Abstract

Problem

In Zanzibar, United Republic of Tanzania, as in many developing countries, health managers lack faith in the national Health Management Information System (HMIS). The establishment of parallel data collection systems generates a vicious cycle: national health data are used little because they are of poor quality, and their relative lack of use, in turn, makes their quality remain poor.

Approach

An action research approach was applied to strengthen the use of information and improve data quality in Zanzibar. The underlying premise was that encouraging use in small incremental steps could help to break the vicious cycle and improve the HMIS.

Local setting

To test the hypothesis at the national and district levels a project to strengthen the HMIS was established in Zanzibar. The project included quarterly data-use workshops during which district staff assessed their own routine data and critiqued their colleagues’ data.

Relevant changes

The data-use workshops generated inputs that were used by District Health Information Software developers to improve the tool. The HMIS, which initially covered only primary care outpatients and antenatal care, eventually grew to encompass all major health programmes and district and referral hospitals. The workshops directly contributed to improvements in data coverage, data set quality and rationalization, and local use of target indicators.

Lessons learnt

Data-use workshops with active engagement of data users themselves can improve health information systems overall and enhance staff capacity for information use, presentation and analysis for decision-making.

Résumé

Problème

Au Zanzibar, République-Unie de Tanzanie, comme dans de nombreux pays en voie de développement, les gestionnaires de la santé manquent de confiance dans le système national d’information de la gestion sanitaire (HMIS, Health Management Information System). La mise en place de systèmes de collecte de données parallèles génère un cercle vicieux : les données de santé nationales sont peu utilisées étant donné leur qualité médiocre et leur faible utilisation n’aide guère à améliorer cette qualité.

Approche

Une approche d’action-recherche a été appliquée en vue de renforcer l’utilisation de l’information et d’améliorer la qualité des données au Zanzibar. Le principe sous-jacent était qu’un encouragement à l’utilisation par petites étapes successives pourrait favoriser la rupture du cercle vicieux et améliorer le HMIS.

Environnement local

Pour tester l’hypothèse au niveau du pays et du district, un projet visant à renforcer le HMIS a été implémenté au Zanzibar. Ce projet incluait des ateliers trimestriels d’utilisation de données durant lesquels les membres du personnel du district évaluaient leurs propres données de routine tout en analysant de façon critique les données de leurs collègues.

Changements significatifs

Les ateliers d’utilisation de données ont généré des informations qui ont été utilisées par les développeurs du logiciel d’information sanitaire du district pour améliorer l’outil. Le HMIS, qui ne couvrait initialement que les premiers soins des patients externes et les soins prénataux, a fini par couvrir tous les grands programmes de santé ainsi que tous les hôpitaux du district et de référence.

Leçons tirées

Les ateliers d’utilisation de données avec un engagement actif des utilisateurs de données eux-mêmes peuvent améliorer les systèmes d’information sanitaire de façon générale et optimiser l’utilisation de l’information, la présentation et l’analyse en vue de la prise de décision du personnel.

Resumen

Situación

En Zanzíbar, República Unida de Tanzanía, como en muchos países en desarrollo, los gestores de salud no tienen fe en el Sistema Nacional de Gestión Sanitaria. El establecimiento de sistemas de obtención de datos paralelos crea un círculo vicioso: los datos de salud nacionales se usan poco porque son de poca calidad, y su relativa falta de uso, a su vez, impide que su calidad mejore.

Enfoque

Se aplicó un enfoque de investigación-acción para aumentar la utilización de información y mejorar la calidad de los datos en Zanzíbar. La premisa subyacente era que la estimulación de la utilización en pequeños pasos graduales podría ayudar a romper el círculo vicioso y mejorar el Sistema Nacional de Gestión Sanitaria.

Marco regional

Para probar la hipótesis a nivel nacional y de distrito, se estableció un proyecto para fortalecer el Sistema Nacional de Gestión Sanitaria en Zanzíbar. El proyecto incluyó talleres de utilización de datos trimestrales en los que el personal del distrito evaluó sus datos rutinarios y criticó los de sus compañeros.

Cambios importantes

Los talleres de utilización de datos generaron aportaciones que los desarrolladores del software de información sanitaria del distrito emplearon para mejorar la herramienta. El Sistema Nacional de Gestión Sanitaria, que inicialmente solo cubría pacientes de atención primaria y atención prenatal, creció para abarcar todos los programas importantes de salud, así como hospitales de derivación y de distrito. Los talleres contribuyeron directamente mejorar la cobertura de datos, la calidad y racionalización del conjunto de datos, y el uso local de indicadores de objetivos.

Lecciones aprendidas

Los talleres de utilización de datos con participación activa de los usuarios de los datos pueden mejorar los sistemas de información de salud en conjunto, así como la capacidad del personal para utilizar, presentar y analizar la información para tomar decisiones.

ملخص

المشكلة

في زنزيبار، جمهورية تنزانيا المتحدة، كما في العديد من البلدان النامية، يفتقر مديرو الصحة إلى الإيمان بالنظام الوطني للمعلومات المتعلقة بإدارة شؤون الصحة (HMIS). ويتولد عن إنشاء نظم لجمع البيانات المتوازية حلقة مفرغة: يتم استخدام البيانات الصحية الوطنية بشكل ضئيل نظرًا لجودتها المنخفضة والافتقار النسبي لاستخدامها، مما يؤدي بدوره لأن تظل جودتها منخفضة.

الأسلوب

تم تطبيق أسلوب بحثي عملي لتعزيز استخدام المعلومات وتحسين جودة البيانات في زنزيبار. وكانت الفرضية الأساسية أن تشجيع الاستخدام من خلال خطوات تزايدية صغيرة قد يساعد في كسر الحلقة المفرغة وتحسين نظام المعلومات المتعلقة بإدارة شؤون الصحة (HMIS).

المواقع المحلية

بغرض اختبار الفرضية على الصعيد الوطني وعلى مستوى المناطق، تم إنشاء مشروع لتعزيز نظام المعلومات المتعلقة بإدارة شؤون الصحة (HMIS) في زنزيبار. وتضمن المشروع عملية فصلية حول استخدام البيانات قام موظفو المناطق خلالها بتقييم البيانات الروتينية الخاصة بهم واستعراض بيانات زملائهم.

التغيرات ذات الصلة

نتج عن الحلقات العملية حول استخدام البيانات مدخلات استخدمها مطورو برمجيات المعلومات الصحية الخاصة بالمناطق لتحسين الأداة. وتطور نظام المعلومات المتعلقة بإدارة شؤون الصحة (HMIS)، الذي لم يكن يغطي في البداية سوى مرضى الرعاية الأولية الخارجيين والرعاية خلال فترة الحمل، ليشمل في النهاية جميع البرامج الصحية الرئيسية ومستشفيات المناطق والإحالة. وقد ساهمت الحلقات العملية بشكل مباشر في التحسينات التي طرأت على تغطية البيانات وجودة مجموعة البيانات وترشيدها، والاستخدام المحلي للمؤشرات المستهدفة.

الدروس المستفادة

من الممكن أن تؤدي الحلقات العملية حول استخدام البيانات والمشاركة النشطة لمستخدمي البيانات أنفسهم إلى تحسين نظم المعلومات الصحية بشكل عام وتعزيز قدرات الموظفين على استخدام المعلومات وعرضها وتحليلها بغية صناعة القرار.

摘要

问题

正如许多发展中国家一样,坦桑尼亚联合共和国,在桑给巴尔,卫生管理人员对国家卫生管理信息系统(HMIS)缺乏信心。平行数据采集系统的建立形成一种恶性循环:国家卫生数据因为质量差而很少得到采用,反过来又因为相对缺少采用而使它们的质量一直很差。

方法

采用一种行动研究方法来加强桑给巴尔的信息使用并提高数据质量。基本前提是,鼓励循序渐进地增加使用可能有助于打破恶性循环并改善 HMIS。

当地状况

为了在国家和地区各级机构中检验这个假说,在桑给巴尔建立了一个项目以强化 HMIS。该项目包括季度数据使用情况研讨会,在此期间,地区工作人员评估自己的日常数据并评判其同事的数据。

相关变化

地区卫生信息软件开发者用数据使用情况研讨会得出的输入来改进工具。HMIS 最初只涵盖基层医疗门诊及产前保健,最终扩大到包括所有主要卫生计划和地区及转诊医院。研讨会对数据覆盖范围、数据集质量和合理化以及目标指标的本地使用有直接贡献。

经验教训

数据使用者自身积极参与数据使用情况研讨会可改进卫生信息系统整体情况,并增强工作人员的信息使用、呈现以及分析信息进行决策的能力。

Резюме

Проблема

В Занзибаре, Объединенная Республика Танзания, как и во многих развивающихся странах, руководители системы здравоохранения испытывают нехватку доверия к информационной системе управления здравоохранением (ИСУЗ). Создание параллельных систем сбора данных порождает порочный круг: данные национальной системы здравоохранения используются мало в силу их плохого качества, а относительная недостаточность их использования, в свою очередь, ведет к тому, что их качество остается плохим.

Подход

Для улучшения использования информации и повышения качества данных в Занзибаре был применен метод экспериментального исследования. Лежащая в его основе предпосылка состояла в том, что поощрение использования с помощью небольших и постепенно развиваемых мер сможет помочь разрушению сложившегося порочного круга и улучшению ИСУЗ.

Местные условия

Для проверки этой гипотезы на общенациональном и региональном уровнях в Занзибаре была основана программа по усилению ИСУЗ. Программа включала ежеквартальные семинары по использованию данных, в течение которых местные служащие оценивали собственные данные и критиковали данные своих коллег.

Осуществленные перемены

В ходе семинаров были получены предложения, которые были учтены разработчиками программного обеспечения региональной системы медицинской информации для ее улучшения. Система ИСУЗ, которая первоначально охватывала только амбулаторных пациентов первичной медицинской помощи и дородовой уход, выросла со временем до охвата всех основных медицинских программ, региональных и специализированных клиник. Семинары непосредственно способствовали улучшению охвата, качества и рационализации массива данных, а также более активному местному применению целевых показателей.

Выводы

Семинары по использованию данных с активным участием самих пользователей этих данных способны улучшить медицинские информационные системы в целом и увеличить возможности персонала в использовании информации, ее представлении и анализе для принятия решений.

Introduction

Good health information systems are crucial for addressing health challenges and improving health service delivery in developing countries.1 However, the quality of the data produced by such systems is often poor and the data are not used effectively for decision-making.2 Although there has been increasing international attention to the need to develop strong health information systems, it has proved difficult to do so for several reasons, including fragmentation and lack of coordination of health programmes and insistence by international agencies on maintaining their own vertical systems3; lack of shared data standards4; unrealistic ambitions5; inability of system developers to handle complex organizational, social and cultural issues6; and problems of sustainability.7 The Health Metrics Network, established in 2005, has been instrumental in addressing the problem of fragmentation in health information systems through its technical framework,8 which promotes a data warehouse approach to information system integration,3,9 and in creating global consensus on the need for all actors to join forces and work towards integrated systems. Zanzibar, in the United Republic of Tanzania, provides an early example of this shift towards integration and the use of an integrated data warehouse/repository application to achieve it.

A key hypothesis in the experience reported in this paper is that data quality and data use are interrelated: poor quality data will not be used, and because they are not used, the data will remain of poor quality; conversely, greater use of data will help to improve their quality, which will in turn lead to more data use. This hypothesis was tested through data-use workshops, which sought to encourage data use and enhance data quality by promoting systematic peer review, building teamwork and stimulating self-assessment, using indicators to measure targets.

Background and methods

Zanzibar consists of two islands, each making up a health zone; one island comprises six districts and the other four. As part of a health system strengthening project,10 in 2005 the Health Management Information System (HMIS) Unit of the Ministry of Health, with support from the Danish International Development Agency, launched a process aimed at strengthening the HMIS, improving data reporting and implementing the District Health Information Software (DHIS) (Fig. 1). DHIS is a software tool for collection, validation, analysis and presentation of aggregate statistical data managed in multiple data sets and tailored to support integrated health information management activities. It is designed to serve as a district-based country data warehouse that addresses both local and national needs. Version 2 of the program is an open-source web-based software package available free of charge (www.DHIS2.org).11 It is being used by national health management information systems in numerous countries in Africa and Asia.

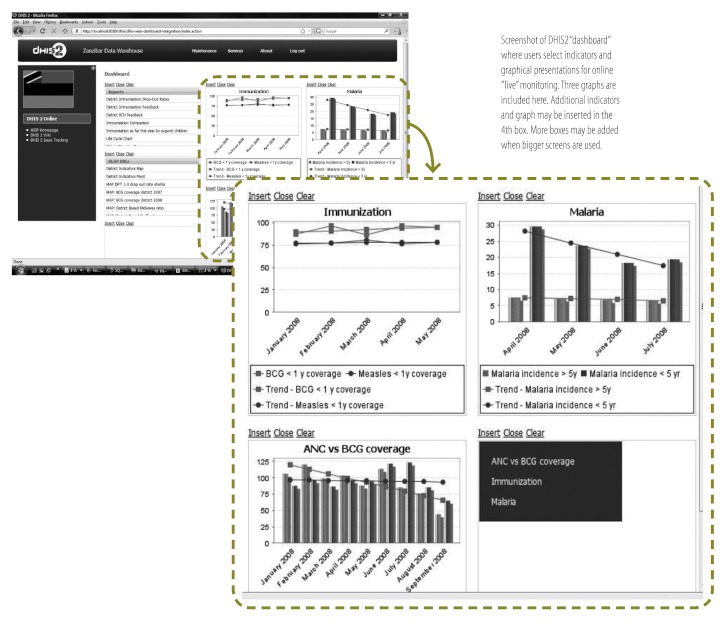

Fig. 1.

District Health Information Software screenshot and example of data presentation

Note: In this illustration three sets of indicators are graphed:

Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) and measles immunization. Immunization trends for measles vaccine and BCG for the year are stable, since the Expanded Programme on Immunization has always used local data and data quality is therefore good.

Antenatal care versus BCG coverage. As participants began using data on women’s first visit to antenatal care, antenatal care coverage dropped from an unrealistic 125% to a more realistic 75% level.

Malaria. Since the importance of using rapid diagnostic tests was stressed during data-use workshops, malaria “incidence” dropped dramatically in children under five as clinicians moved from symptomatic diagnosis towards laboratory-confirmed diagnosis.

Quarterly data-use workshops were held in which district health management team (DHMT) members (roughly seven per district) presented their district’s routine data to their peers from other districts. The workshops lasted approximately 5 days each and were facilitated by external facilitators from the Health Information Systems Programme, supported by the Zanzibar HMIS Unit and selected health zone staff. The workshops began in 2005 and have continued since then. Most workshops are now being run by the HMIS Unit without outside help.

During the workshops, each district or programme presents and assesses its own data using standardized analysis templates based on the Millennium Development Goals and local strategic plans, after which their peers discuss and critique these presentations. The workshops encourage self-assessment and provide an opportunity to compare presentations, identify common issues relating to data quality and health services performance, promote local involvement and improve data quality. They also contribute direct feedback to HMIS planners for the revision of indicators and data sets and to software developers for the design of new functionalities, reports and other features.

As participants became more familiar and proficient with data-handling processes (e.g. indicators, analysis, display) and the tools (e.g. DHIS, Excel pivot tables and graphs), the length of their participation in workshops became shorter. At the same time, as more programmes started to use DHIS, more programme managers participated and the overall workshop duration increased.

Achievements

Improvements were noted in the following areas as a result of the data-use workshops:

Data collection

Forms were simplified on the basis of revised indicator and data sets, dramatically reducing the number of data elements collected and thus the workload of facility staff. This simplification was achieved largely because workshop participants realized that it was unnecessary to disaggregate some data (e.g. by age, sex or uncommon diseases) as the disaggregated data were not being used. Similarly, duplication of data collection by different programmes was virtually eliminated (for example, the Reproductive and Child Health Programme stopped collecting data on human immunodeficiency virus [HIV] infection, immunization and malaria) and data gaps were filled. Changes were agreed collectively through improved communication fostered by the workshops and supported by strong leadership from the Ministry of Health.

Data submission improved considerably, with districts reporting more regularly on most data forms. The process began modestly, focusing on a couple of programmes, but other programmes gradually saw the value of using the national HMIS rather than their own parallel data collection systems, and more programmes (and hospitals, including the national referral hospital) were added. Indicator set changes, including some reductions in indicators, were negotiated with programmes jointly each year through the HMIS Unit, the Health Information Systems Programme and the two health zones.

Integration

The workshops provided a stimulus for integration of the previously separate data sets and databases of primary health-care units, hospitals and programmes, and allowed district health management team members to gain a better idea of the roles played by different actors, which improved practical collaboration. Integration of programme data into a single DHIS database – with one national data set covering the Millennium Development Goals indicators, poverty reduction and national strategic plan indicators and programme-specific indicators – was a major achievement. Integration was a slow process, however, as some externally funded programmes were initially reluctant to share “their” data and did not trust the quality or timeliness of the national database.

Data quality

Data quality improved dramatically, thanks to increased use of quality checks (for timeliness, correctness, consistency and completeness of data) at the facility level, use of computer checks by districts and practical experience gained under supervision during workshops. Mistakes were identified by participants when data were presented during workshops, sometimes leading to heated discussion of quality issues, which made a strong impression on participants.

Data analysis and interpretation

At the start of the process, most district health management team staff did not think in terms of indicators, and their presentations focused on raw data. As information officers and programme managers became more competent in using the HMIS, data analysis tools (targets and indicators) became more widely used and understood, which strengthened self-assessment and “epidemiological thinking”. The link between plans, targets and indicators was emphasized, which helped to increase the use of indicators at local levels and the analysis of coverage and quality of service delivery. Fig. 1 shows a screenshot of the DHIS dashboard displaying analytical graphs. Some examples of improved local information use are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Examples of improved information use resulting from project for strengthening the Health Management Information System (HMIS) in Zanzibar, the United Republic of Tanzania, 2005–2008.

| Health entity | Examples of improved information use |

|---|---|

| RCH Unit | – Development of indicators to monitor emergency obstetric and neonatal care availability – Monitoring of quality of antenatal care and skilled birth attendance coverage – Introduction of maternal death audits – Introduction of the “couple year protection rate” indicatora – Improved anaemia diagnosis in pregnancy |

| Malaria Programme | – Increased emphasis on bed net coverage – Monitoring of malaria in pregnancy – Treatment of confirmed rather than clinical cases, which in some instances resulted in data showing lower malaria incidence |

| Expanded Programme on Immunization | – Investigation of high dropout rates and coverage over 100% – Identification of double counting, resulting in improved quality control mechanisms – Introduction of diagnostic criteria to reduce misdiagnosis of pneumonia and malaria |

| HIV/AIDS and STIs | – Reduction of excessive data categories and age groupings |

| Hospitals | – Routine collection of basic inpatient indicators such as average length of stay and bed occupancy rate – Focus on signal functions of emergency obstetric careb and referrals, not just reporting of complications – Inclusion of laboratory data to check quality of diagnosis, particularly of malaria, tuberculosis, anaemia and syphilis – Improvement of OPD reporting to gain a more comprehensive idea of district-wide disease burden by: (i) using data elements identical to PHC units, enabling meaningful comparisons with peripheral health centres and encouraging back-referrals; and (ii) streamlining specialist OPD clinic data and adding it to the national database – Development of workload indicators to rationalize staffing needs and advocate for redistribution of staff away from central hospitals |

AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; OPD, outpatient department; PHC, primary health care; RCH, reproductive and child health; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

a The rate at which couples (specifically women) are protected against pregnancy using modern contraceptive methods.12

b Key medical interventions that are used to treat the direct obstetric complications that cause most of maternal deaths around the globe. The signal functions are indicators of the level of care being provided.13

Problem-solving skills

District health management team members honed their ability to solve problems using HMIS data as they gained greater appreciation of the value of improved data quality and felt more competent to perform HMIS tasks and apply epidemiological approaches to daily data management issues.

Team work

Team work improved considerably as the district health management teams shared information about service delivery and used the HMIS to monitor and evaluate progress towards targets set in their district annual plans. Leaders became more confident in making evidence-based decisions to improve quality of care based on collective values developed through the data-use workshops. While a “culture of information” was not fully established, significant strides were made in that direction.

Practical computer skills

Workshop participants improved their computer skills in using DHIS for analysis, presentation and dissemination and also enhanced their knowledge of basic hardware and software maintenance, virus protection and backups. Software developers benefited from insights into new requirements and gained a better understanding of weaknesses related to local context and configuration.

Presentation skills

DHMT members’ presentation skills were initially weak, as they were unused to drawing graphs, using PowerPoint, engaging in debate or offering constructive criticism. These skills improved dramatically as a result of the workshops, especially when standardized templates for presentations were developed. Local HMIS Unit and health zone personnel acquired sufficient skills to run the workshops without outside facilitators. Box 1 summarizes the lessons learnt from this experience.

Box 1. Summary of main lessons learnt.

The outcomes of the data-use workshops demonstrate and validate our hypothesis that the more data are used, the more data quality will improve, leading to significant innovations in the use of information and breaking the vicious cycle of non-use and poor quality of data.

An integrated framework for HMIS, using a national data warehouse framework, provides an enabling environment in which actors, health programmes and systems can “speak to each other”, which is the foundation for improving health systems.

Regular data-use workshops, with self-assessment and peer critique and discussion of the data presented, provide a powerful means of building a strong evidence base for HMIS improvements.

HMIS, Health Management Information System.

Conclusion

The data-use workshops approach developed in Zanzibar helped to strengthen the United Republic of Tanzania’s HMIS and thereby its overall health system, providing a concrete example of health information systems strengthening. The approach has been applied in other countries, such as in Kenya and Rwanda, where it has become an institutionalized part of quarterly review processes.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.AbouZahr C, Boerma T. Health information systems: the foundations of public health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:578–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mavimbe JC, Braa J, Bjune G. Assessing immunization data quality from routine reports in Mozambique. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sæbø J, Kossi E, Hodne Titlestad O, Rolland Tohouri R, Braa J. Comparing strategies to integrate health information systems following a data warehouse approach in four countries. Info Technol Develop. 2011;17:42–60. doi: 10.1080/02681102.2010.511702. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braa J, Hanseth O, Heywood A, Mohammed W, Shaw V. Developing health information systems in developing countries: the flexible standards strategy. MIS Quart. 2007;31:381–402. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heeks R. Failure, success and improvisation of information systems projects in developing countries. Inf Soc. 2002;18:101–12. doi: 10.1080/01972240290075039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aqil A, Lippeveld T, Hozumi D. PRISM framework: a paradigm shift for designing, strengthening and evaluating routine health information systems. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24:217–28. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czp010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimaro HC, Nhampossa JL. Analyzing the problem of unsustainable health information systems in less-developed economies: case study from Tanzania and Mozambique. Info Technol Develop. 2005;11:273–98. doi: 10.1002/itdj.20016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Health Metrics Network [Internet]. Framework and standards for country health information systems 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthmetrics/documents/framework/en/index.html [accessed 10 February 2012].

- 9.Braa J. A data warehouse approach can manage multiple data sets. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:638–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheik YH, Titlestad OH. Implementing health information systems in Zanzibar: using internet for communication, information sharing and learning. In: Proceedings of the IST-Africa 2008 Conference and exhibition; 2008 May 7–9; Windhoek, Namibia. [Google Scholar]

- 11.District Health Information Software 2 [Internet]. Oslo: Health Information Systems Programme; 2012. Available from: http://www.hisp.uio.no/ [accessed 15 March 2012].

- 12.Couple year protection rate [Internet]. Oslo: Health Information Systems Programme; 2012. Available at: http://indicators.hst.org.za/healthstats/231/data [accessed 15 March 2012].

- 13.Monitoring emergency obstetric care: a handbook Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/shared/documents/publications/2009/obstetric_monitoring.pdf [accessed 15 March 2012].