Abstract

Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) are critical for control of lentiviruses, including equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV). Measurement of equine CTL responses has relied on chromium-release assays, which do not allow accurate quantitation. Recently, the equine MHC class I molecule 7-6, associated with the ELA-A1 haplotype, was shown to present both the Gag-GW12 and Env-RW12 EIAV CTL epitopes. In this study, 7-6/Gag-GW12 and 7-6/Env-RW12 MHC class I/peptide tetrameric complexes were constructed and used to analyze Gag-GW12- and Env-RW12-specific CTL responses in two EIAV-infected horses (A2164 and A2171). Gag-GW12 and Env-RW12 tetramer-positive CD8+ cells were identified in nonstimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells as early as 14 days post-EIAV inoculation, and frequencies of tetramer-positive cells ranged from 0.4% to 6.7% of nonstimulated peripheral blood CD8+ cells during the 127-day study period. Although both horses terminated the initial viremic peak, only horse A2171 effectively controlled viral load. Neutralizing antibody was present during the initial control of viral load in both horses, but the ability to maintain control correlated with Gag-GW12-specific CD8+ cells in A2171. Despite Env-RW12 dominance, Env-RW12 escape viral variants were identified in both horses and there was no correlation between Env-RW12-specific CD8+ cells and control of viral load. Although Gag-GW12 CTL escape did not occur, a Gag-GW12 epitope variant arose in A2164 that was recognized less efficiently than the original epitope. These data indicate that tetramers are useful for identification and quantitation of CTL responses in horses, and suggest that the observed control of EIAV replication and clinical disease was associated with sustained CTL recognition of Gag-specific epitopes.

Keywords: EIAV, Viral load, CD8+ lymphocyte frequency, Tetramers, CTL, CTL escape

Introduction

Equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) is a macrophage-tropic lentivirus that causes persistent infection in horses. Infected horses usually develop recurrent episodes of plasma viremia and associated acute clinical disease (fever, inappetence, lethargy, thrombocytopenia, and anemia) during the first few months of infection. However, in contrast to other lentiviral infections, including human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1), most horses control EIAV replication within a year and remain persistently infected inapparent carriers (Cheevers and McGuire, 1985; Montelaro et al., 1993; Sellon et al., 1994). Results of EIAV infection in severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) Arabian foals, as well as immune reconstitution in a SCID foal concurrent with EIAV challenge, indicate that this control of viral replication is mediated by viral-specific immune responses (Perryman et al., 1988; Crawford et al., 1996; Mealey et al., 2001). Due to robust viral-specific immune responses that contain viral replication and clinical disease, EIAV infection in horses is a useful model system for the study of lentiviral immune control.

Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I-restricted viral-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) are important for lentiviral immune control, including EIAV. Direct evidence for CD8+ lymphocyte control of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) in infected rhesus monkeys is provided by in vivo depletion of CD8+ lymphocytes with monoclonal antibody (Schmitz et al., 1999; Jin et al., 1999). Similar to HIV-1 infection, the initial plasma viremia in acute EIAV infection is often terminated concurrent with the appearance of CTL, but prior to the appearance of neutralizing antibody (McGuire et al., 1990, 1994; Borrow et al., 1994; Pantaleo and Fauci, 1995). EIAV proteins that contain CTL epitopes include Gag, Pol, Env, Rev, and S2 (Lonning et al., 1999; McGuire et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 1998; Mealey et al., 2003; Hammond et al., 1997). Several optimal CTL epitopes have been mapped, including Gag-GW12 and Env-RW12, both of which are restricted by the ELA-A1 haplotype (Mealey et al., 2003). The Env-RW12 epitope occurs within the V3 hypervariable region in the envelope SU, and in one EIAV-infected ELA-A1 horse that experienced early progressive disease, viral variants arose that escaped Env-RW12-specific CTL recognition (Mealey et al., 2003). However, since Env-RW12 occurs within the principle neutralizing domain (PND) of EIAV SU, it is possible that neutralizing antibody was involved in selection of the observed escape viral variants (Mealey et al., 2003). In contrast, viral variants containing amino acid changes within the Gag-GW12 epitope occurred in the same horse, but did not escape CTL recognition (Mealey et al., 2003). Interestingly, the equine MHC class I molecule 7-6, which was derived from a horse with the ELA-A1 haplotype, presents both the Gag-GW12 and the Env-RW12 peptides to Gag-GW12- and Env-RW12-specific CTL, respectively (McGuire et al., 2003). The 7-6 molecule binds the Env-RW12 peptide with higher affinity than the Gag-GW12 peptide (McGuire et al., 2003), and based on chromium-release assays, the Env-RW12 CTL response is immunodominant over the Gag-GW12 response (Mealey et al., 2003).

To date, analysis of EIAV-specific CTL responses has relied on standard chromium-release assays, using equine kidney cells or pokeweed mitogen-stimulated PBMC as targets (Hammond et al., 1998; McGuire et al., 1994). Although chromium-release assays provide important functional information, they are technically-demanding, labor-intensive, and utilize a radioactive isotope. Additionally, the only available method to quantitate equine CTL has been limiting dilution analysis (Kydd et al., 2003; McGuire et al., 1997; Mealey et al., 2001; O’Neill et al., 1999), which requires in vitro stimulation and is known to underestimate CTL frequency (Ogg and McMichael, 1999).

The development of MHC class I/peptide tetrameric complexes has provided a rapid method for direct identification of antigen-specific T lymphocytes in peripheral blood (Altman et al., 1996). Tetramer staining has been useful for analyzing SIV-specific CTL, correlating well with cytotoxic activity, and has allowed quantitation of dominant SIV-specific CTL responses (Egan et al., 1999). Studies using tetramers have confirmed that the emergence of CTL coincides with clearance of virus during SIV infection (Kuroda et al., 1999), and that HIV-specific CTL frequency and plasma viral load are inversely correlated (Ogg et al., 1998), suggesting that CTL play a significant role in controlling HIV infection. However, other work has indicated that the inverse correlation between tetramer-positive CD8+ T cells and viral load does not exist in HIV-1-infected patients with low CD4+ T cell numbers, providing evidence that tetramer-positive cells can have impaired function, verified by measuring IFN-γ production (Kostense et al., 2001). In HIV-1-infected children, CTL frequency as measured by IFN-γ ELISPOT correlates positively with viral load and is lower than that determined by tetramer staining, again indicating that a significant number of HIV-1-specific CD8+ T cells are not functional (Buseyne et al., 2002). Similarly, intracytoplasmic IFN-γ staining has shown that total HIV-1-specific CD8+ responses correlate positively with viral load, suggesting that frequencies of HIV-1-specific CD8+ T cells are not the sole determinant of HIV-1 immune control (Betts et al., 2001). In contrast, standard chromium-release assays have shown an inverse correlation between HIV-1-specific CTL activity and viral load in HIV-1-infected long-term survivors (Betts et al., 1999).

Interpreting the correlations between lentiviral load and lentivirus-specific CTL frequency, whether measured by chromium-release assay, tetramer staining, IFN-γ ELISPOT, or intracytoplasmic IFN-γ staining, remains difficult. Positive correlations likely indicate viral replication driving CTL expansion, or alternatively, that CTL are not effectively controlling viral load. Negative correlations could indicate effective CTL-mediated viral control, or alternatively, virus-mediated immunosuppression. With respect to the latter, transient immunosuppression associated with febrile episodes is known to occur during EIAV infection (Murakami et al., 1999; Newman et al., 1991).

The purpose of the present study was to determine the relationship between CTL response and viral load during early EIAV infection. Two tetramers, 7-6/Gag-GW12 and 7-6/Env-RW12, were constructed to allow direct quantitation of Gag-GW12- and Env-RW12-specific CD8+ lymphocytes during the first 127 days of EIAV infection in two horses (A2164 and A2171) sharing the ELA-A1 haplotype. Chromium-release assays were also performed to confirm functional cytotoxic activity. In addition, neutralizing antibody responses were measured, and plasma virus was cloned and sequenced to determine if CTL escape variants arose. Results indicated that although both horses terminated the initial viremic peak, viral control was transient in A2164, whereas only horse A2171 effectively controlled viral load and clinical disease during the 127-day observation period. An inverse correlation between Gag-GW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency and viral load was associated with control of plasma viremia and clinical disease in horse A2171. There was no correlation between viral control and Env-RW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency, despite the immunodominance of the Env-RW12-specific response. Although plasma viral variants that escaped Env-RW12 CTL occurred in both horses, Gag-GW12 escape did not occur. However, a Gag-GW12 CTL epitope variant arose in A2164 that was recognized less efficiently than the original epitope. Interestingly, neutralizing antibody was present during the initial control of viral load in both horses, but neutralizing antibody activity was not associated with the ability to maintain viral control. It was concluded that tetramers are useful for quantitating EIAV-specific CTL responses in horses, and that viral escape limits the effectiveness of an immunodominant Env-RW12 CTL response. In addition, the data suggested that Gag-specific CTL responses are important for immune control of EIAV.

Results

7-6/Env-RW12 and 7-6/Gag-GW12 tetramers identified peptide-specific CD8+ cells in EIAV-infected horses

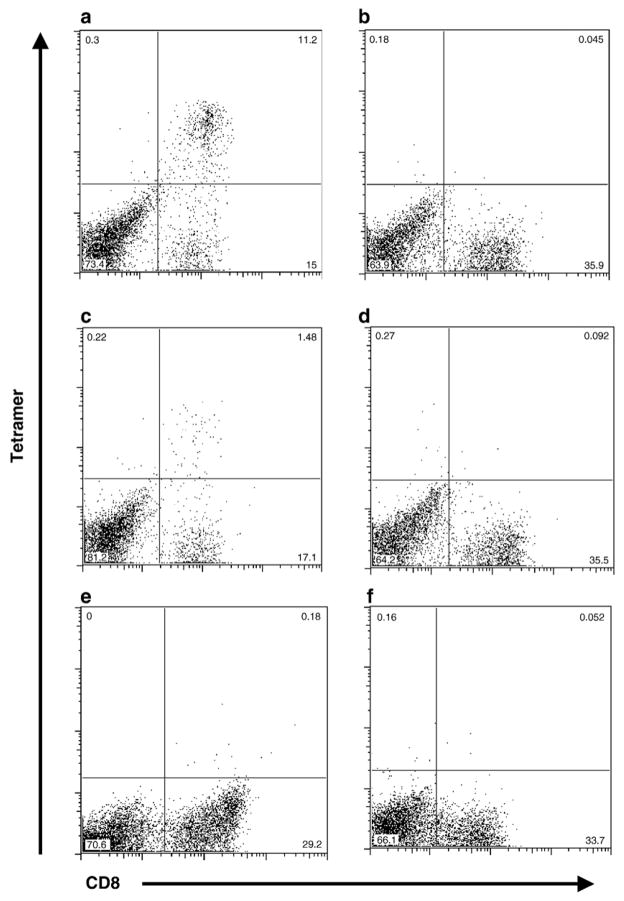

Stimulated PBMC from EIAV-infected ELA-A1 horse A2140, which contain 7-6-restricted Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12 CTL (Mealey et al., 2003), were used to confirm the specificity of the 7-6/Env-RW12 and 7-6/Gag-GW12 tetramers. Stimulated PBMC from EIAV-infected ELA-A4 horse A2147, which do not contain Env-RW12 or Gag-GW12 CTL, but do contain ELA-A4-restricted Gag-FK10 CTL (Mealey et al., 2003), were used as negative controls. Prior to use, 2-fold dilutions of the stock tetramers were made to determine the optimal concentration for staining. For the 7-6/Env-RW12 tetramer, a 1:32 dilution was considered optimal since the lowest number of CD8− cells were labeled at this concentration (Fig. 1). Similar results were obtained for the 7-6/Gag-GW12 tetramer (data not shown). Both the 7-6/Env-RW12 and 7-6/Gag-GW12 tetramers labeled CD8+ cells in A2140 PBMC stimulated with Env-RW12 (Fig. 2a) or Gag-GW12 peptides (Fig. 2c), but not in A2147 PBMC stimulated with Gag-FK10 peptide (Figs. 2b,d). Chromium-release CTL assays confirmed that Env-RW12- and Gag-GW12-specific CTL were present in the stimulated A2140 PBMC, and that Gag-FK10-specific CTL were present in the stimulated A2147 PBMC (data not shown). Lastly, the 7-6/Env-RW12 tetramer did not bind Gag-GW12-stimulated A2140 PBMC (Fig. 2e), and the 7-6/Gag-GW12 tetramer did not bind Env-RW12-stimulated A2140 PBMC (Fig. 2f). These results indicated that tetramer binding to equine CD8+ cells was both peptide and MHC class I-specific.

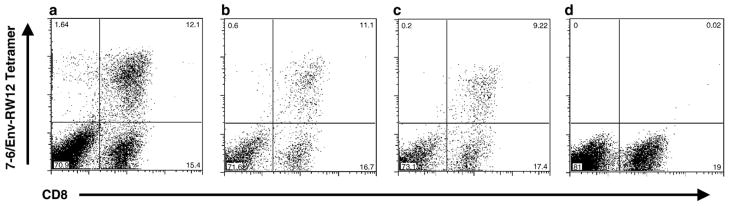

Fig. 1.

PBMC from EIAV-infected horse A2140, stimulated for 7 days with 10 μM Env-RW12 peptide, then labeled with anti-equine CD8 and the following serial dilutions of the 7-6/Env-RW12 tetramer: (a) 1:8; (b) 1:16; (c) 1:32; (d) no tetramer.

Fig. 2.

(a) PBMC from EIAV-infected horse A2140, stimulated for 7 days with Env-RW12 peptide, then labeled with anti-equine CD8 and the 7-6/Env-RW12 tetramer. (b) PBMC from EIAV-infected horse A2147, stimulated for 7 days with Gag-FK10 peptide, then labeled with anti-equine CD8 and the 7-6/Env-RW12 tetramer. (c) A2140 PBMC stimulated for 7 days with Gag-GW12 peptide, then labeled with anti-equine CD8 and the 7-6/Gag-GW12 tetramer. (d) Gag-FK10-stimulated A2147 PBMC labeled with anti-equine CD8 and the 7-6/Gag-GW12 tetramer. (e) Gag-GW12-stimulated A2140 PBMC labeled with anti-equine CD8 and the 7-6/Env-RW12 tetramer. (f) Env-RW12-stimulated A2140 PBMC labeled with anti-equine CD8 and the 7-6/Gag-GW12 tetramer.

Progressive clinical disease and high viral loads occurred in EIAV-infected horse A2164, but not in EIAV-infected horse A2171

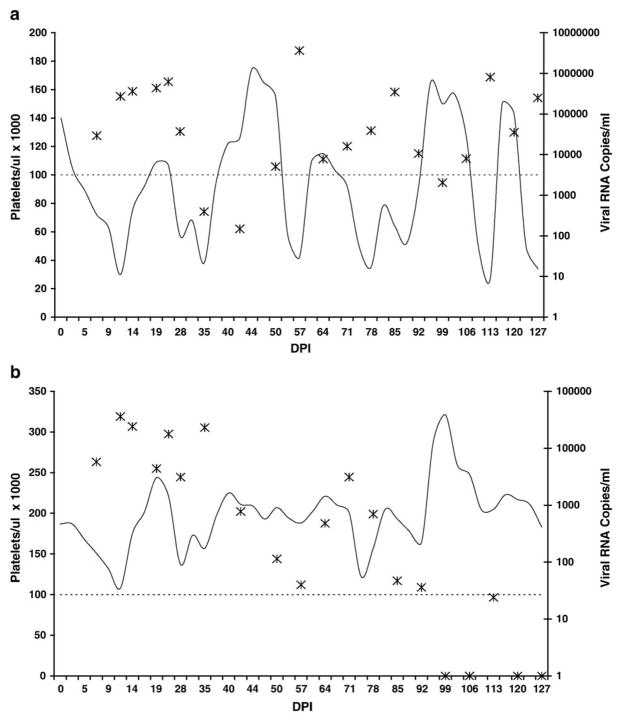

During the first 127 days post-EIAV inoculation (DPI), A2164 had six clinical disease episodes (I, DPI 5–16; II, DPI 28–37; III, DPI 56–57; IV, DPI 71–92; V, DPI 11–113; and VI, DPI 125–127) (Fig. 3a). All six episodes were associated with thrombocytopenia, and fever occurred during episodes III, V, and VI. Plasma viral RNA was detected during each episode, with peak viral load (3.6 × 106 RNA copies/ml) occurring during episode III. In contrast, A2171 had no clinical disease episodes during the same time period (Fig. 3b). Peak plasma viral load (3.6 × 104 RNA copies/ml) was 100-fold lower than that for A2164, and occurred 12 DPI. Interestingly, plasma viral loads after DPI 50 were maintained at different levels in the two horses (Table 1, Fig. 4). In A2171, viral load transiently increased on DPI 71 (3.1 × 103 RNA copies/ml), but decreased thereafter and was completely controlled by DPI 127. In contrast, A2164 plasma viral load was maintained between 2 × 103 and 3.6 × 106 RNA copies/ml.

Fig. 3.

(a) Platelet counts (solid line) and plasma viral load (asterisks) in EIAV-infected horse A2164. The dotted line indicates the cutoff for thrombocytopenia (100,000 platelets/μl). DPI, days post-EIAV inoculation. (b) Platelet counts and plasma viral load in EIAV-infected horse A2171. Annotations are the same as for panel a.

Table 1.

Plasma viral load and Env-RW12- and Gag-GW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency and cytotoxicity in A2171 and A2164

| DPIa | A2171

|

A2164

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma viral load (RNA copies/ml) | % Tetramer + CD8+ cells

|

Cytotoxicityb |

Plasma viral load (RNA copies/ml) | % Tetramer + CD8+ cells

|

Cytotoxicityb |

|||||

| 7-6/Env-RW12 | 7-6/Gag-GW12 | Env-RW12 | Gag-GW12 | 7-6/Env-RW12 | 7-6/Gag-GW12 | Env-RW12 | Gag-GW12 | |||

| −19 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 7 | 5754 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.77 | 0.00 | 29,190 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 1.60 | 0.11 |

| 14 | 24,150 | 0.68 | 0.36 | 25.21 | 5.87 | 362,460 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 19 | 4410 | 1.42 | 0.16 | 31.91 | 6.35 | 436,800 | 3.70 | 0.00 | 0.46 | 0.59 |

| 28 | 3121 | 2.38 | 0.09 | 38.77 | 27.94 | 37,086 | 1.93 | 0.00 | 38.19 | 9.17 |

| 35 | 23,100 | 3.94 | 0.84 | 40.49 | 34.98 | 394 | 4.61 | 0.08 | 28.75 | 18.49 |

| 42 | 773 | 4.62 | 2.19 | 50.64 | 43.20 | 149 | 5.86 | 0.73 | 44.26 | 36.13 |

| 57 | 40 | 3.41 | 1.15 | 29.14 | 16.18 | 3,649,800 | 1.84 | 0.29 | 12.64 | 1.60 |

| 71 | 3116 | 3.28 | 0.81 | 36.41 | 41.42 | 16,044 | 1.42 | 0.13 | 20.86 | 8.50 |

| 85 | 47 | 1.92 | 0.71 | 35.03 | 38.02 | 347,340 | 0.00 | 0.58 | 32.37 | 21.86 |

| 99 | 0 | 6.68 | 2.73 | 43.54 | 24.30 | 2041 | 2.96 | 1.35 | 42.28 | 11.10 |

| 127 | 0 | 3.00 | 1.23 | 52.66 | 63.35 | 250,320 | 0.80 | 0.44 | 20.61 | 35.77 |

Days post-EIAV inoculation.

% specific lysis of Env-RW12 or Gag-GW12 peptide-pulsed ELA-A1-matched equine kidney target cells using PBMC effectors stimulated for 7 days with Env-RW12 or Gag-GW12 peptides.

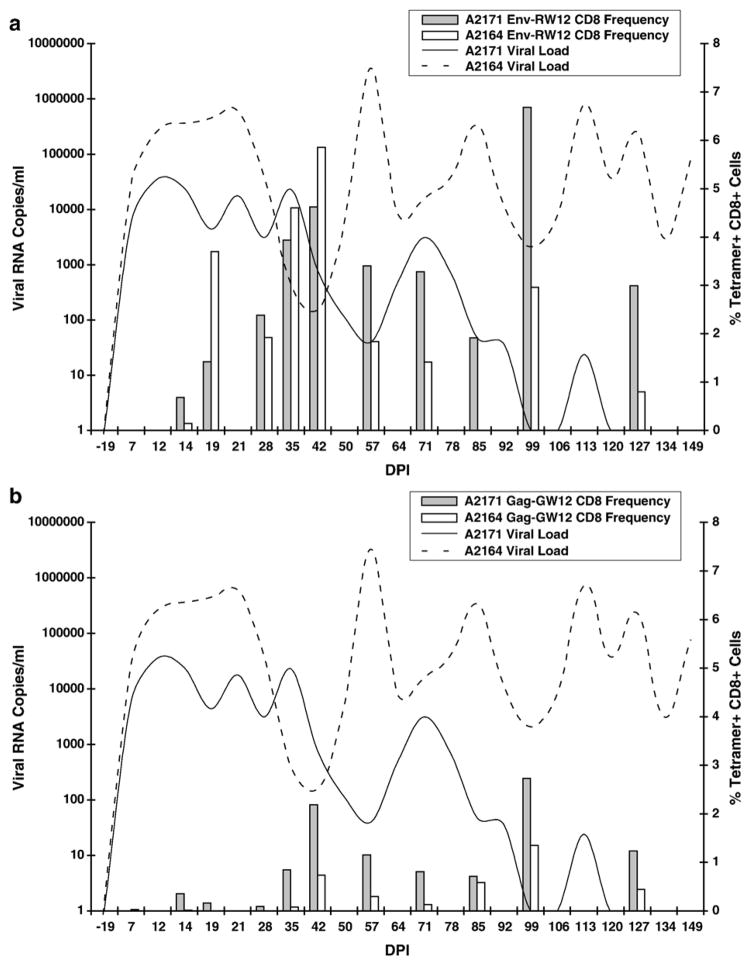

Fig. 4.

(a) Plasma viral load in A2164 (dotted line) and A2171 (solid line), and Env-RW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency (percentage of CD8+ nonstimulated PBMC that were 7-6/Env-RW12 tetramer positive) in A2164 (white bars) and A2171 (gray bars). DPI, days post-EIAV inoculation. (b) Plasma viral load in A2164 (dotted line) and A2171 (solid line), and Gag-GW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency (percentage of CD8+ nonstimulated PBMC that were 7-6/Gag-GW12 tetramer positive) in A2164 (white bars) and A2171 (gray bars).

Env-RW12- and Gag-GW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency in nonstimulated PBMC from EIAV-infected horses A2171 and A2164

In horse A2171, Env-RW12-specific CD8+ cells were first detected 14 DPI, with 0.7% of nonstimulated peripheral blood CD8+ cells binding the 7-6/Env-RW12 tetramer (Fig. 4a, Table 1). Env-RW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency increased to 4.6% on DPI 42, and reached a peak of 6.7% on DPI 99. In horse A2164, Env-RW12-specific CD8+ cells were also first detected 14 DPI, with 0.2% of nonstimulated peripheral blood CD8+ cells binding the 7-6/Env-RW12 tetramer. Env-RW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency fluctuated in A2164, reaching a peak of 5.9% on DPI 42. With the exception of DPI 19, 35, and 42, Env-RW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency was lower in A2164 than in A2171. Env-RW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency was always higher in A2171 than in A2164 after DPI 50, when viral load was more effectively controlled in A2171.

In horse A2171, Gag-GW12-specific CD8+ cells were first detected 14 DPI, with 0.4% of nonstimulated peripheral blood CD8+ cells binding the 7-6/Gag-GW12 tetramer (Fig. 4b, Table 1). Tetramer-binding Gag-GW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency increased to 2.2% on DPI 42, and reached a peak of 2.7% on DPI 99. In horse A2164, Gag-GW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency remained between 0.0% and 0.08% until DPI 42, when 0.7% of nonstimulated peripheral blood CD8+ cells bound the 7-6/Gag-GW12 tetramer. Gag-GW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency reached a peak of 1.4% (DPI 99) in A2164, and remained lower than in A2171 at all time-points.

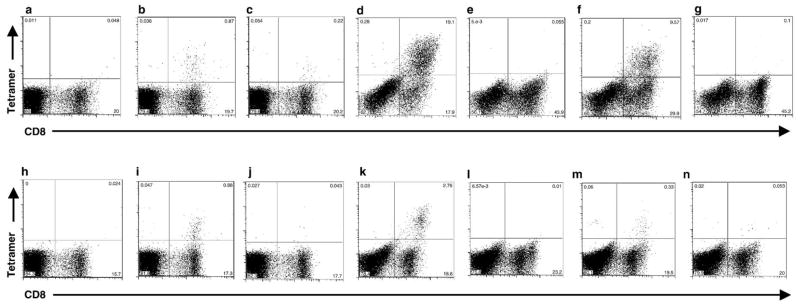

To confirm that the tetramers bound peptide-specific CD8+ cells in both horses, PBMC from A2164 and A2171 were stimulated for 7 days with the Gag-GW12 and Env-RW12 peptides. The 7-6/Env-RW12 tetramer did not bind CD8+ cells in PBMC stimulated with the Gag-GW12 peptide, and the 7-6/Gag-GW12 tetramer did not bind CD8+ cells in PBMC stimulated with the Env-RW12 peptide (Fig. 5), confirming that both tetramers identified only peptide-specific CD8+ cells.

Fig. 5.

Representative anti-equine CD8 and tetramer staining for DPI 35 PBMC from A2171 (a–g) and A2164 (h–n). (a, h) Nonstimulated PBMC with no tetramer labeling. (b, i) Nonstimulated PBMC labeled with the 7-6/Env-RW12 tetramer. (c, j) Nonstimulated PBMC labeled with the 7-6/Gag-GW12 tetramer. (d, k) Env-RW12-stimulated PBMC labeled with the 7-6/Env-RW12 tetramer. (e, l) Env-RW12-stimulated PBMC labeled with the 7-6/Gag-GW12 tetramer. (f, m) Gag-GW12-stimulated PBMC labeled with the 7-6/Gag-GW12 tetramer. (g, n) Gag-GW12-stimulated PBMC labeled with the 7-6/Env-RW12 tetramer.

Env-RW12- and Gag-GW12-specific cytotoxic activity in EIAV-infected horses A2171 and A2164

Env-RW12-specific cytotoxicity with specific lysis greater than 10% over background (obtained using targets not pulsed with peptide) was not detected in nonstimulated PBMC at any time-point in either horse, indicating that the tetramer was more sensitive than chromium-release assays in detecting nonstimulated peripheral blood Env-RW12-specific CD8+ cells. However, Env-RW12-specific cytotoxicity was detected in Env-RW12-stimulated PBMC from both horses, and was higher in A2171 at all time-points assayed (Table 1).

Gag-GW12-specific cytotoxicity with specific lysis greater than 10% over background was not detected in nonstimulated PBMC at any time-point in either horse, with the exception of DPI 127 in A2171. As with Env-RW12, the tetramer was more sensitive than chromium-release assays in detecting nonstimulated peripheral blood Gag-GW12-specific CD8+ cells. On most days assayed after DPI 28, Gag-GW12-specific cytotoxicity was detected in Gag-GW12-stimulated PBMC from both horses, and was always higher in A2171 (Table 1).

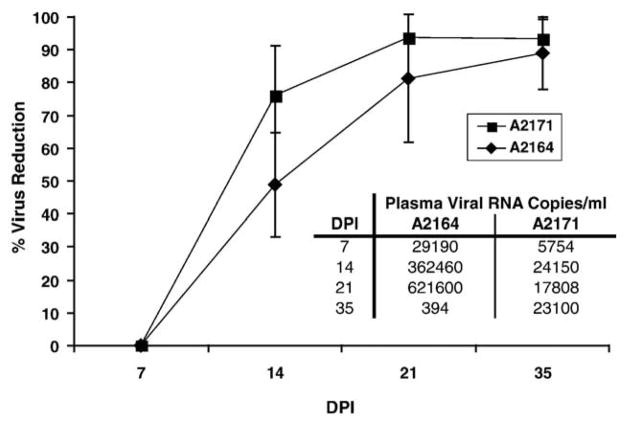

Sustained control of viral load correlated with Gag-GW12-specific, but not Env-RW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency, and was not associated with neutralizing antibody activity

In A2171 (which controlled viral load and clinical disease), viral load inversely correlated with Gag-GW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency ( P = 0.0308, r = −0.6489), while no correlation was observed between viral load and Env-RW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency. In horse A2164 (which did not control viral load or clinical disease), no correlation was observed between viral load and Gag-GW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency. Although viral load inversely correlated with Env-RW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency ( P = 0.0216, r = −0.6789) in A2164, this immunodominant Env-RW12-specific CD8+ response was not effective in limiting viral replication. In both horses, neutralizing antibody was detected very early (DPI 14) in plasma, with ≥90% virus reduction by DPI 35 (Fig. 6). Although neutralizing antibody activity was higher in A2171 than in A2164 for all days assayed, the difference was not significant (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Neutralizing antibody activity in A2164 and A2171, determined by incubating equal volumes of test plasma with EIAV stock virus followed by titration in cell culture. % virus reduction was calculated by subtracting the TCID50 obtained using test plasma from the TCID50 obtained using negative control plasma, and dividing the result by the TCID50 obtained using negative control plasma. The end result was multiplied by 100. Each data point represents the mean of three separate assays. Error bars are 2 SD. DPI, days post-EIAV inoculation. Plasma viral loads (viral RNA copies/ml) for A2164 and A2171 on the days assayed for neutralizing antibody are tabulated for reference.

Recognition of Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12 CTL epitope plasma virus variants

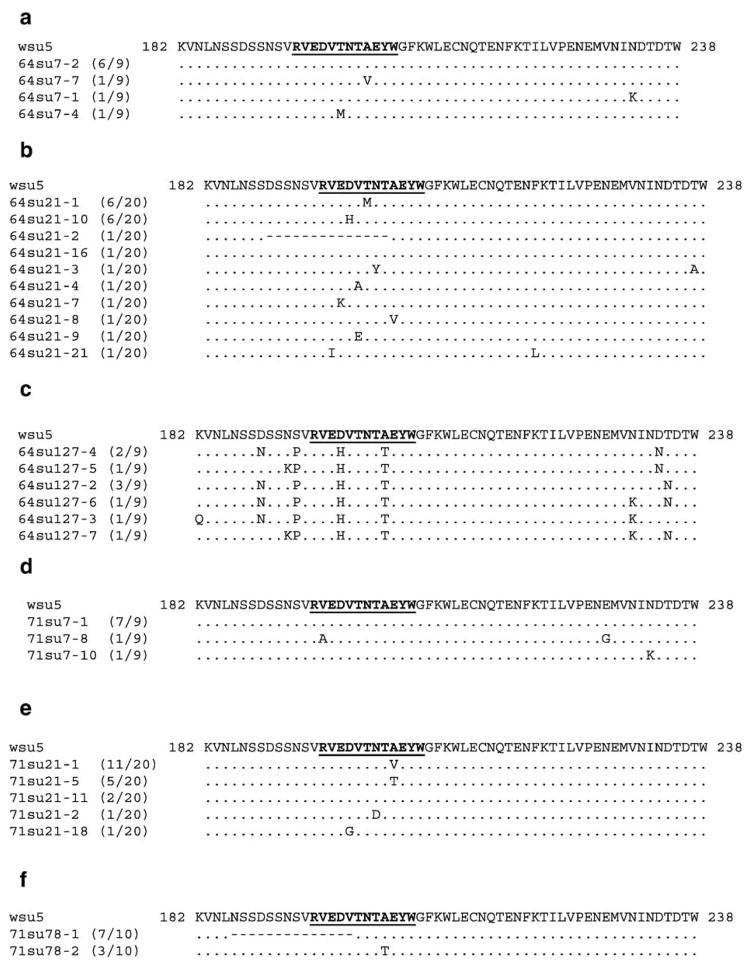

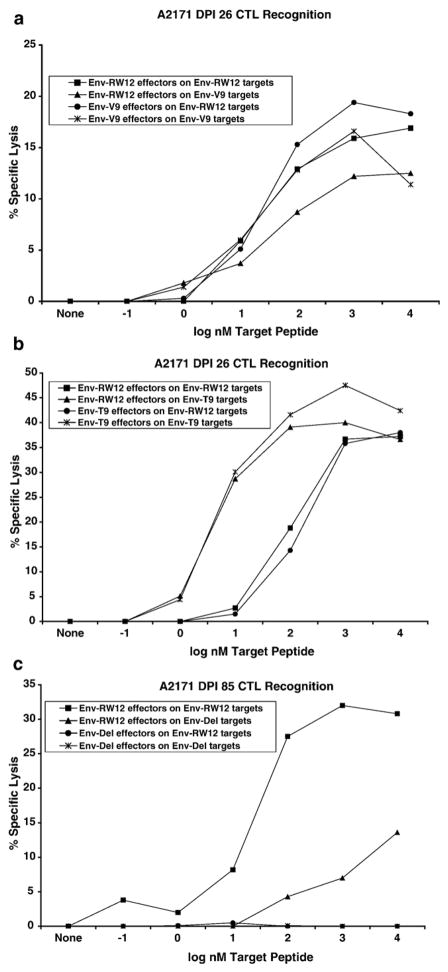

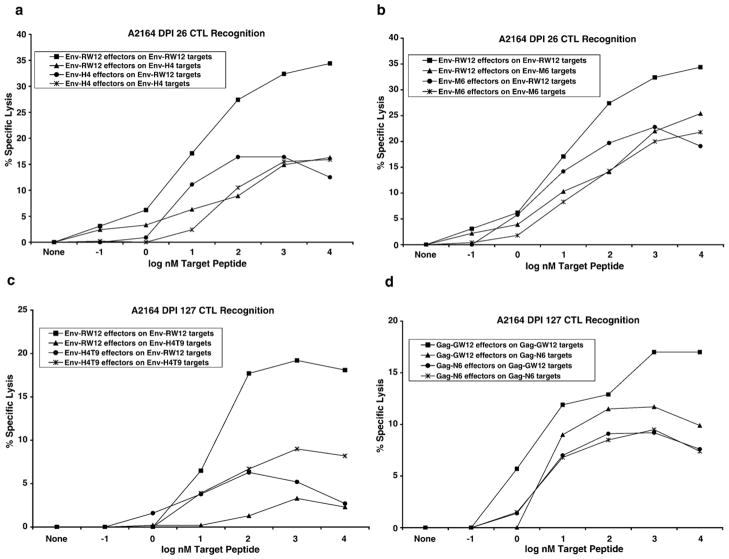

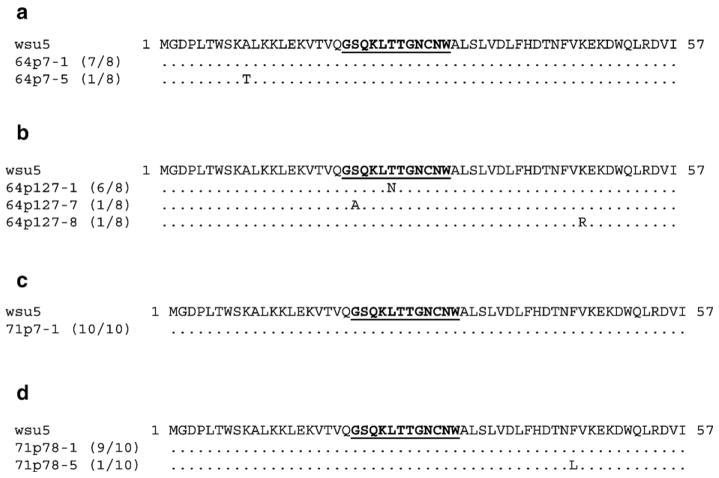

To determine if CTL escape contributed to the uncontrolled viral replication in A2164, segments of plasma viral genes which included the coding regions for the Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12 CTL epitopes were cloned and sequenced. In DPI 7 plasma from both horses, amino acid changes were not present within the Env-RW12 epitope in the majority of clones (Figs. 7a,d). However, amino acid changes were present within the Env-RW12 epitope in DPI 21 plasma from both horses (Fig. 7b,e). For A2171, the predominant DPI 21 Env-RW12 variant peptide RVEDVTNTVEYW (11/20 clones; Fig. 7b), designated Env-V9, was synthesized and used to pulse target cells in a chromium-release assay. Although Env-RW12-stimulated CTL effectors derived from A2171 DPI 26 cryopreserved PBMC recognized Env-V9, recognition was less efficient than that for Env-RW12 (Fig. 8a). Env-V9-stimulated effectors displayed similar recognition of Env-RW12 and Env-V9, indicating that Env-V9 was not an escape variant. Although the RVEDVTNTTEYW variant (designated Env-T9) was of low frequency in A2171 DPI 21 plasma (5/20 clones), it was actually recognized more efficiently by Env-RW12 and Env-T9-stimulated effectors than was the original Env-RW12 epitope (Fig. 8b). For A2164, the DPI 21 cloned sequences revealed changes or deletions in several different Env-RW12 amino acids, but the RVEHVTNTAEYW (6/20 clones), designated Env-H4, and the RVEDVMNTAEYW (6/20 clones), designated Env-M6, were predominant (Fig. 7e). Using CTL effectors derived from A2164 DPI 26 cryopreserved PBMC, both Env-H4 and Env-M6 were recognized, but less efficiently than Env-RW12 (Figs. 9a,b). By DPI 127, 100% of the cloned sequences from A2164 plasma contained an RVEHVTNTTEYW variant sequence (Fig. 7c), designated Env-H4T9, that was not recognized by DPI 127 cryopreserved CTL and was thus an escape variant (Fig. 9c). In contrast to A2164, plasma viral RNA was not detected in A2171 on DPI 127, indicating effective control of viral replication. However, on DPI 78 (the last day viral RNA could be recovered from A2171 plasma in sufficient quantities to clone and sequence), the majority of clones (7/10) contained a 14 amino acid deletion that eliminated the first 5 residues of Env-RW12 (Fig. 7f). This variant (designated Env-Del) was recognized at a low level and only at the highest peptide concentration by DPI 85 cryopreserved Env-RW12-stimulated CTL, and was therefore considered an escape variant (Fig. 8c).

Fig. 7.

(a) Deduced amino acid sequences of EIAVWSU5 SU env clones (SU amino acids 182–238) obtained from A2164 DPI 7 plasma. The EIAVWSU5 consensus sequence (GenBank accession no. AF247394) is shown and the Env-RW12 CTL epitope is in bold and underlined. The number of clones with a given sequence over the total number of sequenced clones is indicated in parentheses to the right of the clone name. (b) Deduced amino acid sequences of EIAVWSU5 SU env clones obtained from A2164 DPI 21 plasma. Annotations are the same as for panel a. (c) Deduced amino acid sequences of EIAVWSU5 SU env clones obtained from A2164 DPI 127 plasma. Annotations are the same as for panel a. (d) Deduced amino acid sequences of EIAVWSU5 SU env clones obtained from A2171 DPI 7 plasma. Annotations are the same as for panel a. (e) Deduced amino acid sequences of EIAVWSU5 SU env clones obtained from A2171 DPI 21 plasma. Annotations are the same as for panel a. (f) Deduced amino acid sequences of EIAVWSU5 SU env clones obtained from A2171 DPI 78 plasma. Annotations are the same as for panel a.

Fig. 8.

A2171 CTL recognition of ELA-A1-matched equine kidney (EK) target cells pulsed with original or epitope variant peptides. Chromium-release assays used EK targets pulsed with increasing concentrations of each peptide (10−1 to 104 nM), and an effector:target ratio of 20:1. Effectors were cryopreserved PBMC stimulated for 7 days with the original or the variant epitope peptides. Specific lysis values are shown after subtraction of background (specific lysis of targets not pulsed with peptide). (a) DPI 26 CTL recognition of the original epitope peptide Env-RW12 (RVEDVTN-TAEYW) and the DPI 21 plasma virus epitope variant Env-V9 (RVEDVTNTVEYW). (b) DPI 26 CTL recognition of the original epitope peptide Env-RW12 and the DPI 21 plasma virus epitope variant Env-T9 (RVEDVTNTTEYW). (c) DPI 85 CTL recognition of the original epitope peptide Env-RW12 and the DPI 78 plasma virus epitope variant Env-Del (KKVNLTNTAEYW).

Fig. 9.

A2164 CTL recognition of ELA-A1-matched equine kidney (EK) target cells pulsed with original or epitope variant peptides. Chromium-release assays used EK targets pulsed with increasing concentrations of each peptide (10−1 to 104 nM), and an effector:target ratio of 20:1. Effectors were cryopreserved PBMC stimulated for 7 days with the original or the variant epitope peptides. Specific lysis values are shown after subtraction of background (specific lysis of targets not pulsed with peptide). (a) DPI 26 CTL recognition of the original epitope peptide Env-RW12 and the DPI 21 plasma virus epitope variant Env-H4 (RVEHVTNTAEYW). (b) DPI 26 CTL recognition of the original epitope peptide Env-RW12 and the DPI 21 plasma virus epitope variant Env-M6 (RVEDVMNTAEYW). (c) DPI 127 CTL recognition of the original epitope peptide Env-RW12 and the DPI 127 plasma virus epitope variant Env-H4T9 (RVEHVTNTTEYW). (d) DPI 127 CTL recognition of the original epitope peptide Gag-GW12 (GSQKLTTGNCNW) and the DPI 127 plasma virus epitope variant Gag-N6 (GSQKLNTGNCNW).

Limited variation was observed within the Gag-GW12 epitope in cloned plasma viral sequences from both horses. None of the DPI 7 clones from either horse had amino acid changes within Gag-GW12 (Figs. 10a,c), nor did any of the clones from DPI 78 plasma from A2171 (Fig. 10d). However, 6/8 clones had a GSQKLNTGNCNW variant sequence in DPI 127 plasma from A2164 (Fig. 10b). This variant, designated Gag-N6, was recognized less efficiently than Gag-GW12 by A2164 DPI 127 cryopreserved CTL (Fig. 9d).

Fig. 10.

(a) Deduced amino acid sequences of EIAVWSU5 gag clones (Gag amino acids 1–57) obtained from A2164 DPI 7 plasma. The EIAVWSU5 consensus sequence (GenBank accession no. AF247394) is shown and the Gag-GW12 CTL epitope is in bold and underlined. Other annotations are the same as for Fig. 7a. (b) Deduced amino acid sequences of EIAVWSU5 gag clones obtained from A2164 DPI 127 plasma. Annotations are the same as for panel a. (c) Deduced amino acid sequences of EIAVWSU5 gag clones obtained from A2171 DPI 7 plasma. Annotations are the same as for panel a. (d) Deduced amino acid sequences of EIAVWSU5 gag clones obtained from A2171 DPI 78 plasma. Annotations are the same as for panel a.

Discussion

This study describes the development and use of the first tetramers that identify antigen-specific CD8+ cells in the horse. The Gag-GW12- and Env-RW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency and functional CTL activity were evaluated using tetramer staining and standard chromium-release assays during the initial 127 days post-EIAV inoculation in two horses (A2171 and A2164) sharing the ELA-A1 haplotype. In addition, neutralizing antibody responses were evaluated using a virus reduction method. Both horses developed an initial peak viremia 12–19 DPI, which both horses terminated. However, only horse A2171 maintained efficient control of viral load. This horse had more robust Gag-GW12- and Env-RW12-specific CTL responses, and higher frequencies of Gag-GW12- and Env-RW12-specific CD8+ cells than did A2164. Interestingly, control of viral load by horse A2171 correlated with Gag-GW12-specific, but not Env-RW12-specific CD8+ cell frequency, despite the dominance of the Env-RW12 response. This was likely due to Env-RW12 escape viral variants, which were identified in both horses. Although Gag-GW12 CTL escape did not occur, a Gag-GW12 epitope variant arose in A2164 that was recognized less efficiently than the original epitope.

The 7-6/Env-RW12 and 7-6/Gag-GW12 tetramers allowed efficient and early determination of antigen-specific CD8+ cell frequency in EIAV-infected horses sharing the ELA-A1 haplotype. Both tetramers bound CD8+ cells in a peptide-specific, MHC class I-specific manner, and both tetramers were more sensitive than chromium-release assays in identifying antigen-specific, MHC class I-restricted CD8+ cells in nonstimulated PBMC. The tetramers likely identified functional CD8+ cells since chromium-release assays confirmed CTL activity in the same population of PBMC following peptide stimulation. Although reagents for performing other CD8+ T lymphocyte functional assays in the horse are available (Breathnach et al., 2005; Hines et al., 2003; Pedersen et al., 2002), chromium-release assays were used because they provide results with direct functional relevance that are comparable to those obtained by ELISPOT or intracytoplasmic IFN-γ staining (Michel et al., 2002; Sun et al., 2003). Additionally, these other functional assays have not yet been optimized for use in the EIAV system. In general, the timing and magnitude of the CTL responses as determined by the tetramers used in this study were in agreement with those observed in SIV-infected rhesus monkeys (Egan et al., 1999; Kuroda et al., 1998).

The early neutralizing antibody responses in A2171 and A2164 were unexpected. We have previously used virus reduction assays to identify neutralizing antibody activity as early as 45 DPI in an EIAVWSU5-infected Arabian horse (Mealey et al., 2003). Other studies have reported EIAV-specific neutralizing antibody as early as 38 DPI (Kono, 1969), 44 DPI (Salinovich et al., 1986), 52 DPI (Carpenter et al., 1987), and between 2 and 3 months post-inoculation (Hammond et al., 1997, 2000; Howe et al., 2002; Leroux et al., 1997; O’Rourke et al., 1989). Differences in assay sensitivity, virus strain, inoculation dose, and MHC class II haplotypes might explain the discrepancies in these results. Analysis of EIAV SU envelope sequences derived from SCID and immunocompetent foals within 35 DPI indicates that adaptive immune selection of SU variants occurs early during infection (Mealey et al., 2004), and indirectly corroborates the early appearance of neutralizing antibody observed in the present study. Moreover, neutralizing antibody can be detected as early as 14 DPI in SIV-infected rhesus monkeys (Schmitz et al., 2003). Depletion of B lymphocytes in these monkeys results in a delayed neutralizing antibody response, but does not affect the rapid decline of peak plasma viremia during the first 3 weeks of infection. However, an inverse correlation exists between neutralizing antibody titer and plasma virus level, suggesting that neutralizing antibody contributes to the control of SIV replication during the post-acute phase of infection (Schmitz et al., 2003). In the present study, the similar levels of neutralizing antibody in A2171 and A2164 suggested that the observed differences in viral load and clinical disease were due to differences in CTL-mediated control of EIAV replication. However, qualitative differences in the early neutralizing antibody responses may have contributed to the differences in viral load and clinical disease observed in A2171 and A2164.

Based on tetramer staining and CTL activity, the Env-RW12 response was dominant over the Gag-GW12 response in both horses. However, epitope variants arose in both horses that eventually escaped recognition by Env-RW12 CTL. Nonetheless, the Env-RW12-specific CTL response may have been important in the early control of viral load, prior to the appearance of escape variants. Although the immunodominant Env-RW12 response is composed of high avidity CTL, Env-RW12 escape occurs and is correlated with progressive disease (Mealey et al., 2003). Similarly, high avidity CTL rapidly select for escape variants following acute SIV infection in rhesus monkeys (O’Connor et al., 2002). Given that the high avidity immunodominant Env-RW12 CTL are directed against the highly variable V3 region of EIAV SU, it is not surprising that there was no correlation between viral load and Env-RW12 frequency in A2171. Since the V3 region is a target for neutralizing antibody (Ball et al., 1992), neutralizing antibody selection pressure may have contributed to the appearance of Env-RW12 epitope variants. The enhanced recognition of the Env-T9 epitope variant in A2171 was interesting, and was likely the reason this variant was present in low numbers. The enhanced recognition could have been due to higher affinity binding to the TCR, higher affinity binding to MHC class I, or a combination of both. Epitope variants that are recognized more efficiently than the original CTL epitope have been previously observed in an EIAV-infected horse (Mealey et al., 2003). Although an inverse correlation existed between viral load and Env-RW12 frequency in A2164, this correlation was not associated with viral control. Instead, it is likely that this negative correlation was due to immune suppression associated with uncontrolled viral replication in A2164, especially since Env-RW12 CD8+ cell frequency was lower in A2164 than in A2171 at most time-points assayed. Immunosuppression is known to occur during febrile episodes in EIAV-infected horses (Murakami et al., 1999; Newman et al., 1991).

An inverse correlation between Gag-GW12 frequency and viral load was observed in A2171 but not in A2164. This suggested that Gag-GW12 CTL contributed to control of viral replication and clinical disease in A2171. The p15 region of Gag (which contains Gag-GW12), is more highly conserved than the V3 region of SU, which contains Env-RW12 (Chung et al., 2004; Leroux et al., 1997; Mealey et al., 2003, 2004). In addition, this region of Gag contains CTL epitope clusters that are recognized by horses with disparate MHC class I backgrounds (Chung et al., 2004), and is likely an important target for protective CTL responses. Unlike Env-RW12, Gag-GW12 variants did not occur in A2171. However, an amino acid change within the epitope resulted in less efficient CTL recognition in A2164. The lower Gag-GW12 frequency combined with Gag-GW12 epitope variation could have contributed to the higher viral load and progressive disease observed in A2164. Further studies with additional horses are needed to confirm these observations.

Although A2164 and A2171 shared the ELA-A1 haplotype, differences were observed in Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12 CD8+ cell frequency and functional CTL activity. These differences were likely due to MHC class II disparity, resulting in recognition of different helper epitopes and subsequent dissimilar CTL priming efficiency and maintenance. The differences in neutralizing antibody activity could have a similar explanation. Additionally, since these horses were not ELA-A1 homozygotes, other MHC class I alleles could have contributed to CTL responses that were not measured. It is therefore possible that CTL other than Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12 were involved in the more efficient control of viral load and clinical disease observed in A2171.

The results obtained in this study suggest that neutralizing antibody and CTL directed against variable EIAV envelope epitopes are important in the control of initial viremia, but are not sufficient for sustained control due to viral escape. Although the Gag-GW12 CTL response was subdominant to the Env-RW12 CTL response in the horses of this study, Gag-GW12 epitope escape did not occur in A2171, and this response correlated with sustained control of plasma viremia and clinical disease in A2171. Further work with tetramers could verify these observations. These data should be useful in designing protective vaccines against EIAV in horses, and may have similar implications for designing protective vaccines against other lentiviruses. In addition, MHC class I/peptide tetramers proved useful for identifying and quantifying early antigen-specific CD8+ cell responses in the horse, and the development of additional tetramers will enable a more complete analysis of EIAV-specific CTL responses in additional horses.

Materials and methods

Horses

Two Arabian 2-year-old horses, A2164 and A2171, were inoculated intravenously with 107 50% tissue culture infective doses (TCID50) of the WSU5 strain of EIAV (O’Rourke et al., 1989). The equine leukocyte alloantigen (ELA)-A types were determined serologically (Bailey, 1980) with reagents kindly provided by Dr. Ernest Bailey (University of Kentucky), and were A1/w11 for A2164, and A1/ A4 for A2171. Rectal temperature and clinical status were recorded daily, and for the first 7 weeks post-infection, platelet counts were performed on whole blood collected every 2 days, then twice weekly thereafter. Clinical disease episodes were defined when thrombocytopenia (platelet count < 100,000/μl), with or without fever (rectal temperature > 101.5 °F), occurred on at least 2 consecutive collection days. For determination of viral load, plasma was collected and stored at −80 °C every 2 days for the first 7 weeks post-infection, then twice weekly thereafter. Heparinized whole blood was collected weekly for isolation of PBMC by density gradient centrifugation using Histopaque-1077 (Sigma-Aldrich). Each time PBMC were isolated, aliquots were suspended in fetal bovine serum (FBS) with 10% DMSO and cryopreserved at −80 °C. All experiments involving horses were approved by the Washington State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Tetramer construction

Identification of the two ELA-A1-restricted EIAV-specific CTL epitopes Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12, as well as cloning and identification of the ELA-A1-associated MHC class I gene 7-6, which encodes the class I molecule that presents Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12, are described elsewhere (McGuire et al., 2003; Mealey et al., 2003). Tetramers were constructed using published methods (Altman et al., 1996). Specifically, the extracellular regions of 7-6 cDNA were PCR amplified using a forward primer located in exon 2, incorporating a HindIII restriction site, a ribosomal binding site, a transcriptional spacer element and a start codon, together with a reverse primer spanning exons 4 and 5, incorporating a BamHI site. The amplified product was cloned into the pGEM-4Z vector (Promega) modified to contain a biotinylation site, a GS linker and a T7 terminator sequence. Horse β2m cDNA (Ellis and Martin, 1993) was similarly amplified and cloned into the pGEM-4Z vector modified to contain a T7 terminator sequence. E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS were transformed with these plasmids, and high-expressing colonies were selected following screening with SDS-PAGE. Suitable clones were grown and induced to over-express protein by addition of IPTG to the growth media. Inclusion bodies were extracted and purified by mechanical disruption of the cells. The 7-6 heavy chain was refolded with horse β2m and each of the two peptides (Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12), was concentrated and biotinylated. Purification of the biotinylated monomer was achieved by FPLC (using size exclusion followed by ion exchange), which resulted in a final yield of 0.5–2 mg. Tetramers were generated as required by adding streptavidin conjugated to phycoerythrin (BD Pharmingen) to each monomer over the course of 15 h to a final molar ratio of 1:4. The resulting tetramers were designated 7-6/Env-RW12 and 7-6/Gag-GW12.

Cytotoxicity assays

Chromium-release assays (McGuire et al., 1994; Mealey et al., 2003) were performed weekly using both freshly isolated and peptide-stimulated PBMC effectors. To prepare peptide-stimulated PBMC, Env-RW12 or Gag-GW12 peptides (final concentration 10 μM) were incubated with freshly isolated PBMC for 2 h at 37 °C with occasional mixing before centrifugation at 250 × g for 10 min. PBMC were then resuspended at 2 × 106/ml in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS, 20 mM HEPES, 10 μg/ml gentamicin, and 10 μM 2-mercaptoethanol. Flat-bottomed 24-well tissue culture plates were seeded with 1 ml/well, and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 7 days at 37 °C. When cryopreserved PBMC were used to assess CTL recognition of epitope variant peptides, stimulations were performed as above except that the Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12 stimulating peptides were used at 40 μM, and 10 U/ml recombinant human IL-2 plus irradiated autologous PBMC stimulators were added. ELA-A1-matched equine kidney (EK) target cells were sensitized by pulsing with the Env-RW12 or Gag-GW12 peptides at 105 nM for 2 h at 37 °C in 96-well plates containing 50 μl/well DMEM with 5% calf serum and 25 μCi 51Cr/ml. To compare CTL recognition of epitope variants, EK targets were pulsed with increasing concentrations of peptides (10−1 to 104 nM). After washing the plates, the PBMC effectors (either freshly isolated or peptide-stimulated) were added at an effector:target cell ratio of 20:1, incubated for 17 h, and 100 μl supernatant removed to determine 51Cr release. The formula percent specific lysis = [(E − S)/(M − S)] × 100 where E = the mean of 3 test wells, S = the mean spontaneous release from 3 target cell wells without effector cells, and M = the mean maximal release from 3 target cell wells with 2% Triton X-100. Values for specific lysis were reported after subtracting the background-specific lysis (obtained using targets not pulsed with peptide). The formula used to calculate standard error of the percent specific lysis accounts for the variability of E, S, and M (McGuire et al., 1994; Siliciano et al., 1985). Specific lysis >10% over background was considered significant.

Flow cytometric analysis of Env- and Gag-specific CD8+ cells

The murine anti-equine CD8 monoclonal antibody HT14A (Kydd et al., 1994) directly conjugated to FITC (HT14A-FITC), and the PE-labeled 7-6/Env-RW12 and 7-6/Gag-GW12 tetramers were used for staining. Freshly isolated or peptide-stimulated PBMC were suspended in wash buffer consisting of phosphate-buffered saline with 2% GG-free horse serum, 10% ACD, 10 mM EDTA, and 0.2% NaN3. Cells (106 PBMC in 50 μl wash buffer) were stained first with 50 μl PE-conjugated 7-6/Env-RW12 or 7-6/Gag-GW12 tetramer at the determined optimal concentration (Fig. 1) for 30 min at 37 °C, washed, then 50 μl (1 μg) HT14A-FITC was added for 15 min at 4 °C. The cells were washed again and two-color analysis was performed on gated lymphocytes using a FACSort flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson), with Cell Quest and Paint-A-Gate Pro software.

Plasma neutralizing antibody activity

Neutralizing antibody activity in frozen heparinized plasma was determined using a virus reduction method (Mealey et al., 2001, 2003). Briefly, 300 μl heparinized plasma was heat inactivated then mixed with 300 μl EIAVWSU5 stock (104 TCID50/ml), and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The same was performed using negative control plasma from four horses not infected with EIAV. The negative controls included pre-inoculation plasma from A2164 and A2171. For each plasma–virus mixture, 3-fold serial dilutions were made, and titration performed in EK cell culture (O’Rourke et al., 1988). Three separate assays were performed for each day assayed, and each assay was done in duplicate. Percent virus reduction was calculated using the formula:

The results obtained from three separate assays were used to report a mean virus reduction for each day assayed.

Viral RNA purification

Viral RNA was isolated from 140 μl frozen EDTA plasma using a QIAamp Viral RNA kit (Qiagen) (Mealey et al., 2003), DNAse I-treated on the spin column (DNAse 1 set, Qiagen), eluted in 60 μl nuclease-free water, and frozen at −20 °C.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR (Mealey et al., 2003) was used with modifications to determine plasma viral load by amplification of a 167-bp segment (nt 1637–1803) of the EIAVWSU5 (GenBank accession no. AF247394) gag gene. Standard RNA template was made by transcribing a cloned 1445-bp gag fragment spanning nucleotides 475–1920 EIAVWSU5 using a Ribomax T7 polymerase transcription kit (Promega). Standard RNA template copy numbers were determined by optical density and dilutions made in nuclease-free water containing 30 μg/ml tRNA and 40 U/ ml Rnasin. Primers 1637F (5′ AGCCAGGACATTTATC-TAGTCAATGTAGAGCA CC 3′) and 1803R (5′ GTGCT-GACTCTTCTGTTGTATCGGGAAAGTTTG 3′), along with a previously reported gag-specific probe (Cook et al., 2002) were used in duplicate 25 μl reactions utilizing an iScript One-Step RT-PCR kit for probes (BioRad), 200 nM of each primer and probe, 40 U Rnasin, and 10 μl plasma RNA template. Reactions were done in an iCyler with the iQ Real-Time PCR Detection System and software (BioRad) under the following conditions: 30 min at 50 °C, 3.5 min at 95 °C, 50 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. Sensitivity was determined using a dilution series of the standard RNA transcripts. The dilution containing 1 RNA copy was positive in 40% (4/10) of the replicates, while the dilutions containing 10 RNA copies or more were positive in 100% (10/10) of the replicates. The reliable detection limit, therefore, was somewhere between 43 and 428 RNA copies/ml when 140 μl plasma for the RNA extraction and 10 μl of the 60 μl eluate were used.

RT-PCR amplification of plasma EIAV genome regions containing CTL epitopes

RT-PCR was performed using a SuperScript One-Step RT-PCR kit (Life Technologies), with 5 μl template RNA eluate in 50 μl total reaction volume as described (Mealey et al., 2003). Briefly, Env-RW12 is contained within EIAVWSU5 nt 5868–6164 and the following primers and reaction conditions were used: forward primer (5616F), 5′-CAACATT-ATATAGGGTTGGTAGC-3′; reverse primer (6164R), 5′-AGCAATCCCTTTCTCCTGT-3′; 30 min at 45 °C, 2 min at 94 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 59 °C, 1 min at 72 °C, and then 7 min at 72 °C. Gag-GW12 is contained within EIAVWSU5 nt 406–694 and the following primers and reaction conditions were used: forward primer (406F), 5′-GACAGCAGAGGAGAACTTAC-3′; reverse primer (694R), 5′-CCTCTCTTTCTTGTCCTG-3′; 30 min at 45 °C, 2 min at 94 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 54 °C, 30 s at 72 °C, and then 7 min at 72 °C.

Cloning and sequencing of RT-PCR products

Amplified products from multiple RT-PCR reactions were purified from agarose gels using a QIAquick Gel Purification Kit (Qiagen Inc.) and cloned into the pCR2.1-TOPO TA cloning vector (Invitrogen) as described (Mealey et al., 2003, 2004). Nucleotide sequences were determined by the Laboratory for Biotechnology and Bioanalysis (Washington State University, Pullman, WA), using an ABI Prism 377 (Applied Biosystems) automated DNA sequencer, and were then submitted to GenBank (accession numbers AY958280 – AY958308, and AY968055 – AY968061). Deduced aa sequences were compared to the EIAVWSU5 consensus sequence using ClustalW and Box-shade programs.

Statistical analysis

To determine correlations between viral load and tetramer-positive CD8+ cell frequency, linear regression (Motulsky, 1995) was performed using GraphPad InStat version 3.06 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Acknowledgments

The important technical assistance of Emma Karel and Lori Fuller is acknowledged. This work was supported in part by U.S. Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health grants AI058787 and AI24291, Morris Animal Foundation grant D01EQ-09, the Washington State University Foundation, and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, UK.

References

- Altman JD, Moss PA, Goulder PJ, Barouch DH, McHeyzer-Williams MG, Bell JI, McMichael AJ, Davis MM. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science. 1996;274:94–96. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey E. Identification and genetics of horse lymphocyte alloantigens. Immunogenetics. 1980;11:499–506. doi: 10.1007/BF01567818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball JM, Rushlow KE, Issel CJ, Montelaro RC. Detailed mapping of the antigenicity of the surface unit glycoprotein of equine infectious anemia virus by using synthetic peptide strategies. J Virol. 1992;66:732–742. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.732-742.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts MR, Krowka JF, Kepler TB, Davidian M, Christopherson C, Kwok S, Louie L, Eron J, Sheppard H, Frelinger JA. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity is inversely correlated with HIV type 1 viral load in HIV type 1-infected long-term survivors. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1999;15:1219–1228. doi: 10.1089/088922299310313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betts MR, Ambrozak DR, Douek DC, Bonhoeffer S, Brenchley JM, Casazza JP, Koup RA, Picker LJ. Analysis of total human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific CD4(+) and CD8(+) T-cell responses: relationship to viral load in untreated HIV infection. J Virol. 2001;75:11983–11991. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.24.11983-11991.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrow P, Lewicki H, Hahn BH, Shaw GM, Oldstone MB. Virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity associated with control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 1994;68:6103–6110. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6103-6110.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breathnach CC, Soboll G, Suresh M, Lunn DP. Equine herpesvirus-1 infection induces IFN-gamma production by equine T lymphocyte subsets. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2005;103:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2004.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buseyne F, Scott-Algara D, Porrot F, Corre B, Bellal N, Burgard M, Rouzioux C, Blanche S, Riviere Y. Frequencies of ex vivo-activated human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific gamma-interferon-producing CD8+ T cells in infected children correlate positively with plasma viral load. J Virol. 2002;76:12414–12422. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12414-12422.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter S, Evans LH, Sevoian M, Chesebro B. Role of the host immune response in selection of equine infectious anemia virus variants. J Virol. 1987;61:3783–3789. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3783-3789.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheevers WP, McGuire TC. Equine infectious anemia virus: immunopathogenesis and persistence. Rev Infect Dis. 1985;7:83–88. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung C, Mealey RH, McGuire TC. CTL from EIAV carrier horses with diverse MHC class I alleles recognize epitope clusters in Gag matrix and capsid proteins. Virology. 2004;327:144–154. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RF, Cook SJ, Li FL, Montelaro RC, Issel CJ. Development of a multiplex real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) J Virol Methods. 2002;105:171–179. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(02)00101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford TB, Wardrop KJ, Tornquist SJ, Reilich E, Meyers KM, McGuire TC. A primary production deficit in the thrombocytopenia of equine infectious anemia. J Virol. 1996;70:7842–7850. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7842-7850.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan MA, Kuroda MJ, Voss G, Schmitz JE, Charini WA, Lord CI, Forman MA, Letvin NL. Use of major histocompatibility complex class I/peptide/beta2M tetramers to quantitate CD8(+) cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for dominant and nondominant viral epitopes in simian–human immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1999;73:5466–5472. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5466-5472.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis SA, Martin AJ. Nucleotide sequence of horse beta 2-microglobulin cDNA. Immunogenetics. 1993;38:383. doi: 10.1007/BF00210486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SA, Cook SJ, Lichtenstein DL, Issel CJ, Montelaro RC. Maturation of the cellular and humoral immune responses to persistent infection in horses by equine infectious anemia virus is a complex and lengthy process. J Virol. 1997;71:3840–3852. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3840-3852.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SA, Issel CJ, Montelaro RC. General method for the detection and in vitro expansion of equine cytolytic T lymphocytes. J Immunol Methods. 1998;213:73–85. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SA, Li F, McKeon BMS, Cook SJ, Issel CJ, Montelaro RC. Immune responses and viral replication in long-term inapparent carrier ponies inoculated with equine infectious anemia virus. J Virol. 2000;74:5968–5981. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.13.5968-5981.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines SA, Stone DM, Hines MT, Alperin DC, Knowles DP, Norton LK, Hamilton MJ, Davis WC, McGuire TC. Clearance of virulent but not avirulent Rhodococcus equi from the lungs of adult horses is associated with intracytoplasmic gamma interferon production by CD4(+) and CD8(+) T lymphocytes. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2003;10:208–215. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.10.2.208-215.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe L, Leroux C, Issel CJ, Montelaro RC. Equine infectious anemia virus envelope evolution in vivo during persistent infection progressively increases resistance to in vitro serum antibody neutralization as a dominant phenotype. J Virol. 2002;76:10588–10597. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.21.10588-10597.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Bauer DE, Tuttleton SE, Lewin S, Gettie A, Blanchard J, Irwin CE, Safrit JT, Mittler J, Weinberger L, Kostrikis LG, Zhang L, Perelson AS, Ho DD. Dramatic rise in plasma viremia after CD8(+) T cell depletion in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J Exp Med. 1999;189:991–998. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.6.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono Y. Viremia and immunological responses in horses infected with equine infectious anemia virus. Natl Inst Anim Health Q Tokyo. 1969;9:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostense S, Ogg GS, Manting EH, Gillespie G, Joling J, Vandenberghe K, Veenhof EZ, van Baarle D, Jurriaans S, Klein MR, Miedema F. High viral burden in the presence of major HIV-specific CD8(+) T cell expansions: evidence for impaired CTL effector function. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:677–686. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200103)31:3<677::aid-immu677>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda MJ, Schmitz JE, Barouch DH, Craiu A, Allen TM, Sette A, Watkins DI, Forman MA, Letvin NL. Analysis of Gag-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus monkeys by cell staining with a tetrameric major histocompatibility complex class I–peptide complex. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1373–1381. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.9.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda MJ, Schmitz JE, Charini WA, Nickerson CE, Lifton MA, Lord CI, Forman MA, Letvin NL. Emergence of CTL coincides with clearance of virus during primary simian immunodeficiency virus infection in rhesus monkeys. J Immunol. 1999;162:5127–5133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kydd J, Antczak DF, Allen WR, Barbis D, Butcher G, Davis W, Duffus WP, Edington N, Grunig G, Holmes MA, et al. Report of the first international workshop on equine leucocyte antigens, Cambridge, UK, July 1991. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1994;42:3–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(94)90088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kydd JH, Wattrang E, Hannant D. Pre-infection frequencies of equine herpesvirus-1 specific, cytotoxic T lymphocytes correlate with protection against abortion following experimental infection of pregnant mares. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2003;96:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leroux C, Issel CJ, Montelaro RC. Novel and dynamic evolution of equine infectious anemia virus genomic quasispecies associated with sequential disease cycles in an experimentally infected pony. J Virol. 1997;71:9627–9639. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9627-9639.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonning SM, Zhang W, Leib SR, McGuire TC. Detection and induction of equine infectious anemia virus-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses by use of recombinant retroviral vectors. J Virol. 1999;73:2762–2769. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2762-2769.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire TC, O’Rourke KI, Perryman LE. Immunopathogenesis of equine infectious anemia lentivirus disease. Dev Biol Stand. 1990;72:31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire TC, Tumas DB, Byrne KM, Hines MT, Leib SR, Brassfield AL, O’Rourke KI, Perryman LE. Major histocompatibility complex-restricted CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes from horses with equine infectious anemia virus recognize Env and Gag/PR proteins. J Virol. 1994;68:1459–1467. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1459-1467.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire TC, Zhang W, Hines MT, Henney PJ, Byrne KM. Frequency of memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes to equine infectious anemia virus proteins in blood from carrier horses. Virology. 1997;238:85–93. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire TC, Leib SR, Lonning SM, Zhang W, Byrne KM, Mealey RH. Equine infectious anaemia virus proteins with epitopes most frequently recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes from infected horses. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:2735–2739. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-11-2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire TC, Leib SR, Mealey RH, Fraser DG, Prieur DJ. Presentation and binding affinity of equine infectious anemia virus CTL envelope and matrix protein epitopes by an expressed equine classical MHC class I molecule. J Immunol. 2003;171:1984–1993. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mealey RH, Fraser DG, Oaks JL, Cantor GH, McGuire TC. Immune reconstitution prevents continuous equine infectious anemia virus replication in an Arabian foal with severe combined immunodeficiency: lessons for control of lentiviruses. Clin Immunol. 2001;101:237–247. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mealey RH, Zhang B, Leib SR, Littke MH, McGuire TC. Epitope specificity is critical for high and moderate avidity cytotoxic T lymphocytes associated with control of viral load and clinical disease in horses with equine infectious anemia virus. Virology. 2003;313:537–552. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00344-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mealey RH, Leib SR, Pownder SL, McGuire TC. Adaptive immunity is the primary force driving selection of equine infectious anemia virus envelope SU variants during acute infection. J Virol. 2004;78:9295–9305. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9295-9305.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel N, Ohlschlager P, Osen W, Freyschmidt EJ, Guthohrlein H, Kaufmann AM, Muller M, Gissmann L. T cell response to human papillomavirus 16 E7 in mice: comparison of Cr release assay, intracellular IFN-gamma production, ELISPOT and tetramer staining. Intervirology. 2002;45:290–299. doi: 10.1159/000067923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montelaro RC, Ball JM, Rushlow KE. Equine retroviruses. In: Levy JA, editor. The Retroviridae. Vol. 2. Plenum Press; New York: 1993. pp. 257–360. [Google Scholar]

- Motulsky H. Intuitive Biostatistics. Oxford University Press; New York: 1995. Simple linear regression; pp. 167–180. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami K, Sentsui H, Shibahara T, Yokoyama T. Reduction of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes during febrile periods in horses experimentally infected with equine infectious anemia virus. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1999;67:131–140. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(98)00225-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman MJ, Issel CJ, Truax RE, Powell MD, Horohov DW, Montelaro RC. Transient suppression of equine immune responses by equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) Virology. 1991;184:55–66. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90821-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor DH, Allen TM, Vogel TU, Jing P, DeSouza IP, Dodds E, Dunphy EJ, Melsaether C, Mothe B, Yamamoto H, Horton H, Wilson N, Hughes AL, Watkins DI. Acute phase cytotoxic T lymphocyte escape is a hallmark of simian immunodeficiency virus infection. Nat Med. 2002;8:493–499. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill T, Kydd JH, Allen GP, Wattrang E, Mumford JA, Hannant D. Determination of equid herpesvirus 1-specific, CD8+, cytotoxic T lymphocyte precursor frequencies in ponies. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1999;70:43–54. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(99)00037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke K, Perryman LE, McGuire TC. Antiviral, anti-glycoprotein and neutralizing antibodies in foals with equine infectious anaemia virus. J Gen Virol. 1988;69:667–674. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-3-667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke KI, Perryman LE, McGuire TC. Cross-neutralizing and subclass characteristics of antibody from horses with equine infectious anemia virus. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1989;23:41–49. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(89)90108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogg GS, McMichael AJ. Quantitation of antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell responses. Immunol Lett. 1999;66:77–80. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(98)00161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogg GS, Jin X, Bonhoeffer S, Dunbar PR, Nowak MA, Monard S, Segal JP, Cao Y, Rowland-Jones SL, Cerundolo V, Hurley A, Markowitz M, Ho DD, Nixon DF, McMichael AJ. Quantitation of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and plasma load of viral RNA. Science. 1998;279:2103–2106. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5359.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantaleo G, Fauci AS. New concepts in the immunopathogenesis of HIV infection. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:487–512. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.002415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen LG, Castelruiz Y, Jacobsen S, Aasted B. Identification of monoclonal antibodies that cross-react with cytokines from different animal species. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2002;88:111–122. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(02)00139-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perryman LE, O’Rourke KI, McGuire TC. Immune responses are required to terminate viremia in equine infectious anemia lentivirus infection. J Virol. 1988;62:3073–3076. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.3073-3076.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinovich O, Payne SL, Montelaro RC, Hussain KA, Issel CJ, Schnorr KL. Rapid emergence of novel antigenic and genetic variants of equine infectious anemia virus during persistent infection. J Virol. 1986;57:71–80. doi: 10.1128/jvi.57.1.71-80.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz JE, Kuroda MJ, Santra S, Sasseville VG, Simon MA, Lifton MA, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Dalesandro M, Scallon BJ, Ghrayeb J, Forman MA, Montefiori DC, Rieber EP, Letvin NL, Reimann KA. Control of viremia in simian immunodeficiency virus infection by CD8+ lymphocytes. Science. 1999;283:857–860. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz JE, Kuroda MJ, Santra S, Simon MA, Lifton MA, Lin W, Khunkhun R, Piatak M, Lifson JD, Grosschupff G, Gelman RS, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Mansfield KA, Letvin NL, Montefiori DC, Reimann KA. Effect of humoral immune responses on controlling viremia during primary infection of rhesus monkeys with simian immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 2003;77:2165–2173. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.3.2165-2173.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellon DC, Fuller FJ, McGuire TC. The immunopathogenesis of equine infectious anemia virus. Virus Res. 1994;32:111–138. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siliciano RF, Keegan AD, Dintzis RZ, Dintzis HM, Shin HS. The interaction of nominal antigen with T cell antigen receptors: I. Specific binding of multivalent nominal antigen to cytolytic T cell clones. J Immunol. 1985;135:906–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Iglesias E, Samri A, Kamkamidze G, Decoville T, Carcelain G, Autran B. A systematic comparison of methods to measure HIV-1 specific CD8 T cells. J Immunol Methods. 2003;272:23–34. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(02)00328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Lonning SM, McGuire TC. Gag protein epitopes recognized by ELA-A-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes from horses with long-term equine infectious anemia virus infection. J Virol. 1998;72:9612–9620. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9612-9620.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]