Abstract

Past studies have revealed that encountering negative events interferes with cognitive processing of subsequent stimuli. The present study investigated whether negative events affect semantic and perceptual processing differently. Presentation of negative pictures produced slower reaction times than neutral or positive pictures in tasks that require semantic processing, such as natural/man-made judgments about drawings of objects, commonness judgments about objects, and categorical judgments about pairs of words. In contrast, negative picture presentation did not slow down judgments in subsequent perceptual processing (e.g., color judgments about words, and size judgments about objects). The subjective arousal level of negative pictures did not modulate the interference effects on semantic/perceptual processing. These findings indicate that encountering negative emotional events interferes with semantic processing of subsequent stimuli more strongly than perceptual processing, and that not all types of subsequent cognitive processing are impaired by negative events.

Keywords: negative mood, interference, valence, semantic processing, emotion and cognition

Encountering negative events can interfere with subsequent processing. Brief presentation of negative stimuli inhibits processing of other neutral information in many paradigms, such as lexical judgment tasks (Ihssen, Heim, & Keil, 2007), short-term memory retention (Dolcos, Kragel, Wang, & McCarthy, 2006; Dolcos & McCarthy, 2006), and the Stroop task (McKenna & Sharma, 1995). Sustained negative mood states and situational stressors also impair verbal problem solving (Alexander, Hillier, Smith, Tivarus, & Beversdorf, 2007), text comprehension (Ellis, Ottaway, Varner, Becker, & Moore, 1997), and Wason's selection task performance (Oaksford, Morris, Grainger, & Williams, 1996). However, it is not clear whether encountering negative events interferes equally with any type of subsequent cognitive processing or whether encountering negative events interferes with some types of subsequent processing more than other types of cognitive processing. The present study focused on comparing the interference effects of negative stimuli on semantic and perceptual processing.

Effects of Rapid Presentation of Emotional Stimuli

The brief presentation of emotional distractors can interfere with cognitive processing of subsequent stimuli when they are in attentional competition (Mather & Sutherland, 2011; Zeelenberg & Bocanegra, 2010). For example, rapid presentation of emotional stimuli impairs perceptual identification of subsequent stimuli (Anderson, 2005; Arnell, Killman, & Fijavz, 2007; Ihssen & Keil, 2009; Most, Chun, Widders, & Zald, 2005). Similar effects occur in a wide variety of tasks, such as lexical judgments (Calvo & Castillo, 2005; Ihssen, et al., 2007), the Stroop task (McKenna & Sharma, 1995), digit-parity judgments (Aquino & Arnell, 2007), the n-back task (Kensinger & Corkin, 2003), short-term memory retrieval (Dolcos, et al., 2006; Dolcos & McCarthy, 2006), and mathematical calculations (Schimmack, 2005). Such interference effects can be induced by positive arousing stimuli as well as by negative arousing stimuli (e.g., Ihssen, et al., 2007; Mather, et al., 2006; Schimmack, 2005).

One likely culprit for these interference effects is the attention-grabbing nature of emotional stimuli. Emotionally arousing stimuli can be identified with higher accuracy (Anderson, 2005; Keil & Ihssen, 2004), detected more quickly (Fox, Griggs, & Mouchlianitis, 2007; Öhman, Flykt, & Esteves, 2001; Öhman, Lundqvist, & Esteves, 2001), and capture attention more strongly than neutral stimuli (Fox, Russo, Bowles, & Dutton, 2001; Fox, Russo, & Dutton, 2002; Koster, Crombez, Van Damme, Verschuere, & De Houwer, 2004). This attentional saliency of arousing stimuli may be the reason why encountering emotionally arousing stimuli often impairs cognitive processing of subsequent/ less salient stimuli (e.g., Dolcos & McCarthy, 2006; Mather & Sutherland, 2011).

However, the attention-grabbing effects of emotionally arousing stimuli only last for a limited time. For example, emotionally arousing stimuli impair subsequent cognitive processing immediately after their presentation (100– 600 ms) but the effects soon disappear (e.g., more than 700 ms: Anderson, 2005; Arnell, et al., 2007; Bocanegra & Zeelenberg, 2009; Most, et al., 2005). In contrast, other emotional reactions, such as subjective feelings of mood states, occur very quickly after stimulus presentation (e.g., within 500 ms; Rudrauf, et al., 2009), but are sustained longer (more than a few seconds) than the effects on attention (Garrett & Maddock, 2006). Thus, arousal's rapidly dissipating interference effects might reflect only a part of the effects of brief presentation of emotional stimuli. In line with this argument, recent research has shown that a rapid viewing of emotional stimuli has different effects, depending on valence of the emotional words (e.g., Baumann & Kuhl, 2005). Given that similar valence specific effects were demonstrated in research on sustained mood states (e.g., Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005), it appears that brief encounters with emotional stimuli yield not only arousal's attention effects, but also valence-specific effects by modulating short-term transient emotional states.

Effects of Sustained Mood States

In contrast to the similar interference effects observed in studies with rapid presentation of arousing positive versus arousing negative stimuli, as reviewed below, evoking a negative mood tends to enhance and impair different types of cognitive processing than evoking a positive mood (Alexander, et al., 2007; Bolte, Goschke, & Kuhl, 2003; Gray, 2001; Gray, Braver, & Raichle, 2002; Isen, Daubman, & Nowicki, 1987; Isen, Johnson, Mertz, & Robinson, 1985; Rowe, Hirsh, & Anderson, 2007).

Valence specific effects of mood states

Previous research indicates that negative mood impairs tasks that require semantic processing, such as elaborative encoding of verbal information (Leight & Ellis, 1981), semantic priming (Storbeck & Clore, 2008), and retrieval of recently learned words (Ellis, Thomas, McFarland, & Lane, 1985) or text materials (Ellis, Varner, Becker, & Ottaway, 1995). In one study (Ellis, et al., 1997), for example, the authors asked participants in negative or neutral mood states to read a story with six contradictions and to identify the contradictions. The results indicated that participants with negative mood states detected fewer correct contradictions and made more errors in detecting the contradictions than those with neutral mood.

In contrast, in previous studies, positive mood states did not impair semantic processing. For instance, while negative mood states impaired verbal fluency (Bartolic, Basso, Schefft, Glauser, & Titanic-Schefft, 1999) and semantic judgments about words (Bolte, et al., 2003), positive mood states enhanced performance in these tasks (Bolte, et al., 2003; Carvalho & Ready, 2010; Phillips, Bull, Adams, & Fraser, 2002). Similarly, negative mood states impaired verbal insight problem solving (Subramaniam, Kounios, Parrish, & Jung-Beeman, 2009), whereas positive moods enhanced verbal insight problem solving (Isen, et al., 1987; Isen, et al., 1985; Rowe, et al., 2007; Subramaniam, et al., 2009). In addition, Leight and Ellis (1981) revealed that retrieval of verbal information was impaired by negative mood states (compared with neutral mood), but positive mood states had neither facilitative effects nor interference effects on subsequent memory retrieval. These results suggest that sustained negative moods impair subsequent semantic processing, but positive mood states yield less interference (or sometimes even facilitation).

Process specific effects of mood

In addition, recent studies suggest that the interference effect of negative mood is limited to semantic processing, and that perceptual processing is not impaired by negative mood states (Gray, 2001; Gray, et al., 2002; Kuhbandner, et al., 2009). Although there has not been much research addressing the dissociation directly, studies on fluency revealed that negative moods impair verbal fluency more strongly than figural fluency (Bartolic, et al., 1999; Papousek, Schulter, & Lang, 2009). Recent neuroimaging studies also suggest that encoding negative information activates regions of the brain associated with conceptual and semantic processing less than encoding positive information (Kensinger & Schacter, 2006, 2008; Mickley & Kensinger, 2008), while processing negative information is associated with activation in perceptual regions of the brain (Damaraju, Huang, Barrett, & Pessoa, 2009). These results also fit with behavioral evidence that people tend to have more perceptually vivid memories for negative stimuli than positive stimuli (Kensinger & Choi, 2009; Ochsner, 2000).

The Present Study

In summary, the results from previous studies suggest that negative mood impairs semantic processing more than perceptual processing. However, as far as we know, there have been no direct comparisons between the effects of negative mood on perceptual processing and those on semantic processing. Furthermore, most of the evidence on the perceptual/ semantic dissociation has been based on sustained mood states. Thus, it is not clear whether similar effects are obtained with transient short-term emotional states induced by brief presentation of negative stimuli.

The present study aimed to address whether or not short-term transient positive/ negative emotional states have a similar impact on subsequent semantic and perceptual processing. In our operational definition, semantic processing refers to cognitive processing which requires people to access their representations of the conceptual meaning of stimuli. In contrast, perceptual processing refers to cognitive operations on the perceptual characteristics of stimuli. Thus, perceptual processing requires people to access their knowledge about perceptual features (e.g., “what the color red looks like,” “how large an elephant is”), but does not require retrieving the semantic meaning of stimuli. Based on these operational definitions, we employed tasks requiring processing the semantic meanings of target stimuli as semantic tasks. In contrast, tasks that depend on perceptual knowledge but do not require accessing conceptual meanings of target stimuli were used as perceptual tasks. In Study 1, we compared the effects of encountering emotional stimuli on perceptual and semantic tasks on common objects. In Studies 2 and 3, we examined the effects on processing of pairs of words. Thus, across studies, we examined whether the effects can be generalized to different tasks and materials.

Across all studies, we presented participants with emotional stimuli for 800 ms, which was followed by a 500 ms blank interval and target stimuli (i.e., objects or pairs of words) that were processed either semantically or perceptually. Although this manipulation is more subtle than typical mood manipulations (e.g., thought generations; watching films; listening to music for several minutes), recent research has revealed that even briefer presentation of positive stimuli (i.e., 250-400 ms) can change people's emotional states and influence subsequent cognitive processing in a similar way as sustained positive mood states (e.g., Baumann & Kuhl, 2005; Dreisbach & Goschke, 2004). Thus, we expected that viewing emotional images for 800 ms would be long enough to change participants’ transient emotional states and to influence subsequent cognitive processing. In addition, as discussed above, it has been suggested that the interference effects due to attentional competition are not strong at stimulus onset asynchronies (SOA) longer than 700 ms (Anderson, 2005; Bachmann & Hommuk, 2005; Bocanegra & Zeelenberg, 2009). Based on these findings, we also expected that the relatively longer SOA in the current study (1300 ms) should reduce the effects of preferential attention allocation to emotional modulator stimuli, while allowing us to examine the effects of transient mood states evoked by the emotional stimuli.

Two additional issues were also addressed. First, we investigated the effects of positive emotional states. The effects of positive mood on subsequent cognitive stimuli are mixed. There are studies suggesting that positive mood facilitates subsequent semantic processing (Bolte, et al., 2003; Carvalho & Ready, 2010; Isen, et al., 1987; Phillips, et al., 2002; Subramaniam, et al., 2009), while others found that positive mood neither facilitated nor interfered with subsequent semantic processing (Leight & Ellis, 1981). To clarify the effects of positive emotional states on perceptual and semantic processing, we included a positive condition in addition to neutral and negative conditions, although we did not have specific predictions.

Second, the effect of arousal was also examined. Although we are interested in the effects of valence, it is important to address the effects of arousal for several reasons. First, as we discussed above, research on emotion and cognition revealed that emotionally arousing stimuli tend to grab attention more strongly than low arousing stimuli (Anderson, 2005; Schimmack, 2005), which results in general impairment in subsequent cognitive processing (e.g., Ihssen, et al., 2007). Second, because negative stimuli are usually higher in arousal than positive stimuli, it is also important to investigate the effects of arousal to discriminate the effects of valence from those of arousal.

Study 1

In Study 1, we examined whether encountering negative events influences subsequent semantic and perceptual processing differently using drawings of neutral objects (e.g., an apple; a clam; a pen). On each trial, participants saw a positive, negative or neutral picture (i.e., emotional modulator), which was followed by a neutral object (i.e., target stimulus). They were asked to make a judgment about each neutral object as quickly and as accurately as possible. To address the effects of negative pictures on semantic processing, we used two semantic tasks, in which participants had to access their knowledge about semantic features of a target stimulus. In one task, participants were asked to make a judgment about whether each object was natural or man-made (i.e., naturalness task). In the other task, participants made a judgment about whether each object represented something they encounter in a typical month or not (i.e., commonness task). In addition to these two semantic tasks, we employed one perceptual task to address the hypothesis. Many perceptual tasks are known to be cognitively less demanding than semantic tasks (Demb, et al., 1995; Gabrieli, et al., 1996). To reduce the confounding effects of cognitive demands, we employed a slightly difficult perceptual task (i.e., size task), where participants were asked to make a judgment about whether the object was larger than a computer screen we used in this experiment. Given past studies showing that similar size judgments activate brain regions involved in perceptual processing (Goldberg, Perfetti, & Schneider, 2006; Kellenbach, Brett, & Patterson, 2001), we expected that participants should access their knowledge about perceptual features of the target stimulus, but not necessarily their knowledge about its semantic features. If negative emotional states induced by negative pictures impair semantic processing more than perceptual processing, presentation of negative modulator pictures would slow reaction times in the two semantic tasks more than in the perceptual task.

In addition, we tested participants’ memory for the emotional and neutral modulator pictures that were presented before the drawings of objects during the task. Positive and negative emotional stimuli are usually remembered better than neutral stimuli (e.g., Hamann, Ely, Grafton, & Kilts, 1999). Thus, we expected to replicate this emotion advantage in memory.

Methods

Participants

Twenty-two undergraduates (Mage = 19.14, SD = 1.28; 10 males and 12 females) took part in the experiment for course credit. Data from one participant who did not press any keys during the first two-thirds of the trials were discarded.

Design

We employed a 3 (task: naturalness, commonness, size) X 3 (valence of emotional modulators: positive, negative, neutral) within-participant design and each condition involved six trials. Trials were presented randomly, regardless of the type of tasks and valence of the emotional modulators. We added two buffer trials at the beginning and at the end of the sessions to reduce primary/recency effects on the memory. In the buffer trials, we used neutral pictures not used on other trials.

Materials: Emotional modulators

Eighteen positive, 18 negative and 18 neutral pictures were selected from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS: Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 1997). The IAPS includes standardized ratings of valence of each picture based on a scale ranging from 1 (most unpleasant) to 9 (most pleasant) and ratings of arousal level on a scale ranging from 1 (least arousing) to 9 (most arousing). The average IAPS valence of the images we employed was 7.26 for positive (SD = 0.39), 2.80 for negative (SD = 0.70) and 5.05 for neutral images (SD = 0.55). Positive (M = 5.16, SD = 0.73) and negative pictures (M = 5.22, SD = 0.69) were matched in arousal level. The average arousal level of neutral pictures was 3.43 (SD = 0.60). We also matched the number of people depicted in the pictures across positive, negative, and neutral pictures (Ms = 1.1). Six of the 18 pictures in each valence category were randomly assigned to one of the three tasks conditions for each participant. Negative pictures included those depicting crying boys, a snake, and a man who commits suicide; positive pictures included sexual scenes, appetizing foods, and people who celebrate a victory; and neutral pictures included a woman who talks on the phone, a woman in a grocery market, and a port.

In the recognition task, additional 54 pictures (18 positive, 18 negative, and 18 neutral pictures) were used as foils. The average valence score for the foils was 7.23 for positive (SD = 0.71), 2.92 for negative (SD = 0.57), and 5.03 for neutral images (SD = 0.27). The average arousal score was 5.31 for positive (SD = 0.97), 5.14 for negative (SD = 0.84), and 3.32 for neutral images (SD = 0.57). The average number of people depicted in the foil pictures was also matched with the targets (Ms = 1.1).

Materials: Drawings of objects

Colored pictures of common objects were obtained from a previous study (Snodgrass & Vanderwart, 1980), the Internet, and commercial DVDs of clipart images. We used drawings with objects that were not depicted in any of the IAPS photographs. The objects were randomly assigned to the nine conditions for each participant.

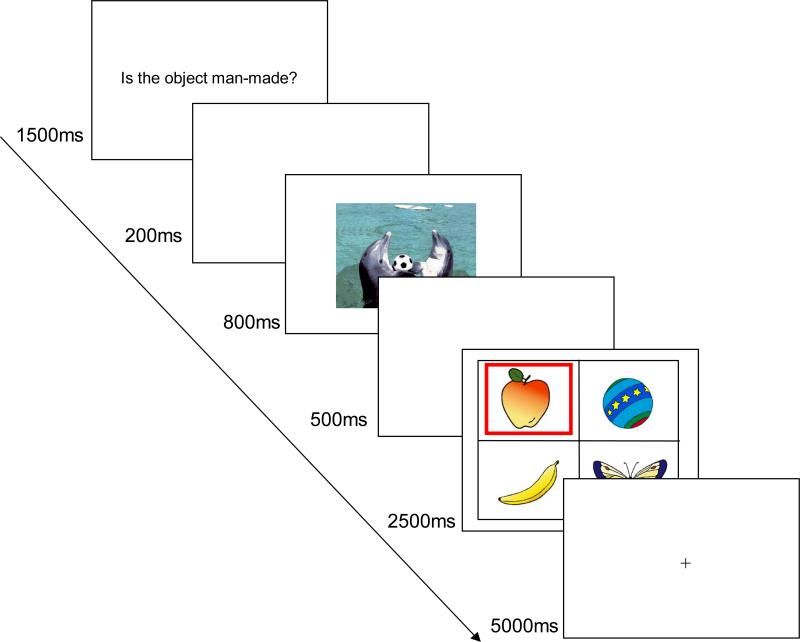

Procedure

After giving informed consent, participants filled out a short demographics questionnaire and then sat in front of a computer. They were told that their task would be to make judgments about target objects. On each trial (see Figure 1), first, participants were presented with one of three questions about a target object they would see later in the trial. One question was about whether the object was natural or man-made (“Is the object man-made?”), another question asked whether the participant encountered the object in a typical month or not (“Is the object common?”), and the other was about whether the object was larger than the computer screen used in the experiment (“Is the object larger than the computer screen?”). Participants were asked to keep the question in mind until they saw a target object. The questions were presented for 1500 ms on the screen. Next, a positive, negative or neutral IAPS image appeared for 800 ms. Participants were told to view the image passively without looking away from it. Following a 500 ms blank screen, they saw four objects simultaneously for 2500 ms. The screen was divided into a two by two grid and each of these four objects was presented in one of the four cells. One of the four objects was highlighted by a red box (which object was highlighted was randomly selected across participants). Participants were told that the highlighted object was a target object, and that their task was to answer the question they had seen in the trial as quickly and as accurately as possible by pressing either the “Y” or “N” key. 1 The inter-trial interval was 5000 ms.

Figure 1.

An example of the trial sequence in the naturalness task condition of Study 1.

When participants finished all trials, they were asked to work on a mathematical calculation task for three minutes, which was followed by a recognition test about the IAPS modulators. The recognition task involved 54 pictures they saw in the preceding task and another 54 pictures they did not see in the task as foils. Participants judged whether they had seen each picture during the task or not.

Results

Effects of emotional modulators on semantic versus perceptual processing

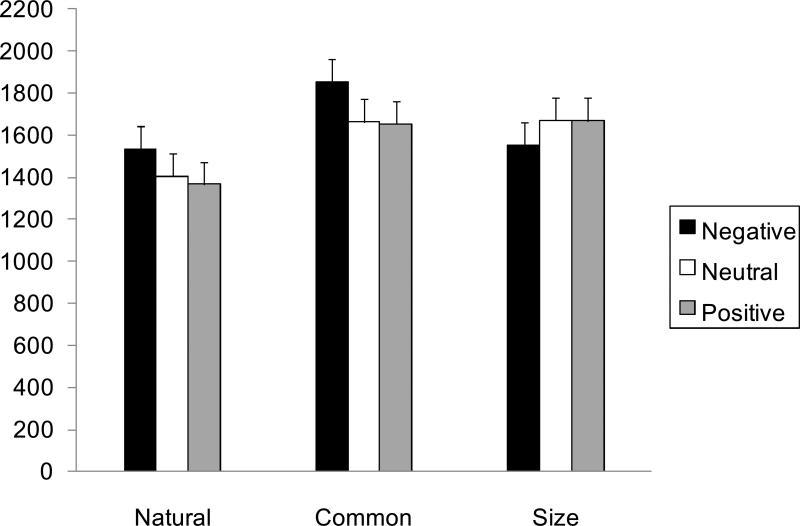

A 3 (task: natural, common, size) X 3 (valence: positive, negative, neutral) analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted on the response latencies to address the effects of emotional modulators on semantic and perceptual processing. This ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of task, F (2, 40) = 27.86, p < .01, R2 = .06, as the commonness task (M = 1722 ms) took longer than the naturalness (M = 1434 ms) and the size tasks (M = 1631 ms; p < .05), and the size task took longer than the naturalness task (p < .05). In addition, the ANOVA revealed a significant interaction between task and valence, F (4, 80) = 4.18, p < .01, R2 = .06. Further analyses showed significant effects of valence in the naturalness task, F (2, 40) = 4.46, p < .05, R2 = .05, and the commonness task, F (2, 40) = 4.71, p < .05, R2 = .02. In the commonness task, participants took longer to answer the question after negative modulator pictures than after neutral pictures, t (40) = 2.60, SE = 73, p < .05, or positive pictures, t (40) = 2.71, SE = 73, p < .05. Similarly, participants took longer to answer the naturalness question after negative pictures than after neutral pictures, t (40) = 2.18, SE = 58, p < .05, or positive pictures, t (40) = 2.86, SE = 58, p < .05. In contrast, the reaction time was not influenced by the valence of the modulator pictures in the size task condition (p > .15; see Figure 2).2

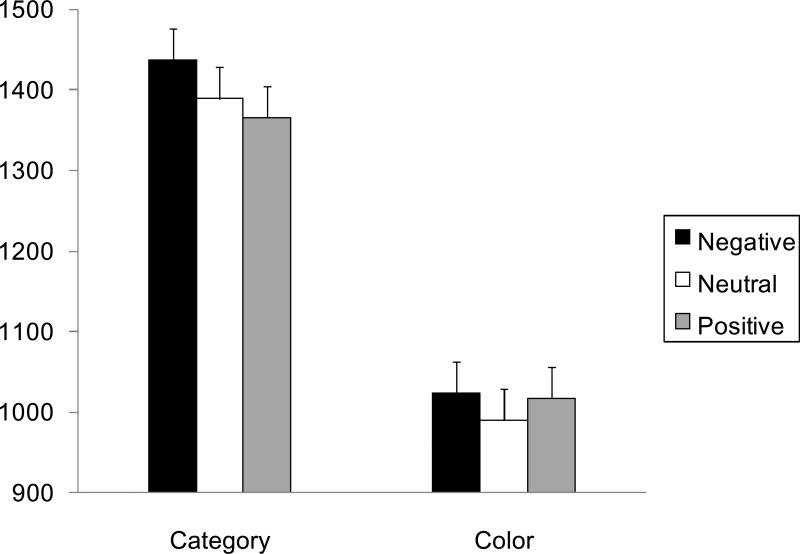

Figure 2.

Effects of emotional modulator pictures on reaction times in the three task conditions in Study 1. Brief presentation of negative pictures produced slower reaction times in two tasks that required semantic knowledge (i.e., natural-man made judgments about objects and commonness judgments about objects), but not in a perceptual task (size judgment about the object). Error bars represent standard errors.

Trial-based analysis on the effects of valence and arousal

To examine the effects of arousal, we performed a trial-by-trial basis analysis by using the IAPS normative arousal and valence ratings. Given a nested structure of our data (i.e., each trial was nested within each individual participant), we employed a Hierarchical Linear Model (HLM: Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) with each trial response as a Level 1 unit and each participant as a Level 2 unit. Unlike standard regression or correlation approaches, HLM allowed us to deal with multilevel data appropriately and to obtain precise parameter estimates of interest.

The dependent variable was a reaction time on each trial from each participant. Independent variables were a) the type of tasks used in each trial (i.e., natural, common, or size) , b) the IAPS normative valence and c) arousal score for a picture presented in the trial, d) an interaction between task and valence rating score, and e) an interaction between task and arousal rating score. This analysis revealed a significant main effect of task, F (1, 40) = 23.15, p < .001, and of valence, F (1, 40) = 4.89, p < .05. In addition, there was a significant interaction between valence rating score and task, F (1, 40) = 6.10, p < .01. Supporting the results from the ANOVA described in a previous section, the more negative the pictures were, the slower participants’ reaction times were in the commonness (unstandarized beta = -41.80), t (40) = -2.59, SE = 16, p < .05, and the naturalness tasks (unstandarized beta = -33.81), t (40) = -2.76, SE = .12, p < .05. In contrast, reaction times in the size task did not have a significant effect of valence score (p > .15). Importantly, neither the main effect of arousal (p > .25), nor the interaction between arousal and task (p > .40) were significant, suggesting that the effects of negative pictures are not attributable to arousal.

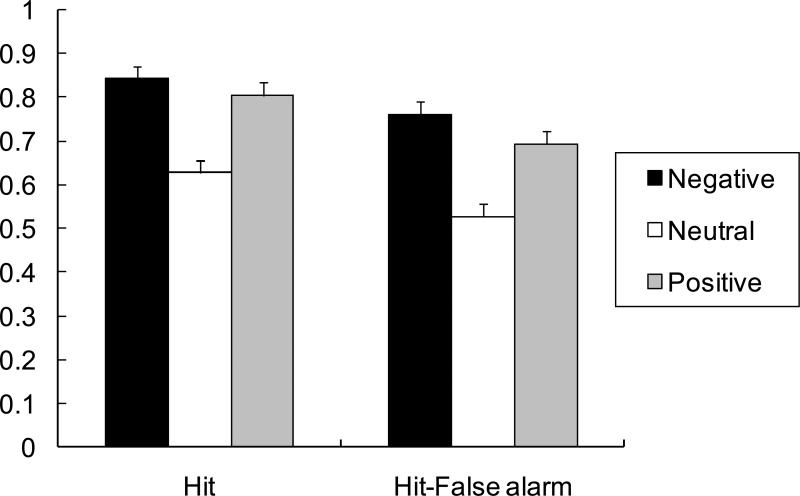

Memory for emotional modulators

To examine memory for emotional modulators, a 3 (task: natural, common, size) X 3 (valence: positive, negative, neutral) ANOVA was performed on the hit rates from the IAPS picture recognition test. The ANOVA revealed a significant effect of valence, F (2, 40) = 28.92, p < .01, R2 = .34. Participants remembered negative (M = .84) and positive pictures (M = .80) better than neutral pictures (M = .63; see Figure 3), t (40) = 7.14, SE = 0.03, p < .01, t (40) = 5.83, SE = 0.03, p < .01. Neither the main effect of task nor the interaction between task and valence was significant (ps > .05).

Figure 3.

Participants’ recognition memory for emotional modulator pictures in Study 1, expressed as their hit rate for old pictures (on the left) and their hit rate minus their false alarm rate (on the right). The error bars represent standard errors.

Based on the median-split using the IAPS normative arousal scores, we compared the hit rates for highly arousing pictures and low arousing pictures. Since the previous ANOVA did not find any significant effects involving task, we collapsed different task conditions in this analysis. A 2 (valence: positive vs. negative) X 2 (arousal: high vs. low) ANOVA revealed a significant effect of arousal, F (1, 20) = 15.56, p < .01, R2 = .02, indicating that participants remembered pictures with high arousal (M = .88) better than those with low arousal (M = .77). However, neither the main effect of valence nor the interaction between valence and arousal was significant (ps > .14).3

Discussion

Consistent with previous findings (e.g., Hamann, et al., 1999), participants remembered both positive and negative pictures better than neutral pictures. Participants also had better memory for pictures categorized as high arousal compared to pictures categorized as low arousal, regardless of valence. In contrast, positive and negative conditions had different effects in two tasks requiring semantic knowledge; viewing negative pictures slowed subsequent naturalness and commonness judgments, compared with viewing positive and neutral pictures. In contrast, viewing negative pictures did not slow size judgments. Overall, the size judgment task took longer than the naturalness judgment, but took less time than the commonness judgment, suggesting that the size task was more difficult than the naturalness task, and easier than the commonness task. Yet, we did not observe interference effects of negative pictures in the size task, while we found that negative picture presentation produced delayed reaction times both in the naturalness and in the commonness tasks. Thus, it is unlikely that the results are attributable to task difficulty. Taken together, Study 1 supports our prediction that negative emotional states impair semantic processing more strongly than perceptual processing.

One question about Study 1 concerns the size task. On the one hand, the size task was cognitively demanding as it required participants to retrieve their perceptual knowledge about every target object. Thus, it enabled us to compare perceptual and semantic processing without confounding effects of task difficulty. On the other hand, however, it might be possible that participants accessed not only their perceptual knowledge, but also their semantic knowledge about target stimuli, while performing the size task. Furthermore, on each trial, participants saw three objects in addition to the target object, which might have contributed to the effects of negative pictures on the reaction times. Thus, it is necessary to see whether the results of Study 1 replicate with different tasks without any additional distracting stimuli. Study 2 addressed these issues.

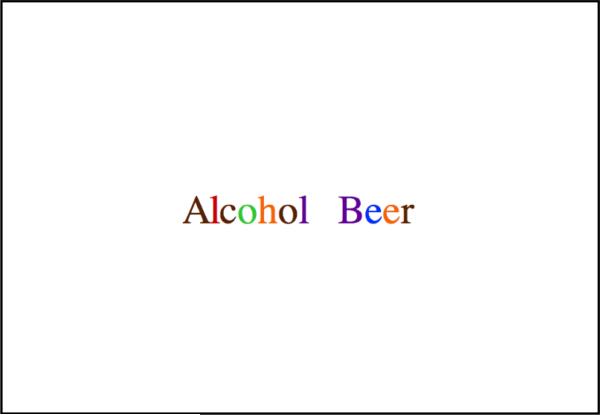

Study 2

Study 2 aimed to provide further evidence on the effect of short-term emotional states on semantic versus perceptual processing by using different materials and tasks. In Study 2, we presented participants with pairs of words (e.g., digit/zero), following emotional or neutral modulator pictures. Six different colors were used to print the letters (see Figure 4). Unlike Study 1, we did not show distracting stimuli other than the two words during the target stimuli presentation. On half of the trials, participants were asked to make a decision about whether the two words came from the same semantic category or not (i.e., semantic task). On other trials, participants were asked to make a decision about whether the first letters in the two words had the same or different colors (i.e., perceptual task). If negative emotional states interfere with semantic processing more than perceptual processing, reaction times for the semantic task should be slower after negative modulators than after neutral or positive modulators. In contrast, reaction times for the perceptual task should be less influenced by negative pictures than those for the semantic task.

Figure 4.

Example stimuli from Studies 2 and 3. Two words were printed in multiple colors. On half of the trials, the first letters of the two letters of two words were printed in the same color, while on the other trials, they were printed in different colors. To print the words, we employed six distinctive colors in Study 2, and six similar, but slightly different shades of blue in Study 3.

Two additional issues were also addressed in Study 2. First, Study 1 did not measure the accuracy of participants’ judgments. Therefore, we could not rule out the possibility that presentation of negative pictures produces more accurate judgments than neutral or positive ones, which resulted in longer reaction times after negative modulators (i.e., speed-accuracy tradeoff). In Study 2, we obtained the accuracy of judgments as well as the reaction times to address this issue. Second, Study 2 examined the effects of arousal by using participants’ own evaluations about modulator pictures. In Study 1, we used the IAPS normative arousal ratings and found that the arousal level did not influence the subsequent semantic/ perceptual judgments. However, because of the small number of trials in each condition (i.e., 6 trials), the statistical power to test the arousal effects was low. In addition, participants’ subjective feelings of arousal might be different from IAPS normative data, depending on their own experiences. In Study 2, we increased the number of trials in each condition (i.e., 20 trials) and obtained participants’ arousal ratings of each picture to examine the effects of arousal on semantic/perceptual processing.

Method

Participants

Forty-six undergraduates whose first language was English participated in the experiment (6 males, 40 females; Mage = 20.04, SD = 1.22).

Design

A 2 (tasks: category, color) X 3 (valence: positive, negative, neutral) within-participants design was employed, with 20 trials in each condition. We did not include buffer trials as we did not employ memory tests in this study.

Materials: Emotional modulators

Forty negative, 40 positive, and 40 neutral IAPS pictures were used as modulators. The average IAPS valence was 7.29 for positive (SD = 0.19), 2.74 for negative (SD = 0.22), and 5.03 for neutral pictures (SD = 0.22). The average IAPS arousal was 5.31 for positive (SD = 0.16), 5.26 for negative (SD = 0.19), and 3.14 for neutral pictures (SD = 0.17). In each valence category, 26 pictures depicted human faces. The 40 pictures in each valence category were divided into two stimulus sets matched in valence, arousal, and the number of pictures depicting faces. The stimulus sets were randomly assigned to the two tasks conditions (category, color) and the assignment was counterbalanced across participants.4

Materials: Target words

We collected pairs of words so that one word represented a category name (e.g., ape) and the other represented an example from that category (e.g., gorilla). The words were selected from WordNet (Miller, 1995). Two coders agreed upon 180 pairs of words (regarding whether it consists of a category name and an example from that category) that were used in the experiment.

The 180 pairs were randomly divided into three stimulus sets, each of which involved 60 pairs. For each participant, two of the three stimulus sets were randomly selected and used in the experiment. Pairs in one stimulus set were used as true category pairs (i.e., pairs involving a category name and an example from the same semantic category; e.g., ape/gorilla, digit/zero). Another stimulus set was used as false category pairs (i.e., pairs involving a category name and an example from a different category). The false category pairs were made by mixing up true category pairs from the same stimulus set, to avoid any qualitative differences between words in true pairs and those in false pairs. For example, two false pairs (e.g., “lamp/professor,” “roof/chemistry”) were made based on four true pairs, such as “lamp/lantern,” “educator/professor,” “roof-dome,” and “science/chemistry.” The pairs in each stimulus set were randomly assigned to one of the 2 (task) X 3 (emotion) conditions across participants. The stimulus sets for true and false pairs were counterbalanced across participants.

We used six different colors (i.e., red, orange, blue, brown, green, and purple). Letter colors were assigned pseudorandomly so that no adjacent letters were of the same color (see Figure 4 for an example). On half of the pairs in each condition, the first letters of the two words were printed in the same color, whereas they were printed in different colors on other pairs. Whether pairs had same or different first-letter colors were counterbalanced across participants.

Procedures

On each trial, participants were shown a question for 1500 ms. They saw “Do they come from the same category?” in the semantic condition and “Are the first letters written in the same color?” in the perceptual condition. They were asked to keep the question in mind until they saw a pair of words. The question was followed by a 200 ms blank screen, which was replaced by either a positive, negative, or neutral modulator for 800 ms. After a 500 ms blank screen, participants were presented with a pair of words in multiple colors for 2500 ms. They were asked to press a key to indicate their answer to the question for that trial as quickly and as accurately as possible. The inter-trial interval was 5000 ms.

Following the task, participants were asked to rate each picture used in the experiment on a 1-9 scale for arousal (1: not at all, 9: extremely) and valence (1: extremely negative, 9: extremely positive).

Results

Ratings of emotional modulators

We analyzed participants’ valence ratings of the modulator pictures with a 2 (task: category, color) X 3 (valence: positive, negative, neutral) ANOVA. There was a significant effect of valence, F (2, 90) = 534.86, p < .01, R2 = .73, but no other significant effects (ps > .45). Participants rated negative modulators (M = 2.19) more negatively than neutral (M = 4.87), t (90) = 17.81, SE = .15, p < .01, or positive modulators (M = 7.12), t (90) = 32.66, SE = .15, p < .01, and positive modulators more positively than neutral pictures, t (90) = 14.85, SE = .15, p < .01. A similar ANOVA on the arousal rating also produced a significant effect of valence, F (2, 90) = 190.07, p < .01, R2 = .45. Negative pictures (M = 6.40) were rated higher in arousal than neutral (M = 3.01), t (90) = 18.64, SE = .18, p < .01, or positive pictures (M = 5.60), t (90) = 4.38, SE = .18, p < .01. Positive pictures were also rated higher in arousal than neutral pictures, t (90) = 14.26, SE = .18, p < .01. There were no other significant effects (ps > .20).

Effects of emotional modulators on semantic versus perceptual judgment

After discarding trials which produced reaction times more than 1.5 standard deviations above the mean for each condition for each individual participant, a 2 (task: category, color) X 3 (valence: positive, negative, neutral) ANOVA was performed on the reaction times. The ANOVA revealed a significant effect of task, F (1, 45) = 535.87, p < .001, R2 = .36, of valence, F (2, 90) = 3.07, p < .05, R2 = .002, and a significant interaction between valence and task, F (2, 90) = 3.36, p < .05, R2 = .38. Subsequent analyses revealed a significant effect of valence in the category task, F (2, 90) = 9.91, p < .01, R2 = .01, but not in the color task (p > .05). Consistent with our hypothesis, in the category task, participants took longer time to respond to the task after negative modulators than after neutral or positive modulators (Figure 5), t (90) = 2.93, 4.37, SEs = 16, ps < .05.5

Figure 5.

Effects of emotional modulator pictures on reaction times in the categorical task (i.e., semantic task) and the color task (i.e., perceptual task) in Study 2. Brief presentation of negative modulator pictures produced slower reaction times in the semantic task but not in the perceptual task. Error bars represent standard errors.

In contrast, in a similar 2 (task) X 3 (valence) ANOVA on the accuracy of judgments, there was no significant interaction between task and valence (p > .50). The only significant effect in this ANOVA was a main effect of task, F (2, 45) = 14.96, p < .001, R2 = .31, reflecting that the color task (M = .97) produced the higher accuracy rates than the category task (M = .94). These results suggest that the speed-accuracy tradeoff cannot explain the longer reaction times in the semantic task following negative pictures.

Valence vs. arousal effects on semantic and perceptual processing

Emotional modulator pictures rated higher than the median on the arousal scale by the participant were categorized in each emotional category for each task condition as high arousing pictures, while others were categorized as low arousing pictures. A 2 (task: category, color) X 2 (valence: positive, negative) X 2 (arousal: high, low) ANOVA on the reaction times found significant effects of task, F (1, 40) = 200.07, p < .001, R2 = .35, and of valence, F (1, 40) = 9.20, p < .01, R2 = .004. In addition, this ANOVA confirmed a significant interaction between valence and task, F (1, 40) = 9.40, p < .01, R2 = .36. There were no other significant effects (ps > .30). These results indicate that encountering negative stimuli impairs subsequent semantic processing more strongly than perceptual processing, regardless of the arousal level (Table 1).

Table 1.

The average reaction time for semantic and perceptual tasks (standard errors are in parentheses), with reaction times categorized by picture modulator arousal (by median-split), picture modulator valence and task judgment type.

| High Arousal | Low Arousal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | ||

| Study 2 | Category | 1451 (43) | 1364 (43) | 1431 (41) | 1368 (41) |

| Color | 1034 (43) | 1022 (43) | 1017 (41) | 1015 (41) | |

| Study 3 | Category | 1597 (100) | 1478 (99) | 1561(98) | 1496 (98) |

| Color | 1734 (100) | 1760 (99) | 1714 (98) | 1695 (98) | |

Trial-based analysis on the effects of valence and arousal

We further addressed the effects of subjective ratings of arousal or valence on a trial-by-trial basis by employing a HLM analysis. The analysis was similar to Study 1, except that we used participants’ own valence and arousal ratings for each picture, instead of the IAPS normative ratings. The analysis revealed significant main effects of task and of valence rating score, respectively, Fs (1, 45) = 201.05, 5.18, ps < .05. In addition, there was a significant effect of arousal, F (1, 45) = 6.78, p < .05, reflecting slower reaction times after highly arousing pictures than low arousing pictures (unstandarized beta = 4.83, SE = 2.99). The main effect of arousal seems consistent with past studies showing that highly arousing stimuli tend to grab attention (Anderson, 2005; Schimmack, 2005), which interferes with many different kinds of tasks, regardless of whether they required perceptual or semantic processing (Aquino & Arnell, 2007; Dolcos, et al., 2006; Dolcos & McCarthy, 2006; Ihssen, et al., 2007; Ihssen & Keil, 2009; Mather, et al., 2006). Because the current study had longer SOAs between emotional modulators and target stimuli (i.e., pairs of words) than past studies, however, the attentional effects should not be strong as compared with previous studies. This might be a reason why the previous ANOVA, where median-split of arousal was employed, did not reveal a similar main effect of arousal.

More importantly, however, the arousal effect was not modulated by the type of tasks (p > .75). In contrast, there was a significant interaction between valence rating score and task, F (1, 45) = 5.02, p < .01. Further analyses revealed that the more negative the pictures were, the slower participants’ reaction times were in the semantic task condition (unstandarized beta = -8.58), t (45) = 2.85, SE = 3.01, p < .01. In the perceptual task condition, however, there was no significant effect of valence rating score on the reaction times (unstandarized beta = -0.32; p > .85). These results again support our hypothesis that negative emotional states impair subsequent semantic processing more strongly than perceptual processing.

Discussion

Using new materials and tasks, Study 2 replicated our findings in Study 1 that encountering negative stimuli impairs subsequent semantic processing more strongly than perceptual processing. We also obtained participants’ subjective arousal ratings of each picture and found that arousal level did not affect the impairment effects of negative pictures on semantic processing. Subsequent trial-by-trial basis analyses also confirmed similar patterns. That is, the more negative pictures participants viewed, the longer they took to make semantic judgments, but not perceptual judgments. In contrast, although there was a significant main effect of arousal, the arousal's effect was not qualified by the type of tasks. Thus, it appears that encountering highly arousing stimuli produces general interference effects on subsequent cognitive processing, but not specific interference effects on semantic processing. These results extend our findings in Study 1 and suggest that encountering negative stimuli impairs semantic processing more strongly than perceptual processing, regardless of subjective arousal.

One limitation of Study 2 concerns task difficulty. In Study 2, participants showed higher accuracy and faster reaction times in the perceptual task than in the semantic task. This raises a concern that the differential interference effects of negative pictures might be due to the task difficulty, instead of the semantic/perceptual nature of the tasks. Study 3 addressed this issue.

Study 3

Study 3 addressed whether viewing negative pictures disrupts semantic processing more strongly than perceptual processing, even when we employed a difficult perceptual task. The procedures of Study 3 were similar to Study 2. To make the perceptual task difficult, however, we changed the colors of the word letters. That is, instead of Study 2's six colors that were easily distinguishable, we used six similar/ but slightly different shades of blues. We expected that the high similarity across colors would make it difficult to judge whether two letters are in the same or different colors (e.g., Jiang & Kanwisher, 2003). In addition, as in Study 2, no adjacent letters were of the same color. Since color perception is also influenced by colors of surrounding stimuli (e.g., Brown & MacLeod, 1997; Lotto & Purves, 2002), this manipulation should make the perceptual task even more difficult.

Methods

Participants

Forty-six undergraduates participated in the experiment (11 males, 35 females; Mage = 20.15, SD = 2.28).

Procedures

Procedures were similar to Study 2, except the colors of the word pairs. Six different shades of blues were employed to print two words on the screen. RGB values for each of the six colors were (42, 82, 190), (65, 105, 180), (65, 86, 197), (73, 97, 201), (77, 77, 255), and (79, 105, 200). To standardize the distance of the head from the computer monitor, participants were asked to put their chin on a chin rest. Participants made a judgment about whether the two words came from the same semantic category or not in the semantic condition, and whether the first letters of the two words were printed in the same blue or not in the perceptual condition. As in Study 2, participants rated each modulator picture in terms of valence and arousal, after they finished the judgment task.

Results

Ratings of emotional modulators

A 2 (task: category, color) X 3 (valence: positive, negative, neutral) ANOVA on the valence rating revealed a significant effect of valence, F (2, 90) = 1385.15, p < .01, R2 = .77, but no other significant effects (ps > .35). Participants rated negative modulators (M = 2.28) more negatively than neutral (M = 5.00), t (90) = 27.37, SE = .10, p < .001, or positive modulators (M = 7.52), t (90) = 52.62, SE = .10, p < .001, and positive modulators more positively than neutral pictures, t (90) = 25.25, SE = .10, p < .01. A similar ANOVA on the arousal rating also produced a significant effect of valence, F (2, 90) = 291.60, p < .001, R2 = .44, with no other significant effects (ps > .45). Negative pictures (M = 5.86) were rated higher in arousal than neutral (M = 2.18), t (90) = 22.65, SE = .16, p < .001, or positive pictures (M = 5.20), t (90) = 4.07, SE = .16, p < .001. Positive pictures were also rated higher in arousal than neutral pictures, t (90) = 18.58, SE = .16, p < .001.

Effects of emotional modulators on semantic versus perceptual judgment

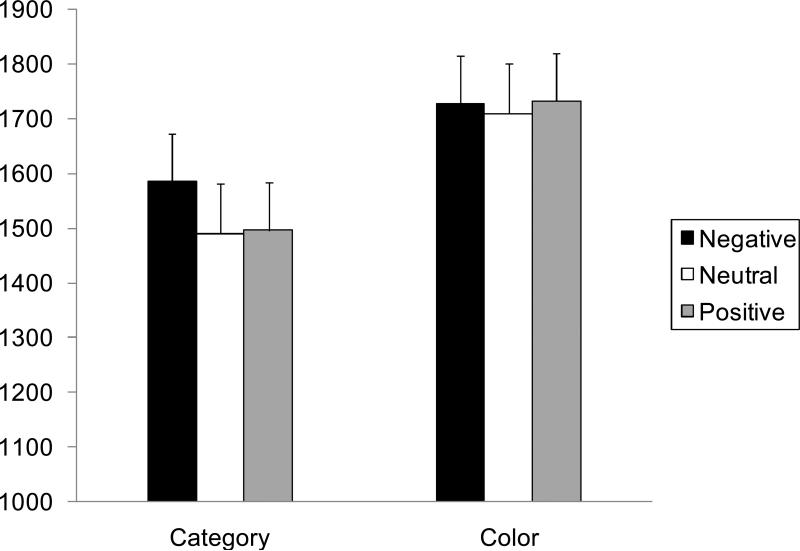

After outlier response times were identified using the same criterion as Study 2, a 2 (task: category, color) X 3 (valence: positive, negative, neutral) ANOVA was performed on the reaction times in word pairs judgments. The ANOVA revealed a significant effect of task, F (1, 45) = 59.12, p < .001, R2 = .14, reflecting that participants were slower in the color task (M = 1723 ms) than in the categorical task (M = 1525 ms). In addition, there was a significant interaction between valence and task, F (2, 88) = 3.44, p < .05, R2 = .19. Subsequent analyses revealed a significant effect of valence in the category task, F (2, 89) = 7.94, p < .01, R2 = .06. Replicating our findings of Study 2, participants took longer to respond to the category task after negative modulators than after neutral or positive modulators (Figure 6), ts (89) = 3.51, 3.39, SEs = 26, ps < .01. In contrast, the valence effect was not significant in the color task (p > .70).6

Figure 6.

Effects of emotional modulator pictures on reaction times in the categorical task (i.e., semantic task) and the color task (i.e., perceptual task) in Study 3. Viewing negative modulator pictures produced slower reaction times in the semantic task but not in the perceptual task even when the perceptual task was more difficult than the semantic task. Error bars represent standard errors.

In contrast, a similar 2 (task: category, color) X 3 (valence: positive, negative, neutral) ANOVA on the accuracy of judgments revealed a significant effect of task, F (2, 45) = 125.07, p < .001, R2 = .68, but no other significant effects (ps > .90). The main effect of the task reflected higher accuracy rates for the categorical task (M = .94) than for the color task (M = .73). Thus, as in Study 2, the speed-accuracy trade off cannot account for the valence x task interaction in the reaction times.

Valence vs. arousal effects on semantic and perceptual processing

To examine the effects of arousal, emotional modulator pictures rated higher than the median on the arousal scale by the participant were categorized in each emotional category for each task condition as high arousing pictures, while others were categorized as low arousing pictures. A 2 (task: category, color) X 2 (valence: positive, negative) X 2 (arousal: high, low) ANOVA on the reaction times found a significant effect of task, F (1, 32) = 56.92, p < .001, R2 = .13, and a marginally significant effect of valence, F (1, 32) = 2.95, p < .10, R2 = .02. In addition, this ANOVA confirmed a significant interaction between valence and task, F (1, 32) = 6.42, p < .01, R2 = .17. However, there were no significant effects involving arousal (ps > .14). These results suggest that short-term negative emotional states impair semantic processing more strongly than perceptual processing, regardless of the arousal level (Table 1).

Trial-based analysis on the effects of valence and arousal

Next, we examined the effects of participants’ own ratings of arousal or valence on a trial-by-trial basis. An HLM analysis, similar to Study 2, revealed a significant main effect of task, F (1, 45) = 34.19, p < .01. We also found a significant effect of arousal rating, F (1, 45) = 6.50, p < .05, reflecting that participants were slower on trials where they saw high arousing stimuli than low arousing stimuli (unstandarized beta = 7.68, SE = 3.47). However, the arousal effect was not modulated by the type of tasks (p > .50). In contrast, consistent with the analyses described above, we found a significant interaction between valence rating and task, F (1, 45) = 6.27, p < .01. Further analyses revealed that the more negative pictures participants encountered, the slower their reaction times were in the semantic task condition (unstandarized beta = -11.63), t (45) = 2.27, SE = 5.13, p < .05, but not in the perceptual task condition (p > .25). These results again support the role of the negative valence, rather than the arousal.

Discussion

In Study 3, participants were slower and less accurate in the color task than in the categorical task. Thus, the color task appeared more difficult and demanding than the categorical task. If the selective interference effects we observed in Study 2 were attributable to the task difficulty, therefore, viewing of negative pictures should interfere with the color task more strongly than the categorical task. However, Study 3 revealed the opposite pattern. That is, brief presentation of negative images produced slower reaction times only in the categorical task, but not in the color task. These results suggest that the semantic/perceptual nature of cognitive processing is more important than the task difficulty in determining whether encountering negative stimuli impairs subsequent cognitive processing or not. We also replicated findings from Studies 1 and 2, showing that subjective arousal does not modulate the effects of negative stimuli on semantic processing. Thus, it appears that encountering negative stimuli impairs subsequent semantic processing more strongly than perceptual processing, regardless of arousal level.

General Discussion

The present study compared the effects of negative picture presentation on semantic and perceptual processing of subsequent stimuli. In Study 1, we found that, compared with neutral or positive pictures, presentation of negative pictures produced longer reaction times in two subsequent tasks that required semantic knowledge: natural/man-made judgments and commonness judgments about neutral objects. In contrast, reaction times did not differ across valence in the size judgment task – a task requiring perceptual knowledge about objects but not necessarily semantic knowledge. Despite the fact that participants remembered pictures with high arousal better than those with low arousal, arousal level did not modulate the effects of negative pictures on semantic/perceptual judgments. In Studies 2 and 3, we replicated the selective negative valence interference effects on semantic processing with different stimuli and tasks. In these studies, viewing negative pictures slowed reaction times in categorical judgments of words. In contrast, neither an easy color judgment (Study 2), nor a difficult color judgment (Study 3) was influenced by negative picture presentation. We also obtained subjective ratings of arousal about each picture, but these rated arousal levels did not modulate the effects of emotional pictures. In contrast, subjective ratings of valence had significant effects on the semantic task but not on the perceptual task. Thus, our findings indicate that encountering negative events impairs subsequent semantic processing more strongly than perceptual processing.

Emotionally arousing stimuli grab and hold people's attention strongly (Anderson, 2005; Fox, et al., 2007; Fox, et al., 2001; Fox, et al., 2002; Keil & Ihssen, 2004; Öhman, Flykt, et al., 2001; Öhman, Lundqvist, et al., 2001). This attentional capture seems to impair most types of cognitive processing of subsequent competing stimuli (Anderson, 2005; Arnell, et al., 2007; Barnard, Ramponi, Battye, & Mackintosh, 2005; Ihssen, et al., 2007; Ihssen & Keil, 2009; Most, et al., 2005), regardless of the valence of the emotional stimuli (Ihssen, et al., 2007; Mather, et al., 2006; Schimmack, 2005). However, the attentional capture effects are time-limited and last only 600-700 ms after emotional stimuli are presented (Bachmann & Hommuk, 2005; Bocanegra & Zeelenberg, 2009). In contrast, the present study employed a longer SOA (i.e., 1300 ms) and revealed that negative emotional pictures impaired subsequent semantic processing more than perceptual processing. Across studies, these results suggest that presentation of emotional stimuli produces different interference effects on subsequent cognitive processing, depending on the time course. More precisely, we suggest that: a) during and immediately after exposure to an emotionally arousing stimulus, people's attention is consumed by that stimulus to the detriment of processing most other information; b) after this brief attentional capture phase, arousal can enhance attention to other salient stimuli (for a review see Mather & Sutherland, 2011), and that c) valence-specific effects emerge, such that negative valence impairs semantic but not perceptual processing.

Meta-analysis of Studies 1 -3

Although we found consistent patterns across three experiments, one possible concern might be that Study 1 had only small numbers of trials per condition. Thus, it might be possible that such small numbers of trials caused low statistical power (i.e., increased Type II errors), which might have resulted in null effects of negative pictures on perceptual processing, and null effects of positive pictures on semantic processing. However, the key finding of the current study is the interaction between valence and type of the tasks, rather than the null effects. Thus, even if statistical power was low in the current study, this would not weaken our conclusion that encountering negative events impairs subsequent semantic processing more strongly than perceptual processing.

We also addressed the concerns about statistical power by using meta-analyses based on results from Studies 1-3, as meta-analyses can increase statistical power (Cohn & Becker, 2003). First, we addressed the effects of negative pictures on perceptual tasks. For each perceptual task, we obtained an estimate of effect size (d) for differences in reaction times between negative and neutral conditions (Dunlap, Cortina, Vaslow, & Burke, 1996). These effect size estimates were integrated across the three perceptual tasks used in the current study (Hedges & Vevea, 1998). The resulting effect size (d = .04) was still small (Cohen, 1992) and the effects were not significant (Z = 0.25, p > .80). Thus, reaction times in the perceptual tasks did not differ between negative and neutral condition, even if we combined the three perceptual tasks.7 Next, we performed a similar meta-analysis to address the possibility that low statistical power produced the null effects of positive pictures on semantic tasks. For each semantic task, an estimate of effect size (d) was obtained for differences in reaction times between positive and neutral condition. Once again, the resulting integrated effect size was small (d = -.10) and not significant (Z = -1.02, p > .30). This small effect of positive pictures was contrasted to substantial effect sizes of negative pictures across the four semantic tasks (negative vs. neutral: d = .40, Z = 4.12, p < .001; and negative vs. positive: d = .53, Z = 5.25, p < .001). Thus, the results from the meta-analyses suggest that our findings were not due to low statistical power.

Possible Mechanisms of Inhibitory Effects of Encountering Negative Events

As we mentioned above, the attention capture effects of emotionally arousing stimuli are known to last only for 600-700 ms after encountering emotional stimuli (Bachmann & Hommuk, 2005; Bocanegra & Zeelenberg, 2009). In contrast, recent research has revealed that brief presentation of emotional stimuli can induce short-term subjective feelings of emotional states (that are sustained longer than the attentional effects), which further influence subsequent cognitive processing (e.g., Baumann & Kuhl, 2005; Dreisbach, 2006; Dreisbach & Goschke, 2004; Rudrauf, et al., 2009; see also Schmitz, De Rosa, & Anderson, 2009). Because the present study employed longer SOAs (i.e., 1300 ms) than those that elicit attentional capture effects, it seems plausible that the current results reflect the effects of subjective emotional states induced by emotional pictures, rather than the attentional effects. In line with this argument, past studies with sustained mood states revealed consistent patterns with the current findings; negative mood states impair performance in tasks requiring semantic processing (Ellis, et al., 1997; Ellis, et al., 1995; Leight & Ellis, 1981; Storbeck & Clore, 2008) but not so much in perceptual tasks (Bartolic, et al., 1999; Papousek, et al., 2009). Next, we turn to the question of why negative emotional states would interfere with semantic processing more strongly than perceptual processing.

Cognitive demands

One possibility is that semantic processing requires more cognitive effort than perceptual processing, and that negative emotional states interfere with high-demand cognitive processing more than they interfere with low-demand cognitive processing. This idea is related to arguments that mood states decrease the capacity available for other cognitive tasks (Ellis, et al., 1997; Oaksford, et al., 1996). In Study 1, however, the size task took longer than one of the semantic tasks (i.e., naturalness task), suggesting that the size task required more cognitive processing than the naturalness task. Despite such differences in cognitive demands, we found that negative picture presentation did not interfere with the size task, but did interfere with the naturalness task. In addition, we found similar interference between the commonness and the naturalness tasks, although the commonness task took longer than the naturalness task. Furthermore, in Studies 2 and 3, while we observed the reliable interference effects of negative pictures on the categorical judgments about words, neither the easy version of the color judgment (Study 2) nor the difficult version of the color judgment (Study 3) was influenced by negative picture presentation. Thus, it seems unlikely that the effects of negative emotional states on semantic task are due to higher cognitive demands in semantic tasks than in perceptual tasks.

Verbal vs. spatial processing

An alternative possibility is that negative emotional states affect subsequent verbal and visuospatial processing differently. For example, Gray and his colleagues revealed that negative mood states had stronger interference effects on a verbal working memory task than a visuospatial working memory task (Gray, 2001; Gray, et al., 2002; but see Lavric, Rippon, & Gray, 2003). These results suggest the possibility that negative emotional states impair semantic processing, because verbal processing is crucial in semantic processing. However, we observed that semantic processing was impaired regardless of the target stimuli format (i.e., either pictorial objects or verbal stimuli). Studies 2 and 3 also revealed that negative emotional pictures impaired semantic processing of verbal stimuli, but not perceptual processing of them. Previous studies also suggest that semantic processing is not always accompanied by verbal processing (Bozeat, Lambon Ralph, Patterson, Garrard, & Hodges, 2000; Riddoch & Humphreys, 1987). Thus, it seems less plausible that the effects of negative emotional states are attributable to impairment in verbal stimuli processing.

Attention focus

Another more plausible possibility comes from research on mood and attentional scope. Recent research has indicated that positive mood broadens the scope of attention, while negative mood narrows attention (Bolte, et al., 2003; Fenske & Eastwood, 2003; Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005; Gasper & Clore, 2002; Rowe, et al., 2007; Schmitz, et al., 2009). These results suggest the possibility that transient subjective emotional states induced by negative picture presentation produce narrowed attention and focal processing, and that people have difficulty considering multiple features during negative emotional states. If so, negative emotional states should inhibit cognitive processing which requires people to consider many components, whereas negative emotional states should have less impact on cognitive processing which requires only a few components/features to be considered.

Indeed, previous research suggests that semantic processing requires integrating more features and information about target stimuli than perceptual processing does. First, researchers have revealed that processing simple perceptual attributes of objects involves posterior regions of the temporal cortex or occipital lobe, which correspond to the earlier stage of the visual pathway in the brain, whereas more anterior parts of the brain (i.e., the later stage of the same pathway) implement semantic finite processing, depending on outputs of the earlier perceptual processing stages (Martin & Chao, 2001; Patterson, Nestor, & Rogers, 2007). Chouinard, Whitwell and Goodale (2009), for example, found that transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) delivered to the occipital cortex impaired judging the size of objects. In contrast, TMS delivered to inferior frontal lobe did not affect size judgments, but impaired semantic categorization of objects.

Computational models have also proposed that semantic meanings are computed by considering many features of target stimuli, such as functional (e.g., worn by women) and perceptual/ modality-specific properties (e.g., red, small: McRae, de Sa, & Seidenberg, 1997; Vigliocco, Vinson, Lewis, & Garrett, 2004). Since these models successfully replicated human behaviors during semantic processing, they support the idea that semantic processing requires people to integrate multiple features to generate each target's meaning.

Finally, a recent behavioral study suggests that semantic processing requires integration of several different perceptual features (Richter & Zwaan, 2010). Participants in these experiments were shown words with images that either matched or mismatched the color or shape of the words'referents and asked to make semantic judgments about the words (i.e., lexical decision, classification, and naming tasks). These semantic tasks were facilitated when both the color and the shape of the images matched with the actual words'referents. In contrast, neither images matching shape alone, nor those matching color alone facilitated any of these semantic tasks. These results suggest that integration of multiple perceptual features is important in semantic processing.

In summary, the literature on semantic and perceptual processing suggests that semantic processing requires considering more features than perceptual processing does. Taken together with the evidence that negative emotional states produce narrowed attention (Fenske & Eastwood, 2003), it is plausible that negative emotional states interfere with semantic processing because narrowed attention caused by negative emotional states interfere with considering multiple features, which is required by semantic processing more than perceptual processing. However, the current study obtained neither subjective nor physiological measures of participants’ emotional states during the judgment tasks. Thus, our results might not be attributable to transient emotional states induced by brief viewing of emotional pictures. Furthermore, although we observed consistent patterns across three different semantic tasks (i.e., commonness and naturalness judgments about objects; categorical judgments about words), it is not clear whether the current findings can be applied to all kinds of semantic processing. Further research should employ different types of cognitive tasks and collect participants’ physiological/subjective reactions to emotional stimuli to elucidate the mechanisms by which encountering negative events impairs subsequent semantic processing more strongly than perceptual processing.

Effects of Encountering Positive Events

In contrast to the consistent interference effects by negative pictures, the present study did not find any facilitative effects of positive pictures on either semantic or perceptual tasks. Past studies have provided mixed findings on the effects of positive moods. Several studies have indicated that positive mood broadens attention, which results in facilitative effects on subsequent cognitive processing (Bolte, et al., 2003; Isen & Daubman, 1984; Isen, et al., 1987; Isen, et al., 1985; Rowe, et al., 2007; Subramaniam, et al., 2009), while there is also research showing no effects of positive mood on subsequent cognitive processing (Leight & Ellis, 1981).

One possible reason why we did not find any facilitation effects of positive pictures is that brief presentation of positive pictures is not sufficient to produce facilitative effects of positive emotion. In fact, most of studies showing facilitative effects of positive mood employed longer and stronger mood manipulations (e.g., retrieval of past happy episodes; listening to positive music; viewing happy movies) to induce sustained positive mood states (Bolte, et al., 2003; Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005; Rowe, et al., 2007). In contrast, participants in the current study were briefly shown positive pictures, and positive picture trials were randomly mixed with negative or neutral picture trials. Although brief presentation of positive IAPS pictures can influence cognitive processing of subsequent stimuli (Dreisbach, 2006; Dreisbach & Goschke, 2004), it is still plausible that the effects of brief presentation of positive pictures are weak especially when positive pictures are randomly mixed with other emotional pictures. If positive pictures elicit weaker subjective emotional states than negative pictures, the effects of positive picture presentation may be overridden by the effects of preceding negative pictures. This might have resulted in weaker effects of the positive condition in the current study.

Another possibility is that positive mood facilitates cognitive processing especially when cognitive flexibility is required. Indeed, many studies that showed facilitative effects of positive mood used cognitive tasks that required people to search solutions flexibly in their conceptual representations (Isen & Daubman, 1984; Isen, et al., 1987; Subramaniam, et al., 2009). For example, one of the tasks frequently used in this literature is the remote association task (Isen, et al., 1987; Rowe, et al., 2007; Subramaniam, et al., 2009), where participants are provided three words that have week associations with each other (e.g., MOWER, ATOMIC, and FOREIGN), and asked to find a one-word solution related to all of the words (the solution to the above example is POWER). In this task, participants have to ignore typical semantic associations and to find semantically distant or remote associations, which should be enhanced by increased cognitive flexibility by positive mood. In contrast, participants in the present study were asked to retrieve typical semantic meanings or perceptual properties of the target stimuli. Thus, cognitive flexibility should not matter in the current tasks very much. This might have resulted in no facilitative effects of positive emotion. Thus, positive emotional states might have less influence on cognitive processing when cognitive flexibility is not needed, but they might facilitate cognitive processing when cognitive flexibility is useful. Further research is needed to determine when positive emotion facilitates, inhibits, and has no effects on subsequent cognitive processing.

Conclusion

In summary, the present study demonstrated that brief presentation of negative stimuli impairs semantic processing of subsequent stimuli. In contrast, perceptual processing of subsequent stimuli was not influenced by negative picture presentation. Consistent with previous research (Hamann, et al., 1999; Kensinger & Corkin, 2004), we found that people remembered highly arousing stimuli more than stimuli with low arousal, regardless of valence. However, arousal did not modulate the effects of negative emotional states on subsequent semantic processing. Thus, the effects of negative stimuli on semantic processing cannot be attributed to arousal. Taken together, our findings indicate that encountering negative events impairs subsequent semantic processing more than perceptual processing, regardless of arousal level. Further work following up on these findings might help elucidate why strong negative emotions associated with acute stress (Alexander, et al., 2007; Buchanan & Tranel, 2008) or depression (Fossati, Guillaume, Ergis, & Allialaire, 2003; Robinson, et al., 2006) cause deficits in tasks requiring semantic processing.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows (19-8978) and by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (R01AG025340). Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Michiko Sakaki, 3715 McClintock Ave., University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/emo

Recent research has shown that positive mood state broadens attention more than negative or neutral mood (Fenske & Eastwood, 2003; Fredrickson & Branigan, 2005; Rowe, et al., 2007), suggesting that participants would have better memory for contextual information after positive stimuli than negative or neutral ones. To address such effects of positive stimuli, on each trial, participants were presented with the target object with three distractor objects. At the end of the experiment, then, we tested participants'memory of the objects. This test included 216 objects; half of them were new, one fourth of them were the target objects that participants made judgments, the remaining objects were the distractor objects (for each trial, we randomly selected one of the three distractor objects and used them in the test session). Participants were asked to make a judgment about whether they had seen each object or not. Contrary to the prediction, however, a 3 (task: natural, common, size) X 3 (valence: positive, negative, neutral) ANOVA on the hit rates for the distractor objects did not find any significant effects. A similar 3 (task) X 3 (valence) ANOVA on the hit rates for the target objects revealed a main effect of task, F (2, 40) = 12.03, p < .01, reflecting that the commonness task (M = .92) produced better memory than the size task (M = .81) and the naturalness task (M = .80), t (40) = 4.04, SE = .03, p < .05, t (40) = 4.43, SEs = .03, p < .05. However, neither the effects of valence, nor the interaction between valence and task were significant (p > .30). These results are in line with recent findings that emotion does not influence memory for nearby items when they are spatially distinctive from target stimuli (Mather, Gorlick, & Nesmith, 2009).

While outliers should be defined based on each condition in each participant (Ratcliff, 1993), the number of trials per condition was small in this study. Therefore, we did not determine any outliers in reaction times. To address possible influences of undetected outliers, similar analyses were performed on log-transformed reaction times (Ratcliff, 1993). The analyses confirmed a significant effect of valence in the commonness task, F (2, 40) = 4.66, p < .05, R2 = .02, and in the naturalness task, F (2, 40) = 3.59, p < .05, R2 = .06. In the naturalness and commonness tasks, participants produced longer reaction times after negative modulators than after neutral, ts (40) = 2.56, 2.09, SEs = 0.04, ps < .05 or positive modulators, ts (40) = 2.72, 2.50, SEs = 0.04, ps < .05. In contrast, there was no significant effect of valence in the size task (p > .35).

One might be also concerned that the results were attributable to a few specific pictures used in the experiment. To address the effects of pictures, a follow-up 3 (task) X 18 (picture) ANOVA was carried out on the reaction times for each valence category. Neither effects of pictures (ps > .20), nor the interactions between pictures and task were significant (ps > .50). In addition, another ANOVA using each IAPS picture as a unit of the analysis confirmed a task X valence interaction on the reaction times, F (4, 153) = 2.40, p = .053. This result again suggests that the current results are not due to specific picture effects.

The false alarm rates did not significantly differ across valence categories (p > .30). Recognition accuracy measures were also obtained for each emotion category (i.e., a hit rate for each valence category minus a false alarm rate for the valence category). Consistent with the hit rate analyses, a one-way ANOVA on the corrected recognition accuracy measure produced a significant main effect of valence (Figure 3), F (2, 40) = 26.08, p < .01. Participants had more accurate memory for negative (M =.76) and positive pictures (M =.69) than neutral pictures (M =.53; ps < .01). There was no significant difference between positive and negative pictures (p > 12).

Neither main effects of the stimulus sets, nor interactions between stimulus sets and task were significant in any of the valence categories.

Similar analyses performed on log-transformed reaction times confirmed a significant effect of valence in the semantic task, F (2, 90) = 6.56, p < .01, R2 = .004, but not in the perceptual task (p > .20). In the semantic task, participants’ reaction times were slower after negative modulators than after neutral or positive distracters, ts (90) = 2.19, 3.59, SEs = 0.01, ps < .05.

Similar analyses on log-transformed reaction times confirmed a significant effect of valence in the semantic task, F (2, 89) = 9.53, p < .01, R2 = .04, but not in the perceptual task (p > .60). In the semantic task, participants’ reaction times were slower after negative modulators than after neutral or positive distracters, ts (89) = 3.67, 3.89, SEs = 0.01, ps < .01. A follow-up analysis was also preformed to address the effects of picture stimulus sets. However, neither main effects of the stimulus sets, nor interactions between stimulus sets and task were significant in any of the valence categories.

A similar meta-analysis was performed to address differences between negative and positive conditions in the perceptual tasks. Once again, the resulting effect size estimate was small (d = .08) and not significant (Z = 0.7, p > .35). This suggests that reaction times in the perceptual tasks did not differ between negative and positive conditions, even if we combined the results from the three studies.

References

- Alexander JK, Hillier A, Smith RM, Tivarus ME, Beversdorf DQ. Beta-adrenergic modulation of cognitive flexibility during stress. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2007;19:468–478. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.3.468. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.3.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson AK. Affective influences on the attentional dynamics supporting awareness. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2005;134:258–281. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.134.2.258. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.134.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquino JM, Arnell KM. Attention and the processing of emotional words: Dissociating effects of arousal. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2007;14:430–435. doi: 10.3758/bf03194084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnell KM, Killman KV, Fijavz D. Blinded by emotion : Target misses follow attention capture by arousing distractors in rsvp. Emotion. 2007;7:465–477. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.3.465. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.3.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann T, Hommuk K. How backward masking becomes attentional blink. Psychological Science. 2005;16:740–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01604.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard P, Ramponi C, Battye G, Mackintosh B. Anxiety and the deployment of visual attention over time. Visual Cognition. 2005;12:181–211. doi: 10.1080/13506280444000139. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolic E, Basso M, Schefft B, Glauser T, Titanic-Schefft M. Effects of experimentally-induced emotional states on frontal lobe cognitive task performance. Neuropsychologia. 1999;37:677–683. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(98)00123-7. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3932(98)00123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann N, Kuhl J. Positive affect and flexibility: Overcoming the precedence of global over local processing of visual information. Motivation and Emotion. 2005;29:123–134. [Google Scholar]