Abstract

In cardiovascular disorders including advanced atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction (MI), increased cell death and tissue destabilization is associated with recruitment of inflammatory monocyte subsets that give rise to differentiated macrophages. These phagocytic cells clear necrotic and apoptotic bodies and promote inflammation resolution and tissue remodeling. The capacity of macrophages for phagocytosis of apoptotic cells (efferocytosis), clearance of necrotic cell debris, and repair of damaged tissue are challenged and modulated by local cell stressors that include increased protease activity, oxidative stress, and hypoxia. The effectiveness, or lack thereof, of phagocyte-mediated clearance, in turn is linked to active inflammation resolution signaling pathways, susceptibility to atherothrombosis and potentially, adverse post MI cardiac remodeling leading to heart failure. Previous reports indicate that in advanced atherosclerosis, defective efferocytosis is associated with atherosclerotic plaque destabilization. Post MI, the role of phagocytes and clearance in the heart is less appreciated. Herein we contrast the roles of efferocytosis in atherosclerosis and post MI and focus on how targeted modulation of clearance and accompanying resolution and reparative signaling may be a strategy to prevent heart failure post MI.

Keywords: macrophage, phagocytosis, cardiovascular, myocardial infarction, clearance, hypoxia

Introduction

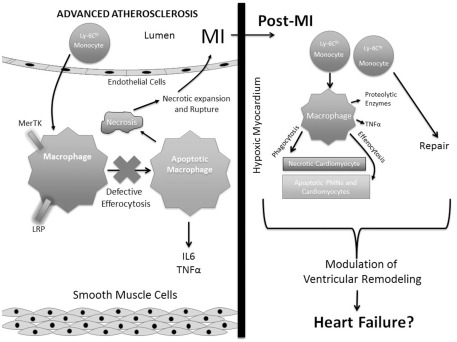

The sequence of events that are atherothrombosis, myocardial infarction (MI), and heart failure, combine to serve as a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the industrialized world (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2010). Advanced atherosclerosis and MI are mutually characterized by accelerated cell death followed by inflammatory cell recruitment. Though intimately linked, each disorder individually is distinguished by unique cell populations and cell stressors (Libby et al., 2008). In the intimal vascular wall of the atherosclerotic plaque, lipid-laden macrophage foam cells predominate after responding to retained lipoproteins that are embedded in the sub-endothelium (Williams and Tabas, 1995). As atherosclerotic lesions mature, a combinatorial array of stressors, including excess free cholesterol, pattern recognition receptor ligands, and oxidative stress, additively signal to activate cellular stress pathways, secretion of inflammatory cytokines, and accelerate apoptosis (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2010; Moore and Tabas, 2011). When combined with reduced apoptotic cell clearance efficiency (i.e., defective “efferocytosis”), this leads to secondary necrosis and plaque destabilization, the precursor to atherothrombosis (Tabas, 2005; Schrijvers et al., 2007). In turn, plaque rupture and MI lead to the release of chemotactic factors into the bloodstream and subsequent influx of neutrophils and monocytes into the heart (Kumar et al., 1997). In contrast to advanced atherosclerosis leading to MI, inflammation after a heart attack is often acute and resolving. This response is necessary to heal the heart and promote scar formation. Interestingly, recent and not-so-recent reports, suggest that modulation of the inflammatory response post MI contributes to the quality of heart repair (Roberts et al., 1976; Frangogiannis et al., 2002; Nahrendorf et al., 2007). Marginated leukocytes clear dying and necrotic cardiomyocytes and promote fibrogenic and angiogenic responses. In some cases, especially in the elderly, sub-optimal clearance efficiency may lead to maladaptive vascular remodeling and tissue repair in the healing heart and therefore accelerate transition into heart failure (Chen and Frangogiannis, 2010). Herein, we compare basic mechanisms of inflammation resolution by phagocytes in the vascular wall during atherosclerosis and in the myocardium post infarction, with a focus on monocyte/macrophage-mediated phagocytic clearance of dying tissue, particularly post MI. These concepts form a working model (Figure 1) of how clearance may modulate downstream inflammation and tissue repair in cardiovascular disease.

Figure 1.

Contrasting phagocytic clearance in advanced atherosclerosis and post myocardial infarction. Advanced atherosclerosis is characterized by recruitment of Ly-6C-HI monocytes that differentiate into macrophages. Macrophage apoptotic cell receptors, such as MerTK and LRP promote efferocytosis. However, in the inflammatory setting of mature atheromata, efferocytosis becomes defective (see Tabas, 2010) leading to secondary necrosis, necrotic core expansion, and susceptibility to myocardial infarction (MI). Post MI, both Ly-6C-HI and LO monocytes marginate into myocardial tissue to differentiate into macrophages and promote clearance of apoptotic and necrotic cells (see Nahrendorf et al., 2007). These acute events can affect later cardiac remodeling and inflammation that may lead to heart failure.

Defective Inflammation Resolution in Atherosclerosis

Though initially protective, inflammation must eventually subside in order to prevent further tissue damage. Many diseases of inflammatory cell recruitment, including advanced atherosclerosis leading to MI, are failures of inflammation to resolve that subsequently lead to tissue destabilization and injury. A key component of defective inflammation resolution in advanced atherosclerosis is defective efferocytosis (Schrijvers et al., 2007; Tabas, 2010). In non-diseased settings, apoptosis is typically followed by rapid and non-phlogistic uptake into neighboring phagocytic cells. During inflammation, active production of omega-3 poly-unsaturated fatty-acid-derived mediators promotes further phagocytic removal of dying cells (Schwab et al., 2007). The act of efferocytosis also triggers anti-inflammatory, or pro-resolving signaling that assists in dampening the immune response and restoring tissue equilibrium (Serhan and Savill, 2005). Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-β, prostaglandin E2, and platelet-activating factor (Fadok et al., 1998). An important anti-inflammatory cytokine and pro-resolving factor that is linked to efficient efferocytosis IL-10 (Lingnau et al., 2007). Both in vitro and in vivo, IL-10 has been reported to enhance efferocytosis and transgenic over-expression of IL-10 has been shown to reduce atherogenesis in experimental rodents (Pinderski et al., 2002). In humans, IL-10 levels are reduced in patients with cardiovascular disease, consistent with the notion that reduced levels of this cytokine may accelerate atherosclerotic progression (Seljeflot et al., 2004). In vitro, “alternatively” activated M2 macrophages preferentially clear apoptotic cells and are often characterized by secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and TGFβ (Xu et al., 2006). In the case of early atherosclerosis, cell turnover within the developing atherosclerotic lesion is rapidly countered by neighboring macrophage phagocytes that promote efficient efferocytosis (Tabas, 2005). Consistent with this, early atherosclerotic lesions rarely exhibit TUNEL-positive apoptotic nuclei (Kockx et al., 1999). Efficient clearance in early atheromata limits the cellular density of the lesion and may also reduce further recruitment of blood-borne monocytes. In human advanced atherosclerosis, there is an accumulation of free, non-phagocytosed apoptotic cells (Schrijvers et al., 2005). The failure of these dying cells to be removed leads to the loss of cell membrane integrity, secondary post-apoptotic necrosis, liberation of potentially immunogenic epitopes, and release of damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) that stimulate cell activation. Failed clearance may also be responsible for the aforementioned reductions in anti-inflammatory/pro-resolving mediators such as IL-10. Necrotic plaques are strongly associated with clinical acute atherothrombotic events and are a source of procoagulant materials (Kolodgie et al., 2003). It is not entirely clear why early stable atherosclerotic lesions mature into non-resolving and necrotic inflammatory advanced lesions, however recent reports in experimental mice, shed some light on key clearance pathways that may be involved, as described below.

Molecular Mechanisms of Efferocytosis in Atherosclerosis

Recognition of apoptotic cells in advanced atheromata requires bridging of apoptotic cell ligands such as phosphatidylserine, with phagocyte receptors, that trigger downstream activation of the phagocyte actin cytoskeleton. Bridging molecules, such as complement factor C1q, link apoptotic cell receptors to their apoptotic ligands (Ogden et al., 2001). During atherosclerosis for example, C1qa−/− mice on a fat–fed low density lipoprotein receptor (Ldlr) deficient background had larger atherosclerotic lesions and an increase in the number of lesional apoptotic cells, consistent with defective clearance (Bhatia et al., 2007). Another bridging molecule, milk fat globule-EGF-factor 8 (MFG-E8), a secreted glycoprotein, also links apoptotic cell receptors to their apoptotic ligands (Hanayama et al., 2002). MFGE-E8 (lactadherin) is expressed in atherosclerotic lesions and it promotes efferocytosis in vitro and in vivo. Mice lacking MFG-E8 in bone marrow precursors exhibit more necrosis and apoptotic cellular debris (Ait-Oufella et al., 2007). MFG-E8 is recognized by the macrophage cell-surface and protein cross-linking transglutaminase-2 (TG2). TG2, in cooperation with αvβ3 integrin, bind to MFG-E8 to promote efferocytosis (Toth et al., 2009). During atherosclerosis, mice reconstituted with Tg2−/− bone marrow cells exhibited larger necrotic cores relative to control (Boisvert et al., 2006). In addition, clearance of apoptotic cells also been reported to be significantly reduced in Ldlr related protein (Lrp) 1−/− lesions relative to control. By immunohistochemistry and relative to wild-type lesions, Lrp1−/− lesions exhibited more necrotic cores with more apoptotic cells not associated with macrophages (Yancey et al., 2010). LRP is activated to promote engulfment after binding calreticulin on apoptotic cells (Gardai et al., 2005). Another important efferocytosis receptor in atherosclerosis in MERTK. Mice deficient in the tyrosine kinase MER (MERTK), have a defect in macrophage efferocytosis and this correlated with an increase in plaque inflammation and plaque necrosis (Ait-Oufella et al., 2008; Thorp et al., 2008). MERTK is involved in both efferocytosis and in anti-inflammatory responses (Camenisch et al., 1999). It promotes clearance by binding to one of two bridging molecules, either GAS6 or protein S (Lemke and Rothlin, 2008). Interestingly, MERTK is proteolytically cleaved as a result of inflammatory stimuli such as LPS and this leads to the generation of a solubilized MER that can act as a competitive inhibitor of uptake (Sather et al., 2007). With the recent identification of the MERTK cleavage site, future tests will examine whether MERTK sheddase-mediated proteolysis contributes to defective efferocytosis in atherosclerosis (Thorp et al., 2011). The identification of the aforementioned key clearance players in atherosclerotic progression provides targets for testing relevance in humans with coronary artery disease. For example, in addition to soluble MER being linked to defective efferocytosis, it has also been identified in human inflammatory cardiovascular lesions (Hurtado et al., 2011). The fact that MERTK is rendered inactive through sheddase-mediated cleavage may provide a therapeutic opportunity. That is, if excess MERTK cleavage were a culprit of defective inflammation resolution through its anti-efferocytic properties in human advanced plaques, targeted inhibition of cleavage might suppress plaque necrosis and increase pro-resolving mediators as described above (Tabas, 2010). Thus, by defining the mechanisms of defective efferocytosis in vitro and establishing relevance in humans, specific hypotheses can be formulated toward designing clearance based therapeutic strategies that promote inflammation resolution. In the case of post MI inflammation and clearance, a more acute and resolving inflammation and dissimilar apoptotic and necrotic targets distinguish clearance in the heart from clearance in the vasculature, as described below.

Cardiomyocyte Clearance Post MI and Its Association with Myocardial Inflammation Resolution and Repair

Healing of the heart after interruption of blood supply and generation of an infarct requires scavenging of necrotic cellular debris and preservation of the remaining and irreplaceable cardiomyocytes. This wound repair is accomplished in part through acute mobilization of innate inflammatory cells that assist in degrading released macromolecules. The recruited phagocytes, which initially include neutrophils and monocytes, act in turn to directly remove necrotic and apoptotic cells. This is followed by formation of granulation tissue and extracellular matrix deposition. Neutrophils likely contribute to the clearance of necrotic debris from the infarct; however they also potentially damage neighboring myocytes through release of their proteolytic enzymes. Neutrophil depletion in animals post MI and reperfusion have been shown to reduce infarct size and myocardial injury (Romson et al., 1983). Neutrophils may also contribute to inflammation resolution through programmed cell death leading to efferocytosis by macrophages. Efferocytosis, as described above, induces signaling pathways that promote pro-resolving factors such as TGF-B and IL-10. Importantly, the effects of neutrophils and other myeloid cells post MI may be exacerbated during reperfusion of the infarct. For example, hallmarks of reperfusion injury post MI include the production of reactive oxygen species, mitochondrial dysfunction, and recruitment of elevated neutrophils and monocytes. These events can lead to increased myocardial injury and cardiomyocyte apoptosis that would increase the burden for dead cardiomyocyte clearance (Foo et al., 2005). Clearance per se may also be affected after reperfusion. For example, in a non-MI mouse intestinal arterial occlusion and reperfusion model, investigators found decreased levels of the “come-eat-me” mediator MFG-E8 mRNA in remote organs. Administration of rmMFG-E8 suppressed intestinal I/R injury-induced organ injury and apoptotic cell accumulation (Matsuda et al., 2011). Thus, it will be important to compare and contrast clearance roles post MI versus post MI followed by reperfusion.

Post MI, most of the initial cell death is necrotic, and therefore, this promotes the release of pro-inflammatory intracellular contents such as heat shock proteins and DAMPs. These DAMPS, or “alarmins,” activate innate phagocytes and may or may not exacerbate the repair response (Matzinger, 2002). For example, endogenous DAMPs such as HSP-60 and EDA can activate signaling pathways downstream of pattern recognition receptors. Pattern recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) activate post MI inflammation and are required for adverse myocardial left ventricular remodeling following infarction, indicating that part of the inflammatory response post MI is maladaptive (Timmers et al., 2008). This deficiency of TRL-4 is associated with reduced intercellular adhesion molecule expression and reduced monocyte homing to the infarct, in turn leading to markedly reduced myocardial inflammatory cytokine production and preservation of heart function. Importantly, clearance of dying cells is linked to phagocyte-mediated suppression of inflammation. For example, apoptotic cells promote their own clearance and activate of the nuclear receptor LXR to suppress inflammation (A-Gonzalez et al., 2009). Thus, clearance may play a role in dampening TLR-mediated inflammation post MI. Cardiomyocyte necrosis also leads to the release of mitochondrial DAMPs (MTDs). MTDs include formyl peptides and mitochondrial DNA and can activate neutrophils through formyl peptide receptor-1 and TLR signaling (Zhang et al., 2010). Due to the high energy requirements of cardiomyocytes and therefore the high density of mitochondria per cell, injury to the heart would be expected to promote a significant response to MTDs. Another intracellular factor that is released from dead cells and during acute inflammation is high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), which when located in the nucleus can act as an architectural chromatin-binding factor (Scaffidi et al., 2002). In vitro, extracellular HMGB1 has been shown to reduce macrophage efferocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils through binding to phosphatidylserine (Liu et al., 2008), suggesting that HMGB1 could delay engulfment of dying cells near and in the infarct, however, it is yet to be determined how HMGB1 affects clearance of cardiomyocytes by macrophages. Injection of HMGB1 into experimental hearts after coronary artery ligation has been shown to have beneficial effects in the heart when infused 3 weeks post MI (Takahashi et al., 2008). Also, injection of anti-HMGB1 just prior to reperfusion in rats resulted in increased infarct sizes compared to control (Oozawa et al., 2008). Multiple roles of HMGB1 are now emerging, including a regenerative role for accumulation of newly formed myocytes post MI (Limana et al., 2011) and it is becoming evident that this molecule can act at multiple levels, with an apparent overall beneficial effect. Downstream of DAMP and PRR signaling is NF-κB. NF-κB activity is elevated in both myocardial and inflammatory cells in ischemic heart disease (Frantz et al., 2004), however, the overall effect of NF-κB remains incomplete. Deletion of the p50 subunit of the NF-κB complex has been shown to improve heart failure after MI (Frantz et al., 2006), suggesting a role for maladaptive signaling post MI. In addition, transgenic over-expression of NF-κB p65 in myocytes resulted in adverse cardiac remodeling and increased endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes post MI (Hamid et al., 2011), indicating that persistent NF-κB activation exacerbates cardiac remodeling. However, another study reported that NF-κB p50 deletion exacerbates cardiac function post MI, consistent with a cardioprotective role (Timmers et al., 2009). The role of the NF-kB is complex. Though predominantly associated with pro-inflammatory responses, NF-kB has also been linked to the resolution of inflammation. For example, NF-kB activation during inflammation resolution is associated with expression of anti-inflammatory genes and induction of apoptosis (Lawrence et al., 2001). The NF-kB complex includes RelA (p65), RelB, c-Rel, p50, and p52, as well as inhibitory IkB and stimulatory IkBkinse (IKK) regulators. NF-κB can form homodimers or heterodimers depending on its mode of activation. Only p65, c-Rel, and RelB contain transactivation domains, whereas p50 and p52 do not and can act to suppress gene transcription (Vallabhapurapu and Karin, 2009). NF-κB can also be directly regulated by receptors involved in efferocytosis per se. For example, in the case of the efferocytosis receptor tyrosine kinase, MERTK, suppression of NF-κB transcriptional activation is directly associated with downstream inflammatory signaling (Tibrewal et al., 2008). Thus, the overall role of NF-κBin heart failure is far from understood and future experiments are required to elucidate both cell-type specific effects (myocardial versus inflammatory) and how the kinetics of NF-κB activation may differentially affect inflammation versus inflammation resolution in the heart.

Though innate inflammatory activation may at certain levels promote adverse effects on the heart after injury, inflammation is nevertheless necessary to clear away dead cardiac tissue and begin inflammation resolution, as described below. Resolution of inflammation is not a passive process and instead relies on biosynthesis of pro-resolving mediators. Many of these mediators are derived from poly-unsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), including lipoxins, E-series resolvins, D-series resolvins, protectins, and, maresins (Serhan and Savill, 2005). One interesting resolvin is Resolvin E1. Resolvin E1, has been shown to promote the efferocytosis of neutrophils in vitro and in vivo (Schwab et al., 2007). In the context of the heart, Resolvin E1, which is derived from eicosapentaenoic acid, has been shown to directly protect cardiomyocyte cell lines from ischemia-reperfusion injury in vitro and in addition, limit infarct size after prophylactic injection (Keyes et al., 2010). Though pro-survival molecules in cardiomyocytes, such as AKT, were up-regulated, further experiments are required to determine mechanism at the causal level. Recently, the receptor for Resolvin E1 was identified as ChemR23, otherwise known as CMKLR1 (Ohira et al., 2010). Future studies utilizing knockout models of this receptor are required during MI. Thus, not only will pathways that suppress acute-phase inflammation be required, but also pathways that target active pro-resolution pathways, potentially downstream of efferocytosis. As one such proof of principle that such an approach is feasible and linked to phagocytic clearance, Harel-Adar et al. (2011) by simulating a macrophage response to an apoptotic cell, were able to modulate the activity of cardiac macrophages to improve infarct repair, post experimental MI. Specifically, the investigators injected phosphatidylserine (PS)-presenting liposomes intravenously to mimic the anti-inflammatory effects of apoptotic cells. Both in a rat model of acute MI, and in vitro, PS-liposome uptake by macrophages promoted the secretion of the anti-inflammatory cytokines TGFβ and IL-10. This was accompanied by down-regulation of pro-inflammatory tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα). Thus, an exciting proof of concept that modulation of macrophage pathways related to clearance may have therapeutic application and promote inflammation resolution.

Similar to atherosclerosis, the levels of IL-10 may be important in reducing inflammation post MI. For example, IL-10 deficient mice exhibited increased infarct size and myocardial necrosis associated with elevated neutrophil infiltration (Yang et al., 2000). IL-10 also inhibits inflammation and attenuates left ventricular remodeling after MI via activation of STAT3 and suppression of mRNA stabilizing protein HuR (Krishnamurthy et al., 2009). As further evidence that the type of inflammatory response may dictate post MI repair, Cheng et al. (2005) found IFN-gamma producing T-cells were significantly increased in patients post MI, creating a Th1/Th2 imbalance. Also, in patients with acute MI, significant increases in Th17 cytokines were found concomitant with reduced levels of T-regulatory associated cytokines (Cheng et al., 2008). Finally, monocytes and macrophages secrete growth factors that can promote angiogenesis, specifically through targeting and activating myofibroblasts. Myofibroblasts secrete extracellular matrix and accumulate within the first week after an infarct (van den Borne et al., 2010). These cells are critical for scar formation and prevention of cardiac dilation. However, too much matrix deposition, particularly at areas remote to the infarct, can also lead to heart failure. Thus, fine-tuned modulation of the immune response post MI appears to be required to promote resolution pathways while suppressing maladaptive/excessive inflammation.

Certainly, the aforementioned example whereby infarct repair was improved after injection of PS-liposomes suggests there is indeed potential for inflammation-modulating agents during myocardial reperfusion, particularly at the level of clearance. Such a strategy may be proven even more efficacious if tested in a population that more closely resembles the advanced age of the average victim of MI. That is, older age is associated with increased mortality after a heart attack. In addition, aging-related defects have been reported to be associated with adverse cardiac remodeling in experimental mice. Specifically, Frangogiannis et al. (2002) showed by both histomorphometric and echocardiographic end points, that older mice exhibit significantly reduced neutrophil and macrophage infiltration after coronary ligation, and in turn, impaired phagocytosis of dead cardiomyocytes. This led to enhanced dilative and poor systolic function (Bujak et al., 2008). Additional analysis revealed reduced collagen deposition and hypertrophic remodeling in these hearts. The reduced inflammation seen in aged mice can also be measured in experimental models that inhibit inflammatory cell recruitment. For example, the effects of reduced macrophage recruitment have been tested in a model of MCP-1/CCL2 deficiency. Lack of MCP-1 is associated with delayed macrophage infiltration into the heart and delayed replacement of injured cardiomyocytes with granulation tissue (Dewald et al., 2005). In this scenario, reduced levels of myeloid cell infiltration was associated with delayed dying cell clearance and impaired healing. However, in the reverse direction, that is, excessive inflammation in the setting of atherosclerotic hyperlipidemia, Nahrendorf et al. (2007) examined the inflammatory response post MI in atherogenic apolipoprotein E deficient mice and discovered that a subset of monocytes, the Ly-6C(hi) and CCR2-recruited subset, were markedly elevated and this also correlated with impaired heart healing (Panizzi et al., 2010). The injured myocardium exhibited elevated inflammatory gene expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, myeloperoxidase, and decreased transforming growth factor-beta and a higher abundance of proteases. Previous work from the same group identified two distinct phases of monocyte action post MI. In non-atherosclerotic (i.e., non-apoE-deficient mice), Ly-6C(hi) monocytes were the first to be recruited to the heart and were highly phagocytic. Though increased Ly-6c (hi) monocytosis in apoE deficient mice were detrimental, depletion of Ly-6c (hi) monocytes under non-dyslipidemic, non-apoE-deficient mice resulted in impaired heart healing, indicating a contribution of dyslipidemia to adversely modulateLy-6c (hi) function during heart inflammation. Ly-6C(lo) monocytes enter later and expressed vascular-endothelial growth factor and therefore promoted healing via myofibroblast accumulation, angiogenesis, and deposition of collagen (Nahrendorf et al., 2007).

Oxygen and Clearance in the Heart

Reduced perfusion to the infarct reduces nutrient availability and therefore stresses cellular metabolism. Low oxygen tensions and nutrient deprivation lead to the induction of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors (HIF) in phagocytes. During normoxia, HIF-1α protein is constitutively degraded. During hypoxia, HIF-1α is stabilized and translocates to the nucleus, where it dimerizes with HIF-1β, and acts as a transcription factor for gene elements encoding hypoxic response elements (Maxwell et al., 1999). HIF-1α mRNA can be detected in myocardial specimens with pathological evidence of acute ischemia within the first day post MI (Lee et al., 2000). In phagocytes, HIF isoforms mobilize and differentially coordinate intracellular signaling that regulate cell migration, glycolysis, cell-survival, and inflammatory cytokine secretion (Cramer et al., 2003). Deficiency of myeloid HIF-1α has been shown to reduce infiltration of leukocytes and improve cardiac function post MI. This reduced infiltration has been linked to the down-regulation of chemokine receptors (Dong et al., 2010). With respect to how oxygen tension affects clearance in the heart, little is known. In vitro, hypoxia promotes the phagocytosis of bacteria by macrophages, and this has been linked to p38 MAPK signaling (Anand et al., 2007). Less is known regarding effects of apoptotic cell clearance by macrophages during hypoxia, however, in retinal pigment epithelial cells, hypoxia enhanced efferocytosis concomitant with upregulation of the clearance receptor CD36 (Mwaikambo et al., 2009). In contrast, hypoxia has also been shown to potentiate secretion of factors that can inhibit phagocytosis (Wei et al., 2011). Finally, during reperfusion, the restoration of blood and oxygen can also promote additional myocardial damage and elevated reactive oxygen species as described above. Our understanding of how these factors intersect during ischemia to regulate phagocyte-mediated clearance and inflammation resolution, remain incomplete.

Future Directions

Cardiovascular disease is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Ischemic heart failure is on the rise, part and parcel with an increase in the aged population, who are at highest risk of cardiovascular disease. In addition, better therapeutics have led to the propensity of patients to survive acute coronary events such as MI (Stewart et al., 2003). Both atherosclerosis and MI are characterized by increased cell death. In the case of atherosclerosis, genetic causation experiments indicate that clearance factors are a required pathway toward reducing inflammation and stabilizing vulnerable plaques. Acute MI can lead to the loss of irreplaceable cardiomyocytes, deleterious ventricular remodeling, and reduced cardiac output. Despite significant advances in current standards of therapy, the prevalence of post MI heart failure remains high. Post MI, the causal demonstration of clearance pathways and how they affect post MI repair directly are still unknown. Thus, the magnitude of how clearance affects the heart is yet to be determined and must be formally tested. However, apoptotic cell death is programmed to lead to compartmentalization and non-phlogistic metabolism of intracellular self-antigens, and additionally, to activate pro-resolving signaling (Serhan and Savill, 2005). That is, given that phagocytosis of necrotic debris and clearance of apoptotic cells are intimately linked to downstream signaling pathways that modulate inflammation resolution and tissue repair, targeting of the innate immune system may be a strategy toward reducing adverse cardiac remodeling that leads to heart failure. Thus, in our working model (Figure 1), we and others propose a need for efficient clearance pathways to promote dying cell engulfment in the heart that are coupled to downstream pro-resolving pathways that also suppress inflammation. In the case of advanced atherosclerosis, enhancing efferocytosis efficiency has previously been proposed as a critical step (Tabas, 2005). In the case of failed inflammation resolution leading to MI, optimizing cardiac repair pathways that lead to efficient cardiac output will also be required to prevent heart failure. Toward these ends, it will be important to elucidate the causal molecular pathways that regulate tissue repair during wound healing. This will include testing the effects of heart failure risk factors, including abnormal metabolism and aging. These approaches will be tested with methods of cell and molecular biology, both in vitro and in gene-targeted in vivo models. In addition, the effects of clearance during reperfusion injury, such as occurs in the clinical setting will also have to be addressed. By defining the critical molecular pathways required for an optimal immune response, a pathway can be discovered toward promoting inflammation resolution and reducing myocardial necrosis and heart failure. In atherosclerosis, strategies to enhance clearance are currently being tested toward stabilizing plaque (Tabas, 2010). Post MI, not only will therapeutics that potentiate effective clearance be a testable strategy, but it will also be key to find the right balance of inflammation that promotes effective clearance of dying and dead tissue while limiting maladaptive inflammation.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge and appreciate previous discussions with Ira Tabas. I also acknowledge Jeremy Lipsitz for the creation of the figure. Funding from NIH 4R00HL097021-03 grant from the NHLBI (to Edward B. Thorp).

References

- A-Gonzalez N., Bensinger S. J., Hong C., Beceiro S., Bradley M. N., Zelcer N., Deniz J., Ramirez C., Díaz M., Gallardo G., de Galarreta C. R., Salazar J., Lopez F., Edwards P., Parks J., Andujar M., Tontonoz P., Castrillo A. (2009). Apoptotic cells promote their own clearance and immune tolerance through activation of the nuclear receptor LXR. Immunity 31, 245–258 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ait-Oufella H., Kinugawa K., Zoll J., Simon T., Boddaert J., Heeneman S., Blanc-Brude O., Barateau V., Potteaux S., Merval R., Esposito B., Teissier E., Daemen M. J., Lesèche G., Boulanger C., Tedgui A., Mallat Z. (2007). Lactadherin deficiency leads to apoptotic cell accumulation and accelerated atherosclerosis in mice. Circulation 115, 2168–2177 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.662080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ait-Oufella H., Pouresmail V., Simon T., Blanc-Brude O., Kinugawa K., Merval R., Offenstadt G., Lesèche G., Cohen P. L., Tedgui A., Mallat Z. (2008). Defective mer receptor tyrosine kinase signaling in bone marrow cells promotes apoptotic cell accumulation and accelerates atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 1429–1431 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.169078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand R. J., Gribar S. C., Li J., Kohler J. W., Branca M. F., Dubowski T., Sodhi C. P., Hackam D. J. (2007). Hypoxia causes an increase in phagocytosis by macrophages in a HIF-1alpha-dependent manner. J. Leukoc. Biol. 82, 1257–1265 10.1189/jlb.0307195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia V. K., Yun S., Leung V., Grimsditch D. C., Benson G. M., Botto M. B., Boyle J. J., Haskard D. O. (2007). Complement C1q reduces early atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Am. J. Pathol. 170, 416–426 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert W. A., Rose D. M., Boullier A., Quehenberger O., Sydlaske A., Johnson K. A., Curtiss L. K., Terkeltaub R. (2006). Leukocyte transglutaminase 2 expression limits atherosclerotic lesion size. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26, 563–569 10.1161/01.ATV.0000203503.82693.c1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujak M., Kweon H. J., Chatila K., Li N., Taffet G., Frangogiannis N. G. (2008). Aging-related defects are associated with adverse cardiac remodeling in a mouse model of reperfused myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 51, 1384–1392 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camenisch T. D., Koller B. H., Earp H. S., Matsushima G. K. (1999). A novel receptor tyrosine kinase, Mer, inhibits TNF-alpha production and lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxic shock. J. Immunol. 162, 3498–3503 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Frangogiannis N. G. (2010). The role of inflammatory and fibrogenic pathways in heart failure associated with aging. Heart Fail. Rev. 15, 415–422 10.1007/s10741-010-9161-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X., Liao Y. H., Ge H., Li B., Zhang J., Yuan J., Wang M., Liu Y., Guo Z., Chen J., Zhang J., Zhang L. (2005). TH1/TH2 functional imbalance after acute myocardial infarction: coronary arterial inflammation or myocardial inflammation. J. Clin. Immunol. 25, 246–253 10.1007/s10875-005-4088-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X., Yu X., Ding Y. J., Fu Q. Q., Xie J. J., Tang T. T., Yao R., Chen Y., Liao Y. H. (2008). The Th17/Treg imbalance in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Clin. Immunol. 127, 89–97 10.1016/j.clim.2008.03.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer T., Yamanishi Y., Clausen B. E., Förster I., Pawlinski R., Mackman N., Haase V. H., Jaenisch R., Corr M., Nizet V., Firestein G. S., Gerber H. P., Ferrara N., Johnson R. S. (2003). HIF-1alpha is essential for myeloid cell-mediated inflammation. Cell 112, 645–657 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00154-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewald O., Zymek P., Winkelmann K., Koerting A., Ren G., Abou-Khamis T., Michael L. H., Rollins B. J., Entman M. L., Frangogiannis N. G. (2005). CCL2/monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 regulates inflammatory responses critical to healing myocardial infarcts. Circ. Res. 96, 881–889 10.1161/01.RES.0000163017.13772.3a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong F., Khalil M., Kiedrowski M., O’Connor C., Petrovic E., Zhou X., Penn M. S. (2010). Critical role for leukocyte hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha expression in post-myocardial infarction left ventricular remodeling. Circ. Res. 106, 601–610 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadok V. A., Bratton D. L., Konowal A., Freed P. W., Westcott J. Y., Henson P. M. (1998). Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit proinflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-beta, PGE2, and PAF. J. Clin. Invest. 101, 890–898 10.1172/JCI1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo R. S., Mani K., Kitsis R. N. (2005). Death begets failure in the heart. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 565–571 10.1172/JCI200524569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frangogiannis N. G., Smith C. W., Entman M. L. (2002). The inflammatory response in myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Res. 53, 31–47 10.1016/S0008-6363(01)00434-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantz S., Hu K., Bayer B., Gerondakis S., Strotmann J., Adamek A., Ertl G., Bauersachs J. (2006). Absence of NF-kappaB subunit p50 improves heart failure after myocardial infarction. FASEB J. 20, 1918–1920 10.1096/fj.05-5133fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frantz S., Stoerk S., Ok S., Wagner H., Angermann C. E., Ertl G., Bauersachs J. (2004). Effect of chronic heart failure on nuclear factor kappa B in peripheral leukocytes. Am. J. Cardiol. 94, 671–673 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardai S. J., McPhillips K. A., Frasch S. C., Janssen W. J., Starefeldt A., Murphy-Ullrich J. E., Bratton D. L., Oldenborg P. A., Michalak M., Henson P. M. (2005). Cell-surface calreticulin initiates clearance of viable or apoptotic cells through trans-activation of LRP on the phagocyte. Cell 123, 321–334 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid T., Guo S. Z., Kingery J. R., Xiang X., Dawn B., Prabhu S. D. (2011). Cardiomyocyte NF-kappaB p65 promotes adverse remodelling, apoptosis, and endoplasmic reticulum stress in heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 89, 129–138 10.1093/cvr/cvq274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanayama R., Tanaka M., Miwa K., Shinohara A., Iwamatsu A., Nagata S. (2002). Identification of a factor that links apoptotic cells to phagocytes. Nature 417, 182–187 10.1038/417182a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel-Adar T., Ben Mordechai T., Amsalem Y., Feinberg M. S., Leor J., Cohen S. (2011). Modulation of cardiac macrophages by phosphatidylserine-presenting liposomes improves infarct repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 1827–1832 10.1073/pnas.1015623108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado B., Munoz X., Recarte-Pelz P., García N., Luque A., Krupinski J., Sala N., García de Frutos P. (2011). Expression of the vitamin K-dependent proteins GAS6 and protein S and the TAM receptor tyrosine kinases in human atherosclerotic carotid plaques. Thromb. Haemost. 105, 873–882 10.1160/TH10-10-0630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes K. T., Ye Y., Lin Y., Zhang C., Perez-Polo J. R., Gjorstrup P., Birnbaum Y. (2010). Resolvin E1 protects the rat heart against reperfusion injury. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 299, H153–H164 10.1152/ajpheart.01057.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kockx M., Muhring J., Knaapen M. (1999). Detection of apoptosis in atherosclerosis and restenosis by terminal dUTP Nick-end labeling (TUNEL). Methods Mol. Med. 30, 223–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolodgie F. D., Gold H. K., Burke A. P., Fowler D. R., Kruth H. S., Weber D. K., Farb A., Guerrero L. J., Hayase M., Kutys R., Narula J., Finn A. V., Virmani R. (2003). Intraplaque hemorrhage and progression of coronary atheroma. N. Engl. J. Med. 349, 2316–2325 10.1056/NEJMoa035655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy P., Rajasingh J., Lambers E., Qin G., Losordo D. W., Kishore R. (2009). IL-10 inhibits inflammation and attenuates left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction via activation of STAT3 and suppression of HuR. Circ. Res. 104, e9–e18 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.188243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A. G., Ballantyne C. M., Michael L. H., Kukielka G. L., Youker K. A., Lindsey M. L., Hawkins H. K., Birdsall H. H., MacKay C. R., LaRosa G. J., Rossen R. D., Smith C. W., Entman M. L. (1997). Induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in the small veins of the ischemic and reperfused canine myocardium. Circulation 95, 693–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence T., Gilroy D. W., Colville-Nash P. R., Willoughby D. A. (2001). Possible new role for NF-kappaB in the resolution of inflammation. Nat. Med. 7, 1291–1297 10.1038/86397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. H., Wolf P. L., Escudero R., Deutsch R., Jamieson S. W., Thistlethwaite P. A. (2000). Early expression of angiogenesis factors in acute myocardial ischemia and infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 342, 626–633 10.1056/NEJM200003023420904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke G., Rothlin C. V. (2008). Immunobiology of the TAM receptors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 327–336 10.1038/nri2303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby P., Nahrendorf M., Pittet M. J., Swirski F. K. (2008). Diversity of denizens of the atherosclerotic plaque: not all monocytes are created equal. Circulation 117, 3168–3170 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.783068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limana F., Esposito G., D’Arcangelo D., Di Carlo A., Romani S., Melillo G., Mangoni A., Bertolami C., Pompilio G., Germani A., Capogrossi M. C. (2011). HMGB1 attenuates cardiac remodelling in the failing heart via enhanced cardiac regeneration and miR-206-mediated inhibition of TIMP-3. PLoS ONE 6, e19845. 10.1371/journal.pone.0019845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingnau M., Höflich C., Volk H. D., Sabat R., Döcke W. D. (2007). Interleukin-10 enhances the CD14-dependent phagocytosis of bacteria and apoptotic cells by human monocytes. Hum. Immunol. 68, 730–738 10.1016/j.humimm.2007.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., Wang J., Park Y. J., Tsuruta Y., Lorne E. F., Zhao X., Abraham E. (2008). High mobility group protein-1 inhibits phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils through binding to phosphatidylserine. J. Immunol. 181, 4240–4246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Jones D., Adams R. J., Brown T. M., Carnethon M., Dai S., De Simone G., Ferguson T. B., Ford E., Furie K., Gillespie C., Go A., Greenlund K., Haase N., Hailpern S., Ho P. M., Howard V., Kissela B., Kittner S., Lackland D., Lisabeth L., Marelli A., McDermott M. M., Meigs J., Mozaffarian D., Mussolino M., Nichol G., Roger V. L., Rosamond W., Sacco R., Sorlie P., Stafford R., Thom T., Wasserthiel-Smoller S., Wong N. D., Wylie-Rosett J., American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee (2010). Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics – 2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 121, 948–954 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.849166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda A., Jacob A., Wu R., Zhou M., Nicastro J. M., Coppa G. F., Wang P. (2011). Milk fat globule-EGF factor VIII in sepsis and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Mol. Med. 17, 126–133 10.2119/molmed.2010.00135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzinger P. (2002). The danger model: a renewed sense of self. Science 296, 301–305 10.1126/science.1071059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell P. H., Wiesener M. S., Chang G. W., Clifford S. C., Vaux E. C., Cockman M. E., Wykoff C. C., Pugh C. W., Maher E. R., Ratcliffe P. J. (1999). The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature 399, 271–275 10.1038/20459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore K. J., Tabas I. (2011). Macrophages in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Cell 145, 341–355 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwaikambo B. R., Yang C., Chemtob S., Hardy P. (2009). Hypoxia up-regulates CD36 expression and function via hypoxia-inducible factor-1- and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent mechanisms. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 26695–26707 10.1074/jbc.M109.033480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahrendorf M., Swirski F. K., Aikawa E., Stangenberg L., Wurdinger T., Figueiredo J. L., Libby P., Weissleder R., Pittet M. J. (2007). The healing myocardium sequentially mobilizes two monocyte subsets with divergent and complementary functions. J. Exp. Med. 204, 3037–3047 10.1084/jem.20070885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden C. A., deCathelineau A., Hoffmann P. R., Bratton D., Ghebrehiwet B., Fadok V. A., Henson P. M. (2001). C1q and mannose binding lectin engagement of cell surface calreticulin and CD91 initiates macropinocytosis and uptake of apoptotic cells. J. Exp. Med. 194, 781–795 10.1084/jem.194.6.781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohira T., Arita M., Omori K., Recchiuti A., Van Dyke T. E., Serhan C. N. (2010). Resolvin E1 receptor activation signals phosphorylation and phagocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 3451–3461 10.1074/jbc.M109.044131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oozawa S., Mori S., Kanke T., Takahashi H., Liu K., Tomono Y., Asanuma M., Miyazaki I., Nishibori M., Sano S. (2008). Effects of HMGB1 on ischemia-reperfusion injury in the rat heart. Circ. J. 72, 1178–1184 10.1253/circj.72.1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panizzi P., Swirski F. K., Figueiredo J. L., Waterman P., Sosnovik D. E., Aikawa E., Libby P., Pittet M., Weissleder R., Nahrendorf M. (2010). Impaired infarct healing in atherosclerotic mice with Ly-6C(hi) monocytosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55, 1629–1638 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinderski L. J., Fischbein M. P., Subbanagounder G., Fishbein M. C., Kubo N., Cheroutre H., Curtiss L. K., Berliner J. A., Boisvert W. A. (2002). Overexpression of interleukin-10 by activated T lymphocytes inhibits atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient Mice by altering lymphocyte and macrophage phenotypes. Circ. Res. 90, 1064–1071 10.1161/01.RES.0000018941.10726.FA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R., DeMello V., Sobel B. E. (1976). Deleterious effects of methylprednisolone in patients with myocardial infarction. Circulation 53(Suppl. 3), I204–I206 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romson J. L., Hook B. G., Kunkel S. L., Abrams G. D., Schork M. A., Lucchesi B. R. (1983). Reduction of the extent of ischemic myocardial injury by neutrophil depletion in the dog. Circulation 67, 1016–1023 10.1161/01.CIR.67.5.1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sather S., Kenyon K. D., Lefkowitz J. B., Liang X., Varnum B. C., Henson P. M., Graham D. K. (2007). A soluble form of the Mer receptor tyrosine kinase inhibits macrophage clearance of apoptotic cells and platelet aggregation. Blood 109, 1026–1033 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaffidi P., Misteli T., Bianchi M. E. (2002). Release of chromatin protein HMGB1 by necrotic cells triggers inflammation. Nature 418, 191–195 10.1038/nature00858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrijvers D. M., De Meyer G. R., Herman A. G., Martinet W. (2007). Phagocytosis in atherosclerosis: molecular mechanisms and implications for plaque progression and stability. Cardiovasc. Res. 73, 470–480 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrijvers D. M., De Meyer G. R., Kockx M. M., Herman A. G., Martinet W. (2005). Phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages is impaired in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25, 1256–1261 10.1161/01.ATV.0000166517.18801.a7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab J. M., Chiang N., Arita M., Serhan C. N. (2007). Resolvin E1 and protectin D1 activate inflammation-resolution programmes. Nature 447, 869–874 10.1038/nature05877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seljeflot I., Hurlen M., Solheim S., Arnesen H. (2004). Serum levels of interleukin-10 are inversely related to future events in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2, 350–352 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00676.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan C. N., Savill J. (2005). Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat. Immunol. 6, 1191–1197 10.1038/ni1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart S., MacIntyre K., Capewell S., McMurray J. J. (2003). Heart failure and the aging population: an increasing burden in the 21st century? Heart 89, 49–53 10.1136/heart.89.3.342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabas I. (2005). Consequences and therapeutic implications of macrophage apoptosis in atherosclerosis: the importance of lesion stage and phagocytic efficiency. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25, 2255–2264 10.1161/01.ATV.0000184783.04864.9f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabas I. (2010). Macrophage death and defective inflammation resolution in atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 36–46 10.1038/nri2675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K., Fukushima S., Yamahara K., Yashiro K., Shintani Y., Coppen S. R., Salem H. K., Brouilette S. W., Yacoub M. H., Suzuki K. (2008). Modulated inflammation by injection of high-mobility group box 1 recovers post-infarction chronically failing heart. Circulation 118(Suppl. 14), S106–S114 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.757443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorp E., Cui D., Schrijvers D. M., Kuriakose G., Tabas I. (2008). Mertk receptor mutation reduces efferocytosis efficiency and promotes apoptotic cell accumulation and plaque necrosis in atherosclerotic lesions of apoe-/- mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 1421–1428 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.167197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorp E., Vaisar T., Subramanian M., Mautner L., Blobel C., Tabas I. (2011). Shedding of the MER tyrosine kinase receptor is mediated by ADAM17 through a pathway involving reactive oxygen species, protein kinase {delta}, and P38 map kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 33335–33344 10.1074/jbc.M111.263020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibrewal N., Wu Y., D’Mello V., Akakura R., George T. C., Varnum B., Birge R. B. (2008). Autophosphorylation docking site Tyr-867 in Mer receptor tyrosine kinase allows for dissociation of multiple signaling pathways for phagocytosis of apoptotic cells and down-modulation of lipopolysaccharide-inducible NF-kappaB transcriptional activation. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 3618–3627 10.1074/jbc.M706906200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers L., Sluijter J. P., van Keulen J. K., Hoefer I. E., Nederhoff M. G., Goumans M. J., Doevendans P. A., van Echteld C. J., Joles J. A., Quax P. H., Piek J. J., Pasterkamp G., de Kleijn D. P. (2008). Toll-like receptor 4 mediates maladaptive left ventricular remodeling and impairs cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 102, 257–264 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.158220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmers L., van Keulen J. K., Hoefer I. E., Meijs M. F., van Middelaar B., den Ouden K., van Echteld C. J., Pasterkamp G., de Kleijn D. P. (2009). Targeted deletion of nuclear factor kappaB p50 enhances cardiac remodeling and dysfunction following myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 104, 699–706 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.189746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth B., Garabuczi E., Sarang Z., Vereb G., Vámosi G., Aeschlimann D., Blaskó B., Bécsi B., Erdõdi F., Lacy-Hulbert A., Zhang A., Falasca L., Birge R. B., Balajthy Z., Melino G., Fésüs L., Szondy Z. (2009). Transglutaminase 2 is needed for the formation of an efficient phagocyte portal in macrophages engulfing apoptotic cells. J. Immunol. 182, 2084–2092 10.4049/jimmunol.0803444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallabhapurapu S., Karin M. (2009). Regulation and function of NF-kappaB transcription factors in the immune system. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 693–733 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Borne S. W., Diez J., Blankesteijn W. M., Verjans J., Hofstra L., Narula J. (2010). Myocardial remodeling after infarction: the role of myofibroblasts. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 7, 30–37 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J., Wu A., Kong L. Y., Wang Y., Fuller G., Fokt I., Melillo G., Priebe W., Heimberger A. B. (2011). Hypoxia potentiates glioma-mediated immunosuppression. PLoS ONE 6, e16195. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K. J., Tabas I. (1995). The response-to-retention hypothesis of early atherogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 15, 551–561 10.1161/01.ATV.15.5.551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Roos A., Daha M. R., van Kooten C. (2006). Dendritic cell and macrophage subsets in the handling of dying cells. Immunobiology 211, 567–575 10.1016/j.imbio.2006.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey P. G., Blakemore J., Ding L., Fan D., Overton C. D., Zhang Y., Linton M. F., Fazio S. (2010). Macrophage LRP-1 controls plaque cellularity by regulating efferocytosis and Akt activation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 30, 787–795 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.202051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Zingarelli B., Szabó C. (2000). Crucial role of endogenous interleukin-10 production in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation 101, 1019–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Raoof M., Chen Y., Sumi Y., Sursal T., Junger W., Brohi K., Itagaki K., Hauser C. J. (2010). Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature 464, 104–107 10.1038/nature08780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]