GFP-TIS11b, GFP-TIS11d, GFP-DTIS11, FLAG-DTIS11, or FLAG-DTIS11F158N expression plasmid (10 μg) using calcium phosphate precipitation. Cytoplasmic extracts were prepared using hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10 mM potassium acetate, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.05% NP-40, protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich), and phosphatase inhibitors containing 0.01 M β-glycerol phosphate, 0.1 mM Na2MoO4, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, pH 10.0, and 0.01 M NaF). The potassium acetate concentration of the extracts was adjusted to 90 mM, and then 0.2 U/µL RNase inhibitor (Promega) and 0.1 µg/µL yeast tRNA (Ambion) were added. Extracts were incubated with 15 μL heparin-agarose (Sigma-Aldrich) at 4ºC for 15 min, and subsequently cleaned with 10 μL streptavidin-Sepharose (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 4ºC with rotation. In vitro-transcribed biotinylated ARE (4 µg) from the 3′ UTR of eya, TTP, TNF, or control 18S rRNA (T7-MEGAshortscript, Ambion) was added to the supernatant, and the mixture was incubated for 1 h at 4ºC. The protein and biotinylated RNA complexes were recovered by addition of 10 μL streptavidin-Sepharose at 4ºC for 2 h with rotation. After washing four times with binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 90 mM potassium acetate, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.05% NP-40, and protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails), pulled-down complexes were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-FLAG.

Transfection and luciferase reporter analysis

HEK293T cells were seeded into six-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well. The next day, cells were transfected using calcium phosphate precipitation (0.5 µg pCMV-FLAG-luciferase or pCMV-FLAG-luciferase-eya 3′ UTR constructs, 0.01 µg pCMV-β-galactosidase, and indicated dosages of DTIS11 and DTIS11F158N expression vectors). After 36 h, RNA was isolated for quantitative PCR analysis (described in next section), and cell lysates were collected for luciferase and β-galactosidase activity assays 22 and immunoblotting. To correct for variations in the transfection efficiency and expression level of each construct, luciferase assay values were divided by the β-galactosidase value and then normalized to the control group. Each treatment condition was performed in duplicate, and each experiment was repeated three times independently.

RNA isolation and quantitative PCR

To examine endogenous eya mRNA expression, S2 cells were seeded into six-well plates at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well and transfected with 3 μg of pAC5.1-GFP, pAC5.1-GFP-DTIS11, or pAC5.1-GFP-DTIS11F158N using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After 24 h, total RNA was collected using TRIzol. Total RNA (20 µg) was subsequently treated with TURBO DNase (Ambion) at 37ºC for 1 h, and then extracted using TRIzol. Total RNA (5 µg) was reverse-transcribed to cDNA in the presence of 0.5 μg oligo-dT primer using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed in a total volume of 20 µL with FastStart Universal PCR Master Mix (Roche) on an Applied Biosystems 7300 Real-Time PCR System. Reactions contained cDNA template plus forward and reverse primers for eya and rp49 (0.4 µM each). Similar experiments were performed in MCF7 cells overexpressing TTP family proteins. In these experiments, PCR was carried out using human EYA2 and β-actin primers. RNA from HEK293T cells (described above) was analyzed by PCR using luciferase primers (5′-ACAACACCCCAACATCTTCGA-3′ and 5′-CGTCTTTCCGTGCTCCAAAA-3′) and β-galactosidase primers (5′-GGATGTCGCTCCACAAGGTAA-3′ and 5′-CGGTTGCACTACGCGTACTGT-3′). Amplification conditions were 40 cycles of 95ºC for 15 s and 60ºC for 1 min. Results were analyzed using a mathematical ΔΔCt method.

MTS cell viability assay

S2 cells or MCF7 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well with 100 μL culture medium. They were transfected with 0.2 μg DNA using Lipofectamine 2000. After 2 days, 20 μL CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution (Promega) was added to each well, and cells were incubated at 25º (S2 cells) or 37 ºC (MCF7 cells) for 2 h. Absorbance at 490 nm was recorded using a SpectraMax M2e Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices). Each treatment condition was performed in triplicate, and each experiment was repeated at least three times independently.

Determination of cell number in MCF7 cells

MCF7 cells were seeded into six-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells/well and transfected with expression vectors for GFP-tagged TTP family proteins using Lipofectamine 2000. The medium was changed after 20 h transfection and cells were harvested after further 20 h. Cells were stained with trypan blue and counted in a Countess Automated Cell Counter (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Luciferase reporter activity and RNA, endogenous eya mRNA, and MTS cell survival assays were quantified using one-tailed Student's t-test. Drosophila eye size was analyzed using ImageJ and two-tailed Student's t-test.

Results

Overexpression of TIS11 proteins result in a small eye phenotype

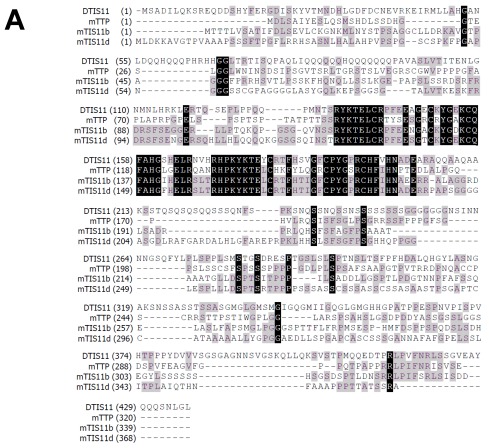

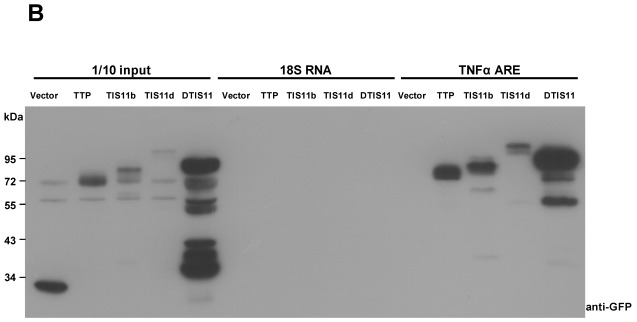

To investigate the biological function of TTP, we used the Drosophila genetic system to express both mouse and fly TIS11. Fig. 1A shows the amino acid sequences of DTIS11 and three mouse TTP family members. The proteins have highly conserved TZF domains, but variable N- and C-terminal sequences. GFP-tagged TTP, TIS11b, TIS11d, and DTIS11 were expressed in HEK293T cells and shown to bind the ARE from TNF using a pull-down assay (Fig. 1B). This indicates that DTIS11 and mouse TTP proteins have similar RNA-binding activity. Moreover, DTIS11 or mouse TIS11b expressed in the fly retina by specific GMR-Gal4 caused an eyes absent or small eye phenotype, respectively (Figs. 2A-C). When DTIS11 was expressed in the fly retina by a pigment cell driver, Lz-Gal4, the number of pigment cells was dramatically reduced and rhabdomere structure was disrupted (Fig. 2E).

Figure 1.

Comparison between Drosophila and mouse TTP family members. (A) Amino acid sequences of Drosophila DTIS11 and mouse TTP family members. (B) HEK293T cells were transiently transfected with GFP vector or GFP-tagged TTP, TIS11b, TIS11d, or DTIS11 expression vectors. After 24 h, cytosolic extracts were isolated and incubated with biotinylated TNF ARE or control 18S rRNA. The pulled down proteins were subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti-GFP.

Figure 2.

Overexpression of DTIS11 proteins in the Drosophila eye. (A-D) Bright field images of fly retinas expressing TIS11 variants by GMR-Gal4. (A, control; B, Drosophila TIS11 [DTIS11]; C, murine TIS11b [mTIS11b]; D, RNA-binding domain mutant DTIS11F158N). (E) Use of the pigment cell driver Lz-Gal4 to express DTIS11 in retina. Pupal eyes (48 h APF) were dissected and labeled by immunohistochemistry (left, control; right, DTIS11 overexpression). Retinal pigment cells were revealed by anti-armadillo staining (green), and rhabdomere structure of photoreceptors was counterstained with phalloidin (red). Scale bar, 10 μm. (F) Immunoblot analysis of total protein from fly heads for expression of DTIS11 and DTIS11F158N. w1118 was used as a non-transgenic control. Numbers below bands indicate amount of protein loaded.

The number of interommatidial cells is known to be precisely regulated by programmed cell death 23,24. The severe reduction in the number of interommatidial cells in this experiment implied that overexpression of DTIS11 induced apoptosis. To narrow down this apoptotic time window and to determine which developmental stage was most affected by DTIS11, we used a temperature-sensitive Gal4 repressor (Gal80ts) 25 to temporally regulate DTIS11 expression in the eye. When DTIS11 overexpression was initiated during pupal development, the eye phenotype was much milder than with the conventional GMR-Gal4, which drives constitutive expression from embryonic stages (Supplementary Material: Fig. S1). Notably, when DTIS11 overexpression commenced at a late pupal stage (~85% after puparium formation [APF]), numerous black spots—typically indicative of apoptosis—were present in the adult retina. Consistent with this observation, the DTIS11-induced small eye phenotype was partially rescued by two apoptosis inhibitors, Drosophila inhibitor of apoptosis (DIAP) and p35 (Supplementary Material: Fig. S2).

Due to TTP family members belonging to RNA-binding proteins, we next tested whether the mRNA-binding capability of DTIS11 was required to cause eye deficits. To this end, we generated a transgenic fly, UAS-DTIS11F158N, expressing a protein in which the TZF RNA-binding domain, which is critical for TTP function 26, was mutated. Interestingly, eyes expressing DTIS11F158N did not exhibit an eyes absent phenotype and were morphologically indistinguishable from wild type (Fig. 2D). Immunoblot analysis confirmed that DTIS11F158N was indeed expressed (Fig. 2F). Although DTIS11F158N was more abundantly expressed than wild-type DTIS11, it did not elicit an aberrant eye appearance without a functional RNA-binding domain. Taken together, our results show that overexpression of DTIS11 in the fly retina leads to eye defects, and that the RNA-binding activity of DTIS11 is required for this phenotype.

eya mRNA is a target of TTP proteins

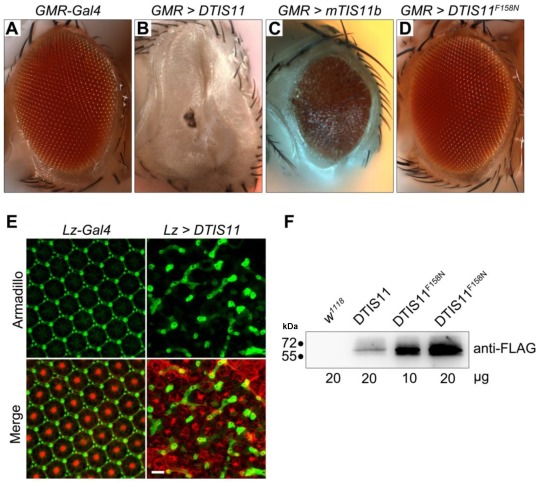

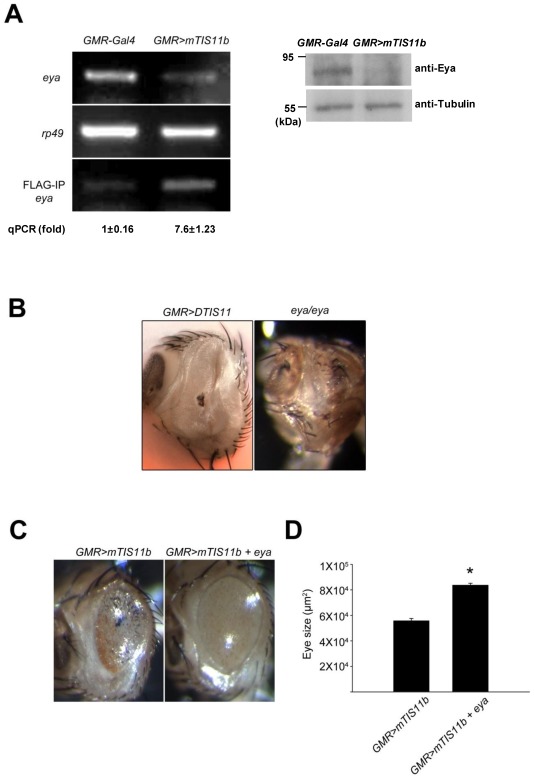

To determine the mechanism by which DTIS11 affects eye development, we attempted to identify its mRNA binding targets by performing RNA-IP. We took a candidate gene approach, concentrating on ARE-containing genes that play a role in apoptosis based on a search of D-ARED data 20. However, the level of DTIS11 protein in the eye was too low for RNA-IP (Fig. 2F), likely because of the reduced amount of eye tissue. Thus, RNA-IP was performed using eyes expressing FLAG-tagged mTIS11b, which elicited a milder phenotype (Fig. 2C). Using FLAG-IP, RNA was isolated for reverse transcription followed by semi-quantitative PCR analysis (Supplementary Material: Fig. S3). The candidate gene eya exhibited a reduction in mRNA and protein level in response to mTIS11b expression (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, eya mRNA and mTIS11b were present in the same complex (Fig. 3A). To confirm that endogenous Eya was downregulated spatially in the fly retina by overexpression of TIS11 proteins, we performed Eya antibody staining in eye imaginal discs. As previously reported 27,28, we found endogenous Eya expressed primarily behind the morphogenetic furrow (Supplementary Material: Fig. S4), where the GMR-Gal4 was specifically expressed. Subsequently, when we knocked down DTIS11 by eq-GAL4-driven RNAi, it resulted in Eya accumulation and expansion in the area before the morphogenetic furrow (Supplementary Material: Fig. S5). Interestingly, the eya null phenotype is quite similar to that seen with DTIS11 overexpression 27 (Fig. 3B). In addition, eya overexpression was able to partially rescue the small eye phenotype caused by TIS11b (Figs. 3C and D). To rule out the possibility of unexpected effects on cell growth from GMR-Gal4 driving UAS-Eya, Eya was overexpressed alone in the fly retina. It did not result in an overgrown eye phenotype (Supplementary Material: Fig. S6), clarifying that Eya overexpression indeed could rescue TIS11b mediated small eye phenotype. These results suggest that eya mRNA is a target of TIS11 proteins in vivo, and that downregulation of eya mRNA by DTIS11 or mTIS11b overexpression may result in the small eye phenotype.

Figure 3.

Identification of eya mRNA as a target of TIS11 proteins in Drosophila. (A) Analysis of eya expression. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR determines the mRNA expression of eya (top) and rp49 (middle), and the level of eya mRNA bound to FLAG-tagged TIS11b (bottom) in control and mouse TIS11b overexpression fly. Numbers indicate amount of RNA-IP reaction analyzed by quantitative PCR. Right panel is immunoblotting analysis with anti-Eya. (B) Eye phenotype resulting from DTIS11 overexpression was similar to the eya mutant. (C) Coexpression of eya with mTIS11b partially rescued the small eye phenotype caused by overexpression of mTIS11b alone. (D) Statistical analysis shows that eya significantly rescued the reduced eye size resulting from mTIS11b overexpression. n = 3; *P = 0.0048 by two-tailed Student's t-test.

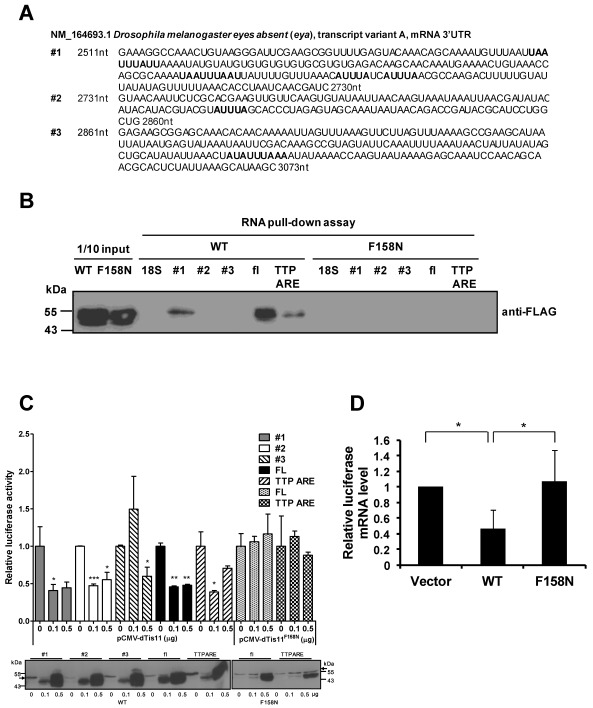

Physical and functional interactions between DTIS11 and the 3′ UTR of eya

To characterize the interaction between eya and DTIS11, the ARE-containing 3′ UTR of eya mRNA was evaluated. The 3′ UTR was isolated and separated into three fragments for binding analyses (Fig. 4A). RNA pull-down experiments indicated that DTIS11 bound to the full-length eya 3′ UTR and to fragment 1 (the most proximal fragment to the coding sequence), but not to fragment 2 or 3 (Fig. 4B). As a positive control, we used the TTP ARE, a well-characterized ARE in the 3′ UTR of mouse TTP mRNA 22. In addition, the DTIS11F158N mutant did not bind the 3′ UTR of eya (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Physical and functional interactions between DTIS11 and 3′ UTR of eya mRNA. (A) Nucleotide sequence of the 3′ UTR of Drosophila eya (GenBank accession no. NM_164693, nt 2511-3073) separated into three fragments (fragment 1, nt 2511-2730; fragment 2, nt 2731-2860; fragment 3, nt 2861-3073). AREs are indicated by bold text. (B) RNA pull-down assay using full-length (FL) eya 3'UTR and eya 3'UTR fragments (#1, #2, and #3) with FLAG-tagged DTIS11 (WT) and DTIS11F158N (F158N). TTP ARE and 18S rRNA were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The pulled down proteins were immunoblotted with anti-FLAG. (C-D) The luciferase gene was fused to full-length eya 3′ UTR or 3′ UTR fragments, and HEK293T cells were cotransfected with a luciferase plasmid and FLAG-DTIS11 or FLAG-DTIS11F158N expression plasmids. A TTP ARE-containing luciferase plasmid served as a positive control. After 24 h, cell lysates were isolated for luciferase activity assays. Relative eya 3′ UTR-mediated luciferase activity is presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. The expression level of wild-type or mutant DTIS11 was determined by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG (the arrows indicate FLAG-luciferase signal) (C). (D) Quantitative PCR was used to determine full-length eya 3'UTR-mediated luciferase mRNA expression. Expression data were normalized to β-galactosidase mRNA and are shown as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05. Duplicate reactions were performed and each experiment was repeated three times.

To carry out reporter assays, we cloned the full-length 3′ UTR and each fragment into the 3′ end of the luciferase gene. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with the luciferase-eya 3′ UTR reporter plasmid plus a FLAG-tagged DTIS11 expression plasmid, and luciferase activity was measured 24 h after transfection. DTIS11 protein levels are shown in the lower panel of Fig. 4C. Consistent with our RNA-protein interaction data, DTIS11 significantly reduced luciferase activity when the full-length 3′ UTR or fragment 1 was tested. Similar results were seen with TTP ARE. Downregulation of luciferase activity by DTIS11 was also reflected in decreased levels of luciferase mRNA (Fig. 4D). In contrast, DTIS11F158N did not affect luciferase activity or RNA expression (Figs. 4C and D). Although fragment 2 did not pull down DTIS11 protein (Fig. 4B), luciferase activity was attenuated by DTIS11 overexpression using this fragment (Fig. 4C). These results demonstrate that DTIS11 binds to the 3′ UTR of eya mRNA (specifically, fragment 1), thereby reducing eya expression.

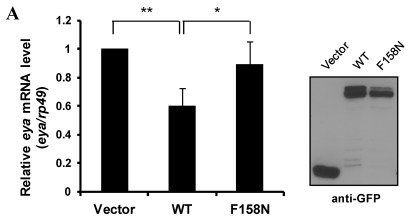

DTIS11 downregulates eya expression and affects viability of S2 cells

To further demonstrate the downregulation of eya mRNA expression by DTIS11, we transfected DTIS11 and DTIS11F158N into Drosophila embryonic S2 cells. Total RNA was isolated and eya mRNA was detected by quantitative PCR. Compared to the empty vector and the RNA-binding mutant DTIS11F158N as negative controls, DTIS11 overexpression significantly decreased eya mRNA levels (Fig. 5A, left panel). Immunoblotting revealed the levels of overexpressed GFP-tagged proteins (Fig. 5A, right panel). Moreover, data from MTS cell viability assays revealed that the viability of cells overexpressing DTIS11 was significantly reduced compared with vector or DTIS11F158N controls (Fig. 5B). Given the low transfection efficiency of S2 cells with Lipofectamine (<40%), dramatic decreases of eya expression and cell viability is unlikely. This indicates that DTIS11 may impair cell viability by destabilizing eya mRNA in S2 cells.

Figure 5.

Overexpression of DTIS11 in S2 cells. (A) Overexpression of DTIS11 decreased eya mRNA expression in S2 cells. S2 cells were transfected with GFP-tagged DTIS11 (WT) or GFP-tagged DTIS11F158N (F158N) expression plasmids. eya expression was determined by quantitative PCR and normalized to rp49 as a negative control (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Levels of GFP-tagged proteins were detected by immunoblotting with anti-GFP. (B) Cell viability analysis. S2 cells were seeded into 96-well plates and transiently transfected with GFP-tagged DTIS11 or DTIS11F158N expression plasmids. After 2 days, cell viability was determined by MTS assay and normalized to vector control (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). Each treatment was performed in triplicate and the experiment was repeated five times.

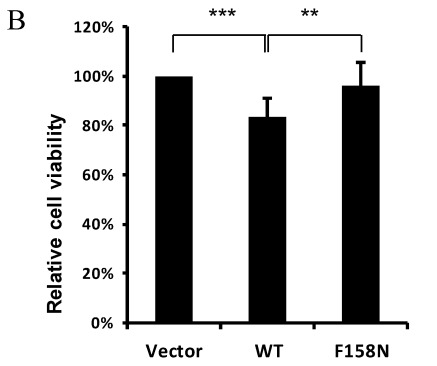

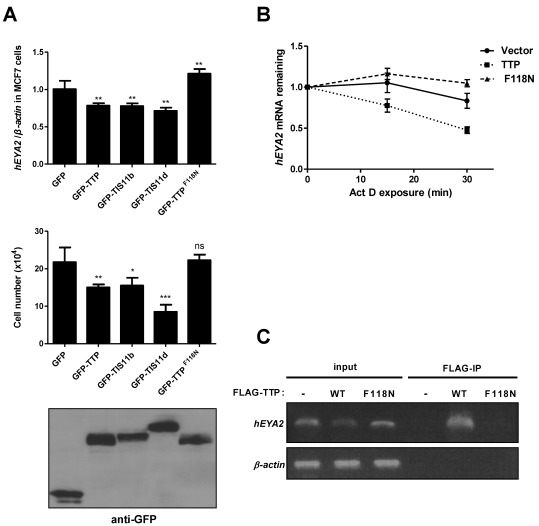

Overexpression of TTP proteins downregulates EYA2 mRNA levels in human breast cancer cells

We next asked whether the interactions between eya mRNA and DTIS11 were evolutionarily conserved. In the human genome, there are four eya homologs (EYA1-4), and each mRNA contains a long 3′ UTR (1905, 709, 4096, and 3314 bp, respectively) with putative AREs based on sequence analysis. Human EYA2 is upregulated in the human breast cancer cell line MCF7 29,30. We transiently overexpressed individual mouse TTP proteins in MCF7 cells and measured EYA2 expression and cell viability. TTP, TIS11b, and TIS11d decreased EYA2 mRNA levels, while the TTPF118N mutant did not (Fig. 6A, top). Trypan blue staining showed that overexpression of wild-type TTP proteins caused a decrease in the number of live cells (Fig. 6A, middle). MTS cell viability analysis was shown in Supplementary Material: Fig. S7A. To determine whether TTP could induce apoptosis in MCF7 cells, we performed immunoblotting for γ-H2AX (Ser139-phosphorylated histone protein H2AX), which is induced by loss of EYA and some apoptotic signals 31-33. Compared to the vector and mutant TTP, overexpression of wild-type TTP increased the γ-H2AX signal (Supplementary Material: Fig. S7B). Furthermore, TUNEL assays showed that wild-type TTP increased the apoptotic response (Supplementary Material: Fig. S7C). To determine whether TTP downregulates EYA2 mRNA levels by accelerating its decay, we measured EYA2 mRNA stability using actinomycin D treatment to block RNA synthesis (Fig. 6B). These data revealed that EYA2 mRNA decayed more rapidly in MCF7 cells expressing TTP than in MCF7 cells expressing GFP or TTPF118N. RNA-IP demonstrated that TTP, but not TTPF118N, was associated with EYA2 mRNA (Fig. 6C). Collectively, these results demonstrate that TTP bound to and destabilized EYA2 mRNA, and that overexpression of TTP proteins decreased viability in MCF7 cells.

Figure 6.

Overexpression of TTP proteins in MCF7 cells. (A) TTP proteins downregulated human EYA2 (hEYA2) expression and cell viability in MCF7 cells. MCF7 cells were transiently transfected with GFP vector or GFP-tagged TTP, TIS11b, TIS11d, or TTPF118N expression vectors. After 40 h, EYA2 expression was measured by quantitative PCR (top), cell viability was measured using trypan blue (middle), and immunoblotting was performed using anti-GFP (bottom). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (B) Determination of EYA2 mRNA stability. MCF7 cells were transiently transfected with GFP-TTP or GFP-TTPF118N expression vectors. A vector-only control was also included. After 40 h, cells were untreated or treated with 10 μg/ml actinomycin D (Act D) for 15 and 30 min. RNA was then isolated for quantitative PCR using EYA2 and β-actin primers. (C) RNA-IP. MCF7 cells were transiently transfected with FLAG-TTP or FLAG-TTPF118N expression vector. A vector-only control was also included. After 24 h, cell lysates were isolated for immunoprecipitation using anti-FLAG M2 beads. RNA was extracted from the precipitated complexes for RT-PCR analysis using EYA2 and β-actin primers.

Discussion

In this study, we overexpressed DTIS11 in the Drosophila retina, resulting in a small eye phenotype due to programmed cell death. In contrast, a mutant DTIS11 in which the RNA-binding TZF domain had been mutated had virtually no effect on the eye. This suggests that RNA-binding activity is critical for DTIS11 function. Using RNA-IP, we identified a novel TIS11 target mRNA, eya. We demonstrated that DTIS11 physically interacted with the 3′ UTR of eya mRNA to reduce mRNA expression. Furthermore, decreased expression of eya was correlated with reduced cell viability in Drosophila S2 and human MCF7 cells. Together, these data indicate that eya mRNA is depleted when TIS11 levels are elevated. In addition, this interaction represents a regulatory mechanism that has been conserved during evolution.

The eya gene was first identified in Drosophila, where it functions to determine retinal cell fate 27. eya mutations lead to an elevated rate of apoptosis in ommatidial precursor cells, preventing development of the compound eye 34,35. In vertebrates, four eya homologs have been identified, each containing an N-terminal transactivation domain and threonine phosphatase domain, and a C-terminal tyrosine phosphatase domain 36. These proteins activate c-myc gene expression for cell proliferation 37, and regulate DNA repair via dephosphorylation of H2AX 31. TTP mRNA and protein levels are significantly decreased in tumors of the thyroid, lung, ovary, uterus, and breast compared to non-transformed tissues 38,39. Restoring TTP expression in an aggressive tumor cell line suppresses cell proliferation and stimulates apoptosis 40. In contrast, EYA levels are upregulated in a number of cancers, including EYA2 in ovarian and breast cancers 29, EYA1 in Wilms' tumor 41, and EYA4 in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors 42. Moreover, overexpression of EYA1, EYA2, or EYA3 increases proliferation, invasion, and transformation of breast cancer cells 43. It appears, therefore, that TTPs and EYAs have inverse patterns of expression and functional effects in tumor cells. This is consistent with our observation that TTP overexpression reduced EYA2 mRNA levels and cell viability. As such, TTP proteins may target eya mRNA to regulate cell survival. However, eya overexpression only partially rescues the small eye phenotype caused by mTIS11b. We also failed to rescue the DTIS11overexpression-induced eyes absent phenotype by coexpression of eya (data not shown). These suggest that other apoptosis-related genes, such as diap1 and a gene encoding the eye-specific transcription factor glass 44 (Supplementary Material: Fig. S3), or other unidentified ARE-containing mRNAs may also be targets of TIS11 proteins and contribute to the phenotypic outcome.

The 3′ UTR of Drosophila eya mRNA contains multiple AREs. To functionally characterize the 3′ UTR, we separated it into three fragments. Fragment 1 contains four AREs, and the other two contain one each. Fragment 1 bound most effectively to DTIS11. Although fragment 2 did not pull down TTP in biochemical experiments, it responded to DTIS11 expression in vivo. A similar effect was observed when TTP regulation of VEGF mRNA was examined 45. In addition, several potential mRNA targets of TTP that were identified in a previous microarray experiment do not contain typical AREs 17,18. This suggests that TTP may regulate the stability of these mRNAs through a binding-independent mechanism. To determine whether TTP regulates eya mRNA stability in mammalian cells, we analyzed the mRNA sequences of four eya homologs. Each had a long 3′ UTR containing putative AREs and U-rich sequences. EYA2 is the predominant EYA family member in MCF7 cells 30. RNA-IP analysis demonstrated that TTP associated with EYA2 mRNA and destabilized it. This implies that overexpression of EYA2 in breast cancer MCF7 cells can be post-transcriptionally downregulated by TTP proteins. The detailed physical and functional interactions between TTP family members and human EYA mRNAs should be further characterized.

When the amino acid sequence of DTIS11 was compared with the mouse homologs TTP, TIS11b, and TIS11d, DTIS11 was most similar to TIS11b and TIS11d (Fig. 1A). These proteins share 90% amino acid identity within the TZF domain, but have quite divergent N- and C-terminal sequences. The TZF domain is responsible for RNA binding, whereas the N- and C-terminal regions recruit the mRNA decay machinery (e.g., deadenylase 46-48, 5′ mRNA decapping 49, and 3′ exosome 50 complexes). In our experiments, DTIS11 was able to downregulate ARE-mediated luciferase activity in HEK293T cells, indicating that interactions between TTP proteins and proteins involved in mRNA decay may have been evolutionarily conserved. Although overexpression of either TIS11b or DTIS11 disrupted Drosophila eye development, the effects seen with TIS11b were less dramatic. Thus, there may be slight differences in the way these two proteins interact with effector proteins. For example, the Cbl-interacting protein CIN85 interacts with the C terminus of human TTP but not with other protein family members 51. It has also been reported that TTP, but not TIS11b, interacts with the Tax protein from human T lymphotropic virus 1 through its C-terminal domain 52.

Studies in animal model systems have demonstrated that TTP plays a critical role in the immune system, whereas TIS11b and TIS11d may function during embryonic development 53-55. Although DTIS11 is most similar to TIS11b and TIS11d at the amino acid level, it is functionally most similar to TTP. For example, DTIS11 regulates the mRNA stability of anti-microbial peptides 10,11. Here, we have identified a novel mRNA target of DTIS11, eya, and provided in vivo evidence that DTIS11 regulates eye development by interacting with and destabilizing eya mRNA, especially during embryogenesis. These observations also suggest that this single gene in Drosophila may be responsible for functions that are carried out by multiple genes in mice and humans.

Supplementary Material

Fig.S1-S7.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Ms. Yi-Li Liu and Ms. I-Ching Huang for technical assistance with DNA sequencing (supported in part by the Department of Medical Research, National Taiwan University Hospital), the Taiwan Fly Core for fly stocks, Mr. Chiou-Yang Tang (IMB, Academia Sinica) for generating transgenic flies, Dr. Ming-Tsan Su (Department of Life Science, National Taiwan Normal University) and Dr. Guang-Chao Chen (IBC, Academia Sinica) for sharing cloning vectors, Dr. Y. Henry Sun (IMB, Academia Sinica) for sharing fly stocks and anti-Eya antibody, and Dr. Sheng-Wei Lin for protein purification support. This study was supported by a grant from Academia Sinica and National Taiwan University (96R0066-33 to M.-S. Chang) and a grant from the National Science Council (NSC97-2311-B-001-019-MY3 to C.-J. Chang).

References

- 1.Fan J, Yang X, Wang W. et al. Global analysis of stress-regulated mRNA turnover by using cDNA arrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(16):10611–16. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162212399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen CY, Shyu AB. AU-rich elements: characterization and importance in mRNA degradation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20(11):465–70. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackshear PJ. Tristetraprolin and other CCCH tandem zinc-finger proteins in the regulation of mRNA turnover. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30(Pt 6):945–52. doi: 10.1042/bst0300945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baou M, Jewell A, Murphy JJ. TIS11 family proteins and their roles in posttranscriptional gene regulation. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2009:634520. doi: 10.1155/2009/634520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackshear PJ, Phillips RS, Ghosh S. et al. Zfp36l3, a rodent X chromosome gene encoding a placenta-specific member of the Tristetraprolin family of CCCH tandem zinc finger proteins. Biol Reprod. 2005;73(2):297–307. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.040527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lai WS, Blackshear PJ. Interactions of CCCH zinc finger proteins with mRNA: tristetraprolin-mediated AU-rich element-dependent mRNA degradation can occur in the absence of a poly(A) tail. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(25):23144–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100680200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai WS, Kennington EA, Blackshear PJ. Tristetraprolin and its family members can promote the cell-free deadenylation of AU-rich element-containing mRNAs by poly(A) ribonuclease. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(11):3798–812. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.11.3798-3812.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carballo E, Lai WS, Blackshear PJ. Feedback inhibition of macrophage tumor necrosis factor-alpha production by tristetraprolin. Science. 1998;281(5379):1001–5. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5379.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carballo E, Lai WS, Blackshear PJ. Evidence that tristetraprolin is a physiological regulator of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor messenger RNA deadenylation and stability. Blood. 2000;95(6):1891–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lauwers A, Twyffels L, Soin R. et al. Post-transcriptional Regulation of Genes Encoding Anti-microbial Peptides in Drosophila. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(13):8973–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806778200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wei Y, Xiao Q, Zhang T. et al. Differential regulation of mRNA stability controls the transient expression of genes encoding Drosophila antimicrobial peptide with distinct immune response characteristics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(19):6550–61. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baou M, Jewell A, Muthurania A. et al. Involvement of Tis11b, an AU-rich binding protein, in induction of apoptosis by rituximab in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2009;23(5):986–9. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson BA, Blackwell TK. Multiple tristetraprolin sequence domains required to induce apoptosis and modulate responses to TNFalpha through distinct pathways. Oncogene. 2002;21(27):4237–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson BA, Geha M, Blackwell TK. Similar but distinct effects of the tristetraprolin/TIS11 immediate-early proteins on cell survival. Oncogene. 2000;19(13):1657–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim CW, Kim HK, Vo MT. et al. Tristetraprolin controls the stability of cIAP2 mRNA through binding to the 3'UTR of cIAP2 mRNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;400(1):46–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.07.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SK, Kim SB, Kim JS. et al. Butyrate response factor 1 enhances cisplatin sensitivity in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Int J Cancer. 2005;117(1):32–40. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai WS, Parker JS, Grissom SF. et al. Novel mRNA targets for tristetraprolin (TTP) identified by global analysis of stabilized transcripts in TTP-deficient fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(24):9196–208. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00945-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stoecklin G, Tenenbaum SA, Mayo T. et al. Genome-wide analysis identifies interleukin-10 mRNA as target of tristetraprolin. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(17):11689–99. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709657200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emmons J, Townley-Tilson WH, Deleault KM. et al. Identification of TTP mRNA targets in human dendritic cells reveals TTP as a critical regulator of dendritic cell maturation. RNA. 2008;14(5):888–902. doi: 10.1261/rna.748408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cairrao F, Halees AS, Khabar KS. et al. AU-rich elements regulate Drosophila gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(10):2636–43. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01506-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen YL, Huang YL, Lin NY. et al. Differential regulation of ARE-mediated TNFalpha and IL-1beta mRNA stability by lipopolysaccharide in RAW264.7 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;346(1):160–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin NY, Lin CT, Chen YL. et al. Regulation of tristetraprolin during differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes. FEBS J. 2007;274(3):867–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolff T, Ready DF. Cell death in normal and rough eye mutants of Drosophila. Dev. 1991;113(3):825–39. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.3.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brachmann CB, Cagan RL. Patterning the fly eye: the role of apoptosis. Trends Genet. 2003;19(2):91–6. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)00041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGuire SE, Roman G, Davis RL. Gene expression systems in Drosophila: a synthesis of time and space. Trends Genet. 2004;20(8):384–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Franks TM, Lykke-Andersen J. TTP and BRF proteins nucleate processing body formation to silence mRNAs with AU-rich elements. Genes Dev. 2007;21(6):719–35. doi: 10.1101/gad.1494707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonini NM, Leiserson WM, Benzer S. The eyes absent gene: genetic control of cell survival and differentiation in the developing Drosophila eye. Cell. 1993;72(3):379–95. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bessa J, Gebelein B, Pichaud F. et al. Combinatorial control of Drosophila eye development by Eyeless, Homothorax, and Teashirt. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2415–7. doi: 10.1101/gad.1009002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang L, Yang N, Huang J. et al. Transcriptional coactivator Drosophila eyes absent homologue 2 is up-regulated in epithelial ovarian cancer and promotes tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2005;65(3):925–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farabaugh SM, Micalizzi DS, Jedlicka P. et al. Eya2 is required to mediate the pro-metastatic functions of Six1 via the induction of TGF-beta signaling, epithelial-mesenchymal transition, and cancer stem cell properties. Oncogene. 2012;31(5):552–62. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook PJ, Ju BG, Telese F. et al. Tyrosine dephosphorylation of H2AX modulates apoptosis and survival decisions. Nature. 2009;458(7238):591–6. doi: 10.1038/nature07849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rogakou EP, Nieves-Neira W, Boon C. et al. Initiation of DNA fragmentation during apoptosis induces phosphorylation of H2AX histone at serine 139. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(13):9390–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mukherjee B, Kessinger C, Kobayashi J. et al. DNA-PK phosphorylates histone H2AX during apoptotic DNA fragmentation in mammalian cells. DNA Repair. 2006;5(5):575–90. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leiserson WM, Benzer S, Bonini NM. Dual functions of the Drosophila eyes absent gene in the eye and embryo. Mech Dev. 1998;73(2):193–202. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonini NM, Leiserson WM, Benzer S. Multiple roles of the eyes absent gene in Drosophila. Dev biol. 1998;196(1):42–57. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jemc J, Rebay I. The eyes absent family of phosphotyrosine phosphatases: properties and roles in developmental regulation of transcription. Ann Rev Biochem. 2007;76:513–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052705.164916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li X, Oghi KA, Zhang J. et al. Eya protein phosphatase activity regulates Six1-Dach-Eya transcriptional effects in mammalian organogenesis. Nature. 2003;426(6964):247–54. doi: 10.1038/nature02083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brennan SE, Kuwano Y, Alkharouf N. et al. The mRNA-destabilizing protein tristetraprolin is suppressed in many cancers, altering tumorigenic phenotypes and patient prognosis. Cancer Res. 2009;69(12):5168–76. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Souhibani N, Al-Ahmadi W, Hesketh JE. et al. The RNA-binding zinc-finger protein tristetraprolin regulates AU-rich mRNAs involved in breast cancer-related processes. Oncogene. 2010;29(29):4205–15. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suswam E, Li Y, Zhang X. et al. Tristetraprolin down-regulates interleukin-8 and vascular endothelial growth factor in malignant glioma cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68(3):674–82. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li CM, Guo M, Borczuk A. et al. Gene expression in Wilms' tumor mimics the earliest committed stage in the metanephric mesenchymal-epithelial transition. Am J Pathol. 2002;160(6):2181–90. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61166-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller SJ, Lan ZD, Hardiman A. et al. Inhibition of Eyes Absent Homolog 4 expression induces malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor necrosis. Oncogene. 2010;29(3):368–79. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pandey RN, Rani R, Yeo EJ. et al. The Eyes Absent phosphatase-transactivator proteins promote proliferation, transformation, migration, and invasion of tumor cells. Oncogene. 2010;29(25):3715–22. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Treisman JE, Rubin GM. Targets of glass regulation in the Drosophila eye disc. Mech Dev. 1996;56(1-2):17–24. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(96)00508-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Essafi-Benkhadir K, Onesto C, Stebe E. et al. Tristetraprolin inhibits Ras-dependent tumor vascularization by inducing vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA degradation. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(11):4648–58. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-06-0570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marchese FP, Aubareda A, Tudor C. et al. MAPKAP kinase 2 blocks tristetraprolin-directed mRNA decay by inhibiting CAF1 deadenylase recruitment. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(36):27590–600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.136473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clement SL, Scheckel C, Stoecklin G. et al. Phosphorylation of tristetraprolin by MK2 impairs AU-rich element mRNA decay by preventing deadenylase recruitment. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31(2):256–66. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00717-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sandler H, Kreth J, Timmers HT. et al. Not1 mediates recruitment of the deadenylase Caf1 to mRNAs targeted for degradation by tristetraprolin. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(10):4373–86. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lykke-Andersen J, Wagner E. Recruitment and activation of mRNA decay enzymes by two ARE-mediated decay activation domains in the proteins TTP and BRF-1. Genes Dev. 2005;19(3):351–61. doi: 10.1101/gad.1282305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hau HH, Walsh RJ, Ogilvie RL. et al. Tristetraprolin recruits functional mRNA decay complexes to ARE sequences. J Cell Biochem. 2007;100(6):1477–92. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kedar VP, Darby MK, Williams JG. et al. Phosphorylation of human tristetraprolin in response to its interaction with the Cbl interacting protein CIN85. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Twizere JC, Kruys V, Lefebvre L. et al. Interaction of retroviral Tax oncoproteins with tristetraprolin and regulation of tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(24):1846–59. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taylor GA, Carballo E, Lee DM. et al. A pathogenetic role for TNF alpha in the syndrome of cachexia, arthritis, and autoimmunity resulting from tristetraprolin (TTP) deficiency. Immunity. 1996;4(5):445–54. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stumpo DJ, Byrd NA, Phillips RS. et al. Chorioallantoic fusion defects and embryonic lethality resulting from disruption of Zfp36L1, a gene encoding a CCCH tandem zinc finger protein of the Tristetraprolin family. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(14):6445–55. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6445-6455.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramos SB, Stumpo DJ, Kennington EA. et al. The CCCH tandem zinc-finger protein Zfp36l2 is crucial for female fertility and early embryonic development. Dev. 2004;131(19):4883–93. doi: 10.1242/dev.01336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig.S1-S7.