Abstract

Background

A powerful approach to understanding complex processes such as aging is to use model organisms amenable to genetic manipulation, and to seek relevant phenotypes to measure. Caenorhabditis elegans is particularly suited to studies of aging, since numerous single-gene mutations have been identified that affect its lifespan; it possesses an innate immune system employing evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways affecting longevity. As worms age, bacteria accumulate in the intestinal tract. However, quantitative relationships between worm genotype, lifespan, and intestinal lumen bacterial load have not been examined. We hypothesized that gut immunity is less efficient in older animals, leading to enhanced bacterial accumulation, reducing longevity. To address this question, we evaluated the ability of worms to control bacterial accumulation as a functional marker of intestinal immunity.

Results

We show that as adult worms age, several C. elegans genotypes show diminished capacity to control intestinal bacterial accumulation. We provide evidence that intestinal bacterial load, regulated by gut immunity, is an important causative factor of lifespan determination; the effects are specified by bacterial strain, worm genotype, and biologic age, all acting in concert.

Conclusions

In total, these studies focus attention on the worm intestine as a locus that influences longevity in the presence of an accumulating bacterial population. Further studies defining the interplay between bacterial species and host immunity in C. elegans may provide insights into the general mechanisms of aging and age-related diseases.

Background

Aging results in alterations in multiple physiologic processes [1]. The identification and measurement of markers of aging to predict lifespan is a major element of aging research [2]. Because the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans is genetically tractable, it has become a major model organism for studies of aging [3-5], neurobiology [6,7], cell cycle [8], chemosensation [9], microbial pathogenesis, and host defenses [10-12]. C. elegans is particularly suited to studies of aging, since numerous single-gene mutations have been identified that affect C. elegans lifespan (AGE genes) [3,4,13,14].

C. elegans are free-living nematodes residing in the soil, where they feed on bacteria. In the laboratory, C. elegans are normally cultured on a lawn of Escherichia coli (strain OP50), on which they feed ad libitum. Although E. coli OP50 is considered non-pathogenic for the worms, as C. elegans age, the pharynx and the intestine are frequently distended and packed with bacterial cells [15]. This striking phenotype of bacterial proliferation exhibited by old animals, has been hypothesized to contribute to worm aging and demise [15,16]. C. elegans grown on bacteria that were unable to proliferate, including those killed by UV treatment or by antibiotics, had much lower rates of intestinal packing and longer lifespan [15], suggesting that bacterial proliferation within the gastrointestinal tract may contribute to the death of the animals. One implication of these findings is that as the worms age, they lose the capacity to control intestinal bacterial proliferation. However, perhaps paradoxically, C. elegans has a nutritional requirement for live, metabolically active bacteria, since worms fed on non-viable bacteria appear ill and have diminished fecundity [17].

C. elegans possesses an innate immune system with evolutionarily conserved signaling; anti-microbial innate immunity is modulated by pathways involving the DAF-2 (insulin/IGF-I like) receptor, p38 MAP kinase, and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) (Figure 1). Aging also substantially diminishes the efficiency of innate immunity [18,19]. We hypothesized that gut immunity is less efficient in older animals, leading to enhanced bacterial accumulation, reducing longevity. To address this question, we evaluated the ability of worms to control bacterial accumulation as a functional marker of intestinal immunity. We considered the effect on longevity of the bacterial species used as nutrient source, as well as host age and host genotype. We studied genes directly related to intestinal immunity and those that are not known to be related. We found a strong inverse relationship between intestinal bacterial accumulation and C. elegans longevity, operating across a range of host genotypes. These results suggest that intestinal (commensal) bacterial load is an age and host genotype-related phenotype that can be used to predict C. elegans lifespan. By analysis of mutants, we begin to establish a hierarchy of the host immune genes that have greatest effect on the intestinal milieu, and thus on longevity.

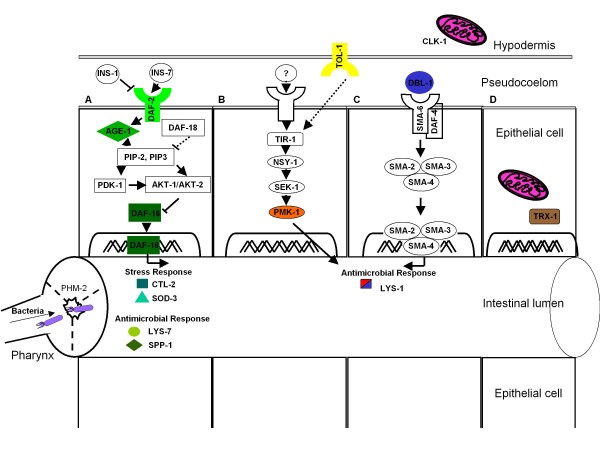

Figure 1.

Signaling pathways important for C. elegans intestinal defenses against bacterial proliferation. A. DAF-2 insulin/IGF-I like signaling pathway. Activation of the DAF-2 receptor results in the phosphorylation of the phosphatidyl inositol 3 kinase (AGE-1) which catalyses the conversion of phosphatidylinositol biphosphate (PiP2) into phosphatidylinositol triphosphate (PiP3). The kinases PDK-1 and AKT-1/AKT-2 are activated by PiP3, which inhibits the transcription factor DAF-16. Relief of this inhibition leads to the expression of a set of stress response and antimicrobial genes. B. p38 MAPK pathway. PMK-1 is homologous to the mammalian p38 MAPK and acts downstream of NSY-1/MAKK kinase kinase and SEK-1/MAPK kinase. No interaction between TOL-1 and TIR-1 has been demonstrated. C. TGF-β pathway. The TGF-β homologue DBL-1 binds to the heterodimeric receptor SMA-6/DAF-4 and signals through the Smad proteins SMA-2, SMA-3 and SMA-4, which activate the transcription of genes involved in regulation of body size and innate immunity. The expression of lysozyme gene lys-1 is under the control of the p38 MAPK pathway and the DBL-1/TGF-β pathway. D. Mitochondrial enzymes. CLK-1 is an enzyme required for the biosynthesis of ubiquinoe CoQ9, an acceptor of electrons from both complexes I and II in C. elegans cells. Decreased complex I-dependent respiration of clk-1 mutants leads to decreased ROS production with lengthening lifespan and slowing development. TRX-1 is a mitochondrial oxidoreductase with important roles in lifespan regulation and oxidative stress response.

Results

Role of DAF-2 insulin-signaling pathway on C. elegans lifespan

Under typical laboratory conditions at 25°C on NGM agar plates with a lawn of E. coli strain OP50, a culture of wild type (N2) C. elegans has a lifespan of ~ 2 weeks [20]. Lifespans are shorter when lawns are composed of bacteria that are more pathogenic for humans [21]; conversely, host mutations that increase resistance to bacterial infection prolong C. elegans lifespan [22]. First, we confirmed [23,24] and extended these observations by analyzing the effect on lifespan of the DAF-2 signaling pathway in C. elegans exposed to E. coli OP50 or the more pathogenic S. typhimurium strain SL1344. We sought to confirm whether under the experimental conditions we used, there is a survival difference for worms grown on lawns of E. coli OP50 or S. typhimurium SL1344. As expected, the average survival in days (TD50) for N2 worms exposed to S. typhimurium SL1344 was 10.8 ± 1.37 days, significantly (p = 0.02) shorter than when exposed to E. coli OP50 (12.9 ± 0.51) [23,24] (Table 1). Next, we examined whether we also could find the expected differences in lifespan according to worm genotype. As expected, for both the E. coli and S. typhimurium strains, lifespan was significantly reduced for the daf-16 mutants, but significantly increased for the daf-2 and age-1 mutants, compared to wild type (Figure 2A and 2B; Table 1). These findings, confirming prior observations [22], indicate the importance to lifespan of both bacterial strain and worm genotype related to intestinal immunity.

Table 1.

Lifespan and intestinal colonization of C.elegans N2 and mutants with growth on E. colior Salmonellalawnsa

| E. coli OP50 | S. typhimuriumSL1344 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Symbol |

TD50 (Mean ± SD) |

Day 2 log10 intestinal cfu (Mean ± SD) |

TD50 (Mean ± SD) |

Day 2 log10 intestinal cfu (Mean ± SD) |

| N2 |  |

12.93 ± 0.50 | 2.76 ± 0.22 | 10.87 ± 1.37 | 3.22 ± 0.07 |

| daf-2 |  |

26.45 ± 1.34^^ | 1.70 ± 0.12^^ | 20.17 ± 0.29^^ | 1.87 ± 0.15^^ |

| age-1 |  |

18.75 ± 0.35^^ | 2.48 ± 0.32 | 13.70 ± 0.14^ | 2.36 ± 0.48^ |

| daf-16 |  |

8.05 ± 0.38^^ | 3.30 ± 0.19 | 5.53 ± 0.23^^ | 3.55 ± 0.15^ |

| lys-7 |  |

9.30 ± 0.74^ | 2.93 ± 0.39 | 8.83 ± 0.25^ | 3.31 ± 0.28 |

| spp-1 |  |

9.80 ± 0.59^ | 2.67 ± 0.27 | 8.70 ± 0.14^ | 3.41 ± 0.23 |

| sod-3 |  |

11.90 ± 1.01 | 2.87 ± 0.24 | 10.93 ± 1.23 | 3.45 ± 0.25 |

| ctl-2 |  |

9.48 ± 0.29^ | 2.69 ± 0.18 | 8.98 ± 0.67^ | 3.88 ± 0.14^ |

| dbl-1 |  |

5.80 ± 0.57^^ | 3.35 ± 0.06 | 4.75 ± 0.79^^ | 3.86 ± 0.19^ |

| lys-1 |  |

10.00 ± 0.40^ | 2.60 ± 0.22 | 8.95 ± 0.44^ | 3.12 ± 0.24 |

| pmk-1 |  |

7.40 ± 0.16^^ | 2.58 ± 0.34 | 6.10 ± 0.99^^ | 3.71 ± 0.78^ |

| tol-1 |  |

10.53 ± 0.31^^ | 2.81 ± 0.15 | 8.98 ± 0.79^ | 3.53 ± 0.18^ |

| trx-1 |  |

7.70 ± 0.14^^ | 2.95 ± 0.17 | 6.83 ± 0.38^^ | 3.30 ± 0.38 |

a Worms were age-synchronized by a bleaching procedure. Embryos were placed on mNGM agar plates containing E. coli OP50 or S. typhimurium SL1344 and incubated at 25°C. The L4 stage was designated as day 0. A total of 100 worms were used per lifespan assay. Bacterial colonization of the intestinal tract was determined at day 2 by washing and grinding 10 worms, and plating worm lysates on MacConkey agar. All assays were performed at least three times

^p< 0.05, compared to N2

^^p< 0.001, compared to N2

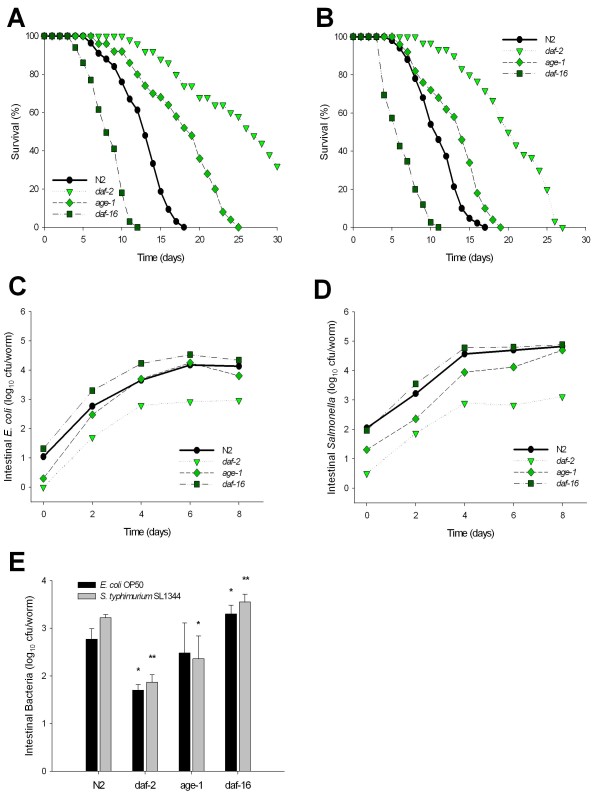

Figure 2.

Density of bacterial accumulation in the C. elegans intestine by worm age and genotype, and bacterial strain. Survival of N2 C. elegans and DAF-2 pathway mutants when grown on lawns of E. coli OP50 (Panel A) or S. typhimurium SL1344 (Panel B). Intestinal density of viable E. coli OP50 (Panel C) or S. typhimurium SL1344 (Panel D) in N2 C. elegans and DAF-2 pathway mutants. Panel E: Intestinal load of E. coli OP50 (dark bars) or S. typhimurium SL1344 (grey bars) within N2 C. elegans and DAF-2 pathway mutants on day 2 (L4 stage + 2 days) of their lifespan. Data represent Mean ± SD from experiments involving 30 worms/group. Significant difference (p < 0.05) compared to N2 worms exposed to E. coli OP50 or S. typhimurium SL1344, indicated by * or **, respectively.

Bacteria accumulate in the C. elegans intestine with aging

As worms age, bacteria accumulate in the intestinal tract [15]. However, quantitative relationships between worm genotype, lifespan, and intestinal lumen bacterial proliferation have not been examined. We hypothesized that intestinal environments that are less favorable for bacterial colonization and accumulation predict longer worm lifespan.

To investigate the relationship of bacterial load to C. elegans mortality, we measured the numbers of viable bacteria [colony forming units (cfu)] recovered across the lifespan from the C. elegans intestine. As N2 worms grown on an E. coli OP50 lawn age, the intestinal load increases from < 102 E. coli cfu/worm on day 0 (L4 stage) to 104 cfu/worm by day 4 and remains at that level through day 8 (Figure 2C), and at least as far as day 14 when > 50% of worms have died (data not shown). Similar trends were observed when N2 worms were grown on Salmonella SL1344 lawns, but colonization reached higher (~105 cfu/worm) bacterial densities (Figure 2D). Thus, as worms age, bacterial loads rise but reach bacterial strain-specific plateaus, extending until their demise.

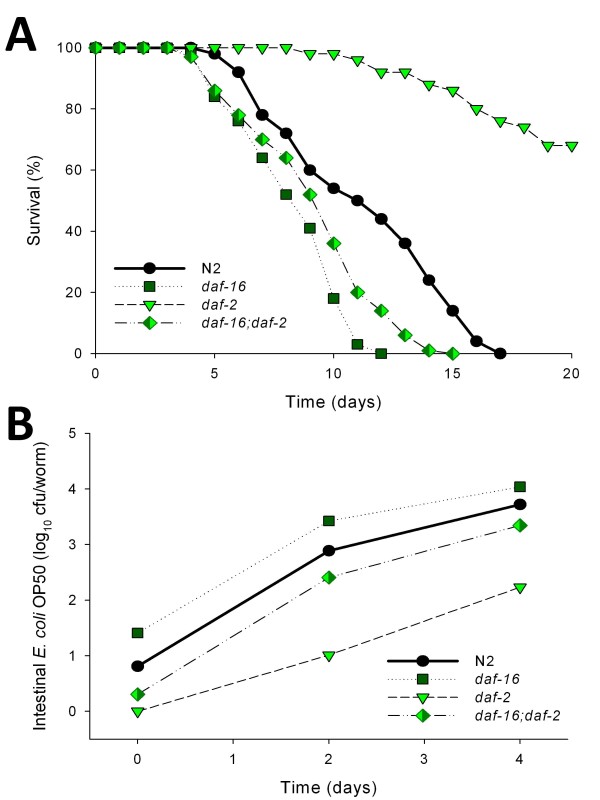

We next asked whether bacterial loads are affected by the DAF-2 pathway. The DAF-2 pathway mutants had colonization kinetics paralleling those for N2, but the bacterial loads were often significantly different (Table 1). The long-lived daf-2 mutants had about 10-fold lower colonization by both E. coli OP50 and S. typhimurium SL1344 than did N2 worms (Figure 2E). In contrast, the daf-16 mutants had significantly higher densities, consistent with their decreased lifespans. These results suggest a relationship between day 2 colonization levels and ultimate mortality 6-24 days later. Since lifespan extension of daf-2 mutants requires the daf-16 gene product [14], using the daf-16(mu86);daf-2(e1370) double mutant, we asked whether daf-16 mutations also would affect the low bacterial loads of daf-2 mutants. We confirmed that the daf-16 mutation suppresses the lifespan extension of daf-2 mutant (Figure 3A), and we now show that it suppresses the low daf-2 levels of bacterial colonization as well (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

daf-16 mutation partially suppresses the daf-2 bacterial proliferation phenotypes in C. elegans. Panel A: Survival of daf-2, daf-16 single mutants, and daf-16;daf-2 double mutant when grown on lawns of E. coli OP50. Panel B: Intestinal density of viable E. coli OP50 in the intestine of the single and daf-16;daf-2 double mutants.

Effects of host immunocompromise on bacterial proliferation and lifespan

Next, we asked whether the role of the DAF-2 pathway is unique, or whether other effectors of gut immunity also might play a role in bacterial accumulation. To approach this question, we examined worms with mutations in each of several important pathways in presumed C. elegans defenses against intestinal bacteria (see Figure 1). We first studied the p38 MAP kinase pathway by analyzing pmk-1 mutants. PMK-1 is the C. elegans p38 homologue [25-27], and the p38 MAP kinase cascade is involved in immune defenses to Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, as well as pathogenic fungi [28-30]. Similarly, we studied the DBL-1 pathway using the dbl-1 mutant, whose product is homologous to mammalian transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and is implicated in pathogen resistance [31,32]. All receptors and Smads from the DBL-1 pathway are strongly expressed in the intestine and/or pharynx of C. elegans [33,34]. We also examined mutants in tol-1, the only Toll-like receptor (TLR) in C. elegans, which is required for the full innate immune phenotype to certain Gram-negative bacteria, for the full expression of ABF-2, a defensin-like molecule expressed in the pharynx [35], and for avoiding pathogenic bacteria [36].

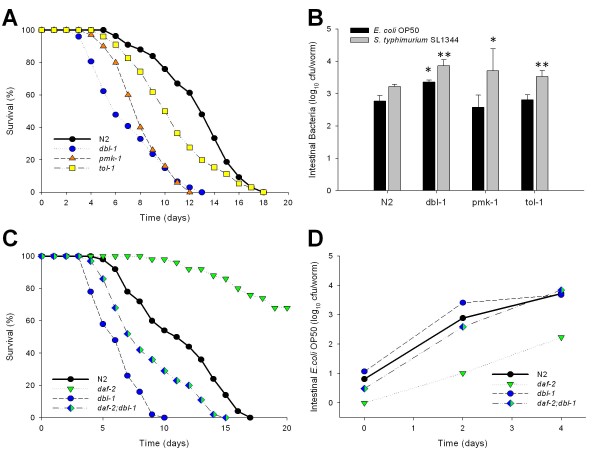

The dbl-1 mutants showed both markedly reduced lifespan and elevated intestinal bacterial loads (Figure 4A and 4B, and Table 1). In contrast, the pmk-1 and tol-1 mutants had significantly reduced lifespans, correlating with significantly elevated concentrations of S. typhimurium SL1344, although not with intestinal E. coli concentrations. These results indicate that across C. elegans genotypes, immunocompromise enhances bacterial loads, but is not sufficient to explain lifespan.

Figure 4.

Survival and density of colonizing bacteria in the intestine of C. elegans mutants with altered immune function. Panel A: Survival of N2 C. elegans and four mutants with altered intestinal immune function when grown on lawns of E. coli OP50. Panel B: Intestinal load of E. coli OP50 (dark bars) or S. typhimurium SL1344 (grey bars) within N2 C. elegans and the four mutants with altered intestinal immune function on day 2 (L4 stage + 2 days) of their lifespan. Data represent Mean ± SD from experiments involving 30 worms/group. Significant differences (p < 0.05) compared to N2 worms exposed to E. coli OP50 or S. typhimurium SL1344, indicated by * or **, respectively. Panel C: Survival of daf-2 and dbl-1 single mutants, and the daf-2;dbl-1 double mutant when grown on lawns of E. coli OP50. Panel D: Intestinal density of viable E. coli OP50 in the intestine of the single and daf-2;dbl-1 double mutants. The dbl-1 mutation suppresses both the daf-2 intestinal bacterial proliferation and lifespan phenotypes.

Therefore, to examine the interactions between the DBL-1 (TGF-B) and the DAF-2 insulin-signaling pathways, we constructed double mutant worms and analyzed both their longevity and bacterial load. Compared with wild-type N2 strain, daf-2 mutants have increased lifespan and lower bacterial load, whereas the opposite was observed for the dbl-1 mutants (Figure 4C and 4D). In the daf-2;dbl-1 double mutants, there is prolongation of longevity compared with dbl-1, with reduction in bacterial load. The phenotypic interaction between the DAF-2 and DBL-1 pathways indicates both playing roles in controlling bacterial load, with consequent effects on longevity.

Role of downstream immune effector molecules on C. elegans longevity and intestinal bacterial load

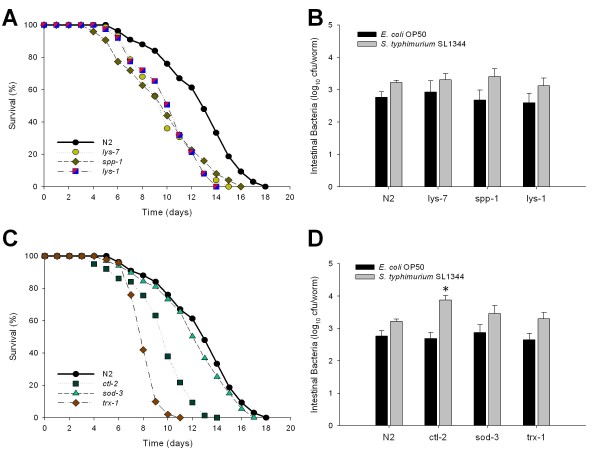

Since DAF-16 is involved in regulating several antimicrobial proteins and antioxidant enzymes expressed in the intestinal tract [37,38], we next addressed the role of the downstream effector molecules. C. elegans has 15 genes that encode lysozymes and 23 genes encoding saposin-like domains, of which lys-7, lys-8 and spp-1 are regulated by the DAF-2 pathway [31,39-41]. Intestinal bacterial loads in lys-7 and spp-1 mutants were not significantly different from those in N2, but both mutants had significantly decreased lifespan when grown on both the E. coli and Salmonella lawns (Table 1). For lys-1, regulated by both the p38 MAP kinase and TGF-β pathways, mutants have significantly shortened lifespans (Table 1). These results (Figure 5A and 5B; Table 1) indicate the importance of the encoded antimicrobial proteins in regulating lifespan, however, reduction in numbers of colonizing bacteria does not appear to be the sole mechanism for lifespan variation.

Figure 5.

Role of downstream components of the innate immunity pathways on intestinal bacterial proliferation and C. elegans lifespan. Survival of C. elegans mutants with defective expression of antimicrobial peptides (Panel A) or oxidative stress enzymes (Panel C) when grown on lawns of E. coli OP50. Panel B: Intestinal load of E. coli OP50 (dark bars) or S. typhimurium SL1344 (grey bars) with altered intestinal expression of antimicrobial peptides or oxidative stress enzymes (Panel D) on day 2 (L4 stage + 2 days) of their lifespan. Data represent Mean ± SD from experiments involving 30 worms/group. Significant (p < 0.05) differences in proliferation either E. coli or Salmonella compared to N2 worms indicated by *.

When ingesting bacterial cells, C. elegans also produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) [42]. The extreme resistance of daf-2 mutants to bacterial accumulation may depend on oxidative stress response proteins [42]. To explore this relationship, we studied worms with mutations of sod-3, encoding the anti-oxidant superoxide dismutase [43], or of ctl-2, a peroxisomal catalase [44]. The ctl-2 mutants had significantly decreased lifespan after exposure to either E. coli or Salmonella, and had significantly higher Salmonella density. In contrast, mutations in sod-3 had no effect on either lifespan or bacterial load (Figure 5C and 5D; Table 1).

Thioredoxin is involved in maintaining reduced states inside cells [45], and is involved in immune response regulation as well, by controlling NFκB and AP-1 binding [46]. The C. elegans thioredoxin (TRX-1) is expressed in neurons and in the intestine [47,48]; recent studies suggest that TRX-1 acts as a fluctuating neuronal signaling modulator within ASJ neurons to monitor the adjustment of neuropeptide expression, including insulin-like proteins, during dauer formation in response to adverse environmental conditions [49]. We found that worms with trx-1 mutations have significantly decreased lifespan when grown on E. coli or Salmonella lawns (Figure 5C; Table 1), and significantly higher bacterial load in late adulthood (see Additional file 1). These studies indicate that control of intestinal bacterial load provides a mechanism to help understand how host tissue oxidative stress responses affect longevity and supports previous observations that neuronal communication mediates longevity control and innate immunity [50-53].

Distinct colonization patterns according to worm and bacterial genotype are observed in young C. elegans

We also considered whether the spatial pattern of intestinal colonization also might affect genotype-specific survival. To address this question, the profile of bacterial accumulation in the gut was examined by considering progressively distal regions of the nematode digestive tract (see Additional file 2A). We found distinct patterns of colonization according to worm and bacterial genotype; for example, colonization of the posterior segments by the daf-2 and ctl-2 mutant worms was reduced compared with the more anterior segments. However, with worm aging, colonization levels generally equalized and became more homogeneous (see Additional file 2B and 2C). The fluorescence and cfu determinations for day 2 intestinal E. coli OP50 and S. typhimurium SL1344 concentrations were strongly correlated (see Additional file 2D and 2E). These results indicate that the localization of the large concentrations of cells observed in the intestines may correspond to the large numbers of viable bacteria.

Relationship between C. elegans genotype, colonizing strain, and lifespan

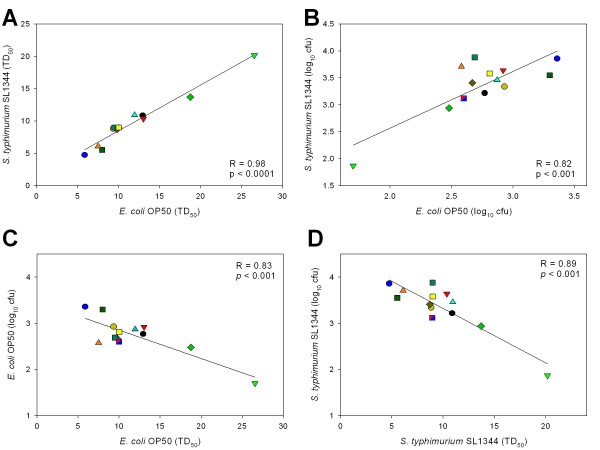

To assess the biological significance of our observations, we sought to measure how consistent is the pathogenicity of bacterial strains in the lifespan and colonization relationships. The differences in virulence of Salmonella and E. coli OP50 for C. elegans, as reflected in lifespan measurements (Table 1), permitted addressing these questions. Across 12 genotypes related to worm intestinal immunity, lifespan was strongly correlated for the two bacterial strains (R = 0.98; p < 0.0001) (Figure 6A). The consistency of these results indicates the importance of host intestinal immunity genotypes in the consequences of the interactions with colonizing bacteria. To address whether intestinal bacterial load was a consistent predictor of lifespan, we assessed survival across worm genotypes, for the two bacterial species examined. First, we found that E. coli and Salmonella densities were strongly correlated with one another across the studied genotypes related to intestinal immunity (R = 0.82; Figure 6B). For both organisms, there was an inverse correlation between day 2 bacterial density and survival [for E. coli OP50 (R = 0.83; Figure 6C), and S. typhimurium SL1344 (R = 0.89; Figure 6D)]. These strong relationships suggest that immune handling of bacterial load in the intestine of early adults is an important causative factor in determining lifespan. We chose day 2 to study, because colonization levels were significantly differed amongst the C. elegans mutants at that time point (Figure 2E). However we also performed correlations between longevity and bacterial counts for other time points (see Additional file 3), as well as calculations based on a Cox Model, which takes into account bacterial accumulation over time (see Additional file 4). Both results suggest that there exists a significant relationship between longevity and bacterial load throughout early adulthood.

Figure 6.

Relationship between C. elegans genotype, colonizing bacterial species, and lifespan. Symbols for the 14 worm genotypes are as indicated in Table 1. Panel A: Relationship of lifespans for worms grown on E. coli OP50 and S. typhimurium SL1344, measured as TD50. Worm survival is strongly correlated with growth on the two organisms (R = 0.98; p < 0.0001). Panel B: Relationship of intestinal bacterial density for worms grown on E. coli OP50 or S. typhimurium, measured as day 2 log10 cfu. Results show a strong direct correlation for the two bacterial species (R = 0.82; p < 0.001). Panel C: Relationship between lifespan and intestinal bacterial density for C. elegans grown on E. coli OP50 lawns. There is an inverse correlation between intestinal bacterial density and survival (R = 0.83; p < 0.001). Panel D: Relationship between lifespan and intestinal bacterial density for C. elegans grown on S. typhimurium SL1344 lawns. There is an inverse correlation between intestinal bacterial density and survival (R = 0.89; p < 0.001).

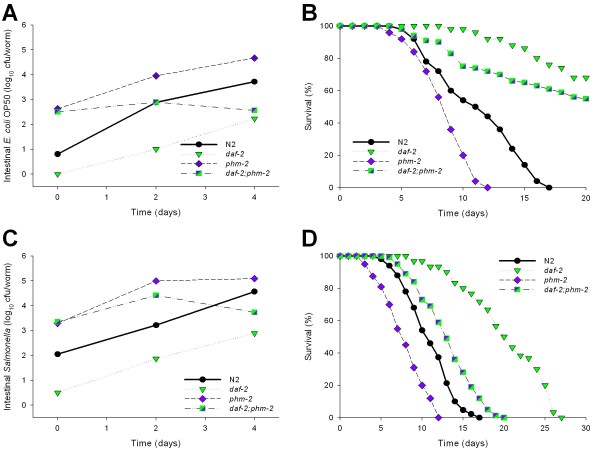

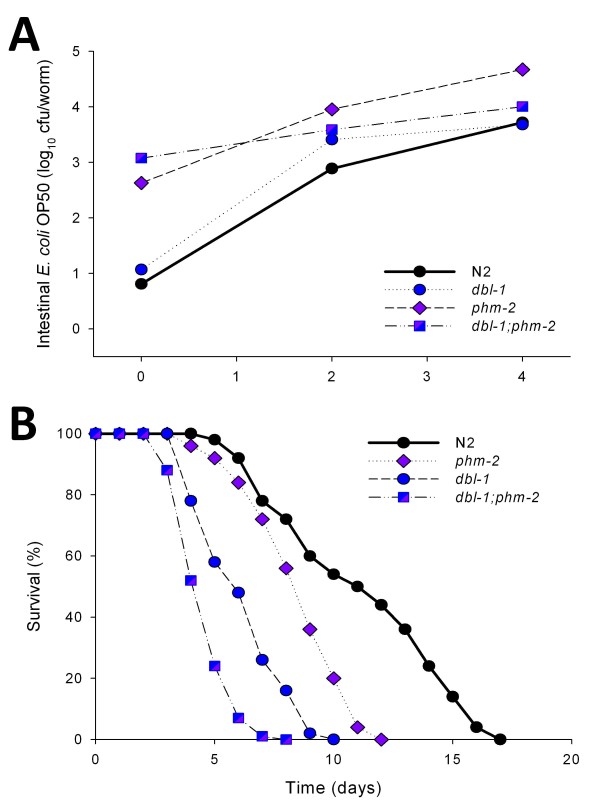

Relationships between introduced and surviving bacteria in worms with enhanced intestinal immunity

The C. elegans pharynx contains a grinder that breaks up bacterial cells to provide nutrients for the worm [54]. Grinder-defective worms (e.g. due to phm-2 mutation) have shortened lifespan [24]. We hypothesized that the reduced lifespan was related to increased accumulation of viable bacteria in the worm intestine. When grown on an E. coli OP50 lawn, the number of viable bacterial cells recovered from the intestine of phm-2 mutants was about 102 E. coli cfu/worm at L4 stage (day 0), and increased to 104 cfu/worm by day 4 (L4 + 4), ~10-fold higher than levels observed in N2 worms (Figure 7A). A similar trend was observed when phm-2 mutants were grown on S. typhimurium SL1344 lawns, but colonization reached higher bacterial densities, a difference paralleling the other worm genotypes (Figure 7C). After day 4, bacterial concentrations remain on a plateau (data not shown), similar to the observations for the other genotypes.

Figure 7.

Density of colonizing bacteria in the intestine of C. elegans strains and their survival. Number (cfu) of E. coli OP50 (Panel A) or S. typhimurium SL1344 (Panel C) within the intestine of N2 (wild type), daf-2 and phm-2 single mutant, and daf-2;phm-2 double mutant C. elegans strains. Panel B) Survival of same strains when grown on lawns of E. coli OP50 or S. typhimurium SL1344 (Panel D).

In lifespan analysis, the TD50 for phm-2 worms exposed to E. coli OP50 (8.7 ± 0.70 days) (Figure 7B), was significantly (p <0.001) shorter than for N2 worms (12.9 ± 0.51), and findings were parallel for Salmonella (Figure 7D), consistent with prior studies [24]. Thus, the grinder-deficient worms delivered more viable bacteria to the C. elegans intestine, and lifespan was reduced compared to N2 for worms grown on either E. coli or Salmonella lawns.

The long-lived C. elegans daf-2 mutants are resistant to bacterial pathogens [22] and as shown above, have significantly lower levels of bacterial colonization (Figure 2, Table 1); these worms have a significantly delayed decline in pharyngeal pumping [2]. Thus, daf-2 mutants could be more resistant to bacterial colonization simply because their pharynx remains functional for an extended period of time, or alternatively, because their intestinal milieu is more antimicrobial. To address this question, we constructed daf-2;phm-2 double mutants. We found that young daf-2;phm-2 double mutants have significantly higher bacterial loads than the wild type and daf-2 single mutants, resembling the phm-2 single mutants (Figure 7A); thus, early on, the phm-2 phenotype dominates. However, as the daf-2;phm-2 mutants age, they become increasingly capable of controlling bacterial colonization, with accumulation levels diminishing to the daf-2 level. Furthermore, their overall lifespan is very similar to the lifespan of daf-2 single mutants when exposed to E. coli (Figure 7B). Similar trends, although with a more intermediate phenotype, were observed when the worms were exposed to Salmonella lawns (Figures 7C and 7D), indicating that the daf-2 phenotypes ultimately become dominant. Thus, in the presence of enhanced intestinal immunity, the number of delivered bacterial cells has no long-term effect on bacterial load or on longevity.

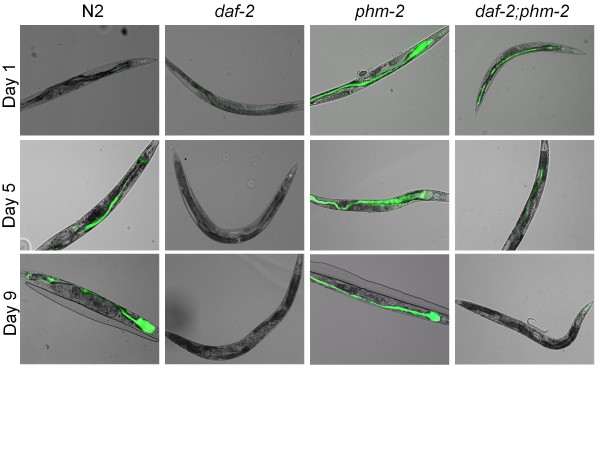

To extend these observations, the profile of bacterial accumulation in the intestinal lumen after feeding E. coli OP50 expressing GFP was studied. As before, E. coli accumulated in the intestine of N2 worms as they aged, leading to a marked distension of the intestinal lumen by day 9 (Figure 8). The daf-2 and phm-2 single mutants showed contrasting phenotypes, with no bacterial accumulation detected by day 9 and noticeable bacterial packing from day 1, respectively. The kinetics of bacterial accumulation observed in the daf-2;phm-2 double mutants correlated with the cfu quantitation (Figure 7C), indicating increasing control of bacterial load over time.

Figure 8.

C. elegans daf-2 mutants do not require a functional grinder to control intestinal bacterial proliferation. Fluorescence microscopy of N2, daf-2 and phm-2 single mutant, and daf-2;phm-2 double mutant C. elegans strains feeding on GFP-expressing E. coli.

Relationships between introduced and surviving bacteria in worms with decreased intestinal immunity

To examine the effect of both increased bacterial delivery to the intestine and decreased immunity, we created a pharynx defective (phm-2) and immunocompromised (dbl-1) double mutant [31,55]. As before, the dbl-1 single mutant showed a difference in bacterial load compared with N2 (Figure 9A), as well as a decreased lifespan reflecting their diminished immunity (Figure 9B). Bacterial load on day 0 (L4 stage) were markedly (100 fold) higher in the dbl-1;phm-2 double mutants than in the dbl-1 single mutant and N2 wild type worms, and 10 times higher than in the phm-2 single mutant (Figure 9A). As worms grew older, they were ill-appearing; by day 3, they had decreased body movement and coordination, decreased pharyngeal pumping, and showed a dramatic reduction in survival (Figure 9B). The bacterial concentrations did not increase as much as the phm-2 single mutants, most likely because they were feeding poorly. The early life results indicate that the DBL-1 pathway and the pharynx have additive effects in control of bacterial load, with drastic effects on survival when both are interrupted.

Figure 9.

Immunocompromised C. elegans are hypersusceptible to bacterial accumulation. Panel A: Number (cfu) of E. coli OP50 within the intestine of N2, dbl-1 and phm-2 single mutant, and dbl-1;phm-2 double mutant C. elegans strains. Panel B: Survival of same strains when grown on lawns of E. coli OP50.

Effect of mitochondrial function on bacterial proliferation and lifespan

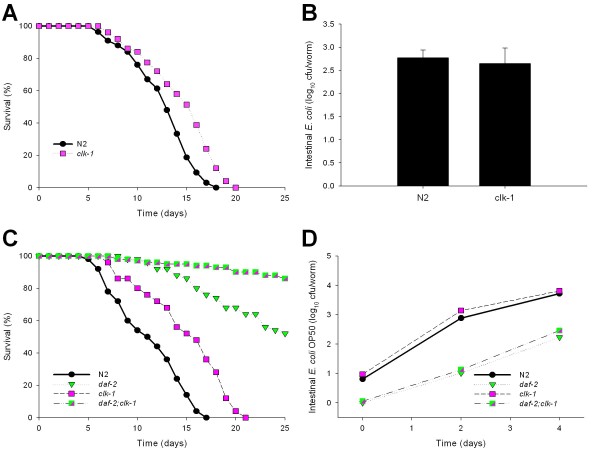

Finally, we asked whether intestinal bacterial load is affected by genes known to have effects on lifespan that are independent of gut immunity. Ubiquinone (coenzyme Q) biosynthesis, essential in mitochondrial respiration, requires demethoxyubiquinone hydroxylase, encoded by clk-1 [56]. C. elegans clk-1 mutants that generate diminished amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and subsequent reduced levels of oxidative damage [57,58], have prolonged lifespans and resistance to stress induced by UV irradiation, heat, or reactive oxygen [56,59]. Inactivation of clk-1 results in an average slowing of a number of developmental and physiological processes, including cell cycle, embryogenesis, post-embryonic growth, rhythmic behaviors, and aging [60]. No role in innate immunity has been described so far.

As predicted, the clk-1 mutants had a prolonged lifespan compared to N2, when grown on lawns of E. coli OP50 (Figure 10A).We then assessed whether clk-1 affects intestinal bacterial accumulation. We found that the clk-1 mutants had intestinal E. coli concentrations that were not significantly different from wild type worms (Figure 10B), consistent with the independence of its longevity phenotype on intestinal bacterial accumulation.

Figure 10.

Daf-2 mutation suppresses the clk-1 mitochondrion-dependent intestinal bacterial proliferation phenotype. Survival of N2 C. elegans and clk-1 mutants when grown on lawns of E. coli OP50 (Panel A). Panel B: Intestinal load of E. coli OP50 within N2 C. elegans and clk-1 mutants on day 2 (L4 stage + 2 days) of their lifespan. Data represent Mean ± SD from experiments involving 30 worms/group. Panel C: Survival of daf-2 and clk-1 single mutants and the daf-2;clk-1 double mutant when grown on lawns of E. coli OP50. Panel D: Intestinal density of viable E. coli OP50 in the intestine of the daf-2 and clk-1 single mutants and the daf-2;clk-1 double mutants.

Genetic analyses have provided evidence that lifespan extension by clk-1 is distinct from the DAF-2 signaling pathway, since daf-2;clk-1 double mutants live much longer than either single mutant, and mutations in clk-1 cannot be suppressed by daf-16 loss-of-function mutations [61]. First, we confirmed that the daf-2;clk-1 double mutant has prolonged survival compared to either single mutant (Figure 10C). We next considered the interplay of the clk-1 and the daf-2 pathways in relation to intestinal bacterial density. We found that the daf-2;clk-1 double mutant had intestinal bacterial concentrations that mirror daf-2 single mutants (Figure 10D), suggesting clk-1 plays no role on intestinal bacterial accumulation. That the double mutant has longer survival than either single mutant (Figure 10C) indicates independence of their longevity mechanisms.

Discussion

To better understand aging, we studied intestinal bacterial accumulation in C. elegans differing in the bacterial species that they ingest, as well as their genotype and maturation. Here, we provide evidence that the extent of intestinal bacterial accumulation early in adulthood, which is controlled by gut immunity that decreases with age, is strongly and inversely correlated with longevity.

Bacteria are the source of nutrition for C. elegans, but ultimately as the worms age, viable bacteria accumulate in the intestine [15]. Worms grown on the soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis have a longer lifespan compared to those grown on E. coli OP50 or many other tested bacterial species [22]. However, worms that are grown on B. subtilis spores produce fewer eggs and are smaller and thinner than those fed on vegetative cells of B. subtilis or E. coli OP50 [62]. This observation indicates that growth on spores compared to vegetative (metabolically active) bacterial cells limits nutrient availability. Thus, vegetative bacteria represent two competing elements to C. elegans: a nutrient that fosters development and fecundity, and a toxic component that may reduce lifespan [17]. Worm defenses, including the pharyngeal grinder and intestinal immunity, act to mitigate the latter phenomenon.

The nematode responds to bacteria with conserved innate immune responses, however, aging is accompanied by a decline of immune functions [18,19]. This may represent a general evolutionary process, since after reproductive age individuals compete with their own progeny for available nutrients. Although the functionality of the C. elegans immune system during aging has been extensively examined [38,63], we now have simultaneously examined longevity and control of bacterial proliferation across worm genotype, age, and bacterial strain differences. We confirm that viable bacteria accumulate in the C. elegans intestine as they age [15], and now show that both bacterial strain type and worm genotype related to gut immunity affect intestinal bacterial accumulation, which might play a significant role in lifespan determination, since we found that lifespan and bacterial load are inversely correlated. Previous studies had quantified bacterial proliferation by CFU enumeration only in N2 worms [64]. More recent studies showed substantially fewer bacteria in the gut of certain long-lived C. elegans mutants; however, these observations were by semi-quantitative microscopy only [65]. By quantitatively characterizing the kinetics of bacterial proliferation in the C. elegans intestine, in wild type and mutant worms, we establish a basis to better dissect the interplay of bacteria, host genotypes, and age.

One of the aims in this study was to characterize the kinetics of intestinal bacterial colonization. Salmonella is a pathogen of C. elegans that permits examining this question since it kills worms relatively slowly, rather than in a rapid manner. However, other than consistently higher numbers, there were few cases in which Salmonella and E. coli results differed greatly. These differ from previous data that reported significant differences in the lifespan of C. elegans when grown on Salmonella compared to E. coli [23]. The discrepancy might be explained in part by differences in methodology, since in this work we grew the worms on lawns of Salmonella rather than exposing them as L4's. However, E.coli also is pathogenic to C. elegans [15,31,64], and many C. elegans antimicrobial genes are induced, some even more strongly (lys-1 and spp-1) than in the presence of other pathogens [40]. As such, E. coli is just one other bacterial species to which C. elegans can sense and respond.

In our experimental system, we found significant differences in bacterial accumulation at day 2 of adult life, and that variation in the intestinal bacterial loads among the immunodeficient mutants correlated with lifespan differences. Why were differences in bacterial proliferation significant at day 2? One explanation is that since C. elegans produces nearly all of its progeny within the first 2 days of its adult life [66], immunity is tightly regulated during development and early adult life, but not post-reproductively. Consistent with this, a striking decrease in expression of PMK-1 regulated genes and a decline in PMK-1 levels in aging animals was recently described [67], suggesting a diminished role for PMK-1 pathway in host defense towards the end of life. Therefore, a decline in immune function in late adult life may either be non-selected, or may be selected at a population level, since as discussed above, non-reproducing worms limit population numbers and stability, since they compete with their progeny for resources [68]. The longevity of C. elegans in the wild is substantially (10-fold) shorter than under laboratory conditions [68]; it is probable that most worms die just after laying eggs, since nutrient availability usually is limiting in natural settings.

If the immune system of C. elegans experiences an age-related decline [67], which is accompanied by other age-related changes such as pharyngeal deterioration and reduced defecation [69], why does the bacterial load reach a strain-specific (and host-genome-specific) plateau that extends until their demise? One possibility is that a cohort effect exists, in which the fraction of worms examined in late worm adulthood constitutes a subpopulation that survived because they maintain the ability to control bacterial proliferation. Alternatively, late in life the bacterial populations develop specific syntrophic equilibria [70] that are resilient to changes in host milieu.

That the long-lived daf-2 mutants resist intestinal bacterial accumulation may be due to enhanced expression of luminal antimicrobial proteins and antioxidant enzymes as evidenced using DNA microarray analysis [38,71-73]. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that mutants lacking expression of the antimicrobial proteins lys-7 and spp-1, and the oxidative stress response enzyme ctl-2 had diminished lifespan. Since C. elegans immune responses generate ROS when bacterial pathogens are ingested [42], oxidative stress responses may aid in resistance by protecting against ROS-induced tissue damage. Thus, antioxidants in the gut protect from oxidative stress, preserving adequate intestinal cell function. The ctl-2 mutants also had significantly higher S. typhimurium density, consistent with an ROS resistance model. However, the intestinal bacterial densities of lys-7, lys-1, and spp-1 worms were not significantly different from N2. One explanation might be redundancy of the antimicrobial protein genes (15 encoding lysozymes and 23 encoding saposin-like domains) in C. elegans. If the numerous genes act in concert, the increased longevity of the daf-2 mutants might reflect synergies of individual genes that exert relatively small effects on lifespan and on bacterial colonization. Although the daf-2 effect also could reflect reduced senescence of the pharyngeal apparatus or defective pumping, the mixed phenotype of the daf-2;phm-2 mutant provides evidence against that hypothesis, and supports the role of enhanced expression of luminal antimicrobial proteins and antioxidant enzymes in controlling bacterial accumulation and ultimately longevity. That the colonization phenotypes of the daf-2;phm-2 double mutants is virtually identical to phm-2 early in adult life, but with aging, the daf-2 effects dominate, indicate the importance of pharyngeal function early in adult life, but that intestinal immune responses dominate as worms become senescent.

Thioredoxin expression may enhance longevity, since transgenic mice expressing human TRX-1 live longer [74]. We confirm that trx-1 mutants have significantly decreased lifespan [47,48], and found that intestinal bacterial density was greater in late adulthood (Additional Figure 1) when compared to N2. TRX-1 may affect C. elegans longevity and bacterial load due to its antioxidant properties [47], or alternately by modulation of redox-sensitive transcription factors, such as AP-1, that are activated during aging. The fact that bacterial load was greater in late adulthood is consistent with significantly enhanced expression of intestinal TRX-1 expression as worms age [47].

For other effectors of gut immunity, such as those encoded by dbl-1 and pmk-1, the effects on bacterial load and longevity were strongly inverse. We found that pmk-1 mutants have a shorter lifespan than previously reported [75]. Differences in lifespan may be due to different experimental conditions. Troemel et al. added 5-fluorodeoxyuridine (FUDR) to NGM plates seeded with OP50, to prevent C. elegans progeny. However, FUDR acts to inhibit DNA synthesis, and also inhibits bacterial proliferation [76]. That abrogating two host anti-bacterial mechanisms (e.g. dbl-1 and phm-2) produces very short survival indicates synergism between anatomical and immune defenses.

We found a strong correlation between bacterial counts and lifespan. However to better understand the biology of this host-microbial relationship, it would be critical to distinguish between continuing accumulation vs. bacterial proliferation. We address this point in a second manuscript, where we created model systems to evaluate between the possibility of bacterial persistence and proliferation or new bacterial entry [77]. We found that host age as well as bacterial strain determine the nature of bacterial persistence in the C. elegans intestine. We also provide evidence for active competition in vivo for colonization sites as well as evidence for in vivo bacterial adaptation. We propose two mechanisms to explain the strong inverse correlation between bacterial load and lifespan. First, the intestinal milieu of older worms is more permissive for bacterial cells in general. Second, over time there is selection for bacteria that are better adapted to the intestinal niche. Our two studies provide support for both mechanisms.

Conclusions

We performed quantitative studies to determine intestinal bacterial load in C. elegans and found a strong correlation between bacterial counts and lifespan. We showed that as adult worms age, they lose their capacity to control bacterial accumulation, and provide evidence that intestinal bacterial load, regulated by gut immunity may play a role in lifespan determination. In total, these studies focus attention on the worm intestine as a locus that influences longevity in the presence of an accumulating bacterial population. Further studies defining the interplay between bacterial species and host immunity in C. elegans may provide insights into the general mechanisms of aging and age-related diseases.

Methods

C. elegans strains and growth conditions

All strains (Table 2) were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center and maintained on modified (0.30% peptone) nematode growth media (mNGM), using standard procedures [78]. The daf-2;dbl-1 double mutant was constructed using standard genetic methods [79]. Male stocks were established by heat shock [80] or occurring spontaneously in hermaphrodite populations maintained at 15°. We crossed daf-2 males with dbl-1 hermaphrodites and F2 animals were picked onto individual plates and grown at 20°C. Presumed double mutants were chosen from plates in which progeny exhibited a dpy (fat and short) [81] phenotype, and confirmed by changing the plates to 25°C and screening for dauer larvae [82]. To construct the daf-2;phm-2 double mutant, we crossed daf-2 males with phm-2 hermaphrodites and F2 animals were picked onto individual plates and grown at 25°C. Presumed double mutants were chosen from plates in which progeny were arrested at dauer stage. Double mutants were confirmed by direct microscopic observation of the pharynx (see Additional file 5).

Table 2.

C.elegans single gene mutants used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Function | Relevant C. elegans phenotype | Reference* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | Wild type | Reference C. elegans strain | [20] | |

| daf-2 | (e1370)III | Insulin-like receptor gene | Extended lifespan, increased resistance to heat, oxidative stress, and pathogens. | [14,22] |

| age-1 | (hx546)II | Phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase. Downstream of daf-2. | Similar to daf-2 | [22,83] |

| daf-16 | (mu86)I | Fork-head transcription factor. Negatively regulated by the daf-2 pathway. | Decreased lifespan, decreased resistance to heat, oxidative stress, and pathogens. | [22,84] |

| lys-7 | (ok1384)V | Lysozyme | Induced by S. marcescens infection | [31] |

| spp-1 | (ok2703) | Saposin-like protein | Active against E. coli and expressed in the intestine | [85] |

| sod-3 | (gk235)X | Superoxide dismutase | Increased susceptibility to E. faecalis | [42] |

| ctl-2 | (ok1137)II | Catalase | Decreased lifespan, increased susceptibility to E. faecalis | [42,44] |

| dbl-1 | (nk3)V | Homologue of mammalian TGF-β | Enhanced susceptibility to pathogens | [31,86] |

| lys-1 | (ok2445) | Lysozyme | Induced by S. marcescens infection | [31] |

| pmk-1 | (km25) | p38 MAP kinase homolog | Enhanced susceptibility to pathogens | [27] |

| tol-1 | (nr2033)I | Sole Tol-like receptor. | Unable to avoid pathogenic bacteria. Susceptible to killing by gram negative bacteria. . | [35,36] |

| trx-1 | (ok1449)II | Thioredoxin | Decreased lifespan | [47,48] |

| phm-2 | (ad597)I | Pharynx morphogenesis | Defective terminal bulb. Allows greater numbers of intact bacteria to enter the intestinal tract. | [54] |

| clk-1 | (e2519)III | Coenzyme Q Mitochondrial function | Extended lifespan | [56] |

*All strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center, University of Minnesota

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions

E. coli OP50 [20] and S. typhimurium SL1344 [87] have been described. S. typhimurium SL1344 containing plasmid pSMC21 was kindly provided by Fred Ausubel [23]. Cultures were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C supplemented or not with ampicillin (100 μg/ml). Bacterial lawns used for C. elegans lifespan assays were prepared by spreading 25 μl of an overnight culture of the bacterial strains on 3.5 cm diameter mNGM agar plates. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C and cooled to room temperature before use.

Lifespan assays

C. elegans lifespan determinations essentially followed established methods [15,23]. However, to avoid competition between introduced bacterial strains, nematodes were age-synchronized by a bleaching procedure [78], then embryos were incubated at 25°C on mNGM agar plates containing E. coli OP50 or S. typhimurium SL1344. The fourth larval stage (L4) was designated as day 0 for our studies, and worms were transferred daily to fresh plates to eliminate overcrowding by progeny and until they laid no further eggs. Worm mortality was scored over time, with death defined when a worm no longer responded to touch [14]. Worms that died of protruding/bursting vulva, bagging, or crawling off the agar were excluded from the analysis [88]. Kaplan-Meir survival analysis was performed using GraphPadPrism5. For each bacterial lawn, the time required for 50% of the worms to die (TD50) for each mutant population was compared to that for the wild type population, using a paired t test. A P-value < 0.05 was considered significantly different from control. A total of 100 worms were used in each lifespan experiment, and all were performed at least in duplicate.

Bacterial colonization assay

Nematodes were age-synchronized by bleaching [78], and embryos were incubated at 25°C on mNGM agar plates containing E. coli OP50 or S. typhimurium SL1344, as above, to prepare for the bacterial colonization assays. Bacterial colonization of C. elegans was determined using a method adapted from Garsin et al. [64] and RA Alegado (personal communication and [89]). At each time point tested, 10 worms were picked and placed on an agar plate containing 100 μg/ml gentamicin to remove surface bacteria. They then were washed in 5 μl drops of 25 mM levamisole in M9 buffer (LM buffer) for paralysis and inhibition of pharyngeal pumping and expulsion, then were washed twice more with LM buffer containing 100 μg/ml gentamicin, and twice more with M9 buffer alone. The washed nematodes then were placed in a 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube containing 50 μl of PBS buffer with 1% Triton X-100 and mechanically disrupted using a motor pestle. Worm lysates were diluted in PBS buffer and incubated overnight at 37°C on MacConkey agar. Lactose-fermenting (E. coli) and non-fermenting (Salmonella) colonies were quantified, and used to calculate the number of bacteria per nematode.

Fluorescence microscopy

Worms were washed and placed on a pad of 2% agarose in a 5 μl drop of M9 buffer with 30 mM sodium azide as an anesthetic. When the worms stopped moving, a coverslip was placed over the pad and worms were examined by fluorescence microscopy using a Leica DMI 6000B inverted microscope. For comparisons, the nematode digestive tract was divided in three regions of approximately equal length (anterior, middle, posterior) for quantitative studies; bacterial load and location were analyzed using Image-Pro Plus (version 6.0) software.

Statistical analysis

All assays were performed at least in duplicate. Linear regression analysis was performed using Sigma Plot V.10. Data were analyzed using two-sample T-tests assuming equal variances; p < 0.05 was considered significantly different from control.

Authors' contributions

CPC conducted experiments, data/statistical analysis, and manuscript preparation. ERB conducted experiments. MJB provided the conceptual framework, experimental design, and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Cynthia Portal-Celhay, Email: portac01@med.nyu.edu.

Ellen R Bradley, Email: ellen.bradley@gmail.com.

Martin J Blaser, Email: Martin.Blaser@nyumc.org.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center at the University of Minnesota, the C. elegans Knockout Project at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, and the C. elegans Reverse Genetics Core Facility at the University of British Columbia, which are part of the International C. elegans Gene Knockout Consortium, for the strains used in this study. Supported in part by NIH RO1 GM63270, the Michael Saperstein Medical Scholars Program, the Ellison Medical Foundation, and the Diane Belfer Program for Human Microbial Ecology.

References

- Crews DE. Senescence, aging, and disease. J Physiol Anthropol. 2007;26(3):365–372. doi: 10.2114/jpa2.26.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Xiong C, Kornfeld K. Measurements of age-related changes of sphysiological processes that predict lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(21):8084–8089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400848101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarente L, Kenyon C. Genetic pathways that regulate ageing in model organisms. Nature. 2000;408(6809):255–262. doi: 10.1038/35041700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TE. Caenorhabditis elegans 2007: the premier model for the study of aging. Exp Gerontol. 2008;43(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge L. Some highlights of research on aging with invertebrates, 2008. Aging Cell. 2008;7(5):605–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattelle DB, Buckingham SD. Invertebrate studies and their ongoing contributions to neuroscience. Invert Neurosci. 2006;6(1):1–3. doi: 10.1007/s10158-005-0014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargmann CI. Neurobiology of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome. Science. 1998;282(5396):2028–2033. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinchen JM, Hengartner MO. Tales of cannibalism, suicide, and murder: Programmed cell death in C. elegans. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2005;65:1–45. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(04)65001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad BC, Reed RR. Chemosensation: molecular mechanisms in worms and mammals. Trends Genet. 1999;15(4):150–153. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(99)01695-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aballay A, Ausubel FM. Caenorhabditis elegans as a host for the study of host-pathogen interactions. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2002;5(1):97–101. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(02)00293-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sifri CD, Begun J, Ausubel FM. The worm has turned-microbial virulence modeled in Caenorhabditis elegans. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13(3):119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darby C. Interactions with microbial pathogens. WormBook, ed The C elegans Research Community. 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Anson RM, Hansford RG. Mitochondrial influence on aging rate in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2004;3(1):29–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2003.00077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C, Chang J, Gensch E, Rudner A, Tabtiang R. A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature. 1993;366(6454):461–464. doi: 10.1038/366461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garigan D, Hsu AL, Fraser AG, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, Kenyon C. Genetic analysis of tissue aging in Caenorhabditis elegans: a role for heat-shock factor and bacterial proliferation. Genetics. 2002;161(3):1101–1112. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.3.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gems D, Riddle DL. Genetic, behavioral and environmental determinants of male longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2000;154(4):1597–1610. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.4.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenaerts I, Walker GA, Van Hoorebeke L, Gems D, Vanfleteren JR. Dietary restriction of Caenorhabditis elegans by axenic culture reflects nutritional requirement for constituents provided by metabolically active microbes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(3):242–252. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.3.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVeale B, Brummel T, Seroude L. Immunity and aging: the enemy within? Aging Cell. 2004;3(4):195–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2004.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez CR, Nomellini V, Faunce DE, Kovacs EJ. Innate immunity and aging. Exp Gerontol. 2008;43(8):718–728. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77(1):71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewbank JJ. Tackling both sides of the host-pathogen equation with Caenorhabditis elegans. Microbes Infect. 2002;4(2):247–256. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01531-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garsin DA, Villanueva JM, Begun J, Kim DH, Sifri CD, Calderwood SB, Ruvkun G, Ausubel FM. Long-lived C. elegans daf-2 mutants are resistant to bacterial pathogens. Science. 2003;300(5627):1921. doi: 10.1126/science.1080147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aballay A, Yorgey P, Ausubel FM. Salmonella typhimurium proliferates and establishes a persistent infection in the intestine of Caenorhabditis elegans. Current biology: CB. 2000;10(23):1539–1542. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00830-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrousse A, Chauvet S, Couillault C, Kurz CL, Ewbank JJ. Caenorhabditis elegans is a model host for Salmonella typhimurium. Curr Biol. 2000;10(23):1543–1545. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00833-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati NT, Fitzgerald KA, Kim DH, Feinbaum R, Golenbock DT, Ausubel FM. Requirement for a conserved Toll/interleukin-1 resistance domain protein in the Caenorhabditis elegans immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(17):6593–6598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308625101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couillault C, Pujol N, Reboul J, Sabatier L, Guichou JF, Kohara Y, Ewbank JJ. TLR-independent control of innate immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans by the TIR domain adaptor protein TIR-1, an ortholog of human SARM. Nat Immunol. 2004;5(5):488–494. doi: 10.1038/ni1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Feinbaum R, Alloing G, Emerson FE, Garsin DA, Inoue H, Tanaka-Hino M, Hisamoto N, Matsumoto K, Tan MW. et al. A conserved p38 MAP kinase pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans innate immunity. Science. 2002;297(5581):623–626. doi: 10.1126/science.1073759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aballay A, Drenkard E, Hilbun LR, Ausubel FM. Caenorhabditis elegans innate immune response triggered by Salmonella enterica requires intact LPS and is mediated by a MAPK signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 2003;13(1):47–52. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01396-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sifri CD, Begun J, Ausubel FM, Calderwood SB. Caenorhabditis elegans as a model host for Staphylococcus aureus pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2003;71(4):2208–2217. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.4.2208-2217.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mylonakis E, Ausubel FM, Perfect JR, Heitman J, Calderwood SB. Killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by Cryptococcus neoformans as a model of yeast pathogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(24):15675–15680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232568599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallo GV, Kurz CL, Couillault C, Pujol N, Granjeaud S, Kohara Y, Ewbank JJ. Inducible antibacterial defense system in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2002;12(14):1209–1214. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00928-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan MW, Ausubel FM. Caenorhabditis elegans: a model genetic host to study Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenesis. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000;3(1):29–34. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)00047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AF, Gumienny TL, Gleason RJ, Wang H, Padgett RW. Regulation of genes affecting body size and innate immunity by the DBL-1/BMP-like pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC developmental biology. 2010;10:61. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-10-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Tokarz R, Savage-Dunn C. The expression of TGFbeta signal transducers in the hypodermis regulates body size in C. elegans. Development (Cambridge, England) 2002;129(21):4989–4998. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.21.4989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenor JL, Aballay A. A conserved Toll-like receptor is required for Caenorhabditis elegans innate immunity. EMBO Rep. 2008;9(1):103–109. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol N, Link EM, Liu LX, Kurz CL, Alloing G, Tan MW, Ray KP, Solari R, Johnson CD, Ewbank JJ. A reverse genetic analysis of components of the Toll signaling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2001;11(11):809–821. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00241-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libina N, Berman JR, Kenyon C. Tissue-specific activities of C. elegans DAF-16 in the regulation of lifespan. Cell. 2003;115(4):489–502. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00889-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CT, McCarroll SA, Bargmann CI, Fraser A, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, Li H, Kenyon C. Genes that act downstream of DAF-16 to influence the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2003;424(6946):277–283. doi: 10.1038/nature01789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas HR, Hodgkin J. Responses to infection and possible recognition strategies in the innate immune system of Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol Immunol. 2004;41(5):479–493. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alper S, McBride SJ, Lackford B, Freedman JH, Schwartz DA. Specificity and complexity of the Caenorhabditis elegans innate immune response. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(15):5544–5553. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02070-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenburg H, Hoeppner MP, Weiner J, Bornberg-Bauer E. Specificity of the innate immune system and diversity of C-type lectin domain (CTLD) proteins in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Immunobiology. 2008;213:(3–4):237-250. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez V, Mohri-Shiomi A, Maadani A, Vega LA, Garsin DA. Oxidative stress enzymes are required for DAF-16-mediated immunity due to generation of reactive oxygen species by Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2007;176(3):1567–1577. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.072587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giglio MP, Hunter T, Bannister JV, Bannister WH, Hunter GJ. The manganese superoxide dismutase gene of Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1994;33(1):37–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petriv OI, Rachubinski RA. Lack of peroxisomal catalase causes a progeric phenotype in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(19):19996–20001. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400207200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert HF. Molecular and cellular aspects of thiol-disulfide exchange. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1990;63:69–172. doi: 10.1002/9780470123096.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powis G, Montfort WR. Properties and biological activities of thioredoxins. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2001;30:421–455. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.30.1.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jee C, Vanoaica L, Lee J, Park BJ, Ahnn J. Thioredoxin is related to life span regulation and oxidative stress response in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Cells. 2005;10(12):1203–1210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2005.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda-Vizuete A, Gonzalez JC, Gahmon G, Burghoorn J, Navas P, Swoboda P. Lifespan decrease in a Caenorhabditis elegans mutant lacking TRX-1, a thioredoxin expressed in ASJ sensory neurons. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(2):484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix MA, Ashe A, Piffaretti J, Wu G, Nuez I, Belicard T, Jiang Y, Zhao G, Franz CJ, Goldstein LD. et al. Natural and experimental infection of Caenorhabditis nematodes by novel viruses related to nodaviruses. PLoS Biol. 2011;9(1):e1000586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahm JH, Kim S, Paik YK. GPA-9 is a novel regulator of innate immunity against Escherichia coli foods in adult Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2011;10(2):208–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawli T, He F, Tan MW. It takes nerves to fight infections: insights on neuro-immune interactions from C. elegans. Dis Model Mech. 2010;3(11-12):721–731. doi: 10.1242/dmm.003871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawli T, Tan MW. Neuroendocrine signals modulate the innate immunity of Caenorhabditis elegans through insulin signaling. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(12):1415–1424. doi: 10.1038/ni.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawli T, Wu C, Tan MW. Systemic and cell intrinsic roles of Gqalpha signaling in the regulation of innate immunity, oxidative stress, and longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(31):13788–13793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914715107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery L. The genetics of feeding in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1993;133(4):897–917. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.4.897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millet AC, Ewbank JJ. Immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16(1):4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewbank JJ, Barnes TM, Lakowski B, Lussier M, Bussey H, Hekimi S. Structural and functional conservation of the Caenorhabditis elegans timing gene clk-1. Science. 1997;275(5302):980–983. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayser EB, Sedensky MM, Morgan PG. The effects of complex I function and oxidative damage on lifespan and anesthetic sensitivity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2004;125(6):455–464. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata Y, Branicky R, Landaverde IO, Hekimi S. Redox regulation of germline and vulval development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2003;302(5651):1779–1782. doi: 10.1126/science.1087167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami S, Johnson TE. A genetic pathway conferring life extension and resistance to UV stress in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1996;143(3):1207–1218. doi: 10.1093/genetics/143.3.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felkai S, Ewbank JJ, Lemieux J, Labbe JC, Brown GG, Hekimi S. CLK-1 controls respiration, behavior and aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. The EMBO journal. 1999;18(7):1783–1792. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakowski B, Hekimi S. Determination of life-span in Caenorhabditis elegans by four clock genes. Science. 1996;272(5264):1010–1013. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laaberki MH, Dworkin J. Role of spore coat proteins in the resistance of Bacillus subtilis spores to Caenorhabditis elegans predation. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(18):6197–6203. doi: 10.1128/JB.00623-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElwee J, Bubb K, Thomas JH. Transcriptional outputs of the Caenorhabditis elegans forkhead protein DAF-16. Aging Cell. 2003;2(2):111–121. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garsin DA, Sifri CD, Mylonakis E, Qin X, Singh KV, Murray BE, Calderwood SB, Ausubel FM. A simple model host for identifying Gram-positive virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(19):10892–10897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191378698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans EA, Kawli T, Tan MW. Pseudomonas aeruginosa suppresses host immunity by activating the DAF-2 insulin-like signaling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(10):e1000175. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byerly L, Cassada RC, Russell RL. The life cycle of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. I. Wild-type growth and reproduction. Dev Biol. 1976;51(1):23–33. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(76)90119-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youngman MJ, Rogers ZN, Kim DH. A decline in p38 MAPK signaling underlies immunosenescence in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS genetics. 2011;7(5):e1002082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhies WA, Fuchs J, Thomas S. The longevity of Caenorhabditis elegans in soil. Biol Lett. 2005;1(2):247–249. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2004.0278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins JJ, Huang C, Hughes S, Kornfeld K. The measurement and analysis of age-related changes in Caenorhabditis elegans (January 24, 2008) http://www.wormbook.org Worm Book, ed. The C. elegans Research Community, WormBook, doi/10.1895/wormbook.1.137.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Backhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, Peterson DA, Gordon JI. Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine. Science. 2005;307(5717):1915–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1104816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gems D, McElwee JJ. Ageing: Microarraying mortality. Nature. 2003;424(6946):259–261. doi: 10.1038/424259a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen VL, Gallo M, Riddle DL. Targets of DAF-16 involved in Caenorhabditis elegans adult longevity and dauer formation. Experimental gerontology. 2006;41(10):922–927. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CT. The search for DAF-16/FOXO transcriptional targets: approaches and discoveries. Experimental gerontology. 2006;41(10):910–921. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsui A, Hamuro J, Nakamura H, Kondo N, Hirabayashi Y, Ishizaki-Koizumi S, Hirakawa T, Inoue T, Yodoi J. Overexpression of human thioredoxin in transgenic mice controls oxidative stress and life span. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2002;4(4):693–696. doi: 10.1089/15230860260220201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troemel ER, Chu SW, Reinke V, Lee SS, Ausubel FM, Kim DH. p38 MAPK regulates expression of immune response genes and contributes to longevity in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 2006;2(11):183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehelie R, Eriksson S, Wang L. Effect of fluoropyrimidines on the growth of Ureaplasma urealyticum. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2004;23(8-9):1499–1502. doi: 10.1081/NCN-200027714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portal-Celhay C, Blaser MJ. Competition and resilience between founder and introduced bacteria in the Caenorhabditis elegans gut. Infection and Immunity. 2012;80(3):1288–1299. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05522-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiernagle T. Maintenance of C. elegans. Wormbook, ed The C elegans Research Community, Wormbook. 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hope IA. C. elegans: A Practical Approach. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sulston J, Hodgkin J. Methods in The Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Savage-Dunn C, Maduzia LL, Zimmerman CM, Roberts AF, Cohen S, Tokarz R, Padgett RW. Genetic screen for small body size mutants in C. elegans reveals many TGFbeta pathway components. Genesis. 2003;35(4):239–247. doi: 10.1002/gene.10184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert PS, Riddle DL. Mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans that form dauer-like larvae. Dev Biol. 1988;126(2):270–293. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TE, Tedesco PM, Lithgow GJ. Comparing mutants, selective breeding, and transgenics in the dissection of aging processes of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetica. 1993;91(1-3):65–77. doi: 10.1007/BF01435988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K, Dorman JB, Rodan A, Kenyon C. daf-16: An HNF-3/forkhead family member that can function to double the life-span of Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1997;278(5341):1319–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5341.1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banyai L, Patthy L. Amoebapore homologs of Caenorhabditis elegans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1429(1):259–264. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4838(98)00237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita K, Chow KL, Ueno N. Regulation of body length and male tail ray pattern formation of Caenorhabditis elegans by a member of TGF-beta family. Development. 1999;126(6):1337–1347. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.6.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray C, Sojka WJ. Experimental Salmonella typhimurium infection in calves. Res Vet Sci. 1978;25(2):139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apfeld J, Kenyon C. Regulation of lifespan by sensory perception in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1999;402(6763):804–809. doi: 10.1038/45544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alegado RA, Tan MW. Resistance to antimicrobial peptides contributes to persistence of Salmonella typhimurium in the C. elegans intestine. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10(6):1259–1273. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]