Abstract

A multi-site, observational study of sexual activity-related outcomes among patients enrolled in the TRIUMPH Registry during hospitalization for an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) was conducted to identify patterns and loss of sexual activity 1 year following hospitalization for AMI. Gender-specific multivariable hierarchical models were used to identify correlates of loss of sexual activity, including physician counseling. Main outcome measures included “loss of sexual activity” (less frequent or no sexual activity one year after an AMI in those who were sexually active in the year before the AMI) and 1-year mortality. Mean age (years) was 61.1 for women (n=605) and 58.6 for men (n=1274). Many were sexually active in the year before and 1 year after hospitalization (44% and 40% of women, 74% and 68% of men, respectively). A third of women and 47% of men reported receiving hospital discharge instructions about resuming sex. Those who did not receive instructions were more likely to report loss of sexual activity (women: adjusted RR 1.44, 95% CI 1.16–1.79; men: adjusted RR 1.27, 95% CI 1.11–1.46). One year post-AMI mortality was similar among those who reported sexual activity in the first month after their AMI (2.1%) and those who were sexually inactive (4.1%) (p=0.08). In conclusion, although many patients were sexually active prior to AMI, only a minority received discharge counseling about resuming sexual activity. Lack of counseling was associated with loss of sexual activity 1 year later. Mortality was not significantly elevated among individuals who were sexually active soon after their AMI.

Keywords: acute myocardial infarction, sexuality, quality of life, physician-patient communication

INTRODUCTION

The Translational Research Investigating Underlying Disparities in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients’ Health Status (TRIUMPH) study is a national, multi-site, prospective longitudinal study that followed patients for 12 months after hospitalization for an AMI. We developed a substudy of the TRIUMPH study to specifically investigate sexual activity before and after AMI, the frequency of receipt of post-AMI counseling and its association with sexual activity, and the association of 1 year mortality with sexual activity after AMI.

METHODS

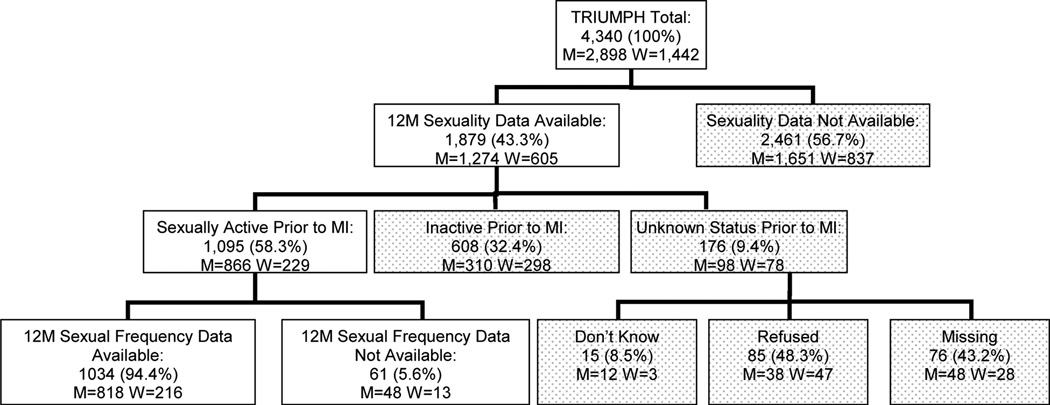

The TRIUMPH study design has been previously described and enrolled 4,340 adult patients (18 years or older) between April 2005 and December 2008 from 24 hospitals across the US.1 This substudy (n=1879; 1274 men and 605 women) was initiated in September 2007 when a sexuality module was added (Figure 1). Inclusion of the sexuality module was prompted by the August 2007 publication of the first comprehensive U.S. population data on, and methods for eliciting, sexual activity and function among middle-age and older adults from the 2005–06 National Social Life, Health and Aging Project (NSHAP).2 The study was conducted with written informed consent and approval of all participating sites’ and investigators’ institutional review boards.

Figure 1.

TRIUMPH Patient Enrollment Diagram

Baseline data were collected through bedside interviews with trained staff within 24 to 72 hours of the index AMI and supplemented with medical record abstractions for the index hospitalization. These include data on patients’ sociodemographic characteristics, depressive symptoms, physical function, and disease severity. Depression was assessed using the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9);3 patients were classified as having moderate depression if their score was ≥ 10.4 Physical functioning was assessed using the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey Physical Composite Score (SF-12 PCS)5, with a higher score representing better physical functioning over the prior 4 weeks. Elements of the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Risk Score (age, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, initial creatinine, congestive heart failure, ST-segment deviation, prior MI, percutaneous coronary intervention, and cardiac enzymes) were prospectively collected at baseline and used to predict 6-month mortality among survivors of acute coronary syndrome; a higher GRACE Risk Score is associated with increased risk.6 Follow-up data were obtained via phone interviews at 1, 6 and 12 months. The sexuality module included a 5-item sexual activity and communication assessment administered by phone interviewers at 1- and 12-months after enrollment.

Sex or sexual activity was defined for study participants, as in the NSHAP study, as “any mutually voluntary activity with another person that involves sexual contact, whether or not intercourse or orgasm occurs.”2 “Pre-AMI sexual activity” was measured using the yes/no question: “Did you have sex or sexual activity at any time in the 12 months prior to having a heart attack?” “Post-AMI sexual activity” was measured at 1 and 12 months using the yes/no question: “Have you had sex or sexual activity since having a heart attack?” Individuals who reported pre-AMI sexual activity were asked: “As compared with how things were in the 12 months before having a heart attack, have you had sex more frequently since your heart attack, with about the same frequency…, or less frequently…” (“don’t know” and “refused” were also coded). To model sexual outcomes at 12 months among those reporting pre-AMI sexual activity, individuals were coded for multivariable regression analysis as: 1) having “loss of sexual activity” if they reported no or less frequent sexual activity at 12 months after the AMI, or 2) the “reference group” if they maintained or reported an increased frequency of sexual activity.

Whether patients received discharge instructions about “when to resume sexual activity” following the index AMI was assessed by patient interview. Discussion with a physician about sex during the period after hospitalization was assessed using the dichotomous “Have you ever discussed sex with your doctor since your heart attack?,” adapting a similar question from the National Social Life, Health and Aging Project, the 2005–06 national benchmark study of sexuality among older U.S. adults.2 Item refusal rates for the sexual activity items ranged from 3.6–5.2%.

Inclusion criteria for analysis required receipt of the sexuality module (all patients who had not yet completed 12 month follow-up or who enrolled in TRIUMPH after the substudy was initiated in September 2007), and completion of the 12 month follow-up interview (n=1879; 1274 men and 605 women). Unadjusted analyses evaluated gender differences in sociodemographic characteristics, health, pre- and post-AMI sexual activity, and communication with a physician about sex, using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables.

Among the subset of individuals who reported pre-AMI sexual activity (n=1095, 866 men and 229 women), gender-specific and combined multivariable regression analysis was used to assess risk factors for loss of sexual activity 12 months after the AMI. The main variables of interest were those that could be modified by the physician, including the discharge instructions and physician discussions about sex. Models were adjusted for age, marital status, the PHQ-9 (dichotomized as ≥10 versus <10), SF-12 PCS, and the GRACE score. Individual co morbidities were not included in the model due to limited sample size. Because the outcome was not rare, we used a modified Poisson regression model with robust standard errors to directly estimate relative risks (RR).7 A random effect for site and site-centered covariates were used to adjust for confounding by site.

Modeling of 12-month sexual activity outcomes used patients’ 12-month recall of receiving discharge instructions and of discussion with a physician about sex. The 12-month recall of receiving discharge instructions was used in lieu of the 1-month variable to maximize the sample size for this analysis. Three hundred and fifty two individuals completed their 1-month interview prior to introduction of the sexuality module into the TRIUMPH study. To assess for possible recall bias on the discharge instruction variable, patients’ 1- and 12- month recall about receipt of discharge instructions were compared with discharge instructions documented in the baseline chart (when available). This analysis was also stratified by gender and sexual activity status.

Survival time, for all patients who completed the sexuality module at 1 month (n=1130), was derived as the interval between the patient's 1-month interview date and death from any cause. Mortality data from any cause was assessed through the Social Security Administration Death Master file. Vital status data were available for over 99% of the cohort based on a matching algorithm for social security number, date of birth, and name. Patients still alive 1 year later were censored. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates8 were calculated among patients who had completed the 1-month sexuality module and were stratified by whether they had been sexually active since their AMI. Log-rank tests were used for comparisons between these groups. Multivariable adjustment for potential confounders was limited given the small number of events (N=40), therefore the multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards models were simply adjusted for baseline physical function (SF-12 PCS). As a validity check, the same analyses were repeated adjusting for the GRACE score, which includes baseline age.

P-values are 2 sided and were evaluated at a significance level of 0.05. All analyses were conducted using SAS software, release 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and R version 2.10.1.9

RESULTS

The TRIUMPH study enrolled 4,340 patients, 1879 of whom received the sexuality module (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics, by gender, are shown in Table 1. Women were older and less likely to be married than men and had higher rates of depression, lower physical functioning scores and higher six-month mortality risk scores than men. Many patients were sexually active both at baseline and at 12 months. Among married women, sexual activity rates were significantly higher, both at baseline (65%) and at 12 months (62%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of TRIUMPH Study Participants Stratified by Gender*

| Overall (N=1879) | Male (N=1274) | Female (N=605) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics measured at baseline | ||||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 59.4 ± 11.7 | 58.6 ± 11.0 | 61.1 ± 12.8 | <0.001 |

| Race | <0.001 | |||

| White/Caucasian | 1330 (71.0%) | 964 (75.9%) | 366 (60.7%) | |

| Black/African American | 405 (21.6%) | 209 (16.5%) | 196 (32.5%) | |

| Other | 138 (7.4%) | 97 (7.6%) | 41 (6.8%) | |

| Married | 1066 (56.9%) | 819 (64.4%) | 247 (41.0%) | <0.001 |

| Depression† | 306 (17.4%) | 177 (14.7%) | 129 (23.2%) | <0.001 |

| SF-12 PCS‡ (mean ± SD) | 43.3 ± 12.2 | 44.8 ± 11.9 | 40.1 ± 12.1 | <0.001 |

| GRACE§ (mean ± SD) | 99.1 ± 27.7 | 97.5 ± 27.4 | 102.5 ± 28.1 | <0.001 |

| Characteristics measured at 12M | ||||

| Sex prior to AMI | 1095 (64.3%) | 866 (73.6%) | 229 (43.5%) | <0.001 |

| Sex since AMI | 1013 (59.6%) | 803 (68.3%) | 210 (40.0%) | <0.001 |

| Received instructions | 787 (42.9%) | 585 (46.8%) | 202 (34.6%) | <0.001 |

| Discussed sex with MD‖ | 439 (33.6%) | 378 (39.1%) | 61 (17.9%) | < 0.001 |

All percentages are calculated excluding missing data, “Don’t know,” and “Refused” response options from the denominator.

Depression defined as a PHQ-9 score of ≥10

Range: 0–100; higher score represents better physical functioning

Range: 1–263; higher score represents higher mortality risk at 6 months post MI

Missingness for this variable (30.4%) was due a skip pattern error in interviews of individuals who reported no sexual activity before or since their MI; missingness did not vary by gender, age, marital or health status. Missingness on this item among those who were sexually active before their MI (the subset included in the multivariable models) was 3%.

People who were sexually active in the year before their AMI were significantly more likely than those who were inactive to report receiving discharge instructions about resuming sex (men: 54% vs. 32%, p < 0.001; women: 58% vs. 23%, p<0.001). Married people were significantly more likely than unmarried people to receive discharge instructions about resuming sexual activity (men: 51% vs. 40%, p<0.001; women: 44% vs. 28%, p<0.001). In the 12 months of follow-up, 38% of sexually active people (41% of sexually active men and 24% of sexually active women, p < 0.001) discussed sex with their physician. Unmarried sexually active patients were significantly less likely to have discussed sex with a physician following their AMI (33% unmarried versus 40% married, p=0.03). This marital status difference was similar among men and women. Patients’ 1- and 12- month recall about receipt of discharge instructions were compared with discharge instructions documented in the baseline chart (when available). There was no difference in recall by gender or sexual activity status.

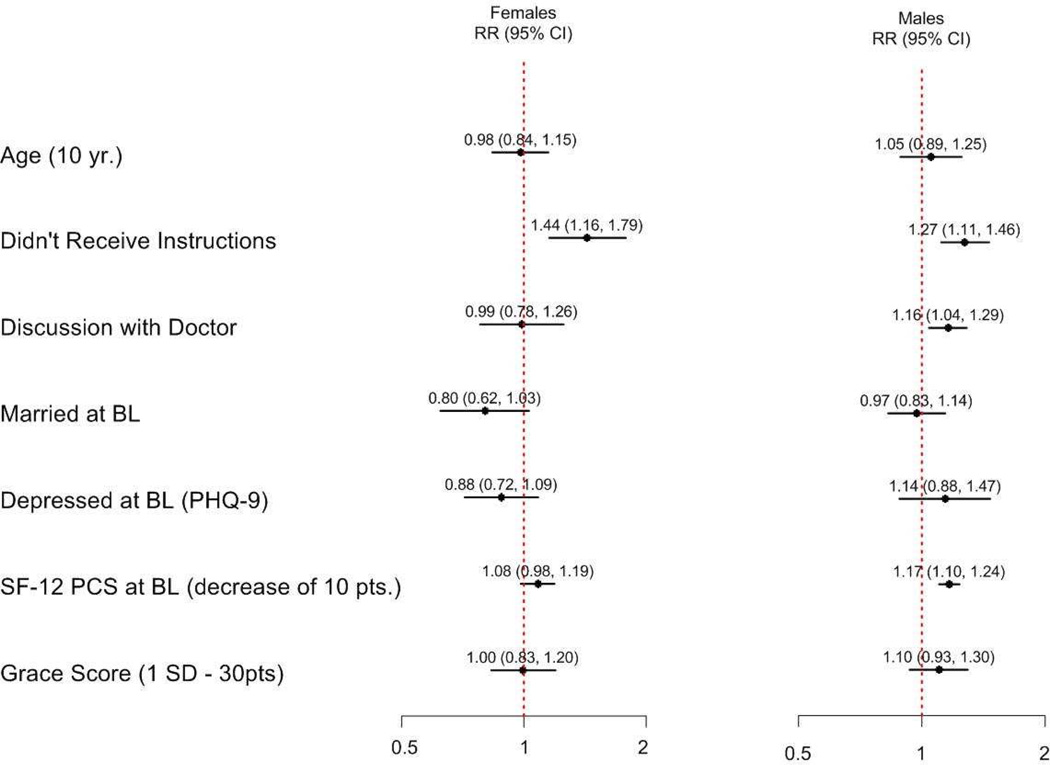

Of patients reporting pre-AMI sexual activity, 48% of men and 59% of women reported less frequent sexual activity in the 12 months after the AMI (Table 2), and 11% of men and 13% of women reported no sexual activity in the subsequent year. Some patients who were sexually inactive in the year prior to their AMI initiated sexual activity in the year following (9.1% of men, 4.0% of women). In the multivariable analysis, significant predictors of loss of sexual activity for men included not receiving discharge instructions about resumption of sex, having a discussion with a doctor about sex since the AMI and a lower baseline SF-12 Physical Function Score. The only significant predictor of loss of sexual activity for women was not having received discharge instructions about sex. Neither age, marital status, depression, or GRACE score were significant predictors of loss of sexual activity in males or females (Figure 2). The multivariable analysis was repeated combining males and females in a single model and no significant interaction between gender and receiving discharge instructions in predicting loss of sexual activity was found.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Sexually Active TRIUMPH Study Participants by Gender and Sexual Frequency at 1Y*

| Male | Female | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual Frequency Since AMI |

More/Same (n=427) |

Less/None (n=391) |

p-value | More/Same (n=88) |

Less/None (n=128) |

p-value |

| Characteristics measured at baseline | ||||||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 55.3 ± 9.9 | 57.0 ± 10.1 | 0.013 | 53.8 ± 11.1 | 53.7 ± 11.1 | 0.954 |

| Race | 0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| White/Caucasian | 349 (82.1%) | 278 (71.5%) | 68 (77.3%) | 69 (54.3%) | ||

| Black/African American | 51 (12.0%) | 79 (20.3%) | 19 (21.6%) | 46 (36.2%) | ||

| Other | 25 (5.9%) | 32 (8.2%) | 1 (1.1%) | 12 (9.4%) | ||

| Married | 309 (72.4%) | 271 (69.5%) | 0.365 | 65 (74.7%) | 72 (56.7%) | 0.007 |

| Depression† | 40 (9.9%) | 54 (14.8%) | 0.036 | 17 (19.8%) | 24 (20.2%) | 0.944 |

| SF-12 PCS‡ (mean ± SD) | 48.5 ± 10.1 | 44.0 ± 12.5 | <0.001 | 44.1 ± 11.8 | 40.1 ± 11.8 | 0.019 |

| GRACE§ (mean ± SD) | 87.8 ± 23.6 | 95.0 ± 25.8 | <0.001 | 86.5 ± 22.8 | 88.5 ± 23.6 | 0.549 |

| Characteristics measured at 12M | ||||||

| Sex since AMI | 426 (100%) | 330 (85.5%) | <0.001 | 85 (97.7%) | 109 (85.2%) | 0.002 |

| Received instructions | 259 (61.2%) | 185 (47.7%) | <0.001 | 60 (69.0%) | 65 (52.4%) | 0.016 |

| Discussed sex w/ MD | 162 (38.5%) | 168 (44.1%) | 0.107 | 25 (28.7%) | 26 (20.3%) | 0.154 |

All percentages are calculated excluding missing data, “Don’t know,” and “Refused” response options from the denominator.

Depression defined as a PHQ-9 score of ≥10

Range: 0–100; higher score represents better physical functioning

Range: 1–263; higher score represents higher mortality risk at 6 months post MI

Figure 2.

Gender Separate Models of Loss of Sexual Activity

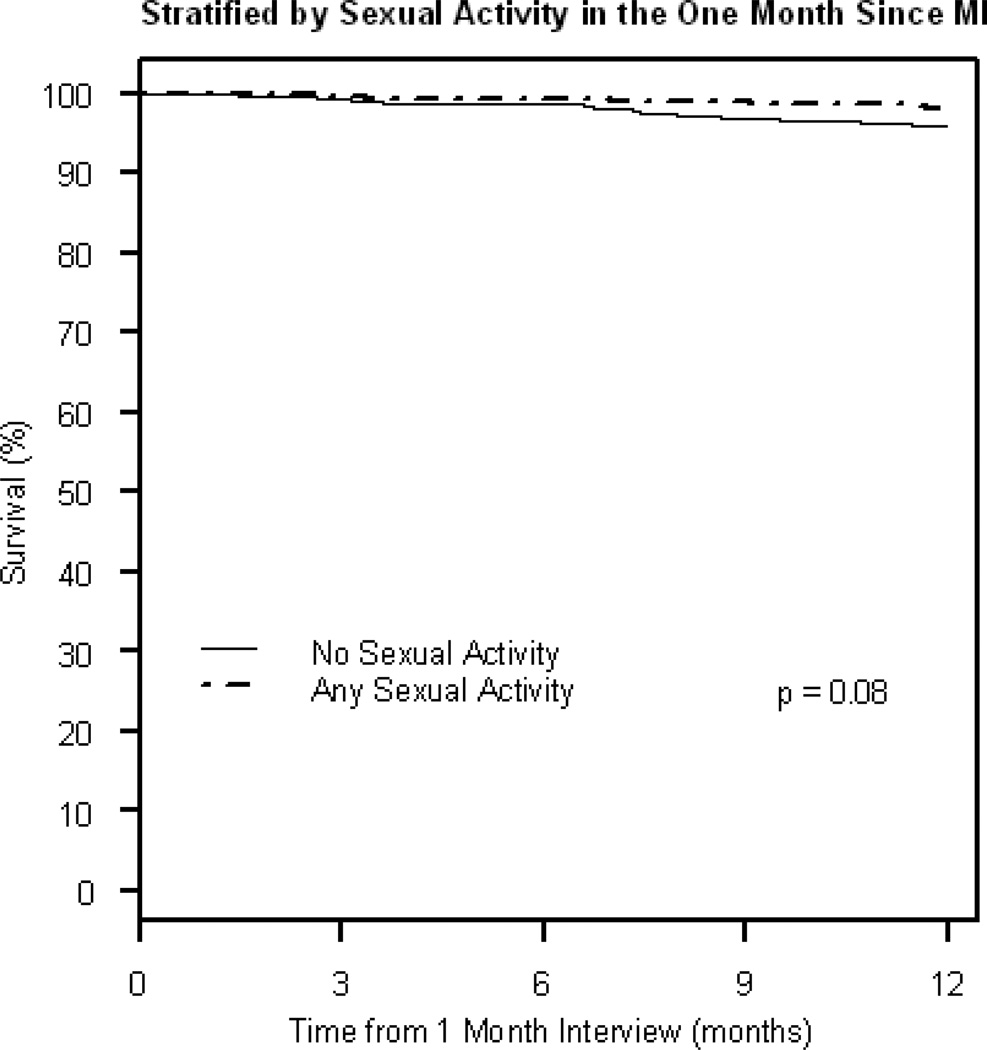

All-cause, unadjusted mortality in the year following the 1-month interview was 2.1% among those who reported sexual activity in the first month after their AMI, as compared to 4.1% among those who were sexually inactive in the first month after their AMI (Figure 3). Adjusting, in separate models, for pre-AMI physical function (Hazard Ratio (HR) inactive vs. active: 1.86, 95% CI 0.80–4.35, p=0.15) or GRACE score (which includes age) (HR: 1.11, 95% CI 0.48–2.54, p=0.81) shows that mortality was not significantly elevated among individuals who were sexually active in the first month after their AMI.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier Plot of All Cause Mortality

DISCUSSION

Although many patients were sexually active before their AMI, only one third of women and fewer than one half of men received discharge instructions about resuming sexual activity. Moreover, about 1 in 10 people who were sexually active before their AMI were not active in the subsequent year. Almost half of men and close to 60% of women were less active than in the period before their AMI. The absence of counseling at hospital discharge about when to resume sexual activity was a significant predictor of loss of activity for both men and women. Mortality was not significantly elevated among individuals who were sexually active in the first month after their AMI.

This study corroborates and extends previous cross-sectional findings about sexual activity among various populations of AMI patients, and expands the field by examining longer-term outcomes in a larger population sample.10–12 Overall, the rates of pre- and post-AMI sexual activity in this population were slightly lower than those reported for the general older adult population; in a 2005–06 nationally generalizable study of community-residing older adults in the US, 69% of men and 43% of women (68% of women with a partner) ages 57–85 were sexually active.2 However, the rate of sexual activity in the 12 months prior to AMI in our cohort was higher (64%) than found in a predominantly male and some what younger cohort of AMI patients enrolled between 1989–93 (53%).10 In the largest comparable longitudinal study of AMI patients, which included only 51 women, Israeli researchers also found a reduction in patients’ sexual frequency and satisfaction three to six months following AMI.13

Although a prior study has found depression to be a significant correlate of sexual problems in men and women with an AMI,14 we found no association with baseline depression, AMI severity, or, in women, physical health status. Instead, our findings point to communication with AMI patients, before hospital discharge, about sexual matters as a potentially critical factor in the preservation or loss of sexual activity. This finding may be explained by the privileged relationship between the cardiologist and patient. The discharging cardiologist has detailed knowledge of the patient’s condition, has provided life-saving care, and is best positioned to advise the patient on the safety of engaging in physical, including sexual, activity.

Prior work has shown that even sexually inactive older adults and those with chronic and life threatening illnesses value sexuality as an important part of life and health.2,15–19 Sexual inactivity before an AMI should not exclude patients from receiving counseling or information from physicians about sex after an AMI. Profiling patients based on prior sexual activity or other factors, including gender, marital or health status, will exclude patients who would benefit from the information and may be particularly problematic for patients of sexual minority groups20 or unmarried people who might be reluctant to disclose their partnership status.21 In this study, nearly half of patients who were married or sexually active prior to AMI received no counseling about resuming sexual activity; among unmarried people who were sexually active, only a third received counseling.

Guidelines for post-AMI care recommend that physicians counsel patients about resuming sexual activity.22,23 The recommendation that “in stable patients without complications, sexual activity with the usual partner can be resumed within 1 week to 10 days”22 has been overlooked in quality assessments of AMI care. Factors like discomfort with or lack of training in the area of sexuality, time constraints, and liability concerns may contribute to physicians’ and other care providers’ reluctance to address sexuality issues.24,25 Our study indicates that the counseling may have an important effect on the likelihood of sexual activity after AMI and that men and women benefit equally from receiving such counseling. AMI care is typically delivered by a multidisciplinary team; additional research is needed to understand the role of both acute care and cardiac rehabilitation nurses, physical therapists, and other providers can play in helping patients optimize sexual outcomes.26

Prior studies and recommendations document concern that sexual activity, particularly with a new partner, or among men with erectile dysfunction, might increase a patient’s risk for first AMI, repeat AMI, or death.10,23,27,28 This study is the first to prospectively assess, in a large population of men and women with AMI, the association of post-AMI sexual activity with 12-month mortality. Although limited by the small number of deaths, our study does not raise any safety concerns.

The study findings should be interpreted in the context of several potential limitations. Introduction of the sexuality module midway through patient enrollment in the TRIUMPH study meant that some patients were lacking 1-month data and limited the scope of sexuality questions we could ask. Similarly, the sexuality module was not included in the baseline (hospital) assessment, which theoretically would provide more accurate report of sexual activity prior to AMI. This study relied on patient self-report, which may have introduced recall bias. Recall about receipt of discharge instructions, as compared to documentation in the medical chart, did not differ by gender or sexual activity in the year following AMI. We did not ask questions about the specific content or quality of instructions received or discussions about sex after AMI. The finding that, among men, discussion about sexual matters with a physician was associated with loss of sexual activity could indicate that men with sexual problems after an AMI were more likely to initiate a discussion with their physician and/or that the discussion deterred them from subsequent sexual activity. This study did not ascertain who initiated discussion about sexual matters, nor did it ascertain specific dimensions of sexual function, such as frequency, type, or intensity of sexual behaviors; this information could be useful to interpret the lack of association with mortality. Additional research is needed to identify the key elements of effective communication about resuming or initiating sexual activity after an AMI and to understand the effects of AMI and AMI care on specific domains of sexual function. In addition, a larger sample size would be needed to model the effects of specific co morbidities, medications, or other post-AMI factors on sexual outcomes after AMI.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding/Support: This project received funding support from the NHLBI (P50 HL077113) and CV Outcomes, Inc., Kansas City, MO. The project described was also supported by Grant Number K23AG032870 and Grant Number 5P30 AG 012857 from the National Institute on Aging. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health.

Role of the Sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors:

Study concept and design: Lindau, Krumholz

Acquisition of data: Spertus, Lindau

Analysis and interpretation of data: Lindau, Gosch, Wroblewski, Abramsohn, Spatz, Chan, Spertus, Krumholz

Drafting of the manuscript: Lindau, Abramsohn, Wroblewski, Gosch

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Wroblewski, Spatz, Spertus, Chan, Gosch, Krumholz

Statistical Analysis: Lindau, Gosch

Obtaining funding: Spertus, Krumholz, Lindau

Administrative, technical or material support: Spertus, Lindau

Supervision: Lindau, Spertus, Krumholz

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Dr. Lindau reported receiving grant support from a Career Development Grant Award, among others (1K23AG032870-01A1K23, 5P30 AG 012857); Ms. Abramsohn and Ms. Wroblewski are also supported by these mechanisms. Dr. Spertus reported support from Cardiovascular Outcomes, Inc., Kansas City, MO (P50 HL77113); Ms. Gosch is also supported by this mechanism. Dr. Krumholz reported support from the Center for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research at Yale University and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (U01 HL105270-02) and discloses that he is the recipient of a research grant from Medtronic, Inc. through Yale University and is chair of a cardiac scientific advisory board for United Health. No other authors reported disclosures.

Dr. John Spertus (Principal Investigator of the TRIUMPH Study) and Ms. Kensey Gosch had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive license (or non exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its licensees, to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in BMJ editions and any other BMJPG products and to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our license (http://resources.bmj.com/bmj/authors/checklists-forms/licence-for-publication).

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by the corresponding Institutional Review Boards of each study site and all patients provided written informed consent.

References

- 1.Arnold SV, Chan PS, Jones PG, Decker C, Buchanan DM, Krumholz HM, Ho PM, Spertus JA. Translational Research Investigating Underlying Disparities in Acute Myocardial Infarction Patients' Health Status (TRIUMPH) Design and Rationale of a Prospective Multicenter Registry. Circulation-Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2011;4:467–476. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.960468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O'Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eagle KA, Lim MJ, Dabbous OH, Pieper KS, Goldberg RJ, Van de Werf F, Goodman SG, Granger CB, Steg PG, Gore JM, Budaj A, Avezum A, Flather MD, Fox KAA. A validated prediction model for all forms of acute coronary syndrome: Estimating the risk of 6-month postdischarge death in an international registry. JAMA. 2004;291:2727–2733. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zou GY. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaplan E, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;47:583–621. [Google Scholar]

- 9.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muller JE, Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Sherwood JB, Tofler GH. Triggering myocardial infarction by sexual activity: Low absolute risk and prevention by regular physical exertion. JAMA. 1996;275:1405–1409. doi: 10.1001/jama.275.18.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drory Y, Kravetz S, Hirschberger G. Sexual activity of women and men one year before a first acute myocardial infarction. Cardiology. 2002;97:127–132. doi: 10.1159/000063328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamilton GA, Seidman RN. A comparison of the recovery period for women and men after an acute myocardial infarction. Heart Lung. 1993;22:308–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drory Y, Kravetz S, Weingarten M. Comparison of sexual activity of women and men after a first acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85:1283–1287. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)00756-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kriston L, Guenzler C, Agyemang A, Bengel J, Berner MM. Effect of sexual function on health-related quality of life mediated by depressive symptoms in cardiac rehabilitation. Findings of the SPARK Project in 493 patients. J Sex Med. 2010;7:2044–2055. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill E, Sandbo S, Abramsohn E, Makelarski J, Wroblewski K, Wenrich E, McCoy S, Temkin S, Yamada S, Lindau S. Assessing gynecologic and breast cancer survivors’ sexual health care needs. Cancer. 2011;117:2643–2651. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindau S, Surawska H, Paice J, Baron S. Communication about sexuality and intimacy in couples affected by lung cancer and their clinical-care providers. Psychooncology. 2011;20:179–185. doi: 10.1002/pon.1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindau ST, Gavrilova N. Sex, health, and years of sexually active life gained due to good health: Evidence from two US population based cross sectional surveys of ageing. Br Med J. 2010;340 doi: 10.1136/bmj.c810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindau ST, Gavrilova N, Anderson D. Sexual morbidity in very long term survivors of vaginal and cervical cancer: A comparison to national norms. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106:413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindau ST, Tang H, Gomero A, Vable A, Huang ES, Drum ML, Qato DM, Chin MH. Sexuality among middle-aged and older adults with diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes: A national, population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2202–2210. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stein G, Bonuck K. Physician–patient relationships among the lesbian and gay community. J Gay Lesbian Med Assoc. 2001;3:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Politi MC, Clark MA, Armstrong G, McGarry KA, Sciamanna CN. Patient-provider communication about sexual health among unmarried middle-aged and older women. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:511–516. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0930-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson J, Adams C, Antman E, Bridges C, Califf R, Casey DJ, Chavey WI, Fesmire F, Hochman J, Levin T, Lincoff A, Peterson E, Theroux P, Wenger N, Wright R. ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non–ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction): developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, American College of Physicians, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:e1–e157. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antman E, Anbe D, Armstrong P, Bates E, Green L, Hand M, Hochman J, Krumholz H, Kushner F, Lamas G, Mullany C, Ornato J, Pearle D, Sloan M, Smith SJ. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction) Circulation. 2004;110:e82–e293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gott M, Hinchliff S, Galena E. General practitioner attitudes to discussing sexual health issues with older people. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:2093–2103. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaarsma T, Stromberg A, Fridlund B, De Geest S, Martensson J, Moons P, Norekval TM, Smith K, Steinke E, Thompson DR. Sexual counselling of cardiac patients: Nurses' perception of practice, responsibility and confidence. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2010;9:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnason S, Steinke E, Mosack V, Wright DW. Comparison of cardiac rehabilitation and acute care nurses perceptions of providing sexual counseling for cardiac patients. J Cardiopulmonary Rehab and Prev. 2011;31:157–163. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181f68aa6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dahabreh IJ, Paulus JK. Association of episodic physical and sexual activity with triggering of acute cardiac events. JAMA. 2011;305:1225–1233. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kostis JB, Jackson G, Rosen R, Barrett-Connor E, Billups K, Burnett AL, Carson C, Cheitlin M, Debusk R, Fonseca V, Ganz P, Goldstein I, Guay A, Hatzichristou D, Hollander JE, Hutter A, Katz S, Kloner RA, Mittleman M, Montorsi F, Montorsi P, Nehra A, Sadovsky R, Shabsigh R. Sexual dysfunction and cardiac risk (The Second Princeton Consensus Conference) American Journal of Cardiology. 2005;96:313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]