Abstract

HOIL-1L and its binding partner HOIP are essential components of the E3-ligase complex that generates linear ubiquitin (Ub) chains, which are critical regulators of NF-κB activation. Using crystallographic and mutational approaches, we characterize the unexpected structural basis for the specific interaction between the Ub-like domain (UBL) of HOIL-1L and the Ub-associated domain (UBA) of HOIP. Our data indicate the functional significance of this non-canonical mode of UBA–UBL interaction in E3 complex formation and subsequent NF-κB activation. This study highlights the versatility and specificity of protein–protein interactions involving Ub/UBLs and their cognate proteins.

Keywords: HOIL-1L, HOIP, linear-ubiquitin-chain assembly complex, NF-κB activation, UBA–UBL interaction

Introduction

The ubiquitin (Ub) system regulates various biological processes including cell-cycle progression, DNA repair, inflammatory response and cell survival. Recently, the stimulus-dependent conjugation of linear Ub chain to the nuclear factor (NF)-κB essential modulator protein has been shown to have crucial roles in NF-κB activation [1–3];. Conjugation and elongation of this linear Ub chain are catalysed by a 600-kDa E3 complex called linear-Ub-chain assembly complex (LUBAC). LUBAC comprises SHARPIN, HOIL-1L and HOIL-1L interacting protein (HOIP). The interaction between HOIL-1L and HOIP is essential for LUBAC formation [3–5]. Binding between HOIL-1L and HOIP is mediated through a specific interaction between the N-terminal Ub-like domain (UBL) of HOIL-1L and Ub-associated domain (UBA) located in the central region of HOIP [1, 6]. The structural evidence reported so far indicates that Ub/UBL–UBA interactions generally involve a well-conserved hydrophobic surface in Ub and UBLs that are characterized by a central isoleucine residue (I44 in Ub) [7, 8]. However, the amino-acid residues that constitute the hydrophobic surface are not conserved in HOIL-1L–UBL (supplementary Fig S1A online) and HOIP–UBA does not crossreact with Ub [6]. To address the structural basis for LUBAC formation, we herein present the three-dimensional (3D) structure data of the atypical UBL–UBA interaction between HOIL-1L and HOIP.

Results And Discussion

Overall structure of the complex

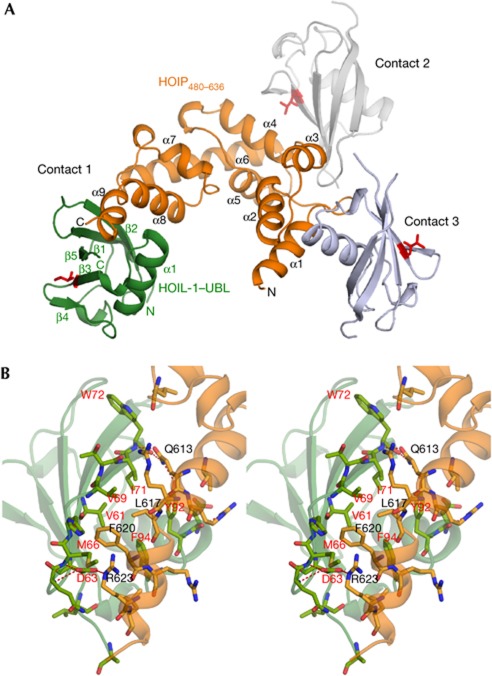

The crystal structure of the complex formed between UBL of HOIL-1L and a UBA-containing HOIP fragment (HOIP480–636) was determined by the multiple wavelength anomalous dispersion method and then refined to 2.7 Å resolution (Fig 1A). As predicted from its primary structure and NMR chemical shift data [9], HOIL-1L–UBL adopts a typical Ub fold that comprises one α-helix (α1), two 310 helices and a five-stranded β-sheet (β1, β2, β3, β4 and β5) with a structure similar to Ub and other UBLs (supplementary Fig S1B,C online). On the other hand, HOIP480–636 adopts a cluster of nine α-helices (α1–α9) and two 310 helices, including a three α-helix bundle of UBA (composed of α6, α7 and α8), which is highly homologous to the typical UBAs (supplementary Fig S2B online). In this crystal structure, three different packing interactions are observed between HOIP480–636 and three HOIL-1L–UBL molecules, each from different unit cells. These interaction modes are herein designated in the order of buried accessible surface areas as contact 1 (833.6 Å2), contact 2 (725.8 Å2) and contact 3 (606.0 Å2), which primarily involve the C-terminal (α6, α8 and α9), central (α4, α5 and α6) and N-terminal (α1, α2 and α3) α-helical regions, respectively (Fig 1B; supplementary Fig S3 online). Among these three types of binding modes, only contact 2 involves the UBL surface that corresponds to the I44 hydrophobic surface conserved among Ub and other UBLs (supplementary Fig S3A online).

Figure 1.

Structure of HOIP480–636 and HOIL-1L–UBL complex. (A) Overall view of the complex. HOIP480–636 is orange, whereas HOIL-1L–UBL is green (at contact 1), grey (at contact 2) and pale blue (at contact 3). V102 in HOIL-1L–UBL (structurally equivalent to I44 in Ub) is shown in red. (B) Close-up stereo view of contact 1 interface between HOIP480–636 (orange) and HOIL-1L–UBL (green) showing intermolecular contacts. Hydrogen bonds and polar interactions are represented by dotted lines. HOIP, HOIL-1L interacting protein; UBL, Ub-like domain; Ub, ubiquitin.

Interaction in solution

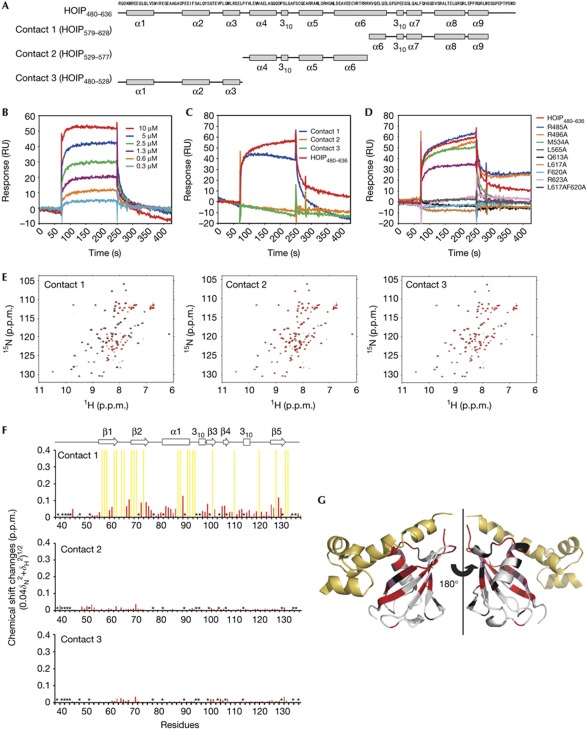

To evaluate whether these modes of interactions are realized in solution, we performed ultracentrifugation, SPR and NMR analyses. Sedimentation coefficient distributions estimated from sedimentation velocity (SV) experiments indicated a 1:1 stoichiometry for the interactions between HOIL-1L–UBL and HOIP480–636 (supplementary Fig S4 online), suggesting that only one of the three types of intermolecular contacts exists in solution. To identify the interaction in solution, HOIP segments corresponding to 579–628 (contact 1 fragment), 529–577 (contact 2 fragment) and 480–528 (contact 3 fragment) were prepared for interaction analyses (Fig 2A). SPR analysis showed that contact 1 fragment retains an affinity for HOIL-1L–UBL, while the remaining two are non-binders despite the fact that these three fragments have nearly identical lengths with similar α-helical contents (Fig 2C; supplementary Fig S5 online). In addition, the single or double amino-acid substitutions at the contact 1 interface (that is, Q613A, L617A, F620A, R623A and L617AF620A) in the HOIP–UBA derivative abolished their binding to HOIL-1L–UBL, while those at the contact 2 (that is, M534A and L565A) and contact 3 (that is, R485A and R496A) interfaces had little impact on the interaction (Fig 2D; supplementary Fig S6 online). Furthermore, we conducted NMR analyses by using 15N-labelled HOIL-1L–UBL and the HOIP segments to characterize their interaction in solution. 1H–15N HSQC data indicated that only contact 1 fragment induced an important spectral perturbation of HOIL-1L–UBL that is consistent with the interaction observed in the crystal structure (Fig 2E–G). Based on these data, we conclude that HOIL-1L–UBL and HOIP480–636 form a 1:1 complex in solution through contact 1 mode of interaction.

Figure 2.

SPR and NMR analyses of interactions of HOIL-1L–UBL with the HOIP–UBA derivative. (A) Constructs of HOIP480–636 segments corresponding to contact 1 (579–628), contact 2 (529–577) and contact 3(480–528) segments. (B–D) SPR analysis of the interactions. (B) HOIP480–636 was injected into a HOIL-1L–UBL-immobilized biosensor chip at six different concentrations. The calculated KD value for binding is 5.2±0.7 × 10−7 (M) by steady-state affinity analyses. (C) HOIP480–636 and its fragments that correspond to contacts 1, 2 and 3 were tested for binding over a HOIL-1L–UBL-immobilized surface. All proteins were tested at a concentration of 100 μg/ml (HOIP480–636, 5.6 μM; contact 1 segment, 15 μM; contact 2 segment, 18 μM; contact 3 segment, 18 μM). (D) HOIP480–636 and its point mutants were tested for binding over a HOIL-1L–UBL-immobilized surface. All proteins were tested at a concentration of 5.6 μM. (E–G) NMR analyses of the interactions. 15N-labelled HOIL-1L–UBL was titrated with contact 1, contact 2 and contact 3 fragments. (E) 1H–15N HSQC spectra measured in the absence (black) and presence (red) of a twofold molar excess of HOIP fragments. (F) NMR chemical shift perturbation data for HOIL-1L–UBL on binding to HOIP fragments. The data are displayed for each HOIL-1L–UBL residue according to the equation (0.04δN2+δH2)1/2, where δN and δH represent the change in nitrogen and proton chemical shifts on mixing with HOIP fragments. HOIL-1L–UBL secondary structures are shown above the plots. Yellow bars indicate residues whose NMR peaks were undetectable due to extreme broadening on addition of contact 1 fragment. Asterisks indicate proline residues, three unassigned residues and residues whose chemical shift perturbation data could not be obtained due to severe peak overlapping. (G) Mapping of the HOIL-1L–UBL residues perturbed following binding to contact 1 fragment. The residues exhibiting chemical shift perturbation (0.08 p.p.m. less than chemical shift changes) and extreme peak broadening are shown in pink and red, respectively. The residues not used as spectroscopic probes are shown in black. HOIP segments corresponding to contact 1 interface are yellow. HOIP, HOIL-1L interacting protein; UBA, Ub-associated domain; UBL, Ub-like domain; Ub, ubiquitin.

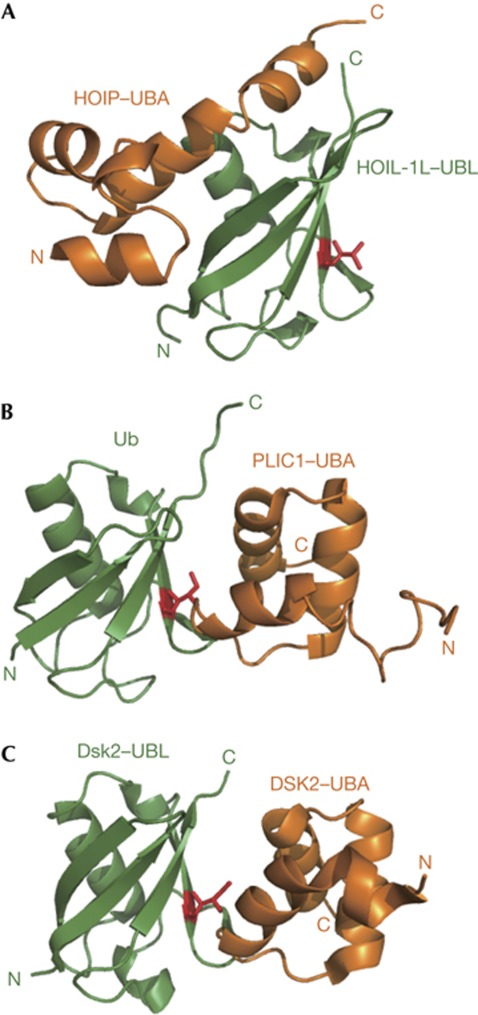

Until now, several structures have been reported for the complexes formed between Ub/UBLs and UBAs. In each complex, the binding interface consists of the well-conserved hydrophobic patch of Ub/UBL and the first and third α-helices of UBA, despite considerable variation of the interaction modes among the complexes (Fig 3B,C) [7, 10, 11]. Interestingly, the interaction mediating HOIL-1L–UBL and the UBA derivative is markedly different from such canonical UBL–UBA interactions: The interaction involves the opposite surface (composed of α1, β1, β2 and β5) of HOIL-1L–UBL and the additional α-helix (α9) of the the UBA derivative. The amino-acid residues located at this binding interface are little conserved in their counterparts (supplementary Figs S1 and S2 online). In particular, HOIL-1L–UBL possesses an inserted loop between β1 and β2, which could contribute to the specificity of this UBL to HOIP–UBA. The segments corresponding to the α9 helix of the HOIP derivative are dispensable in other UBA–Ub/UBL interaction systems [12, 13].

Figure 3.

Comparison of interaction modes between Ub/UBL and UBAs. Ub and UBLs (orange) are shown in the same orientation. (A) Ribbon representation of HOIL-1L–UBL complexed with UBA of HOIP (in this study, green). (B) Ribbon representation of Ub complexed with the UBA of protein-linking IAP with cytoskeleton 1 (PLIC1; PDB code: 2JY6, green)[11]. (C) Ribbon representation of Dsk2–UBL complexed with Dsk2–UBA (PDB code: 2BWE, green)[10]. I44 in Ub or its counterparts in the UBLs are shown in red. HOIP, HOIL-1L interacting protein; PDB, Protein Data Bank; UBA, ubiquitin-associated domain; UBL, ubiquitin-like domain; Ub, ubiquitin.

NF-κB activation through the interaction

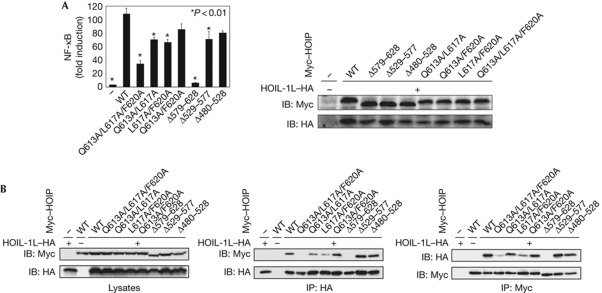

To address the functional relevance of this interaction, we performed NF-κB luciferase reporter assays by introducing HOIL-1L and a series of HOIP mutants into 293T cells because binding between HOIL-1L and HOIP is a prerequisite for NF-κB activation (Fig 4A). NF-κB activation was considerably compromised by the double or triple amino-acid substitutions at contact 1 interface, that is, Q613A/L617A, L617/F620 and Q613A/L617A/F620F, in HOIP. Furthermore, HOIP with deletion of contact 1 segment (Δ579–628) lacked the ability to activate NF-κB, whereas the deletion of contact 2 (Δ529–577) or contact 3 (Δ480–528) segment did not conspicuously affect HOIP activity. It has been confirmed that these inactive HOIP mutants failed to interact with HOIL-1L in the 293T cells (Fig 4B).

Figure 4.

Mutations affecting HOIP–UBA and HOIL-1L–UBL interaction that compromise NF-κB activation. (A) NF-κB activation by HOIP–UBA and HOIL-1L–UBL interaction. Expression of HOIL-1L and HOIP mutants (right panel) and luciferase activity of 293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids and the 5 × NF-κB reporter (left panel) were assessed. Values of luciferase activity are mean±s.e.m., n=3. Statistical analyses were performed using a two-tailed unpaired Student's test, *P<0.01. (B) HOIP–UBA and HOIL-1L–UBL formed complex through contact 1-mode of interaction. Lysates and immunoprecipitates with anti-HA and anti-Myc antibodies from cells that expressed the indicated plasmids were probed as indicated. HA, haemagglutinin; HOIP, HOIL-1L interacting protein; IB, immunoblot; IP, immunoprecipitation; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; UBA, ubiquitin-associated domain; UBL, ubiquitin-like domain; WT, wild type.

Our data indicated that the LUBAC formation involved in NF-κB activation depends on the non-canonical UBA–UBL interaction between HOIL-1L and HOIP. In the NF-κB activation pathway, the K48- and K63-linked Ub chains as well as the linear Ub chain should function as distinct signals by interacting with their specific interacting proteins [1]. Under such circumstances, discrimination among homologous Ub/UBLs and their conjugates would be crucially important. So far, Ub/UBL recognition has been primarily characterized as protein–protein interaction events through their conserved hydrophobic surface (Fig 3) [7, 10, 11]. Our findings exemplify the functional importance of the non-canonical modes of interactions between Ub/UBLs and their binding partners, emphasizing the specificities and potential versatilities of protein–protein interactions involving this class of proteins.

Methods

Protein expression and purification. The DNA fragment encoding residues 37–128, corresponding to HOIL-1L–UBL, was cloned into the pET-28a plasmid (N-terminal hexahistidine tag). The HOIL-1L–UBL was expressed in the Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) codonplus strain following inducing with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside. For NMR analyses, the protein was expressed in M9 minimal medium containing [15N]NH4Cl and/or [13C]glucose. The protein was purified using a Ni2+-NTA high-performance column (GE Healthcare), treated with factor Xa (Novagen) to cleave the hexahistidine tag, and applied to an anion exchange column (Mono-Q; GE Healthcare). The DNA fragment encoding residues 460–636, including the UBA of human HOIP, was cloned into the pGEX6p-1 plasmid and expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) as a glutathione S-transferase (GST)-fused protein. The expressed protein HOIP480–636 was purified using a glutathione-Sepharose 4B column (GE Healthcare), treated with PreScission protease (GE Healthcare) to cleave the GST tag, and then applied to a gel filtration column (Superdex 75; GE Healthcare). Amino-acid substitutions and deletion mutants of HOIP480–636 were made using standard PCR and genetic engineering techniques. The fragments corresponding to residues 579–628 (contact 1), 529–577 (contact 2) and 480–528 (contact 3) were prepared using the same protocol used for HOIP480–636. Selenomethionine (SeMet)-labelled proteins for phase determination were also expressed in E. coli B834(DE3) using M9 minimal medium with SeMet and then purified as described above.

Crystallization and data collection. The HOIL-1L–UBL and HOIP480–636 were mixed at a molar ratio of 1.2:1 and applied to a gel filtration column (Superdex 75) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer, pH 8.0, containing 300 mM NaCl. Fractions containing the protein complex were concentrated to a final concentration of 10 mg/ml and used for crystallization. The native complex crystals were grown under the conditions of 0.1 M HEPES (pH 7.5), 0.1 M KCl and 15% (w/v) PEG6000 at 20°C. The SeMet derivatives were obtained under the same conditions. The crystals were equilibrated in a cryoprotectant buffer containing a reservoir buffer plus 25% (v/v) glycerol and flash frozen in a liquid nitrogen bath. Diffraction data sets were collected at 100 K on beamline BL44XU (SPring-8). Data processing and reduction were performed using the HKL2000 package [14]. Data collection statistics are given in supplementary Table S1 online. The crystals belong to the space group P3121 with cell dimensions of a=b=65.0 Å and c=161.3 Å. The molecular weight of the heterodimer was calculated as 29,371 Da. On the assumption that there is one complex in the asymmetric unit, the ratio of volume to unit protein mass (Vm) was calculated as 3.35 Å3/Da for a complex protein in the asymmetric unit, corresponding to a solvent content of 63.3%.

Structure determination and refinement. The crystal structure of the complex was solved by the multiwavelength anomalous dispersion method using a SeMet derivative. The positions of the heavy atoms were searched using the program SHELXD [15] and refined using the program SHARP [16]. The figure of merit showed 0.41 acentric and 0.30 centric reflections. Density modification with solvent fattening was performed using the program SOLOMON [17]. An initial model was built using the program COOT [18], then refined against a higher-resolution data set for a native crystal structure. After several rounds of iterative manual rebuilding, the native complex structure was refined at 2.7 Å to an Rwork of 21.8% and an Rfree of 25.3% using the program REFMAC5 [19]. In the final model, there were no residues in disallowed regions of the Ramachandran plot [20]. The final refinement statistics are summarized in supplementary Table S1 online.

Analytical ultracentrifugation. A SV experiment was performed in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl using a Proteomelab XL-I Analytical Ultracentrifuge (Beckman–Coulter). The samples of HOIP480–636 (10 μM), HOIL-1L–UBL (10 μM) and their mixtures at varying protein concentrations were measured. Runs were carried out at 60,000 r.p.m. and a temperature of 20°C using 12-mm aluminium double sector centrepieces and a four-hole An60 Ti analytical rotor that was equilibrated to 20°C. The evolution of the resulting concentration gradient was monitored using absorbance detection optics at 231 nm for HOIP480–636 or HOIL-1L–UBL and at 275 nm for their mixture. The radial increment was 0.003 cm and at least 150 scans were obtained between 5.9 and 7.25 cm from the centre of the rotation axis. All SV raw data were analysed using the continuous C(s) distribution model provided by the software program SEDFIT11.71 [21].

NMR analyses. Proteins were dissolved in 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.8) containing 50 mM NaCl and 10% (v/v) D2O. All NMR spectra were acquired at 30°C using DMX500 (Bruker BioSpin), ECA-600 (JEOL), and ECA-920 (JEOL) spectrometers. The HOIL-1L–UBL chemical shifts were assigned to spectra acquired using the following experiments: 2D 1H–15N HSQC, 3D HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HNCO, HN(CA)CO, CBCA(CO)NH and HNCACB. To observe chemical shift perturbations, twofold molar equivalents of HOIP fragments that correspond to HOIP segments 579–628 (contact 1), 529–577 (contact 2) and 480–528 (contact 3) were individually added to [15N]HOIL-1L–UBL solutions. The chemical shift perturbation data were estimated for each residue using the equation (0.04δN2+δH2)1/2 (p.p.m.), where δN and δH represent the change in nitrogen and proton chemical shifts, respectively. All NMR data were processed using NMRPipe software [22], and analysed with SPARKY [23] and CCPNMR [24] software.

Surface plasmon resonance measurements. Interactions of HOIL-1L–UBL with HOIP480–636 and their mutants were analysed via SPR using the Biacore 2000 biosensor system (GE Healthcare). The hexa-His-tagged HOIL-1L–UBL was immobilized on Ni-NTA biosensor chips at a flow rate of 5 μl/min using 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl and 0.05% (v/v) surfactant P20 at 25°C. Assays of HOIP480–636 at six concentrations (ranging from 6.25 to 200 mg/ml) in a mobile phase were performed at a flow rate of 30 μl/min using the 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl and 0.05% (v/v) surfactant P20 at 25°C. The dissociation constant (KD) was calculated via steady-state affinity analysis using Biacore 2000 evaluation software (GE Healthcare). Assays for GST-tagged HOIP segments (contact 1, contact 2 and contact 3 fragments) were performed at a protein concentration of 100 mg/ml in a mobile phase at a flow rate of 20 μl/min using the 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) containing 150 mM NaCl and 0.05% (v/v) surfactant P20 at 25°C.

Measurements of circular dichroism spectra. HOIL-1L–UBL, HOIP480–636 or their mutated protein was dissolved in 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.6) containing 0.15 M NaCl. Measurements of circular dichroism spectra were performed in a 1-mm quartz cuvette at a room temperature using a spectropolarimeter (J-725, JASCO). After subtraction of the spectrum of the buffer alone, data were represented as mean residue ellipticities. The helix contents of proteins were estimated from the mean residue ellipticity at 222 nm ([θ]222) according to the literature [25].

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting. Cells (293T) were transfected with indicated plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Forty-eight hours after transfection, cells were lysed with a lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). For immunoprecipitation, lysates were incubated with the appropriate antibodies for 1 h on ice, followed by incubation with protein A Sepharose for 45 min at 4°C (GE Healthcare). Samples were separated via SDS–PAGE and then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. After blocking in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 5% skim milk, the membrane was incubated with the appropriate primary antibody, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (GE Healthcare). Immunoblots were quantified using an LAS3000 or LAS4000 Mini-Imaging Analyzer (Fuji Film).

Luciferase assay. HEK293T cells were transfected with the luciferase reporter plasmids pGL4-NF-κB-Luc and pGL4-Renilla-Luc/TK (Promega) with the appropriate plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000. Following transfection for 24 h, cells were lysed and then luciferase activity was measured in a Lumat luminometer (Berthold) using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter or Bright-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega) as previously described [2].

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Senda and K. Hattori for their help in the preparation of recombinant proteins. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) (to K.K. and K. Iwai) and the Targeted Proteins Research Program (to K.K., T.M. and K. Iwai). Diffraction data sets were collected at the Osaka University using beamline BL44XU at SPring-8 equipped with MX225-HE (Rayonix), which is financially supported by Academia Sinica and the National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (Taiwan, ROC).

Author contributions: K.K. contributed to the overall guidance of the project. H.Y., T.H., K.E. and T.M. prepared the complex, grew the crystal and solved the structures. H.Y. performed SPR analyses. M.N. and S.U. performed ultracentrifugation analysis. H.Y., Y.U. and M.Y.-U. contributed to the design and execution of the NMR study. K. Ishimoto, H.F., F.T. and K. Iwai contributed to the design and execution of mutational NF-κB activation assay. K. Iwai and K.K. designed the experiments. H.Y., K. Iwai and K.K. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Accession code. Atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession code 4DBG.

References

- Iwai K, Tokunaga F (2009) Linear polyubiquitination: a new regulator of NF-κB activation. EMBO Rep 10: 706–713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga F et al. (2009) Involvement of linear polyubiquitylation of NEMO in NF-κB activation. Nat Cell Biol 11: 123–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga F, Nakagawa T, Nakahara M, Saeki Y, Taniguchi M, Sakata S, Tanaka K, Nakano H, Iwai K (2011) SHARPIN is a component of the NF-κB-activating linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex. Nature 471: 633–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach B et al. (2011) Linear ubiquitination prevents inflammation and regulates immune signalling. Nature 471: 591–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda F et al. (2011) SHARPIN forms a linear ubiquitin ligase complex regulating NF-κB activity and apoptosis. Nature 471: 637–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirisako T et al. (2006) A ubiquitin ligase complex assembles linear polyubiquitin chains. EMBO J 25: 4877–4887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikic I, Wakatsuki S, Walters KJ (2009) Ubiquitin-binding domains—from structures to functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 659–671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper JW, Schulman BA (2006) Structural complexity in ubiquitin recognition. Cell 124: 1133–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uekusa Y et al. (2011) Backbone and side chain 1H, 13C, and 15N assignments of the ubiquitin-like domain of human HOIL-1L, an essential component of linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex. Biomol NMR Assign [Epub ahead of print] doi: ; DOI: 10.1007/s12104-011-9350-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe ED, Hasan N, Trempe JF, Fonso L, Noble ME, Endicott JA, Johnson LN, Brown NR (2006) Structures of the Dsk2 UBL and UBA domains and their complex. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 62: 177–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Raasi S, Fushman D (2008) Affinity makes the difference: nonselective interaction of the UBA domain of Ubiquilin-1 with monomeric ubiquitin and polyubiquitin chains. J Mol Biol 377: 162–180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson CR, Seeger M, Hartmann-Petersen R, Stone M, Wallace M, Semple C, Gordon C (2001) Proteins containing the UBA domain are able to bind to multi-ubiquitin chains. Nat Cell Biol 3: 939–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolaet BL, Clarke DJ, Wolff M, Watson MH, Henze M, Divita G, Reed SI (2001) UBA domains of DNA damage-inducible proteins interact with ubiquitin. Nat Struct Biol 8: 417–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W (1997) Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol 276: 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider TR, Sheldrick GM (2002) Substructure solution with SHELXD. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 58: 1772–1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonrhein C, Blanc E, Roversi P, Bricogne G (2007) Automated structure solution with autoSHARP. Methods Mol Biol 364: 215–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahams JP, Leslie AG (1996) Methods used in the structure determination of bovine mitochondrial F1 ATPase. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 52: 30–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60: 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ (1997) Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 53: 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM (1993) PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallog 26: 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- Schuck P (2000) Size-distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and Lamm equation modeling. Biophys J 78: 1606–1619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A (1995) NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR 6: 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard T, Kneller D (1993) SPARKY 3. San Francisco: University of California [Google Scholar]

- Vranken WF et al. (2005) The CCPN data model for NMR spectroscopy: development of a software pipeline. Proteins 59: 687–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YH, Yang JT, Martinez HM (1972) Determination of the secondary structures of proteins by circular dichroism and optical rotatory dispersion. Biochemistry 11: 4120–4131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.