Abstract

Cervical cancer still remains the most common cancer affecting the Indian women. India alone contributes 25.41% and 26.48% of the global burden of cervical cancer cases and mortality, respectively. Ironically, unlike most other cancers, cervical cancer can be prevented through screening by identifying and treating the precancerous lesions, any time during the course of its long natural history, thus preventing the potential progression to cervical carcinoma. Several screening methods, both traditional and newer technologies, are available to screen women for cervical precancers and cancers. No screening test is perfect and hence the choice of screening test will depend on the setting where it is to be used. Similarly, various methods are available for treatment of cervical precancers and the selection will depend on the cost, morbidity, requirement of reliable biopsy specimens, resources available, etc. The recommendations of screening for cervical cancer in the Indian scenario are discussed.

Keywords: Cervix cancer, colposcopy, early detection, precancer, prevention, screening, visual examination

INTRODUCTION

Globally, in the year 2008, there were an estimated 12.7 million new cancer cases and 7.6 million cancer deaths. Cervical cancer is the third most common cancer among women worldwide, with an estimated 529 000 new cases and 275 000 deaths in 2008. More than 85% of the global burden of cervical cancer cases and 88% of cervical cancer deaths occur in developing countries. Cervical cancer is the most common cancer among Indian women and was estimated to have been responsible for 134 420 new cases and 72 825 deaths in the year 2008. India contributes to 25.4% and 26.5% of the global burden of cervical cancer cases and mortality, respectively. The age-standardized incidence rate and age-standardized mortality rate of cervical cancers are 27.0 and 15.2, respectively, among Indian women. Cervical cancer is responsible for 25.9% of all cancer cases and 23.3% of all cancer deaths among Indian women.[1]

This large-scale morbidity and mortality due to cervical cancer is totally unwarranted not only because the definitive cause of cervical cancer is now known, but also because the disease takes a long time to develop after initial infection with high-risk Human papillomavirus (HPV). Unlike most other types of cancer, it is preventable when precursor lesions are detected and treated. Screening can reduce both the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer. The mortality due to uterine cervix cancer has fallen dramatically in the developed countries since the advent and widespread application of cytology-based screening with Pap smear test, developed by George Papanicolaou in the 1950s. In India, to date, there is no organized cervical cancer screening program. Hence, a large proportion of these cancer cases present in advance stages at the time of diagnosis, when cure is not possible. Screening for cervical cancer is essential as the women often do not experience symptoms until the disease has advanced. Women with preinvasive lesions have a five-year survival rate of nearly 100%.[2] Detection of CIN or precancerous lesions such as carcinoma-in-situ leads to a virtual cure with the use of current methods of treatment.[3] In the absence of screening, nearly 70% of cervical cancer patients in India present in stages III and IV.[4] Nearly 20% of women with cervical cancer die within the first year of diagnosis and the 5-year relative survival rate is 50%.[5]

RISK FACTORS AND NATURAL HISTORY OF CERVICAL PRECANCERS AND CANCERS

Persistent infection with high-risk types of HPV is the necessary but not sufficient cause of cervical cancer.[6] Around 70% of cervical cancers are caused by infection with HPV 16 or HPV 18. More than 100 types of HPV have been identified, of which 40 infect the genital tract.[7] Most women are infected with cervical HPV shortly after beginning their first sexual relationship and the majority of these infections are transient.[8] The median time to clearance of HPV infections, detected during screening studies, is 6 to 18 months.[9] Persistent infection with high-risk HPV types may lead to precursor lesions of the cervix, referred to as CIN, which is epithelial cellular change, where the ratio of the cell nucleus to the size of the cell is increased. CIN is graded as CIN1 (mild), CIN2 (moderate), or CIN3 (severe) depending on the proportion of the thickness of the epithelium showing mature, differentiated, and undifferentiated cells. CIN usually occurs in the transformation zone of the cervix near the squamocolumnar junction. Invasive cervical cancer develops from CIN – mild to moderate to severe CIN and then to cancer over a prolonged period of time, usually 7 to 20 years. Most mild CINs spontaneously regress, but some may progress to higher grade CIN. Moderate or severe CIN should be treated as it carries a much higher probability of progressing to invasive cancer, although a proportion of such lesions also regress or persist. If women with CIN3 fail to receive treatment, then about 30% of them will progress to cervical cancer.[10,11] Less than 50% of women who develop HPV infection will show persistence of the same HPV type 12 months later.[12] The incidence of the spontaneous development of cervical cancer is about 1 per 200-300 women with HPV infection.[13]

In addition to infection with high-risk type HPV, certain cofactors[14–18] increase the risk of developing cervical cancers. They are early onset of sexual activity (younger than 18 years), multiple sexual partners, history of one or more sexually transmitted infections, such as Chlamydia infection or genital herpes or HIV, use of tobacco, having a partner whose former partner had cervical cancer, having suppressed immune function from, for example, HIV or the use of chemotherapeutic medications to treat cancer or women with transplanted organs and steroid medications, long-term use (5 or more years) of birth control pills, women whose mothers took diethylstilbestrol (DES) to become pregnant or to sustain pregnancy (this drug was used many years ago to promote pregnancy but it is no longer used for these purposes), dietary deficiencies in vitamin A, folate (vitamin B9), beta-carotene, selenium, vitamin E, and vitamin C (scientific data are not entirely conclusive at this time), family history of cervical cancer, women who do not undergo screening, women who do not follow up with testing or treatment after an abnormal Pap or other screening test, as told by their healthcare provider, and women belonging to low socioeconomic status. It is believed that women from low-income families are at an increased risk due to lack of ready access to adequate healthcare services. Women without the known risk factors rarely develop cervical cancer.

SYMPTOMS

Precancerous changes of the cervix usually do not cause pain or any other symptoms and are not detected unless a woman undergoes screening. Symptoms generally do not appear until abnormal cervical cells become cancerous and invade nearby tissue. The most common symptoms are copious foul-smelling vaginal discharge, abnormal bleeding or inter-menstrual bleeding, postcoital bleeding, postmenopausal bleeding or backache.

DIFFERENT SCREENING/DIAGNOSTIC TESTS TO DETECT CERVICAL PRECANCERS AND CANCERS

Several tests are available to screen women for cervical precancers and cancers.[19] Each screening test has its own strengths and limitations and the choice of test will depend on the setting in which it is to be used.

Cytology-based screening

Cytology-based screening programs continue to be the mainstay of cervical cancer prevention worldwide and have demonstrated reduction in the cervical cancer incidence and mortality, particularly in organized program settings with good-quality screening, adequate coverage, and with optimal frequency. However, cytology-based screening programs can be implemented effectively only if infrastructure and laboratory quality assurance requirements are consistently met. The different types of cytology are as follows:

Pap test with conventional cytology

Conventional cytology is being used for more than 50 years all across the globe. This test involves collection of cells lightly scraped from the ectocervix and endocervix, either with a spatula or brush and preparing their smears. These are then examined under a microscope by specially trained technologists and doctors. This method is widely used for screening cervical cancers in most developed countries. It has overall low sensitivity ranging between 37.8 and 81.3% at atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) threshold with an average of 64.5%, but very high specificity varying from 85.7 to 98.5% with a mean of 92.3%.[20]

The test is highly specific, but false-negative rates have always been an area of concern in cytology-based programs, wherein premalignant or malignant cells have been misdiagnosed as normal. The wide variability in the performance of the test indicates that the test needs to be repeated at frequent intervals to achieve programmatic effectiveness.

Pap test using liquid-based cytology

For liquid-based cytology (LBC), the cells are collected similar to conventional Pap, but using a brush instead of a spatula. The head of the brush is vigorously shaken or broken off into a small pot of liquid containing preservative solution. In the cytology laboratory, the sample is filtered or centrifuged to remove excess blood and debris. The cells are then transferred to the slide in a “mono” layer. It is a more expensive test than conventional cytology and requires additional supplies and sophisticated equipment; however, due to improved transfer of cells from the collection device, uniformity of the cell population in each sample is obtained. The National Health Service (NHS) pilot had repeat smear rates of only 1 to 2% with LBC, compared with 9% when smears are put straight onto the slides.[21] In a meta-analysis comparing conventional Pap with LBC, no difference was found in the relative sensitivity. Similarly, no difference was found in the relative specificity, when high-and low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions were considered as cutoff. However, a lower pooled specificity was found for LBC when presence of ASCUS was the cutoff (ratio, 0.91; 95% confidence interval, 0.84-0.98).[22]

Automated pap smears

Automated Pap testing[23] (AutoPap and AutoCyte Screen) attempts to reduce errors by using computerized analysis to evaluate Pap smear slides. With AutoPap, the material on the slide is reviewed and scored based on an algorithm, as to the likelihood of an abnormality being present. Typically, it does not show the cytotechnologist which of the cells are likely to be abnormal. Variety of visual characteristics, such as shape and optical density of the cells, are included in the algorithm.

In AutoCyte Screen, various cell images are presented to a human reviewer, who then determines whether a manual review is required. The reviewer first needs to enter an opinion, after which the device reveals its determination based on a ranking as to whether manual review is warranted. When the findings of both the reviewer and the computer match and no review is needed, then, a diagnosis of “within normal limits” is given. Manual review is undertaken for cases which are designated by either the cytologist or the computer ranking as abnormal.

Visual examination of cervix

Several methods of visual screening have been investigated in India and various other places. These methods are simple and can be performed by a trained health worker, are relatively inexpensive, do not require laboratory infrastructure, and provide immediate results, allowing the use of “screen and treat” protocols. The various visual examination methods are as follows:

Unaided visual inspection

Visual inspection after application of acetic acid (VIA)

VIA with magnification (VIAM)

Visual inspection after application of Lugol's iodine (VILI)

Unaided visual inspection or visual inspection or downstaging

It is naked eye visualization of the cervix without acetic acid. This technique has been assessed in three studies from India and has been shown to perform poorly.[24–26]

Visual inspection after application of 3 to 5% acetic acid

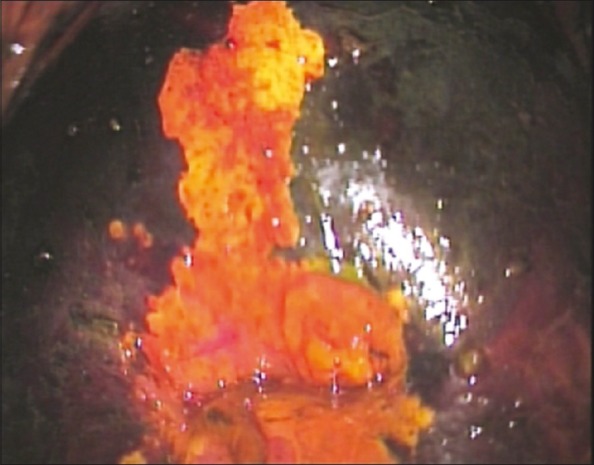

It is naked eye visual inspection of the cervix after application of 3 to 5% acetic acid. When this test is done with the naked eye, it is also called cervicoscopy or direct visual inspection. Application of 3 to 5% acetic acid causes a reversible coagulation or precipitation of the cellular proteins. Areas with dysplasia or invasive cancer have large number of undifferentiated cells in the epithelium and hence undergo maximal coagulation because of higher content of nuclear protein and prevent light from passing through the epithelium, hence these areas appear acetowhite [Figure 1]. The accuracy of VIA to detect cervical neoplasia has been extensively studied and found to be satisfactory.[27–29]

Figure 1.

Visual inspection after the application of acetic acid (VIA) – positive lesion

Visual inspection after application of 3 to 5% acetic acid and under magnification

This is performing VIA under low magnification using magnification devices. It is also called gynoscopy, aided VI, or VIAM. VIAM has similar sensitivity and specificity as compared with VIA and does not have any added benefit over VIA as noted in the Mumbai cervix cancer trial.[30]

Visual inspection after application of Lugol's iodine

It is also known as Schiller's test and uses Lugol's iodine instead of acetic acid. Squamous epithelium contains glycogen, whereas precancerous cells and invasive cancer lack glycogen. Iodine is glycophilic and is taken up by the squamous epithelium, staining it mahogany brown or black. Precancerous lesions and invasive cancer do not take up iodine (because of absence of glycogen) and appear as well-defined, thick, mustard or saffron yellow areas [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Visual inspection after the application of Lugol's iodine (VILI) – positive lesion

Simple tests like VIA and VILI have generated considerable interest in several developing countries including some parts of India. The sensitivity of VIA ranges between 66 and 96% and specificity between 64 and 98%.[31] This is as good as or better than conventional cytology. The sensitivity and specificity of VILI was 87.2% and 84.7%, respectively, as noted in a cross-sectional study involving 4 444 women.[32] Goldie et al. have shown that screening women once in a lifetime at the age of 35 years with a one or two visit screening strategy involving VIA would reduce the lifetime risk of cervical cancer by approximately 25 to 36% and cost less than 500 US dollars per year of life saved.[33]

Colposcopy

A colposcope is a low-power, stereoscopic, binocular field microscope containing a powerful light source, used for magnified visual examination of the uterine cervix to help in the diagnosis of cervical neoplasia [Figure 3]. The most common indication of referral for colposcopy is positive screening tests (e.g., positive cytology, positive on VIA, etc.).[34] This examination is not painful, has no side effects, and it can be performed safely throughout pregnancy. Unlike a Pap test, which scrapes tissue from the entire cervix, colposcopy allows the examiner to take tissue samples (biopsies) from specific areas that do not look normal. The cervix biopsy is obtained deep enough to get adequate stroma, in order to exclude invasion. Endocervical curettage is usually obtained when the colposcopy is unsatisfactory, i.e., the squamocolumnar junction cannot be visualized. A curette is used to scrape the endocervical canal and get the tissue lining.

Figure 3.

Colposcopy

Cervicography

Cervicography[35] consists of distant evaluation of photographs of the cervix “cervicograms,” taken with a specialized 35-mm camera, after application of acetic acid. Cervicography does not require experience in colposcopy and the photographs taken resemble a low-magnification colposcopic photograph. Certified evaluators who have received specialized training in interpretation of cervicograms interpret these images at a central laboratory, classifying them as negative, atypical, or positive. In a clinical review of cervicography, cervicogram appeared superior to cytology but inferior to colposcopy in the detection of cervical pathology. However, the study concluded that cervicography cannot be recommended for universal screening, though it may have a role in the follow-up of patients with a mildly abnormal cervical smear.

Human papillomavirus DNA test

The etiopathological role of HPV as a causative agent of cervical cancer has been well established. However, most HPV infections in young women regress rapidly, without causing clinically significant disease. Although there are variety of laboratory-based approaches for detecting HPV in cervical samples, the Hybrid Capture II kit (HC II, Qiagen Inc., USA) approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) is frequently used. The sample is collected similar to Pap, with a cervical swab from the transformation zone and placed into transport medium. The test may also be performed from residual material collected in liquid-based medium for monolayer preparation. This test detects whether a person is infected with one or more of the 13 high-risk HPV viral types (types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68). It is used as a routine screening test for women above 30 to 35 years in many regions and is especially useful to evaluate women with equivocal Pap test. The sensitivity of HPV testing for detecting CIN 2–3 lesions varied from 45.7 to 80.9% across different study sites in India; the specificity varied from 91.7 to 94.6%.[36] A cluster randomized controlled trial in rural India recently reported that HPV testing (Qiagen HC II) was the most objective and reproducible of all cervical screening tests and was less demanding in terms of training and quality assurance.[37] However, HPV testing requires sophisticated laboratories and is currently unaffordable ($20 to $30 per test) in less-developed countries.

careHPV test (Qiagen Inc. USA) is being tested that would detect several types of HPV rapidly, within three hours, without the requirement of specially trained personnel or sophisticated laboratory. Because of its simplicity and rapid completion, it would potentially allow screening and clinical follow-up to be completed on the same day.

MANAGEMENT OF CERVICAL PRECANCERS

Appropriate clinical management of screen-positive cases is pertinent to the success of cervical cancer screening program. Precancers are completely curable with appropriate treatment and regular follow-up. However, the survival is grossly affected for invasive cervical cancers.[34,38] There is consensus agreement that cytology indicative of high-grade lesions (CIN2-3 or HSIL in the Bethesda system) should engender immediate referral for colposcopy and biopsy.[39–41] The management of women who have equivocal or borderline cytology of low-grade abnormalities (ASCUS/LSIL) is still under debate. It is generally agreed to have a HPV triage for women with equivocal cytology. Cervical precancers can be treated in different ways depending on the extent and nature of the disease. The different modalities of managing precancers of the cervix are as follows:

Regular screening and follow-up

Low-grade cervical dysplasia (LSIL, CIN1) often spontaneously resolve without treatment, but careful monitoring and follow-up testing is required. Very early dysplasias are most likely to regress. Hence, the patient may be kept under observation and regular follow-up as very few of them may progress to high-grade dysplasias. Persistent CIN1 at 2 years warrants treatment.

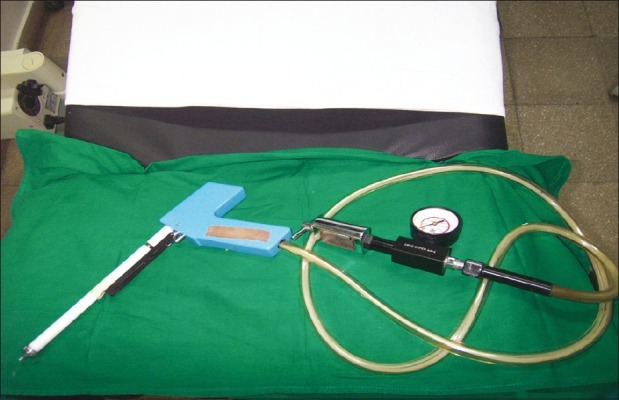

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy is a relatively simple and safe procedure that destroys the precancerous cells using compressed refrigerant gas like nitrous oxide or carbon dioxide to freeze the ectocervical tissue. No anesthesia is required. The procedure uses a cryoprobe using tip made of highly conductive metal like silver or copper which makes direct surface contact with the ectocervical lesion [Figure 4]. The refrigerant gas is then made to flow, leading to destruction of abnormal cervical tissue because of extreme cold temperatures. Cryonecrosis is achieved by crystallization of intracellular water. The disadvantage of cryotherapy is that no tissue sample is available to confirm the histology and extent of involvement of the lesion. Cryotherapy is not appropriate for treating large lesions that cannot be covered by the probe or lesions located in the endocervical canal.[34] The success of treatment of CIN3 in non-controlled studies varied between 77 and 93%.[38]

Figure 4.

Cryotherapy

Loop electrosurgical excision procedure

The loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) instrument is powered by an electrosurgical unit and consists of a wire loop electrode on the end of an insulated handle, which acts as a scalpel to excise the visible patches of abnormal cervical tissue. It is also known as large loop excision of the transformation zone. The current is adjusted to achieve cutting and coagulation effect simultaneously. The power used needs to be sufficient to excise the tissue without causing thermal artifact. The procedure can be performed under local analgesia and results in good cure rates. The cervical transformation zone and lesion are excised to an adequate depth, which in most cases is at least 8 mm, and extending 4 to 5 mm beyond the lesion. It can be performed as a single pass procedure or multiple pass procedure in the same sitting. There may be mild cramping during and after the procedure, and mild bleeding that may persist for some days. LEEP is most commonly used to treat high-grade cervical dysplasias. The major advantage of LEEP over cryotherapy is that it removes the affected epithelium rather than destroying it, thus allowing histological examination of the excised tissue.[34] Treatment success of LEEP varied between 91 and 98% in nonrandomized studies.[38]

Cervical conization

This procedure which can be used for diagnostic or therapeutic purpose involves removal of a cone-shaped piece of tissue from the cervix. The base of the cone is formed by the ectocervix (outer part of the cervix), and the endocervical canal forms the apex of the cone. Conization is performed under general anesthesia and can completely remove many precancers and very early cancers. After the procedure, cramping and some bleeding may persist for a few weeks. Rare complication is cervical stenosis. The treatment success of knife cone biopsy is reported as 90 to 94% in nonrandomized studies.[38]

The cold knife cone biopsy uses a surgical scalpel or a laser as a scalpel, rather than a heated wire to remove tissue. The procedure can be performed under local or general anesthesia and the success rate is reported between 93 and 96%.[38]

Laser ablation

A laser beam is used to destroy abnormal cervical tissue at the transformation zone, the destruction of tissue being controlled by the length of exposure. It is usually performed under local anesthesia. Treatment success of laser ablation is reported as 95 to 96%.[38]

The Cochrane database which included 29 trials and seven surgical techniques to assess the effectiveness and safety of alternative surgical treatments for CIN concluded that there is no obvious superior surgical technique for treating CIN in terms of treatment failures or operative morbidity. Cryotherapy appeared to be an effective treatment for low-grade disease but not for high-grade disease. Knife cone biopsy is important if invasion or glandular disease is suspected.[38]

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CERVICAL CANCER PREVENTION

Cervical cancer does not develop suddenly. It is the normal cells of cervix that develop precancerous changes that then turn to cervical cancer. Hence, there are two ways of reducing the burden of cervical cancers. One is to detect and treat cervical precancers before they become true cancers, and the second is to prevent the development of precancers itself.

Regular screening and timely follow-up is necessary

Despite the fact that early detection and treatment is one of the priorities of the National Cancer Control Programme in India, yet there is no organized cervical cancer screening program in the country; hence, screening mainly remains opportunistic. National consultations on cervical cancer control have concluded that cytology screening is not feasible in view of the technical and financial constraints in India. Visual examination and HPV testing have been evaluated as alternatives to cytology in India. However, with the high cost of HPV testing, VIA seems to be a feasible alternative for triaging, followed by appropriate interventions (depending on the level of expertise available at referral centers) in reducing the incidence and mortality of cervical cancer.[18]

According to American Cancer Society (ACS) guidelines, cervical cancer screening should ideally begin three years after the initiation of sexual intercourse. The women may be screened annually for the first three years, after which if three consecutive screening test results are normal, then once in two to three years screening suffices. The same recommendations apply for women with subtotal hysterectomy. Women above 70 years with an intact cervix who have had three or more documented, consecutive, technically satisfactory normal cervical cytology tests and no abnormal or positive cytology tests within the 10-year period prior to age 70 years may elect to cease cervical cancer screening. Women who are immunocompromised (including HIV-positive women) should undergo screening twice in the first year after diagnosis of HIV infection and if the results are normal, then continue with annual screening.

Women with total hysterectomy should be screened only if there is history of cervical precancer or cancer or when it is not possible to document the absence of cervical precancer or cancer as the indication for the hysterectomy. Women with a history of cervical precancer should be screened until there is a 10-year history of no abnormal/positive cytology tests, including documentation of three consecutive, technically satisfactory, normal or negative cervical cytology tests. Women with a history of in utero DES exposure and/or a history of cervical carcinoma should continue screening after hysterectomy, as also immunocompromised women with intact uterus, for as long as they are in reasonably good health and do not have a life-limiting chronic condition.[42]

Other recommendations for prevention of cervical precancers and cancers are to avoid use of tobacco, practice safe sex, limit the number of sex partners, and choose a sex partner who has no other sex partners. Use of condoms consistently and correctly during sexual activity may offer some degree of protection. Condoms do not provide complete protection from HPV infection because this virus (unlike HIV) can spread by contact with any infected area of the body. Having a healthy diet and lifestyle and consuming diet rich in beta-carotene, vitamin C, and folate (vitamin B9) from fruits and vegetables is recommended. HPV vaccines are currently expensive and not covered under the National Immunization Program. However, vaccination with HPV, especially for women before sexual debut, is recommended whenever possible.

Human papillomavirus vaccine

Vaccines against HPV infections[13] hold promise to reduce incidence of cervical cancer. Currently, two vaccines, Cervarix manufactured by GSK and Gardasil manufactured by Merck, are available to protect women against HPV types 16 and 18, the oncogenic types responsible for about 70% of cervical cancers. One of these vaccines, Gardasil, also protects against HPV types 6 and 11 which causes genital warts. Both vaccines consist of virus-like particles and are recommended for women, preferably before the onset of sexual activity. The vaccines are to be administered 0.5 ml intramuscularly in three doses over a period of six months (the schedule is 0, 2, and 6 months for Gardasil and 0, 1, and 6 months for Cervarix). The HPV vaccine is safe and effective, with no serious side effects. Boys and young men may choose to get this vaccine to prevent genital warts. The impact of the vaccine will be known after decades when the girls who have received the vaccine reach an age when they might otherwise be at potential risk for developing cervical cancer. Also, the current vaccines cover only two high-risk types of HPV. Hence, vaccines cannot substitute screening and treatment of cervical precancers. There are several challenges for the vaccine to be successfully used to control this largely preventable disease, including endorsement by governments and policy makers, affordable prices, education at all levels, overcoming barriers to vaccination, etc. Currently ongoing research is focused on the development of HPV vaccines that will offer protection against a broader range of HPV types and in the development of therapeutic vaccines, which seek to elicit immune responses against established HPV infections and HPV-induced cancers.

CONCLUSIONS

Cervical cancer continues to be the single largest cancer among women in India and several other countries which cannot afford the logistics of cytology-based screening programs. The goal of cervical screening is to identify and remove significant precancerous lesions in addition to preventing mortality from invasive cancer. Population-based screening with cytological examination requires vast resources and highly skilled technical manpower. Such resources and skilled manpower are not available in India. Hence, we need to design cervical cancer screening programs using alternative strategies, like visual-based techniques, that are low cost but effective and compatible with the prevailing socioeconomic realities. Vaccines against HPV infections are now available, but are very expensive. The currently available vaccines do not protect against all cancer-causing types of HPV, so routine screening is still necessary.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saslow D, Runowicz CD, Solomon D, Moscicki AB, Smith RA, Eyre HJ, et al. American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of cervical neoplasia and cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52(6):342–62. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.6.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffman MS, Cavanagh D. Gynecologic Oncology Program. H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute. [Last accessed on 2011 Feb 10]. Available from: http://www.moffitt.org/moffittapps/ccj/v2n6/article3.html .

- 4.Dinshaw KA, Rao DN, Ganesh B. Tata Memorial Hospital Cancer Registry Annual Report. Mumbai, India: 1999. p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeole BB, Jussawalla DJ, Sabnis SD, Sunny L. Survival from breast and cervical cancers in Mumbai (Bombay), India. In: Sankaranarayanan R, Black RJ, Parkin DM, editors. Cancer survival in developing countries. IARC, Scientific Publication No. 145. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research in Cancer; 1998. pp. 79–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodman CB, Collins SI, Young LS. The Natural History of Cervical HPV Infection: Unresolved Issues. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(1):11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Villiers EM, Fauquet C, Broker TR, Bernard HU, zur Hausen H. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virology. 2004;324:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins S, Mazloomzadeh S, Winter H, Blomfield P, Bailey A, Young LS, et al. High incidence of cervical human papillomavirus infection in women during their first sexual relationship. BJOG. 2002;109:96–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singer A, Khan AM. The Benefit of Human Papillomavirus testing in Predicting Cervical Cancer. Euro Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;4(1):58–61. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cervcial Cancer Prevention Fact Sheet. Seattle: ACCP; 2003. Alliance for Cervical Cancer Prevention (ACCP), “Natural History of Cervical Cancer: Even Infrequent Screening of Older Women Saves Lives,”. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holowaty P, Miller AB, Rohan T, To T. Natural history of dysplasia of the uterine cervix. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:252–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trottier H, Franco EL. The epidemiology of genital human papillomavirus infection. Vaccine. 2006;24(supplement 1):S1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawana K, Yasugi T, Taketani Y. Human papillomavirus vaccines: Current issues and future. Indian J Med Res. 2009;130:341–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Almonte M, Albero G, Molano M, Carcamo C, García PJ, Pérez G. Risk factors for human papillomavirus exposure and co-factors for cervical cancer in Latin America and the Caribbean. Vaccine. 2008;26(11):L16–36. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berrington De GA, Sweetland S, Green J. Comparison of risk factors for squamous cell and adenocarcinomas of the cervix: A meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(9):1787–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shanta V, Krishnamurthi S, Gajalakshmi CK, Swaminathan R, Ravichandran K. Epidemiology of cancer of the cervix: Global and national perspective. J Indian Med Assoc. 2000;98:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juneja A, Sehgal A, Mitra AB, Pandey A. A survey on risk factors associated with cervical cancer. Indian J Cancer. 2003;40:15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guidelines for Management of Cervix Cancer. Indian Council of Medical Research ICMR New Delhi. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 19.In: Alliance for cervical cancer prevention (ACCP). Planning and implementing cervical cancer prevention and control programs: A Manual for Managers. Seattle: ACCP; 2004. Rationale for cervical cancer prevention; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sankaranarayanan R, Thara S, Sharma A, Roy C, Shastri S, Mahé C, et al. Accuracy of conventional cytology: Results from a multicentre screening study in India. J Med Screen. 2004;11:77–84. doi: 10.1258/096914104774061056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fielder H. Cervical Screening Wales. Liquid Based Cytology – Pilot Project. Project Report. 2003. Nov, [Last accessed on 2011 June 10]. Available from: http://www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/cervical/lbc.html .

- 22.Arbyn M, Bergeron C, Klinkhamer P, Martin-Hirsch P, Siebers AG, Bulten J. Liquid compared with conventional cervical cytology: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:167–77. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000296488.85807.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nuovo J, Melnikow J, Howell LP. New tests for cervical cancer screening. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(5):780–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sehgal A, Singh V, Bhambhani S, Luthra UK. Screening for cervical cancer by direct inspection. Lancet. 1991;338:282. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90420-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nene B, Deshpande S, Jayant K, Budukh AM, Dale P, Deshpande D, et al. Early detection of cervical cancer by visual inspection: A population-based study in rural India. Int J Cancer. 1996;68:770–3. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961211)68:6<770::AID-IJC14>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wesley R, Sankaranarayanan R, Mathew B, Chandralekha B, Beegum A Aysha, Amma NS, et al. Evaluation of visual inspection as a screening test for cervical cancer. Br J Cancer. 1997;75:436–40. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Visual inspection with acetic acid for cervical cancer screening: Test qualities in a primary-care setting. Lancet. 1999;353:869–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sankaranarayanan R, Basu P, Wesley R, Mahe C, Keita N, Mbalwa CC Gombe, et al. Accuracy of visual screening for cervical neoplasia: Results from an IARC multicentre study in India and Africa. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:341–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belinson JL, Pretorius RG, Zhang WH, Wu LY, Qiao YL, Elson P. Cervical cancer screening by simple visual inspection after acetic acid. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:441–4. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shastri SS, Dinshaw KA, Amin G, Goswami S, Patil S, Chinoy R, et al. Concurrent evaluation of visual, cytological and HPV testing as screening methods for the early detection of cervical neoplasia in Mumbai, India. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:186–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.In: Planning appropriate cervical cancer prevention programmess. 2nd ed. Seattle WA USA: PATH; 2000. Screening: Visual Approaches; pp. 15–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sankaranarayanan R, Wesley R, Thara S, Dhakad N, Chandralekha B, Sebastian P, et al. Test characteristics of visual inspection with 4% acetic acid (VIA) and Lugol's iodine (VILI) in cervical cancer screening in Kerala, India. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:404–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldie SJ, Gaffikin L, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Gordillo-Tobar A, Levin C, Mahé C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of cervical-cancer screening in five developing countries. Alliance for Cervical Cancer Prevention Cost Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2158–68. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa044278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sellors JW, Sankaranarayanan R, editors. Colposcopy and treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: A beginner's manual. IARC; 2003-04. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turner MJ, Byrne BM, Flannelly G, Maguire P, Lenehan PM, Murphy JF. A clinical review of cervicography. Ir J Med Sci. 1990;159:50. doi: 10.1007/BF02937249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sankaranarayanan R, Chatterji R, Shastri SS, Wesley RS, Basu P, Mahe C, et al. Accuracy of human papillomavirus testing in primary screening of cervical neoplasia: Results from a multicenter study in India. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:341–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sankaranarayanan R, Nene BM, Shastri SS, Jayant K, Muwonge R, Budukh AM, et al. HPV screening for cervical cancer in rural India. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1385–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin-Hirsch PP, Paraskevaidis E, Bryant A, Dickinson HO, Keep SL. Surgery for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;16(6):CD001318. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001318.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wright TC, Jr, Cox JT, Massad LS, Carlson J, Twiggs LB, Wilkinson EJ. 2001 consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:295–304. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.NHS. Colposcopy and programme management: Guidelines for the NHS cervical screening programme. NHSCSP. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Management of abnormal cervical cytology and histology. Clinical management guidelines for the Obstetrician and Gynecologist. ACOG Practice Bulletin. 2008;99(112):1419–44. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318192497c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brooks D, Saslow D, Shah M, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2011: A Review of Current American Cancer Society Guidelines and Issues in Cancer Screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:8–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]