Abstract

Objective

This article offers the author's opinions about some of the thoughts, words, and deeds of the profession's founder, Daniel David Palmer.

Discussion

Reviewing D.D. Palmer's writings is challenging because he was the discoverer and founder of a developing profession and therefore his thoughts and words were rapidly evolving. Statements made by Palmer without judicious consideration of context could easily be misunderstood.

Conclusion

D.D. Palmer was individualistic and enigmatic. This commentary provides a look at the whole in an attempt to reveal the character and spirit of the founder.

Key indexing terms: Chiropractic, History, Spiritualism

Introduction

“Little deeds are like little seeds—they grow to flowers, and weeds.”1 Daniel David Palmer, the founder of the chiropractic profession, prophetically encapsulated the essence of his life. The thoughts, words, and deeds of this intriguing individual took root and blossomed into a profession. His words and deeds were diverse enough to provide a broad range of possible interpretations and were sometimes exploited or misrepresented by others to proffer meanings that are clearly inconsistent with the central theme of his values.

The purpose of this commentary is to offer my opinion of the thoughts, words, and deeds of the founder to suggest that the founder went through a dramatic, yet logical evolution of thought and action. The changes that took place in his thinking demonstrate that he strove to think without constraints and had a consistency that flowed in a rational manner fitting the chronology of events in his life. However, it is important not to seize upon a single time or idea and without consideration of the full context in order to draw unreliable conclusions.

The following statement by D.D.'s son B.J. Palmer shows his exasperation about capricious citations from the founder's words. Here B.J. explains how common citations of isolated statements were taken from his father's writings to fit someone's agenda without due regard to the time or context of an evolving philosophy, science, and art.

All his thinking was off the beaten path; he took the side roads; he wandered alone into the jungle, cut down virgin forests and beat out a new road. The price he paid was to be alone, followed by few, shunned by many, misunderstood by most, fought on all sides by those who profited most from his labors. But the sum total of that life led eventually to the great accomplishment for which history will know him best.

D.D. Palmer went through life a stranger to all but a sincere, honest friend within himself to himself. He knew as none others did what he was doing. He was a world of people in his own understanding of what he was doing for them. They sponged on him; they picked isolated sentences from his writings and twisted them to mean the opposite of what he believed and taught; they thrice denied him, even as many are doing today. They glorify his name; they erect monuments to his birthday at his birthplace; they praise Chiropractic and then say he stole it from the Greeks; and spit on what he stood for and fought so strenuously to preserve for the sick people he loved. If he were alive today, he would damn with no faint praise those who do these things to his Chiropractic and those who would fence it in so the sick people could not get it.2

Overshadowed in his lifetime by his son who dominated the profession, D.D. Palmer was nevertheless concerned about his own place in history. His writings that were compiled later by his son into the textbook bearing the title The Chiropractor's Adjuster documents his desire that others know his supreme position. The founder's 1910 text opens with the following validation from one of his earliest graduates:

T.J. Owens, D.C., President of The Universal Chiropractor's Association, also President of The Palmer School Of Chiropractic, founded by D.D. Palmer, says on page 23 of the August and September number of The Chiropractor, 1908: “The cause of disease remained an impenetrable mystery, until the month of September, 1895, when D.D. Palmer . . . made the most important discovery of this or any other century . . . .”3

Accepting and displaying recognition for making the “discovery of the century” may seem like a boast lacking humility in the context of today. However, in the context of his time, it takes on a different appearance. During the turn of the century, this method and style of communication was common. His concern about proper recognition is further demonstrated by paternal references to himself as “Old Dad Chiro,” and this typical passage from The Chiropractor's Adjuster: “Why not get a diploma with the name of D.D. Palmer, the discoverer, developer and founder of Chiropractic upon it?”3 His frustration about not receiving due credit shows through such as in the following statement: “In a few years I will have passed to the beyond, then I will receive the honor and respect due the man who gave Chiropractic to the world.”3

“Old Dad Chiro's” concerns about being recognized as the founder were substantiated. Both during his life and after his death, there were attempts to wrest credit from the founder regarding both his position as the originator and his role in the profession's philosophical legacy. A curious notion circulating among antiphilosophy proponents contends that all of the philosophy of chiropractic was developed solely for self-serving purposes instead of from multiple sources including the work developed by D.D. Palmer. One of these theories is that B.J. Palmer and his attorney Tom Morris crafted “chiropractic philosophy” as an afterthought to side step legal issues and to win the Morikubo case in 1907.

However, philosophical constructs existed prior to the Morikubo trial. It is noteworthy that the arrest of D.D. Palmer for practicing medicine without a license took place during the preceding year. The court found Palmer guilty, and he chose to serve time in jail rather than pay a fine. In contrast, the Morikubo case was a landmark in that it marked the first victory for the chiropractic profession in a court of law. The source of the allegation that the profession's philosophy was a strategic invention of the son and a crafty attorney may go back to 1938, 25 years after the founder's death.

Dr. Joseph Keating cited an article by Lee Edwards, MD, DC, “How far we have come? A pioneer looks back through the years.”4 As referenced in Keating's notes, the Edwards' citation states that Morris is credited for formulating a philosophy and science of Chiropractic in order that he might win acquittal in the Morikubo case.5 However, this reference ignores the other works that preceded the Morikubo trial.

The allegation that the philosophy of chiropractic was developed exclusively in 1907 as a legal maneuver is an interesting supposition. However, the deeper one looks for that thread of evidence in D.D. Palmer's work, the opposite picture comes into view. One notable summary statement can be found in The Chiropractor's Adjuster:

In that first adjustment given Harvey Lillard in September 1895, was the principle from which I developed the science of Chiropractic. In that adjustment originated the art of replacing vertebrae. In the succeeding fifteen years, I have endeavored to develop from that demonstrated fact, such principles, together with the art of adjusting, as constitute the science of Chiropractic.3

One may consider the aforementioned “principle” to be either philosophic or empirical. However, D.D. Palmer was aware of the relationship between science (relating to data gathering) and philosophy (relating to valuation of knowledge). This awareness speaks to his probable intent that the above principle was philosophical rather than empirical. This is further supported by the following insight into the founder's self-perceptions that provides an even stronger link to the philosophical underpinnings in the founder's evolving thoughts and deeds:

I systematized and correlated these principles, made them practical. By so doing I created, brought into existence, originated a science, which I named Chiropractic; therefore I am a scientist . . . I have reasoned from cause to effect; . . . answered the question, “What is life;” and founded a science and philosophy upon the basic principle of tone. This knowledge I have given to the world; therefore I am a philosopher.3

These statements, taken together with insights to be presented later, outline a consistent and coherent evolution of thought and action rooted in transcendentalism, spiritualism, and vitalism. These progressed into an interest in magnetic healing and then ultimately led to a principle that grew into the philosophy of chiropractic. When considered as a whole, there is a formidable body of evidence suggesting that the philosophy of chiropractic evolved over a period of years largely due to the evolving thoughts of the founder as opposed to a legal defense strategy contrived in 1907.

Although Senzon stops short of challenging the assertion of a nonphilosophic genesis for the profession, he provides additional discussion in his book that explores the philosophic foundations of the profession:

Even though Morikubo and his lawyer, Tom Morris, used a new textbook on chiropractic (the first textbook) by three of D.D.'s students, the concepts that would comprise chiropractic's philosophy can mostly be traced to the traveling library, which was over twenty years old by 1907.6

Palmer witnessed miraculous cures for 25 years, first from magnetic healing and then from chiropractic. He realized that there were principles at work that could not be explained by the mechanistic perspective, that the parts worked together in a unique organization to bestow life and health. Palmer defined life as “the result of vital force, spiritual energy, expressed in organic creation. For him, there was more to life than just scientific chemistry and matter: there was an interior and an exterior, which included vital spiritual energy. His terms to describe this were Innate, Innate Intelligence, . . . .”6

. . . For example, we know that Emerson, one of Palmer‘s inspirations, read Schelling and Hegel. These are not just parallels but the cultural waters that Palmer swam in. Palmer defined Universal Intelligence as―God, the ground of matter, the intelligence behind matter, and the organizing force of life, linked by soul to matter. He defined Innate as Spirit and also as Spiritual Intellect, a personified portion of the great universal.6

One of the more compelling evidences of the existence of the philosophic underpinnings of the profession prior to the Morikubo case is provided by Palmer in drafting the contents of The Chiropractor's Adjuster. There he tells us that he wrote about innate intelligence at least 1 year before his own arrest in 1906. Morikubo's arrest was not until 1907.

Among my writings of five years ago, was one on “Innate Intelligence.” It can be found in Vol. 1 of The Science of Chiropractic, commencing on page 109, covering five pages. It is “Copyright, 1906, B.J. Palmer, D.C., Davenport, Iowa, U. S.A.” . . . These “70 volumes of notes” are silent witnesses and will show when inquired for, that I was the originator of every idea in Chiropractic up to the time I left Davenport.3

To discuss the founder's evolution of thought and derive perspectives that take chronology and context into account, the following reviews various events in D.D. Palmer's life.

Influences shaping D.D. Palmer and his personality

Senzon's observations about the traveling library demonstrate that the founder had more than a passing interest in philosophic inquiry and that it predated the discovery of chiropractic.

The fourteen books and pamphlets that comprise Palmer's traveling library illustrate his spiritualist and magnetic healing influences, and also place him significantly within one of America's main religious cultures . . . An emphasis will be on topics such as magnetic healing, theosophy, spiritualism, and self-development. The traveling library is as follows: J.W. Caldwell's Full and Comprehensive Instructions: How to Mesmerize (1883/1885); Wilson's How To Magnetize; E.D. Babbitt's Vital Magnetism: The Life Fountain (1874); N.C.'s Thought-Transference with Practical Hints for Experiments (1887); C.A. DeGroot's Hygeio-Therapeutic Institute and Magnetic Infirmary; Knowlton's Fruits of Philosophy (1877); E.H. Heywood's Cupid's Yokes (1879); Juliet Severance's A Lecture on the Evolution of Life in Earth and Spirit Conditions (1882), A Lecture on Life and Health and How to Live a Century (1881), A Lecture on the Philosophy of Disease (1883); Might's Aphorisms of Confucius (1871); Denton's The Deluge in the Light (1882) and Be Thyself (1872).6

D.D. Palmer's traveling library is philosophically top heavy by any measure. That the founder literally traveled with the philosophic compilation cannot be stated with certainty. This collection of books was found in 1982 in the home of B.J. Palmer and identified as the traveling library by historians Alana Callender MS and Glenda Wiese PhD in 1982 with the assistance of Vern Gielow, author of the founder's biography, Old Dad Chiro. Its chronology and link to D.D. Palmer remain irrefutable; two of the texts even bear the founder's signature.7

Notwithstanding those influences are at best circumstantial. In addition to the books that the founder may have carried during his itinerant period is the influence of his friend and noted author, W.J. Colville. Four of the 7 pages of Palmer's preface to his 1910 text relate to a discussion of a recent visit from Colville and his letter “concerning the history of the principles which had been given to me . . .”3 Occupying a prominent position in D.D. Palmer's text and whose relationship as “an old friend” is explicitly endorsed by D.D. Palmer suggests that Colville played an important role in the influences on the founder.

Colville's Ancient Mysteries and Modern Revelations, published the same year as The Chiropractor's Adjuster, opens with the following statement:

Nothing can be more evident than that two diametrically opposite mental tendencies are now figuring prominently on the intellectual horizon. We note everywhere an intense and sometimes even fanatic interest displayed in everything marvelous or mystical and at the same time we cannot but be impressed with the distinctly rationalistic, often amounting to an evidently agnostic, trend of thought in many influential directions.8

Foremost among the topics in Colville's Ancient Mysteries and Modern Revelations were the following: Spiritual Elements in the Bible and Classic Literature; Egypt and Its Wonders Literally and Mystically considered; the Philosophy of Ancient Greece; Union of Eastern and Western Philosophy; The Message of Buddhism-Purity and Philanthropy; Ancient Magic and Modern Therapeutics; Life and Matter; Spiritualism; The Esoteric Teachings of the Gnostics; Halley's Comet; and Emanuel Swedenborg and His Doctrine of Correspondences. The latter, Emanuel Swedenborg's Doctrine of Correspondences, as an important element of Colville's thinking, also serves to link those influences that may have shaped D.D. Palmer's ideas with Transcendentalist thinking.

The influence of Swedenborg on the Transcendentalists has been established, especially in the case of Ralph Waldo Emerson as in Harvard University lecturer Eugene Taylor's 1995 book, ‘Emerson: The Swedenborgian and Transcendentalist Connection' in Testimony to the Invisible (Chrysalis Books). Other authors of the period known to have been impacted by Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772) include William Blake (1757–1827); Henry James, senior (1811–1882); Immanuel Kant (1724–1804); Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832); and Walt Whitman (1819–1892).9

Though Colville's relationship with D.D. Palmer can be substantiated, one is left to speculate about the depth of the friendship. It is interesting to note that W.J. Colville was a regular speaker on the Spiritualist camp circuit. Excerpted from extensive listings of Spiritualist meeting camps was the site of an 1880 event in Tama, Iowa (Tama was just 50 miles from What Cheer, Iowa, and the home of the Palmer family): “A LIBERAL LEAGUE CONVENTION AND SPIRITUALIST AND SECULAR CAMP-MEETING.—Will be held at Tama, Tama County, Iowa, September 7th, 8th, 9th, and 10th (1880).”10 It is also a matter of record that D.D. Palmer regularly attended Spiritualist camps at Clinton, Iowa,11 and D.D. Palmer's 1870's residence (Sweet Home) in Illinois was within walking distance of an important center for Spiritualist meetings.

In addition to philosophic influences, D.D. Palmer's thinking and writings may have been shaped by his maverick personality. As a young boy, Palmer was singular. People who met him remembered him as he stood out from others. Dr. C. Sterling Cooley, of Tulsa, Oklahoma, illustrated this characteristic on March 6, 1943, in a presentation to the Annual Palmer Memorial Banquet, in Toronto, Ontario:

From residents of Port Perry we have learned that “Dan” was a “keen youth”—a big, strong, husky, country boy, popular with everyone, constantly seeking knowledge about anything and everything, but singularly interested in anatomy. That interest he showed in collecting bones of animals. All who knew him describe him as a hearty, merry boy who exhibited, even in childhood, evidences of an exceptional mind.12

Palmer was by most accounts a unique character. Palmer had some formal education, but mostly he independently pursued his thirst for knowledge. This independent nature was evident in his confidence and irascibility. Described here by his friends and neighbors:

D.D. was of that rare type that stands out from the common herd. Physically, he was rather short of stature, heavy set, usually wearing a broad-brimmed black sombrero of the well-known Western type . . . D.D. was a real he-man. But woe upon the poor innocent who crossed his path . . . They feared his ability to express his biting humor and sarcasm with too forceful a logic.13

As a man he seemed to be hungry for knowledge and exceptionality. He was willing to open his mind to new ideas, even when inconvenient:

D.D. was a man who, once he became interested in anything, laid everything else aside—forgot it—and went ahead with the work, which he deemed more essential at the moment. D.D. was an omnivorous reader of literature dealing with the past history of treating the sick.13

D.D. Palmer and brother, T.J. Palmer, were tutored in natural sciences and classical languages prior to the Palmer family emigration from Canada to Iowa (circa 1856). The boys D.D., age 11, and T.J., age 9, remained in Canada. Although D.D. grew to be an intelligent and curious man, he had little moral or social guidance during his adolescent years. One can conjecture that in a time of great political and economic turmoil, this may have had a profound impact on the developing youth. He was young and alone and responsible to watch out for his younger brother during a time when the worth of man was bitterly and unfairly measured. The pioneer environment, racial, political, and economic disparities existing on both sides of the Canadian border during the War Between the States were all factors that would shape this rugged personality. What we do know with certainty is that D.D. and T.J. would leave Canada to rejoin the family in Iowa. On April 3, 1865, D.D. and brother T.J. walked 18 miles to Lake Ontario. D.D. age 20 and T.J. age 18 worked their way to Buffalo, New York, then to Detroit and Chicago, and after 2 1/2 months they arrived in Iowa.1

B.J. Palmer often made forthright statements about the strengths and weaknesses of his father. Though it is uncertain how many of these statements were truths, B.J.'s portrayal of his father's ethics lend the appearance of righteous values.

Coming to U.S. during Civil War times, it was either go to war or buy a substitute. We have heard D.D. tell that he bought a substitute for $500 rather than go to war himself. To shoot to kill was against his principle.12

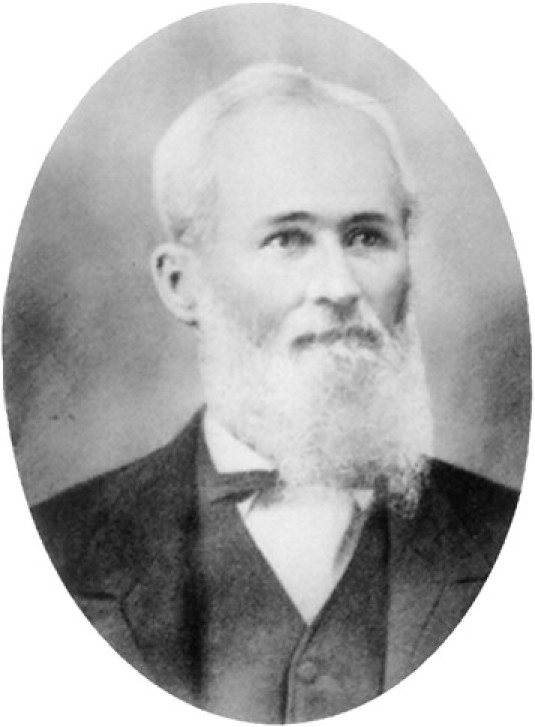

Upon arrival in Iowa, Palmer taught school at a time when the Iowa school system itself was only 30 years old (Fig 1). He taught on both the Iowa and Illinois sides of the Mississippi River, mostly in a number of 1-room country schoolhouses. He also served a stint teaching in a fine 2-story brick school building in New Boston, Illinois (built in 1858, it was considered one of the best in the state of Illinois).14

Fig 1.

D.D. Palmer, schoolmaster. (Courtesy of Palmer College of Chiropractic Archives, Davenport, Iowa.)

At first glance, the following excerpt from Palmer's diary would give the appearance of a mean-spirited teacher:

Whip; giving time between strokes … after punishing pupils do not let them go while sulky but keep until good natured; that they may not have the sympathy of others … To cure a person of theft or anything similar, make a deep impression on the mind of the wrongdoer, then write out a statement of the case in the form of a confession and have them sign it; promising them you will never divulge the secret if it is the last time; but vice versa.15

However, when put into the context of the standard practices of the time, this entry takes on a much different essence. That context becomes quickly apparent that this was considered acceptable practice in the following excerpt from the Rules and Regulations governing teacher conduct in the state of Iowa:

Teachers may inflict punishment by detaining a pupil . . . whipping with a switch or strap . . .16

Even many years later we find the mind of the schoolmaster showing through:

Exercises will be found scattered throughout the book. They are copied from books, booklets and leaflets of Chiropractors. I trust my criticisms may be beneficial to their authors as well as others; if so we are benefited. These can be utilized as blackboard exercises; if so, I would suggest that the books should not be opened during recitation, unless on rare occasions to settle doubtful or disputed points. Above all, the teacher should make a thorough study of the terms used, . . .3

D.D. Palmer was not soft on discipline. B.J. Palmer spoke of the hard side of his father as he simultaneously mitigates with an assurance of his humanity.

While teaching on the Illinois side of the river at New Boston, Palmer and his wife, Abba Lord Palmer, bought 10 acres of land, a few miles outside of town. At this time, the Civil War was ending. President Lincoln had been assassinated just 5 years before the 25-year-old Palmer purchased the nearby country acreage. In the spirit of the Transcendentalists, Palmer was self-reliant and determined (Fig 2). To supplement the modest income of a teacher, he became a beekeeper and developed and sold his own variety of raspberry, which he called the “Sweet Home Raspberry” (Fig 3). Palmer enjoyed success in both sales of the raspberry plants and in honey production. He also named the honey, “Sweet Home Honey" and his farm, Sweet Home became the country's largest apiary.12

Fig 2.

D.D. Palmer, circa 1870. (Courtesy of Palmer College of Chiropractic Archives, Davenport, Iowa.)

Fig 3.

At Sweet Home. The author and son, Jarred Brown, in 1996 examining some of the nonindigenous trees at the Sweet Home site. Palmer had drawn out a grid map in his journal identifying where he planted trees with notation of their type. Among the healthy trees on the site were many of the thorny locusts that were a source of nectar for D.D.'s apiary operation. We also found an extraordinary number of “wild” raspberries growing throughout the acreage. (Photo courtesy of the author.) (Color version of figure is available online.)

Spiritualism

During the 1850s, the Spiritualist movement spread from Europe to the United States. Exactly what sparked Palmer's initial interest in spiritualism is unknown; however, the location of Sweet Home was central to the Spiritualist movement in the Midwest. Two of Palmer's closest friends, Will and Mary Kellogg, who lived in New Boston, were very active in the Spiritualist movement. Palmer and the Kelloggs regularly attended the annual Spiritualist camp at Clinton, Iowa, and years later it was there that Palmer had an occasion to meet and debate with the founder of osteopathy, A.T. Still.11

D.D. Palmer became a Spiritualist, but not with séances and mediums. He actually put particular energy into “busting” frauds. This is evidenced by statements in D.D. Palmer's “Sweet Home” catalog. Found on the inside cover of the 40-page, raspberry nursery catalog was the following:

“A Day and Night with Spirits” at Mott's, Memphis, Missouri

For six years there has been a constant stream of travel there; thousands of all classes have visited it, and with few exceptions, —BEEN HUMBUGGED— No Threats Will Prevent Me From Exposing The Mott Swindle - D.D. Palmer, New Boston, Illinois, 1880.1

Within walking distance from Palmer's Sweet Home was the home of one of the country's most influential leaders in the Spiritualist movement. The estate, named Verdurette, was the home of William Drury, a Spiritualist (Fig 4). Drury became wealthy first in grocery and dry goods, then real estate. Drury is reputed to have become the single largest landowner in the entire country. Elderly area residents of a generation ago have reported seeing Palmer walking to and from the Spiritualist meetings at Verdurette. Thus Palmer was a participant in this culture.

Fig 4.

Verdurette, the Drury 24-room home; the first in the area with hot and cold running water, steam heat, and gas lights. Drury maintained a wild animal preserve on the 13 acres: buffalo, deer, elk, fox, antelope, swans, raccoons, badgers, and tigers. (Photo courtesy of the author.) (Color version of figure is available online.)

Important personal events

The marriage of Palmer and Abba Lord was troubled. Although little evidence is available, the death of their infant daughter may have played a meaningful role. This was a topic for discussion during a 1996 interview with Vern Gielow, the author of Palmer's biography, Old Dad Chiro, published in 1981.17 Gielow described how he had visited the gravesite and found the site to be consistent with Palmer's handwritten notes. Gielow had climbed to the top of the bluff to look for the grave of the child. He reported that he was unable to find a marked grave. However, he did find what he thinks was the vandalized gravesite and what appeared to be remaining shards of materials. The intact little graveyard of his infant half-sister was reported in more detail in a recorded lecture by B.J. Palmer who had visited the site in the early 1930s.14 It is certain that the Palmer-Lord marriage ended within 2 years of moving out to Palmer's beloved rugged hillside, Sweet Home. She sold her half of the acreage to a third party and relocated to Canada. It is difficult to know how the breakup might have personally affected Palmer, but teaching and maintaining the horticultural business interests was surely formidable.

The following year, 1874, Palmer embarked on a longer-lasting marriage to Louvenia Landers. Within 2 years they would have their first child together, a daughter whom they named May. While living at Sweet Home, Palmer enjoyed success as an educator, horticulturist, and seemed to find particular satisfaction with the apiary. His handwritten journal reveals that the end of the year 1880 ushered in a particularly severe Midwestern winter, killing off all of the bees. While he was still advertising his thriving business selling Sweet Home raspberry plants in 1880,1 we find that by 1881 he had sold all 10 acres of the homestead on a quit claim deed and relocated to What Cheer, Iowa, where his parents resided. There he opened a grocery store, raised and sold goldfish, and invented the first functional container to ship live goldfish (David D. Palmer, Oral history, classroom presentation, Davenport, IA, 1970). Although 1881 was stressful year for the 36-year-old Palmer, he and Louvenia were blessed with a son, Bartlett Joshua, who was born in their new home in What Cheer (Fig 5).

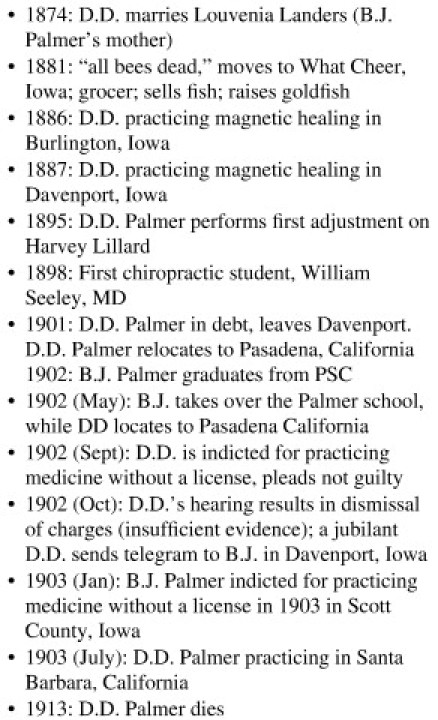

Fig 5.

Timeline.

Magnetism and spiritualism

Soon after moving to What Cheer, Iowa, Palmer became a student of prominent magnetic healer Paul Caster in Ottumwa, Iowa. Caster was a disciple of the teachings of Franz Anton Mesmer, from whose name was derived the verb mesmerize. Paul Caster became an extraordinarily successful practitioner of magnetic healing.

In 1866 he (Caster) took up the profession of magnetic healing and gained wide and lasting reputation by his skill and efficiency. Removing to Ottumwa, Ia., he erected a building there in 1869, at a cost of eighty-six thousand dollars—now the Ottumwa Hospital. There he treated people from all parts of the world, patients coming to him from distant sections of this country, as his fame demonstrated by the practical results that attended his efforts.18

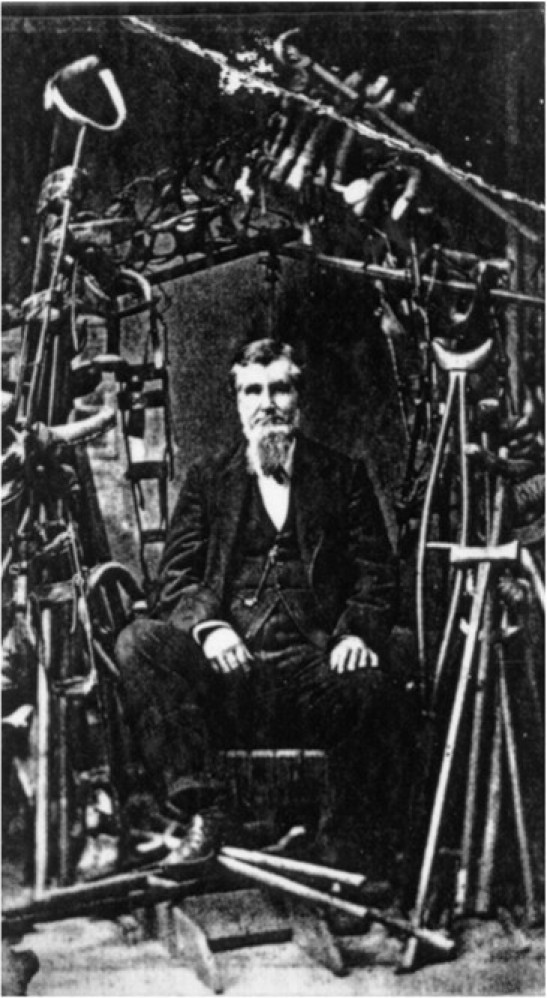

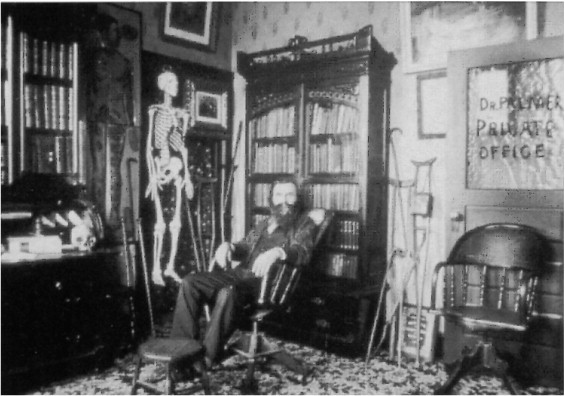

It has been said that Caster enjoyed being photographed with canes and crutches left behind by patients who benefited so much by his service that they no longer needed them. This was an interesting trait that Palmer was later to adopt in his own magnetic healing practice and persona (Figs 6 and 7).

Fig 6.

Paul Caster; note crutches and canes. (Courtesy of Palmer College of Chiropractic Archives, Davenport, Iowa.)

Fig 7.

D.D. Palmer, displaying crutches and canes on both sides of his chair. (Courtesy of Palmer College of Chiropractic Archives, Davenport, Iowa.)

With his propensity toward thinking about the immaterial side of existence as a Spiritualist, it was a small leap for Palmer to find an interest in magnetic healing. At the time, spiritualism and magnetic healing were often amalgamated.19 It is not known when Palmer studied with Caster as his certificate or diploma did not survive. However, it must have been close to the time of joining the family in Iowa, because in fewer than 5 years from relocating to What Cheer he had opened a magnetic healing practice in Burlington, Iowa. Ottumwa is a small city located approximately 30 miles directly south of the small town of What Cheer, Iowa.

Considering the notoriety and successes of Caster and the proximity to What Cheer, it is no surprise that Palmer studied with Caster. Palmer's attraction to magnetic healing seemed to be rooted in vitalistic thought:

Electricity, or galvanism, is of the earth, or mineral, cooling and shocking to the human system, and was never made for sensitive nerves. Animal magnetism and machine electricity are two quite different forces and differ in their uses. Magnetism is of man, the highest of creation, and is healing and life-giving, imparting vital and nerve force.20

B.J. Palmer reported that his father said that when he was near a person in pain, then he would feel their pain in the same place. If D.D. told the person about it, the pain would leave him. Another peculiarity of the founder has been relayed by his son as follows:

We have known him at various times to go direct to General Delivery window and say: “There is a letter here for me from O.G.W. Adams, Dubuque, Iowa. It was mailed yesterday. It has your postmark as of 3:00 p.m. yesterday afternoon. Please get it for me.” Getting letter, we have seen him hold it flat on his forehead, sealed and unopened, and start reading, and finish by reading entire letter EXACTLY as written, including signature, misspelled words, if any, underlined words, if any. He would then hand letter back, sealed, to man at window, ask HIM to open it and verify accuracy of his reading. Father was ALWAYS 100 per cent accurate.12

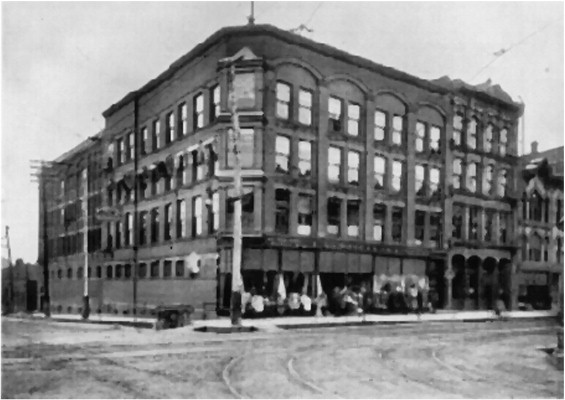

As a magnetic healer, Palmer practiced in Davenport, Iowa, and apparently had a unique approach (Fig 8). Whereas other magnetic healers would treat the whole body of the ailing person with their magnetism, Palmer sought to apply his magnetism in a more concentrated manner. He would determine the ailing organ and place 1 hand below the sick part and 1 hand above it, then pass his magnetic healing energy from one hand to the other.12

Fig 8.

Palmer's practice was a successful business. He would boast about his top-floor, 42-room infirmary: “our parlors, office, and infirmary are the finest in the city.” D.D. Palmer's magnetic healing practice occupied 42 rooms on the top floor of the Ryan Block. (Courtesy of Palmer College of Chiropractic Archives, Davenport, Iowa.)

Not surprisingly, Palmer remained a voice for specificity. He would later admonish other chiropractors for introducing as many as 6 to 10 forces into the spine of the patient on every visit, whereas he generally introduced but a single specific force:

Is the science of Chiropractic specific? If it is not specific, it is not a science.3

And:

The Chiropractor locates the impingement (to be specific, means one location and one adjustment; otherwise it is not scientific) … Chiropractic is a science just so far as it is specific. The ability to discriminate, to be precise, makes Chiropractic a science and an art.3

Transition to the philosophy of chiropractic

The philosophic roots of the new chiropractic profession can be found in Palmer's writing during his transition from magnetic healer to chiropractor. Written within the first 3 months after the reported Harvey Lillard incident of hearing restoration, D.D. Palmer writes:

Magnetism is of man, the highest of creation, and is healing and life-giving, imparting vital and nerve force.20

Multiple references suggest that the philosophic principle of innate intelligence was one of D.D. Palmer's earliest conceptions, as in the following:

Innate and Educated Intelligences were among my earliest Chiropractic conceptions. They were to me a vital fact, a condensed proposition of important practical truth; one of the basic principles of the science of Chiropractic.3

Also:

That which I named Innate (born with) is a segment of that Intelligence which fills the universe.3

The earliest writings of D.D. Palmer do not draw concrete delineations regarding religion, philosophy, and spiritualism, as his thinking evolved with vitalism and magnetism. This is apparent in his earliest attempts to comprehend his own breakthrough. Palmer attributed his leap in awareness to something closer to his then current context, a channeled spirit:

My first knowledge of this old-new doctrine was received from Dr. Jim Atkinson who, about fifty years ago, lived in Davenport, Iowa, and who tried during his life-time to promulgate the principles now known as Chiropractic . . . the intellectuality of that time was not ready for this advancement.3

B.J. Palmer would address the issue in later years by relaying that as his father grew further from the Harvey Lillard incident, he spoke less and less about Atkinson and more about the art, science, and philosophy that more rationally explained the phenomenon:

He eventually came forth with the clean-cut understanding of innate Intelligence within him. When that permeated his thinking, he ceased to credit “Jim Atkinson” with anything, and credited it all to THE BIGNESS OF THE FELLOW WITHIN himself . . . There was a strain of the mysterious unknown in father's early thinking . . . We are convinced he was completely disillusioned in later years of “Jim Atkinson” he wrote about in his book.12

Although unclear in the delineations, the founder was evolving in his thinking. Palmer's early explanations of chiropractic had a strong spiritualist flavor:

Chiropractic is the name of a systematized knowledge … and the prolonging of life, thereby making this stage of existence much more efficient in its preparation for the next step—the life beyond . . . . In this volume I have systematized the knowledge acquired during the last twenty-five years . . . the art of adjusting vertebral displacements, together with an extensive philosophical explanation of the laws of life . . .3

The founder valued the written word, which is a fitting quality for a 19th century schoolmaster. His ability to write with a flair and certainty seems to shine through whether reading catalogues for his raspberry nursery stock, his teaching methodology notes, or letters to professional colleagues. Whether during the days as a school teacher, horticulturist, magnetic healer, grocer, or later as a chiropractor, one trait that was deeply ingrained in the founder was his meticulous note keeping. His handwritten journals had an artistic style to the lettering that suggests he valued the written record and took pride in the appearance of it. This is evidenced by his drive for the best quality in care as well as his efforts to chronicle the evolving science of chiropractic.

It has been one of the rules of my life, that what is worth doing at all is worth doing well. In Chiropractic this is especially so; particularly when laying the foundation for a coming science which is destined to be the grandest and greatest of this or any age.3

I saw fit TO DATE THE BEGINNING of Chiropractic with the first adjustment, although quite a portion of that which now constitutes Chiropractic I had collected during the previous nine years.3

Teaching chiropractic

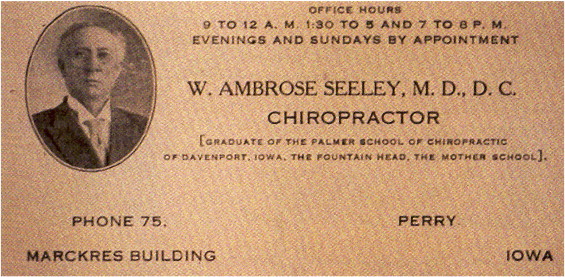

Palmer began to teach chiropractic in 1898. His first student was a physician, William Seeley, MD (Fig 9). Palmer seems unequivocal that his purpose in teaching was based in an ethical and pragmatic necessity.

Knowing that our physical health and intellectual progress of this world and the next depends largely upon the proper alignment of our skeletal frames; therefore, I feel it my bounden duty to not only replace displaced bones, but also teach others, so that the physical and spiritual may enjoy health, happiness and the full fruition of our earthly lives.3

Fig 9.

William A. Seeley, MD, DC, business card reveals a pride about being a Palmer School graduate. (Courtesy of Palmer College of Chiropractic Archives, Davenport, Iowa.) (Color version of figure is available online.)

Palmer taught chiropractic with a vitalistic approach. In the following 2 passages, his position is not mechanistic:

Some Questions Answered:

Do you use electricity—a battery or electric belts? — No

Do you use medicine or drugs? — No

Do you rub, slap, or use massage? — No21

Nor is he entrenched only in the immaterial:

Do you hypnotize or mesmerize your patients? — No

What is your religion? — To do good.

Do we have to have faith? — No, I often treat children less than a year old.21

The coherence of this vitalistic approach can be found throughout other areas of the founder's work. He valued science, but he also insisted on its application in relevant ways.

The science of chiropractic and that of machinery have no resemblance whatever, in their motive force. That being a fact, why try to illustrate either one by the principles belonging to the other? Just as well try to explain the science of grammar by that of astronomy; geography by mathematics; chemistry by agriculture; or that of music by navigation. Man is not a machine.22

Incongruity can be found in the contrast between the above statement and some of Palmer's earlier statements if one were to read them absent of context. When reading the works of D.D. Palmer as a whole, it is apparent that a vitalistic philosophy is embodied in his work. However, there are also statements to the contrary, in which mechanistic views are more apparent such as the following:

A human being is a human machine and, like a machine, would run smoothly, without any friction, if every part was in its proper place.23

The latter statement was made during a time of transition between magnetic healing and chiropractic; before Palmer taught his first chiropractic student; at a time when the word chiropractic was less than 1 year old. Palmer was undergoing an evolution of thought and action. It is important to put into context and time the statements that Palmer made to better understand them. An example is the following sentence, which has been often cited without regard for the context of the overall life's work of Palmer: “I have never felt it beneath my dignity to do anything to relieve human suffering.”3 The above quote is in harmony with the spirit of the personality of D.D. Palmer. Nevertheless, it misses the point when considering his overall view of the profession he founded. As pointed out by B.J. Palmer, “. . . they picked isolated sentences from his writings and twisted them to mean the opposite of what he believed and taught . . .”

The definition of chiropractic attributed to D.D. Palmer appears on page 225 of the 1910 text, with similar versions on page 335 and 368:

Chiropractic is a name I originated to designate the science and art of adjusting vertebrae. It does not relate to the study of etiology, or any branch of medicine. Chiropractic includes the science and art of adjusting vertebrae—the know how and the doing.3

As a teacher, Palmer condemned the extremes in the immaterial (as well as in the material):

Meditating doctors

. . . then they meditate upon your complaint and think that nothing ails you; that in this world whatever seems real is unreal; that of which we know nothing is in truth the only real existence; therefore, this painful existence is only imaginary—all a dream . . . this kind of meditation is called Christian Science. There is as much science in the above method as there is in giving poisonous drugs to scare the disease away. 21

Palmer also taught distinctions between the dualistic new philosophy and science with its material and exclusively immaterial predecessors:

Suggestion exists only as an imaginary, mythical delusion. Chiropractic is a veritable fact, yet in its teens. The idea of trying to unite, in monogamous wedlock, this American youth with an antiquated myth, or the notion that suggestion is a twin of this modern prodigy, is preposterous. Suggestion—where everything may be anything; where nature has no laws and imagination no limits.3

He coupled the immaterial with that which is merely material:

The basic principle, and the principles of Chiropractic which have been developed from it, are not new. They are as old as the vertebrate. I DO CLAIM, HOWEVER, TO BE THE FIRST TO REPLACE DISPLACED VERTEBRAE BY USING THE SPINOUS AND TRANSVERSE PROCESSES AS LEVERS WHEREWITH TO RACK SUBLUXATED VERTEBRAE INTO NORMAL POSITION, AND FROM THIS BASIC FACT, TO CREATE A SCIENCE WHICH IS DESTINED TO REVOLUTIONIZE THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF THE HEALING ART [emphasis in original].3

He blended the material with the immaterial, a vision that would be largely lost on the majority of his students as well as chiropractors of the developing profession. Despite the fact that the Palmer School under B.J. Palmer's leadership was rooted in his father's vitalistic approach, the profession chose a path focused on musculoskeletal symptoms and conditions as evidenced by the practice paradigms it developed. Its educational programs grounded in a mechanistic model compared with D.D. Palmer's more comprehensive vision:

The principles of Chiropractic should be known and utilized in the growth of the infant and continue as a safeguard throughout life. The cumulative function determines the contents of the intellectual storehouse. The condition of the physical decides the qualifications of the mental. We take with us into the great beyond, when intelligent life ceases to unite spirit and body, just what we have mentally gathered, whether those thoughts are sane, or monstrous conceptions—are of reason, or the vagaries of a freakish mind. This philosophy will make the junction between the physical and the spiritual comprehensive; it will advance mankind mentally, physically and spiritually.3

And:

The universe is composed of the invisible and visible, spirit and matter. Life is but the expression of spirit thru matter. To make life manifest requires the union of spirit and body.3

Palmer's pragmatic unification of the material with immaterial is perhaps one of the most underestimated outcomes of all of his teachings. He illustrated the expression of the material working along with the immaterial through the concept tone:

Life is the expression of tone. In that sentence is the basic principle of Chiropractic. Tone is the normal degree of nerve tension. Tone is expressed in functions by normal elasticity, activity, strength and excitability of the various organs, as observed in a state of health. Consequently, the cause of disease is any variation of tone—nerves too tense or too slack.3

Also:

Tone is that state of tension or firmness in nerves and organs necessary for normal transmission of impulses and the proper performance of functions.3

Prophetic of the profession's current identity crisis, D.D. Palmer was clearly troubled by the outcomes of his endeavors to teach chiropractic:

. . . there is one thing I note, that when I teach the science to one person and that person teaches it to another and the third person teach it to the fourth, that they get away from the chiropractic until in the hands of the third or fourth person is hardly recognizable as chiropractic.24

And:

D.D. was always critical of the practices and teachings of those whom he felt had strayed from the straight and narrow practices originally laid down by him, of adjusting only at the subluxated vertebrae of the spinal column.13

During this early period of development of the philosophy of chiropractic, Palmer was known to ponder much and debate often with his students/colleagues. He developed a reputation for being difficult at times, and financially the school suffered. This led to his first departure from Davenport, leaving his son in charge of the school as well as its debt.

D.D. Palmer, chiropractor

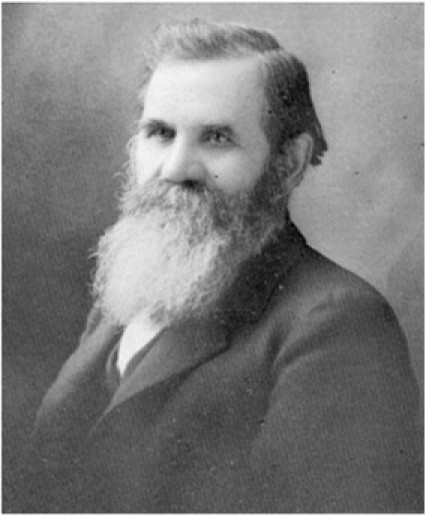

All people have individual personalities that combine various traits (Fig 10). The founder of chiropractic was no exception. Historian A. August Dye personally knew Palmer and was able to give a rare and thoughtful description of Palmer's character:

D. D. was a sturdy individual, opinionated to a very marked degree,— so much so that he could not work with any other man or group of men long in harmony . . . The senior Dr. Palmer was what we would call, in the vernacular of the day, a rugged individualist.13

Fig 10.

D.D. Palmer circa 1902. (Courtesy Palmer College of Chiropractic Archives, Davenport, Iowa.)

A former business associate and attorney, Willard Carver states:

Those who know D.D. Palmer know that no man living could become his associate in business and remain with him for any considerable length of time.25

Perhaps the most alarming look into the family life of the man is portrayed by his son:

All three of us got beatings with straps until we carried welts, for which father was often arrested and spent nights in jail. Our older sister was badly injured and has been sickly all her life. Our younger sister had a severe abscess caused by beatings. We have a fractured vertebra and a bad curvature from same source. None of this was because D.D. was naturally cruel or inhuman.12

The softer side of Palmer is depicted by the memories of Katherine Weed (daughter of Samuel Weed) when she was a little girl:

I remember Dr. Palmer's apartment (Palmer Infirmary) on the 4th floor of a building on, I believe, 2nd Street in Davenport, I remember the elevator in the building. Remember the alligators in a large glass tank of water; remember his large collection of rattlesnake rattles. Remember the deer-heads with locked horns, which adorned the living room. I remember Dr. Palmer's kind, gentle manner of adjusting. He never charged for adjusting me; he said it was because I was good and took the adjustments well.12

It is interesting to note that by the second year into the existence of the profession, Palmer was consciously moving the objective of the new art and science distinctly away from the objectives of the allopathic arts. He rejected terms that tended to suggest curing by healers and physicians.

Chiropractic is manual—done by the hand, but is not therapeutical, does not use remedies.3

Consistent with his view that he had discovered an entirely new principle and practice, Palmer wished to name the new art, science, and philosophy. He sought help from a friend, patient, and Greek scholar, Reverend Samuel Weed. He wished the name to reflect the fact that the new art was “done by hand.”

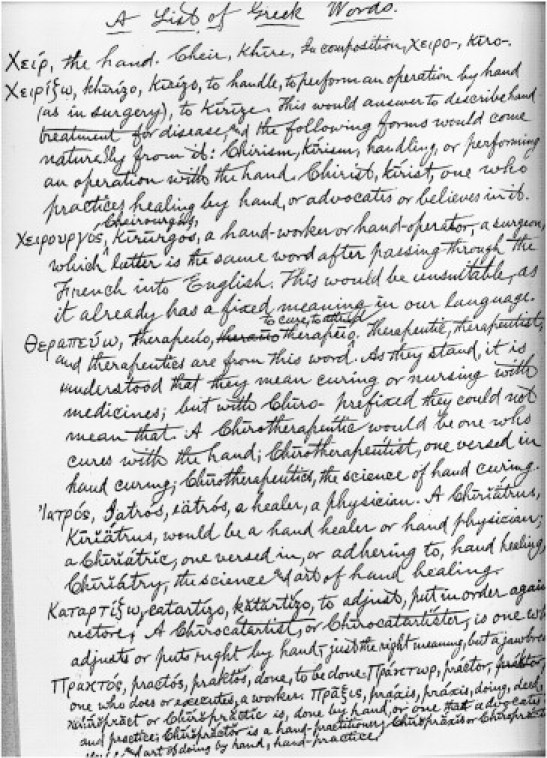

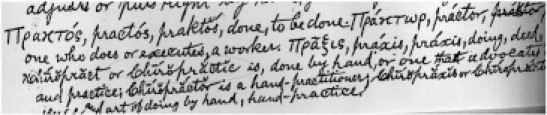

Reverend Weed offered numerous possible Greek phrases as options (Figs 11 and 12). The term Kirize was found to link closely to surgical work, which, like chiropractic, is “done by hand.” He also rejected the option Chirotherapeutist, which would literally mean curing or nursing with medicines. The root therapeutic appears in a number of the Greek options provided. Apparently, Palmer found those options too therapeutical as well. Weed's letter also pointed out the option Chiriatric, derived from the Greek word Kiriatrus, which means “hand physician.” However, it is apparent that Palmer's thinking had moved away from the therapeutic paradigm, as evidenced by his rejection of lexicon incorporating concepts like “healing and physician.” Reverend Weed suggested that Chirocatartist would be the most suited to describe one who adjusts or puts right by hand. He states that it has “… just the right meaning, but a jawbreaker.” Finally Chiropractic, literally meaning “done by hand,” was chosen by the founder as the best representation (Fig 13).

Fig 11.

Letter from Rev. Samuel Weed to D.D. Palmer suggesting possible Greek names for the fledgling profession. This letter was uncovered as a part of B.J. Palmer's historic scrapbook. (Courtesy of Palmer College of Chiropractic Archives, Davenport, Iowa.)

Fig 12.

Reverend Samuel Weed was both a patient and a friend to the founder of the profession. (Courtesy of Palmer College of Chiropractic Archives, Davenport, Iowa.)

Fig 13.

D.D. Palmer's choice to name the profession Chiropractic. (Image is a magnified portion of Fig 11; courtesy of the author.)

Palmer jailed

The following terse, ominous telegram said all that needed to be said when contacting a family friend who also happens to be a practicing attorney:

To: Willard Carver, Ottumwa, Iowa, “Father in jail — come to Davenport at once.”

From: B.J. Palmer2

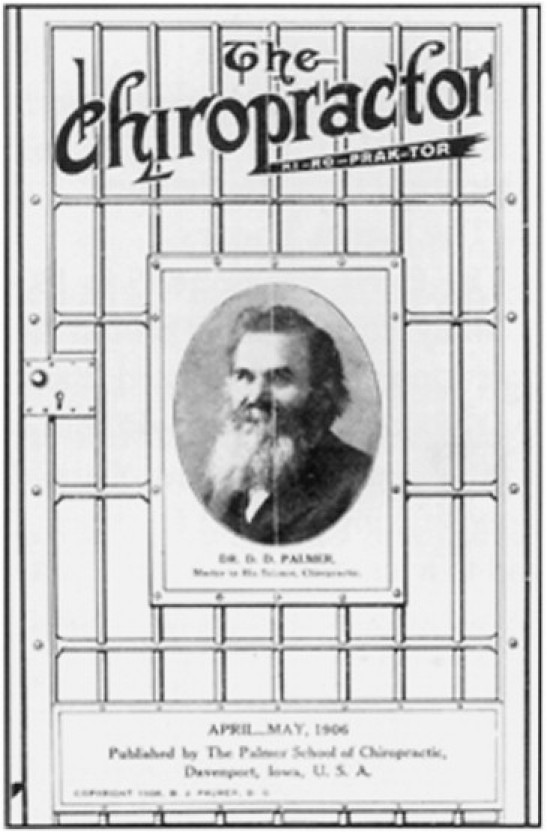

The first chiropractor to be incarcerated for practicing medicine without a license was D.D. Palmer (Fig 14). The Palmers were advised by Carver to place the management of the school and publications in the hands of a member of the medical profession based on Carver's belief that it would be harder for the medical fraternity to prosecute the Palmers when the publications were published by one of their own. They hired M.P. Brown, MD, DC, one of Palmer's earliest students, to take the position of dean and to manage the school and publications.26 Nevertheless, the case was lost. The Court offered D.D. Palmer the alternative of paying a fine, but the founder refused thinking that martyrdom could be a useful tool for promoting chiropractic (and perhaps thinking that each day served would diminish the amount owed). A 1906 newspaper article chronicled an interview with D.D. at the Scott County Jail, where he was confined in a cell.

After I went to jail, several parties phoned to my home and others called offering to lend me money with which to pay my fine. I am not in a cell for lack of principal, but for an abundance of principle.27

Fig 14.

Journal cover photo depicting Palmer in Scott County Jail. From The Chiropractor, April-May 1906. (Courtesy of Palmer College of Chiropractic Archives, Davenport, Iowa.)

Initially Palmer seemed to approach his situation cheerfully as evidenced in the following letter:

. . . At 10:00 a.m. today, I will have in four days. I do not know that I ever felt happier in my life. I have had my breakfast which consists of good bread, poor coffee, and poor molasses. I have a good appetite. The first day was the worst. My room (cell) was very filthy with tobacco juice and dirt. I have put in one hour each day. Now I have it nice and clean. My rent is paid for three and a half months. This includes water, steam heat, and janitor . . . I am pleased that it has been my lot to be incarcerated for the science which I have devoted so many years to develop . . . I remain, as ever, the discoverer and developer of the science of Chiropractic, and am ready to stand by it.28

However, his situation seemed to deteriorate, and he appears to enter the last segment of his life as a despondent and critical individual. There is little information to corroborate whether he may have been injured while in jail, however, Maynard asserts that he sustained a head injury, which may have caused mental deterioration.29

Although his attitude seemed to have rough edges, what did not seem to deteriorate was his ability to write. D.D. Palmer wrote the following to B.J. Palmer in an October 2, 1907, letter from Medford, Oklahoma (where he was operating a grocery). The letter was in response to a September 30 letter from his son:

I am interested to learn that “new move of chiropractic work . . . ” When the first machine was made to revolve by steam, then it was easy to improve the idea. Thus it was with the telegraph, the reaper, the telephone and also Chiropractic . . . How much better to have had those Chiropractic books grammatically written. The extra expenses would have been light. Old Dad was not there to do it . . .30

Paranoia and mistrust were obvious in this section of the same letter:

While I was helpless in prison, you usurped all, left me penniless, my property was given to and in charge of those who desired to oust me. In a settlement you took every advantage possible to further that object. To be “The Honored President” with such dishonors is not desirable.30

The legal record documents that there were mutual agreements on the dissolution of the partnership. The record indicates that B.J. Palmer purchased the school and equipment from his father in 1906 after D.D. Palmer was released from jail. The negotiations (binding arbitration) for purchase were mediated by respected local businessmen, Joseph Schillig, DC, and R.H. St. Onge. It appears that the founder was frustrated and disappointed and that his son was a target for letting out these frustrations as noted by historian A. August Dye:

He was jealous of the success B.J. was having with the new school, … D.D. had been unsuccessful both in his several schools and business associations, and in being unable to regain leadership of Chiropractic.13

Last years

The influence of Palmer on the profession after his 1906 departure from Davenport declined. D.D. Palmer, discoverer, scholar, founder, teacher, student of flora and fauna, innovator, and gifted writer wrote only 1 text on the subject he most cherished. It is a matter of record that D.D. engaged in numerous business ventures and attempted to initiate several schools of chiropractic with partners. None of the partnerships would last and most of the schools failed in short order. Later he visited Davenport in 1911 and 1912. He and his son attempted reconciliation with limited success.

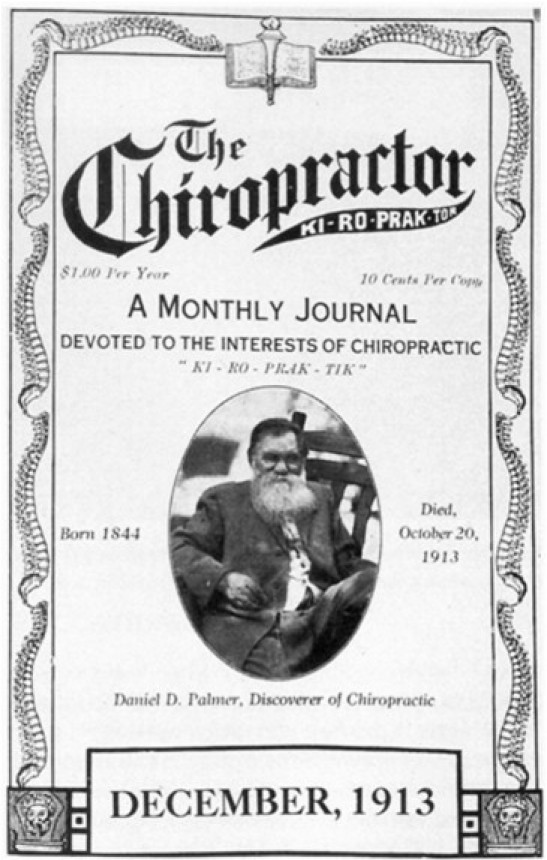

Ironically, Palmer became a guest lecturer at the Universal Chiropractic College, a rival institution also in Davenport. Dr. Joy Loban, a previous faculty member employed by B.J. Palmer, founded the Universal Chiropractic College when Dr. Loban and about 50 Palmer School of Chiropractic students walked out during a lecture by B.J. Palmer in April 1910. The group marched down Brady Street hill and opened the Universal Chiropractic College. The protest was largely over B.J. Palmer's introduction of the x-ray at the Palmer School. The animosity grew between Loban and B.J. Later Loban accused B.J. Palmer of striking D.D. Palmer with an automobile during the August 20, 1913, Lyceum parade. D.D. Palmer died of typhoid fever several months after an August 1913 visit to Davenport (Fig 15). Loban claimed that injuries caused in the incident resulted in the death of D.D. Palmer. The scandalous accusations were later retracted.2 Nevertheless, the perception of wrongdoing harmed the reputation of B.J. Palmer.

Fig 15.

D.D. Palmer's death announced on the cover of The Chiropractor. (Courtesy of Palmer College of Chiropractic Archives, Davenport, Iowa.)

B.J. Palmer gave an interesting glimpse into the founder's life after his release from jail:

“Father married his first love, last”

[Transcription from a Lyceum lecture audio recording]

… Well anyhow, it's interesting to close with one thought.

When father was out in Letts (Iowa) he met a Molly Hudler and he dearly loved that woman.

I don't know why he didn't marry her, perhaps he was then married to one of his wives (I don't know); but he fell desperately in love with Molly Hudler and he didn't see her for many, many years.

And finally one year he came back; when he was a widow.

Villa Thomas who was the fifth wife had died. And he was now single and he had

run into Molly Hudler and married her finally at the end – the sixth wife.

And Molly was a pretty decent sort of a gal, I liked her and I think she liked us, we kids.

But I just mentioned in passing to show you that, if first you don't suck-ceed, keep sucking until you do!

And so father married his first love, last.

I don't want you to get the wrong impression, peculiarly I have very little respect for my father, as a father. Now don't misconstrue that. As a father, he never was a father to we children. But I place that man up on a pedestal, to me he is one of the great men of history.11

D.D. Palmer was serious about chiropractic. A useful summary statement that reminds us of his concepts uniting the material with the immaterial can be found on page 19 of his textbook, The Chiropractor's Adjuster:

I CREATED THE ART OF ADJUSTING VERTEBRAE, using the spinous and transverse processes as levers, and named the mental act of accumulating knowledge, the cumulative function, corresponding to the physical vegetative function—growth of intellectual and physical—together with the science, art and philosophy—Chiropractic.

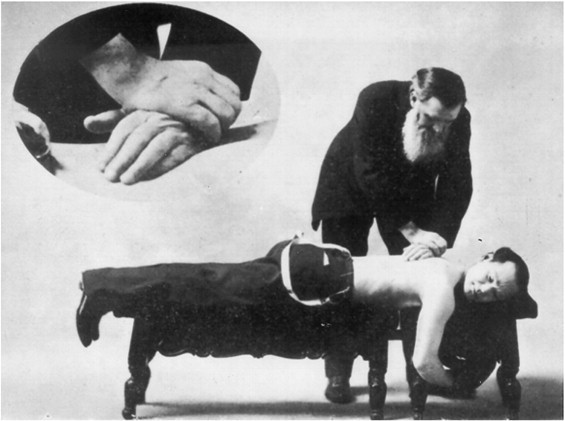

An excerpt from the December 1906 commencement address by Morikubo (Fig 16) to the Palmer School of Chiropractic represents an ideal underpinned by deep conviction:

Like the horizon, chiropractic shows limitation when the vision is incapable of seeing farther. As you approach the first point where you thought heaven touched the earth, it vanishes; so likewise, what may seem a limitation to chiropractic is but an imaginary visible horizon because of our inability to perceive greater.

—Shegetaro Morikubo

Fig 16.

D.D. Palmer adjusting Shegetaro Morikubo, PhD, DC. (Courtesy of Palmer College of Chiropractic Archives, Davenport, Iowa.)

D.D. Palmer was individualistic and enigmatic. To reveal the character and spirit of the founder, we must look at the whole. In final summary, D.D. Palmer's chiropractic is, in the spirit of Morikubo's words, the story of those who saw further.

Funding sources and potential conflicts of interest

The author reports no funding sources or conflicts of interest for this study.

References

- 1.Gielow V. Bawden Brothers; Davenport, IA: 1981. Old dad chiro. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmer BJ. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1949. The bigness of the fellow within. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer DD. Portland Printing House; Portland, OR: 1910. The chiropractor's adjuster: the science, art and philosophy of chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keating JB. Research notes cite Edwards from the old NCA's. National Institute of Chiropractic Research. Section: Chrono-logy of Lee W. Edwards, M.D., D.C. p. 6-7. Available at: http://www.chiro.org/Plus/History/navigate.html.

- 5.Keating JB. Chronology of Shegataro Morikubo, D.C. National Institute of Chiropractic Research, unpublished database: Morikubo CHRONO 07-04-25 (p. 2). Kansas City, MO: National Institute of Chiropractic Research.

- 6.Senzon S. Palmer's traveling library. Asheville, NC; Author: 2007. Chiropractic foundations: D.D. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiese G. Palmer Archives; Davenport, IA: 2008. E-mail to the author: “Two of the texts are signed, ‘D.D. Palmer,' one in New Boston, IL in 1873 and the other in What Cheer, IA in 1886.". [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colville WJ. Ancient mysteries and modern revelations [facsimile of 1910 edition] Kessinger Publishing; Whitefish, MT: 1997. p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- 9.The Swedenborg Society Writers-influenced-by-swedenborg. www.swedenborg.org.uk/writers-influenced-by-swedenborg Available at: Accessed 18 May 2008.

- 10.Britten EH. Chadwyck-Healey Ltd.; UK: 1999. Nineteenth century miracles or spirits and their work in every country of the earth. Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmer BJ. Palmer School of Chiropractic; ca; Davenport, IA: 1940. Early history of chiropractic [audio-recorded Lyceum presentation] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmer BJ. Palmer School of Chiropractic; Davenport, IA: 1950. Fight to climb. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dye AA. Author; Philadelphia, PA: 1939. The evolution of chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zdrazil GA, Brown MD. A visit to Sweet Home. Chiropr Hist. 1997;17(1):85–91. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palmer DD. Handwritten journals [unpublished]. Davenport, IA: Palmer College of Chiropractic Archives.

- 16.State of Iowa. Iowa rules and regulations for the government of school officers and the management of public schools based on section 32, part 33, School Laws of 1862.

- 17.Zdrazil GA, Brown M. Recorded interview with Vern Gielow, E.L.R. Crowder, Juanita Crowder, and Mary McCubbin. Author; 20 January 1996.

- 18.Decatur County Journal. Decatur County, IA; 16 July 1914. Available at: http://genforum.genealogy.com/cgi-bin/print.cgi?biederman::24.html.

- 19.Strauss JB. Refined by fire. Foundation for the Advancement of Chiropractic Education; Levittown, PA: 1994. p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer DD. Vital magnetic healers. Magn Cure [Davenport, IA] 1896;(15):1. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palmer DD. Some questions answered. The Chiropractic – Eleventh Year [Davenport, IA] 1900;(26):1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer DD. Press of Beacon Light Publishing Company; Los Angeles, CA: 1914. The chiropractor. [compiled posthumously by Mrs. D.D. Palmer; circa uncertain regarding various portions of the work, which was a compilation of various writings of the founder] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palmer DD. Healing the sick. Chiropractic, Ninth Year [Davenport, IA] 1897;(17):1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmer DD. Class room lecture. Oklahoma City, 21 February 1908 [cited in Gielow V, Old dad chiro. Bawden Brothers; Davenport, IA: 1981. p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carver W. Palmer Archives; Davenport, IA: 1913. Chiropractic record. Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, History of Chiropractic, July. Chapter 8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown MD. Overlooked! Back on record, Martin P. Brown, M.D., D.C. Chiropr Hist. 2004:27–34. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davenport Democrat . Palmer Archives; Davenport, IA: 1906. An interview with D.D. Palmer at the Scott County Jail (fragment) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palmer DD. Palmer Archives; Davenport, IA: 1906. Letter written to S.M. Langworthy from Scott County Jail, April. Cited in: Palmer BJ. History Repeats. Davenport, IA: Palmer School of Chiropractic. p. 69-71. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maynard JE. Healing hands. Jonorm Publications; Mobile, AL: 1959. p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palmer DD. Letter written to son, B.J. Palmer, October 2, 1907, from Medford, Oklahoma. Davenport, IA: Palmer Archives.