Abstract

Although CTL are critical for control of lentiviruses, including equine infectious anemia virus, relatively little is known regarding the MHC class I molecules that present important epitopes to equine infectious anemia virus-specific CTL. The equine class I molecule 7-6 is associated with the equine leukocyte Ag (ELA)-A1 haplotype and presents the Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12 CTL epitopes. Some ELA-A1 target cells present both epitopes, whereas others are not recognized by Gag-GW12-specific CTL, suggesting that the ELA-A1 haplotype comprises functionally distinct alleles. The Rev-QW11 CTL epitope is also ELA-A1-restricted, but the molecule that presents Rev-QW11 is unknown. To determine whether functionally distinct class I molecules present ELA-A1-restricted CTL epitopes, we sequenced and expressed MHC class I genes from three ELA-A1 horses. Two horses had the 7-6 allele, which when expressed, presented Env-RW12, Gag-GW12, and Rev-QW11 to CTL. The other horse had a distinct allele, designated 141, encoding a molecule that differed from 7-6 by a single amino acid within the α-2 domain. This substitution did not affect recognition of Env-RW12, but resulted in more efficient recognition of Rev-QW11. Significantly, CTL recognition of Gag-GW12 was abrogated, despite Gag-GW12 binding to 141. Molecular modeling suggested that conformational changes in the 141/Gag-GW12 complex led to a loss of TCR recognition. These results confirmed that the ELA-A1 haplotype is comprised of functionally distinct alleles, and demonstrated for the first time that naturally occurring MHC class I molecules that vary by only a single amino acid can result in significantly different patterns of epitope recognition by lentivirus-specific CTL.

Infections by lentiviruses induce virus-specific CTL responses that are critical for control of viral load and clinical disease. Specifically, Env, Gag, and Rev proteins are important targets for CTL in HIV-1-infected individuals (1-4). Sustained HIV-1 Gag-specific CTL responses are associated with very low numbers of infected CD4+ T cells and stable CD4+ T cell counts in long-term nonprogressors, whereas loss of Gag-specific CTL is associated with clinical progression to AIDS (5). Moreover, HIV-1 Gag-specific CTL responses and frequency are inversely correlated with viral load (6-8), and high frequencies of Gag-specific CTL are significantly associated with slower disease progression (9). In addition, high levels of HIV-1 Env- and Gag-specific memory CTL are strongly associated with low viral load and lack of disease in long-term nonprogressors (10), and CTL responses directed against the early expressed viral regulatory protein Rev inversely correlate with rapid HIV-1 disease progression (11, 12).

Equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV)3 is a macrophage-tropic lentivirus that causes persistent infections in horses worldwide. In contrast to HIV-1 infection however, most EIAV-infected horses eventually control plasma viremia and clinical disease and remain life-long inapparently infected carriers (13-15). The initial as well as the long-term control of viremia and clinical disease is the result of adaptive immune responses, including neutralizing Ab and importantly, CTL (16-22). Due to these robust viral-specific immune responses that contain viral replication, EIAV infection in horses is a unique and useful model system for the study of lentiviral immune control.

As in HIV-1, Env, Gag, and Rev proteins are important CTL targets in EIAV-infected horses. EIAV Env- and Gag-specific CTL are detected during acute and inapparent infection (17, 23, 24), with Gag-specific CTL responses occurring in the majority of horses tested (25, 26). Although EIAV Env-specific CTL can be immunodominant and may be important in early viral control, viral escape can limit the effectiveness of CTL directed against variable Env epitopes, and Gag-specific CTL frequency can correlate with the ability to control viral load and clinical disease (27, 28). Epitope clusters occur within EIAV Gag proteins that are recognized by CTL (including high-avidity CTL) in horses with disparate MHC class I (MHC I) haplotypes and are likely important in control of clinical disease (29, 30). Additionally, moderate and high-avidity Rev-specific CTL are associated with control of viremia and disease in EIAV-infected nonprogressor horses (27). Significantly, no viral escape from high-avidity Rev-specific CTL has been observed. The Rev epitope recognized by these CTL is highly conserved among other strains of EIAV, and independent studies by other investigators show that this sequence does not change during long-term EIAV infection (31, 32).

Given that CTL epitopes in Env, Gag, and Rev are critical for lentiviral immune control, factors that affect the presentation and recognition of these peptides by CTL in a population of infected individuals are important considerations for vaccine development. One of the most important factors is MHC I polymorphism, because CTL recognize peptide epitopes only in the context of allelic forms of MHC I molecules. The CTL TCR binds to a cell surface MHC I complex consisting of the MHC I molecule, a peptide processed from a viral protein, and β2-microglobulin (β2m) (33). The HLA classical MHC I genes are the products of three loci, and as of July 2006, there were 478 HLA-A, 805 HLA-B, and 256 HLA-C named alleles (⟨www.ebi.ac.uk/imgt/hla/intro.html⟩) (34). MHC I polymorphism occurs primarily in the residues that form the peptide-binding domain, therefore influencing the types of peptides that are selectively bound. Similarities in peptide-binding specificity between human MHC I molecules have been identified based on the structure of peptide-binding pockets, peptide-binding assays, and analysis of motifs, and sets of molecules with similar specificities are called supertypes (35-38). Despite the fact that different MHC I molecules can belong to a super-type and have similar peptide-binding specificities, differences in only a few residues among class I molecules can significantly affect the recognition of the MHC I-peptide complex by CTL. Saturation mutagenesis of a murine MHC I molecule has shown that a single amino acid substitution in the α-1 domain can result in more effective killing of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-infected target cells by lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-specific CTL (39). Importantly, the HLA-B*35 subtypes HLA-B*3503 and HLA-B*3502 (B*35-Px genotype) correlate more strongly with rapid progression to AIDS than does the HLA-B*3501 subtype (B*35-PY genotype), which varies from HLA-B*3503 and HLA-B*3502 by only one and two amino acids, respectively, in the peptide-binding domain (40). It is presumed that this effect is due to differential presentation of epitopes to HIV-1-specific CTL, and it has been demonstrated that a higher frequency of Gag-specific CTL correlate with lower viral loads in individuals with the B*35-PY genotype, whereas no significant relationship exists between CTL activity and viral load in the B*35-Px group (41).

Compared with humans, less is known regarding the numbers and locus assignments of equine MHC I alleles. Serology has been the most widely used MHC I typing method in horses, with 17 equine leukocyte Ag (ELA)-A haplotypes defined (42-45). More recently, classical MHC I alleles have been identified and sequenced, but it has not been possible to assign alleles to loci (46-52). Recent work indicates that up to three or four (or more) classical MHC I loci exist, and it is likely that the number of loci is variable and dependent on haplotype (48, 52). Regardless, we have identified the classical equine MHC I molecule 7-6, which is associated with the serologically defined ELA-A1 haplotype (51). The 7-6 molecule presents Env and Gag epitopes (Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12) to distinct populations of EIAV-specific CTL (27, 51). Target cells from some ELA-A1 horses present both epitopes, whereas target cells from other ELA-A1 horses present only Env-RW12 (51), suggesting that subtypes that comprise functionally distinct alleles exist within the ELA-A1 haplotype. In addition, a CTL epitope in EIAV Rev (Rev-QW11) is also restricted by the ELA-A1 haplotype (27), but the molecule that presents Rev-QW11 has not been identified. The purpose of the present study was to determine whether different horses sharing the ELA-A1 haplotype used functionally distinct MHC I molecules to present ELA-A1-restricted CTL epitopes. To test this hypothesis, we sequenced and expressed MHC I genes from three different horses with the ELA-A1 haplotype and determined how these different molecules affected the recognition of important Env, Gag, and Rev epitopes by EIAV-specific CTL.

Materials and Methods

Horses

Arabian horses A2140, A2150, and A2152 were used in this study. A2152 is a noninfected 7-year-old breeding stallion in which the 7-6 MHC I allele was initially identified (51). A2140 and A2150 are 8- and 7-year-old mares, respectively, that have been infected with EIAVWSU5 for 7 and 6 years, respectively (27). The ELA-A haplotypes were determined serologically by lymphocyte microcytotoxicity (42, 53, 54) using reagents provided by Dr. E. Bailey (University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY). All experiments involving horses were approved by the Washington State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Identification of equine MHC I alleles

The full-length 141 gene (GenBank accession no. AY374512) from A2150 was cloned and sequenced as previously described (51). Briefly, PBMC were isolated and cultured for 48 h in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 10 μg/ml gentamicin. Con A (40 μg/ml) was added to up-regulate MHC I expression. mRNA isolated from these cells was used for first-strand synthesis, which was primed with 1 μg of oligo(dT)12-18 and 50 ng of random hexamers. This reaction was incubated at an initial temperature of 37°C for 15 min, followed by an additional hour at 49°C. The second-strand reaction was incubated at 16°C for 2 h using Escherichia coli DNA ligase, polymerase, and RNase H. cDNA was bluntended with T4 DNA polymerase, EcoRI adapters were added with T4 ligase, and the adapters were phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase. The cDNA was then size fractionated, and cDNA between 2 and 3 kb was ligated into EcoRI-digested and dephosphorylated pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen Life Technologies). E. coli electrocompetent cells (Invitrogen Life Technologies) were transformed with this ligation mixture resulting in a cDNA library. Clones were selected from the library by colony-lift hybridization with a 32P-labeled HindIII-XbaI fragment from horse MHC I gene 8/9 (provided by Dr. D. Antczak, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY) (46). Positive colonies were isolated, and those with inserts of the correct size were sequenced. Sequencing was performed at the Laboratory for Biotechnology and Bioanalysis (Washington State University) using dye-labeled dideoxynucleotide-cycle sequencing with an ABI 377 automated sequencer.

The presence of the 7-6 allele (GenBank accession no. AY225155) was confirmed in A2140 using a RT-PCR as previously described (48) with modifications. Briefly, total RNA was isolated from 2 × 107 equine kidney (EK) cells with an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). Ten microliters of RNA and a SuperScript One-Step RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies) was then used with 1 μM each of forward (5′-ATG ATG CCC CCA ACC TTC-3′) and reverse (5′-TGA ACA AAT CTT GCA TCA CTT G-3′) primers. The reaction conditions were 45°C for 50 min, followed by 94°C for 2 min, then 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 53°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. The 1116-bp product was gel isolated and extracted (Qiagen), then used for TOPO TA cloning into the pCR4-TOPO vector for sequencing (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Isolated colony minipreps were digested and electrophoresed to screen for inserts and those with inserts of correct size were sequenced by the Laboratory for Biotechnology and Bioanalysis using dye-labeled dideoxynucleotide-cycle sequencing with an ABI 377 automated sequencer.

Although we independently named the alleles in this study, official Immuno Polymorphism Database nomenclature (⟨www.ebi.ac.uk/ipd/⟩) will soon be available for equine MHC alleles (55).

Expression of equine MHC I alleles

Two retroviral vectors were constructed as described (51) using the plasmid pLXSN (provided by Dr. A. Dusty Miller, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA). The MHC I genes 7-6 and 141 were PCR amplified and ligated into the cloning site of pLXSN downstream of the Moloney murine sarcoma virus long terminal repeat and upstream of the neomycin phosphotransferase gene, which was under the control of the SV40 early promoter (56). The sequences of the inserts and flanking plasmid DNA were determined. To generate vector-producing cell lines, published procedures were used (51, 57). Briefly, an amphotropic packaging cell line, PA317 (CRL-9078; American Type Culture Collection) was transfected with each plasmid. Supernatant from PA317 cells was used to transduce amphotropic PG13 packaging cells (CRL-10686; American Type Culture Collection), which were then selected using 750 μg/ml G-418 sulfate (Invitrogen Life Technologies). Vectors were harvested from the selected PG13 cells and used to transduce CTL target cells. EK cells and human mutant B lymphoblastoid 721.221 cells (58) were transduced with the retroviral vectors expressing 7-6 and 141, pulsed with peptides, and used as CTL targets (51). The 721.221 cells (obtained from Dr. A. Sette, La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology, San Diego, CA) express human β2m, but not HLA-A, -B, or -C class I molecules (58).

PBMC stimulations and CTL assays

PBMC stimulations and CTL assays were performed as described (17, 27, 28, 51) with modifications. Briefly, PBMC were isolated from A2140 and A2150 and stimulated with peptide-pulsed autologous monocytes. EK target cells from A2140 and A2150 and mixed-breed pony H585 were established from kidney tissue obtained by biopsy (17). For stimulation with peptides, 2 μM Env-RW12, Gag-GW12, or Rev-QW11 was added to PBMC in 10% FBS. Peptide and PBMC were incubated for 2 h at 37°C with occasional mixing before centrifugation at 250 × g for 10 min. PBMC were resuspended to 2 × 106/ml in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS, 20 mM HEPES, 10 μg/ml gentamicin, and 10 μM 2-ME. One milliliter was added to each well of a 24-well plate and incubated for 1 wk at 37°C before use in CTL assays. CTL activity was measured using a 51Cr release assay with a 17-h incubation period using EK target cells (17, 27, 28). In addition, human B lymphoblastoid 721.221 target cells transduced with retroviral vectors expressing equine MHC I genes 7-6 or 141 as described above were used in assays with a 5-h incubation period (51). The shorter incubation period was used because 721.221 target cells are less hardy than EK target cells and they develop spontaneous lysis sooner (51). Target cells were pulsed with various amounts of peptide Env-RW12, Gag-GW12, and Rev-QW11 as indicated in the figures. The formula, percent-specific lysis = [(E − S)/(M − S)] × 100, was used, where E is the mean of three test wells, S is the mean spontaneous release from three target cell wells without effector cells, and M is the mean maximal release from three target cell wells with 2% Triton X-100 in distilled water. The E:T ratio was 20:1 or 50:1 as indicated in the figures, and each well contained ~30,000 target cells. The 50:1 E:T ratio was used to confirm 20:1 E:T ratio results. Comparisons were only made between assays that used the same E:T ratio. Previous work indicates that these E:T ratios yield consistent results corresponding to the log portion of the killing curve, and that the 50:1 E:T ratio results in the highest percent-specific lysis (17, 19, 24-30, 51, 57, 59-62). Assays with similar constant E:T ratios have been used by others (63). Only assays with a spontaneous target cell lysis of <30% were used. The SE of percent-specific lysis was calculated using a formula that accounts for the variability of E, S, and M (64). Significant lysis was defined as the percent-specific lysis of peptide-pulsed target cells that was >10% and also >3 SE above the nonpulsed target cells or above target cells transduced with control vectors and pulsed with the relevant peptide. For comparisons of CTL recognition efficiency, the peptide concentration that resulted in 50% maximal target cell-specific lysis (EC50) was used. The EC50 was calculated after transforming the percent-specific lysis data to percent-maximal lysis (with the lowest percent-specific lysis value set to 0% and the highest percent-specific lysis value set to 100%) and fitting the curve with nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism version 3.03 (GraphPad). This is an established method to measure and compare CTL recognition efficiency and avidity (27, 30, 65, 66). All CTL assays were performed at least twice, and the results were consistent in each case.

Live cell peptide-binding assay

Peptide binding to equine MHC I molecules 7-6 and 141 was measured as previously described (51), with slight modifications, using the chloramine-T method (67, 68). Briefly, 721.221 cells transduced with MHC I gene 7-6, 141, or with a retroviral vector that did not express an equine gene, were preincubated with human β2m. The cells were washed and resuspended in RPMI 1640 containing β2m, EDTA, PMSF, and Nα-p-tosyl-l-lysine chloromethyl ketone. One hundred microliters containing 2 × 106 cells plus 1 μl containing 1.5 × 105 cpm of 125I-labeled Env-RW12 was incubated for 4 h at 22°C in wells of a 96-well U-bottom plate. Cells were then washed three times with serum-free medium, centrifuged through calf serum to remove any remaining unbound radiolabeled peptide, and then washed a final time. The radioactivity of the cell pellet was counted with a gamma scintillation counter (Packard Instrument). Competitive inhibition assays were performed twice in triplicate by adding 10 μl containing sufficient unlabeled peptide competitors to result in final concentrations of 1-1000 nM to the initial mixture of cells before addition of radiolabeled Env-RW12 peptide. Competing peptides were unlabeled Env-RW12, Gag-GW12, Rev-QW11, and control peptide 1b4a (VRVED VTNTAEY), which does not inhibit the binding of Env-RW12 to 7-6 (51). For each competing peptide, the concentration resulting in 50% inhibition of radiolabeled Env-RW12 binding (IC50) was calculated by fitting the curve with nonlinear regression using GraphPad Prism version 3.03. All peptides used in binding assays had 95% purity and were synthesized by Sigma-Genosys.

Molecular modeling

Because crystal structures of equine MHC I molecules are not available, three-dimensional computer models of 7-6 and 141 were generated based on known structures of human MHC I molecules using MODELLER 8v2 (⟨www.salilab.org/modeler⟩) (69). Templates for modeling were chosen based on PSI-BLAST searches of the Brookhaven Protein Data Bank database. The 1XR9A structure was used for 7-6 and the 1ZSDA structure (70) was used for 141. The models were verified using VERIFY3D (⟨http://nihserver.mbi.ucla.edu/Verify_3D⟩) (71). Models of the Env-RW12, Gag-GW12, and Rev-QW11 peptides were also generated. To predict the side chain conformations for each peptide, SCWRL3.0 (⟨http://dunbrack.fccc.edu/SCWRL3.php⟩) (72) was used. Viral peptides bound to human MHC I molecules served as templates and were chosen from the Brookhaven Protein Data Bank database (1ZHKC for Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12, and 1ZSDC for Rev-QW11). The 1ZSDC structure is an 11-mer peptide (70), like Rev-QW11. Because no structures of 12-mer peptides bound to MHC I molecules were available, the first residue (L) of 1ZHKC, a 13-mer peptide (73), was eliminated before use as the backbone template for Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12. To model the binding of the three peptides to 7-6 and 141, the docking program FTDock2.0 (⟨www.bmm.icnet.uk/docking⟩) (74-76) was used, and the docking score (RPScore) for each complex was determined (76). The interacting residues for each complex were identified, and the interactions by category (hydrophobic, salt bridges, repulsive charged, hydrogen bonds, and aromatic stacking) between atoms of contact residues were determined using the STING Millennium Suite program (⟨http://trantor.bioc.columbia.edu/SMS/index_m.html⟩) (77, 78). Finally, the models were visualized using the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System (DeLano Scientific, ⟨www.pymol.org⟩).

Results

Target cells from A2140 and A2152 pulsed with Env-RW12, Gag-GW12, and Rev-QW11 were recognized differently by CTL than target cells from A2150

Horses A2140, A2152, and A2150 all had the ELA-A1 haplotype as determined serologically, inheriting ELA-A1 from unrelated dams 172, 162, and 169, respectively (Table I).

Table I. Pedigree of ELA-A1 horses.

| Horse | ELA-A Haplotype |

Dam | Dam ELA-A Haplotypea |

Sire | Sire ELA-A Haplotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A2140 | A1/w11 | 172 | A1 | Sire B | A4/w11 |

| A2152 | A1/A4 | 162 | A1 | Sire B | A4/w11 |

| A2150 | A1/w11 | 169 | A1/A4 | Sire B | A4/w11 |

ELA-A haplotypes were determined serologically by lymphocyte microcytotoxicity. It was not known whether horses with one haplotype were homozygous or heterozygous with a haplotype not recognized by available antisera.

Our previous work indicates that EK target cells from A2140 and A2152 present both the Env-RW12 (RVEDVTNTAEYW) and Gag-GW12 (GSQKLTTGNCNW) epitopes to Env-RW12- and Gag-GW12-specific A2140 CTL (27, 51). Although EK target cells from A2150 present Env-RW12 to Env-RW12-specific A2140 CTL, they do not present Gag-GW12 to Gag-GW12-specific A2140 CTL (51). Because the 7-6 MHC I molecule identified in A2152 presents both Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12 (51), it was likely that a different MHC I molecule presented Env-RW12 but not Gag-GW12 in A2150.

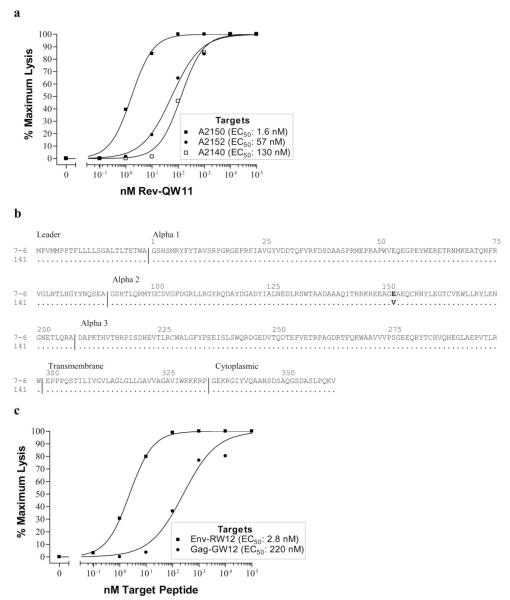

The Rev-QW11 (QAEVLQERLEW) epitope is recognized by CTL from A2150 (27). Although EK target cells from all three horses were capable of presenting Rev-QW11 to Rev-QW11-specific A2150 CTL, these CTL recognized A2150 EK targets more efficiently than A2140 and A2152 targets (Fig. 1a). This observation suggested that the MHC I molecule presenting Rev-QW11 in A2150 was different from the one presenting Rev-QW11 in A2140 and A2152.

FIGURE 1.

Differential CTL recognition efficiencies and sequences of MHC I alleles. a, CTL recognized Rev-QW11-pulsed A2150 EK target cells more efficiently than A2152 and A2140 EK target cells. A2150 CTL were stimulated with Rev-QW11 peptide and percent-specific lysis was determined on A2150, A2152, and A2140 EK targets pulsed with increasing concentrations of Rev-QW11 peptide. E:T cell ratio was 20:1. EC50, Peptide concentration resulting in 50% maximal-specific lysis. Actual minimum and maximum percent-specific lysis for A2150, A2152, and A2140 targets was 7.1 and 49.3, 4.9 and 32.5, and 2.7 and 34.7, respectively. b, Equine MHC I molecules 7-6 and 141 differed in only one amino acid in the α-2 domain. Amino acid sequences of 7-6 and 141 are shown with domains (46, 49) indicated. The E→ V substitution at position 152 is shown in bold. c, CTL recognized Env-RW12 more efficiently than Gag-GW12 when presented by equine MHC I molecule 7-6. A2140 CTL were stimulated with Env-RW12 or Gag-GW12 peptides and percent-specific lysis was determined on 7-6-transduced 721.221 cells pulsed with increasing concentrations of Env-RW12 or Gag-GW12 peptides. E:T cell ratios were 20:1. Actual minimum and maximum percent-specific lysis for Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12 targets was 0 and 43.8, and 2.1 and 21.9, respectively.

Identification of MHC class I alleles in A2140 and A2150

Because the 7-6 molecule that presents Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12 occurs in A2152 (51), and because Env-RW12- and Gag-GW12-specific CTL display similar recognition of A2152 and A2140 EK target cells (51), it was hypothesized that A2140 also possessed the 7-6 allele. Therefore, RT-PCR was used to amplify MHC I genes from A2140 PBMC. Cloning and sequencing confirmed the presence of the 7-6 allele in A2140. Of the 21 isolates processed, 5 were copies of a pseudogene, 3 were other pseudogenes, 6 were copies of a classical gene, and 7 were other classical genes, which included 7-6 (data not shown).

Because previous work indicates that A2150 EK target cells are recognized differently by Env-RW12- and Gag-GW12-specific CTL (51), and because Rev-QW11-specific CTL recognized A2150 EK target cells more efficiently than A2140 and A2152 targets, it was hypothesized that a MHC I molecule distinct from 7-6 presented these epitopes in horse A2150. A previous study identified partial sequences for three MHC I alleles in A2150, one of which, designated 141, shared the 7-6 sequence except for a single amino acid difference encoded at position 152 (E→V) in the α-2 domain (48). Due to its sequence similarity to 7-6, it was of interest to determine whether 141 had similar functional characteristics. To obtain the full-length 141 gene for expression, a cDNA library from A2150 was screened for MHC I genes and 141 was subsequently identified by sequencing (Fig. 1b).

Previous work indicated that the 141 allele is not present in A2152 and that the 7-6 allele is not present in A2150 (48). In addition, allele 141 was not identified among sequenced MHC I clones in A2140 (data not shown). Therefore, the 141 class I molecule was a likely candidate for presenting Env-RW12 and Rev-QW11 but not Gag-GW12 in horse A2150.

CTL recognized Env-RW12 more efficiently than Gag-GW12 when presented by the 7-6 molecule, and also recognized Rev-QW11 presented by 7-6

PBMC from A2140 were stimulated separately with Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12 peptides, then assayed for CTL activity on 7-6-transduced human 721.221 target cells that were pulsed with increasing concentrations of Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12 peptides, respectively. Human mutant B lymphoblastoid 721.221 cells express human β2m, but not HLA-A, -B, or -C class I molecules (58). Env-RW12 was recognized by CTL more efficiently than Gag-GW12, with 50% maximal lysis (EC50) of 2.8 nM for Env-RW12 vs 220 nM for Gag-GW12 (Fig. 1c).

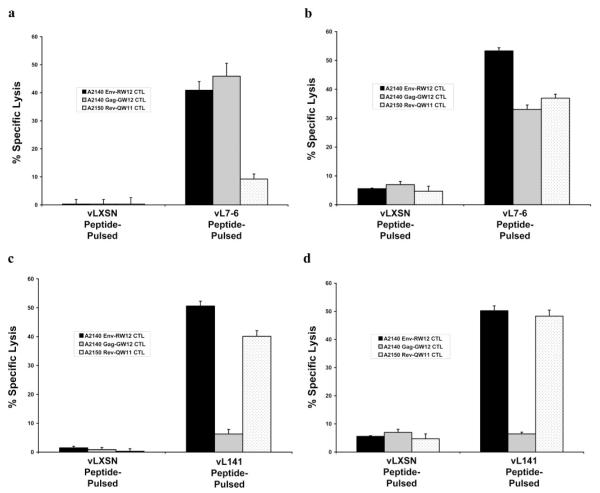

Initial assays indicated that recognition of 7-6-transduced 721.221 cells pulsed with Rev-QW11 by A2150 Rev-QW11-specific CTL was equivocal (Fig. 2a). Because it was possible that the absence of equine β2m on 721.221 cells contributed to poor recognition of Rev-QW11 by CTL, ELA-A mismatched EK cells from pony H585 (ELA-A6) were transduced with 7-6, pulsed with Rev-QW11, and used as targets. Results indicated that in addition to Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12, 7-6 also presented Rev-QW11 (Fig. 2b).

FIGURE 2.

Presentation of CTL epitopes by equine MHC I molecules 7-6 and 141. a and b, MHC I molecule 7-6 presented Env-RW12, Gag-GW12, and Rev-QW11 to CTL. A2140 Env-RW12-, A2140 Gag-GW12-, and A2150 Rev-QW11-stimulated CTL on 7-6-transduced 721.221 cells (a) pulsed with 104 nM of the corresponding peptide and on 7-6-transduced H585 EK cells (b) pulsed with 104 nM of the corresponding peptide. c and d, CTL recognized Env-RW12 and Rev-QW11 when presented by equine MHC I molecule 141, but did not recognize Gag-GW12-pulsed targets expressing 141. A2140 Env-RW12-, A2140 Gag-GW12-, and A2150 Rev-QW11-stimulated CTL on 141-transduced 721.221 cells (c) pulsed with 104 nM of the corresponding peptide and on 141-transduced H585 EK cells (d) pulsed with 104 nM of the corresponding peptide. a-d, vLXSN, empty vector. Error bars are SE for the assay shown, derived as described in Materials and Methods. E:T ratio is 50:1.

The 141 molecule presented Env-RW12 and Rev-QW11 to CTL, but CTL failed to recognize Gag-GW12 on 141-expressing target cells

A retroviral vector containing the 141 gene was constructed and used to transduce 721.221 cells and H585 EK cells. Rev-QW11-specific CTL from A2150 recognized both 141-transduced 721.221 and 141-transduced H585 EK target cells pulsed with the Rev-QW11 peptide (Fig. 2, c and d). Similarly, Env-RW12-specific CTL from A2140 recognized both 141-transduced 721.221 and 141-transduced H585 EK target cells pulsed with Env-RW12 (Fig. 2, c and d). In contrast, Gag-GW12-specific CTL from A2140 failed to recognize both 141-transduced 721.221 and 141-transduced H585 EK target cells pulsed with Gag-GW12 (Fig. 2, c and d).

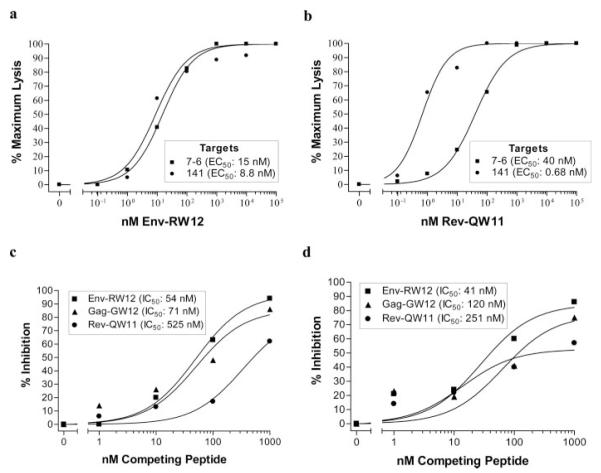

CTL recognized Env-RW12 with similar efficiency when presented by the 7-6 and 141 molecules, whereas CTL recognized Rev-QW11 more efficiently when presented by 141

PBMC from horse A2140 were stimulated with Env-RW12, then assayed for CTL activity on 7-6- and 141-transduced 721.221 target cells that were pulsed with increasing concentrations of Env-RW12. The efficiency of Env-RW12 recognition on 7-6-transduced targets (EC50: 15 nM) was similar to that on 141-transduced targets (EC50: 8.8 nM) (Fig. 3a).

FIGURE 3.

Env-RW12- and Rev-QW11-specific CTL recognition efficiencies and competitive peptide-binding inhibition. a, CTL recognized Env-RW12 with similar efficiency when presented by equine MHC I molecules 7-6 and 141. A2140 CTL were stimulated with Env-RW12 peptide and percent-specific lysis was determined on 7-6- and 141-transduced 721.221 cells pulsed with increasing concentrations of Env-RW12 peptide. E:T cell ratios were 20:1. EC50, peptide concentration resulted in 50% maximal-specific lysis. Actual minimum and maximum percent-specific lysis for 7-6 and 141 targets was 0 and 63.5, and 0 and 49.1, respectively. b, CTL recognized Rev-QW11 more efficiently when presented by equine MHC I molecule 141 than when presented by 7-6. A2150 CTL were stimulated with Rev-QW11 peptide and percent-specific lysis was determined on 7-6- and 141-transduced H585 EK cells pulsed with increasing concentrations of Rev-QW11 peptide. E:T cell ratios were 20:1. Actual minimum and maximum percent-specific lysis for 7-6 and 141 targets was 4.0 and 38.1, and 7.8 and 53.4, respectively. c and d, Unlabeled Env-RW12, Gag-GW12, and Rev-QW11 inhibited 125I-labeled Env-RW12 binding to live 721.221 cells expressing MHC I molecule 7-6 (c), and live 721.221 cells expressing MHC I molecule 141 (d). IC50, peptide concentration resulted in 50% inhibition of radiolabeled Env-RW12 binding.

Because 7-6-transduced 721.221 cells presented Rev-QW11 poorly, MHC I-mismatched H585 EK target cells were used to compare the efficiency of Rev-QW11 recognition when presented by the 7-6 and 141 molecules. Following Rev-QW11 stimulation, A2150 CTL recognized Rev-QW11-pulsed 141-transduced H585 EK targets more efficiently (EC50: 0.68 nM) than Rev-QW11-pulsed 7-6-transduced H585 EK targets (EC50: 40 nM) (Fig. 3b). These results were consistent with those obtained using A2140, A2152, and A2150 EK targets cells (Fig. 1a), and confirmed that in addition to abrogating the recognition of Gag-GW12, the single 152E→V amino acid substitution in class I molecule 141 increased the recognition efficiency of Rev-QW11 by CTL.

Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12 bound to 7-6 and 141 with higher affinity than Rev-QW11

Live-cell Env-RW12 peptide-binding inhibition experiments were performed to determine the relative binding affinities of the three peptides to 7-6 and 141. The Env-RW12 peptide was chosen for 125I labeling because CTL recognized Env-RW12 on 7-6- and 141-expressing targets with similar efficiency (Fig. 3a), suggesting that Env-RW12 bound 7-6 and 141 with similar affinity. Moreover, Env-RW12 was the only peptide with a tyrosine residue, necessary for the chloramine-T method used for 125I labeling (68). The relative binding affinities of each peptide were then determined by using unlabeled peptides in competitive binding inhibition assays. Binding of 125I-labeled Env-RW12 to 7-6 was more efficiently inhibited by unlabeled Env-RW12 (IC50: 54 nM) than by Gag-GW12 (IC50: 71 nM) or Rev-QW11 (IC50: 525 nM) (Fig. 3c). For 7-6 binding, the IC50 of the negative control peptide 1b4a was >1000 nM (percent inhibition caused by 1000 nM was 27%; data not shown). These results were in agreement with the CTL recognition data.

Binding of 125I-labeled Env-RW12 to 141 was efficiently inhibited by unlabeled Env-RW12 (IC50: 41 nM) (Fig. 3d), consistent with the observation for 7-6. Surprisingly, binding of Env-RW12 to 141 was also inhibited by Gag-GW12 (IC50: 120 nM). Thus, the lack of Gag-GW12-specific CTL recognition of 141-expressing target cells was not due to the inability of Gag-GW12 to bind 141. However, the IC50 values indicated that Gag-GW12 bound 141 with lower affinity than 7-6 (120 nM vs 71 nM). Also unexpectedly, Rev-QW11 bound to 141 with lower affinity (IC50: 251 nM) than Gag-GW12. Consistent with the CTL results however, Rev-QW11 bound to 141 with higher affinity than it did to 7-6 (251 nM vs 525 nM). For 141 binding, the IC50 of the negative control peptide 1b4a was >1000 nM (percent inhibition caused by 1000 nM was 33%; data not shown). Taken together, these experiments suggested that differences in MHC/peptide-binding affinity were not sufficient to explain the differential CTL recognition of Gag-GW12 and Rev-QW11 on 7-6- and 141-expressing target cells.

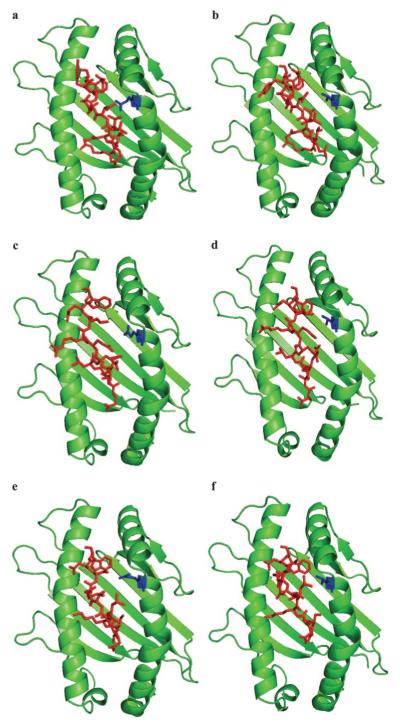

Computer modeling and docking of peptides with the 7-6 and 141 molecules

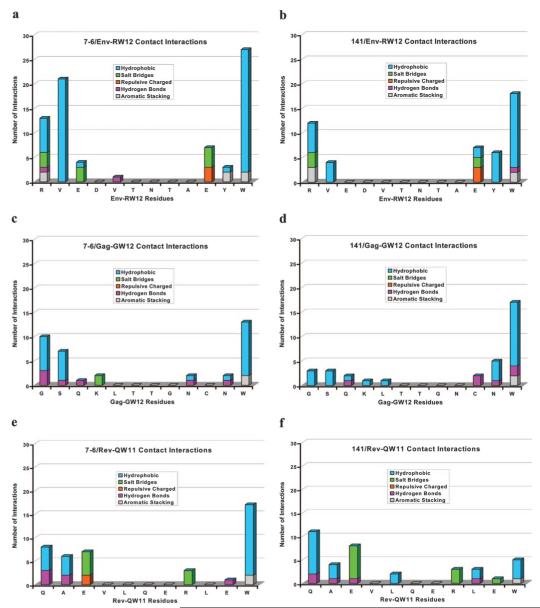

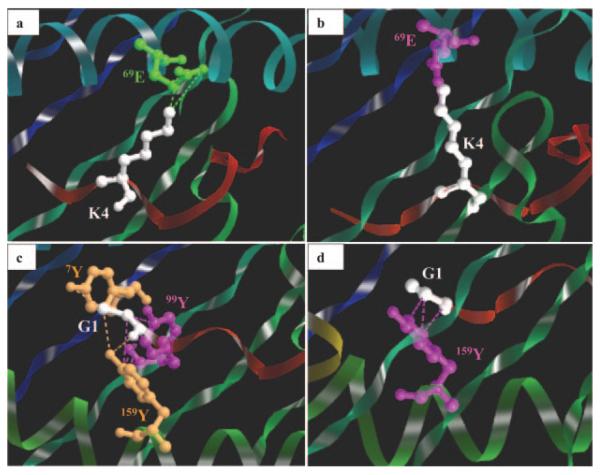

Because crystal structures are not available, three-dimensional molecular modeling was performed to determine the possible structural and functional effects of the 152E→V substitution. Computer models were generated for 7-6 and 141 and the Env-RW12, Gag-GW12, and Rev-QW11 peptides. A docking algorithm was then used to dock each of the three peptides with 7-6 and 141, and docking scores for each complex were calculated. Modeling each of the MHC-peptide complexes indicated that amino acid position 152 occurred in the α-2 helix of 7-6 and 141, within the wall of the peptide-binding cleft, and it appeared that the conformations of the bound peptides were affected differently (Fig. 4). Modeling suggested that the peptides bound 7-6 and 141 in a bulged conformation, with the first and last residues of each peptide anchored in the binding clefts (Fig. 5). The conformation of Env-RW12 was similar when bound to 7-6 and 141 (Fig. 5a), whereas Rev-QW11 was slightly more bulged when bound to 7-6, presumably because of the W11 residue binding less deeply in the peptide-binding cleft of 7-6 (Fig. 5b). Interestingly, the bound conformation of Gag-GW12 was shifted and more sharply bulged in the 141 complex, apparently because the G1 residue of Gag-GW12 bound less deeply in the cleft of 141 as compared with 7-6 (Fig. 5c). Based on an analysis of pair potentials at the interface (76), the docking algorithm predicted the 7-6/Env-RW12 complex as the most favorable (highest RPScore docking score), followed by the 141/Rev-QW11 and 141/Env-RW12 complexes (Table II). The 7-6/Gag-GW12 and 7-6/Rev-QW11 complexes were less favorable and the 141/Gag-GW12 complex was the least favorable, although the docking score differences between these latter three complexes were not profound (Table II). Based on the MHC/peptide-docking models, the 7-6/Env-RW12 complex had a greater number of hydrophobic, salt bridge, hydrogen bond, and aromatic stacking interactions than did the 141/Env-RW12 complex (Table II and Fig. 6). For the 7-6/Rev-QW11 and 141/Rev-QW11 complexes, there were more hydrophobic, hydrogen bond, and aromatic stacking interactions for 7-6/Rev-QW11, but 141/Rev-QW11 had a greater number of salt bridges (Table II and Fig. 6). Importantly, the 7-6/Rev-QW11 complex had two destabilizing repulsive charged interactions that were absent in the 141/Rev-QW11 complex. For the 7-6/Gag-GW12 and 141/Gag-GW12 complexes, the two salt bridges in 7-6/Gag-GW12 were absent in 141/Gag-GW12, and 141/Gag-GW12 had one less hydrogen bond (Table II and Fig. 6). The salt bridges present in 7-6/Gag-GW12 but absent in 141/Gag-GW12 occurred between the 69E residue of 7-6 and the K4 residue of Gag-GW12 (Fig. 6, c and d, and Fig. 7, a and b). In addition, the G1 residue of Gag-GW12 had more interactions with residues of 7-6 (7Y: two hydrophobic, one hydrogen bond; 99Y: two hydrophobic; 159Y: three hydrophobic, two hydrogen bonds) than it did with residues of 141 (159Y: three hydrophobic) (Fig. 6, c and d, and Fig. 7, c and d). Based on the numbers of interactions between contact residues in the docking models for each of the six MHC/ peptide complexes, the first two residues and W12 were probable anchor residues for Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12, whereas the first three residues and W11 were probable anchor residues for Rev-QW11 (Fig. 6). In general, the molecular modeling results supported the experimental data and suggested specific mechanisms for the observed differences in peptide binding and CTL recognition.

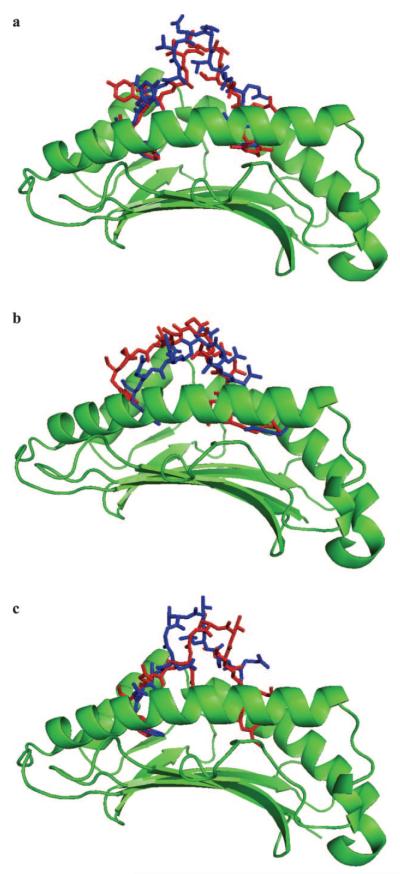

FIGURE 4.

Molecular modeling of the Env-RW12, Rev-QW11, and Gag-GW12 peptides bound to MHC I molecules 7-6 and 141. Top views of Env-RW12 bound to 7-6 (a) and 141 (b), Rev-QW11 bound to 7-6 (c) and 141 (d), and Gag-GW12 bound to 7-6 (e) and 141 (f). The binding clefts of 7-6 and 141 are shown in green, the peptides in red, and the 152E(V) residue in blue. The first residue of the bound peptides is oriented down.

FIGURE 5.

Molecular modeling suggested that the Env-RW12, Rev-QW11, and Gag-GW12 peptides bound to MHC I molecules 7-6 and 141 in bulged conformations, and that Env-RW12 (a) and Rev-QW11 (b) maintained similar conformations when bound to 7-6 and 141, whereas the conformation of Gag-GW12 (c) changed when bound to 141. For each peptide, the conformation when bound to 7-6 is shown in red, and the conformation when bound to 141 is shown in blue. The first residue of the bound peptides is oriented to the right.

Table II. Docking scores and numbers of interactions (by category) among atoms of contact residues for the Env-RW12, Gag-GW12, and Rev-QW11 peptides complexed with the 7-6 and 141 MHC class I molecules.

| 7-6 | 141 | |

|---|---|---|

| Docking scorea | ||

| Env-RW12 | 6.35 | 4.66 |

| Gag-GW12 | 2.96 | 2.25 |

| Rev-QW11 | 2.84 | 4.89 |

| Interaction categoryb | ||

| Hydrophobic | ||

| Env-RW12 | 55 | 33 |

| Gag-GW12 | 26 | 26 |

| Rev-QW11 | 24 | 20 |

| Salt bridges (attractive charged) | ||

| Env-RW12 | 10 | 5 |

| Gag-GW12 | 2 | 0 |

| Rev-QW11 | 8 | 11 |

| Repulsive charged | ||

| Env-RW12 | 3 | 3 |

| Gag-GW12 | 0 | 0 |

| Rev-QW11 | 2 | 0 |

| Hydrogen bonds | ||

| Env-RW12 | 2 | 1 |

| Gag-GW12 | 7 | 6 |

| Rev-QW11 | 6 | 5 |

| Aromatic stacking | ||

| Env-RW12 | 6 | 5 |

| Gag-GW12 | 2 | 2 |

| Rev-QW11 | 2 | 1 |

FIGURE 6.

Numbers of interactions by category between each residue of Env-RW12 and its contact residues in the 7-6 (a) and 141 (b) complex, each residue of Gag-GW12 and its contact residues in the 7-6 (c) and 141 (d) complex, and each residue of Rev-QW11 and its contact residues in the 7-6 (e) and 141 complex (f).

FIGURE 7.

Interactions between contact residues of Gag-GW12 and the 7-6 and 141 MHC I molecules. a, Two salt bridges (bright green dotted lines) between 69E (bright green) of 7-6 and the K4 residue (white) of Gag-GW12 (red ribbon). 69E protrudes from the α-1 helix (turquoise coiled ribbon) of 7-6. The other green and blue ribbons represent the floor of the peptide-binding cleft. b, A single hydrophobic interaction (purple dotted line) between 69E (purple) of 141 and the K4 residue (white) of Gag-GW12 (red ribbon). Other designations are the same as in Fig. 1a. c, Seven hydrophobic interactions (purple dotted lines) and three hydrogen bonds (tan dotted lines) among 7Y (tan), 99Y (purple), and 159Y (tan) of 7-6 and the G1 residue (white) of Gag-GW12 (red ribbon). 7Y and 99Y protrude from the floor of the peptide-binding cleft (blue and green ribbons), and 159Y protrudes from the α-2 helix (green coiled ribbon) of 7-6. d, Three hydrophobic interactions (purple dotted lines) between 159Y (purple) of 141 and the G1 residue (white) of Gag-GW12 (red ribbon). Other designations are the same as in Fig. 1c. Images a-d were generated with the STING Millennium Suite (77, 78), based on the docking models.

Discussion

This study provided the first cloning, sequencing, and expressing of functionally distinct equine MHC I alleles within an ELA-A haplotype as defined by peptide-specific CTL, and demonstrated for the first time that a single residue difference between two naturally occurring MHC I molecules affected the recognition of Gag and Rev epitopes by lentiviral-specific CTL. This was accomplished using standard 51Cr release assays to assess the ability of EIAV Env-, Gag-, and Rev-specific CTL to recognize the corresponding peptides on human 721.221 and heterologous EK target cells transduced with retroviral vectors expressing two distinct MHC I genes derived from three horses with the ELA-A1 haplotype. When compared with the 7-6 molecule, the single 152E→V substitution in the α-2 domain of the 141 molecule enhanced CTL recognition of the Rev-QW11 epitope, but abolished CTL recognition of the Gag-GW12 epitope. Recognition of the Env-RW12 epitope by CTL was not affected.

The hypothesis that the ELA-A1 haplotype was comprised of functionally distinct alleles was based on the initial observations that target cells from ELA-A1 horses A2140 and A2152 were recognized by both Env-RW12- and Gag-GW12-specific CTL whereas target cells from ELA-A1 horse A2150 were not recognized by Gag-GW12-specific CTL, and that Rev-QW11-specific CTL recognized A2150 target cells more efficiently than A2140 and A2152 target cells. Although the latter observation was consistent with the conclusion that the 7-6 MHC I molecule was used by A2140 and A2152 to present these epitopes while the 141 molecule was used by A2150, the efficiency of Rev-QW11-specific CTL recognition of A2140 and A2152 target cells was not exactly the same. The reason for the slightly greater recognition efficiency of the A2152 targets is not known. However, in addition to inheriting ELA-A1 haplotypes from different dams, A2140 and A2150 inherited different ELA haplotypes from the sire. It was therefore possible that the heterogeneous complement of other class I molecules on the respective target cells affected the expression of 7-6, or otherwise decreased peptide binding by 7-6 through competition or other unknown mechanisms (79, 80). Nonetheless, later experiments confirmed the hypothesis.

The loss of Gag-GW12 recognition by CTL was the most striking result of the single amino acid difference between the 7-6 and 141 molecules. Live-cell peptide-binding inhibition assays indicated that Gag-GW12 was able to bind 141, albeit with 1.7 times lower affinity than 7-6. Although this lower binding affinity could have contributed to the inability of Gag-GW12-specific CTL to lyse 141-expressing target cells, loss of TCR recognition of the 141/Gag-GW12 complex was probably more important. Others have shown that a single residue difference between two MHC class I molecules can dictate marked conformational differences in the same bound peptide, directly affecting TCR recognition by CTL (81). Although crystal structures are necessary for confirmation, molecular modeling suggested that the absence of salt bridges, along with the paucity of interactions between the G1 residue (a probable anchor residue) of Gag-GW12 and the 141 molecule, resulted in the observed lower-affinity binding, lower calculated docking score, and a more sharply protruding Gag-GW12 bound confirmation as compared with the 7-6/Gag-GW12 complex. These factors could have lowered TCR affinity for the 141/Gag-GW12 complex such that 141-restricted killing by Gag-GW12-specific CTL no longer occurred.

For the 7-6 molecule, Env-RW12 bound with only 1.3 times higher affinity than Gag-GW12, yet Env-RW12 CTL recognized 7-6 targets with 78 times greater efficiency than Gag-GW12 CTL. Therefore, the difference in affinity for the 7-6 MHC class I molecule between Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12 did not account for the difference in CTL-recognition efficiency, again suggesting that TCR affinity for the MHC/peptide complex played a major role in the discrepancy. Earlier work yielded similar results and conclusions (27, 51). Although the observed difference in 7-6 binding affinity for Env-RW12 and Gag-GW12 was small, molecular modeling provided some possible explanations for the difference. Specifically, the 7-6/Gag-GW12 complex had fewer hydrophobic interactions, fewer salt bridges, and a lower docking score than the 7-6/Env-RW12 complex.

Despite the detrimental effects on Gag-GW12-specific CTL recognition, the 152E →V change in 141 enhanced recognition of Rev-QW11 by CTL. Although CTL recognized Rev-QW11 on 7-6-transduced MHC I-mismatched EK cell targets, 7-6-transduced human 721.221 cells presented Rev-QW11 poorly. This type of differential recognition (equine vs human targets) was not observed for the other peptides, suggesting that human β2m did not effectively stabilize the 7-6/Rev-QW11 complex. This explanation is supported by the observation that human and murine β2m have different murine MHC I-stabilizing effects (82). It is not known why the presentation of the other peptides was not negatively affected by human β2m. Binding inhibition assays indicated that Rev-QW11 bound to 7-6 with 2.1 times lower affinity than to 141, and this inefficient binding could have made the stabilizing effects of autologous β2m more important for the 7-6/Rev-QW11 complex. Based on the molecular modeling results, the 7-6/Rev-QW11 complex had the second lowest docking score overall, and had fewer salt bridges and more destabilizing repulsive-charged interactions than did the 141/Rev-QW11 complex. In addition, and likely because of the reasons just listed, Rev-QW11 bulged out from the 7-6 binding cleft more than it did from 141. This conformational change in bound Rev-QW11 could have negatively affected TCR recognition of the 7-6/Rev-QW11 complex by Rev-QW11-specific CTL. Although crystal structures are needed, modeling provided plausible mechanisms for the inefficient binding of Rev-QW11 to 7-6, and for the inefficient Rev-QW11-specific CTL recognition of 7-6-expressing target cells.

Given the efficient Rev-QW11-specific CTL recognition of 141-expressing target cells and the absence of Gag-GW12-specific CTL recognition of 141-expressing target cells, the observation that Rev-QW11 bound 141 with half the affinity of Gag-GW12 was quite unexpected. Despite the lower MHC binding affinity, the 141-bound conformation of Rev-QW11 must have been efficiently recognized by the TCR of Rev-QW11-specific CTL. In contrast, the TCR of Gag-GW12-specific CTL probably could not bind the sharply protruding and highly bulged conformation of Gag-GW12 in the 141/Gag-GW12 complex.

The CTL epitopes (Env-RW12, Gag-GW12, and Rev-QW11) evaluated in this study were similar in that all three have a large aromatic tryptophan at the C terminus. Additionally, both the N-terminal and C-terminal residues are required for MHC binding and/or CTL recognition for all three epitopes (27, 51). For Env-RW12, the V2 residue is also a probable anchor residue based on 7-6 binding inhibition assays using peptides with amino acid sub-stitutions (51). These observations are consistent with the molecular modeling results obtained in the present study. Analysis of the hydrophilic and hydrophobic amino acid residues for each of the three peptides indicate that Env-RW12 and Rev-QW11 differ from Gag-GW12 at positions 1, 2, 8, and 9. Both Env-RW12 and Rev-QW11 have hydrophilic residues at positions 1 and 8, whereas Gag-GW12 has hydrophobic residues at these positions. At positions 2 and 9, both Env-RW12 and Rev-QW11 have hydrophobic residues, whereas Gag-GW12 has hydrophilic residues at these positions. The differences in these residues, which included probable N-terminal anchor residues, likely contributed to the differences in MHC/peptide complex conformations that allowed CTL TCR recognition of all three peptides when presented by 7-6, but recognition of only Env-RW12 and Rev-QW11 when presented by 141.

Interestingly, all three peptides in this study were longer than the 8-10 aa generally considered optimal for MHC I binding. However, MHC I molecules can bind peptides as long as 14 aa in a bulged conformation and elicit dominant CTL responses (83). Importantly, the BZLF1 protein of EBV includes three completely overlapping CTL epitopes of 9, 11, and 13 aa in length (84). Although all three peptides bind well to the HLA-B*3501 molecule, the CTL response in individuals with this allele is directed exclusively toward the 11-mer epitope (84). Of particular interest, individuals with the B*3503 allele, which differs from B*3501 by a single amino acid in the F pocket of the peptide-binding cleft, do not mount CTL responses to these peptides because they do not bind B*3503. However, individuals with B*3508, which differs from B*3501 by a single amino acid in the D pocket of the peptide-binding cleft, develop CTL responses to the 13-mer epitope (84). The crystal structures indicate that the 13-mer binds both B*3508 and B*3501 in a centrally bulged conformation with the N and C termini anchored in the A and F pockets of the peptide-binding cleft (73). The differential CTL response is due to a broader peptide-binding cleft in B*3508, since the narrower binding cleft of the B*3501-peptide complex interacts poorly with the dominant TCR (73). Crystal structures will be required to confirm that the peptides in the present study bind the 7-6 and 141 molecules in a bulged conformation, and whether or not similar mechanisms are involved in the differential recognition by Env-RW12-, Gag-GW12-, and Rev-QW11-specific CTL.

Although crystal structures of equine MHC I molecules are lacking, the sequences of the two equine class I alleles presented here are surprisingly similar to human and murine class I alleles, and many of the residues forming the binding pockets A–F (in human and murine class I molecules) are shared (85-87). This suggests that the structure of equine MHC I molecules is similar to that of the mouse and human. In the absence of crystallography, molecular modeling provided important insights into the differential recognition of 7-6- and 141-expressing targets by EIAV Gag-GW12- and Rev-QW11-specific CTL. For example, the charged 152E to hydrophobic 152V substitution in the 141 molecule likely affected stabilizing salt bridges for Gag-GW12 binding, as seen when the 13-mer BZLF1 EBV peptide binds to B*3508 and B*3501, which differ only at residue position 156 (charged 156R→hydrophobic 156L) (73). If the modeling is correct, the absence of these stabilizing salt bridges contributed to the conformational change leading to loss of TCR recognition of the 141/Gag-GW12 complex.

This study confirms that a single amino acid difference between naturally occurring MHC I molecules can result in the loss of Gag-specific CTL recognition and enhanced (or diminished) efficiency of Rev-specific CTL recognition. The CTL, peptide-binding, and molecular modeling observations in this study support and suggest molecular mechanisms for the observed differences in disease progression and CTL responses in HIV-1-infected individuals of the B*35-Px and B*35-PY MHC I genotypes, because these genotypes also only differ by as few as one amino acid in the peptide-binding domain (40, 41). The implications of the observed differences in CTL recognition of important EIAV epitopes due to a single amino acid difference between otherwise identical MHC I molecules are important for designing protective lentivirus-specific CTL-inducing vaccines and understanding differential lentivirus disease progression in individuals within a population.

Acknowledgments

The important technical assistance of Emma Karel and Lori Fuller is acknowledged. We also thank Dr. Susan Carpenter for helpful discussions and advice.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

This work was supported in part by U.S. Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health Grants AI058787 (to R.H.M. and T.C.M.), AI067125 (to R.H.M. and T.C.M.), AI060395 (to T.C.M. and R.H.M.), CA97936 (to J.L.), U.S. Department of Agriculture National Research Initiative Grant 2002-35204-12699 (to J.L.), and the Center for Integrated Animal Genomics at Iowa State University (to J.L.).

Abbreviations used in this paper: EIAV, equine infectious anemia virus; MHC I, MHC class I; β2m, β2-microglobulin; ELA, equine leukocyte Ag; EK, equine kidney.

References

- 1.Addo MM, Altfeld M, Rosenberg ES, Eldridge RL, Philips MN, Habeeb K, Khatri A, Brander C, Robbins GK, Mazzara GP, et al. The HIV-1 regulatory proteins tat and rev are frequently targeted by cytotoxic T lymphocytes derived from HIV-1-infected individuals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:1781–1786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betts MR, Krowka JF, Kepler TB, Davidian M, Christopherson C, Kwok S, Louie L, Eron J, Sheppard H, Frelinger JA. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity is inversely correlated with HIV type 1 viral load in HIV type 1-infected long-term survivors. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 1999;15:1219–1228. doi: 10.1089/088922299310313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borrow P, Lewicki H, Hahn BH, Shaw GM, Oldstone MB. Virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity associated with control of viremia in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Virol. 1994;68:6103–6110. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6103-6110.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gea-Banacloche JC, Migueles SA, Martino L, Shupert WL, McNeil AC, Sabbaghian MS, Ehler L, Prussin C, Stevens R, Lambert L, et al. Maintenance of large numbers of virus-specific CD8+ T cells in HIV-infected progressors and long-term nonprogressors. J. Immunol. 2000;165:1082–1092. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein MR, Van Baalen CA, Holwerda AM, Kerkhof Garde SR, Bende RJ, Keet IP, Eeftinck Schattenkerk JK, Osterhaus AD, Schuitemaker H, Miedema F. Kinetics of Gag-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses during the clinical course of HIV-1 infection: a longitudinal analysis of rapid progressors and long-term asymptomatics. J. Exp. Med. 1995;181:1365–1372. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goulder PJ, Altfeld MA, Rosenberg ES, Nguyen T, Tang Y, Eldridge RL, Addo MM, He S, Mukherjee JS, Phillips MN, et al. Substantial differences in specificity of HIV-specific cytotoxic T cells in acute and chronic HIV infection. J. Exp. Med. 2001;193:181–194. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.2.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Novitsky V, Gilbert P, Peter T, McLane MF, Gaolekwe S, Rybak N, Thior I, Ndung’u T, Marlink R, Lee TH, Essex M. Association between virus-specific T-cell responses and plasma viral load in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C infection. J. Virol. 2003;77:882–890. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.882-890.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogg GS, Jin X, Bonhoeffer S, Dunbar PR, Nowak MA, Monard S, Segal JP, Cao Y, Rowland-Jones SL, Cerundolo V, et al. Quantitation of HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes and plasma load of viral RNA. Science. 1998;279:2103–2106. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5359.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogg GS, Kostense S, Klein MR, Jurriaans S, Hamann D, McMichael AJ, Miedema F. Longitudinal phenotypic analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes: correlation with disease progression. J. Virol. 1999;73:9153–9160. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9153-9160.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rinaldo C, Huang XL, Fan ZF, Ding M, Beltz L, Logar A, Panicali D, Mazzara G, Liebmann J, Cottrill M, et al. High levels of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) memory cytotoxic T-lymphocyte activity and low viral load are associated with lack of disease in HIV-1-infected long-term nonprogressors. J. Virol. 1995;69:5838–5842. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5838-5842.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gruters RA, van Baalen CA, Osterhaus AD. The advantage of early recognition of HIV-infected cells by cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. Vaccine. 2002;20:2011–2015. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Baalen CA, Pontesilli O, Huisman RC, Geretti AM, Klein MR, de Wolf F, Miedema F, Gruters RA, Osterhaus AD. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Rev- and Tat-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte frequencies inversely correlate with rapid progression to AIDS. J. Gen. Virol. 1997;78:1913–1918. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-8-1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheevers WP, McGuire TC. Equine infectious anemia virus: immunopathogenesis and persistence. Rev. Infect. Dis. 1985;7:83–88. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGuire TC, O’Rourke KI, Perryman LE. Immunopathogenesis of equine infectious anemia lentivirus disease. Dev. Biol. Stand. 1990;72:31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sellon DC, Fuller FJ, McGuire TC. The immunopathogenesis of equine infectious anemia virus. Virus Res. 1994;32:111–138. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kono Y, Hirasawa K, Fukunaga Y, Taniguchi T. Recrudescence of equine infectious anemia by treatment with immunosuppressive drugs. Natl. Inst. Anim. Health Q. Tokyo. 1976;16:8–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGuire TC, Tumas DB, Byrne KM, Hines MT, Leib SR, Brassfield AL, O’Rourke KI, Perryman LE. Major histocompatibility complex-restricted CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes from horses with equine infectious anemia virus recognize env and gag/PR proteins. J. Virol. 1994;68:1459–1467. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1459-1467.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGuire TC, Fraser DG, Mealey RH. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes and neutralizing antibody in the control of equine infectious anemia virus. Viral Immunol. 2002;15:521–531. doi: 10.1089/088282402320914476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mealey RH, Fraser DG, Oaks JL, Cantor GH, McGuire TC. Immune reconstitution prevents continuous equine infectious anemia virus replication in an Arabian foal with severe combined immunodeficiency: lessons for control of lentiviruses. Clin. Immunol. 2001;101:237–247. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mealey RH, Leib SR, Pownder SL, McGuire TC. Adaptive immunity is the primary force driving selection of equine infectious anemia virus envelope SU variants during acute infection. J. Virol. 2004;78:9295–9305. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9295-9305.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perryman LE, O’Rourke KI, McGuire TC. Immune responses are required to terminate viremia in equine infectious anemia lentivirus infection. J. Virol. 1988;62:3073–3076. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.8.3073-3076.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tumas DB, Hines MT, Perryman LE, Davis WC, McGuire TC. Corticosteroid immunosuppression and monoclonal antibody-mediated CD5+ T lymphocyte depletion in normal and equine infectious anaemia virus-carrier horses. J. Gen. Virol. 1994;75:959–968. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-5-959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammond SA, Cook SJ, Lichtenstein DL, Issel CJ, Montelaro RC. Maturation of the cellular and humoral immune responses to persistent infection in horses by equine infectious anemia virus is a complex and lengthy process. J. Virol. 1997;71:3840–3852. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3840-3852.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGuire TC, Zhang W, Hines MT, Henney PJ, Byrne KM. Frequency of memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes to equine infectious anemia virus proteins in blood from carrier horses. Virology. 1997;238:85–93. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGuire TC, Leib SR, Lonning SM, Zhang W, Byrne KM, Mealey RH. Equine infectious anaemia virus proteins with epitopes most frequently recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes from infected horses. J. Gen. Virol. 2000;81:2735–2739. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-11-2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang W, Lonning SM, McGuire TC. Gag protein epitopes recognized by ELA-A-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes from horses with long-term equine infectious anemia virus infection. J. Virol. 1998;72:9612–9620. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9612-9620.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mealey RH, Zhang B, Leib SR, Littke MH, McGuire TC. Epitope specificity is critical for high and moderate avidity cytotoxic T lymphocytes associated with control of viral load and clinical disease in horses with equine infectious anemia virus. Virology. 2003;313:537–552. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00344-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mealey RH, Sharif A, Ellis SA, Littke MH, Leib SR, McGuire TC. Early detection of dominant env-specific and subdominant gag-specific CD8+ lymphocytes in equine infectious anemia virus-infected horses using major histocompatibility complex class I/peptide tetrameric complexes. Virology. 2005;339:110–126. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chung C, Mealey RH, McGuire TC. CTL from EIAV carrier horses with diverse MHC class I alleles recognize epitope clusters in gag matrix and capsid proteins. Virology. 2004;327:144–154. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung C, Mealey RH, McGuire TC. Evaluation of high functional avidity CTL to gag epitope clusters in EIAV carrier horses. Virology. 2005;342:228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Belshan M, Baccam P, Oaks JL, Sponseller BA, Murphy SC, Cornette J, Carpenter S. Genetic and biological variation in equine infectious anemia virus rev correlates with variable stages of clinical disease in an experimentally infected pony. Virology. 2001;279:185–200. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leroux C, Issel CJ, Montelaro RC. Novel and dynamic evolution of equine infectious anemia virus genomic quasispecies associated with sequential disease cycles in an experimentally infected pony. J. Virol. 1997;71:9627–9639. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9627-9639.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Germain RN, Margulies DH. The biochemistry and cell biology of antigen processing and presentation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1993;11:403–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.002155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson J, Waller MJ, Parham P, de Groot N, Bontrop R, Kennedy LJ, Stoehr P, Marsh SG. IMGT/HLA and IMGT/MHC: sequence databases for the study of the major histocompatibility complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:311–314. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sette A, Sidney J. HLA supertypes and supermotifs: a functional perspective on HLA polymorphism. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1998;10:478–482. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sette A, Sidney J. Nine major HLA class I supertypes account for the vast preponderance of HLA-A and -B polymorphism. Immunogenetics. 1999;50:201–212. doi: 10.1007/s002510050594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sidney J, Grey HM, Kubo RT, Sette A. Practical, biochemical and evolutionary implications of the discovery of HLA class I supermotifs. Immunol. Today. 1996;17:261–266. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80542-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sidney J, Southwood S, Sette A. Classification of A1- and A24-supertype molecules by analysis of their MHC-peptide binding repertoires. Immunogenetics. 2005;57:393–408. doi: 10.1007/s00251-005-0004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Muller D, Pederson K, Murray R, Frelinger JA. A single amino acid substitution in an MHC class I molecule allows heteroclitic recognition by lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J. Immunol. 1991;147:1392–1397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao X, Nelson GW, Karacki P, Martin MP, Phair J, Kaslow R, Goedert JJ, Buchbinder S, Hoots K, Vlahov D, et al. Effect of a single amino acid change in MHC class I molecules on the rate of progression to AIDS. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344:1668–1675. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105313442203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jin X, Gao X, Ramanathan M, Jr., Deschenes GR, Nelson GW, O’Brien SJ, Goedert JJ, Ho DD, O’Brien TR, Carrington M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-specific CD8+-T-cell responses for groups of HIV-1-infected individuals with different HLA-B*35 genotypes. J. Virol. 2002;76:12603–12610. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12603-12610.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bailey E. Identification and genetics of horse lymphocyte alloantigens. Immunogenetics. 1980;11:499–506. doi: 10.1007/BF01567818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bailey E, Marti E, Fraser DG, Antczak DF, Lazary S. Immunogenetics of the horse. In: Bowling AT, Ruvinsky A, editors. The Genetics of the Horse. CABI Publishing; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bernoco D, Antczak DF, Bailey E, Bell K, Bull RW, Byrns G, Guerin G, Lazary S, McClure J, Templeton J, et al. Joint report of the Fourth International Workshop on lymphocyte alloantigens of the horse, Lexington, Kentucky, 12-22 October, 1985. Anim. Genet. 1987;18:81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lazary S, Antczak DF, Bailey E, Bell TK, Bernoco D, Byrns G, McClure JJ. Joint report of the Fifth International Workshop on lymphocyte alloantigens of the horse, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 31 October-1 November 1987. Anim. Genet. 1988;19:447–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.1988.tb00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barbis DP, Maher JK, Stanek J, Klaunberg BA, Antczak DF. Horse cDNA clones encoding two MHC class I genes. Immunogenetics. 1994;40:163. doi: 10.1007/BF00188182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carpenter S, Baker JM, Bacon SJ, Hopman T, Maher J, Ellis SA, Antczak DF. Molecular and functional characterization of genes encoding horse MHC class I antigens. Immunogenetics. 2001;53:802–809. doi: 10.1007/s00251-001-0384-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chung C, Leib SR, Fraser DG, Ellis SA, McGuire TC. Novel classical MHC class I alleles identified in horses by sequencing clones of reverse transcription-PCR products. Eur. J. Immunogenet. 2003;30:387–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2370.2003.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ellis SA, Martin AJ, Holmes EC, Morrison WI. At least four MHC class I genes are transcribed in the horse: phylogenetic analysis suggests an unusual evolutionary history for the MHC in this species. Eur. J. Immunogenet. 1995;22:249–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-313x.1995.tb00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holmes EC, Ellis SA. Evolutionary history of MHC class I genes in the mammalian order Perissodactyla. J. Mol. Evol. 1999;49:316–324. doi: 10.1007/pl00006554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McGuire TC, Leib SR, Mealey RH, Fraser DG, Prieur DJ. Presentation and binding affinity of equine infectious anemia virus CTL envelope and matrix protein epitopes by an expressed equine classical MHC class I molecule. J. Immunol. 2003;171:1984–1993. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tallmadge RL, Lear TL, Antczak DF. Genomic characterization of MHC class I genes of the horse. Immunogenetics. 2005;57:763–774. doi: 10.1007/s00251-005-0034-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bailey E. Population studies on the ELA system in American standardbred and thoroughbred mares. Anim. Blood Groups Biochem. Genet. 1983;14:201–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.1983.tb01073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Terasaki PI, Bernoco D, Park MS, Ozturk G, Iwaki Y. Micro-droplet testing for HLA-A, -B, -C, and -D antigens: The Phillip Levine Award Lecture. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 1978;69:103–120. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/69.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ellis SA, Bontrop RE, Antczak DF, Ballingall K, Davies CJ, Kaufman J, Kennedy LJ, Robinson J, Smith DM, Stear MJ, et al. ISAG/IUISVIC Comparative MHC Nomenclature Committee report, 2005. Immunogenetics. 2006:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00251-005-0071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miller AD, Rosman GJ. Improved retroviral vectors for gene transfer and expression. BioTechniques. 1989;7:980–982. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lonning SM, Zhang W, Leib SR, McGuire TC. Detection and induction of equine infectious anemia virus-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses by use of recombinant retroviral vectors. J. Virol. 1999;73:2762–2769. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2762-2769.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shimizu Y, Geraghty DE, Koller BH, Orr HT, DeMars R. Transfer and expression of three cloned human non-HLA-A,B,C class I major histocompatibility complex genes in mutant lymphoblastoid cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:227–231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ridgely SL, McGuire TC. Lipopeptide stimulation of MHC class I-restricted memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes from equine infectious anemia virus-infected horses. Vaccine. 2002;20:1809–1819. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00517-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ridgely SL, Zhang B, McGuire TC. Response of ELA-A1 horses immunized with lipopeptide containing an equine infectious anemia virus ELA-A1-restricted CTL epitope to virus challenge. Vaccine. 2003;21:491–506. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rivera JA, McGuire TC. Equine infectious anemia virus-infected dendritic cells retain antigen presentation capability. Virology. 2005;335:145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang W, Auyong DB, Oaks JL, McGuire TC. Natural variation of equine infectious anemia virus Gag protein cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitopes. Virology. 1999;261:242–252. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Allen TM, O’Connor DH, Jing P, Dzuris JL, Mothe BR, Vogel TU, Dunphy E, Liebl ME, Emerson C, Wilson N, et al. Tat-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes select for SIV escape variants during resolution of primary viraemia. Nature. 2000;407:386–390. doi: 10.1038/35030124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Siliciano RF, Keegan AD, Dintzis RZ, Dintzis HM, Shin HS. The interaction of nominal antigen with T cell antigen receptors. I. Specific binding of multivalent nominal antigen to cytolytic T cell clones. J. Immunol. 1985;135:906–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alexander-Miller MA, Leggatt GR, Sarin A, Berzofsky JA. Role of antigen, CD8, and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) avidity in high dose antigen induction of apoptosis of effector CTL. J. Exp. Med. 1996;184:485–492. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Derby M, Alexander-Miller M, Tse R, Berzofsky J. High-avidity CTL exploit two complementary mechanisms to provide better protection against viral infection than low-avidity CTL. J. Immunol. 2001;166:1690–1697. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.del Guercio MF, Sidney J, Hermanson G, Perez C, Grey HM, Kubo RT, Sette A. Binding of a peptide antigen to multiple HLA alleles allows definition of an A2-like supertype. J. Immunol. 1995;154:685–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Greenwood FC, Hunter WM, Glover JS. The preparation of I-131-labelled human growth hormone of high specific radioactivity. Biochem. J. 1963;89:114–123. doi: 10.1042/bj0890114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Marti-Renom MA, Stuart AC, Fiser A, Sanchez R, Melo F, Sali A. Comparative protein structure modeling of genes and genomes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2000;29:291–325. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.29.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miles JJ, Elhassen D, Borg NA, Silins SL, Tynan FE, Burrows JM, Purcell AW, Kjer-Nielsen L, Rossjohn J, Burrows SR, McCluskey J. CTL recognition of a bulged viral peptide involves biased TCR selection. J. Immunol. 2005;175:3826–3834. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Luthy R, Bowie JU, Eisenberg D. Assessment of protein models with three-dimensional profiles. Nature. 1992;356:83–85. doi: 10.1038/356083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Canutescu AA, Shelenkov AA, Dunbrack RL., Jr. A graph-theory algorithm for rapid protein side-chain prediction. Protein Sci. 2003;12:2001–2014. doi: 10.1110/ps.03154503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tynan FE, Borg NA, Miles JJ, Beddoe T, El Hassen D, Silins SL, van Zuylen WJ, Purcell AW, Kjer-Nielsen L, McCluskey J, et al. High resolution structures of highly bulged viral epitopes bound to major histocompatibility complex class I: implications for T-cell receptor engagement and T-cell immunodominance. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:23900–23909. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503060200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gabb HA, Jackson RM, Sternberg MJ. Modelling protein docking using shape complementarity, electrostatics and biochemical information. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;272:106–120. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Katchalski-Katzir E, Shariv I, Eisenstein M, Friesem AA, Aflalo C, Vakser IA. Molecular surface recognition: determination of geometric fit between proteins and their ligands by correlation techniques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:2195–2199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Moont G, Gabb HA, Sternberg MJ. Use of pair potentials across protein interfaces in screening predicted docked complexes. Proteins. 1999;35:364–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mancini AL, Higa RH, Oliveira A, Dominiquini F, Kuser PR, Yamagishi ME, Togawa RC, Neshich G. STING Contacts: a web-based application for identification and analysis of amino acid contacts within protein structure and across protein interfaces. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2145–2147. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Neshich G, Togawa RC, Mancini AL, Kuser PR, Yamagishi ME, Pappas G, Jr., Torres WV, Fonseca e Campos T, Ferreira LL, Luna FM, et al. STING Millennium: a web-based suite of programs for comprehensive and simultaneous analysis of protein structure and sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3386–3392. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Day CL, Shea AK, Altfeld MA, Olson DP, Buchbinder SP, Hecht FM, Rosenberg ES, Walker BD, Kalams SA. Relative dominance of epitope-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected persons with shared HLA alleles. J. Virol. 2001;75:6279–6291. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6279-6291.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Moudgil KD, Wang J, Yeung VP, Sercarz EE. Heterogeneity of the T cell response to immunodominant determinants within hen eggwhite lysozyme of individual syngeneic hybrid F1 mice: implications for autoimmunity and infection. J. Immunol. 1998;161:6046–6053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tynan FE, Elhassen D, Purcell AW, Burrows JM, Borg NA, Miles JJ, Williamson NA, Green KJ, Tellam J, Kjer-Nielsen L, McCluskey J, Rossjohn J, Burrows SR. The immunogenicity of a viral cytotoxic T cell epitope is controlled by its MHC-bound conformation. J. Exp. Med. 2005;202:1249–1260. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shields MJ, Assefi N, Hodgson W, Kim EJ, Ribaudo RK. Characterization of the interactions between MHC class I subunits: a systematic approach for the engineering of higher affinity variants of beta 2-microglobulin. J. Immunol. 1998;160:2297–2307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Burrows SR, Rossjohn J, McCluskey J. Have we cut ourselves too short in mapping CTL epitopes? Trends Immunol. 2005;27:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Green KJ, Miles JJ, Tellam J, van Zuylen WJ, Connolly G, Burrows SR. Potent T cell response to a class I-binding 13-mer viral epitope and the influence of HLA micropolymorphism in controlling epitope length. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004;34:2510–2519. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bjorkman PJ, Saper MA, Samraoui B, Bennett WS, Strominger JL, Wiley DC. Structure of the human class I histocompatibility antigen, HLA-A2. Nature. 1987;329:506–512. doi: 10.1038/329506a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fremont DH, Matsumura M, Stura EA, Peterson PA, Wilson IA. Crystal structures of two viral peptides in complex with murine MHC class I H-2Kb. Science. 1992;257:919–927. doi: 10.1126/science.1323877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Matsumura M, Fremont DH, Peterson PA, Wilson IA. Emerging principles for the recognition of peptide antigens by MHC class I molecules. Science. 1992;257:927–934. doi: 10.1126/science.1323878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]