Abstract

Odontogenic myxoma (OM) is a rare and locally invasive benign neoplasm (comprising of 3-6% of all odontogenic tumors) found exclusively in the jaws. OM commonly occurs in the second and third decades, and the mandible is involved more commonly than the maxilla. The lesion often grows without symptoms and presents as a painless swelling. The radiographic features are variable, and the diagnosis is therefore not easy. This article presents a rare case of OM occurring in the maxilla of a 37-year-old female patient with a brief review of the pathogenesis, clinical, radiological, histopathological, ultrastructural and immunohistochemical characteristics of OM.

Keywords: Fibromyxoma, odontogenic myxomas, odontogenic tumors

INTRODUCTION

Odontogenic myxomas (OM) are tumors derived from embryonic mesenchymal elements of dental anlage.[1,2] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), OM is classified as a benign tumor of ectomesenchymal origin with or without odontogenic epithelium.[3] It appears to originate from the dental papilla, follicle or periodontal ligament.[4] The evidence for its odontogenic origin arises from its almost exclusive location in the tooth-bearing areas of the jaws, its occasional association with missing or unerupted teeth and the presence of odontogenic epithelium.[5]

OM is a locally invasive benign neoplasm. The invasiveness is attributed to the biological nature of the tumor. The OM exhibits abundant extracellular production of ground substance and thin fibrils by the delicate spindle-shaped cells. These undifferentiated mesenchymal cells are capable of fibroblastic differentiation also.[6–8] Depending upon the pattern of differentiation, the histological nature of the tumor varies. It may have complete myxomatous tissue or varying proportions of myxomatous and fibrous tissue. In the latter case, it can be designated either as odontogenic fibromyxoma, in which the myxomatous element predominates or odontogenic myxofibroma, with predominance of fibrous tissue. Some regard OM as a modified form of fibroma in which the myxoid intercellular substance separates the connective tissue.[9,10]

OM of bone is a rare, benign tumor of unknown etiology. Most commonly, it occurs in the second and third decades. Children and persons over 50 years of age are seldom affected. The mandible is involved more frequently than the maxilla, and most reports show a slight predilection for females.[1] OM are usually painless and displaceme nt of teeth and paraesthesia are uncommon clinical features. It therefore reaches considerable size before being detected, and perforation of the cortices of the involved bone may be seen.[4,6,11–13] Maxillary myxomas often extend into the sinus.[14]

Radiographically, the tumor presents as a unilocular or multilocular radiolucent lesion with well-defined borders with fine, bony trabeculae within its interior structure expressing a ‘honeycombed’, ‘soap bubble’ or ‘tennis racket’ appearance. Unilocular appearance may be seen more commonly in children and in the anterior part of the jaws.[5,7,11] Displacement of teeth is a relatively common finding, root resorption is rarely seen and the tumor is often scalloped between the roots.[3,4,6,12]

In this article, a rare case of OM of the maxilla in a female patient is reported, and the varied histopathological features are discussed.

CASE REPORT

A 37-year-old female was referred to dept. of oral and maxillofacial surgery, Government, Dental College and Hospital, Srinagar for the evaluation of a swelling on the right side of his face.

Clinical examination

The swelling was painless, but the patient noticed intermittent watery nasal discharge from the right nostril. One and a half years later, when the patient reported to our department, she had a bony hard, nontender swelling of approximately 4×3 inches, extending superoinferiorly from the infraorbital ridge to 1 inch above the inferior border of the mandible and anteroposteriorly from the right corner of the mouth to 1.5 cm anterior to the tragus. The borders of the swelling were diffused and the skin overlying the swelling was normal in color [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

(a and b) Showing a bony hard, nontender swelling of approximately 4×3 inches, extending superoinferiorly from the infraorbital ridge to 1 inch above the inferior border of the mandible and anteroposteriorly from the right corner of the mouth to 1.5 cm anterior to the tragus. The skin overlying the swelling was normal in color

Oral examination revealed a nontender, bony hard swelling extending from the maxillary right lateral incisor to the right maxillary tuberosity, thereby obliterating the right buccal vestibule. The associated teeth showed grade-I mobility. However, the adjacent gingiva and oral mucosa appeared normal [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Showing a nontender, bony hard swelling extending from the maxillary right lateral incisor to the right maxillary tuberosity, thereby obliterating the right buccal vestibule. The adjacent gingiva and oral mucosa appeared normal

Imaging examinations

The CT revealed a unilocular radiolucent lesion extending from 14 to 17. Teeth in the affected region showed displacement and root resorption [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Showing a unilocular radiolucent lesion extending from 14 to 17

Histopathological findings

On gross examination, the incisional biopsy specimen appeared as a smooth, glistening, gelatinous, lobulated mass. Its color varied from grayish-white to yellow.

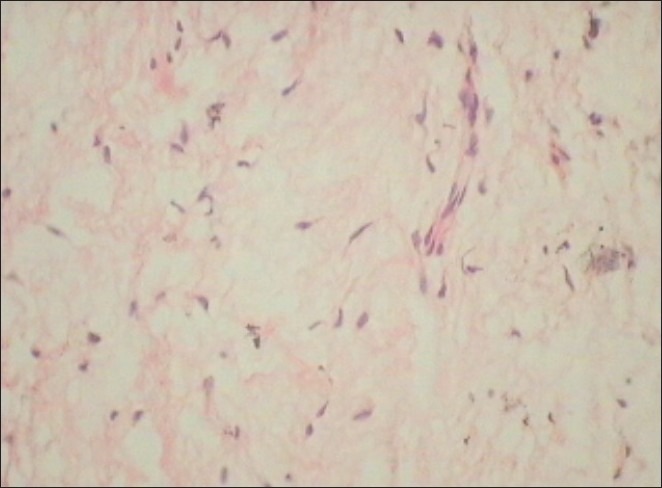

Histopathological examination of the biopsy specimen revealed the typical features of a myxoma, containing loosely arranged stellate or spindle-shaped cells within a myxoid matrix. Few bony spicules with osteoblastic rimming were also seen at the periphery of the lesion. At places, the tumor showed bundles of collagen fibers. Islands or nests of odontogenic epithelium were also seen scattered throughout the tumor mass [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Showing the typical features of a myxoma, containing loosely arranged stellate or spindle-shaped cells within a myxoid matrix

Treatment and prognosis

Under the histopathologic diagnosis of OM, the patient underwent removal of the tumor with a partial en bloc excision of the maxilla. This mode of treatment was selected because of the high recurrence rate of these tumors after conservative treatment. The course has been uneventful for 6 months after surgical removal of the tumor [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Showing the intra-operative view of patient

DISCUSSION

OM is a rare aggressive intraosseous lesion derived from embryonic mesenchymal tissue associated with odontogenesis and primarily consisting of a myxomatous ground substance with widely scattered undifferentiated spindled mesenchymal cells.[15] Although it is a benign neoplasm, it may be infiltrative, aggressive and may recur.[5,16–19]

Odontogenic maxillary myxomas were first mentioned in the literature by Thoma and Goldman in 1947.[10]

Histogenesis

OM (fibromyxoma) is a benign neoplasm of uncertain histogenesis with a characteristic histologic appearance. It often shows infiltration and behaves in a locally aggressive fashion.[14]

There has been a great deal of controversy regarding the origin of myxomatous tumors. Virchow, in 1863, coined the term myxoma for a group of tumors that had histologic resemblance to the mucinous substance of the umbilical chord. In 1948, Stout redefined the histologic criteria for myxomas as true neoplasms that do not metastasize and exclude the presence of recognizable cellular components of other mesenchymal tissues, especially chondroblasts, lipoblasts, and rhabdomyoblasts. Myxoma is a tumor that can be found in heart, skin and subcutaneous tissue and, centrally, in the bone.[20]

Myxomas of the head and neck are rare tumors. Two forms can be identified: (1) facial bone derived, which had been subdivided in the past into true osteogenic myxoma and OM and (2) “soft tissue”-derived myxoma, derived from the perioral soft tissue, parotid gland, ear, and larynx.[21]

Traditionally, the myxoma of the maxilla and mandible has been considered to be a neoplasm of odontogenic origin. Although the evidence is mainly circumstantial, support of an odontogenic origin has been perpetuated by its almost exclusive occurrence in the tooth-bearing areas of the jaws, its common association with an unerupted tooth or a developmentally absent tooth, its frequent occurrence in young individuals, its histologic resemblance to dental mesenchyme, especially the dental papilla, and the occasional presence of sparse amounts of odontogenic epithelium.[4]

In a recent immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study, Moshiri et al. supported the notion of odontogenic origin of myxomas by suggesting that fibroblasts that compose the tooth germ undergo modification to give rise to OM.[22]

Slootweg and Wittkampf on the other hand showed that the matrix of myxomas of the jaw is entirely different from the matrix seen in the dental pulp and periodontal ligament. In addition, they also argued that myxomas may also develop in the sinonasal tract and other facial bones that originate from the nonodontogenic mesenchyme. According to them, even the presence of odontogenic epithelium is not necessary to make the diagnosis of myxoma of bone.[17]

Contrary to the findings of Slootweg and Wittkampf, McClure and Dahlin reviewed more than 600 bone tumors of patients at Mayo Clinic and concluded that there were no true myxomas of the bone except for those found in the mandible and maxilla.[23]

Epidemiology

Frequency

OM almost exclusively occurs in the jaw bones, comprising around 3-6% of all odontogenic tumors.[10]

Age predilection

The tumor occurs across an age group that varies from 22.7 to 36.9 years. It is rarely seen in patients younger than 10 years of age or older than 50.[12] Kaffe et al. reviewed 164 OM of the jaw and found that 75% occurred between the second and fourth decades (patient age range, 1-73 years; mean 30 years).[24] Farman et al. differentiated between maxillary and mandibular OM and suggested that the mean age at the time of diagnosis of maxillary OM in men was 29.2 years and in women was 35.3 years, while the mandibular OM in men occur at a mean age of 25.8 years and in women they occur at 29.3 years.[25]

Our case presented at the age of 37 years, which is in conformity with that reported in the literature.

Sex ratio

Gunhan et al.[26] and Regezi et al.[21] reported a higher incidence of these tumors in women (64-95%) than in men.

Location

The mandible appears to be more frequently affected than the maxilla, especially the posterior region. According to Reichart and Philipsen, mandibular myxomas accounted for 66.4%, with 33.6% in the maxilla. Whereas 65.1% of the mandibular cases were located in the molar and premolar areas, 73.8% cases were seen in the same areas of the maxilla.[10]

In the present case, the lesion was located in the premolar and molar area of the maxilla.

Clinical presentation

Most OM are first noticed as a result of a slowly increasing swelling or asymmetry of the affected jaw. Lesions are generally painless and ulceration of the overlying oral mucosa only occurs when the tumor interferes with dental occlusion. Some patients present with progressive pain in lesions involving maxilla and maxillary sinus, with eventual neurological disturbance.[10]

Growth may be rapid and infiltration of neighboring soft tissue structure may occur. Both the buccal and the lingual cortical plates of the mandible may expand occasionally.[2] OM of the maxilla behaves more aggressively than that of the mandible, as it spreads through the maxillary sinus as presented in our case.[10] Kaffe et al. found expansion of the jaws in 74% of the cases. When the maxillary sinus is involved, the OM often fill the entire antrum. In severe cases, nasal obstruction or exopthalmus may be the leading symptoms.[24] Displacement of teeth has been registered in 9.5% of the cases. Similar features were appreciated in the present case.

Radiological presentation

On conventional radiographs, myxomas of the jaws appear as multilocular (mostly) or unilocular radiolucencies. Unilocular radiolucencies are more frequently found in the anterior region of the jaws, while multilocular lesions occur mainly in the posterior region.[12,16]

Computed tomographic images of OM may show any of the following features:

Osteolytic expansile lesions with mild enhancement of the solid portion of the mass in the myxoma of the mandible.

Bony expansion and thinning of cortical plates with strong enhancement of the mass lesion in the anterior maxilla.

A soft tissue mass with bone destruction and thinning and strands of fine lace-like density representing ossifications in the maxillary sinus.[27]

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a well-defined, well-enhanced lesion with homogeneous signal intensity on every pulse sequence. The lesion showed intermediate signal intensity on the T1-T2-weighted images.[10] Unfortunately, MRI was not performed in this case.

Radiological differentials

OM should be included in the differential diagnosis of both radiolucent and mixed lesions, in both the jaws, for individuals of all age groups. When unilocular and without trabeculae, the tumor closely resembles periapical, lateral, periodontal, and traumatic bone cysts. When multilocular, it must be distinguished from ameloblastoma, central hemangioma and odontogenic keratocyst.[16]

OM with multilocularradiolucencies represent “honey comb,” “soap bubble” or “tennis racquet” appearance, which helps in distinguishing this entity from malignant tumors arising centrally within the jaw bones, because the latter usually cause massive bone destruction without compartments formed by bony trabeculations or bony septa.[28] In the present case, the orthopantamograph revealed a single large expansile radiolucent lesion without any trabeculations in the area of bony destruction. However, few radioopacties were seen within the radiolucency.

Pathology

Gross examination

On gross examination of the specimen shows the gelatinous, loose structure which was obvious in our case also.[13]

Microscopic examination

OM is a benign neoplasm without encapsulation. A spectrum of fibrous connective tissue stroma is present: from myxoid to densely hyalinized and from relatively acellular to cellular.[29,30] Calcification may or may not be present. It is distinguished by the presence of sparse cords and islands of inactive odontogenic epithelium surrounded by a narrow zone of hyalinization.[19,31]

Microscopically, the myxoma is made up of loosely arranged spindle-shaped and stellate cells, many of which have long fibrillar processes that tend to intermesh. The loose tissue is not highly cellular, and these cells do not show evidence of significant activity (pleomorphism, prominent nucleoli, or mitotic figures). The intercellular substance is mucoid. The tumor is usually interspersed with a variable number of tiny capillaries and occasionally strands of collagen. The fibrils have been shown by silver impregnation to be reticulin.[32]

In the case of fibromyxoma, the amount of collagen in the mucoidstroma is more prominent.[10] The variation in the histopathological diagnosis between the initial biopsy as odontogenic fibroma and the final histopathological diagnosis as odontogenic fibromyxoma could be attributed either to the biological spectrum of this lesion or non-inclusion of myxomatous areas in the biopsy.[11,33] The ultra-structural findings indicate that the odontogenic fibroma and the OM share many common morphological features.[4,7]

Histologically, differential diagnosis must be made with rabdomyosarcoma, myxoidliposarcoma, neurogenic sarcoma, neurofibroma, lipoma, fibroma, chondromyxoid, and nodular faciitis.[10]

Histochemical findings

Farman et al. reviewed the histochemical findings in OM. The ground substance of OM has been shown to consist of about 80% hyaluronic acid and 20% chondroitin sulfate. Tumor cells appear to be relatively inactive, with low levels of oxidative enzymes. Tumor cells also show slight alkaline phosphatase activity. The myxoid intercellular matrix stains positively with alcian blue, but PAS staining may be negative.[25]

Immunohistochemical findings

The myxomatous component of OM has been compared with the primitive mesenchyme that is found throughout the body. It has also been compared with the dental papilla and the dental follicle.[10]

OM tumor cells are mesenchymal in origin and express vimentin and muscle-specific actin. Conflicting description of S-100 and GFAP positivity has been reported. The matrix exhibits different proteins, mostly type-I and type IV collagen, fibronectin, and proteoglycans.[12]

Ultrastructural findings

An extensive study on the ultrastructure of OM was published by Goldblat in 1976. Two basic types of tumor cells were described, secretory and nonsecretory. The secretory cell type was considered the principal tumor cell and resembled fibroblasts.[10]

Treatment modalities and prognosis

The tumor is not radiosensitive, and surgery is the treatment of choice. Treatment of OM vary from local excision, curettage, or enucleation to radical resection.[1,11,25]

The aggressive nature of OM is well documented in the literature. While generally considered a slow-growing neoplasm, OM may be infiltrative and aggressive, with high recurrence rates. Because of poor follow-up and lack of reports, a precise analysis of recurrence rates is still missing. Recurrence is considered to be directly related to the type of therapy, with conservative surgery resulting in a higher number of recurrences. In the present case, the tumor was completely removed by en bloc resection and no recurrence was reported even after 6 months of the surgery.[34]

Summary and Conclusion

A rare case of OM of the maxilla in a 37-year-old female patient is presented. It was treated by total surgical excision.

The biologic spectrum of the lesion is reflected by the variation in the final histopathological diagnosis. Also, extensive emphasis should be levied on to determine the origin of these locally aggressive myxomas and thereby put to rest various controversies surrounding these lesions.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abiose BO, Ajagbe HA, Thomas O. Fibromyxomas of the jaws: A study of 10 cases. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;25:415–21. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(87)90093-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu Y, Xuan M, Takata T, Wang C, He Z, Zhou Z, et al. Odontogenictumors: A demographic study of 759 cases in a Chinese population. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86:707–14. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90208-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pindborg JJ, Kramer IR. International Histological classification of tumors, No.5. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1971. Histological typing of Odontogenictumors. Jaw cysts and Allied lesions. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halfpenny W, Verey A, Bardsley V. Myxoma of mandibular condyle: A case report and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90:348–53. doi: 10.1067/moe.2000.107364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stout AP. Myxoma the tumor of primitive mesenchyme. Ann Surg. 1948;127:706–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regizi JA, Scuiba J. Oral pathology clinical - Pathologic correlations. London: WB Saunders Company Ltd; 2003. pp. 278–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muzio L Lo, Nocini P, Favia G, Procaccini M, Mignogna MD. Odontogenicmyxoma of the jaws: A clinical, radiologic, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;82:426–33. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(96)80309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zimmermann DC, Dahlin DC. Myxomatoustumors of the jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1958;11:1069–80. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(58)90289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adekeye EO, Avery BS, Edwards MB, Williams HK. Advanced central myxoma of the jaws in Nigeria: Clinical features, treatment and pathogenesis. Int J Oral Surg. 1984;13:177–86. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(84)80001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reichart PA, Philipsen HP. Odontogenictumors and allied lesions. Illinois: Quintessence Publishing Co Ltd; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deron PB, Nikolovski N, Hollander JC den, Spoelstra HA, Knegt PP. Myxoma of the maxilla: A case with extremely aggressive biologic behavior. Head Neck. 1996;18:459–64. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199609/10)18:5<459::AID-HED10>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gnepp DR. Diagnostic Surgical Pathology of head and neck. London: WB Saunders Company Ltd; 2001. p. 643. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neville BW, Damm DD, Allen CM, Bouquote JE. Oral and maxillo-facial pathology. London: WB Saunders Company Ltd; 2002. pp. 635–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brannon RB. Central odontogenic fibroma, myxoma (odontogenicmyxoma, fibromyxoma), and central odontogenic granular cell tumor. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2004;16:359–74. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim J, Ellis GL. Dental follicular tissue: Misinterpretation as odontogenictumors. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;51:762–8. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(10)80417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chuchurru JA, Luberti R, Cornicelli JC, Dominguez FV. Myxoma of the mandible with unusual radiographic appearance. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;43:987–90. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(85)90018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slootweg PJ, Wittkampf RM. Myxoma of the jaws: An analysis of 15 cases. J Maxillofac Surg. 1986;14:46–52. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(86)80258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Green TL, Leighty SM, Walters R. Immunohistochemicalevalution of oral myxoid lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:469–71. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90327-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao M, Lu Y, Takata T, Ogawa I, Miyauchi M, Mock D, et al. Immunohistochemical and histochemical characterization of the mucosubstances of odontogenicmyxoma: Histogenesis and differential diagnosis. Pathol Res Pract. 1999;195:391–7. doi: 10.1016/S0344-0338(99)80012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landa LE, Hedrick MH, Nepomuceno-Perez MC, Sotereanos GC. Recurrent Myxoma of the Zygoma: A case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60:704–8. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.33126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Regezi JA, Kerr DA, Courtney RM. Odontogenictumors: Analysis of 706 cases. J Oral Surg. 1978;36:771–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moshiri S, Oda D, Worthington P, Myall R. Odontogenic myxoma: Histochemical and ultrastructural study. J Oral Pathol Med. 1992;21:401–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1992.tb01027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McClure DK, Dahlin DC. Myxoma of bone: Report of three cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1977;52:249–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaffe I, Naor H, Buchner A. Clinical and radiological features of odontogenic myxoma of the jaws. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1997;26:299–303. doi: 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farman AG, Nortje CJ, Grotepass FW, Farman FJ, van Zyl JA. Myxofibroma of the jaws. Br J Oral Surg. 1977;15:3–18. doi: 10.1016/0007-117x(77)90002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gunhan O, Erseven G, Ruacan S, Celasun B, Aydintug Y, Ergun E, et al. Odontogenic tumours: A series of 409 cases. Aust Dent J. 1990;35:518–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1990.tb04683.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Asaumi J, Konouchi H, Hisatomi M, Kishi K. Odontogenicmyxoma of maxillary sinus: CT and MR -pathologic correlation. Eur J Radiol. 2001;37:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(00)00229-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawai T, Murakami S, Nishiyama H, Kishino M, Sakuda M, Fuhihata H. Diagnostic imaging for a case of maxillary myxoma with a review of the magnetic resonance images of myxoid lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;84:449–54. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gosh BC, Huvos AG, Gerold FP, Miller TR. Myxoma of the jaw bones. Cancer. 1973;31:237–40. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197301)31:1<237::aid-cncr2820310131>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gormley MB, Mallin RE, Solomon M, Jarrett W, Bromberg B. Odontogenic myxofibroma: Report of two cases. J Oral Surg. 1975;33:356–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oygür T, Dolanmaz D, Tokman B, Bayraktar S. Odontogenicmyxoma containing osteocement-like spheroid bodies: Report of a case with an unusual histopathological feature. J Oral Pathol Med. 2001;30:504–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.030008504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajendran R, Sivapathasundaram B. Shafer's Textbook of Oral Pathology. 5th ed. New Delhi: Elsevier; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hwang EH, Lee SR. Central odontogenic fibroma of the simple type. Korean J Oral Maxillofac Radiol. 2002;32:227–30. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon NM, Merkx MA, Vuhahula E, Ngassapa D, Stoelinga PJ. Odontogenicmyxoma: A clinicopathological study of 33 cases. Int J Oral MaxillofacSurg. 2004;33:333–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]