Abstract

This article provides a brief review of the history and origins of the Journal of Chiropractic Humanities. The reason for starting the journal, its purpose, and a timeline from 1991 to 2009 are offered.

During the birth of most new journals, hopes are high but the future is uncertain. Success of a peer-reviewed journal requires many factors. Interest and support from the readers, funding for publication, authors submitting meaningful articles, a willing publishing company, indexing systems to include the journal, and an infrastructure to provide the editorial and peer-review process are all necessary to ensure a journal’s success.

In the early years of chiropractic, the call for scholarly publication, more legitimate scientific research, and intellectual honesty had been demanded by a few outspoken members of the profession. However, little was done in the first several chiropractic decades. Watkins criticized chiropractic leaders for their misuse and misunderstanding of the term philosophy. Instead of true philosophy they were actually promoting dogma. In 1944, Watkins stated, “Many of the old ‘philosophical’ leaders feel that chiropractic is doomed to failure as a ‘healing movement’ because in their opinion the average chiropractor has ‘lost the faith’ and no longer fervently propounds the doctrine, that he has wandered astray in his therapy, and that he has not kept chiropractic pure so that it may be preserved for posterity. In other words the ‘philosophical’ leaders regard chiropractic as being based upon doctrine rather than upon science.”1 Keating et al suggested that those in the chiropractic profession looked to medicine’s cultural success due to its scientific base as a motivator for becoming more scientific.2 The authors found that although the terms research and science were used in chiropractic publications, these terms were often applied to marketing strategies and only rarely used correctly. Though there seemed to be a desire for legitimate research and philosophical discussion, little evidence for these were found in the first half of the chiropractic century.

Demand for more chiropractic science, research, and publication grew. Between 1970 and 1990, there was an increased interest in creating new scientific and scholarly journals for the chiropractic profession. Some in the profession recognized a need for chiropractic to legitimize itself with research but few had the training to make this happen. Fledgling journals were created on a variety of topics, even though there was little to no track record in publication for many of these journal editors and journal owners. One may wonder if some of the new publications were created as attempts to develop a scientific image despite few scholarly activities. Although some publications may have followed this path, one of these journals eventually became indexed in Medline (ie, Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics), and other journals were indexed in other indexing systems. This implies that some of these journals were tenacious, contained quality content, and maintained a peer-review process.

Not all journals created during this time survived. In the years prior to 1991, several chiropractic journals failed, and other journals that were in existence during 1991 shut down in the following years (Table 1). In the decade that followed, other journals that provided a much needed venue for publication and generated interest from readers also disappeared (Table 2). It is likely that there were many factors involved in the demise of these journals, such as a lack of financial support through sponsors and subscribers. As well, there may have been a lack of high-quality submissions that would be able to withstand the rigors of legitimate peer review. Without high-quality papers being submitted to the journals, inclusion in upper-level indexing systems would be unlikely. It was in this environment that the journal that would become the Journal of Chiropractic Humanities was born. Knowing this was such a tumultuous time, one would wonder why a journal focusing on philosophy and humanities would be created.

Table 1.

Examples of journals that began before 1991

| Journal Title | Last Year of Publication According to the Index to Chiropractic Literature |

|---|---|

| Chiropractic Australia | 1988 |

| Annals of the Swiss Chiropractic Association | 1989 |

| American Journal of Chiropractic Medicine | 1990 |

| Chiropractic Technique | 1999 |

| Journal of Sports Chiropractic and Rehabilitation | 2001 |

| Chiropractic Research Journal | 2000 |

| European Journal of Chiropractic | 2003 |

Table 2.

Examples of journals that began after 1991

| Journal Title | Last Year of Publication According to the Index to Chiropractic Literature |

|---|---|

| Chiropractic Pediatrics | 1998 |

| Journal of the Neuromusculoskeletal System | 2001 |

| Topics in Clinical Chiropractic | 2002 |

Up until 1991, there were no peer-reviewed journals dedicated to the publication of the philosophical constructs of the chiropractic profession. Some articles or books had been published on “philosophy,” but no journal was solely dedicated to these discussions. Most conversations about “philosophy” were not necessarily about philosophy in the classic sense but instead seemed to be dogmatic soliloquies aimed at selling a brand of practice management under the guise of legitimate philosophy. At the time, there were few journals where a chiropractic-focused manuscript could be submitted to undergo the scrutiny of peer review and be published in an indexed journal. If the chiropractic profession was to evolve, a legitimate publication needed to be created to record and catalog these discussions.

Dr. James Winterstein, President of what then was known as the National College of Chiropractic (NCC) (now the National University of Health Sciences; NUHS), first introduced discussions of this journal with Mr. Jack Groves (Vice President for NCC Business Affairs), Dr. Jacob Fisher (NCC Chancellor) and Orval Hidde (Chair of the NCC Board). At a special meeting held in Dr. Hidde’s office in Watertown, Wisconsin in 1990, Dr. Winterstein stated, “Gentlemen, we have been publishing a scientific journal, the JMPT, since 1978 but it does not meet the needs of the profession in some areas. I am proposing two new journals—one dealing with what chiropractors call “chiropractic philosophy” and the other dealing with chiropractic manipulative techniques.” From this introduction, the JCH was born. The first issue of the journal was produced based on the papers presented at the 1991 NCC homecoming, an event organized by Winterstein. Each of the authors read his respective paper at this conference and subsequently served as a member of a discussion panel on the subject of “philosophical constructs.”

In 1991, the first edition of the journal, titled Philosophical Constructs for the Chiropractic Profession, was published.3 The journal’s goals started out small. In the back pages of volume 1, it states that the primary purpose of the journal was to “foster learned debate and interaction within the chiropractic profession regarding the uses of philosophical scholarship in advancing chiropractic tenets.” Using input and feedback from various scholars in the profession, such as Joe Keating Jr, Winterstein requested that the journal’s name be changed to the Journal of Chiropractic Humanities (JCH) in 1993. This change also helped to broaden the scope of the journal to include articles from other areas of the humanities such as ethics, sociology, and history. By broadening the scope of the journal, it better served the needs of the chiropractic profession. The mission of the JCH is “… to foster scholarly debate and interaction within the chiropractic profession regarding the humanities, which includes; history, philosophy, linguistics, literature, jurisprudence, ethics, theory, sociology, comparative religions, and aspects of social sciences that address historical or philosophical approaches.”

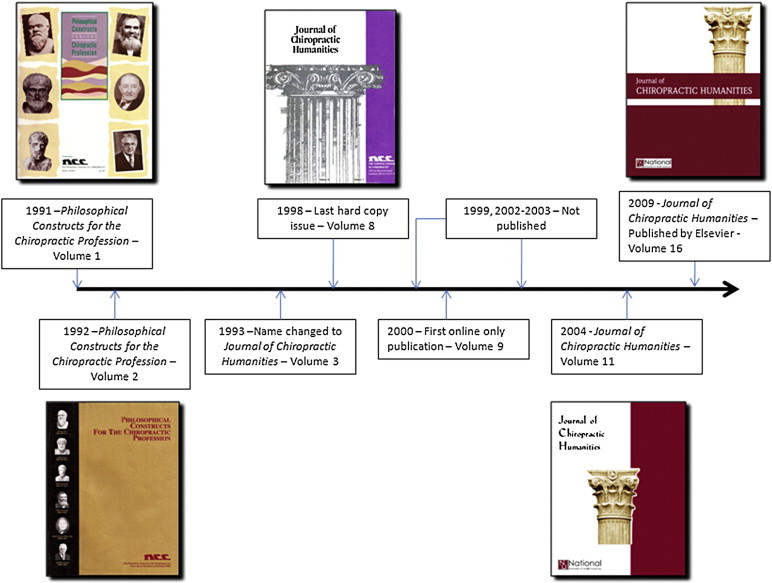

The first issues of the journal were successful, and complimentary copies of the printed journal (printing and mailing funded by NUHS) were sent to the majority of the chiropractic profession in the United States. Unfortunately in 1998, the JCH published its last hard copy issue and became an electronic-only journal beginning in 2000. As well, for some unknown reasons, the journal was not published for 3 years, 1999, 2002, and 2003 (Fig 1). This created several challenges to overcome when the NUHS transitioned to a new editorial team in 2004. Readers and authors were not pleased with a format that was electronic only. Based on the multiple e-mails and conversations about this topic, readers and authors not only wanted electronic access, they also wanted the print copy of the journal.

Fig 1.

Journal of Chiropractic Humanities timeline. (Color version of figure is available online.)

With the assistance and support of the current administration at NUHS, the JCH will now reach a broader readership. To further advance the JCH and the dialogue of chiropractic humanities, we are bringing back the option of the hard copy print journal with the 2009 issue. We are also happy to announce that Elsevier, a long-established publisher and friend to chiropractic, has become the publisher for the JCH. This is the first time that a professional publisher has contracted with this journal. Through this relationship, we now offer online submission and peer-review processes, electronic distribution, and a sought-after publication medium, the hard copy of the journal.

We will maintain the indexing systems that the JCH currently has gained over the past several years and will continue to seek out additional indexing systems. As with its 2 sister journals, the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics (JMPT) and the Journal of Chiropractic Medicine (JCM), the JCH will follow the standards and uniform requirements for manuscripts submitted to biomedical journals according to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

As the JCH moves beyond its 16th year, one may ask whether or not we still need a journal dedicated to humanities and philosophy. As Winterstein so aptly asked in the first issue of this journal, “Is traditional chiropractic philosophy valid today?”4 Winterstein urges us to consider that we base our answer upon what philosophy actually is as opposed to how the word has been misused by the profession in the past.5 This is certainly a valid argument for us to consider. As well, Coulter has helped to clarify what philosophy is and what it is not. He has pointed out that there are some within the chiropractic profession who do not understand and either intentionally or unintentionally misuse this term.6 Over the years, philosophy has developed a bad reputation in scientific circles both inside and outside the profession due to this misuse. When referring to these misuses from the past, Coulter states, “The real philosophy was held to be that peddled by the metaphysical merchants and which amounted to little more than practice-building motivational seminars—all given by persons who, to steal a line from Donahue, would not know a principle from a prince.”6 Though these are strong words, they seem to be accurate.

If we are to reach our full potential and have a better understanding of the profession, we should consider, study, and publish in all 3 branches of chiropractic; art, science, and philosophy. D.D. Palmer’s writings give us a direction as to how each of these concepts blend together in describing the whole. Palmer states, “Science refers to that which is to be known; art to that which is to be done; philosophy gives the reasons why of the method and the way in which it is to be performed.”7 It is time for our profession to evolve by correctly and consistently using and applying the terms art, science, and philosophy. However, we must also approach these topics in an intellectually rigorous manner with a good dose of critical appraisal skills and open minds. The creed of the NUHS, Esse Quam Videri, “To be, rather than to seem to be,” describes the essence of what we should be striving for. The JCH provides both authors and readers a place for this scholarly debate and dialogue to occur.

References

- 1.Watkins CO. National Institute of Chiropractic Research; Phoenix, AZ: 1992. The basic principles of chiropractic government. [reprint of 1944 edition] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keating JC, Jr, Green BN, Johnson CD. “Research" and “science" in the first half of the chiropractic century. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1995;18:357–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson C. Are reintroductions necessary? J Chiropr Humanit. 2004;11:1. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winterstein JF. Is traditional “chiropractic philosophy” valid today? Philos Constructs Chiropr Prof. 1991;1:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winterstein JF. Philosophical questions for the chiropractic profession. Philos Constructs Chiropr Prof. 1991;1:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coulter I. Uses and abuses of philosophy in chiropractic. Philos Constructs Chiropr Prof. 1991;2:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palmer DD. Mrs. D.D. Palmer; Los Angeles, CA: 1914. The chiropractor. [Google Scholar]