Abstract

5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxycytidine triphosphate (EdCTP) was synthesized as a probe to be used in conjunction with fluorescent labelling to facilitate the analysis of the in vivo dynamics of DNA-centered processes (DNA replication, repair and cytosine demethylation). Kinetic analysis showed that EdCTP is accepted as a substrate by Klenow exo- and DNA polymerase β. Incorporation of 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxycytidine (EdC) into DNA by these enzymes is at most modestly less efficient than native dC. EdC containing DNA was visualized using a click reaction with a fluorescent azide, following polymerase incorporation and T4 DNA ligase mediated ligation. Subsequent experiments in mouse male germ cells and zygotes demonstrated that EdC is a specific and reliable reporter of DNA replication in vivo.

Keywords: DNA methylation, DNA replication, DNA demethylation, zygote, nonnative nucleotides

Introduction

With exception for RNA viruses, genetic information of all living organisms is stored and propagated in the form of DNA. Cell proliferation relies on the efficient mechanism of DNA replication while a variety of DNA repair pathways eradicate DNA lesions to preserve the integrity and coding potential of the genome. In addition, genomic DNA frequently contains modified bases such as post-replicative 5-methylation of cytosine (5mC), a critical element of the epigenetic control of the genome.[1] Importantly, each of the above DNA-centered processes has been linked with human pathology[2] necessitating further exploration of all aspects of DNA biology including the dynamics of these processes in vivo.

Cytosine methylation is of particular interest as it contributes to regulation of gene expression,[1] genomic imprinting[3] and transposon silencing[4] in normal development and disease.[5] Historically, DNA methylation has been perceived as a stable modification that can be faithfully propagated in proliferating cells or installed de novo by specialized DNA methyltransferases.[6] Since cytosine methylation is a post-replicative modification, it can be reversed by successive rounds of semi-conservative DNA replication without a need for an active, replication-independent mechanism of DNA demethylation (DdM). Accumulating evidence of dynamic DNA methylation, however, raised a possibility of existence of an active mechanism of DdM.[6–7] Although the chemical mechanism by which active DdM occurs is uncertain, base excision repair (BER) (Scheme 1) has been proposed as a possible pathway.[8] Importantly, this pathway requires DNA polymerase-mediated replacement of mC with a nucleotide from the triphosphate pool. The recent discovery of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (hmC) in cellular DNA adds a layer of complexity to this story.[8d, 9] 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine levels fluctuate in cells and are inversely proportional to those of mC, suggesting that hmC is produced in cells from 5-methylcytosine.[10] The role of hmC in cells is unknown and one possibility is that it is an intermediate in oxidative repair of mC.[11] 5-Methylcytosine repair via hmC could bypass the need for a polymerase during active DdM.

Scheme 1.

Overall proposed mechanism for active DNA demethylation. Note: mC is opposite 2′-deoxyguanosine (G) in DNA.

Chemical tools that report on chemical processes in live or fixed cells are of increasing importance.[12] Those that can be used in conjunction with microscopy are particularly appealing because by utilizing reporter groups that fluoresce at different wavelengths one can detect multiple events/molecules simultaneously.[13] Recently, 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) was used to detect DNA replication in cells.[14] EdU, a thymidine analogue, contains an alkynyl functional group, which replaces the methyl group of thymidine. It is incorporated in DNA via its triphosphate by polymerase(s) during replication. Following incorporation into DNA via its nucleotide triphosphate, EdU was fluorescently labeled by carrying out a copper catalyzed alkyne azide cycloaddition (“click”) reaction with 1 in fixed cells. We envisioned that 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxycytosine (EdC) could be also be used to detect replication in cells and even potentially as a flag for active DdM proceeding through a BER mechanism.

Results and Discussion

Design and synthesis of 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxycytidine triphosphate (EdCTP)

Whether EdC was employed as a general probe for replication or more specifically as one for DdM, we hypothesized that the modified cytosine would be incorporated opposite dG by DNA polymerase(s). General replicative polymerases would act on the corresponding triphosphate during replication and DNA polymerase β would be responsible for incorporating EdC when DdM proceeds via the BER mechanism.

| (1) |

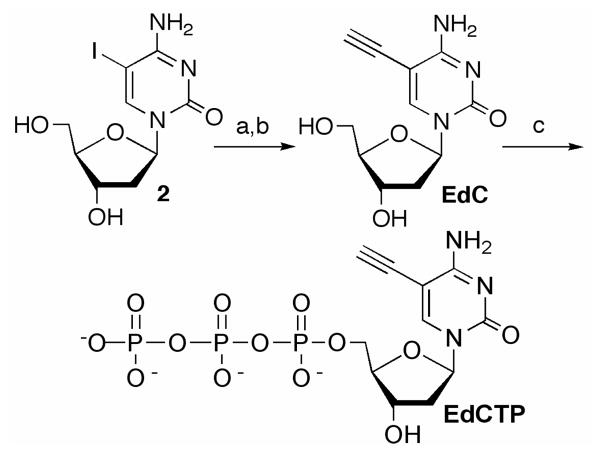

EdC was synthesized from 5-iodo-2′-deoxycytidine (2) via Sonogashira coupling of trimethylsilyacetylene (Scheme 2). The Pd(0) mediated coupling reaction between alkynes and unprotected nucleosides has been used to prepare similar compounds, including EdU.[15] EdC was obtained (80% overall yield from 2) upon desilylation of the Pd(0) coupling product, and transformed into 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxycytidine triphosphate (EdCTP) via standard procedures (Scheme 2).[16] The crude triphosphate was isolated using gravity chromatography on DEAE cellulose. Fractions containing the desired triphosphate product and the side products (monophosphate and diphosphate) were detected via UV spectroscopy monitoring at 291 nM. Final purification of EdCTP was carried out using a MonoQ 5/50 GL anion exchange column.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of EdCTP. a) Pd(dba)2, PPh3, TMS-acetylene b) K2CO3, MeOH c) i. (MeO)3PO, Cl3PO ii. Tributylammonium pyrophosphate.

EdC incorporation by DNA polymerases

EdC incorporation efficiency was initially examined under steady-state conditions using the Klenow fragment of E. coli DNA polymerase I, which lacks any exonuclease activity (Klenow exo-) and compared directly with that of dC.[17] Klenow exo- is often employed as a model of a replicative polymerase. Primer-template duplex 5′-32P-3 (50 nM) was incubated with Klenow exo-(0.5 nM) and various concentrations of EdCTP or dCTP at room temperature for 5 min. The intensities of the starting material band (I0) and the product band (It) were quantified. The rates of reaction were calculated using Eqn. 1, where t is the reaction time.[17] Apparent Km and Vmax were derived by fitting the rate-concentration plot to a hyperbola curve (See Supporting Information for representative plots.). The apparent Km and Vmax of EdCTP were almost the same as dCTP and the incorporation efficiency of EdC is only slightly lower than dC (Table 1). In addition, complete extension was achieved within 10 min when the primer-template complex 5′-32P-3 (100 nM) was incubated with Klenow exo- (4 nM) in the presence of excess dNTPs (50 μM, dATP, dTTP, dGTP and EdCTP) (See Supporting Information). Any difference between the extension of 3 using EdCTP and dCTP was imperceptible under identical conditions, indicating that multiple molecules of EdC were efficiently incorporated by Klenow exo-.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters for nucleotide incorporation in 3 by Klenow exo-a.

| Substrate | Km (nM) | Vmax (%·min−1) | Vmax/Km (%·min−1nM−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| dCTP | 11.6 ± 2.8 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 0.14 |

| EdCTP | 14.5 ± 3.6 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 0.10 |

Data are the average of 3 experiments each consisting of 3 replicates.

EdC incorporation in DNA during active DdM that proceeds via deglycosylation requires that EdCTP be accepted as the substrate by Pol β, which is the enzyme responsible for gap filling during BER.[18] Primer-template duplex 5′-32P-4 was used in these experiments in order to mimic the CpG context in which DNA methylation is frequently associated. Incorporation kinetics for EdC and dC were carried out by Pol β (0.5 nM) at room temperature for 5 min using 5′-32P-4 (50 nM) as described above with Klenow exo- (See Supporting Information). Pol β incorporated EdC ~4-fold less efficiently than it did dC (Table 2). This was attributable to an ~2-fold higher Km and one half as high Vmax. Furthermore, no incorporation of EdC (500 nM) by Pol β (0.5 nM) opposite dT, dC or dA in a primer-template (50 nM) was detected after a 20 min reaction at room temperature (Data not shown), indicating that EdC was selectively incorporated opposite dG.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters for nucleotide incorporation in 4 by Pol βa.

| Substrate | Km (nM) | Vmax (%·min−1) | Vmax/Km (%·min−1nM−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| dCTP | 88.3 ± 7.5 | 5.8 ± 1.0 | 0.07 |

| EdCTP | 150.1 ± 25.0 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 0.017 |

Data are the average of 3 experiments each consisting of 3 replicates.

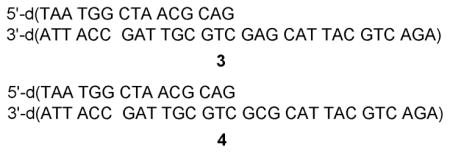

Proof of principle: EdC incorporation into DNA, ligation, and fluorescenc tagging

The precedent setting EdU chemistry and efficient polymerase incorporation of EdC suggested that copper catalyzed alkyne azide cyclization click chemistry would be useful for fluorescence labeling of DNA containing this modified nucleotide.[14, 19] To test this concept complex 6 (2 μM) was prepared by hybridizing 5 (2μM) with the remaining components (4 μM each). In order to push the 5′-phosphorylation of 5 to completion the radiolabeling reaction was chased with cold ATP. Complex 6, containing two single-nucleotide gaps opposite dG was incubated with Pol β (10 nM) in the presence of EdCTP (1 μM) at room temperature for 30 min (Scheme 3). The resulting nicked product was sealed by incubating with T4 DNA ligase (50 nM) in the presence of ATP (1 mM) at room temperature overnight. The duplex containing EdC was passed through a Sephadex-G25 size exclusion column to remove excess EdCTP. The click reaction on 7 was carried out using fluorescein azide 1 (1mM) in the presence of catalyst 9 (1 mM) at 37 °C for 3 h to prevent DNA degradation (Scheme 3).[20] The fluorophore conjugated DNA was then precipitated from NaOAc/EtOH. The radiolabeled products were analyzed on a phosphorimager (Figure 1, Lanes: 1–4), whereas the fluorescence signal was visualized using a Typhoon imager by exciting the molecule at 488 nm and detecting the emission at 526 nm (Figure 1, Lane 5). Full length ligated product was produced in ~80% yield using EdCTP as substrate. The yield was almost the same as the reaction using dCTP (Figure 1, Lanes 2 and 3), and a small amount of partially ligated product (27mer) was observed.

Scheme 3.

Incorporation and fluorescent labelling of EdC.

Figure 1.

Image of EdC incorporation into 7 and subsequent fluorescent labelling with 1 (Per Scheme 3). Lanes: 1, 5′-32P-5; 2, Reaction of 6 using dCTP; 3, Reaction of 6 using EdCTP; 4, Formation of 8 and detection using 32P; 5, Fluorescence detection of reaction in lane 4.

Click product 8 migrated slightly more slowly than 7 through the PAGE gel (Figure 1, lane 4). The fluorescence signal of the full length ligated material co-migrated with the radiolabeled full length product on the same PAGE gel (Figure 1, Lanes 4 and 5). Fluorescence detection revealed products (10, 11) that were not observed using radionuclide detection. We assumed that these additional products resulted from hybridization of 5 with excess primers and template during the preparation of 6, resulting in complexes 12 and 13. The additional fluorescent products could result from EdC incorporation in these complexes, followed by labeling with 1 (Figure 1, Lane 5). This hypothesis was verified using independently prepared complexes 12 and 13. EdC was incorporated by Pol β, followed by nick sealing using T4 DNA ligase and fluorescence labeling using fluorescent azide 5. The fluorescence signals generated from 12 and 13 (See Supporting Information) exhibited the same migration as those observed only via fluorescence from complex 6 (Figure 1). The doubling of bands designated as 10 (Figure 1) could be due to a mixture of products containing one and two fluoresceins. Similarly, one or two molecules of EdC can be incorporated in 13, giving rise to two products marked as 11 (Figure 1). Overall, these observations indicated that EdC and click chemistry can be used to detect gapped DNA.

EdC for labeling of replicating DNA in mouse male germ cells and zygotes

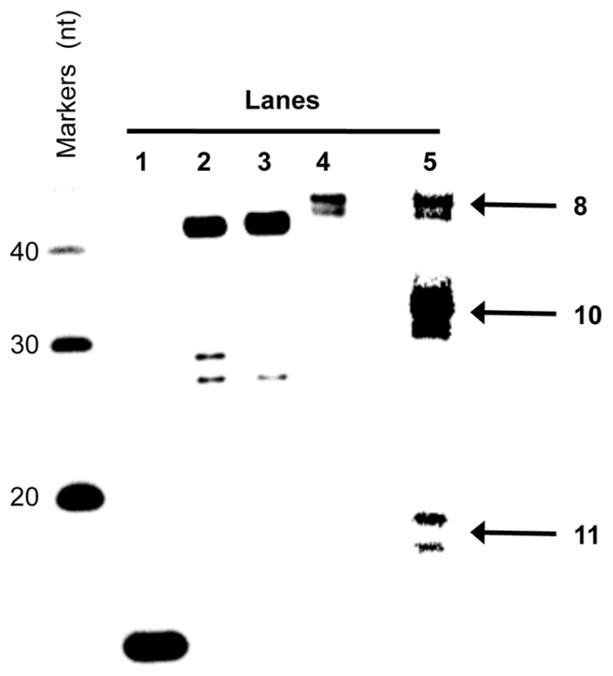

To assess the utility of EdC as a reporter of DNA-centered processes in vivo, we examined EdC incorporation in genomes of mouse male germ cells. Spermatogenesis is a prolonged, multistep process during which diploid spermatogonia proliferate until the initiation of meiotic prophase I, an extended preparatory stage for meiotic divisions.[21] Germ-cell genomes are replicated for the last time before meiotic prophase I in preleptonema. As meiotic cells (spermatocytes) and post-meiotic spermatids do not replicate DNA, testicular germ cell suspensions provide an excellent opportunity to determine the specificity of EdC labeling of replicating DNA in live cells. This is further facilitated by the fact that spermatogonia and spermatocytes can be reliably differentiated using antibodies to proteins (such as SYCP2 protein [22]) specific to chromosome axial elements (AE) and the synaptonemal complex (SC) of meiotic cells.

Testicular germ cell suspensions of adult mice were cultured for 24 hrs in the presence of 48 μg/ml of EdC.[23] Incorporated EdC was visualized via the click reaction with fluoresceinylated azide in surface-spread germ-cell nuclei. Consistent with the results of our in vitro experiments, EdC was readily detected in nuclei of spermatogonia identified by the appearance of knobs of DAPI-stained alpha-satellite DNA and absence of SYCP2 (Figure 2A and 2B). SYCP2-positive spermatocytes fell into two classes -those with and without the EdC signal. EdC-positive spermatocytes contained very short stretches of SYCP2 staining (Figure 2A) characteristic of early meiotic prophase I (leptotene) spermatocytes. Since the last S-phase completes ~16 hrs before leptonema, we concluded that EdC/SYCP2 double-labeled spermatocytes are those cells that completed the S-phase and initiated meiotic prophase I while already in culture. In contrast, no EdC incorporation was found in pachytene spermatocytes with fully developed SCs that have replicated their DNA ~70 hrs before the start of the labeling experiment (Figure 2B). These results suggest that exogenous EdC is efficiently and specifically incorporated in replicating genomes and has no immediate toxic effect on germ cells or meiotic initiation.

Figure 2.

A) Epifluorescent image of nuclei of mouse male germ cells cultured in the presence of EdC for 24 hrs. Nuclei surface spreads were stained with DAPI to identify genomic DNA, click-reacted to reveal EdC and probed with antibody against SYCP2 protein to reveal AEs in leptotene spermatocyte. B) An example of lacking EdC incorporation into the non-replicating genome of a pachytene spermatocyte. Two adjacent spermatogonial nuclei exhibit EdC-labeling of late-replicating regions of the genome.

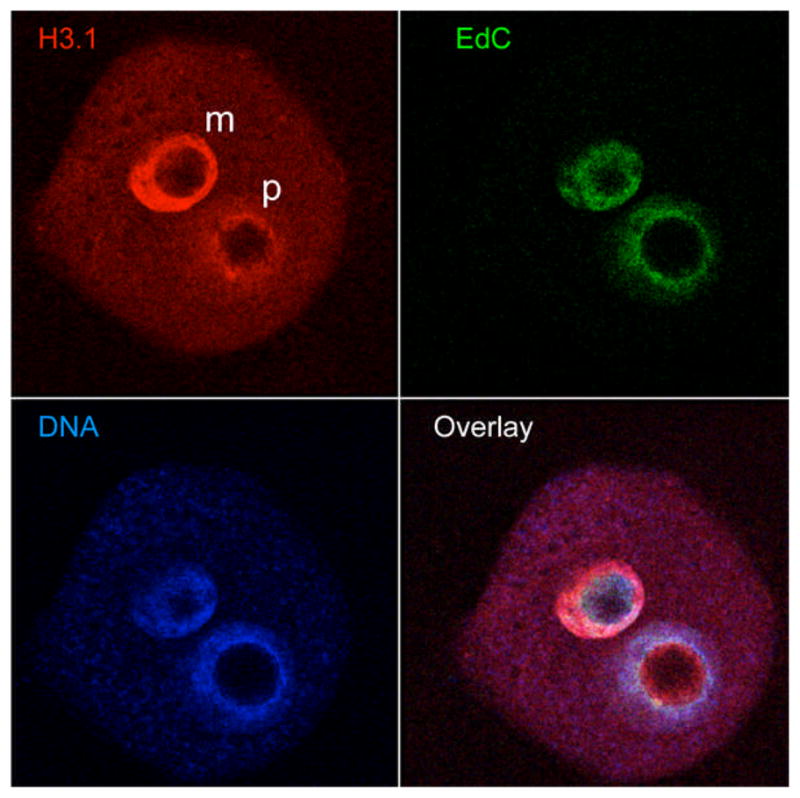

We next assessed the utility of EdC for analysis of DNA replication and cytosine demethylation in mouse zygotes. Following fertilization, the two parental genomes exist as individual pronuclei for up to 10 hrs of time until the completion of the first embryonic S-phase.[7f] Previous studies of the dynamics of 5mC in mouse zygotes using anti-5mC polyclonal antibodies revealed appreciable reduction in paternal genome 5mC content at pronuclear stage 3 (PN3) zygotes (pronuclear staging according to ref. [24]) or approximately 4–6 h post fertilization and before the first S-phase.[7f, 24–25] Based on this knowledge, we anticipated observing EdC incorporation in the paternal genome before the onset of the first embryonic S-phase. Accordingly, naturally fertilized oocytes were retrieved from females after a 3-hour mating period and cultured for 4–6 h in the EdC-containing media to yield PN2 - PN4 zygotes. To monitor the first embryonic S-phase independent of EdC incorporation, we used antibodies to histone H3.1 that is initially absent from the sperm-derived paternal chromosomes but is assembled from the oocyte protein stores into chromatin in the course of DNA replication.[26] We did not observe appreciable EdC incorporation in paternal genome of zygotes before late PN3-PN4 stage (data not shown and Figure 3). Relatively low level of H3.1 immunofluorescence in the paternal pronucleus of late PN3-PN4 zygotes suggested ongoing DNA replication (labeled p in Figure 3). However, the majority of the H3.1 signal was limited to the rim lacking genomic DAPI-stained DNA. In contrast, EdC incorporation, detected via the click reaction, was apparent throughout the paternal genome. The maternal genome also incorporated EdC in PN3-PN4 stage zygotes likely as the consequence of ongoing replication of maternal DNA. Absence of EdC incorporation into the paternal DNA prior to the S-phase could result from EdC incorporation below the detection limit, temporal proximity of DdM/BER and DNA replication, DdM via a BER-independent mechanism. One insight into the observed pattern of EdC incorporation in this experiment comes from a recent study of the dynamics of hmC, a potential intermediate of active DdM, in mouse zygotes.[10a] The authors reported that paternal hmC levels begin to rise in early PN3 zygotes right before the onset of the S-phase and peak in late PN3-PN4, during the S-phase. If BER is indeed the final step in the mechanism of active DdM, then EdC incorporation should immediately precede or coincide with DNA replication. These observations open a possibility for future experiments that could combine in vitro fertilization and DNA replication inhibitor aphidicolin to further clarify the mechanism and dynamics of active DdM in at the onset of mammalian development.

Figure 3.

Laser confocal image of a mouse zygote triple-labeled to reveal histone H3.1, EdC and genomic DNA following 6 hr incubation in the presence of EdC. m and p - maternal and paternal pronuclei, respectively.

Conclusion

In this study we synthesized 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxycytidine (EdC) and 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxycytidine triphosphate (EdCTP). These new reagents can be used as reporters of DNA synthesis in vitro and in vivo. Incorporated EdC is readily detected using commercially available click reaction reagents. EdC can be used as a mechanism-based tool to further explore the chemical mechanism of DdM. Finally, we anticipate that EdC-containing DNA fragments can be purified from complex DNA mixtures such as fragmented genomic DNA using biotinylated azide and streptavidin-conjugated beads.

Experimental Section

General Methods

Oligonucleotides were synthesized on an Applied Biosystems Incorporated 394 oligonucleotide synthesizer. Oligonucleotide synthesis reagents were purchased from Glen Research (Sterling, VA). All chemicals were purchased from either Sigma-Aldrich or Fisher and were used without further purification. Thermostable inorganic pyrophosphatase, BSA, dNTPs, T4 polynucleotide kinase and T4 DNA ligase were obtained from New England Biolabs. DNA polymerase β was obtained from Trevigen. γ-32P-ATP was purchased from Perkin Elmer. C18-Sep-Pak cartridges were obtained from Waters. Quantification of radiolabeled oligonucleotides was carried out using a Molecular Dynamics Phosphorimager 840 equipped with ImageQuant TL 7.0 software. Fluorescently labeled oligonucleotides were detected on a GE/Amersham Typhoon 9410 Variable Mode Imager.

Pd(0) coupling product

A solution of 2 (100 mg, 0.28 mmol), Pd(dba)2 (17.2 mg, 0.03 mmol), CuI (11.4 mg, 0.06 mmol) in dry DMF was bubbled with a stream of argon for 30 min. Et3N (139.2 mg, 200 μL, 1.42 mmol) and PPh3 (31.4 mg, 0.12 mmol) was added. After stirring for 5 min, trimethylsilylacetylene (33 mg, 0.34 mmol) was added to the solution. The resulting mixture was stirring at 25 °C for 4 h under argon. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by column chromatography (100% CH2Cl2 to 10% MeOH in CH2Cl2) to give the silylated alkyne product (77.2 mg, 84%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6)δ 0.21 (s, 9H), 1.98–2.14 (m, 2H), 3.58 (m, 2H), 3.78 (m, 1H), 4.20 (m, 1H), 5.07 (t, 1H, J = 4.8 Hz), 5.20 (d, 1H, J = 4.0 Hz), 6.09 (d, 1H, J = 6.4 Hz), 6.62 (brs, 1H), 7.79 (brs, 1H), 8.20 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ −0.1, 40.8, 60.9, 70.0, 85.4, 87.4, 89.6, 96.9, 99.6, 145.3, 153.2, 163.9; IR (neat) 3326, 2957, 2926, 2154, 1645, 1598, 1504, 1412, 1299, 1250, 1095, 1058, 954, 846, 784, 760 cm−1; FAB-HRMS (M+ + H) for C14H22N3O4Si: calcd 324.1379 found 324.1377.

Synthesis of EdC

A solution of the above coupling product (71 mg, 0.22 mmol) in MeOH (10 mL) was stirred with K2CO3 (61 mg, 0.45) at 25 °C for 3 h. The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by column chromatography (20% MeOH in CH2Cl2) to give EdC (52.7 mg, 96%). 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 2.00 (m, 1H), 2.17 (m, 1H), 3.60 (m, 2H), 3.79 (m, 1H), 4.21 (m, 1H), 4.31 (d, 1H, J = 1.2 Hz), 5.05 (t, 1H, J = 4.4 Hz), 5.20 (d, 1H, J = 4.4 Hz), 6.10 (d, 1H, J = 6.8 Hz), 6.77 (brs, 1H), 7.66 (brs, 1H), 8.24 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 40.9, 60.9, 69.9, 75.9, 85.4, 85.8, 87.4, 88.8, 145.4, 153.3, 164.2; IR (neat) 3274, 2930, 1645, 1600, 1503, 1297, 785, 614 cm−1; FAB-HRMS (M+ + H) for C11H13N3O4: calcd 252.0984, found 252.0982.

Synthesis of EdCTP

Proton sponge (64 mg, 0.3 mmol) and EdC (50 mg, 0.2 mmol) were azeotropically dried with toluene three times before dissolving in trimethyl phosphate (2 mL). Freshly distilled phosphorus oxychloride (61.2 mg, 36.5 μL, 0.4 mmol) was added at 0 °C. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 2 h. A solution of tributylamine (250 μL) and tributylammonium pyrophosphate (548 mg, 1 mmol) in DMF (2 mL) was added. The mixture was stirred for another 5 min. The reaction was quenched with TEAB (0.2 M, 15 mL, pH 7.5). The solution was lyophilized to dryness. The crude product was dissolved in 2 mL water and loaded onto a DEAE-cellulose column (10 cm × 1.5 cm). The column was washed with 50 mL water and eluted with a gradient from 100% water to 0.5 M TEAB (pH 7.5). The UV-active fractions were collected and lyophilized to dryness. The crude triphosphate product was purified by FPLC (0.1 M TEAB, 1M TEAB (0–30%, over 30 min)) using a MonoQ 5/50 GL anion exchange column (GE) to give EdCTP as its triethylammonium salt. 1H NMR (D2O) δ 1.27 (t, 36H, J = 7.2 Hz), 2.30–2.47 (m, 2H), 3.19 (q, 24H, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.77 (s, 1H), 4.21 (m, 3H), 4.60 (m, 1H), 6.26 (m, 1H), 8.23 (s, 1H). 31P NMR (D2O) δ −10.8 (d, 1P, J = 19.4 Hz), −11.6 (d, 1P, J = 19.4 Hz), −23.3 (t, J = 19.4 Hz). F MS (M- - H) for C11H15N3O13P3, calcd 490.2, found 489.8.

Kinetic study of incorporation of EdCTP by Klenow exo- or Pol β

Klenow exo- or Pol β (0.44 pmol) was treated with inorganic pyrophosphatase (0.3 U) and BSA (1 mg/mL, 160 nM) at room temperature for 10 min. The pre-treated enzyme solution (32.7 μL) that contains 0.4 pmol Klenow exo- or Pol β was mixed with primer-template duplex 5′-32P-3 (50 nM, for Klenow exo-) or 5′-32P-4 (50 nM, for Pol β) in Tris·HCl (300 μL, 10 mM, 160 nM BSA, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM, DTT, pH 7.9). The polymerase (1 nM Klenow exo- or Pol β)/primer/template (100 nM) solution (5 μL) was mixed with 2 × dNTP (5 μL, 10–500 nM EdCTP or dCTP for Klenow exo-, 100–900 nM EdCTP or 25–500 nM dCTP for Pol β). The reaction was incubated at room temperature for 5 min. The reaction was quenched with formamide loading buffer (20 μL, 90%, 10 mM EDTA). The mixture was heated to 90 °C for 2 min and cooled on ice. An aliquot (5 μL) of the mixture was loaded on to a 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The intensities of the starting material band (I0) and the product band (It) were quantified. Apparent Km and Vmax were derived by fitting the rate-concentration plot to a hyperbola curve (velocity = Vmax[dNTP]/(Km + [dNTP]).

Incoporation of EdCTP opposite dT, dC and dA in 5′-32P-4

The experimental conditions are similar to those in the kinetic study except that 0.5 nM Pol β, 50 nM primer-template 5′-32P-4 and 500 nM of EdCTP in a total 20 μL reaction solution were used. An aliquot (4 μL) of the reaction mixture was removed and quenched with formamide loading buffer (20 μL, 95%, 10 mM EDTA) at the indicated times (5, 10, and 20 min). The mixture was heated to 90 °C for 2 min and chilled on ice. An aliquot of the mixture (5 μL) was loaded on to a 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel.

Preparation of complex 32P-6

Oligonucleotide 5 (10 μM) was incubated with γ-32P-ATP (50 μCi) and T4 DNA polynucleotide kinase (T4 PNK, 50 U) in Tris·HCl (50 μL, 10 mM, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM, DTT, pH 7.9) at 37 °C for 45 min. The solution was then incubated with ATP (1 mM) at 37 °C for another 75 min. The reaction mixture was heated at 65 °C for 20 min to inactivate T4 PNK, followed by passing through a Sephadex-G25 size exclusion column to afford a 5′-P-5 (containing 5′-32P-5) stock solution (10 μM). The middle oligonucleotide in 6 (10 μM) was incubated with T4 PNK (100 U) in Tris·HCl (100 μL, 10 mM, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM, DTT, 1 mM ATP, pH 7.9) at 37 °C for 2 h. The reaction mixture was then heated at 65 °C for 20 min to inactivate T4 PNK and used without any further purification. The complex 32P-6 (2 μM) was formed by hybridizing the unlabeled oligonucleotide fragments (4 μM) and 5′-P-9 (containing 5′-32P-9, 2 μM), with the template (4 μM) in Tris·HCl (100 μL, 10 mM, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM, DTT, pH 7.9). The DNA was heated at 90 °C for 5 min, slowly cooled to room temperature, and kept at 4 °C overnight.

Fluorescein labeling of DNA containing EdC

Complex 32P-6 (100 nM) was incubated with Pol β (10 nM) in the presence of EdCTP (1 μM) in Tris·HCl (80 μL, 10 mM, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM ATP, pH 7.9) at 37 °C for 30 min. The reaction was then incubated with T4 DNA ligase (250 nM) at room temperature overnight. The material was purified by Sephadex-G25 size exclusion column to remove the excess EdCTP. The resulting solution was incubated with fluorescein azide 1 (1 mM) and Cu(I) catalyst 9 (1 mM) at 37 °C for 2 h.[20] The DNA was precipitated from NaOAc/EtOH twice and analyzed using a GE/Amersham Typhoon 9410 Variable Mode Imager.

Mouse testicular cell culture and cell labeling

CD1 mice (Charles River) were used in these experiments. Testis dissection and culture were performed according to published method.[23] Culture media was supplemented with 48 μg/ml EdC. Meiotic surface spreads were prepared and stained as described previously.[27] EdC was detected using reagents from Click-iT kit (Invitrogen). Guinea pig polyclonal SYCP2 antibodies were described previously.[22]

Zygote isolation and staining

CD1 female mice were caged with CD1 males (3 h) 6 h after assumed time of ovulation. Zygotes were collected from ovarian ampules and cultured in KSOM media supplemented with 48 μg/ml EdC. After 4–6 h of culture zygotes were freed from cumulus cells and processed for fibrin clot embedding as described previously.[28] Mouse monoclonal anti-H3.1 antibody #34 is described previously.[26] EdC was detected using reagents from Click-iT kit (Invitrogen).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

MMG is grateful for support from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (GM-063028). AB is supported by Carnegie Institution for Science. GVDH was a Hollaender Fellow. We thank Johan van der Vlag for H3.1 and P. Jeremy Wang for SYCP2 antibodies.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.chembiochem.org or from the author.

Contributor Information

Dr. Alex Bortvin, Email: bortvin@ciwemb.edu.

Prof. Dr. Marc M. Greenberg, Email: mgreenberg@jhu.edu.

References

- 1.Jones PA, Takai D. Science. 2001;293:1068–1070. doi: 10.1126/science.1063852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Gopalakrishnan S, Van Emburgh BO, Robertson KD. Mutat Res. 2008;647:30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lange SS, Takata K, Wood RD. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:96–110. doi: 10.1038/nrc2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Preston BD, Albertson TM, Herr AJ. Semin Cancer Biol. 2010;20:281–293. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Sharma, Kelly TK, Jones PA. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:27–36. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reik W, Walter JC. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:21–32. doi: 10.1038/35047554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Bourc’his D, Bestor TH. Nature. 2004;431:96–99. doi: 10.1038/nature02886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Walsh CP, Chaillet JR, Bestor TH. Nat Genet. 1998;20:116–117. doi: 10.1038/2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yoder JA, Walsh CP, Bestor TH. Trends Genet. 1997;13:335–340. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Jones PA, Baylin SB. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrg816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chen RZ, Pettersson U, Beard C, Jackson-Grusby L, Jaenisch R. Nature. 1998;395:89–93. doi: 10.1038/25779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ooi SK, Bestor TH. Cell. 2008;133:1145–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Hajkova P, Erhardt S, Lane N, Haaf T, El-Maarri O, Reik W, Walter J, Surani MA. Mech Dev. 2002;117:15–23. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jost JP, Jost YC. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10040–10043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kangaspeska S, Stride B, Metivier R, Polycarpou-Schwarz M, Ibberson D, Carmouche RP, Benes V, Gannon F, Reid G. Nature. 2008;452:112–115. doi: 10.1038/nature06640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kress C, Thomassin H, Grange T. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11112–11117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601793103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Metivier R, Gallais R, Tiffoche C, Le Peron C, Jurkowska RZ, Carmouche RP, Ibberson D, Barath P, Demay F, Reid G, Benes V, Jeltsch A, Gannon F, Salbert G. Nature. 2008;452:45–50. doi: 10.1038/nature06544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Santos F, Hendrich B, Reik W, Dean W. Dev Biol. 2002;241:172–182. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Hajkova P, Jeffries SJ, Lee C, Miller N, Jackson SP, Surani MA. Science. 2010;329:78–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1187945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rai K, Huggins IJ, James SR, Karpf AR, Jones DA, Cairns BR. Cell. 2008;135:1201–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Barreto G, Schäfer A, Marhold J, Stach D, Swaminathan SK, Handa V, Döderlein G, Maltry N, Wu W, Lyko F, Niehrs C. Nature. 2007;445:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nature05515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kriaucionis, Heintz N. Science. 2009;324:929–930. doi: 10.1126/science.1169786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, Agarwal S, Iyer LM, Liu DR, Aravind L, Rao A. Science. 2009;324:930–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Wossidlo M, Nakamura T, Lepikhov K, Marques CJ, Zakhartchenko V, Boiani M, Arand J, Nakano T, Reik W, Walter J. Nat Commun. 2011;2:241. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Pastor WA, Pape UJ, Huang Y, Henderson HR, Lister R, Ko M, McLoughlin EM, Brudno Y, Mahapatra S, Kapranov P, Tahiliani M, Daley GQ, Liu XS, Ecker JR, Milos PM, Agarwal S, Rao A. Nature. 2011;473:394–397. doi: 10.1038/nature10102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Williams K, Christensen J, Pedersen MT, Johansen JV, Cloos PAC, Rappsilber J, Helin K. Nature. 2011;473:343–348. doi: 10.1038/nature10066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wu H, D’Alessio AC, Ito S, Xia K, Wang Z, Cui K, Zhao K, Eve Sun Y, Zhang Y. Nature. 2011;473:389–393. doi: 10.1038/nature09934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ficz G, Branco MR, Seisenberger S, Santos F, Krueger F, Hore TA, Marques CJ, Andrews S, Reik W. Nature. 2011;473:398–402. doi: 10.1038/nature10008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Wu X, Liu H, Liu J, Haley KN, Treadway JA, Larson JP, Ge N, Peale F, Bruchez MP. Nat Biotech. 2003;21:41–46. doi: 10.1038/nbt764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Newman RH, Fosbrink MD, Zhang J. Chem Rev. 2011;111:3614–3666. doi: 10.1021/cr100002u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dai N, Guo J, Teo YN, Kool ET. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:5105–5109. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salic A, Mitchison TJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2415–2420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712168105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Yu CS, Oberdorfer F. Synlett. 2000:86–88. [Google Scholar]; b) Rai D, Johar M, Manning T, Agrawal B, Kunimoto DY, Kumar R. J Med Chem. 2005;48:7012–7017. doi: 10.1021/jm058167w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burgess K, Cook D. Chem Rev. 2000;100:2047–2059. doi: 10.1021/cr990045m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Creighton S, Bloom LB, Goodman MF. Methods Enzymol. 1995;262:232–256. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)62021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Srivastava DK, Vande Berg BJ, Prasad R, Molina JT, Beard WA, Tomkinson AE, Wilson SH. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21203–21209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Horton JK, Baker A, VandeBerg BJ, Sobol RW, Wilson SH. DNA repair. 2002;1:317–333. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(02)00008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2002;41:2596–2599. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Özcubukcu S, Ozkal E, Jimeno C, Pericas MA. Org Lett. 2009;11:4680–4683. doi: 10.1021/ol9018776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.a Oakberg EF. Am J Anat. 1956;99:507–516. doi: 10.1002/aja.1000990307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Oakberg EF. Nature. 1957;180:1137–1138. doi: 10.1038/1801137a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang F, De La Fuente R, Leu NA, Baumann C, McLaughlin KJ, Wang PJ. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:497–507. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200603063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.La Salle S, Sun F, Handel MA. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;558:279–297. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-103-5_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adenot PG, Mercier Y, Renard JP, Thompson EM. Development. 1997;124:4615–4625. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.22.4615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Santos F, Dean W. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;325:129–137. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-005-7:129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Heijden GW, Dieker JW, Derijck AA, Muller S, Berden JH, Braat DD, van der Vlag J, de Boer P. Mech Dev. 2005;122:1008–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.a) Peters AH, Plug AW, van Vugt MJ, de Boer P. Chromosome Res. 1997;5:66–68. doi: 10.1023/a:1018445520117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Soper SF, van der Heijden GW, Hardiman TC, Goodheart M, Martin SL, de Boer P, Bortvin A. Dev Cell. 2008;15:285–297. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.a) Baart EB, de Rooij DG, Keegan KS, de Boer P. Chromosoma. 2000;109:139–147. doi: 10.1007/s004120050422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hunt P, LeMaire R, Embury P, Sheean L, Mroz K. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:2007–2012. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.11.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.