Abstract

The Escherichia coli biotin repressor binds to the biotin operator to repress transcription of the biotin biosynthetic operon. In this work, a structure determined by x-ray crystallography of a complex of the repressor bound to biotin, which also functions as an activator of DNA binding by the biotin repressor (BirA), is described. In contrast to the monomeric aporepressor, the complex is dimeric with an interface composed in part of an extended β-sheet. Model building, coupled with biochemical data, suggests that this is the dimeric form of BirA that binds DNA. Segments of three surface loops that are disordered in the aporepressor structure are located in the interface region of the dimer and exhibit greater order than was observed in the aporepressor structure. The results suggest that the corepressor of BirA causes a disorder-to-order transition that is a prerequisite to repressor dimerization and DNA binding.

The biotin repressor, BirA, is a critical protein in regulation of biotin retention and biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Biotin is retained in the cell as a coenzyme that is covalently linked to biotin-dependent carboxylases (1). In E. coli this two-step reaction is catalyzed by BirA. The adenylate of biotin is first synthesized from substrates biotin and ATP (2). In the second step the biotin moiety is transferred to a unique lysine residue on the biotin carboxyl carrier protein (BCCP) subunit of acetyl-CoA carboxylase. The BirA⋅bio-5′-AMP complex also represses transcription initiation at the biotin biosynthetic operon by binding to the biotin operator (bioO) (3, 4). In this system the small molecule, bio-5′-AMP, functions both as the essential intermediate in the biotin transfer reaction and as the corepressor in repression of transcription at the biotin biosynthetic operon (Fig. 1; ref. 5). Two holoBirA (BirA⋅bio-5′-AMP) monomers bind cooperatively to the biotin operator, a process in which bio-5′-AMP activates BirA for DNA binding by promoting its homodimerization (6, 7). The adenylate is thus an allosteric activator in binding of BirA to DNA.

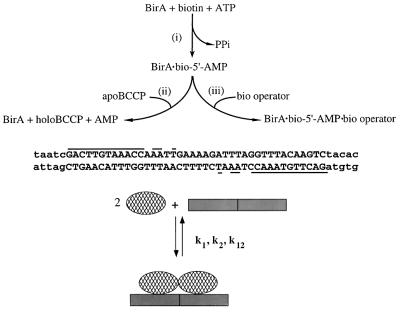

Figure 1.

Key elements of the biotin regulatory system. As illustrated at the Top, the biotin repressor, BirA, (i) catalyzes synthesis of bio-5′-AMP from biotin and ATP, (ii) catalyzes transfer of biotin from bio-5′-AMP to the biotin carboxyl carrier protein subunit (apoBCCP) of acetyl coA carboxylase, and (iii) binds to bioO in its holoform, BirA⋅bio-5′-AMP. The sequence of the biotin operator is shown in the Middle with elements that are conserved in the two half-sites underlined. As illustrated at the Bottom, two holoBirA monomers associate with the operator. The binding is cooperative and is governed by three microscopic parameters, k1 and k2, the two intrinsic constants for binding of a monomer to the two half-sites, and k12, the equilibrium association constant governing the cooperative interaction between the two monomers.

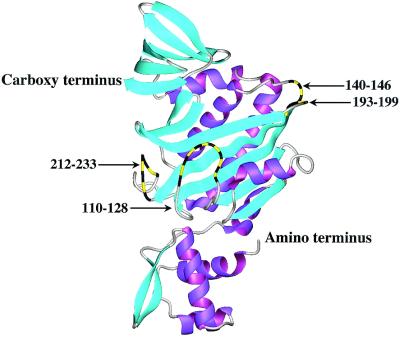

A three-dimensional structure of apoBirA has been determined by x-ray crystallography (8, 9). The 33.5-kDa polypeptide chain folds into three domains: the N-terminal DNA binding domain, the central domain, which functions both in catalysis and DNA binding, and the C-terminal domain (Fig. 2). Within the central domain there are five surface loops, four of which are partially disordered in the aporepressor structure. Protein footprinting measurements (10), as well as studies of single-site mutants, suggest that four of these loops are involved in biotin and bio-5′-AMP binding as well as DNA binding and dimerization of holoBirA (11, 12). The structural details, however, are not known.

Figure 2.

Model of the three-dimensional structure of monomeric apoBirA determined by x-ray crystallography (9). The four partially disordered surface loops of the central domain are highlighted. The model was generated by using the graphics program MOLMOL (37) with the Protein Data Bank file 1BIB as input.

In this work a structure of the BirA⋅biotin complex determined by x-ray crystallography is reported. Although biotin is not the physiological corepressor, it can act as an allosteric activator of bioO binding by BirA. Comparison of the apoBirA and BirA⋅biotin complex structures illustrates how conformational changes in BirA lead to the dimerization required for tight DNA binding. The structural data, together with mutational, biochemical and biophysical studies, suggest that the allosteric activator function of bio-5′-AMP reflects its ability to induce disorder-to-order transitions in multiple segments of BirA. These folding events are prerequisites to the dimerization required for tight binding of holoBirA to bioO.

Methods

Chemicals and Biochemicals.

All chemicals used in preparation of buffers were at least reagent or analytical grade. The d-biotin was purchased from Sigma. Bio-5′-AMP was synthesized and purified by using a modification of the procedure described in Lane et al. (2, 6).

Crystallization of BirA⋅Biotin.

The d-biotin solution was prepared in 100 mM phosphate buffer (100 mM NaH2PO4/K2HPO4, pH 6.5/5% glycerol). BirA in storage buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl/200 mM KCl/5% glycerol, pH 7.5 at 4°C) was slowly exchanged into 100 mM phosphate buffer by using a Centricon-10 (Amicon) concentrator. After concentrating the protein to a volume less than 100 μl, 2 ml of concentrated biotin (≈1 mM) solution was added to saturate the BirA. The BirA⋅biotin solution was concentrated to ≈24 mg/ml. Crystallization was performed by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method in HR3–110 Linbro boxes (Hampton Research, Riverside, CA). Each crystallization drop containing a mixture of 2 μl of 24 mg/ml BirA⋅biotin and 2 μl of 2.3 M phosphate buffer (NaH2PO4/K2HPO4, pH 6.5) was applied to a silanized glass cover, which was placed over a reservoir containing 1 ml of the same buffer. The cover glass was sealed with a Vaseline and mineral oil mixture, and crystals grew reproducibly in one month at 4°C.

Biochemical Analysis of the BirA⋅Biotin Crystals.

The presence of biotin in the crystals was determined by using a biochemical assay for synthesis of bio-5′-AMP from biotin and ATP (13). A crystal was carefully removed from mother liquor and dissolved into storage buffer. The approximate protein concentration in the solution was determined by subjecting samples to SDS/PAGE alongside standard known quantities of BirA. Densitometry of the coomassie brilliant blue stained gel allowed for estimation of the protein concentration in the original solution. The putative BirA⋅biotin complex was then combined with α-[32P]ATP to initiate synthesis of bio-5′-32P-AMP. The reaction was quenched by addition of excess unlabeled bio-5′-AMP and products were separated by TLC on cellulose plates. Phosphorimaging of the plate revealed the presence of biotinyl-5′-AMP and quantitation of the images revealed the presence of a burst complex in a 1:1 stoichiometry. This result provided evidence that the crystals contained biotin in addition to BirA.

Crystal Structure of the BirA⋅Biotin Complex.

Data were collected by using a Xuong–Hamlin area detector (ref. 14; Table 1). The asymmetric unit of the orthorhombic cell contains two independent copies (A and B) of the BirA⋅biotin complex, the positions of which were located by a rotation–translation search (15) using the apoBirA model (9) as the search motif. The local, noncrystallographic, symmetry relating monomers A and B is an approximate 41 screw operation with the axis nearly parallel to the z axis of the cell. As discussed in more detail under Results and Discussion, monomers A and B form two crystallographically distinct dimers of the form AA′ and BB′. Overall, the crystal structure has pseudo symmetry P41212.

Table 1.

X-ray data collection and refinement statistics

| Space group | C2221 |

| Unit cell dimensions (Å) | 104.9, 108.9, 143.2 |

| Maximum resolution (Å) | 2.4 |

| Completeness (%) | 83 (33) |

| I/σ(I) (overall) | 9.0 (1.8) |

| Rsym (%) | 7.1 (18.3) |

| Refinement resolution (Å) | 13.0–2.4 |

| Reflections | 26762 |

| Monomers/asymmetric unit | 2 |

| Protein atoms | 4712 |

| Solvent atoms (water) | 59 |

| Ligand atoms (biotin) | 32 |

| R (%) | 18.9 |

| Δbonds (Å) | 0.018 |

| Δangles (°) | 2.8 |

Rsym gives the agreement between repeated measurements of equivalent reflections. R is the crystallographic R-factor for the refined model. Rfree was not calculated because it would be susceptible to bias due to the noncrystallographic symmetry. Values given in parentheses correspond to the highest-resolution shell of data.

Refinement of the model by using TNT (16), initially as rigid bodies and subsequently with tight restraints on geometry and thermal factors, quickly reduced the crystallographic R-factor to about 25%. The model was judged essentially correct at this stage when a difference electron density map clearly showed density for biotin and for several protein residues that had not yet been included in the model. Further refinement led to the statistics given in Table 1.

Structure Analysis.

Structure analysis and comparison was carried out with the program edpdb (17). The same program was also used with a probe of radius 1.4 Å to calculate solvent-accessible surface area.

Results and Discussion

BirA Is a Dimer in Its Complex with Biotin.

Other than the addition of biotin, and the use of 4°C rather than room temperature, the crystallization conditions used for BirA⋅biotin are similar to those used for the apoBirA crystals.

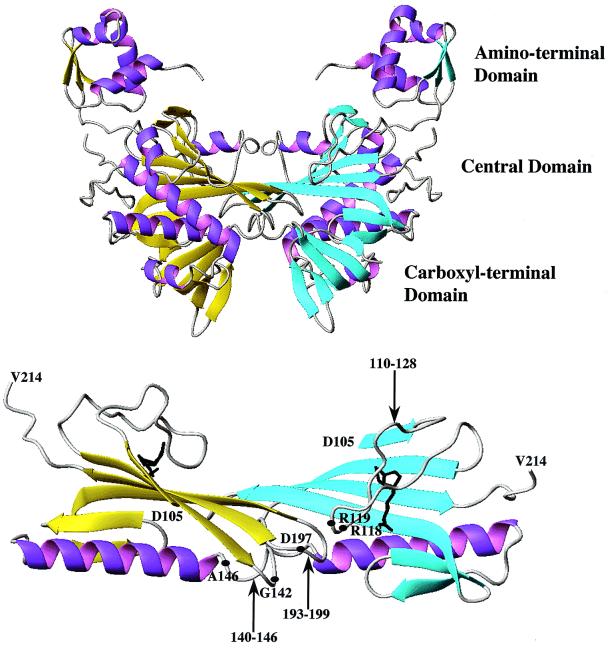

The asymmetric unit of the BirA⋅biotin crystals contains two monomers that are identified as A and B. In a somewhat unusual arrangement, the A and B monomers form two very similar but crystallographically distinct dimers (Fig. 3 Upper). One dimer is of the form AA′, where monomers A and A′ are identical to each other and are related by a crystallographic 2-fold axis. The second dimer is of the form BB′, where B and B′ are identical and are related by a different crystallographic 2-fold axis. The AA′ and BB′ dimers, which contact each other, are very similar but not identical. The observation that this dimer occurs twice in a crystallographically independent fashion strongly suggests that it occurs in solution before crystallization and is therefore biologically relevant. In forming the dimer interface, each monomer buries 920 Å2 of solvent-accessible surface area. This surface area burial is somewhat on the low side for monomer chains of 30–40 kDa, consistent with the dimerization being relatively weak (7). The value of 920 Å2 is, however, within the overall range of 690-4880 Å2 observed for tabulated dimeric proteins (18). Thus, a major difference between this structure and that of apoBirA is the dimeric state of the complex. In the previously studied crystal form (9), all of the interactions between the monomers were consistent only with crystal contacts.

Figure 3.

(Upper) Model of the three-dimensional structure of the BirA⋅biotin dimer. For clarity the biotin ligand is not shown. The β-strands of the two monomers are shown in yellow and cyan. (Lower) The dimerization interface illustrating the extended β-sheet that forms between the two monomers. The biotin ligands are shown in black, and the locations of the loops in the interface, as well as the positions of residues at which mutations result in defects in repression (Table 2), are indicated. The models were generated by using MOLMOL (37).

The derivative of biotin, bio-5′-AMP, is the physiological corepressor. Although it has been suggested that biotin binding can also activate DNA binding by BirA (19), previously published results of sedimentation equilibrium measurements of BirA indicate that the binding of bio-5′-AMP, not biotin, is coupled to dimerization of the repressor (7). These observations made it desirable to test the biological relevance of the interface observed in the present structure. To do so, the function of biotin in promoting DNA binding was measured by DNaseI footprinting. These measurements indicate that the BirA⋅biotin complex binds to bioO with affinity intermediate between that of apoBirA and BirA⋅bio-5′-AMP (data not shown). The data indicate that, although binding of the adenylate to BirA enhances the free energy of the protein–DNA interaction by 5 kcal/mole, biotin binding enhances it by only 3 kcal/mole. Assuming that the enhancement of affinity of BirA for bioO associated with binding of either bio-5′-AMP or biotin reflects only the activities of these ligands in promoting protein dimerization, the equilibrium dissociation constant, KD, for dimerization of the biotin complex of BirA can be estimated. Based on the known value of the Gibbs free energy for dimerization of holoBirA of −6.7 kcal/mole, the dimerization free energy for formation of the BirA⋅biotin complex is estimated to be −4.7 kcal/mole. This corresponds to a KD at 20°C of 3 × 10−4 M, a dissociation constant too weak to detect in the previously reported sedimentation experiments because of the limited protein concentrations used. From the point of view of crystal growth, however, the concentration of BirA is very high and under these conditions the addition of biotin led to the dimeric form seen in the present structural analysis. The fact that biotin can serve as an allosteric effector of binding of BirA to bioO supports the conclusion that the interface observed in this structure is relevant to that formed in the holoBirA⋅bioO complex.

The details of the dimerization interface are shown in Fig. 3 Lower. In the dimer structure the β-sheets in the central domain of each monomer are arranged side by side, forming a single, seamless β-sheet. At the region of contact, residues 188–195 of one subunit form an extended β-sheet strand that is hydrogen-bonded to the identical residues in the neighboring monomer. The three loops, consisting of amino acid residues 110–128, 140–146, and 193–199, which are partially disordered in the apoBirA structure, are located in the dimerization interface. Amino acid residues R118, R119, G142, and D197 appear to be directly involved in the interactions between two BirA monomers.

Comparison of the Structures of ApoBirA and BirA⋅Biotin Monomers.

To understand the conformational changes in BirA that occur on binding of the biotin ligand it is useful to compare the structures of the monomers of apoBirA and the BirA⋅biotin complex. The overall backbone structures of the two proteins are very similar. Superposition of the monomeric apoBirA structure on one of the subunits (subunit B) from the BirA⋅biotin crystal structure yielded root-mean-square discrepancies between α-carbon atoms of 1.23 Å, 0.89 Å, 0.79 Å, and 1.26 Å for the N-terminal domain, the central domain, the C-terminal domain, and the entire molecule, respectively. For comparison, the corresponding discrepancies between the two subunits (A and B) of the BirA⋅biotin crystal structure were 0.52 Å, 0.46 Å, 0.79 Å, and 0.76 Å.

The main differences between the apoBirA and BirA⋅biotin complexes are localized to the regions of loops 110–128, 140–146, and 193–199 (Figs. 2b and 3 Lower). In the apoBirA structure (9), residues within these loops ranged from partially to completely disordered. In contrast, in the BirA⋅biotin complex, all of the residues in the three loops are visible. Only the loop composed of residues 212–234 remains disordered in the co-crystal structure. It might be noted, however, that this loop has been shown to be protected from proteolytic digestion and hydroxyl–radical-mediated cleavage of the backbone as a consequence of biotin or bio-5′-AMP binding (10, 20). The extent of protection is greater with adenylate binding. These previous results suggest that in the adenylate-bound form of the repressor the 212–234 loop may be more ordered than in the present crystal structure.

Location of Biotin in the Complex and Its Interactions with BirA.

Structures of monomeric BirA bound to the biotin analogs, biotinyl-lysine and biotin methyl ester, were previously obtained by soaking the analogs into pregrown crystals of apoBirA (9). The crystals were, however, destroyed on exposure to biotin, suggesting that a conformational change had occurred. Biotinyl-lysine (biocytin) is a mimic of the overall product of the biotin transfer reaction and binding studies indicate that it interacts very weakly with BirA (D.B., unpublished results). When biocytin was added to the crystals described by Wilson et al. (9) it caused residues 116–118 to become ordered. This ordering could be attributed to interactions between these residues and the biotin ring system. In the present crystals, grown in a different crystal form in the presence of biotin, the complete loop encompassing residues 110–128 becomes ordered and largely encloses the cofactor (Fig. 4 a and b). The same hydrogen-bonding interactions between the protein and biotin observed by Wilson et al. (9) are also seen in the present complex (Fig. 4b). In addition, the backbone amide of Arg-118 hydrogen-bonds the carboxylate of the valerate chain. Among many other interactions that appear to stabilize the 110–128 loop, the indole of Trp-123 stacks against the hydrocarbon part of the valerate moiety (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4.

(a) Stereo drawing showing the overall environment of the biotin-binding site. The loop that encompasses residues 110–128 becomes ordered on binding biotin and is shown with open pseudobonds. In general only the backbone of the protein is shown although side chains are included for those residues listed in Table 2 as the sites of mutations that are defective in enzymatic function. (b) Stereo drawing showing the detailed environment of the bound biotin. Hydrogen bonds are drawn as dashed lines. (There is also a hydrogen bond, not easily visible, between the backbone amide of Arg-116 and the ureido oxygen of the biotin.)

Biochemical studies of mutants also indicate a direct involvement of the 110–128 loop in biotin and bio-5′-AMP binding via residues G115 and R118 (11). Therefore, it is likely that this loop folds before dimerization. The other two loops (140–146 and 193–199) do not appear to be directly involved in small ligand binding, and it is possible that their ordering requires simultaneous formation of the dimerization interface.

Relationship of the Structure of the BirA⋅Biotin Complex to Genetic and Biochemical Studies of Single-Site Mutants.

The structure of the BirA⋅biotin complex can be related to studies of BirA mutants. Mutants that confer a requirement for biotin that is higher than normal are summarized in Table 2 (3, 4, 21, 22). As shown in Figs. 3 Lower and 4a, the sites of most of these mutations are in the vicinity of the bound biotin, although not necessarily in direct contact. The thermodynamic effects of the mutations at residues G115 and R118 on biotin binding have recently been measured and found to be 3.7 and 2.2 kcal/mole, respectively (11). Residue 115 is a glycine, and the substitution of a serine side chain at this position would introduce a steric clash with the ureido moiety. The arginine at position 118 interacts via its backbone nitrogen with the carboxylate of the valerate chain of biotin. This interaction appears to be stabilized by a salt bridge between the guanidinium group of Arg-118 and the carboxylate of Asp-176 (Fig. 4b). The arginine side chain does not, however, interact directly with the biotin.

Table 2.

Characteristics of BirA mutants that are defective in repression or enzymatic function

| Allele | Biotin requirement (μM) | Repression (1 mM biotin) | Mutation position | Amino acid substitution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| birA (wt) | <4.1 (43°C) | + | — | — |

| birA879 | 1.6–41 (29°C) | − | 83 | Val → Gly |

| birA815 | 41–4,100 (43°C) | + | 107 | Cys → Gly |

| birA1 | 41–4,100 (43°C) | + | 115 | Gly → Ser |

| birA91 | 4.1–41 (43°C) | − | 118 | Arg → Gly |

| birA352 | <4.1 (43°C) | − | 119 | Arg → Trp |

| birA71 | 1.6–41 (29°C) | − | 142 | Gly → Cys |

| birA881 | <4.1 (43°C) | − | 146 | Ala deleted |

| birA215 | 41–4,100 (43°C) | + | 189 | Val → Gly |

| birA301 | <4.1 (43°C) | − | 197 | Asp → Tyr |

| birA104 | 41–4,100 (29°C) | + | 207 | Ile → Ser |

| birA85 | 41–4,100 (29°C) | − | 235 | Arg → Gly |

The structure of the dimerization interface can also be related to data obtained on single-site mutants of BirA, which disrupt repression of transcription initiation at the biotin operon control region. The majority of such mutants (Table 2) are located in the three surface loops that are partially disordered in the aporepressor structure (Fig. 3 Lower), the sole exception being the mutation at amino acid residue 235. In the BirA⋅biotin complex, Arg-235 makes a well ordered and apparently strong salt bridge with Glu-110 at the beginning of the 110–128 loop. Moreover, Gln-112, two residues away, is a biotin contact residue. Thus, it is not surprising that the Arg-235 Gly mutation is defective in repression. The three loops in which the repression-defective mutations are found are also located in the dimerization interface in the structure of the BirA⋅biotin complex. Four of these mutants, A146Δ, D197Y, R118G, and R119W, have been shown to be defective in both dimerization and DNA binding (12).

Binding of the HoloBirA Dimer to BioO.

Two holoBirA monomers bind to the 40-bp biotin operator sequence (6). Results of enzymatic and chemical probing of the protein⋅DNA complex are consistent with a structural model in which each DNA binding domain of the holoBirA dimer contacts one of the two 12-bp sequences at the termini of the operator sequence (23). As indicated in Fig. 1, these two sequences form a perfect interrupted inverted palindrome in the operator. In the BirA⋅biotin dimer the Cα-Cα distance between residues within the DNA “recognition” helices (9) in the respective amino-terminal domains ranges from about 55 Å to 65 Å. For Ser-32, Arg-33, and Ala-34, which are within the recognition helix and presumably contact the DNA (22), the Cα-Cα distance is about 65 Å. This corresponds to a little less than two turns of straight B-form DNA. The distance between the “wing-tips” of the winged helix–turn–helix motifs is about 80–85 Å, which corresponds to about 24 base pairs of B-form DNA. By using model building, it is possible to align the model for the BirA⋅biotin dimer on straight B-form DNA so that the amino-terminal ends of the recognition helices (i.e., residues 32–34) are located within the major groove and the “wings” also make contacts with the operator (Fig. 5). However, the region of contact between the protein and the DNA does not include the more distal parts of the 40-bp site suggested by enzymatic and chemical footprinting (23). Additional contacts within the outermost part of the operator would occur if the DNA were bent around the protein as observed for cAMP-binding protein (CAP; ref. 24) and a number of other protein⋅DNA complexes. Indeed, DNaseI footprinting studies of the complex, as well as circular permutation studies, are consistent with distortion of the DNA as a consequence of holoBirA binding (23). Although the results of circular permutation measurements indicate a net deviation of the complexed bioO DNA from linearity of 40°, DNaseI hypersensitivity is observed at three loci in the operator sequence. Two of the hypersensitive sites are located in each of the 12-bp termini that contact each holoBirA monomer and the third is in the sequence adjacent to the A-tract that constitutes the core of the operator sequence. Thus, the model shown in Fig. 5 is intended to illustrate that the BirA⋅biotin dimer is, with high probability, the DNA-binding form of the repressor. At the same time, it is to be understood that in the actual complex the DNA may be bent and the protein may undergo some change in conformation.

Figure 5.

Drawing illustrating the BirA dimer aligned next to straight DNA. The protein structure corresponds to the BirA⋅biotin dimer as seen in the present crystal structure. β-sheet strands are colored green and α-helices are blue except for the helix–turn–helix motif (residues 22–46), which is colored yellow. The DNA is straight, B-form, and includes 40 base pairs, the overall length of the biotin operator. As noted in the text, in the actual birA-operator complex the DNA is presumably bent or otherwise deformed, and the protein may also undergo conformational change. The figure was drawn by using MOLSCRIPT (38) with the kind help of Doug Juers.

Model of the Allosteric Mechanism in BirA.

Thermodynamic measurements of DNA binding indicate that two holoBirA monomers bind cooperatively to the biotin operator sequence (6). Binding of holoBirA to operator templates in which one of the wild-type half-sites is replaced by nonspecific sequence is also cooperative (25). This indicates that the thermodynamic interaction of two monomers in the DNA binding process is an obligatory feature of this system. Studies of the self-assembly of BirA indicate that corepressor binding promotes weak dimerization of the protein (7). However, because the dimerization process is weak it does not occur before DNA binding, but on the DNA surface. The cooperativity measured for bioO binding reflects, in part, the formation of this protein–protein interface concomitant with DNA binding. The data described in this work provide the structural basis of the enhancement of dimerization energetics as a consequence of bio-5′-AMP binding. Binding of the effector to BirA results in disorder-to-order transitions in the flexible surface loops of the central domain. Ordering of these loops in the holorepressor results in more favorable energetics of dimerization, presumably because of lowering of the entropic cost of formation of the protein–protein interface. This increased stability of the dimer interface contributes favorably to the energetics of assembly of the protein⋅DNA complex.

Relationship to Allosteric Mechanisms in Other Transcriptional Repressors.

In general, allosteric DNA binding proteins belong to two classes with respect to the mode of action of the allosteric effector. In one class the corepressor or inducer binds to a preformed oligomer to alter its affinity for DNA; in the second the small molecule effector acts by modulating the assembly properties of the protein. The purine, lactose, tryptophan, and tetracycline repressors from E. coli belong to the first class (26–30), whereas the tyrosine, arginine, and diptheria toxin repressors belong to the second (31–33). In the first class, the binding of effector typically induces shifting of the positions of the DNA binding domains. The effector-induced conformation of the DNA binding domains can be either more (corepressor) or less (inducer) favorable for interaction with the grooves of the DNA target (26–30). The structural details for the second class of regulatory protein have not previously been delineated. For example, although structures of the apo- and holo- or metal-bound forms of the diptheria toxin repressor are known (34, 35), these structures provide little insight into the mechanism of effector-induced dimerization of this protein (31). Precedence for effector-induced oligomerization is, however, provided by glycerol kinase. In this case the allosteric regulator fructose 1,6-bisphosphate modulates enzymatic activity by binding at a subunit interface and promoting the conversion from dimers, which are fully active, to tetramers, which have substantially reduced activity (36). The biotin repressor system provides the first example of a transcriptional repressor in which both the thermodynamic and structural details of corepressor-induced assembly have been determined.

Model building suggests that the same surface of BirA that is shown here to be used for homotypic interaction may also be used for heterotypic interaction with apoBCCP (Fig. 1; L.H.W., D.B., and B.W.M., manuscript in preparation).

Acknowledgments

D.B. and K.K. thank Drs. Eaton Lattman and Apo Gittis for patient instruction in the art of protein crystallization. We all thank Dr. Doug Juers for help in the preparation of figures. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM46511 (to D.B.) and GM20066 (to B.W.M.).

Abbreviation

- BirA

biotin repressor

- bioO

biotin operator

Footnotes

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org [PDB ID code 1HXD (BirA⋅biotin)].

References

- 1.Cronan J E., Jr Cell. 1989;58:427–429. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90421-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lane M D, Rominger K L, Young D L, Lynen F. J Biol Chem. 1964;239:2865–2871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barker D F, Campbell A M. J Mol Biol. 1981;146:451–467. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker D F, Campbell A M. J Mol Biol. 1981;146:469–492. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prakash O, Eisenberg M A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:5592–5595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.11.5592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbott J, Beckett D. Biochemistry. 1993;32:9649–9656. doi: 10.1021/bi00088a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisenstein E, Beckett D. Biochemistry. 1999;38:13077–13084. doi: 10.1021/bi991241q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brennan R G, Vasu S, Matthews B W, Otsuka A J. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson K S, Shewchuk L M, Brennan R G, Otsuka A J, Matthews B W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9257–9261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.9257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Streaker E D, Beckett D. J Mol Biol. 1999;292:619–632. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kwon K H, Beckett D. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1530–1539. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.8.1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon K H, Streaker E D, Ruparelia S, Beckett D. J Mol Biol. 2000;304:821–833. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Y, Beckett D. Biochemistry. 1994;33:7354–7360. doi: 10.1021/bi00189a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamlin R. Methods Enzymol. 1985;114:416–452. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(85)14029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X-J, Matthews B W. Acta Crystallogr. 1994;D50:675–686. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994002295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tronrud D E, Ten Eyck L F, Matthews B W. Acta Crystallogr. 1987;A43:489–501. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang X-J, Matthews B W. J Appl Crystallogr. 1995;28:624–630. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller S, Lesk A M, Janin J, Chothia C. Nature (London) 1987;328:834–836. doi: 10.1038/328834a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisenberg M A, Prakash O, Hsiung S C. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:15167–15171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu Y, Nenortas E, Beckett D. Biochemistry. 1995;34:16624–16631. doi: 10.1021/bi00051a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howard P K, Shaw J, Otsuka A J. Gene. 1985;35:321–331. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buoncristiani M R, Howard P K, Otsuka A J. Gene. 1986;44:255–261. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Streaker E D, Beckett D. J Mol Biol. 1998;278:787–800. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schultz S C, Shields G C, Steitz T A. Science. 1991;253:1001–1007. doi: 10.1126/science.1653449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Streaker E D, Beckett D. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3210–3219. doi: 10.1021/bi9715019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schumacher M A, Choi K Y, Zalkin H, Brennan R G. Science. 1994;266:763–770. doi: 10.1126/science.7973627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schumacher M A, Choi K Y, Lu F, Zalkin H, Brennan R G. Cell. 1995;83:147–155. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90243-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bell C E, Lewis M. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:209–214. doi: 10.1038/73317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang R-G, Joachimiak A, Lawson C L, Shevitz R W, Otwinowski Z, Sigler P B. Nature (London) 1987;327:591–597. doi: 10.1038/327591a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orth P, Schnappinger D, Hillen W, Saenger W, Hinrichs W. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:215–219. doi: 10.1038/73324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tao X, Zeng H Y, Murphy J R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6803–6807. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.6803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Duyne G D, Ghosh G, Maas W K, Sigler P B. J Mol Biol. 1996;256:377–391. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bailey M F, Davidson B E, Minton A P, Sawyer W H, Howlett G J. J Mol Biol. 1996;263:671–684. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schiering N, Tao X, Zeng H, Murphy J R, Petsko G A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9843–9850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White A, Ding X, Vanderspek J C, Murphy J R, Ringe D. Nature (London) 1998;394:502–506. doi: 10.1038/28893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ormö M, Bystrom C E, Remington S J. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16565–16572. doi: 10.1021/bi981616s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wüthrich K. J Mol Graphics. 1996;14:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kraulis P J. J Appl Crystallogr. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]