Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this article is to offer aspects of a conceptual model that can be applied as an organizational instrument for aiding preclinical and clinical chiropractic students to develop a thorough understanding of their roles among the next generation of health care providers for the 21st century.

Discussion

It is necessary for chiropractic physicians to comprehend the basis of the society-culture-personality model as an organizational device in the health care institution. The structure of the family and the socialization process as conceptual components of the model may allow an enriched understanding of their interrelationships and thereby could expand and provide quality care for patients as a whole.

Conclusion

The society-culture-personality model has the potential for synthesizing the features of the socialization process and the family in relation to the institution of health care. This model is particularly appropriate for the needs of the next generation of health care professionals (chiropractic physicians, physicians, dentists, nurses, and osteopathic physicians) who may not have had the chance to be exposed entirely to the behavioral sciences in health care.

Key indexing terms: Chiropractic, Behavioral sciences, Family, Socialization process

Introduction

At present, the behavioral sciences have been accorded an essential, even vital place in the education of future chiropractic physicians, physicians, dentists, nurses, administrators, and directors. Indeed, the collaborative inclusion of the behavioral sciences and other disciplines in the professionalization process of health care workers has been well documented by the former dean of Harvard Medical School. He asserted that “collaboration . . . could be a universal starting point for accelerating our slow march toward global equity in health care.”1

An important criterion, therefore, in the teaching of behavioral sciences to health care students for their future professional roles as caregivers is to place the diverse body of descriptive and empirical findings within some type of theoretical framework. This context should incorporate essential concepts and theories from the various disciplines, for example, sociology, psychology, and anthropology, in such a way as to show the interconnectedness of central issues surrounding health care as an institution in societies. Indeed, to be ill is not merely a medical problem; it is also a social event involving more than 1 person and changing the sick person's customary relationships with others in the family, in the community, and ultimately in society.

This article will attempt to present aspects of a conceptual model that can be used as an organizational device for assisting preclinical and clinical chiropractic students to develop a greater comprehension of their future professional roles as health care practitioners in communities and societies nationally and transculturally. We shall present aspects of the society-culture-personality (SCP) model and the health care institution from the perspectives of (a) the socialization or learning process especially as health behavior, illness behavior, and the sick role are all learned behaviors; and (b) the institution of the family as the family is “the unit of medical care because it is the unit of living.”2 The use of this model has been presented elsewhere.3-6

The socialization process of the SCP model and the health care institution

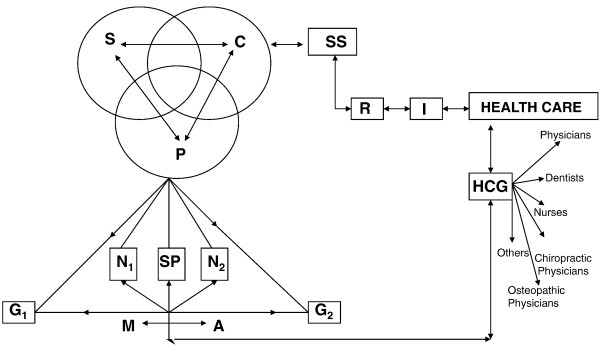

The SCP model forms an interlocking social system (Fig 1). By definition, a social system is a pattern of expected behaviors associated with a certain position in society. As roles become highly complex structures, they are called institutions (ie, ways of taking care of basic human needs). In brief, institutions are socially approved patterns of behavior. Health care and the family are viewed as institutions in American society. The various institutions of a society are crescive in nature and have a strain of consistency, which simply means that they develop over time and they are all interrelated. Health care as an institution, therefore, cannot be fully understood unless it is examined in itself as well as in relation to other institutions such as the family, social welfare, government, education, religion, and other organizational structures in the society. A society, from one perspective, can be viewed as falling somewhere between two polar pure types, ideal types or mental constructs as either gemeinschaft or gesellschaft in orientation, or perhaps rural and urban (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Society-culture-personality (SCP) and the health care institution. SCP, global village; S, society; C, culture; P, personality; N1, nature or heredity; N2, nurture or environment; G1, gemeinschaft; SP, socialization process; G2, gesellschaft; M, marginality; A, anomie; SS, social systems; R, role; I, institution; HCG, health care givers.

The SCP model from a macroscopic perspective represents the global village, a nation, a community, an institution or group (Fig 1). There are a multitude of subsystems, comparable with subsystems in the human body, operating in any of these aggregates.

For purposes of analysis, we will isolate a simple subsystem, namely, the personality subsystem. This subsystem involves the socialization or learning process (SP); nature (N1), which is the genetic basis, and nurture (N2), or environment, which is the social or cultural basis in any society between the gemeinschaft (G1) and the gesellschaft (G2) dichotomy (Fig 1).

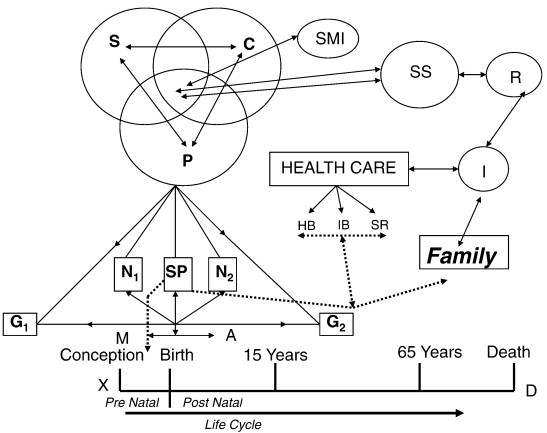

The genetic (or natural) basis of personality is the combination of traits that results from the person's unique constellation of genes. The genetic basis (N1) of personality represents only potentiality. These potentialities, when developed under the influence of the total environment in which the individual's orientation takes place, are shaped into a personality. Hence, the formation of the personality is one of integrating the individual's experience with his or her physical qualities to form a mutually adjusted, functioning whole. This takes place in childhood and adolescence and results in the development of distinctive physical as well as emotional responses. The personality system, therefore, is the totality of the actor's personal needs in the cultural world in which he or she interacts. Within the personality system rests the self-concept. The self-concept involves the assumption that personalities act according to the way they perceive themselves (their self-concept) and according to the way they perceive the social situation. Social situations are all forces acting upon the individual at any given moment in time. The assimilation process is most crucial in the personality system. The finished product is acquired through socially meaningful interaction (SMI)—the nucleus of the cell of society. The SMI is linked to socialization, a learning process in a social environment (N2), where the value-attitude system (VAS) of a culture is internalized (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Society-culture-personality (SCP): Socialization and health care. S, society; C, culture; P, personality; N1, nature; N2, nurture; G1, gemeinschaft; G2, gesellschaft; SP, socialization processes; M, marginality; A, anomie; SS, social systems; R, role; I, institution; X, conception; D, death; HB, health behavior; IB, illness behavior; SR, sick role; SMI, socially meaningful interaction.

The socialization process is linked to the health care system through health behavior, illness behavior, and the sick role. These behaviors are learned behaviors. They permeate the life cycle from the moment of conception until natural death (Fig 2). The life cycle can be viewed in terms of the prenatal (from conception [X] to birth) and postnatal from birth to natural death (D) (Fig 2).

In the prenatal stage, the brain and nervous system develop and form an intricate network. This network can be interrupted by environmental factors such as fetal exposure to alcohol or drugs used by the mother. If such interruption occurs, certain ailments can affect approximately 10 000 U.S. babies a year. Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) can lead to serious mental retardation caused by maternal alcohol abuse. Research indicates the fact that 1200 to 8000 FAS babies are born annually in the United States.7

During the socialization process in the life cycle, children born into poverty struggle against serious odds to achieve optimal health and well-being. Lifestyles and health behaviors are developed by the community in which the child may live. For instance, persistent exposure to poverty and other social problems, family violence, and alcohol abuse increases a child's chances of adopting similar behavioral patterns.7 On the whole, children socialized in poverty may be at greater risk for poor health. Children who are born to single mothers who may be homeless, and may have poor educational attainment, may put the infant at similar risk for inadequate health care and poor access to preventive and health care services. As a result, the mother and the infant may both be affected by insufficient health care in impoverished neighborhoods and societies.8

In the socialization process of the postnatal stage of the life cycle, it is to be noted that living in communities with high levels of air pollution is directly related to an increased incidence of respiratory illnesses in children. Children who live in certain environments surrounded by nuclear power plants and/or toxic waste sites are at greater risk of various illnesses especially as their bodies are still in the process of development. These children may experience extreme challenges in receiving adequate health care because of lack of health insurance.8

Indeed it is to be noted that people who live in poverty receive suboptimal health care. For example, children who are poor are twice as likely to be in poor health, and they have a greater probability of being hospitalized for short periods of time (Fig 2).9 In the postnatal stage of the life cycle (Fig 2), the socialization process in relation to the health care institution is linked to several behavioral science theories such as Cooley's looking-glass self.10 This theory and others are most applicable to therapists in the health care system. In the area of gerontology, the activity and disengagement theories play vital roles in the lives of the elderly irrespective of the location of the society and culture on the continuum between the gemeinschaft and gesellschaft dichotomy (Fig 2).

The socialization process in relation to the health care institution is most helpful in the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of several illnesses and disorders. The following illustrate just some of the social and psychological issues confronting Americans. For example, 10% of the U.S. adult population experiences a depressive disorder. Additionally, anxiety disorders are a most prevalent group of psychiatric illnesses among children and adults. Other common disorders include dyslexia, which is revealed when a child learns to read, and antisocial behavior, which involves behaviors from lying and bullying to vandalism and homicide. It should be noted that antisocial behaviors, however, are most prevalent in boys who tend to inflict physical harm on others. Eating disorders, however, are ailments that are most common in American teenage girls and young women as only 5% to 15% of anorexics or bulimics and 35% of binge eaters are male.9

Given the above, the concept of the socialization process in the behavioral sciences in health care is directly related to the SCP model especially from the perspective of poverty in the United States and around the world. According to William Spencer, the following statistics give us an indication how widespread the poverty crisis is in the United States. He asserted that:

37.3 million people live in poverty in the United States. This includes 10 percent of families . . . The child poverty rate in the U.S. is 18%, between two and four times higher than other major industrialized nations. One in six children in the U.S. lives in poverty. The poverty rate for America's population over 65 stands at 9.7 percent, or one in ten seniors. At 16 million, the greatest number of poor persons are non-Hispanic white Americans.11

The same study shows that poverty, however, is not only a socioeconomic issue facing the United States but also the international community as well. The findings demonstrate that:

An estimated 1.4 billion of the world's people live in extreme poverty, on under $1.25/day. Over 2.6 billion people live on $2 a day. Countless others live just above the poverty line and remain highly vulnerable to crises. 40 million people were pushed into hunger in 2008 due to higher food prices. One quarter of all children in developing countries are at risk of experiencing long-term effects of undernourishment. Over 1 billion people do not have access to sanitation, and over 30,000 children die of preventable diseases every day.11

We shall now consider a synthesis of additional concepts and theories within the institutions of the family and health care in relation to the SCP model.

The family, health care, and the SCP model

There is no human society in which some form of family does not exist. The family is the most permanent of all social institutions and fundamental to the socialization process of the individual. The family is, without question, the oldest and most prevalent of all human institutions. The family is related to health by the fact of biological inheritance of some disease entities. Diseases such as sickle cell anemia, Rh factor incompatibility, and tendencies to diabetes, tuberculosis, and poor dentition are examples of entities passed by the family through the gene pool. Heredity is responsible for darker teeth with translucent appearance. Teeth that are darker lose their enamel easily when compared with normal teeth and are more likely to wear down to the gum line.8 Indeed, the “family is the unit of medical care because it is the unit of living.”2

The family has several functions. For example, it acts as a biological and social heritage from one generation to another. However, one undisputed function of the family is the socialization of its nucleus into the society. In general, the term socialization is used to describe the ways in which the individual learns the values, beliefs, and roles that underwrite the social system in which he or she participates.

The sick role developed in the socialization process is most important in physical and mental disorders. For example, a patient may act out his or her sick role in relation to the members of a health care team (chiropractic physicians, physicians, administrators, nurses, the chaplain, his family, osteopathic physicians) and the other members of society in the manner in which he or she has internalized this role from infancy (Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Society-culture-personality (SCP): The family and health care. S, society; C, culture; P, personality; N1, nature; N2, nurture; G1, gemeinschaft; G2, gesellschaft; M, marginality; A, anomie; SS, social systems; R, role; I, institution; SP, socialization processes; SR, sick role; SMI, socially meaningful interaction.

Family roles can be seriously affected by illness, bringing about a reshaping of roles and role responsibilities. Role reversal between parents is a common one, in which the breadwinner's responsibility is switched and patterns of child care may need to change. For example, if a longshoreman loses his leg through an on-the-job accident, he will no longer be able to act out his occupational role as the use of both legs would be necessary for him to perform his work successfully. His wife will now become the breadwinner and he becomes the homemaker. These transitions can be sources of confusion in identity for children during the early developmental stages especially if there had been prior inadequate role performances on the part of the parents toward their children.

The family also influences health care through its effects on nurture (N2) or environment of the individual (Fig 3). A family of 10 who is crowded into an inadequate home without sufficient heat and enough finances for balanced meals will be more likely to become ill, and the individual's view of health will reflect his or her experience under such living conditions.

In an early study, Komarovsky examined family life in Newark during the Great Depression of the 1930s to determine the impact the father's unemployment had on familial roles.12 She found that the loss of the breadwinner's role sometimes had serious and tragic effects on the man's self-esteem and on his formerly affectionate and authoritative relationships with his wife and children. In such cases, husbands viewed themselves as humiliated and came to feel neurotic because of so much free time and nothing to do; wives were bitterly disappointed at their husbands' socially defined economic failure.

Given the role of the family in relation to health care, we will turn our attention now to the structure of the family to grasp a better understanding of the interdependence of these two institutions in the SCP model (Fig 3).

Structure of the family in health care

Every social institution has some sort of structure or framework that helps to put concepts or purposes of the institution into the world of action so that it can serve the interest of society and the members who compose it. The family as a social institution has its framework or structure within which it can carry out the purposes for which it exists. Most individuals are members of two families during their lives. The first is the family of origin (orientation) in which our earliest experiences take place. The second is the family of marriage (or procreation) in which we may enact the role of parent. It is within the network of familial relationships that we develop our attitudes and values toward health and illness. Attitudes are tendencies to feel and act in certain ways. Values, on the other hand, are measures of desirability. The structure of the family can be classified as shown in Fig 3.

The family as we have noted earlier is the most universal of all human institutions. It varies widely in structure from the consanguinal type (ie, extended kin groups, which include a wide variety of related persons) to conjugal families consisting simply of an adult pair (male and female) and their children. The conjugal family acts as a source of “refuge” in mass society—a place where the individual may engage in genuinely personal relationships in a world that is largely impersonal.

In the past, many authors have given us a description of different types of families. Sorokin, for example presents 3 types: namely, the compulsive, the contractual, and the familistic (Fig 3). In the compulsive family, the bond holding members together is not love but force and the relationship is based on exploitation, cruelty, and deprivation. The contractual type brings profit and advancement to the participants but is devoid of love and hatred. The familistic type is based on mutual love between the spouses, and it is characterized by devotion, sacrifice, solidarity, sharing, permanence, and stability. Sorokin feels that the 3 types of families have been present regardless of one's society but have changed in proportion with time. The contractual family, however, is the largest one in today's Western world.13

The type of family a person comes from can help us understand the behaviors of the patient and members of the family toward the sick person. For example, in severe coronary cases, increasing demands are made on the family to adjust their customary routines to the patient's needs. One can expect, therefore, that if the family type was close (familistic), in which each member was concerned about the others prior to the illness, then there could be a greater willingness for members of the family to adjust their roles to help the sick person. On the contrary, if the family type was contractual and/or compulsive, then the family members would be less willing to make the sacrifices to aid the sick individual.

Structure within the institution of the family plays an essential role in the way stress is handled during a sudden crisis. The outcome of such a crisis will depend upon the type of familial relationship prior to the episode. For example, stress within a family may lead to infectious illness. Research done at the Family Medicine Unit at Harvard Medical School have demonstrated rather clearly that:

. . . Common crises such as death of grandparents, change of residence, a loss of a father's job, and a child's being subjected to unusual pressure, occur four times more frequently in the two week period prior to the appearance of streptococcal infection than in the two weeks afterward.14

The same studies have shown that:

Age, intimacy of contact, and family organization influenced the susceptibility to streptococcal infection. Children of school age were most susceptible, and a spread of infection to other family members sharing the same bedroom was likely. Chronic family disorganization also was correlated with susceptibility to infection.14

Additional research demonstrates that “streptococcal and staphylococcal infections are family disorders, and successful management responses requires consideration of the family group.”15

Another kind of crisis in which the type of family plays an important role is the biological inheritance factor. If one learns that he or she is a cause of disease that affects children or learns that he or she is a recipient of a disease of a familiar nature, this knowledge can bring about complicated emotional problems in family interaction. For example, the birth of a deformed infant may be accompanied by a guilt reaction on the part of both parents. One can speculate about the emotional disturbances of the family in the specific case of muscular dystrophy, which is carried by the female and attacks the male. The need of a parent to deny knowledge about such discomforting facts is understandable; however, there is a tendency for the parent to believe the facts must be disproved and to continually seek out advice in order to get different answers. At this stage of the crisis, there is a great need to see the family as a unit of treatment. Whether or not the family is viewed as such will depend partially upon the type of familial relationships prior to the episode.

Another important role of the family is the patient-physician relationship concerning the care at the end of life. Though many health care professionals are often uncomfortable discussing death and dying with their patients and families and believe such discussion would be too difficult emotionally and thus ineffective for the patient and family, a recent study has shown that the reverse is true. Almost 90% of caregivers (ie, the family) believe such collaboration was not stressful, and 20% found it beneficial.16 The burden of caregiving on the family is often substantial. Family members who are themselves elderly, ill, and disabled often perform caregiving. It can be the equivalent of a full-time job for 20% of caregivers and result in further financial burden. The average annual costs for caregiving in the United States can range from $3 billion to $6 billion.17

These stressors often lead families to seek long-term care (LTC) placement. Several patient and caregiver characteristics are predictors of future placement. Caregivers who are older (>65 years of age) who feel a greater sense of burden are more likely to have their loved one in a LTC facility.18 Although many caregivers experience symptoms of anxiety and depression (15% to 20%) prior to placement in an LTC facility, these symptoms did not change after placement, particularly true for spouses.19 Two recent studies found that caregivers often experience a sense of relief after the passing of a loved one, when it was preceded by ongoing suffering and significant burden to the caregiver.20,21 One study suggests that, in addition to the known risk of psychiatric morbidity of caregiving, there is a 60% higher risk of caregiver death when compared with non-caregiver controls.22 In recognizing the burden of caregiving, Rabow et al recently proposed 5 areas of opportunities for caregivers to be of service to the family. These are (a) promote communication, (b) promote advanced care planning and decision making, (c) support home care, (d) demonstrate empathy for patients and their families, and (e) participate in family grief and bereavement. In providing compassion and empathy, caregivers have much to offer to patients and their families.

Conclusion

With the inclusion of the behavioral sciences component in the National Board Examinations, many professional schools in the health care institution have included sociology, psychology, and anthropology in the training of their students. However, the extreme shortage of qualified social scientists, who are capable of relating the behavioral sciences to the health care institution, makes it difficult to meet the needs of graduate and professional schools everywhere. In view of this problem, this article has synthesized 2 conceptual frameworks, the socialization process and the institution of the family, with the SCP model. The SCP model is an organizational device for integrating the components of the socialization process and the family in relation to the health care institution. This model is especially adapted to the needs of future health care professionals (chiropractic physicians, physicians, dentists, nurses, osteopathic physicians, and others) who may not have had the opportunities to be fully introduced to the behavioral sciences in health care.

We have synthesized the socialization process through society, culture, and personality. We have noted that the learning process commences from the prenatal and continues into the postnatal through natural death. The socialization process is essentially a learning process related to health behavior, illness behavior, and the sick role of the patient.17

We have noted that the family is the most permanent of all social institutions and it is the basic socializing agency for the individual. The sick role, internalized during the socialization process within the family, involves an individual's response to his or her illness. The patient acts out the sick role in relation to the chiropractic physician, physician, dentist, nurse, the family, and the other members of society. In addition to being the major socializing agency, the family also influences health care through its functions of nurture (environment) and nature (biological inheritance).

The structure of the family can also help the health care giver understand the behavior of the patient and his or her family's background. Whether the family is compulsive, contractual, or familistic will have an effect on a patient's attitude and perception of the illness. The structure of the family influences familial interactions and relationships as well as the way in which the family is able to handle stressful situations.

Even though only a few concepts and theories have been examined within the socialization process and the institution of the family, the SCP model can be used to relate other major concepts and theories such as social processes, social class, disease prevention, epidemiology, and the community to the SCP model, in so far as these concepts are relevant to the education and delivery of care by future health professionals.

Funding sources and potential conflicts of interest

The authors reported no funding sources or conflicts of interest for this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all those who contributed to this research project: Loyola University Chicago, Harvard Medical School, Northeastern Illinois University, and members of Loyola University Chicago's Jesuit community. Tamil Selvi Chakrapani assisted in converting the digitized format. Dr. Marcel Fredericks thanks the Health Service Research Training Committee of the National Institutes of Health for the Public Health Service Fellowship at Harvard University Medical School.

References

- 1.Martin JB. Collaborative skills pay off locally, globally. Harvard Medical School; Boston, MA: 2006. p. 4. [dean's report] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson HB. Patients have families. Commonw Fund. 1948 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fredericks M. Teaching nursing students the interactional aspects of social concepts. J Hosp Prog. 1971;52:30–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fredericks M, Miller S, Odiet J, Fredericks J. Toward an understanding of cellular sociology and its relationships to cellular biology. Education. 2003;124:237–256. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fredericks M. First steps in the sociology of health care: a synopsis and catalyst for change. Loyola Res Serv 1998;1-2:22-42, 389-403.

- 6.Fredericks M, Hang L, Ross M, Fredericks J, Lyons L. Chiropractic physicians: toward a synthesis of electronic medical records and the society, culture, personality model in the new millennium. J Chiropr Humanit. 2008;15:2–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kluger J. Masters of denial. Time. 2003;161:84–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Satcher D, Pamies RJ. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 2006. Multicultural medicine and health disparities. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stermer D. Through the ages. Time. 2003;161:82–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vander Zanden JW. 4th ed. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1996. Sociology: the core. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spencer W. Fighting poverty to build peace. St. Peter's Church Bulletin. 2009;40(7):4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Komarovsky M. Arno-Press; New York, NY: 1971. The unemployed man and his family. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sorokin PA. EP Dutton and Company; New York, NY: 1941. The crisis of our age: the social and cultural outlook. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haggerty RJ, Alpert JJ. The child, his family and illness. Post Grad Med J. 1963;34:228–229. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1963.11694837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alpert JJ. The functions of the family physician. Conn Med. 1975;32:664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Wolfe P, Emanuel LL. Talking with terminally ill patients and their caregivers about death, dying, and bereavement: is it stressful? is it helpful? Arch Int Med. 2004;164:1999–2004. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.18.1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabow MW, Hauser JM, Adams J. Supporting family caregivers at the end of life. JAMA. 2004;291:483–491. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA. 2002;287:2090–2097. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.16.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulz R, Belle S, Czaja S, McGinnis K, Stevens A, Zhang S. Long-term care placement of dementia patients and caregiver health and well-being. JAMA. 2004;292:961–967. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulz R, Beach SR, Lind B. Involvement in caregiving and adjustment to death of a spouse. JAMA. 2001;285:3123–3129. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.24.3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schulz R, Mendelsohn AB, Haley WE. End-of-life care and the effects of bereavement on family caregivers of persons with dementia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1936–1942. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality. JAMA. 1999;282:2215–2219. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.23.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]