Abstract

Ornithine carbamoyltransferase (OTC) deficiency is a urea cycle disorder that causes the accumulation of ammonia, which can lead to encephalopathy. Adults presenting with hyperammonemia who are subsequently diagnosed with urea cycle disorders are rare. Herein, we report a case of a late-onset OTC deficient patient who was successfully treated with arginine, benzoate and hemodialysis. A 59-yr-old man was admitted to our hospital with progressive lethargy and confusion. Although hyperammonemia was suspected as the cause of the patient's mental changes, there was no evidence of chronic liver disease. A plasma amino acid and urine organic acid analysis revealed OTC deficiency. Despite the administration of a lactulose enema, the patient's serum ammonia level increased and he remained confused, leading us to initiate acute hemodialysis. After treatment with arginine, sodium benzoate and hemodialysis, the patient's serum ammonia level stabilized and his mental status returned to normal.

Keywords: Ornithine Carbamoyltransferase Deficiency, Urea Cycle Disorder, Hyperammonemia, Hemodialysis

INTRODUCTION

The amino acid products of endogenous and exogenous protein digestion are degraded by hepatic transamination and oxidative deamination to produce ammonia. Ammonia is then converted to urea via the five enzymes of the urea cycle (carbamoyl phosphate synthetase, ornithine carbamoyltransferase (OTC), argininosuccinic acid synthetase, argininosuccinase, and arginase), and excreted by the kidneys (1). Any disruption to this nitrogen excretion pathway has the potential to cause hyperammonemia and clinical encephalopathy.

The most common genetic disorder of the urea cycle is a deficiency in OTC (2). OTC deficiency is heterogeneous in its presentation (3), but its symptoms are induced by hyperammonemia caused by the accumulation of precursors of urea, primarily ammonia and glutamine (1). The presentation of severe hyperammonemia caused by OTC deficiency varies with the age of the patient. In infants, hyperammonemia is associated with lethargy, poor sucking response, vomiting, hypotonia, and seizures (4). In adults, although disruption of the urea cycle is usually a result of liver disease (cirrhosis) or chemotherapy rather than a genetic defect, partial or late-onset OTC deficiency can result from residual enzyme activity associated with peripheral mutations in the OTC gene. Its phenotypes are diverse, ranging from severe to apparently asymptomatic (5).

Here we describe a case of late-onset OTC deficiency presenting as severe acute hyperammonemia with coma, and successful treatment with arginine, benzoate and hemodialysis.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 59-yr-old man was admitted to our hospital because he had exhibited progressive lethargy and confusion since the early morning. He had often complained of fatigue over the previous 3 months. Three days prior to presentation, he had eaten a large amount of dog meat at a party, become nauseated, and vomited. The next day, he had eaten chicken and freshwater snails, had again become nauseated, and developed severe vomiting. On the day of admission, he failed to arise at his normal time and exhibited inappropriate behavior and drowsiness.

During his childhood, the patient had suffered recurrent abdominal pain and periodic episodes of convulsions, but he had not experienced any seizures in adulthood. On examination, the patient was in a semi-coma; his Glasgow Coma Scale score was 10/15, and he was disoriented in time, place, and person. His vital signs were stable, with a blood pressure of 150/80 mmHg, pulse rate of 84/min, respiratory rate of 24/min, and body temperature of 36℃. Laboratory investigations showed that he had hyperammonemia (143.8 mM), elevated liver enzymes (alanine aminotransferase, 179 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase, 91 U/L), a total bilirubin level of 1.91 mg/dL, and a blood glucose level of 106 mg/dL. His blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine levels were 17.7 mg/dL and 1.01 mg/dL, respectively. Blood analysis revealed mild leukocytosis (10.41 × 103 leukocytes/µL) and a normal hemoglobin level, platelet count, and clotting profile. Serum electrolyte analysis showed mild hypernatremia (149 mEq sodium/L), but serum potassium and chloride levels were within normal range. Results of a toxicology screen were normal.

Further investigations revealed no evidence of gastrointestinal bleeding, and computed tomography (CT) and diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging revealed no brain lesions. Abdominal CT imaging did not show any abnormality. The cerebrospinal fluid was normal upon examination.

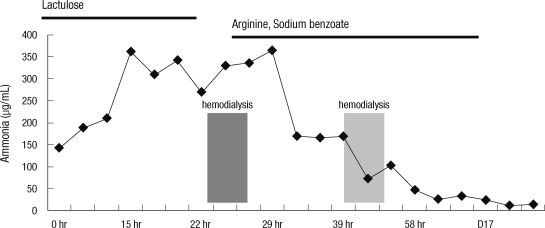

Although hyperammonemia was suspected as the cause of the patient's mental changes, there was no evidence of chronic liver disease. Despite the administration of a lactulose enema, the patient's serum ammonia level increased to 370 mM and he remained confused, leading us to initiate acute hemodialysis. During the procedure, the patient had a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, for which 1 mg of lorazepam was administered intravenously. The seizure subsided, but the patient continued to move convulsively, leading to several additional injections of intravenous lorazepam. A diagnosis of nonconvulsive status epilepticus was made, and the antiepileptic drug levetiracetam was administered.

After the initial session of hemodialysis, the patient's serum ammonia level had decreased to 170 mM, but it soon rose to 228 mM. Plasma and urine amino acid analysis and urine organic acid quantitation were performed. Under suspicion of a urea cycle disorder, arginine (3 g) and sodium benzoate (3 g) were administered via nasogastric tube every 4-6 hr. Dextrose solution (10%) was supplied intravenously, and a protein-free formula was supplied via a feeding tube.

By the morning of the next day, the patient's serum ammonia level had decreased to 36 mM. However, because it rose to 107 mM by the afternoon, and the patient was still semi-comatose, hemodialysis was performed one more time. At that time, an electroencephalogram did not show any signs of epileptic discharge.

After the second hemodialysis session, the patient's serum ammonia level stabilized at less than 30 mM. A plasma amino acids analysis revealed elevated ornithine (196 µM; normal 19-81 µM), decreased citrulline (3 µM; normal 19-62 µM), and elevated glutamine and lysine. Urine organic acids analysis revealed highly elevated urinary orotic acid (603.5 mg/mg creatinine) and a mild urinary uracil peak. No liver biopsy or genetic analysis was performed.

The accumulated evidence led to a diagnosis of late-onset ornithine carbamoyltransferase deficiency. After 5 days, the patient's mental status returned to normal. He continued to receive sodium benzoate (3 g) and arginine (3 g) three times daily. The protein-free formula, which was administered continuously, was gradually changed to increase the dietary protein without a significant rise in serum ammonia levels (Fig. 1). The patient was discharged home after 2 weeks with instructions to continue the medication and formula. His family received special counseling on diet and emergency management before his discharge.

Fig. 1.

Effect of arginine, sodium benzoate and hemodialysis in a late-onset ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency.

DISCUSSION

The ornithine carbamoyltransferase (OTC) gene is encoded on the X chromosome and is expressed in the mitochondrial matrix of the small intestine and liver, where it catalyzes the synthesis of citrulline from carbamoyl phosphate and ornithine (1). OTC deficiency has an estimated incidence of 1 in 14,000 and is the only urea cycle disorder that is X-linked (1). Recent research on the biochemical and molecular bases of OTC deficiency by Tuchman et al. (6) revealed a wide spectrum of genetic defects resulting in different phenotypes. Mutations predicted to abolish all enzyme activity were found in the neonatal onset group, while mutations causing partial or varying enzyme deficiency were found in the late onset group (7). Patients who were asymptomatic until much later in life were almost always heterozygotes and symptom onset coincided with a precipitating factor such as infection, trauma, sodium valproate, surgery, childbirth, physiological stress or, as in our patient, excess protein intake (8, 9).

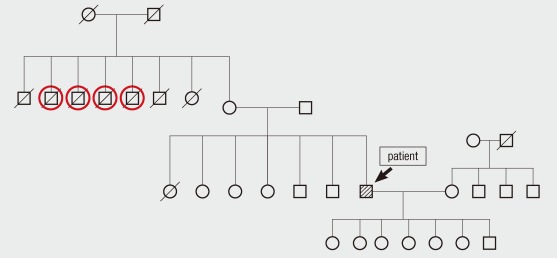

A diagnosis of OTC deficiency is confirmed when plasma amino acid analysis reveals elevated glutamine and alanine levels and a decreased citrulline level, and orotic acid and uridine are found in the urine (1). The diagnosis can be followed up by liver biopsy to measure OTC enzyme activity and mutation analysis. The measurement of urinary orotidine excretion after allopurinol administration can be used as a simple and reliable test to detect carriers (10). DNA analysis of the affected gene is the most reliable method for detecting the carrier state of females and for making a prenatal diagnosis in a family with a positive family history (11). In our patient, the amino acid analyses of his plasma and urine were consistent with OTC deficiency, allowing us to explain the etiology of his hyperammonemia and coma. Although a discussion of his family medical history eventually revealed that four uncles of the patient had died of unknown causes after eating a large amount of meat (Fig. 2), no genetic analyses were performed.

Fig. 2.

The pedigree of patient with late-onset OTC deficiency. Four uncles of the patient had died of unknown causes after eating a large amount of meat (red circles). The other uncles and aunt of the patient had died of old age.

The therapeutic principles for management of OTC deficiency include minimizing endogenous ammonia production, protein catabolism, and nitrogen intake; administration of urea cycle substrates that are lacking as a consequence of the enzymatic defect; and administration of compounds that facilitate the removal of ammonia through alternative pathways (1). By activating N-acetylglutamate synthetase, arginine activates the urea cycle (12). Oral supplementation or intravenous infusion is recommended. Benzoate and phenylacetate, by conjugating with glycine and glutamine, respectively, remove excess nitrogen via alternative pathways (8). There are no definite guidelines as to when to initiate dialysis in a patient with hyperammonemia. However, if the blood ammonia level is more than three to four times the upper limit of normal or is increasing quickly, and/or if the patient is encephalopathic, high-efficiency intermittent hemodialysis should be considered (13). For the encephalopathic patient with hyperammonemia, rapid initiation of dialysis is critical to minimize the brain damage resulting from continued exposure to elevated blood ammonia. The rapid removal of ammonia by hemodialysis is not associated with disequilibrium syndrome because ammonia is a gas and not osmotically active (14). After a normal blood ammonia level is achieved, dialysis can be stopped, and the patient can be maintained on urea cycle medications.

This case illustrates the under-recognized fact that late-onset OTC deficiency can occur at any age; our patient was 54 yr old. His late-onset OTC deficiency was successfully treated with hemodialysis and arginine and benzoate administration. Unexplained neurological symptoms in a patient with no history of liver disease should raise the suspicion of a urea cycle disorder, as many cases will respond to treatment with a favorable outcome.

References

- 1.Brusilow SW, Maestri NE. Urea cycle disorders: diagnosis, pathophysiology, and therapy. Adv Pediatr. 1996;43:127–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Applegarth DA, Toone JR, Lowry RB. Incidence of inborn errors of metabolism in British Columbia, 1969-1996. Pediatrics. 2000;105:e10. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.1.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuchman M, Jaleel N, Morizono H, Sheehy L, Lynch MG. Mutations and polymorphisms in the human ornithine transcarbamylase gene. Hum Mutat. 2002;19:93–107. doi: 10.1002/humu.10035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang ES, Snodgrass PJ, Gerald PS. Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency in the newborn infant. J Pediatr. 1973;82:642–649. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(73)80590-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCullough BA, Yudkoff M, Batshaw ML, Wilson JM, Raper SE, Tuchman M. Genotype spectrum of ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency: correlation with the clinical and biochemical phenotype. Am J Med Genet. 2000;93:313–319. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20000814)93:4<313::aid-ajmg11>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuchman M, McCullough BA, Yudkoff M. The molecular basis of ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. Eur J Pediatr. 2000;159:S196–S198. doi: 10.1007/pl00014402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuchman M, Morizono H, Rajagopal BS, Plante RJ, Allewell NM. The biochemical and molecular spectrum of ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1998;21:40–58. doi: 10.1023/a:1005353407220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon N. Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency: a urea cycle defect. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2003;7:115–121. doi: 10.1016/s1090-3798(03)00040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ellaway CJ, Bennetts B, Tuck RR, Wilcken B. Clumsiness, confusion, coma, and valproate. Lancet. 1999;353:1408. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)01433-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hauser ER, Finkelstein JE, Valle D, Brusilow SW. Allopurinol-induced orotidinuria. A test for mutations at the ornithine carbamoyltransferase locus in women. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:1641–1645. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199006073222305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bisanzi S, Morrone A, Donati MA, Pasquini E, Spada M, Strisciuglio P, Parenti G, Parini R, Papadia F, Zammarchi E. Genetic analysis in nine unrelated italian patients affected by OTC deficiency: detection of novel mutations in the OTC gene. Mol Genet Metab. 2002;76:137–144. doi: 10.1016/s1096-7192(02)00028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brusilow SW. Arginine, an indispensable amino acid for patients with inborn errors of urea synthesis. J Clin Invest. 1984;74:2144–2148. doi: 10.1172/JCI111640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathias RS, Kostiner D, Packman S. Hyperammonemia in urea cycle disorders: role of the nephrologist. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:1069–1080. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(05)80026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiegand C, Thompson T, Bock GH, Mathis RK, Kjellstrand CM, Mauer SM. The management of life-threatening hyperammonemia: a comparison of several therapeutic modalities. J Pediatr. 1980;96:142–144. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(80)80352-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]