Abstract

The host response following malaria infection depends on a fine balance between levels of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators resulting in the resolution of the infection or immune-mediated pathology. Whilst other components of the innate immune system contribute to the pro-inflammatory milieu, T cells play a major role. For blood-stage malaria, CD4+ and γδ T cells are major producers of the IFN-γ that controls parasitemia, however, a role for TH17 cells secreting IL-17A and other cytokines, including IL-17F and IL-22 has not yet been investigated in malaria. TH17 cells have been shown to play a role in some protozoan infections, but they also are a source of pro-inflammatory cytokines known to be involved in protection or pathogenicity of infections. In the present study, we have investigated whether IL-17A and IL-22 are induced during a Plasmodium chabaudi infection in mice, and whether these cytokines contribute to either protection or to pathology induced during the infection. Although small numbers of IL-17- and IL-22-producing CD4 T cells are induced in the spleens of infected mice, a more pronounced induction is observed in the liver, where increases in mRNA for IL-17A and, to a lesser extent, IL-22 were observed and CD8+ T cells, rather than CD4 T cells, are a major source of these cytokines in this organ. Although the lack of IL-17 did not affect the outcome of infection or pathology, lack of IL-22 resulted in 50% mortality within 12 days after infection with significantly greater weight loss at the peak of infection and significant increase in alanine transaminase in the plasma in the acute infection. As parasitemias and temperature were similar in IL-22 KO and wild-type control mice, our observations support the idea that IL-22 but not IL-17 provides protection from the potentially lethal effects of liver damage during a primary P. chabaudi infection.

Keywords: TH17, IL-17, IL-22, malaria, Plasmodium chabaudi, liver damage

Introduction

The outcome of infection with the malaria parasite is determined by factors affecting the tight balance in the kinetics and magnitude of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokine produced by the innate and acquired immune response (Langhorne et al., 2008). In Plasmodium (P.) chabaudi infections in mice, TH1 CD4+ T cells play a dual role: mediating protective immunity, together with B cells during blood-stage infection (Meding and Langhorne, 1991), and contributing to severe inflammation and pathogenesis through the production of IFN-γ (Li et al., 2003). However, since the identification of TH17 cells (Mangan et al., 2006; Veldhoen et al., 2006) and the discovery of the plasticity of T cell cytokine responses (Zhou et al., 2009; O’Shea and Paul, 2010), the TH1/TH2 paradigm in infections has been revisited, and protection or immunopathology has also been attributed to other cells types such as TH17 cells in some infection models (Awasthi and Kuchroo, 2009). Although the involvement of pro-inflammatory cytokines derived from CD4+ TH1 cells in either immunopathology or immunity to malaria has been extensively investigated, any role of the cytokines IL-17 and IL-22 produced by TH17 cells or other cells remains undetermined in P. chabaudi infections. In addition, since TH17 cells themselves have a considerable plasticity, they could also be a potential source of IFN-γ (Kurschus et al., 2010), which hitherto was thought to be produced mainly by CD4+ TH1 cells in malaria infections.

TH17 cells are identified and distinguished by their ability to secrete IL-17A and other cytokines, including IL-17F and IL-22. They can coordinate local tissue inflammation through the up-regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines including IL-6, IL-8, G-CSF, and MCP-1, recruiting neutrophils and activating T cells (Aggarwal et al., 2003; Moseley et al., 2003). Moreover, TH17 cells were shown to have the ability to produce both IFN-γ and IL-17, or, in vitro, to shut off IL-17 production (Annunziato et al., 2007; Bending et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2009; Hirota et al., 2011). Although IL-17A was shown at first to play a major role in the pathogenesis of various autoimmune diseases in mouse models (Langrish et al., 2005; Ivanov et al., 2006; Komiyama et al., 2006; Steinman, 2007) induction of TH17 cells has also been described in infections of Toxoplasma gondii (Kelly et al., 2005) and Leishmania (Pitta et al., 2009), suggesting that they may play a role in protection or immunopathology of parasitic diseases.

IL-22 is regulated by IL-23, differently from IL-17, and can be co-expressed with IL-17A in TH17 cells (Liang et al., 2006; Zheng et al., 2007). Its production by TH17 cells is dependent on Notch signaling and the stimulation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR; Veldhoen et al., 2008; Alam et al., 2010). In fact, the induction of c-Maf, downstream of TFG-β, has been demonstrated as inducing suppression of IL-22 production in TH17 cells (Rutz et al., 2011). IL-22 is also produced by NKT cells (Goto et al., 2009), TH1, innate lymphoid cells (Taube et al., 2011), and NK cells (Ren et al., 2011). IL-22 production is increased during chronic inflammatory diseases. For example, it has been linked to tuberculosis (Matthews et al., 2011), and dermal inflammation such as psoriasis, where it induces production of antimicrobial proteins needed for the defense against pathogens in the skin (Wolk et al., 2004; Sonnenberg et al., 2011) and gut (Aujla et al., 2008). IL-22 also plays a protective role in hepatitis (Radaeva et al., 2004; Xu et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011). Therefore, depending on the tissues, TH17-derived IL-22 might either enhance inflammation or limit the tissue damage induced by IL-17A (Wolk and Sabat, 2006; Zenewicz et al., 2007). There have been very few studies investigating IL-17 or IL-22 in malaria, although one study in West Africa identified polymorphisms in the IL-22 gene which are associated with resistance and susceptibility (Koch et al., 2005) suggesting a potential involvement of IL-22, and a second study in macaque malaria/AIDS-virus co-infection model, has demonstrated a protective role for IL-17 and IL-22, via TH1 response inhibition (Ryan-Payseur et al., 2011). In the present study we have investigated whether IL-17A and/or IL-22 are induced during a P. chabaudi infection in mice, and whether these cytokines contribute to either protection or to pathology induced during the infection. We show that IL-22 but not IL-17 provides protection from fatal liver tissue damage during a primary P. chabaudi infection.

Materials and Methods

Mice, parasites, and infection

All experimental animals were kept in pathogen-free animal facilities at the MRC National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR, London, UK) in accordance with local guidelines. Male and female C57BL/6 mice, Il17aCre+/+R26ReYFP mice and Il17aCre+/−R26ReYFP mice (Hirota et al., 2011), il17A−/− mice, kindly provided by Dr. A. Smith (Schmidt and Bradfield, 1996), and il22−/− mice (Kreymborg et al., 2007). All knockout (KO) mice were bred in the NIMR specific pathogen-free unit on the C57BL/6 background and the genotype of each of the mice was always verified before use. All mice were used at 6–8 weeks of age.

The Il17aCre+/+R26ReYFP mice and Il17aCre+/−R26ReYFP mice allow permanent tracing of cells with activation of the locus encoding the signature cytokine IL-17A. Briefly, the Cre recombinase activity is visualized by eYFP expression from the Rosa26 promoter. Therefore, eYFP is expressed in all cells that had activated IL-17A and their progeny, thus allowing the identification of cells that have switched on the IL-17 program as well as alternative effector programs that might have been activated. In the Il17aCre+/+R26ReYFP mice (Cre/Cre homozygous), the IL-17A gene is replaced by the Cre recombinase, whereas in Il17aCre+/−R26ReYFP mice (Cre ± heterozygous), IL-17A is not replaced by the Cre recombinase, allowing tracking of IL-17AeYFP+ expression in vivo.

Mice were infected with 1 × 105 P. chabaudi (AS) infected red blood cells (iRBC) and parasitemia, weight loss, and body temperature were monitored as previously described (Li et al., 2003). All animal experiments were conducted under a British Home Office license and according to international guidelines and UK Home Office regulations, after approval from the NIMR Ethical Review Panel.

Cell lines and peptides

Monoclonal antibodies specific for IL-17A [Uyttenhove and Van Snick, 2006; clone MM17F3, mouse Immunoglobulin G (IgG) 1] and IL-22 (Ma et al., 2008; Dumoutier et al., 2009; AM 22.1, mouse IgG2a) were used for in vivo neutralization and for flow cytometry. The hybridomas were cultured in Iscove’s medium (IMDM, Sigma, UK) with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS), 1 mM l-Glutamine, 10 mM Hepes, 5 × 10−5 M β-Mercaptoethanol, 100 μg/ml penicillin, 100 U/ml streptomycin, and 1 mM Sodium pyruvate (complete IMDM), and purified from in vitro cultures by Protein A (Bio-Rad) affinity chromatography (Endotoxin <10 IU). 0.5 mg/mouse of neutralizing antibody was given intraperitoneally (i.p.), twice weekly or every other day for anti-IL-17A and anti-IL-22 treatment, respectively.

Antibodies and flow cytometric analysis

Spleen cells from naïve or P. chabaudi-infected mice were mashed through a 70-μm sieve (Falcon) into complete IMDM to create a single-cell suspension. Erythrocytes were lysed with red blood cell lysis buffer (Sigma), and the cell pellet was washed and resuspended in FACS buffer [1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin, 5 mM EDTA, and 0.01% sodium azide in PBS]. Mononuclear liver cells were isolated as described in Tupin and Kronenberg (2006). Briefly, the liver is perfused with PBS to remove external blood and placed into 5 ml IMDM + 2% FCS + 10 mM HEPES. The whole liver is mashed through a 70-μm filter to give a single-cell suspension, and centrifuged at RT for 7 min at 500 g. The cell pellet is washed with 10 ml IMDM + 2% FCS + 10 mM HEPES and centrifuged as before. The cell pellet is resuspended in 25 ml of 37.5% Percoll + 100 U/ml Heparin in IMDM (at RT), and centrifuged at RT for 12 min at 700 g with no brake. The mononuclear cells form a tight pellet at the base of the tube. The supernatant is removed and the cell pellet resuspended in IMDM, and centrifuged at 4°C for 5 min at 300 g.

Antibodies used were CD8α Biotin, CD4 Pacific Blue, TCRγδ PE, NK1.1 PE, IL-17A Alexa Fluor 647, and IFN-γ FITC (eBiosciences, Insight Biotechnology, London, UK). IL-22 was detected using the polyclonal PE anti-mouse IL-22 antibody (BioLegend). Isotype controls were included in each staining. Before addition of specific fluorescently labeled antibodies, 2 × 106 cells were pre-incubated at room temperature for 10 min with anti-Fc receptor antibody (Unkeless, 1979) to prevent non-specific binding via the FcR. All other preparations with antibodies for extracellular staining were incubated for 20 min on ice. For intracellular staining, cells were stimulated with 50 ng/ml PMA (Sigma), 500 ng/ml Ionomycin (Sigma) for 2 h at 37°C, 7% CO2. Ten micrograms per milliliter Brefeldin A (Sigma) was added for the last 2 h of culture. In Figure 3, cells were restimulated with 500 ng/ml Phorbol dibutyrate (PdBU) and 500 ng/ml ionomycin in the presence of 1 μg/ml Brefeldin A (Sigma) for 2 h. Cells were then fixed with 3.65% formaldehyde solution from Sigma and permeabilized with 0.1% NP40 before intracellular staining. Data were acquired on a CyAn ADP analyzer (Beckman Coulter Cyan ADP) using Summit software, and the proportions of cells were determined using FlowJo software (Treestar).

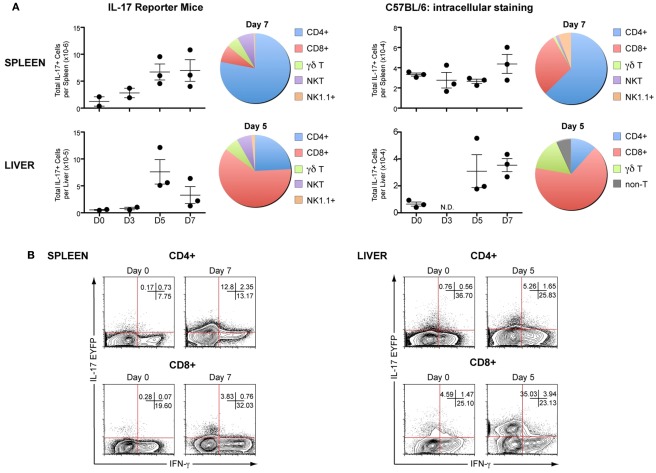

Figure 3.

In vivo kinetics of IL-17A in spleen and liver of mice infected with P. chabaudi. IL-17-fate reporter (Il17aCreR26ReYFP) and C57BL/6 mice were infected with 105P. chabaudi and sacrificed at days 3, 5, and 7 post-infection. (A) Total numbers of IL-17AeYFP- and IL-17+-cells (detected by intracellular staining) in splenocytes and hepatocytes from naïve and infected IL-17-fate reporter mice (left panel) and C57BL/6 mice (right panel), respectively. The numbers represent the median and range of three mice. The fraction of CD4+, CD8+, γδ+, NK T cells, and NK cells contributing to IL-17A+ production in spleen and liver at day 7 and 5, respectively. (B) Representative flow cytometry plots of IL-17AeYFP versus IFN-γ expression in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, in liver cells, and splenocytes of naïve and day 5 and 7 infected mice. Numbers in quadrants refer to the percentages of cells in each quadrant. Data are representative of two experiments and are obtained in groups of three mice per time points (mean ± SEM).

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from 5 × 106 cells splenocytes or mononuclear cells from liver from uninfected and P. chabaudi-infected mice. Cells were resuspended in TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, after which 5 μg of total RNA were reverse transcribed using Superscript II RT (Life Technologies) at 42°C for 50 min, 70°C 15 min, in the presence of 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.3, 75 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT (Dithiothreitol), 0.5 mM dNTPs, 8 U RNasin, and 5 μM Oligo(dT)16. The cDNA was finally treated with 2.5 U RNAse H at 37°C for 20 min to remove any RNA residues.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Real-time quantitative PCR reactions were performed using SYBR Green PCR Core Reagents (ABgene). PCR amplifications were performed in duplicate wells in a total volume of 25 μl, containing 1 μl cDNA sample, 2 μM of each primer, 12.5 ml of Absolute QPCR SYBR green mix, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The resultant PCR products were measured and elaborated using an Applied Biosystems GenApm 7000 Sequence detection system (ABI Prism 7000; primers sequences, Table A1 in Appendix).

The PCR cycling protocol entailed 1 cycle at 50°C for 2 min and then 95°C for 15 min, to activate the DNA polymerase, followed by 40 cycles each consisting of 95°C for 15 s and 1 min at 60°C.

Analysis of the relative changes (arbitrary units) in gene expression required calculations based on the cycle threshold (CT) following the 2−ΔΔCT method (Pfaffl, 2001). ΔΔCT was calculated as the difference between the ΔCT values of the samples and the ΔCT values of a calibrator sample; 2−ΔΔCT was the relative mRNA unit representing the fold induction over control.

All quantifications were normalized to the level of Ubiquitin gene expression (housekeeping gene). Test samples were expressed as the fold increase of gene expression compared with expression in normal uninfected mice (mean of expression from three uninfected mice).

Plasma cytokine measurements

Cytokine production was measured in the supernatant with a bead-based (Multiplex) cytokine detection assay (eBioscience, UK). The samples were processed using the manufacturers protocol and acquired on FACS Calibur and analyzed using FlowCytomix™ Pro 2.4 software (eBiosciences).

Alanine transaminase quantitation in plasma

Mouse blood samples were collected and centrifuged for collection of plasma. Plasma samples from naïve and infected samples were diluted 1:10 or 1:100, respectively in PBS. Levels of alanine transaminases (ALT) in serum were quantified using a Cobas C111 chemistry analyzer (Roche).

Statistical analysis

Data are shown as means and SEM, and significant differences were analyzed using a non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test, p < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant difference.

Results

TH17 cells signature cytokines, IL-17A and IL-17F, mRNA transcripts are increased in the liver during a primary P. chabaudi infection

Plasmodium chabaudi blood-stage infections in mice are characterized by an acute inflammatory response with the induction of TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, and IFN-γ within the first 10–15 days of infection, all of which could contribute to the pathology accompanying this stage of the infection. In order to determine whether TH17 cells could play any role in controlling parasitemia and/or immunopathology we first analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) whether mRNAs for the TH17 signature cytokines IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 were induced in lymphocytes and mononuclear cells in spleen and liver, respectively, during a P. chabaudi infection (Figure 1A).

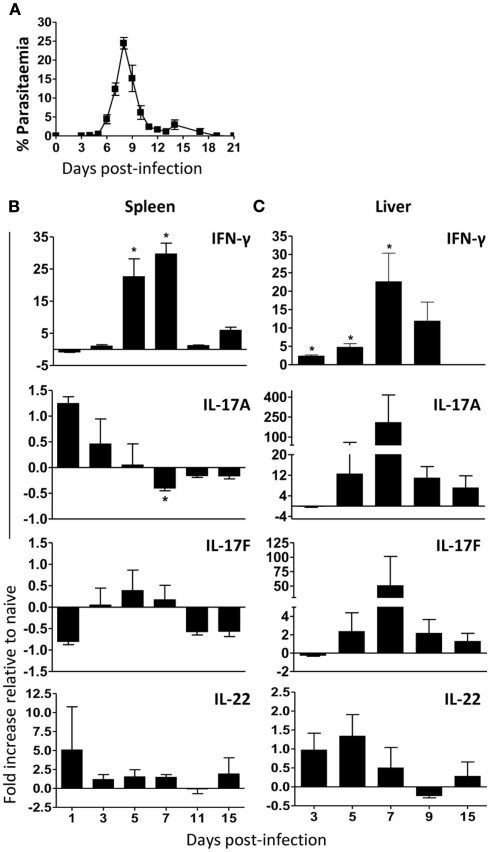

Figure 1.

TH17 cells signature cytokines, IL-17A and IL-17F, mRNA transcripts are increased in the liver during a primary P. chabaudi infection. C57BL/6 mice were infected with 105 P. chabaudi and sacrificed post-infection at the time points indicated. Spleen and liver mononuclear cells were harvested from naïve and infected mice and analyzed by real-time PCR. (A) Representative course of infection in C57BL/6 mice. IFN-γ, IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 mRNA levels were determined in naïve and infected splenocytes (B) and liver mononuclear cells (C). Data are normalized to Ubiquitin expression. Test samples were expressed as the fold increase of gene expression compared with expression in normal uninfected mice (mean of expression from three uninfected mice were set at one) versus infected mice samples. Negative values represent levels of gene expression lower than those measured in naïve mice. Data are representative of two experiments and are obtained in groups of five mice per time points (mean ± SEM).

In direct contrast to the well-described increase in IFN-γ transcription in spleens (Stevenson et al., 1990; von der Weid and Langhorne, 1993) during the first 7–11 days of infection (Figure 1B), IL-17A mRNA levels were elevated within 1–2 days after infection but then markedly decreased over time (Figure 1B), to the levels found in naive mice, particularly at peak parasitemia (days 7–11), suggesting that the spleen environment during P. chabaudi infection, rich in IFN-γ mRNA expression, may negatively regulate IL-17 expression. However, IL-17F mRNA levels were not substantially altered by the infection (±0.5-fold change relative to naïve controls).

A markedly different response of IL-17A and IL-17F was observed in the liver, which also enlarges during malaria (Dockrell et al., 1980), coincident with an increase in IFN-γ expression, large, and transient increases in IL-17A and IL-17F mRNA transcripts compared with naïve controls (200- and 50-fold, respectively) were detected at day 7 post-infection (Figure 1C). Similarly to the results observed in the spleen (Figure 1B), IL-22 mRNA was detectable in the liver early in the infection, but at low levels (an approximately 1.4-fold increase compared with naïve controls, Figure 1C).

Therefore, P. chabaudi infection induced a down-regulation of IL-17 expression in the spleen, whereas, in the liver, infection induced increased IL-17 mRNA expression, indicating a potential role for IL-17 during a blood-stage P. chabaudi infection.

In vivo kinetics of IL-17A and IL-22 expression in the spleen and liver of mice infected with P. chabaudi

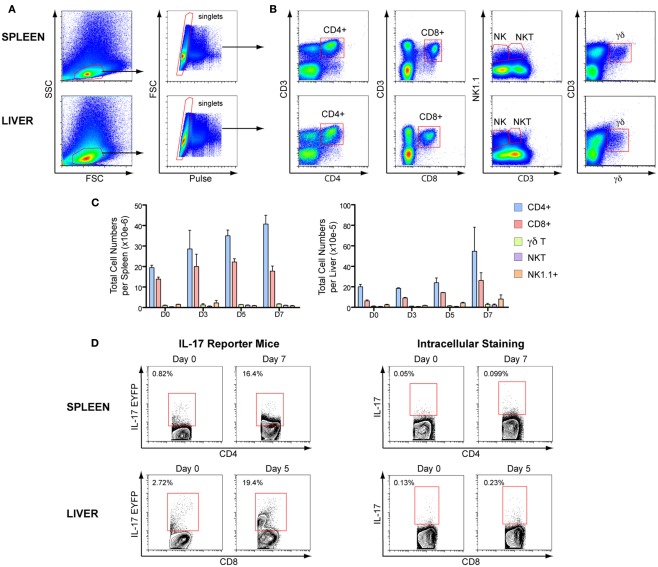

To assess whether IL-17 protein levels were consistent with the mRNA transcripts, we evaluated the kinetics of IL-17AeYFP expression in several T cell populations in IL-17-fate reporter mice (Il17aCreR26ReYFP) infected with P. chabaudi (representative flow cytometry plots and gating strategies in Figure 2). Since the EYFP IL-17 reporter mice report any cell that has ever expressed IL-17A, it may not represent the cytokine status of the cells at the time of sampling. Therefore, we also evaluated IL-17A expression by intracellular staining in wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice infected with P. chabaudi for the same times post-infection (Figures 2 and 3). Although IL-17A transcripts were low in splenocytes throughout the course of infection, lymphocytes and mononuclear cells expressing EYFP were readily detectable and their numbers significantly increased over time in both spleen and liver (Figure 3A). By contrast, an increase in IL-17A expression by intracellular staining was only detected in liver mononuclear cells (Figure 3A), correlating with the increased IL-17 mRNA detected in the liver.

Figure 2.

Gating strategies for IL-17 producing cells. IL-17-fate reporter (Il17aCreR26ReYFP) and C57BL/6 mice were infected with 105 P. chabaudi and sacrificed at days 3, 5, and 7 post-infection. (A) Representative flow cytometry plots of live cells gating in spleen and liver mononuclear cells. (B) Gating strategy for CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, NK+, and γδ+ T cells, and CD3−NK+ cells. (C) Total cell numbers of the several T cells populations in C57BL/6 splenocytes and liver mononuclear cells during the first 7 days of P. chabaudi infection. (D) Representative flow cytometry plots of IL-17EYFP or IL-17A+ cells in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of infected splenocytes and liver mononuclear cells of reporter and C57BL/6 mice, respectively.

As the EYFP fate reporter marks cells that are no longer necessarily actively producing IL-17 at the times measured, there were many more IL-17+ cells in the infected reporter mice than in the C57BL/6 mice. However in both infected IL-17 reporter mice and WT C57Bl/6 mice, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were the predominant sources of this cytokine in spleen and liver, respectively (shown for days 5 and 7, Figure 3A).

Although both IL-17A+ and IFN-γ+ T cells were increased in livers of the fate reporter mice following infection, very few IL-17+IFN-γ+ double-producers were detected (Figure 3B). Therefore, although a different experimental system previously described a potential for TH17 cells to partially lose IL-17 expression and up-regulate IFN-γ (Kurschus et al., 2010), this does not appear to be the case in this malaria infection and it is thus very unlikely that any of the IFN-γ produced during malaria infection are derived from cells previously producing IL-17.

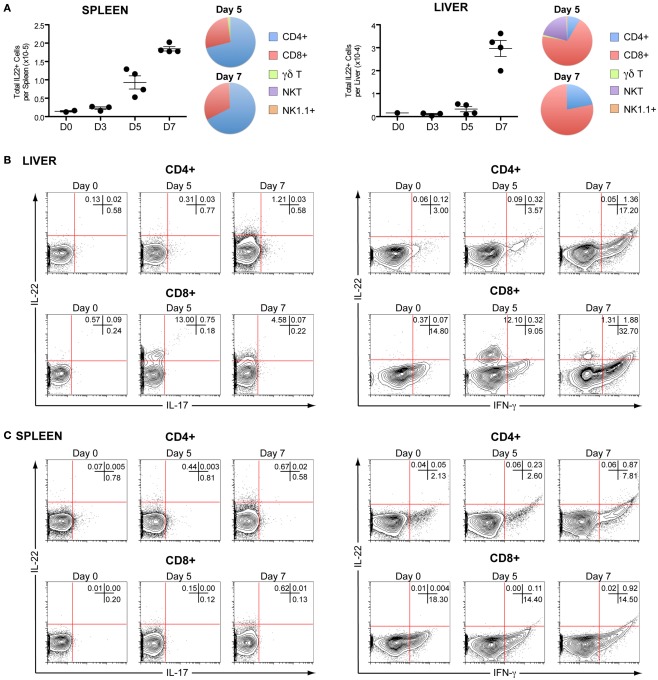

Although we could not detect high levels of IL-22 mRNA during P. chabaudi infection in either spleen or liver, they were elevated compared with controls. As IL-22 has been reported to play a critical role during acute liver inflammation (Radaeva et al., 2004; Zenewicz et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2011), we therefore investigated IL-22 production by intracellular staining of lymphocyte populations in the liver and spleen of infected C57BL/6 mice and found increased numbers of IL-22-producing cells in both organs (Figure 4A). Similar to IL-17A production, the predominant cells producing IL-22 were CD4+ T cells in the spleen and CD8+ T cells in the liver (Figures 4B,C). In agreement with a previous report showing that NKT cells are important producers of the hepato-protective cytokine IL-22 in mouse model of hepatitis (Wahl et al., 2009), we observed that NKT cells were also significant contributors to the production of IL-22 at day 5 of the P. chabaudi infection (Figure 4A), although they represented only a very small fraction of cells present in the liver (Figure 2C). However, no IL-22+/IL-17+ or IL-22+/IFN-γ+ double-producers could be detected in either the spleen or liver (Figure 4B,C), suggesting that either distinct kinetics and/or different sub-populations of CD8+ T cells produce these cytokines.

Figure 4.

In vivo kinetics of IL-22 in spleen and liver of mice infected with P. chabaudi. C57BL/6 mice were infected with 105P. chabaudi and sacrificed at days 3, 5, and 7 post-infection. (A) Total numbers of IL-22+ cells in splenocytes and hepatocytes from naïve and infected C57BL/6 mice. The fraction of CD4+, CD8+, γδ+, NK T cells, and NK cells contributing to IL-22 production in infected splenocytes and mononuclear liver cells on days 5 and 7 post-infection. The numbers represent the median and range of four mice. Representative flow cytometry plots of IL-22 versus IL-17A (left panels) and IL-22 versus IFN-γ (right panels) and expression in CD4+, and CD8+ T in naïve, day 5 and 7 infected liver mononuclear cells (B) and splenocytes (C). Numbers in quadrants refer to the percentages of cells in each quadrant. Data are representative of two experiments and are from groups of four mice per time point.

Lack of IL-22 but not IL-17A results in increased mortality and liver damage during a P. chabaudi infection

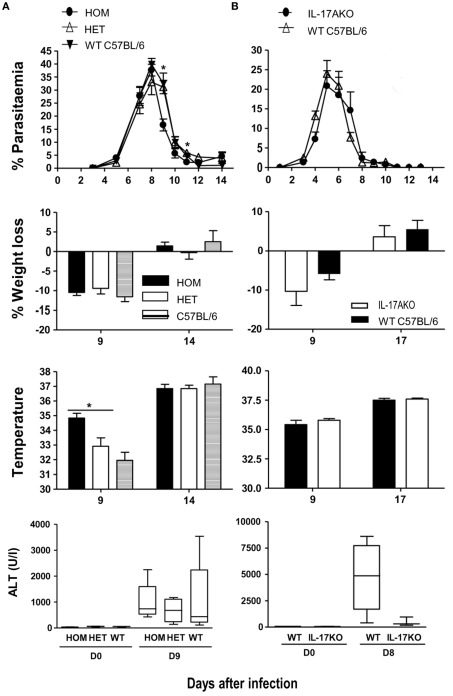

Despite the increased production of IL-17A and the greater number of T cells in the liver producing IL-17A during a P. chabaudi infection, lack of IL-17A in either the Il17aCre+/+R26ReYFP mice, or conventional Il17A−/− mice had little or no effect on parasitemia, weight loss, or hypothermia, when compared with infected control Il17aCre+/−R26ReYFP mice which express IL-17, or control C57BL/6 mice (Figure 5). Similarly, administration of neutralizing anti-IL-17A antibodies in control C57BL/6 mice did not alter the course of the infection or any of the pathological parameters tested compared with mice receiving isotype control antibodies (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Parasitemia and pathology in IL-17-fate reporter and IL-17 KO mice. (A) Il17aCre+/+R26ReYFP and conventional (B) Il17A−/− mice were infected with 105 P. chabaudi, five mice per group. The heterozygous reporter mice in (A) also act as a control for the homozygous mice as the IL-17 gene is not deleted in these mice. WT C57BL/6 mice were used as controls in (A,B). Weight loss and hypothermia (pathology) were monitored daily. Parasitemias are presented as percentage of parasitized RBC, and the error bars represents the SEMs. Tail blood was collected to measure ALT variation during the infection, using a colorimetric end-point method (adapted from Reitman and Frankel, 1957). Briefly, 20 μl of test serum was added to 100 μl of the ALT substrate and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Hundred microliters of 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine was then added and incubated a further 20 min at RT. One milliliter of 0.4 M NaOH was added to stop the reaction and the OD determined at 490 nm. Water was used as blank. OD values were then converted into the equivalent enzyme units (U/ml) using a standard curve derived from known concentrations of a pyruvate standard. The standard curve for ALT was performed using pyruvate standards. Data are means and SEM of five mice and representative of two experiments. Significant differences are shown using a Mann–Whitney U-test of five mice [*significant P-value (0.01–0.05)].

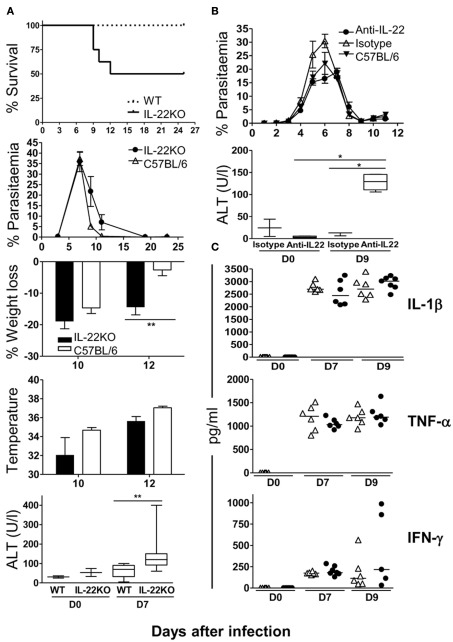

In stark contrast, lack of IL-22 in IL-22 KO mice resulted in 50% mortality within 12 days after injection of 105 P. chabaudi iRBC with significantly greater weight loss at the peak of infection (Figure 6A). Although IL-22 KO mice had some difficulty in controlling the infection with delayed clearance and increased loss of body weight compared to controls, fulminant or increased parasitemia or extreme loss of body temperature was not responsible for mortality as parasitemias and temperature were similar in IL-22 KO (irrespective of whether or not mice died) and WT control mice (Figure 6A). There was no mortality in mice given with anti-IL-22 antibodies, and similarly to the IL-22 KO mice there was no difference in weight loss.

Figure 6.

Lack of IL-22 but not IL-17A results in increased mortality and liver damage during a P. chabaudi infection. C57BL/6 mice were treated with either 0.5 mg of anti-IL-22 antibody or an isotype control, every other day, from day 0 to 14 post-infection. IL-22 KO mice and anti-IL-22 treated C57BL/6 mice were infected at day 0 with 105 P. chabaudi, five mice per group. Weight loss and hypothermia were monitored daily. Parasitemias are presented as percentage of parasitized RBC, and the error bars represents the SEMs. Tail blood was collected to measure ALT variation during the infection, using a Cobas C111 chemistry analyzer. Data are means and SEM of five mice and representative of two experiments. Significant differences are shown using a Mann–Whitney U-test of five mice [*significant P-value (0.01–0.05), **very significant P-value (0.001–0.01)]. (A) Survival, parasitemia, pathology, and liver damage in IL-22 KO and WT mice. (B) Parasitemia and ALT levels in anti-IL-22 treated or control mice. (C) Plasma IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ levels were determined by ELISA in naïve and day 7 and 9 infected IL-22 KO mice and WT mice. The numbers and the median are represented of four mice.

Experimental malaria infections in mice, including P. chabaudi infections have been shown to cause liver pathology (Mota et al., 2000; Kochar et al., 2003). As there was an increase in CD8+ and NKT cells producing IL-22 and IL-17 infiltrating the liver during the acute P. chabaudi infection (Figures 3 and 4), it was possible that in the absence of IL-22 there is an increase in liver damage. We therefore measured the amount of ALT in plasma of P. chabaudi-infected IL-17- (Figure 5) and IL-22-deficient mice (Figures 6A,B), as an indicator of hepatocyte dysfunction (Astegiano et al., 2004).

There was a trend towards lower plasma ALT in Il17aCre+/−R26ReYFP and IL-17 KO mice compared with their WT controls during the acute phase of the P. chabaudi infection, however these differences were not significant, suggesting that IL-17 does not contribute in a major way to liver pathology or to its control during P. chabaudi infection (Figure 5).

Plasmodium chabaudi-infected IL-22 KO mice, in contrast, displayed a significant increase in ALT in the plasma in the acute infection (Figure 6A). Similarly, although there was no increase in mortality, mice given neutralizing anti-IL-22 Abs also exhibited significantly greater ALT levels compared with isotype control-treated and untreated mice (Figure 6B).

We have previously shown that inactivation of regulatory cytokines such as IL-10 results in increased pathology with a proportion of mice suffering a lethal infection, caused by increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IFN-γ (Li et al., 1999). However, unlike an infection in IL-10 KO mice there was no difference in the amounts of TNF-α, IFN-γ, or IL-1β in infected IL-22 KO mice during the first 10 days of infection compared with WT mice suggesting that an enhanced inflammatory response was not the most likely cause of the mortality observed (Figure 6C).

Together these data support the idea that IL-22 may be important in controlling liver damage as a result of a P. chabaudi infection, and can protect mice from its potentially lethal effects.

Discussion

In the present study, we have demonstrated that IL-17- and IL-22-producing CD8+ T cells are present and increase in number in the liver of C57BL/6 mice during an acute blood-stage infection with P. chabaudi. Importantly, IL-22 produced during a primary infection with the blood-stages of P. chabaudi plays vital role in controlling liver damage during a primary infection, since in its absence there is an increase in plasma ALT, and more than 50% of mice die during the first 12 days of infection. By contrast, although IL-17A is also produced early during a P. chabaudi infection in the liver, largely by CD8+ T cells, IL-17A-deficient mice show little difference in liver damage, parasitemia, or any other indicators of pathology compared with infected control mice. Despite previous demonstrations of plasticity of TH17 cells, which can develop into disease-causing TH1 cells in autoimmune experimental allergic encephalitis (EAE) and Type I Diabetes (Bending et al., 2009; Kurschus et al., 2010), we could find no evidence in this malaria infection that IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells had arisen from previous TH17 cells.

There is very little information on IL-22 in malaria, and no direct evidence until now that IL-22 itself had any protective effect in this infection. A large case–control study of severe malaria in a West African population identified several weak associations with individual single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the Il22 gene, and defined two IL-22 haplotypes associated with resistance (IL22 − 1394A and IL22 + 708T alleles) or susceptibility (IL22 − 1394G and the IL22 + 708C alleles; Koch et al., 2005). No data are as yet available of the effects of these polymorphisms on expression or regulation of IL-22. A recent study employing macaque models of co-infection with malaria and SHIV has demonstrated that the expansion of TH17/TH22 cells attenuated malaria and avoided fatal-virus-associated malaria by inhibiting TH1 responses (Ryan-Payseur et al., 2011). Together these data indeed support our findings that IL-22 induction may be important during a malaria infection.

IL-22 has been shown to have several important roles. Its receptor is not present on hematopoietic cells but on tissues, particularly epithelial cells such as gut epithelial cells, keratinocytes, and hepatocytes (Wolk and Sabat, 2006), and it has an important cyto-protective function contributing to tissue and cell repair (Sonnenberg et al., 2011). Given our findings of increased liver damage in P. chabaudi infection in IL-22 KO mice, its ability to protect hepatocytes during liver inflammation (Radaeva et al., 2004; Xing et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2011) is of particular relevance.

IL-22 can be produced by many different types of lymphocytes of the innate and adaptive immune system, including CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells (Zheng et al., 2007; Nograles et al., 2009), innate lymphoid cells (Taube et al., 2011), the NK-22 subset of natural killer cells (Zenewicz et al., 2008; Cella et al., 2009), γδ+ T cells (Martin et al., 2009; Simonian et al., 2010), and CD11c+ DCs (Zheng et al., 2007). Surprisingly in our study, CD8+ T cells were a significant source of both IL-22 and IL-17 among liver mononuclear cells of infected mice. The CD8+ T cells in this P. chabaudi infection producing IL-17 or IL-22 are reminiscent of a recently described human population of CD8+ T cells (Billerbeck et al., 2010). These TC17 cells are defined by the expression of CD161 and a pattern of molecules consistent with TH17 differentiation including IL-17 and IL-22 cytokines. In addition, TC17 cells are markedly enriched in tissue samples, such as liver, and maybe associated with protection against human Hepatitis C pathology (Billerbeck et al., 2010), in line with the known hepato-protective function of IL-22 (Radaeva et al., 2004; Xing et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2011). In our mouse model of malaria, however, we did not detect any IL-17/IL-22 double-producing cells. In this respect the CD8+ T cells secreting either IL-17 or IL-22 may be more similar to the IL-22-producing CD4+ T cells, which have been shown to be distinct from TH17, TH1, and TH2 cells (Trifari et al., 2009).

Induction of IL-22 in vitro depends on IL-6, IL-23, and IL-1β (Ghoreschi et al., 2010) but unlike IL-17A, is inhibited by TGF-β (Rutz et al., 2011), although that has not been formally shown for these IL-22-producing CD8+ T cells. IL-6, TGF-β, and IL-1-β are all produced during acute malaria in mice (Artavanis-Tsakonas et al., 2003; Li et al., 2003) and humans (Walther et al., 2006), and by myeloid cells such as dendritic cells and inflammatory monocytes (Voisine et al., 2010), which have interacted with or phagocytosed hemozoin, parasite material, or iRBC (reviewed in Shio et al., 2010). Furthermore, IL-6 and TGF-β are abundant in damaged or injured livers (Streetz et al., 2003; Knight et al., 2005), and as liver pathology has been documented during blood-stage malaria infections (Kochar et al., 2003; Devarbhavi et al., 2005; Whitten et al., 2011), it seems likely that the environment in the liver could be conducive to the differentiation of IL-17- and/or IL-22-producing CD8+ T cells. Therefore, IL-22-producing CD8 T cells in the liver may include both; infiltrating cells as well as liver-differentiated IL-17 and IL-22-producing CD8 T cells, although this need to be determined.

The mechanism of the liver damage that is protected by IL-22 in this infection is not known. In P. berghei infections of mice, different cells and molecules have been implicated, including NKT, MyD88, IL-12, IFN-γ, and free Heme (Adachi et al., 2001; Seixas et al., 2009; Findlay et al., 2010), and one study has shown that liver damage occurs independently of CD8+ T cells (Haque et al., 2011). Free heme has also been implicated in liver damage in P. chabaudi infections in a susceptible mouse strain (Seixas et al., 2009). Whether or not there is an additional role for other pro-inflammatory cytokines in this remains to be determined.

The signaling pathway by which IL-17 and IL-22 production are induced in CD8+ T cells in this P. chabaudi infection has still to be elucidated. As we only evaluated mice lacking IL-22, it is unclear whether, similarly to CD4+ T cells (Veldhoen et al., 2008), AHR and Notch signaling are required for IL-22 expression in the liver CD8+ T cells in this malaria infection, and further studies are required to delineate whether this pathway is a key mechanism involved in protection from liver damage during a primary P. chabaudi infection via the induction of IL-22-producing CD8+ T cells.

In conclusion, we propose that the IL-22+ CD8+ T cells, which appear in the liver in this P. chabaudi infection prevent or ameliorate potential toxic damage to liver cells. The relevance of these findings to human severe malaria remains to be established. As hepatic dysfunction can be a significant feature of human malaria it would be important to relate our findings to the IL-22 gene polymorphisms found to be associated with resistance or susceptibility to P. falciparum malaria, as well as to the magnitude of IL-22 response in severe and mild disease.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council, United Kingdom (MRC file reference: U117584248), and is part of the EviMalar European Network of Excellence supported by the Framework 7 programme of the European Union. BM was in receipt of a MRC PhD Studentship.

Appendix

Table A1.

Primers used for Real-time quantitative PCR reactions.

| Forward sequence | Reverse sequence | |

|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin | TGGCTATTAATTATTCGGTCTGCAT | GCAAGTGGCTAGAGTGCAGAGTAA |

| IL-17A | TCCAGAAGGCCCTCAGACTA | CAGGATCTCTTGCTGGATG |

| IL-17F | CTGAGGCCCAGTGCAGACA | GCTGAATGGCGACGGAGTT |

| IL-22 | TCCGAGGAGTCAGTGCTAAA | AGAACTGCTTCCAGGGTGAA |

| IFN-• | GGATGCATTCATGAGTATTG | CTTTTCCGCTTCCTGAGG |

Abbreviations

AHR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; ALT, alanine transaminase; IMDM, Iscove’s medium; i.p., intraperitoneally; iRBC, infected red blood cells; KO, knockout; P., Plasmodium; qRT-PCR, quantitative real-time PCR; WT, wild-type.

References

- Adachi K., Tsutsui H., Kashiwamura S., Seki E., Nakano H., Takeuchi O., Takeda K., Okumura K., Van Kaer L., Okamura H., Akira S., Nakanishi K. (2001). Plasmodium berghei infection in mice induces liver injury by an IL-12- and toll-like receptor/myeloid differentiation factor 88-dependent mechanism. J. Immunol. 167, 5928–5934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal S., Ghilardi N., Xie M. H., De Sauvage F. J., Gurney A. L. (2003). Interleukin-23 promotes a distinct CD4 T cell activation state characterized by the production of interleukin-17. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 1910–1914 10.1074/jbc.M306291200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam M. S., Maekawa Y., Kitamura A., Tanigaki K., Yoshimoto T., Kishihara K., Yasutomo K. (2010). Notch signaling drives IL-22 secretion in CD4+ T cells by stimulating the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 5943–5948 10.1073/pnas.0911755107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annunziato F., Cosmi L., Santarlasci V., Maggi L., Liotta F., Mazzinghi B., Parente E., Fili L., Ferri S., Frosali F., Giudici F., Romagnani P., Parronchi P., Tonelli F., Maggi E., Romagnani S. (2007). Phenotypic and functional features of human Th17 cells. J. Exp. Med. 204, 1849–1861 10.1084/jem.20070663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artavanis-Tsakonas K., Tongren J. E., Riley E. M. (2003). The war between the malaria parasite and the immune system: immunity, immunoregulation and immunopathology. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 133, 145–152 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02174.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astegiano M., Sapone N., Demarchi B., Rossetti S., Bonardi R., Rizzetto M. (2004). Laboratory evaluation of the patient with liver disease. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 8, 3–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aujla S. J., Chan Y. R., Zheng M., Fei M., Askew D. J., Pociask D. A., Reinhart T. A., Mcallister F., Edeal J., Gaus K., Husain S., Kreindler J. L., Dubin P. J., Pilewski J. M., Myerburg M. M., Mason C. A., Iwakura Y., Kolls J. K. (2008). IL-22 mediates mucosal host defense against Gram-negative bacterial pneumonia. Nat. Med. 14, 275–281 10.1038/nm1710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasthi A., Kuchroo V. K. (2009). Th17 cells: from precursors to players in inflammation and infection. Int. Immunol. 21, 489–498 10.1093/intimm/dxp021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bending D., De La Pena H., Veldhoen M., Phillips J. M., Uyttenhove C., Stockinger B., Cooke A. (2009). Highly purified Th17 cells from BDC2.5NOD mice convert into Th1-like cells in NOD/SCID recipient mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 565–572 10.1172/JCI37865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billerbeck E., Kang Y. H., Walker L., Lockstone H., Grafmueller S., Fleming V., Flint J., Willberg C. B., Bengsch B., Seigel B., Ramamurthy N., Zitzmann N., Barnes E. J., Thevanayagam J., Bhagwanani A., Leslie A., Oo Y. H., Kollnberger S., Bowness P., Drognitz O., Adams D. H., Blum H. E., Thimme R., Klenerman P. (2010). Analysis of CD161 expression on human CD8+ T cells defines a distinct functional subset with tissue-homing properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 3006–3011 10.1073/pnas.0914839107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella M., Fuchs A., Vermi W., Facchetti F., Otero K., Lennerz J. K., Doherty J. M., Mills J. C., Colonna M. (2009). A human natural killer cell subset provides an innate source of IL-22 for mucosal immunity. Nature 457, 722–725 10.1038/nature07537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devarbhavi H., Alvares J. F., Kumar K. S. (2005). Severe falciparum malaria simulating fulminant hepatic failure. Mayo Clin. Proc. 80, 355–358 10.4065/80.3.355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dockrell H. M., De Souza J. B., Playfair J. H. (1980). The role of the liver in immunity to blood-stage murine malaria. Immunology 41, 421–430 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumoutier L., De Meester C., Tavernier J., Renauld J. C. (2009). New activation modus of STAT3: a tyrosine-less region of the interleukin-22 receptor recruits STAT3 by interacting with its coiled-coil domain. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 26377–26384 10.1074/jbc.M109.007955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findlay E. G., Greig R., Stumhofer J. S., Hafalla J. C., De Souza J. B., Saris C. J., Hunter C. A., Riley E. M., Couper K. N. (2010). Essential role for IL-27 receptor signaling in prevention of Th1-mediated immunopathology during malaria infection. J. Immunol. 185, 2482–2492 10.4049/jimmunol.0904019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghoreschi K., Laurence A., Yang X. P., Tato C. M., Mcgeachy M. J., Konkel J. E., Ramos H. L., Wei L., Davidson T. S., Bouladoux N., Grainger J. R., Chen Q., Kanno Y., Watford W. T., Sun H. W., Eberl G., Shevach E. M., Belkaid Y., Cua D. J., Chen W., O’Shea J. J. (2010). Generation of pathogenic T(H)17 cells in the absence of TGF-beta signalling. Nature 467, 967–971 10.1038/nature09447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto M., Murakawa M., Kadoshima-Yamaoka K., Tanaka Y., Nagahira K., Fukuda Y., Nishimura T. (2009). Murine NKT cells produce Th17 cytokine interleukin-22. Cell. Immunol. 254, 81–84 10.1016/j.cellimm.2008.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque A., Best S. E., Amante F. H., Ammerdorffer A., De Labastida F., Pereira T., Ramm G. A., Engwerda C. R. (2011). High parasite burdens cause liver damage in mice following Plasmodium berghei ANKA infection independently of CD8(+) T cell-mediated immune pathology. Infect. Immun. 79, 1882–1888 10.1128/IAI.01210-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota K., Duarte J. H., Veldhoen M., Hornsby E., Li Y., Cua D. J., Ahlfors H., Wilhelm C., Tolaini M., Menzel U., Garefalaki A., Potocnik A. J., Stockinger B. (2011). Fate mapping of IL-17-producing T cells in inflammatory responses. Nat. Immunol. 12, 255–263 10.1038/ni.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov I. I., Mckenzie B. S., Zhou L., Tadokoro C. E., Lepelley A., Lafaille J. J., Cua D. J., Littman D. R. (2006). The orphan nuclear receptor RORgamma t directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell 126, 1121–1133 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly M. N., Kolls J. K., Happel K., Schwartzman J. D., Schwarzenberger P., Combe C., Moretto M., Khan I. A. (2005). Interleukin-17/interleukin-17 receptor-mediated signaling is important for generation of an optimal polymorphonuclear response against Toxoplasma gondii infection. Infect. Immun. 73, 617–621 10.1128/IAI.73.1.592-598.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight B., Matthews V. B., Akhurst B., Croager E. J., Klinken E., Abraham L. J., Olynyk J. K., Yeoh G. (2005). Liver inflammation and cytokine production, but not acute phase protein synthesis, accompany the adult liver progenitor (oval) cell response to chronic liver injury. Immunol. Cell Biol. 83, 364–374 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2005.01346.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch O., Rockett K., Jallow M., Pinder M., Sisay-Joof F., Kwiatkowski D. (2005). Investigation of malaria susceptibility determinants in the IFNG/IL26/IL22 genomic region. Genes Immun. 6, 312–318 10.1038/sj.gene.6364214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochar D. K., Agarwal P., Kochar S. K., Jain R., Rawat N., Pokharna R. K., Kachhawa S., Srivastava T. (2003). Hepatocyte dysfunction and hepatic encephalopathy in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. QJM 96, 505–512 10.1093/qjmed/hcg091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiyama Y., Nakae S., Matsuki T., Nambu A., Ishigame H., Kakuta S., Sudo K., Iwakura Y. (2006). IL-17 plays an important role in the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 177, 566–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreymborg K., Etzensperger R., Dumoutier L., Haak S., Rebollo A., Buch T., Heppner F. L., Renauld J. C., Becher B. (2007). IL-22 is expressed by Th17 cells in an IL-23-dependent fashion, but not required for the development of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 179, 8098–8104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurschus F. C., Croxford A. L., Heinen A. P., Wortge S., Ielo D., Waisman A. (2010). Genetic proof for the transient nature of the Th17 phenotype. Eur. J. Immunol. 40, 3336–3346 10.1002/eji.201040755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhorne J., Ndungu F. M., Sponaas A. M., Marsh K. (2008). Immunity to malaria: more questions than answers. Nat. Immunol. 9, 725–732 10.1038/ni.f.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langrish C. L., Chen Y., Blumenschein W. M., Mattson J., Basham B., Sedgwick J. D., Mcclanahan T., Kastelein R. A., Cua D. J. (2005). IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 201, 233–240 10.1084/jem.20041257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. K., Turner H., Maynard C. L., Oliver J. R., Chen D., Elson C. O., Weaver C. T. (2009). Late developmental plasticity in the T helper 17 lineage. Immunity 30, 92–107 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Corraliza I., Langhorne J. (1999). A defect in interleukin-10 leads to enhanced malarial disease in Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi infection in mice. Infect. Immun. 67, 4435–4442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Sanni L. A., Omer F., Riley E., Langhorne J. (2003). Pathology of Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi infection and mortality in interleukin-10-deficient mice are ameliorated by anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha and exacerbated by anti-transforming growth factor beta antibodies. Infect. Immun. 71, 4850–4856 10.1128/IAI.71.7.3920-3926.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang S. C., Tan X. Y., Luxenberg D. P., Karim R., Dunussi-Joannopoulos K., Collins M., Fouser L. A. (2006). Interleukin (IL)-22 and IL-17 are coexpressed by Th17 cells and cooperatively enhance expression of antimicrobial peptides. J. Exp. Med. 203, 2271–2279 10.1084/jem.20061308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H. L., Liang S., Li J., Napierata L., Brown T., Benoit S., Senices M., Gill D., Dunussi-Joannopoulos K., Collins M., Nickerson-Nutter C., Fouser L. A., Young D. A. (2008). IL-22 is required for Th17 cell-mediated pathology in a mouse model of psoriasis-like skin inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 597–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangan P. R., Harrington L. E., O’Quinn D. B., Helms W. S., Bullard D. C., Elson C. O., Hatton R. D., Wahl S. M., Schoeb T. R., Weaver C. T. (2006). Transforming growth factor-beta induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature 441, 231–234 10.1038/nature04754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin B., Hirota K., Cua D. J., Stockinger B., Veldhoen M. (2009). Interleukin-17-producing gamma delta T cells selectively expand in response to pathogen products and environmental signals. Immunity 31, 321–330 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews K., Wilkinson K. A., Kalsdorf B., Roberts T., Diacon A., Walzl G., Wolske J., Ntsekhe M., Syed F., Russell J., Mayosi B. M., Dawson R., Dheda K., Wilkinson R. J., Hanekom W. A., Scriba T. J. (2011). Predominance of interleukin-22 over interleukin-17 at the site of disease in human tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 91, 587–593 10.1016/j.tube.2011.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meding S. J., Langhorne J. (1991). CD4+ T cells and B cells are necessary for the transfer of protective immunity to Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi. Eur. J. Immunol. 21, 1433–1438 10.1002/eji.1830210616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley T. A., Haudenschild D. R., Rose L., Reddi A. H. (2003). Interleukin-17 family and IL-17 receptors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 14, 155–174 10.1016/S1359-6101(03)00002-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mota M. M., Jarra W., Hirst E., Patnaik P. K., Holder A. A. (2000). Plasmodium chabaudi-infected erythrocytes adhere to CD36 and bind to microvascular endothelial cells in an organ-specific way. Infect. Immun. 68, 4135–4144 10.1128/IAI.68.7.4135-4144.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nograles K. E., Zaba L. C., Shemer A., Fuentes-Duculan J., Cardinale I., Kikuchi T., Ramon M., Bergman R., Krueger J. G., Guttman-Yassky E. (2009). IL-22-producing “T22” T cells account for upregulated IL-22 in atopic dermatitis despite reduced IL-17-producing TH17 T cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 123, 1244–1252 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea J. J., Paul W. E. (2010). Mechanisms underlying lineage commitment and plasticity of helper CD4+ T cells. Science 327, 1098–1102 10.1126/science.1178334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl M. W. (2001). A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT- PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, e45. 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitta M. G., Romano A., Cabantous S., Henri S., Hammad A., Kouriba B., Argiro L., El Kheir M., Bucheton B., Mary C., El-Safi S. H., Dessein A. (2009). IL-17 and IL-22 are associated with protection against human kala azar caused by Leishmania donovani. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 2379–2387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radaeva S., Sun R., Pan H. N., Hong F., Gao B. (2004). Interleukin 22 (IL-22) plays a protective role in T cell-mediated murine hepatitis: IL-22 is a survival factor for hepatocytes via STAT3 activation. Hepatology 39, 1332–1342 10.1002/hep.20184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitman S., Frankel S. (1957). A colorimetric method for the determination of serum glutamic oxalacetic and glutamic pyruvic transaminases. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 28, 56–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J., Feng Z., Lv Z., Chen X., Li J. (2011). Natural killer-22 cells in the synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis are an innate source of interleukin 22 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. J. Rheumatol. 38, 2112–2118 10.3899/jrheum.101377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutz S., Noubade R., Eidenschenk C., Ota N., Zeng W., Zheng Y., Hackney J., Ding J., Singh H., Ouyang W. (2011). Transcription factor c-Maf mediates the TGF-beta-dependent suppression of IL-22 production in T(H)17 cells. Nat. Immunol. 12, 1238–1245 10.1038/ni.2134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan-Payseur B., Ali Z., Huang D., Chen C. Y., Yan L., Wang R. C., Collins W. E., Wang Y., Chen Z. W. (2011). Virus infection stages and distinct Th1 or Th17/Th22 T-cell responses in malaria/SHIV coinfection correlate with different outcomes of disease. J. Infect. Dis. 204, 1450–1462 10.1093/infdis/jir549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt J. V., Bradfield C. A. (1996). Ah receptor signaling pathways. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 12, 55–89 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seixas E., Gozzelino R., Chora A., Ferreira A., Silva G., Larsen R., Rebelo S., Penido C., Smith N. R., Coutinho A., Soares M. P. (2009). Heme oxygenase-1 affords protection against noncerebral forms of severe malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 15837–15842 10.1073/pnas.0903419106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shio M. T., Kassa F. A., Bellemare M. J., Olivier M. (2010). Innate inflammatory response to the malarial pigment hemozoin. Microbes Infect. 12, 889–899 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonian P. L., Wehrmann F., Roark C. L., Born W. K., O’Brien R. L., Fontenot A. P. (2010). gammadelta T cells protect against lung fibrosis via IL-22. J. Exp. Med. 207, 2239–2253 10.1084/jem.20100061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenberg G. F., Fouser L. A., Artis D. (2011). Border patrol: regulation of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis at barrier surfaces by IL-22. Nat. Immunol. 12, 383–390 10.1038/nrg3010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman L. (2007). A brief history of T(H)17, the first major revision in the T(H)1/T(H)2 hypothesis of T cell-mediated tissue damage. Nat. Med. 13, 139–145 10.1038/nm1643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson M. M., Tam M. F., Belosevic M., Van Der Meide P. H., Podoba J. E. (1990). Role of endogenous gamma interferon in host response to infection with blood-stage Plasmodium chabaudi AS. Infect. Immun. 58, 3225–3232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streetz K. L., Tacke F., Leifeld L., Wustefeld T., Graw A., Klein C., Kamino K., Spengler U., Kreipe H., Kubicka S., Muller W., Manns M. P., Trautwein C. (2003). Interleukin 6/gp130-dependent pathways are protective during chronic liver diseases. Hepatology 38, 218–229 10.1016/S0270-9139(03)80171-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taube C., Tertilt C., Gyulveszi G., Dehzad N., Kreymborg K., Schneeweiss K., Michel E., Reuter S., Renauld J. C., Arnold-Schild D., Schild H., Buhl R., Becher B. (2011). IL-22 is produced by innate lymphoid cells and limits inflammation in allergic airway disease. PLoS ONE 6, e21799. 10.1371/journal.pone.0021799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trifari S., Kaplan C. D., Tran E. H., Crellin N. K., Spits H. (2009). Identification of a human helper T cell population that has abundant production of interleukin 22 and is distinct from T(H)-17, T(H)1 and T(H)2 cells. Nat. Immunol. 10, 864–871 10.1038/ni.1770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tupin E., Kronenberg M. (2006). Activation of natural killer T cells by glycolipids. Meth. Enzymol. 417, 185–201 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)17014-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unkeless J. C. (1979). Characterization of a monoclonal antibody directed against mouse macrophage and lymphocyte Fc receptors. J. Exp. Med. 150, 580–596 10.1084/jem.150.3.580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyttenhove C., Van Snick J. (2006). Development of an anti-IL-17A auto-vaccine that prevents experimental auto-immune encephalomyelitis. Eur. J. Immunol. 36, 2868–2874 10.1002/eji.200636662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhoen M., Hirota K., Westendorf A. M., Buer J., Dumoutier L., Renauld J. C., Stockinger B. (2008). The aryl hydrocarbon receptor links TH17-cell-mediated autoimmunity to environmental toxins. Nature 453, 106–109 10.1038/nature06881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veldhoen M., Hocking R. J., Flavell R. A., Stockinger B. (2006). Signals mediated by transforming growth factor-beta initiate autoimmune encephalomyelitis, but chronic inflammation is needed to sustain disease. Nat. Immunol. 7, 1151–1156 10.1038/ni1391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voisine C., Mastelic B., Sponaas A. M., Langhorne J. (2010). Classical CD11c+ dendritic cells, not plasmacytoid dendritic cells, induce T cell responses to Plasmodium chabaudi malaria. Int. J. Parasitol. 40, 711–719 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von der Weid T., Langhorne J. (1993). The roles of cytokines produced in the immune response to the erythrocytic stages of mouse malarias. Immunobiology 189, 397–418 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80367-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl C., Wegenka U. M., Leithauser F., Schirmbeck R., Reimann J. (2009). IL-22-dependent attenuation of T cell-dependent (ConA) hepatitis in herpes virus entry mediator deficiency. J. Immunol. 182, 4521–4528 10.4049/jimmunol.0802810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther M., Woodruff J., Edele F., Jeffries D., Tongren J. E., King E., Andrews L., Bejon P., Gilbert S. C., De Souza J. B., Sinden R., Hill A. V., Riley E. M. (2006). Innate immune responses to human malaria: heterogeneous cytokine responses to blood-stage Plasmodium falciparum correlate with parasitological and clinical outcomes. J. Immunol. 177, 5736–5745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitten R., Milner D. A., Jr., Yeh M. M., Kamiza S., Molyneux M. E., Taylor T. E. (2011). Liver pathology in Malawian children with fatal encephalopathy. Hum. Pathol. 42, 1230–1239 10.1016/j.humpath.2010.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk K., Kunz S., Witte E., Friedrich M., Asadullah K., Sabat R. (2004). IL-22 increases the innate immunity of tissues. Immunity 21, 241–254 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolk K., Sabat R. (2006). Interleukin-22: a novel T- and NK-cell derived cytokine that regulates the biology of tissue cells. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 17, 367–380 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2006.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing W. W., Zou M. J., Liu S., Xu T., Gao J., Wang J. X., Xu D. G. (2011). Hepatoprotective effects of IL-22 on fulminant hepatic failure induced by d-galactosamine and lipopolysaccharide in mice. Cytokine 56, 174–179 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M., Morishima N., Mizoguchi I., Chiba Y., Fujita K., Kuroda M., Iwakura Y., Cua D. J., Yasutomo K., Mizuguchi J., Yoshimoto T. (2011). Regulation of the development of acute hepatitis by IL-23 through IL-22 and IL-17 production. Eur. J. Immunol. 41, 2828–2839 10.1002/eji.201141291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenewicz L. A., Yancopoulos G. D., Valenzuela D. M., Murphy A. J., Karow M., Flavell R. A. (2007). Interleukin-22 but not interleukin-17 provides protection to hepatocytes during acute liver inflammation. Immunity 27, 647–659 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenewicz L. A., Yancopoulos G. D., Valenzuela D. M., Murphy A. J., Stevens S., Flavell R. A. (2008). Innate and adaptive interleukin-22 protects mice from inflammatory bowel disease. Immunity 29, 947–957 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Cobleigh M. A., Lian J. Q., Huang C. X., Booth C. J., Bai X. F., Robek M. D. (2011). A proinflammatory role for interleukin-22 in the immune response to hepatitis B virus. Gastroenterology 141, 1897–1906 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Danilenko D. M., Valdez P., Kasman I., Eastham-Anderson J., Wu J., Ouyang W. (2007). Interleukin-22, a T(H)17 cytokine, mediates IL-23-induced dermal inflammation and acanthosis. Nature 445, 648–651 10.1038/nature05505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Chong M. M., Littman D. R. (2009). Plasticity of CD4+ T cell lineage differentiation. Immunity 30, 646–655 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]