Abstract

The nuclear bile acid receptor, Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR), is an important transcriptional regulator of liver metabolism. Despite recent advances in understanding its functions, how FXR regulates genomic targets and whether the transcriptional regulation by FXR is altered in obesity remain largely unknown. Here, we analyzed hepatic genome-wide binding sites of FXR in normal and dietary obese mice by chromatin immunoprecipitation-sequencing (ChIP-seq) analysis. A total of 15,263 and 5,272 FXR binding sites were identified in livers of normal and obese mice, respectively, after a short one hour treatment with the synthetic FXR agonist, GW4064. Of these sites, 7,440 and 2,344 were detected uniquely in normal and obese mice. FXR binding sites were localized mostly in intergenic and intron regions at an IR1 motif in both groups, but also clustered within 1 kb of transcription start sites. FXR binding sites were detected near previously unknown target genes with novel functions, including diverse cellular signaling pathways, apoptosis, autophagy, hypoxia, inflammation, RNA processing, metabolism of amino acids, and transcriptional regulators. Further analyses of randomly selected genes from both normal and obese mice suggested more FXR binding sites are likely functionally inactive in obesity. Surprisingly, occupancies of FXR, RXRα, RNA polymerase II, and epigenetic gene activation and repression histone marks, and mRNA levels of genes examined, suggested that direct gene repression by agonist-activated FXR is common. Comparison of genomic FXR binding sites in normal and obese mice further suggested that FXR transcriptional signaling is altered in dietary obese mice, which may underlie aberrant metabolism and liver function in obesity.

Keywords: ChIP-seq, fatty liver, bile acid, GW4064, histone modification

Introductory Statement

Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR, NR1H4) belongs to the nuclear receptor superfamily (1-3). As the primary biosensor for endogenous bile acids, FXR plays a crucial role in maintaining bile acid homeostasis by regulating expression of numerous genes involved in bile acid metabolic pathways, including biosynthesis and transport of bile acids mainly in liver and intestine (2-4). In addition, recent studies have revealed new functions of FXR in triglyceride/glucose metabolism, liver regeneration, tumor suppression, and anti-inflammation (3, 5-10). Despite these recent advances in understanding functions of FXR, how FXR activates or represses its genomic targets is still poorly understood.

Ligand-activated FXR binds FXR response elements (FXREs) in DNA as a heterodimer with RXRα, and activates transcription of target genes (1-3). FXR represses a group of target genes indirectly through the induction of an orphan nuclear receptor, Small Heterodimer Partner (SHP) (11-14). The FXR/SHP pathway has been shown to play an important role in the negative feedback regulation of bile acid biosynthesis and in hepatic triglyceride metabolism (11-13, 15), although the importance of FXR-independent bile acid-activated signaling pathways in the regulation of hepatic metabolism has been demonstrated (16-18). In addition to indirect gene repression via SHP, whether FXR can directly inhibit genomic targets is largely unknown.

In recent studies, we have shown the importance of post-translational modifications in modulating the levels and activities of transcriptional factors and cofactors in the regulation of hepatic metabolism (19-23). In particular, we have shown that acetylation of FXR is dynamically regulated by p300 acetylase and SIRT1 deacetylase under physiological conditions (20, 21). While FXR acetylation increased its stability, it dampened FXR's transactivation ability by inhibiting binding of the FXR/RXRα heterodimer to DNA (20). Remarkably, FXR acetylation is highly elevated in fatty livers of genetic and dietary obese mice (20). These findings raised an important question of whether genomic targets regulated by FXR are altered in obesity, which might be associated with abnormal metabolism and aberrant liver functions.

To determine whether hepatic transcriptional regulation of FXR target genes is changed in obesity, in this study, we identified and compared genomic binding of FXR in normal and dietary obese mice by ChIP-seq analysis and further investigated whether ligand-activated FXR can either directly activate or repress potential target genes.

Experimental Procedures

Animals

Six week-old male BALB/c mice were fed normal chow or high fat diet (42% fat, purchased from Harlan Teklad, TD88137) for 20 weeks. Increased body weights were monitored and development of fatty liver was also confirmed by oil red staining and by measuring mRNA levels of lipogenic genes (supplemental information, Fig. S1). Hepatic expression of FXR in normal and obese mice were also examined (Fig. S2). Mice were i.p. injected with vehicle or GW4064 (30 mg/kg in corn oil) at 9:00 am and 1 h later, livers were collected for ChIP-seq analysis.

ChIP assays and genomic sequencing (ChIP-seq)

Detailed procedures for ChIP-seq analysis are described in supplemental information (Fig. S3). Briefly, genomic samples from 4 mice per each group were immunoprecipitated by antibodies for FXR (mixture of sc-1204 and sc-13063) or control IgG. Twenty ng of DNA from the immunoprecipitated chromatin pooled from 4 independent ChIP assays was subjected to deep genomic sequencing using the Illumina/Solexa Genome Analyzer II (Biotechnology Center, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign).

Location of binding peaks and Gene ontology (GO) analysis

FXR binding peaks were subjected to analysis with CisGenome and FDR (<0.001) and ratio of FXR binding to control IgG peaks (>5) were used to detect binding sites. FXR binding sites were analyzed to identify the gene locations of the sites in the mouse genome. A list of all genes with FXR peaks within ± 10 kb of the genes was generated using CisGenome. GO analysis of potential FXR target genes was conducted by using the NIH program DAVID for functional grouping of binding genes.

Motif Analysis

The consensus motifs within the 250 top-scoring FXR binding peaks were determined using the program MEME. The coordinates of each peak were set to collect motif lengths of 6 to 20 bp. Comparison of motifs against a database of known FXRE's was done in TOMTOM generating p-values of the similarity score, scoring details, and a logo alignment for each match.

Re-ChIP, ChIP, and q-RTPCR analyses

Re-ChIP assays were performed as described (21, 23). Briefly, liver chromatin was immunoprecipitated with FXR antibody (sc-1204, goat polyclonal) first and then washed and eluted and re-precipitated using rabbit polyclonal antibodies for FXR (sc-13063), RXRα (sc-553), RNA pol II (sc-9001), histone H3K9/K14 acetylation (Upstate Biotech/Millipore,06-599), and control IgG. Standard ChIP assays were also performed using antibodies for H3K9 methylation (Upstate Biotech/Millipore, 07-521) and H3K27 methylation (Abcam, 6002). Then, genomic DNA was subjected to q-PCR using primer sets (Fig. S4A). For gene expression q-RTPCR studies, total RNA was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen), and q-RTPCR was performed using primer sets (Fig. S4B).

Results

Genome-wide profiling of hepatic FXR binding sites in normal and obese mice

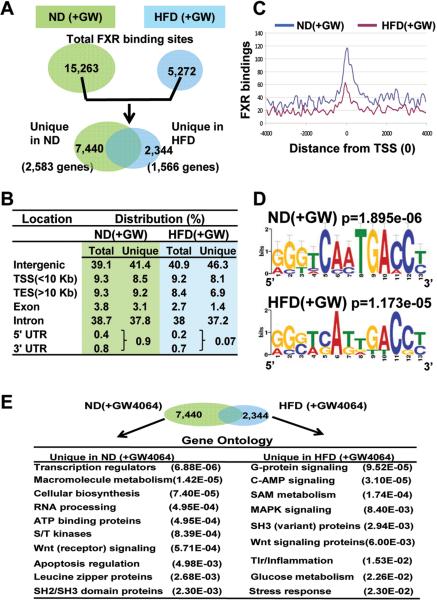

To identify genome-wide hepatic FXR binding sites in normal and obese mice, mice were fed normal or high fat chow for 20 weeks and then, treated for a short time (1 h) with a synthetic FXR agonist, GW4064, to activate FXR signaling. ChIP assays from liver chromatin were performed with FXR antibody or control IgG. The quality of the ChIP was confirmed by the increased binding of FXR to known FXR targets, Shp and Ostβ and increased levels of Shp mRNA also confirmed the effectiveness of the GW4064 treatment (Fig. S5). The ChIP-seq analysis generated 2.98 and 3.97 million reads for GW4064-treated normal and obese mice, respectively (Fig. S6). FXR binding peak analysis, with stringent false discovery rate (FDR) cutoffs of <0.001 and the elimination of peaks observed also with control IgG, identified a total of 15,263 and 5,272 FXR binding sites in GW4064-treated normal and obese mice, respectively (Fig. 1A, top). Of these sites, 7440 or 2,344 were uniquely detected in normal or high fat dietary obese mice (Fig. 1A, bottom). The number of overlapping sites in the normal mice was greater than that in the obese mice, because some of the FXR binding sites in the obese group overlapped with 2 or more binding sites in the normal group.

Fig. 1. Unique FXR binding sites in normal and obese mice.

(A) Venn diagrams showing the number of FXR binding sites in normal or dietary obese mice (top) and the number of sites uniquely detected in either normal (ND) or obese (HFD) mice treated with GW4064 for 1 h (bottom). The numbers of genes near the unique FXR binding sites in normal and obese mice are shown in parenthesis. (B) Distribution of total or unique FXR binding sites in GW4064-treated normal and obese mice. FXR sites located >10 kb from genes were assigned to intergenic regions. (C) Distance from the center of each FXR binding peak to the transcriptional start site (TSS). (D) A logo showing the 13 nucleotide consensus IR1 motif from the top 250 FXR peaks in GW4064-treated normal and obese mice. The size of the letters is proportional to the frequency of occurrence. (E) Gene ontology categories of the genes nearest to unique FXR binding sites in GW4064-treated normal or obese mice. Genes located within 10 kb of FXR sites were identified using the program DAVID.

Validation of ChIP-seq

To validate the ChIP-seq data, we randomly selected FXR binding sites. Neither the size nor position of FXR binding peaks was considered to select binding sites for validation and follow-up studies. ChIP assays revealed that binding to 24 out of 27 sites in normal mice and 20 out of 21 in obese mice was enriched least 1.8-fold relative to vehicle-treated mice (Fig. S7, S8), confirming binding to about 90% of these sites and validating the accuracy of the ChIP-seq analysis.

Unique FXR binding sites in normal or obese mice suggest altered transcriptional signaling in obesity

The central question of this study was to determine whether FXR regulation might be altered in obesity, which could underlie abnormal liver function and metabolism. Therefore, we focused on the differences in FXR binding between GW4064-treated normal and obese mice. Notably, 7,440 of the total 15,632 FXR binding sites in normal mice were unique in these mice, while 2,344 of the total 5,272 sites in obese mice were unique (Fig. 1A). Potential FXR target genes were identified based on the criteria that an FXR binding site was within 10 kb of the gene. FXR binding sites corresponded to 2,583 or 1,566 potential target genes unique in normal or obese mice (Fig. 1A). These results indicate that nearly half of total FXR binding sites are unique in normal or obese mice, suggesting that transcriptional regulation patterns by FXR are likely altered in obesity.

Distribution of FXR binding sites and motif analysis

Binding sites of FXR were predominantly distributed in intron (38%) and intergenic (40%) regions in both groups of mice (Fig. 1B). There was a marked reduction of FXR binding sites to 5’UTR and 3’UTR regions in obese mice, and the genes with binding sites uniquely in the UTR regions of normal or obese mice are listed in Fig. S9. Although a relatively small fraction of the total binding sites, a peak of total or unique FXR binding sites was observed within 1 kb of the TSS in both groups (Fig. 1C, Fig. S10). The highest-scored binding motif for the 250 top-scoring FXR binding sites was an IR1 motif with similar preferred sequences in both normal and obese mice (Fig. 1D).

Functional gene ontology analysis

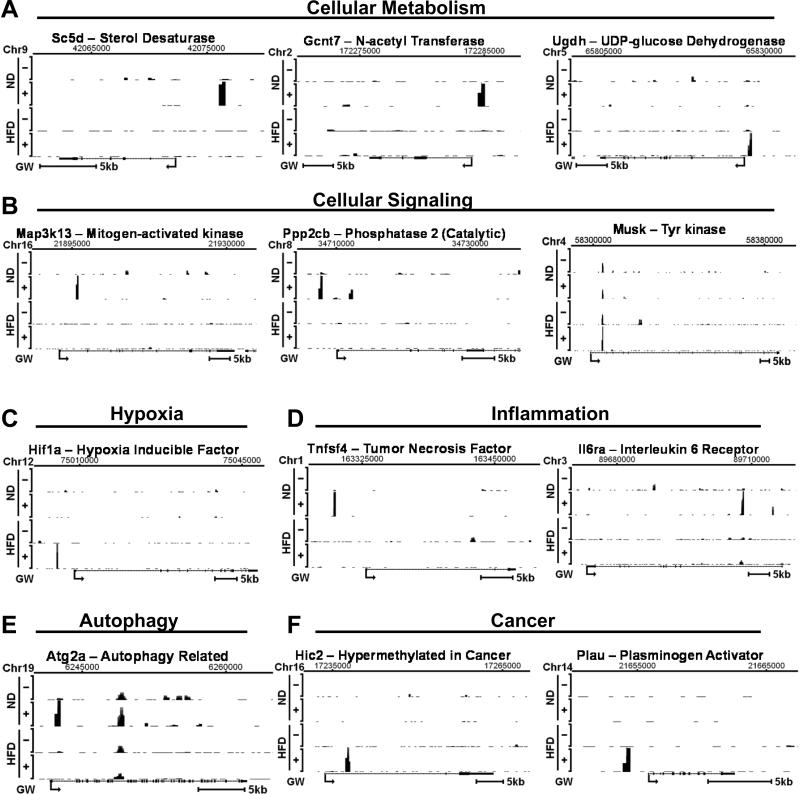

To identify possible biological functions regulated by FXR, potential FXR target genes were assigned to functional groups by gene ontology analysis. Many potential FXR target genes represent previously unknown functions, such as, cellular signaling, hypoxia, autophagy, apoptosis, RNA processing, and many transcriptional regulators. Notably, genes encoding components of diverse cellular signaling pathways, such as, G-protein signaling, Wnt signaling, MAPK signaling, numerous kinases, and phosphatases were identified (Fig. 1E). These results suggest that previously unknown functions of FXR, particularly in the regulation of cellular signaling pathways, are different in normal and obese mice, which could underlie abnormal regulation in obesity. Overall, these gene ontology studies, together with the analysis of genome-wide FXR binding, reveal novel potential FXR target genes, suggesting that FXR may have much broader biological functions than previously appreciated. Examples of FXR binding peaks detected near selected genes unique in either normal or obese mice are shown in Fig. 2 and Fig. S11. These analyses reveal previously unrecognized genomic targets of FXR in liver with novel biological functions, suggesting that transcriptional patterns and biological pathways regulated by ligand-activated FXR are likely altered in obesity.

Fig. 2. Effects of GW4064 on FXR binding in normal or dietary obese mice by ChIP-seq.

(A-F) ChIP-seq data showing FXR binding sites in vehicle- or GW4064-treated normal and obese mice are displayed using the UCSC genome browser. Chromosomal locations are shown at the top of each display. The Y-axis shows the numbers of mapped sequence tags with the maximum ranging from 160 to 485. Gene positions are indicated at the bottom of each display with the arrows indicating the transcriptional start site.

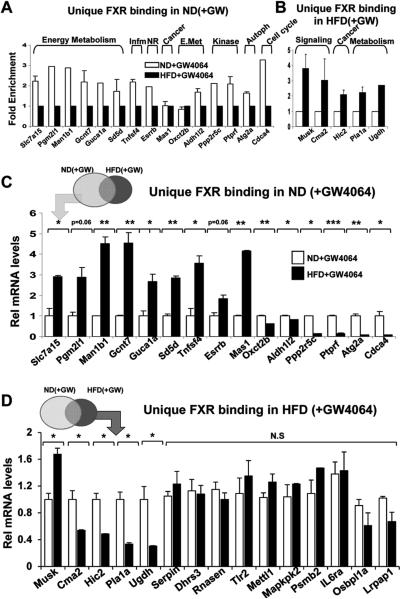

Correlation of FXR binding with relative gene expression

To initially examine whether differences in FXR binding correlates with the relative gene expression, ChIP and q-RTPCR studies were performed for randomly selected potential target genes. FXR binding was detected by ChIP analysis in 86% (13 out of 15 genes) or 100% (5 out of 5 genes) of these target genes unique to normal or obese mice, which validated the accuracy of the ChIP-seq analysis (Fig. 3A, B). For 15 genes with FXR binding unique to normal mice, mRNA levels of nearly all of the genes were changed compared to obese mice (Fig. 3C), while only 5 of 14 genes with FXR binding unique in obese mice showed significant changes in mRNA levels (Fig. 3D). These results suggest either that FXR binding sites are likely not functional for a large fraction of the genes in obese mice, or that factors other than FXR may contribute to the overall difference in expression of these genes in obesity.

Fig. 3. Correlation of FXR binding with expression of the nearest genes.

(A, B) To validate FXR binding sites unique to GW4064-treated normal or obese mice, normal or dietary obese mice were treated with GW4064 for 1 h and livers were collected. Occupancies of FXR were examined at randomly selected genes by ChIP assays in normal (ND) (A) or high fat diet-induced obese (HFD) (B) mice. Genomic DNA from 3 independently performed ChIP assays from 3 mice were pooled and used for the q-PCR analysis. (C, D) The mRNA levels of genes near the unique FXR binding sites in normal (A) or high fat diet-induced obese (B) mice treated with GW4064 overnight were measured by q-RTPCR. Statistical significance was determined by the Student's t-test from 9 q-RTPCR readings of 3 replicate assays each for 3 mice (SEM, n=9). (*,p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***,p<0.001 and NS, statistically not significant).

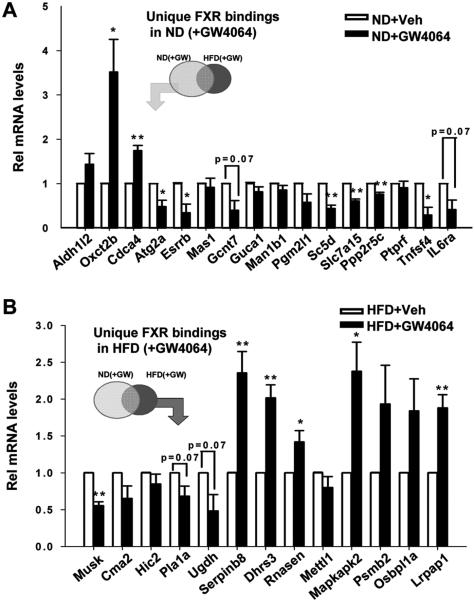

Effects of GW4064 treatment on potential FXR target gene expression

To correlate the binding of FXR at a gene with its expression, mRNA levels of randomly selected genes with FXR binding sites were measured. For genes with FXR binding restricted to normal mice, GW4064 treatment overnight significantly increased mRNA in only 2 genes of 16 examined, while unexpectedly, mRNA levels were markedly reduced in 8 genes (Fig. 4A). Similar trends were observed from the samples treated with GW4064 for a short time only 1 h (Fig. S12), which is consistent with a direct effect of FXR on gene expression rather than delayed indirect responses. For the genes unique to obese mice, mRNA levels were increased significantly for 5 of 13 genes and decreased significantly in one (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that a large fraction of potential FXR target genes examined are likely repressed by agonist-activated FXR.

Fig. 4. Effects of GW4064 treatment on mRNA levels of potential FXR target genes.

Mice were treated with vehicle or GW4064 overnight (16 h) and q-RTPCR analysis was done to measure mRNA levels of genes nearest to unique FXR binding sites in normal (A) or high fat diet-induced obese (B) mice. The mRNA levels of genes nearest to FXR binding sites that were unique to normal mice were determined by q-RTPCR. Statistical significance was determined by the Student's t-test from 11 q-RTPCR readings from 4 mice (SEM, n=11). (*,p<0.05; **, p<0.01).

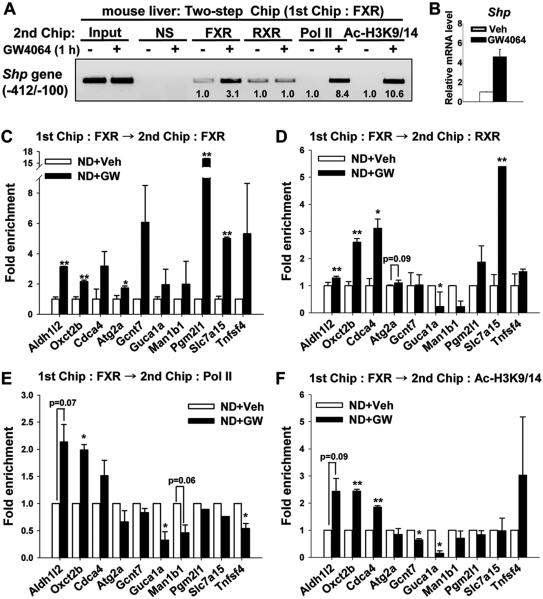

Direct gene repression by agonist-activated FXR is likely common

Direct gene repression by agonist-activated FXR was expected to be rare since nearly all of the direct FXR target genes have been reported to be activated (2, 3, 19). We, therefore, further examined epigenetic histone markers of gene activation and repression, as well as, occupancy by RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) (21, 24, 25). Genes with increased expression, as well as representative genes that were repressed or not significantly affected (Fig. 4A) were examined. Two-step re-ChIP and q-RTPCR analyses were performed and the known FXR target gene, Shp, was first analyzed as a control. Co-occupancy of RNAPII with FXR and acetylated histone H3K9/K14 at the Shp promoter was increased, whereas co-occupancy of RXRαwith FXR was not changed after GW4064 treatment (Fig. 5A). As expected, the mRNA levels for Shp were increased after a 1h treatment with GW4064 (Fig. 5B). For selected potential FXR genomic targets, occupancy of FXR was increased in nearly all of the genes examined after GW4064 treatment (Fig. 5C). For the three genes with increased mRNA levels after GW4064 treatment (Fig. 4A), Aldh1/2, Oxct2b, and Cdca4, co-occupancy of RXRα and RNAPII with FXR was increased and acetylated histone H3K9/K14 levels were increased as expected for activated genes (Fig. 5D-F). For the remaining genes, RNAPII occupancy and acetylated histone H3 levels were decreased or unchanged, which would be consistent with either no induction or suppression of these genes as observed from the mRNA levels.

Fig. 5. Effects of GW4064 treatment on co-occupancy of FXR, RXRα, RNAPII, and acetylated histone H3K9/K14 at potential FXR target genes.

Mice were treated with vehicle or GW4064 for 1 h and livers were collected for two-step re-ChIP (A, C-F) and q-RTPCR (B) analyses. Initial ChIP assays were done using the FXR antibody (goat polyclonal), and then immunoprecipitated chromatin was eluted and second ChIP assays were performed using rabbit polyclonal antibodies to FXR, RXRα, RNAPII, and acetylated histone H3K9/K14. Occupancy of these proteins and acetylated histone H3K9/K14 levels at the potential FXR target genes (C-F), as well as the Shp gene promoter as a positive control (A), were examined by q-PCR and semi-quantitative PCR of the immunoprecipitated chromatin DNA, respectively. In (A) band intensities were determined using Image J and the intensities relative to vehicle-treated mice are indicated below the bands. (C-F) The values of the samples from mice treated with GW4064 are normalized relative to those from mice treated with vehicle. Consistent results were observed for q-PCR readings from triplicate re-ChIP assays each from 2 mice. Statistical significance was determined by the Student's t-test (SEM, n=6). (*p<0.05; **, p<0.01; and NS, statistically not significant).

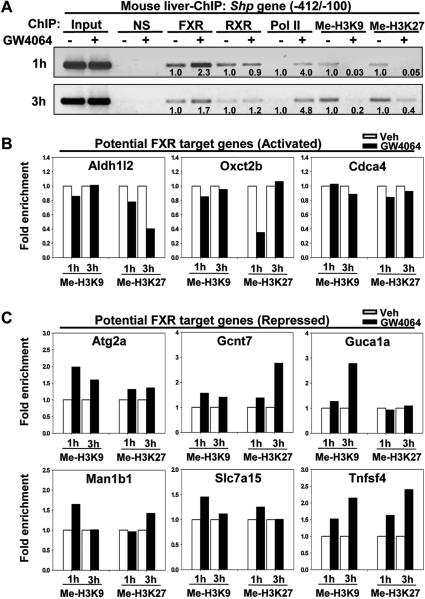

Finally, to directly determine whether binding of agonist-activated FXR leads to repression of genes examined, ChIP assays were performed to measure the levels of known epigenetic histone marks for gene repression, such as, H3K9 methylation and H3K27 methylation (24, 25). After treatment with GW4064, occupancies of FXR and RNAPII were increased and methylated H3K9 and H3K27 levels were decreased at the control Shp gene promoter (Fig. 6A). For the potential FXR target genes with increased expression, such as, Ald1/2, Oxc2b, and Cdca4, the levels of repressed histone marks, H3K27 and H3K9 were unchanged or decreased after GW4064 treatment (Fig. 6B). In contrast, levels of gene repression histone marks, either H3K9 methylation, H3K27 methylation, or both, were markedly increased for the FXR target genes with decreased expression after either a 1h or 3 h treatment with GW4064 (Fig. 6C). These results are consistent with decreased mRNA levels (Fig. 4A) and decreased occupancy of RNAPII and acetylated H3 levels at those genes (Fig. 5C-F). Collectively, these studies suggest that a large fraction of the agonist-activated FXR target genes examined is directly repressed. Since FXR was shown to increase its target genes in nearly all previous studies and to repress some target genes indirectly through the induction of SHP (3, 4, 11, 14), our finding that direct gene repression by FXR is common is unexpected.

Fig. 6. Gene repression histone marks are increased at the potential FXR target genes after GW4064 treatment.

Normal mice were treated with vehicle or GW4064 for either 1 h or 3 h and livers were collected for ChIP analysis. (A) As a control, occupancy of FXR, RXRα, RNAPII, and levels of H3K9 methylation and H3K27 methylation were detected at the Shp gene promoter. In (A), band intensities were determined using Image J and the intensities relative to vehicle-treated mice are indicated below the bands. (B, C) Gene repression histone marks, H3K9 methylation and H3K27 methylation, were detected at the potential FXR target genes with increased expression (B) or decreased expression (C) after GW4064 treatment. The values of the samples from GW4064-treated mice are normalized relative to those from vehicle-treated mice. Each bar represents the average of three q-PCR readings from each ChIP assay.

Discussion

In this study, ChIP-seq analysis of hepatic genomic binding of agonist-activated FXR in normal and obese mice resulted in two major findings. First, of the total hepatic FXR binding sites, nearly half of the sites were unique to normal or obese mice, implying altered FXR transcriptional signaling in obesity. Second, further analyses utilizing ChIP and q-RTPCR assays suggested that a large fraction of FXR target genes examined are directly repressed by ligand-activated FXR.

About 80% of identified FXR binding sites are localized in intergenic and intron regions, at a consensus IR1 motif, in normal and obese mice. These findings are consistent with recently reported ChIP-seq analysis of FXR binding in normal mice (26-28). Thomas et al., for the first time, identified and compared genomic FXR binding sites in liver and intestine in mice treated with GW4064. Interestingly, only 11% of total FXR binding sites were shared between liver and intestine, demonstrating tissue-specific FXR target genes (26). Chong et al. identified FXR binding sites in mouse hepatic chromatin and showed that binding sites for LRH-1 were enriched near the asymmetric IR1 FXR site and that LRH-1 and FXR can co-activate gene expression (27). Lee et al. also identified functional FXR sites within promoters, introns, or intragenic regions of selected genes involved in xenobiotic metabolism, suggesting a role for FXR in liver protection against toxic substances, such as, acetaminophen (28).

This current study reveals numerous previously unknown potential FXR target genes unique in normal and obese mice and categorization of these genes identifies new functions, suggesting that biological pathways potentially regulated by FXR are altered in obesity. We have shown that acetylation of FXR inhibits DNA binding of FXR/RXRα heterodimer and that FXR acetylation levels are highly elevated in obese mice (20). The present studies suggest that potential FXR genomic targets and biological pathways are altered in fatty liver of dietary obese mice, which raises the intriguing possibility that aberrantly elevated acetylation of FXR might be associated with altered transcriptional regulation in obesity in such a way to contribute to fatty liver and subsequently detrimental metabolic outcomes. Further, reduced DNA binding of FXR/RXRα due to FXR hyperacetylation may contribute to the decreased FXR binding sites observed in obesity, 5,272 compared to 15,263 sites in normal mice.

An important and unexpected finding in these studies is that binding of agonist-activated FXR was often associated with repression of gene expression. In a large fraction (8/16) of genes examined, binding of ligand-activated FXR was associated with decreased mRNA levels, which was confirmed by decreased RNAPII occupancy and reduced acetylated histone H3K9/K14 levels. More importantly, levels of known histone gene repression marks, H3K9 methylation and H3K27 methylation, were markedly increased at those genes that were repressed in normal mice after exposure to the FXR agonist GW4064 for a short 1 h or 3 h treatment. Since mRNA levels were measured after 1 h treatment, in addition to overnight treatment with GW4064, direct effects of FXR on gene transcription were likely detected. Although our follow-up epigenetic and gene expression studies have suggested that gene repression by FXR is common, direct comparison of FXR binding with a comprehensive global transcriptome analysis using RNA sequencing or microarray will be necessary to definitively determine the extent of gene repression relative to gene activation by agonist-activated FXR.

FXR is well known to repress its target genes indirectly through the induction of SHP (11-14). These present studies suggest that FXR may also directly repress its target genes by unknown mechanisms. FXR could directly repress by binding to the DNA as a FXR/RXRα heterodimer or as a monomer or homodimer as previously shown in the regulation of ApoA1 (29), which results in inhibition of DNA binding of key transcription factors. In addition, FXR could directly inhibit genes by tethering to DNA-binding transcription factors and masking their interaction with coactivators and/or facilitating the interaction with corepressors. Sumoylation of PPARγ and LXR has been shown to be directly involved in repression of inflammatory genes by tethering of these nuclear receptors to DNA binding activators, such as, NF-κB or AP-1(30). We have evidence that FXR is sumoylated in mouse liver extracts (DH Kim and JK Kemper, unpublished data) and FXR was shown to inhibit inflammatory responses (9, 10), so that this is a possible mechanism for FXR gene repression. Whether FXR directly suppresses its target genes by binding to the DNA or tethering to other transcription factors is an important area of future investigation.

In conclusion, these studies analyze, for the first time, a genome-wide comparison of FXR binding sites in the livers of normal and dietary obese mice. Our studies identify numerous previously unknown potential FXR target genes that are involved in a wide-range of hepatic functions, which suggests that FXR may have much broader functions than previously appreciated. About half of potential target genes in both normal and obese mice were unique to each, suggesting that potential FXR target genes and biological pathways are altered in obesity. Moreover, a large fraction of the potential FXR target genes examined were repressed by ligand-activated FXR, suggesting that direct gene repression by FXR might be more common than previously thought. Additional studies will be required to elucidate the molecular mechanisms by which FXR directly represses these potential genomic targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Grace L. Guo (University of Kansas Medical Center) for helpful suggestions for the ChIP-seq analysis. We thank Ms. Ting Fu for kindly performing oil red staining of liver sections. We also thank Byron Kemper for critical comments on the manuscript.

Financial Support

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DK062777 and a Basic Science Award from the American Diabetes Association to J.K.K.

List of Abbreviations

- FXR

Farnesoid X Receptor

- SHP

Small Heterodimer Partner

- RXR

Retinoid X Receptor

- FXRE

FXR response element

- IR1

Inverted repeat 1

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- ChIP-seq

ChIP-sequencing

- FDR

false discovery rate

- GO

gene ontology

- DAVID

NIH Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery

- MEME

Multiple Em for Motif Elicitation

- TSS

transcription start site

- RNAPII

RNA polymerase II

- SEM

standard error of the mean

References

- 1.Mangelsdorf DJ, Evans RM. The RXR heterodimers and orphan receptors. Cell. 1995;83:841–850. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee FY, Lee H, Hubbert ML, Edwards PA, Zhang Y. FXR, a multipurpose nuclear receptor. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006;31:572–580. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lefebvre P, Cariou B, Lien F, Kuipers F, Staels B. Role of bile acids and bile acid receptors in metabolic regulation. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:147–191. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trauner M, Boyer JL. Bile salt transporters: molecular characterization, function, and regulation. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:633–671. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang W, Ma K, Zhang J, Qatanani M, Cuvillier J, Liu J, et al. Nuclear receptor-dependent bile acid signaling is required for normal liver regeneration. Science. 2006;312:233–236. doi: 10.1126/science.1121435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang F, Huang X, Yi T, Yen Y, Moore DD, Huang W. Spontaneous development of liver tumors in the absence of the bile acid receptor farnesoid X receptor. Cancer Res. 2007;67:863–867. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Lee FY, Barrera G, Lee H, Vales C, Gonzalez FJ, et al. Activation of the nuclear receptor FXR improves hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia in diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1006–1011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506982103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Modica S, Murzilli S, Salvatore L, Schmidt DR, Moschetta A. Nuclear bile acid receptor FXR protects against intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9589–9594. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vavassori P, Mencarelli A, Renga B, Distrutti E, Fiorucci S. The bile acid receptor FXR is a modulator of intestinal innate immunity. J Immunol. 2009;183:6251–6261. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang YD, Chen WD, Wang M, Yu D, Forman BM, Huang W. Farnesoid X receptor antagonizes nuclear factor kappaB in hepatic inflammatory response. Hepatology. 2008;48:1632–1643. doi: 10.1002/hep.22519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe M, Houten SM, Wang L, Moschetta A, Mangelsdorf DJ, Heyman RA, et al. Bile acids lower triglyceride levels via a pathway involving FXR, SHP, and SREBP-1c. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;113:1408–1418. doi: 10.1172/JCI21025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodwin B, Jones SA, Price RR, Watson MA, McKee DD, Moore LB, et al. A regulatory cascade of the nuclear receptors FXR, SHP-1, and LRH-1 represses bile acid biosynthesis. Molecular Cell. 2000;6:517–526. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00051-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang L, Lee Y, Bundman D, Han Y, Thevananther S, Kim C, et al. Redundant pathways for negative feedback regulation of bile acid production. Developmental Cell. 2002;2:721–731. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee J, Padhye A, Sharma A, Song G, Miao J, Mo YY, et al. A pathway involving farnesoid X receptor and small heterodimer partner positively regulates hepatic sirtuin 1 levels via microRNA-34a inhibition. J Biol Chem. 285:12604–12611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.094524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anakk S, Watanabe M, Ochsner SA, McKenna NJ, Finegold MJ, Moore DD. Combined deletion of Fxr and Shp in mice induces Cyp17a1 and results in juvenile onset cholestasis. J Clin Invest. 121:86–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI42846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiang JY. Bile acids: regulation of synthesis. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:1955–1966. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R900010-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inagaki T, Choi M, Moschetta A, Peng L, Cummins CL, McDonald JG, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 15 functions as an enterohepatic signal to regulate bile acid homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2005;2:217–225. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas C, Pellicciari R, Pruzanski M, Auwerx J, Schoonjans K. Targeting bile-acid signalling for metabolic diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:678–693. doi: 10.1038/nrd2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kemper JK. Regulation of FXR transcriptional activity in health and disease: Emerging roles of FXR cofactors and post-translational modifications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:842–850. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kemper JK, Xiao Z, Ponugoti B, Miao J, Fang S, Kanamaluru D, Tsang S, Wu S, Chiang CM, Veenstra TD. FXR acetylation is normally dynamically regulated by p300 and SIRT1 but constitutively elevated in metabolic disease states. Cell Metabolism. 2009;10:392–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fang S, Tsang S, Jones R, Ponugoti B, Yoon H, Wu SY, et al. The p300 acetylase is critical for ligand-activated farnesoid X receptor (FXR) induction of SHP. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35086–35095. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803531200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miao J, Xiao Z, Kanamaluru D, Min G, Yau PM, Veenstra TD, et al. Bile acid signaling pathways increase stability of Small Heterodimer Partner (SHP) by inhibiting ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation. Genes Dev. 2009;23:986–996. doi: 10.1101/gad.1773909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanamaluru DXZ, Fang S, Choi S, Kim D, Veenstra TD, Kemper JK. Arginine methylation by PRMT5 at a naturally-occurring mutation site is critical for liver metabolic regulation by Small Heterodimer Partner. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2011;31:1540–1550. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01212-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang S, Miao J, Xiang L, Ponugoti B, Treuter E, Kemper JK. Coordinated recruitment of histone methyltransferase G9a and other chromatin-modifying enzymes in SHP-mediated regulation of hepatic bile acid metabolism. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1407–1424. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00944-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomas AM, Hart SN, Kong B, Fang J, Zhong XB, Guo GL. Genome-wide tissue-specific farnesoid X receptor binding in mouse liver and intestine. Hepatology. 51:1410–1419. doi: 10.1002/hep.23450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chong HK, Infante AM, Seo YK, Jeon TI, Zhang Y, Edwards PA, et al. Genome-wide interrogation of hepatic FXR reveals an asymmetric IR-1 motif and synergy with LRH-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:6007–6017. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee FY, de Aguiar Vallim TQ, Chong HK, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Jones SA, et al. Activation of the farnesoid X receptor provides protection against acetaminophen-induced hepatic toxicity. Mol Endocrinol. 24:1626–1636. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Claudel T, Sturm E, Duez H, Torra IP, Sirvent A, Kosykh V, et al. Bile acid-activated nuclear receptor FXR suppresses apolipoprotein A-I transcription via a negative FXR response element. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:961–971. doi: 10.1172/JCI14505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghisletti S, Huang W, Ogawa S, Pascual G, Lin ME, Willson TM, et al. Parallel SUMOylation-dependent pathways mediate gene- and signal-specific transrepression by LXRs and PPARgamma. Mol Cell. 2007;25:57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.