Abstract

The chiropractic profession struggled with survival and identity in its first decades. In addition to internal struggles between chiropractic leaders and colleges, much of our profession's formative years were stamped with reactions to persecution from external forces. The argument that chiropractic should be recognized as a distinct profession, and the rhetoric that this medicolegal strategy included, helped to develop chiropractic identity during this period of persecution in the early 20th century. This article questions if the chiropractic profession is mature and wise enough to be comfortable in being proud of its past but still capable of continued philosophical growth.

Key indexing terms: Chiropractic, History, Philosophy

Introduction

It was only 15 years ago that we celebrated a monumental occasion, the chiropractic profession's 100th anniversary (Fig 1). There were some who attended the centennial celebrations who had thought at one time that the profession would not survive long enough to reach the century mark. Yet in spite of many hardships, some brave souls fought diligently and helped us accomplish our 100-year milestone. However, as with many achievements, once the event has passed, we often forget about what efforts need to be continued. Instead, we go back to the issues of the day. This makes me ask the following questions: Have we demonstrated professional and intellectual growth? Are we mature and wise enough to be comfortable in being proud of our past and at the same time capable of philosophical growth? These questions may be difficult to answer because there has not been a concerted effort to study our progress; however, I think that they are worth pondering.

Fig 1.

Badge from the chiropractic centennial celebrations held in 1995.

Chiropractic has been disparaged, sometimes correctly but sometimes incorrectly, for not being self-critical enough or for not developing sound scientific and philosophical constructs on which to build a profession.1,2 In addition, there has been infighting in the profession between those who wish to be grounded in science and philosophy and those who espouse that a dogmatic approach (under the guise of “philosophy”) will keep our profession strong and independent. Where do we in the chiropractic profession get our silliness from when it comes to our identity?

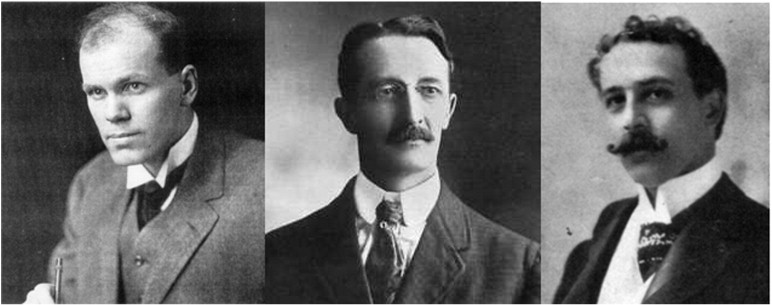

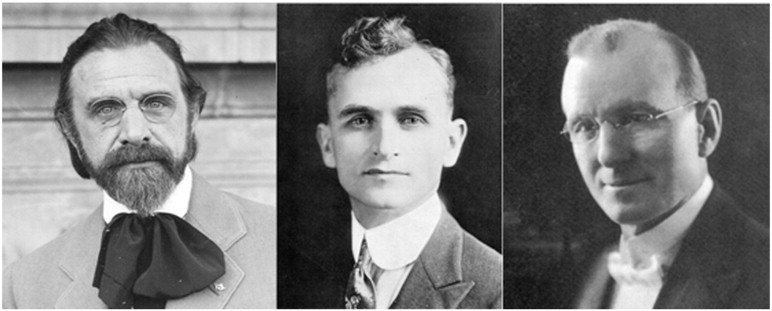

The original identity of the chiropractic profession was formed initially by our founder, Daniel David Palmer. Those DD Palmer taught, such as John Fitz Alan Howard, Solon Langworthy, and Oakley Smith, continued to develop chiropractic concepts and made additions and modifications to what they were taught; but they did so in isolation, not collaboration (Fig 2). Additional leaders would follow, such as Bartlett Joshua Palmer, Tullius de Florence Ratledge, and Willard Carver, who made changes in their approaches to educational programs and how chiropractors were perceived as healers (Fig 3). Although we had strong leaders, they were not united. Instead of cooperation, there was competition and infighting between factions. Many of these actions were posturing due to the proprietary nature of the chiropractic colleges in an effort to enroll students. These divisions created discontinuity and disruption in the development of the art, science, and philosophy of chiropractic. When chiropractic groups did work together, it was typically when chiropractic was being attacked.3

Fig 2.

Oakley G Smith, John Fitz Alan Howard, and Solon M Langworthy.

Fig 3.

Bartlett Joshua Palmer, Tullius de Florence Ratledge, and Willard Carver.

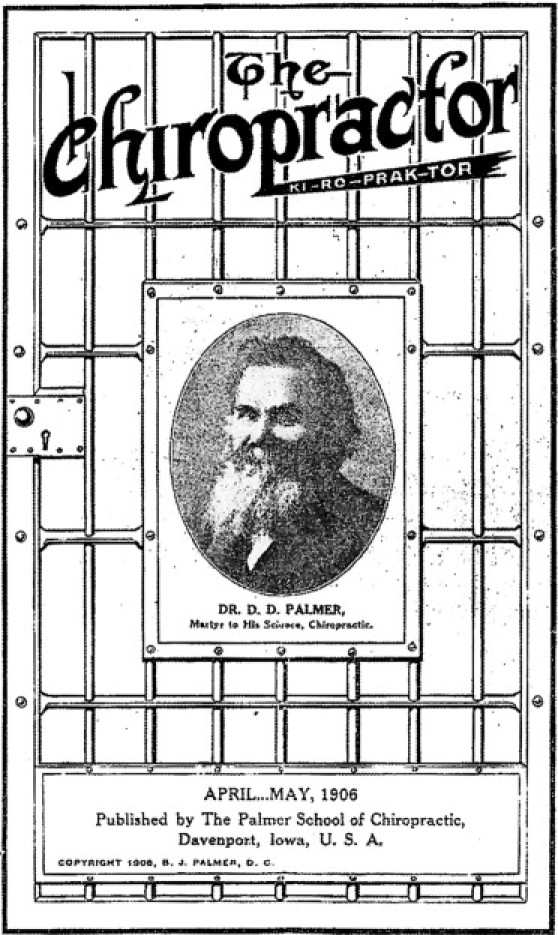

The medical and legal professions were in positions of power and cultural authority and provided external pressure that shaped the chiropractic profession. In the United States, medical licensing laws forbade the practice of medicine without a license. Medicine was dominated by allopathic “regulars” who, through the organization of the American Medical Association, developed a code of ethics that banned practice and association with irregulars.4-6 At the turn of the century, chiropractors were one of the primary targeted groups of “irregulars” that the medical profession was addressing in the legal arena (Fig 4). Such external pressures had wide-ranging effects on the chiropractic profession.

Fig 4.

Cover of The Chiropractor announcing DD Palmer's jailing for practicing chiropractic. The cover states “Dr. D.D. Palmer: Martyr to His Science, Chiropractic.”

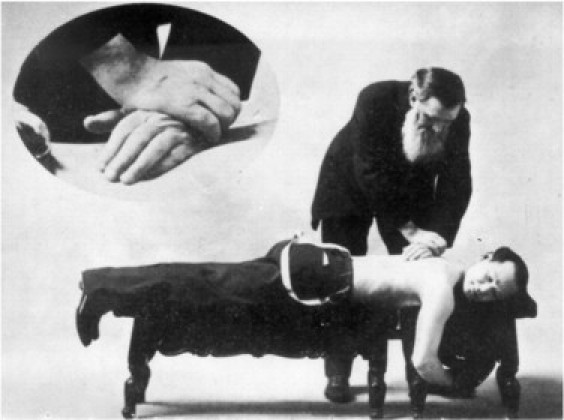

The first successful legal defense of chiropractic was the Morikubo trial (1907) in which Shegataro Morikubo, DC, was arrested for practicing medicine without a license7 (Fig 5). The legal defense, led by Tom Morris, set out to prove that one who was practicing chiropractic had a distinct art, science, and philosophy in an effort to distinguish this practice from medicine (Fig 6). The legal defense hoped that by proving that chiropractic was not allopathy, the laws of the time would not apply to chiropractors. Later, in 1911, the Universal Chiropractors Association (UCA) recognized the need to standardize terminology for the purpose of legal terms and set out “… to decide upon what was and what was not Chiropractic, what the U.C.A. could admit as Chiropractic and could defend”8 (Fig 7). At this same meeting, a report given on the standardization of chiropractic recognized that the legal defense counsel of the UCA (Morris and Hartwell) were defining chiropractic, “Morris & Hartwell … are standardizing Chiropractic. They are telling the local attorney what Chiropractic really is.”8 Chiropractic terminology, concepts, and definitions were crafted and refined for the courtroom, not necessarily from clinical or laboratory research. Thus, much of the terminology that we consider as a part of chiropractic identity today was not generated from a proactive development from within our profession but from a reactive set of legal defense arguments. Much of our identity did not necessarily come from internal formative developmental efforts, but instead from reactions to external pressures.

Fig 5.

Daniel David Palmer adjusting his former student and 1906 Palmer School of Chiropractic graduate, Shegataro Morikubo, DC.

Fig 6.

Thomas D Morris, who practiced with his law partner Fred H Hartwell, was the first lawyer to successfully defend chiropractic in the courtroom.

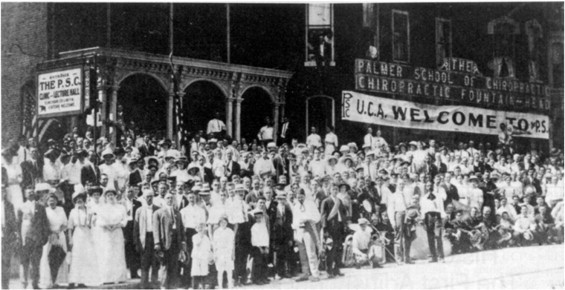

Fig. 7.

Universal Chiropractors Association Convention circa 1910. The UCA was founded in 1906 to legally protect its dues-paying members.

Success in a few of these legal trials gave early chiropractors hope and courage, but may also have given them overconfidence that ingrained some of these legal defense concepts into our culture and philosophical constructs. They also created a chink in our armor. The very arguments that seemed to save the profession in the early and mid 1900s now may be some of the greatest weaknesses that we face as a profession. Many of the current concerns, including diagnosis (vs analysis), manipulation (vs adjustment), treatment (vs care), disease (vs dis-ease), doctor of chiropractic (vs chiropractor), and scope of practice issues, would likely not be in existence if the profession had not been required to fight these medicolegal battles. It would have been interesting to see how we would have developed if we were left to develop on our own, but we will never know.

Understanding some of the origins of the difficulties we face today, we must decide how we should move forward. Do we need to hold on to concepts that served us well at the time but hinder us now? Should we ignore our past and stride forward without looking back? Choosing the latter path may detach us from our roots, leaving us ungrounded and unable to learn from our past mistakes. Should we hold tightly to past dogma and ignore the current scientific facts before us? Choosing the path of holding onto philosophy that is not supported by science turns us into fanatics on the fringe, a religious cult instead of a profession.

I feel that it is important to recognize the richness of our past and honor those who have come before us, but it is also important not to overinterpret their works or create gods of them. They were just people doing their job at that time. They most likely did not intend to have their actions and words be written in stone. Instead, they may have expected the future generations to think for themselves. Daniel David Palmer seemed to be comfortable with allowing the chiropractic profession to evolve, even if he wanted it to be on his terms. In the 1910 Chiropractor's Adjuster, Palmer wrote, “As a means of relieving suffering and disease, Allopathy, Homeopathy, Osteopathy, and now Chiropractic, have each in turn, improved upon its predecessor. But, as soon as the human mind is capable of absorbing a still more advanced method and human aspiration demands it, it will be forthcoming and I hope to be the medium thru [sic] which it will be delivered to the denizens of the earth.”9 Maybe we should allow our profession to grow, lest we become extinct like other healing professions before us.10

As a profession, we continue to struggle with empowering ourselves to question and think for ourselves while at the same time holding on to the spirit and identity of chiropractic. On one hand, some may feel that if we question the basis of chiropractic, we may lose our identity. On the other hand, some may feel that if we recognize our historical origins, we betray current concepts in chiropractic science and rational thought. As we grapple with these concepts, there is hope that there may be a common path that we can walk. As Ian Coulter, PhD eloquently states, “… philosophy is an activity and not some body of doctrine.”11 He also states that philosophy is critical, problem oriented, and controversial.11 Instead of memorizing rhetoric, we need to think critically and challenge the chiropractic profession to continue to grow in a meaningful direction.

Conclusion

Part of our journey on the professional path to enlightenment includes wrestling with what we think is true and what is the truth. There may be a path in which we can be proud of our past and learn from our mistakes while at the same time not letting past myths and legends destroy living in the present. I feel that after 115 years, we have the maturity and wisdom to embrace both. The question remains if we will have the courage to do so.

Funding sources and potential conflicts of interest

No funding was received for this article. Claire Johnson, DC, MSEd, is the editor of the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, and Journal of Chiropractic Humanities; a full-time professor at the National University of Health Sciences; peer review chair for the Association of Chiropractic Colleges; a board member of NCMIC; and a member of the American Chiropractic Association, American Chiropractic Board of Sports Physicians, International Chiropractors Association, Association for the History of Chiropractic, Counsel of Science Editors, American Public Health Association, Committee on Publication Ethics, World Association of Medical Editors, American Medical Writers Association, and American Educational Research Association.

References

- 1.Keating J.C., Jr, Green B.N., Johnson C.D. “Research” and “science” in the first half of the chiropractic century. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1995;18(6):357–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ernst E. Chiropractic: a critical evaluation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(5):544–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peterson D., Wiese G. Mosby; St Louis: 1995. Chiropractic: an illustrated history. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gevitz N. The chiropractors and the AMA: reflections on the history of the consultation clause. Perspect Biol Med. 1989;32:281–299. doi: 10.1353/pbm.1989.0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaptchuk T.J., Eisenberg D.M. Chiropractic: origins, controversies, and contributions. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2215–2224. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.20.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson C. Keeping a critical eye on chiropractic. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(8):559–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rehm W.S. Legally defensible: chiropractic in the courtroom and after, 1907. Chiropr Hist. 1986;6:51–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minutes. Sixth annual convention of the Universal Chiropractic Association. August 28–September 2, Davenport, Iowa; 1911. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmer D.D. Portland Printing House; Portland (Ore): 1910. Textbook of the science, art, and philosophy of chiropractic: the chiropractor' adjuster. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green B.N. Gloom or boom for chiropractic in its second century? A comparison of the demise of alternative healing professions. Chiropr Hist. 1994;14(2):22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coulter I.D. Elsevier Health Sciences; Woburn, MA: 1999. Chiropractic: a philosophy for alternative health care. [Google Scholar]