Abstract

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) have important immunomodulatory properties, they inhibit T lymphocyte allo-activation and have been used to treat graft-versus-host disease. How MSC exert their immunosuppressive functions is not completely understood but species specific mechanisms have been implicated. In this study we have investigated the mechanisms for rat MSC mediated inhibition of T lymphocyte proliferation and secretion of inflammatory cytokines in response to allogeneic and mitogenic stimuli in vitro. MSC inhibited the proliferation of T cells in allogeneic mixed lymphocyte reactions and in response to mitogen with similar efficacy. The anti-proliferative effect was mediated by the induced expression of nitric oxide (NO) synthase and production of NO by MSC. This pathway was required and sufficient to fully suppress lymphocyte proliferation and depended on proximity of MSC and target cells. Expression of inducible NO synthase by MSC was induced through synergistic stimulation with tumor necrosis factor α and interferon γ secreted by activated lymphocytes. Conversely, MSC had a pronounced inhibitory effect on the secretion of these cytokines by T cells which did not depend on NO synthase activity or cell contact, but was partially reversed by addition of the cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitor indomethacin. In conclusion, rat MSC use different mechanisms to inhibit proliferative and inflammatory responses of activated T cells. While proliferation is suppressed by production of NO, cytokine secretion appears to be impaired at least in part by COX-dependent production of prostaglandin E2.

Keywords: mesenchymal stem cells, immunosuppression, T lymphocyte activation, mixed lymphocyte reaction, nitric oxide synthase 2, cytokines, rodent, prostaglandin E2

Introduction

Mesenchymal stem cells have self-renewing capacity and differentiation potential for all mesodermal cell lineages (Pittenger et al., 1999). They are present within a heterogeneous cell population referred to as mesenchymal stromal cells (MSC) which are presently defined by a set of criteria based on their morphology, phenotype, and multipotency (Dominici et al., 2006). To date, MSC have been studied most thoroughly in humans and mice. They can be isolated from the bone marrow (BM) and a variety of other adult and fetal tissues (Pittenger et al., 1999; Zuk et al., 2001; in ’t Anker et al., 2003, 2004; da Silva Meirelles et al., 2006; Yoshimura et al., 2007). MSC have potent modulatory effects on immune cells including T cells, B cells, natural killer cells, and dendritic cells as well as regulatory T (Treg) cells (Uccelli et al., 2006; Nauta and Fibbe, 2007; Tolar et al., 2011). A range of distinct mediator molecules have been implicated (Uccelli et al., 2006; Nasef et al., 2008) but the molecular mechanisms by which MSC exert these effects are not entirely understood and the influences of tissue source, species origin, and cell culture conditions have yet to be firmly established.

Nitric oxide (NO) is a short-lived bioactive compound which is catalyzed by different tissue-specific NO synthases, of which inducible NO synthase (iNOS) encoded by the NOS2 gene is active in macrophages, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells (Bogdan, 2001; Lukacs-Kornek et al., 2011). iNOS expression can be induced by synergistic signals of interferon (IFN) γ and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α or Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands (Liew et al., 1991; Muñoz-Fernández et al., 1992; Deng et al., 1993; Lorsbach et al., 1993; Lukacs-Kornek et al., 2011). NO acts as a regulator of cellular and immune functions (Bogdan, 2001) such as inhibition of T cell responses (Lejeune et al., 1994; Medot-Pirenne et al., 1999; Niedbala et al., 2006) and induction of Treg cells (Niedbala et al., 2007). The iNOS pathway also has a role in the immunosuppressive potential of MSC (Sato et al., 2007). A combination of pro-inflammatory cytokines, namely IFNγ together with TNFα, interleukin (IL)1α, or IL1β, has been shown to trigger the expression of iNOS in murine BM-derived MSC (Ren et al., 2008). Mouse MSC (mMSC) utilize NO to arrest T cell proliferation and activation in vitro and in vivo (Oh et al., 2007; Sato et al., 2007; Ren et al., 2008).

The capacity of MSC to suppress the activation of T lymphocytes has become of interest for clinical prevention and treatment of both autoimmune diseases and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD; Dazzi and Krampera, 2011; Tolar et al., 2011). GVHD has been treated successfully with MSC infusions clinically (Le Blanc et al., 2004, 2008; Ringdén et al., 2006; Martin et al., 2010; Tolar et al., 2011) and experimentally in animal models (Yanez et al., 2006; Min et al., 2007; Tisato et al., 2007; Polchert et al., 2008; Tian et al., 2008; Joo et al., 2010). Ren et al. (2008) reported that amelioration of experimental GVHD by mMSC depended on NO production. Human MSC (hMSC), on the other hand, do not utilize NO conversion, but rather employ alternative signaling pathways such as indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 required for synthesis of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and heme oxygenase-1 expression to inhibit T cell activation and induce expansion of Treg cells (Meisel et al., 2004; Aggarwal and Pittenger, 2005; Ren et al., 2009; Mougiakakos et al., 2011).

It has been suggested that MSC are “licensed” by certain effector molecules to exert immunomodulatory functions (Dazzi and Krampera, 2011). When exposed to an inflammatory milieu, hMSC upregulated the expression of IDO and COX-2 genes and showed increased inhibitory potential in mixed lymphocyte reactions (MLR; Crop et al., 2010). In another recent paper, the immunomodulatory properties of rat MSC (rMSC) were primed by the addition of different cytokines resulting in either enhanced inhibition of proliferation or the opposite effect depending on the type of stimulatory signal (Renner et al., 2009).

In this report, we generated rMSC lines from the BM and evaluated their potential to inhibit T cell proliferation and cytokine secretion in vitro. We show that the regulation of immunosuppression by rMSC was more similar to mouse than to hMSC. rMSC depended on cell-to-cell contact, iNOS expression, and NO production to mediate potent anti-proliferative effects. The putative mechanism that inhibits secretion of inflammatory cytokines is distinct and does not depend on cellular contact but on a soluble factor, likely PGE2 produced by COX-2.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

Approval for the use of organs of rats euthanized with CO2 (license number: VIT09.1512) was obtained from our institutional veterinarian with delegated authority from the Norwegian Animal Research Authority under the Ministry of Agriculture of Norway. All experiments were conducted in compliance with institutional guidelines. All animals were sacrificed with CO2 and every effort was made to minimize their suffering.

Animal care

PVG strain rats express the c haplotype of the rat MHC (RT1c, i.e., RT1-Ac-B/Dc-CE/N/Mc; for short, c-c-c). PVG-RT7b strain (abbreviated PVG.7B) rats express the RT7.2 allotype of CD45, but are used interchangeably with the standard PVG strain (encoding the RT7.1 allotype) as both strains carry the RT1c haplotype. The MHC-congenic PVG-RT1u strain (PVG.1U) expresses the u-u-u MHC haplotype, the PVG-RT1n strain (PVG.1N) the n-n-n haplotype and the intra-MHC recombinant PVG-RT1r23 strain (PVG.R23) the u-a-av1 haplotype on the PVG background.

PVG.R23, PVG.1N, PVG.1U, and PVG.7B rats were bred at the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Oslo. PVG and BN/RijHsd (BN; RT1n, n-n-n) rats were purchased from Harlan, The Netherlands1. The animals were housed under a 12:12 h light/dark cycle with access to food and filtered drinking water ad libitum and were routinely screened for common pathogens following recommendations by the Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Associations (Nicklas et al., 2002).

Materials

Nylon cell strainers (70 μm mesh size) were purchased from BD Falcon, MA, USA2; GIBCO® RPMI medium 1640, OPTI-MEM® I, α-modified minimal essential medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin and streptomycin, sodium pyruvate, 2-mercaptoethanol, trypsin and EDTA, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly-I:C) from Invitrogen, UK3; l-glutamine, Immobilon®-P transfer membrane from Millipore, MA, USA4; biotin, Brefeldin A, Concanavalin A (ConA), sodium nitrate, sodium dodecyl sulfate, 2-mercaptoethanol, glycerol, sulfanilamide, N-(1-Naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride, 5(6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate n-succinimidyl ester (CFSE), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), propidium iodide, paraformaldehyde, saponin from Quillaja bark, 1-methyl-dl-tryptophan (1-MT), NG-monomethyl-l-arginine acetate (l-NMMA) from Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA5; indomethacin (IMC; Confortid®) from Dumex-Alpharma A/S, Denmark6; Criterion™ Precast gels from Bio-Rad Laboratories, CA, USA7; SuperSignal® West Pico chemiluminescent substrate from Thermo Scientific, IL, USA8; Amersham Hyperfilm™ ECL from GE Healthcare Ltd., UK9; culture flasks from Nunc, Denmark10; 96-well cell culture clusters, HTS Transwell® 96-well system with 0.4 μm polycarbonate membrane insert plates from Corning, NY, USA11; recombinant rat IFNγ from Biomedical Primate Research Centre, The Netherlands12; recombinant rat TNFα from PeproTech, UK13; [methyl-3H]-thymidine (3H-TTP) from Hartmann-Analytic, Germany14; MicroScint™ O solution from PerkinElmer, MA, USA15.

Antibodies

Monoclonal mouse anti-rat CD25 (OX39) and anti-CD3 (G4.18) antibodies were conjugated with biotin and anti-CD4 (W3/25) antibody with FITC in our laboratory using standard methods. Supernatants of monoclonal mouse anti-rat CD45 (OX1), anti-RT1-B/D (pan-MHC class II; OX6), anti-CD71 (OX26), anti-CD11b (OX42), anti-CD86 (OX48), anti-CD44 (OX49), anti-RT1-A (pan-MHC class I; OX18, purified) antibodies, as well as phycoerythrin-conjugated mouse anti-rat IFNγ (DB-1), anti-CD31 (TLD-3A12), anti-CD90 (OX7), anti-CD3 (G4.18), FITC-conjugated anti-CD59 (TH9) from BD Biosciences and allophycocyanin-conjugated rat anti-mouse/rat FoxP3 (FJK-16s) from eBioscience, CA, USA16 were used for immunostaining. Phycoerythrin-conjugated donkey anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Ig) G or peridinin chlorophyll protein-conjugated Streptavidin from BD Biosciences were used as secondary antibodies for flow cytometric analysis.

Polyclonal rabbit anti-rat TNFα, goat anti-rat IFNγ, and rabbit anti-rat IL6 antibodies were from PeproTech; polyclonal rabbit anti-rat NOS2 (M-19) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA17; monoclonal mouse anti-GAPDH (6C5) from Millipore; horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and goat anti-mouse IgG from Jackson ImmunoResearch, PA, USA18.

Cell lines

The rat macrophage cell line R2 is derived from pleural macrophages induced by a silica injection in the pleural cavity of Wistar rats (Damoiseaux et al., 1994). R2 cells were maintained in complete medium comprising RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U mL−1 penicillin, 100 μg mL−1 streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

MSC lines were obtained from 7- to 8-week-old female PVG.7B and PVG.1U rats as described elsewhere (Lennon and Caplan, 2006). In short, BM cells were aspirated from femurs and tibias, filtered through nylon cell strainers, and cultured in α-modified minimal essential medium supplemented with 20% FBS, 100 U mL−1 penicillin, 100 μg mL−1 streptomycin, and 2 mM l-glutamine in 175 cm2 culture flasks at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Non-adherent cells were removed after 24 h by replacement of culture medium with complete, antibiotics-free MSC medium comprising α-modified minimal essential medium supplemented with 15% FBS and 2 mM l-glutamine. Adherent cells were allowed to expand to near confluence, detached using 500 μg mL−1 trypsin and 200 μg mL−1 EDTA·4Na and reseeded at a density of approximately 400–600 cells cm−2. MSC were used in experiments after the third passage. Supernatants from confluent cultures were frequently controlled for mycoplasma contamination by PCR as previously described (Zinöcker et al., 2011b).

Cell culture

Mesenteric and cervical lymph nodes from 7- to 14-week-old male or female PVG, PVG.7B, PVG.1N, PVG.1U, PVG.R23, and BN rats were removed and filtered through nylon cell strainers. The lymphocyte population was purified by density gradient centrifugation using Lymphoprep™ 1.077 (Medinor AS, Norway)19. Stimulator cells were irradiated (2000 cGy) using a 137Cs source (Gammacell® 3000; MDS Nordion, ON, Canada)20 to inhibit mitosis. MLR were performed in a total volume of 200 μL complete MLR medium comprising RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U mL−1 penicillin, 100 μg mL−1 streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol using round bottom 96-well plates. Equal numbers (2 × 105) of responder and stimulator cells were mixed and incubated for 4 days at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. ConA was used at 5 μg mL−1 final concentration for mitogenic stimulation of 2 × 105 responder cells unless specified otherwise. MSC were harvested from culture, washed twice (500 g for 6 min) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), resuspended in MLR medium and seeded at least 2 h before lymphocytes were added to allow attachment.

For stimulation experiments, cell-free supernatants were centrifuged at 400 × g for 10 min before transfer of equal volumes to MSC culture. For transwell experiments, MSC were seeded either in 0.4 μm polycarbonate membrane inserts or in the reservoirs of 96-well flat-bottom receiver plates. Responder cells were added to the bottom reservoirs and co-incubated for 3 days.

Radionuclide incorporation assay

DNA synthesis during mitogen stimulation or mixed lymphocyte culture was assessed after 20 h pulsing with 1 μCi 3H-TTP before termination of the culture. Cells were harvested on glass fiber filters using a Filtermate 196 cell harvester (Packard Bioscience Co., CT, USA)21 and radioactivity was measured using a Wallac 1450 MicroBeta® TriLux (PerkinElmer) microplate scintillation counter. Relative inhibition of the culture was calculated by the following equation:

CFSE dilution assay

Responder cells were stained with CFSE prior to in vitro culture as previously described (Zinöcker et al., 2011b). Briefly, cells were resuspended in OPTI-MEM at 2 × 106 mL−1 and incubated with 0.5 μM CFSE for 10 min at 37°C. Stained cells were then washed (400 g for 8 min) in MLR medium, incubated once more for 5 min at 37°C, washed twice and resuspended in MLR medium.

At the termination of MLR and ConA cultures, cells were harvested and washed in PBS before immunostaining and flow cytometric analysis. Fifty micromolar propidium iodide was added before flow cytometric analysis to exclude non-viable cells. The percentage of dividing cells was determined as the fraction of cells that had undergone one or several cell divisions (CFSElo) relative to the total number of CFSE+ cells including cells that had not undergone cell divisions (CFSEhi).

Immunostaining and flow cytometric analysis

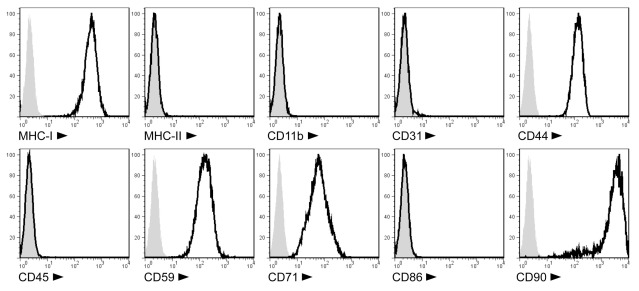

All MSC lines were tested for surface marker expression by flow cytometry. Cells were labeled with anti-CD11b, -CD31, -CD44, -CD45, -CD59, -CD71, -CD86, -CD90, anti-class I, and anti-class II MHC monoclonal antibodies (cf. Antibodies). Monoclonal mouse IgG1 and IgG2a were used as isotype controls.

For intracellular IFNγ staining, Brefeldin A (10 μg mL−1) was added 4 h prior to termination of ConA-stimulated LNC cultures to inhibit protein secretion. Cells from triplicate or quadruplicate wells were pooled, stained with anti-CD3 antibody, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, permeabilized with 0.5% saponin in water and stained with anti-IFNγ antibody.

For intracellular FoxP3 staining, ConA-stimulated LNC were harvested after 3 days and stained with anti-CD3, -CD4, -CD25 antibodies. Immunostained cells were subsequently treated with fixation/permeabilization buffer (eBioscience) and stained with anti-FoxP3 antibody following the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were analyzed on a FACSCalibur™ flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) using CellQuest™ software (BD Biosciences). FACS data were further analyzed using FlowJo™ software (Treestar, OR, USA)22.

Western blot

Cells were pooled from triplicates and lysed for 30 min on ice with buffer consisting of 25 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% (w/v) Triton® X-100, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride in isopropanol, 1 mM Na3VO4 and proteinase inhibitor cocktail (all from Sigma-Aldrich). Lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min to remove debris, and supernatants were resuspended in standard sample buffer containing 2% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate and 2.5% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol. Samples were then heated at 95°C for 5 min, allowed to cool at ambient temperature and loaded onto polyacrylamide gels. Electrophoresis was run at 80–200 V. Proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane in a TE 70 semi-dry transfer unit (GE Healthcare) using a current of 100 mA for 65 min. Western blotting was performed using anti-rat NOS2 (iNOS) and anti-rat GAPDH antibodies followed by secondary staining with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG. Chemiluminescent substrate was used to visualize the immunoreactive proteins by horseradish peroxidase detection.

NO quantification

The nitrite concentration in the medium was measured as an indicator of NO production by virtue of the Griess reaction (Beda and Nedospasov, 2005). Fifty microliters of cell-free supernatant from MLR or ConA cultures was mixed with equal volumes of 1% (w/v) sulfanilamide in 5% phosphoric acid and 0.1% (w/v) naphthylethylenediamine dihydrochloride in water. Absorbance of the reaction at 540 nm was measured using a Labsystems Multiskan® bichromatic plate reader (Titertek Instruments, AL, USA)23 and concentrations were calculated based on a standard curve of twofold dilutions of sodium nitrate which was assayed in parallel.

Cytokine assays

For cytokine measurements, supernatants from ConA cultures were collected after 2–3 days, pooled from triplicate or quadruplicate wells, centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 4 min to remove cellular debris and stored at −80°C or −20°C until analysis. Samples were thawed at 37°C in a water bath and analyzed using the Bio-Plex™ Rat Cytokine 9-Plex A Panel (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Concentrations were determined based on a standard curve using defined reference samples which were assayed (Luminex xMAP® Technology; Bio-Rad) in parallel.

Statistical analysis

Normal distribution of data was assumed and tested by Shapiro–Wilk’s test. The paired Student’s t test (two-tailed) was used to evaluate the probability of differences between group means. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS® software version 18.0.1 (SPSS, IL, USA)24.

Results

Generation of MSC lines from rat BM

We produced MSC lines from the BM of PVG.7B and PVG.1U MHC-congenic rats. The cells showed adherence to plastic and spindle-shaped fibroblast-like morphology in culture (data not shown). They expressed MHC class I, CD44, CD59, CD71, and CD90 surface markers, but lacked CD11b, CD31, CD45, CD86, and MHC class II expression (Figure 1). Their potential to develop into adipocytes and osteocytes was confirmed by in vitro differentiation assays (Zinöcker et al., manuscript submitted). Together, this data was in accordance with the current definition of the MSC phenotype (Dominici et al., 2006; Harting et al., 2008).

Figure 1.

Cell surface phenotype of PVG.7B MSC isolated from rat BM. Ex vivo-expanded MSC express MHC class I (RT1-A), CD44H (H-CAM), CD59 (MAC inhibitor), CD71 (transferrin receptor), and CD90 (Thy-1), but not MHC class II (RT1-B/D), CD11b (MAC-1), CD31 (PECAM-1), CD45 (LCA), or CD86 (B7-2) as detected by single-color flow cytometry. Representative stainings of MSC derived from PVG.7B BM are displayed as histograms [x-axis, signal intensity (log); y-axis, relative cell count (percent of max)] of surface antigens (solid line) and negative controls (gray histograms).

Rat BM–MSC inhibit allo-antigen and mitogen-induced T cell proliferation in vitro independent of MHC haplotype

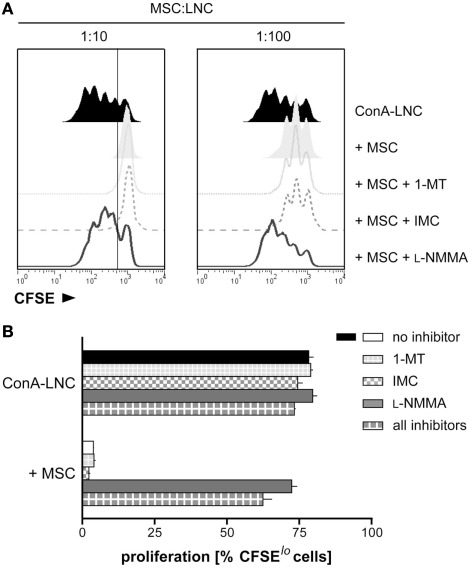

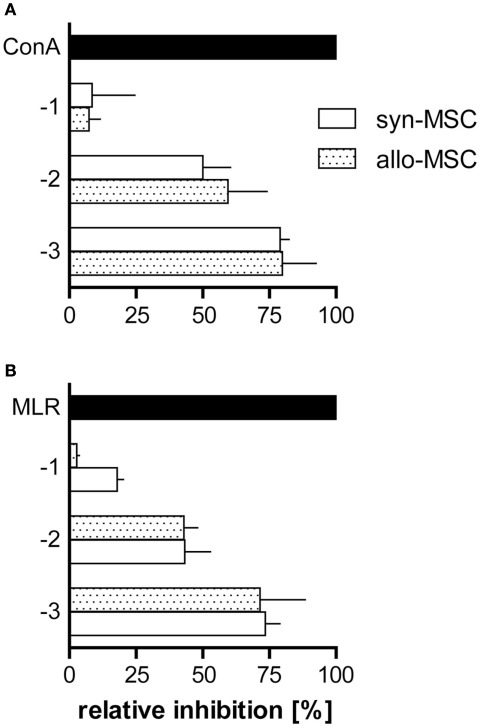

We tested the ability of MSC to inhibit lymphocyte proliferation induced by ConA or in allogeneic mixed lymphocyte cultures. ConA stimulation induced proliferation of LNC from PVG.7B (RT1c) rats as assessed by CFSE dilution and radio-labeled nucleotide incorporation. Proliferation was fully inhibited in the presence of PVG.7B MSC at a cell ratio of 1 MSC per 10 LNC (1:10); significant suppression was also observed at a ratio of 1:100 (Figure 2A). The inhibitory effect was not dependent on the MHC combination of MSC and responder cells as allogeneic PVG.1U (RT1u) and syngeneic PVG.7B MSC suppressed ConA-induced proliferation of PVG.7B responder cells equally well (Figure 3A). Similarly, both PVG.1U and PVG.7B MSC inhibited antigen-induced proliferation of both PVG.1U and PVG.7B responder cells in allogeneic MLR with equal efficiency (Figure 3B and data not shown). This suggested that the inhibitory capacity of MSC did not depend on the MHC-allotype, in line with previous findings (Krampera et al., 2003; Le Blanc et al., 2003). Proliferation of MSC alone was negligible and below the negative control (LNC proliferation in the absence of a stimulus), which was consistently less than 10% of the positive control (data not shown). Irradiation (2000 cGy) of MSC did not reduce their inhibitory capacity significantly in ConA- and MLR-induced lymphocyte cultures (data not shown), suggesting that this property is not dependent on their ability to proliferate. Cell-free supernatant from MSC culture had no suppressive effect (data not shown).

Figure 2.

MSC mediate suppression of mitogen-induced T cell proliferation through iNOS. (A) LNC from PVG.7B rats were labeled with CFSE and cultured in the presence of ConA for 3 days. Dilution of CFSE intensity was measured by flow cytometry to quantify lymphocyte proliferation. PVG.7B MSC were added at the start of culture at MSC:LNC ratios of 1:10 (left panel) or 1:100 (right panel), either alone (shaded off-set histograms) or together with inhibitors of IDO (1-MT, 1 mM; dotted line), COX (IMC, 5 μg mL−1; dashed line), or iNOS (L-NMMA, 1 mM; solid line). Proliferation in the absence of MSC is also shown (ConA–LNC, black histograms). MSC addition resulted in a complete or partial inhibition of ConA-induced proliferation at 1:10 and 1:100 MSC:LNC ratios, respectively. The proliferative response was fully restored by addition of L-NMMA while 1-MT or IMC had no effect. (B) In the same experimental set-up as shown in (A), inhibitors were added to ConA-stimulated LNC cultures in the absence or presence (MSC:LNC ratio 1:10) of MSC. The percentage of CFSElo cells was used as a measure of cells that had undergone one or several cell divisions. The gate shown in (A) marks the distinction between CFSElo and non-dividing CFSEhi cells. Data are representative of three independent experiments and are shown as mean and SD of triplicates.

Figure 3.

Syngeneic and allogeneic MSC block T cell proliferation in MLR and ConA-stimulated cultures with similar potency. PVG.7B and PVG.1U MSC were added at the start of LNC cultures [values on y-axis signify the common logarithm (log) of MSC:LNC cell ratios, i.e., 1:10 (−1), 1:100 (−2), 1:1000 (−3)] and proliferation was assessed by radio-labeled thymidine incorporation for the last 20 h of co-incubation in vitro. Inhibition was calculated relative to the positive control (normal proliferation in the absence of MSC; black bars) as described in Section “Materials and Methods.” (A) PVG.7B LNC responder cells were cultured in the presence of syngeneic (PVG.7B; white bars) or allogeneic (PVG.1U; dotted bars) MSC and ConA for 3 days. (B) PVG.1U LNC responder cells were cultured in the presence of irradiated PVG.R23 stimulator cells and syngeneic (PVG.1U; white bars) or allogeneic (PVG.7B; dotted bars) MSC for 4 days. Proliferation was efficiently suppressed by both syngeneic and allogeneic MSC in a cell dose-dependent manner. Data from representative experiments are shown as mean and SD of quadruplicates (A) or triplicates (B).

T cell proliferation in the presence of MSC is restored by addition of the iNOS inhibitor L-NMMA

We tested inhibitors of different signaling pathways which have been implicated in immunosuppression by MSC (Meisel et al., 2004; Aggarwal and Pittenger, 2005; Sato et al., 2007) and found that the addition of l-NMMA, an inhibitor of iNOS, at the start of MLR or ConA stimulation (Figure 2 and data not shown) restored proliferation to normal levels. Conversely, addition of 1-MT, an IDO inhibitor, or IMC, a COX inhibitor, had no effect. The presence of all three inhibitors in lymphocyte culture had no additional effect compared to l-NMMA alone (Figure 2B). l-NMMA fully reversed the proliferative arrest of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells which were equally affected by MSC inhibition (data not shown). Together, these data indicated that rMSC use iNOS to suppress T cell proliferation in vitro.

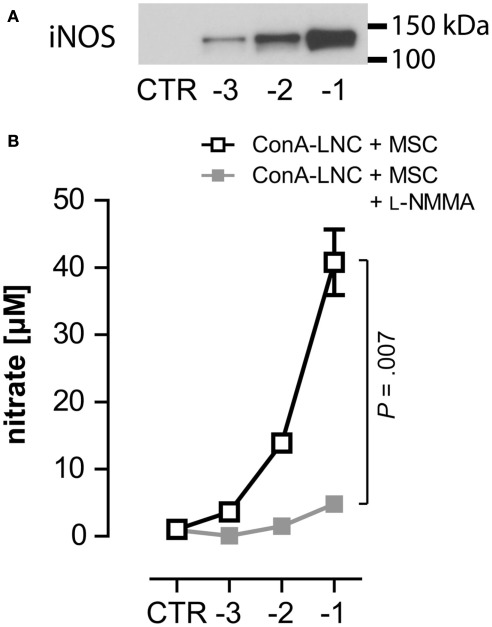

MSC express iNOS and produce NO in response to lymphocyte activation

Our findings suggested that the production of NO through iNOS was responsible for the suppression of T cell proliferation by rMSC. To test this hypothesis further, we measured the expression of iNOS by Western blot. iNOS was only detected in ConA cultures upon addition of MSC (Figure 4A) and correlated with the number of MSC present. iNOS was not detected in cultures of MSC alone, which suggested that its expression was induced in co-cultures with activated T lymphocytes. We also measured the concentration of nitrate as a proxy of NO (Beda and Nedospasov, 2005) and found that NO levels correlated with the observed iNOS levels. Neither MSC nor ConA-activated LNC cultures produced significant levels of NO (Figure 4B and data not shown). Notably, addition of l-NMMA did not affect iNOS protein levels (data not shown) but completely abrogated NO production (Figure 4B). We obtained identical results from MLR:MSC co-cultures (unpublished observations). The upregulation of iNOS in MSC co-cultures with stimulated lymphocytes correlated with the observed dose-dependent inhibition of proliferation (as shown in Figures 2 and 3) and thus provided further evidence that inducible NO production represents a key mechanism for the suppressive capacity of rMSC.

Figure 4.

MSC express iNOS and produce NO in response to lymphocyte stimulation. (A) 1 × 105 ConA-stimulated PVG LNC were cultured in the absence (CTR) or presence of syngeneic PVG.7B MSC [log (MSC:LNC)] and expression of iNOS was analyzed after 24 h. iNOS was detected in co-cultures of ConA–LNC with MSC and correlated with the numbers of MSC present. (B) In the same set-up as shown in (A) the amount of nitrate (shown as the mean and the SD of triplicates) as a proxy for NO concentration was determined in the absence (□) or presence ( ) of L-NMMA. Addition of L-NMMA abolished NO levels produced in MSC:LNC co-cultures. NO was not detected in the absence of MSC (CTR). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

) of L-NMMA. Addition of L-NMMA abolished NO levels produced in MSC:LNC co-cultures. NO was not detected in the absence of MSC (CTR). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Immunostimulatory cytokines induce iNOS expression in MSC

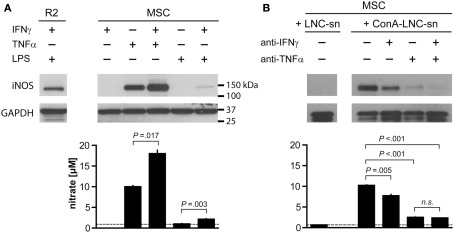

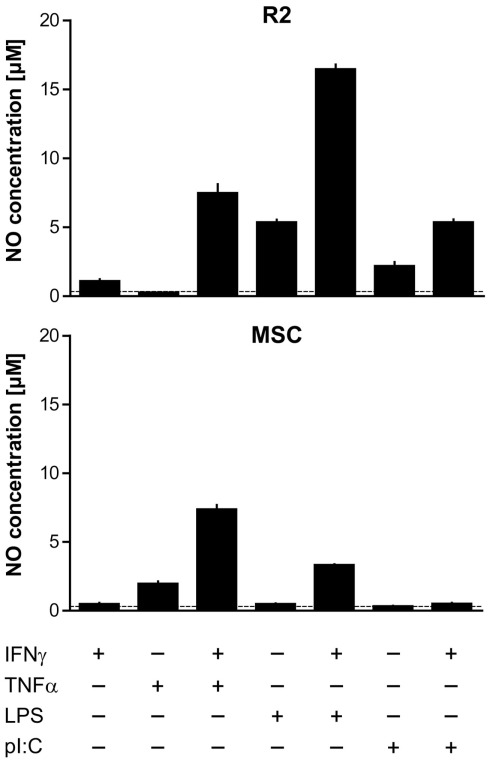

It has been proposed that MSC depend on “licensing” in order to assume immunosuppressive functions, e.g., by stimulation through IFNγ or a TLR3 ligand (Krampera et al., 2006; Waterman et al., 2010; Dazzi and Krampera, 2011). Furthermore, it has been shown that iNOS expression is induced in response to synergistic stimulation by pro-inflammatory cytokines in mMSC (IFNγ together with either TNF or IL1 signals; Ren et al., 2008; Ren et al., 2009), and we therefore tested whether this was the case also for rMSC. Different combinations of IFNγ, TNFα, and TLR agonists induced iNOS expression in rMSC as judged by Western blot analysis. Incubation with TNFα for 24 h was sufficient to induce iNOS expression and increase NO concentrations in fresh MSC cultures (Figure 5A). Conversely, addition of IFNγ did not activate iNOS at the concentrations tested (titrations of 15 up to 5000 U mL−1, data not shown) but potentiated the effect of TNFα resulting in significantly higher levels of both iNOS expression and NO compared with addition of TNFα alone (Figure 5A). LPS, a TLR4 agonist, or poly-I:C, a TLR3 agonist, resulted neither in iNOS expression nor NO production by MSC, in contrast to rat macrophages used as positive control (Figure 5A; Figure A1 in Appendix). LPS synergized with IFNγ in inducing iNOS expression in MSC, albeit with variable potency, while simultaneous stimulation with poly-I:C and IFNγ had no effect (Figure 5A; Figure A1 in Appendix).

Figure 5.

Tumor necrosis factor α and IFNγ synergistically induce iNOS expression and NO production by MSC. 1 × 104 MSC (PVG.7B) were stimulated for 24 h with combinations of IFNγ, TNFα, and a TLR agonist (A) or by medium supernatants from ConA-activated LNC (PVG.7B or PVG.1U) cultures (B). Pooled triplicates and quadruplicates, respectively, were analyzed for iNOS expression by Western blot with GAPDH assayed as a loading control. Nitrate concentrations were determined in the culture supernatants of the same wells (bottom panels). (A) MSC produced iNOS (130 kDa) in response to TNFα (25 ng mL−1) alone or together with IFNγ (100 U mL−1) or by a combination of IFNγ and LPS (100 ng mL−1). Nitrate concentration levels correlated with the observed levels of iNOS protein expression. The dotted line indicates baseline NO production without cytokines added. The R2 macrophage cell line was used as positive control for iNOS expression. (B) Supernatants from ConA-stimulated (ConA–LNC-sn) and unstimulated LNC cultures as a control (LNC-sn; baseline) were added to MSC cultures. Neutralizing antibodies (each 10 μg mL-1 final concentration) against either IFNγ or TNFα or both (indicated) were added at the start of culture and incubated for 24 h. iNOS was induced by addition of supernatant from stimulated LNC cultures and was blocked by IFNγ-specific antibody and, more potently, by TNFα-specific antibody alone or in combination. Nitrate concentrations correlated with the observed iNOS expression levels. Data are representative of four independent experiments. Nitrate concentration data are shown as the mean and the SD of triplicates or quadruplicates.

Supernatants from stimulated LNC cultures (allogeneic MLR or ConA culture) also led to a potent induction of iNOS (Figure 5B and data not shown) in MSC. The concentrations of NO in the culture medium were concordant with the observed protein expression levels. Induction of iNOS and NO production was inhibited by addition of anti-IFNγ antibody and, more potently, anti-TNFα antibody either alone or in combination (Figure 5B). These data indicate that the inflammatory cytokine TNFα has a key role in priming MSC for their immunosuppressive function, and that IFNγ potentiates this effect.

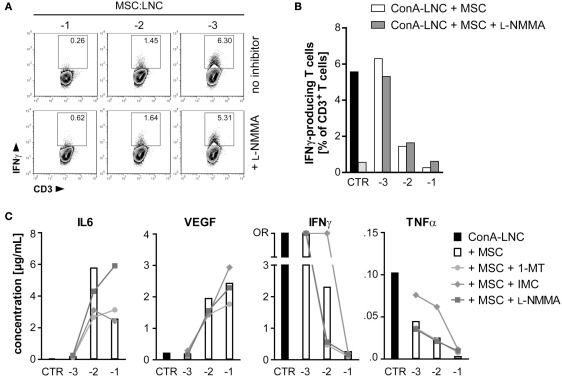

MSC-mediated inhibition of cytokine secretion by activated T cells is not dependent on iNOS activity but on COX-mediated production of prostaglandin

Next, we tested the influence of MSC on the cytokine secretion patterns of ConA-stimulated lymphocytes. Although iNOS was important for MSC-mediated inhibition of T cell proliferation, this factor could not explain the inhibitory effect on IFNγ production as evaluated by intracellular flow cytometry following addition of l-NMMA to the LNC–MSC co-cultures (Figures 6A,B). We further measured cytokine profiles by multiplex analysis and found that MSC constitutively secreted IL6 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) but not other cytokines analyzed (data not shown). The addition of MSC resulted in an accumulation of IL6 and VEGF also in ConA-stimulated LNC–MSC co-cultures (Figure 6C) as reported previously (Djouad et al., 2007). Addition of neutralizing concentrations (2 μg mL−1) of anti-rat IL6 antibody to the co-culture failed to reverse inhibition (data not shown), in contrast to previous studies of human and mouse MSC (Di Nicola et al., 2002; Djouad et al., 2007; Najar et al., 2009). LNC secreted significant amounts of the cytokines IL18, TNFα, and in particular IFNγ in response to ConA, which were markedly reduced when MSC were present. The inhibitory effect was proportionate to the numbers of MSC added (Figure 6C and data not shown). Addition of recombinant rat IFNγ (1000 U mL−1) to the co-culture failed to reverse the suppressive effect (data not shown). Expression levels of IL4 and IL10, cytokines which are typically considered as anti-inflammatory, were not increased in co-culture supernatants (data not shown).

Figure 6.

MSC inhibition of IFNγ and TNFα secretion is not dependent on iNOS activity, but on COX-dependent production of prostaglandin. (A,B) MSC (PVG.7B) were added at the indicated dilutions [log (MSC:LNC)] at the start of ConA–LNC (PVG.7B) cultures. Cells from triplicate wells were pooled after 24 h and the number of IFNγ-positive T cells (IFNγ+CD3+ lymphocyte gate, values indicate relative frequencies) determined by flow cytometry. Inhibition of iNOS by L-NMMA (bottom row and shaded bars) did not influence the MSC-mediated suppression of IFNγ expression (top row and unshaded bars). Controls in (B) show IFNγ production by T cells alone in the presence (black) or absence (light gray) of ConA. (C) MSC (PVG.1U) were added at the indicated cell ratios [log] at the start of ConA–LNC (PVG.7B) cultures in the absence (white bars) or presence of IDO (1-MT, 1 mM; circles), PGE2 (IMC, 5 μg mL−1; diamonds), or iNOS (L-NMMA, 1 mM; squares) inhibitors. Cytokine concentrations in the culture supernatants were determined after 3 days of incubation. As a control (CTR) was used supernatant from ConA–LNC culture without MSC. Levels of IL6 and VEGF were significantly increased while IFNγ and TNFα were significantly reduced in a MSC dose-dependent manner. Addition of L-NMMA or 1-MT had no effect on the cytokine expression profiles. Addition of IMC reversed in part the suppression of IFNγ and TNFα by MSC. Data are representative of two independent experiments and are shown as the average of duplicates; OR, data point out of detection range.

Addition of l-NMMA had no effect on MSC-mediated modulation of cytokine secretion in co-culture experiments, and the same was true for the IDO antagonist 1-MT. By contrast, addition of the COX inhibitor indomethacin resulted in a striking reversal of inhibition of IFNγ and TNFα secretion at a MSC:LNC ratio of 1:100, but not at the highest ratio of 1:10 (Figure 6C). This result suggested that MSC can inhibit T cell mediated secretion of inflammatory cytokines by COX-dependent synthesis of PGE2.

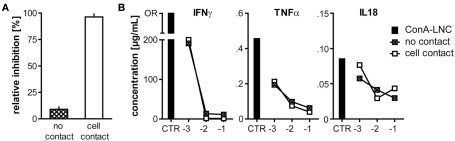

Inhibition of proliferation but not cytokine production is dependent on co-localization of MSC and T cells

The immunosuppressive effect of hMSC depends on soluble factors such as IDO, PGE2, hepatocyte growth factor and transforming growth factor β1 (Di Nicola et al., 2002; Meisel et al., 2004; Aggarwal and Pittenger, 2005) and does not require cell contact (Hoogduijn et al., 2010) although there have been reports that co-localization of MSC with lymphocytes augmented inhibition (Krampera et al., 2003). mMSC require proximity for the effective inhibition of T cells by short-range activity of NO (Ren et al., 2008). Therefore, we examined whether inhibition of T cell effector function by MSC in the rat depended on cell-to-cell contact or if other soluble factors might be important. Physical separation of MSC from LNC using transwell membrane inserts restored ConA-stimulated proliferation which was inhibited in co-cultures where LNC and MSC were in contact (Figure 7A), indicating that suppression of proliferation required close proximity of MSC and target cells. In marked contrast, the cytokine secretion profiles in these cultures were altered irrespective of cell-to-cell contact (Figure 7B). IL6 and VEGF were increased to similar levels when MSC and LNC were either co-localized or separated (data not shown). Inflammatory cytokines were significantly reduced in the presence of MSC in either experimental set-up (Figure 7B). These latter data showed that inhibition of cytokine expression required a soluble factor, likely PGE2, and provided further evidence that this property of rMSC is not dependent on close cellular contact.

Figure 7.

MSC-mediated inhibition of proliferation, but not cytokine secretion requires close cellular contact. (A) 5 × 104 MSC (PVG.7B) were cultured together with ConA (3 μg mL-1)-stimulated LNC (5 × 105, i.e., a cell ratio of 1:10) either separate from LNC (PVG.7B) in transwell membrane inserts (no contact) or co-localized (cell contact) for 3 days. Relative inhibition of proliferation measured as 3H-TTP incorporation is shown as the mean and the SD of triplicates. Cell proliferation was inhibited by MSC only when in proximity to target cells (P = 0.001). (B) In the same set-up as shown in (A) increasing numbers of MSC [log] were co-cultured with ConA–LNC in transwell plates either separately (crossed squares) or co-localized (unfilled squares). Cytokine concentrations were assayed in the culture supernatants after 3 days (shown as the average of duplicates). IL18, IFNγ, and TNFα were significantly reduced in a MSC dose-dependent, contact-independent manner. OR, data point out of range.

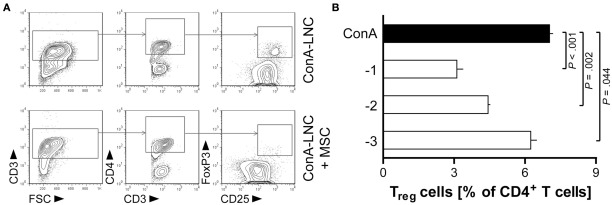

Treg cell numbers are reduced in stimulated lymphocyte co-cultures with MSC

We also analyzed the effect of MSC on the CD4+CD25hiFoxP3+ Treg cell population using mitogen-induced lymphocyte cultures. The proportion of Treg cells was significantly diminished in the CD4+ T cell population by addition of MSC at the start of the culture (Figure 8). This finding is in contrast to a number of previous studies which have demonstrated the induction of Treg cells by MSC in the human system (Aggarwal and Pittenger, 2005; Di Ianni et al., 2008; English et al., 2009; Ghannam et al., 2010; Mougiakakos et al., 2011). It should be noted that the functional potential of these Treg-like cells has not been tested in the present study.

Figure 8.

MSC diminish the proportion of CD4+CD25hiFoxP3+ Treg-like cells in ConA-stimulated lymphocyte cultures. MSC (PVG.7B) were added at the start of ConA-stimulated LNC cultures in vitro. The frequencies of Treg cells were analyzed after 3 days by flow cytometry. Representative plots depict in (A) the gating of lymphocytes (lymphocyte gate not shown) for CD3+CD4+CD25hiFoxP3+cells in the absence or presence of MSC (MSC:LNC ratio of 1:10). (B) The relative fraction of Treg cells among CD4+ T cells (means and SD of triplicates) was reduced compared to control (black bar) in a MSC dose-dependent manner. Data are representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

Herein we show that rat BM-derived MSC up-regulate iNOS in response to TNFα and IFNγ secreted by activated lymphocytes and produce NO, which exerts a potent inhibitory effect on the proliferative T cell response to mitogen or allogeneic stimuli in vitro. The present study supports an important but not exclusive role of iNOS in the immunosuppressive function of MSC in rodents (Oh et al., 2007; Sato et al., 2007; Ren et al., 2008). COX-dependent PGE2 is apparently also involved, in the inhibition of IFNγ and TNFα secretion by activated T cells.

To our knowledge, the only study that has investigated the immunosuppressive function of rMSC via iNOS to date (Chabannes et al., 2007) showed an effect in combination with heme oxygenase-1, but not a critical role for iNOS per se. Furthermore, that study showed that stimulation with recombinant IFNγ alone resulted in detectable expression of iNOS, which is in contrast to our findings showing that TNFα is sufficient and IFNγ is not required. This difference could be related to variations in cell isolation protocols, culture conditions, or between different rat strains. The MSC line generated from LEW.1A BM by Chabannes et al. (2007) were applied before the fourth passage and a minority of myeloid cells present in this population (3.2% of the cells expressed CD45) could account for the reported detection of iNOS expression in response to IFNγ.

Tumor necrosis factor α, a potent mediator of immune stimulation, induced iNOS expression in rMSC in vitro without a requirement for auxiliary signals, and neutralizing the TNFα signal in the supernatant from stimulated lymphocyte cultures abolished it, underlining the importance of this cytokine in MSC modulation of T cell activation. The pro-inflammatory cytokine IFNγ has also been ascribed an important role in the inhibition of T cell responses mediated by MSC (Krampera et al., 2006; Ryan et al., 2007). IFNγ levels were markedly reduced after addition of MSC to LNC cultures and attempts to restore T cell proliferation by addition of exogenous IFNγ were unsuccessful. Although IFNγ did not by itself induce iNOS expression in MSC it did show a synergistic effect in combination with TNFα or certain TLR ligands (LPS, but not poly-I:C) in support of studies performed in the mouse (Oh et al., 2007; Ren et al., 2008, 2009). This could explain why blocking the IFNγ signal by addition of anti-IFNγ antibody resulted in a significant reduction of iNOS expression in co-culture experiments as others also have shown (Oh et al., 2007; Ren et al., 2008).

Our data are in agreement with reports that have argued for “licensing” of MSC to acquire suppressor functionality (Waterman et al., 2010; Dazzi and Krampera, 2011). Collectively, our results support a model for the regulation of suppressor functions by rat BM stromal cells where MSC are primed by inflammatory signals, e.g., immunostimulatory cytokines, primarily TNFα, to induce iNOS expression leading to the accumulation of NO and in turn the inhibition of proliferation of activated T cells in the immediate proximity. In addition, MSC effectively shut off the generation of inflammatory cytokines by activated T cells (Ren et al., 2008) via a soluble factor dependent on COX activity, likely PGE2.

The mechanisms employed to achieve immunosuppression are not identical in different species. In mMSC (Ren et al., 2008), as in rMSC, iNOS expression seems critically important for the inhibition of T cell proliferation. Our data imply that the cytokine requirement of MSC to activate this inhibitory pathway is not identical in rats (TNFα alone is sufficient) and mice (IFNγ and any of the cytokines TNFα, IL1α, or IL1β are required). Ren et al. (2009) demonstrated that other inhibitory mechanisms, namely the secretion of IDO, but not iNOS, were employed by monkey and human BM-derived MSC in this context.

MSC-mediated inhibition of secretion of IFNγ and TNFα by activated T cells was dissociated from iNOS activity and NO, as demonstrated by transwell cultures and biochemical inhibition of iNOS. Our data are in contrast with a study of mMSC, which suggested that iNOS is involved in inhibiting IFNγ production by T cells stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 beads in the presence of IL12 and anti-IL4 antibody (Oh et al., 2007). Our study identifies PGE2 as a candidate soluble factor responsible for the dampening of inflammatory cytokine production by activated lymphocytes, in agreement with a previous study of hMSC (Aggarwal and Pittenger, 2005). Taken together, it can be concluded that rMSC utilize different pathways to regulate proliferation and cytokine production by T cells. The species-specific mechanisms regulating the suppression of immune cell activation and effector functions through BM stromal progenitor cells should be investigated further, because this research might have important implications for the use of MSC or related cell types in the clinical treatment of GVHD, autoimmune diseases or other syndromes of undesired T cell activity.

In a separate series of experiments, we have tested the therapeutic potential of the MSC lines presented here in a model of experimental GVHD induced by donor lymphocyte infusions after MHC-mismatched allogeneic stem cell transplantation (Zinöcker et al., 2011a). Despite their marked inhibitory potential in vitro, repeated systemic injections of MSC did not improve GVHD in these experiments even after prestimulaton with IFNγ and TNFα to boost the iNOS pathway in MSC (Zinöcker et al., manuscript submitted). This suggests that their immunosuppressive efficacy is limited with respect to GVHD-related morbidity and mortality.

We show here that rMSC suppress proliferation in vitro only when in close proximity to stimulated T cells through short-range activity of NO. The route of administration may determine the effectiveness of treatment if co-localization of MSC is required for the efficient suppression of alloreactive immune cells in vivo. We have previously observed by in vivo imaging that MSC which expressed enhanced green fluorescence protein transgenically accumulated in the lungs shortly (within minutes) after intravenous injection but did not detect these cells at that site or in other organs after several days in vivo and post mortem (unpublished observations). Failure to migrate to sites of allopriming and alloreactivity in GVHD is a plausible explanation for the observed lack of efficiency of MSC therapy.

Besides NO synthases, arginase 1 is an important enzyme that regulates l-arginine metabolism and production of NO and has the ability to inhibit T cell proliferation (Grohmann and Bronte, 2010). We did not address a potential role of arginase 1 in the suppression of activated T cells by rMSC in this study. If these cells make use of other, potentially redundant molecular pathways to inhibit T cells or other immune cell types, the strength of NO-dependent immunosuppression observed in this study would suggest that such alternative mechanisms are of minor importance regarding MSC-mediated inhibition of T cell proliferation in the rat species.

MSC have been shown to induce different subtypes of Treg cells (Aggarwal and Pittenger, 2005; Di Ianni et al., 2008; English et al., 2009; Ghannam et al., 2010; Mougiakakos et al., 2011) as potential immunomodulatory mechanisms operating in vivo (Hoogduijn et al., 2010). Our finding that CD4+CD25hiFOXP3+ Treg cells were reduced after ConA-stimulation of T cells in the presence of rMSC was in marked contrast to the studies with hMSC and makes it less likely that Treg cells are involved in the observed inhibition of proliferation or cytokine secretion of activated rat T cells in vitro. Further experiments could clarify the functional characteristics of this putative Treg cell type.

Recently, Turley and co-workers presented findings which showed that iNOS represents a central pathway employed by both fibroblastic reticular and lymphoid endothelial cells to regulate T cell activation in the lymph nodes of mice (Lukacs-Kornek et al., 2011). The observed inhibitory effects depended on IFNγ, TNF and direct cell contact (Lukacs-Kornek et al., 2011) and correlate well with our observations for rMSC, which displayed very similar cytokine requirements and inhibitory effects. We therefore speculate that the enzymatic conversion of NO is a common feature of stromal cells in rodents (Jones et al., 2007), which, in combination with PGE2, control T cell expansion at sites of priming of the adaptive immune system (Lukacs-Kornek et al., 2011) and subsequent inflammation (Nombela-Arrieta et al., 2011).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Stine Martinsen for excellent technical support, Marit Inngjerdingen for help with cytokine assays, Meng-Yu Wang for antibodies, and Bent Rolstad for advice. The R2 cell line was a generous gift from Dr. Jan G. M. C. Damoiseaux. The OX hybridoma cell lines were a generous gift from A. Neil Barclay. This work was supported by grants from the Norwegian Cancer Society, Solveig og Ove Lunds legat, and the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority. The funding institutions had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Appendix

Figure A1.

Comparison of cytokine and TLR ligand requirements for NO production by macrophages and MSC. R2 macrophages (top panel) and MSC (PVG.7B; bottom panel) were stimulated for 24 h with IFNγ (100 U mL−1), TNFα (25 ng mL−1), LPS (1 μg mL−1), and poly-I:C (1 μg mL−1), either alone or in combination with IFNγ as indicated. R2 macrophages produced significant levels of NO in response to the TLR agonists LPS and poly-I:C as well as IFNγ. In MSC, NO was only generated in response to TNFα but not to the other stimulatory agents. Addition of IFNγ had a synergistic effect in combination with TNFα or LPS in both macrophages and MSC. The dotted lines indicate baseline NO production of the respective cell type without cytokines added.

Footnotes

References

- Aggarwal S., Pittenger M. F. (2005). Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood 105, 1815–1822 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beda N., Nedospasov A. (2005). A spectrophotometric assay for nitrate in an excess of nitrite. Nitric Oxide 13, 93–97 10.1016/j.niox.2005.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan C. (2001). Nitric oxide and the immune response. Nat. Immunol. 2, 907–916 10.1038/ni1001-907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabannes D., Hill M., Merieau E., Rossignol J., Brion R., Soulillou J. P., Anegon I., Cuturi M. C. (2007). A role for heme oxygenase-1 in the immunosuppressive effect of adult rat and human mesenchymal stem cells. Blood 110, 3691–3694 10.1182/blood-2007-02-075481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crop M. J., Baan C. C., Korevaar S. S., IJzermans J. N. M., Pescatori M., Stubbs A. P., Van IJcken W. F. J., Dahlke M. H., Eggenhofer E., Weimar W., Hoogduijn M. J. (2010). Inflammatory conditions affect gene expression and function of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 162, 474–486 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04256.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Meirelles L., Chagastelles P. C., Nardi N. B. (2006). Mesenchymal stem cells reside in virtually all post-natal organs and tissues. J. Cell Sci. 119, 2204–2213 10.1242/jcs.02932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damoiseaux J., Döpp E., Calame W., Chao D., MacPherson G., Dijkstra C. (1994). Rat macrophage lysosomal membrane antigen recognized by monoclonal antibody ED1. Immunology 83, 140–147 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dazzi F., Krampera M. (2011). Mesenchymal stem cells and autoimmune diseases. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Haematol. 24, 49–57 10.1016/j.beha.2011.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W., Thiel B., Tannenbaum C. S., Hamilton T. A., Stuehr D. J. (1993). Synergistic cooperation between T cell lymphokines for induction of the nitric oxide synthase gene in murine peritoneal macrophages. J. Immunol. 151, 322–329 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ianni M., Del Papa B., De Ioanni M., Moretti L., Bonifacio E., Cecchini D., Sportoletti P., Falzetti F., Tabilio A. (2008). Mesenchymal cells recruit and regulate T regulatory cells. Exp. Hematol. 36, 309–318 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nicola M., Carlo-Stella C., Magni M., Milanesi M., Longoni P. D., Matteucci P., Grisanti S., Gianni A. M. (2002). Human bone marrow stromal cells suppress T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by cellular or nonspecific mitogenic stimuli. Blood 99, 3838–3843 10.1182/blood.V99.10.3838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djouad F., Charbonnier L. M., Bouffi C., Louis-Plence P., Bony C., Apparailly F., Cantos C., Jorgensen C., Noel D. (2007). Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the differentiation of dendritic cells through an interleukin-6-dependent mechanism. Stem Cells 25, 2025–2032 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominici M., Le Blanc K., Mueller I., Slaper-Cortenbach I., Marini F., Krause D., Deans R., Keating A., Prockop D., Horwitz E. (2006). Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 8, 315–317 10.1080/14653240600855905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English K., Ryan J. M., Tobin L., Murphy M. J., Barry F. P., Mahon B. P. (2009). Cell contact, prostaglandin E2 and transforming growth factor beta-1 play non-redundant roles in human mesenchymal stem cell induction of CD4+CD25high forkhead box P3+ regulatory T cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 156, 149–160 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03874.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghannam S., Pene J., Torcy-Moquet G., Jorgensen C., Yssel H. (2010). Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit human Th17 cell differentiation and function and induce a T regulatory cell phenotype. J. Immunol. 185, 302–312 10.4049/jimmunol.0902007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grohmann U., Bronte V. (2010). Control of immune response by amino acid metabolism. Immunol. Rev. 236, 243–264 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00915.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harting MT., Jimenez F., Pati S., Baumgartner J., Cox CS. (2008). Immunophenotype characterization of rat mesenchymal stromal cells. Cytotherapy 10, 243–253 10.1080/14653240801950000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogduijn M. J., Popp F., Verbeek R., Masoodi M., Nicolaou A., Baan C., Dahlke M. H. (2010). The immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stem cells and their use for immunotherapy. Int. Immunopharmacol. 10, 1496–1500 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- in ’t Anker P. S., Noort W. A., Scherjon S. A., Kleijburg-van der Keur C., Kruisselbrink A. B., van Bezooijen R. L., Beekhuizen W., Willemze R., Kanhai H. H., Fibbe W. E. (2003). Mesenchymal stem cells in human second-trimester bone marrow, liver, lung, and spleen exhibit a similar immunophenotype but a heterogeneous multilineage differentiation potential. Haematologica 88, 845–852 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- in ’t Anker P. S., Scherjon S. A., Kleijburg-van der Keur C., de Groot-Swings G. M. J. S., Claas F. H. J., Fibbe W. E., Kanhai H. H. H. (2004). Isolation of mesenchymal stem cells of fetal or maternal origin from human placenta. Stem Cells 22, 1338–1345 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S., Horwood N., Cope A., Dazzi F. (2007). The antiproliferative effect of mesenchymal stem cells is a fundamental property shared by all stromal cells. J. Immunol. 179, 2824–2831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo S. Y., Cho K. A., Jung Y. J., Kim H. S., Park S. Y., Choi Y. B., Hong K. M., Woo S. Y., Seoh J. Y., Cho S. J., Ryu K. H. (2010). Mesenchymal stromal cells inhibit graft-versus-host disease of mice in a dose-dependent manner. Cytotherapy 12, 361–370 10.3109/14653240903502712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krampera M., Cosmi L., Angeli R., Pasini A., Liotta F., Andreini A., Santarlasci V., Mazzinghi B., Pizzolo G., Vinante F., Romagnani P., Maggi E., Romagnani S., Annunziato F. (2006). Role for interferon-gamma in the immunomodulatory activity of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 24, 386–398 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krampera M., Glennie S., Dyson J., Scott D., Laylor R., Simpson E., Dazzi F. (2003). Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the response of naive and memory antigen-specific T cells to their cognate peptide. Blood 101, 3722–3729 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Blanc K., Frassoni F., Ball L., Locatelli F., Roelofs H., Lewis I., Lanino E., Sundberg B., Bernardo M. E., Remberger M., Dini G., Egeler R. M., Bacigalupo A., Fibbe W., Ringdén O. (2008). Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of steroid-resistant, severe, acute graft-versus-host disease: a phase II study. Lancet 371, 1579–1586 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60690-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Blanc K., Rasmusson I., Sundberg B., Gotherstrom C., Hassan M., Uzunel M. (2004). Treatment of severe acute graft-versus-host disease with third party haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells. Lancet 363, 1439–1441 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16104-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Blanc K., Tammik L., Sundberg B., Haynesworth S. E., Ringdén O. (2003). Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit and stimulate mixed lymphocyte cultures and mitogenic responses independently of the major histocompatibility complex. Scand. J. Immunol. 57, 11–20 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2003.01176.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejeune P., Lagadec P., Onier N., Pinard D., Ohshima H., Jeannin J. F. (1994). Nitric oxide involvement in tumor-induced immunosuppression. J. Immunol. 152, 5077–5083 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon D. P., Caplan A. I. (2006). Isolation of rat marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Exp. Hematol. 34, 1606–1607 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew F. Y., Li Y., Moss D., Parkinson C., Rogers M. V., Moncada S. (1991). Resistance to Leishmania major infection correlates with the induction of nitric oxide synthase in murine macrophages. Eur. J. Immunol. 21, 3009–3014 10.1002/eji.1830211027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorsbach R. B., Murphy W. J., Lowenstein C. J., Snyder S. H., Russell S. W. (1993). Expression of the nitric oxide synthase gene in mouse macrophages activated for tumor cell killing. Molecular basis for the synergy between interferon-gamma and lipopolysaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 1908–1913 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukacs-Kornek V., Malhotra D., Fletcher A. L., Acton S. E., Elpek K. G., Tayalia P., Collier A. R., Turley S. J. (2011). Regulated release of nitric oxide by nonhematopoietic stroma controls expansion of the activated T cell pool in lymph nodes. Nat. Immunol. 12, 1096–1104 10.1038/ni.2112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin P. J., Uberti J. P., Soiffer R. J., Klingemann H., Waller E. K., Daly A. S., Herrmann R. P., Kebriaei P. (2010). Prochymal improves response rates in patients with steroid-refractory acute graft versus host disease (SR-GVHD) involving the liver and gut: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter phase III trial in GVHD. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 16, S169–S170.

- Medot-Pirenne M., Heilman M. J., Saxena M., McDermott P. E., Mills C. D. (1999). Augmentation of an antitumor CTL response in vivo by inhibition of suppressor macrophage nitric oxide. J. Immunol. 163, 5877–5882 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisel R., Zibert A., Laryea M., Gobel U., Daubener W., Dilloo D. (2004). Human bone marrow stromal cells inhibit allogeneic T-cell responses by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-mediated tryptophan degradation. Blood 103, 4619–4621 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min C. K., Kim B. G., Park G., Cho B., Oh I. H. (2007). IL-10-transduced bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells can attenuate the severity of acute graft-versus-host disease after experimental allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 39, 637–645 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mougiakakos D., Jitschin R., Johansson C. C., Okita R., Kiessling R., Le Blanc K. (2011). The impact of inflammatory licensing on heme oxygenase-1-mediated induction of regulatory T cells by human mesenchymal stem cells. Blood 117, 4826–4835 10.1182/blood-2010-12-324038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Fernández M. A., Fernández M. A., Fresno M. (1992). Synergism between tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma on macrophage activation for the killing of intracellular Trypanosoma cruzi through a nitric oxide-dependent mechanism. Eur. J. Immunol. 22, 301–307 10.1002/eji.1830220203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najar M., Rouas R., Raicevic G., Boufker H. I., Lewalle P., Meuleman N., Bron D., Toungouz M., Martiat P., Lagneaux L. (2009). Mesenchymal stromal cells promote or suppress the proliferation of T lymphocytes from cord blood and peripheral blood: the importance of low cell ratio and role of interleukin-6. Cytotherapy 11, 570–583 10.1080/14653240903079377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasef A., Ashammakhi N., Fouillard L. (2008). Immunomodulatory effect of mesenchymal stromal cells: possible mechanisms. Regen. Med. 3, 531–546 10.2217/17460751.3.4.531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauta A. J., Fibbe W. E. (2007). Immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stromal cells. Blood 110, 3499–3506 10.1182/blood-2007-02-069716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicklas W., Baneux P., Boot R., Decelle T., Deeny A. A., Fumanelli M., Illgen-Wilcke B. (2002). Recommendations for the health monitoring of rodent and rabbit colonies in breeding and experimental units. Lab. Anim. 36, 20–42 10.1258/0023677021911740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedbala W., Cai B., Liew F. Y. (2006). Role of nitric oxide in the regulation of T cell functions. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 65, iii37–iii40 10.1136/ard.2006.058446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedbala W., Cai B., Liu H., Pitman N., Chang L., Liew F. Y. (2007). Nitric oxide induces CD4+CD25+ Foxp3− regulatory T cells from CD4+CD25− T cells via p53, IL-2, and OX40. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 15478–15483 10.1073/pnas.0703725104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nombela-Arrieta C., Ritz J., Silberstein L. E. (2011). The elusive nature and function of mesenchymal stem cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 126–131 10.1038/nrm3049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh I., Ozaki K., Sato K., Meguro A., Tatara R., Hatanaka K., Nagai T., Muroi K., Ozawa K. (2007). Interferon-[gamma] and NF-[kappa]B mediate nitric oxide production by mesenchymal stromal cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 355, 956–962 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.02.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger M. F., Mackay A. M., Beck S. C., Jaiswal R. K., Douglas R., Mosca J. D., Moorman M. A., Simonetti D. W., Craig S., Marshak D. R. (1999). Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 284, 143–147 10.1126/science.284.5411.143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polchert D., Sobinsky J., Douglas G., Kidd M., Moadsiri A., Reina E., Genrich K., Mehrotra S., Setty S., Smith B., Bartholomew A. (2008). IFN-γ activation of mesenchymal stem cells for treatment and prevention of graft versus host disease. Eur. J. Immunol. 38, 1745–1755 10.1002/eji.200738129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren G., Su J., Zhang L., Zhao X., Ling W., L’Huillie A., Zhang J., Lu Y., Roberts A. I., Ji W., Zhang H., Rabson A. B., Shi Y. (2009). Species variation in the mechanisms of mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression. Stem Cells 27, 1954–1962 10.1002/stem.118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren G., Zhang L., Zhao X., Xu G., Zhang Y., Roberts A. I., Zhao R. C., Shi Y. (2008). Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression occurs via concerted action of chemokines and nitric oxide. Cell Stem Cell 2, 141–150 10.1016/j.stem.2007.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner P., Eggenhofer E., Rosenauer A., Popp F. C., Steinmann J. F., Slowik P., Geissler E. K., Piso P., Schlitt H. J., Dahlke M. H. (2009). Mesenchymal stem cells require a sufficient, ongoing immune response to exert their immunosuppressive function. Transplant. Proc. 41, 2607–2611 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.06.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringdén O., Uzunel M., Rasmusson I., Remberger M., Sundberg B., Lonnies H., Marschall H. U., Dlugosz A., Szakos A., Hassan Z., Omazic B., Aschan J., Barkholt L., Le Blanc K. (2006). Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of therapy-resistant graft-versus-host disease. Transplantation 81, 1390–1397 10.1097/01.tp.0000214462.63943.14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan J., Barry F., Murphy J., Mahon B. (2007). Interferon-γ does not break, but promotes the immunosuppressive capacity of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 149, 353–363 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03422.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K., Ozaki K., Oh I., Meguro A., Hatanaka K., Nagai T., Muroi K., Ozawa K. (2007). Nitric oxide plays a critical role in suppression of T-cell proliferation by mesenchymal stem cells. Blood 109, 228–234 10.1182/blood-2006-02-002246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y., Deng Y. B., Huang Y. J., Wang Y. (2008). Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells decrease acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cells transplantation. Immunol. Invest. 37, 29–42 10.1080/08820130701410223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisato V., Naresh K., Girdlestone J., Navarrete C., Dazzi F. (2007). Mesenchymal stem cells of cord blood origin are effective at preventing but not treating graft-versus-host disease. Leukemia 21, 1992–1999 10.1038/sj.leu.2404847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolar J., Villeneuve P., Keating A. (2011). Mesenchymal stromal cells for graft-versus-host disease. Hum. Gene Ther. 22, 257–262 10.1089/hum.2011.1104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uccelli A., Moretta L., Pistoia V. (2006). Immunoregulatory function of mesenchymal stem cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 36, 2566–2573 10.1002/eji.200636416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterman R. S., Tomchuck S. L., Henkle S. L., Betancourt A. M. (2010). A New Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC) Paradigm: polarization into a pro-inflammatory MSC1 or an immunosuppressive MSC2 phenotype. PLoS ONE 5, e10088. 10.1371/journal.pone.0010088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanez R., Lamana M. L., Garcia-Castro J., Colmenero I., Ramirez M., Bueren J. A. (2006). Adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells have in vivo immunosuppressive properties applicable for the control of the graft-versus-host disease. Stem Cells 24, 2582–2591 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura H., Muneta T., Nimura A., Yokoyama A., Koga H., Sekiya I. (2007). Comparison of rat mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, synovium, periosteum, adipose tissue, and muscle. Cell Tissue Res. 327, 449–462 10.1007/s00441-006-0308-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinöcker S., Sviland L., Dressel R., Rolstad B. (2011a). Kinetics of lymphocyte reconstitution after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: markers of graft-versus-host disease. J. Leukoc. Biol. 90, 177–187 10.1189/jlb.0211067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinöcker S., Wang M., Gaustad P., Kvalheim G., Rolstad B., Vaage J. T. (2011b). Mycoplasma contamination revisited: mesenchymal stromal cells harboring mycoplasma hyorhinis potently inhibit lymphocyte proliferation in vitro. PloS ONE 6, e16005. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuk P. A., Zhu M., Mizuno H., Huang J., Futrell J. W., Katz A. J., Benhaim P., Lorenz H. P., Hedrick M. H. (2001). Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies. Tissue Eng. 7, 211–228 10.1089/107632701300062859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]