Abstract

Right ventricular (RV) failure is a key determinant of morbidity and mortality in pulmonary hypertension (PH). The present study aims to add to existing descriptions of RV structural and functional changes in PH through a comprehensive three-dimensional (3D) shape analysis. We performed 3D echocardiography on 53 subjects with PH and 19 normal subjects. Twenty short-axis slices from apex to tricuspid centroid were measured to characterize regional shape: apical angle, basal bulge, eccentricity, and area. Transverse shortening was assessed by fractional area change (FAC) in each short-axis slice, longitudinal contraction was assessed by tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) and global function by RV ejection fraction. Multivariate logistic analysis was used to compare the association of RV parameters with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class. Compared to normal, RV function in PH is characterized by decreased stroke volume index (SVi), fractional area change and ejection fraction. Increased eccentricity, apical rounding and bulging at the base characterize the shape of the RV in PH. Increased SVi, ejection fraction and mid-ventricular FAC were associated with less severe NYHA class in adjusted analyses. The RV in idiopathic PH (iPAH) was observed to have a larger end-diastolic volume and decreased function compared with connective tissue disease associated PH (ctd-PH). This work describes increased eccentricity and decreased systolic function in subjects with PH. Functional parameters were associated with NYHA class and heterogeneity in the phenotype was noted between subjects with iPAH and ctd-PH.

Keywords: pulmonary hypertension, right ventricle, 3D echocardiography

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is defined by increased pulmonary vascular resistance and elevated pulmonary arterial pressure. Research focused on the vascular biology of PH has identified several therapeutic targets and progress has been made in treating the disease. Despite these significant advances, PH continues to have a high mortality and morbidity.[1]

Morbidity and mortality in PH are strongly related to right ventricular (RV) failure.[2] Characterization of the structure and function of the RV in a clinical population is limited by its complex shape, which poses an inherent challenge to traditional two-dimensional imaging modalities.[3] With the growing availability of three-dimensional (3D) techniques such as magnetic-resonance imaging and 3D echocardiography, assessment of structural and functional changes in the stressed RV is now becoming feasible.[4–8] Three-dimensional modalities offer superior accuracy and reproducibility in the assessment of RV shape and function.[3,9,10]

With more accessible and reliable summary measures, including RV end-diastolic volume and ejection fraction, determinants of RV function are being investigated in large cohorts.[11–13] Comprehensive shape analyses are typically smaller in scale; however, they add granularity to the interpretation of summary measures in large cohort studies[14] and can suggest mechanistic paradigms.[15] To date, a comprehensive shape analysis of the RV in PH using 3D echocardiography has not been performed, although individual shape parameters have been associated with prognosis.[6]

In this analysis we perform a comprehensive shape analysis. We hypothesize that the RV in PH has a unique phenotype compared to the RV in normal subjects; furthermore, we suspect that parameters of function instead of shape will associate with symptom severity. Secondarily, we hypothesize that heterogeneity in RV phenotype exists between iPAH and ctd-PH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient population

This study includes 72 subjects: 58 with PH and 19 normal; 5 PH subjects were excluded for uninterpretable echocardiograms for a final study sample of 53 PH subjects. PH subjects were a convenience sample of volunteers at the 8th and 9th International Pulmonary Hypertension Conferences. PH subjects provided basic survey data with additional survey elements including NYHA class collected only during the second enrollment. Normal subjects were healthy volunteers with no history of heart or lung disease, abnormal electrocardiogram or echocardiogram. The Human Subjects Review Committee of the University of Washington (#27609) and Washington State Institutional Review Board (#20081178) approved the study and all subjects provided informed consent.

Image acquisition

Imaging was performed using standard echocardiography equipment (Terason 3000, Teratech, Burlington, MA, or Acuson Sequoia, Oceanside, Calif.). A magnetic field tracking system (Flock of Birds, Ascension Technology Corp., Burlington, Vt.) continuously registered the spatial position and orientation of the echo probe. Each subject was imaged in the left lateral decubitus position at held end expiration on a nonferrous bed with a deep apical cutout. The RV, LV, and all four cardiac valves were imaged from standard echocardiographic windows (left parasternal, apical, subcostal). Further images were taken from the suprasternal, high left parasternal, and right parasternal windows when necessary to obtain optimal visualization of the pulmonic valve, infundibulum, and RV free wall.

Image analysis for 3D RV reconstruction

Each two-dimensional echo cine loop was visually examined to assess end-diastole and end-systole. End-diastole was identified as the onset of the QRS complex. If QRS onset was ambiguous, the frame with the larger ventricular area was identified as end-diastole. The end-systolic frame was identified as the frame with smallest RV area immediately prior to pulmonic valve or aortic valve closure for each clip.

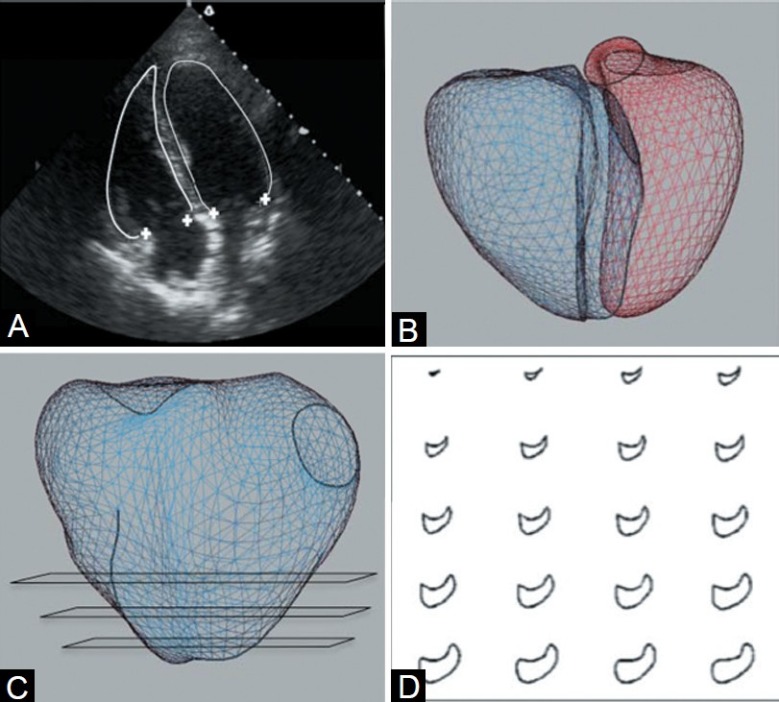

Using custom software, the borders of the ventricles, valve orifices, and other anatomic landmarks were manually traced. Endocardial borders were fit to spline curves and landmarks were converted to 3D coordinates using the magnetic tracking system. Papillary muscles and trabeculae were included in chamber volumes to obtain smooth endocardial contours suitable for shape analysis. The tricuspid and mitral annuli were reconstructed as Fourier series approximations to traced points. Circles fit to traced points approximated the semilunar valves. The RV and LV were reconstructed using the piecewise smooth subdivision surface method (Fig. 1). This provides anatomically accurate representations of the 3D contours of the ventricle.[16] RV volume was computed as the sum of signed tetrahedral volumes formed by connecting a point in space with each triangular surface face. RV volume measurements were normalized to the body surface area.

Figure 1.

3D reconstruction and regional shape analysis methods: Manual tracing of the endocardial borders and valve points on 2D echocardiogram (A), use of magnetic tracking to assign each trace a position in 3D space with mesh fit (B) and construction of 20 short axis slices from apex to base to analyze regional shape and function (C, D).

All tracing was performed blinded to patient characteristics. Clinical characteristics were only available during the analysis portion of the study at which point no changes were made to 3D cardiac reconstructions.

Interobserver variability

Using the methods described above, two observers traced the RV endocardial surface in 10 subjects (5 normal and 5 with PH) for measurement of volume and EF. Variability of assessment used the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

Shape and regional function analysis

RV shape was analyzed at end-diastole to assess remodeling since end-systolic shape also reflects contractile function.[15,17] The LV long axis was drawn from the mitral centroid to the apex, defined as the most distant point on the LV. Twenty equidistant short-axis slices were constructed from the RV apex to the level of the tricuspid annulus centroid. For each short-axis slice, we measured area and perimeter, and calculated eccentricity as 4πarea/perimeter2, ranging from 1 (circle) to 0 (a line). Fractional area change was defined as the percentage decrease in area from end-diastole to end-systole. Short-axis area measurements were normalized by long-axis length.

Basal bulge (bulging of the free wall lateral to the tricuspid valve) was calculated as the distance along the RV-long axis between the tricuspid centroid and the most basal point on the RV free wall in the four-chamber plane. The apical angle was measured with divergent lines along the septum and RV free wall on an apical four-chamber image and averaged on two images.[18] TAPSE was measured as distance in the four-chamber plane between the lateral aspect of the tricuspid annulus at end-diastole and end-systole.[19]

Statistical analysis

Student's t-test was used for comparisons of global parameters of RV size, shape, and function. RV regional parameters measured at multiple slices within a single subject (short-axis normalized area, fractional area change, and eccentricity) were compared individually with a Student's t-test and between groups, incorporating the trend in all slices, with analysis of variance for repeated measures (ANOVA). Multivariate logistic regression of the odds of NYHA class III/IV versus I/II by parameters of RV structure and function adjusted for available survey elements hypothesized to confound the relationship (age, gender, race, and time since diagnosis of PH) was performed.

RESULTS

Patient population

Subjects with PH were older, more likely to be female and had a lower LV ejection fraction than normal subjects (Table 1). PH etiology was predominantly iPAH and ctd-PH. In the 39 PH patients collected during the second enrollment, the majority was white with a self-reported NYHA class II. Functional class was similar in the two major etiologies of PH represented (iPAH class II: 65%, ctd-PH class II: 70%); however, time since diagnosis was qualitatively though not statistically different (iPAH, 96 months vs. ctd-PH, 68 months; P=0.4). Over half of the patients were on two vasodilators and nearly a quarter were on three vasodilators. Six patients were on a single vasodilator and three patients were on no therapy for PH.

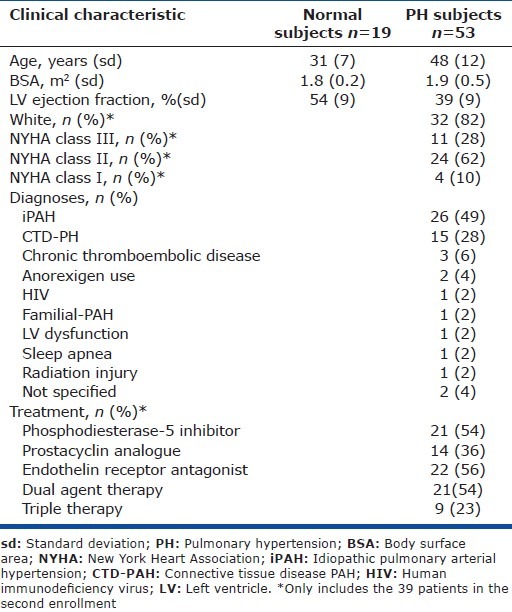

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and diagnoses of the cohort

RV shape and function in normal versus PH hearts

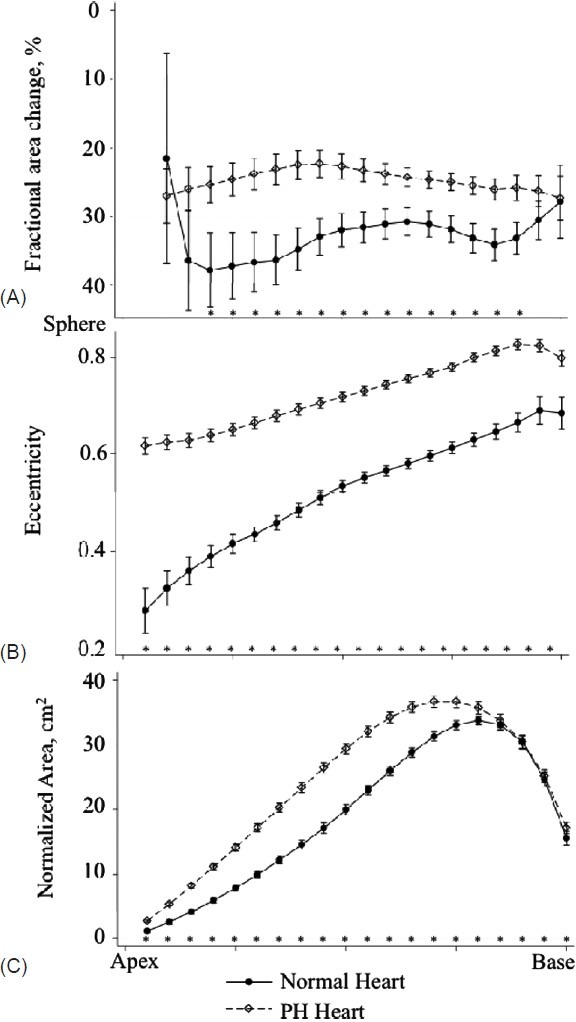

In PH, the RV had diminished global and regional function compared to normal. The RV in PH was noted to have decreased RVEF, TAPSE, stroke volume, and fractional area change in the basal and mid-ventricular segments (Table 2). The RV also had a unique shape in PH compared to normal characterized by increased eccentricity (roundness) in all ventricular segments and increased normalized area in the apex and mid-ventricular segments (Fig. 2). There was a significant basal bulge lateral to the tricuspid annulus and apical bulge (measured by apical angle) in PH hearts.

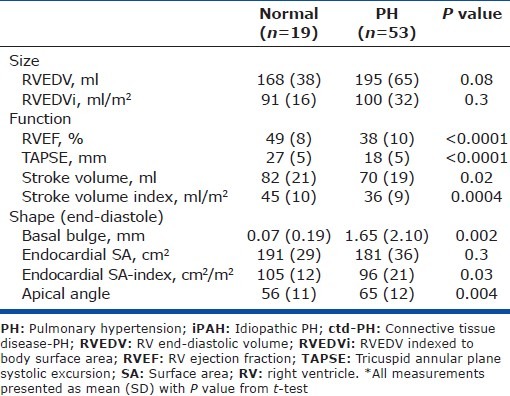

Table 2.

RV shape and function in normal and PH

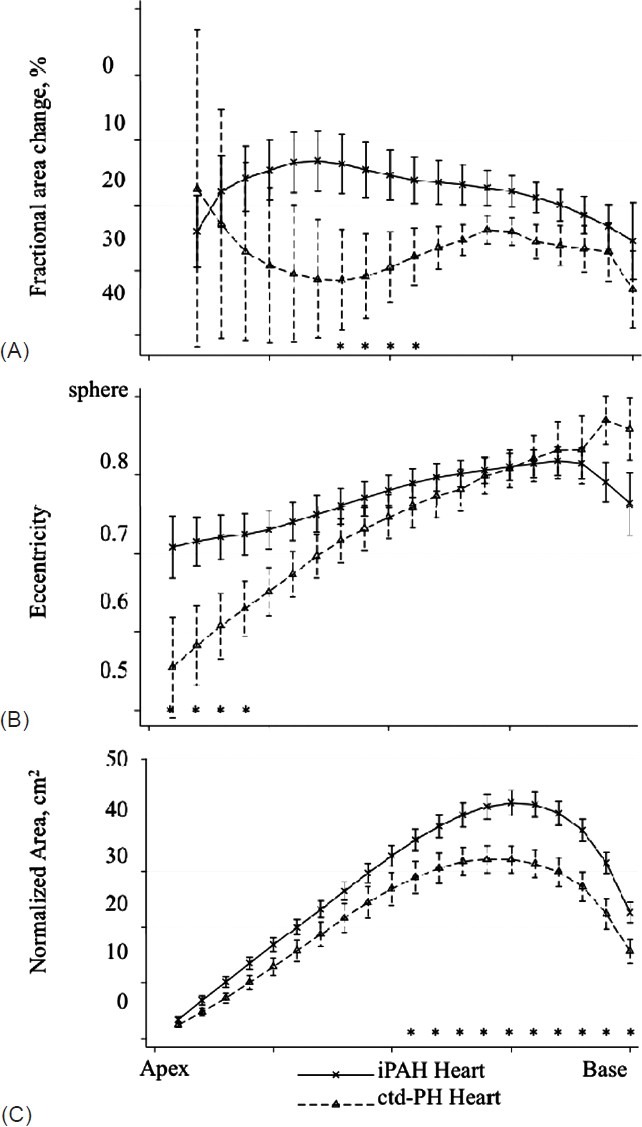

Figure 2.

Fractional area change (A), eccentricity (B) and normalized area (C) in 20 short-axis slices from apex to base in normal and PH hearts. Significant differences by t-test for individual slices are noted on the figure (*, P<0.05).

RV shape and function in iPAH versus ctd-PH hearts

The RV shape in iPAH differed from ctd-PH (Fig. 3), particularly at the basal segments where there were greater normalized areas and a tendency toward greater eccentricity (rounding) (Fig. 4). The RVEDV was greater in iPAH (218 mL vs. 178 mL, P=0.05) and there was an increased height of the basal bulge (2.45 mm vs. 0.70 mm, P=0.02). RV function in iPAH was also distinct from ctd-PH with decreased global and regional function as measured by RVEF (34% vs. 42%, P=0.01) and fractional area shortening at the mid-ventricular segments (Fig. 4). Stroke volume index was similar in the two groups (35 mL/m2 vs. 36 mL/m2).

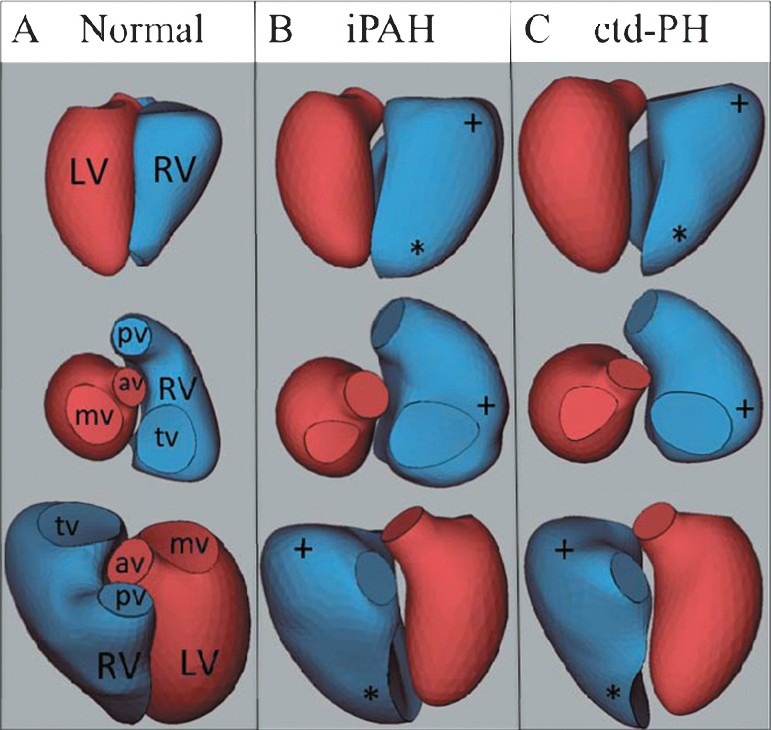

Figure 3.

Representative 3D reconstructions from a normal (A), iPAH (B) and ctd-PH (C) heart demonstrating apical rounding (*) and basal bulging (+), [LV: Left ventricle; RV: Right ventricle, pv: Pulmonary valve, av: Aortic valve; tv: Tricuspid valve; mv: Mitral valve].

Figure 4.

Fractional area change (A), eccentricity (B) and normalized area (C) in 20 short-axis slices from apex to base in the hearts of participants with iPAH or ctd-PH and TAPSE </= 18mm. Significant differences by t-test for individual slices are noted on the figure (*, P<0.05).

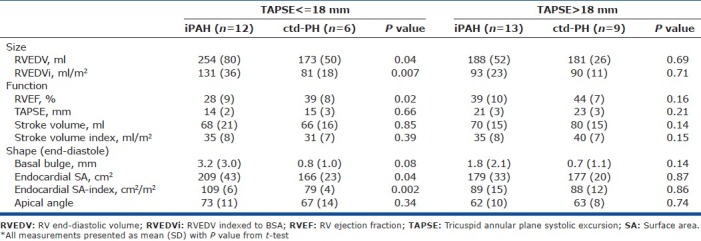

There was concern that these results were confounded by discrepant severity of illness and an exploratory analysis of subjects stratified by TAPSE was performed. There were no significant differences between the RV in iPAH and ctd-PH hearts in the “mild severity” group having TAPSE >18 mm. In hearts with TAPSE <18 mm, a distinct phenotype by etiology was observed that mirrored the observations seen in the “all iPAH vs. ctd-PH” comparison (Table 3).

Table 3.

RV shape and function in iPAH compared to ctd-PH, stratified by TAPSE

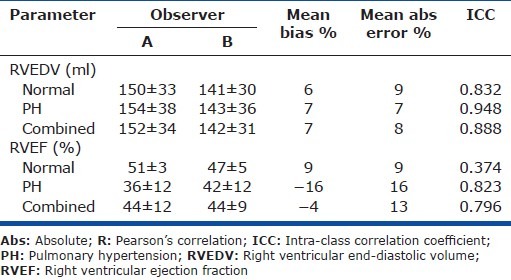

Interobserver variability

The ICCs were very good for volumes (0.83-0.95). The ICC for RVEF was good overall (0.80) though poor among normal subjects (0.37) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Inter-observer variability in RV volumes and EF

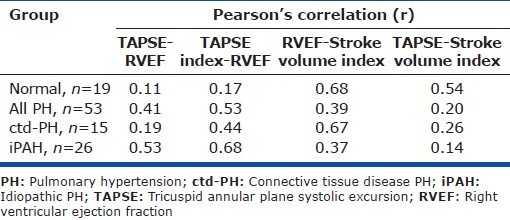

Correlation between echo metrics

There was modest correlation between TAPSE and RVEF in iPAH patients (r=0.53) and no correlation in normal patients or patients with ctd-PH (r=0.11 and 0.19). Index of TAPSE to RV long axis length improved correlation with RVEF in all groups but with a coefficient that remained <0.70. The relationship between RVEF and TAPSE in normal subjects was concordant despite the low correlation; all normal hearts had an RVEF >40% and TAPSE >20 mm (Table 5).

Table 5.

Correlation between echocardiographic measures of RV systolic function

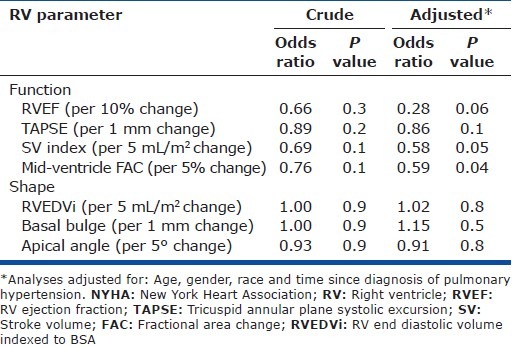

Odds ratio of worsened NYHA class by RV parameters of interest

None of the RV parameters of interest were associated with NYHA class in unadjusted analyses. After adjustment for age, race, gender and duration of PH, functional parameters including increased SVi and midventricular FAC were significantly associated with a reduced odds ratio of NYHA class III/IV. Increased RVEF trended toward association with improved NYHA class. Shape parameters, including RVEDVi, basal, and apical bulge were not suggestive of an association with NYHA class (Table 6).

Table 6.

Logistic regression of the odds ratio of NYHA class III/IV versus I/II per unit change of selected RV parameters

DISCUSSION

In this analysis, we identified an RV shape common to PH and characterized by increased eccentricity, basal, and apical bulging. Changes in shape did not appear to be associated with symptoms as assessed by NYHA class; however, changes in cardiac function were associated with subjects’ self-reported symptoms. While the RV shape was similar between ctd-PH and iPAH, we also demonstrated heterogeneity along etiologic lines.

In PH, the RV is more spherical with increased cross sectional area at the mid and basal ventricular segments, basal bulging adjacent to the tricuspid valve and blunting of the apex. This description reinforces previous observations including blunting of the apical angle[18] and changes in eccentricity.[20–22] We are not aware of previous investigations reporting basal bulging adjacent to the tricuspid valve in PH.

While the RV in PH shared more similarities than differences between etiologies, we did observe variation in the phenotype between iPAH and ctd-PH. In iPAH, the RV had an increased volume and decreased RVEF. As has been previously reported, the greatest dilation was associated with the lowest RVEF.[6] Conversely in ctd-PH, the RV appeared to have a decreased surface area, unchanged volume and “normal” RVEF with little dilation occurring at low RVEF. These differences in RV shape and function between iPAH and ctd-PH contrasted with the similarity in clinical parameters suggested by equivalent stroke volume and functional class.

While stroke volume and NYHA class are accepted markers of severity in PH,[4,23] we questioned whether the observed differences were due to severity rather than etiology. We chose to stratify by TAPSE as a surrogate for severity. TAPSE is a validated marker of severity and prognosis in PH in both PH at large and scleroderma associated PH.[24,25] We used a “cut-off” value identified as most strongly predictive of mortality by Forfia et al. (18 mm).[24] In subjects with TAPSE >18 mm, there was little difference between the RV in ctd-PH and iPAH. In contrast, subjects with TAPSE <18 mm defined the subgroup phenotypes. Among these severely affected individuals, the RV in iPAH had increased volume, decreased function and a similar stroke volume index when compared to ctd-PH. Generalization of this finding of heterogeneity more broadly to iPAH and ctd-PH must be quite cautious due to the small population size, lack of corroborative clinical data and qualitative differences in duration of PH by group; however, these findings do agree with Chung et al. who, using a PH registry, describe less systolic dysfunction and a tendency toward smaller RV volumes despite increased mortality in ctd-PH compared to iPAH.[26]

Taken together, we believe these finding should raise concern about the tendency homogenize findings in the right ventricle within World Health Organization (WHO) PH groups. WHO group I combines diseases with similar pulmonary vascular characteristics and it is not established that RV characteristics are likewise similar. Studies such as those done by Kawut et al, which demonstrate an association between RVEF and mortality, were performed in cohorts limited to familial and iPAH patients; therefore, further study of the RV in other etiologies of PH may be necessary to determine if analogous relationships exist and determine appropriate reference values. If validated in further study, the heterogeneity of RV function by etiology of PH may present a unique opportunity to look at a natural experiment of the necessary cofactors in the development of RV failure.

The results of our study join others suggesting correlation between TAPSE and RVEF is limited.[29,30] We indexed TAPSE to RV long axis length to account for differences in RV size in longitudinal shortening, which improved the RVEF to TAPSE correlation in all groups. Standardly used TAPSE, however, is a validated prognostic tool[25] and may predict outcome independently of surrogacy for RVEF. Future validation against outcome data is therefore needed to establish any clinical value of TAPSE normalization.

Finally, the current analysis suggests an association between parameters of RV function but not shape and severe NYHA class. The evidence supporting an association between functional parameters and symptoms is currently contradictory and this report adds to that understanding.[26,31] The association between shape and symptoms is unreported and similarly was not observed in our cohort.

Limitations

PH subjects were an ambulatory, cross-sectional sample at two national meetings. This could represent a unique group with mild disease and poor generalizability; however, inclusion of patients who were uncharacteristically healthy would be expected to bias the results toward the null and should not diminish the strength of observed associations. In addition, the present study is analytical and detailed clinical information including hemodynamic data was not collected a priori and is not available. This may limit the direct clinical applicability and generalizability of our findings.

In summary, this work describes increased eccentricity and decreased function in PH. Furthermore, parameters of function appear to be associated with NYHA class. Finally, heterogeneity in RV parameters between iPAH and ctd-PH was observed. These results further the description of the stressed RV through a comprehensive shape analysis in PH subjects and join other reports that suggest caution in the homogenization of RV findings even among diseases of the same World Health Organization PH group.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This work was supported by an NIH training grant [5T32HL007287-32]. Raw echocardiographic images were acquired by Ventripoint, Inc. and given as an unrestricted gift to Peter Leary for 3D reconstruction and analysis.

Conflict of Interest: PJL, CEK, CLH and DDR report no conflicts of interest. FHS is a scientific and technical consultant for Ventripoint, Inc. (markets an alternative method of 3D echocardiographic reconstruction). MPW is an employee of Ventripoint, Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gomberg-Maitland M, Dufton C, Oudiz RJ, Benza RL. Compelling Evidence of Long-Term Outcomes in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1053–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Alonzo GE, Barst RJ, Ayres SM, Bergofsky EH, Brundage BH, Detre KM, et al. Survival in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension.Results from a national prospective registry. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115:343–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-5-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheehan F, Redington A. The right ventricle: Anatomy, physiology and clinical imaging. Heart. 2008;94:1510–5. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.132779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Wolferen SA, van de Veerdonk MC, Mauritz GJ, Jacobs W, Marcus JT, Marques KMJ, et al. Clinically Significant Change in Stroke Volume in Pulmonary Hypertension. Chest. 2011;139:1003–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Wolferen SA, Marcus JT, Boonstra A, Marques KM, Bronzwaer JG, Spreeuwenberg MD, et al. Prognostic value of right ventricular mass, volume, and function in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1250–7. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mauritz GJ, Kind T, Marcus JT, Bogaard HJ, van de Veerdonk M, Postmus PE, et al. Progressive Changes in Right Ventricular Geometric Shortening and Long-term Survival in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Chest. 2011 Sep 29; doi: 10.1378/chest.10-3277. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Overbeek MJ, Lankhaar JW, Westerhof N, Voskuyl AE, Boonstra A, Bronzwaer JGF, et al. Right ventricular contractility in systemic sclerosis-associated and idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:1160–6. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00135407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghio S, Pazzano AS, Klersy C, Scelsi L, Raineri C, Camporotondo R, et al. Clinical and Prognostic Relevance of Echocardiographic Evaluation of Right Ventricular Geometry in Patients With Idiopathic Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:628–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amaki M, Nakatani S, Kanzaki H, Kyotani S, Nakanishi N, Shigemasa C, et al. Usefulness of three-dimensional echocardiography in assessing right ventricular function in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2009;32:419–22. doi: 10.1038/hr.2009.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jenkins C, Leano R, Chan J, Marwick TH. Reconstructed versus real-time 3-dimensional echocardiography: Comparison with magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2007;20:862–8. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawut SM, Lima JA, Barr RG, Chahal H, Jain A, Tandri H, et al. Sex and Race Differences in Right Ventricular Structure and Function: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis-Right Ventricle Study. Circulation. 2011;123:2542–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.985515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawut S, Barr R, Lima J, Johnson C, Kizer J, Tandri H, et al. Right Ventricular Morphology and Function and Long-Term Outcomes: The MESA-Right Ventricle Study. Am Thorac Soc Abstract. 2011;183:A4991. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawut SM, Barr RG, Johnson WC, Chahal H, Tandri H, Jain A, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 are associated with right ventricular structure and function: The MESA-RV Study. Biomarkers. 2010;15:731–8. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2010.516455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salgo IS, Tsang W, Ackerman W, Ahmad H, Chandra S, Cardinale M, et al. Geometric Assessment of Regional Left Ventricular Remodeling by Three-Dimensional Echocardiographic Shape Analysis Correlates with Left Ventricular Function. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2012;25:80–8. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2011.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheehan FH, Ge S, Vick GW, Urnes K, Kerwin WS, Bolson EL, et al. Three-dimensional shape analysis of right ventricular remodeling in repaired tetralogy of Fallot. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:107–13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.07.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hubka M, Bolson EL, McDonald JA, Martin RW, Munt B, Sheehan FH. Three-dimensional echocardiographic measurement of left and right ventricular mass and volume: In vitro validation. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2002;18:111–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1014616603301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mancini GJ, DeBoe SF, Anselmo E, Simon SB, LeFree MT, Vogel RA. Quantitative regional curvature analysis: An application of shape determination for the assessment of segmental left ventricular function in man. Am Heart J. 1987;113:326–34. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90273-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.López-Candales A, Dohi K, Iliescu A, Peterson RC, Edelman K, Bazaz R. An abnormal right ventricular apical angle is indicative of global right ventricular impairment. Echocardiography. 2006;23:361–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2006.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morcos P, Vick GW, III, Sahn DJ, Jerosch-Herold M, Shurman A, Sheehan FH. Correlation of right ventricular ejection fraction and tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion in tetralogy of Fallot by magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;25:263–70. doi: 10.1007/s10554-008-9387-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.López-Candales A, Bazaz R, Edelman K, Gulyasy B. Apical Systolic Eccentricity Index: A Better Marker of Right Ventricular Compromise in Pulmonary Hypertension. Echocardiography. 2010;27:534–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2009.01045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.López-Candales A, Rajagopalan N, Kochar M, Gulyasy B, Edelman K. Systolic eccentricity index identifies right ventricular dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension. Int J Cardiol. 2008;129:424–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghio S, Klersy C, Magrini G, D’Armini AM, Scelsi L, Raineri C, et al. Prognostic relevance of the echocardiographic assessment of right ventricular function in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int J Cardiol. 2010;140:272–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sitbon O, Humbert M, Nunes H, Parent F, Garcia G, Hervé P, et al. Long-term intravenous epoprostenol infusion in primary pulmonary hypertension: Prognostic factors and survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:780–8. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forfia PR, Fisher MR, Mathai SC, Housten-Harris T, Hemnes AR, Borlaug BA, et al. Tricuspid annular displacement predicts survival in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:1034–41. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-547OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mathai SC, Sibley CT, Forfia PR, Mudd JO, Fisher MR, Tedford RJ, et al. Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion Is a Robust Outcome Measure in Systemic Sclerosis-associated Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:2410–8. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung L, Liu J, Parsons L, Hassoun PM, McGoon M, Badesch DB, et al. Characterization of Connective Tissue Disease-Associated Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension From REVEAL: Identifying Systemic Sclerosis as a Unique Phenotype. Chest. 2010;138:1383–94. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simonneau G, Robbins IM, Beghetti M, Channick RN, Delcroix M, Denton CP, et al. Updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(1 Suppl):S43–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawut SM, Horn EM, Berekashvili KK, Garofano RP, Goldsmith RL, Widlitz AC, et al. New predictors of outcome in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kjaergaard J, Petersen CL, Kjaer A, Schaadt BK, Oh JK, Hassager C. Evaluation of right ventricular volume and function by 2D and 3D echocardiography compared to MRI. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2006;7:430–8. doi: 10.1016/j.euje.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaul S, Tei C, Hopkins JM, Shah PM. Assessment of right ventricular function using two-dimensional echocardiography. Am Heart J. 1984;107:526–31. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(84)90095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nath J, Demarco T, Hourigan L, Heidenreich PA, Foster E. Correlation between right ventricular indices and clinical improvement in epoprostenol treated pulmonary hypertension patients. Echocardiography. 2005;22:374–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2005.04022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]