Abstract

Background

Varenicline is a partial nicotinic receptor agonist that is an effective smoking cessation medication. Preliminary evidence indicates that it may also reduce alcohol consumption but the underlying mechanism is not clear. For example, varenicline may reduce alcohol consumption by attenuating its subjectively rewarding properties or by enhancing its aversive effects. In this study, we examined the effects of an acute dose of varenicline upon subjective, physiological and objective responses to low and moderate doses of alcohol in healthy social drinkers.

Methods

Healthy men and women (N=15) participated in six randomized sessions; three sessions each with 2mg varenicline and placebo followed 3 hours later by a beverage containing placebo, low dose alcohol (0.4g/kg), or high dose alcohol (0.8g/kg). Subjective mood and drug effects (i.e., stimulation, drug liking), physiological measures (heart rate, blood pressure), and eye tracking tasks were administered at various intervals before and after drug and alcohol administration.

Results

Varenicline acutely increased blood pressure, heart rate, ratings of dysphoria and nausea, and also improved eye tracking performance. After alcohol drinking (vs placebo), varenicline increased dysphoria and tended to reduce alcohol liking ratings. It also attenuated alcohol-induced eye-tracking impairments. These effects were independent of the drug’s effects on nausea before drinking.

Conclusions

Our data support the theory that varenicline may reduce drinking by potentiating aversive effects of alcohol. Varenicline also offsets alcohol-induced eye movement impairment. The evidence suggests that varenicline may decrease alcohol consumption by producing effects which oppose the rewarding efficacy of alcohol.

Keywords: Varenicline, Alcohol, Subjective effects, Eye-tracking

Introduction

Varenicline (Chantix®) is a partial nicotinic receptor agonist that is an effective smoking cessation aid. Anecdotally, some smokers treated with varenicline report that they consume less alcohol, which suggests that the drug may also be an efficacious treatment for alcoholism. Indeed, there is evidence from controlled studies in rodents and humans that varenicline reduces alcohol consumption (Bito-Onon et al., 2011; Kamens et al, 2010a; McKee et al, 2009; Steensland et al, 2007; Wouda et al, 2011). However, the mechanisms by which varenicline reduces alcohol drinking are unclear.

Among its many other actions, alcohol is known to act on the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) where it potentiates the effects of acetylcholine and nicotine (Davis and de Fiebre, 2006; Ei-Fakahany et al., 1983). In rodents, nAChRs reportedly mediate the effects of alcohol upon locomotor activity, cognition and alcohol self-administration. Nicotine enhances the locomotor activating (Blomqvist et al., 1992; Johnson et al., 1995) and interoceptive effects of alcohol (Signs and Schechter, 1986), and it increases alcohol drinking (Bito-Onon et al., 2011; Clark et al., 2001; Lopez-Moreno et al., 2004; Potthoff et al., 1983; Smith et al., 1999) and reinstates alcohol seeking (Le et al., 2003). Nicotinic antagonists attenuate these effects (Blomqvist et al., 1992, 1997, 2002).

Some of the interactions between alcohol and nicotine may be mediated by nAChRs within the mesolimbic dopamine system. Animal studies show that, when administered together, nicotine and alcohol produce synergistic effects on mesolimbic dopamine system activity as well as additive effects on dopamine turnover in the brain and release in the nucleus accumbens (Clark and Little, 2004; Johnson et al., 1995; Tizabi et al., 2007). In addition, nicotinic antagonists attenuate alcohol-induced effects in the mesolimbic dopamine system (Blomqvist et al., 1992, 1997; Soderpalm et al., 2000). Moreover, in humans, nicotine potentiates the subjective rewarding effects, craving, and consumption of alcohol, while nicotinic antagonists attenuate these effects (Acheson et al., 2006; Blomqvist et al., 2002; Chi and de Wit, 2003; Kouri et al., 2004, Penetar et al., 2009; Young et al., 2005). A partial nAChR agonist like varenicline might either potentiate the effects of alcohol (through its agonist effects) or block the effects of alcohol, by occupying the receptors. Recently, it was reported that varencline reduced alcohol-induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens (Ericson et al., 2009), suggesting that it may decrease alcohol-associated reward and motivational effects in humans through its effects on mesolimbic dopaminergic transmission.

Varenicline interacts with several nicotinic receptor subtypes. It is a partial agonist at α4β2, α3β2, and α6 receptors and a full agonist at α7 and α3β4 (Coe et al., 2005; Rollema et al., 2007). Overall, varenicline antagonizes effects mediated by α4β2, α3β2, and α6 receptors, making these receptors good candidates for actions on alcohol effects. There is evidence that varenicline reduces self-reported alcohol craving and consumption in heavy drinking smokers (McKee et al., 2009) and increases aversive effects of alcohol, such as its sedative and ataxic effects (Kamens et al., 2010b; Fucito et al., 2011). Collectively, these findings suggest that varenicline may reduce alcohol drinking behaviour by either reducing its subjectively rewarding or motivating properties or alternatively by increasing its sedative-like properties. To our knowledge, there have been no human laboratory studies to date examining the acute effects of varenicline (vs. placebo) on multiple domains of alcohol responses, and at different alcohol dose levels.

In the present study, we measured the effects of acute varenicline administration (0, 2mg) on the subjective and objective (eye tracking) responses to alcohol (0, 0.4, 0.8g/kg). We hypothesized, based on previous studies (Fucito et al., 2011; Kamens et al., 2010b; McKee et al., 2009), that varenicline would reduce the subjectively rewarding effects of a high alcohol dose, while increasing negative mood states, including sedation and dysphoria. We also hypothesised that varenicline would counteract alcohol-induced impairments in eye tracking performance (Roche and King, 2010), specifically in the anti-saccade task where nicotine appears to have its largest effect (Larrison et al., 2004; Rycroft et al., 2006).

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Healthy moderate-to-heavy social drinkers (N=15; 7 female) who were non-dependent alcohol drinking and non dependent smokers, and not currently seeking treatment for either substance, were enrolled. Exclusion criteria included a current or prior diagnosis of a Major Axis I DSM-IV disorder (APA, 1994) including substance dependence within the past two years or a lifetime history of alcohol dependence (ascertained using a modified version of the research SCID), a serious medical condition, high blood pressure, abnormal electrocardiogram, daily use of medications, a body mass index outside of 19–26 kg/m2, age outside of 21 to 45 years, less than high school education or lack of fluency in English, night shift work, and, in women, pregnancy, lactation or lack of a reliable method of birth control. To be eligible, subjects had to meet criteria for heavy social drinking, which was operationally defined as consuming at least 10 alcoholic drinks per week (SAMHSA, 2007), with at least one weekly binge episode (five or more drinks for men, and four or more drinks for women, on a single occasion) and smoke no more than 5 cigarettes per day. These criteria were chosen to be generally consistent with prior studies (Esterlis et al., 2010; King et al., 2011; McKee et al., 2010). We chose to examine a subgroup of regular heavy drinkers because they exhibit biphasic alcohol responses (King et al., 2011) with non dependent lighter smoking patterns to avoid confounds of tobacco withdrawal or difficulty complying with 10 hours of smoking abstinence as required prior to and during the sessions. Qualifying participants signed a consent form which stated that the study was designed to investigate the effects of a drug on the subjective and behavioural effects of alcohol. For blinding purposes, they were told that the capsule they might receive could contain a stimulant (appetite suppressant), a smoking cessation aid, alcohol or placebo (sugar). They were told that the beverages they received may or may not contain alcohol. They agreed not to consume any drugs other than their normal amounts of caffeine for 24 hrs before and 12 hrs after each session and not to consume any food during the sessions, other than that provided by the experimenters. They were allowed to eat as normal before sessions but could not smoke the morning of the experimental sessions, which was verified by a breath CO level of <7ppm upon arrival.

Study Design

Subjects were tested individually in six 6h experimental sessions that began at noon and were conducted at least three days apart. During the sessions, participants received a capsule containing 2mg varenicline or placebo (VAR, PL), followed 3 hours later by a beverage containing 0, 0.4 or 0.8g/kg alcohol (0, 0.4, 0.8). Thus, there were six conditions; VAR-0, VAR-0.4, VAR-0.8, PL-0, PL-0.4, PL-0.8. The order of drug and beverage doses was determined randomly and drug and alcohol administration was double blind. Breath alcohol concentration levels, subjective effects, heart rate, blood pressure and eye tracking were measured at repeated intervals before and after the capsule and the beverage was consumed in each session. We chose eye tracking tasks as an objective measure of alcohol response as performance in such tasks is impaired after alcohol ingestion, particularly at intoxicating doses (Roche and King 2010), but enhanced after nicotine administration (Larrison et al., 2004; Rycroft et al., 2006). We chose acute varenicline dosing as single doses of varenicline up to 3mg have been reported to be well-tolerated even among non-smokers (Faessel et al., 2006) and our focus for clinical relevance was the immediate response to single doses which have been shown to interact with nicotinic receptors (Rollema et al., 2007). Our rationale for alcohol dose selections were that 0.8 g/kg increases ratings of stimulation, liking and wanting in heavy social drinkers (King et al., 2011) and to compare this to 0.4 g/kg, a lighter sub-threshold dose which produces more mild subjective changes. The placebo beverage was included as a control for alcohol expectancy effects.

Experimental Procedure

The University of Chicago Hospital’s Institutional Review Committee for the use of human subjects approved the experimental protocol. Experimental sessions were conducted in comfortably furnished rooms with a television/VCR, magazines, and a computer for administering questionnaires.

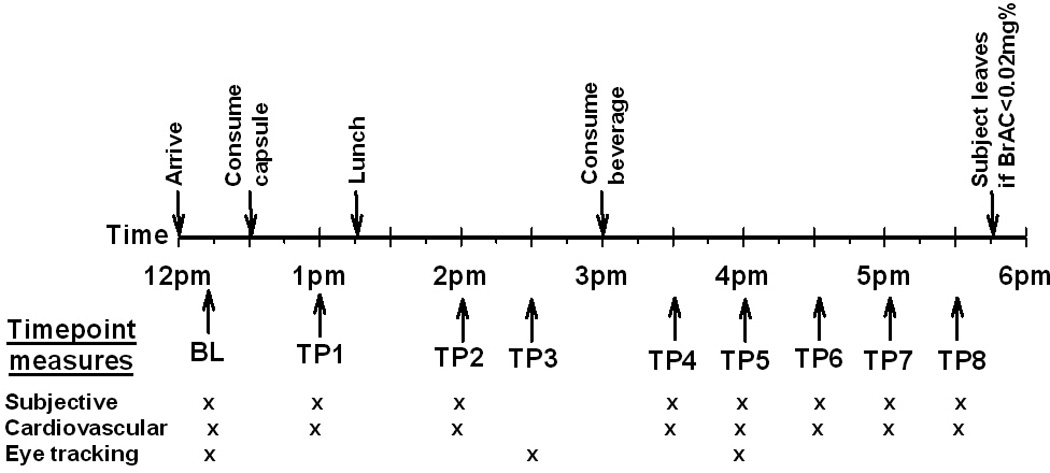

Figure 1 shows the timing of procedures during sessions. Upon arrival (12:00pm) at the laboratory for each session, the subject provided breath and urine samples to confirm compliance with abstinence instructions and to confirm non-pregnancy in females. The subject relaxed in the testing room before baseline (BL) subjective, vital signs and eye tracking measures were obtained. The subject then consumed a capsule (at 12:30pm) that contained either 2mg varenicline or placebo. During the following several hours, the participant relaxed in the testing room and subjective and cardiovascular measures were obtained at regular intervals, a light lunch was given, and the eye tracking tasks were re-examined. The drinking interval began three hours after administration of the capsules (at 3:30pm). This was chosen to coincide with peak plasma levels of varenicline (Kikkawa et al, 2011). As in our prior studies (e.g. King et al., 2011) participants consumed a beverage containing 0, 0.4 or 0.8g/kg alcohol over 15 min (two 5 min periods of consuming a half portion with a 5 min rest in between). Subjective and cardiovascular measures were obtained regularly after beverage consumption (time points 4-8), and the eye tracking task was re-administered during approximate peak BrAC (breath alcohol concentration), 45–60 min after consuming the beverage. The final time point was at 5:30pm (150min after consumption of the beverage). In-between the measurements, participants were allowed to watch television, movies, or read. At the end of the session, participants completed a questionnaire to rate their overall experience and were then allowed to leave the laboratory. At the end of the study, participants were debriefed about the study aims and received payment.

Figure 1.

Schematic showing the timing of drug and drink administration, and collection of subjective, cardiovascular, and behavioral measures during the experimental sessions. BL = Baseline, TP = Time point.

Dependent Measures

Subjective effects of drugs were assessed using the Addiction Research Centre Inventory (ARCI; Martin et al., 1971), the Drug Effects Questionnaire (DEQ; Folstein and Luria, 1973) and the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Questionnaire (BAES; Martin et al., 1993). “Nauseated” was also assessed using an 11-point scale similar to that used in the BAES (0“not at all” to 10 “extremely”). The Brief Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (BQSU; Tiffany and Drobes, 1991) was included to assess ratings of urge to smoke during the sessions.

Heart rate and blood pressure were measured at repeated intervals (see Figure 1) using a digital monitor (Dinamap 1846SX, Critikon, Tampa, FL). At each interval, three readings were obtained and the average used in analyses.

Eye movements were measured at three times (i.e., Pre-capsule, 150 min Post-capsule, and 45 min Post-drink) and analyzed using the VisualEyes™ VNG system (Micromedical Technologies, Chatham, IL), a non-invasive oculographic device (for details, see Roche & King, 2010). In brief, subjects wore goggles containing a monocular camera designed to center and track the pupil of the right eye as a 2.5 × 5mm red LED moved along a digital light bar placed 1 meter in front of the subject. At each time point (baseline, post-capsule, post-beverage), the subject tracked random horizontal and vertical targets to calibrate eye position and then completed three tasks: 1) Smooth Pursuit – the subject was instructed to follow a target travelling horizontally across the display in a predictable, oscillating sinusoidal waveform for 75 seconds; 2) Pro-saccade – the subject was instructed to locate and fixate on successive targets that were presented at random locations for 1–3s; and 3) Anti-saccade –the subject was instructed to direct visual gaze to the mirror position on the opposite side of the midline of randomly presented targets. The outcome measure for smooth pursuit was gain, the ratio of the velocity of the subject’s eye to the velocity of the stimulus. For both saccade tasks, the software calculated latency (the interval in milliseconds between target presentation and initiation of the saccadic eye movement), velocity (the peak rate in degrees/second of the saccadic eye movement), and accuracy (the ratio of the amplitude of the initial saccade to the amplitude of target) for all directionally correct saccades. As in Roche and King (2010), directionally incorrect saccades and those 50% below and 133% above each subject’s mean were discarded as these were likely artefacts due to movements or blinks. Percent Accepted refers to the number of directionally correct saccades accepted by the software, divided by the number of target presentations in each saccade task (n=30). Two subjects’ eye tracking data were not analyzed due to technical difficulties.

Drugs

Varenicline (2mg, CHANTIX®, Pfizer Inc, New York, NY) was administered in opaque gelatin capsules (size 00) with dextrose filler. Placebo capsules contained only dextrose. Beverages consisted of flavored drink mix, water, and a sucralose-based sugar substitute and the appropriate dose of 190-proof ethanol, with 16% and 8% alcohol by volume for the high and low doses, respectively, and 1% alcohol by volume for placebo as a taste mask. Women received an approximate 85 percent of the dose of alcohol administered to men (i.e. 0.34 g/kg or 0.68 g/kg) to adjust for sex differences in body composition (Sutker et al. 1983).

Data Analysis

Changes in the subjective and cardiovascular measures during each experimental session were calculated as the area under the curve (AUC, using the trapezoid method) relative to baseline. The effects of varenicline upon the measures before drinking were assessed by comparing the average AUC before drinking during the 3 varenicline sessions to that during the placebo sessions using a paired samples t-test. The effect of repeated exposure to varenicline was assessed by comparing drug responses (before drinking) on the first, second and third administrations using a one factor (Session) analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures. The effects of alcohol alone upon dependent measures i.e., during the placebo pill sessions, were assessed by comparing the AUCs post-drink using a one factor (Drink) multivariate ANOVA. Significant effects were further examined using pair wise comparisons with correction for multiple testing. Then, effects of varenicline, alcohol and their interactive effects upon the measures were assessed using two within-subjects factor (Drug × Drink) multivariate analyses upon AUC values. For interactions between varenicline and alcohol, the four primary subjective measures (BAES Stimulation and Sedation, DEQ liking and ARCI LSD), differences were considered to be significant at p<0.013 (Bonferroni correction for multiple testing). For secondary measures, differences were considered to be significant at p<0.007. Effect sizes are reported using partial eta squared (ηp2) for analyses of variance; 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 are considered small, medium, and large effect sizes respectively.

Since eye tracking measures were collected at less frequent intervals than the other measures (i.e. at three time points) due to the length of time to administer this task, data were analyzed using raw data three factor (Pill × Drink × Time) repeated measures ANOVAs for smooth pursuit, saccade and anti-saccade tasks. The effects of alcohol alone were assessed using a two factor (Drink × Time) repeated measures ANOVA only within the placebo pill sessions. Interactions at p<0.05 were further explored with Tukey’s post hoc tests. Since nausea is the most common side effect of varenicline particularly during early dosing that also occurred in this study, ratings for the item “nauseated” were included as a covariate in all the above-mentioned analyses.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

The demographic characteristics of participants including levels of current drinking and smoking, are shown in Table 1. The majority of subjects were of European American descent and aged in their mid-twenties. Participants reported consuming on average 4.5±0.2 alcohol drinks per occasion with 3.6±0.4 occasions per week. Similar to prior studies, they engaged in frequent binge drinking with an average of 7.8±1.1 episodes per month. They smoked on average 3.9±0.7 cigarettes per smoking day and reported an average of 3.6±0.6 smoking days per week. On drinking days, they smoked an average of 4.7±1.0 cigarettes. The mean FTND (The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence; Heatherton et al., 1991) score for participants was 0.5±0.2 (range 0–3), supporting the lack of physical nicotine dependence in the sample.

Table 1.

Demographic and drug use characteristics of participants.

| Characteristic | Mean±SEM (range) |

|---|---|

| N male/N female | 8/7 |

| Age (years) | 26.9 ± 1.1 (21–35) |

| BMI (kg.m−2) | 23.7 ± 0.8 (18.9–29.0) |

| Race | |

| # European American | 13 |

| # African American | 1 |

| # >1 | 1 |

| Smoking Characteristics: | |

| FTND Total | 0.5 ± 0.2 (0–3) |

| # smoking days/mo | 15.5 ± 2.7 (1–26) |

| # cigs/non drinking day | 1.9 ± 0.5 (1–5) |

| # cigs/drinking day | 4.7 ± 1.0 (1–11.2) |

| Alcohol Drinking: | |

| # drinking days/mo | 15.5 ± 1.6 (5–25) |

| # drinks/drinking day | 4.5 ± 0.2 (3–7) |

| # binges in last mo | 7.8 ± 1.1 (2–19) |

| Other Drug Use: | |

| Caffeine cups/wk | 20.0 ± 4.8 (1–70) |

| Marijuana times/mo | 4.2 ± 1.6 (0–15) |

| Lifetime Drug Use (% ever used) | |

| Marijuana | 93 |

| Opiates | 93 |

| Hallucinogens | 67 |

| Stimulants | 60 |

| Inhalants | 33 |

| Sedatives | 27 |

Effects of Varenicline before drinking

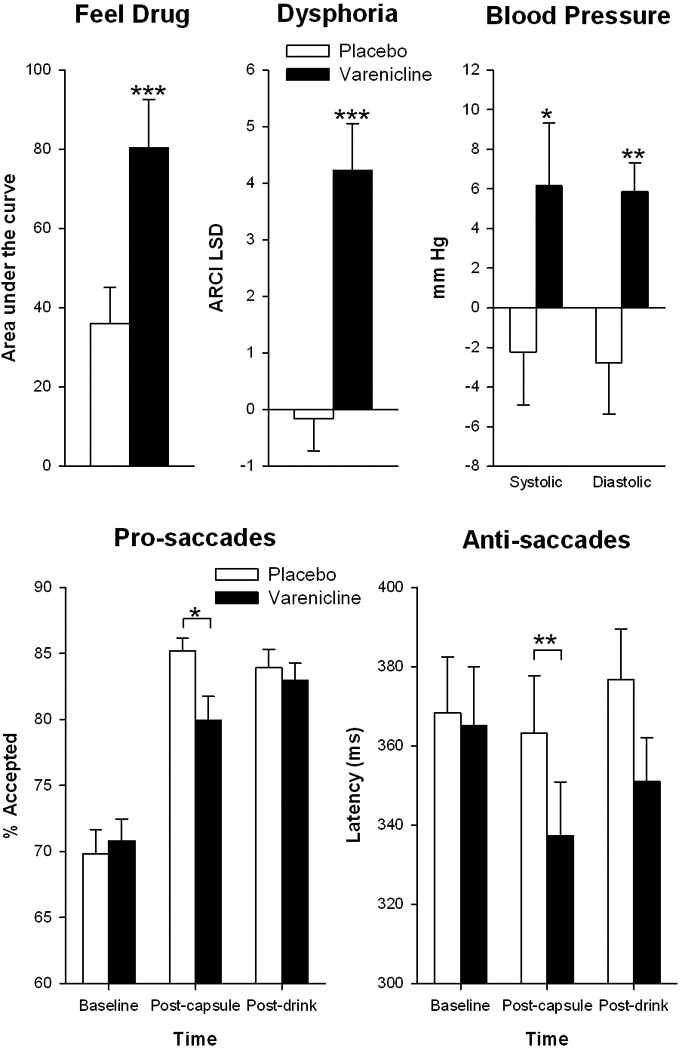

The effects of varenicline alone (i.e., before the beverage consumption interval) are shown in Figure 2. Relative to placebo, varenicline significantly increased ratings of “feel drug” [t(14)=−4.3 p=0.001], “feel high” [t(14)=−2.7 p<0.05] and dysphoria [ARCI LSD, t(14)=−4.7 p<0.001], and decreased ratings of “drug liking” [t(14)=4 p=0.001] and “want more drug” [t(14)=2.9 p=0.01]. Varenicline increased ratings of “nauseated”: mean peak scores were 0.02±0.02 for placebo, and 2.12±0.50 for varenicline: range 0–6 [t(14)=−4.3 p=0.001]. However, these ratings were in the mild range (average score of 2.12 on a scale with ratings up to 10), and no subjects vomited. Varenicline also significantly increased systolic [t(14)=−2.3 p<0.05] and diastolic blood pressure [t(14)=−3.4 p<0.01] and heart rate [t(14)=−2.8 p<0.05]. Finally, there were few effects of varenicline alone on eye movement responses, with the exception that varenicline produced shorter latencies to initiate anti-saccades [Drug*Time: F(2,24)=4.4, p<0.05; Varenicline vs. Placebo post-capsule, p<0.01], and increased the percent of accepted pro-saccades [Drug*Time: F(2,24)=3.9, p<0.05; Varenicline vs. Placebo post-capsule, p<0.05]. Given that participants were light smokers, urge to smoke ratings were low, and were not significantly affected by varenicline. The effects of varenicline did not differ with repeated exposure (all p>0.2).

Figure 2.

Effects of varenicline (2mg) upon subjective, cardiovascular and eye tracking measures before drinking. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between placebo and varenciline *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Effects of alcohol

Alcohol alone produced its expected effects. The 0.4 g/kg dose produced minimal eye movement or subjective effects, except for increased self-reported stimulation [Drink F(2,13)=6.1 p=0.013 ηp2=0.5; 0 vs. 0.4 g/kg t(14)=−3.2 p<0.01]. The 0.8 g/kg dose increased ratings of “feel drug” [Drink F(2,13)=5.5 p=0.018 ηp2=0.5; 0 vs. 0.8 g/kg t(14)=−3.4 p<0.01], “drug liking” [Drink F(2,13)=4.6 p=0.03 ηp2=0.4; 0 vs. 0.8 g/kg t(14)=−2.5 p=0.027], “feel high” [Drink F(2,13)=7.5 p=0.007 ηp2=0.5; 0 vs. 0.8 g/kg t(14)=−3.6 p<0.01], and urge to smoke [Drink F(2,13)=7.5 p=0.03 ηp2=0.4; 0 vs. 0.8 g/kg t(14)=−2.6 p=0.02]. Alcohol at 0.8 g/kg also impaired smooth pursuit gain [Drink*Time, F(4,48)=4.6, p<0.01; 0 vs. 0.8 g/kg, p<0.001], pro-saccade latency [Drink*Time, F(4,48)=5.1, p<0.01; 0 vs. 0.08 g/kg p<0.01], and anti-saccade latency [Drink*Time, F(4,48)=5.6, p<0.001; 0 vs. 0.8 g/kg p<0.01]. Alcohol did not significantly influence cardiovascular measures.

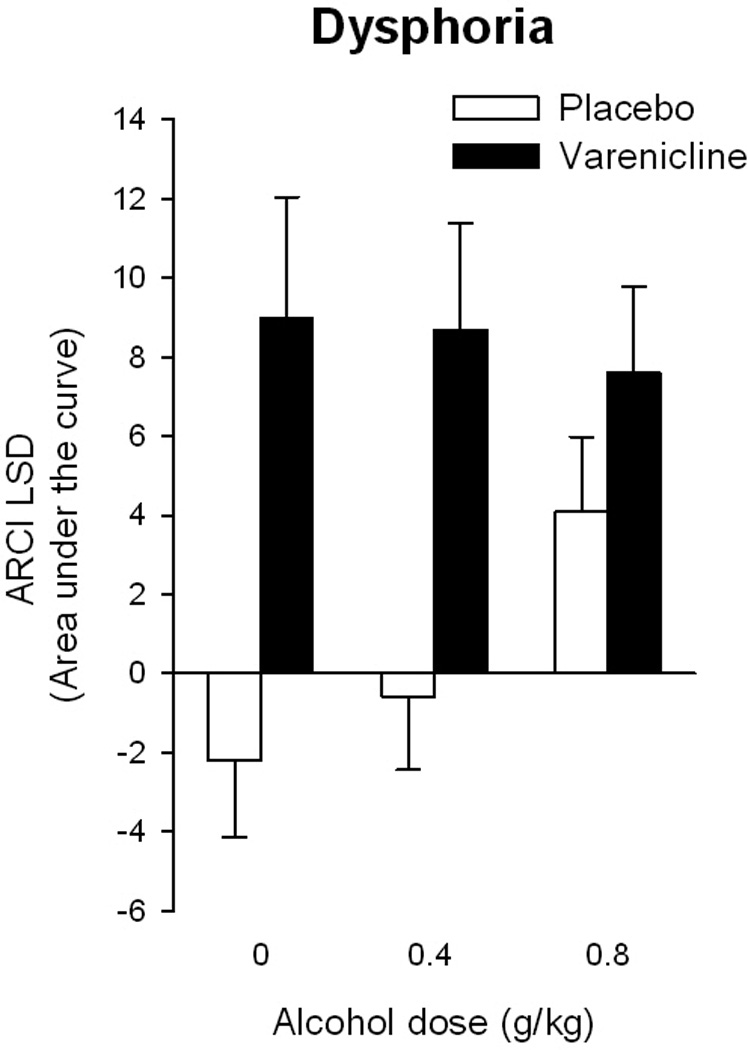

Varenicline Effects on Alcohol Responses

Varenicline significantly increased ratings of dysphoria (ARCI LSD) after consumption of both the placebo beverage and 0.4 mg/kg alcohol but not after 0.8g/kg alcohol [see Figure 3; Drug*Drink F(2,13)=4.5 p<0.05, ηp2=0.4] perhaps because 0.8g/kg alcohol increased ARCI LSD by itself. Varenicline also tended to attenuate ratings of drug liking after 0.4 g/kg alcohol [Drug*Drink F(2,13)=4.5 p<0.08, ηp2=0.3]. Varenicline did not alter alcohol-induced increases in urge to smoke [Drug*Drink F(2,13)=0.73 p=0.5, ηp2=0.1].

Figure 3.

Effects of varenicline (2mg) and alcohol upon negative mood. Bars represent the mean AUC ± SEM relative to pre-capsule baselines over the entire session.

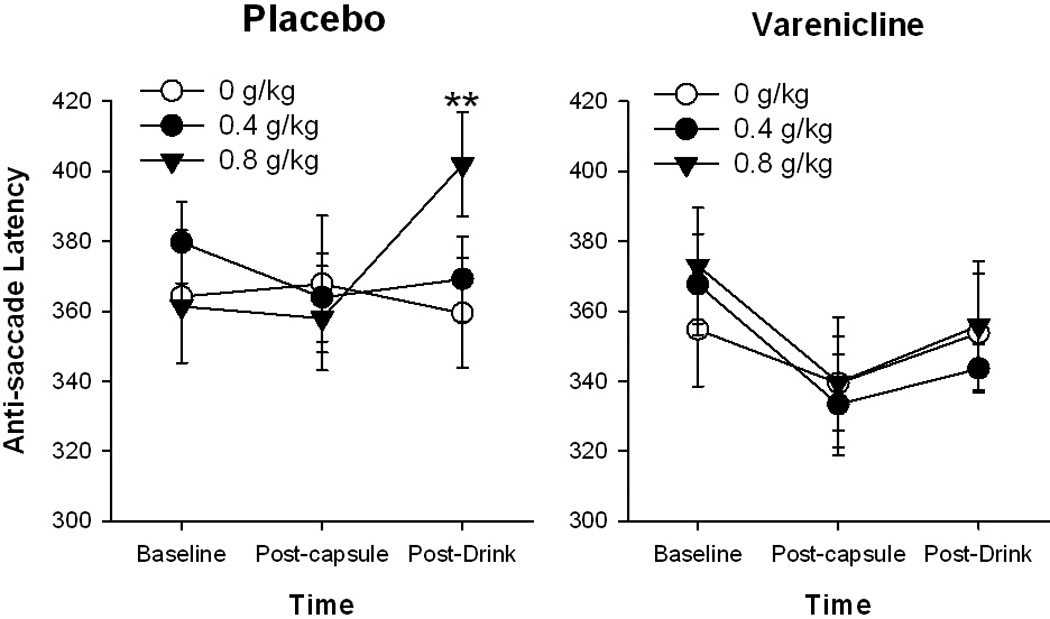

Varenicline attenuated some of the effects of alcohol (0.8 g/kg) on eye movements. It reduced the alcohol-related increase in latency to initiate anti-saccades [see Figure 4; Drug*Drink*Time, F(4, 48)=3.0 p<0.05; PL-0.8 vs. VAR-0.8, p<0.01] and it increased the percentage of accepted pro-saccades [Drug*Drink, F(2, 24)=3.7, p<0.05; PL-0.8 vs. VAR-0.8, p<0.05]. Finally, there was a significant interaction of varenicline and alcohol upon the percentage of accepted anti-saccades [Drug*Drink*Time, F(4, 48)=3.0 p<0.05] but post-hoc testing revealed this was driven by baseline differences and variability during the placebo drug session.

Figure 4.

Effects of varenicline and alcohol upon anti-saccade latency. Data points represent mean absolute scores ± SEM at repeated times during the sessions.

Varenicline Effects on Alcohol Responses After Controlling for Nausea

Because varenicline increased ratings of feeling nauseated, analyses were repeated controlling for nausea. Controlling for nausea did not influence the previous findings, and in fact strengthened the effects of varenicline upon negative mood after drinking i.e., increased ARCI LSD after 0 and 0.4g/kg alcohol only [Drug*Drink F(2,12)=5.4 p=0.02, ηp2=0.5].

Discussion

Varenicline has been shown to reduce alcohol consumption in mice, rats and humans (Fucito et al., 2011; Kamens et al, 2010a; McKee et al, 2009; Steensland et al, 2007; Wouda et al, 2011) and may do so by attenuating the positive subjective effects or potentiating the negative subjective effects of alcohol. In this study, we examined the influence of acute pre-treatment with varenicline (2mg) on subjective responses to alcohol in healthy social drinkers. We found that varenicline increased the aversive effects of alcohol as indexed by ARCI LSD, an effect that was observed even after controlling for varenicline-induced nausea. Thus, the mechanism by which varenicline may reduce alcohol drinking behaviors is by increasing aversive subjective effects after consumption, thereby opposing the rewarding efficacy of alcohol and the likelihood of continued drinking behavior.

Our finding that varenicline increased aversive subjective effects in a majority of subjects is consistent with both preclinical (Kamens et al., 2010b) and clinical studies (Fucito et al., 2011). Although our finding of increased negative mood (ARCI LSD) after varenicline was only marginally significant after correction for multiple testing, power estimates indicated a medium size effect. Varenicline did not increase dysphoria or somatic effects (ARCI LSD) after the 0.8 g/kg dose of alcohol, perhaps because these effects of alcohol, as measured by overall area under the curve response were already comparable to the effects of varenicline alone.

These findings extend current clinical knowledge of the efficacy and tolerability of varenicline among heavy drinkers to a non nicotine-dependent sample who frequently smoke in the context of alcohol drinking. McKee et al (2009) previously reported that varenicline decreased alcohol consumption, craving and positive subjective alcohol effects among heavier smokers than those enrolled in the current study. In addition, Fucito et al (2011) showed that 2 mg varenicline administered daily for 4 weeks increased sedative effects, decreased alcohol craving and resulted in fewer heavy drinking days among heavy smokers (a pack a day) undergoing treatment for smoking cessation. Thus, our findings demonstrate that while acute administration of varenicline mildly increased ratings of nausea, the drug was generally well-tolerated and may potentially reduce drinking among moderate to heavy drinkers who are also non-dependent social smokers. Furthermore, our data is consistent with animal and human studies showing that varenicline potentiates the sedative-hypnotic effects of alcohol (Fucito et al., 2011; Kamens et al., 2010b) and our results suggest that, in non-dependent smokers, the net effect of the nicotinic receptors activated by varenicline may be increased aversive subjective effects.

To our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the effects of varenicline on a sensitive and specific objective measure of alcohol’s impairing effects, such as eye tracking performance. Nicotine has been shown to improve anti-saccade performance (Larrison et al., 2004; Rycroft et al., 2006) and produce minimal effects on pro-saccade and smooth pursuit tasks (Reilly et al., 2008). In our study, varenicline decreased anti-saccade latency (i.e., like nicotine it improved anti-saccade performance) and also reduced alcohol-induced impairment of this measure. Varenicline did not, however, affect measures of pro-saccade (i.e., latency, velocity, or accuracy) or smooth pursuit (i.e., gain) performance. The anti-saccade task is a measure of response inhibition and volitional action that requires multiple cognitive processes, including sustained attention and working memory. Nicotine is known to enhance response inhibition, attention, and working memory (Heishman et al., 2010), which may contribute to its beneficial effect on anti-saccade performance. Thus, we may hypothesise that varenicline counteracts the detrimental cognitive effect of alcohol by increasing attention and working memory through its agonist action on nicotinic receptors, however more research will be needed in independent samples.

Our subjective and objective results suggest that there may be a specific interaction between varenicline and alcohol, possibly mediated via nicotinic receptors. Although varenicline produced some nausea which may have complicated the interpretation, its interactions with alcohol were evident even after controlling for the acute effects of the drug on nausea ratings. Nicotinic receptors containing the β2 subunit have been implicated in initial adverse subjective responses to alcohol in humans (Ehringer et al., 2007), the sedative-hypnotic effects of alcohol (Kamens et al., 2010b), in drug-induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens (Coe et al, 2005; Ericson et al, 2009; Rollema et al, 2007) and in varenicline-induced attenuation of alcohol consumption in animals (Butt et al, 2004 Hendrickson et al, 2010; Owens et al., 2003). However, others suggest that other receptor subtypes are more specific to varenicline’s effect on alcohol consumption (Chatterjee et al., 2011; Jerlhag et al, 2006). Thus, the interactive effects of varenicline and alcohol reported in this study are likely mediated by activity at nicotinic receptors, however our results do not provide definitive insights into the specific subtype involved.

There were several limitations to the current study. First, the relatively small sample size meant that interactions of medium effect size did not meet significance after correction for multiple testing. Thus, although the findings are in line with previous studies and some were consistent across similar measures e.g. BAES sedation and ARCI LSD both measure negative drug effects, they should be interpreted with caution. Second, the varenicline dosing profile used in our study is different to other clinical studies. Others have administered varenicline over a one-week pre-treatment phase with a titrated dosing schedule to reduce side effects prior to behavioral testing in the laboratory (Fucito et al., 2011; McKee et al., 2009) to avoid adverse effects such as nausea and vomiting (Faessel et al., 2006). Our study focused on single acute dose administration prior to behavioral testing and varenicline did increase ratings of nausea, but these were relatively mild and controlling for nausea did not alter the main findings of the study. However, any interactions between varenicline and alcohol which are mediated by changes in nicotinic receptor populations i.e., numbers or subunit composition, as a result of repeated dosing during pre-treatment would not have been measured as this was outside the scope of this study (Turner et al., 2011). Thirdly, our study utilized a group of non-dependent heavy drinking smokers and so the results may not generalize to other drinkers who are also nicotine dependent. Nevertheless, our findings demonstrate the potential clinical efficacy of varenicline amongst this particular subset of heavy drinkers who may not otherwise be considered for treatment with the drug. Finally, although we assessed “want more drug” after alcohol administration, we did not specifically examine “alcohol craving”as in prior research (McKee et al., 2009), therefore we are unable to make direction comparisons on craving per se and its possible association to increased aversive effects of alcohol.

In conclusion, the findings of this study support those of earlier investigations that demonstrate effects of varenicline upon subjective responses to alcohol. We have extended these findings by demonstrating in a group of light non-dependent smokers that even acute doses of varenicline increase the negative subjective effects of alcohol which occurs independently of increases in somatic complaints (i.e., nausea). Further, we report that varenicline offsets alcohol-induced impairments in eye movements, perhaps independently of its effect upon alcohol subjective responses. Thus, this study, combined with previous evidence, suggests that varenicline may reduce alcohol drinking behaviors among light smokers by increasing the negative subjective effects of a low dose of alcohol, thus reducing the likelihood of a drinking episode becoming a binge.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Yanwei Liao, Patrick McNamara, Lauren Greene, Hallie Kushner and Peter Ziegel who assisted with data collection and database management. This research was supported by NIDA (DA02812, HdW) and by NIAAA (R01-AA013746, ACK)

References

- Acheson A, Mahler SV, Chi H, De Wit H. Differential effects of nicotine on alcohol consumption in men and women. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;186:54–63. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0338-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA, American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychiatry. 4th ed. Washington DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bito-Onon JJ, Simms JA, Chatterjee S, Holgate J, Bartlett SE. Varenicline, a partial agonist at neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, reduces nicotine-induced increases in 20% ethanol operant self-administration in Sprague-Dawley rats. Addict Biol. 2011;16:440–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist O, Ericson M, Engel JA, Soderpalm B. Accumbal dopamine overflow after ethanol: localization of the antagonizing effect of mecamylamine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;334:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist O, Hernandez-Avila CA, Van Kirk J, Rose JE, Kranzler HR. Mecamylamine modifies the pharmacokinetics and reinforcing effects of alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:326–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomqvist O, Soderpalm B, Engel JA. Ethanol-induced locomotor activity: involvement of central nicotinic acetylcholine receptors? Brain Res Bull. 1992;29:173–178. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(92)90023-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt CM, King NM, Stitzel JA, Collins AC. Interaction of the nicotinic cholinergic system with ethanol withdrawal. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308:591–599. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.059758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S, Steensland P, Simms JA, Holgate J, Coe JW, Hurst RS, Shaffer CL, Lowe J, Rollema H, Bartlett SE. Partial agonists of the alpha3beta4* neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor reduce ethanol consumption and seeking in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:603–615. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi H, De Wit H. Mecamylamine attenuates the subjective stimulant-like effects of alcohol in social drinkers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:780–786. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000065435.12068.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A, Lindgren S, Brooks SP, Watson WP, Little HJ. Chronic infusion of nicotine can increase operant self-administration of alcohol. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41:108–117. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A, Little HJ. Interactions between low concentrations of ethanol and nicotine on firing rate of ventral tegmental dopamine neurones. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;75:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe JW, Brooks PR, Vetelino MG, Wirtz MC, Arnold EP, Huang J, Sands SB, Davis TI, Lebel LA, Fox CB, Shrikhande A, Heym JH, Schaeffer E, Rollema H, Lu Y, Mansbach RS, Chambers LK, Rovetti CC, Schulz DW, Tingley FD, 3rd, O'neill BT. Varenicline: an alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist for smoking cessation. J Med Chem. 2005;48:3474–3477. doi: 10.1021/jm050069n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TJ, De Fiebre CM. Alcohol's actions on neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29:179–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehringer MA, Clegg HV, Collins AC, Corley RP, Crowley T, Hewitt JK, Hopfer CJ, Krauter K, Lessem J, Rhee SH, Schlaepfer I, Smolen A, Stallings MC, Young SE, Zeiger JS. Association of the neuronal nicotinic receptor beta2 subunit gene (CHRNB2) with subjective responses to alcohol and nicotine. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:596–604. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ei-Fakahany EF, Miller ER, Abbassy MA, Eldefrawi AT, Eldefrawi ME. Alcohol modulation of drug binding to the channel sites of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1983;224:289–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson M, Lof E, Stomberg R, Soderpalm B. The smoking cessation medication varenicline attenuates alcohol and nicotine interactions in the rat mesolimbic dopamine system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:225–230. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esterlis I, Cosgrove KP, Petrakis IL, Mckee SA, Bois F, Krantzler E, Stiklus SM, Perry EB, Tamagnan GD, Seibyl JP, Krystal JH, Staley JK. SPECT imaging of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in nonsmoking heavy alcohol drinking individuals. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108:146–150. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faessel HM, Smith BJ, Gibbs MA, Gobey JS, Clark DJ, Burstein AH. Single-dose pharmacokinetics of varenicline, a selective nicotinic receptor partial agonist, in healthy smokers and nonsmokers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46:991–998. doi: 10.1177/0091270006290669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Luria R. Reliability, validity, and clinical application of the Visual Analogue Mood Scale. Psychol Med. 1973;3:479–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700054283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucito LM, Toll BA, Wu R, Romano DM, Tek E, O'malley SS. A preliminary investigation of varenicline for heavy drinking smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;215:655–663. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2160-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heishman SJ, Kleykamp BA, Singleton EG. Meta-analysis of the acute effects of nicotine and smoking on human performance. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;210:453–469. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1848-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson LM, Zhao-Shea R, Pang X, Gardner PD, Tapper AR. Activation of alpha4* nAChRs is necessary and sufficient for varenicline-induced reduction of alcohol consumption. J Neurosci. 2010;30:10169–10176. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2601-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerlhag E, Grotli M, Luthman K, Svensson L, Engel JA. Role of the subunit composition of central nicotinic acetylcholine receptors for the stimulatory and dopamine-enhancing effects of ethanol. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:486–493. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agl049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DH, Blomqvist O, Engel JA, Soderpalm B. Subchronic intermittent nicotine treatment enhances ethanol-induced locomotor stimulation and dopamine turnover in mice. Behav Pharmacol. 1995;6:203–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens HM, Andersen J, Picciotto MR. Modulation of ethanol consumption by genetic and pharmacological manipulation of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010a;208:613–626. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1759-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens HM, Andersen J, Picciotto MR. The nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist varenicline increases the ataxic and sedative-hypnotic effects of acute ethanol administration in C57BL/6J mice. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010b;34:2053–2060. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkawa H, Maruyama N, Fujimoto Y, Hasunuma T. Single- and multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of the selective nicotinic receptor partial agonist, varenicline, in healthy Japanese adult smokers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;51:527–537. doi: 10.1177/0091270010372388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, De Wit H, McNamara PJ, Cao D. Rewarding, stimulant, and sedative alcohol responses and relationship to future binge drinking. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:389–399. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouri EM, Mccarthy EM, Faust AH, Lukas SE. Pretreatment with transdermal nicotine enhances some of ethanol's acute effects in men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;75:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrison AL, Briand KA, Sereno AB. Nicotine improves antisaccade task performance without affecting prosaccades. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2004;19:409–419. doi: 10.1002/hup.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le AD, Wang A, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Shaham Y. Nicotine increases alcohol self-administration and reinstates alcohol seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;168:216–221. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1330-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Moreno JA, Trigo-Diaz JM, Rodriguez De Fonseca F, Gonzalez Cuevas G, Gomez De Heras R, Crespo Galan I, Navarro M. Nicotine in alcohol deprivation increases alcohol operant self-administration during reinstatement. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:1036–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Earleywine M, Musty RE, Perrine MW, Swift RM. Development and validation of the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:140–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WR, Sloan JW, Sapira JD, Jasinski DR. Physiologic, subjective, and behavioral effects of amphetamine, methamphetamine, ephedrine, phenmetrazine, and methylphenidate in man. Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 1971;12:245–258. doi: 10.1002/cpt1971122part1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mckee SA, Harrison EL, O'Malley SS, Krishnan-Sarin S, Shi J, Tetrault JM, Picciotto MR, Petrakis IL, Estevez N, Balchunas E. Varenicline reduces alcohol self-administration in heavy-drinking smokers. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mckee SA, Harrison EL, Shi J. Alcohol expectancy increases positive responses to cigarettes in young, escalating smokers. Psychopharmacology. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1831-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JC, Balogh SA, Mcclure-Begley TD, Butt CM, Labarca C, Lester HA, Picciotto MR, Wehner JM, Collins AC. Alpha 4 beta 2* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors modulate the effects of ethanol and nicotine on the acoustic startle response. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1867–1875. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000102700.72447.0F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penetar DM, Kouri EM, Mccarthy EM, Lilly MM, Peters EN, Juliano TM, Lukas SE. Nicotine pretreatment increases dysphoric effects of alcohol in luteal-phase female volunteers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:526–546. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6020526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potthoff AD, Ellison G, Nelson L. Ethanol intake increases during continuous administration of amphetamine and nicotine, but not several other drugs. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1983;18:489–493. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(83)90269-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly JL, Lencer R, Bishop JR, Keedy S, Sweeney JA. Pharmacological treatment effects on eye movement control. Brain Cogn. 2008;68:415–435. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche DJ, King AC. Alcohol impairment of saccadic and smooth pursuit eye movements: impact of risk factors for alcohol dependence. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;212:33–44. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1906-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollema H, Chambers LK, Coe JW, Glowa J, Hurst RS, Lebel LA, Lu Y, Mansbach RS, Mather RJ, Rovetti CC, Sands SB, Schaeffer E, Schulz DW, Tingley FD, 3rd, Williams KE. Pharmacological profile of the alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist varenicline, an effective smoking cessation aid. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:985–994. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rycroft N, Hutton SB, Rusted JM. The antisaccade task as an index of sustained goal activation in working memory: modulation by nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;188:521–529. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0455-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Office of Applied Statistics. Rockville, MD: 2007. National Survey on Drug Use and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Signs SA, Schechter MD. Nicotine-induced potentiation of ethanol discrimination. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1986;24:769–771. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(86)90589-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BR, Horan JT, Gaskin S, Amit Z. Exposure to nicotine enhances acquisition of ethanol drinking by laboratory rats in a limited access paradigm. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;142:408–412. doi: 10.1007/s002130050906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderpalm B, Ericson M, Olausson P, Blomqvist O, Engel JA. Nicotinic mechanisms involved in the dopamine activating and reinforcing properties of ethanol. Behav Brain Res. 2000;113:85–96. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steensland P, Simms JA, Holgate J, Richards JK, Bartlett SE. Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, selectively decreases ethanol consumption and seeking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12518–12523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705368104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutker PB, Tabakoff B, Goist KC, Jr, Randall CL. Acute alcohol intoxication, mood states and alcohol metabolism in women and men. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1983;18(Suppl 1):349–354. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(83)90198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiffany ST, Drobes DJ. The development and initial validation of a questionnaire on smoking urges. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1467–1476. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tizabi Y, Bai L, Copeland RL, Jr, Taylor RE. Combined effects of systemic alcohol and nicotine on dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens shell. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42:413–416. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JR, Castellano LM, Blendy JA. Parallel anxiolytic-like effects and upregulation of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors following chronic nicotine and varenicline. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13:41–46. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wouda JA, Riga D, De Vries W, Stegeman M, Van Mourik Y, Schetters D, Schoffelmeer AN, Pattij T, De Vries TJ. Varenicline attenuates cue-induced relapse to alcohol, but not nicotine seeking, while reducing inhibitory response control. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;216:267–277. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2213-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young EM, Mahler S, Chi H, De Wit H. Mecamylamine and ethanol preference in healthy volunteers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:58–65. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000150007.34702.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]