Abstract

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is defined as a resting mean pulmonary artery pressure greater than 25 mmHg. The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies PH into five categories. The WHO nomenclature assumes shared histology and pathophysiology within categories and implies category-specific treatment. Imaging of the heart and pulmonary vasculature is critical to assigning a patient's PH syndrome to the correct WHO category and is also important in predicting outcomes. Imaging studies often reveal that the etiology of PH in a patient reflects contributions from several categories. Overlap between Categories 2 and 3 (left heart disease and lung disease) is particularly common, reflecting shared risk factors. Correct classification of PH patients requires the combination of standard imaging (chest roentgenograms, ventilation-perfusion scans, echocardiography, and the 12-lead electrocardiogram) and advanced imaging (computed tomography, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography). Despite the value of imaging, cardiac catheterization remains the gold standard for quantification of hemodynamics and is required before initiation of PH-specific therapy. These cases illustrate the use of imaging in classifying patients into WHO PH Categories 1-5.

Keywords: CREST, Eisenmenger's syndrome, late gadolinium enhancement, pulmonary artery acceleration time, pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis, pulmonary veno-occlusive disease, right ventricular hypertrophy

INTRODUCTION

Reviews of pulmonary hypertension (PH) almost invariably begin with a hemodynamic definition accompanied by a reference to the five categories or groups of PH.[1,2] The hemodynamic definition of PH (mean pulmonary artery pressure, mPAP, at rest greater than 25 mmHg) is relatively straightforward, although estimations of PA pressures by echocardiography can be unreliable.[3] The clinician's challenge arises when reviewing the differential diagnosis to place the PH patient into one of the five WHO categories (Table 1). This classification has practical importance because there are category-specific treatments, such as medical therapies for pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) (Category 1 PH),[4,5] supplemental oxygen or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for Category 3, and pulmonary artery endarterectomy for Category 4 PH, chronic thromboembolic PH (CTEPH).

Table 1.

Updated WHO PH classification

Despite the importance of imaging to the categorization of PH, there is a paucity of articles showing representative diagnostic images for the WHO categories of PH. This visual compendium of images obtained in patients in each of the PH categories is meant to illustrate key diagnostic imaging features of each PH category and demonstrates the role of multimodality imaging in the categorization of PH. Conventional imaging (computed tomography (CT), echocardiography and Ventilation-perfusion scans (VQ scans)) are used to identify cardiac shunts, pulmonary emboli and to characterize parenchymal lung disease. Doppler echocardiography is used to estimate pulmonary artery pressure (PAP). Although the ECG is technically not an imaging tool, it offers a noninvasive assessment of the status of the RV. Advanced imaging can monitor pulmonary vascular density and compliance and evaluate the metabolism, function, and vascularity of the hypertrophied right ventricle (RV). Although pulmonary angiography is largely reserved for Category 4 PH, the role of left and right heart catheterization in achieving correct categorization remains paramount.

OVERVIEW OF THE WHO PH CLASSIFICATION

Category 1 PH (PAH) is diverse and is unified by histological similarities amongst the represented diseases and the shared elevation of pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR). Category 1 includes idiopathic and familial PH, as well as PH associated with conditions such as collagen vascular disease, congenital shunts, cirrhosis and portal hypertension, HIV, hemoglobinopathies, and schistosomiasis. It also includes PH associated with drugs, such as anorexigens or amphetamines.[2] The diagnosis of Category 1 PH is largely a diagnosis of exclusion (i.e., excluding Categories 2-5 PH), a process in which imaging is crucial. Images of idiopathic PAH and PAH due to atrial septal defect (ASD) with Eisenmenger's physiology are shown (Figs. 1–7). In addition, complications of severe Category 1 PH are illustrated, including compression of the left main coronary artery (Fig. 5) and calcification of the proximal pulmonary artery (PA) (Fig. 3). Imaging can also provide clues to the subcategory of Category 1 PH, as illustrated in a patient with pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis (PCH) (Figs. 6 and 7). Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) can quantify RV volumes and size and, when performed using gadolinium as a contrast agent, provides prognostic information.

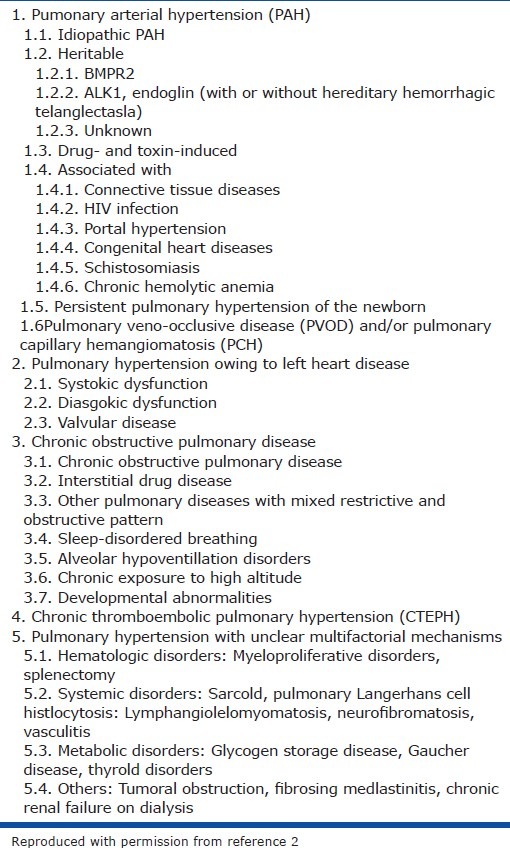

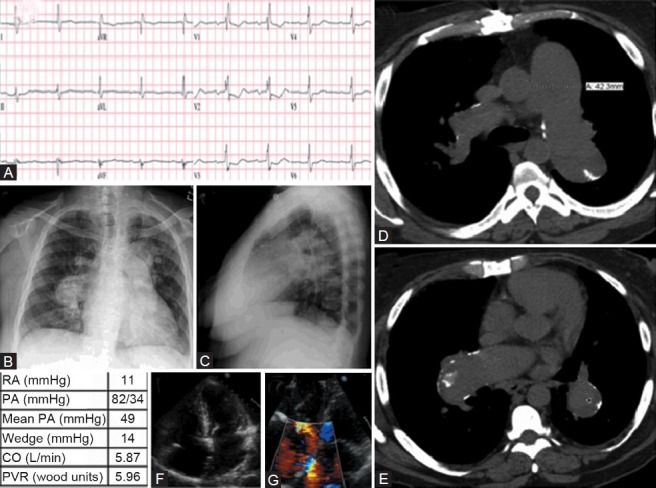

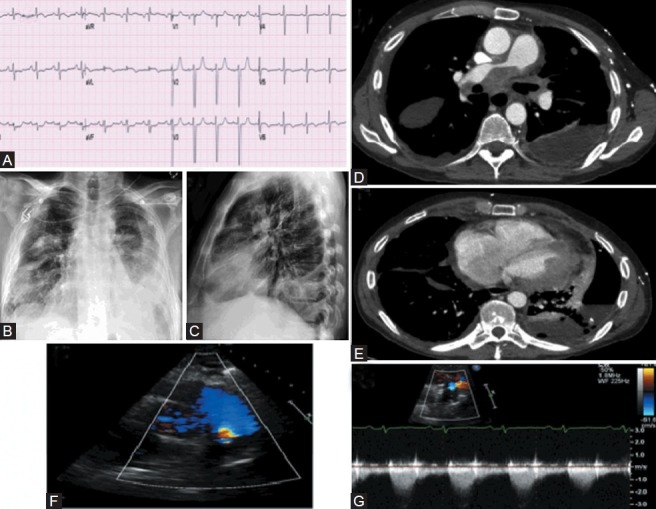

Figure 1.

Images obtained in a 43-year-old female with idiopathic PAH. (A) S1Q3T3 pattern noted consistent with right ventricle strain. T-wave inversion on anterior leads and ST depression is also suggestive of RVH with strain (note early R wave predominance in V1-V2 consistent with RVH). (B) Chest X-ray showing enlarged pulmonary artery and pruning of the distal pulmonary vasculature. (C) Lateral chest X-ray showing filling of the retrosternal space by an enlarged RV. (D) Parasternal long axis echocardiography view showing dilated RV. (E) Parasternal short axis echocardiography view showing flatted interventricular septum (thin white arrow), severely dilated RV and pericardial effusion (thick white arrow). (F) Tricuspid regurgitation velocity (represented by *) is proportional to right ventricular systolic pressure and estimated by Bernoulli's equation. (G) Measurement of PAAT (time from onset of flow to peak velocity) (thin white arrow). Note the notching of the PA Doppler envelope, suggestive of pulmonary vascular hypertension (thick white arrow). (H) “Moth eaten” appearance of ventilation/ perfusion scan in idiopathic PAH with patchy perfusion defects, in this case predominantly in the left lower lobe. (I, J) Histopathology from a different patient with Category 1 PAH showing medial hypertrophy and intimal fibrosis of small (<200 μm) PAs

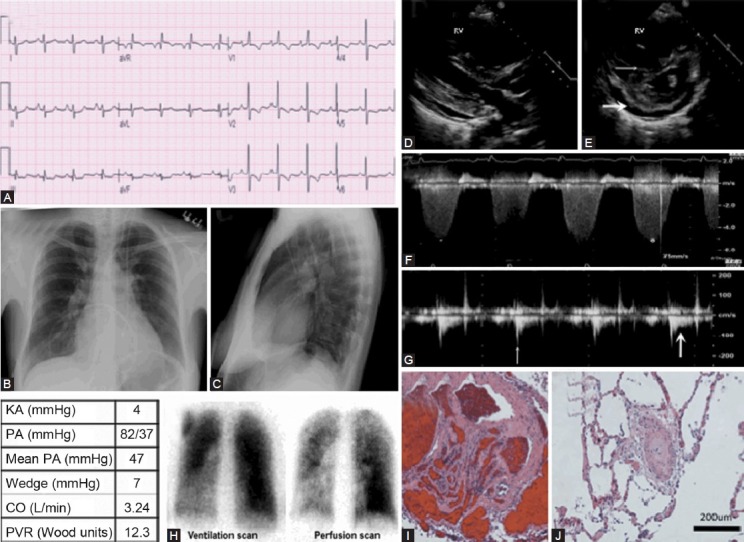

Figure 7.

Category 1 PH due to a second case of pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis. (A) ECG showing sinus tachycardia and right atrial enlargement. (B) Chest X-ray on presentation with cardiomegaly and clear lung fields. (C) Chest X-ray after initiation of sildenafil showing pulmonary edema. (D) Ventilation-perfusion scan showing accentuation of basilar perfusion images. (E) Gross dissection of the heart shows thickened and dilated RV. (F) Patchy areas of pulmonary capillary proliferations engorged with red blood. (G) Concentric intimal fibrosis and medial hypertrophy of pulmonary arteries and arterioles.

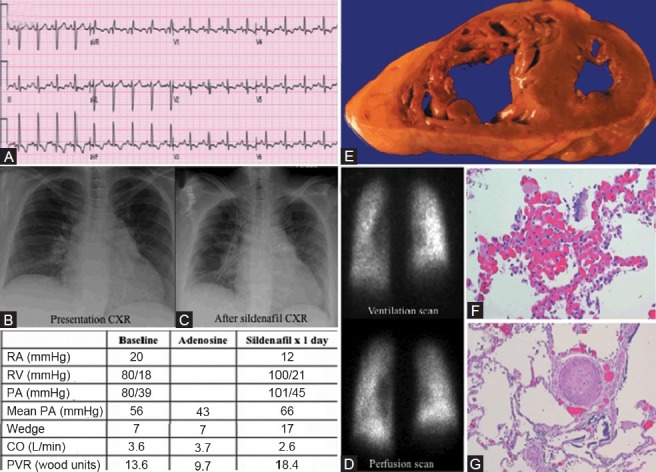

Figure 5.

Patient with ASD and left main coronary artery compression. (A) ECG showing right atrial enlargement and severe RVH. (B) Chest X-ray showing severely enlarged PA. (C) Lateral chest X-ray showing filling of the retrosternal space. (D, E) Coronary angiogram showing compression of left main coronary artery (small caliber of left main, white arrow). (F) Transverse section at level of bifurcation of pulmonary artery showing proximity of left pulmonary artery (LPA) to the left main coronary artery and compression (white arrow). RPA: Right pulmonary artery; Ao: Aorta. (G) Sagittal views left main coronary artery (white arrow) compressed by pulmonary artery (PA).

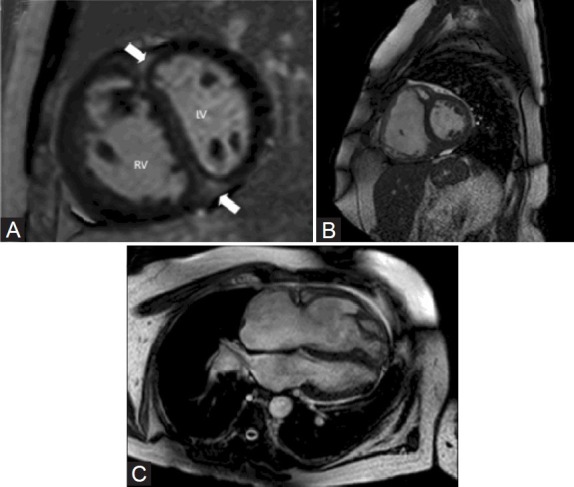

Figure 3.

Calcified PAs in a patient with atrial septal defect (ASD) and Eisenmenger's physiology. (A) ECG shows first-degree AV block, right bundle branch block. (B, C) Chest X-ray showing enlarged and calcified pulmonary artery. (D, E) Axial CT scan below the carina demonstrates calcification of the left and right pulmonary arteries. (F) Apical four-chamber echocardiography view showing ASD. (G) Color-flow Doppler echocardiogram showing flow through the ASD with right-to-left shunt that caused her paradoxical embolic stroke.

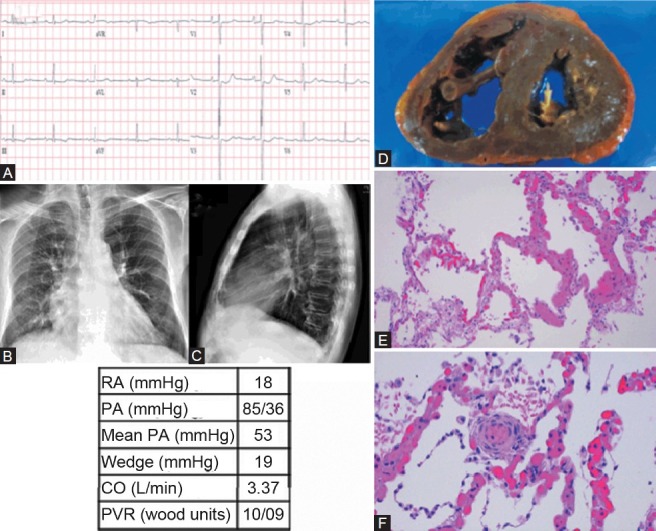

Figure 6.

Category 1 PH diagnosed postmortem as secondary to pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis (PCH). (A) ECG shows mild left ventricular hypertrophy and right atrial enlargement. (B, C) Chest X-ray shows PA enlargement and cephalization with Kerly B lines. (D) Gross dissection of the heart shows thickened and dilated right ventricle. (E) Pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis, seen as increased numbers of pulmonary capillaries swollen with large numbers of red blood cells, sharply demarcated from normal-appearing lung parenchyma (H and E, ×100). (F) Muscularization of a small-caliber arteriole. Surrounding alveolar septal capillaries with changes of pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis (H and E, ×200).

Classification into Category 1 is not as simple as identifying that a patient has a Category 1-associated disease. For example, while sickle cell disease is in Category 1 (because some patients develop pulmonary vascular remodeling), sickle cell patients can often develop Category 2 PH, due to secondary hemochromatosis and a secondary restrictive cardiomyopathy. Certain subsets of Category 1 PH have significant lung disease that can complicate attribution of their PH to a single category (notably scleroderma patients who often have parenchymal lung disease, Category 3).

Category 2 is the collection of PH syndromes resulting from left ventricular (LV) or left-sided valvular disease. Whether due to mitral stenosis, cardiomyopathy or LV diastolic dysfunction, Category 2 patients have PH due in large part to increased left atrial pressure. Category 2 is the most common form of PH and while there is no approved PH-specific therapy for this category, PH does confer adverse prognosis to these patients (as is the case in Categories 3 and 5). Classically, Category 2 patients are defined at catheterization by an elevated pulmonary-wedge pressure and a modest transpulmonary gradient (usually <10 mmHg difference between mean PA and wedge pressure). However, increasingly cases are identified where the transpulmonary gradient is increased disproportionately.[6] In such cases, there is likely pulmonary vascular remodeling. Such a case of disproportionate Category 2 PH is illustrated in Figure 8. In Figures 9 and 10, we present cases of restrictive physiology causing PH.

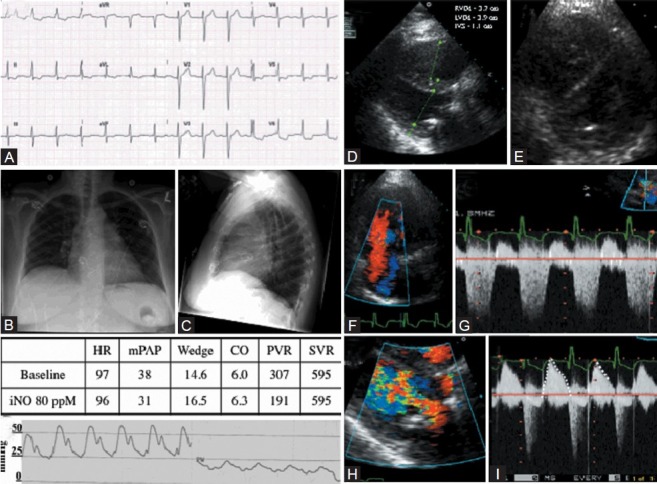

Figure 8.

Category 2 PH after mitral valve repair. (A) Normal sinus rhythm with lateral T wave flattening. (B) Chest X-ray showing splaying of carina and left atrial enlargement. (C) Lateral chest X-ray showing mitral ring in place and RV enlargement. (D) Representative long axis echocardiography view showing RV enlargement, left ventricular hypertrophy (RVDd: Right ventricular diastolic diameter; LVDd: Left ventricular diastolic diameter; IVS: Interventricular septum). (E) Parasternal short axis echocardiography view showing septal flattening. (F) Color flow Doppler showing severe TR. (G) TR velocity and waveform. (H) Turbulence across the prosthetic mitral valve. (I) CW Doppler flow across mitral valve showing normal gradient for size (dashed tracing) and short half-time (dashed line) suggesting normally functioning mitral valve repair. Pressure half-time of >180 ms may be abnormal. (J) Pulmonary artery pressure tracing and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure tracing showing pulmonary hypertension and normal pulmonary wedge (PW) pressure.

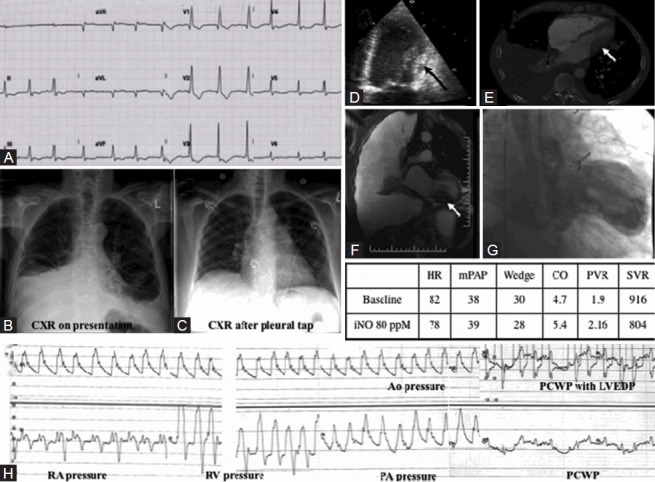

Figure 9.

Category 2 PH secondary to restrictive physiology. (A) ECG showing diffuse T wave inversion. (B) Chest X-ray with right-sided pleural effusion on presentation. (C) Chest X-ray after pleurocentesis left-sided heart enlargement is apparent. (D) Apical 4-chamber echocardiography view showing thickening of the lateral LV wall (black arrow). (E) CT scan showing fibrotic lung disease with right pleural effusion and left ventricle wall mass (white arrow). (F) Cardiac MRI showing right-sided pleural effusion and LV wall mass secondary to growth from non-Hodgkins lymphoma in thorax (white arrow). (G) Still-frame left ventriculogram showing restriction of filling due to extrinsic compression. (H) Simultaneous right and left heart catheterization showing equalization of diastolic filling pressures at ~28 mmHg. PVR in this study was normal (1.9 Wood Units), indicating that the PH was not due to pulmonary vascular disease.

Figure 10.

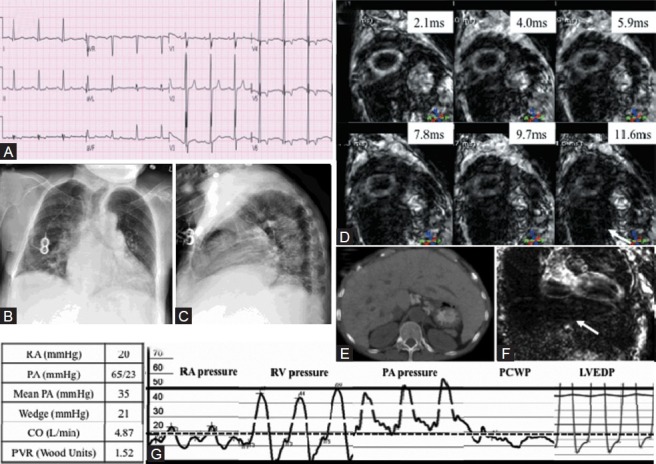

(A) ECG showing left ventricular hypertrophy. (B, C) Chest X-ray showing cardiomegaly. (D) T2 Star Cardiac MRI short axis images demonstrating reduced T2 star time <10 ms suggesting significant iron overload and no signal from dark liver (white arrow). (E) CT transverse section of abdomen showing hepatomegaly. (F) T2 Star MRI of the liver showing total darkness consistent with iron overload (white arrow). (G) Simultaneous right and left heart catheterization showing near-equalization of diastolic filling pressures at ~20 mmHg.

Category 3 PH is PH secondary to chronic lung diseases, hypoxia or both (e.g., sleep apnea). This category of PH is characterized by mild elevations in PAP.[7] As with Category 2, however, there are Category 3 patients in whom the PH is disproportionately severe, as compared to their lung disease. We present a case of obstructive sleep apnea with severe PH (Fig. 11).

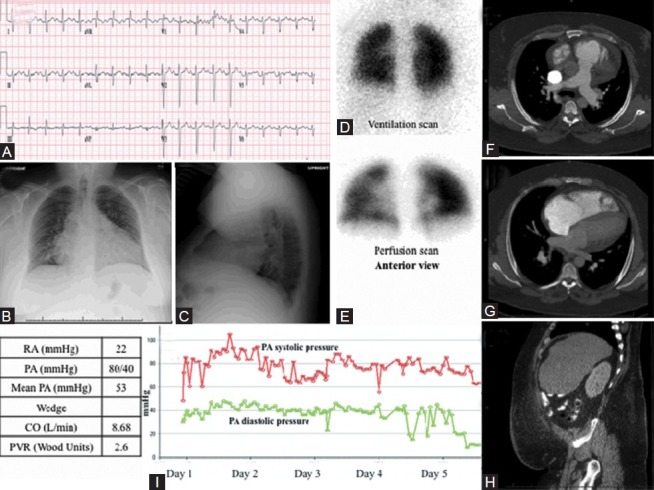

Figure 11.

Images obtained in 35-year-old male with cor pulmonale. (A) S1Q3T3 pattern noted consistent with right ventricle strain. RVH is evident from the prominent R wave in the early precordial leads. Evidence of pulmonary disease, with failure of R wave transition and presence of Rs in V4. (B, C) PA and lateral chest X-ray with severe 4-chamber cardiomegaly with pulmonary vascular redistribution and visible obesity. (D, E) Normal VQ scan, performed anteriorly due to excess obesity. (F-H) CT showing moderate to severe cardiomegaly with normal lung parenchyma, mild dependent hypoventilatory changes and abdominal obesity. (I) PA pressure measurements decrease over the course of first 5 days of hospitalization while receiving CPAP and intensive diuresis (red line: Systolic PAP, green line: Diastolic PAP).

Category 4 PH (CTEPH) is unique because it represents the form of PH that is curable without transplantation.[8] In this review, we present a severe case of CTEPH (Fig. 12). Perfusion lung scanning can be helpful for the diagnosis, but will not reveal the proximal extent of the thromboemboli. In addition, patients with nonocclusive thrombi may have normal distal lung perfusion in those segments giving a false negative impression. While noninvasive imaging is key to the diagnosis of CTEPH, there are cases in which the CT angiography fails to detect the intimately incorporated thrombus, which forms a neointima.[9] This reminds one of the need for pulmonary angiography when the index of suspicion is high.

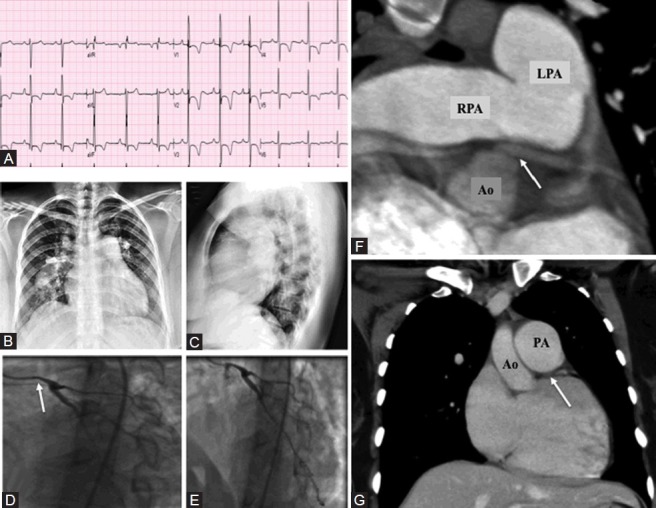

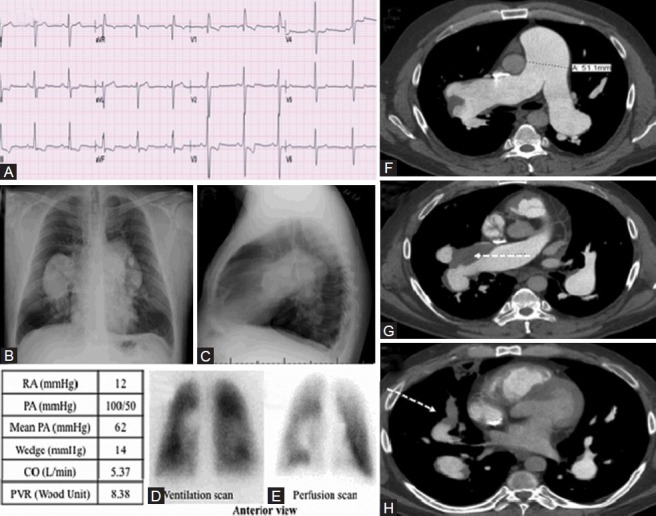

Figure 12.

WHO Group 4 – chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. (A) Twelve-lead electrocardiogram showing S1Q3T3 suggestive of right ventricular strain, and right axis deviation. (B, C) Chest X-ray: Massively enlarged central pulmonary arteries. (D-E) Ventilation perfusion scan revealing perfusion defect in left lower lobe (F-H) Computed tomographic pulmonary angiogram demonstrating massively dilated main pulmonary artery, eccentric mural thrombus in the right main pulmonary artery and its proximal branches (dashed white arrow).

Category 5 PH represents a heterogeneous collection of PH syndromes secondary to systemic diseases (i.e., sarcoidosis, histiocytosis X), hematological disorders (such as polycythemia vera or chronic myeloid leukemia) and extrinsic compression of the pulmonary artery. Two Category 5 PH cases due to examples of extrinsic PA compression, one caused by mediastinal calcification and the other by nonsmall cell lung cancer, are shown (Figs. 13 and 14), respectively).

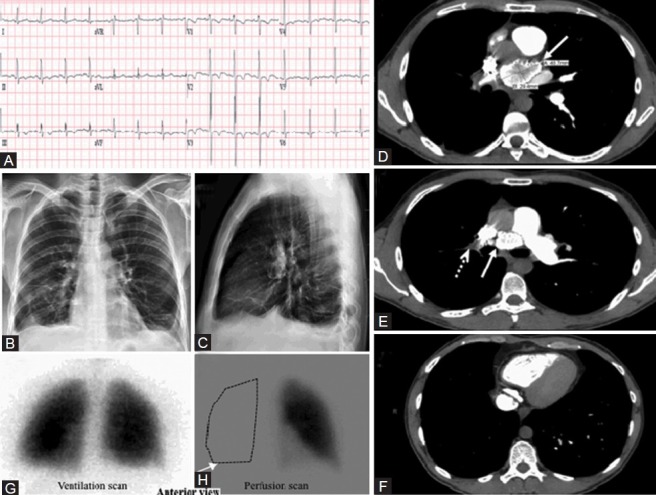

Figure 13.

WHO Group 5 – Pulmonary hypertension with unclear or multifactorial etiologies. (A) ECG showing left ventricular hypertrophy. (B, C) Chest X-ray, PA and lateral with no edema or cardiomegaly. (D) Computerized tomographic scan of the chest showing a 4.9 × 2.9 cm calcified mediastinal mass compressing the right main pulmonary artery (white arrow). (E) A filling defect from a thrombus in the right main pulmonary artery (dashed white arrow). (F) CT scan showing oligemia of the entire right lung. (G, H) VQ scan showing a complete absence of perfusion to the entire right lung (white arrow).

Figure 14.

Category 5 PH. (A) ECG showed non-specific TW flattening. (B, C) Chest X-ray showed left-sided pleural effusion. (D, E) CT scan showed extensive confluent mediastinal and bihilar lymphadenopathy, compressing both pulmonary arteries, right more so than left. The tumor was also seen around the pericardium. Left-sided pleural effusion is visualized. (F) Right ventricular outflow tract echocardiogram color flow view showing turbulence distal to the pulmonic valve. (G) Pulsed wave Doppler across stenosis showing flow acceleration, with flow of 2 m/s (compared with normal of 1 m/s).

CATEGORY 1 PH

Category 1 PH: 43-year-old female with pulmonary arterial hypertension

A 43-year-old female was referred for management of PH. She had initially presented 1 year prior for evaluation of progressive dyspnea and fatigue. Her ECG showed right axis deviation with right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH) and a strain pattern (manifest as early R-wave transition in V1-V2 with ST depression in V1-V4). She also had the S1Q3T3 pattern, defined as a prominent S wave in lead I, Q wave in lead III and T wave inversion in lead III. S1Q3T3 is more commonly seen with pulmonary embolism but can reflect RV strain of any cause, as shown in Figure 1A.[10]

Chest X-ray was consistent with PH with enlarged pulmonary arteries bilaterally, distal pruning of the pulmonary blood vessels and filling-in of the retrosternal airspace on the lateral film, consistent with right ventricular enlargement (Fig. 1B and C). Enlargement of the right descending PA >20 mm is quite specific for PH.[11]

Her transthoracic echocardiogram showed severe RV dilatation with flattening of the interventricular septum and LV compression consistent with RV pressure and volume overload (Fig. 1D and E). Flattening of the interventricular septum that occurs only in diastole reflects right-sided volume overload; however, systolic septal flattening indicates that there is also right-sided pressure overload with right-sided systolic pressures approximating left ventricular systolic pressures.

The tricuspid regurgitation (TR) velocity, obtained using continuous-wave Doppler (Fig. 1F), is used to estimate RV systolic pressure, which is equal to the PA systolic pressure in the absence of pulmonic stenosis, by applying Bernoulli's equation (PAPsystolic=4V2+estimated RA pressure; where V is the average peak TR velocity). Difficulties in aligning the Doppler parallel to the TR jet or the paucity of TR may preclude accurate assessment of PA systolic pressures.[3] Moreover, although TR velocity can quantify PA pressure, the morphology of the TR jet does not vary with changes in the compliance of the pulmonary vasculature, unlike PAAT, and thus the TR signal does not help categorize PH.

In contrast, a less frequently used measure, the pulmonary artery acceleration time (PAAT), can be readily obtained in most patients and provides evidence of the state of pulmonary vascular remodeling (Fig. 1G).[12] To obtain the PAAT, defined as the time from the onset of flow to the peak of the ejection flow velocity (Fig. 1G), the pulsed-wave Doppler sample volume is placed parallel to flow in the main PA. Because the difference in PAAT between normal PA pressure and severe PH is small, it is crucial to record the signal at high sweep speed and optimize the filtering and velocity scale. The shorter the acceleration time, the more severe the PH with a value of <80 ms being regarded as abnormal.[13] In order to estimate mean PAP using PAAT, each echocardiography laboratory should determine a regression equation correlating mean PAP, measured by catheterization, with PAAT. In PH due to pulmonary vascular disease the PA Doppler envelope develops systolic notching. This notch results from a reflection wave from the noncompliant pulmonary vasculature that “cancels” forward velocity. In rodent models, shortening of the PAAT with notching routinely develops as PAH progresses and these changes resolve with experimental therapies.[14]

A nuclear ventilation/perfusion (VQ) scan which shows some patchy perfusion defects is consistent with Category 1 PH (Fig. 1H). Both this “moth-eaten” appearance on the perfusion scan and the pruning on chest X-ray (loss of arterial markings in the lung periphery) reflect the small vessel obliteration that typifies Category 1 PH. These are the imaging correlates of the histological changes seen in PAH (Fig. 1I and J). Hemodynamic measurements by right heart catheterization (RHC) at the time of diagnosis are shown in the table in Figure 1. The patient was started on sildenafil and subcutaneous treprostinil and ultimately transitioned to intravenous prostaglandins. This therapy was maintained for 6 years before the patient succumbed to RV failure.

Imaging lesson

The vascular remodeling of the distal resistance pulmonary arterioles, which is a hallmark of Category 1 PH, can be detected by the notching observed in PA Doppler at echocardiogram as well as the vascular pruning seen in chest X-ray and the “moth-eaten” appearance of the VQ scan. The RVH and strain pattern on ECG and RV pressure-volume overload, on transthoracic echocardiogram, help quantify the disease severity but are not specific for Category 1 PH.

Category 1 PH: CMR imaging to assess the RV

In Figure 2, we present two patients with PAH who have dilated right ventricles. Panel A is a 36-year-old female with WHO functional class IV PAH on intravenous (IV) treprostinil. Panel 2B-C is a 61-year-old male with PAH who was WHO functional class II on sildenafil. In Figure 2A, the late gadolinium enhancement at the RV insertion is shown. In Figure 2B and C, a severely dilated RV is seen.

Figure 2.

(A) Cardiac MRI image showing late gadolinium enhancement in the RV insertion site (thick white arrow). (B, C) Cardiac MRI showing dilated right ventricle.

Imaging lesson

CMR has contributed greatly to the evaluation of PH patients. RV morphology on CMR can predict the extent of PAP elevation.[15] Also, late gadolinium enhancement at the insertion point of the RV has been studied as a prognostic indicator in PH patients.[16] CMR permits reproducible measurements of RV volumes.[17] Arguably, CMR should be a routine part of the diagnosis and follow-up of PH patients.

Category 1 PH: ASD with paradoxical embolization and calcified pulmonary arteries

This 56-year-old female has Category 1 PH secondary to an ostium secundum atrial septal defect (ASD) and Eisenmenger's physiology, with bidirectional interatrial flow after a failed pericardial patch repair 12 years prior. She had a paradoxical embolism causing a right hemispheric stroke 1 year prior to admission. ECG shows first-degree atrial-ventricular and right bundle branch block, both common in ASD (Fig. 3A). Chest X-ray (Fig. 3B and C) shows enlargement and calcification of the proximal PAs and pruning of the peripheral PAs. PA calcification reflects long-standing PAH typically associated with congenital heart disease with shunt lesions.[18,19] Extensive calcification within both pulmonary arteries was also confirmed on chest CT (Fig. 3D and E). Echocardiogram showed an atrial septal defect with bidirectional flow and concentric RVH with preserved RV systolic function (Fig. 3F and G). Her RHC confirmed that the PH was pulmonary vascular in origin (i.e., high transpulmonary gradient and PVR, table in Fig. 3) and demonstrated that she was a vasodilator “nonresponder.” Despite declining IV epoprostenol, the patient remains WHO functional class II on sildenafil and bosentan after 7 years.

Imaging lesson

This patient's concentric RVH and preserved RV systolic function portend a good outcome, as does the etiology of her subcategory of PH 1 (congenital heart disease). The essential role of echocardiography in assessing the interatrial septum and evaluating RV function is illustrated. Calcified PAs are most commonly seen with Category 1 PH associated with congenital heart diseases (patent ductus or ASD), although calcified PA thrombi have been reported in Category 4 PH.[20]

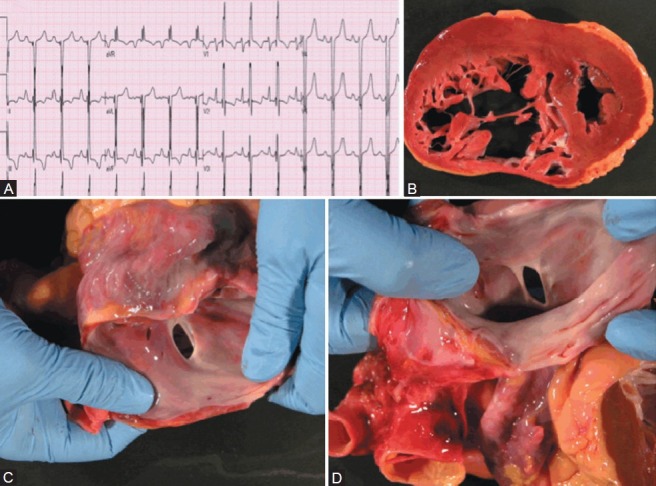

Category 1 PH: Cardiac arrest in Eisenmenger's syndrome

In contrast to Figure 3, whose subject was WHO functional class II despite severe PAH, Figure 4 shows the autopsy findings of a female in her third decade. This patient also had a secundum ASD and Eisenmenger's physiology but suffered out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. An ECG obtained shortly before her death shows severe right axis deviation and RVH (Fig. 4A). This is consistent with the dilated right ventricle with focal thinning noted at autopsy (Fig. 4B). Figure 4C and D shows the anatomy of the ostium secundum ASD.

Figure 4.

Congenital heart disease patient (ASD) with out-of-hospital sudden cardiac death. (A) ECG showing severe RVH. (B) Severe RV hypertrophy and dilatation. (C, D) Ostium secundum atrial septal defect.

Imaging lesson

Most PH patients develop symptoms or die when the RV thins, dilates and/or becomes hypokinetic.

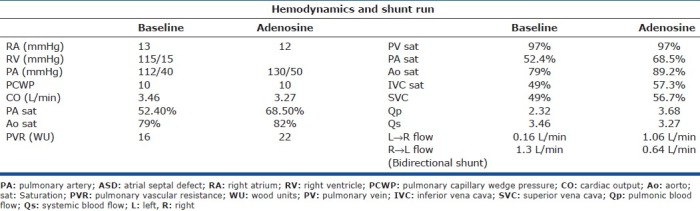

Category 1 PH: Compression of the left main coronary artery by hypertensive PAs

This case demonstrates an uncommon but well-described clinical complication of severe PH secondary to ASD. This WHO functional class IV 28-year-old female was referred for evaluation of PH. She had been doing well until 4 years prior to presentation when she developed progressive dyspnea and syncope. Transthoracic echocardiogram at that time showed severe RV dilatation and ASD. The ASD was deemed unsuitable for closure due to systemic desaturation and elevation in RV pressures on transient occlusion of the ASD. Transthoracic echocardiography confirmed the presence of ASD and RV dilatation. The patient underwent RHC (Table 2). Based on the negative response to vasodilator therapy (a rise in PAP and fall in cardiac output), the patient was referred for evaluation for lung transplantation. As part of the evaluation, the patient underwent coronary angiography and was found to have left main compression resulting from severe enlargement of her main PA (Fig. 5D and E). CT scan confirmed this and the proximity of the PA to left main coronary artery is illustrated (Fig. 5F and G).

Table 2.

Hemodynamics and shunt study in a patient with ASD and left main coronary artery compression by a dilated main pulmonary artery

Most cases of left main compression due to PA enlargement are complications of ASD, ventricular septal defect (VSD) or tetralogy of Fallot (TOF).[21] They can be an incidental finding or present with angina or dyspnea. Enlarged PAs in PH can also compress the proximal airways. The optimal management of this PH complication is uncertain with some proponents for left main stenting if LV ischemia is demonstrated.[22] In this case the patient was referred for consideration of combined heart and lung transplantation.

Imaging lesson

Mitsudo et al. reported narrowing of left main coronary artery in 44% of 16 ASD patients with PH,[23] indicating that it is not an uncommon complication.

Category 1 PH: Apparent mixture of categories 2 and 3 PH diagnosed as PCH on autopsy

A 69-year-old male with a history of essential hypertension, coronary artery disease, and past smoking history developed worsening dyspnea and fatigue 1 year before presentation. He had a history of sleep apnea but was poorly compliant with CPAP. A drug-eluting stent was placed in his left circumflex coronary artery 1 year prior to his presentation. ECG showed right atrial hypertrophy (and mild left ventricular hypertrophy [Fig. 6A]). Chest X-ray (Fig. 6B and C) showed cephalization of pulmonary vasculature with bilateral PA enlargement and hyperinflated lungs. There were increased interstitial markings and Kerley B lines. Echocardiogram showed normal left ventricular function, dilated right ventricle and elevated left-sided filling pressures. Right heart catheterization showed elevated PAP and a pulmonary capillary wedge pressure of 19 mmHg (table in Fig. 6). The patient's DLCO was 43% of the predicted level on PFTs without significant evidence of obstructive or restrictive airway disease. Therapy included improved blood pressure control (using an angiotensin receptor blocker) and the off-label use of the phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor, sildenafil, for presumptive Category 2 PH.[24] The patient's functional class improved from WHO IV to WHO II and he did well for 2 years but ultimately expired due to azotemia and decompensated RV failure (which persisted despite admission for diuresis and inotropic support). His autopsy revealed an enlarged heart weighing 645 g with four-chamber dilatation (Fig. 6D). The RV wall thickness was at the upper limit of normal (0.5 cm, consistent with the absence of RVH on ECG). Lung histology (Fig. 6E and F) revealed medial hypertrophy and muscularization of small PAs and surprisingly demonstrated PCH, highlighting the frequent overlap in categories that can occur within patients and also the limitations of imaging in definitive classification.

Imaging lesson

This case illustrates one of the persistent difficulties in appropriately categorizing patients and in turn determining the best treatment options for patients with a new diagnosis of PH. The interstitial changes seen on chest X-ray, although initially concerning for pulmonary edema, can also be seen with PCH or pulmonary veno-occlusive disease. This patient responded well both clinically and hemodynamically to off-label phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition. He satisfied clinical diagnostic criteria for diastolic dysfunction (Category 2 PH); however, post-mortem results showed features of PCH, illustrating the importance of obtaining an autopsy whenever possible in PH patients.

Category 1 PH: Pulmonary edema with vasodilators in a patient with post-mortem diagnosis of PCH

A 54-year-old female presented with a 5-month history of dyspnea, orthopnea, lower leg swelling, and a recent 15-lb weight gain. The patient had a history of CREST syndrome with limited scleroderma, an antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and a recent diagnosis of PAH by RHC. Chest X-ray on presentation (Fig. 7B and C) showed cardiomegaly and no interstitial disease. VQ scan (Fig. 7D) showed accentuation of basilar perfusion. RHC (table in Fig. 7) results classified the patient as a borderline vasodilator responder (mean PAP fell from 56 mmHg to 43 mmHg with adenosine). The right coronary artery (RCA) was also found to be stenotic and the 80% lesion in her relatively small RCA was stented. The patient was started on sildenafil. The following day the patient became hypotensive and dyspneic. Chest X-ray at that time (Fig. 7C) was significant for subtle signs of pulmonary edema. Pressures and PVR on a repeat RHC were increased (table in Fig. 7). The patient was managed supportively in the ICU with vasopressors and diuretics before being discharged home 1 week later. While at home, the patient experienced in-stent thrombosis of her RCA. On readmission, care was ultimately withdrawn and the patient expired.

On autopsy, the heart was enlarged (690 g) with biventricular dilatation (Fig. 7E). In all lung sections, there were multifocal and patchy areas of pulmonary capillary proliferations engorged with red blood cells (Fig. 7F). There was marked and diffuse concentric intimal fibrosis and medial hypertrophy of the small PAs. Some vessels were almost entirely occluded (Fig. 7G). No plexiform lesions were identified. The extensive multifocal proliferation of capillaries along with arteriolar thickening supports a diagnosis of PCH.

Imaging lesson

PCH remains a very difficult diagnosis to make antemortem. In retrospect it was suggested in this case by the development of pulmonary edema and worsened pulmonary hypertension after the introduction of a vasodilator (sildenafil),[25] and the accentuation of basilar perfusion on the VQ scan.[26]

CATEGORY 2 PH

Category 2 PH: Persistent PH after correction of aortic stenosis and mitral insufficiency disease

A 56-year-old female presented 1 month after an aortic valve replacement (AVR) for aortic stenosis (AS) with concomitant mitral and tricuspid valve repair for mitral regurgitation (MR) and TR. The accompanying chest X-ray showed left atrial enlargement, evident from flattening of the left heart border and splaying of the carina (Fig. 8B and C). The echocardiogram showed RV enlargement and LVH (Fig. 8D and E) as well as significant TR with elevated estimated RVSP (Fig. 8F and G). The aortic prosthesis functioned normally. Although there was mild gradient across the mitral valve prosthesis (Fig. 8H and I), the normal pressure half-time was indicative of a nonstenotic repaired valve (Fig. 8I). The pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was mildly elevated at 12 mmHg (Fig. 8J); however, the transpulmonary gradient was increased and was dynamic, decreasing with inhaled nitric oxide.

Imaging lesson

This patient's dyspnea and PH following mitral surgery reflect an elevated transpulmonary gradient as a result of a dynamic elevation in pulmonary vascular tone. The vasodilator responsiveness in this case suggests a possible role for therapy with sildenafil (off-label) and would only be identified if the noninvasive diagnosis of PH were investigated by a RHC.

Category 2 PH: Restrictive cardiomyopathy caused by tumor infiltration

This 72-year-old male had non-Hodgkin's lymphoma presenting as a neck mass 20 years prior to presentation. He was treated with chemotherapy and local radiation therapy. Six months prior to presentation, he developed a large mass on his right neck which on biopsy was found to be recurrent non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and he was treated with local radiation therapy. One month prior to admission he developed dyspnea, pedal edema, and ascites, with a 30-lb weight gain. On exam, the patient had a JVP 18 cm above the manubrio-sternal angle with a steep Y descent, 2+ pitting edema to shin, ascites, hepatomegaly, and decreased breath sounds on the right lung with dullness to percussion and decreased vocal fremitus. Chest X-ray confirmed right-sided pleural effusion (Fig. 9B), which after pleurocentesis showed cardiomegaly (Fig. 9C). Echocardiogram was significant for right ventricular enlargement, flattening of interventricular septum, and thickening of the lateral wall of the left ventricle (Fig. 9D). CT chest showed fibrotic lung disease likely secondary to radiation therapy, pleural effusion, but most importantly, a left ventricular wall mass (Fig. 9E). On CMR, the mass was extrinsic to the heart and deformed the inferior wall of the LV (Fig. 9F). The patient underwent left ventriculography (Fig. 9G) confirming that the mass impinged upon and distorted the inferior wall of the left ventricle. Simultaneous right and left heart catheterization confirmed that the PH reflected restrictive physiology diagnosed by the near equalization of diastolic pressures, the steep Y descent and the “square root sign” of the RV diastolic pressure trace (Fig. 9H). This PH resulted from recurrent non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma causing LV restrictive physiology. Upon receiving therapy for his tumor, the mass shrank and the RV failure signs and symptoms resolved.

Imaging lesson

This case illustrates the utility of imaging in identifying the PH as Category 2 based on the presence of an extracardiac mass. However, the key role of hemodynamics in confirming that the etiology of the PH and right heart failure reflected restrictive physiology is paramount.

Category 2 PH: The complexities of categorization of PH – not all Sickle cell PH is Category 1 PH

A 53-year-old African-American female with sickle cell disease was admitted to the coronary care unit with a diagnosis of RV failure. She had multiple hospital admissions for dyspnea and volume overload, and Doppler echocardiography had identified elevated PAP. She had previously been presumptively classified as Category 1 PH (without a RHC), based on the history of sickle cell disease. During the current admission, she had hepatic encephalopathy with hyperammonemia (ammonia: 276 mcg/dl. normal values 20-70 mcg/dl) and was found to have hepatomegaly on CT (Fig. 10E). Her ferritin level was 9811 ng/ml (normal values: 10-220 ng/ml). Invasive hemodynamics confirmed PH (table in Fig. 10) but showed near-equalization of diastolic pressures consistent with the restrictive physiology of an infiltrative cardiomyopathy (Fig. 10G). Ultimately, myocardial iron overload secondary to chronic blood transfusion was confirmed by CMR (Fig. 10D). In the CMR, the T2-star short axis images should retain an intense (“bright”) myocardial signal for the entirety of the series of images presented here. T2-star time in the normal myocardium is >20 ms. This patient's T2-star time is <10 ms, consistent with significant iron overload and has been associated with a very poor prognosis and ventricular arrhythmia independently of liver iron content and serum ferritin.[27,28] Also, on T2-star imaging, the liver appears very dark, again consistent with severe iron overload (Fig. 10F). The patient was subsequently initiated on IV desferrioxamine therapy, which has been shown to improve LV function in patients with secondary hemochromatosis.[29]

Image lesson

This case reinforces the fact that the presence of a PH-associated disease is insufficient to categorize a patient. PH is prevalent among patients with sickle cell disease, recently shown to be present in 6% of patients.[30] While the presumed etiology of PH associated with hemolytic anemias such as thalassemia is pulmonary vascular disease, histologically similar to other disease entities within Category 1 PH,[31] a RHC is required to accurately categorize PH and in this case dramatically altered therapy.

CATEGORY 3 PH

Category 3 PH: The Pickwick Papers redux

A 35-year-old welder with Class IV obesity (BMI 65 kg/m2) presented to the emergency room for a 3-month history of weight gain, dyspnea and edema. His family reported he had periods of apnea and daytime hypersomnolence. He had cirrhosis and thrombocytopenia with portal hypertension, possibly secondary to alcohol use. ECG showed right axis deviation, incomplete right bundle branch, S1Q3T3 pattern and delayed R wave transition consistent with lung disease (Fig. 11A). Initial chest X-ray showed severe four-chamber cardiomegaly with pulmonary vascular redistribution (Fig. 11B and C). Transthoracic echocardiogram showed a severely dilated RV and severely reduced RV performance but normal left ventricular systolic function. A Swan-Ganz catheter revealed PA pressures of >80/40 mmHg (table in Fig. 11). The wedge pressure could not be obtained due to patient size. A VQ scan was low probability for pulmonary emboli (Fig. 11D and E). His CT angiogram showed moderate to severe cardiomegaly with evidence of elevated right heart pressures and normal lung parenchyma other than mild dependent hypoventilation (Fig. 11F–H). The patient, however, did exhibit daytime hypoxemia and hypercapnia on room air as evidenced by an arterial blood gas, which showed pH 7.35, PaCO2 49 mmHg, PaO270 mmHg, and SaO2 93%. Given the patient's extreme obesity and evidence of daytime alveolar hypoventilation, his case is consistent with obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS) causing cor pulmonale. With diuresis, ultrafiltration and nocturnal positive airway pressure his PH was reduced and he lost >65 lbs of fluid over 25 days (Fig. 11I).

In classic “Pickwickian” syndrome,[32] an early description of what is now characterized as OHS, overall daytime hypoventilation related to markedly restricted lung volumes is coupled with significant nocturnal hypoxemia and episodes of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Episodic and eventually chronic hypoxia induces vasoconstriction of the small pulmonary arteries, leading to transient but repetitive elevations of PAP and RVH.[33]

Imaging lesson

Imaging (and RHC) in obese patients is challenging. Elevations in PAP from obesity, OHS, and respiratory disease are typically milder than in other forms of PH;[34] however the chamber dilation and volume overload that ensues can be dramatic, as in this case. In addition, patients often have risk factors for PH that ultimately contribute to their PH syndrome. This patient did have portal hypertension; however, his PH decreased substantially with CPAP, suggesting sleep apnea was the predominant cause.

CATEGORY 4 PH

Category 4 PH: Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension

This 50-year-old male presented to an outside hospital with exertional dyspnea, and was referred to our institution for further evaluation of PH. He has a history of chronic liver disease secondary to hepatitis C infection and chronic obstructive lung disease. His ECG showed right axis deviation and an S1Q3T3 pattern (Fig. 12A). His chest X-ray showed an enlarged RV, a severely dilated main pulmonary artery, and dilated bilateral pulmonary arteries, consistent with long-standing PH (Fig. 12B and C). Echocardiogram showed severe RV dilatation and dysfunction and a flattened interventricular septum, consistent with RV volume and pressure overload. RHC (table in Fig. 12) revealed severely elevated PAP. Pulmonary function testing was consistent with severe obstructive lung disease with a FEV1/FVC ratio of 49%, total lung capacity of 105%, residual volume of 162% and a DLCO of 21.26 ml/min/mmHg (72% predicted). Although he had risk factors for Category 1 and 3 PH (i.e., chronic liver disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), adherence to the recommended diagnostic algorithm[35] led to a VQ scan that showed small unmatched perfusion defect in the left lower lobe (Fig. 12D and E). Subsequently, a CT pulmonary angiogram showed a filling defect in the right main pulmonary artery and the right middle lobe branch suggestive of pulmonary embolism (Fig. 12F–H). The thrombus in the right main PA had recanalized, evident from the contrast within the thrombus and the absence of right-sided perfusion defect on the VQ scan. The CT scan also confirmed the massive enlargement of the pulmonary arteries. The patient was started on warfarin and sildenafil. Although pulmonary endarterectomy (PEA) represents a definitive cure of CTEPH,[8] this patient was not referred for PEA due to his other significant co-morbidities (liver disease and thrombocytopenia).

Imaging lesson

This case demonstrates the complementary role of CT pulmonary angiography and VQ scans in detecting CTEPH (both modalities being fallible).

CATEGORY 5 PH

Category 5 PH: PH due to extrinsic PA obstruction

A 29-year-old male who was recently diagnosed with testicular cancer was referred for a radical orchiectomy and abdominal lymph node dissection. On post-operative day 1, he developed sudden dyspnea and hypoxemia. ECG and chest X-ray were unremarkable (Fig. 13A–E). Echocardiography showed normal left ventricular function with moderately dilated and reduced RV function. Pulmonary artery systolic pressure was estimated at 40 mmHg+RA pressure. A CT pulmonary angiogram revealed a calcified mediastinal mass compressing the right main PA (Fig. 13D and E). There was a filling defect adherent to the vessel wall extending from the right main PA to the right lower lobe PA suggestive of a thrombus (Fig. 13E and F). The VQ scan showed normal ventilation in both lungs (Fig. 13G) with absence of perfusion in the right lung, consistent with right PA compression (Fig. 13H).

Figure 14 shows the case of a 54-year-old male with non-small cell lung cancer. He presented to a clinic with worsening dyspnea and cough. Chest X-ray showed pleural effusion (Fig. 14B and C). CT scan showed extensive confluent mediastinal and bihilar lymphadenopathy, compressing both pulmonary arteries and involving the pericardium (Fig. 14D and E). Obstruction to RV outflow was visualized on the echocardiogram as flow acceleration detected by color- and pulsed-wave Doppler (Fig. 14F and G).

Imaging lesson

CT scan and MRI are the usual modes of imaging by which Category 5 PH is detected. Extrinsic compression of the PA can obstruct flow, causing RV hypertension. However, if the obstruction is proximal (as in these cases) it is probable that there will be no PH and that PVR will be normal.

CONCLUSIONS

These cases offer representative examples of each category of PH in the WHO classification.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the family of Mr. Ernie Nafpliotis, who supported our PH research with a generous donation, and to Dr. Mardi Gomberg-Maitland for providing access to patient images in Figure 3.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, Barst RJ, Farber HW, Lindner JR, et al. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association: Developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, Inc., and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. Circulation. 2009;119:2250–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simonneau G, Robbins IM, Beghetti M, Channick RN, Delcroix M, Denton CP, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:S43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rich JD, Shah SJ, Swamy RS, Kamp A, Rich S. Inaccuracy of Doppler echocardiographic estimates of pulmonary artery pressures in patients with pulmonary hypertension: Implications for clinical practice. Chest. 2011;139:988–93. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Califf RM, Adams KF, McKenna WJ, Gheorghiade M, Uretsky BF, McNulty SE, et al. A randomized controlled trial of epoprostenol therapy for severe congestive heart failure: The Flolan International Randomized Survival Trial (FIRST) Am Heart J. 1997;134:44–54. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(97)70105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rietema H, Holverda S, Bogaard HJ, Marcus JT, Smit HJ, Westerhof N, et al. Sildenafil treatment in COPD does not affect stroke volume or exercise capacity. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:759–64. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00114207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thenappan T, Shah SJ, Gomberg-Maitland M, Collander B, Vallakati A, Shroff P, et al. Clinical characteristics of pulmonary hypertension in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:257–65. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.958801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elwing J, Panos RJ. Pulmonary hypertension associated with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2008;3:55–70. doi: 10.2147/copd.s1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryan JJ, Rich S, Archer SL. Pulmonary Endarterectomy Surgery-A Technically Demanding Cure for WHO Group IV Pulmonary Hypertension: Requirements for Centres of Excellence and Availability in Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27:671–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thistlethwaite PA, Mo M, Madani MM, Deutsch R, Blanchard D, Kapelanski DP, et al. Operative classification of thromboembolic disease determines outcome after pulmonary endarterectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;124:1203–11. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.127313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Naamani K, Hijal T, Nguyen V, Andrew S, Nguyen T, Huynh T. Predictive values of the electrocardiogram in diagnosing pulmonary hypertension. Int J Cardiol. 2008;127:214–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Satoh T, Kyotani S, Okano Y, Nakanishi N, Kunieda T. Descriptive patterns of severe chronic pulmonary hypertension by chest radiography. Respir Med. 2005;99:329–36. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isobe M, Yazaki Y, Takaku F, Koizumi K, Hara K, Tsuneyoshi H, et al. Prediction of pulmonary arterial pressure in adults by pulsed Doppler echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 1986;57:316–21. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90911-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitabatake A, Inoue M, Asao M, Masuyama T, Tanouchi J, Morita T, et al. Noninvasive evaluation of pulmonary hypertension by a pulsed Doppler technique. Circulation. 1983;68:302–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.68.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urboniene D, Haber I, Fang YH, Thenappan T, Archer SL. Validation of high-resolution echocardiography and magnetic resonance imaging vs.high-fidelity catheterization in experimental pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;299:L401–12. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00114.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alunni JP, Degano B, Arnaud C, Tétu L, Blot-Soulétie N, Didier A, et al. Cardiac MRI in pulmonary artery hypertension: Correlations between morphological and functional parameters and invasive measurements. Eur Radiol. 2010;20:1149–59. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1664-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freed B, Gomberg-Maitland M, Chandra S, Mor-Avi V, Rich S, Archer SL, et al. Late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance predicts clinical worsening in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2012;14:11. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-14-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grothues F, Moon JC, Bellenger NG, Smith GS, Klein HU, Pennell DJ. Interstudy reproducibility of right ventricular volumes, function, and mass with cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Am Heart J. 2004;147:218–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinberg I. Calcification of the pulmonary artery and enlargement of the right ventricle: A sign of congenital heart disease. Eisenmenger syndrome--pulmonary hypertension, increased pulmonary resistance, and reversal of blood flow. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1966;98:369–77. doi: 10.2214/ajr.98.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasad K, Radhakrishnan S, Sinha N. Extensive calcification of pulmonary arteries with left-to-right shunting across the arterial duct. Int J Cardiol. 1992;35:419–21. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(92)90245-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bloodworth J, Tomashefski JF., Jr Localised pulmonary metastatic calcification associated with pulmonary artery obstruction. Thorax. 1992;47:174–8. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.3.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kajita LJ, Martinez EE, Ambrose JA, Lemos PA, Esteves A, Nogueira da Gama M, et al. Extrinsic compression of the left main coronary artery by a dilated pulmonary artery: Clinical, angiographic, and hemodynamic determinants. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2001;52:49–54. doi: 10.1002/1522-726x(200101)52:1<49::aid-ccd1012>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rich S, McLaughlin VV, O’Neill W. Stenting to reverse left ventricular ischemia due to left main coronary artery compression in primary pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 2001;120:1412–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.4.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitsudo K, Fujino T, Matsunaga K, Doi O, Nishihara Y, Awa J, et al. [Coronary arteriographic findings in the patients with atrial septal defect and pulmonary hypertension (ASD + PH)–compression of left main coronary artery by pulmonary trunk] Kokyu To Junkan. 1989;37:649–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guazzi M, Vicenzi M, Arena R, Guazzi MD. Pulmonary hypertension in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A target of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibition in a 1-year study. Circulation. 2011;124:164–74. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.983866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Humbert M, Maitre S, Capron F, Rain B, Musset D, Simonneau G. Pulmonary edema complicating continuous intravenous prostacyclin in pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1681–5. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9708065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frazier AA, Franks TJ, Mohammed TL, Ozbudak IH, Galvin JR. From the Archives of the AFIP: Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease and pulmonary capillary hemangiomatosis. Radiographics. 2007;27:867–82. doi: 10.1148/rg.273065194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirk P, Roughton M, Porter JB, Walker JM, Tanner MA, Patel J, et al. Cardiac T2* magnetic resonance for prediction of cardiac complications in thalassemia major. Circulation. 2009;120:1961–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.874487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wood JC, Tyszka JM, Carson S, Nelson MD, Coates TD. Myocardial iron loading in transfusion-dependent thalassemia and sickle cell disease. Blood. 2004;103:1934–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davis BA, Porter JB. Long-term outcome of continuous 24-hour deferoxamine infusion via indwelling intravenous catheters in high-risk beta-thalassemia. Blood. 2000;95:1229–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parent F, Bachir D, Inamo J, Lionnet F, Driss F, Loko G, et al. A hemodynamic study of pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:44–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gladwin MT, Sachdev V, Jison ML, Shizukuda Y, Plehn JF, Minter K, et al. Pulmonary hypertension as a risk factor for death in patients with sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:886–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dickens C. The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. London: Chapman & Hall; 1837. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guidry UC, Mendes LA, Evans JC, Levy D, O’Connor GT, Larson MG, et al. Echocardiographic features of the right heart in sleep-disordered breathing: The Framingham Heart Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:933–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.6.2001092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chaouat A, Bugnet AS, Kadaoui N, Schott R, Enache I, Ducoloné A, et al. Severe pulmonary hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:189–94. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200401-006OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLaughlin VV, McGoon MD. Pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2006;114:1417–31. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.503540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]