Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this article is to establish a metatheoretical framework for constructing a philosophy of chiropractic by using Integral Theory and Integral Methodological Pluralism. This is the first in a series of 3 articles.

Discussion

The philosophy of chiropractic has not thrived as a philosophic discipline for multiple reasons. Most notably, these include disparate personal and cultural worldviews within the profession, a historical approach to chiropractic's roots, and an undeveloped framework for exploring philosophy from multiple perspectives. A framework is suggested to bridge divides and create a groundwork for a philosophical discipline using Integral Methodological Pluralism developed from Integral Theory. A review of the literature on the philosophy of chiropractic is mapped according to the 8 primordial perspectives of Integral Methodological Pluralism. It is argued that this approach to constructing a philosophy of chiropractic will bridge the historical divides and ensure a deep holism by pluralistically including every known approach to knowledge acquisition.

Conclusion

Integral Methodological Pluralism is a viable way to begin constructing a philosophy of chiropractic for the 21st century.

Key indexing terms: Philosophy; Chiropractic; Model, Theoretical; Methods

Introduction

The philosophy of chiropractic has been discussed and debated in the chiropractic profession for more than 100 years. Despite 2 academic and political consensus statements on philosophy,1,2 little progress has been made toward actionable steps in educational standards, curriculum development, continuing education standards, licensing requirements, or the creation of an explicit discipline of philosophy in chiropractic.3 The literature on philosophy has grown in the last 2 decades,3-22 although it has not always met the highest levels of scholastic rigor.3 Part of the problem in developing a scholarly debate and discipline around the philosophy of chiropractic has been political, legal, social, and economic realities that have historically influenced the philosophy development,13,23-25 as well as the political agenda of various factions in the profession.17,19 Other limiting factors include personal worldviews and experiences,7,26,27 cultural perspectives,15,24,28-30 interpretive frames of reference in regard to data collection,31-33 research methodologies,34,35 and clinical approaches.36,37 Ideally, philosophy guides clinical choices, professional development, research foci, political initiatives, policy, doctor-patient interactions, ethics, and education. A sound philosophy should also act as a guide for personal development of the doctor. In the case of a profession focused on health, wellness, and optimal human function, the philosophy should guide the patient's personal development as well.

The profession's founders developed their philosophical positions from unique social, legal, cultural, and personal contexts.23,24,28,38-45 These early philosophical approaches created category errors between internal, subjective psychospiritual development and objective, external healing capacities in tandem with universal first principles and individualized metaphors for healing.10,46-48 This led to testable hypotheses becoming mixed up with philosophical explanations, and body/mind health described in metaphysical and religious terminology.15,19,46-49 For example, DD Palmer, the founder of chiropractic, and BJ Palmer, his son and president of the first chiropractic school for almost 60 years, both equated the body's ability to self-heal with the soul and a universal organizing principle of all matter with God.44,47 The original philosophy they started has its roots in 19th century American metaphysical culture, with roots that go back to a long history of Western esotericism.15,24,29,30,50,51 Sorting through these many tangled issues has been debated in the chiropractic profession since its inception and publicly in the peer-reviewed literature for about the last 20 years. The Palmers' also attempted to explain principles of energy healing associated with chiropractic in scientific language 50 to 100 years before energy medicine developed its own scientific lexicon and research protocols.52-55 These inherent challenges created an internal tension whereby chiropractors were forced to “take sides” against each other while fighting for professional and legal recognition as well as cultural authority in health care and the greater society.

Since the start, chiropractors struggled to survive and disagreed among themselves how best to deal with these philosophical beginnings. That legacy left a fragmented profession without a philosophic discipline. The roots in 19th century metaphysical systems and healing traditions prove well documented15,24,28,29,44,56 and are often described in the early chapters of modern textbooks37,56-60; but no attempts to integrate or come to terms with these early approaches have resulted in the development of a discipline of philosophy for the chiropractic profession.3,12,14,37,61 The philosophical underpinnings and arguments are often described in part as “recycled” ideas from the history of ideas,14,62,63 important primarily for legal purposes23,41,45 or relegated to a century-old simplistic polarity between “straights” and “mixers.”28,64-67 This fragmentation has led to a recent decision by a chiropractic professional governing body, the General Chiropractic Council,68 to dismiss chiropractic's most “defining clinical principle,”69(p37) the vertebral subluxation (VS), and then, after much protest, partly change its stance.70 Vertebral subluxation, acknowledged by most national and international governing bodies, is now referred to by the General Chiropractic Council as a historical artifact.71 Although this latest drama in the historical debate is focused on clinical nomenclature, VS, and research methodologies, it nonetheless relates to philosophy. Several researchers have stressed the need for alternative research paradigms to truly capture the nature of the chiropractic encounter and alternative methods in general.5,7,10,22,33,35,55,67,72 Vertebral subluxation has remained central to the wide-ranging philosophical approaches within the profession and rarely differentiated from those approaches. Without a distinction between clinical encounters, research, and chiropractic's traditional reason for being (VS) from theories and philosophy, this type of confusion and its resulting legal and political consequences prove inevitable.

If philosophy in chiropractic is to develop into a discipline, it needs to transcend and include all elements of the profession from scientifically testable theories, which range from VS to doctor-patient interactions; ethical, legal, and political questions; and all possible ramifications of the chiropractic encounter. This latter area of study would include biopsychosocial and spiritual health and well-being. A philosophy of chiropractic should be able to include science, art (as in chiropractic as a healing art), and ethics or morals. It is in this spirit that I approach the topic in this article.

This article proposes the use of Integral Theory (IT) and its Integral Methodological Pluralism (IMP) to heal the fractures in the chiropractic profession and develop a discipline of philosophy. Integral Theory and IMP can be used to unite all approaches to date in regard to philosophy and lay the groundwork for a comprehensive approach to philosophy. Integral Theory does this by offering an orienting framework that can integrate 4 domains of truth: subjective, objective, intersubjective, and interobjective.73 Such a framework opens the way for a meaningful discussion around the central debates in the philosophy of chiropractic such as the relationship between science and philosophy, the importance of subjective perceptions of health and well-being, the doctor-patient relationship, belief systems, and the impact of social and cultural domains on the profession and the philosophy. Integral Theory also offers a way to explore the more complicated subjects of innate intelligence as a somatobiological and psychospiritual metaphor; the social and cultural history of philosophy and how it relates to chiropractic's emergence; the relationship between quantitative and qualitative research; and the many worldviews and perspectives individual chiropractors, educators, researchers, and philosophers bring to the profession.

Integral Methodological Pluralism is a recent development of IT.73 Integral Methodological Pluralism combines 8 methodological approaches to knowledge acquisition. Combined, these 8 methods include every known domain of knowledge humans have claimed to know. By applying each of these 8 methodologies to the philosophy of chiropractic, a comprehensive pluralism is ensured, whereby no domain of knowledge is left out. The current article defines these methodologies and then examines where they have already been addressed in the literature on philosophy in chiropractic. Some of these methodologies such as empiricism and systems have often been overemphasized and explored in great detail. Other domains such as autopoiesis or the organism's ability to create its own parts and “know” itself from its environment have not been addressed in detail, beyond the biological definitions of innate intelligence and a few specific references in the literature. The methodologies least addressed in the literature are phenomenology, structuralism, ethnomethodology, and cultural anthropology. It is these domains that will be addressed in the second and third articles of this series.

In the first issue of Philosophical Constructs for the Chiropractic Profession, the precursor to the Journal of Chiropractic Humanities, Joseph Donahue suggested that we nurture philosophers in the profession who are well read in a variety of disciplines and educated in philosophy to act as the profession's soul by stirring debate and emotion.15,74 This sentiment is widespread, as is the agreement that a discipline of philosophy in chiropractic is necessary.1,2,3,5,11,12,17,19,37,61 To embrace the wealth of diverse perspectives, include original philosophic premises, adhere to the history of ideas, acknowledge social and cultural forces shaping the profession, and honor the scientific validity claims around clinical entities, a broad framework is required.

Critiques and perspectives on healing chiropractic's divisions

Many approaches attempt to deal with the philosophical challenges at the center of chiropractic's history: to emphasize the clinical encounter and doctor-patient interaction as central5,7,13,75; to reconcile the philosophical approaches by expanding research methodologies to include whole systems34,35; to dismiss all spiritual jargon from the philosophy9,12,49,76,77; to expand on the traditional philosophical premises6,15,16,20,78; to link the philosophical premises to complexity and systems theory46,79-81; to relate it to a hierarchy of values or worldviews and to the highest levels of human function and spiritual development8,15,26,27,44,46,82; and to embrace the wider root metaphors underlying the philosophical premises such as vitalism, holism, naturalism, therapeutic conservatism, and critical rationalism.10,60,80 This latter approach, in particular, has garnered wide support within the profession.83,84

McAulay3 describes the internal debate within the profession along the polemic of 2 methodological approaches, which have not been acknowledged in the wider discussion. These include the “dismissivist approach,” which dismisses the basic premises of the early philosophical models, and the “authoritarian approach,” which accepts those models as the basis of chiropractic's philosophical underpinnings. McAulay called for a third approach, the “critical approach,” which uses basic components of discipline and argument building to achieve consensus and rigor. He uses examples from the literature to make a strong case for the use of critical thinking in developing a discipline of philosophy within chiropractic. Such a method would include 8 core standards of scholastic rigor: clarity, accuracy, precision, relevance, depth, breadth, logical consistency, and intellectual traits. Furthermore, he identifies core intellectual traits such as “intellectual humility, intellectual courage, intellectual integrity, intellectual perseverance, intellectual simplicity, intellectual autonomy, and confidence in reason.”3(p24) McAulay's critical approach is essential to the development of a discipline because it ensures a move forward, “in thinking and knowledge acquisition,”3(p18) and suggests a way to rigorously broaden the dismissivist and authoritarian approaches. It is certainly an approach worth emulating in terms of moving forward. Yet, as a “critical approach,” it really only represents one methodology, albeit a very important one. One methodology is not enough for a comprehensive construction of a discipline of philosophy of chiropractic.

An Integral approach

According to IMP,85 there are at least 8 known methodologies for reproducible knowledge acquisition; and so, it is important to explore in this context. The 8 methodologies are empiricism, phenomenology, structuralism, autopoiesis theory, ethnomethodology/cultural anthropology, hermeneutics, systems theory, and social autopoiesis theory. As will be discussed below, these 8 methodologies taken together represent the most comprehensive or integral ways humans have developed to acquire knowledge. Each one is nonreducible and thus represents a way of knowing that should be included in any philosophy that claims to be holistic. By applying IMP to constructing a philosophy of chiropractic, we can ensure that all perspectives on philosophy are being taken into account even when they disagree. This would expand on McAulay's3 proposal by including his criteria of critical rationalism as the benchmark through which each methodology will be included. The current article will define IMP and suggest ways it can be applied to constructing a philosophy of chiropractic.

This is the first in a series of 3 articles, which propose to build upon the literature and create an explicit framework for the construction of a discipline of philosophy in chiropractic. My goal is not to define what a philosophy of chiropractic is per se, but merely to set parameters allowing for a wide inclusion of ideas across diverse perspectives and philosophical insights. This article draws on IMP and its 8 methodological approaches to gaining knowledge. I propose IMP as a central organizing framework through which all discussions of philosophy in chiropractic can be viewed. The next article will build on some of these methods, examine chiropractic's emergence in the context of a history of philosophy, and consider ways it relates to the historical emergence of the “self.” Finally, a third article will elaborate on more of these methods and apply a developmental constructivist approach to the current arguments on philosophy. The goal of this article and the ensuing 2 articles is not to answer these questions as much as to create a map through which answers can be found and more complete questions can be asked.

Integral theory

Integral Theory was originally developed by American philosopher Ken Wilber over the course of 25 books.86 Integral means “all inclusive,” and that is exactly what the theory does: it includes every aspect of reality humans have claimed to know. The primary method of inclusion is the use of the 3 major perspectives an individual can take to view reality, or the first-, second-, and third-person perspectives.

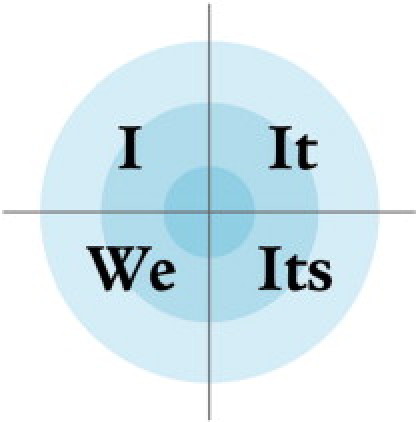

The 4 quadrants were developed to capture the four irreducible dimensions that all organisms have. The 4 quadrants are broken down according to individual (upper quadrants)/collective (lower quadrants) and interior (left-hand quadrants)/exterior (right-hand quadrants). The upper left quadrant (UL) represents the first-person perspective or “I.” This frames the view from within, the internal experience as well as an individual's personal worldview. The upper right quadrant (UR) refers to the view of the individual's body, an objective view, behavior, or “it.” Behavior includes the internal self-organizing capacity of an organism as well as its physical structures and actions. The lower left quadrant (LL) is the domain of collective interiors, or where 2 or more individuals can mutually resonate in shared and felt understanding, or “We.” This is the domain of culture and collective worldviews. The lower right quadrant (LR) is the domain of collective exteriors, or social realities, the shared interactive world space of 2 or more individuals in community, “its.” This is the domain of social and economic realities as well as the internal dynamics of social systems such as professions and clinics. Each quadrant has its own valid claim to truth: subjective truthfulness (UL), objective truth (UR), intersubjective justness (LL), and interobjective functional fit (LR). Integral Methodological Pluralism developed from IT (Fig 1). The quadrants can be understood as perspectives.

Fig 1.

Quadrants. Adapted from Wilber.87(p30)

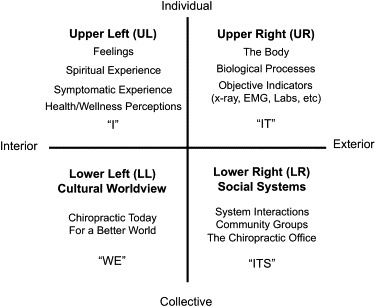

The quadrants represent the four views an individual can look through. In addition, anything can be looked at from all four quadrants (“quadrivium”) or from each quadrant individually (“quadrivia”). This is referred to as the “view through” or the “view from.”87(p48) Thus any individual writing about the philosophy of chiropractic will look at the world through all four quadrants. Each individual views the world through these four lenses or “quadrant-perspectives.”87(p296) That same individual can write about philosophy of chiropractic as an object, from all four perspectives. Thus we can determine whether the philosophy addresses all four dimensions. In order to be complete and truly holistic, it must. Another example is the doctor-patient encounter; the doctor views the world through all four quadrants, containing an I-perspective, a We-perspective, an it-perspective, and an its-perspective.87 The patient also has these four dimensions but can be viewed as an object and looked at from all four perspectives (a quadrivium of views about the patient); the doctor can inquire about the patient’s subjective feelings (UL), examine the patient’s body or actions (UR), and also inquire as to the patient’s cultural (LL) support, such as whether there are supportive people in the patient’s life they can talk to about living a healthy lifestyle, and social (LR) support systems such as family and work (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Four quadrants with chiropractic examples.

Quadrants comprise 1 of the 5 elements of IT. The other 4 are levels, lines, states, and types. Levels refer to an increase in complexity in each quadrant. For example, in the LR quadrant, the chiropractic profession grew from one school and several students to several schools and to the third largest health care profession on the planet. In the UR quadrant, we can refer to increasing complexity of biological organisms from cells to multicelled organisms, to organisms with primitive nervous systems, and to organisms with complex nervous systems. Lines refer to the variety of ways levels can be described in each quadrant. For example, in the LR quadrant, we can discuss the increasing complexity of legal structures, organizational structures, economic structures, etc. In the UL quadrant, we can describe an individual's increasing development of complexity through technical understanding, professionalism, moral compass, and empathic abilities. States refer to the transitory changes in each quadrant. For example, in the UR quadrant, we can discuss the state of health, illness, or wellness of the body. In the UL quadrant, we can discuss states of consciousness: alertness, drowsiness, melancholy, bliss, etc. Types refer to typologies in each quadrant. For example, in the LL quadrant, we can discuss the types of interactions between doctors and patients or between chiropractors. The signature phrase of IT is AQAL (pronounced ah-qwal); and it refers to All-quadrant, All-level, All-lines, All-types, and All-states. For any approach to be integral, it must at least include all levels and all quadrants.

The comprehensive approach that IT takes has proven versatile enough to be applied in several ways,88 throughout dozens of disciplines such as chiropractic,15,27,44,47,78 medicine,89,90 nursing,91,92 health care,93 consciousness studies,94,95 science,96 ecology,97 education,98 and politics,99 across disciplines such as integral psychology,100 which brings together the common elements from several approaches within psychology (an application that may be similar to what is required in chiropractic), and in transdisciplinary ways as in research,101 Integral Life Practice,102 and coaching.103 Integral Theory has developed into its own discipline, Integral Studies, which includes a Master's Degree,104 2 dedicated journals,105,106 a biannual scholarly conference,107 and an academic press.108 The most recent development of IT is referred to as IMP.85

Integral methodological pluralism

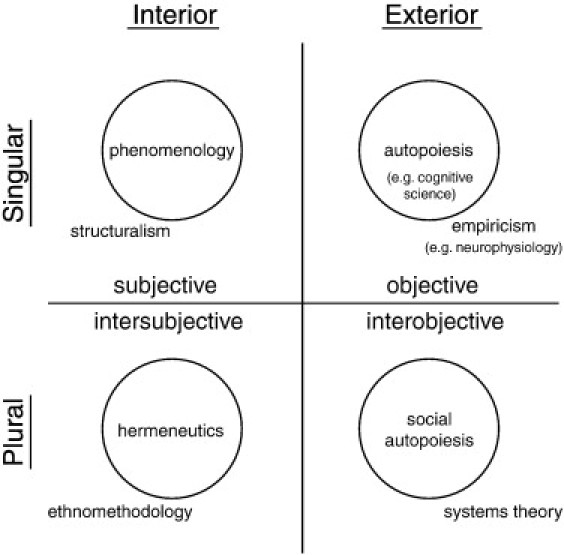

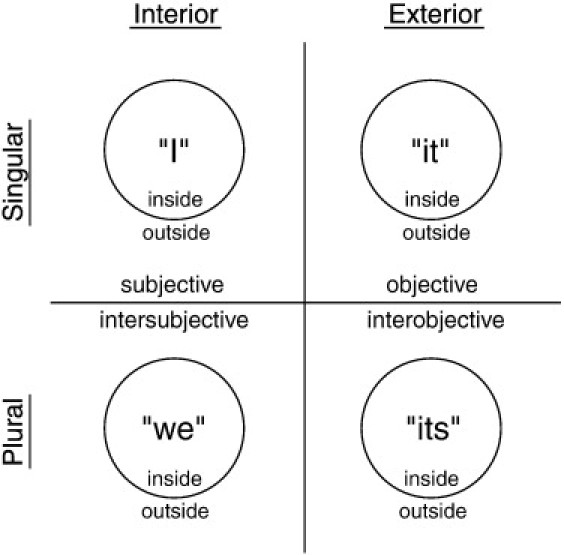

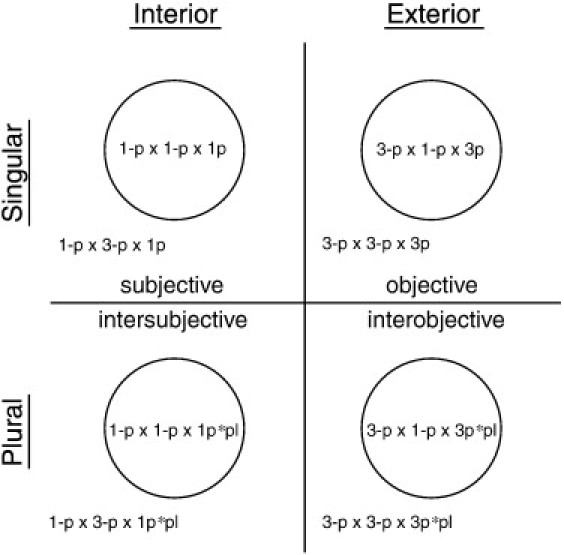

Integral Methodological Pluralism is a postmetaphysical approach to knowledge using at least 8 of the most important methods developed for acquiring valid and reproducible knowledge (Fig 3). It is considered postmetaphysical because it acknowledges that all knowledge, even metaphysics, arises through methods of acquisition. Each method brings forth or discloses an aspect of reality. Thus, metaphysics itself is disclosed through such methods. The 8 methods are derived from dividing each quadrant into an inside and an outside, creating 8 views or perspectives (Fig 4). The views for the UL quadrant are introspection (inside) and structuralism (outside), those for the UR quadrant are brain (inside) and body (outside), those for the LR quadrant are social system (inside) and environment (outside), and those for the LL quadrant are culture (inside) and worldview (outside).88 I argue that IMP (and IT) should be at the foundation of any future discussion of philosophy in chiropractic and central to the construction of a philosophy of chiropractic.

Fig 3.

“8 Major Methodologies,” from Wilber.87(p52)

Fig 4.

“8 Primordial Perspectives,” from Wilber.87(p50)

The real importance of IMP is its inclusionary approach to knowledge through injunctions and practices. Guided by the pluralistic notion that everyone is partially right, it is thus ideal as an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary approach to chiropractic. Without having content, IMP is a framework allowing for 8 verifiable truths, disclosed through 8 distinct methodologies, each nonreducible. For example, one cannot reduce the validity claim of an individual's interior experience (UL) to epiphenomenon of brain states (UR). Each has its own claim to truth.

Integral Methodological Pluralism is a content-free map of reality. Few a priori assumptions about the world are required. This approach opens up many possibilities for a philosophy of chiropractic especially as Wilber posits a limited number of pregivens: Eros, or the inherent drive toward greater unities or wider identification; Agape, or an inherent tendency toward a wider embrace or more inclusion; a morphogenetic field of potential known as the Great Nest of Being and Knowing; as well as some deep structures or tenets of evolution.87,88,109 These limited pregivens can be integrated with the original principles of chiropractic's philosophy, such as the concepts of an Innate and Universal Intelligence, without giving them pregiven ontological status. The inherent drive toward organization posited of individual bodies (UR) and the universe (LR) can be understood as an aspect of the few pregivens Wilber claims. One important application of this approach is how it reframes the discussion of traditional chiropractic principles. For example, rather than dismissing innate intelligence as a heuristic metaphor reminding doctors to be more compassionate or conservative,10,13 keeping it intact as strictly a biological principle,6,16 attributing to it a sort of primal intuitive capacity,27,110 or dismissing it outright as prescientific or prerational,49,111 the concept can be discussed in terms of a deep structure of biological systems as a reflection of an even deeper structure of reality. Critiques can still be strongly presented; but a new wrinkle is allowed into the discussion, one that broadens and deepens the philosophical discourse in a rigorous way.

Integral math

Applying IMP to constructing a philosophy of chiropractic requires philosophers of chiropractic to systematically apply each of the 8 methodologies. Each methodology represents a perspective such as the inside view of the interior of the individual (introspection) or the outside view of the interior of the individual (structuralism). Wilber87 developed Integral Math as a way to account for each of the 8 perspectives. The math is based on perspectives. The 3 main variable notations are described by Esbjörn-Hargens101 (Table 1), the editor of the Journal of Integral Theory and Practice:

first-person (1-p) or third-person (3-p) × inside (1-p) or outside (3-p) × interior (1p or 1p⁎pl) or exterior (3p or 3p⁎pl). When referring to 2nd person realities the “1p⁎pl” variable is used as the third variable since 2nd person is more technically understood as 1st person plural. Likewise “3p⁎pl” refers to interobjective realities. These three variables also represent quadrant × quadrivium × domain (where domain can either be a quadrant or a quadrivium).101(p86)

Table 1.

Integral Math notation definitions

| Notation | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1-p | 1st-person perspective |

| 1p | Interior singular domain |

| 3-p | 3rd-person perspective |

| 3p | Exterior singular domain |

| 1p⁎pl | Interior plural domain |

| 3p⁎pl | Exterior plural domain |

To clarify this notation system, 2 examples will be useful: UL quadrant and LL quadrant. The following examples can then be applied by the reader to the UR quadrant and the LR quadrant (Fig 5).

Fig 5.

Integral Math notations, from Wilber.87(p52)

The UL is the domain of “I” or the interior of the individual, the first-person perspective. This first-person perspective can be viewed from the inside (introspection/phenomenology) or the outside (structuralism). First-person perspectives are written as 1-p; so any time we are referring to a subjective stance, we use 1-p. The view from the inside is also written as 1-p because it refers to a first-person perspective as well. Thus, if I were looking at my own interior thoughts or feelings, it would be notated as 1-p × 1-p. We would then add to this the domain or quadrant we are talking about. In this example of myself looking into my own feelings, because I am an individual, we would write 1p for UL quadrant. Thus, we would have the notation 1-p × 1-p × 1p or first-person perspective (1-p) from the inside (1-p) in the UL quadrant (1p). If however we are referring to using an objective external measure of my interior such as a quality of life survey instrument, a phenomenological survey instrument, or a developmental psychology survey instrument, that would be looking at my interior (1-p) from an objective perspective (3-p). Thus, we are no longer talking about me looking into my own feelings and thoughts, but examining my feelings and thoughts using objective criteria as might be applied by Piaget to study cognitive development112-114 or Kohlberg to study moral development.115 In that instance, the notation would be 1-p × 3-p × 1p, or first-person perspective (1-p) × looking from the outside or third-person perspective (3-p) in the UL quadrant (1p), because we are still talking about the individual's interior or the UL quadrant, “I.”

For another example, let us talk about the interior of the collective in the LL, the domain of culture, shared meaning, and mutual understanding. In that case, we would still be talking about interiors because we are still in the left-hand quadrants; but now, we are talking about collectives. Therefore, if we are describing the interiors, we will stay with the notation of first person because it implies the subjective stance or the view from within (1-p). (If we were in the right-hand quadrants, this first notation would be 3-p, for third-person perspective.) The second part of the notation would remain the same as well, inside (1-p) or outside (3-p) views. (This would also be the case for the right-hand quadrants.) For the third part of the notation, however, we turn the subject into a plural of subjects; we add the term “⁎pl” to denote the domain of LL quadrant (1p⁎pl). The addition of “⁎pl” denotes the first-person plural or “We.” (In the case of the right-hand quadrants, for LR quadrant, the notation is 3p⁎pl; for UR quadrant, the notation is 3p.) This first-person plural would refer to the subjective stance of the culture: What is the overarching worldview of a culture? How do 2 or more individuals feel on the inside when together or resonating with each other? What are the chiropractic culture's shared meanings? All of these elements of meaning, mutual understanding, and shared resonance are depicted in this domain. When we are talking about collective interiors, or the LL, the notation for the inside view is 1-p (first person) × 1-p (inside) × 1p⁎pl (first-person plural aka second-person perspective or “We”); and the notation for the outside view is 1-p (first person) × 3-p (outside) × 1p⁎pl. In the first case, the inside, we are referring to hermeneutics or the study of meanings; in the second case, the outside, we are discussing cultural anthropology or ethnomethodology, or structuralism applied to cultures.

Esbjörn-Hargens101 explains the 8 methodological families along with Integral Math as follows:

The eight methodological families Wilber (2003) identifies are Phenomenology (1-p × 1-p × 1p), which explores direct experience (the insides of individual interiors); Structuralism (1-p × 3-p × 1p), which explores reoccurring patterns of direct experience (the outsides of individual interiors); Autopoiesis Theory (3-p × 1-p × 3p), which explores self-regulating behavior (the insides of individual exteriors); Empiricism (3-p × 3-p × 3p), which explores observable behaviors (the outsides of individual exteriors); Social Autopoiesis Theory (3-p × 1-p × 3p⁎pl), which explores self-regulating dynamics in systems (the insides of collective exteriors); System Theory (3-p × 3-p × 3p⁎pl), which explores the functional-fit of parts within an observable whole (the outsides of collective exteriors); Hermeneutics (1-p × 1-p × 1p⁎pl), which explores intersubjective understanding (the insides of collective interiors); and Cultural Anthropology (1-p × 3-p × 1p⁎pl), which explores recurring patterns of mutual understanding (the outsides of collective interiors).101(p88)

The philosophy of chiropractic has been discussed in terms of most of these perspectives but never in relation to all of the methods simultaneously. This is very important because it is common for authors, philosophers, researchers, and humans in general to be blinded to their own perspective and to engage the world including their own critique or support of a philosophical concept from one dominant perspective.87,116 Divine116 has even found that most people view the world through the lens of one of the quadrants. For example, when a person “comes from” the UL quadrant, he or she wants to know how the situation relates personally to him or her; when a person “comes from” the UR quadrant, he or she wants to know what actions he or she could take or just the facts. When a person “comes from” the LL quadrant, he or she seeks to know how the situation might bring individuals together; and a person “coming from” the LR quadrant wants to know how the situation fits into a bigger system or context. It is easy to skip quadrants that you do not normally focus on and thus miss important elements of reality.

By addressing each perspective and methodology systematically using Integral Math as a way to keep track of each methodological family, a comprehensive approach to philosophy of chiropractic can be entertained that forces each researcher or philosopher to include methods or perspectives that he or she may have missed. The “Discussion” section explores these 8 methods in more detail, while noting where they may be found or not found in the chiropractic literature. Integral Math and the 4 quadrants in general can be used to synthesize the work already done, scan for any missing elements or perspectives,101,117 and then begin to construct a philosophy.

Discussion

The 8 methodologies are described below in relation to the construction of a philosophy of chiropractic. It is important to note that each methodology such as phenomenology or systems theory represents a methodological family. That is, they are not the only methods able to disclose phenomena at each perspective. For example, the perspective of a first-person view of internal experience can be brought forth by contemplation, introspection, meditation, and phenomenology. Integral Methodological Pluralism summarizes all of these approaches or injunctions as phenomenology.87(p51) Each methodology described below represents a family of injunctions, which can also disclose phenomena apprehended at each particular perspective.

Integral Methodological Pluralism is the map. The territory is composed of the principles of chiropractic; critiques of the philosophy; and other elements that philosophy could embrace such as ethics, morals, clinical choices, doctor-patient interaction, research methods, law, politics, and intra- and interprofessional social systems. Once the map is defined, future authors can freely fill in specific details and add any missing pieces. This article is meant to lay the first stage of the groundwork; it is not comprehensive. By simply ensuring that each perspective is mapped, many of the disagreements and debates from the past can be transcended. By allowing for each coexisting truth to be valid, if partial, a great step is made toward unifying the profession. The remaining dilemmas relate to a hierarchy or valuation of the partial truths,26,82,109 which will be addressed in the second and third articles in the series.

Phenomenology (1-p × 1-p × 1p) is a way to observe one's own consciousness systematically. It was first developed by Husserl and has significantly influenced Western philosophy in the last century.118 In terms of the chiropractic encounter in respect to this methodology, when an individual receives a chiropractic adjustment, the internal feelings associated with health, illness, emotional, psychological, or spiritual well-being are validated so long as the individual is truthful. This first-person perspective represents the internal feelings, experiences, beliefs, and states of consciousness associated with the chiropractic encounter. Phenomenology has been suggested by several authors as a valuable contribution to the philosophy and research in chiropractic, and as a valuable qualitative method to research therapeutic effect,119 to break away from the strict scientific rationality,22,75 to understand patients in terms of their personal experience,75 and to understand doctor-patient interactions, practice-based research, underlying factors of behavior,7,8 and the emotional and psychological factors of health.22 Kleynhans5(p165) writes:

The phenomenological approach to chiropractic would have as its purpose to seek a fuller understanding through description, reflection and other phenomenological methods the essence of lived experience of doctor and of patient related to experienced human relations and therapeutic interaction, space, time, body, etc. as lived by them—to reveal the multiplicity of coherent and integral meanings of this phenomenon.5(p165)

Coulter10(p44) has noted how phenomenology is central to the “alternative paradigms” such as hermeneutics and ethnomethodology. As a reaction to the mind/body split inherent in the Western worldview and paramount in biomedicine, phenomenology helps the practitioner to focus on the dignity of the patient's lived experience.10

According to O'Malley,22 phenomenology can be used to distinguish between the art and science of chiropractic. The art is mediated through touch, and touch is based on phenomenological information. O'Malley writes, “Because it is developed through experience, chiropractic art is not open to direct evaluation by the external observer whose experience is different from the chiropractor's.”22(p288) Through touch, the chiropractor gains vital information about the patient's physical and emotional state and can even instill trust.

Applying phenomenology to the philosophy of chiropractic should also extend to the philosophers and practitioners. This self-reflection may also relate to the higher ends of human function, especially regarding extraordinary claims of spiritual experiences, feeling “one with,” “innate,” “universal,” etc. Such systematic introspection has a long history in meditation practices and spiritual traditions such as Zen, Vipassana, and contemplative introspection. It can thus be used as a way to understand aspects of the philosophy of chiropractic that have traditionally been dismissed as mysticism, irrationality, and intuition. In the philosophy of chiropractic, phenomenology or systematic introspection has a tradition going back to DD Palmer and the books he was reading on the cultivation of the inner depths through meditation.15,24,26,53 An overarching philosophy of chiropractic would acknowledge this domain, not only in terms of patient reports and practitioner-patient interaction, but also in regard to the original insights of the Palmers in terms of their own experiential explorations of consciousness.15,27,44,46,78

Structuralism (1-p × 3-p × 1 p) is the systematic and objective tracing of invariant patterns over time. In terms of first-person perspectives, it applies to an individual's development through life. Every individual engages the world from a structure of consciousness without necessarily knowing his or her own structure.87 Wilber points out that an individual can easily experience his or her first-person perspective (phenomenology), but cannot “see” his or her structure of consciousness without an objective measure to do so. Structuralism is another element left out of any philosophy of chiropractic. Structuralism has no correlates in the literature on chiropractic except for a few recent attempts.15,27,44,47,78 Beyond that, the closest thing to this perspective within chiropractic is the objective measures of the patient's internal perceptions of health, wellness, or quality of life such as the Rand-36, the Global Well Being Scale, or the Health Related Quality of Life.120-122 Although those qualitative measures apply an objective view to the individual's interior, they do not necessarily trace a structure of that interior through development.

Structuralism, in this sense, refers to the development of an individual's complexity through life as pioneered by Piaget112 and other developmental psychologists (although Piaget referred to himself as a genetic epistemologist). For example, an individual grows from prerational thinking as a child to rational thinking as an adult. This is a recurring change that can be objectively verified.95,100,112-114 Constructivist developmental researchers have found at least 12 lines of development (moral development, cognitive development, aesthetic development, spiritual development, etc) whereby individuals may move through 5 to 12 levels in their life (prerational to rational to postrational) in each line.95,100 (Recall that levels and lines are 2 of the 5 elements of IT.)

Objectively examining individual interiors is an invaluable addition to constructing a philosophy of chiropractic. It allows for depth and objectivity in terms of understanding the perspectives individuals bring to the philosophy of chiropractic. It might also be applied to patient growth and development over time as well as practitioner-patient communications. There are at least 5 different cognitive structures of consciousness or perspectives in current use to discuss philosophy in chiropractic.26 By acknowledging this, the many perspectives within chiropractic can be integrated. A recent integral biography of BJ Palmer examined his philosophical writings in terms of his development through life along several levels and lines.27 Developmental structuralism is one of the greatest contributions IMP can add to the construction of a philosophy of chiropractic. It is certainly one of the most neglected areas in the literature. It is the topic of the third article in this series.

Autopoiesis Theory (3-p × 1-p × 3p) was developed by Maturana and Varela123,124 to define the most essential characteristics of life; living systems are self-creating and knowing. The simplest example is how a cell creates its own parts and “knows” how to distinguish food from nonfood. This theory expands on concepts of homeostasis, dissipative structures, and chaos and complexity theory as it applies to a living organism. This is a very important point in regard to a philosophy of chiropractic because innate intelligence has been referred to as “a metaphor for homeostasis.”13(p85) As Wijewickrama125 has pointed out, homeostasis as a reductionist concept does not capture the essential elements of life and health. He notes 3 components of a living system—self-will, autopoiesis, and self-organization—and several components of dynamic health, “which depicts increasing levels of organization and complexity in the interconnectedness of living system and environment.”125(p10) Newell81 has described autopoiesis in terms of innate intelligence and the complex dynamic stability of the spine.

Autopoiesis captures other elements of the definition of innate intelligence as well, especially in terms of the organism's ability to self-heal and “to know.”46 Maturana and Varela123 referred to the theory as Autopoiesis and Cognition. Chiropractic research in this domain would focus on the body's ability to self-organize. This view of the interior dynamics of the organism as self-organizing, self-regulating, and intelligent is the core of the philosophy of chiropractic in regard to the living organism. Most chiropractors view this aspect of the philosophy as central; therefore, it is an essential element of any wider philosophical system.

Empiricism (3-p × 3-p × 3p), likely the second most widely embraced perspective in regard to the philosophy of chiropractic, is defined as the acquisition of knowledge through objective evidence. Several authors have suggested how empiricism is not an appropriate methodology as the sole arbiter of the chiropractic encounter. They cite empiricism's inherent limitations of worldview and method. Qualitative approaches32,46,67,71 and alternative research paradigms such as phenomenology,7,8,10 hermeneutics, and ethnomethodology10,22 would be more appropriate to capture chiropractic's unique encounter.

Dismissivists argue that empiricism should be the most weighted component of any philosophy, thus guiding clinical choices, research, and theory.3 From this perspective, objectivity is the only method to truth; and the objectivist perspective becomes the raison d'être of the profession, led by evidence-based research agendas. Villanova-Russell67 relates this perspective to the encroaching hegemony of evidence-based medicine. She writes:

The empiricism of EBM has become the gatekeeper to legitimacy and acceptance in mainstream health care today.… It is becoming clear that in order for alternative medical practitioners to survive, let alone be taken seriously by other health care professions, that they must conform to the standards of medicine even though their underlying philosophies, ontologies, epistemologies and methodologies are incongruent and not amenable to this evaluation.67(p556)

Jones-Harris126 puts it more simply: “embrace empiricism or risk extinction.”126(p74) Jamison33 suggests that practitioners adopt “passive” and “active empiricism”33(p73) as a way to contribute to the philosophy. Passive empiricism is making the best clinical choices based on the available evidence. Active empiricism is to apply study designs to clinical research and produce case reports. Jamison emphasizes the need for the philosophy of science of chiropractic to pave the way for the future of the profession.

Social Autopoiesis Theory (3-p × 1-p × 3p⁎pl) refers to the self-organizing nature of social systems.109,127 Autopoiesis was extended to social systems by Luhmann.127 His reasoning was that, much like living systems, social systems are operationally closed. For living systems, the closure defines the unity, boundaries, and autonomy. For social systems, the operational closure is in terms of communication. Luhmann writes:

At first sight it seems safe to say that psychic systems, and even social systems, are also living systems. Would there be consciousness or social life without (biological) life? And then, if life is defined as autopoiesis, how could one refuse to describe psychic systems and social systems as autopoietic systems? In this way we can retain the close relation between autopoiesis and life and apply this concept to psychic systems and to social systems as well. We are almost forced to do it by our conceptual approach.127(p172)

The social system creates its own parts and communications, and maintains itself. Furthermore, it is populated by living beings (autopoietic organisms). This domain addresses the social, political, and economic pressures inherent to any profession, learning institution, professional organization, or accrediting agency. Historically, a philosophy of chiropractic has been shaped by all these forces.25,28-30,45,56,65 Any element relating to communication and understanding between 2 or more individuals can be applied to this domain, such as doctor-patient interaction as described by Gatterman's75 patient-centered paradigm, as well as the sociological and internal dynamics discussed by Coulter10,128 in terms of clinic, health center, or profession. Following Luhmann's127 logic, the philosophy of chiropractic can extend the philosophy of organism to its social institutions. The profession, governing bodies, individual clinics, and educational institutions would be viewed as self-maintaining, self-organizing, and self-producing systems. This perspective extends the holism of the philosophy into the social sphere.

Systems Theory (3-p × 3-p × 3p⁎pl) was first described by Bertanalanffy129 as a transdisciplinary approach fitting multiple parts together in a system by examining the general principles involved. Chiropractic literature addresses systems in several ways: to expand research methodologies; to include wider perspectives on philosophy in terms of the spinal system81; to contextualize the historical emergence of chiropractic's biological theories130; and to describe the relationships between emergent health of body, mind, spirit, and environment.46,131 Systems can also be applied to other objective analyses of social systems such as historical analysis.28,43,45,56,132 Increasing understanding of how the philosophy of chiropractic is situated in historical, social, political, and economic systems is another useful application of systems theory.

Hermeneutics (1-p × 1-p × 1p⁎pl) is the study of meaning between individuals and in culture. It has been applied to the philosophy of chiropractic in several instances, interpreting objective findings and finding meaning in illness through history-taking,5 as a method to conduct practice-based research and understand behavior,8 and as a method to interpret shared meaning through touch, thereby retaining the essence of chiropractic as a healing art.22 O'Malley22 writes, “Through phenomenology, it is possible to define the nature of experiential knowledge, and through the tools of hermeneutics it is possible to reveal the content of this knowledge to an external observer.”22(p287) O'Malley views the original philosophy of Palmer to be emancipatory for patients in healing of body, mind, and spirit; for practitioners in an embrace of both science and vitalism; and for the profession in the potential to help the world. He writes:

A reconstructed philosophy of chiropractic must provide a complete framework for critical action. Rather than accepting that scientific rationality is the only valid truth for politicolegal legitimation, we must argue for the legitimacy of our own emic understanding of the healing process. This can be done within an inclusive framework using the tools of hermeneutics, phenomenology and critical theory.22(p291)

By examining mutual understandings between different schools of thought within chiropractic, definitions of professional jargon can be situated in a new way. Thus, understanding across the various schools can begin anew. This can also play an important role in the study of the patient-centered paradigm, as it emphasizes the importance of mutual resonance between the doctor and patient both verbally and through touch.8,22,75

Cultural Anthropology (1-p × 3-p × 1p⁎pl) looks to the underlying and repeating structures in cultural worldviews. This perspective has been used in relation to the philosophy of chiropractic in terms of applying phenomenological methods to historical research.133 Twenty years ago, Kleynhans133 called for a “Historical Chiropractic,” where principles and practice can be studied in a historical context.133(p140) One recent approach to bring an objective view to the culture of chiropractic was called for by Moore,132 former editor of Chiropractic History. Moore writes:

What I am calling for is a Social History of Chiropractic that moves outside the circle of internal chiropractic developments and its intramural aspects to a more broadly-gauged history that explores interaction with larger social and cultural developments.132(p60)

Moore132 suggests that this type of Social history can be accomplished by examining broad questions that would bring the historian “deep into the heart of the American experience,”132(p61) to narrow questions such as: how chiropractic has been portrayed historically in comics, the arts, the role of women in chiropractic vs medicine, chiropractic's relationship to religion, sports, the media, etc. Other histories of chiropractic have focused on the impacts of belief systems and worldviews in wider cultural contexts.24,29,30,42 Tracing the structures of worldviews and how they change over time, a genealogy of worldviews, however, is mostly lacking in this regard.15

Studying invariant structures of consciousness or worldviews is akin to structuralism (1-p × 3-p × 1p), but here it applies to the objective view of interiors of collectives. This approach was originally developed by Levi-Strauss134 and in a cultural historical application by Gebser,135 Habermas,136 and Wilber.109,137 Worldviews are pervasive in every culture and could be understood to underlie or be synonymous with paradigms. Although there has been a great deal written about paradigms and chiropractic philosophy,1,10,12,18,34,72,75,79,83,119,138,139 rarely has it taken a genealogical or developmental approach.15 Without examining this deeper methodology in the construction of a philosophy of chiropractic, another important blind spot is traditionally missed. The second article in this series is devoted to this perspective, creating a cultural context for chiropractic's emergence, survival, and current trends.

Conclusions

By offering an Integral framework through which a philosophy of chiropractic can be constructed, possibilities emerge toward integrating disparate worldviews, overcoming inherent contradictions, and furthering professional unity. Including these 8 irreducible perspectives within the philosophy of chiropractic reflects a postmetaphysical stance drawing from ideas and criticisms in premodern, modern, and postmodern approaches to knowledge.

Basic debates plaguing the profession for decades can now be integrated. For example, the decision to focus on Empiricism (3-p × 3-p × 3p) or Autopoiesis (3-p × 1-p × 3p) becomes a moot point, as it becomes obvious that each represents 2 parts of any perspective on the body. When questioning whether chiropractic's philosophy includes Spirit in its definitions of life, health, and well-being, acknowledgment of its importance for individuals (UL) in the context of specific cultural (LL) and social (LR) circumstances becomes relevant, yielding an understanding of associated neurophysiological correlates (UR) such as the “god-spot” in the brain,87 as well as consciousness studies (UL), which was recently described as an important element in exploring the philosophy of chiropractic.83 Furthermore, when an individual uses Phenomenology (1-p × 1-p × 1p), he or she describes internal experiences of Spirit based on his or her particular worldview (Structuralism/Cultural Anthropology). Rather than positing Spirit as a metaphysical given, the philosophy of chiropractic can acknowledge the importance of post-Kantian and post-Heideggerian thinking (modern and postmodern), while accepting the validity claim of the individual's experience.88

Even more specifically, IT and IMP can be used to deconstruct any approach to the philosophy of chiropractic. For example, the system proposed by Coulter,10 developed at Los Angeles College of Chiropractic in the 1990s80 and now widely embraced in the profession,1,2,18,60,74,83,84 posits 6 philosophies that comprise the philosophy of chiropractic: vitalism, holism, naturalism, therapeutic conservatism, humanism, and critical rationalism. A cursory examination determines whether this system meets the criteria of being fully inclusive and postmetaphysical simply by applying the framework. Immediately, the lack of at least 2 perspectives, Structuralism (1-p × 3-p × 1 p) and Cultural Anthropology (1-p × 3-p × 1p⁎pl), becomes apparent in regard to developmental and genealogical approaches to those methodologies.95,112-114,133 Including those would make the system more holistic. A discussion of the pregivens associated with such a system is another way IMP could be useful.

Another partial approach to the chiropractic paradigm was described by Cleveland et al.12 This too will be described in future articles; but as an example, they suggest that a philosophy of chiropractic should dismiss all metaphysical baggage and emphasize the self-healing aspect of living organisms. Like Coulter's10 approach above, this approach is lacking the methodologies Structuralism (1-p × 3-p × 1 p) and Cultural Anthropology (1-p × 3-p × 1p⁎pl), more than anything else. Without explicitly addressing the perspectives of the authors, the perspectives of the theories or paradigms, and the worldviews being considered both historically and in a contemporary way, any approach will be incomplete.

These approaches will be addressed in 2 more articles. The first will address cultural worldviews, and the second will address personal structures of consciousness. As noted above, these are 2 of the greatest blind spots in discussing philosophy of chiropractic. By clarifying these 2 aspects of the map, all other territories can be built upon more easily.

Any attempt to create a discipline of philosophy in chiropractic without coming to terms with IT and IMP will always remain partial, leave something out, and be unable to bring all aspects of the profession on board to engage in the discussion. Great effort is required for philosophers in the profession to flesh out this deep and expansive approach. If it is done well, philosophy can become a meaningful guide to the chiropractic profession.

Funding sources and potential conflicts of interest

Simon Senzon has received from the Global Gateway Foundation a research and writing grant to further the objectives of the Foundation.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Sherri McLendon, MA; Christopher Kent, DC, JD; and Donald Epstein, DC, for editorial suggestions.

References

- 1.Association of Chiropractic Colleges The ACC chiropractic paradigm 1996. http://www.chirocolleges.org/paradigm_scope_practice.html Available from: Accessed September 5, 2010.

- 2.World Federation of Chiropractic Philosophy in chiropractic education. Proceedings from a conference on Philosophy in Chiropractic Education; 2000 Nov 10-13; Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Hayward, CA: Life Chiropractic College West; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McAulay B. Rigor in the philosophy of chiropractic: beyond the dismissivism/authoritarian polemic. J Chiropr Humanit. 2005;12:16–32. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donahue J.H. Palmer's principle of tone: our metaphysical basis. J Chiropr Humanit. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kleynhans A. Developing philosophy in chiropractic. Chiropr J Austr. 1991;21:161–167. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strauss J. Foundation for the Advancement of Chiropractic Education; Levittown, PA: 1999. Toward a better understanding of the philosophy of chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jamison J.R. Chiropractic philosophy versus a philosophy of chiropractic: the sociological implications of differing perspectives. Chiropr J Aust. 1991;21:153–159. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleynhans A.A. chiropractic conceptual framework: part 1: foundations. Chiropr J Austr. 1998;28:91–109. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morgan L. Innate intelligence: its origins and problems. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 1998;42(1):35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coulter I. Butterworth-Heinemann; Woburn, MA: 1999. Chiropractic: a philosophy for alternative health care. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coulter I. Chiropractic philosophy has no future. Chiropr J Austr. 1991;21(4):129–131. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleveland A., Phillips R., Clum G. The chiropractic paradigm. In: Redwood D., Cleveland C., editors. Fundamentals of chiropractic. Mosby; St. Louis: 2003. pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keating J. Philosophy in chiropractic. In: Haldeman S., editor. Principles and practice of chiropractic. McGraw Hill Companies, Inc.; New York: 2005. pp. 77–97. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phillips R. The evolution of vitalism and materialism and its impact on philosophy in chiropractic. In: Haldeman S., editor. Principles and practice of chiropractic. McGraw Hill Companies, Inc.; New York: 2005. pp. 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Senzon S. Self published; Asheville, NC: 2007. Chiropractic foundations: D.D. Palmer's traveling library. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koch D. Roswell Publishing Company; Roswell, GA: 2008. Contemporary chiropractic philosophy: an introduction. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clum G. Philosophy of chiropractic: its origin and its future. J Chiropr Humanit. 2007;14:41–45. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linscott G. The importance of history and philosophy to the future of chiropractic. Chiropr Hist. 2007;27(1):99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cleveland A. Teaching philosophy in chiropractic education today: evolving into the twenty-first century or doing more of the same?. Proceedings of World Federation of Chiropractic 10th Biennial Conference; 2009 Apr 3-May 2; Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Toronto: WFC; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinnott R. Self published; Mokena, IA: 2009. Sinnott's textbook of chiropractic philosophy. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winterstein J. Philosophy of chiropractic: a contemporary perspective. Part 1. ACA J Chiropr. 1994:28–36. [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Malley J. Toward a reconstruction of the philosophy of chiropractic. J Manipulative Phys Ther. 1995;18:285–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rehm W. Legally defensible: chiropractic in the courtroom and after 1907. Chiropr Hist. 1986;6:50–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore J.S. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 1993. Chiropractic in America: the history of a medical alternative. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Villanova-Russell Y. An ideal-typical development of chiropractic, 1895-1961: pursuing professional ends through entrepreneurial means. Soc Theory Health. 2008;6:250–272. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Senzon S. Five levels of consciousness in the chiropractic profession. Proceedings of the International Research and Philosophy Symposium; 2005 Oct; Spartanburg, SC. Spartanburg: Sherman College; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Senzon S. BJ Palmer: an integral biography. J Integral Theory Pract. 2010;5(3):118–136. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wardwell W. Mosby; St. Louis: 1992. Chiropractic: history and evolution of a new profession. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albanese C.A. Yale University Press; New Haven, MA: 2007. Republic of mind and spirit: a cultural history of American metaphysical religion. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fuller R. Pennsylvania University Press; Philadelphia: 1982. Mesmerism and American cure of souls. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kent C. The cult of scientism. Chiropr J. 1995 Available from: http://www.worldchiropracticalliance.org/tcj/1995/mar/mar1995kent.htm. Accessed September 6, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boone W., Dobson G.A. Proposed vertebral subluxation model reflecting traditional concepts and recent advances in health and science: part III. J Vertebr Sublux Res. 1997;1(3):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jamison J. Looking to the future: from chiropractic philosophy to the philosophy of chiropractic. Chiropr J Austr. 1991;21(4):168–175. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hawk C. When worldviews collide: maintaining a vitalistic perspective in chiropractic in the postmodern era. J Chiropr Humanit. 2005;12:2–7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stuber K. Chiropractic research in the postmodern world: a discussion of the need to use a greater variety of research methods. J Chiropr Human. 2007;14:28–33. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cooperstein R., Gleberzon B. Churchill Livingstone; Philadelphia: 2004. Technique systems in chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bergman T., Peterson D. 3rd ed. Elsevier; St. Louis, MO: 2011. Chiropractic technique: principles and procedures. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Palmer D. Portland Printing House; Portland, OR: 1910. The science, art, and philosophy of chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palmer B. Palmer College; Davenport, IA: 1957. History in the making (Vol 35) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paxson M., Smith O., Langworthy S. American School of Chiropractic; Cedar Rapids, IA: 1906. A textbook of modernized chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lerner C. The Lerner report. Unpublished. Palmer College archives; 1952.

- 42.Gaucher-Pelsherbe P. National College of Chiropractic; Chicago: 1994. Chiropractic: early concepts in their historical setting. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geilow V. Fred Barge; La Crosse, WI: 1982. Old dad chiro: a biography of D.D. Palmer founder of chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Senzon S. Self Published; Asheville, NC: 2006. The secret history of chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keating J. A brief history of the chiropractic profession. In: Haldeman S., editor. Principles and practice of chiropractic. McGraw Hill Companies, Inc.; New York: 2005. pp. 23–64. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Senzon S.A. Causation related to self-organization and health related quality of life expression based on the vertebral subluxation model, the philosophy of chiropractic, and the new biology. J Vert Subl Res. 1999;3(3):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Senzon S.A. Self-published; Asheville, NC: 2004. Spiritual Writings of B.J. Palmer. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keating J. Stockton Foundation for Chiropractic Research; Stockton, CA: 1992. Toward a philosophy of the science of chiropractic: a primer for clinicians. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donahue J. DD Palmer and innate intelligence: development, division, and derision. Chiropr Hist. 1986;6:31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hanegraaff W. State University of New York Press; Albany, NY: 1998. New age religion and Western culture: esotericism in the mirror of secular thought. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beck B. Magnetic healing, spiritualism, and chiropractic: Palmer's union of methodologies, 1886-1895. Chiropr Hist. 1991;11(2):11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Senzon S.A. A history of the mental impulse: theoretical construct or scientific reality? Chiropr Hist. 2001;21(2):63–76. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Senzon S.A. Chiropractic and energy medicine: a shared history. J Chiropr Humanit. 2008;15:27–54. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oschman J. Churchill Livingstone; New York: 2000. Energy medicine: the scientific basis. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wisneski L., Anderson L. 2nd ed. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2009. The scientific basis of integrative medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peterson D., Weise G. Mosby; St. Louis: 1995. Chiropractic: an illustrated history. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Redwood D., Cleveland C. Mosby; St. Louis: 2003. Fundamentals of chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leach R. 4th ed. Lippincott; Philadelphia: 2004. The chiropractic theories: a textbook of scientific research. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Haldeman S., editor. Principles and practice of chiropractic. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gatterman M. 2nd ed. Mosby; St. Louis: 2005. Foundations of chiropractic subluxation. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Donahue J. A proposal for the development of a contemporary philosophy of chiropractic. Am J Chiropr Med. 1989;2(2):51–53. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Strauss J. Foundation for the Advancement of Chiropractic Education; Levittown, PA: 1994. Refined by fire: the evolution of straight chiropractic. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jacelone P. The ancient philosophic roots of chiropractic literature. Chiropr Hist. 1989;9(2):45–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Phillips R. The battle for innate: a perspective on fundamentalism in chiropractic. J Chiropr Humanit. 2004;11:2–8. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martin S. Chiropractic and the social context of medical terminology 1895-1925. Technol Cult. 1993;34(4):808–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baer H. Divergence and convergence in two systems of manual medicine: osteopathy and chiropractic in the United States. Med Anthropol Q. 1987;1(2):176–193. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Villanueva-Russell Y. Evidence-based medicine and its implications for the profession of chiropractic. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:545–561. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.General Chiropractic Council Guidance on claims made for chiropractic vertebral subluxation complex. http://www.gccuk.org/files/link_file/Guidance_on_claims_made_for_the_chiropractic_VSC_18August10.pdf Available from: Accessed September 6, 2010.

- 69.Haavik-Taylor H., Holt K., Murphy B. Exploring the neuromodulatory effects of vertebral subluxation. Chiropr J Aust. 2010;40:37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 70.GCC revises guidance on claims made for the vertebral subluxation complex. Chiropractic Economics Online. http://www.chiroeco.com/chiropractic/news/10150/52/gcc-revises-guidance-on-claims-made-for-the-vertebral-subluxation-complex-/ Available from: Accessed September 15, 2010.

- 71.Kent C. An analysis of the General Chiropractic Council's policy on claims made for the vertebral subluxation complex. Foundation for Vertebral Subluxation. http://www.mccoypress.net/subluxation/docs/kent_gcc_subluxation_analysis.pdf Available from: Accessed September 5, 2010.

- 72.Kleynhans A., Cahill D. Paradigms for chiropractic research. Chiropr J Aust. 1991;21:102–107. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Esbjörn-Hargens S. An overview of integral theory: an all-inclusive framework for the 21st century [resource paper no. 1]. Integral Institute 2009;1-24. http://integrallife.com/files/Integral_Theory_3-2-2009.pdf Available from: Accessed October 24, 2010.

- 74.Donahue J. Are philosophers just scientists without data? Phil Constructs Chiropr Prof. 1991;1(1):21–24. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gatterman M. A patient-centered paradigm: a model for chiropractic education and research. J Am Chiropr Med. 1995;1(4):371–386. doi: 10.1089/acm.1995.1.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Keating J. Beyond the theosophy of chiropractic. J Manipulative Phys Ther. 1989;12:147–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Koch D. Has vitalism been a help or a hindrance to the science and art of chiropractic? J Chiropr Humanit. 1997;6:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Senzon S. An integral approach to unifying the philosophy of chiropractic: B.J. Palmer's model of consciousness. J Conscious Evol. 2000;2:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Callendar A. The mechanistic/vitalistic dualism of chiropractic and general systems theory: Daniel D. Palmer and Ludwig von Bertalanffy. J Chiropr Humanit. 2007;14:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Phillips R., Coulter I., Adams A., Traina A., Beckman J. A contemporary philosophy of chiropractic for the LACC. J Chiropr Humanit. 1994;4:20–25. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Newell D. Concepts in the study of complexity and their possible relation to chiropractic health care: a scientific rationale for a holistic approach. Clin Chiropr. 2003;6:15–33. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Astin J. Does the chiropractic profession need a common conceptual framework?. Proceedings of the World Federation of Chiropractic Conference on Philosophy in Chiropractic Education; 2000 Nov 11-12; Fort Lauderdale, Fla; Toronto: WFC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chapman-Smith E. (ed.). Philosophy, practice and identity: why agreement is needed and what is being done. In: The chiropractic report 2003;17 (Vol. 3):1-8.

- 84.WHO guidelines on basic training and safety in chiropractic. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2005. p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wilber K. Excerpt B: the many ways we touch: three principles helpful for any integrative approach. http://www.kenwilber.com/writings/read_pdf/84 Available from: Accessed September 18, 2010.

- 86.Wilber K. Shambhala; Boston: 1999-2000. The collected works of Ken Wilber. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wilber K. Shambhala; Boston: 2006. Integral spirituality. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Esbjörn-Hargens S., Wilber K. Toward a comprehensive integration of science and religion: a postmetaphysical approach. In: Clayton P., Simpson Z., editors. The Oxford handbook of religion and science. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Astin J., Astin A. An integral approach to medicine. Altern Ther Health Med. 2002;8(2):70–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.George L. Integral medicine: an AQAL based approach. J Integral Theory Pract. 2006;1(2):38–59. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fiandt K., Forman J., Megel E., Pakieser R., Burge S. Integral nursing: an emerging framework for engaging the evolution of the profession. Nurs Outlook. 2003;51(3):130–137. doi: 10.1016/s0029-6554(03)00080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dossey B. Integral and holistic nursing. In: Dossey B., Keegan L., editors. 5th ed. Jones & Bartlett; Sudbury, MA: 2008. pp. 3–46. (Holistic nursing: a handbook for practice). [Google Scholar]

- 93.Goddard T. Integral healthcare management: an introduction. J Integral Theory Pract. 2004;1(1):449–458. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wilber K. An integral theory of consciousness. J Consciousness Stud. 1997;4(1):71–92. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Combs A. Paragon House; St. Paul, MN: 2009. Consciousness explained better: towards an integral understanding of the multifaceted nature of consciousness. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Koller K. An introduction to integral science. J Integral Theory Pract. 2004;1(2):237–249. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Esbjörn-Hargens S., Zimmerman M. Random House/Integral Books; New York: 2009. Integral ecology: uniting multiple perspectives on the natural world. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Murray T. What is the integral in integral education? From progressive pedagogy to integral pedagogy. Integral Rev. 2009;5(1):96–134. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wilpert G. Integral politics: an integral third way. J Integral Theory Pract. 2004;1(1):72–89. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wilber K. Shambhala; Boston: 2000. Integral psychology: consciousness, spirit, psychology, therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Esbjörn-Hargens S. Integral research: a multi-method approach to investigating phenomena. Constr Human Sci. 2006;2(1):79–107. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wilber K., Patten T., Leonard A., Morelli M. Random House/Integral Books; New York: 2008. Integral life practice: a 21st century blueprint for physical health, emotional balance, mental clarity, and spiritual awakening. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hunt J. Transcending and including our current way of being: an introduction to integral coaching. J Integral Theory Pract. 2009;4(1):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 104.JFKU.edu [Internet]. Pleasant Hill, CA: John F. Kennedy University; c2010 [cited 2010 Sep 18]. Available from: http://www.jfku.edu/Programs-and-Courses/College-of-Professional-Studies/Integral-Studies.html.

- 105.SunyPress.edu [Internet]. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; c2010 [cited 2010 Sep 18] Available from: http://www.sunypress.edu/p-5108-journal-of-integral-theory-and-practice.aspx.

- 106.Integral-Review.org [Internet]. Bethel, OH: ARINA, Inc.; c2010 [cited 2010 Sep 18] Available from: http://www.integral-review.org/.

- 107.IntegralTheoryConference.org [Internet]. Pleasant Hill, CA: John F. University;c2010 [cited 2010 Sep 18]. Available from: http://www.integraltheoryconference.org.

- 108.SunyPress.BlogSpot.com [Internet]. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. c.2010 [cited 2010 Sep 18]. Available from: http://sunypress.blogspot.com/2010/03/integral-theory.html.

- 109.Wilber K. Shambhala; Boston: 1995. Sex, ecology, spirituality: the spirit of evolution. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Palmer B. Palmer School; Davenport, IA: 1949. The bigness of the fellow within. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Weiant C. Chiropractic philosophy: the misnomer that plagues the profession.

- 112.Piaget J. The principles of genetic epistemology: collected works. London: Routledge; 1997.

- 113.Cook-Greuter S. Making the case for a developmental perspective. Ind Commercial Training. 2004;36(7):275–281. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Kegan R., Lahey L. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2009. The immunity to change: how to overcome it and unlock the potential in yourself and your organization. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kohlberg L. Harper and Row; San Francisco: 1981. The philosophy of moral development: moral stages and the idea of justice. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Divine L. Looking at and looking as the client: the quadrants as a type structure lens. J Integral Theory Pract. 2009;4(1):21–40. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cook-Greuter S. AQ as scanning and mapping device. J Integral Theory Pract. 2006;1(3):142–157. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Husserl E. Harper & Row; New York: 1965. Phenomenology and the Crisis of Philosophy. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Miller P. Phenomenology: a resource pack for chiropractors. Clin Chiropr. 2004;7:40–48. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Hawk C., Dusio M., Wallace H., Bernard T., Rexroth C. A study of reliability, validity, and responsiveness of a self-administered instrument to measure global well-being. Palmer J Res. 1995;2(1):15–22. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hoiriis K., Owens E., Pfleger B. Changes in general health status during upper cervical chiropractic care: a practice-based research project. Chiropr Res J. 1997;4(1):18–26. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Blanks R., Schuster T., Dobson M. A retrospective assessment of network care using a survey of self rated health, wellness, and quality of life. J Vertebr Subluxat Res. 1997;1(4):11–27. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Maturana H., Varela F. D. Reidel Pub. CO; Dordrecth: 1980. Autopoiesis and cognition: the realization of the living. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Maturana H., Varela F. Shambhala; Boston: 1987. The tree of knowledge. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wijewickrama D. Chiropractic and cybernetics. J Chiropr Humanit. 2001;10:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Jones-Harris A. The evidence-based case report: a resource pack for chiropractors. Clin Chiropr. 2003;6:73–84. [Google Scholar]

- 127.Luhmann N. The autopoiesis of social systems. In: Geyer F., van der Zouwen J., editors. Sociocybernetic paradoxes. Sage Publications; London, UK: 1986. pp. 172–192. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Coulter I. Sociological studies of the role of the chiropractor: an exercise in ideological hegemony? J Manipulative Phys Ther. 1991;14(1):51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Bertalanaffy L. George Braziller; New York: 1968. General system theory: foundations, development, applications. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Senzon S. What is life? J Vertebr Subluxat Res. 2003:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Beckman J., Fernandez C., Coulter I.A. Systems model of health care: a proposal. J Manipulative Phys Ther. 1996;19(3):208–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Moore J. Reflections on healing, orthodoxy, and a new direction for chiropractic history. Chiropr Hist. 2009;29(1):55–65. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Kleynhans A. Historical chiropractic: part 1: delineation. Chiropr J Aust. 1990;20:139–142. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Levi-Strauss C. Beacon Press; New York: 1971/1949. The elementary structures of kinship. [Google Scholar]

- 135.Gebser J. Ohio University Press; Athens, OH: 1949. The ever-present origin. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Habermas J. Beacon Press; Boston: 1985. The theory of communicative action: life world and system: a critique of functional communicative action (vol 2) [Google Scholar]

- 137.Wilber K. Up from Eden: a transpersonal view of human evolution. Wheaton, OH: Quest Books; 2007/1981.

- 138.Kleynhans A.A. Chiropractic conceptual framework: part 4: paradigms. J Chiropr Austr. 1999;29:129–136. [Google Scholar]

- 139.Leach R., Phillips R. Philosophy: foundation for theory development. In: Leach R., editor. 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2004. (The chiropractic theories: a textbook of scientific research). [Google Scholar]