Abstract

Adolescence is a time in which individuals are particularly likely to engage in health-risk behaviors, with marijuana being the most prevalent illicit drug used. Perceptions of others’ use (i.e., norms) have previously been found to be related to increased marijuana use. Additionally, low refusal self-efficacy has been associated with increased marijuana consumption. This cross-sectional study examined the effects of normative perceptions and self-efficacy on negative marijuana outcomes for a heavy using adolescent population. A structural equation model was tested and supported such that significant indirect paths were present from descriptive norms to marijuana outcomes through self-efficacy. Implications for prevention and intervention with heavy using adolescent marijuana users are discussed.

Keywords: marijuana, adolescent substance abuse, social norms, social learning theory

Marijuana is the most widely used illicit drug among adolescents (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2008). Marijuana dependence develops in approximately 14–17% of adolescents who ever use it (Anthony, 2006; Hall & Degenhardt, 2007), and may lead to an increased risk of other illegal drug use and depressive symptoms (Hall & Degenhardt, 2007). Understanding of the factors influencing adolescents’ substance use may aid in the prevention of harmful use patterns. The current study examined the relationships between perceived norms and marijuana use and tested a model in which the influence of perceived norms is mediated by self-efficacy for avoiding use.

Previous research has demonstrated that social influences are strongly associated with risk-related behaviors among young adults. Most college students overestimate the degree to which their peers use marijuana (Perkins et al., 1999; Wolfson, 2000). In turn, perceptions of others’ marijuana use have been associated with more frequent use and drug-related consequences (Kilmer et al., 2006; Page & Roland, 2004; Simons, Neal, & Gaher, 2006; White et al., 2006). Injunctive norms (i.e., perceived approval of marijuana use by one’s peers) and descriptive norms (i.e., perceived frequency of marijuana use by one’s peers) have been found to uniquely predict marijuana use (Neighbors, Geisner, & Lee, 2008).

One mechanism through which social norms may influence marijuana use is by decreasing self-efficacy for avoiding use. Refusal self-efficacy, or one’s confidence in being able to avoid using marijuana, is one of the strongest and most consistent predictors of future marijuana use in trials of treatments for adult marijuana dependence (e.g., Litt, Kadden, & Stephens, 2005; Lozano, Stephens & Roffman, 2006; Stephens, Wertz, and Roffman, 1995). Theoretically, self-efficacy is a final common pathway for the effects of various personal, social, and affective influences on behavior (Bandura 1977; 1997). Support for this proposition has been found in the treatment literature for marijuana. In one study (Stephens et al., 1995), posttreatment refusal self-efficacy partially mediated the influence of a variety of social and personal influences on marijuana use at future follow-ups. In another, Litt and colleagues (2005) showed that postttreatment refusal self-efficacy mediated the differential effects of treatment condition on marijuana use at later follow-ups.

The perception that marijuana use is normative is likely to undermine refusal self-efficacy. Modeling of behavior is one of the strongest influences on self-efficacy judgments (Bandura, 1997) and perceived normative use symbolically indicates the presence of multiple models for using marijuana. It may also raise the bar for successfully refusing use by representing increased social pressure, one of the most common high risk situations for drug use posttreatment (Marlatt & Gordon, 1985). Thus, environments where substance use is perceived as high in prevalence and approval are likely to reduce confidence in ability to resist temptations to use. Low confidence in one’s ability to resist is, in turn, likely to be associated with more use.

Current Study

The present research was designed to extend previous research on the relationship between perceived social norms and marijuana use in a heavy-using adolescent population. To our knowledge, no studies to date have evaluated the effects of normative perceptions and self-efficacy in adolescent marijuana users. We expected that positive associations would emerge between injunctive and descriptive norms and negative marijuana outcomes, and that refusal self-efficacy would be negatively associated with negative outcomes. Further, we predicted that refusal self-efficacy would mediate the effects of both injunctive and descriptive norms on negative marijuana outcomes.

Method

Study Design

This is secondary data analysis of data collected as part of a randomized controlled treatment trial for adolescent marijuana users (Walker et al., in press). Adolescents in public high schools in Seattle, Washington were recruited to participate. Of the 619 screened participants, 320 were eligible (51.7%) and 310 of those chose to participate (96.9%). Inclusion criteria were: (a) 14–19 years of age; (b) enrolled in 9th through 12th grade; and (c) reported using marijuana on 9 or more days in the past 30. The majority (98%) of ineligible participants had not used marijuana on at least 9 days in the past month. Only 12-month data were utilized because it is the only timepoint at which all of the variables were assessed. Of the 205 participants who were eligible to complete the 12-month follow-up, 25 (12.2%) were lost to attrition. Thus, the present sample is based on 180 participants. All of the study procedures were conducted in accordance with IRB requirements. Details of the parent trial and intervention content are available elsewhere (Walker, et al., in press). Overall reductions were evident among participants in all conditions but there were no sustained differences between conditions at the 12-month assessment.

Participants and procedures

These analyses included 180 participants for whom 12-month follow-up data were available. The mean age was 16.0 years (SD = 1.24). Participants were mostly male (n = 120, 67%) and Caucasian (n = 120, 67%) with 14% multiracial, 11% African American, 3% Asian and Pacific Islander, 2% Hispanic or Latino, and 3% other. Fifty percent (n = 90) of participants were in the 9th or 10th grades and 50% (n = 90) were in the 11th or 12th grades.

An Audio-Computer-Assisted Self-Interviewing (A-CASI) program was used at baseline and at the 12-month follow-up to collect assessment data. Participants received gift cards at completion of the 12-month follow-up assessment ($40).

Measures

Negative marijuana outcomes

Marijuana outcomes included frequency of use, abuse symptoms, and dependence symptoms. Frequency of marijuana use was assessed by asking, “During the past 60 days, how many days did you use any kind of marijuana/hashish?” Symptoms of marijuana abuse and dependence, as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (DSM-IV), were assessed by adapting questions from the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs-I (GAIN-I; Dennis et al., 1998). The 90-day assessment time frame used by the GAIN was modified in this study to focus on the past 60 days. The Substance Abuse Index (SAI) and Substance Dependence Scale (SDS) of the GAIN-I were used to assess abuse and dependence symptoms. These included 17 items from the GAIN-I, which were used to assess the four DSM-IV criteria for abuse and the seven DSM-IV criteria for dependence. Seven items assessed symptoms of abuse and 10 items assessed symptoms of dependence. Participants were scored as having met a criterion if they positively endorsed any question assessing that criterion. Scores were based on the total numbers of abuse (0 – 4) and dependence criteria (0 – 7) met, given concerns regarding the meaningful distinction of abuse and dependence among adolescents as defined by the DSM-IV (Winters, Latimer, & Stinchfield, 2002; Chung, Martin, Winters, Cornelius, & Langenbucher, 2004). Reliability was .81.

Social norms

The norms assessed in the current study focus on perceptions and not actual use. Specifically, the items ask about the individuals’ perceptions of their close friends’ approval of their using marijuana (i.e., injunctive norms) and of their close friends’ marijuana use (i.e., descriptive norms). Injunctive norms were assessed by three items regarding participants’ perceptions of their friends’ approval of their using marijuana. Specifically, participants were asked, “How do you think your close friends feel (or would feel) about you… (trying marijuana once or twice, smoking marijuana occasionally, smoking marijuana regularly)?” Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disapprove to 5 = Strongly Approve), and internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was .92. Descriptive norms were measured by asking, “How often do you think your friends typically use marijuana?” Responses were assessed on a 9-point Likert scale (0 = Never to 8 = Every Day).

Self-efficacy

The Self-Efficacy Scale (SES; Stephens et al., 1993; 1995) is a 20-item questionnaire used to assess self-efficacy for resisting marijuana use in a variety of interpersonal and intrapersonal situations. Participants were asked, “How confident are you that you could resist the temptation to smoke marijuana if you were… (sample questions include “at a party where people were smoking marijuana”, “feeling depressed or worried”?). Responses were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all confident to 7 = Very confident). This scale has previously been shown to predict outcomes both before and after treatment (Stephens et al., 1995). The overall alpha in the current study was .94.

Results

Descriptive information

Students reported using marijuana on an average of 33.6 of the past 60 days (SD = 22.36; range 0–60) and endorsed an average of 3.83 marijuana-related abuse/dependence symptoms (SD = 2.89; range 0–11). Within the sample, 35.6% met criteria for DSM-IV (past year) marijuana abuse and 37.2% met criteria for marijuana dependence. Table 1 provides means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations for injunctive norms, descriptive norms, self-efficacy, the number of days of marijuana use, and abuse/dependence symptoms. In accord with the hypotheses, negative marijuana outcomes were positively associated with perceived injunctive and descriptive norms for friends, and negatively associated with refusal self-efficacy.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Zero-Order Correlations for Descriptive and Injunctive Norms, Self-Efficacy, Marijuana Use, and Abuse and Dependence Symptoms

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Descriptive Norms | 6.50 | 1.72 | - | ||||

| 2. Injunctive Norms | 3.85 | 0.98 | .47*** | - | |||

| 3. Refusal Self-efficacy | 4.20 | 1.44 | −.31*** | −.20** | - | ||

| 4. Days used (past 60) | 33.63 | 22.36 | .49*** | .39*** | −.53*** | - | |

| 5. Abuse/Dependence symptoms | 3.83 | 2.89 | .26*** | .17* | −.55*** | .44*** | - |

Note. Possible response ranges were as follows: descriptive norms (0–8); injunctive norms (1–5); refusal self-efficacy (1–7); days used (past 60 days; 0–60); abuse/dependence symptoms (1–11). Ns range from 175–180.

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05

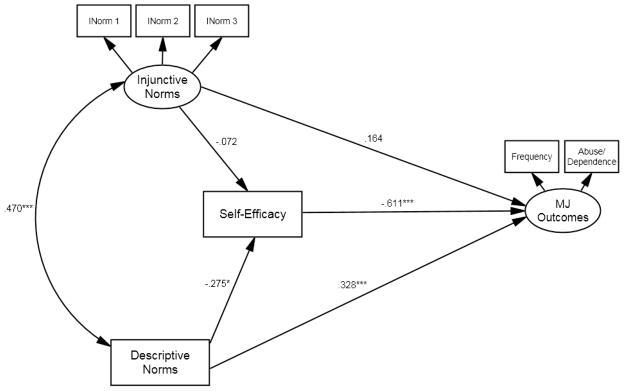

SEM model

Based on previous literature, we proposed that social norms would have direct effects on negative marijuana outcomes and indirect effects through self-efficacy. Moreover, we expected that associating with heavier using friends (descriptive norms) and perceiving friends as more approving of marijuana use (injunctive norms) would be associated with lower confidence in the ability to resist the temptation to smoke marijuana (self-efficacy), which would in turn be associated with more frequent use and greater symptoms of abuse and dependence. The SEM model included latent variables for injunctive norms and marijuana outcomes and measured variables for descriptive norms and self-efficacy. Intervention condition, sex, ethnicity (Caucasian versus non-Caucasian), and age were included as covariates. The resulting model was fit using AMOS 18.0. Parameters were estimated using full information maximum likelihood estimation (Shafer & Graham, 2002). In this heavy using sample, descriptive norms, injunctive norms, and frequency of use were negatively skewed. Overall model fit was acceptable, χ2(55) = 37.25; χ2/df = 0.68; NFI = .947; TLI = .941; CFI = .976; RMSEA = .062. Standard errors of parameter estimates were bootstrapped with 2000 samples drawn to account for non-normality of the data. Table 2 presents parameter estimates and bootstrapped standard errors for model paths.

Table 2.

Model Paths: Parameter Estimates and Bootstrapped Standard Errors

| Model path | β | B | S.E. (B) | C.R. | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Injunctive norm | → | Self-efficacy | −0.072 | −0.115 | 0.142 | −0.81 | 0.418 |

| Descriptive norm | → | Self-efficacy | −0.275 | −0.231 | 0.093 | −2.48 | 0.013 |

| Injunctive norm | → | MJ outcomes | 0.164 | 3.04 | 1.873 | 1.62 | 0.105 |

| Descriptive norm | → | MJ outcomes | 0.328 | 3.205 | 0.905 | 3.54 | 0.000 |

| Self-efficacy | → | MJ outcomes | −0.611 | −7.097 | 0.946 | −7.50 | 0.000 |

| Intervention | → | Injunctive norm | 0.03 | 0.055 | 0.138 | 0.40 | 0.689 |

| Intervention | → | Descriptive norm | 0.053 | 0.183 | 0.255 | 0.72 | 0.472 |

| Intervention | → | Self-efficacy | 0.056 | 0.162 | 0.207 | 0.78 | 0.435 |

| Intervention | → | MJ outcomes | 0.013 | 0.433 | 2.359 | 0.18 | 0.857 |

| Age | → | Injunctive norm | 0.057 | 0.042 | 0.06 | 0.70 | 0.484 |

| Age | → | Descriptive norm | 0.157 | 0.217 | 0.104 | 2.09 | 0.037 |

| Age | → | Self-efficacy | 0.035 | 0.041 | 0.083 | 0.49 | 0.624 |

| Age | → | MJ outcomes | −0.039 | −0.526 | 0.95 | −0.55 | 0.582 |

| Gender | → | Injunctive norm | −0.063 | −0.122 | 0.161 | −0.76 | 0.447 |

| Gender | → | Descriptive norm | −0.175 | −0.636 | 0.293 | −2.17 | 0.030 |

| Gender | → | Self-efficacy | 0.052 | 0.159 | 0.218 | 0.73 | 0.465 |

| Gender | → | MJ outcomes | −0.034 | −1.194 | 2.548 | −0.47 | 0.638 |

| Ethnicity | → | Injunctive norm | 0.194 | 0.372 | 0.157 | 2.37 | 0.018 |

| Ethnicity | → | Descriptive norm | 0.048 | 0.174 | 0.29 | 0.60 | 0.549 |

| Ethnicity | → | Self-efficacy | −0.023 | −0.071 | 0.237 | −0.30 | 0.764 |

| Ethnicity | → | MJ outcomes | 0.072 | 2.564 | 2.562 | 1.00 | 0.317 |

Note. C.R. = Critical ratio

All hypothesized paths related to descriptive norms were significant. In contrast, injunctive norms were not uniquely related to either self-efficacy or marijuana outcomes. Figure 1 provides a summary of the model. Covariates are not included in the figure for the sake of clarity but are included in Table 2. A significant direct path predicting marijuana outcomes was evident for descriptive norms. Self-efficacy was strongly and negatively associated with marijuana outcomes. Descriptive norms significantly predicted lower refusal self-efficacy, and refusal self-efficacy significantly predicted fewer abuse and dependence symptoms. Mediation analyses were performed to formally evaluate self-efficacy as a mediator of injunctive and descriptive norms predicting negative marijuana outcomes. Results indicated a significant indirect path from descriptive norms to marijuana outcomes through self-efficacy, Z = 2.35, p = .02. There was not a significant indirect path from injunctive norms to marijuana outcomes, Z = .81, p = .42. Thus, self-efficacy mediated the relationship between descriptive but not injunctive norms and marijuana outcomes.

Figure 1.

Refusal self-efficacy partially mediates the effect of descriptive norms on negative marijuana outcomes, but not the effect of injunctive norms on negative marijuana outcomes.

Note. * p < .05 *** p < .001.

Discussion

Overall support for study hypotheses was mixed. We expected positive associations between injunctive and descriptive norms and marijuana outcomes and that refusal self-efficacy would be negatively associated with negative outcomes. These expectations were confirmed by correlations among the variables. Consistent with previous research in other substance use domains (Kilmer et al., 2006; Neighbors et al., 2008), bivariate correlations demonstrated both descriptive and injunctive norms were uniquely and positively associated with use. Also, consistent with previous work, self-efficacy was negatively associated with marijuana outcomes (Lozano et al., 2006; Stephens et al., 1993). It should be noted that the current research utilized perceived norms as actual normative data from the adolescents’ close friends were not obtained.

We further predicted that refusal self-efficacy would mediate the effects of both injunctive and descriptive norms on negative marijuana outcomes. We found support for self-efficacy as a partial mediator of the association between descriptive norms and negative marijuana outcomes. We found no support for self-efficacy as a mediator of the association between injunctive norms and negative marijuana outcomes.

Studies of adolescents demonstrate that self-efficacy judgments meaningfully predict subsequent behavior (Bandura, 1997). Refusal self-efficacy has been hypothesized as a mediator of environmental influences and behavior in past research (e.g., Maisto et al., 1999), and the current research evaluated self-efficacy as a mediator of social norms and negative marijuana outcomes. In the model we found direct and indirect paths from descriptive norms to marijuana outcomes through self-efficacy. We did not find the same effects for injunctive norms. At first glance, this may seem counter-intuitive because one might think that perceiving that friends approve of marijuana use would affect one’s self-efficacy for resisting as much as or more than generally knowing that friends use. This may be because descriptive norms are more closely related to actual use whereas injunctive norms are inherently subjective. Moreover, resisting use when others are presently using is likely to be more difficult than when thinking about others’ approval in the absence of actual use. In fact, one of the key limitations of this research is that the descriptive norms measure may be assessing actual peer use rather than perceptions of use. Little work has examined the accuracy of descriptive norms among heavy using adolescent marijuana users. Clarification of this issue in future research may have direct implications on intervention strategies, which may accordingly vary in emphasis on correcting normative misperceptions versus building self-efficacy and refusal skills.

Results suggest two primary implications for intervention. First, findings reiterate the importance of supporting or increasing self-efficacy (Miller & Rollnick, 2002; Litt et al., 2005; Stephen et al., 1995). Second, the present findings build on previous research in suggesting that strategies designed to reduce perceived descriptive norms may be effective in reducing marijuana use (Kilmer et al., 2006; Neighbors et al., 2008). Social norms interventions have been extensively evaluated in targeting young adult drinking but have not been systematically evaluated with marijuana use (Lewis & Neighbors, 2006). The present results suggest that strategies which effectively reduce perceived descriptive norms for marijuana use may have direct effects on marijuana outcomes as well as indirect effects on marijuana use by enhancing self-efficacy.

The study sample included heavy marijuana users who were participants in a larger intervention trial (Walker et al., in press). Overall, participants began the trial using on approximately 39 of the previous 60 days and reporting an average of nearly five symptoms of abuse and dependence. This level of use is similar to that described in treatment populations (e.g., Dennis, et al., 2004). These two outcomes were reduced by approximately 14% and 21%, respectively, by the 12-month follow-up. In the parent trial, two conditions (Motivational Enhancement Therapy and Education) were associated with reduced use at the three-month follow-up, relative to a delayed assessment control group. The MET condition reduced marijuana use significantly more than the Education condition at the 3-month follow-up, but differences between groups were not found for marijuana problems or abuse/dependence symptoms. Reductions in use were sustained at the 12-month follow-up but no longer were different between conditions (Walker et al., in press) suggesting the need for a more intensive intervention or the addition of booster sessions to sustain effects over the long-term. These findings in conjunction with those of an earlier pilot study (Walker, et al., 2006) also raise questions about the impact of assessment on use. Participants in both conditions rated the quality of the sessions and satisfaction with the counselor similarly high, which may also account for the lack of group differences.

Although this investigation adds to the literature on social norms, self-efficacy, and marijuana use among a heavy using adolescent sample, there are limitations to consider and ideas for further research. Evaluation of causal models with cross-sectional data is tenuous because alternative models can be specified that will provide the same fit indices. For example A → B → C cannot be distinguished from C → B → A in cross-sectional data. In the contrasting model, it is plausible marijuana use promotes association with others who smoke more and approve more of smoking. In addition, self-efficacy may be influenced directly by their peer network, rather than erroneous normative beliefs. Furthermore, low self-efficacy and affiliation with heavy-using peers may be symptoms rather than causes of a marijuana use problem. Thus, we cannot rule out alternative models. Nevertheless, the cross-sectional data in this study are consistent with the proposed model. The present results are also consistent with previous studies where self-efficacy has been found to mediate intervention effects on subsequent marijuana use (Litt et al., 2005) and findings that self-efficacy is associated with subsequent reductions in frequency of marijuana use, controlling for previous marijuana use, temptation, coping, perceived stress, and contact with other users.

The use of self-report measures in the absence of biochemical verification is a limitation. However, confidentiality of responses was assured and no negative consequences resulted from disclosing use. Previous research suggests that self-report of substance use behavior is generally accurate when these conditions are met (Babor, Steinberg, Anton, & Del Boca, 2000; Chermack, Singer, & Beresford, 1998). In sum, the present research provides an important step in understanding how self-efficacy fits in the context of social influences on use among heavy using adolescent marijuana smokers.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant R01DA014296 funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and awarded to Roger A. Roffman.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/adb.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Assocation. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Assocation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Annis HM, Davies CS. Assessment of expectancies in alcohol-dependent clients. In: Donovan D, Marlatt GA, editors. Assessment of Addictive Behaviors. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1988. pp. 84–111. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Steinberg K, Anton R, Del Boca F. Talk is cheap: Measuring drinking outcomes in clinical trials. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:55–63. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavior change. Psychological Review. 1977a;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. New York: General Learning Press; 1977b. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs. NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal SC, Evans RI, Nash SG, Getz JG. Global positive expectancies of the self and adolescents’ substance use avoidance: Testing a social influence meditational model. Journal of Personality. 2002;70:421–442. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.05010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chermack ST, Singer K, Beresford TP. Screening for alcoholism among medical inpatients: How important is corroboration of patient self-report? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:1393–1398. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Martin CS, Winters KC, Cornelius JR, Langenbucher JW. Limitations in the Assessment of DSM-IV Cannabis Tolerance as an Indicator of Dependence in Adolescents. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2004;12:136–146. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.2.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 3. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Davis LJ, Hoffmann NG, Morse RM, Luehr JG. Substance Use Disorder Diagnostic Schedule (SUDDS): The equivalence and validity of a computer-administered and interview-administered format. Alcoholism. 1992;16:250–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1992.tb01371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML. Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN) manual: Administration, scoring and interpretation. Lighthouse Publications; Bloomington, IL: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Godley S, Diamond G, Tims F, Babor T, Donaldson J, Liddle H, Titus JD, Kaminer Y, Webb C, Hamilton N, Funk R. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) Study: Main findings from two randomized trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27:197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Gibertini M. Self-efficacy and the stages of self-change of smoking. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1985;9:181–200. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Tildesley E, Duncan SC, Hops H. The consistency of family and peer influences on the development of substance use in adolescence. Addiction. 1995;90:1647–1660. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1995.901216477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Hays RD. On becoming involved with drugs: Modeling adolescent drug use over time. Health Psychology. 1992;11:377–385. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.6.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdman H, Klein Marjorie H, Greist JH. The reliability of a computer interview for drug use/abuse information. Behavior Research Methods & Instrumentation. 1983;15:66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Galvan A, Hare T, Voss H, Glover G, Casey BJ. Risk-taking and the adolescent brain: Who is at risk? Developmental Science. 2007;10:8–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2006.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. College students and adults ages 19–45 (NIH Publication No 08-6418B) II. Bathesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2008. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and Protective Factors for Alcohol and Other Drug Problems in Adolescence and Early Adulthood - Implications for Substance-Abuse Prevention. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:64–105. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilmer JR, Walker DD, Lee CM, Palmer RS, Mallett KA, Fabiano P, Larimer ME. Misperceptions of college student marijuana use: Implications for prevention. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:277–281. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korcuska JS, Thombs DL. Gender role conflict and sex-specific drinking norms: Relationships to alcohol use in undergraduate women and men. Journal of College Student Development. 2003;44:204–216. [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Geisner IM, Lewis MA, Neighbors C, Larimer ME. Social motives and the interaction between descriptive and injunctive norms in college student drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:714–721. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Social norms approaches using descriptive drinking norms education: A review of the research. Journal of American College Health. 2006;54:213–218. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.4.213-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Kadden RM, Stephens RS. Coping and self-efficacy in marijuana treatment: Results from the Marijuana Treatment Project. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:1015–1025. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano BE, Stephens RS, Roffman RA. Abstinence and moderate use goals in the treatment of marijuana dependence. Addiction. 2006;101:1589–1597. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, Cole DA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:23–44. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Maisto SA, O’Farrell TJ. End-of-treatment self-efficacy, aftercare, and drinking outcomes of alcoholic men. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 1993;17:1078–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Carey KB, Bradizza CM. Social learning theory. In: Leonard KE, Blane HT, editors. Psychological Theories of Drinking and Alcoholism. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 106–63. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Gordon JR. Relapse prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. New York: Guilford Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Martins SS, Storr CL, Alexandre PK, Chilcoat HD. Do adolescent ecstasy users have different attitudes towards drugs when compared to marijuana users? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;94:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Best KM, Garmezy N. Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2:425–444. [Google Scholar]

- McElrath K. A comparison of two methods for examining inmates’ self-reported drug use. International Journal of the Addictions. 1994;29:517–524. doi: 10.3109/10826089409047397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Geisner IM, Lee CM. Perceived marijuana norms and social expectancies among entering college student marijuana users. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:433–438. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page RM, Roland M. Misperceptions of the prevalence of marijuana use among college students: Athletes and non-athletes. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2004;14:61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW, Meilman PW, Leichliter JS, Cashin JR, Presley CA. Misperceptions of the norms for the frequency of alcohol and other drug use on college campuses. Journal of American College Health. 1999;47:253–258. doi: 10.1080/07448489909595656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petraitis J, Flay BR, Miller TQ. Reviewing theories of adolescent substance use: organizing pieces in the puzzle. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:67–86. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimal RN, Real K. Understanding the influence of perceived norms on behaviors. Communication Theory. 2003;13:184–203. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:1063–1078. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, Maggs JL, Hurrelman K. Health risks and developmental transitions during adolescence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Shafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Neal DJ, Gaher RM. Risk for marijuana-related problems among college students: An application of zero-inflated negative binomial regression. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32:41–53. doi: 10.1080/00952990500328539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Wertz JS, Roffman RA. Predictors of marijuana treatment outcomes: The role of self-efficacy. Journal of Substance Abuse. 1993;5:341–354. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(93)90003-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens RS, Wertz JS, Roffman RA. Self-efficacy and marijuana cessation: A construct validity analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:1022–1031. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.6.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart EA, Green KM. Using full matching to estimate causal effects in nonexperimental studies: Examining the relationship between adolescent marijuana use and adult outcomes. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:395–406. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, Lindberg LD, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Zundert RM, Engels RC, Van Den Eijnden RJ. Adolescent smoking continuation: Reduction and progression in smoking after experimentation and recent onset. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;29:435–447. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DD, Roffman RA, Stephens RS, Wakana K, Berghuis J. Motivational Enhancement Therapy for Adolescent Marijuana Users: A Preliminary Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:628–632. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker DD, Stephens RS, Roffman R, Towe S, DeMarce J, Lozano B, Berg B. Randomized controlled trial of motivational enhancement therapy with adolescent marijuana users: A further test of the teen marijuana check-up. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1037/a0024076. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb PM, Zimet GD, Fortenberry JD, Blythe MJ. Comparability of a computer-assisted versus written method for collecting health behavior information from adolescent patients. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;24:383–388. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, McMorris BJ, Catalano RF, Fleming CB, Haggerty KP, Abbott RD. Increases in alcohol and marijuana use during the transition out of high school into emerging adulthood: The effects of leaving home, going to college, and high school protective factors. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:810–822. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Latimer WW, Stinchfield R. Clinical issues in the assessment of adolescent alcohol and other drug use. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40:1443–1456. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson S. Students’ estimates of the prevalence of drug use: Evidence for a false consensus effect. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:295–298. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]