Abstract

A 66-year-old female presented with a 1-month history of dyspepsia. An initial upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with biopsy revealed a low-grade mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. A rapid urease test was positive for Helicobacter pylori. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and computed tomography (CT) revealed a 30×15-mm lymph node (LN) in the subcarinal area. Histopathologic and phenotypic analyses of the biopsy specimens obtained by EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration revealed a MALT lymphoma, and the patient was diagnosed with a stage 4E gastric MALT lymphoma. One year after H. pylori eradication, the lesion had disappeared, as demonstrated by endoscopy with biopsy, CT, fusion whole-body positron emission tomography, and EUS. Here, we describe a patient with gastric MALT lymphoma that metastasized to the mediastinal LN and regressed following H. pylori eradication.

Keywords: Marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, Stomach

INTRODUCTION

The most common primary lymphoma of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma.1 Although 90% of gastric MALT lymphomas are related to the presence of Helicobacter pylori,2 areas other than the GI tract may be affected. We describe here a patient with gastric MALT lymphoma that metastasized to the mediastinal lymph node (LN) and regressed following H. pylori eradication.

CASE REPORT

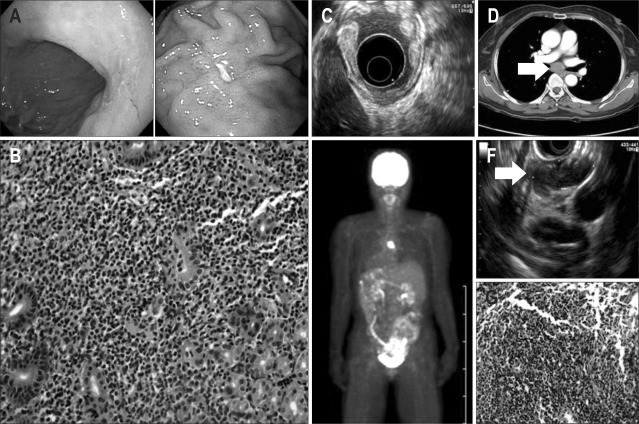

A 66-year-old female presented with a 1-month history of dyspepsia. An initial upper GI endoscopy showed a shallow ulcerative lesion in the gastric high body and a hyperemic lesion in the low body (Fig. 1A). A rapid urease test was positive for H. pylori. Histologic sections of the high and low bodies showed patchy infiltration of small lymphocytes into the lamina propria and lymphoepithelial lesions; the lymphocytes were focally aggressive toward the gland (Fig. 1B). Phenotypic analysis showed that the lesion was positive for CD20, but negative for CD3, CD5, CD10, and Bcl-6, and that its proliferation rate was <2%, as shown by MIB1 (Ki-67) antibody analysis. Based on these histopathological and phenotypic features, the patient was diagnosed with low-grade MALT lymphoma. Staging procedures were performed. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) revealed hypoechoic disruption of the mucosal and submucosal layers; moreover, the fourth layer was preserved and there was no evidence of locoregional lymphadenopathy (u-T1smN0) (Fig. 1C). A computed tomography (CT) scan showed a huge LN, about 30×15 mm in size, in the subcarinal area (Fig. 1D). Fusion whole body positron emission tomography (PET) showed a hypermetabolic lesion, suggestive of a malignant lesion, on the subcarinal area. (Fig. 1E). Bone marrow biopsy findings were normal. EUS of the subcarinal lesion showed 32×12 mm LN. Histopathological and phenotypic analysis of a biopsy sample obtained by EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (Fig. 1F) showed that the lesion was a MALT lymphoma (Fig. 1G). The patient was diagnosed with a stage 4E gastric MALT lymphoma. For H. pylori eradication, the patient was treated with a 14-day course of amoxicillin 2,000 mg a day, clarithromycin 1,000 mg a day and pantoprazole 80 mg a day.

Fig. 1.

Initial diagnostic tests. (A) Initial upper gastrointestinal endoscopy displaying a shallow ulcerative lesion in the gastric high body and a hyperemic lesion in the gastric low body. (B) Histopathologic examination of a gastric biopsy specimen displaying patchy infiltration of small lymphocytes and lymphoepithelial lesions in the lamina propria, which suggest the existence of a mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma (H&E stain, ×400). (C) Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) analysis displaying hypoechoic disruption of the mucosal and submucosal layers. (D) Computed tomography scan displaying a 30×15 mm lymph node (LN) in the subcarinal area. (E) Positron emission tomography analysis displaying a hypermetabolic lesion suggestive of a malignant lesion in the subcarinal area. (F) EUS analysis of the subcarinal lesion revealing a 32×12 mm LN. (G) Histopathologic examination of LN tissue, with the patchy infiltration of small lymphocytes, suggesting a MALT lymphoma (H&E stain, ×400).

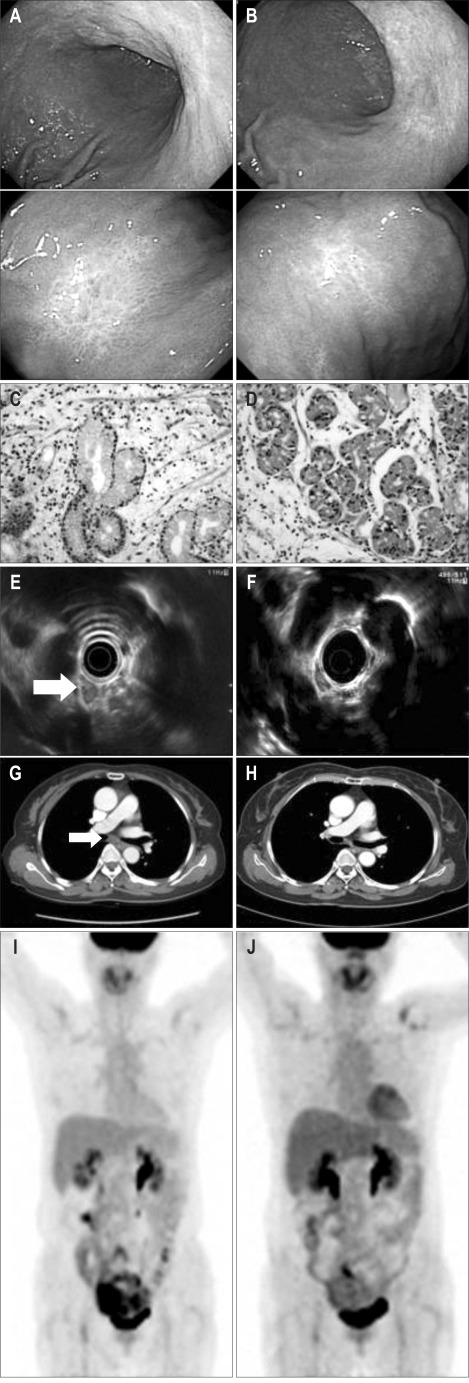

An endoscopy performed 2 months after treatment showed that the gastric high and low bodies were pale and flat, with no evidence of lymphoma infiltration (Fig. 2A and C). EUS of the subcarinal area and CT showed that the LN had decreased markedly in size, to 12×11 mm (Fig. 2E and G). Follow-up PET showed no significantly abnormal hypermetabolic lesions (Fig. 2I).

Fig. 2.

Follow-up evaluations 2 months (A, C, E, G, I) and 1 year (B, D, F, H, J) after Helicobacter pylori eradication. (A, C) Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, displaying pale, flat gastric high and low bodies without lymphoma infiltration (H&E stain, ×400). (E, G) Endoscopic ultrasound and computed tomography scans of the subcarinal area, displaying a markedly smaller lymph node, sized 12×11 mm. (I) Positron emission tomography analysis displaying no significantly abnormal hypermetabolic lesions. (B, D, F, H, J) All findings were unremarkable.

One year after treatment, all assessments, including endoscopy with biopsy, CT, PET, and EUS, showed normal results (Fig. 2B, D, F, H and J). At present, 14 months later, the patient remains in complete remission.

DISCUSSION

More than 90% of gastric lymphomas are related to the presence of H. pylori; hence, eradication of H. pylori is the favored initial treatment for patients with early-stage H. pylori-positive gastric MALT lymphoma.2

However, the association between extragastric MALT lymphoma and H. pylori is not clear. Although several case reports have described the regression of extragastric MALT lymphomas after H. pylori eradication,3,4 one study showed that the majority of patients with extragastric MALT lymphoma did not benefit from H. pylori eradication.5

In addition, there have been a few case reports showing that H. pylori eradication has led to the regression of advanced gastric MALT lymphomas simultaneously involving two or more organs other than the stomach.6,7 Recirculation of H. pylori - specific T-cells from the stomach to other organs via the blood or lymphatic system may trigger an inflammatory response in other MALT-lymphoma containing organs.3,4,6,7 Alternatively, abnormal cells may spread from the stomach to other organs via the blood or lymphatic system.5,8

H. pylori eradication may also lead to the regression of secondarily involved perigastric LN and bone marrow. However, our patient was different, in that H. pylori eradication led to the regression of a mediastinal LN.

The treatment for advanced gastric MALT lymphoma has not been clearly defined. Treatment is usually similar to that for patients with other advanced-stage indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma.9 Our findings, however, indicate that H. pylori eradication should be the first treatment in patients presenting with H. pylori-associated advanced gastric MALT lymphoma. Further molecular characterization of these tumors is necessary to determine the most suitable therapeutic strategy.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Cogliatti SB, Schmid U, Schumacher U, et al. Primary B-cell gastric lymphoma: a clinicopathological study of 145 patients. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:1159–1170. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90063-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wotherspoon AC, Doglioni C, Diss TC, et al. Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1993;342:575–577. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91409-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iwai H, Nakamichi N, Nakae K, et al. Parotid mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma regression after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:1491–1494. doi: 10.1002/lary.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagashima R, Takeda H, Maeda K, Ohno S, Takahashi T. Regression of duodenal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1674–1678. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grunberger B, Wohrer S, Streubel B, et al. Antibiotic treatment is not effective in patients infected with Helicobacter pylori suffering from extragastric MALT lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1370–1375. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.9025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caletti G, Togliani T, Fusaroli P, et al. Consecutive regression of concurrent laryngeal and gastric MALT lymphoma after anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:537–543. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raderer M, Pfeffel F, Pohl G, Mannhalter C, Valencak J, Chott A. Regression of colonic low grade B cell lymphoma of the mucosa associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 2000;46:133–135. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.1.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du MQ, Xu CF, Diss TC, et al. Intestinal dissemination of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Blood. 1996;88:4445–4451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zelenetz AD, Abramson JS, Advani RH, et al. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:288–334. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]