Abstract

Objective

To systematically review the literature on the implementation of e-health to identify: (i) barriers and facilitators to e-health implementation, and (ii) outstanding gaps in research on the subject.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PSYCINFO and the Cochrane Library were searched for reviews published between 1 January 1995 and 17 March 2009. Studies had to be systematic reviews, narrative reviews, qualitative metasyntheses or meta-ethnographies of e-health implementation. Abstracts and papers were double screened and data were extracted on country of origin; e-health domain; publication date; aims and methods; databases searched; inclusion and exclusion criteria and number of papers included. Data were analysed qualitatively using normalization process theory as an explanatory coding framework.

Findings

Inclusion criteria were met by 37 papers; 20 had been published between 1995 and 2007 and 17 between 2008 and 2009. Methodological quality was poor: 19 papers did not specify the inclusion and exclusion criteria and 13 did not indicate the precise number of articles screened. The use of normalization process theory as a conceptual framework revealed that relatively little attention was paid to: (i) work directed at making sense of e-health systems, specifying their purposes and benefits, establishing their value to users and planning their implementation; (ii) factors promoting or inhibiting engagement and participation; (iii) effects on roles and responsibilities; (iv) risk management, and (v) ways in which implementation processes might be reconfigured by user-produced knowledge.

Conclusion

The published literature focused on organizational issues, neglecting the wider social framework that must be considered when introducing new technologies.

Résumé

Objectif

Analyser de façon systématique la documentation sur l'implémentation de l'e-santé afin d'identifier: (i) les éléments entravant et soutenant l'implémentation de l'e-santé, et (ii) les lacunes majeures dans la recherche sur le sujet.

Méthodes

Des recherches ont été réalisées dans MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PSYCINFO et la bibliothèque Cochrane afin de trouver les revues publiées entre le 1er janvier 1995 et le 17 mars 2009. Les études devaient consister en des revues systématiques, des revues narratives, des métasynthèses ou des méta-ethnographies qualitatives d'implémentation d'e-santé. Une double analyse fouillée a été effectuée parmi les résumés et les journaux, et les données ont été extraites par pays d'origine, domaine d'e-santé, date de publication, objectifs et méthodes, bases de données analysées, critères d'inclusion et d'exclusion et nombre de journaux inclus. Les données ont été analysées qualitativement au moyen d'une théorie du processus de normalisation comme cadre de codification explicatif.

Résultats

Les critères d'inclusion ont été respectés par 37 journaux, 20 avaient été publiés entre 1995 et 2007, et 17 entre 2008 et 2009. La qualité méthodologique était faible: 19 journaux ne spécifiaient pas les critères d'inclusion et d'exclusion, et 13 n'indiquaient pas le nombre exact d'articles analysés. L'utilisation de la théorie du processus de normalisation comme cadre conceptuel a permis de révéler le peu d'attention portée à: (i) le travail visant à justifier les systèmes d'e-santé, en spécifiant leurs objectifs et leurs avantages, en établissant leur valeur pour les utilisateurs et en planifiant leur implémentation; (ii) les facteurs soutenant ou entravant l'engagement et la participation; (iii) les effets sur les rôles et les responsabilités; (iv) la gestion des risques, et (v) les moyens par lesquels les processus d'implémentation pourraient être reconfigurés par les connaissances des utilisateurs.

Conclusion

La documentation publiée se concentrait sur les problèmes organisationnels, négligeant le cadre social plus large qui doit être pris en compte en cas d'introduction de nouvelles technologies.

Resumen

Objetivo

Realizar una revisión sistemática de la literatura existente sobre la implementación de la telemedicina para identificar: (i) los obstáculos y estímulos para la implementación de la telemedicina, y (ii) las lagunas pendientes en la investigación sobre el tema.

Métodos

Se realizó una búsqueda en MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PSYCINFO y la Cochrane Library de revisiones publicadas entre el 1 de enero de 1995 y el 17 de marzo de 2009. Los estudios debían ser revisiones sistemáticas, revisiones narrativas, metasíntesis cualitativas o metaetnografías sobre la implementación de la telemedicina. Los resúmenes y documentos se investigaron doblemente y se extrajeron los datos del país de origen, el área de la telemedicina, la fecha de publicación, los objetivos y métodos, las bases de datos buscadas, los criterios de inclusión y exclusión y el número de documentos. Se analizaron los datos de forma cualitativa mediante un proceso de normalización como marco de codificación explicativo.

Resultados

De los documentos analizados, 37 cumplían con los criterios de inclusión, 20 habían sido publicados entre 1995 y 2007 y, 17, entre 2008 y 2009. La calidad metodológica fue escasa: 19 documentos no especificaban los criterios de inclusión y exclusión y 13 no indicaban el número concreto de artículos examinados. El uso de un proceso de normalización como marco conceptual reveló la poca atención que se había prestado a: (i) el trabajo dirigido a dotar de sentido a los sistemas de telemedicina, especificando sus objetivos y beneficios, estableciendo su valor para los usuarios y planificando su implementación; (ii) los factores que promueven o dificultan el compromiso y la participación; (iii) los efectos sobre las funciones y responsabilidades; (iv) la gestión del riesgo, y (v) los modos en los que los procedimientos de implementación podrían reconfigurarse con los conocimientos generados por los usuarios.

Conclusión

La literatura publicada se centró en cuestiones organizativas, descuidando el vasto marco social que debe tenerse en consideración a la hora de introducir nuevas tecnologías.

ملخص

الغرض

إجراء استعراض منهجي للأبحاث المنشورة المعنية بتنفيذ الصحة الإلكترونية بغية تحديد: (1) عوائق وتيسيرات تنفيذ الصحة الإلكترونية و(2) الفجوات القائمة في الأبحاث المعنية بالموضوع.

الطريقة

تم البحث في قواعد بيانات MEDLINE و EMBASEو CINAHLو PSYCINFOوCochrane Library لاستعراض الأبحاث المنشورة في الفترة من 1 يناير 1995 إلى 17 مارس 2009. وكان لابد أن تكون الدراسات عبارة عن استعراضات منهجية أو استعراضات سردية أو استعراضات كيفية للبنية التجميعية الوصفية أو الاثنوغرافية الوصفية لتنفيذ الصحة الإلكترونية. وقد خضعت الملخصات والأوراق لفحص مزدوج وتم استخلاص البيانات على أساس بلد المنشأ ومجال الصحة الإلكترونية وتاريخ النشر والأهداف والأساليب وقواعد البيانات التي تم البحث فيها ومعايير الإدراج والاستبعاد وعدد الأوراق البحثية المدرجة. وخضعت البيانات لتحليل كيفي باستخدام نظرية عملية التسوية بوصفها إطارًا ترميزيًا إيضاحيًا.

النتائج

لبت 37 ورقة بحثية معايير الإدراج؛ وتم نشر 20 ورقة بحثية في الفترة ما بين 1995 و2007 و17 ورقة بحثية في الفترة ما بين 2008 و2009. وكانت الجودة المنهجية ضعيفة: لم تحدد 19 ورقة بحثية معايير الإدراج والاستبعاد، ولم تشر 13 ورقة بحثية إلى العدد الدقيق للمقالات التي تم فحصها. وقد كشف استخدام نظرية عملية التسوية بوصفها إطارًا مفاهيميًا عن اهتمام قليل نسبيًا بما يلي: (1) العمل الموجه لفهم نظم الصحة الإلكترونية، وتحديد أغراضها وفوائدها، وتوضيح قيمتها للمستخدمين، وتخطيط تنفيذها، (2) العوامل لتي تعزز أو تمنع الإشراك والمشاركة، (3) الآثار المترتبة على الأدوار والمسؤوليات، (4) إدارة المخاطر، (5) الطرق التي يمكن من خلالها إعادة تكوين عمليات التنفيذ باستخدام المعرفة الناتجة من جانب المستخدم.

الاستنتاج

ركزت الأبحاث المنشورة على المسائل التنظيمية، وأهملت الإطار الاجتماعي الأوسع الذي يتعين وضعه في الاعتبار عند طرح تكنولوجيات جديدة.

摘要

目的

系统审阅电子卫生实施方面的文献,以识别:(1)电子卫生实施的障碍和推动因素;(2)此主题研究方面的明显缺口。

方法

检索 MEDLINE、EMBASE、CINAHL、PSYCINFO 和 Cochrane 库,查找 1995 年 1月 1 日到 2009 年 3 月 17 日之间发表的综述。研究必须是电子卫生实施方面的系统性综述、叙述性综述、定性综合集成或元人种学。摘要和文章经过反复筛查,内容按照来源国、电子卫生领域、发表日期、目的和方法、检索数据库、纳入与排除标准以及所包括文章数目提取。采用规范化过程理论作为解释编码框架对数据进行了定性分析。

结果

37 篇文章符合纳入标准;其中 20 篇发表于 1995 年到 2007 年之间,17 篇发表于 2008年到 2009 年之间。方法学质量不佳:19 篇文章没有指定纳入和排除的标准,13 篇没有表明被筛选论文的精确数量。将规范化过程理论作为一种概念性框架使用,揭示了人们相对很少关注:(1)有助于理解电子卫生系统的工作:说明其用途和效益、建立其对用户的价值以及实施的规划;(2)促进或抑制投身和参与的因素;(3)作用和责任的影响;(4)风险管理以及(5)用户产生的知识对实施过程可能进行的重新改造所采取的方法。

结论

发表的文献将重点放在了组织问题上,忽视了引入新技术时必须考虑的更广泛的社会框架。

Резюме

Цель

Провести систематический обзор литературы по внедрению электронного здравоохранения для выявления: (i) факторов, препятствующих и способствующих внедрению электронного здравоохранения и (ii) наиболее существенных пробелов в исследованиях по этой теме.

Методы

Для поиска материалов, опубликованных в период с 1 января 1995 г. по 17 марта 2009 г., использовались ресурсы MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PSYCINFO, а также Кокрановская библиотека. Рассматривались систематические обзоры, описательные обзоры, а также работы, содержащие качественный мета-синтез либо мета-этнографию о внедрении электронного здравоохранения. Был выполнен двойной отбор тезисов и исследовательских работ, при этом данные извлекались по стране происхождения, области электронного здравоохранения, дате публикации, целям и методам, базам данных, в которых производился поиск, критериям включения и исключения и количеству рассмотренных статей. Данные подверглись качественному анализу с использованием теории нормализации в рамках подхода толковательного кодирования.

Результаты

Критериям включения соответствовало 37 исследовательских работ; 20 из них были опубликованы между 1995. и 2007 гг., а 17 – между 2008 и 2009 гг. Методологическое качество работ было недостаточным: в 19 работах отсутствовало четкое определение критериев включения и исключения, а в 13 не было указано точное количество рассмотренных статей. Использование теории нормализации в качестве концептуальной основы обнаружило, что относительно небольшое внимание уделялось: (i) работе, направленной на придание смысла системам электронного здравоохранения, определение их целей и преимуществ, установление их стоимости для пользователей и планирование их внедрения, (ii) факторам, способствующим или препятствующим вовлечению и участию, (iii) влиянию на роли и обязанности, (iv) управлению рисками и (v) возможным способам перестройки процессов внедрения с помощью знаний пользователя.

Вывод

Опубликованная литература сосредоточена на организационных проблемах, пренебрегая более широкими социальными рамками, которые следует учитывать, внедряя новые технологии.

Introduction

Health-care providers have increasingly sought to utilize e-health systems that employ information and communications technologies to widen access, improve quality and increase service efficiency. Enthusiasm for technological innovation around e-health among policy-makers and health officials has, however, not always been matched by uptake and utilization in practice.1,2 Professional resistance to new technologies is cited as a major barrier to progress, although evidence for such assertions is weak.3 Implementing and embedding new technologies of any kind involves complex processes of change at the micro level for professionals and patients and at the meso level for health-care organizations themselves. The European Union has recently argued that implementing e-health strategies “has almost everywhere proven to be much more complex and time-consuming than initially anticipated”.4

Over the past decade the number of primary studies evaluating the practical implementation and integration of e-health systems has steadily grown. Sometimes these studies describe important successes, but more often they are accounts of complex processes with ambiguous outcomes. As the research community has sought to make sense of these studies, systematic reviews attempting to identify and describe “barriers” and “facilitators” to implementation have proliferated. Although the reviews have furthered knowledge by identifying factors thought to influence implementation processes and their outcomes, the underlying mechanisms at work have not been well characterized or explained. The literature is fragmented across multiple subspecialty areas, so those charged with designing and implementing e-health systems may find it difficult to locate an appropriate body of evidence and to determine the relevance of that evidence to their specific circumstances.

In this meta-review we have sought to address these problems in two ways. First, we have performed a systematic review of reviews of e-health implementation studies, focusing on implementation processes rather than outcomes, to critically appraise such reviews, evaluate their methods, synthesize their results and highlight their key messages. Our meta-review has enabled us to explore and evaluate a large and fragmented body of research in a coherent and economical way. Second, we have interpreted our results in the light of an explanatory framework – Normalization Process Theory (NPT)5,6 – that specifies mechanisms of importance in implementation processes. This approach has facilitated the explanation of those factors shown to influence the implementation of e-health systems in practice and allowed us to identify important gaps in the literature and to make rational recommendations for further primary research.

The objective of this review was to synthesize and summarize the findings of identified reviews and inform current and future e-health implementation programmes. The review set out to answer two key questions: (i) What does the published literature tell us about barriers and facilitators to e-health implementation? (ii) What, if any, are the main research gaps?

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Box 1 lists the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We used a previously developed method of categorization to classify e-health interventions into four domains:7 management systems, communication systems, computerised decision support systems and information resources.

Box 1. Inclusion/exclusion criteria for systematic review of reviews on e-health implementation.

Inclusion

Papers on the subject of e-health and its implementation that met the following criteria were included:

Systematic reviews: structured search of bibliographic and other databases to identify relevant literature; use of transparent methodological criteria to exclude papers not meeting an explicit methodological benchmark; presentation of rigorous conclusions about outcomes.

Narrative reviews: purposive sampling of the literature; use of theoretical or topical criteria to include papers on the basis of type, relevance and perceived significance, with the aim of summarizing, discussing and critiquing conclusions.

Qualitative meta-syntheses or meta-ethnographies: structured search of bibliographic and other databases to identify relevant literature; use of transparent methods to draw together theoretical products, with the aim of elaborating and extending theory.

Exclusion

Secondary analyses (including qualitative meta-syntheses or meta-ethnographies) of existing data sets for the purpose of presenting cumulative outcomes from personal research programmes.

Secondary analyses (including qualitative meta-syntheses or meta-ethnographies) of existing data sets for the purpose of presenting integrative outcomes from different research programmes.

Discussions of literature included in contributions to theory building or critique.

Summaries of the literature for the purpose of information or commentary.

Editorial discussions that argued the case for a field of research or a course of action.

Papers whose abstract identified them as reviews but that lacked supporting evidence in the main text (e.g. details on the databases searched or the selection criteria).

Finding relevant studies

We searched the following electronic bibliographic databases: MEDLINE; EMBASE; CINAHL; PSYCINFO; the Cochrane Library, including the Cochrane Database of Systematic reviews and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; DARE; the National Health Service (NHS) Economic Evaluation Database, and the Health Technology Assessment Database. Box 2 describes our search terms.

Box 2. Search terms used for systematic review of reviews on e-health implementation.

Thesaurus terms referring to e-health interventions were: Medical-Informatics-Applications; Management-Information-Systems; Decision-Making-Computer-Assisted; Diagnosis-Computer-Assisted; Therapy-Computer-Assisted; Medical-Records-Systems-Computerized; Medical-Order-Entry-Systems; Electronic-Mail; Videoconferencing; Telemedicine; Computer-Communication-Networks; Internet.

Where appropriate, thesaurus terms were exploded to include all terms below the searched term in the thesaurus tree. The lowest term was always exploded.

There are no thesaurus terms for implementation, so this concept was searched for by looking for the following text words in title, keywords or abstract: Routin*; Normali?*; Integrat*; Facilitate*; Barrier*; Implement*; Adopt*. The concepts of e-health intervention and implementation were combined, and then the search was limited by publication type (i.e. review or meta-analysis).

We limited the MEDLINE database search to studies published in any language from 1990 to 2009. None of the non-English-language citations or of the papers published before 1995 were relevant. Hence, the MEDLINE search was re-run for only English-language reviews published between 1 January 1995 and 31 July 2009. These limits were used for searching all other databases. Each database’s thesaurus terms were used to perform the search.

Data abstraction and analysis

Citations were downloaded into Reference Manager 11 (ISI ResearchSoft, Carlsbad, United States of America), and screened by two reviewers. If either reviewer could not exclude the paper based on the abstract or citation, the full paper was obtained. All papers obtained were double screened. In case of disagreement about inclusion or exclusion of a given paper, all reviewers read the paper and reached agreement through discussion.

Data were extracted in two stages. First we used a standardized data extraction instrument to categorize papers on the basis of country of origin; e-health domain; publisher; date of publication; review aims and methods; databases searched within the review; inclusion and exclusion criteria of review; number of papers identified and number included in the review.

Second, as the literature under study focused on implementation processes rather than outcomes, we analysed the extracted data qualitatively using NPT, which has four constructs (coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring) as a coding framework.5,6 This theory provides a conceptual framework to explain the processes by which new health technologies and other complex interventions are routinely operationalized in everyday work (embedded) and sustained in practice (integrated).8,9 Use of this framework to aid data analysis in systematic reviews of qualitative data has recently been described.10 For every paper two reviewers judged whether material relevant to the four constructs of NPT was present or absent, using the coding frame shown in Table 1. As this was a qualitative content analysis,11 we did not try to quantify the weight put on any one NPT construct in a given review. Each statement in a paper relating to findings regarding barriers or facilitators to e-health implementation was treated as an “attributive statement”; two reviewers coded these statements to the relevant construct of the NPT. If an “attributive statement” could not be coded to the NPT framework, this was stated to ensure that issues outside the scope of the theory would still be captured. Dual coding enabled differences in coding and interpretation to be identified and discussed. Disagreement, which was minimal, was resolved through discussion. If any areas of disagreement remained, a final reviewer served as arbiter.

Table 1. Normalization process theory coding framework used for qualitative analysis of review data on e-health implementation .

| Coherence (Sense-making work) |

Cognitive participation (Relationship work) |

Collective action (Enacting work) |

Reflexive monitoring (Appraisal work) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Differentiation Is there a clear understanding of how a new e-health service differs from existing practice? |

Enrolment Do individuals “buy into” the idea of the e-health service? |

Skill set workability How does the innovation affect roles and responsibilities or training needs? |

Reconfiguration Do individuals try to alter the new service? |

|

Communal specification Do individuals have a shared understanding of the aims, objectives and expected benefits of the e-health service? |

Activation Can individuals sustain involvement? |

Contextual Integration Is there organizational support? |

Communal appraisal How do groups judge the value of the e-health service? |

|

Individual specification Do individuals have a clear understanding of their specific tasks and responsibilities in the implementation of an e-health service? |

Initiation Are key individuals willing to drive the implementation? |

Interactional workability Does the e-health service make people’s work easier? |

Individual appraisal How do individuals appraise the effects on them and their work environment? |

|

Internalization Do individuals understand the value, benefits and importance of the e-health service? |

Legitimation Do individuals believe it is right for them to be involved? |

Relational integration Do individuals have confidence in the new system? |

Systematization How are benefits or problems identified or measured? |

The methods used for study identification and data collection in this study were in keeping with the recent PRISMA statement.12 However, as this was a review of process rather than outcome studies, some aspects of the PRISMA statement were not applicable.

Results

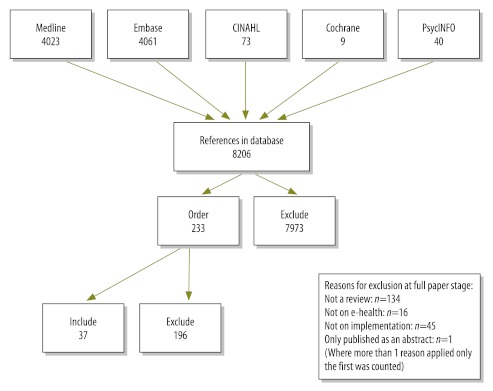

From 8206 unique citations screened, we excluded 7973 on the basis of the title or abstract and retrieved 233 full-text articles. Of these, 37 met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Of note, 20 of these reviews were published between 1995 and 2007 and 17 were published in the following two years.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study selection in systematic review of reviews on e-health implementation

Of the 37 included reviews, 18 originated in the United States of America, 10 in Canada, 3 in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, 2 in the Netherlands and 1 each in Australia, Germany, Malaysia and Norway.13–49 Reviews generally covered one or more e-health domains: eight reported on management systems; 10 on communication systems; 6 on decision support; 1 mainly on information systems, and 12 on combinations of these. Full details of included papers are available from the authors.

When judged against the PRISMA checklist,12 many of the included reviews were methodologically poor. For example, 5 of the 37 reviews did not clearly describe the databases searched.22,25,32,36,49 Information on search strategies was often rudimentary. Of the 37 included reviews, 7 searched only one or two databases or sources, such as the proceedings of a particular conference.14,15,28,38,42,44,48 Information about study selection criteria was also inadequate: 19 of the 37 reviews did not specify the criteria for inclusion or exclusion.15,16,18,21–23,25,26,29,31–36,41–44 For 13 of the 37 papers reviewed it was impossible to ascertain precisely how many studies had been included.17,18,22,23,25,26,28,29,32,35,38,41,42.

As the reviews under investigation dealt with organizational and other processes rather than with numeric outcome measures, the PRISMA checklists for summary measures and result synthesis were not applicable. NPT was used to aid analysis and conceptualization of the qualitative data regarding barriers and facilitators of implementation.

Content analysis of the 37 reviews identified 801 attributive statements about implementation processes that could be interpreted using NPT as an explanatory framework.

Coherence

Coherence refers to the “sense-making" work undertaken when a new e-health service is implemented (e.g. to determine whether users see it as differing from existing practice, have a shared view of its purpose, understand how it will affect them personally and grasp its potential benefits). A surprising and important result of this review was the discovery that work directed at making sense of e-health systems received very little coverage. Content analysis of the reviews showed it to be the focus of less than 12% (95/801) of the attributive statements. Coherence work was seen to be concerned with preparatory activities – often policy building or dissemination of information – undertaken either locally or nationally.

Since “sense-making” work is an important aspect of implementation, this review reveals an important gap in the literature. We do not know whether the gap reflects the exclusion of coherence work from process-oriented studies (which is possible if evaluations commence in the delivery phase of a project) or the systematic absence of sense-making work itself.

Cognitive participation

Cognitive participation focuses upon the work undertaken to engage with potential users and get them to “buy into” the new e-health system. Although this work of relating and engaging with users is central to the successful implementation of any new technology, work aimed at actively involving health professionals in e-health services rarely figured in the reviews we examined. The same was true of work leading to the initiation and legitimation of health technologies or geared towards sustaining them in practice. Less than 11% (88/801) of attributive statements fell within this category, and those that did took the form of general recommendations rather than specific design and delivery considerations. For example, Hilty23 proposes ways to encourage health professional participation, including “incentives for each of the parties involved”.

Other issues that fell within the cognitive participation category included a range of actions to legitimize participation in the implementation process and promote it as a worthwhile activity, such as the recruitment of local “champions”. Such champions were seen as having the ability to promote utilization of new e-health services by more reticent colleagues. However, this approach could be a double-edged sword. Health professionals who enthusiastically support e-health can get colleagues to enrol in and commit to e-health programmes. However, those who project a negative attitude can jeopardize the staff commitment needed to make an e-health system work and thus impede implementation.

Since participation and engagement are vital for the success of new technologies, the lack of coverage in the reviews of the factors that promote or inhibit user engagement and participation is clearly a major weakness in the literature.

Collective action

Work involved in implementing or enacting e-health systems was the topic of 65% (518/801) of the attributive statements identified. The emphasis in this domain was on the work performed by individuals, groups of professionals or organizations in operationalizing a new technology in practice. We found that the research emphasis changed over time. Up to 2007 the emphasis lay on organizational issues, but after that year it shifted towards socio-technical issues (e.g. how e-health systems affected the everyday work of individuals).

Addressing organizational issues

Most reviews focused on the ways in which the e-health innovation affected organizational structures and goals. This was especially true up to 2007, when 35% (142/411) of the attributive statements identified focused on this point, as opposed to only 20% (77/390) after 2007. The literature highlighted the need for adequate resources, particularly financial. Administrative support, policy support, standards and interoperability also fell within this research category.

This area’s emphasis is on the contextual integration of e-health systems, particularly on the extent to which they are managed and resourced. The focus on management is not surprising, but the emphasis on a “top down” approach draws attention away from other equally important aspects of collective action.

Effects on health care tasks

The interactional workability of e-health systems accounted for less than 18% of the attributive statements identified during content analysis. Many of these focused on the “ease of use” of the new systems for clinicians, with the underlying assumption that clinicians would be deterred from or resistant to using systems that added complexity or required additional effort or time.

Ease of use for patients or other service users (or even health professionals besides clinicians, such as nurses) did not figure prominently in the reviews we investigated. However, the effect of e-health systems on physician–patient interaction did receive some attention, as exemplified by the following quote:

“… an effective clinical decision support system must minimise the effort required by clinicians to receive and act on system recommendations”.30

Thus, implementation may be retarded or destabilized by the competing priorities of powerful participants.

Confidence and accountability

The relational integration of e-health systems (confidence, security and accountability) accounted for 15% (116/801) of the attributive statements identified. Such concerns could act as either facilitators or barriers. Users may see in e-health technologies a way to reduce errors, which would encourage uptake; alternatively, security and safety concerns could undermine confidence in e-health systems and hinder their widespread utilization.

Roles, responsibilities and training

Roles, responsibilities and training or support issues accounted for only about 10% (77/801) of attributive statements. Most emphasis was placed on the need to adequately train staff members for engagement in implementation, although division of labour was also a concern, as were effects on workload. However, these issues were often discussed superficially, without examining the types of training or ongoing support that would be required.

Reflexive monitoring

While the majority of attributive statements identified in the content analysis dealt with managerial interventions and controls, much less information was provided on the ways in which managers and other users appraise whether an e-health intervention is worthwhile or not. Only 13% (104/801) of the attributive statements fell within this category. Most of these dealt with evaluation and monitoring and how they are used to influence utilization and future e-health implementations. However, evaluation was also promoted as necessary to ensure that safety concerns were addressed.

Evaluation could, of course, either allay concerns or confirm the need for amendments to the e-health service being implemented. There was little evidence of local appraisals or of the ways in which implementation processes might be reconfigured by user-produced knowledge.

Only 6% of issues fell outside our coding framework, either because they were strictly technical and attitudinal or because they were so generic and vague, without accompanying contextual data, that it was not possible to determine whether the concept really lay outside the model or was simply too general to be coded.

Discussion

A thorough and systematic search of reviews published over the preceding 15 years identified 37 reviews on the implementation of e-health technologies in health-care settings. Most were from North America. Methodological deficiencies were common and the findings should be interpreted with caution. The number of publications has risen rapidly since 2008, which suggests that there is growing awareness of the need to understand and address issues related to implementation if e-health services are to become a core component of routine service delivery.

This review breaks new ground. It not only collates and summarizes data but also analyses it and interprets it within a theoretical framework. Our approach has allowed us to explore the factors that facilitate and hinder implementation, identify gaps in the literature and highlight directions for future research. In particular, this work highlights a continued focus on organizational issues, which, despite their importance, are only one among a range of factors that need to be considered when implementing e-health systems.7–9,50

Although our meta-review was rigorous and carefully executed and employed a robust conceptual framework, it has limitations. Since not all primary research has been captured by previous reviews, our meta-review does not include findings from all studies in this field. Furthermore, review data is two steps removed from primary data, and the quality of the primary research may not be properly assessed in reviews of substandard quality. Finally, since the reviews we identified were of poor quality on average and their search strategies were not always comprehensive, their findings may be biased.

Conclusion

Our review has revealed a growing emphasis on problems related to e-health systems’ workability but relatively little attention to: (i) e-health’s effects on roles and responsibilities; (ii) risk management; (iii) ways to engage with professionals; and (iv) ensuring that the potential benefits of new technologies are made transparent through ongoing evaluation and feedback. These areas deserve more empirical investigation, as do ways to identify and anticipate how e-health services will impact everyday clinical practice. This involves examining how new e-health services will affect clinical interactions and activities and the allocation and performance of clinical work. Also in need of investigation are the effects of different methods of engaging with professionals before and during the implementation of e-health services.

Funding:

We thank the Service and Delivery Organisation (SDO) for funding the study via project grant 08/1602/135. This article presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) SDO programme. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The NIHR SDO programme is funded by the Department of Health, United Kingdom. No funding bodies played any role in the design, writing or decision to publish this manuscript.

Competing interests:

CM and TF led on developing normalization process theory, and all authors have made important contributions to its development.

References

- 1.May CR, Finch TL, Cornford J, Exley C, Gately C, Kirk S, et al. Integrating telecare for chronic disease management in the community: What needs to be done? BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:131. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jha AK, DesRoches C, Campbell EG, Donelan K, Rao SR, Ferris TG, et al. Use of electronic health records in US hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1628–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0900592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balfour DC, Evans S, Januska J, Lee HY, Lewis SJ, Nolan SR, et al. Health information technology — results from a roundtable discussion. J Manag Care Pharm. 2009;15:10–7. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.s6-b.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watson R. European Union leads way on e-health but obstacles remain. BMJ. 2010;341:c5195. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.May C, Finch T. Implementation, embedding, and integration: an outline of normalization process theory. Sociology. 2009;43:535–54. doi: 10.1177/0038038509103208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.May CR, Mair FS, Finch T, Macfarlane A, Dowrick C, Treweek S, et al. Development of a theory of implementation and integration: normalization process theory. Implement Sci. 2009;4:29. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mair FS, May C, Murray E, Finch T, Anderson G, O'Donnell C, et al. Understanding the implementation and integration of e-Health services. Report for the NHS Service and Delivery R & D Organisation (NCCSDO) London: SDO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elwyn G, Legare F, Edwards A, van der Weijden T, May C. Arduous implementation: does the normalisation process model explain why it is so difficult to embed decision support technologies for patients in routine clinical practice. Implement Sci. 2008;3:57. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murray E, Burns J, May C, Finch T, O'Donnell C, Wallace P, et al. Why is it difficult to implement e-health initiatives? A qualitative study. Implement Sci. 2011;6:6. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Normalization Process Theory [Internet]. May C, Murray E, Finch T, Mair F, Treweek S, Ballini L et al. Normalization process theory on-line users’ manual and toolkit. 2010. Available from: http://www.normalizationprocess.org [accessed 27 March 2012]

- 11.Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers London: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adaji A, Schattner P, Jones K. The use of information technology to enhance diabetes management in primary care: a literature review. Inform Prim Care. 2008;16:229–37. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v16i3.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Botsis T, Hartvigsen G. Current status and future perspectives in telecare for elderly people suffering from chronic diseases. J Telemed Telecare. 2008;14:195–203. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2008.070905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broens TH, Huis in’t Veld RM, Vollenbroek-Hutten MM, Hermens HJ, van Halteren AT, Nieuwenhuis LJ. Determinants of successful telemedicine Implementations: a literature study. J Telemed Telecare. 2007;13:303–9. doi: 10.1258/135763307781644951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, Maglione M, Mojica W, Roth E, et al. Systematic review: impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical Care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:742–52. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Copen J, Richards P. Systematic review on PDA clinical application implementation and lessons learned. J Inf Technol Healthc. 2008;6:114–28. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demaerschalk BM, Miley ML, Kiernan TEJ, Bobrow BJ, Corday DA, Wellik KE, et al. Stroke telemedicine. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:53–64. doi: 10.4065/84.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzpatrick LA, Melnikas AJ, Weathers M, Kachnowski SW. Understanding communication capacity: communication patterns and ICT usage in clinical settings. J Healthc Inf Manag. 2008;22:34–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gagnon MP, Legare F, Labrecque M, Fremont P, Pluye P, Gagnon J, et al. Interventions for promoting information and communication technologies adoption in healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;1:CD006093. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006093.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gruber D, Cummings GG, LeBlanc L, Smith DL. Factors influencing outcomes of clinical information systems implementation: a systematic review. CIN. 2009;27:151–63. doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e31819f7c07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hebert MA. Moving research into practice: a decision framework for integrating home telehealth into chronic illness care. Int J Med Inform. 2006;75:786–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hilty DM. Telepsychiatry: an overview for psychiatrists. CNS Drugs. 2002;16:527–48. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200216080-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarvis-Selinger S, Chan E, Payne R, Plohman K, Ho K. Clinical telehealth across the disciplines: lessons learned. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14:720–5. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2007.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jennett PA, Scott RE, Affleck Hall L, Hailey D, Ohinmaa A, Anderson C, et al. Policy implications associated with the socioeconomic and health system impact of telehealth: a case study from Canada. Telemed J E Health. 2004;10:77–83. doi: 10.1089/153056204773644616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jennett PA. Preparing for success: readiness models for rural telehealth. J Postgrad Med. 2005;51:279–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jimison H, Gorman P, Woods S, Nygren P, Walker M, Norris S, et al. Barriers and drivers of health information technology use for the elderly, chronically ill and underserved. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2008;175:1–1422. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson KB. Barriers that impede the adoption of pediatric information technology. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:1374–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.12.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones R. The role of health Kiosk in 2009: literature and informant review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:1818–55. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6061818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawamoto K. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330:765–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38398.500764.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kukafka R. Grounding a new information technology implementation framework in behavioral science: a systematic analysis of the literature on IT use. J Biomed Inform. 2003;36:218–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leatt P. IT solutions for patient safety - best practices for successful implementation in healthcare. Healthc Q. 2006;9:94–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu YC, Xiao Y, Sears A, Jacko JA. A review and a framework of handheld computer adoption in healthcare. Int J Med Inform. 2005;74:409–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ludwick DA, Doucette J. Adopting electronic medical records in primary care: lessons learned from health information systems implementation experience in seven countries. Int J Med Inform. 2009;78:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mack EH, Wheeler DS, Embi PJ. Clinical decision support systems in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10:23–8. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181936b23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mashima PA, Doarn CR. Overview of telehealth activities in speech-language pathology. Telemed J E Health. 2008;14:1101–17. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2008.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mollon B, Chong J, Jr, Holbrook AM, Sung M, Thabane L, Foster G. Features predicting the success of computerized decision support for prescribing: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2009;9:11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-9-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohinmaa A. What lessons can be learned from telemedicine programmes in other countries? J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12:S40–4. doi: 10.1258/135763306778393135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oroviogoicoechea C, Elliott B, Watson R. Review: evaluating information systems in nursing. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:567–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orwat C, Graefe A, Faulwasser T. Towards pervasive computing in health care - a literature review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8:26. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-8-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Papshev D. Electronic prescribing in ambulatory practice: promises, pitfalls, and potential solutions. Am J Manag Care. 2001;7:725–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peleg M. Decision support, knowledge representation and management in medicine. Yearb Med Inform. 2006;45:72–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shekelle PG, Morton SC, Keeler EB. Costs and benefits of health information technology. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) 2006;132:1–171. doi: 10.23970/ahrqepcerta132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Studer M. The effect of organizational factors on the effectiveness of EMR system implementation: What have we learned? Healthc Q. 2005;8:92–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Rosse F, Maat B, Rademaker CM, van Vught AJ, Egberts AC, Bollen CW. The effect of computerized physician order entry on medication prescription errors and clinical outcome in pediatric and intensive care: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1184–90. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vreeman DJ, Taggard SL, Rhine MD, Worrell TW. Evidence for electronic health record systems in physical therapy. Including commentary by Zimny NJ with author response. Phys Ther. 2006;86:434–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Waller R, Gilbody S. Barriers to the uptake of computerized cognitive behavioural therapy: a systematic review of the quantitative and qualitative evidence. Psychol Med. 2009;39:705–12. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yarbrough AK. Technology acceptance among physicians: a new take on TAM. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64:650–72. doi: 10.1177/1077558707305942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yusof MM, Stergioulas L, Zugic J. Health information systems adoption: findings from a systematic review. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2007;129:262–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.May C, Gask L, Atkinson T, Ellis N, Mair F, Esmail A. Resisting and promoting new technologies in clinical practice: the case of telepsychiatry. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:1889–901. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]