Abstract

Brain stimulation techniques have evolved in the last few decades with more novel methods capable of painless, noninvasive brain stimulation. While the number of clinical trials employing noninvasive brain stimulation continues to increase in a variety of medication-resistant neurological and psychiatric diseases, studies evaluating their diagnostic and therapeutic potential in traumatic brain injury (TBI) are largely lacking. This review introduces different techniques of noninvasive brain stimulation, which may find potential use in TBI. We cover transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), low-level laser therapy (LLLT) and transcranial doppler sonography (TCD) techniques. We provide a brief overview of studies to date, discuss possible mechanisms of action, and raise a number of considerations when thinking about translating these methods to clinical use.

Keywords: Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), Diffuse Axonal Injury (DAI), Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS), Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS), Low-Level Laser Therapy (LLLT), Transcranial Doppler Sonography (TCD)

1. INTRODUCTION

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) occurs across the lifespan, but is most common among active and otherwise healthy teenagers and young adults.1,2 The consequences are staggering, and include a broad spectrum of cognitive, behavioral, and sensorimotor disabilities which dramatically reduce the quality of life, necessitate long-term care and create a worldwide public health problem.3 Standard rehabilitation approaches that target functional recovery following focal brain damage have limited utility in severe TBI. The characteristic dual nature of injury, which combines diffuse and focal damage, makes anatomo-clinical correlations exceptionally challenging and limits the success of conventional rehabilitation.4 Thus, there is an urgent need for improved therapeutic strategies to promote optimal functional recovery in TBI.

The neuropathophysiology of TBI is complex and involves many pathways that are incompletely characterized but may offer therapeutic targets. Unguided approaches to therapeutic innovation that do not consider known pathophysiology are unlikely to succeed. Therefore, it is worth reviewing key biochemical and molecular processes that are thought to play critical roles in the neuropathophysiology of TBI and might offer valuable targets for therapeutic intervention.

2. NEUROPATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF TBI: DIFFERENT POTENTIAL TARGETS AT DIFFERENT TIME-POINTS FOLLOWING INSULT

The detrimental effects of TBI evolve as a result of primary physical trauma and secondary biochemical/physiologic perturbations, both of which lead to neuronal loss and diffuse axonal injury (DAI).5

The impact of the primary physical trauma depends on the intensity and the temporal and spatial distributions of the insult. Insults of greater intensity and duration tend to result in neural necrosis while milder impacts preferentially induce apoptosis.6 Diffuse damage is most likely with inertial loading. However, even damage once deemed focal may actually be quite diffuse as demonstrated with stains specific for both neuronal axons and nerve terminals.7

Secondary biochemical perturbations involve several processes. First, excessive glutamate accumulation leads to NMDA-mediated glutamatergic excitotoxicity and neurodegeneration.8-11 Cerebral ischemia leads to a lack of oxygen and glucose delivery to neurons, resulting in reduced ATP and elevated lactate levels indicative of metabolic stress. Energy substrate deprivation impairs the ability to maintain basal ionic gradients. This leads to enhanced voltage and NMDA-dependant depolarizing postsynaptic potentials, causing neuronal and glial depolarization. NMDA receptor activation results in intracellular calcium overload, stimulating inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and apoptosis.5,12-15 Elevated intracellular calcium further exacerbates and propagates metabolic stress via cortical spreading depression.5 In addition, high calcium levels may trigger calcium-induced calpain proteolysis of cytoskeletal proteins and subsequent cellular collapse5,6. Cellular destruction may also result from enhanced oxidative stress due to mitochondrial dysfunction and increased neuronal and inducible nitric oxide synthase (nNOS, iNOS), enhancing production of free radicals and lipid peroxidation.5,6,16-18 Therefore, suppression of the hyperexcitability cascade may minimize or prevent some of the disabling consequences of TBI and pose an exciting potential therapeutic target. However, excessive blockade may prevent acutely damaging mediators from later assisting in active recovery (i.e. NMDA receptor blockers, matrix metalloproteinase blockers, c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway inhibition), ultimately resulting in therapeutic failure.19 Methods aimed at modifying TBI-triggered excitotoxicity that are currently in trials, including hypothermia and pharmacologic glutamate receptor antagonism5, remain unproven, are practically complex to implement, or affect the brain globally with potentially toxic side-effects.

In addition to modulation of glutamate levels, there is also evidence for the involvement of GABA, the principal inhibitory neurotransmitter in the cerebral cortex, in response to TBI. In the acute stage, transplantation of GABAergic neurons can induce recovery of sensorimotor function in rats23 while GABAA agonists can increase survival and cognitive functioning.24 GABA levels were found to be elevated in MR spectroscopy performed at 24-48 hours post-TBI25 and in ventricular CSF in patients with severe TBI.26 Although increasing inhibitory function via GABA receptors seems beneficial during the acute post-injury period27, this increase may continue beyond the acute stage and hinder recovery. In rats, TBI induces long-lasting working memory deficits associated with increased GABA levels for as long as 1-month post-TBI and administration of GABA antagonists restores memory function, suggesting that lasting deficits following TBI are associated with “excess GABA-mediated inhibition”.28 Critically, these deficits do not remain amenable to GABAergic treatment by 4 months post-injury.29 GABAergic terminal loss correlates with recovery following TBI30 and accompanies injury induced reorganization of the cortex.31 Therefore, in the subacute stage when GABAergic activity is excessive and promotes functional disability, increasing neuronal excitability may help counter the GABAergic tone to allow potentiation of previously unexpressed connections.31

Beyond the cascade of neurochemical responses, the nervous system reorganizes in response to injury.32 Rewiring of neural connections appears to make it possible for one part of the brain to assume the functions of a disabled region. Neuroplasticity following TBI likely includes the unmasking of previously latent synapses, synaptic alteration of receptor sensitivity, dendritic growth, collateral sprouting of new synaptic connections and arborization from neighboring undamaged neural elements.33,34 Synaptic loss, disrupting pathways after DAI, may be reestablished by dendritic growth and arborization from neighboring undamaged axons.35,36 More severe DAI, however, may lead to more concentrated and profound damage to critical neural networks.37 In this stage, recovery mechanisms operating through synaptic reorganization may not be adequate, and more complex mechanisms on the network level are likely to intervene. However, the behavioral impact of such plasticity is not necessarily adaptive and may prove to be a dead-end strategy that ultimately limits functional recovery and promotes lasting disability.32

Therefore, promotion of functional recovery following TBI appears to require differential interventions at different time-points following injury (Figure 1). In the acute phase, suppression of glutamatergic activity might be desirable and may minimize neurologic damage and disability. In the subacute phase following TBI, modulation of GABAergic inhibition might be critical to minimize functional impact and promote wellbeing. In more chronic stages, modulation of brain plasticity to suppress functionally maladaptive changes and enhance those resulting in behavioral advantages is critical to counter disability and may be used for rehabilitation of disabling sequelae.

Figure 1.

After injury, compromised energy production elicits a cascade of excitatory neurotransmitters and overactivation of NMDA subclass of glutamate receptors.6 This provokes a massive increase in intracellular calcium concentration, which leads to the attenuation of mitochondrial potential and results in secondary release of calcium from the mitochondrial mass. A number of factors including stress, hemodynamics, intracranial pressure variations can contribute to the insult and disrupt natural recovery and remodeling.20 Axonal sprouting is most robust within days following TBI21 and these factors can cause sprouting fibers to lose direction and connect with the wrong terminals, leading to circuit dysfunction and functional abnormalities5 that likely contribute to long-term disabilities, such as pain, spasticity, seizures, and memory problems. Following the acute stage, the increased levels of GABA may cause excess inhibition hindering recovery. Targeted inputs and a complex environment may help maintain adequate levels of arousal for potentially rescuable circuits and hence, favor functional restoration.22 In the chronic stage, major loss of connectivity leading to lasting dysfunction will require compensatory approaches on the network level and neural plasticity may positively or negatively contribute to recovery. In the long term, cognitive problems, Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease may arise as a consequence of TBI6. Different forms of noninvasive brain stimulation are proposed for these stages in order to reduce disability following TBI; see relevant sections of the text for details.

3. NONINVASIVE BRAIN STIMULATION TECHNIQUES IN THE CONTEXT OF TBI

In the following section we introduce novel noninvasive stimulation methods worth considering in the context of TBI and provide a brief review of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation, Low-Level Laser Therapy, and Transcranial Doppler Sonography techniques.

3. 1. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS)

TMS is based on Faraday’s principle of electromagnetic induction and features the application of rapidly changing magnetic fields to the scalp via a copper wire coil connected to a magnetic stimulator.38 These brief pulsed magnetic fields of 1-4 Tesla pass through the skull and create electric currents in discrete brain regions.39 Applied in single pulses (single-pulse TMS) appropriately delivered in time and space, the currents induced in the brain can be of sufficient magnitude to depolarize a population of neurons and evoke a certain phenomenon. 40 Paired-pulse application of TMS can be used to evaluate intracortical inhibitory/excitatory circuits and cortico-cortical connectivity.41 These TMS measures have proved valuable in understanding the neurophysiologic basis of various neuropsychiatric diseases and can provide useful diagnostic information in conditions with intra- or intercortical excitability abnormalities.42

Repetitive trains of TMS (rTMS) applied to targeted brain regions can suppress or facilitate cortical processes, depending upon stimulation parameters.38,40 In most instances, continuous low frequency (≤1Hz) rTMS decreases the excitability of the underlying cortex while bursts of intermittent high frequency (≥5Hz) rTMS enhance it. Also, a subtype of rTMS, known as Theta Burst Stimulation (TBS), incorporates very short, high frequency (50Hz) trains of stimuli delivered intermittently or continuously at 5Hz.43,44 TBS can induce or decrease excitability when applied in an intermittent (iTBS) or continuous (cTBS) paradigm, respectively. The fact that the modulatory effects of rTMS can outlast the duration of its application has led to the exploration of the technique as a potential treatment modality with promising results in various neuropsychiatric disorders (Figure 2A). The rTMS after-effects are influenced by the magnitude and duration of stimulation, the level of cortical excitability and the state of activity in the targeted brain region.45

Figure 2.

(A) Therapeutic application of rTMS in a patient with depression. (B) tDCS experimental set-up. Note the saline-soaked conductive electrodes on the surface of the scalp and the small, portable size of the stimulation device (hand-held by investigator).

Extensive neurophysiologic and neuroimaging studies in human and animal models are starting to illuminate the neurophysiology underlying rTMS effects. Overall, rTMS of a targeted brain region has been demonstrated to induce modulation distributed across corticosubcortical and corticocortical networks by means of transsynaptic spread, resulting in distant but specific changes in brain activity along functional networks.46-50 Modeling studies can provide essential information on the induced current and field distributions generated in biological tissue during TMS.39 Short-term effects of TMS on brain activity appear to result from changes in neural excitability caused by shifts in the ionic equilibrium surrounding cortical neurons, reafferent feedback from targeted structures, or the storage of charge induced by stimulation. 51 The prolonged after-effects are considered to result from modulation of long-term depression (LTD) and long-term potentiation (LTP) between synaptic connections, modifying neuronal plasticity. Increased expression of immediate early genes and neurotrophic effects have also been discussed as possible mechanisms. Following diffuse damage after TBI, the induction of LTP and LTD may be abnormal due to cellular injury and altered connectivity, which may ultimately account for lasting deficits. Importantly, this plastic potential might be guided using neuromodulatory strategies to improve clinical outcomes of TBI.

TMS-induced side effects primarily include transient headache, local pain, neck pain, toothache, paresthesias, transient hearing changes, transient changes in cognitive/neuropsychological functions and syncope (possible as an epiphenomenon). 52-54 The most serious adverse event related to TMS is induction of a seizure52-57 but this is a rare complication if the stimulation is applied according to the safety guidelines (See section 6 for safety considerations in TBI).

While not yet widely popular in TBI research, TMS appears to be well suited to serve as a diagnostic and prognostic factor in the case of TBI. Online or offline combinations of TMS, EEG and fMRI may assist in understanding the extent of injury and the mechanisms of plasticity underlying functional recovery in TBI. Its neuromodulatory potential in rehabilitation of patients with TBI also remains to be investigated. Importantly, the focality of TMS might be disadvantageous in the acute stage as diffuse damage is frequently a key component of the insult. In the subacute stage, TMS may affect potentially salvageable lesioned circuits dependent on maintaining adequate levels of arousal and avoiding activation of competitor circuits. In order to optimize the therapeutic potential of neuromodulation in promoting functional recovery in the chronic stage, extensions of insights gained from other patient populations can be translated to TBI patients with carefully characterized deficits (Section 5).

3. 2. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS)

tDCS is a noninvasive technique of neuromodulation, which uses low amplitude direct current to alter neuronal firing. While the use of anodal or cathodal direct current polarization to induce changes in the firing rates of neurons was demonstrated in the 1960’s, the technique has received renewed interest in recent years. Nitsche and colleagues investigated the modulatory effects of tDCS on motor cortical excitability and reported that anodal tDCS elicits prolonged increases in the cortical excitability and facilitates underlying regional activity, while cathodal stimulation shows the opposite effects.58,59 The duration of aftereffects outlasts the period of stimulation and largely depends on the duration of tDCS. Furthermore, several consecutive sessions of stimulation result in behavioral effects lasting several weeks, a particularly important feature with respect to cortical plasticity.60,61

The short-term effects of tDCS are likely elicited by a non-synaptic mechanism and result from depolarization of neuronal resting membrane, presumably caused by alterations in transmembrane proteins and electrolysis-related changes in hydrogen ions.58,62-64 Long-term effects are believed to depend on changes in NMDA receptor activation as well as neuronal hyper- and depolarization, and thus, may share similarities with LTP and LTD.65 Indeed, we have directly relevant pilot data demonstrating modulation of synaptic LTP by tDCS in a murine model (Rotenberg et al., unpublished data). In addition, a functional neuroimaging study investigating the effects of tDCS, demonstrated persistent metabolic changes in oxygen metabolism consistent with electrode location and neural network modulation. Therefore, tDCS has the potential to modify spontaneous activity and synaptic strengthening, and to modulate neurotransmitter-dependent plasticity on the network level.66

The procedure consists of a 1-2mA current applied through 35 cm2 pad electrodes placed on the scalp (Figure 2B). The low-level current flows from the positive electrode, anode, to the negative electrode, cathode, and increases the regional activity by the anode while decreasing the activity underneath the cathode. The process may be referred to as cathodal or anodal tDCS depending on the electrode placed over the region being modulated.67 Large electrode size limits the focality of stimulation, but is preferential to avoid high current densities at the skin which may cause local irritation or even burning.64 It is also possible to apply the second electrode to an extracranial position (e.g. shoulder) instead of the scalp. While providing greater specificity of stimulation effects on the brain, this application may lead to quite different effects at the primary site; modeling should be considered for such novel electrode arrangements to better predict and understand the current distribution.68 Future developments (e.g. employing carrier frequencies) may help to bridge the scalp and skull and deliver the stimulating current to the brain more reliably. Even in its present form, the density of stimulation is low enough that subjects only perceive the stimulus during the rapid change in current at the onset and offset of the stimulation. Thus, from a practical point of view, it is easy to sham stimulate subjects by slowly ramping down the intensity after switch on, and ramping up before switch off. This method of sham stimulation has proven to be reliable with minimal discomfort.69

tDCS has been shown to enhance motor learning in healthy subjects70 and stroke patients71,72, language in normal subjects73 and patients with aphasia74, and verbal fluency75 and verbal working memory76 in healthy subjects and patients with early Alzheimer’s disease77. Furthermore, modulation on the network level allows for modulation of behaviors such as decision-making or social interactions78,79, and has been shown to have translational clinical applications in cases of impulsive behavior, addiction and depression.80 Therefore, tDCS has the potential to improve learning by modification of spontaneous activity and synaptic strengthening, and to modulate neurotransmitter-dependent plasticity on the network level. 81

Several studies of the safety of tDCS have concluded that it is a painless technique for electrically stimulating the brain with almost no risk of harm.64,82 The most frequent adverse effects include moderate fatigue (35%), mild headache (11.8%), nausea (2.9%) and temporary mild tingling sensation, itchiness and/or redness in the area of stimulation. While the risks are rather minimal, tDCS may also result in temporary side effects such as dizziness, disorientation, or confusion.

Overall, tDCS features a highly portable, safe, noninvasive means to modulate cortical excitability with reasonable topographic resolution and reliable experimental blinding. It can focally suppress or enhance neuronal firing following TBI, depending on the size and location of the applied electrodes, and thus may offer a promising method to minimize the damage and promote functional recovery. Cathodal tDCS may be employed to suppress the acute glutamatergic hyperexcitability following TBI. In the subacute stage, when GABAergic activity is excessive and conditions neurologic, cognitive and functional disability, anodal tDCS may increase excitability to counter these aberrant GABAergic effects. In the chronic stage, brain stimulation coupled to rehabilitation may enhance behavioral recovery, learning of new skills and cortical plasticity (Section 5). In this stage, the relative ease of use and portability of tDCS may enable modulation of plasticity via concomitant behavioral interventions such as cognitive behavioral, occupational and physical therapy.83-86

3. 3. Low–Level Laser Therapy (LLLT)

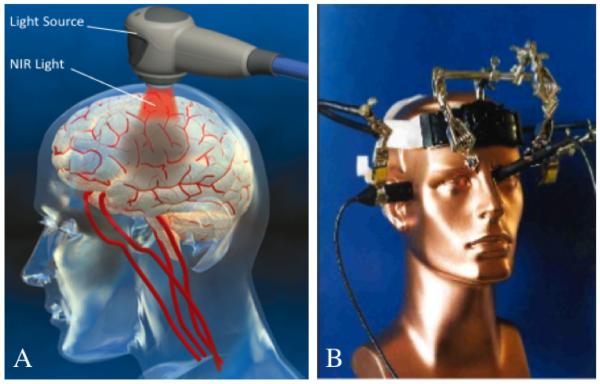

LLLT, or photobiostimulation, is a novel method of noninvasive neural stimulation that, at specific wavelengths, can safely penetrate into the brain (Figure 3A).87-90 LLLT is thought to promote cellular survival in times of reduced energy substrate through interactions with cytochrome c oxidase to enhance oxidative phosphorylation. This interaction, believed to involve the photodissociation of nitric oxide from cytochrome c oxidase, ultimately improves mitochondrial function and increases ATP.91-96

Figure 3.

(A) Illustration of light source emitting near-infrared light capable of penetrating biological tissues and therefore, capable of reaching the cerebral cortex (image courtesy of PhotoThera, Inc.). Caution: the above demonstrates the use of an investigational device – limited by Federal law to investigational use. (B) Multidirectional ultrasound device used for transcranial and/or transorbital Doppler sonography (with permission from the publisher and authors101). This device is no different than those currently used in the clinic to assess cerebral blood flow. Hence, the devices for diagnostic transcranial ultrasound may someday be a commonly used therapeutic tool to prevent or minimize ischemic neuronal injury, such as that which may result secondary to TBI.

LLLT has been shown to accelerate wound healing, reduce neurological deficit following stroke, and improve outcome in spinal cord injury.88,89,91,95,97 A study assessing the effects of LLLT following transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo) in rats demonstrated that 10 minutes of LLLT could reduce levels of neurotoxic nitric oxide synthase, eNOS, nNOS, and iNOS. Treatments also significantly increased neuroprotective TGF-β1.95 In addition, LLLT functions as a free radical scavenger, demonstrating a time-dependent decrease in the levels of reactive oxygen species while reducing expression of phospholipase A2.98,99 Beyond LLLT’s anti-inflammatory role, it may also promote neurogenesis. Oron et al. tested LLLT treatment 24 hours after permanent MCAo in rats and found significant functional improvements and increased newly formed neuronal cells in the injured hemisphere.89

Recently, LLLT was used for the first time in a rodent TBI model. LLLT was administered to mice 4 hours after injury with subsequent monitoring for 28 days using the functional Neurological Severity Score (NSS) in addition to lesion histology. LLLT-treated rats showed significantly reduced NSS from 5 days to 28 days post TBI with reduced lesion volume.89 Although LLLT is new to TBI research, it is currently being used in human stroke trials as an acute neuroprotective therapy.88,100 Given these early successes in stroke research and the unique properties of LLLT, its therapeutic application in TBI is a viable prospect.

3. 4. Transcranial Doppler Sonography (TCD)

Focal ultrasound, or TCD, is not new to the field of neurological diagnostics, but the novel way in which it can be used to interact with neurobiological systems may expand the applications of this tool (Figure 3B). In the setting of TBI, TCD is used in the acute assessment of cerebral ischemia.102 Cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP), defined as the difference between the mean arterial blood pressure and intracranial pressure (ICP), has emerged as the modifiable target of intensive care of TBI patients. However, CPP is complicated by the necessity of measuring ICP, an unfavorably invasive procedure.102 Recent work demonstrated that the pulsatility index (PI; the difference in systolic and diastolic flow velocities divided by mean flow velocity) strongly correlates with ICP and CPP and may therefore serve as a noninvasive surrogate for these measures.103,104 TCD allows one to estimate intravascular flow noninvasively using the PI. A study in patients with mild to moderate TBI showed that PI measured at time of admission was associated with neurological outcomes one week later; higher PIs associated with greater neurological deterioration as assessed by the GCS.104,105 Thus, TCD is proving to be a powerful diagnostic and prognostic tool in TBI.

More recent advances in our understanding of TCD have lead to exciting possible therapeutic roles in TBI where clot formation may result from primary injury. One application is sonothrombolysis; a technique of focal TCD applied at diagnostic frequencies alone or in combination with standard thrombolytic therapy (tPA). A recent study assessed the thrombolytic capacity of TCD using conventional transcranial color-coded sonography applied to the MCA-M1 for 1 hour in stroke patients ineligible for tPA; TCD could achieve faster recanalization rates and improved short-term outcomes in acute stroke patients.106 In vitro studies have shown that US applied in combination with tPA can accelerate clot dissolution by 2.2- to 5.5-fold in direct proportion to the concentration of tPA.107,108 Subsequently, a multicenter collaboration tested the utility of the tPA-TCD combination in the CLOTBUST trial. They found that 83% of patients achieved recanalization with the tPA-TCD combination compared to 50% with tPA alone. Improved efficacy with tPA-TCD is believed to result from TCD-mediated mechanical disturbance at the plasma-thrombi interface, increasing exposure of thrombi sites upon which tPA can act.109 New developments in the area of therapeutic US are investigating the addition of microbubbles (air-filled microspheres) which increase focality of treatments and allow more conservative TCD settings. TCD interacts with the microbubbles to promote mechanical disruption of clots independent of tPA and may cause size expansion, oscillations, or complete disruption of the microbubbles, transmitting mechanical energy at the clot-residual flow interface to improve thrombolysis.109,110 Thus, in TBI, where thrombosis may further complicate clinical outcome, sonothrombolysis may provide a viable therapeutic option.

TCD may also have the potential to promote neuroprotection during acute TBI by increasing the local bioavailability of neuroprotective agents. TCD has been shown to transiently (i.e. hours) enhance blood brain barrier (BBB) permeability without adverse cellular effects. The mechanism is believed to be a process of stable cavitation, in which low acoustic energy causes administered microbubbles to oscillate and expand creating small eddy currents in the surrounding plasma. These currents provide shear stress on cells and large molecules to increase BBB transcellular and paracellular transport.110-112 Thus, TCD may increase the applicability of novel neuroprotective agents by allowing focal pharmacokinetic optimization.

Further studies have alluded to the potential of TCD as a direct means of neuroprotection. A recent study showed that low-intensity low-frequency US (LILFU) is capable of remote stimulation of mouse hippocampal slice and whole brain preparations. LILFU was shown to activate voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels triggering synaptic transmission. Additionally, stimulation of CA3 Schaffer collaterals was shown to exhibit the same kinetics and amplitudes of traditional monopolar electrical stimulation while prolonged periods of exposure (36-48 hours) did not produce aberrant membrane changes. Previous work by Rinaldi et al. demonstrated that stimulation of hippocampal slices could suppress evoked potentials in CA1 pyramidal neurons.113-115 In addition, high frequency US has been shown to elicit cortical spreading depression, a phenomenon of generalized cortical depolarization, loss of ionic gradients, and subsequent cessation of bioelectrical activity without damage.112 In the setting of TBI, these attributes of TCD may allow for suppression of neuronal activity in the acute energy deficient phase and facilitation in the subacute phase of active recovery, strengthening our therapeutic capacity against TBI.

4. DIAGNOSTIC APPLICATIONS OF NONINVASIVE BRAIN STIMULATION IN TBI

Below, we review the current diagnostic evidence from TMS studies, which may offer potential neurophysiologic markers indicative of functional recovery in TBI. The monitoring of neurophysiologic impact of TMS using EEG and functional neuroimaging techniques may allow the systematic study of functional connectivity and brain-behavior relations along large-scale neural networks.116 An overview of published TMS studies on motor cortical excitability in TBI is provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Key features of the noninvasive brain stimulation techniques

| Technique | Parameter | Neurophysiologic Effect |

Functional Effect (Investigational) |

Presumed Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TMS | high frequency (10-20 Hz), intermittent theta burst |

enhance cortical excitability |

improve functional outcome and reduce disability, reduce depressive symptoms, improve motor, cognitive and behavioral functions |

changes in neural excitability, modulation of synaptic LTP; may reduce excess GABA-mediated inhibition, promote compensatory plasticity, inhibit maladaptive plasticity in TBI |

| low frequency (≤1 Hz), continuous theta burst |

reduce cortical excitability |

improve functional outcome and reduce disability, reduce depressive symptoms, improve motor, cognitive and behavioral functions |

changes in neural excitability, modulation of synaptic LTD; may decrease glutamatergic excitotoxicity, promote compensatory plasticity, inhibit maladaptive plasticity in TBI |

|

| tDCS | anodal stimulation (1-2 mA) |

enhance cortical excitability |

improve functional outcome and reduce disability, reduce depressive symptoms, improve motor, cognitive and behavioral functions |

depolarization of neuronal resting membrane, changes in NMDA receptor activation, modulation of synaptic LTP; may reduce excess GABA-mediated inhibition, promote compensatory plasticity, inhibit maladaptive plasticity in TBI |

| cathodal stimulation (1-2 mA) |

reduce cortical excitability |

improve functional outcome and reduce disability, reduce depressive symptoms, improve motor, cognitive and behavioral functions |

depolarization of neuronal resting membrane, changes in NMDA receptor activation, modulation of synaptic LTD; may decrease glutamatergic excitotoxicity, promote compensatory plasticity, inhibit maladaptive plasticity in TBI |

|

| LLLT | 660-808nm | unknown | reduce neurological deficit, improve functional outcome |

enhance oxidative phosphorylation, improve mitochondrial function, increase neuroprotective TGF-β1, reduce phospholipase A2 and reactive oxygen species, promote neurogenesis |

| TCD | diagnostic frequency (1-2.2Mhz) |

unknown | improve short-term outcomes; faster recanalization rates; higher local bioavailability of neuroprotective agents |

mechanical disturbance at the plasma- thrombi interface, mechanical enhancement of BBB permeability |

| low frequency (0.44-0.67Mhz) |

unknown | neuroprotection | activate voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels |

|

| high frequency (4.89Mhz) |

elicit cortical spreading depression and subsequent cessation of bioelectrical activity |

neuroprotection | reduction in ionic gradients |

Abbreviations: TBI: traumatic brain injury, TMS: transcranial magnetic stimulation, tDCS: transcranial direct current stimulation, LLLT: low-level laser therapy, TCD: transcranial doppler sonography, LTP: long-term potentiation, LTD: long-term depression, NMDA: N-Methyl-D-aspartate, GABA: γ-aminobutyric acid, TGF-β1: transforming growth factor beta 1, BBB: Blood-brain barrier

4.1. Cortical Excitability

Evidence from a limited number of studies suggests that cortical excitability in TBI is different in early and late stages of injury. Chistyakov et al. reported increased motor threshold levels (MT) and motor evoked potential (MEP) variability, prolonged central motor conduction time (CMCT) and decreased MEP/M wave ratio in mild to moderate TBI patients as early as 2 weeks after the head trauma.117,118 However, they observed that these alterations returned to normal levels within 3 months.118

A number of investigations conducted in chronic TBI patients with preserved normal motor function did not report significant differences for MEP parameters.34,119-124 However, higher MT levels, decreased MEP area, MEP variability and input-output curves were demonstrated when patients had clinically evident motor dysfunction.124,125 Moreover, alterations in the MEP parameters were more pronounced in those with severe DAI, highlighting the key influence of DAI severity on cortical excitability together with the clinical motor dysfunction (Figure 4).124

Figure 4.

MEP of (A) a patient with DAI following recovery, revealing increased duration and number of turns indicative of temporal dispersion (B) a control subject (slightly modified from 34 with permission from IOS press). Superimposed MEPs demonstrate significantly decreased variability in (C) a patient with severe DAI and clinical motor dysfunction, when compared with (D) a control subject (slightly modified from124 with permission from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. publishers). Primary motor cortex activation by hand movements of (E) a patient with DAI following recovery, (F) a control subject (slightly modified from 34 with permission from IOS press). The evident mesial frontal activation in the supplementary motor area of the patient likely represents recruitment of secondary motor areas resulting from reduced capacity of primary motor regions. DTI fiber tractography of hand motor tract in (G) a patient with DAI due to severe TBI, 18 months after trauma and (H) a control subject (modified from132 with permission from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. publishers). Circles show the region of interests (ROI) for the FA measurements of (I) the same patient and (J) control subject (modified from 132 with permission from Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. publishers). FA values were significantly lower in patients compared with controls and correlated with higher motor thresholds, presumably resulting from direct axonal damage due to DAI.

4.2. Cortical inhibition

Silent period (SP), a parameter reflecting intracortical inhibitory mechanisms, has been investigated in a variety of patients with TBI. De Beaumont et al. reported longer SP durations in a group of athletes who had experienced multiple concussions.122 Notably, the athletes with multiple concussions had sustained more severe concussions. The SP was significantly prolonged in such athletes but not in those with a single concussive episode. In a second study, they reported that prolongation of the SP persisted up to 40 years post-concussion and correlated with the level of bradykinesia in a group of former athletes.126

Chistyakov and colleagues reported a significantly longer SP in mild to moderate TBI patients when measured only at a TMS intensity of 130% of motor threshold but not at lower intensities, in contrast to MEP findings.127 The authors concluded that the mechanisms related to the MEP and SP generation might be separately affected in TBI. Recently, Bernabeu et al. reported no significant changes in SP in patients with severe TBI, while significant alterations in the MEP parameters were present.124 These studies support the evidence that excitatory and inhibitory responses probably demonstrate distinct aberrations following TBI and that the number of traumatic insults may be more critical than the severity of trauma for SP abnormalities. Further comprehensive evaluations seem requisite for clarification of intracortical inhibitiory mechanisms following TBI.

4.3. Paired-pulse studies and connectivity measures

Three studies employed short-interval paired-pulse TMS to assess intracortical facilitation and inhibition, and reported no significant differences in patients with mild TBI.119,120,122 Takeuchi and colleagues121 investigated whether ipsilateral silent period durations (iSP, a measure of interhemispheric connectivity that results from transcallosal modulation of activity in the unstimulated hemisphere) could detect a functional abnormality in the corpus callosum of TBI patients and reported significantly shorter iSP in patients with DAI.

4.4. TMS, EEG and functional neuroimaging

Using TMS, EEG and PET, Crossley and colleagues investigated the restoration of functional integrity in an old adult who suffered from severe TBI.128 TMS assessment at 12 months revealed a remarkable increase in MEP amplitudes from those recorded at 4 weeks. 18-FDG PET suggested a general increase in the metabolic rate and showed a regression in the global reduction over the year. The EEG at 4 weeks showed symmetrical slow activity with a predominance of theta frequencies while background activity at 12 months was mostly restored, consistent with the recovery of neural integrity.

Jang and colleagues assessed motor recovery mechanisms in DAI using fMRI and TMS.34 Eight patients with persistent motor weakness for >4 weeks post-TBI were tested after achieving stable motor recovery (mean = 6 months). All patients but one had complete motor recovery. A hand grasp release fMRI paradigm revealed comparable activations in contralateral primary sensorimotor cortices of normal subjects and patients during affected hand movements. MEPs were not different from controls for motor threshold or amplitude, however, duration, mean latency and turns were significantly increased (Figure 4). The authors concluded that the MEP findings were likely to reflect comparable numbers of axonal fibers in the corticospinal tracts in the patient group who exhibited good recovery, and the heterogeneous characteristics of the tract were attributed to axons in the recovery process.

The combined use of TMS and fMRI may help elucidate the extent of neuropathology in severe TBI. Barba et al.125 reported a patient who presented with left hemiparesis in the absence of any detectable lesions affecting the right motor areas. TMS assessments revealed a notably higher motor threshold on the right while latency, amplitude and interhemispheric interactions were normal. Motor mapping via TMS showed reduced cortical representation and a rostral shift on the right hemisphere. Conventional fMRI did not show activations in right motor areas during a motor task paradigm whereas quantitative fMRI detected reduced activation comprising a lower number of voxels. The authors suggested that integrated investigations combining multimodal techniques should be of consideration to better clarify the relation between brain injury and clinical outcome in TBI.

4.5. TMS and Diffusion Tensor Imaging (DTI)

DTI is a novel imaging technique for noninvasive in vivo visualization of white matter tracts in the brain.129,130 The degree of anisotropy (fractional anisotropy, FA) changes as a function of the degree of fiber tract organization, i.e. a reduction in FA values typically indicates histological abnormality.131 Yasokawa and colleagues hypothesized that the FA values could indicate the presence of MEPs and correlate with higher MT in patients with chronic DAI due to severe TBI.132 Indeed, they found significantly lower FA levels in the absence of MEP; lower FA levels also correlated with higher MT (Figure 4). These results provide a correlation between the neurophysiological motor dysfunction and the level of organization in the corticospinal tract following the DAI as detected by DTI.

5. POTENTIAL THERAPEUTIC APPLICATIONS OF NONINVASIVE BRAIN STIMULATION ACCORDING TO FUNCTIONAL CONSEQUENCES OF TBI

Here we propose future targets of intervention defined by post-TBI behavioral symptomatology rather than diagnostic categories. The selection of these functions and circuits is based on their very common and debilitating alterations following TBI and builds on insight and methodologies developed over the past decade. Given the enormous heterogeneity of the injury, implementation of individually tailored approaches using EEG- and fMRI-guided TMS to modulate activity may be considered to maximize the clinical outcome in TBI.

5.1. Hand motor function

Hand motor dysfunction following brain damage can be improved via direct enhancement of the perilesional activity in the affected primary motor cortex or the premotor cortex in the precentral gyrus using high frequency rTMS or anodal TDCS.61,133 The alternative approach aims to decrease the excessive activation of unaffected motor cortex using low frequency rTMS or cathodal TDCS to modify the imbalance in transcallosal motor activity, which results from the loss of inhibitory projections from the damaged area and decreased use of the affected hand. Behavioral gains from rTMS/tDCS protocols may be maximized when brain stimulation is coupled with carefully designed occupational/physical therapy.83-86 In a pilot study, tDCS has been reported to enhance the effects of upper extremity robotic motor training in TBI patients with no skull defects.134

5.2. Mood

Modulation of dysfunctional prefrontal cortico-subcortical networks via bilateral frontal tDCS, high-frequency rTMS to the left or low-frequency rTMS to the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) results in clinically significant antidepressant effects.135,136 In the last decade, several multicenter studies have demonstrated safety and efficacy of rTMS in treatment of major depressive disorder137-139, and TMS has recently gained FDA approval for medically refractory depression. Accordingly, enhancing left DLPFC and/or inhibiting right DLPFC could be tested for post-TBI depression for reestablishment of balance in malfunctioning bihemispheric neural circuits. However, it should be noted that previously tested psychiatric populations had no comorbid brain injury, making the potential for demonstrating a positive benefit-to-risk ratio significantly better.

5.3. Visuo-spatial functions

Transient inhibition of the contralesional parietal region using rTMS has been reported to improve visuospatial neglect.140,141 The same paradigm might be translated to patients with neglect due to TBI.

5.4. Language

Left frontotemporal cathodal tDCS and 1 Hz rTMS to right BA 45 has been shown to improve naming in nonfluent aphasia patients.74,142,143 These strategies, in combination with speech therapies, may be of benefit in post-traumatic expressive aphasia.

5.5. Decision-making, working memory and executive functions

Riskier decision-making has been reported following rTMS-induced virtual lesions of right DLPFC.144 Consequently, it seems plausible that increasing right DLPFC activity using high frequency rTMS, or neuromodulation of the DLPFC bilaterally via tDCS, may diminish decision-making impairments following TBI.78,144 Also, enhancing right or left dorsolateral prefrontal cortices may prove effective for improving working memory and/or executive dysfunctions.76, 145-148

5.6. Spasticity

It has been reported that high frequency rTMS (5Hz) to primary motor cortex increases cortical excitability as well as the excitability of spinal motor neurons to Ia afferent inhibitory input, resulting in improvements in clinical spasticity.149-153 Accordingly, post-TBI spasticity may benefit from this approach.

5.7. Pain

Modulating sensorimotor cortical activity via TMS or tDCS can suppress pain of central origin154,155. This potential might be explored for relief of chronic pain subsequent to trauma.

5.8. Gait

Repeated sessions of rTMS have been proposed as a preventive treatment for limb disuse following brain injury.156 Stimulating the leg motor cortex using high frequency rTMS may enhance gait rehabilitation in combination with gait therapy following TBI. Recently, tDCS has been reported to enhance fine motor control of the paretic ankle and improve hemiparetic gait patterns. 157 In this context, one might envision coupling brain stimulation approaches with robot-assisted gait training.

It should, however, be underlined that the areas proposed here as intervention targets are based on a theoretical framework, as our understanding of brain stimulation mechanisms in TBI is yet very limited. While this framework renders noninvasive brain stimulation an attractive approach to enhance cognitive and motor functions in TBI survivors, the significant difficulties involved in demonstrating clear clinical efficacy of any form of clinical intervention in the TBI population need to be acknowledged. Hence, it is possible that following TBI, clinical heterogeneity and anatomical disconnections might necessitate modifications in the use of such neuromodulatory approaches or make these approaches fruitless. The use of correlative animal models may advance our understanding of how these modalities may act on the level of neuronal circuits and synapses following TBI, and would be particularly valuable in clarifying the rationales and the potential spectrum of translational applications before large randomized controlled trials are commenced.

6. SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS

The guidelines establishing the safe settings for TMS applications were published in 199852 and revised recently53. A decade and numerous rTMS studies later, rTMS has been shown to be safe with temporary minor side effects in normal subjects if these guidelines are followed.54,138 While rTMS also appears to be a good candidate tool for neuromodulation following TBI, current safety guidelines have not yet been tested for this high-risk population and the risk profile of rTMS likely includes other potential side effects in patients with TBI.

The most concerning adverse event related to a possible therapeutic application of rTMS is induction of a seizure. Post-traumatic epilepsy is the most common delayed sequel of TBI with an overall incidence of about 5% in patients with closed head injuries and 50% in those who had a compound skull fracture.158 Importantly, the interval between the head injury and the first seizure varies greatly. Although TMS-induced seizures are self-limited and do not tend to recur, this risk could bring practical implications in a seizure-prone population, especially in patients with moderate to severe TBI.

Secondly, as skull damage and fractures are common in TBI, the conductance and magnitude of the electric current being induced in cortical regions may be different. A recent tDCS modeling study highlighted that skull injuries significantly change the distribution of the current induced, and current may become concentrated over the edges of large skull defects depending on the combination of electrode configuration and nature of the defect.159 Such changes may alter the efficacy of these applications and may lead to unfavorable neurophysiologic or pathological changes. Further, the presence of a craniotomy with placement of skull plates might add another potential risk for application of these tools in TBI.160,161

Currently, there is only one case study, which performed detailed safety assessments and reported a lack of adverse events in a patient with severe TBI following application of a specific rTMS protocol over five consecutive days through six weeks. 162 It is clear that the heterogeneity of TBI necessitates further extensive safety evaluation studies and definition of relative contraindications for brain stimulation in patients with TBI before a serious assessment of benefit can be undertaken. Such studies would contribute to development of safety guidelines for TBI, which may enable the safe and efficacious use of brain stimulation techniques in the rehabilitation of TBI survivors.

7. CONCLUSION

Different forms of noninvasive brain stimulation techniques harbor the promise of diagnostic and therapeutic utility, particularly to guide processes of cortical reorganization and enable functional restoration in TBI. Available evidence is sparse, but the present understanding about the pathophysiology of post-traumatic brain damage and the mechanisms of action of various noninvasive brain stimulation methods justifies exploration of new interventions that may forestall the functional impact of TBI. Future lines of safety research and well-designed clinical trials in TBI are warranted to ascertain the capability of noninvasive brain stimulation to promote recovery and minimize disability.

TABLE 2.

Summary of motor cortical excitability studies using rTMS in traumatic brain injury

| Study | TBI type | Patient # (duration after trauma) |

Coil | TMS | Intensity | Tested measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chistyakov 1998 | minor TBI | 39 P, 21 C (2 weeks, 3 months) |

R | single pulse rTMS (1 Hz, 50 pulses) |

130-135% MT (70-90% MO) 110-115% MT |

MT CMCT MEP amplitude MEP variability |

Higher MT in TBI group Abnormal variability of MEP amplitude with rTMS: (a) progressive decrease of amp, complete abolition (b) irregular amplitude and chaotic form 3 months later- MEP variability and MT return to normal values in relation to clinical recovery |

| Chistyakov 1999 | minor TBI moderate TBI (diffuse/focal) |

64 P, 16 C (N/A) |

R | single pulse rTMS (1 Hz, 50 pulses) |

130-135% MT (70-90% MO) 110-115% MT |

MT MEP amplitude MEP variability CMCT SEP |

Higher MT and abnormal MEP variability in TBI group Higher pathological MEP findings in the moderate TBI group MEP abnormalities were more prominent in patients with clinical complaints and with focal contusions SEP and CMCT abnormalities were more prominent in DAI group |

| Moosavi 1999 | severe TBI anoxic BI |

19 P (13 TBI), 13 C (>6 months) |

R DC |

single pulse | 100% MT | MT MEP amplitude MEP variability CMCT |

Higher MT in the group unresponsive to verbal commands or multimodal sensory stimulation |

| Chistyakov 2001 | minor TBI moderate TBI |

38 P, 20 C (2 weeks) |

R | single pulse | 130% MT | MT MEP amplitude CMCT SP |

Higher MT and reduced MEP amplitude in mild to moderate TBI SP duration longer at 130% MT but not at lower intensities The degree of MEP and SP changes depended on severity of TBI |

| Centonze 2005 | minor TBI, minor TBI+PTSD |

25 P (14PTSD), 12 C (1-6 months) |

8 | single pulse paired pulse |

Co: 90% MT T: 500 μV |

MT MEP ISI 1-6 ms |

No significant differences between TBI and controls Less inhibition at ISI 2, 3, 4 ms in TBI+PTSD |

| Jang 2005 | DAI | 8 P, 13 C (4 months) |

R | single pulse | 120% MT | MT MEP fMRI |

No significant differences for MT or MEP amplitude Greater MEP duration and turns in the patient group No significant differences in M1 activated by the hand movements |

| Crossley 2005 | severe TBI | Case (4 weeks, 1 year) |

R | single pulse | N/A | MEP PET EEG SEP |

Increase in MEP amplitude compared to 4 weeks Increase in metabolic rate and regression in reduction (27% to 21%) Slow background EEG activity (theta frequency) was replaced with normal background activity (alpha frequency) |

| Barba 2005 | severe TBI | Case (3 months) |

8 | single pulse | 110% MT | MT MEP FMRI TCD |

Higher MT Reduced cortical representation via motor mapping, Lower voxels of brain activations via quantitative fMRI Altered vasomotor reactivity via TCD |

| Fujiki 2006 | DAI | 16 P, 16 C | 8 | single pulse paired pulse |

Co: 95% MT T: 1000 μV |

MT ISI 3,4,5,10,12,14 |

No significant differences between DAI and controls |

| Takeuchi 2006 | DAI | 20 P, 20 C | 8 | single pulse | 120% MT 150% MT |

MT MEP TCI (iMEP) |

TCI was significantly lower in patients and correlated with GCS |

| Yasokawa 2007 | DAI | 52 P, 17 C | 8 | single pulse | 50-100% MO | MT MEP DTI |

FA was significantly reduced in MEP (-) group FA reversely correlated with the increase in MT in MEP(+) group |

| Beaumont 2007 | mild TBI (concussion) |

30 P, 15 C (>9 months) |

8 | single pulse paired pulse |

Co: 80% MT T: 120% MT SP: 120% MT |

MT ISI 1,2,3,6,9,12 I/O SP |

SP was prolonged in the group with multiple concussions SP correlated with concussion severity |

| Beaumont 2009 | mild TBI (concussion) |

19 P, 21 C (27-41 years) |

8 | single pulse paired pulse |

Co: 80% MT T: 120% MT SP: 110, 120, 130% MT |

MT ISI 2,3,9,12,15 I/O SP |

SP was significantly prolonged and correlated with bradykinesia |

| Bernabeu 2009 | severe TBI+ DAI | 17 P, 11 C (>6 months) |

8 | single pulse | 110% MT | MT MEP area MEP variability I/O SP |

Higher MT, smaller MEP areas, narrower I/O curves Changes were more pronounced with DAI severity and motor dysfunction SP not significantly different |

Abbreviations: TBI: traumatic brain injury, DAI: diffuse axonal injury, PTSD: post traumatic stress disorder, P; patients, C: controls, N/A: not applicable, R; round coil, DC: double-cone coil, 8: figure-of-eight coil, MO: maximum machine output, MT: motor threshold, Co: conditioning stimulus, T: test stimulus, SP: silent period, CMCT: central motor conduction time, MEP: motor evoked potential, SEP: somatosensory evoked potential, ISI: interstimulus interval, fMRI: functional magnetic resonance imaging, PET: positron emission tomography, TCD: transcranial Doppler, TCI: transcallosal inhibition, iMEP: ipsilateral MEP, DTI: diffusion tensor imaging, I/O: input output curves, M1: primary motor cortex, GCS: glaskow coma scale, FA: fractional anisotropy.

Acknowledgements

Supported in part by a BBVA Translational Research Chair in Biomedicine, a grant from the International Brain Research Foundation (IBRF), and National Institutes of Health grant K 24 RR018875 to APL, and grant PI082004 from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III. Andrew Vahabzadeh-Hagh is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Medical Research Training Fellow.

Footnotes

Disclosure: APL serves as scientific advisor for Neosync, Neuronix, Nexstim, and Starlab. He holds IP for real-time integration of TMS with EEG and with MRI.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sorenson S, Kraus J. Occurrence, severity, and outcomes of brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1991;6:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maas AI, Stocchetti N, Bullock R. Moderate and severe traumatic brain injury in adults. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:728–741. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willemse-van Son AH, Ribbers GM, Verhagen AP, Stam HJ. Prognostic factors of long-term functioning and productivity after traumatic brain injury: a systematic review of prospective cohort studies. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21:1024–1037. doi: 10.1177/0269215507077603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fontaine A, Azouvi P, Remy P, Bussel B, Samson Y. Functional anatomy of neuropsychological deficits after severe traumatic brain injury. Neurology. 1999;53:1963–1968. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bramlett HM, Dietrich WD. Pathophysiology of cerebral ischemia and brain trauma: similarities and differences. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:133–150. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000111614.19196.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Syntichaki P, Tavernarakis N. The biochemistry of neuronal necrosis: rogue biology? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:672–684. doi: 10.1038/nrn1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saatman K, Duhaime AC, Bullock R, Maas AIR, Valadka A, Manley GT, Workshop Scientific Team and Advisory Panel Members Classification of Traumatic Brain Injury for Targeted Therapies. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25:719–738. doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faden AI, Demediuk P, Panter SS, Vink R. The role of excitatory amino acids and NMDA receptors in traumatic brain injury. Science. 1989;244:798–800. doi: 10.1126/science.2567056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker AJ, Moulton RJ, MacMillan VH, Shedden PM. Excitatory amino acids in cerebrospinal fluid following traumatic brain injury in humans. J Neurosurg. 1993;79:369–372. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.79.3.0369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rothman SM, Olney JW. Glutamate and the pathophysiology of hypoxic--ischemic brain damage. Ann Neurol. 1986;19:105–111. doi: 10.1002/ana.410190202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yurkewicz L, Weaver J, Bullock MR, Marshall LF. The effect of the selective NMDA receptor antagonist traxoprodil in the treatment of traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22:1428–1443. doi: 10.1089/neu.2005.22.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calabresi P, Centonze D, Pisani A, Cupini L, Bernardi G. Synaptic plasticity in the ischaemic brain. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:622–629. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katsura K, Kristián T, Siesjö BK. Energy metabolism, ion homeostasis, and cell damage in the brain. Biochem Soc Trans. 1994;22:991–996. doi: 10.1042/bst0220991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kristián T, Siesjö BK. Calcium in ischemic cell death. Stroke. 1998;29:705–18. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.3.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park CK, Nehls DG, Teasdale GM, McCulloch J. Effect of the NMDA antagonist MK-801 on local cerebral blood flow in focal cerebral ischaemia in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1989;9:617–622. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1989.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forster C, Clark HB, Ross ME, Iadecola C. Inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in human cerebral infarcts. Acta Neuropathol. 1999;97:215–220. doi: 10.1007/s004010050977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holtz M. Rapid expression of neuronal and inducible nitric oxide synthases during post-ischemic reperfusion in rat brain. Brain Res. 2001;898:49–60. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)02140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nogawa S, Zhang F, Ross ME, Iadecola C. Cyclo-oxygenase-2 gene expression in neurons contributes to ischemic brain damage. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2746–2755. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02746.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lo EH. A new penumbra: transitioning from injury into repair after stroke. Nat Med. 2008;14:497–500. doi: 10.1038/nm1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raymont V, Grafman J. Cognitive neural plasticity during learning and recovery from brain damage. Prog Brain Res. 2006;157:199–206. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)57013-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stroemer RP, Kent TA, Hulsebosch CE. Neocortical neural sprouting, synaptogenesis, and behavioral recovery after neocortical infarction in rats. Stroke. 1995;26:2135–2144. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.11.2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robertson IH, Murre JM. Rehabilitation of brain damage: brain plasticity and principles of guided recovery. Psychol Bull. 1999;125:544–575. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.5.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becerra GD, Tatko LM, Pak ES, Murashov AK, Hoane MR. Transplantation of GABAergic neurons but not astrocytes induces recovery of sensorimotor function in the traumatically injured brain. Behav Brain Res. 2007;179:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Dell DM, Gibson CJ, Wilson MS, DeFord SM, Hamm RJ. Positive and negative modulation of the GABA(A) receptor and outcome after traumatic brain injury in rats. Brain Res. 2000;861:325–332. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02055-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pascual JM, Solivera J, Prieto R, Barrios L, López-Larrubia P, Cerdán S, Roda JM. Time course of early metabolic changes following diffuse traumatic brain injury in rats as detected by (1)H NMR spectroscopy. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:944–959. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer AM, Marion DW, Botscheller ML, Bowen DM, DeKosky ST. Increased transmitter amino acid concentration in human ventricular CSF after brain trauma. Neuroreport. 1994;6:153–156. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199412300-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shulga A, Thomas-Crusells J, Sigl T, Blaesse A, Mestres P, Meyer M, Yan Q, Kaila K, Saarma M, Rivera C, Giehl KM. Posttraumatic GABA(A)-mediated [Ca2+]i increase is essential for the induction of brain-derived neurotrophic factor-dependent survival of mature central neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6996–7005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5268-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobori N, Dash PK. Reversal of brain injury-induced prefrontal glutamic acid decarboxylase expression and working memory deficits by D1 receptor antagonism. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4236–4246. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4687-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoskison MM, Moore AN, Hu B, Orsi S, Kobori N, Dash PK. Persistent working memory dysfunction following traumatic brain injury: evidence for a time-dependent mechanism. Neuroscience. 2009;159:483–491. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.12.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Erb DE, Povlishock JT. Neuroplasticity following traumatic brain injury: a study of GABAergic terminal loss and recovery in the cat dorsal lateral vestibular nucleus. Exp Brain Res. 1991;83:253–267. doi: 10.1007/BF00231151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garraghty PE, LaChica EA, Kaas JH. Injury-induced reorganization of somatosensory cortex is accompanied by reductions in GABA staining. Somatosens Mot Res. 1991;8:347–354. doi: 10.3109/08990229109144757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pascual-Leone A, Amedi A, Fregni F, Merabet LB. The plastic human brain cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:377–401. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blumbergs PC, Jones NR, North JB. Diffuse axonal injury in head trauma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989;52:838–841. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.52.7.838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jang SH, Cho SH, Kim YH, You SH, Kim SH, Kim O, Yang DS, Son S. Motor recovery mechanism of diffuse axonal injury: a combined study of transcranial magnetic stimulation and functional MRI. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2005;23:51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Povlishock JT, Katz DI. Update of neuropathology and neurological recovery after traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2005;20:76–94. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200501000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steward O. Reorganization of neural connections following CNS trauma. Principles and experimental paradigms. J Neurotrauma. 1989;6:99–152. doi: 10.1089/neu.1989.6.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blumbergs PC, Jones NR, North JB. Diffuse axonal injury in head trauma. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989;52:838–841. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.52.7.838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobayashi M, Pascual-Leone A. Transcranial magnetic stimulation in neurology. Lancet Neurol. 2003;2:145–156. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00321-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner T, Valero-Cabre A, Pascual-Leone A. Noninvasive human brain stimulation. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2007;9:527–565. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.061206.133100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pascual-Leone A, Davey N, Rothwell J, Wassermann E, Puri B, editors. Handbook of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation. Oxford University Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reis J, Swayne OB, Vandermeeren Y, Camus M, Dimyan MA, Harris-Love M, Perez MA, Ragert P, Rothwell JC, Cohen LG. Contribution of transcranial magnetic stimulation to the understanding of cortical mechanisms involved in motor control. J Physiol. 2008;586:325–351. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.144824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hallett M. Transcranial magnetic stimulation: a primer. Neuron. 2007;55:187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang YZ, Edwards MJ, Rounis E, Bhatia KP, Rothwell JC. Theta burst stimulation of the human motor cortex. Neuron. 2005;45:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di Lazzaro V, Pilato F, Saturno E, Oliviero A, Dileone M, Mazzone P, Insola A, Tonali PA, Ranieri F, Huang YZ, Rothwell JC. Theta-burst repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation suppresses specific excitatory circuits in the human motor cortex. J Physiol. 2005;565:945–950. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Silvanto J, Pascual-Leone A. State-dependency of transcranial magnetic stimulation. Brain Topogr. 2008;21:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10548-008-0067-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valero-Cabré A, Pascual-Leone A. Impact of TMS on the primary motor cortex and associated spinal systems. IEEE Eng Med Biol Mag. 2005;24:29–35. doi: 10.1109/memb.2005.1384097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Valero-Cabré A, Payne BR, Pascual-Leone A. Opposite impact on 14C-2-deoxyglucose brain metabolism following patterns of high and low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the posterior parietal cortex. Exp Brain Res. 2007;176:603–615. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0639-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Paus T, Jech R, Thompson CJ, Comeau R, Peters T, Evans AC. Transcranial magnetic stimulation during positron emission tomography: a new method for studying connectivity of the human cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3178–3184. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-09-03178.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sack AT, Kohler A, Bestmann S, Linden DE, Dechent P, Goebel R, Baudewig J. Imaging the brain activity changes underlying impaired visuospatial judgments: simultaneous FMRI, TMS, and behavioral studies. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:2841–2852. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bestmann S. The physiological basis of transcranial magnetic stimulation. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12:81–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ridding MC, Rothwell JC. Is there a future for therapeutic use of transcranial magnetic stimulation? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:559–567. doi: 10.1038/nrn2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wassermann EM. Risk and safety of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: report and suggested guidelines from the International Workshop on the Safety of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, June 5-7, 1996. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;108:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0168-5597(97)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rossi S, Hallett M, Rossini PM, Pascual-Leone A, The Safety of TMS Consensus Group Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research. Clin Neurophysiol. 2009;120:2008–2039. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Machii K, Cohen D, Ramos-Estebanez C, Pascual-Leone A. Safety of rTMS to non-motor cortical areas in healthy participant and patients. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117:455–471. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pascual-Leone A, Houser C, Reeves K. Safety of rapid-rate transcranial magnetic stimulation in normal volunteers. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1993;89:120–130. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(93)90094-6. al e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wassermann E, Grafman J, Berry C, Hollnagel C, Wild K, Clark K, Hallett M. Use and safety of a new repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulator. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1996;101:412–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen R, Gerloff C, Wassermann E, Hallett M, Cohen LG. Safety of different inter-train intervals for repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and recommendations for safe ranges of stimulation parameters. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1997;105:415–421. doi: 10.1016/s0924-980x(97)00036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nitsche MA, Paulus W. Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. J Physiol. 2000;527:633–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nitsche MA, Paulus W. Sustained excitability elevations induced by transcranial DC motor cortex stimulation in humans. Neurology. 2001;57:1899–1901. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.10.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fregni F, Boggio PS, Santos MC, Lima M, Vieira AL, Rigonatti SP, Silva MT, Barbosa ER, Nitsche MA, Pascual-Leone A. Noninvasive cortical stimulation with transcranial direct current stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2006;21:1693–1702. doi: 10.1002/mds.21012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boggio PS, Nunes A, Rigonatti SP, Nitsche MA, Pascual-Leone A, Fregni F. Repeated sessions of noninvasive brain DC stimulation is associated with motor function improvement in stroke patients. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2007;25:123–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Priori A. Brain polarization in humans: a reappraisal of an old tool for prolonged non-invasive modulation of brain excitability. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:589–595. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00437-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Purpura D, McMurtry J. Intracellular activities and evoked potential changes during polarization of motor cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1965;28:166–185. doi: 10.1152/jn.1965.28.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nitsche MA, Liebetanz D, Antal A, Lang N, Tergau F, Paulus W. Modulation of cortical excitability by weak direct current stimulation technical, safety and functional aspects. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;56:255–276. doi: 10.1016/s1567-424x(09)70230-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liebetanz D, Nitsche MA, Tergau F, Paulus W. Pharmacological approach to the mechanisms of transcranial DC-stimulation-induced after effects of human motor cortex excitability. Brain. 2002;125:2238–2247. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lang N, Siebner HR, Ward NS, Lee L, Nitsche MA, Paulus W, Rothwell JC, Lemon RN, Frackowiak RS. How does transcranial DC stimulation of the primary motor cortex alter regional neuronal activity in the human brain? Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:495–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.George MS, Aston-Jones G. Noninvasive techniques for probing neurocircuitry and treating illness: vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:301–316. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wagner T, Fregni F, Fecteau S, Grodzinsky A, Zahn M, Pascual-Leone A. Transcranial direct current stimulation: a computer-based human model study. Neuroimage. 2007;35:1113–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gandiga PC, Hummel FC, Cohen LG. Transcranial DC stimulation (tDCS): a tool for double-blind sham-controlled clinical studies in brain stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2006;117:845–850. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Boggio PS, Castro LO, Savagim EA, Braite R, Cruz VC, Rocha RR, Rigonatti SP, Silva MT, Fregni F. Enhancement of non-dominant hand motor function by anodal transcranial direct current stimulation. Neurosci Lett. 2006;404:232–236. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fregni F, Boggio PS, Mansur CG, Wagner T, Ferreira MJ, Lima MC, Rigonatti SP, Marcolin MA, Freedman SD, Nitsche MA, Pascual-Leone A. Transcranial direct current stimulation of the unaffected hemisphere in stroke patients. Neuroreport. 2005;16:1551–1555. doi: 10.1097/01.wnr.0000177010.44602.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hummel F, Cohen LG. Improvement of motor function with noninvasive cortical stimulation in a patient with chronic stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2005;19:14–19. doi: 10.1177/1545968304272698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Floel A, Cohen LG. Contribution of noninvasive cortical stimulation to the study of memory functions. Brain Res Rev. 2007;53:250–259. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Monti A, Cogiamanian F, Marceglia S, Ferrucci R, Mameli F, Mrakic-Sposta S, Vergari M, Zago S, Priori A. Improved naming after transcranial direct current stimulation in aphasia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:451–453. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.135277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Iyer MB, Mattu U, Grafman J, Lomarev M, Sato S, Wassermann EM. Safety and cognitive effect of frontal DC brain polarization in healthy individuals. Neurology. 2005;64:872–875. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152986.07469.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fregni F, Boggio PS, Nitsche M, Bermpohl F, Antal A, Feredoes E, Marcolin MA, Rigonatti SP, Silva MT, Paulus W, Pascual-Leone A. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation of prefrontal cortex enhances working memory. Exp Brain Res. 2005;166:23–30. doi: 10.1007/s00221-005-2334-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ferrucci R, Mameli F, Guidi I, Mrakic-Sposta S, Vergari M, Marceglia S, Cogiamanian F, Barbieri S, Scarpini E, Priori A. Transcranial direct current stimulation improves recognition memory in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2008;71:493–498. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000317060.43722.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fecteau S, Knoch D, Fregni F, Sultani N, Boggio P, Pascual-Leone A. Diminishing risk-taking behavior by modulating activity in the prefrontal cortex: a direct current stimulation study. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12500–12505. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3283-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Knoch D, Nitsche MA, Fischbacher U, Eisenegger C, Pascual-Leone A, Fehr E. Studying the neurobiology of social interaction with transcranial direct current stimulation--the example of punishing unfairness. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:1987–1990. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fecteau S, Fregni F, Camprodon JC, Pascual-Leone A. Neuromodulation of the addictive brain. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45:1766–1786. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.482434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rioult-Pedotti MS, Friedman D, Hess G, Donoghue JP. Strengthening of horizontal cortical connections following skill learning. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:230–234. doi: 10.1038/678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Poreisz C, Boros K, Antal A, Paulus W. Safety aspects of transcranial direct current stimulation concerning healthy subjects and patients. Brain Res Bull. 2007;72:208–214. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Edwards DJ, Krebs HI, Rykman A, Zipse J, Thickbroom GW, Mastaglia FL, Pascual-Leone A, Volpe BT. Raised corticomotor excitability of M1 forearm area following anodal tDCS is sustained during robotic wrist therapy in chronic stroke. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2009;27:199–207. doi: 10.3233/RNN-2009-0470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Williams JA, Pascual-Leone A, Fregni F. Interhemispheric modulation induced by cortical stimulation and motor training. Phys Ther. 2010;90:398–410. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20090075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hesse S, Werner C, Schonhardt EM, Bardeleben A, Jenrich W, Kirker SG. Combined transcranial direct current stimulation and robot-assisted arm training in subacute stroke patients: a pilot study. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2007;25:9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Soler MD, Kumru H, Pelayo R, Vidal J, Tormos JM, Fregni F, Navarro X, Pascual-Leone A. Effectiveness of transcranial direct current stimulation and visual illusion on neuropathic pain in spinal cord injury. Brain. 2010;133:2565–2577. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ilic S, Leichliter S, Streeter J, Oron A, DeTaboada L, Oron U. Effects of Power Densities, Continuous and Pulse Frequencies, and Number of Sessions of Low-Level Laser Therapy on Intact Rat Brain. Photomed Laser Surg. 2006;24:458–466. doi: 10.1089/pho.2006.24.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lampl Y, Zivin JA, Fisher M, Lew R, Welin L, Dahlof B, Borenstein P, Andersson B, Perez J, Caparo C, Ilic S, Oron U. Infrared laser therapy for ischemic stroke: a new treatment strategy: results of the NeuroThera Effectiveness and Safety Trial-1 (NEST-1) Stroke. 2007;38:1843–1849. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.478230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Oron A, Oron U, Chen J, Eilam A, Zhang C, Sadeh M, Lampl Y, Streeter J, DeTaboada L, Chopp M. Low-level laser therapy applied transcranially to rats after induction of stroke significantly reduces long-term neurological deficits. Stroke. 2006;37:2620–2624. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000242775.14642.b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]