Abstract

Objective

To assess tumor markers in advanced laryngeal cancer.

Design

Marker expression and clinical outcome.

Setting

Laboratory.

Patients

Pretreatment tumor biopsies were analyzed from patients enrolled in the Department of Veterans Affairs laryngeal cancer trial.

Main Outcome Measures

Expression of p53 and Bcl-xL in pretreatment biopsies was assessed for correlation with chemotherapy response, laryngeal preservation, and survival.

Results

Higher rates of larynx preservation were observed in patients whose tumors expressed p53 versus those that did not (73% versus 53%, p = 0.0304). Higher rates of larynx preservation were also observed in patients whose tumors expressed low levels of Bcl-xL versus those that expressed high levels (90% versus 60%, p = 0.02). Patients were then categorized into 3 risk groups (low, intermediate and high risk) based on their tumor p53 and Bcl-xL expression status. We observed that patients whose tumors had the high risk biomarker profile (low p53 and high Bcl-xL) were less likely to preserve their larynx than patients whose tumors had the intermediate risk (high p53 and low or high Bcl-xL) or low risk (low p53 and low Bcl-xL) biomarker profile. The larynx preservation rates were 100%, 76% and 54% for the low, intermediate and high risk groups respectively (Fisher exact 0.039).

Conclusions

Tumor expression of p53 and Bcl-xL is a strong predictor of successful organ preservation in patients treated with induction chemotherapy followed by radiation in responding tumors.

INTRODUCTION

Advances in chemotherapy, radiation therapy and surgical techniques have improved the outlook of patients with advanced larynx cancer allowing larynx preservation and improved quality of life. Up to this point, however, we have been unable to predict which tumors are likely to respond to chemotherapy and radiation, and which tumors will be resistant and persist. To better understand the biology of chemotherapy and radiation response, analysis of the phenotype of tumor cells by genetic and proteomic approaches has been underway for the last several years. Studies in the literature have examined the prognostic significance of various biomarkers including cell cycle regulators, members of the pro-apoptotic family, angiogenesis markers, and proliferation markers in head and neck squamous cell cancer1–8. Results have been quite mixed reflecting the multitude of factors that contribute to the complex tumor biology as well as the heterogeneity of head and neck cancers in terms of biology, site, stage, and prognosis.

p53 plays a central role in pathways responsible for maintaining cellular integrity. The p53 network is activated when cells are damaged or stressed. Upon activation, the p53 protein can lead to cell cycle arrest and DNA repair or it can cause programmed cell death. Wild-type p53 protein binds to DNA and regulates the expression of various target genes including p21, GADD45, leading to blockade of cell cycle progression and initiation of repair9. Similarly, p53 mediated transactivation of genes including Bax, Noxa and PUMA promote cell death by apoptosis10, 11. Approximately 50% of head and neck tumors have a p53 mutation. p53 is one of the molecular determinants regulating the response to chemotherapy. We have previously shown that head and neck tumor cell lines with mutant p53 were more sensitive to cisplatin than wild-type p53 lines2. Others have shown p53 mutations to be associated with poor response to chemotherapy12.

Bcl-xL is a member of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 protein family13–15. Bcl-xL binds proapoptotic proteins such as Bak, Bad and Bim via the BH3 domain and prevents these proteins from initiating apoptosis at the mitochondrial membrane15, 16. We have previously reported that Bcl-xL is overexpressed in 75% of HNSCC17. Overexpression of anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL is frequently associated with chemotherapy and radiation resistance13, 18. Therefore, it is possible that anti-apoptotic proteins like Bcl-xL, Bcl-2 might be important components of response to cisplatin therapy in conjunction with p53.

Determining biomarkers that predict treatment response as well as identifying low and high risk groups will help select appropriate treatment options for patients and limit unnecessary patient morbidity due to ineffective treatment approaches. In addition, identification of mechanisms of treatment resistance will allow development of novel treatment approaches tailored to tumor biology. Here, we seek to determine the predictive and prognostic significance of selected biomarkers in tumors from advanced laryngeal carcinoma patients enrolled in the VA Laryngeal Cancer study19. We evaluated pretreatment biopsy specimens from stage III/IV larynx cancer treated on the chemotherapy arm of the study. We constructed tissue microarrays with triplicate tumor and normal specimens. We determined the concordance between whole section and tissue microarray immunostaining. We investigated whether expression of biomarkers was predictive of chemotherapy response, organ preservation, and survival.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Department of Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Cancer Trial

Pretreatment paraffin embedded tumor specimens were obtained from patients enrolled in a randomized study of stage III/IV larynx cancer comparing conventional surgery and radiation to induction chemotherapy (using 3 cycles of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil) followed by radiation in responding tumors19.

Tissue Microarray Construction

Formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded pretreatment tissue samples were used for the construction of tissue microarrays from the VA study. A pathologist marked representative areas of tumor and normal on hematoxylin and eosin stained sections from each tissue block. To account for tumor heterogeneity, three 0.6 mm tumor tissue cylinders were punched from marked tumor area of each tissue block and transferred to a recipient block. Cores were also taken from adjacent normal tissues as internal negative controls. After construction of the array, sections were cut and immunostained.

Immunohistochemistry

The tissue microarrays were stained for p53 (Ab-6, clone DO-1 Cat #MS-187, Lab Vision, Fremont, CA) and Bcl-xL (Ab-2, clone 7D9, Lab Vision, Fremont, CA). For whole sections, p53 and Bcl-x staining was performed as described previously3, 17. Slides were deparaffinIzed and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval was performed by heating the slides to 92°C for 20 minutes in antigen retrieval buffer (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). The slides were allowed to cool for 20 minutes at room temperature, rinsed in PBS and incubated with peroxidase block (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) for 5 minutes at room temperature. Non-specific binding sites were blocked with 1.5% horse serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) in PBS for 30 minutes. The slides were incubated with primary antibody (p53 1:100, Bcl-xL 1:100) diluted in blocking buffer for 1 hour, washed in PBS, and incubated with biotinylated anti-mouse IgG (ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 30 minutes, washed again, and incubated with avidin/biotin-conjugated peroxidase for 30 minutes, all at room temperature. Color was developed with diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma, Saint Louis, Missouri). The slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, mounted with cover slips. Affinity purified mouse IgG2a (Sigma, Saint Louis, Missouri) was used as a negative control.

Immunohistochemical Interpretation

All slides were read independently by two pathologists, who were blinded to the clinical outcomes of the patients. Each core was evaluated for the percentage of tumor cells stained on a scale of 1 to 4 with 1: <5% staining, 2: 5–20% staining, 3: 21–50% staining and 4: 51–100% staining.

Statistical Analysis

Associations between molecular biomarkers and categorical clinical outcomes were examined using a Chi square test or a Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate. For p53 immunostaining, staining proportion scores were averaged and values less than 2 (<5% tumor cell staining) were considered to be low expression. For Bcl-xL immunostaining, scores were averaged and values less than 3 (<21%) were considered to be low expression. For combined marker analysis, the patients were grouped into three categories based on their tumor p53 and Bcl-xL expression status and prior laboratory studies that showed a difference in cisplatin sensitivity of cultured head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines based on p53 and Bcl-xL expression20. The first biomarker group was comprised of patients whose tumors expressed low p53 (< 5% stain proportion) and high Bcl-xL (> 20% stain proportion). The second biomarker group consisted of patients whose tumors expressed low levels of both p53 and Bcl-xL (p53: <%5; Bcl-xL <21% stain proportion). The remainder of the patients were categorized in the third biomarker group (high p53 and high or low Bcl-xL). Time to event analyses for both survival and larynx preservation was based on Kaplan Meier techniques. In all cases a two-sided alpha level of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Associations of the results obtained with whole sections and tissue microarray sections were evaluated using McNemar test for paired data.

RESULTS

p53 and Bcl-xL immunostaining

Nuclear p53 expression was scored in 86 evaluable pretreatment biopsies from patients of the chemotherapy arm of the study. p53 expression was observed in 52.3% of tumor specimens. Bcl-xL expression was evaluated in 70 pretreatment tumor specimens. Bcl-xL staining was localized in the cytoplasm of tumor cells. Some staining was also observed in the stromal lymphocytes and surface epithelium but only tumor cell staining was scored. High Bcl-xL expression was observed in 71.4% of tumor specimens.

Correlation of p53 immunostaining in whole sections and tissue microarray cores

There is concern that tissue microarrays may not adequately represent the marker expression in a tumor as compared to what can be assessed using whole sections. We compared p53 staining averages between whole tissue sections and tissue microarray sections. Sixty-eight subjects had paired pretreatment whole tissue and tissue microarray p53 results. There was no statistically significant difference between the mean p53 staining using whole section immunostaining compared to immunostaining on tissue microarray (p=0.2647, paired t-test). Similarly, a comparison of the data using p53 averages classified as high or low showed disagreement in only 11 subjects. Using the McNemar test for paired data we see that the difference in classification is not statistically significant (p=0.2266) and the Kappa statistic tells us that the agreement is ‘significantly better than chance alone’ (p<0.0001). In sum, the p53 immunostaining results were highly correlated and were not statistically different between whole sections and tissue microarray samples. The data supports the use of tissue microarrays for biomarker identification in pretreatment biopsy samples.

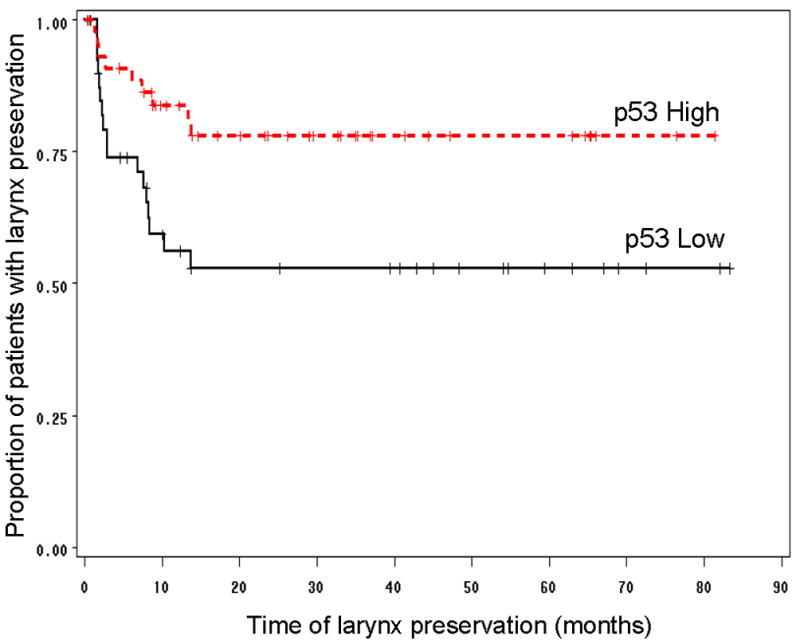

Correlation of p53 immunostaining and clinical outcome in patients of the chemotherapy arm

After two cycles of induction chemotherapy, patients with tumors expressing high p53 had a similar rate of response (partial or complete) compared to patients with tumors expressing low p53 (86% vs. 78%; p=0.38). However, we observed a significantly higher rate of larynx preservation (yes/no) among patients who had high p53 tumor expression (80%) as compared to patients with low p53 tumor expression (58.5%). The relative risk of laryngectomy among patients with low p53 expression in their tumors was 2.10 times that of patients with p53 high expression tumors (p=0.0366). Furthermore, patients with p53 high tumors enjoyed a clinically impressive and significantly longer larynx preservation time than those with p53 low tumors (p=0.0155, Figure 1). There was no difference in overall survival and disease-free survival in patients according to pretreatment p53 immunostaining results (p=0.70 and p=0.98 respectively, Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier graph showing that for patients in the chemotherapy arm of the study (n=86), those that had high p53 tumors had a significantly longer larynx preservation time, as compared to patients with low p53 tumors (Log-Rank p=0.0155).

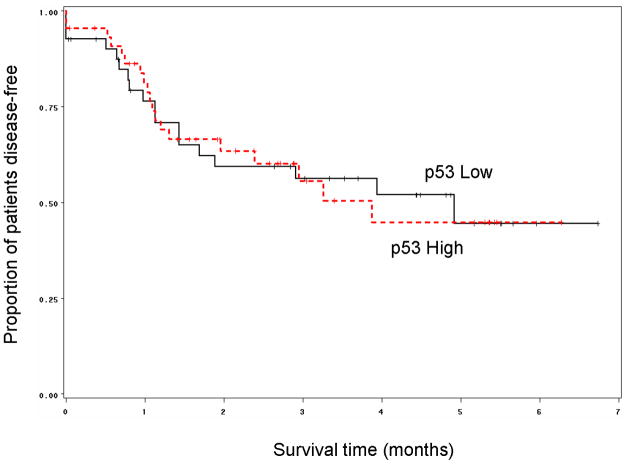

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier graph showing that no difference in disease-free survival was observed based on p53 expression status (Log-Rank p=0.98) when pretreatment specimens of patients were analyzed (n=86)

Correlation of Bcl-xL immunostaining and clinical outcome measures

Fifty of the 70 tumors from patients enrolled on the chemotherapy arm displayed high Bcl-xL staining. Patients whose tumors expressed low levels of Bcl-xL enjoyed significantly higher rate of larynx preservation and longer laryngeal preservation than patients whose tumors expressed high levels of Bcl-xL (p = 0.02, Figure 3). In fact, 18 out of 20 patients (90%) whose tumors expressed low levels of Bcl-xL preserved their larynx as compared to 30/50 patients (60%) whose tumors expressed high levels of Bcl-xL (p = 0.02). Patients were 50% more likely preserve their larynx if their tumors expressed low Bcl-xL. There was no statistically significant difference in overall or disease-free survival according to Bcl-xL expression (p = 0.55 and p=0.73 respectively, Figure 4). We also explored the relationship between larynx preservation and survival of patients in the chemotherapy arm of the study and found that larynx preservation and survival were not related. This is thought to be due to the therapeutic effectiveness of early salvage surgery that was planned for all patients in the trial who had non-responding tumors.

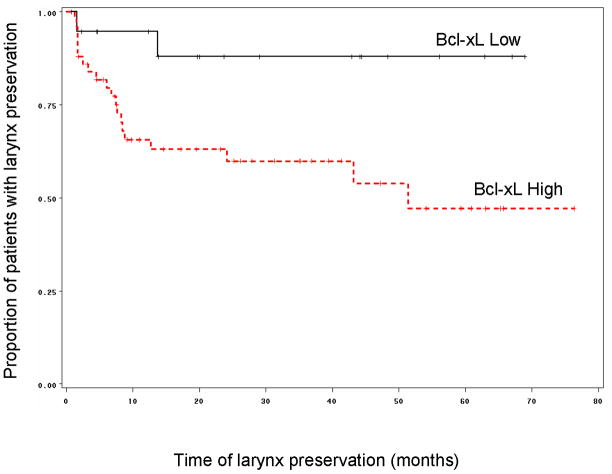

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier graph showing that for patients in the chemotherapy arm of the study (n=70), those that low expression of Bcl-xL had a significantly longer larynx preservation time, as compared to patients with tumors having high Bcl-xL expression (Log-Rank p=0.02).

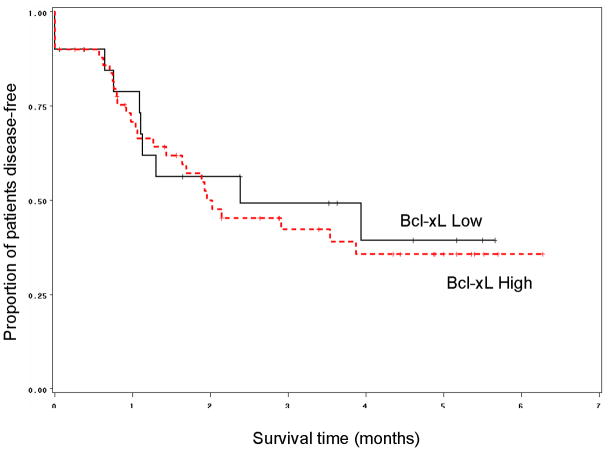

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier graph showing that no difference in disease-free survival was observed based on Bcl-xL expression status (Log-Rank p=0.73) when pretreatment specimens of patients were analyzed (n=70)

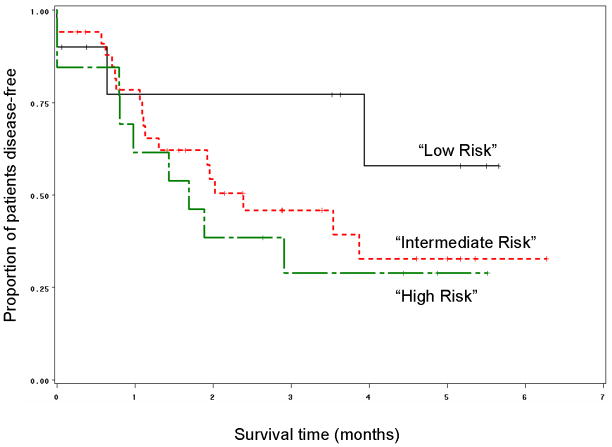

Combined biomarker analysis

Both p53 and Bcl-xL expression results were evaluable in 57 pretreatment biopsies of patients enrolled on the chemotherapy arm of the study. Patients were grouped into three categories based on their tumor expression of p53 and Bcl-xL as described in the statistical analysis section. All patients (10/10, 100%) with low p53 and low Bcl-xL expression in their pretreatment biopsies preserved their larynx. In contrast, patients with tumors expressing low p53 and high Bcl-xL were 16 times more likely to have a laryngectomy. In this group, more than half (7/13, 54%) underwent laryngectomy. Thus, together these markers can define a low (low p53, low Bcl-xL) and high risk (low p53, high Bcl-xL) biomarker group. Those patients whose tumors expressed high p53 constituted an intermediate risk group in which 26/34 (76%) of patients had salvage surgery (p=0.01 for trend; Fishers exact=0.039). Logistic regression analysis showed that a patient was 4 times more likely to require a laryngectomy if the patient had an intermediate risk biomarker profile compared to low risk biomarker profile. Similarly, a patient with the high risk biomarker profile was 4 times more likely to undergo laryngectomy as compared to a patient with the intermediate risk profile. Time to laryngectomy was also significantly shorter in the high risk group as compared to the other two groups (p=0.03, Figure 5). Chemotherapy response was higher in patients with the low risk biomarker profile. All patients with tumors having the low risk phenotype responded to chemotherapy (partial or complete response) as compared to 81.8% (27/33) in the intermediate risk group and 66.7% (8/12) patients whose tumors had the high risk phenotype (p=0.0641: test for trend). The median survival of patients enrolled on the chemotherapy arm of the study, whose tumors displayed the low risk phenotype, was 48 months as compared to 28 months for the patients with intermediate risk profile and 22 months for patients with high risk phenotype (p=0.57). Although there was no statistically significant difference in disease-free survival among the groups (p=0.34), patients with low risk biomarker profile fared better than patients in the other two groups (Figure 6).

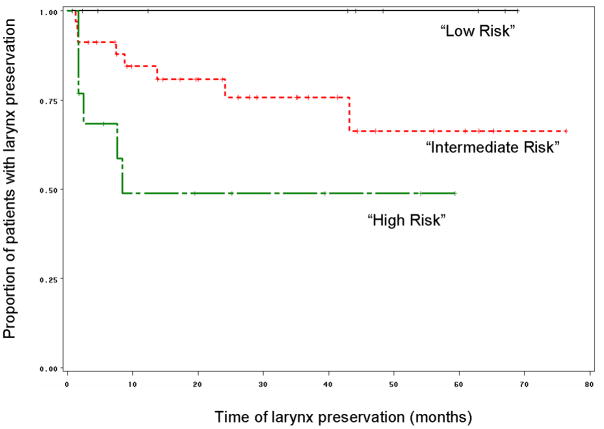

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier graph showing that patients with tumors displaying the “high risk” phenotype (tumors having low p53/high Bcl-xL) had significantly shorter time to laryngectomy as compared to patients with “low risk” (tumors with low and low Bcl-xL) and “intermediate risk” (tumors with high p53 and low or high Bcl-xL) phenotype (Log-Rank p=0.03) (n=57).

Figure 6.

Kaplan-Meier graph showing that no significant difference in disease-free survival was observed between patients in the three risk biomarker profile groups (Log-Rank p=0.34), when pretreatment specimens of the chemotherapy arm were analyzed (n=57).

DISCUSSION

Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) shows a high incidence of p53 suppressor gene alterations; consequently, the loss of p53 functionality plays an important role in pathogenesis and progression of these malignancies21. Although many studies have been performed to assess the role of p53, the results have been contradictory regarding prevalence and the biological and clinical influence on tumor behavior22–25. This could be attributable to differences in methodological approach, small sample size and mixed cohorts of tumors and patients. In this study, pretreatment tumor biopsy samples from patients enrolled in the Department of Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Study Group #268 clinical trial were analyzed for p53 and Bcl-xL expression. The major advantages of our patient group include the uniform site (larynx) and uniform stage (Stage III & IV) of tumors, randomization to induction chemotherapy plus radiation given in a standardized protocol as well as the availability of reliable long-term outcome data (10 years).

The data presented herein strongly suggests that in advanced laryngeal cancer, tumor expression of p53 defines a subset of patients with a high likelihood of larynx preservation. The present study expands upon previous reports that show an association of high p53 expression with larynx preservation3 and another report indicating that low tumor expression of Bcl-xL, a protein that blocks apoptosis, is associated with larynx preservation in patients treated with induction chemotherapy followed by radiation therapy17. Although high p53 and low Bcl-xL expression are each independently significantly associated with larynx preservation, in the present study we demonstrate that the interaction of Bcl-xL with low p53 expression more accurately identifies those patients with the best and worst probability of larynx preservation. In fact, using the markers together, we are able to define low, intermediate, and high risk biomarker phenotypes. Specifically, combined low tumor expression of p53 and Bcl-xL is a stronger predictor of larynx preservation than is high p53 expression irrespective of Bcl-xL status. This observation was initially unexpected given the association between overexpression of p53 and larynx preservation. The low risk (10/57, 17.5%) and the high risk biomarker phenotype (13/57, 22.8%) each represent a small but significant proportion of patients whereas the intermediate risk biomarker phenotype represents a much larger proportion of patients (34/57, 59.6%). Thus the high rate of larynx preservation (76%) in the intermediate risk biomarker group accounts for the statistically significant association between larynx preservation and p53 expression.

In this trial we did not find a statistically significant relationship between the markers and survival. We suspect that this is because prompt surgical treatment for non-responders in larynx cancer is itself a highly effective therapeutic option and thus, these patients do not have worse prognosis than those who respond to induction chemotherapy. Nevertheless it is of interest that the survival curves do begin to separate out into three groups that are suggestive of a minor effect on survival. Possibly in a larger cohort this minor effect might become more impressive.

The excellent larynx preservation observed in the low risk biomarker phenotype group is consistent with results published in head and neck cancer cell lines that show that tumor cells with low (wild type) p53 and low Bcl-xL undergo apoptosis in response to cisplatin20. Low expression of the apoptosis-blocking protein, Bcl-xL, in tumors should allow DNA damage induced apoptosis when p53 is wild type. Most tumor cells with wild type p53 do not express nuclear p53 due to the short half-life of this protein. Thus, we conclude that the favorable outcome of patients whose tumors have low p53 and low Bcl-xL is in likely due to induction of apoptosis by cisplatin. Tumor cells harboring mutant p53 should not be able to arrest and repair DNA damage induced by cisplatin. These tumor cells are also resistant to p53-dependent apoptosis and likely undergo cell death by mitotic catastrophe26. In fact, patients whose tumors express high levels of p53 (intermediate risk) have intermediate but reasonably favorable rates of larynx preservation. Finally, in this model, the most cisplatin-resistant phenotype would be tumor cells with wild type p53 and high levels of Bcl-xL. In fact, head and neck tumor cell lines selected for cisplatin resistance in vitro harbored both wild type 53 and high Bcl-xL20. In the present study, low tumor expression of p53 combined with high tumor expression of Bcl-xL defines a patient subset with a low likelihood of larynx preservation. We are in the process of completing p53 mutation analysis in these specimens but based on our data thus far, the overwhelming majority of the tumors with low p53 expression have wild type and presumably, functional p53. Although, these p53 analyses should confirm the predictive models proposed in this paper, it remains that p53 expression by itself or combined with Bcl-xL expression is a potent predictive marker.

Further study is needed to determine if these models hold true in the setting of other treatment protocols with different induction regimens, concomitant treatment approaches using chemotherapy and radiation, and other head and neck tumor sites like oropharynx. Work is underway to evaluate the predictive ability of these markers in a successful protocol in advanced laryngeal cancer recently completed at the University of Michigan27. In addition, promising biomarker studies supporting the role of p53 and Bcl-xL expression in predicting outcome have been recently obtained in a clinical trial of advanced oropharynx cancer patients (Worden FP, Kumar B, Bradford CR, Carey TE et al, manuscript submitted). In this latter trial, additional factors such as human papillomavirus and expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor appear to have prognostic significance as well.

Our results also suggest that novel agents that target Bcl-xL in the setting of cells with wild type p53 would be good candidates to overcome cisplatin resistance in larynx cancer. Our group has reported the use of a novel therapeutic agent, (−)-gossypol, which targets Bcl-xL in both in vitro and in vivo head and neck cancer models20, 28, 29. Similarly, others are developing agents which target the cell survival proteins in a variety of cancers30, 31. Clearly, defining the molecular mechanisms responsible for tumor cell resistance to standard therapies and designing targeted therapy to overcome the resistant phenotype is the future of cancer therapy and may, someday, improve survival in these patients.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by NIH NCI grants R01 CA83087 (Dr. Bradford) and by the University of Michigan Head and Neck SPORE grant (P50 CA97248) and Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA46592).

Footnotes

Presented as a talk on Friday August 18, 2006 at the American Head and Neck Society 2006 Annual Meeting & Research Workshop, Chicago, IL (August 17–20, 2006)

References

- 1.Bradford CR. Predictive factors in head and neck cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1999;13:777–785. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford CR, Zhu S, Ogawa H, et al. P53 mutation correlates with cisplatin sensitivity in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma lines. Head Neck. 2003;25:654–661. doi: 10.1002/hed.10274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford CR, Zhu S, Wolf GT, et al. Overexpression of p53 predicts organ preservation using induction chemotherapy and radiation in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. Department of Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Cancer Study Group. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;113:408–412. doi: 10.1016/s0194-5998(95)70077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akervall J, Brun E, Dictor M, Wennerberg J. Cyclin D1 overexpression versus response to induction chemotherapy in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck--preliminary report. Acta Oncol. 2001;40:505–511. doi: 10.1080/028418601750288244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teknos TN, Cox C, Barrios MA, et al. Tumor angiogenesis as a predictive marker for organ preservation in patients with advanced laryngeal carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:844–851. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200205000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bentzen SM, Atasoy BM, Daley FM, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor expression in pretreatment biopsies from head and neck squamous cell carcinoma as a predictive factor for a benefit from accelerated radiation therapy in a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5560–5567. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karsai S, Abel U, Roesch-Ely M, et al. Comparison of p16(INK4a) expression with p53 alterations in head and neck cancer by tissue microarray analysis. J Pathol. 2007;211:314–322. doi: 10.1002/path.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schimming R, Reusch P, Kuschnierz J, Schmelzeisen R. Angiogenic factors in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity: do they have prognostic relevance? J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2004;32:176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Oijen MG, Slootweg PJ. Gain-of-function mutations in the tumor suppressor gene p53. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:2138–2145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villunger A, Michalak EM, Coultas L, et al. p53- and drug-induced apoptotic responses mediated by BH3-only proteins puma and noxa. Science. 2003;302:1036–1038. doi: 10.1126/science.1090072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oda E, Ohki R, Murasawa H, et al. Noxa, a BH3-only member of the Bcl-2 family and candidate mediator of p53-induced apoptosis. Science. 2000;288:1053–1058. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5468.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Temam S, Flahault A, Perie S, et al. p53 gene status as a predictor of tumor response to induction chemotherapy of patients with locoregionally advanced squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:385–394. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.2.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reed JC, Miyashita T, Takayama S, et al. BCL-2 family proteins: regulators of cell death involved in the pathogenesis of cancer and resistance to therapy. J Cell Biochem. 1996;60:23–32. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(19960101)60:1%3C23::AID-JCB5%3E3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chao DT, Korsmeyer SJ. BCL-2 family: regulators of cell death. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:395–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minn AJ, Rudin CM, Boise LH, Thompson CB. Expression of bcl-xL can confer a multidrug resistance phenotype. Blood. 1995;86:1903–1910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Willis SN, Adams JM. Life in the balance: how BH3-only proteins induce apoptosis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:617–625. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trask DK, Wolf GT, Bradford CR, et al. Expression of Bcl-2 family proteins in advanced laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma: correlation with response to chemotherapy and organ preservation. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:638–644. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams JM, Cory S. The Bcl-2 protein family: arbiters of cell survival. Science. 1998;281:1322–1326. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolf GT, Fisher SG. Induction chemotherapy plus radiation compared with surgery plus radiation in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. The Department of Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Cancer Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1685–1690. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199106133242402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bauer JA, Trask DK, Kumar B, et al. Reversal of cisplatin resistance with a BH3 mimetic, (−)-gossypol, in head and neck cancer cells: role of wild-type p53 and Bcl-xL. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:1096–1104. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bradford CR, Zhu S, Poore J, et al. p53 mutation as a prognostic marker in advanced laryngeal carcinoma. Department of Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Cancer Cooperative Study Group. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:605–609. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1997.01900060047008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erber R, Conradt C, Homann N, et al. TP53 DNA contact mutations are selectively associated with allelic loss and have a strong clinical impact in head and neck cancer. Oncogene. 1998;16:1671–1679. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman M, Lim JW, Manders E, et al. Prognostic significance of Bcl-2 and p53 expression in advanced laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2001;23:280–285. doi: 10.1002/hed.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pukkila MJ, Kumpulainen EJ, Virtaniemi JA, et al. Nuclear and cytoplasmic p53 expression in pharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: prognostic implications. Head Neck. 2002;24:784–791. doi: 10.1002/hed.10124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vielba R, Bilbao J, Ispizua A, et al. p53 and cyclin D1 as prognostic factors in squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:167–172. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200301000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broker LE, Kruyt FA, Giaccone G. Cell death independent of caspases: a review. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3155–3162. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Urba S, Wolf G, Eisbruch A, et al. Single-cycle induction chemotherapy selects patients with advanced laryngeal cancer for combined chemoradiation: a new treatment paradigm. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:593–598. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliver CL, Bauer JA, Wolter KG, et al. In vitro effects of the BH3 mimetic, (−)-gossypol, on head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7757–7763. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolter KG, Wang SJ, Henson BS, et al. (−)-gossypol inhibits growth and promotes apoptosis of human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in vivo. Neoplasia. 2006;8:163–172. doi: 10.1593/neo.05691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oltersdorf T, Elmore SW, Shoemaker AR, et al. An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of solid tumours. Nature. 2005;435:677–681. doi: 10.1038/nature03579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verhaegen M, Bauer JA, Martin de la Vega C, et al. A novel BH3 mimetic reveals a mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent mechanism of melanoma cell death controlled by p53 and reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res. 2006;66:11348–11359. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]