Abstract

Rationale

Both nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) and nuclear factor κB (NFκB) are Rel homology domain (RHD)-containing transcription factors whose independent activities are critically involved in regulating cardiac hypertrophy and failure.

Objective

To determine the potential functional interaction between NFAT and NFκB signaling pathways in cardiomyocytes and its role in cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling.

Methods and Results

Here we identified a novel transcriptional regulatory mechanism whereby NFκB and NFAT directly interact and synergistically promote transcriptional activation in cardiomyocytes. We show that the p65 subunit of NFκB co-immunoprecipitates with NFAT in cardiomyocytes, and this interaction maps to the RHD within p65. Overexpression of the p65-RHD disrupts the association between endogenous p65 and NFATc1, leading to reduced transcriptional activity. Overexpression of IκB kinase β (IKKβ) or p65-RHD causes nuclear translocation of NFATc1, and expression of a constitutively nuclear NFATc1-SA mutant similarly facilitated p65 nuclear translocation. Combined overexpression of p65 and NFATc1 promotes synergistic activation of NFAT transcriptional activity in cardiomyocytes while inhibition of NFκB with IκBαM or dominant negative IKKβ reduces NFAT activity. Importantly, agonist-induced NFAT activation is reduced in p65 null mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) compared to wild-type MEFs. In vivo, cardiac-specific deletion of p65 using a Cre-loxP system causes a ~ 50% reduction in NFAT activity in luciferase reporter mice. Moreover, ablation of p65 in the mouse heart decreases the hypertrophic response following pressure overload stimulation, reduces the degree of pathological remodeling, and preserves contractile function.

Conclusions

Our results suggest a direct interaction between NFAT and NFκB that effectively integrates two disparate signaling pathways in promoting cardiac hypertrophy and ventricular remodeling.

Keywords: hypertrophy, signaling, cardiomyocyte, NFAT, NFκB

Introduction

Cardiac hypertrophy is typically characterized by enlargement of the heart and an increase in myocyte cell volume that occurs in response to hemodynamic stress, acute myocardial injury, infection, or mutations in genes encoding sarcomeric proteins.1 Pathological hypertrophy of the myocardium temporarily preserves pump function, although prolongation of this state is a leading predictor for the development of arrhythmias and sudden death, as well as dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure.2 Neural, humoral, and intrinsic hypertrophic stimuli directly activate membrane bound receptors that in turn activate nodal intracellular signal transduction pathways such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade, calcineurin-NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T cells), insulin-like growth factor-I-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt/protein kinase B, and many others.3 These intracellular signaling cascades then modulate transcriptional regulatory proteins, altering gene expression to facilitate the growth of the heart. For example, transcription factors such as NFAT, myocyte enhancer factor-2 (MEF-2), and GATA4/6 are directly activated by cytoplasmic signaling effectors, which in turn mediate hypertrophic gene expression in cardiomyocytes.3,4 Similarly, the transcription factor NFκB has been implicated as a key regulator of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy both in vitro and in vivo.5 However, the integration amongst these transcriptional effector pathways in the regulation of hypertrophic programming has not been explored in the heart.

The NFκB/Rel family of transcription factors participates in the regulation of disparate cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, immune responses, cell growth, cardiac hypertrophy, and apoptosis.6,7 The Rel family proteins include p65 (RelA), p105/p50, p100/p52, RelB, c-Rel and the viral oncoprotein v-Rel. All Rel family members are conserved throughout evolution and share a Rel homology domain (RHD) at their N terminus that mediates DNA binding and protein-protein interaction between family members. These proteins associate as homo- or heterodimers to form transcriptional regulatory complexes. In unstimulated cells, NFκB binds to cytosolic inhibitory proteins IκBs, mediating cytoplasmic retention. Upon various types of stimulation, IκBs are phosphorylated by IκB kinase (IKK) causing their degradation and subsequent release of NFκB for nuclear translocation.8,9 The IKK complex is composed of 2 catalytic subunits (IKKα and IKKβ) and a regulatory subunit (IKKγ or NEMO). Recent data also suggests that NFκB can shuttle into the nucleus in nonstimulated cells, although the physiological significance of this finding is unknown.5 Post-translational modifications (e.g., phosphorylation and acetylation) and physical interaction with coactivators and corepressors have been identified as additional regulatory mechanisms.10

NFAT transcription factors are also part of the RHD family, where they bear structural similarity to NFκB and even bind related or overlapping DNA sequence elements.6 The NFAT family of transcription factors consists of five family members (NFATc1, NFATc2, NFATc3, NFATc4 and NFAT5 [TonEBP]). NFAT transcription factors are normally hyperphosphorylated and sequestered in the cytoplasm, but rapidly translocate to the nucleus after calcineurin-mediated dephosphorylation.11 Genetic and pharmacological studies have shown that the calcineurin-NFAT pathway is both sufficient and necessary for the cardiac hypertrophic response in a number of rodent models.12,13 Unlike canonical Rel-containing factors, which often homodimerize on target promoters, NFAT factors share an imperfect RHD that is only capable of weak DNA binding in the monomeric or dimeric state. In order to strengthen NFAT-DNA interactions, these factors prefer to interact with other transcription factors such as AP-1 (c-Jun/c-Fos), GATA-4, and MEF-2.14 Here we determined that NFAT and NFκB family members could interact and assemble “higher order” transcriptional complexes that synergistically activate hypertrophic gene expression in the heart.

Materials and Methods

Animal models and procedures

The generation of RelA (p65) loxP-targeted (fl) mice, in which exons 7 and 10 were flanked by loxP sites, was previously described.15 Mice harboring the p65fl/fl alleles were crossed with mice expressing Cre recombinase under control of the endogenous Nkx2.5 locus.16 The NFAT-luciferase reporter transgenic mouse as described previously,17 and was crossed with a p65fl/flNkx2.5-Cre mouse. All experiments involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and University of Washington.

Eight week-old mice were subjected to transverse aortic constriction (TAC) under isoflurane anesthesia as previously described.18 Pressure gradients (mm Hg) were calculated from the peak blood velocity (Vmax) (m/s) (PG = 4 × Vmax2) measured by Doppler across the aortic constriction, which was equivalent in all groups of TAC stimulated mice. All mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane by inhalation. Echocardiography was performed in M-mode using a Hewlett Packard SONOS 5500 instrument equipped with a 15 MHz transducer as described previously.19

Luciferase reporter assays in mouse hearts

In brief, hearts were removed from NFAT-luciferase transgenic mice, some of which were crossed into the p65fl/flNkx2.5-Cre background. Hearts were homogenized in 1 ml luciferase assay buffer (100 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.8, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, and 1 mM DTT). Homogenates were centrifuged at 3,000 g for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatants assayed for luciferase activity as described previously.17

Cell culture, adenoviral infection, and immunocytochemistry

Primary neonatal rat cardiomyocytes were prepared from hearts of 1- to 2-day-old Sprague-Dawley rat pups as previously described.20 After separation from fibroblasts, enriched cardiomyocytes were plated on 1% gelatin-coated 12-well plates for luciferase assays or on 6-cm-diameter dishes for all other experiments. Cells were grown in M199 medium containing 100 U of penicillin-streptomycin/ml and 2 mM L-glutamine without serum for 24 h before infection. p65+/+ and p65−/− MEFs were kindly provided by David Baltimore (California Institute of Technology). Adenoviral infections were performed as previously described at a multiplicity of infection of 10 to 50 plaque forming units per ml.21 Cultures were harvested 24 h after infection, and luciferase assays were preformed as described previously.21 Adβgal, AdΔCnA, Adcain, AdNFAT-luciferase reporter, AdNFATc1-GFP (green fluorescent protein), and AdNFATc3-GFP have been previously described.17,22–24 AdNFκB-luciferase reporter was obtained from Vector Biolabs (Philadelphia, PA). Ad-p65 and Ad-p65-RHD-Myc were a gift of Josef Anrather and Hans Winkler (Harvard University). Adenoviral infections were performed as described previously at a multiplicity of infection of 10–100 plaque forming units per ml.21

Cardiomyocytes were prepared for immunocytochemistry as described previously.24 Immunocytochemistry was performed using anti-p65 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), followed by ALEXA Fluor 568 anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Molecular probes). Cells infected with AdNFATc1-GFP or AdNFATc1-SA-GFP were directly visualized by fluorescent microscopy for GFP.

Western blotting and gel shift assays

Protein extraction from mouse heart or cultured cardiomyocytes and subsequent Western blotting followed by enhanced chemiluminescence detection were performed as previously described.17,18 Anti-Myc and anti-GFP antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Biotechnology (Beverly, MA). Anti-NFATc1, anti-p65, anti-p105/p50, and anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA).

Gel shift assays were performed as previously described.12,25 Briefly, 20 µg nuclear extracts from neonatal cardiomyocytes were incubated in gel shift buffer (12 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 4 mM Tris, pH 7.9, 50 mM KCl, 12% glycerol, 1.2 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 mM PMSF, 2 µg/ml aprotinin, 2 µg/ml leupeptin, 0.7 µg/ml pepstatin) with 0.5 µg poly (dI-dC) and 32P-labeled NFAT or NFκB consensus DNA sequences for 20 min at room temperature. For supershift reactions, 1 µl of anti-NFATc1 or -p65 antibody was added after 20 min of binding reaction. DNA complexes were separated on a 5% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in Tris-borate EDTA buffer.

Immunoprecipitation

Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes were infected with or without specific adenoviruses for 24 h. Cells were lysed at 4°C in buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100) containing protease inhibitors (1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 µg/ml leupeptin, 1 µg/ml pepstatin, and 1 µg/ml aprotinin). Immunoprecipitation was performed as described previously.21 Whole cell lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 10 min and then incubated with the indicated antibodies and protein A-sepharose beads overnight at 4°C. The beads were washed extensively with binding buffer, and the proteins were resolved on an 8–12% SDS-PAGE for subsequent Western blotting.

Statistics

All results are presented as means ± SEM. Paired data were evaluated by Student's t test. A one-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni's post hoc test or repeated-measures ANOVA was used for multiple comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Crosstalk between NFAT and NFκB in cardiomyocytes

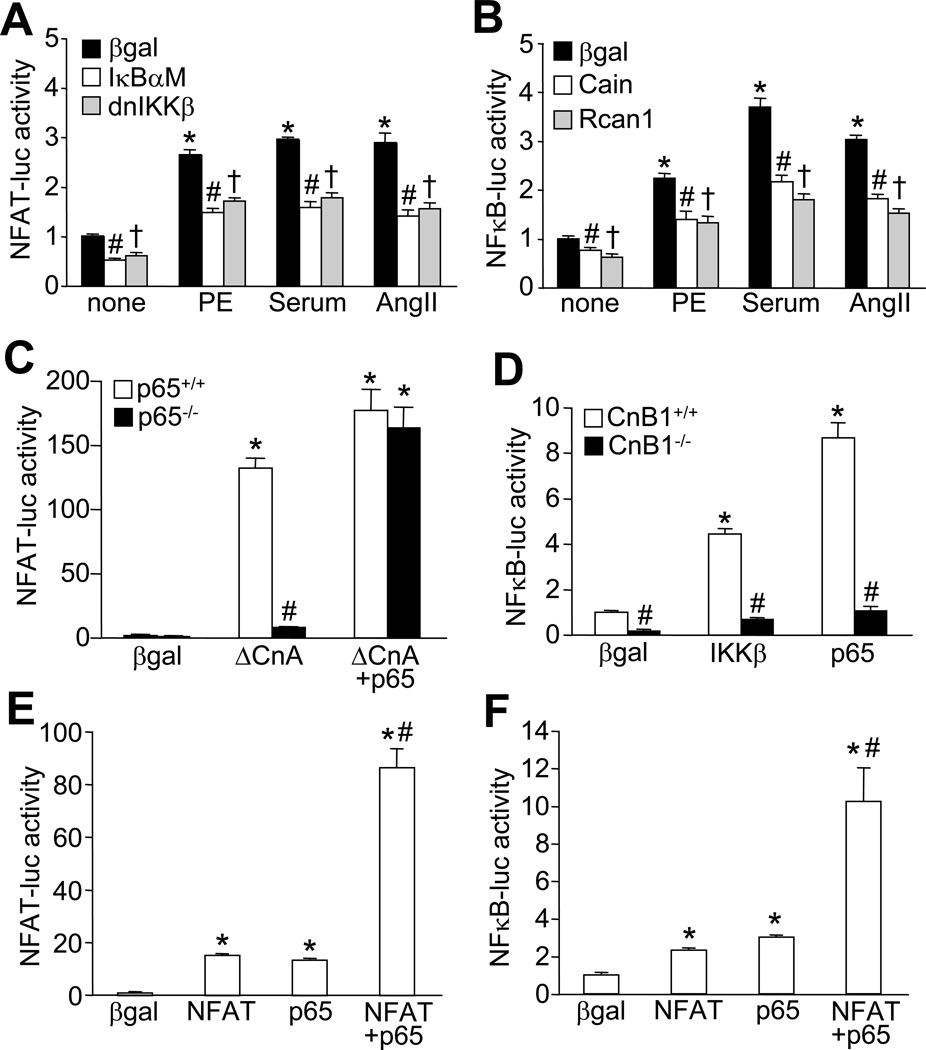

Both calcineurin-NFAT and IKK-NFκB signaling pathways have been implicated as critical regulators of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy.12,26 Here we tested the hypothesis that these two previously deemed independent signaling pathways may actually crosstalk with one another. We first examined if NFκB can influence NFAT transcriptional activity in cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes infected with adenoviruses encoding an NFAT-dependent luciferase reporter cassette. Indeed, NFAT luciferase activity was stimulated by the hypertrophic agonists phenylephrine, serum, and angiotensin II, but this activation was markedly reduced by inhibition of NFκB signaling with the NFκB super-suppressor IκBαM, or dominant negative IKKβ (Figure 1A). Similarly, inhibition of NFAT signaling with Cain or Rcan1 diminished hypertrophic agonists-induced NFκB luciferase activity (Figure 1B). Similar reciprocal regulatory effects between NFAT and NFκB were observed in cardiomyocytes treated with tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), a cytokine known to activate NFκB signaling (Online Figure IA and IB). Activated calcineurin (ΔCnA)-induced NFAT activity was also significantly reduced in NFκB-p65 null MEFs compared to wild-type MEFs, while adenoviral-mediated expression of p65 restored NFAT luciferase activity in p65 null MEFs (Figure 1C). Conversely, NFκB luciferase activity induced by adenoviral overexpression of IKKβ or p65 was also largely blocked in calcineurin-deficient MEFs (lacking CnB1 protein). In addition, calcineurin-deficient MEFs showed lower baseline NFκB activity compared with wild-type MEFs, suggesting that calcineurin regulates NFκB equilibrium even without stimulation (Figure 1D). Inhibition of NFκB signaling with IκBαM or dnIKKβ also partially blocked ΔCnA-induced NFAT luciferase activity, while inhibition of NFAT signaling with Cain diminished p65 or IKKβ-induced NFκB luciferase activity in cardiomyocytes (Online Figure IC and ID). Consistent with these observations, overexpression of NFATc1 or p65 each cross-stimulated NFAT- and NFκB luciferase activity in cardiomyocytes, whereas co-expression of NFAT with p65 synergistically activated both NFAT and NFκB reporter activity (Figure 1E, F). To rule out the involvement of autocrine factors in the observed effects, cardiomyocytes were treated with cultured media collected from cells infected with adenoviruese encoding NFAT, p65, or both, or with IKKb and other inhibitory viruses for NFAT or NFκB signaling (Online Fig IE, IF, and IG). No significant changes in NFAT- or NFκB- luciferase activity was detected under these conditions, thus excluding a role for secreted autocine factors in potentiating NFAT and NFκB transcriptional activation.

Figure 1. Interdependence of NFAT and NFκB for transcriptional activation.

A, NFAT-luciferase activity in neonatal cardiomyocytes infected with recombinant adenoviruses expressing NFAT-luciferase reporter along with β-gal (control), IκBαM, or dnIKKβ and stimulated with phenylephrine (PE, 50 µM), 1% FBS (serum), or angiotensin II (AngII, 100 nM). *P < 0.01 versus none; #,†P < 0.05 versus β-gal for each stimulant. B, NFκB-luciferase activity in neonatal cardiomyocytes infected with recombinant adenoviruses expressing NFκB-luciferase reporter along with β-gal (control), Cain, or Rcan1 and stimulated with PE, FBS, or AngII. *P < 0.01 versus none; #, †P < 0.05 versus β-gal for each stimulant. C, NFAT-luciferase activity from p65+/+ or p65−/− MEFs infected with adenoviruses expressing the NFAT-luciferase reporter with the other indicated proteins. *P < 0.01 versus β-gal; #P < 0.05 versus p65+/+ ΔCnA. D, NFκB-luciferase from CnB1+/+ or CnB1−/− MEFs infected with adenoviruses encoding NFκB-luciferase reporter and other indicated proteins. *P < 0.01 versus β-gal; #P < 0.05 versus corresponding CnB1+/+. E, NFAT-luciferase activity in neonatal cardiomyocytes infected with adenoviruses encoding NFAT-luciferase reporter and other indicated proteins. *P < 0.05 versus β-gal; #P < 0.05 versus NFAT or p65 only. F, NFκB-luciferase activity in neonatal cardiomyocytes infected with adenoviruses encoding the NFκB-luciferase reporter with the other indicated proteins. *P < 0.05 versus β-gal; #P < 0.05 versus NFAT or p65 only.

Physical interaction between NFAT and NFκB

While a direct interaction between NFκB and NFAT transcription factors has not been demonstrated in cardiomyocytes, a physical association between NFATc1 and c-Rel was previously reported in lymphocytes.27 Hence, we examined if NFAT interacts with p65-NFκB in cardiomyocytes by immunoprecipitation. The results showed that NFATc1 immunoprecipitated with a p65 antibody but not with a non-specific IgG antibody (Figure 2A). Conversely, immunoprecipitation of NFATc1 with a GFP antibody resulted in the isolation of p65, suggesting an association between these two transcription factors in cardiomyocytes (Figure 2B). Immunoprecipitation experiments were also performed in neonatal cardiomyocytes stimulated with phenylephrine, TNFα, or vehicle control. While the interaction between NFAT-p65 was still observed with these agonists, no changes in intensity were observed (Online Figure II). Since both NFAT and NFκB contain a Rel homology domain (RHD), which is important for protein-protein interaction and dimerization, cardiomyocytes infected with an adenovirus encoding p65-RHD showed co-immunoprecipitation with NFATc1 (Figure 2C). Importantly, overexpression of p65-RHD disrupted the association between NFATc1 and endogenous p65 (Figure 2C, middle panel). Overexpression of p65-RHD also partially inhibited calcineurin-induced NFAT luciferase activity, suggesting that p65-RHD acts as dominant negative for endogenous p65 because it lacks a transcriptional activation domain (Figure 2E). Full length p65 localized primarily in the cytoplasm of unstimulated neonatal cardiomyocytes, similar to NFATc1-GFP (Figure 2D). However, p65-RHD exclusively localized to the nucleus in cultured cardiomyocytes given its lack of N and C-terminal regulatory domains, which remarkably induced constitutive nuclear localization of NFATc1-GFP, presumably due to the strong interaction between these proteins (Figure 2D). Thus p65-RHD is sufficient to retain NFATc1 in the nucleus through their interaction.

Figure 2. Physical interaction between NFAT and p65 in cardiomyocytes.

A, Western blots for NFATc1 and p65 following immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-p65 antibody or pre-immune IgG from neonatal cardiomyocytes infected with AdNFATc1-GFP. B, Western blots for NFATc1 and p65 following immunoprecipitation with an anti-GFP antibody or pre-immune IgG from neonatal cardiomyocytes infected with AdNFATc1-GFP. C, Western blots for Myc, p65, and GFP following immunoprecipitation with an anti-GFP antibody or pre-immune IgG from neonatal cardiomyocytes infected with p65-RHD-Myc and NFATc1-GFP adenoviruses. D, Immuno-staining for p65 or Myc (p65-RHD) in red and GFP for NFAT in neonatal cardiomyocytes infected with p65, p65-RHD-Myc and NFATc1-GFP adenoviruses. E, NFAT-luciferase activity in neonatal cardiomyocytes infected with an adenovirus encoding NFAT-luciferase reporter along with the other indicated adenoviruses. Results were summated from 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05 versus β-gal; #P < 0.05 versus ΔCnA only. F, Gel shift for NFAT or NFκB DNA binding activity in cardiomyocyte nuclear extracts incubated with anti-NFAT, anti-p65, or pre-immune IgG. Arrows indicate specific NFAT or NFκB binding activity. n.s. = non-specific.

A gel shift assay was performed with cardiomyocyte nuclear extracts to determine if NFAT and p65 can form transcriptional complexes. The data show that NFAT DNA-binding activity from this nuclear extract is shifted with an anti-NFAT antibody, as expected, while a p65 antibody partially disrupts the NFAT binding complex (Figure 2F). Conversely, NFκB DNA-binding activity is completely disrupted with the anti-p65 antibody, as expected, while the anti-NFAT antibody disrupted and supershifted of the NFκB DNA-binding activity (Figure 2F). These results indicate that NFκB and NFAT are complexed together in cardiomyocyte nuclear extract at baseline.

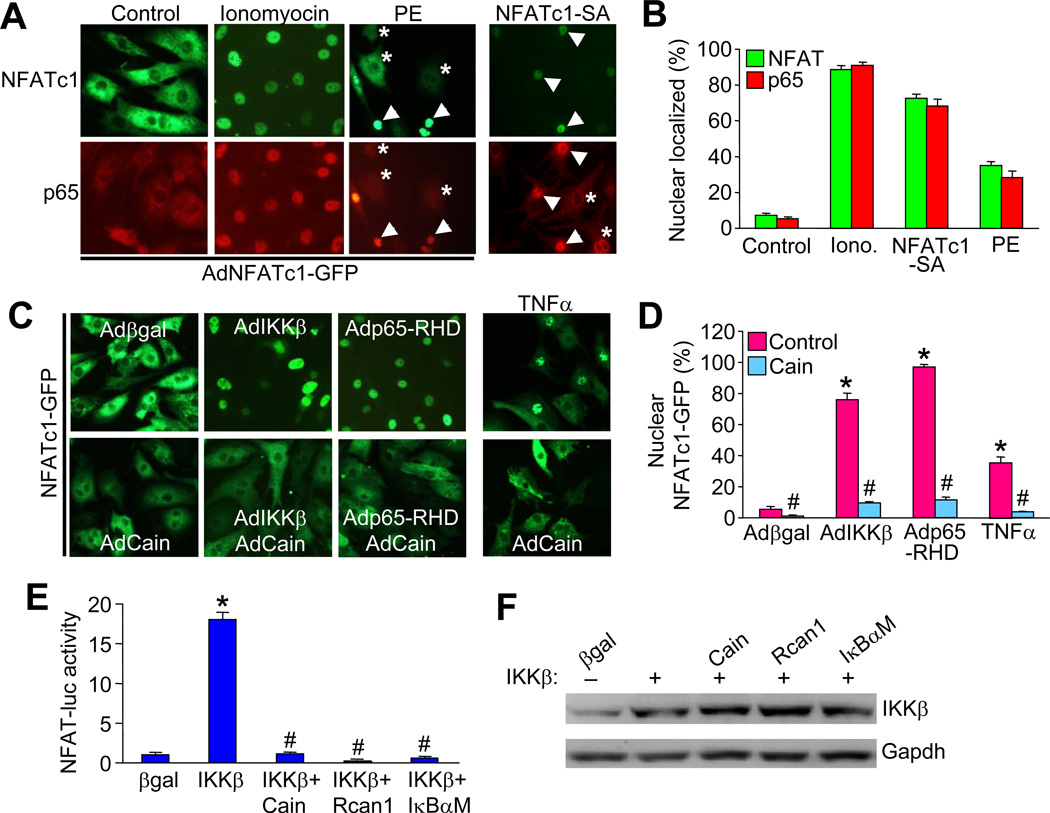

NFAT and NFκB regulate one another’s subcellular shuttling

NFAT activity is typically regulated by calcineurin-mediated dephosphorylation within the cytoplasm, resulting in nuclear translocation and the activation of NFAT responsive genes. Similarly, nuclear translocation of NFκB is required for NFκB transcriptional activation. Here we further investigated if NFAT and NFκB could potentially regulate one another’s subcellular shuttling through their ability to complex together. Cardiomyocytes were infected with an adenovirus encoding NFATc1-GFP or the NFATc1 serine/alanine mutant (NFATc1-SA) that is constitutively nuclear (also fused to GFP). In control cells, both NFATc1 and p65 are primarily localized in the cytoplasm (Figure 3A, B, and data not shown). Ionomycin, which activates calcineurin, triggered a robust translocation of NFATc1 to the nucleus (Figure 3A, B). Remarkably, near complete nuclear co-localization of p65 was induced by ionomycin, which is not known to activate NFκB directly, suggesting it may be due to NFAT translocation (Figure 3A, B). In addition, the GPCR agonist phenylephrine induced both NFATc1 and p65 nuclear translocation in cardiomyocytes (Figure 3A, B). Importantly, cells infected with a constitutively nuclear NFAT mutant, NFATc1-SA, also showed complete translocation of NFκB, while uninfected cells in the same dish showed cytoplasmic NFκB (Figure 3A, B; arrowheads versus asterisks). These data suggest that NFAT nuclear shuttling is sufficient to produce NFκB nuclear translocation in cardiomyocytes.

Figure 3. Co-localization of NFAT and NFκB in cardiomyocytes.

A, Immunofluorescent images from cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes infected with AdNFATc1-GFP (green) and stimulated with 1 µM ionomycin, 50 µM phenylephrine, or vehicle control, or infected with an NFATc1-SA-GFP adenovirus. Cells were also immune-stained for endogenous p65 (red). Arrowheads indicate nuclear localization while asterisks show cytoplasmic localization. B, Quantification of nuclear localized NFATc1 and p65 in cells treated as indicated in A. C, Immunofluorescent images from cultured neonatal cardiomyocytes infected with AdNFATc1-GFP along with the other indicated adenoviruses or stimulated with 20 ng/ml TNFα. D, Quantification of nuclear localized NFATc1 in cells treated as indicated in C. E, NFAT-luciferase activity in neonatal cardiomyocytes infected with the AdNFAT-luciferase reporter and the other indicated adenoviruses. *P < 0.05 versus β-gal; #P < 0.05 versus IKKβ only. Results were summated from 3 independent experiments. F, Control western blot to show equal levels of IKKβ overexpression for the experiment shown in E.

We also investigated the reciprocal relationship by examining whether activation of NFκB could influence NFAT subcellular localization. Coinfection of AdNFATc1-GFP with an adenovirus expressing IKKβ resulted in robust NFATc1 nuclear translocation (Figure 3C, D). Similarly, cells overexpressing the constitutively nuclear p65-RHD truncation showed complete translocation of NFATc1-GFP (Figure 3C, D). Moreover, TNFα, a known activator of NFκB, also induced NFATc1 nuclear translocation in cardiomyocytes. Interestingly, overexpression of the calcineurin inhibitory protein Cain, blocked NFATc1 nuclear translocation induced by IKKβ or p65-RHD, suggesting that basal calcineurin activity is still required for IKKβ or p65-RHD-induced NFAT nuclear shuttling (Figure 3C, D). Consistent with these observations, IKKβ-induced NFAT-luciferase activity was blocked by inhibition of calcineurin with Cain or Rcan1 (Figure 3E, F). Importantly, inhibition of NFκB with the IκBαM mutant abrogated IKKβ-induced NFAT activity, suggesting an NFκB-dependent action for IKKβ in regulating NFAT.

Ablation of p65 diminishes NFAT transcriptional activity in the heart

p65 is one of the major NFκB subunits expressed in the myocardium. Here we determined that p65 protein expression is increased in pressure overload-induced hypertrophic hearts in the mouse, with no significant change in p50 expression, another prominent NFκB subunit (Figure 4A). These results suggested that p65 might be a more critical regulator of the hypertrophic response, although its function in vivo in accord with NFAT has not been investigated. Standard RelA (p65) gene-targeted mice perish during early embryonic development precluding an analysis of p65’s function in the adult heart.28 To address this limitation here, we used a Cre-loxP-dependent conditional gene targeting approach to permit specific inactivation of p65 in the heart. Mice homozygous for the p65-loxP-targeted allele (fl/fl) were crossed with Nkx2.5-Cre “knock-in” mice. Western blotting of protein extracts from hearts of 2 month-old p65fl/flNkx2.5-Cre mice showed > 80% reduction in p65 protein, which did not change endogenous NFAT protein levels (Figure 4B). p65fl/flNkx2.5-Cre mice were generated at predicted Mendelian ratios and were overtly normal well into adulthood.

Figure 4. NFAT transcriptional activity is reduced in p65 deleted hearts in vivo.

A, Western blots for p65, p50, and GAPDH in heart extracts from sham- and TAC-operated wild-type mice. B, Western blot for p65, GAPDH, and NFAT isoforms in control (p65fl/fl) and p65-deleted (p65fl/flNkx2.5-Cre) hearts. C, Measurement of NFAT luciferase activity from p65fl/fl and p65fl/flNkx2.5-Cre mice containing the NFAT luciferase reporter transgene after 2 weeks of TAC or a sham operation. *P < 0.05 versus sham; #P < 0.05 versus corresponding p65fl/fl. Number of mice analyzed is shown in the bars.

To determine the effect of p65 deletion on NFAT transcriptional activity in the heart in vivo, we crossed p65fl/flNkx2.5-cre and NFAT-luciferase reporter mice together.17 As shown in Figure 4C, deletion of p65 significantly reduced NFAT luciferase activity by ~50% compared to wild-type control mice at baseline (sham groups). Remarkably, pressure overload-induced NFAT-luciferase activity following TAC stimulation was also significantly diminished in p65 deleted hearts (Figure 4C), consistent with our observation that inhibition of NFκB can antagonize calcineurin-NFAT signaling in cardiomyocytes (Figure 1A).

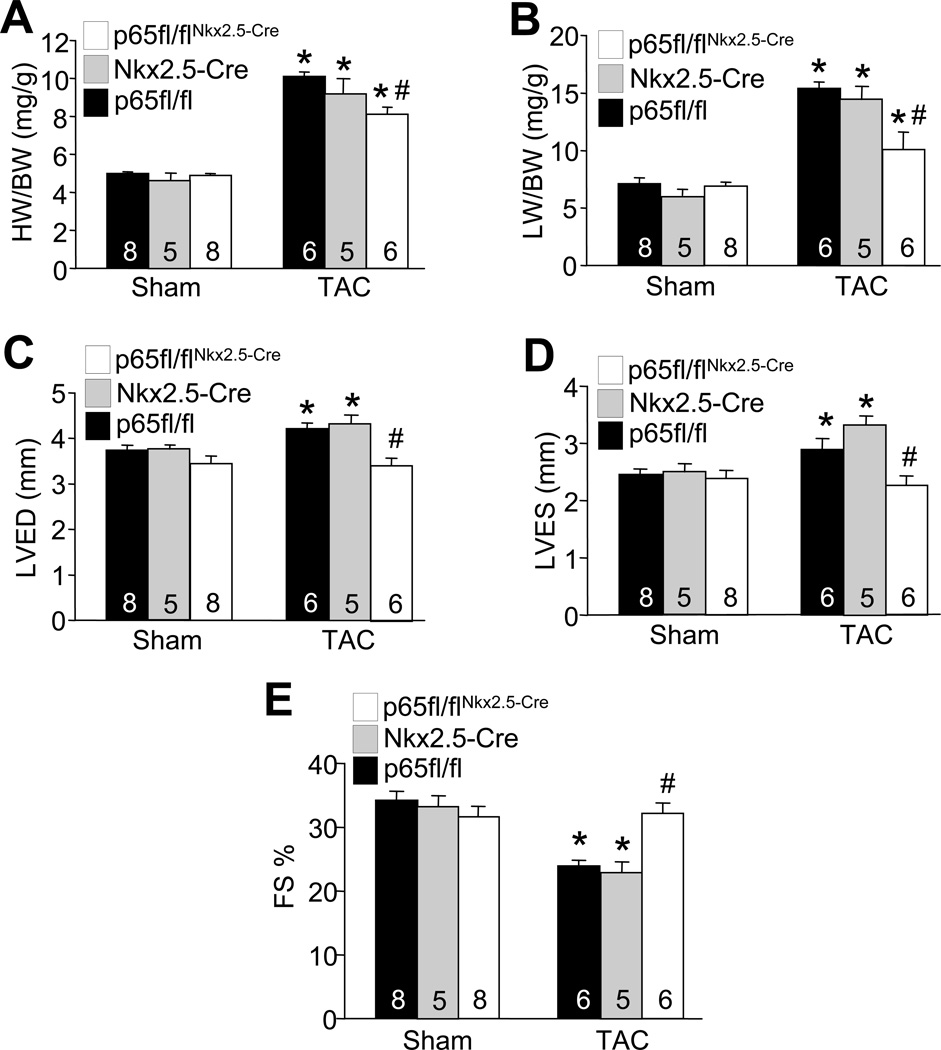

Ablation of p65 reduced pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy

Calcineurin-NFAT signaling has been implicated as a central regulator of pathological cardiac hypertrophy,12 and deletion of NFATc3 or c2 each reduced the hypertrophic response in gene-targeted mice.29,30 Based on our observations that ablation of p65 antagonized calcineurin-NFAT signaling, we hypothesized that p65 is also required for efficient cardiac hypertrophy in response to pressure overload stimulation in vivo. Indeed, TAC stimulation for 4 weeks in p65fl/flNkx2.5-Cre mice showed reduced cardiac hypertrophy (whole organ and cellular) and fibrosis compared with p65fl/fl and Nkx2.5-Cre control mice (Figure 5A and Online Figure IIIA–D). Measurement of lung weight normalized to body weight also showed reduced pulmonary congestion in p65fl/flNkx2.5-Cre mice after 4 weeks of TAC compared with controls (Figure 5B). Echocardiographic assessment of ventricular chamber dimensions and fractional shortening also showed preserved cardiac function and less dilation after TAC in p65fl/flNkx2.5-Cre mice compared with controls (Figures 5C,D,E). Taken together, these results indicate that p65 ablation reduces pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and ventricular remodeling, consistent with less hypertrophy and remodeling observed previously in NFATc3 or c2 deleted mice, supporting the hypothesis that these 2 pathways functionally intersect in the heart.

Figure 5. p65 is required for pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy.

A and B, Heart weight to body weight ratio (HW/BW) and lung weight to body weight ratio (LW/BW) in the indicated genotypes 4 weeks after TAC or sham operation. *P< 0.05 vs. p65fl/fl sham or p65fl/flNkx2.5-Cre sham. #P < 0.05 versus p65fl/fl or Nkx2.5-Cre TAC. C, D, and E, Left ventricular end diastolic dimension (LVED), left ventricular end systolic dimension (LVES), and cardiac fractional shortening percentage (FS) from sham- and TAC- operated mice after 4 weeks of pressure overload, measured by M-mode echocardiography. *P< 0.05 vs. p65fl/fl sham or p65fl/flNkx2.5-Cre sham. #P < 0.05 versus p65fl/fl or Nkx2.5-Cre TAC. Number of mice analyzed is shown in the bars.

Discussion

We demonstrated for the first time the interdependence between NFAT and NFκB signaling in mediating hypertrophic gene expression in the heart. Indeed, hypertrophic agonist-induced NFAT transcriptional activity was partially blocked by inhibition of NFκB with the IκB super-suppressor, dominant negative IKKβ, or genetic deletion of p65. This result suggests that full transcriptional activation of NFAT requires intact NFκB signaling and p65 transcriptional activity. Antithetically, genetic inhibition of calcineurin-NFAT showed compromised NFκB transcriptional activation in cardiac myocytes. Consistent with these observations, the potent NFκB inhibitor, PDTC, promoted rapid nuclear export of NFAT from the nucleus of stimulated cells leading to reduced NFAT transcriptional activity, although the mechanism underlying this effect was not identified.31

Mechanistically, we showed that NFAT directly interacts with p65 to form a complex that promotes transcriptional synergy. Cooperative interactions between NFκB and other transcription factors have been suggested in the regulation of gene expression. For instance, interactions between NFκB and the signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) factors are the basis for synergistic transcriptional activation of genes after TNFα and interferon-γ co-stimulation.32 Other transcription factors that interact with NFκB include AP-1, CREB, NF-IL, myc, and IRF-1.6 Unlike canonical Rel-containing factors, which often homodimerize on target promoters, NFAT factors share an imperfect Rel homology domain that is only capable of weak DNA binding in the monomeric or dimeric state. In order to strengthen DNA interaction on target promoters, NFAT factors prefer to interact with other nuclear transcription factors such as AP-1, GATA-4, MEF-2, and now p65-NFκB.14

Under basal conditions, NFAT transcription factors are excluded from the nucleus by phosphorylation of the N-terminal regulatory domain. NFAT transcription factors are prototypical effectors of calcineurin signaling.33 Calcineurin directly interacts with NFAT through a conserved docking motif, and upon activation by calcium/calmodulin, calcineurin dephosphorylates NFAT unmasking a nuclear localization signal. NFAT subsequently enters the nucleus and activates gene transcription.33 Our data indicate that intracellular shuttling of NFAT is regulated by NFκB signaling, in part, by direct binding of the transcription factors themselves. Thus, direct interaction between NFAT and NFκB provides a new regulatory mechanism for NFAT transcriptional activation by affecting the nuclear import and export equilibrium of each factor. NFκB nuclear translocation induced by IKKβ or p65-RHD enhances NFAT nuclear localization. However, basal calcineurin activity is required for IKKβ or p65-RHD-induced NFAT nuclear retention since this effect was blocked by the calcineurin inhibitory protein Cain. Thus, some level of calcineurin-mediated basal dephosphorylation of NFAT is necessary for NFAT to periodically transit through the nucleus to have the opportunity to bind p65-NFκB and be retained.

NFκB plays important roles in cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling. For example, in vitro studies have shown that NFκB is required for hypertrophic growth of cardiomyocytes in response to G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) agonists such as phenylephrine, endothelin-1 and angiotensin II.26,34,35 In addition, in vivo studies using different animal models of NFκB inactivation by IκBαM mutant overexpression, p65 silencing, or p50 deletion also showed reduced cardiac hypertrophy in response to aortic banding,36 chronic infusion of GPCR agonists,37,38 and transgenic overexpression of myotrophin.39,40 However, Inhibition of NFκB signaling in cardiac specific IKKβ or NEMO knockout mice showed enhanced hypertrophy and pathological remodeling.41,42 Thus manipulation of different components of the NFκB signaling pathway may have distinct functional consequences in the heart.

Intriguingly, we observed upregulation of p65 but not p50 in the heart following pressure overload. In addition, we were not able to detect association of p50 with NFAT by immunoprecipitation in cardiomyocytes (data not shown). These results suggest that different NFκB subunits may have distinct roles in signal transduction and cellular function. Indeed, p65 nuclear translocation and cytokine expression were observed in p50 deficient cardiomyocytes upon stimulation, suggesting that p65 functions independent of p50.43 In addition, embryonic fibroblasts from p65 null mice were deficient in activating certain TNFα-inducible genes with NFκB binding sites,44 while p50 null cells showed normal activation.45

Our results also provide new insights into how NFκB induces cardiac hypertrophy and fetal gene expression. No NFκB binding sites have been identified in the promoter regions of adult or fetal cardiac genes associated with cardiac hypertrophy. Here we showed that NFκB affected cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling through a physical interaction with the well-defined hypertrophic transcription factor NFAT, for which many direct promoter interaction sites have been identified in hypertrophic genes.12,30 Indeed, overexpression of a constitutively activated NFAT mutant protein resulted in cardiac hypertrophy in transgenic mice, suggesting that NFAT activation is sufficient to promote the hypertrophic response of the heart.12 In addition, genetic inhibition of NFAT isoforms attenuated the hypertrophic response to hypertrophic agonists and pressure-overload.29,30,46

Blocking of NFκB activity could represent a novel approach to attenuate cardiac hypertrophy and adverse remodeling. We demonstrated that p65 ablation reduced pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy with preserved cardiac function, possibly through diminished NFAT signaling. In addition, cardiac deletion of p65 also showed reduced cardiac hypertrophy and ventricular remodeling with improved contractile function in response to myocardial infarction (data not shown), and similar effects were observed in a transgenic mouse expressing IκB super-suppressor.47 Great efforts have been made for the development of highly specific NFκB inhibitors for treating autoimmune diseases and different types of cancer, some of which are being evaluated in phase II clinical trials. Although the calcineurin inhibitors cyclosporine A and FK506 dramatically attenuates cardiac hypertrophy in most animal models,48 severe side effects preclude their use for heart disease in humans.49–51 Thus, targeting NFκB may represent a valid alternative therapeutic strategy in treating hypertrophy or heart failure, which secondarily would reduce the effectiveness of NFAT activity in the heart.

Novelty and Significance.

What is known

Calcineurin-NFAT signaling is a central regulator of pathological cardiac hypertrophy.

NFκB is a key regulator of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy both in vitro and in vivo.

What new information does this article contribute?

We provide the first evidence showing a direct interaction between NFAT and NFκB that effectively integrates two disparate hypertrophic signaling pathways in the heart.

We identified a novel transcriptional regulatory mechanism whereby NFκB and NFAT directly interact and synergistically promote transcriptional activation of one another in cardiomyocytes.

Targeting NFκB may represent a novel therapeutic strategy in treating cardiac hypertrophy or heart failure by secondarily diminishing NFAT signaling in the heart.

This study was designed to determine the potential functional interaction between NFAT and NFκB signaling pathways in cardiomyocytes and its role in cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling. Our findings provide new mechanistic insight into how NFκB and NFAT synergistically induce cardiac hypertrophy and pathological remodeling. We demonstrate that NFκB-p65 ablation reduced pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy with preserved cardiac function, possibly through diminished NFAT signaling. Therefore, targeting NFκB may represent as a valid alternative therapeutic strategy in treating hypertrophic heart failure, which secondarily would diminish NFAT signaling in the heart.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (J.D.M., Q.L.) and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (J.D.M.).

Non-standard abbreviations

- ΔCnA

activated calcineurin

- fl

loxP-targeted

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- IKK

IκB kinase

- MEFs

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- MEF-2

myocyte enhancer factor-2

- NFAT

nuclear factor of activated T cells

- NFκB

nuclear factor κB

- RHD

Rel homology domain

- TAC

transverse aortic constriction

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor α

Footnotes

Disclosures:

None.

References

- 1.Lorell BH, Carabello BA. Left ventricular hypertrophy: pathogenesis, detection, and prognosis. Circulation. 2000;102:470–479. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lloyd-Jones DM, Larson MG, Leip EP, Beiser A, D'Agostino RB, Kannel WB, Murabito JM, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ, Levy D Framingham Heart Study. Lifetime risk for developing congestive heart failure: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 106:3068–3072. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000039105.49749.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molkentin JD, Dorn GW., 2nd Cytoplasmic signaling pathways that regulate cardiac hypertrophy. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:391–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heineke J, Molkentin JD. Regulation of cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signaling pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:589–600. doi: 10.1038/nrm1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gordon JW, Shaw JA, Kirshenbaum LA. Multiple facets of NF-κB in the heart: to be or not to NF-κB. Circ Res. 2011;108:1122–1132. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones WK, Brown M, Ren X, He S, McGuinness M. NF-kappaB as an integrator of diverse signaling pathways: the heart of myocardial signaling? Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2003;3:229–254. doi: 10.1385/ct:3:3:229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li X, Stark GR. NFkappaB-dependent signaling pathways. Exp Hematol. 2002;30:285–296. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00777-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-[kappa]B activity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:621–563. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-kappaB. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2195–2224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perkins ND. Post-translational modifications regulating the activity and function of the nuclear factor kappa B pathway. Oncogene. 2006;25:6717–6730. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crabtree GR, Olson EN. NFAT signaling: choreographing the social lives of cells. Cell. 2002;109(Suppl):S67–S79. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00699-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molkentin JD, Lu JR, Antos CL, Markham B, Richardson J, Robbins J, Grant SR, Olson EN. A calcineurin-dependent transcriptional pathway for cardiac hypertrophy. Cell. 1998;93:215–228. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81573-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkins BJ, Molkentin JD. Calcineurin and cardiac hypertrophy: where have we been? Where are we going? J Physiol. 2002;541(Pt 1):1–8. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.017129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hogan PG, Chen L, Nardone J, Rao A. Transcriptional regulation by calcium, calcineurin, and NFAT. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2205–2032. doi: 10.1101/gad.1102703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Algül H, Treiber M, Lesina M, Nakhai H, Saur D, Geisler F, Pfeifer A, Paxian S, Schmid RM. Pancreas-specific RelA/p65 truncation increases susceptibility of acini to inflammation associated cell death following cerulein pancreatitis. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1490–1501. doi: 10.1172/JCI29882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moses KA, DeMayo F, Braun RM, Reecy JL, Schwartz RJ. Embryonic expression of an Nkx2–5/Cre gene using ROSA26 reporter mice. Genesis. 2001;31:176–180. doi: 10.1002/gene.10022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkins BJ, Dai YS, Bueno OF, Parsons SA, Xu J, Plank DM, Jones F, Kimball TR, Molkentin JD. Calcineurin/NFAT coupling participates in pathological, but not physiological, cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2004;94:110–118. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000109415.17511.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Q, Sargent MA, York AJ, Molkentin JD. ASK1 regulates cardiomyocyte death but not hypertrophy in transgenic mice. Circ Res. 2009;105:1110–1117. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.200741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oka T, Maillet M, Watt AJ, Schwartz RJ, Aronow BJ, Duncan SA, Molkentin JD. Cardiac specific deletion of Gata4 reveals its requirement for hypertrophy, compensation, and myocyte viability. Circ Res. 2006;98:837–845. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000215985.18538.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Windt LJ, Lim HW, Haq S, Force T, Molkentin JD. Calcineurin promotes protein kinase C and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation in the heart. Cross-talk between cardiac hypertrophic signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:13571–13579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Q, Wilkins BJ, Lee YJ, Ichijo H, Molkentin JD. Direct interaction and reciprocal regulation between ASK1 and calcineurin-NFAT control cardiomyocyte death and growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3785–3797. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.10.3785-3797.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kakita T, Hasegawa K, Iwai-Kanai E, Adachi S, Morimoto T, Wada H, Kawamura T, Yanazume T, Sasayama S. Calcineurin pathway is required for endothelin-1-mediated protection against oxidant stress-induced apoptosis in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2001;88:1239–1246. doi: 10.1161/hh1201.091794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanna B, Bueno OF, Dai YS, Wilkins BJ, Molkentin JD. Direct and indirect interactions between calcineurin-NFAT and MEK1-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 signaling pathways regulate cardiac gene expression and cellular growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:865–878. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.3.865-878.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taigen T, De Windt LJ, Lim HW, Molkentin JD. Targeted inhibition of calcineurin prevents agonist-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1196–1201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang Q, Wiese RJ, Bueno OF, Dai YS, Markham BE, Molkentin JD. The transcription factor GATA4 is activated by extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1- and 2-mediated phosphorylation of serine 105 in cardiomyocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7460–7469. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7460-7469.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Purcell NH, Tang G, Yu C, Mercurio F, DiDonato JA, Lin A. Activation of NF-kappa B is required for hypertrophic growth of primary rat neonatal ventricular cardiomyocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6668–6673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111155798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pham LV, Tamayo AT, Yoshimura LC, Lin-Lee YC, Ford RJ. Constitutive NF-kappaB and NFAT activation in aggressive B-cell lymphomas synergistically activates the CD154 gene and maintains lymphoma cell survival. Blood. 2005;106:3940–3947. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beg AA, Baltimore D. An essential role for NF-kappaB in preventing TNF-alpha-induced cell death. Science. 1996;274:782–784. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilkins BJ, De Windt LJ, Bueno OF, Braz JC, Glascock BJ, Kimball TF, Molkentin JD. Targeted disruption of NFATc3, but not NFATc4, reveals an intrinsic defect in calcineurin-mediated cardiac hypertrophic growth. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:7603–7613. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7603-7613.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bourajjaj M, Armand AS, da Costa Martins PA, Weijts B, van der Nagel R, Heeneman S, Wehrens XH, De Windt LJ. NFATc2 is a necessary mediator of calcineurin-dependent cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:22295–22303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801296200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martínez-Martínez S, Gómez del Arco P, Armesilla AL, Aramburu J, Luo C, Rao A, Redondo JM. Blockade of T-cell activation by dithiocarbamates involves novel mechanisms of inhibition of nuclear factor of activated T cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6437–6447. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohmori Y, Hamilton TA. The interferon-stimulated response element and a kappa B site mediate synergistic induction of murine IP-10 gene transcription by IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha. J Immunol. 1995;154:5235–5244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rao A, Luo C, Hogan PG. Transcription factors of the NFAT family: regulation and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:707–747. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cook SA, Novikov MS, Ahn Y, Matsui T, Rosenzweig A. A20 is dynamically regulated in the heart and inhibits the hypertrophic response. Circulation. 2003;108:664–667. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000086978.95976.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirotani S, Otsu K, Nishida K, Higuchi Y, Morita T, Nakayama H, Yamaguchi O, Mano T, Matsumura Y, Ueno H, Tada M, Hori M. Involvement of nuclear factor-kappaB and apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 in G-protein-coupled receptor agonist-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Circulation. 2002;105:509–515. doi: 10.1161/hc0402.102863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Y, Ha T, Gao X, Kelley J, Williams DL, Browder IW, Kao RL, Li C. NF-kappaB activation is required for the development of cardiac hypertrophy in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1712–H1720. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00124.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawano S, Kubota T, Monden Y, Kawamura N, Tsutsui H, Takeshita A, Sunagawa K. Blockade of NF-kappaB ameliorates myocardial hypertrophy in response to chronic infusion of angiotensin II. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:689–698. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Freund C, Schmidt-Ullrich R, Baurand A, Dunger S, Schneider W, Loser P, El-Jamali A, Dietz R, Scheidereit C, Bergmann MW. Requirement of nuclear factor-kappaB in angiotensin II- and isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy in vivo. Circulation. 2005;111:2319–2325. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000164237.58200.5A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gupta S, Young D, Maitra RK, Gupta A, Popovic ZB, Yong SL, Mahajan A, Wang Q, Sen S. Prevention of cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure by silencing of NF-kappaB. J Mol Biol. 2008;375:637–649. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young D, Popovic ZB, Jones WK, Gupta S. Blockade of NF-kappaB using IkappaB alpha dominant-negative mice ameliorates cardiac hypertrophy in myotrophin-overexpressed transgenic mice. J Mol Biol. 2008;381:559–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.05.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hikoso S, Yamaguchi O, Nakano Y, Takeda T, Omiya S, Mizote I, Taneike M, Oka T, Tamai T, Oyabu J, Uno Y, Matsumura Y, Nishida K, Suzuki K, Kogo M, Hori M, Otsu K. The I{kappa}B kinase {beta}/nuclear factor {kappa}B signaling pathway protects the heart from hemodynamic stress mediated by the regulation of manganese superoxide dismutase expression. Circ Res. 2009;105:70–79. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.193318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kratsios P, Huth M, Temmerman L, Salimova E, Al Banchaabouchi M, Sgoifo A, Manghi M, Suzuki K, Rosenthal N, Mourkioti F. Antioxidant amelioration of dilated cardiomyopathy caused by conditional deletion of NEMO/IKKgamma in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2010;106:133–144. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Timmers L, van Keulen JK, Hoefer IE, Meijs MF, van Middelaar B, den Ouden K, van Echteld CJ, Pasterkamp G, de Kleijn DP. Targeted deletion of nuclear factor kappaB p50 enhances cardiac remodeling and dysfunction following myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2009;104:699–706. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.189746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beg AA, Sha WC, Bronson RT, Ghosh S, Baltimore D. Embryonic lethality and liver degeneration in mice lacking the RelA component of NF-kappa B. Nature. 1995;376:167–170. doi: 10.1038/376167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sha WC, Liou HC, Tuomanen EI, Baltimore D. Targeted disruption of the p50 subunit of NF-kappa B leads to multifocal defects in immune responses. Cell. 1995;80:321–330. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90415-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pu WT, Ma Q, Izumo S. NFAT transcription factors are critical survival factors that inhibit cardiomyocyte apoptosis during phenylephrine stimulation in vitro. Circ Res. 2003;92:725–731. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000069211.82346.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamid T, Guo SZ, Kingery JR, Xiang X, Dawn B, Prabhu SD. Cardiomyocyte NF-κB p65 promotes adverse remodelling, apoptosis, and endoplasmic reticulum stress in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;89:129–138. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Molkentin JD. Calcineurin and beyond: cardiac hypertrophic signaling. Circ Res. 2000;87:731–738. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.9.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang G, Meguro T, Hong C, Asai K, Takagi G, Karoor VL, Sadoshima J, Vatner DE, Bishop SP, Vatner SF. Cyclosporine reduces left ventricular mass with chronic aortic banding in mice, which could be due to apoptosis and fibrosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1505–1514. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oie E, Bjørnerheim R, Clausen OP, Attramadal H. Cyclosporin A inhibits cardiac hypertrophy and enhances cardiac dysfunction during postinfarction failure in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H2115–H2123. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.6.H2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Flechner SM, Kobashigawa J, Klintmalm G. Calcineurin inhibitor-sparing regimens in solid organ transplantation: focus on improving renal function and nephrotoxicity. Clin Transplant. 2008;22:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2007.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.