Abstract

The nitric oxide (NO) signaling pathway is integrally involved in visual processing and changes in the NO pathway are measurable in eyes of diabetic patients. The small peptide adrenomedullin (ADM) can activate a signaling pathway to increase the enzyme activity of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS). ADM levels are elevated in eyes of diabetic patients and therefore, ADM may play a role in the pathology of diabetic retinopathy. The goal of this research was to test the effects of inhibiting the ADM/NO signaling pathway in early diabetic retinopathy. Inhibition of this pathway decreased NO production in high-glucose retinal cultures. Treating diabetic mice with the PKC β inhibitor ruboxistaurin for 5 weeks lowered ADM mRNA levels and ADM-like immunoreactivity and preserved retinal function as assessed by electroretinography. The results of this study indicate that inhibiting the ADM/NO signaling pathway prevents neuronal pathology and functional losses in early diabetic retinopathy.

Keywords: Nitric oxide, Adrenomedullin, Diabetic retinopathy, Ruboxistaurin, PKC β

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is the leading cause of blindness among working age adults in the developed world [1]. DR is characterized by both neuronal dysfunction and the breakdown of retinal vasculature [2]. The vascular complications play a critical role in disease progression and are clinically detectable. As a consequence, many studies have approached DR as being primarily vascular in its etiology. However, the neuronal dysfunction occurs early in DR and may precede vascular breakdown [3, 4].

Evidence of early neuronal dysfunction is detectable by electroretinography (ERG) before any visible vascular damage in diabetic rats [3, 4] and humans [5, 6]. Evidence for changes in visual processing has been seen after as little as 2 weeks in diabetic rats [7], while discernible vascular changes are reported to occur only after 6 months to 1 year [8]. Similarly, just 2 years after diabetes onset (in humans), there is a decrease in color and contrast sensitivity, and the ERG begins to change [9–11], while major vascular changes do not typically occur until 5–10 years after disease onset [3].

Several neurochemical changes have been documented early in the diabetic retina. For example, Leith et al. [12] found increased glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in Müller cells, along with increased levels of glutamate and impaired breakdown of glutamate into glutamine. There is an increase in retinal neuron apoptosis early in DR that precedes vascular damage in both rodents and humans [13]. The presynaptic proteins synaptophisin, synapsin 1, VAMP2, SNAP25, and PSD95 all show decreases after only 1 month of diabetes, especially when synaptosomal fractions are selectively examined [14]. A study by Kern et al. [15] showed that early vascular damage was prevented in rats by administering the COX inhibitor nepafenac, but retinal ganglion cell apoptosis still occurred, denoting a separation between vascular and neuronal damage.

Nitric oxide (NO) is an important signaling molecule in the vertebrate retina found to either be produced by, or have effects in, every retinal cell type [16]. There is evidence for increased NO in both the vitreous and aqueous humors of patients with DR [17, 18]. We have previously shown that neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) is the primary source of neuronal NO and the most abundant isoform of NOS in the retina [19–21]. More recently, we have shown that there is a significant increase in NO in early DR, despite a decrease in nNOS protein levels. These data suggest that increased nNOS activity in early DR is due to a posttranslation modification of nNOS [22].

ADM is a 52 amino acid multifunctional regulatory peptide [23] that is produced by neurons, glial cells, vascular endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells, among others [24]. The primary ADM receptor is the G-protein coupled receptor calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CRLR), which requires receptor-activity modifying proteins (RAMPs) for activity [25]. Co-expression of CRLR with RAMP-2 or RAMP-3 results in an ADM selective receptor. ADM acts to increase Ca2+ by releasing intracellular ryanodine- and thapsigargin-sensitive Ca2+ stores through protein kinase A (PKA) associated mechanisms [26, 27]. ADM can increase cAMP levels in retinal pigment epithelium [28]. Most importantly, ADM-stimulated increases in intracellular Ca2+ can directly stimulate NO production [26, 29].

Evidence supports that ADM is involved in the pathophysiology of many aspects of diabetes [24]. ADM is elevated in the vitreous of patients with DR [30, 31] and proliferative vitreoretinopathy [32]. Type 2 [33, 34] and type 1 [35] diabetic patients with retinopathy have significantly higher plasma levels of ADM than control patients and diabetic patients without vascular retinopathy. Additionally, in the eye, ADM increases vascular permeability [36], and ADM administered peripherally can cause ocular inflammation [37].

Substantial evidence suggests that hyperglycemia-induced synthesis of diacylglycerol (DAG) results in the activation of protein kinase C β (PKC β), which plays a central role in mediating the ocular complications of diabetes [38, 39]. Diabetes-induced activation of PKC β increases both retinal vascular permeability and neovascularization in animal models [40–42]. Protein kinase β also mediates changes in retinal blood flow in patients with diabetes [43]. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a mediator of retinal neovascularization and increased permeability in diabetes [42, 44, 45], activates PKC β.

High glucose increases both ADM mRNA and PKC activity, and PKC inhibitors block the increases in ADM mRNA [46]. In addition, there is an increase in adenylate cyclase activity in diabetic retinas [47], and the ADM gene has both PKC- and cAMP-regulated enhancer elements [48]. The PKC-regulated enhancers are consistent with hyperglycemic increases in vascular ADM expression [46] and with PKC-stimulated increases in ADM mRNA [49].

Ruboxistaurin (RBX), an orally administered PKC β isozyme-selective inhibitor, ameliorates the adverse effects of high glucose in animals [41, 50–53] and diabetes-induced retinal blood flow abnormalities in patients, demonstrating that RBX reaches the human retina in bioeffective concentrations [42]. A phase III study (NPDR; PKC-DRS study group) revealed a potentially beneficial effect of RBX on the secondary end point of sustained moderate visual loss (SMVL) in patients with moderately severe to very severe nonproliferative DR. Another phase III study, Protein Kinase C Inhibitor-Diabetic Retinopathy Study 2 (PKC-DRS2), which examined SMVL over a 3 year period, found reduced vision loss, reduced need for laser treatment, reduced macular edema progression, and increased occurrence of visual improvement in patients with nonproliferative retinopathy [54–56]. Although RBX reduced vision loss, it had no effect on the progression of nonproliferative DR to proliferative DR [55].

In this study, we examined the ADM/NO signaling pathway in early diabetic retinopathy. We showed that NO production is increased in high-glucose retinal cultures and that ADM mRNA and ADM-like immunoreactivity (LI) increase in 5-week diabetic mice. The increase in NO production in high-glucose retinal cultures can be inhibited by the calcineurin inhibitor FK-506 and the PKC β inhibitor LY376196 (Eli Lilly). In 5-week diabetic mice treated with the PKC β inhibitor RBX, ADM mRNA levels and ADM-LI decrease, and normal nNOS-LI is restored. Additionally, as assessed by ERG, mice with DR for 5 weeks and treated with RBX had enhanced bipolar cell function and increased amplitudes and decreased implicit times in the oscillatory potentials (OPs), indicating that the inhibition of the ADM/NO signaling pathway with RBX protected against some of the functional losses and neuronal pathology in early DR. Although many studies have examined the effects of RBX on the vascular pathology, to our knowledge, the effects of RBX on the early neuronal pathology have not been examined, although it does reduce vision loss [57].

Methods

Unless specified otherwise, all reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) or ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). All images were labeled, arranged, and prepared for display using Corel Draw™ (Corel Corp., Ottawa, ON), unless otherwise noted.

Animals

Adult, male C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA) and were kept on 12-h light/12-h dark cycles, with free access to food and water. All animals were treated using protocols approved by the Boston University Charles River Campus Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Streptozotocin-induced diabetic mouse model

For the in vivo studies, we examined ten control mice, ten mice with diabetes, and ten diabetic mice treated with the PKC β inhibitor ruboxistaurin (RBX, Eli Lilly). Diabetes was induced in adult male C57BL/6 mice using the protocol from the Animal Models of Diabetic Complications Consortium. Mice were fasted each day for five consecutive days for approximately 4 h prior to a single intraperitoneal injection of 50-mg/kg streptozotocin (STZ, Sigma-Aldrich) in 100-mM sodium citrate buffer, pH 4.5. Blood glucose levels were tested with a FreeStyle Flash blood glucose meter, and the mice were considered diabetic if their fasting blood glucose level was over 250 mg/dl. After 5 weeks, the mice were euthanized, and their retinas were isolated and harvested for RNA isolation, or they were fixed and processed for immunocytochemistry. During these 5 weeks, some animals were treated with the PKC β inhibitor RBX (30 mg/kg/day in chow). The dosage of RBX in the mouse chow provided by Eli Lilly for the in vivo experiments was chosen on the basis of their bioavailability and metabolic experiments [58].

Immunocytochemistry (ICC)

Animals were first heavily anesthetized using IsoFlo isoflurane gas (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL) and then decapitated. The eyes were then enucleated, and the anterior chambers were immediately removed in ice-cold rodent balanced salt solution (BSS; 137-mM NaCl, 5-mM KCl, 2-mM CaCl2, 15-mM D-glucose, 1-mM MgSO4, 1-mM Na2HPO4, 10-mM HEPES, pH 7.4) and then placed directly into 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1-M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 (PB) for 60 min or overnight. The eyecups were then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PB, embedded and frozen in Optimal Cutting Temperature embedding media (OCT; Tissue-Tek, Miles, Inc., Elkhard, IN), cut into 14-μm-thick cross-sections using a cryostat, and then collected on Superfrost/Plus slides (ThermoFisher Scientific). ICC was done using previously described conventional methods [59]. Cross-sections were incubated overnight with either goat or rabbit polyclonal ADM antisera or rabbit polyclonal nNOS antiserum (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; sc-1646 or sc-3187 at 1:100, and sc-648 at 1:100, respectively) in PB with 0.3% Triton X-100 (PBTX). To control for specificity, the goat ADM antiserum was incubated overnight with the synthetic peptide it was raised against (ADM C-20 P sc-16496) before it was incubated with cross-sections. The rabbit polyclonal nNOS antiserum was previously characterized in mouse retina [21]. The secondary antisera used were an Alexa Fluor® 555-conjugated donkey anti-goat or donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) used at a dilution of 1:500 in PBTX. Incubation with only secondary antiserum was used as a control for nonspecific secondary antiserum staining. Finally, the slides were washed in PB, cover slipped with glycerol, and the fluorescent labeling was visualized using an Olympus Fluoview 300 confocal microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY). ImageJ image analysis software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/, Wayne Rasband, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD) was used to convert images to inverted gray scale such that the immunoreactivity appeared black. The z project function of ImageJ was used to obtain a single image from a collapsed confocal optical stack.

RNA isolation, reverse transcription, and q-PCR

All animals were first anesthetized using isoflurane gas and then decapitated as described previously. Following decapitation, the retinas were surgically isolated in RNAse-free rodent BSS and placed immediately in 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes on dry ice. Total RNA was then isolated using a standard Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) extraction, followed by further purification using Qiagen’s Rneasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) with modifications as described previously by Giove et al. [21]. The RNA was then treated with rDNase™ (Ambion, Applied Biosystems) based on the manufacturer’s instructions to remove any DNA contaminants. The RNA was quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). cDNA was then made using the Verso cDNA kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) and subsequently treated with 2 U of RNase H (ThermoFisher Scientific) at 37°C for 20 min.

Quantitative real-time PCR was done using cDNA converted from 1 μg of retinal RNA and analyzed using an ABI Prism 7900HT Sequence Detection System. We used a prevalidated Taqman Assay (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) for mouse ADM directed between exons 1 and 2 (assay ID Mm01280688). We used a previously optimized primer set for the 18 s rRNA (5′-GTAAACCGTTGAACCCCATT-3′ and 5′-CCATCCAATCGGTAGTAGCG-3′), which was designed to work with SyberGreen methodology as an internal control. Data were analyzed using the 2-ΔΔCT method as described by Livak and Schmittgen [60].

Nitrite analysis

Retinal cultures incubated for 6 h in glucose concentrations 5-mM to 20-mM glucose were used to identify early changes in NO metabolites in an in vitro system. Ten adult male C57BL/6 mice were euthanized, their eyes were enucleated, and their retinas were isolated intact. The retinas were incubated photoreceptor side down in Ames culture media with either 5-mM glucose (normal glucose) or 20-mM glucose (high glucose) at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 6 h. Some 6-h cultures were treated with either the calcineurin inhibitor FK-506 (1 μM, A.G. Scientific) or the PKC β inhibitor LY379196 (30 nM, Eli Lilly). The in vitro dosage of 30-nM LY379196 was chosen on the basis of the IC50 value of 6 nM for PKCβII, versus 360 nM for PKCα and 600 nM for PKCε [61]. The culture media were collected and used for nitrite analysis, and the retinas were homogenized to determine total protein levels using a modified Bradford assay. Nitrite analysis was done using a modified Griess reaction using vanadium (III) chloride to convert nitrate to nitrite [62]. Nitrite levels were normalized to total protein levels, and the results were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA.

Electroretinograms (ERGs)

Retinal function was assessed in ten control, ten diabetic, and ten RBX-treated diabetic mice by ERG. Specifics of the recording and analysis procedures are presented elsewhere [63, 64]. In brief, dark-adapted, anesthetized (ketamine/xylazine) mice’s pupils were dilated (Cyclomydril; Alcon, Fort Worth, TX), and their corneas were anesthetized (proparacaine). A Burian–Allen bipolar electrode designed for the mouse eye (Hansen Laboratories, Coralville, IA) was placed on the right cornea, and the ground electrode was placed on a foot. The stimuli consisted of a series of “green” LED flashes of doubling intensity from ~0.0064 to ~2.05 cd⋅s⋅m−2 and then “white” xenon-arc flashes from ~8.2 to ~1050 cd⋅s⋅m−2. The “equivalent light” for the green and white stimuli was determined from the shift of the stimulus/response curves for the scotopic b-wave in an intensity series with interspersed green and white flashes; the white flash was found to be half as efficient (per cd⋅s⋅m−2) at eliciting a b-wave [63]. The response to a 1.024-cd⋅s⋅m−2 green light flickering at 8 Hz in the presence of a 10-cd⋅m−2 amber background was also recorded; this background suppressed the saturating rod photoresponse by >90%, providing a measure of activity in the cone pathway.

The amplitude and sensitivity of the saturating rod photoresponse were estimated from the ERG by optimization, using a square error minimization routine (fminsearch; MATLAB, The Mathworks, Natick, MA), of the free parameters of the Hood and Birch [65] formulation of the Lamb and Pugh [66, 67] model of the biochemical processes involved in the activation of phototransduction. The model

|

1 |

was ensemble fit to the leading edge of a-waves elicited by the five brightest flashes. In this model, i is the intensity of the flash (cd·s·m−2), and t is the elapsed time (s). RmP3 is the amplitude (μV) parameter; it is proportional to the magnitude of the dark current. S is the sensitivity (cd−1·s−3·m2) parameter; it summarizes the kinetics of the process initiated by the capture of light by rhodopsin and resulting in closure of the channels in the plasma membrane of the photoreceptor. td is a brief delay (s).

The postreceptor response, P2, was obtained by digitally subtracting the derived photoreceptor response, P3 (Eq. 1), from the intact ERG. P2 originates mostly in the bipolar cells [68–70]. The amplitude and sensitivity of the rod bipolar cell response were ascertained by fit of the Naka–Rushton equation,

|

2 |

to the response vs. intensity relationship of P2. In Eq. 2, P2(i) is the amplitude (μV) of the bipolar cell response to a stimulus of i intensity, RmP2 is the saturated amplitude (μV) of P2, and kP2 is the flash intensity that elicits a half-maximum P2. kP2 served as the measure of b-wave sensitivity.

The OPs characterize activity in retinal cells distinct from those that generate the a- and b-waves, although photoreceptors and bipolar cells do contribute [71, 72]. The OPs were analyzed, ensemble, in the frequency domain following discrete Fourier transform of the first 128 ms of P2, as previously described [73]. The saturating energy in the OPs, Em (∝J), was derived (similarly to RmP2, Eq. 2) by fit of the Michaelis–Menten equation to the response vs. intensity relationship of OP energy. Em is related to the square of the amplitude of the OPs [73], and thus, its root (Em½) was tested in all analyses.

Finally, to evaluate a cone-mediated response, the trough-to-peak amplitude of the light-adapted, 8-Hz flicker response (A8) was measured.

All of the aforementioned ERG parameters were analyzed as ΔLogNormal, such that changes in parameter values of fixed proportion, up or down, were linear [63].

The implicit times of the OPs are also altered by DR [74], but all reference to timing is lost following Fourier transform. Thus, the individual troughs and peaks of the OPs were also respectively evaluated. Summed OP amplitude (SOPA) and summed OP implicit time (SOPIT) were then evaluated as a function of flash intensity following logarithmic transform.

All ERG records were processed offline in a masked fashion.

Results

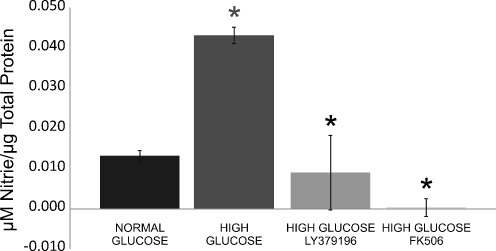

Inhibition of the ADM/NO signaling pathway decreases NO metabolites in high-glucose retinal cultures

The NO breakdown metabolite nitrite was used as a measure of NO production in the culture media from 6-h retinal cultures. When compared to normal glucose (~6 mM), there was a statistically significant increase (P < 0.001) in nitrite in the culture media from retinas that were incubated in high glucose (20 mM). In high-glucose cultures that were incubated with the PKC β inhibitor LY379196 (30 nM), there was a statistically significant decrease (P < 0.001) in nitrite. When high-glucose retinal cultures were incubated the calcineurin inhibitor FK-506 (1 mM), there was also a statistically significant decrease (P < 0.001) in nitrite (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of the ADM pathway decreases NO metabolites. Isolated retinas were cultured in Ames media for 6 h, in normal glucose (~6 mM), and high glucose (20 mM), with and without the PKC β inhibitor LY379196 or the calcineurin inhibitor FK-506. Nitrite levels in the culture media were measured and normalized to total protein levels. There was a statistically significant increase in nitrite from retinas that were incubated in high glucose, and there was a statistically significant decrease in nitrite when isolated retinas were inhibited in high glucose with either LY379196 or FK506. An asterisk denotes P < 0.001

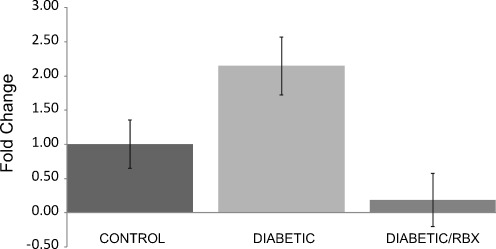

Increases in ADM mRNA levels in 5-week diabetic mice are inhibited by PKC β

Taqman assays from Applied Biosystems were used for quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) for ADM message. Levels of mRNA for ADM were normalized to control levels in order to determine a relative fold change. There was a 2.15 (± 0.42)-fold increase in ADM mRNA levels in 5-week diabetic mice. ADM mRNA levels decreased 0.19 (± 0.39)-fold in diabetic mice that were treated with the PKC β inhibitor RBX (30 mg/kg/day in chow), indicating that inhibition of PKC β decreases ADM mRNA expression in 5-week diabetic mice (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Inhibition of PKC β reduces ADM mRNA levels. In order to determine if ADM mRNA levels were modulated in early diabetic retinopathy, qPCR was done using a prevalidated Taqman™ assay designed for mouse ADM. There was a 2.15 (± 0.42)-fold increase in retinal ADM mRNA levels in 5-week diabetic mice. In diabetic mice that were treated with the PKC β inhibitor RBX for 5 weeks, there was a 0.19 (± 0.39)-fold decrease in retinal ADM message

Inhibition of the ADM/NO signaling pathway decreases ADM-LI and restores normal nNOS-LI

ADM-LI in 5-week diabetic mice

We were not able to reliably confirm the specificity of either of the ADM antisera using western blots. However, we could establish their immunocytochemical specificity because, although each of the two different ADM antisera was directed against a different epitope on ADM, they produced similar labeling. The antiserum sc-16496 from Santa Cruz was directed against an epitope mapping within an internal region of ADM. In contrast, the sc-33187 antiserum was directed against an epitope corresponding to amino acids 1–185 representing full length ADM of human origin. Both antisera detected ADM-LI in somata in the middle of the inner nuclear layer (INL), in puncta in the IPL, and in somata in the ganglion cell layer (GCL) (Fig. 3a). In 5-week diabetic mice, there was an increase in ADM-LI (Fig. 3b), and this increase in ADM-LI was reduced in 5-week mice that were treated with the PKC β inhibitor RBX (30 mg/kg/day in chow; Fig. 3c). Additionally, we showed no staining in control tissue when the sc-16496 antiserum was preabsorbed with the synthetic peptide it was raised against (Fig. 3d).

Fig. 3.

Increases in ADM-LI in early diabetic retinopathy were inhibited by RBX. In control mice, ADM-LI was detected in somata in the middle of the INL, in puncta in the IPL, and in somata in the GCL (a). In 5-week diabetic mice, there was a clear increase in ADM-LI (a versus b). This increase in ADM-LI was blocked by the PKC β inhibitor RBX (c). Scale bars = 25 μm. Absorption control (d)

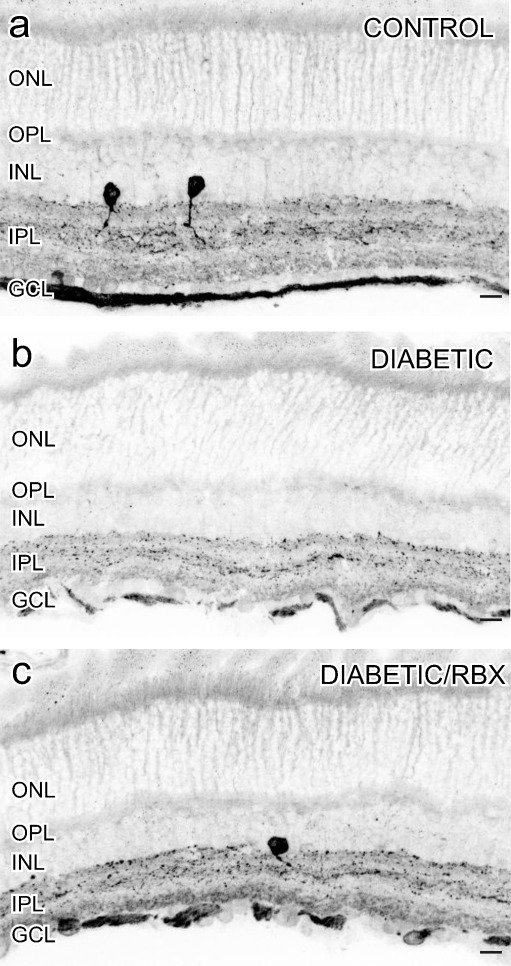

nNOS-LI in 5-week diabetic mice

In a previous study, it was shown that there is an increase in NO production in 5-week diabetic mice, although there is a decrease in nNOS-LI and protein levels [22]. We used an antiserum directed against the C-terminus of nNOS which was previously characterized by Giove et al. [22]. In the control retinas (Fig. 4a), there was a faint nNOS-LI in presumptive bipolar cell somata in the INL. In the inner retina, a strong nNOS-LI was present in the somata and processes of select amacrine cells. Some somata in the GCL had nNOS-LI, and it was likely that at least some of these cells were ganglion cells because there was nNOS-LI in the ganglion cell axon layer. In 5-week diabetic retinas (Fig. 4b), the overall levels of nNOS-LI decreased, and there was also less banding and more puncta in the IPL, which was consistent with results of Giove et al. [22]. When diabetic mice were treated with RBX (30 mg/kg/day in chow), nNOS-LI levels were restored to more normal levels and localizations (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of PKC β restored nNOS-LI in early diabetic retinopathy. In control retinas, a faint nNOS-LI was located in presumptive bipolar cell somata in the INL. In the inner retina, a strong nNOS-LI was present in the somata and processes of select amacrine cells and in somata in the GCL (a). In 5-week diabetic mice, there was a clear decrease in nNOS-LI in amacrine cell somata and the IPL in diabetic retinas (a versus b). This decrease in nNOS-LI was restored by the PKC β inhibitor RBX (c). Scale bars = 25 μm

Inhibition of the ADM/NO signaling pathway improves oscillatory potentials in diabetic mice

Neither amplitude (RmP3) nor sensitivity (S) of the photoreceptor response was significantly altered by diabetes, although untreated diabetic retinas’ a-waves were the smallest and least sensitive on average (Fig. 5a–b). The saturating amplitude of the bipolar cells’ ERG responses (RmP2) similarly did not differ significantly between control, diabetic, and RBX-treated diabetic mice, but again were smallest in the untreated diabetic animals (Fig. 5c). Postreceptor sensitivity (kP2), on the other hand, was significantly (P = 0.009) attenuated in diabetic mice relative to both control and RBX-treated diabetic mice (Fig. 5d). In fact, treatment with RBX almost completely restored postreceptor sensitivity. We note that Shirao and Kawasaki [74] conclude that the oscillatory potentials (OPs) are the first ERG components affected in diabetes and OP changes are a better predictor of DR in humans than fundus photography or fluorescein angiograms [75]. Indeed, the saturating energy in the oscillatory potentials (Em) was significantly (P = 0.045) attenuated in untreated diabetic mice; treatment, once again, was fully restorative of OP energy (Fig. 5e). Finally, the cone-mediated flicker response (A8) was not significantly altered by diabetes or treatment, but again showed evidence of decline in untreated diabetes that were mitigated by treatment (Fig. 5f).

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of PKC β improved ERGs in early diabetic retinopathy. ERG data are plotted such that bars represent mean deficits in retinal function (± SEM) after 5 weeks of STZID relative to control. Saturating photoreceptor response amplitude (a) and sensitivity (b) were not significantly affected by STZID. Postreceptor response amplitude (c) was similarly unaffected, but postreceptor sensitivity (d) was significantly lower in untreated diabetic mice and completely restored by PKC β inhibition. Saturating energy in the oscillatory potentials (e) was likewise significantly impaired by diabetes and protected by PKC β inhibition. The cone-mediated flicker response (f) was not significantly affected by STZID. Note that, even when not significant, all ERG parameters studied trended worst in the untreated diabetic group

Closer inspection of the summed OP amplitudes (SOPA) and implicit times (SOPIT) revealed striking and highly significant evidence of neuroprotection with RBX in the diabetic mice (Fig. 6a–b). At every intensity, the OPs were smaller (P = 0.012) and slower (P = 0.001) in the untreated diabetic mice than in the controls, but the OPs in treated diabetic mice was nearly indistinguishable from normal.

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of PKC β improves OPs, especially, in early diabetic retinopathy. At every flash intensity, the summer amplitude (a) and implicit time (b) of the OPs were indistinguishable in control animals and in diabetic mice treated with RBX. In contrast, untreated diabetic mice showed markedly smaller, slower OPs

Discussion

Early diabetic retinopathy

For many years, DR has been defined as a vascular pathology characterized by increased vascular permeability, which leads to edema and endothelial and pericyte cell death [76]. This vascular-based definition has been expanded, given the many recent reports describing early electrophysiological pathology and neuronal/glial degenerative changes that precede the vascular changes in both humans and animals [4, 77, 78]. In rodents, these retinal changes produce significant reductions in both visual acuity and contrast sensitivity after only 1 month of hyperglycemia [79]. Diabetic patients with no clinically detectable DR, nevertheless show impairment of their ERG pattern responses, b-wave scotopic bright flash ERGs, a- and b-wave photopic single flash ERGs, and their oscillatory potential responses [80]. Optical coherence tomography reveals significant thinning in the GCL, ganglion cell fiber layer, and INL in diabetic patients with no or minimal vascular DR [81, 82]. These results indicate that both diabetic patients and animals have similar specific early neuronal defects that occur before the vascular pathology. However, the cause of the early neuronal pathology is not known.

Nitric oxide and diabetic retinopathy

NO is an important signaling molecule in the vertebrate retina, and there have been several studies which have examined the relationship between NO and diabetic retinopathy. Yilmaz et al. [17] report elevated levels of NO in the vitreous of patients with proliferative DR. Hattenbach et al. [18] report increases in NO metabolites in the aqueous humor of diabetic patients with and without vascular pathology, which indicates that NOS activity is increased in the early stages of DR. In mice with 5 weeks of STZ-induced DR, there are strongly increased levels of NO but decreased levels of nNOS protein [22], which indicates that there is a posttranslational activation of nNOS that leads to increased levels of NO.

Modulation of nNOS activity by ADM

There are several regulatory phosphorylation sites on nNOS that can modify its function. Most phosphorylation events are inhibitory for nNOS, which include Ser847 [83, 84], Ser741 [85], and Thr1296 [86]. The excitatory phosphorylation sites are less understood; however, Ser1451 appears to be excitatory for nNOSμ [87]. The inhibitory site at Ser847 is thought to be one of the major sites of nNOS phosphorylation [83, 88], and phosphorylation of nNOS at Ser847 can occur in close proximity to NMDA receptors at the excitatory synapse [84]. nNOS phosphorylated at Ser847 is approximately 60% less active when compared to dephosphorylated nNOS [83, 88, 89]. This inhibition is reversed by removal of the phosphate group by several phosphatases, including protein phosphatase 1 (PP1), PP2A, and calcineurin (also called PP2B, [90]). Xu and Krukoff [29] find that calcineurin is the phosphatase that has the greatest influence on nNOS dephosphorylation and its activity increase.

It is unlikely that an increase in Ca2+ alone accounts for the increase in nNOS activity observed in the diabetic retina, given the decrease in protein. Therefore, an additional pathway involved in the diabetic retina would help explain the greater nNOS activity. The activation of the cAMP/PKA/Ca2+ cascade by ADM activates calcineurin (PP2B) to dephosphorylate nNOS at Ser847, which, in turn, activates nNOS to increase NO production [29]. Therefore, ADM can stimulate NO production in two distinct ways: by increasing intracellular Ca2+ to directly activate nNOS and by activating calcineurin to activate nNOS through dephosphorylation. Thus, lowering retinal ADM levels will reduce retinal NO in two ways.

Kikuchi et al. [91] report that inhibition of calcineurin by FK-506 completely inhibits glutamate-stimulated retinal NOS activity. Our data support that inhibition of calcineurin with FK-506 decreases NO production. In retinal cultures, the calcineurin inhibitor FK-506 prevents the high-glucose-stimulated increases in NO metabolites (Fig. 1).

Interrelated aspects of ADM and NO also create positive feedback loops to enhance further NO production. NO donors increase the binding efficiency of ADM to its receptor by over 50% through a cGMP-dependent pathway [92]. NO donors also significantly increases ADM secretion and increases ADM mRNA expression four- to ten-fold [93]. The results of these NO-stimulated increases in ADM and ADM receptor binding would further increase NO production. The angiogenic effects of ADM and the up-regulation of VEGF by ADM [94] may also play a role in neovascularization seen in DR. There are increased levels of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-2) in DR [95, 96], and MMP-2 cleaves ADM into a smaller fragment, ADM(11-22), which has a vasoconstrictor effect [97], which could further contribute to the pathology in DR. Here, we were able to provide evidence for an increase in ADM message and ADM-LI in early diabetic retinopathy (Figs. 2 and 3).

The role of PKC and ruboxistaurin in diabetic retinopathy

Increased PKC activity has been reported in diabetic retinopathy. Kowluru [98] reports that in diabetic rats or cultured intact retinas from normal rats incubated with 30-mM glucose for 6 h, there is elevated retinal PKC activity and NO levels; all of which are prevented by inhibiting PKC with RBX. However, the exact mechanism was not established.

In addition, there is increased basal adenylate cyclase activity in diabetic retinas [47], and the ADM gene has both PKC- and cAMP-regulated enhancer elements [48]. High glucose increases both ADM mRNA and PKC activity, and PKC inhibitors block the increases in ADM mRNA [46]. The PKC-regulated enhancers are consistent with hyperglycemic increases in vascular ADM expression [46] and with PKC-stimulated increases in ADM mRNA [49]. Inhibition of PKC β with RBX was well tolerated in clinical trials with diabetic patients, where it was shown to ameliorate retinal hemodynamic abnormalities [54] and slow visual loss [99]. In STZID rat retinas, there are increases in PKCα, PKCβI, PKCβII, and PKCε, with the greatest increases in PKCβII [100].

Figure 7 diagrams the proposed ADM signaling pathway in retina. Our goal was to treat mice with RBX in hopes that it would lower the pathologically increased levels of ADM and reduce NO levels which could ameliorate the early neuronal pathology. Although many studies have examined the effects of RBX on the vascular pathology, to our knowledge, the effects of RBX on the early neuronal pathology have not been examined, although it does slow vision loss [57]. The PKC β inhibitor LY376196 decreased nitrite levels in the media of 6-h, 20-mM glucose retinal cultures (Fig. 1). Additionally, the PKC β inhibitor RBX lowered levels of ADM mRNA and ADM-LI, and it restored normal nNOS-LI in diabetic mice in vivo. nNOS can be broken down by the Ca2+ binding protein calpain [101, 102]. If RBX reduces Ca2+ levels that would have been increased by activation of the ADM signaling pathway, it is reasonable that calpain would not be activated to breakdown nNOS. The inhibition of the ADM/nNOS/NO signaling pathway with the PKC β inhibitor RBX prevented the functional losses in the ERG and reduced the increased levels of NO in early diabetic retinopathy.

Fig. 7.

Summary diagram of the proposed ADM signaling pathway in retina. Protein kinase C (PKC) activation leads to increased transcription of the ADM gene via a PKC enhancer element. The ADM precursor preproadrenomedullin is cleaved to proadrenomedullin which is then cleaved into the secreted peptide ADM and the proadrenomedullin NH2-terminal peptide (PAMP). ADM is secreted and binds to the G protein coupled receptor calcitonin receptor like receptor (CRLR) that is associated with either the receptor activity modifying protein RAMP2 or RAMP3 to activate a signaling cascade that increases cAMP by activating adenylyl cyclase. Increases in cAMP levels activate protein kinase A (PKA), which increases calcium levels by opening membrane calcium channels or by releasing intracellular calcium stores. The overall increase in intracellular calcium can increase NO production by directly stimulating nNOS or by activating nNOS through the activation of the calcium-activated phosphatase, calcineurin (CaN), which dephosphorylates nNOS at an inhibitory phosphorylation site at serine847. Increases in NO production can then increase cGMP synthesis by activating soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC). The ADM signaling pathway is inhibited by a PKC β inhibitor and the calcineurin inhibitor FK-506

Future studies should elucidate the mechanism by which the ADM signaling pathway increases NO in early diabetic retinopathy. Specifically, the dephosphorylation of nNOS phospho-serine847 by calcineurin should be investigated. We were unable to confirm the specificity of several commercial nNOS phospho-serine847 antisera, and therefore, we were not able to confirm a modulation of phosphorylated NOS. Development of better phospho-serine847 antisera will be required for such studies. It will also be important to explore the potential connection that ADM could have between the neuronal and vascular complications in early DR.

Acknowledgements

We wish to sincerely thank Todd Blute for his technical assistance. This research was supported by NIH EY004785 to WDE and NIH RC1-EY020308 to JDA.

References

- 1.Aiello LM. Perspectives on diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136:122–135. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(03)00219-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonetti DA, Barber AJ, Bronson SK, Freeman WM, Gardner TW, Jefferson LS, Kester M, Kimball SR, Krady JK, LaNoue KF, Norbury CC, Quinn PG, Sandirasegarane L, Simpson IA. Diabetic retinopathy: seeing beyond glucose-induced microvascular disease. Diabetes. 2006;55:2401–2411. doi: 10.2337/db05-1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lieth E, Gardner TW, Barber AJ, Antonetti DA. Retinal neurodegeneration: early pathology in diabetes. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2000;28:3–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-9071.2000.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barber AJ. A new view of diabetic retinopathy: a neurodegenerative disease of the eye. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27:283–290. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00023-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leo MA, Caputo S, Falsini B, Porciatti V, Greco AV, Ghirlanda G. Presence and further development of retinal dysfunction after 3-year follow up in IDDM patients without angiographically documented vasculopathy. Diabetologia. 1994;37:911–916. doi: 10.1007/BF00400947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parisi V, Uccioli L. Visual electrophysiological responses in persons with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2001;17:12–18. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Q, Zemel E, Miller B, Perlman I. Early retinal damage in experimental diabetes: electroretinographical and morphological observations. Exp Eye Res. 2002;74:615–625. doi: 10.1006/exer.2002.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engerman RL, Kern TS. Retinopathy in animal models of diabetes. Diabetes Metab Rev. 1995;11:109–120. doi: 10.1002/dmr.5610110203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daley ML, Watzke RC, Riddle MC. Early loss of blue-sensitive color vision in patients with type I diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1987;10:777–781. doi: 10.2337/diacare.10.6.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roy MS, Gunkel RD, Podgor MJ. Color vision defects in early diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104:225–228. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050140079024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sokol S, Moskowitz A, Skarf B, Evans R, Molitch M, Senior B. Contrast sensitivity in diabetics with and without background retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103:51–54. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1985.01050010055018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lieth E, Barber AJ, Xu B, Dice C, Ratz MJ, Tanase D, Strother JM. Glial reactivity and impaired glutamate metabolism in short-term experimental diabetic retinopathy. Penn State Retina Research Group. Diabetes. 1998;47:815–820. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.5.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin PM, Roon P, Ells TK, Ganapathy V, Smith SB. Death of retinal neurons in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:3330–3336. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.VanGuilder HD, Brucklacher RM, Patel K, Ellis RW, Freeman WM, Barber AJ. Diabetes downregulates presynaptic proteins and reduces basal synapsin I phosphorylation in rat retina. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kern TS, Miller CM, Du Y, Zheng L, Mohr S, Ball SL, Kim M, Jamison JA, Bingaman DP. Topical administration of nepafenac inhibits diabetes-induced retinal microvascular disease and underlying abnormalities of retinal metabolism and physiology. Diabetes. 2007;56:373–379. doi: 10.2337/db05-1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eldred WD. Nitric oxide in the retina. Functional neuroanatomy of the nitric oxide system. 2000. 111–145.

- 17.Yilmaz G, Esser P, Kociok N, Aydin P, Heimann K. Elevated vitreous nitric oxide levels in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:87–90. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00398-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hattenbach LO, Allers A, Klais C, Koch F, Hecker M. L-Arginine-nitric oxide pathway-related metabolites in the aqueous humor of diabetic patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:213–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blute TA, Mayer B, Eldred WD. Immunocytochemical and histochemical localization of nitric oxide synthase in the turtle retina. Vis Neurosci. 1997;14:717–729. doi: 10.1017/S0952523800012670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eldred WD, Blute TA. Imaging of nitric oxide in the retina. Vision Res. 2005;45:3469–3486. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2005.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giove TJ, Deshpande MM, Eldred WD. Identification of alternate transcripts of neuronal nitric oxide synthase in the mouse retina. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:3134–3142. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giove TJ, Deshpande MM, Gagen CS, Eldred WD. Increased neuronal nitric oxide synthase activity in retinal neurons in early diabetic retinopathy. Mol Vis. 2009;15:2249–2258. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitamura K, Kangawa K, Kawamoto M, Ichiki Y, Nakamura S, Matsuo H, Eto T. Adrenomedullin: a novel hypotensive peptide isolated from human pheochromocytoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;192:553–560. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hinson JP, Kapas S, Smith DM. Adrenomedullin, a multifunctional regulatory peptide. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:138–167. doi: 10.1210/er.21.2.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hay DL, Conner AC, Howitt SG, Smith DM, Poyner DR. The pharmacology of adrenomedullin receptors and their relationship to CGRP receptors. J Mol Neurosci. 2004;22:105–113. doi: 10.1385/JMN:22:1-2:105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu Y, Krukoff TL. Adrenomedullin stimulates nitric oxide release from SK-N-SH human neuroblastoma cells by modulating intracellular calcium mobilization. Endocrinology. 2005;146:2295–2305. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Szokodi I, Kinnunen P, Tavi P, Weckstrom M, Toth M, Ruskoaho H. Evidence for cAMP-independent mechanisms mediating the effects of adrenomedullin, a new inotropic peptide. Circulation. 1998;97:1062–1070. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.11.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang W, Wang L, Yuan M, Ma J, Hui Y. Adrenomedullin affects two signal transduction pathways and the migration in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:1507–1513. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Y, Krukoff TL. Adrenomedullin stimulates nitric oxide production from primary rat hypothalamic neurons: roles of calcium and phosphatases. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:112–120. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.033761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ito S, Fujisawa K, Sakamoto T, Ishibashi T. Elevated adrenomedullin in the vitreous of patients with diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmologica. 2003;217:53–57. doi: 10.1159/000068244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Er H, Doganay S, Ozerol E, Yurekli M. Adrenomedullin and leptin levels in diabetic retinopathy and retinal diseases. Ophthalmologica. 2005;219:107–111. doi: 10.1159/000083270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Udono T, Takahashi K, Takano S, Shibahara S, Tamai M. Elevated adrenomedullin in the vitreous of patients with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128:765–767. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)00247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caliumi C, Balducci S, Petramala L, Cotesta D, Zinnamosca L, Cianci R, Donato D, Vingolo EM, Fallucca F, Letizia C. Plasma levels of adrenomedullin, a vasoactive peptide, in type 2 diabetic patients with and without retinopathy. Minerva Endocrinol. 2007;32:73–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez A, Elsasser TH, Bhathena SJ, Pio R, Buchanan TA, Macri CJ, Cuttitta F. Is adrenomedullin a causal agent in some cases of type 2 diabetes? Peptides. 1999;20:1471–1478. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(99)00158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia-Unzueta MT, Montalban C, Pesquera C, Berrazueta JR, Amado JA. Plasma adrenomedullin levels in type 1 diabetes. Relationship with clinical parameters. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:999–1003. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.6.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taniguchi T, Kawase K, Gu ZB, Kimura M, Okano Y, Kawakami H, Tsuji A, Kitazawa Y. Ocular effects of adrenomedullin. Exp Eye Res. 1999;69:467–474. doi: 10.1006/exer.1999.0737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clementi G, Floriddia ML, Prato A, Marino A, Drago F. Adrenomedullin and ocular inflammation in the rabbit. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;400:321–326. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(00)00376-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheetz MJ, King GL. Molecular understanding of hyperglycemia’s adverse effects for diabetic complications. JAMA. 2002;288:2579–2588. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.20.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shore AC. The microvasculature in type 1 diabetes. Semin Vasc Med. 2002;2:9–20. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-23093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu X, Zhu Q, Xia X, Zhang S, Gu Q, Luo D. Blood-retinal barrier breakdown induced by activation of protein kinase C via vascular endothelial growth factor in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Curr Eye Res. 2004;28:251–256. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.28.4.251.27834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Danis RP, Bingaman DP, Jirousek M, Yang Y. Inhibition of intraocular neovascularization caused by retinal ischemia in pigs by PKCbeta inhibition with LY333531. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:171–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aiello LP, Bursell SE, Clermont A, Duh E, Ishii H, Takagi C, Mori F, Ciulla TA, Ways K, Jirousek M, Smith LE, King GL. Vascular endothelial growth factor-induced retinal permeability is mediated by protein kinase C in vivo and suppressed by an orally effective beta-isoform-selective inhibitor. Diabetes. 1997;46:1473–1480. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.46.9.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aiello LP, Clermont A, Arora V, Davis MD, Sheetz MJ, Bursell SE. Inhibition of PKC beta by oral administration of ruboxistaurin is well tolerated and ameliorates diabetes-induced retinal hemodynamic abnormalities in patients. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:86–92. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Funatsu H, Yamashita H, Ikeda T, Mimura T, Eguchi S, Hori S. Vitreous levels of interleukin-6 and vascular endothelial growth factor are related to diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1690–1696. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00568-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suzuma I, Suzuma K, Ueki K, Hata Y, Feener EP, King GL, Aiello LP. Stretch-induced retinal vascular endothelial growth factor expression is mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and protein kinase C (PKC)-zeta but not by stretch-induced ERK1/2, Akt, Ras, or classical/novel PKC pathways. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:1047–1057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105336200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hayashi M, Shimosawa T, Fujita T. Hyperglycemia increases vascular adrenomedullin expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;258:453–456. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abbracchio MP, Cattabeni F, Giulio AM, Finco C, Paoletti AM, Tenconi B, Gorio A. Early alterations of Gi/Go protein-dependent transductional processes in the retina of diabetic animals. J Neurosci Res. 1991;29:196–200. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490290209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ishimitsu T, Kojima M, Kangawa K, Hino J, Matsuoka H, Kitamura K, Eto T, Matsuo H. Genomic structure of human adrenomedullin gene. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;203:631–639. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsuruda T, Kato J, Kitamura K, Mishima K, Imamura T, Koiwaya Y, Kangawa K, Eto T. Roles of protein kinase C and Ca2 + -dependent signaling in angiotensin II-induced adrenomedullin production in rat cardiac myocytes. J Hypertens. 2001;19:757–763. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200104000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ishii H, Jirousek MR, Koya D, Takagi C, Xia P, Clermont A, Bursell SE, Kern TS, Ballas LM, Heath WF, Stramm LE, Feener EP, King GL. Amelioration of vascular dysfunctions in diabetic rats by an oral PKC beta inhibitor. Science. 1996;272:728–731. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5262.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koya D, Haneda M, Nakagawa H, Isshiki K, Sato H, Maeda S, Sugimoto T, Yasuda H, Kashiwagi A, Ways DK, King GL, Kikkawa R. Amelioration of accelerated diabetic mesangial expansion by treatment with a PKC beta inhibitor in diabetic db/db mice, a rodent model for type 2 diabetes. FASEB J. 2000;14:439–447. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cotter MA, Jack AM, Cameron NE. Effects of the protein kinase C beta inhibitor LY333531 on neural and vascular function in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Clin Sci (Lond) 2002;103:311–321. doi: 10.1042/cs1030311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kelly DJ, Zhang Y, Hepper C, Gow RM, Jaworski K, Kemp BE, Wilkinson-Berka JL, Gilbert RE. Protein kinase C beta inhibition attenuates the progression of experimental diabetic nephropathy in the presence of continued hypertension. Diabetes. 2003;52:512–518. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aiello LP, Davis MD, Girach A, Kles KA, Milton RC, Sheetz MJ, Vignati L, Zhi XE. Effect of ruboxistaurin on visual loss in patients with diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:2221–2230. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aiello LP, Vignati L, Sheetz MJ, Zhi X, Girach A, Davis MD, Wolka AM, Shahri N, Milton RC. Oral protein kinase C beta inhibition using ruboxistaurin: efficacy, safety, and causes of vision loss among 813 patients (1,392 eyes) with diabetic retinopathy in the Protein Kinase C beta Inhibitor-Diabetic Retinopathy Study and the Protein kinase C beta Inhibitor-Diabetic Retinopathy Study 2. Retina 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Sheetz MJ, Aiello LP, Shahri N, Davis MD, Kles KA, Danis RP. Effect of ruboxistaurin (RBX) on visual acuity decline over a 6-year period with cessation and reinstitution of therapy: results of an open-label extension of the Protein Kinase C Diabetic Retinopathy Study 2 (PKC-DRS2) Retina. 2011;31:1053–1059. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181fe545f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davis MD, Sheetz MJ, Aiello LP, Milton RC, Danis RP, Zhi X, Girach A, Jimenez MC, Vignati L. Effect of ruboxistaurin on the visual acuity decline associated with long-standing diabetic macular edema. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:1–4. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barbuch RJ, Campanale K, Hadden CE, Zmijewski M, Yi P, O’Bannon DD, Burkey JL, Kulanthaivel P. In vivo metabolism of [14C]ruboxistaurin in dogs, mice, and rats following oral administration and the structure determination of its metabolites by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry and NMR spectroscopy. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:213–224. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.007401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pong WW, Stouracova R, Frank N, Kraus JP, Eldred WD. Comparative localization of cystathionine beta-synthase and cystathionine gamma-lyase in retina: differences between amphibians and mammals. J Comp Neurol. 2007;505:158–165. doi: 10.1002/cne.21468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jirousek MR, Gillig JR, Gonzalez CM, Heath WF, McDonald JH, III, Neel DA, Rito CJ, Singh U, Stramm LE, Melikian-Badalian A, Baevsky M, Ballas LM, Hall SE, Winneroski LL, Faul MM. (S)-13-[(dimethylamino)methyl]-10,11,14,15-tetrahydro-4,9:16, 21-dimetheno-1H, 13H-dibenzo[e, k]pyrrolo[3,4-h][1,4,13]oxadiazacyclohexadecene-1,3(2H)-d ione (LY333531) and related analogues: isozyme selective inhibitors of protein kinase C beta. J Med Chem. 1996;39:2664–2671. doi: 10.1021/jm950588y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miranda KM, Espey MG, Wink DA. A rapid, simple spectrophotometric method for simultaneous detection of nitrate and nitrite. Nitric Oxide. 2001;5:62–71. doi: 10.1006/niox.2000.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Akula JD, Mocko JA, Benador IY, Hansen RM, Favazza TL, Vyhovsky TC, Fulton AB. The neurovascular relation in oxygen-induced retinopathy. Mol Vis. 2008;14:2499–2508. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Akula JD, Hansen RM, Tzekov R, Favazza TL, Vyhovsky TC, Benador IY, Mocko JA, McGee D, Kubota R, Fulton AB. Visual cycle modulation in neurovascular retinopathy. Exp Eye Res. 2010;91:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hood DC, Birch DG. A computational model of the amplitude and implicit time of the b-wave of the human ERG. Vis Neurosci. 1992;8:107–126. doi: 10.1017/S0952523800009275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lamb TD, Pugh EN., Jr A quantitative account of the activation steps involved in phototransduction in amphibian photoreceptors. J Physiol. 1992;449:719–758. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pugh EN, Jr, Lamb TD. Amplification and kinetics of the activation steps in phototransduction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1141:111–149. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(93)90038-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Robson JG, Frishman LJ. Response linearity and kinetics of the cat retina: the bipolar cell component of the dark-adapted electroretinogram. Vis Neurosci. 1995;12:837–850. doi: 10.1017/S0952523800009408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pugh EN Jr, Falsini B, Lyubarsky AL. The origins of the major rod- and cone-driven components of the rodent electroretinogram and the effect of age and light-rearing history on the magnitude of these components. In: Photostasis and related phenomena. New York: Plenum Press; 1998.

- 70.Wurziger K, Lichtenberger T, Hanitzsch R. On-bipolar cells and depolarising third-order neurons as the origin of the ERG-b-wave in the RCS rat. Vision Res. 2001;41:1091–1101. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6989(01)00026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wachtmeister L. Some aspects of the oscillatory response of the retina. Prog Brain Res. 2001;131:465–474. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(01)31037-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dong CJ, Agey P, Hare WA. Origins of the electroretinogram oscillatory potentials in the rabbit retina. Vis Neurosci. 2004;21:533–543. doi: 10.1017/S0952523804214043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Akula JD, Mocko JA, Moskowitz A, Hansen RM, Fulton AB. The oscillatory potentials of the dark-adapted electroretinogram in retinopathy of prematurity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:5788–5797. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shirao Y, Kawasaki K. Electrical responses from diabetic retina. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1998;17:59–76. doi: 10.1016/S1350-9462(97)00005-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bresnick GH, Palta M. Oscillatory potential amplitudes. Relation to severity of diabetic retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:929–933. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1987.01060070065030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gardner TW, Antonetti DA, Barber AJ, LaNoue KF, Levison SW. Diabetic retinopathy: more than meets the eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47(Suppl 2):S253–S262. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6257(02)00387-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fletcher EL, Phipps JA, Ward MM, Puthussery T, Wilkinson-Berka JL. Neuronal and glial cell abnormality as predictors of progression of diabetic retinopathy. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:2699–2712. doi: 10.2174/138161207781662920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kern TS, Barber AJ. Retinal ganglion cells in diabetes. J Physiol. 2008;586:4401–4408. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.156695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Barber AJ, Schuller K, Bridi MA, Bronson SK. Visual acuity and contrast sensitivity are reduced in the Ins2Akita diabetic mouse. ARVO Annual Meeting. 2010.

- 80.Lecleire-Collet A, Audo I, Aout M, Girmens JF, Sofroni R, Erginay A, Gargasson JF, Mohand-Said S, Meas T, Guillausseau PJ, Vicaut E, Paques M, Massin P. Evaluation of retinal function and flicker light-induced retinal vascular response in normotensive patients with diabetes without retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:2861–2867. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dijk HW, Kok PH, Garvin M, Sonka M, DeVries JH, Michels RP, Velthoven ME, Schlingemann RO, Verbraak FD, Abramoff MD. Selective loss of inner retinal layer thickness in type 1 diabetic patients with minimal diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:3404–3409. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dijk HW, Verbraak FD, Kok PH, Garvin MK, Sonka M, Lee K, DeVries JH, Michels RP, Velthoven ME, Schlingemann RO, Abramoff MD. Decreased retinal ganglion cell layer thickness in patients with type 1 diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:3660–3665. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-5041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hayashi Y, Nishio M, Naito Y, Yokokura H, Nimura Y, Hidaka H, Watanabe Y. Regulation of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase by calmodulin kinases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:20597–20602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.29.20597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rameau GA, Chiu LY, Ziff EB. Bidirectional regulation of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase phosphorylation at serine 847 by the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:14307–14314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Song T, Hatano N, Horii M, Tokumitsu H, Yamaguchi F, Tokuda M, Watanabe Y. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I inhibits neuronal nitric-oxide synthase activity through serine 741 phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 2004;570:133–137. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.05.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Song T, Hatano N, Kume K, Sugimoto K, Yamaguchi F, Tokuda M, Watanabe Y. Inhibition of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase by phosphorylation at threonine1296 in NG108-15 neuronal cells. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:5658–5662. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen ZP, McConell GK, Michell BJ, Snow RJ, Canny BJ, Kemp BE. AMPK signaling in contracting human skeletal muscle: acetyl-CoA carboxylase and NO synthase phosphorylation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;279:E1202–E1206. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.279.5.E1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Komeima K, Hayashi Y, Naito Y, Watanabe Y. Inhibition of neuronal nitric-oxide synthase by calcium/ calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIalpha through Ser847 phosphorylation in NG108-15 neuronal cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28139–28143. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003198200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bredt DS, Ferris CD, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide synthase regulatory sites. Phosphorylation by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase, protein kinase C, and calcium/calmodulin protein kinase; identification of flavin and calmodulin binding sites. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:10976–10981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rameau GA, Chiu LY, Ziff EB. NMDA receptor regulation of nNOS phosphorylation and induction of neuron death. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:1123–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kikuchi M, Kashii S, Mandai M, Yasuyoshi H, Honda Y, Kaneda K, Akaike A. Protective effects of FK506 against glutamate-induced neurotoxicity in retinal cell culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:1227–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dotsch J, Schoof E, Schocklmann HO, Brune B, Knerr I, Repp R, Rascher W. Nitric oxide increases adrenomedullin receptor function in rat mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2002;61:1707–1713. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dotsch J, Schoof E, Hanze J, Dittrich K, Opherk P, Dumke K, Rascher W. Nitric oxide stimulates adrenomedullin secretion and gene expression in endothelial cells. Pharmacology. 2002;64:135–139. doi: 10.1159/000056162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ribatti D, Nico B, Spinazzi R, Vacca A, Nussdorfer GG. The role of adrenomedullin in angiogenesis. Peptides. 2005;26:1670–1675. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Noda K, Ishida S, Inoue M, Obata K, Oguchi Y, Okada Y, Ikeda E. Production and activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:2163–2170. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mohammad G, Kowluru RA. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 in the development of diabetic retinopathy and mitochondrial dysfunction. Lab Invest. 2010;90:1365–1372. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Martinez A, Oh HR, Unsworth EJ, Bregonzio C, Saavedra JM, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Cuttitta F. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 cleavage of adrenomedullin produces a vasoconstrictor out of a vasodilator. Biochem J. 2004;383:413–418. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kowluru RA. Diabetes-induced elevations in retinal oxidative stress, protein kinase C and nitric oxide are interrelated. Acta Diabetol. 2001;38:179–185. doi: 10.1007/s592-001-8076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gardner TW, Antonetti DA. Ruboxistaurin for diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:2135–2136. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Shiba T, Inoguchi T, Sportsman JR, Heath WF, Bursell S, King GL. Correlation of diacylglycerol level and protein kinase C activity in rat retina to retinal circulation. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:E783–E793. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1993.265.5.E783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Araujo IM, Carvalho CM. Role of nitric oxide and calpain activation in neuronal death and survival. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2005;4:319–324. doi: 10.2174/1568007054546126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Volbracht C, Chua BT, Ng CP, Bahr BA, Hong W, Li P. The critical role of calpain versus caspase activation in excitotoxic injury induced by nitric oxide. J Neurochem. 2005;93:1280–1292. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]