Abstract

Using antioxidants is an important means of treating lead poisoning. Prior in vivo studies showed marked differences between various chelator antioxidants in their ability to decrease both blood Pb(II) levels and oxidative stress resulting from lead poisoning. The comparative abilities of NAC and NACA to Pb(II) were studied in vitro, for the first time, to examine the role of the –OH/–NH2 functional group in antioxidant binding behavior. To assay the antioxidant-divalent metal interaction, the antioxidants were probed as solid surfaces, adsorbing Pb(II) onto them. Surface characterization was carried out using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis to quantify Pb(II) in the resulting adducts. XPS of the Pb 4f orbitals showed that more Pb(II) was chemically bound to NACA than NAC. In addition, the antioxidant surfaces were probed via point-of-zero charge (PZC) measurements of NAC and NACA were obtained to gain further insight into the Pb-NAC and Pb-NACA binding, showing that Coulombic interactions played a partial role facilitating complex formation. The data correlated well with solution analysis of metal-ligand complexation. UV-vis spectroscopy was used to probe complexation behavior. NACA was found to have the higher binding affinity as shown by free Pb(II) available in solution after complexation from HPLC data. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) was applied to delineate the structures of Pb-antioxidant complexes. Experimental results were further supported by density functional theory (DFT) calculations of supermolecular interaction energies (Einter) showing a greater interaction of Pb(II) with NACA than NAC.

Keywords: Lead poisoning, N-acetylcysteine, N-acetylcysteine amide, isoelectric point, density functional theory

INTRODUCTION

Lead poisoning is an ongoing world-wide concern. Lead accumulates in tissue [1] and has considerable adverse effects [2]. Lead, as a contaminant, emanates from a variety of sources, but mostly from drinking water [3]. The prevailing theory to explain the mechanism for lead toxicity is that Pb(II) oxidizes glutathione (GSH), resulting in the increase of free radicals. Since Pb(II) has a strong binding capacity for sulfhydryl proteins and enzymes, it will react with GSH to reduce the GSH-to-glutathione disulfide (GSSG) ratio, thereby causing GSH to lose its antioxidant abilities; instead, it functions as a scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS) [4]. Chelation therapy using antioxidants is aimed at removing the accumulated lead in the body.

N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) and N-acetyl cysteine amide (NACA) have been touted as promising therapeutic antioxidant chelator agents [5,6]. The thiol and hydroxyl (NAC) and thiol and amine (NACA) groups within these respective antioxidant molecules are known to serve as chelation sites to which divalent metal ions coordinate. The acetyl group, common to both molecules, has additional antioxidant potential due for the generation of glutathione [7]. NAC, as an antioxidant, has widely been investigated for use in treating an array of diseases, including liver failure [8–10], inflammation [11], nephropathy [12] and brain disorders [7,13–15]. NAC’s effectiveness is primarily attributed to its ability to reduce extracellular cystine to cysteine, and as a source of sulfhydryl groups [16]. NAC stimulates glutathione synthesis, enhances glutathione-S-transferase activity, promotes liver detoxification by inhibiting xenobiotic biotransformation, and is a powerful nucleophile capable of scavenging free radicals. Its use, however, has been limited by several drawbacks, including low membrane penetration and low systemic bioavailability. However, NACA, the amide form of NAC, the carboxyl group is neutralized which makes it more hydrophobic and membrane permeable. In fact, NAC is so hydrophilic that it is not able to cross blood brain barrier. NACA, the amide form of NAC, on the other hand, has a higher cellular permeability than NAC, and therefore is considered to be a noteworthy alternative therapeutic agent [16]. For this reason, NACA has been used to treat an array oxidative stress related diseases, for example the treatment of retinal degeneration and cataract formation [17,18], oxidative stress [19], and inflammatory lung injury [20].

Despite the interest in applying these molecules for therapeutic treatment, no work to date has been done to characterize the comparative binding behavior of these molecules to divalent Pb(II). Very little work has been done to characterize Pb-NAC binding [21], and none whatsoever has been done to characterize Pb-NACA binding. The difficulty in assaying the complexation to obtain binding constants stem from the fact that there are multiple species present when applying Job’s method, hampering solution phase analysis. This phenomenon was observed in our own experimental results (vide infra). Therefore, we have taken a surface assaying approach using photoelectron spectroscopy to quantify the amount of Pb(II) bound to the antioxidants. The thiol and hydroxyl (NAC) and thiol and amine (NACA) groups within these respective antioxidant molecules are known to serve as chelation sites to which divalent metal ions coordinate. The acetyl group, common to both molecules, has additional antioxidant potential due for the generation of glutathione [22]. The NAC and NACA molecules are ideal for comparative study since they differ in structure only by the –NH2/–OH functional group. Hence, differences in overall Pb(II) binding to the ligands are attributable to these groups (Figure 1) within the ligand structures. The relative abilities of NAC and NACA to coordinate aqueous Pb(II) were examined by probing these materials as solid surfaces to gain insight into influence of –NH2/–OH group for binding, followed by solution complexation analysis.

Figure 1.

Structural formulas for (A) N-acetyl cysteine (NAC); and (B) N-acetyl cysteine amide (NACA). Numeric assignments for each atom shown correspond to atomic positions used for DFT calculations. Hydrogen atoms attached to C(7) were assigned as H(11) and H(12).

EXPERIMENTAL

To assay the antioxidant-divalent metal interaction, NAC and NACA were probed as solid surfaces, adsorbing Pb(II) on them, respectively, followed by XPS analysis to quantify adsorbed Pb(II) in the adducts formed. Adsorption of Pb(II) from aqueous solution was performed onto NAC and NACA were performed, followed by electron spectroscopy. (Detailed descriptions for the preparation of NAC and NACA surfaces for X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and point-of-zero charge measurements, as well as instrumentation for solution complexation analysis and theoretical calculations are included in the Supporting Information section.) Surface characterization was complemented by solution complexation analysis. EDTA and cysteamine hydrochloride were used as standards for the Job’s method using UV-vis spectroscopy and HPLC experiments, respectively, for comparative studies between NAC and NACA. Stock solutions of lead acetate and antioxidants of the same concentrations were prepared and maintained at a temperature between 0–10°C to prevent antioxidant decomposition just prior to analysis. The volume ratio of Pb(II) and antioxidants were varied from 7:1 to 1:3, according to Job’s method [23]. When the volume ratio of two molecules is equal to their stoichiometric ratio, the amount of the complex formed would appear as a maximum in the UV-vis spectrum.

Point-of-zero charge (PZC) measurements of the NAC and NAC powders were conducted using the method described by Park and Regalbuto [24]. The PZC is defined as the aqueous solution pH value at which a solid surface has an electrostatically neutral charge. The antioxidant powders were used as the solid surface, incorporating them as supersaturated solutions, for the electrical double-layer model according to Gouy-Chapman theory.

The binding interactions of Pb(II) cation to NAC and NACA ligands were quantified using Density Functional Theory (DFT) [25] calculations using the Gaussian09 [26] suite of programs with Perdew-Wang 1991 exchange and correlation functionals [27,28] (Perdew, 1991; Perdew and Wang, 1992), a 6-311++G** basis set [29,30] for all ligand atoms, and a LANL2DZ basis set [31–33] for the Pb(II) cation, which uses effective core potentials (ECP) to describe core electrons. All calculations were performed using our own Linux Beowulf-type cluster equipped with 80 × 1.86 GHz Intel Xeon E5320 processors.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

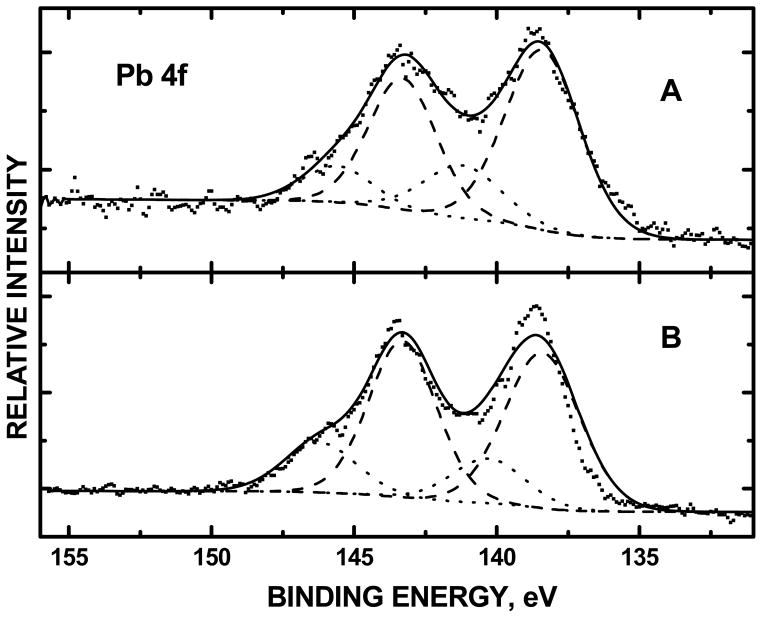

XPS of the Pb 4f core levels were used to quantify the amount of complexed versus uncomplexed Pb(II) based on devonvoluted peak areas denoting these two populations. High resolution narrow scans of uncomplexed Pb acetate, deposited on an ultrahigh vacuum cleaned foil sample holder and outgassed via turbomolecular pump, showed oxidation states with binding energy peak centers at 138.4 (3.1) and 143.3 (2.8) eV for the 4f7/2 and 4f5/2 photoelectrons, respectively [with full-width at half maxima (fwhm) in parentheses]. In curvefitting the XPS of Pb-antioxidant complexes (Figure 1), these binding energy peak centers and fwhm denoting uncomplexed Pb(II) were constrained (dashed-line peak envelopes). The remaining peak envelopes were attributed to Pb(II) chemically bound to the antioxidants (dotted-line peak envelopes). The Pb 4f orbital was deconvoluted by four peak envelopes. Peaks denoted complexed Pb(II) for Pb-NAC had binding energies at 140.3 (3.0) and 146.2 (3.0) eV. For the Pb-NACA complex, these oxidation states were observed at 141.2 (3.2) and 145.6 (2.9) eV. The Pb 4f chemical environments attributed to complexed and uncomplexed Pb(II), were quantified using their respective XPS integrated peak areas. The sum of XPS peak areas from complexed (dotted-line envelopes) Pb(II) was divided by the total sum peak areas of both complexed and uncomplexed Pb(II).

Integrated peak areas of chemisorbed (dotted-line peaks in Figure 2) Pb 4f of high resolution scans, performed in triplicate, showed 11.6±2.6%, 11.2±3.5% and 21.6±0.9% Pb(II) chemically bound to the EDTA, NAC and NACA antioxidants, respectively. The percentage of complexed Pb(II), shown by XPS indicated that NACA had a higher binding affinity to Pb (II) than both NAC and EDTA. For Pb-EDTA, 11.6% of the Pb(II) was complexed. For Pb-NAC, 10.3% of the Pb(II) was complexed. For Pb-NACA, 21.6% of the Pb(II) was complexed, approximately twice of that for Pb-EDTA and Pb-NAC. The trend, showing a greater degree of binding between Pb(II) with NACA than with NAC complements the HPLC data (vide infra).

Figure 2.

XPS Pb 4f spectra of (A) Pb-NAC; and (B) Pb-NACA. Dotted-line envelope denotes Pb(II) chemically bound to NAC while the dashed-lined envelope denoted uncomplexed Pb acetate.

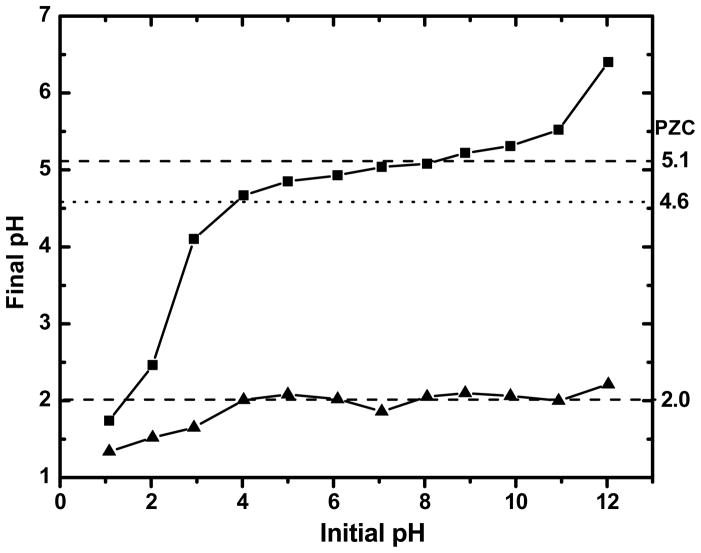

To gain insight into the role of Coulombic interactions in the binding between Pb(II) and the antioxidants, the isoelectric points of NAC and NACA were measured, treating them as solid surfaces in aqueous solution environments. Figure 3 shows plots of initial versus final pH values for both NAC and NACA. The measured PZC values, denoted by the plateaus, were found to be at pH = 2.0 and pH = 5.1 for NAC and NACA, respectively. The solution pH (= 4.6) at which Pb-NAC and Pb-NACA complexations were performed was below the PZC of NACA, but higher than that of NAC. At the pH at which complexation of Pb(II) to the antioxidants occurred, NAC would adopt an overall negative charge and would be more amenable to bind Pb(II) while NACA would adopt an overall positive charge and repel Pb(II) according to the electrical double layer theory. Hence, the measured PZCs of NAC and NACA indicate that Coulombic interactions to the –OH/–NH2 group only partially plays a role in governing binding between Pb(II) and the antioxidants. If this were the sole interaction, a greater binding between Pb and NAC than Pb and NACA would be predicted. The greater binding affinity of Pb(II) to NACA than to NAC, as observed by XPS and HPLC, is also incongruent with known electronegativities of the –OH and –NH2 functional groups, which in NAC and NACA differ in structure. Since –OH is the more electronegative than –NH2 based on the bond polarity index [34], a greater affinity of Pb(II) to NAC than Pb-NACA binding would have been predicted; however, both HPLC and XPS results showed the opposite trend. This finding indicates that it is the interplay of a variety of interatomic forces (not electrostatic ones only) between Pb(II) interacting with multiple atoms within the ligand that governs the binding strength of the antioxidant chelator molecule. This rationale is further supported by DFT calculations (vide infra).

Figure 3.

PZC Plots for NAC and NACA. Plateaus denote the observed PZC for NAC and NACA at 2.0 and 5.1, respectively. The pH at 4.6 (horizontal dotted line) denotes aqueous solution conditions at which Pb-NAC and Pb-NACA complexations occurred.

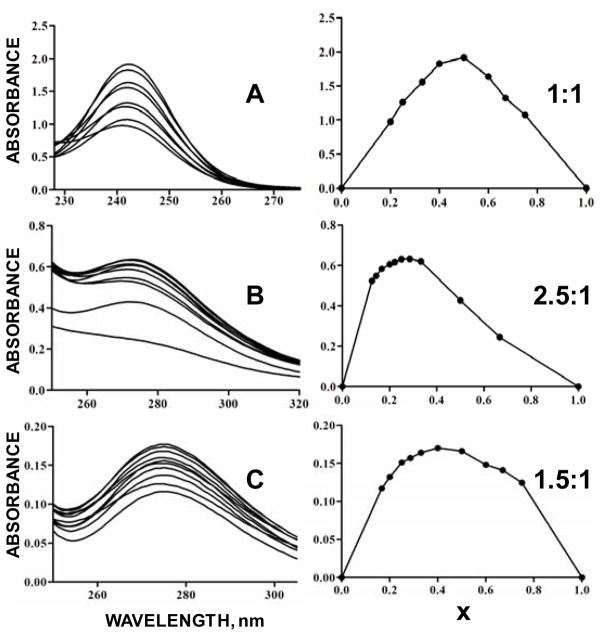

The left hand panel of Figures 4A, B and C shows raw UV-vis absorbance data of aqueous Pb(II) complexing with antioxidants EDTA, NAC and NACA, respectively. Actual concentrations of the Pb(II) substrate and antioxidant ligand to form the complexes for analysis are summarized in Table 1. The right-hand panel shows Pb-antioxidant complex concentrations (in arbitrary units) as a function mole fraction, x, determined by Job’s method analysis. The n/m ratio signifies the substrate-ligand complex, SmLn. The n and m variables that represent stoichiometric numbers for the ligand and substrate, respectively, were determined by the relation, , in which xmax is the mole fraction of maximum complex concentration. Figure 4A shows UV-vis spectra Pb-Na4EDTA complexation, showing a maximum absorbance at 246 nm. For the Pb-EDTA complex, xmax = 0.5, denoting a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio in good agreement with the literature [21] and validating the accuracy of our approach. Figure 4B shows the results for Pb-NAC complexation. The maximum absorbance of these spectra was observed at 275 nm. With xmax = 0.286, the stoichiometric ratio was 2.5:1 for Pb:NAC. Figure 4C show spectra for Pb-NACA complex formation. The wavelength of maximum absorption was the same as that for Pb-NAC complex formation, at 275 nm. With xmax = 0.400, the ratio Pb-to-NACA in the complex was found to be 1.5:1. Non-unity stoichiometries for Pb-NAC and Pb-NACA denoted more than one complex being formed as Pb(II) interacted with the NAC and NACA antioxidants; hence, bingind contant determination for these complexes were hampered. Substrate-to-ligand ratios in the complexes formed for Pb-NAC and Pb-NACA differed, giving further support that there is substantially dissimilar coordination behavior between Pb(II) and the two antioxidants.

Figure 4.

Raw UV-vis spectral data (left-hand panel) and Job’s method plots (right-hand panel) Pb-antioxidant complexes. (A) The wavelength of maximum aborbance (xmax) for Pb-EDTA was 246 nm with a metal-ligand stoichiometric ratio of 1:1; (B) the highest xmax for Pb-NAC was at 275 nm, with a 2.5:1 ratio; and (C) the xmax for Pb-NACA was at 275 nm with a 1.5:1 stoichiometric ratio.

TABLE 1.

Composition of Pb-antioxidant complexes obtained from ESI-MS

| Ligand | Mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) | Fragment | Percent abundance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Na4EDTA | 565.09 | [Na3-EDTA-Pb]+ | 100% |

| NAC | 369.77 | [Pb-NAC]+ | 76.5% |

| 591.82 | [Pb-NAC-Pb-H2O]+ | 14.5% | |

| 736.80 | [NAC-Pb-NAC-Pb]+ | 6.5% | |

| 942.73 | [Pb-NAC-Pb-NAC-Pb]+ | 2.5% | |

| NACA | 368.93 | [Pb-NACA-H]+ | 92.2% |

| 529.08 | [Pb-(NACA-NACA)-H]+ | 4.8% | |

| 575.04 | [Pb-NACA-Pb]+ | 3.0% |

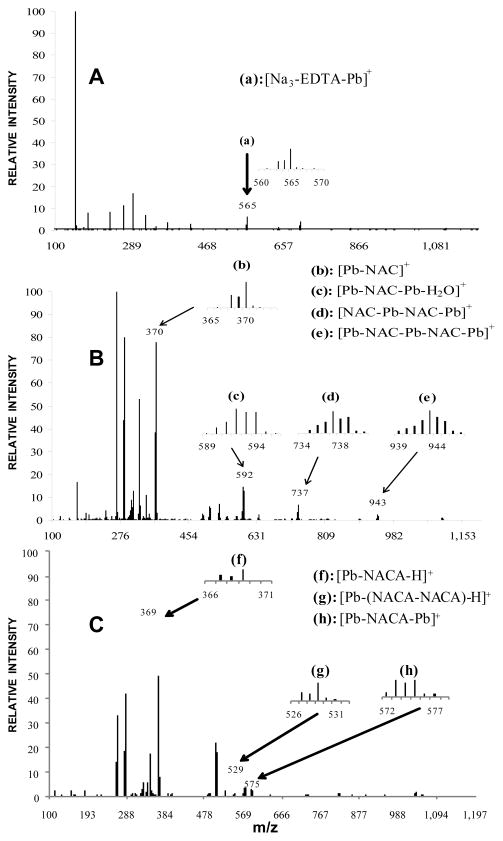

To gain insight into the structures of these complexes, ESI-MS was performed to detect and characterize the Pb-antioxidant mass spectral (MS) cracking fragments. Major complexes examined were those of the Pb-EDTA (used as a standard), Pb-NAC and Pb-NACA complexes. Figure 5A shows the signal emanating from [Na3EDTA-Pb]+ at 565.09 m/z, in agreement with the expected 1:1 ratio of the Pb-EDTA complex in the UV-vis experiments; this was the only predominant fragment observed [21]. Figure 5B shows the MS patterns of the Pb-NAC complex. Four MS fragments were detected, indicating that Pb(II) coordinated to NAC with metal-to-ligand ratios of 1:1, 2:1, 2:2, and 3:2. Masses were observed from [Pb-NAC]+ at m/z = 369.77 m/z, [Pb-NAC-Pb-H2O]+ at m/z = 591.82, [NAC-Pb-NAC-Pb]+ at m/z = 736.80, and [Pb-NAC-Pb-NAC-Pb]+ at m/z = 942.73; the percent mole fractions for all of these species were 76.5%, 14.5%, 6.5%, and 2.5%, respectively. In contrast to the Pb-NAC binding, only three major MS fragments were observed in the Pb-NACA complexation according to ESI-MS (Figure 5C). One signal emanated from [Pb-NACA-H]+ at m/z = 368.93. Two other peaks were observed at m/z = 529.08 and m/z = 575.04, denoting [Pb-(NACA-NACA)-H]+ and [Pb-NACA-Pb]+. Mole fraction percent compositions of [Pb-NACA-H]+, [Pb-(NACA-NACA)-H]+ and [Pb-NACA-Pb]+ for Pb-NAC complexation were 92.2%, 4.8% and 3.0%, respectively. In the cases of both Pb-NAC and Pb-NACA coordination interactions, the 1:1 substrate-to-ligand ratio was the most dominant stoichiometry for Pb-antioxidant coordination. Multiple Pb atom species detected by ESI-MS correlates with the high Pb-to-antioxidant ratios observed in the Job’s method data (Figures 4B and 4C). Although the Pb:antioxidant ratios could not be directly quantified from percent mass spectral abundances, the presence of higher Pb-to-ligand ratio fragments for Pb-NAC than Pb-NACA is consistent with observed n/m ratios in the Job’s method experiments.

Figure 5.

ESI-MS cracking pattern of (a) Pb-EDTA solution; (b) Pb-NAC; and (c) Pb-NACA.

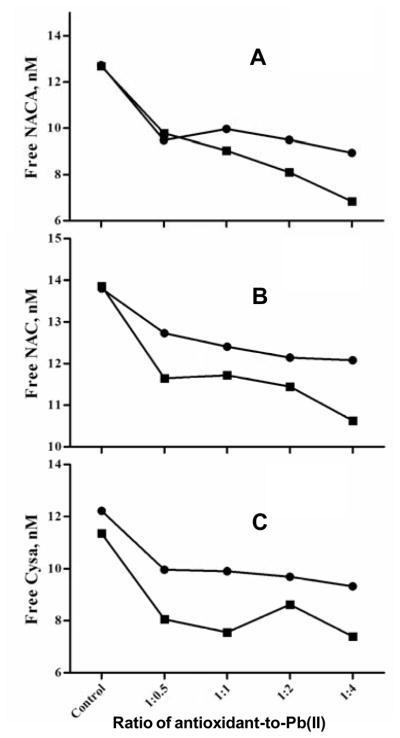

Cysteamine hydrochloride, NAC and NACA are mono-thiol antioxidants that contain a sulfur-hydrogen functional group. Chelating ability was determined and evaluated by quantifying the percentage of Pb(II) coordinated to the antioxidants, and HPLC was applied to determine the amount of antioxidants that had been coordinated. The retention times for NAC, NACA and cysteamine were 4.8, 5.2 and 17.2 min, respectively. Figure 6 shows the declining trend of cysteamine with an increase of Pb acetate concentration. With addition of Pb(II) acetate, the decrease in free cysteamine, NAC, and NACA in the substrate-ligand complexes became more pronounced (Table 2). At a 1:1 ratio of Pb:cysteamine, there was a 19.0% decrease in the free cysteamine concentration (compared to the control that contained only the ligand) with zero incubation time, and a 33.5% decline after a 1-hr incubation in 37.0°C water-bath. This decrease in free cysteamine is attributed to antioxidant decomposition at physiological temperature, which were also observed for NAC and NACA. At a 1:1 ratio of Pb-to-NAC, there was 10.1% decrease in free NAC in solution upon its interaction with Pb(II) at no incubation; after a 1-hr incubation, there was 15.5% decrease of free NAC. For the Pb-NACA complex, there was a 21.7% decrease in free NACA at zero incubation and a 28.7% decrease after a 1-hr incubation. HPLC data showed the relative amounts of free ligands complexing to Pb(II) in the following descending order: NAC > NACA > cysteamine. From the decrease in free antioxidant in solution, the data set indicated that a relatively greater proportion of NACA coordinated to Pb(II) as compared to NAC, i.e., NACA had a greater affinity for Pb(II) than NAC.

Figure 6.

HPLC data showing free antioxidants in solution with increasing Pb acetate concentrations added. The control group contained only the respective antioxidants at 12.5 nM concentration. Samples from which HPLC data were obtained were comprised of 12.5nM of antioxidant, with increasing Pb acetate concentrations of 6.25, 12.5, 25.0 and 50.0 nM, respectively. (A) Pb-NACA solutions; (B) Pb-NAC solutions; and (C) Pb-cysteamine hydrochloride solutions.

TABLE 2.

Percentage of Antioxidants Reacted with Pb(II) from HPLC

| Ligand:Pb(II) ratio

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand | 1:0.5 | 1:1 | 1:2 | 1:4 | ||||

| 0h | 1h | 0h | 1h | 0h | 1h | 0h | 1h | |

| NACA | 25.5% | 22.9% | 21.7% | 28.7% | 25.4% | 36.1% | 29.7% | 46.1% |

| NAC | 7.8% | 16.0% | 10.1% | 15.5% | 12.0% | 17.4% | 12.5% | 23.3% |

| Cysteamine | 18.5% | 29.1% | 19.0% | 33.5% | 20.7% | 24.1% | 23.7% | 34.8% |

In the DFT calculations, approximately two dozen possible metal-ligand structures for each coordination were calculated, with inter-atomic distances between the Pb(II) atom and the nearest (1NN), second (2NN), third (3NN), fourth (4NN) and fifth (5NN) nearest neighbor atoms reported. The presence of the –OH/–NH2 functional groups affected the optimized geometries of the divalent metal with ligands, and subsequently the overall Pb(II) interactions with multiple atoms within the antioxidant. There were a total of twenty four possible structures for NAC-Pb (Table S1) and twenty three possible structures for Pb-NACA (Tables S1 and S2, respectively, shown in the Supporting Information section). Interatomic distances between Pb(II) atom and the first five nearest neighbors are listed along with its intermolecular interaction binding energy (Einter), the energy needed to remove the metal atom from each cluster in the data tables. In addition to atomic level electrostatic interaction energies, the calculated stabilization energy denoted in Einter includes contributions from dispersion, induction and exchange repulsion energies between the Pb(II) and its nearest neighbors, which are not fully accounted for by the relative electronegativities of the –OH/–NH2 groups within the NAC and NACA molecules or isoelectric points of these ligands alone. The average Einter for Pb-NAC and Pb-NACA were found to be −4.7±1.2 eV and −5.1±1.5 eV, respectively (Tables S1 and S2), confirming that Pb(II) has a greater binding affinity for NACA than NAC.

Questions regarding the PZC data not only provided motivation for the DFT calculations, they (Figure 2) also reveal an additional insight into a property of NAC and NACA, influenced by the –OH/–NH2 functional group. The isoelectric point of NACA (PZC = 5.1) is closer to cytoplasm pH (= 7.2–7.4) than that of NAC (PZC = 2.0), hence making NACA more amenable to traverse cell membranes. Therefore, compared to NAC, NACA, in addition to having a greater binding affinity for Pb(II), may be the better ligand to treat lead poisoning due to a greater propensity to remove intracellular Pb(II) across membranes.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the solution complexation data correlated well with the surface analysis assays provided by XPS and isoelectric point measurements. UV-vis Job’s method data indicated multiple complexes present as Pb(II) coordinated with the NAC and NACA, respectively, which was supported by ESI-MS data. Fragmentation patterns for Pb-NAC and Pb-NACA showed four complexes in the Pb-NAC sample with metal-to-ligand ratios of 1:1, 2:1, 2:2, and 3:2. For Pb-NACA, metal-to-ligand ratios of 1:1, 2:1 and 2:2 were observed. Among both metal-to-ligand coordinations, the 1:1 ratio was the most abundant as observed by ESI-MS. The presence of fewer complexes in the Pb-NACA coordination as compared to Pb-NAC suggests a greater stability complex formation for Pb(II) interactions with NACA. Both HPLC and XPS of the Pb 4f core levels showed a greater population of chemically bound Pb(II) to the antioxidants than unbound Pb(II), i.e., unreacted Pb(II), for Pb-NACA than Pb-NAC. PZC measurements of NAC (2.0) and NACA (5.1), indicated that electrostatic effects from the –OH/–NH2 moieties alone (consistent with the known polarizabilities of these groups) only partially accounted for the greater Pb-NACA binding, compared to Pb-NAC. These in vitro findings in this study will serve as an important benchmark for engineering improved therapeutic antioxidant chelators for the treatment of lead poisoning. DFT calculations of the Einter binding energies showed that the interplay of (1) electrostatic interactions, (2) dispersion, (3) induction and (4) exchange repulsion energies accompanying the optimized geometries of the metal-ligand structures governed the observed, enhanced Pb-NACA binding. Regarding the precise mechanism governing Pb-antioxidant binding, the precise role of each of these contributions for metal-ligand binding is under currently under investigation in a more rigorous theoretical calculation study. Our current findings suggest that the collective contributions of (2), (3) and (4) is more substantial as compared to (1) alone.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Calculated clusters formed by Pb(II) coordination to all possible optimized geometries (total of 24) of NAC. Yellow, blue, white, red and black balls denote sulfur, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen and lead atoms, respectively. Clusters without lines interconnecting the Pb atom with those of the ligand signify distances > 2.5 Å.

Figure S2. Calculated clusters formed by Pb(II) coordination to all possible optimized geometries (total of 23) of NACA. Yellow, blue, white, red and black balls denote sulfur, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen and lead atoms, respectively. Clusters without lines interconnecting the Pb atom with those of the ligand signify distances > 2.5 Å.

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored by the National Institutes of Health Academic Research Enhancement Award Grant (2R15ES012167-02A1) and in part by the Faculty Research and Creative Activity Committee (FRCAC) of Middle Tennessee State University. We thank Dr. Nathan Leigh for the use of the mass spectrometry facility at the University of Missouri-Columbia and helpful discussions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hu H, Rabinowitz M, Smith D. Bone as a biological marker in epidemiologic studies of chronic toxicity: conceptual diagrams. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106:1–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.981061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mudipalli A. Lead hepatotoxicity and potential health effects. Indian J Med Res. 2007;126:518–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patrick L. Lead toxicity, A review of the literature. Part I: exposure, evaluation, and treatment. Altern Med Rev. 2006;11:2–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gurer H, Ercal N. Can antioxidants be beneficial in the treatment of lead poisoning? Free Rad Biol Med. 2000;29:927–945. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00413-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aykin-Burns N, Franklin EA, Ercal N. Effects of N-Acetylcysteine on lead-exposed PC-12 cells. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 2005;49:119–123. doi: 10.1007/s00244-004-0025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penugonda S, Mare S, Lutz P, Banks WA, Ercal N. Potentiation of lead-induced cell death in PC12 cells by glutamate: Protection by N-acetylcysteine amide (NACA), a novel thiol antioxidant. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;216:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berk M, Dean O, Cotton SM, Gama CS, Kapczinski F, Fernandes BS, Kohlmann K, Jeavons S, Hewitt K, Allwang C, Cobb H, Bush AI, Schapkaitz I, Dodd S, Malhi GS. The efficacy of N-acetyl cysteine as a adjunctive treatment in biopolar depression: an open label trial. J Affect Disord. 2011;135:389–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morsy MA, Abdalla AM, Mahmoud AM, Abdelwahab SA, Mahmoud ME. Protective effects of curcumain, alpha-lipoic acid, and N-acetylcysteine against carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fiobrosis in rats. J Physiol Biochem. 2011;10 doi: 10.1007/s13105-011-0116-0. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odewumi CO, Badisa VL, Le UT, Latinwo LM, Ikediobi CO, Badisa RB, Darling-Reed SF. Protective effects of N-acetylcysteine against cadmium-induced damage in cultured rat normal liver cells. Int J Mol Med. 2011;27:243–248. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2010.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sotelo N, de los Angeles Duranzo M, Gonzalez A, Dhanakotti N. Early treatment with N-acetylcysteine in children with acute liver failure secondary to hepatitis A. Ann Hepatol. 2009;8:353–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palacio JR, Markert UR, Martínez P. Anti-inflammatory properties of N-acetylcysteine on lipopolysaccharide-activated macrophages. Inflamm Res. 2011;60:695–704. doi: 10.1007/s00011-011-0323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Awal A, Ahsan SA, Siddique MA, Banerjee S, Hasan MI, Saman SM, Arzu J, Subedi B. Effect of hydration with or without N-acetylcysteine on contrast induced nephrophaty in patients undergoing coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention. Mymensing Med J. 2011;20:264–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson RA, Joshi G, Huang Q, Sultana R, Baker AS, Cai J, Pierce W, St Clair DK, Markesbery WR, Butterfield DA. Proteomic analysis of brain proteins in APP/PS-1 human double mutant knock-in mice with increasing amyloid β-peptide deposition: insights into the effects of in vivo treatment with N-acetylcysteine as a potntial therapeutic intervention in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Proteomics. 2011;11:4243–4256. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jain S, Kumar CH, Suranagi UD, Mediratta PK. Protective effect of N-acetylcysteine on bisphenol A-induced cognitive dysfunction and oxidative stress in rats. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:1404–1409. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berman AE, Chan WY, Brennan AM, Reyes RC, Adler BL, Suh SW, Kauppinen TM, Edling Y, Swanson RA. N-acetylcysteine prevents loss of dopaminergic neurons in the EACC1 −/− mouse. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:509–520. doi: 10.1002/ana.22162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whillier S, Raftos JE, Chapman B, Kuchel PW. Role of N-acetylcysteine and cystine in glutathione synthesis in human erythrocytes. Redox Rep. 2009;14:115–124. doi: 10.1179/135100009X392539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carey JW, Pinarci EY, Penugonda S, Karacal H, Ercal N. In vivo inhibition of 1-buthionine-(S,R)-sulfoximine-induced cataracts by a novel antioxidant, N-acetylcysteine amide. Free Rad Biol Med. 2011;50:722–729. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schimel AM, Abraham L, Cox D, Sene A, Kraus C, Dace DS, Ercal N, Apte RS. N-acetyl cysteine amide (NACA) prevents retinal degeneration by up-regulating reduced glutathione production and reversing lipid peroxidation. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:2032–2043. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penugonda S, Ercal N. Comparative evaluation of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and N-acetylcysteine amide (NACA) on glutamate and lead-induced toxicity in CD-1 mice. Toxicol Lett. 2011;201:2032–2043. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee KS, Kim SRl, Park HS, Park SJ, Min KH, Lee KY, Choe YH, Hong SH, Han HJ, Le YR, Kim JS, Atlas D, Lee YC. A novel thiol compound, N-acetylcysteine amide, attenuates allergic airway disease by regulating activation of NF-kappaB and hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha. Exp Mol Med. 2007;39:755–759. doi: 10.1038/emm.2007.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta VK, Jain AK, Maheshwari G. Synthesis, characterization and Pb(II) ion selectivity of N, N′-bis(2-hydroxyl-1-napthalene)-2,6-pyridiamine(BHNPD) Int J Electrochem Sci. 2007;2:102–112. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flora SJS. Structural, chemical and biological aspects of antioxidants for strategies against metal and metalloid exposure. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2009;1:191–206. doi: 10.4161/oxim.2.4.9112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacCarthy P, Mark HB., Jr An evaluation of Job’s method of continuous variations as applied soil organic matter-metal ion interactions. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1976;40:267–276. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park J, Regalbuto JR. A Simple, Accurate Determination of Oxide PZC and the Strong Buffering Effect of Oxide Surfaces at Incipient Wetness. J Colloid Interface Sci. 1995;175:239–252. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hohenberg P, Kohn W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys Rev. 1964;136:B864–B871. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani V, Barone V, Menakatsuji H, Mennucci B, Petersson GA, Caricato M, Li X, Hratchian HP, Izmaylov AF, Bloino J, Zheng G, Sonnenberg JL, Hada M, Ehara M, Toyota K, Fukuda R, Hasagawa J, Ishida M, Nakajima T, Honda Y, Kitao O, Nakai H, Vreven T, Montgomery JA, Jr, Peralta JE, Ogliaro F, Bearpark M, Heyd JJ, Brothers E, Kudin KN, Staroverov VN, Kobayashi R, Normand J, Raghavachari K, Rendell A, Burant JC, Iyengar SS, Tomasi J, Cossi M, Rega N, Millam JM, Klene M, Knox JE, Cross JB, Bakken V, Adamo C, Jaramillo J, Gomperts R, Stratmann RE, Yazyev O, Austin AJ, Cammi R, Pomelli C, Ochterski JW, Martin RL, Morokuma K, Zakrzewski VG, Voth GA, Salvador P, Dannenberg JJ, Dapprich S, Daniels AD, Farkas Ö, Foresman JB, Ortiz JV, Cioslowski J, Fox DJ. Gaussian, Inc. CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perdew JP. In: Electronic Structure of Solids ‘91. Ziesche P, Eschrig H, editors. Akademie Verlag; Berlin: 1991. p. 11. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perdew JP, Wang Y. Accurate and simple analytic representation of the electron gas correlation energy. Phys Rev B. 1992;45:13244–13249. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.45.13244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raghavachari K, Binkley JS, Seeger R, Pople JA. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. 20. Basis set for correlated wave-functions. J Chem Phys. 1980;72:650–654. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McLean AD, Chandler GS. Contracted Gaussian-basis sets for molecular calculations. 1. 2nd row atoms, Z=11–18. J Chem Phys. 1980;72:5639–5648. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hay PJ, Wadt WR. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations - potentials for the transition-metal atoms Sc to Hg. J Chem Phys. 1985;82:270–283. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hay PJ, Wadt WR. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations - potentials for K to Au including the outermost core orbitals. J Chem Phys. 1985;82:299–310. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wadt WR, Hay PJ. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations: potentials for main group elements Na to Bi. J Chem Phys. 1985;82:284–298. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reed LH, Allen LC. Bond polarity index: application to group electronegativity. J Phys Chem. 1992;96:157–164. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Calculated clusters formed by Pb(II) coordination to all possible optimized geometries (total of 24) of NAC. Yellow, blue, white, red and black balls denote sulfur, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen and lead atoms, respectively. Clusters without lines interconnecting the Pb atom with those of the ligand signify distances > 2.5 Å.

Figure S2. Calculated clusters formed by Pb(II) coordination to all possible optimized geometries (total of 23) of NACA. Yellow, blue, white, red and black balls denote sulfur, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen and lead atoms, respectively. Clusters without lines interconnecting the Pb atom with those of the ligand signify distances > 2.5 Å.