Abstract

Abdominal cocoon, the idiopathic form of sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis, is a rare condition of unknown etiology that results in an intestinal obstruction due to total or partial encapsulation of the small bowel by a fibrocollagenous membrane. Preoperative diagnosis requires a high index of clinical suspicion. The early clinical features are nonspecific, are often not recognized and it is difficult to make a definite pre-operative diagnosis. Clinical suspicion may be generated by the recurrent episodes of small intestinal obstruction combined with relevant imaging findings and lack of other plausible etiologies. The radiological diagnosis of abdominal cocoon may now be confidently made on computed tomography scan. Surgery is important in the management of this disease. Careful dissection and excision of the thick sac with the release of the small intestine leads to complete recovery in the vast majority of cases.

Keywords: Peritonitis, Sclerosis, Encapsulate, Intestinal obstruction, Computed tomography scan, Surgery

INTRODUCTION

Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (SEP) is a rare condition of unknown etiology. It is characterized by a thick grayish-white fibrotic membrane, partially or totally encasing the small bowel, and can extend to involve other organs like the large intestine, liver and stomach. It was first observed by Owtschinnikow in 1907 and was called peritonitis chronica fibrosa incapsulata[1-5]. SEP can be classified as idiopathic or secondary. The idiopathic form is also known as abdominal cocoon, was first described by Foo et al in 1978. Abdominal cocoon is a relatively rare cause of intestinal obstruction[6-21]. Postoperative adhesions account for about 60% of patients with small bowel obstruction. Unusual cases are encountered in only 6% of patients. Abdominal cocoon is one such unusual case of small bowel obstruction[9]. Based on a review of the literature (case series and case reports), we discuss in this paper, etiology, clinical presentation, radiological appearances, diagnosis, treatment, prognosis, and histopathology of abdominal cocoon.

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of this entity has remained relatively unknown. The abdominal cocoon has been classically described in young adolescent females from the tropical and subtropical countries, but adult case reports from temperate zones can be encountered in literature[1,22-27]. To explain the etiology, a number of hypotheses have been proposed. These include retrograde menstruation with a superimposed viral infection, retrograde peritonitis and cell-mediated immunological tissue damage incited by gynecological infection. However, since this condition has also been seen to affect males, premenopausal females and children, there seems to be little support for these theories[1,24-28]. Further hypotheses are therefore needed to explain the cause of idiopathic SEP. Since abdominal cocoon is often accompanied by other embryologic abnormalities such as greater omentum hypoplasia, and developmental abnormality may be a probable etiology[1]. Greater omentum hypoplasia and mesenteric vessel malformation was demonstrated in some cases. To elucidate the precise etiology of idiopathic SEP, further studies of cases are necessary.

The secondary form of SEP has been reported in association with continuous ambulatory chronic peritoneal dialysis (PD)[29-38]. SEP is a serious complication of PD which leads to decrease ultrafiltration and ultimately intestinal obstruction. For some authors[37], the incidence of SEP was 1.2%, but rose to 15% after 6 years, and 38% after 9 years on PD. The risk of SEP is low early in the course of PD, but increases progressively at 6 years and beyond. For others, the respective cumulative incidences of peritoneal sclerosis at 3, 5 and 8 years were 0.3%, 0.8% and 3.9%. This condition was independently predicted by younger age and the duration of PD, but not the rate of peritonitis[33]. Other rare causes of secondary form of SEP[39-52] include, prior abdominal surgery, subclinical primary viral peritonitis, recurrent peritonitis, beta-blocker treatment (practolol), peritoneovenous shunting, pertioneoventricular shunting and, more rarely, abdominal tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, familial Mediterranean fever, intraperitoneal chemotherapy, cirrhosis, liver transplantation, gastrointestinal malignancy, luteinized ovarian thecomas, endometriosis, protein S deficiency, dermoid cyst rupture, and fibrogenic foreign material.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Preoperative diagnosis requires a high index of clinical suspicion. The early clinical features of SEP are nonspecific and are often not recognized[1-12]. Clinically, it presents with recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, weight loss, malnutrition, recurrent episodes of acute, subacute or chronic small bowel incomplete or complete obstruction, and at times with a palpable soft non tender abdominal mass, but some patients may be asymptomatic. In some cases, abdominal distension was secondary to ascites. A high index of clinical suspicion may be generated by the recurrent attacks of non-strangulating obstruction in the same individual combined with relevant imaging findings and lack of other etiologies. The preoperative diagnosis of this entity may be helpful for proper treatment of these patients[2-5].

Less than 1% of PD patients develop overt SEP as manifested by combinations of weight loss, ultrafiltration failure, and intestinal obstruction[33-35].

Clinicians must rigorously pursue a preoperative diagnosis, as it may prevent a “surprise” upon laparotomy and unnecessary procedures for the patient, such as bowel resection. Although it is difficult to make a definite preoperative diagnosis, most cases are diagnosed incidentally at laparotomy. A better awareness of this entity and the imaging techniques may facilitate pre-operatively diagnosis[1,6-9].

RADIOLOGY APPEARANCES

Conventional radiographs may show dilated bowel loops and air fluid level. Contrast study of the small intestine in SEP shows varying lengths of small bowel tightly enclosed in a “cocoon’’ of thickened peritoneum, proximal small bowel dilatation, and increased transit time. It may show a fixed cluster of dilated small bowel loops lying in a concertina like fashion, giving a cauliflower-like appearance (“cauliflower sign” )[10,53].

Ultrasound findings described in SEP include a tri-laminar appearance of the bowel wall, tethering of the bowel to the posterior abdominal wall, dilatation and fixation of small bowel loops, ascites, and membrane formation. Ultrasonography may show a thick-walled mass containing bowel loops, loculated ascites and fibrous adhesions. Sonography shows the small bowel loops encased in a thick membrane made best visible only in the presence of ascites, and may show small bowel loops arranged in concertina shape with a narrow posterior base, having overall appearance of cauliflower[10,53-55].

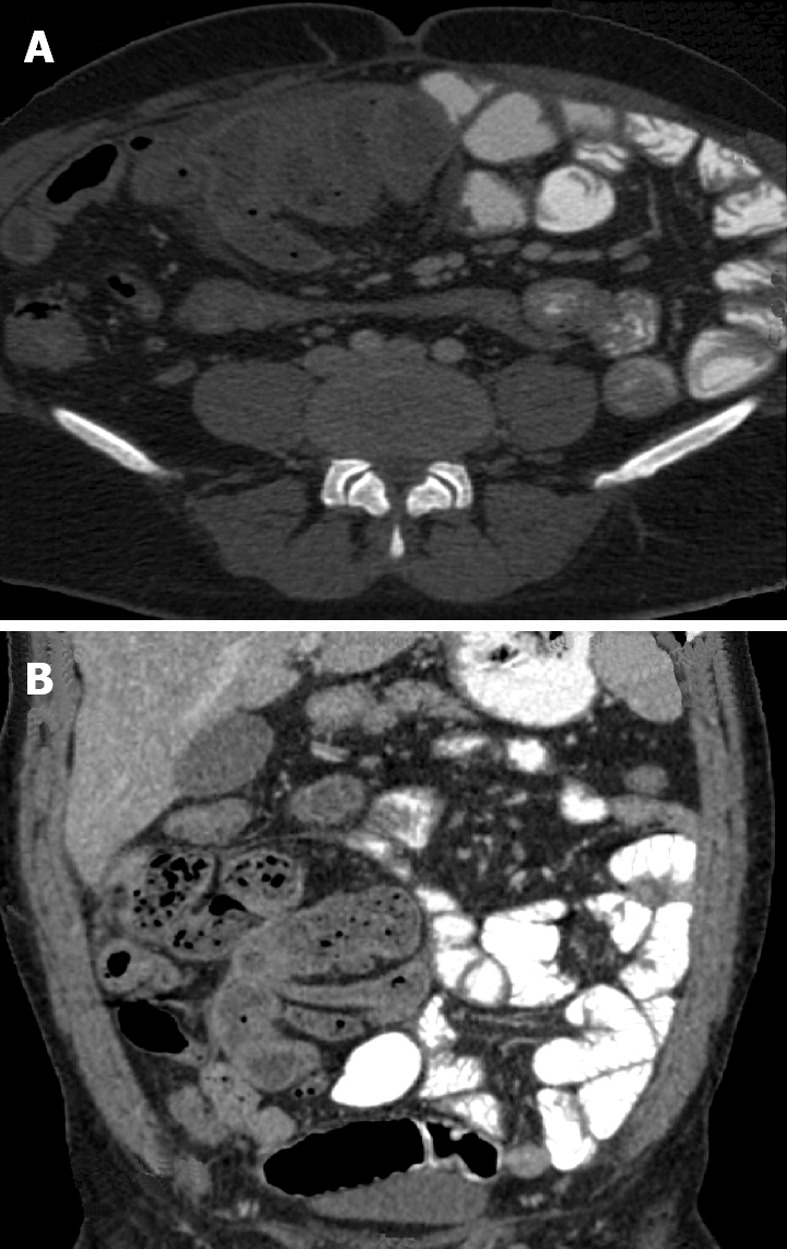

The radiological diagnosis of SEP may now be confidently made on computed tomography (CT) scan[10,53-60]. CT of the abdomen may help in obtaining an early, reliable, and noninvasive diagnosis of SEP for which optimal management can be planned (Figure 1A and B). CT gives complete picture of the entity and associated complications with exclusion of other causes of intestinal obstruction. The exact diagnosis of this entity is made by computed tomography of the abdomen demonstrating small bowel loops congregated to the center of abdomen encased by a thick membrane[58]. CT features of peritoneal calcification, peritoneal thickening, marked enhancement of the peritoneum, loculated fluid collections, gross ascites with small-bowel intestine loops congregated in a single area in the peritoneal cavity, clustered small-bowel loops encased by a thin membrane-like sac, tethering or matting of the small bowel loops, thickening of the bowel wall, soft tissue density mantle, serosal bowel wall calcification, and calcification over liver capsule, spleen, posterior peritoneal wall may be diagnostic of SEP in the appropriate clinical setting. Tethering or matting of the small bowel is usually posterior to the loculated fluid collection, although bowel is sometimes seen to be floating within these collections[57]. Fibrosis results in retraction of the root of the mesentery causing the bowel to clump together leading to obstruction and dysfunction. Retraction of the mesentery can lead to a characteristic appearance of the tethered small bowel loops that we have dubbed the ‘‘gingerbread man’’ sign. In some series, diagnosis of abdominal cocoon was made by a combination of abdominal CT and clinical presentations.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography scan. A: Axial contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen showing bowel loop mass encased in a membrane; B: Anterio-posterior CT scan of the abdomen showing thin membrane around bowel loops.

DIAGNOSIS

A high index of clinical suspicion may be generated by the recurrent attacks of non-strangulating obstruction in the same individual combined with relevant imaging findings and lack of other etiologies. The preoperative diagnosis of this entity may be helpful for proper treatment of these patients. Most cases are diagnosed incidentally at laparotomy, although a preoperative diagnosis is purported feasible by a combination of barium follow-through (concertina pattern or cauliflower sign and delayed transit of contrast medium), ultrasound, and computed tomography of the abdomen (small bowel loops congregated to the center of the abdomen encased by a soft-tissue density mantle)[3-5,61].

There are many causes of intestinal obstruction but differential diagnosis of this condition is mainly from internal hernias[11], voluminous intussusception[62], simple localized peritoneal adhesions, and chronic idiopathic intestinal pseudo-obstruction[63]. The main CT features of an internal hernia are: (1) Central location of the small bowel; (2) Evidence of small bowel obstruction; (3) Clustering of the small bowel; (4) Displacement of and mass effect on adjacent organs; and (5) Stretched, displaced, crowded, and engorged mesenteric vessels. No membrane-like sac can be detected in patients with internal hernias as seen in abdominal cocoon[11]. In chronic idiopathic intestinal pseudo-obstruction, CT scan showed distention of small ad large bowels and no membrane-like sac.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

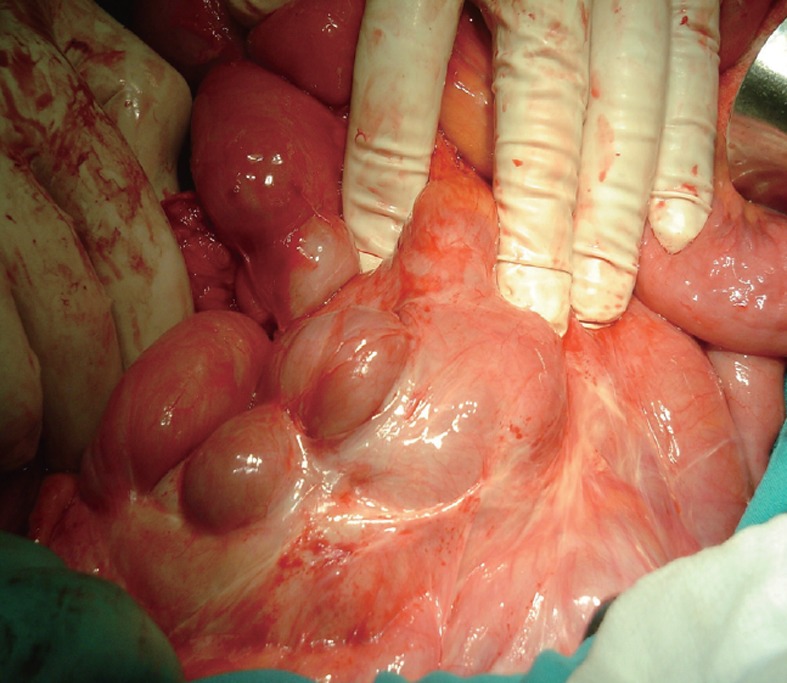

Management of SEP is debated. Most authors agreed that surgical treatment is required[64-66]. In some cases, the diagnosis is established at a late stage of the disease at laparotomy when the patient develops partial or complete small bowel obstruction. Laparotomy reveals characteristic gross thickening of the peritoneum, which encloses some or all of the small intestine in a cocoon of opaque tissue (Figure 2). The root of the mesentery may also be sclerotic and retracted. Fibrous bands form between the loops of bowel, and when the mass of bowel is sectioned, many small loculated abscesses due to local perforations are found. The entity was categorized into 3 types according to the extent of the encasing membrane: (1) Type I - the membrane encapsulated partial intestine; (2) Type II - the entire intestine was encapsulated by the membrane; and (3) Type III - the entire intestine and other organs (e.g., appendix, cecum, ascending colon, ovary, etc.) were encapsulated by the membrane[4]. Various treatment options are adopted, such as subtotal excision of the membrane, enterolysis, small bowel intubation, bowel resection, and exploratory laparotomy with postoperative medical treatment in patients with high perforative risk. When feasible, a stripping of the membrane with intestinal releasing without intestinal resection is the treatment of choice. A simple surgical release of the entrapped bowel via removal of the fibrotic membrane is all that is required to free the bowel if no other cause of obstruction, such as a stricture, is found. In order to avoid complications of postoperative intestinal leakage and short-intestine syndrome, resection of the bowel is indicated only if it is nonviable because resection of the bowel is unnecessary and it increases morbidity and mortality. In some patients, repeated adhesiolysis was required. For some authors, laparoscopic approach was possible to diagnosis and management of abdominal cocoon[67-70]. An excellent long-term postoperative prognosis is most of the times guaranteed with a little risk of recurrence in long term follow-up. No surgical treatment is required in asymptomatic SEP. Surgical complications were reported including intra-abdominal infections, enterocutaneous fistula and perforated bowel[66].

Figure 2.

Laparotomy showing an encapsulating thick, white adherent membrane encasing the small bowel.

Treatment for secondary SEP in dialysis patients is cessation of PD, nutritional support, and surgery for intestinal obstruction, if required. Treatment was variable, but in recent years, steroids and tamoxifen were generally used when SEP was recognized. Preliminary results suggest that steroids and tamoxifen[37] or Angiotensin II inhibitors[71] are beneficial. Transfer to haemodialysis is necessary. Prognosis of SEP is poor, with death usually occurring within a few weeks or months after surgery as it carries a high mortality (20%-80%). This is the result of diagnosis in the latter stages of disease when patients have already developed bowel obstruction. Earlier diagnosis, biocompatible dialysates, and immunosuppressive therapy may improve the outcome for such patients in the future[30-37].

HISTOPATHOLOGY OF SEP

Histopathology is now seldom required as CT imaging appearances along with the clinical features allow a confident diagnosis of SEP. Histologically, the peritoneum shows a proliferation of fibro-connective tissue, inflammatory infiltrates, and dilated lymphatics, with no evidence of foreign body granulomas, giant cells, or birefringent material[72-74]. ‘‘Sclerosing’’ refers to the progressive formation of sheets of dense collagenous tissue; ‘‘encapsulating’’ describes the sheath of new fibrous tissue that covers and constricts the small bowel and restricts its motility; and ‘‘peritonitis’’ implies an ongoing inflammatory process and the presence of a mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate within the new fibrosing tissue[73].

CONCLUSION

Abdominal cocoon, or idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis, is a rare condition of unknown cause characterized by total or partial encasement of the small bowel by a fibrocollagenous cocoon-like sac. Although it was first described in tropical and subtropical adolescent girls, it can occur in all age groups, both genders, and in several regions of the world. The preoperative diagnosis of abdominal cocoon is difficult and the diagnosis should always be considered whenever a patient reports episodes of abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting associated with weight loss. Combination of diagnostic modalities like sonography and CT scan can help in making preoperative diagnosis of this entity and prevent unnecessary bowel resection. This condition should be managed in specialized centers. Surgery is important in the management of this disease. Careful dissection and excision of the thick sac with the release of the small intestine leads to complete recovery.

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: A Ibrahim Amin, MD, Department of Surgery, Queen Margaret Hospital, Dunfermline, Fife KY12 0SU, United Kingdom; Vincenzo Stanghellini, Professor, Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, University of Bologna, VIA MASSARENTI 9, I-40138 Bologna, Italy

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

References

- 1.Xu P, Chen LH, Li YM. Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (or abdominal cocoon): a report of 5 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3649–3651. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i26.3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devay AO, Gomceli I, Korukluoglu B, Kusdemir A. An unusual and difficult diagnosis of intestinal obstruction: The abdominal cocoon. Case report and review of the literature. World J Emerg Surg. 2008;3:36. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-3-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakamoto H. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis--a clinician’s approach to diagnosis and medical treatment. Perit Dial Int. 2005;25 Suppl 4:S30–S38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei B, Wei HB, Guo WP, Zheng ZH, Huang Y, Hu BG, Huang JL. Diagnosis and treatment of abdominal cocoon: a report of 24 cases. Am J Surg. 2009;198:348–353. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohanty D, Jain BK, Agrawal J, Gupta A, Agrawal V. Abdominal cocoon: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and management. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1160–1162. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0595-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devay AO, Gomceli I, Korukluoglu B, Kusdemir A. An unusual and difficult diagnosis of intestinal obstruction: The abdominal cocoon. Case report and review of the literature. World J Emerg Surg. 2006;1:8. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai J, Wang Y, Xuan Z, Hering J, Helton S, Espat NJ. The abdominal cocoon: a rare cause of intestinal obstruction in two patients. Am Surg. 2007;73:1133–1135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng YB, Zhang PF, Ma S, Tong SL. Abdominal cocoon complicated with early postoperative small bowel obstruction. Ann Saudi Med. 2008;28:294–296. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2008.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gurleyik G, Emir S, Saglam A. The abdominal cocoon: a rare cause of intestinal obstruction. Acta Chir Belg. 2010;110:396–398. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2010.11680644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tombak MC, Apaydin FD, Colak T, Duce MN, Balci Y, Yazici M, Kara E. An unusual cause of intestinal obstruction: abdominal cocoon. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:W176–W178. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaur R, Chauhan D, Dalal U, Khurana U. Abdominal cocoon with small bowel obstruction: two case reports. Abdom Imaging. 2012;37:275–278. doi: 10.1007/s00261-011-9754-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baş KK, Besim H. A rare cause of intestinal obstruction: abdominal cocoon. Am Surg. 2011;77:E24–E26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reynders D, Van der Stighelen Y. The abdominal cocoon. A case report. Acta Chir Belg. 2009;109:772–774. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2009.11680534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turagam M, Are C, Velagapudi P, Holley J. Abdominal cocoon: a case of sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2009;9:201–203. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2009.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bas G, Eryilmaz R, Okan I, Somay A, Sahin M. Idiopathic abdominal cocoon: report of a case. Acta Chir Belg. 2008;108:266–268. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2008.11680219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carcano G, Rovera F, Boni L, Dionigi G, Uccella L, Dionigi R. Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: a case report. Chir Ital. 2003;55:605–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Basu A, Sukumar R, Sistla SC, Jagdish S. “Idiopathic” abdominal cocoon. Surgery. 2007;141:277–278. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serafimidis C, Katsarolis I, Vernadakis S, Rallis G, Giannopoulos G, Legakis N, Peros G. Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (or abdominal cocoon) BMC Surg. 2006;6:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-6-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akca T, Ocal K, Turkmenoglu O, Bilgin O, Aydin S. Image of the month: Abdominal cocoon. Arch Surg. 2006;141:943. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.9.943-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matone J, Herbella F, Del Grande JC. Abdominal cocoon syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:xxxi. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Da Luz MM, Barral SM, Barral CM, Bechara Cde S, Lacerda-Filho A. Idiopathic encapsulating peritonitis: report of two cases. Surg Today. 2011;41:1644–1648. doi: 10.1007/s00595-010-4493-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cleffken B, Sie G, Riedl R, Heineman E. Idiopathic sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis in a young female-diagnosis of abdominal cocoon. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:e27–e30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santos VM, Barbosa ER, Lima SH, Porto AS. Abdominal cocoon associated with endometriosis. Singapore Med J. 2007;48:e240–e242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sahoo SP, Gangopadhyay AN, Gupta DK, Gopal SC, Sharma SP, Dash RN. Abdominal cocoon in children: a report of four cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:987–988. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(96)90431-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masuda C, Fujii Y, Kamiya T, Miyamoto M, Nakahara K, Hattori S, Ohshita H, Yokoyama T, Yoshida H, Tsutsumi Y. Idiopathic sclerosing peritonitis in a man. Intern Med. 1993;32:552–555. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.32.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okamoto N, Maeda K, Fujisaki M, Sato H. Abdominal cocoon in an aged man: report of a case. Surg Today. 2007;37:258–260. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3343-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ibrahim NA, Oludara MA. Abdominal cocoon in an adolescent male patient. Trop Doct. 2009;39:254–256. doi: 10.1258/td.2009.090104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirshtein B, Mizrahi S, Sinelnikov I, Lantsberg L. Abdominal cocoon as a rare cause of small bowel obstruction in an elderly man: report of a case and review of the literature. Indian J Surg. 2011;73:73–75. doi: 10.1007/s12262-010-0200-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Afthentopoulos IE, Passadakis P, Oreopoulos DG, Bargman J. Sclerosing peritonitis in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients: one center’s experience and review of the literature. Adv Ren Replace Ther. 1998;5:157–167. doi: 10.1016/s1073-4449(98)70028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holland P. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis in chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Clin Radiol. 1990;41:19–23. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)80926-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenkins SB, Leng BL, Shortland JR, Brown PW, Wilkie ME. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: a case series from a single U.K. center during a 10-year period. Adv Perit Dial. 2001;17:191–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mactier RA. The spectrum of peritoneal fibrosing syndromes in peritoneal dialysis. Adv Perit Dial. 2000;16:223–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson DW, Cho Y, Livingston BE, Hawley CM, McDonald SP, Brown FG, Rosman JB, Bannister KM, Wiggins KJ. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: incidence, predictors, and outcomes. Kidney Int. 2010;77:904–912. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korte MR, Sampimon DE, Betjes MG, Krediet RT. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: the state of affairs. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;7:528–538. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodlad C, Brown EA. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: what have we learned? Semin Nephrol. 2011;31:183–198. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naik RP, Joshipura VP, Patel NR, Chavda HJ. Encapsulating sclerosing peritonitis. Trop Gastroenterol. 2010;31:235–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bansal S, Sheth H, Siddiqui N, Bender FH, Johnston JR, Piraino B. Incidence of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis at a single U.S. university center. Adv Perit Dial. 2010;26:75–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trigka K, Dousdampanis P, Chu M, Khan S, Ahmad M, Bargman JM, Oreopoulos DG. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: a single-center experience and review of the literature. Int Urol Nephrol. 2011;43:519–526. doi: 10.1007/s11255-010-9848-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaushik R, Punia RP, Mohan H, Attri AK. Tuberculous abdominal cocoon--a report of 6 cases and review of the Literature. World J Emerg Surg. 2006;1:18. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jain P, Nijhawan S. Tuberculous abdominal cocoon: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1577–1578. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01880_11.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rastogi R. Abdominal cocoon secondary to tuberculosis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:139–141. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.41733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bani-Hani MG, Al-Nowfal A, Gould S. High jejunal perforation complicating tuberculous abdominal cocoon: a rare presentation in immune-competent male patient. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1373–1375. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0825-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lalloo S, Krishna D, Maharajh J. Case report: abdominal cocoon associated with tuberculous pelvic inflammatory disease. Br J Radiol. 2002;75:174–176. doi: 10.1259/bjr.75.890.750174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gadodia A, Sharma R, Jeyaseelan N. Tuberculous abdominal cocoon. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;84:1–2. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cudazzo E, Lucchini A, Puviani PP, Dondi D, Binacchi S, Bianchi M, Franzini M. [Sclerosing peritonitis. A complication of LeVeen peritoneovenous shunt] Minerva Chir. 1999;54:809–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stanley MM, Reyes CV, Greenlee HB, Nemchausky B, Reinhardt GF. Peritoneal fibrosis in cirrhotics treated with peritoneovenous shunting for ascites. An autopsy study with clinical correlations. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:571–577. doi: 10.1007/BF02282343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wakabayashi H, Okano K, Suzuki Y. Clinical challenges and images in GI. Image 2. Perforative peritonitis on sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (abdominal cocoon) in a patient with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:854, 1210. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamada S, Tanimoto A, Matsuki Y, Hisada Y, Sasaguri Y. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis (abdominal cocoon) associated with liver cirrhosis and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: autopsy case. Pathol Int. 2009;59:681–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2009.02427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maguire D, Srinivasan P, O’Grady J, Rela M, Heaton ND. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis after orthotopic liver transplantation. Am J Surg. 2001;182:151–154. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00685-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin CH, Yu JC, Chen TW, Chan DC, Chen CJ, Hsieh CB. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis in a liver transplant patient: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5412–5413. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i34.5412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fossey SJ, Simson JN. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis secondary to dermoid cyst rupture: a case report. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93:e39–e40. doi: 10.1308/147870811X582495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaman L, Iqbal J, Thenozhi S. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: complication of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20:253–255. doi: 10.1089/lap.2010.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hur J, Kim KW, Park MS, Yu JS. Abdominal cocoon: preoperative diagnostic clues from radiologic imaging with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:639–641. doi: 10.2214/ajr.182.3.1820639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rokade ML, Ruparel M, Agrawal JB. Abdominal cocoon. J Clin Ultrasound. 2007;35:204–206. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ti JP, Al-Aradi A, Conlon PJ, Lee MJ, Morrin MM. Imaging features of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:W50–W54. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stafford-Johnson DB, Wilson TE, Francis IR, Swartz R. CT appearance of sclerosing peritonitis in patients on chronic ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22:295–299. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199803000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Q, Wang D. Abdominal cocoon: multi-detector row CT with multiplanar reformation and review of literatures. Abdom Imaging. 2010;35:92–94. doi: 10.1007/s00261-008-9489-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Loughrey GJ, Hawnaur JM, Sambrook P. Case report: computed tomographic appearance of sclerosing peritonitis with gross peritoneal calcification. Clin Radiol. 1997;52:557–558. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(97)80336-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Térébus Loock M, Lubrano J, Courivaud C, Bresson Vautrin C, Kastler B, Delabrousse E. CT in predicting abdominal cocoon in patients on peritoneal dialysis. Clin Radiol. 2010;65:924–929. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.George C, Al-Zwae K, Nair S, Cast JE. Computed tomography appearances of sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:732–737. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Slim R, Tohme C, Yaghi C, Honein K, Sayegh R. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: a diagnostic dilemma. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:974–975. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li L, Zhang S. Voluminous intussusception involving the whole midgut in a teenager: a unique differentiation from abdominal cocoon. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1654–1657. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1544-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Giorgio R, Cogliandro RF, Barbara G, Corinaldesi R, Stanghellini V. Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction: clinical features, diagnosis, and therapy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011;40:787–807. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Célicout B, Levard H, Hay J, Msika S, Fingerhut A, Pelissier E. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: early and late results of surgical management in 32 cases. French Associations for Surgical Research. Dig Surg. 1998;15:697–702. doi: 10.1159/000018681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Samarasam I, Mathew G, Sitaram V, Perakath B, Rao A, Nair A. The abdominal cocoon and an effective technique of surgical management. Trop Gastroenterol. 2005;26:51–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu HY, Wang YS, Yang WG, Yin SL, Pei H, Sun TW, Wang L. Diagnosis and surgical management of abdominal cocoon: results from 12 cases. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2009;72:447–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Qasaimeh GR, Amarin Z, Rawshdeh BN, El-Radaideh KM. Laparoscopic diagnosis and management of an abdominal cocoon: a case report and literature review. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2010;20:e169–e171. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181f193ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Milone L, Gumbs A. Single incision diagnostic laparoscopy in a patient with sclerosing peritonitis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2010;20:e167–e168. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181f5794d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Makam R, Chamany T, Ramesh S, Potluri VK, Varadaraju PJ, Kasabe P. Laparoscopic management of abdominal cocoon. J Minim Access Surg. 2008;4:15–17. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.40992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ertem M, Ozben V, Gok H, Aksu E. An unusual case in surgical emergency: Abdominal cocoon and its laparoscopic management. J Minim Access Surg. 2011;7:184–186. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.83511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sampimon DE, Kolesnyk I, Korte MR, Fieren MW, Struijk DG, Krediet RT. Use of angiotensin II inhibitors in patients that develop encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int. 2010;30:656–659. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2009.00201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Clatworthy MR, Williams P, Watson CJ, Jamieson NV. The calcified abdominal cocoon. Lancet. 2008;371:1452. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60625-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Honda K, Oda H. Pathology of encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis. Perit Dial Int. 2005;25 Suppl 4:S19–S29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Okada K, Onishi Y, Oinuma T, Nagura Y, Soma M, Saito S, Kanmatsuse K, Takahashi S. Sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis: regional changes of peritoneum. Nephron. 2002;92:481–483. doi: 10.1159/000063290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]