Abstract

Human stem cells are scalable cell populations capable of cellular differentiation. This makes them a very attractive in vitro cellular resource and in theory provides unlimited amounts of primary cells. Such an approach has the potential to improve our understanding of human biology and treating disease. In the future it may be possible to deploy novel stem cell-based approaches to treat human liver diseases. In recent years, efficient hepatic differentiation from human stem cells has been achieved by several research groups including our own. In this review we provide an overview of the field and discuss the future potential and limitations of stem cell technology.

Keywords: Differentiation, Pluripotent stem cells, Hepatocyte-like cells, Liver development, Polymer chemistry, Regenerative medicine, Transplantation, Bio-artificial liver

INTRODUCTION

End stage liver disease (ESLD) is an irreversible condition that leads to the eventual failure of the liver. It may be the final stage of many liver diseases, for example, viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatic disorders, fatty liver disease, drug induced liver injury, and hepatocellular carcinoma, with extremely poor prognosis. The incidence of ESLD is increasing worldwide[1], and current optimal treatment for ESLD is orthotopic liver transplantation[2]. However limited availability of donor livers and immunological incompatibilities are two major obstacles to its routine deployment[3]. This highlights the important need for alternative therapeutic strategies. Researchers have proposed that stem cell biology could provide a scalable answer for the treatment of ESLD, providing cells for transplant and/or cell sources for studying liver disorders and identifying novel treatments.

Cell-based therapy requires the use of cells to replace or facilitate the repair of damaged tissue. Candidate cells for this approach include bipotential, multipotent, pluripotent cells, and primary hepatocytes. Pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), including human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), possess the ability to self renew and differentiate into all somatic cells, offering unlimited potential and are not restricted by donor tissue supply.

hESCs are derived from the inner cell mass of the human blastocyst, and can differentiate into all three primary germ layers[4]. Human iPSCs are produced by forced expression of specific stem cell genes[5]. In recent years, researchers have developed robust procedures to generate functional hepatocyte-like cells (HLCs) from both PSC populations[6-8]. However, it is notable that PSC strategies have not yielded, as yet, a cell type that appropriately contributes to tissue homeostasis as cell transplantation frequently results in tumour formation[9,10]. As a result, scalable cell-based therapies from PSCs are likely to be longer-term strategies which require significant refinement.

Extra-corporeal support has been proposed as a mid-term strategy, in particular bio-artificial livers, to treat human liver disease. Bio-artificial livers (BALs) are designed to filter and biotransform toxic substances, and have been used successfully to bridge patients to transplant or treat acute liver failure. Research demonstrates that BALs can reduce mortality in acute liver failure compared with traditional standard medical therapy[11,12], but the application has been severely limited by the poor availability of functional human hepatocytes. By employing PSC technology, it may now be possible to produce humanised BAL devices at reasonable cost.

In addition to their important role in the clinic, human hepatocytes have a critical part to play in the drug discovery process. Many candidate compounds fail at late stage or even after approval due to unanticipated toxicity. In routine drug discovery, the pharmaceutical industry deploys the tumor-derived cells and primary hepatocytes to screen compounds. While these models are useful, they do not always extrapolate to human biology and exhibit poor lifespan and variable metabolic activity. PSCs-derived hepatocytes have the potential to overcome these problems. Advances in stem cell biology and reprograming have allowed the development of novel models which have the potential to provide another level of understanding behind the pathophysiology of liver diseases. iPSC modelling also provides us with potential system to better understand the influence of gene polymorphisms.

Human PSCs derived HLCs show great promise for research and clinical applications including cell-based therapies, drug development, and disease modeling. This review gives an overview of human hepatic differentiation from PSCs and their potential application in modern medicine.

CURRENT CELL SOURCES USED IN HEPATOLOGY

Primary human hepatocytes and liver cancer cell lines

Hepatocytes are the principle cell type found in the liver and perform the majority of the liver functions. Primary human hepatocytes (PHHs) are therefore a useful tool for medical applications such as cell-based therapy and drug discovery. However, PHHs are mainly obtained from scarce and low quality resected surgical specimens[13]. The scarcity and variability in these preparations restricts their widespread application in vitro[14]. Therefore liver cell lines have been employed routinely as they demonstrate long lifespan and are easy to maintain. HepG2 is a liver cell line derived from fetal tissue which exhibits poor metabolic function and secrete a variety of soluble serum proteins[15]. They have been used as a model system for cytochrome P450 (CYP) metabolism and toxicity. And additionally they have been used in clinical trials with bioartificial liver devices[16,17]. Interestingly, a clonal derivative of the HepG2 line, C3A, demonstrates marked reduction in α-fetoprotein (AFP) and increased albumin (ALB) secretion, indicating a more mature status in vitro. More recently, a new human hepatoma cell line has been derived. HepaRG demonstrates a number of liver-specific functions including the expression of CYP 1A2, 2B6, 2C9, 2E1, 3A4[18,19] and better overall performance than existing liver cell lines. Although informative and scalable, liver cancer cell lines show lower drug-metabolizing activity than their adult counterparts and do not accurately predict human drug toxicity[20] and therefore do not constitute a real alternative to the gold standard primary hepatocyte. Moreover, such cells may provide interesting in vitro models or the bio-component of the BAL, but they could not be used for cell transplantation in vivo.

Oval cells and hepatoblasts

Oval cells are an adult liver cell population that emerges from the biliary tree following chronic liver injury. Several studies have investigated the transplantation of oval cells showing that these bipotential cells could proliferate and contribute to both parenchyma and biliary epithelia in vivo[21-28]. Oval cells express the stem cell markers Thy-1 (CD90), CD34 and Sca-1, along with liver-specific markers, including AFP, Gamma-glutamyltransferase, laminin and cytokeratin 19 (CK 19)[23,24].

The tissue microenvironment plays an essential role in orchestrating oval cell-mediated liver regeneration. Laminin contributes to the maintenance of undifferentiated progenitor cells and progenitor cell-mediated tissue repair[29]. Moreover, Kallis et al[30] demonstrated that extracellular matrix (ECM) remodelling during resolution and laminin deposition was likely to be important prerequisite to hepatic progenitor cell activation, expansion and repair.

Similar to oval cells, hepatoblasts from fetal liver could also represent a potential source of hepatocytes and biliary epithelial cells[24,31]. The bipotential nature of this cell type also makes it an attractive target for therapy. Transplant studies demonstrate that hepatoblasts may be a potential therapeutic strategy for ESLDs or hepatic failure. Although great progress in the fundamental research and clinical application have been made, there are still limitations to widespread use of these cells, such as low cell number in vivo, no specific biomarker for purification and poor expansion in vitro.

Bone marrow stem cells and mesenchymal stem cell

The bone marrow (BM) contains stem cells populations in vivo. They can be roughly divided into of hematopoietic (HSCs) and nonhematopoietic stem cells usually referred to as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). The great success of BM stem cell for treatment of leukaemia has attracted scientists to use these cells for other serious diseases such as ESLD. Analysis of BM transplant into mouse models and patients have demonstrated that transplanted BM could contribute to partial correction of hepatic function[32-34]. However, the role of BM is controversial; some researchers found that BM didn’t contribute to hepatocyte or biliary cell differentiation and liver regeneration, but actually contributed to liver fibrosis[35,36], which raises serious safety concerns.

Similar to BM, MSCs have been successfully transplanted[37]. They are multipotent stem cells capable of mesodermal, neuro-ectodermal and endodermal differentiation depending on surrounding microenviroment[38-41]. In addition, MSCs have anti-fibrotic properties inhibiting activated fibrogenic cells such as hepatic stellate cells[42]. The role of MSCs in liver regeneration and disease has been evidenced in animal models. Moreover MSC based therapies for patients with ESLDs have shown promise in phase I and II clinical trials[37,43,44]. Treatment was well tolerated by all patients with liver fibrosis and heptic function improved following MSCs transplantation[37] and during the follow-up[43]. Peng et al[45] reported that the biochemical hepatic index and MELD score were markedly improved from 2-3 wk post transplantation. However, long-term hepatic function were not significantly enhanced in 527 patients with liver failure caused by hepatitis B. Although MSC transplantation confers benefit to patients with liver cirrhosis, it may not be applicable to all kind of ESLDs.

HEPATIC DIFFERENTIATION FROM PLURIPOTENT STEM CELLS

Human ESCs are derived from the inner cell mass of blastocyst stage embryos and are highly primitive cells which exhibit pluripotency and the ability to self-renew[4,46]. Rambhatla et al[47] reported the directed differentiation of human ESCs to HLCs for the first time in 2003, which could express some hepatocyte markers. Since then labs have established more robust and efficient procedures to derive better functioning HLCs. Embryoid body (EB) formation has been one method to differentiate ESCs into hepatocytes. However, this approach exhibits limitations to scale and culture definition. Therefore, monolayer adherent culture systems have been developed to direct ESC hepatic differentiation into hepatocytes, which bypass these limitations[6,48-51]. We developed a simple 3-stage procedure by which hESCs can be directly differentiated to HLCs at an efficiency of about 90%[6,8]. Our research demonstrated that Wnt3a signaling was important in this process, improving hepatocellular function both in vitro and in vivo[6,52]. Most recently we identified a novel polyurethane extra cellular support which delivers long-term and stable HLC function which is drug inducible[53].

In 2006, it was demonstrated that murine fibroblasts could be reprogrammed into a pluripotent state similar to that observed in ESCs[54]. Subsequently Takahashi et al[5] and Park et al[55] successfully reprogrammed human somatic cells into iPSCs. They generated PSCs from human skin through ectopic expression of four genes (Oct3/4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Klf4), which were known to be involved in the induction of murine pluripotency. Since these experiments researchers continue to refine and simplify the reprogramming process.

Human iPSCs and ESCs display similar morphologies, proliferation rates and expression of a number of stem cell biomarkers. However, specific differences between ESCs and iPSCs exist. Obviously the biggest difference is that iPSCs are derived from adult tissues. In addition, some comparative genomic analyses shows that hundreds of genes are differentially expressed in these two cell types[56]. Given their adult origin, iPSCs can contain an epigenetic “memory” of the donor tissue[57,58], which can restrict their differentiation potential and therefore utility.

iPSCs have been differentiated to numerous cell types[59], including hepatocytes. We and others have devised efficient methods to generate hepatocytes in vitro[7,60,61]. The derivative HLCs from both hESC and iPSC models demonstrate a similar expression of genes important for normal liver physiology. Jozefczuk et al[62] demonstrated 80% similarity of gene expression between HLCs derived from hESCs or iPSCs. Additionally, there were specific differences between the types of HLCs derived from ESCs and iPSCs in particular the CYP genes.

Most recently a study reported the direct conversion of murine fibroblasts to HLCs without the need for cellular pluripotency. In two studies HLC differentiation was conferred using either Gata4, Hnf1α and Foxa3, or HNF4a in combination with Foxa1, Foxa2 or Foxa3[63,64]. HLCs exhibited hepatic gene expression and function in vitro and rescued fumarylacetoacetate-hydrolase-deficient (Fah-/-) mice in vivo[63,64]. These studies provide another alternative method of hepatic conversion, which offer potential for liver research and therapy.

HEPATIC DIFFERENTIATION IN CELL-BASED THERAPIES AND TOOLS

Hepatic differentiation for cell-based therapy

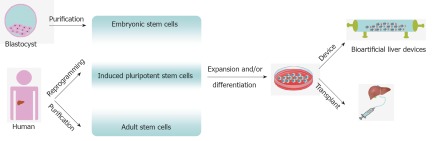

PSCs offer a possible source to treat liver disease. Cell therapy for liver disease includes transplantation (including genome edited cells to correct metabolic defects[65]) and bio-artificial liver devices. The cell-based approaches are very encouraging, but further studies are required to demonstrate long-term safety of cell-based transplantation[9,10]. In the interim BALs containing hepatocytes could provide alternative support for patients with acute hepatic failure or awaiting liver transplantation. Efforts to generate long-lived functional HLCs may allow the development of more highly effective BALs. The potential application of human stem cells in cell-based therapy for liver diseases is summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Potential application of human stem cells in cell based therapy for liver disease. Pluripotent and multipotent stem cells can be reprogrammed or purified from human material that was been ethically sourced. Following expansion and differentiation the derivative hepatocyte like cells can be used for transplantation or bio-artificial liver construction.

Hepatic differentiation for drug discovery

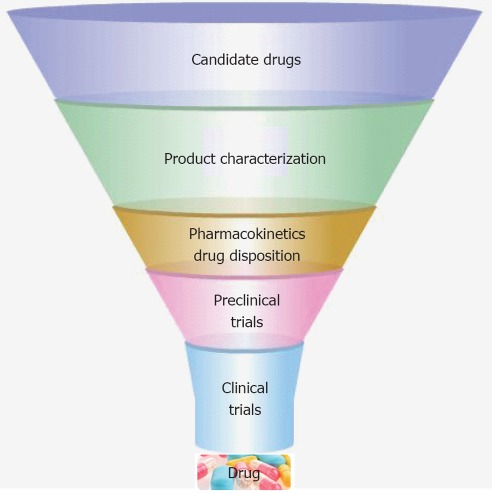

The drug development process is a hugely expensive process, due to its length and high levels of compound attrition. Drug development proceeds through several stages in order to produce a drug that is safe, efficacious, and meets regulatory requirements (Figure 2). The liver plays a central role in the metabolism of a majority of drugs. Therefore, a standardized screening model with human hepatocytes for new drug compounds could help to reduce drug attrition and costs. Traditional cell models for drug discovery include primary human hepatocytes, immortalised cell lines and animal tissues; however, these cell sources possess a number of limitations including poor function, species variability and instability in culture[14,20]. Advances in PSCs research and liver engineering have provided models that may overcome some of the problems associated with existing technology. Moreover, in parallel with extracorporeal device development, stem-cell-derived HLCs in three dimensional (3D) are more likely to mimic human liver properties in vitro.

Figure 2.

Human liver cells in drug discovery[7,53,66,67]. Drug development process is a lengthy and expensive process. The derivation of hepatocyte-like cells from different human genotypes may provide novel in-vitro models for the screening of new compounds in the drug discovery process.

Hepatic differentiation for disease modelling

PSCs have provided scientists with novel models to study human liver disease. Rashid et al[60] reported an effective procedure for hepatocyte generation from iPSCs exhibiting disease mutations. Using these cells, they modeled inherited metabolic disorders that affect the liver; alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency, familial hypercholesterolemia, and glycogen storage disease type 1a. These models accurately reflected elements of the disease process. More recently research iPSCs, obtained from patients with tyrosinemia, glycogen storage disease, progressive familial hereditary cholestasis, and Crigler-Najjar syndrome, were differentiated into functioning HLCs[68]. These inherited liver diseases that mainly arise as a result of loss of function mutation, therefore these studies offers a unique opportunity to study the effects of specific gene defects on human liver biology and to better understand liver pathogenesis in disease.

Improving hepatic differentiation

PSC technologies have the potential to produce unlimited amounts of human liver cells. As discussed above, human hepatocytes from PSCs could be utilized for cell-based therapy, assessment of drug toxicity and disease modelling. Therefore, the PSC-derived HLCs should be reliable, stable in character and display high levels of metabolic activity. A better understanding of human liver development and optimal tissue microenvironments are likely to play an important role in this process.

HUMAN LIVER DEVELOPMENT

Liver development occurs through a series of reciprocal tissue interactions between the embryonic endoderm and nearby mesoderm. Endoderm contributes to the digestive tract and has a principal role in the development of the liver (Figure 3). The secretions of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) from the cardiac mesoderm and septum transversum mesenchyme (STM) help orchestrate human liver development from foregut endoderm in concert[69] with canonical Wnt signalling[6,70,71]. Three to 4 wk post fertilisation cells called hepatoblasts, positive for CK19 and HepPar1, are detected for the first time[31]. The hepatoblasts proliferate and form the liver bud. The hepatic endoderm thickens into a columnar epithelium, and hepatoblasts delaminate and invade the STM and undergo cellular proliferation and differentiation. Experiments have shown that a number of factors such as FGF, epidermal growth factor (EGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), transforming growth factor (TGF), tumor necrosis factors (TNF), and interleukin-6 contribute to the hepatocytes proliferation and differentiation[72,73]. Between 6-8 wk gestation, the bile duct and hepatic structure are easily identified[31]. Maturation of hepatocytes and bile epithelial cells continues after birth. An overview of embryonic liver development is summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Human fetal liver development[31,74]. The key stages of human liver development are shown in pink and blue. Endoderm formation occurs in the 2nd-3rd wk of fetal development. The liver bud forms between week 3-4 and expands rapidly. Hepatocytes and biliary epithelia differentiate and mature from 7 wk post fertilisation and this process continues in the neo-nate.

IMPROVING CELL CULTURE MICROENVIRONMENT

The tissue microenvironment also plays an essential role in liver development and hepatic differentiation. Two dimensional (2D) hepatic differentiation is probably the most widely used system in laboratories. While this technology is efficient and scalable, there are several drawbacks related to 2D culture, including poor drug inducibility and rapid cell dedifferentiation. During human liver development, hepatocytes mature in a 3D environment with a number of cell types providing support. In light of the increasing need for better-differentiated hepatocytes from PSCs, we and others have developed 3D systems to improve and stabilize hepato-cellular phenotype[53,75,76].

Undoubtedly 3D culture leads to improvements in hepatic function. In the future modulation of oxygenation and physiological delivery of nutrients in 3D environment have great potential to improve cell phenotype and therefore utility.

CONCLUSION

The development of hESC and iPSC technology has led to a new era of discovery in liver medicine. Advances in PSC technology offer the promise of scalable human hepatocytes for cell-based therapies, assessment of drug efficacy and toxicity, and disease modelling. The challenge remains to cost effectively scale up this technology for industrial manufacture. A better knowledge of liver development and the use of novel supportive culture systems will help to improve the manner in which we derive mature human hepatocytes.

Footnotes

Supported by A RCUK fellowship, EP/E500145/1, to Hay DC; A grant from the Edinburgh Bioquarter, to Medine CN; China Scholarship Council, No.2010658022, to Zhou WL

Peer reviewer: Dr. Run Yu, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, 8700 Beverly Blvd, B-131, Los Angeles, CA 90048, United States

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Yang JD, Roberts LR. Hepatocellular carcinoma: A global view. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:448–458. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miró JM, Laguno M, Moreno A, Rimola A. Management of end stage liver disease (ESLD): what is the current role of orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT)? J Hepatol. 2006;44:S140–S145. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haridass D, Narain N, Ott M. Hepatocyte transplantation: waiting for stem cells. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2008;13:627–632. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e328317a44f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, Jones JM. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861–872. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hay DC, Fletcher J, Payne C, Terrace JD, Gallagher RC, Snoeys J, Black JR, Wojtacha D, Samuel K, Hannoun Z, et al. Highly efficient differentiation of hESCs to functional hepatic endoderm requires ActivinA and Wnt3a signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12301–12306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806522105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan GJ, Hay DC, Park IH, Fletcher J, Hannoun Z, Payne CM, Dalgetty D, Black JR, Ross JA, Samuel K, et al. Generation of functional human hepatic endoderm from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Hepatology. 2010;51:329–335. doi: 10.1002/hep.23335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medine CN, Hannoun Z, Greenhough S, Payne CM, Fletcher J, Hay DC. Deriving Metabolically Active Hepatic Endoderm from Pluripotent Stem Cells. Human Embryonic and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 369–386. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Payne CM, Samuel K, Pryde A, King J, Brownstein D, Schrader J, Medine CN, Forbes SJ, Iredale JP, Newsome PN, et al. Persistence of functional hepatocyte-like cells in immune-compromised mice. Liver Int. 2011;31:254–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basma H, Soto-Gutiérrez A, Yannam GR, Liu L, Ito R, Yamamoto T, Ellis E, Carson SD, Sato S, Chen Y, et al. Differentiation and transplantation of human embryonic stem cell-derived hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:990–999. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stutchfield BM, Simpson K, Wigmore SJ. Systematic review and meta-analysis of survival following extracorporeal liver support. Br J Surg. 2011;98:623–631. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chamuleau RA. Future of bioartificial liver support. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;1:21–25. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v1.i1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thasler WE, Weiss TS, Schillhorn K, Stoll PT, Irrgang B, Jauch KW. Charitable State-Controlled Foundation Human Tissue and Cell Research: Ethic and Legal Aspects in the Supply of Surgically Removed Human Tissue For Research in the Academic and Commercial Sector in Germany. Cell Tissue Bank. 2003;4:49–56. doi: 10.1023/A:1026392429112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuetz EG, Li D, Omiecinski CJ, Muller-Eberhard U, Kleinman HK, Elswick B, Guzelian PS. Regulation of gene expression in adult rat hepatocytes cultured on a basement membrane matrix. J Cell Physiol. 1988;134:309–323. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041340302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu MC, Yu S, Sy J, Redman CM, Lipmann F. Tyrosine sulfation of proteins from the human hepatoma cell line HepG2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:7160–7164. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.21.7160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nyberg SL, Remmel RP, Mann HJ, Peshwa MV, Hu WS, Cerra FB. Primary hepatocytes outperform Hep G2 cells as the source of biotransformation functions in a bioartificial liver. Ann Surg. 1994;220:59–67. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharma R, Greenhough S, Medine CN, Hay DC. Three-Dimensional Culture of Human Embryonic Stem Cell Derived Hepatic Endoderm and Its Role in Bioartificial Liver Construction. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010;2010:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2010/236147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aninat C, Piton A, Glaise D, Le Charpentier T, Langouët S, Morel F, Guguen-Guillouzo C, Guillouzo A. Expression of cytochromes P450, conjugating enzymes and nuclear receptors in human hepatoma HepaRG cells. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:75–83. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.006759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lübberstedt M, Müller-Vieira U, Mayer M, Biemel KM, Knöspel F, Knobeloch D, Nüssler AK, Gerlach JC, Zeilinger K. HepaRG human hepatic cell line utility as a surrogate for primary human hepatocytes in drug metabolism assessment in vitro. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2011;63:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkening S, Stahl F, Bader A. Comparison of primary human hepatocytes and hepatoma cell line Hepg2 with regard to their biotransformation properties. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31:1035–1042. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.8.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dabeva MD, Petkov PM, Sandhu J, Oren R, Laconi E, Hurston E, Shafritz DA. Proliferation and differentiation of fetal liver epithelial progenitor cells after transplantation into adult rat liver. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:2017–2031. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65074-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahieu-Caputo D, Allain JE, Branger J, Coulomb A, Delgado JP, Andreoletti M, Mainot S, Frydman R, Leboulch P, Di Santo JP, et al. Repopulation of athymic mouse liver by cryopreserved early human fetal hepatoblasts. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:1219–1228. doi: 10.1089/hum.2004.15.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kubota H, Storms RW, Reid LM. Variant forms of alpha-fetoprotein transcripts expressed in human hematopoietic progenitors. Implications for their developmental potential towards endoderm. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27629–27635. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202117200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Terrace JD, Currie IS, Hay DC, Masson NM, Anderson RA, Forbes SJ, Parks RW, Ross JA. Progenitor cell characterization and location in the developing human liver. Stem Cells Dev. 2007;16:771–778. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorenzini S, Isidori A, Catani L, Gramenzi A, Talarico S, Bonifazi F, Giudice V, Conte R, Baccarani M, Bernardi M, et al. Stem cell mobilization and collection in patients with liver cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:932–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lorenzini S, Bird TG, Boulter L, Bellamy C, Samuel K, Aucott R, Clayton E, Andreone P, Bernardi M, Golding M, et al. Characterisation of a stereotypical cellular and extracellular adult liver progenitor cell niche in rodents and diseased human liver. Gut. 2010;59:645–654. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.182345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakai H, Tagawa Y, Tamai M, Motoyama H, Ogawa S, Soeda J, Nakata T, Miyagawa S. Isolation and characterization of portal branch ligation-stimulated Hmga2-positive bipotent hepatic progenitor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;403:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu CX, Zou Q, Zhu ZY, Gao YT, Wang YJ. Intrahepatic transplantation of hepatic oval cells for fulminant hepatic failure in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1506–1511. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leite AR, Corrêa-Giannella ML, Dagli ML, Fortes MA, Vegas VM, Giannella-Neto D. Fibronectin and laminin induce expression of islet cell markers in hepatic oval cells in culture. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;327:529–537. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0340-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kallis YN, Robson AJ, Fallowfield JA, Thomas HC, Alison MR, Wright NA, Goldin RD, Iredale JP, Forbes SJ. Remodelling of extracellular matrix is a requirement for the hepatic progenitor cell response. Gut. 2011;60:525–533. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haruna Y, Saito K, Spaulding S, Nalesnik MA, Gerber MA. Identification of bipotential progenitor cells in human liver development. Hepatology. 1996;23:476–481. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terai S, Sakaida I, Yamamoto N, Omori K, Watanabe T, Ohata S, Katada T, Miyamoto K, Shinoda K, Nishina H, et al. An in vivo model for monitoring trans-differentiation of bone marrow cells into functional hepatocytes. J Biochem. 2003;134:551–558. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alison MR, Poulsom R, Jeffery R, Dhillon AP, Quaglia A, Jacob J, Novelli M, Prentice G, Williamson J, Wright NA. Hepatocytes from non-hepatic adult stem cells. Nature. 2000;406:257. doi: 10.1038/35018642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muraca M, Ferraresso C, Vilei MT, Granato A, Quarta M, Cozzi E, Rugge M, Pauwelyn KA, Caruso M, Avital I, et al. Liver repopulation with bone marrow derived cells improves the metabolic disorder in the Gunn rat. Gut. 2007;56:1725–1735. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.127969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Russo FP, Alison MR, Bigger BW, Amofah E, Florou A, Amin F, Bou-Gharios G, Jeffery R, Iredale JP, Forbes SJ. The bone marrow functionally contributes to liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1807–1821. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dalakas E, Newsome PN, Boyle S, Brown R, Pryde A, McCall S, Hayes PC, Bickmore WA, Harrison DJ, Plevris JN. Bone marrow stem cells contribute to alcohol liver fibrosis in humans. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:1417–1425. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kharaziha P, Hellström PM, Noorinayer B, Farzaneh F, Aghajani K, Jafari F, Telkabadi M, Atashi A, Honardoost M, Zali MR, et al. Improvement of liver function in liver cirrhosis patients after autologous mesenchymal stem cell injection: a phase I-II clinical trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1199–1205. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32832a1f6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S, Marshak DR. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dezawa M, Ishikawa H, Itokazu Y, Yoshihara T, Hoshino M, Takeda S, Ide C, Nabeshima Y. Bone marrow stromal cells generate muscle cells and repair muscle degeneration. Science. 2005;309:314–317. doi: 10.1126/science.1110364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dezawa M, Kanno H, Hoshino M, Cho H, Matsumoto N, Itokazu Y, Tajima N, Yamada H, Sawada H, Ishikawa H, et al. Specific induction of neuronal cells from bone marrow stromal cells and application for autologous transplantation. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1701–1710. doi: 10.1172/JCI20935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pan RL, Chen Y, Xiang LX, Shao JZ, Dong XJ, Zhang GR. Fetal liver-conditioned medium induces hepatic specification from mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells: a novel strategy for hepatic transdifferentiation. Cytotherapy. 2008;10:668–675. doi: 10.1080/14653240802360704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J, Bian C, Liao L, Zhu Y, Li J, Zeng L, Zhao RC. Inhibition of hepatic stellate cells proliferation by mesenchymal stem cells and the possible mechanisms. Hepatol Res. 2009;39:1219–1228. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2009.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.El-Ansary M, Mogawer Sh, Abdel-Aziz I, Abdel-Hamid S. Phase I Trial: Mesenchymal Stem Cells Transplantation in End Stage Liver Disease. J Am Sci. 2010;6:135–144. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Terai S, Ishikawa T, Omori K, Aoyama K, Marumoto Y, Urata Y, Yokoyama Y, Uchida K, Yamasaki T, Fujii Y, et al. Improved liver function in patients with liver cirrhosis after autologous bone marrow cell infusion therapy. Stem Cells. 2006;24:2292–2298. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peng L, Xie DY, Lin BL, Liu J, Zhu HP, Xie C, Zheng YB, Gao ZL. Autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in liver failure patients caused by hepatitis B: short-term and long-term outcomes. Hepatology. 2011;54:820–828. doi: 10.1002/hep.24434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reubinoff BE, Pera MF, Fong CY, Trounson A, Bongso A. Embryonic stem cell lines from human blastocysts: somatic differentiation in vitro. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:399–404. doi: 10.1038/74447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rambhatla L, Chiu CP, Kundu P, Peng Y, Carpenter MK. Generation of hepatocyte-like cells from human embryonic stem cells. Cell Transplant. 2003;12:1–11. doi: 10.3727/000000003783985179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Touboul T, Hannan NR, Corbineau S, Martinez A, Martinet C, Branchereau S, Mainot S, Strick-Marchand H, Pedersen R, Di Santo J, et al. Generation of functional hepatocytes from human embryonic stem cells under chemically defined conditions that recapitulate liver development. Hepatology. 2010;51:1754–1765. doi: 10.1002/hep.23506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brolén G, Sivertsson L, Björquist P, Eriksson G, Ek M, Semb H, Johansson I, Andersson TB, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Heins N. Hepatocyte-like cells derived from human embryonic stem cells specifically via definitive endoderm and a progenitor stage. J Biotechnol. 2010;145:284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Agarwal S, Holton KL, Lanza R. Efficient differentiation of functional hepatocytes from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2008;26:1117–1127. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duan Y, Catana A, Meng Y, Yamamoto N, He S, Gupta S, Gambhir SS, Zern MA. Differentiation and enrichment of hepatocyte-like cells from human embryonic stem cells in vitro and in vivo. Stem Cells. 2007;25:3058–3068. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Payne C, King J, Hay D. The role of activin/nodal and Wnt signaling in endoderm formation. Vitam Horm. 2011;85:207–216. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385961-7.00010-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hay DC, Pernagallo S, Diaz-Mochon JJ, Medine CN, Greenhough S, Hannoun Z, Schrader J, Black JR, Fletcher J, Dalgetty D, et al. Unbiased screening of polymer libraries to define novel substrates for functional hepatocytes with inducible drug metabolism. Stem Cell Res. 2011;6:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, Yabuuchi A, Huo H, Ince TA, Lerou PH, Lensch MW, Daley GQ. Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature. 2008;451:141–146. doi: 10.1038/nature06534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chin MH, Mason MJ, Xie W, Volinia S, Singer M, Peterson C, Ambartsumyan G, Aimiuwu O, Richter L, Zhang J, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells and embryonic stem cells are distinguished by gene expression signatures. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:111–123. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim K, Doi A, Wen B, Ng K, Zhao R, Cahan P, Kim J, Aryee MJ, Ji H, Ehrlich LI, et al. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2010;467:285–290. doi: 10.1038/nature09342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu H, Kim Y, Sharkis S, Marchionni L, Jang YY. In vivo liver regeneration potential of human induced pluripotent stem cells from diverse origins. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:82ra39. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu SM, Hochedlinger K. Harnessing the potential of induced pluripotent stem cells for regenerative medicine. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:497–505. doi: 10.1038/ncb0511-497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rashid ST, Corbineau S, Hannan N, Marciniak SJ, Miranda E, Alexander G, Huang-Doran I, Griffin J, Ahrlund-Richter L, Skepper J, et al. Modeling inherited metabolic disorders of the liver using human induced pluripotent stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3127–3136. doi: 10.1172/JCI43122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Si-Tayeb K, Noto FK, Nagaoka M, Li J, Battle MA, Duris C, North PE, Dalton S, Duncan SA. Highly efficient generation of human hepatocyte-like cells from induced pluripotent stem cells. Hepatology. 2010;51:297–305. doi: 10.1002/hep.23354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jozefczuk J, Prigione A, Chavez L, Adjaye J. Comparative analysis of human embryonic stem cell and induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells reveals current drawbacks and possible strategies for improved differentiation. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:1259–1275. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huang P, He Z, Ji S, Sun H, Xiang D, Liu C, Hu Y, Wang X, Hui L. Induction of functional hepatocyte-like cells from mouse fibroblasts by defined factors. Nature. 2011;475:386–389. doi: 10.1038/nature10116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sekiya S, Suzuki A. Direct conversion of mouse fibroblasts to hepatocyte-like cells by defined factors. Nature. 2011;475:390–393. doi: 10.1038/nature10263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yusa K, Rashid ST, Strick-Marchand H, Varela I, Liu PQ, Paschon DE, Miranda E, Ordóñez A, Hannan NR, Rouhani FJ, et al. Targeted gene correction of α1-antitrypsin deficiency in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;478:391–394. doi: 10.1038/nature10424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ek M, Söderdahl T, Küppers-Munther B, Edsbagge J, Andersson TB, Björquist P, Cotgreave I, Jernström B, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Johansson I. Expression of drug metabolizing enzymes in hepatocyte-like cells derived from human embryonic stem cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Duan Y, Ma X, Zou W, Wang C, Bahbahan IS, Ahuja TP, Tolstikov V, Zern MA. Differentiation and characterization of metabolically functioning hepatocytes from human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:674–686. doi: 10.1002/stem.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ghodsizadeh A, Taei A, Totonchi M, Seifinejad A, Gourabi H, Pournasr B, Aghdami N, Malekzadeh R, Almadani N, Salekdeh GH, et al. Generation of liver disease-specific induced pluripotent stem cells along with efficient differentiation to functional hepatocyte-like cells. Stem Cell Rev. 2010;6:622–632. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9189-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Duncan SA, Watt AJ. BMPs on the road to hepatogenesis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1879–1884. doi: 10.1101/gad.920601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McLin VA, Rankin SA, Zorn AM. Repression of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in the anterior endoderm is essential for liver and pancreas development. Development. 2007;134:2207–2217. doi: 10.1242/dev.001230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gadue P, Huber TL, Paddison PJ, Keller GM. Wnt and TGF-beta signaling are required for the induction of an in vitro model of primitive streak formation using embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16806–16811. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603916103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhao R, Duncan SA. Embryonic development of the liver. Hepatology. 2005;41:956–967. doi: 10.1002/hep.20691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tanimizu N, Miyajima A. Molecular mechanism of liver development and regeneration. Int Rev Cytol. 2007;259:1–48. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(06)59001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zorn AM. Liver development. Cambridge MA: StemBook; 2008. pp. 4–11. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bokhari M, Carnachan RJ, Cameron NR, Przyborski SA. Novel cell culture device enabling three-dimensional cell growth and improved cell function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:1095–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Coward SM, Legallais C, David B, Thomas M, Foo Y, Mavri-Damelin D, Hodgson HJ, Selden C. Alginate-encapsulated HepG2 cells in a fluidized bed bioreactor maintain function in human liver failure plasma. Artif Organs. 2009;33:1117–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2009.00821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]