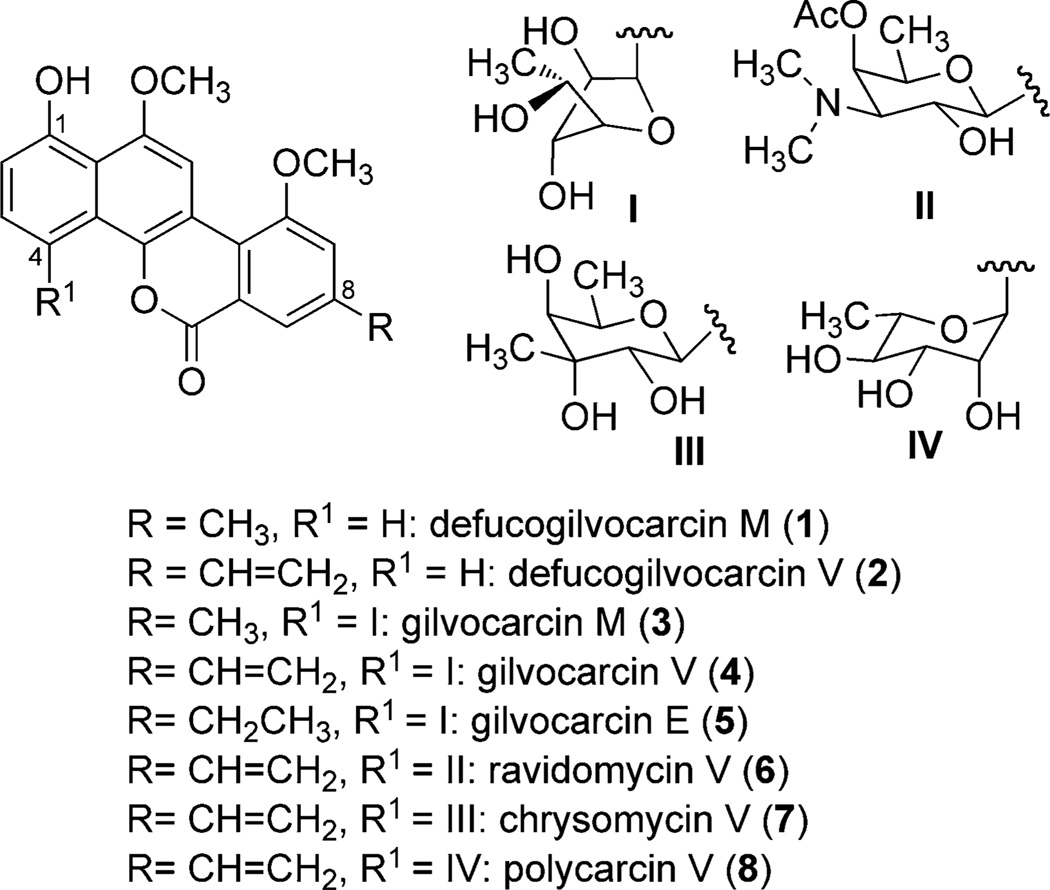

Gilvocarcin V (GV, 4) is the major metabolite of Streptomyces griseoflavus Gö 3592 and various other Streptomyces species. GV is usually produced along with its minor congeners, gilvocarcin M (3) and gilvocarcin E (5), that vary with respect to their side chain at the C8-position.[1] Several analogues of GV (for example, 6–8, Scheme 1), which are collectively called the gilvocarcin group of natural products, have been isolated from different Streptomyces species. All of these analogues contain the characteristic, polyketide-derived benzo[d]naphtho[1,2-b]pyran-6-one chromophore, but different C-glycosidically linked sugar units Scheme 1).[2] Members of this group of natural products are well-known for strong antitumor activities,[3] a unique mode of action,[4] and remarkably low toxicities.[2c, 5] However, the inherent poor solubility of these molecules appears to be a major obstacle in their development as therapeutics. The chemical syntheses that have been developed so far are unsuitable for generating a library of analogues,[6] whereas combinatorial biosynthetic efforts have shown more promise.[7] The continued advancement and successful implementation of such combinatorial biosynthetic and mutasynthetic approaches requires an in-depth knowledge of the biosynthetic pathway. Incorporation studies with isotope-labeled precursors[8] and genetic experiments[1a, 8d, 9] have revealed that the benzo[d]naphtho[1,2-b]pyran-6-one chromophore of the gilvocarcins is produced from a polyketide-derived angucyclinone intermediate through a complex oxidative rearrangement process. However, the details of the exact sequence of biosynthetic events and the enzymes that are involved have remained elusive. In this context, we herein report a complete, one-pot, enzymatic total synthesis of defucogilvocarcin M(1), a model compound that contains the unique chromophore common to all members of the gilvocarcin group of natural products.[10] The reconstitution of this pathway then enabled further investigation into the details of the oxidative rearrangement process of GV biosynthesis by systematic variation of the enzyme mixture used. For this approach we suggest the term “combinatorial biosynthetic enzymology”.

Scheme 1.

Representative members of the gilvocarcin group of natural products.

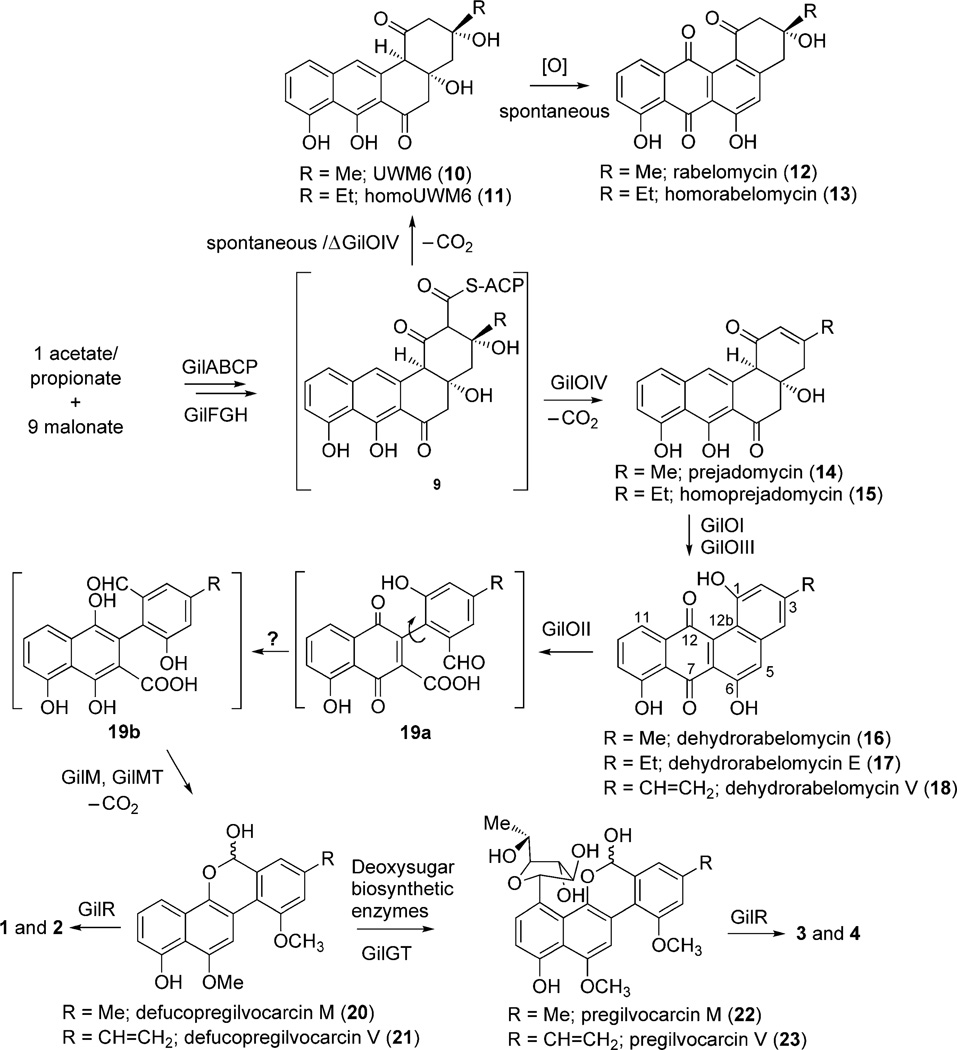

The entire GV biosynthetic gene cluster was cloned and heterologously expressed in Streptomyces lividans TK24 to produce 4.[1a] The function of biosynthetic enzymes was then confirmed by both in vitro and in vivo studies.[7a, 9, 11–13] The cluster encodes a set of typical type II polyketide synthase (PKS) enzymes, which includes a ketosynthase (GilA), a chain-length factor (GilB), an acyl carrier protein (GilC), two malonyl-CoA:acyl carrier protein transacylase (MCAT) homologues (GilP, GilQ), a PKS-associated keto reductase (GilF), and two cyclases (GilK, GilG). Together, this group of enzymes was able to catalyze the formation of the angucy-clinone UWM6 (10).[12] Compound 10 along with many other angucyclines was proposed to be an intermediate in the biosynthesis of 3.[14] Several post-PKS tailoring enzymes, which include four oxygenases (GilOI, GilOII, GilOIII, GilOIV), a oxidoreductase (GilR), a methyltransferase (GilMT), a reductase (GilH), a C-glycosyltransferase (GilGT), deoxysugar biosynthetic enzymes (GilD, GilE, GilU), and a handful of enzymes with unknown functionality (GilM, GilN, GilL, and GilV) were believed to complete the remaining steps. Unfortunately, the reactions of most of the inactivation mutants of these enzymes accumulated biosynthetic shunt products, which leaves ambiguity over the post-PKS biosynthetic steps. For example, the inactivation of GilOI produced prejadomycin (14) and homoprejadomycin (15), and inactivation of GilOII produced dehydrorabelomycin (16), dehydrorabelomycin E (17), and dehydrorabelomycin V (18).[8d, 9] Rabelomycin (12) and homorabelomycin (13) are the major metabolites of the GilOIV-deleted mutant, whereas 5 is the major metabolite of the GilOIII-deleted mutant.[13b] The production of angucyclinones 12–18 by these oxygenase-deficient mutants led to the hypothesis that the three oxygenases, GilOI, GilOII, and GilOIV, might form a multienzyme complex that is responsible for a concerted reaction pathway. This pathway includes the crucial C–C bond cleavage that eventually leads to the formation of the gilvocarcin scaffold.[9] Then, the methylation of the two aromatic hydroxy groups, formation of a hemiacetal ring, decarboxylation, and C-glycosyltransfer are still necessary to generate pregilvocarcins 22 and 23, which are the substrates of GilR.[13a,c] GilR has recently been shown to catalyze the very last step in the biosynthesis of gilvocarcin by converting 22 and 23 into the final lactone-containing products (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2.

Proposed gilvocarcin biosynthetic pathway.

To gain a better understanding of the role of individual gene products of GV biosynthesis, and to identify the actual biosynthetic sequence of events, we focused on in vitro studies with select pathway enzymes. In this context, we recently reported an enzymatic total synthesis of the presumed GV pathway intermediate 10 and its conversion into the shunt product 12 by using a mixture of all of the necessary PKS enzymes.[12] In this study, we expanded the scope of the earlier experiments that involved selected post-PKS enzymes. Whereas the PKS enzymes were expressed and used as reported earlier,[12] the following enzymes were chosen to perform the oxidative rearrangement and the follow-up reaction cascade that is necessary to establish the defucogilvocarcin M scaffold: GilOI, GilOII, GilOIV, GilM, GilMT, and GilR. The putative oxygenases and oxidoreductase GilR were logical choices. GilMT, which was deduced to be O-methyltransferase from its amino acid sequence,[1a] was believed to be involved in the necessary O-methyl-transfer steps. Whereas the gilM gene was originally found to encode a protein of unknown function,[1a] a recent search with the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) revealed a remote resemblance to thiopurine-S-methyltransferases. Thus, GilM was believed to be a second O-methyltransferase. Furthermore, a gene inactivation experiment to pinpoint the role of the product of GilM led to the complete loss of GV production (data not shown), which suggests that GilM is an essential enzyme. All of the chosen post-PKS enzymes could be expressed in E. coli and purified as His6-tagged proteins, except for GilOIV. After several unsuccessful attempts to express GilOIV in soluble form, this enzyme was replaced with its homologue JadF from the jadomycin biosynthetic pathway, as JadF could be overexpressed and purified from E. coli. JadF has previously been shown to complement the GilOIV-minus mutant S. lividans TK24 (cosG9B3-ΔOIV), which proves the functional identity of the two enzymes.[11] Considering that GilOI and GilOIV are oxygenases that contain flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD, Figure S3 in the Supporting Information) and require their cofactor to be recycled, a reductase was needed to generate FADH2. The putative nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate) (NAD(P)H) flavin reductase GilH[7a] showed only very poor activity. Therefore, the E. coli flavin reductase Fre, a readily available homologue of GilH with known functionality, was chosen and purified from an E. coli overexpression construct.[15]

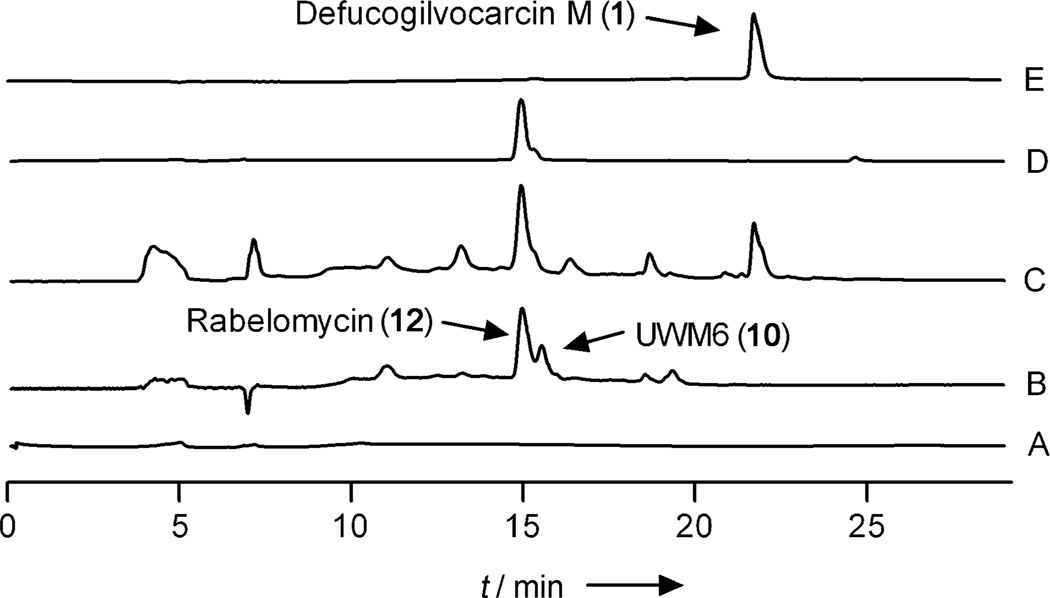

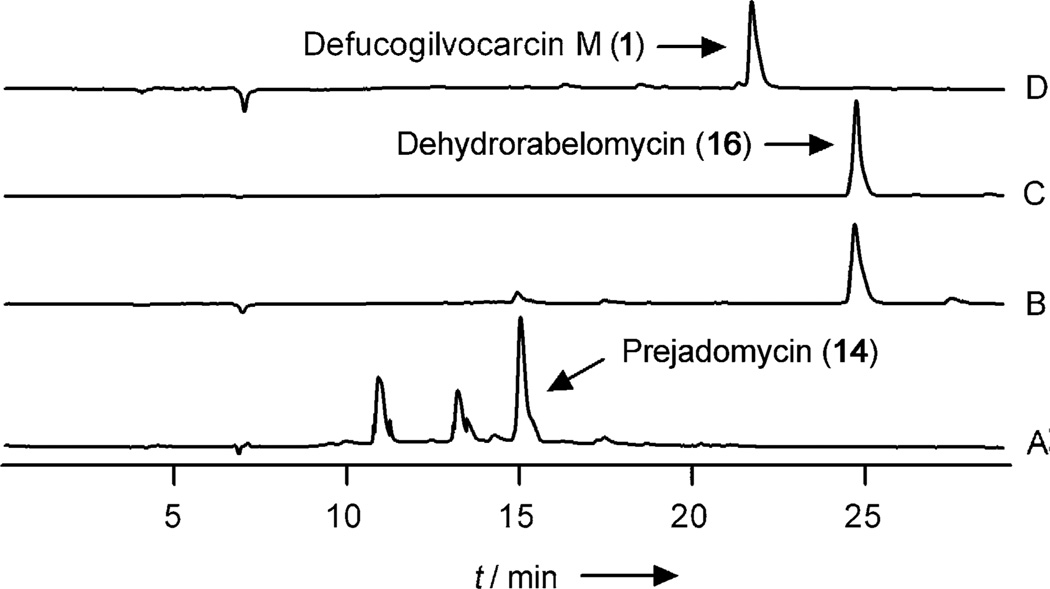

To test the activity of the PKS enzymes, all seven PKS enzymes (GilAB, RavC, GilF, GilP, JadD, RavG)[12, 16a] were incubated with one equivalent of acetyl-CoA and nine equivalents of malonyl-CoA in the presence of the cofactor NADPH. To ensure a supply of NADPH for the reaction, the established system for the regeneration of NADPH that consists of glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH) from E. coli was used. As expected, the colorless reaction mixture changed to yellow, and the formation of the expected products 10 and 12 was confirmed by HPLC analysis (Figure 1, trace B). With fully functional PKS enzymes in hand, a mixture of 15 enzymes was produced that consisted of the PKS enzymes listed above and of all of the anticipated post-PKS enzymes (GilOI, GilOII, JadF, GilM, GilMT, GilR, and Fre, see the Supporting Information for details). This enzyme mixture was incubated with acetyl-CoA, malonyl-CoA, the cofactors NADPH, FAD, and S-adenosyl methionine (SAM), along with the NADPH regeneration system G6P/G6PDH. After extraction with ethyl acetate, HPLC analysis of the product mixture showed the presence of 1, 12, and a small quantity of some hitherto unknown compounds (Figure 1, trace C). The structures of the main products were confirmed by the comparison of their physicochemical characteristics (HPLC retention time and HRMS data) with those of authentic standard compounds. An authentic sample of 1 was isolated from the previously characterized GilGT-minus mutant.[13b] Control reactions without acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA or without the PKS enzymes did not produce any metabolite (Figure 1, trace A).

Figure 1.

HPLC traces of the enzymatic reactions for the synthesis of defucogilvocarcin M (1): A) Control reaction without acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA. B) Acetyl-CoA+malonyl-CoA+PKS enzymes. C) Acetyl-CoA + malonyl-CoA + PKS enzymes + post-PKS enzymes. D) Rabelomycin (12) standard. E) Defucogilvocarcin M (1) standard.

After the enzyme mixture that was capable of producing 1 was established, we focused on permutation experiments by removing one or more of the enzymes to investigate the complex oxidation cascade (see Table S2 in the Supporting Information and the discussion below).

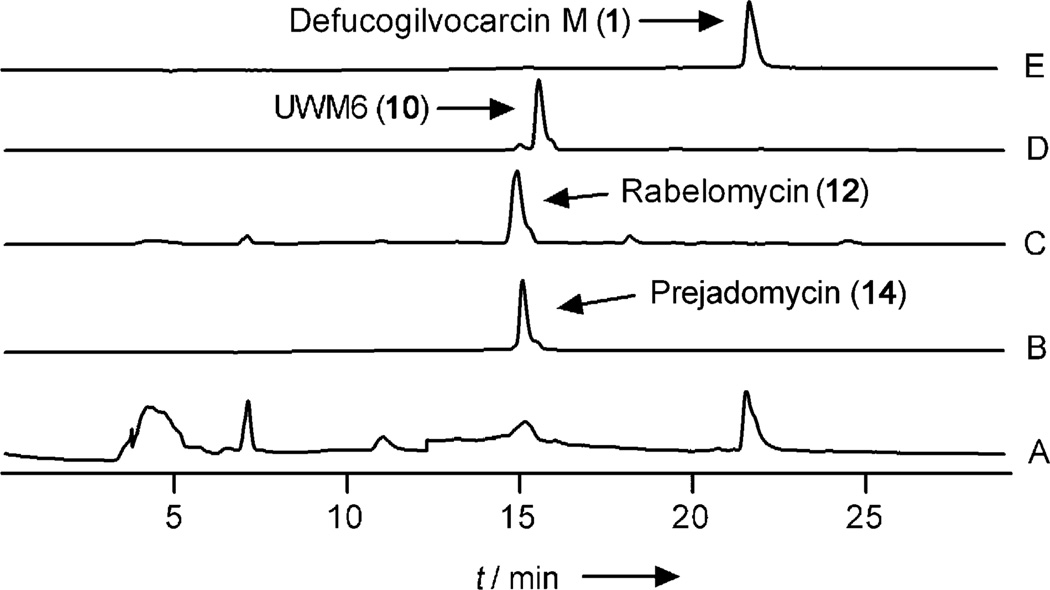

Two of the previously proposed pathway intermediates, 10 and 14, were used as substrates instead of acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA in the multienzyme reaction described above. Whereas 14 was completely converted into 1 in the presence and in the absence of the PKS enzymes (Figure 2, trace A), 10 was not. Instead, 12 was exclusively produced in the reaction with 10 (Figure 2, trace C). This confirmed that 14 is indeed a true intermediate in the biosynthesis of 3, and that the designated PKS enzymes have no role in converting 14 into 1. The fact that the enzyme mixture failed to convert 10 into 1 was intriguing and contradicted our previously proposed hypotheses.[16b,c] This indicated that 10 might not be an intermediate in the GV biosynthesis pathway at all and led to the new hypothesis that one or more of the designated post-PKS enzymes may only act on angucyclinone substrates that are still tethered to the acyl carrier protein (ACP). This would render 10 a shunt product that is formed by spontaneous hydrolysis and decarboxylation of the ACP-tethered intermediate 9. Shunt product 12 is in turn produced from 10 by aerial oxidation and spontaneous dehydration, as previously described[12] (Scheme 2).

Figure 2.

HPLC traces of the enzymatic reactions with prejadomycin (14) and UWM6 (10): A) Prejadomycin (14) + PKS-enzymes + post-PKS enzymes. B) Prejadomycin (14) standard. C) UWM6 (10) + PKS-enzymes + post-PKS enzymes. D) UWM6 (10) standard. E) Defucogilvocarcin M (1) standard.

To further investigate this hypothesis it was necessary to complement the PKS enzymes with one or more of the designated post-PKS enzymes, thereby reducing the post-PKS mix to the point at which a stable intermediate that is not tethered to the ACP emerges from the mixture. A number of such experiments were performed, which resulted in the systematic removal of individual enzymes from the reaction mixture (for details see Table S2 in the Supporting Information). Removing GilOI, GilOII, or JadF from the enzyme mixture resulted in the production of 14, 16, and 12, respectively, whereas the removal of GilM/GilMT led to unidentified products. The addition of individual oxygenases to the PKS enzyme mixture led to the discovery that only JadF (the soluble replacement of GilOIV), was required in the PKS-enzyme mixture to convert acetyl-CoA/malonyl-CoA into 14 (Figure 3, trace A). GilOIV/JadF was previously suggested to be a bifunctional enzyme that acts as an oxygenase and a 2,3-dehydratase.[16b] The mixed enzyme reactions that were performed confirmed that GilOIV/JadF indeed catalyzes the 2,3-dehydration. Moreover, GilOIV/JadF also serves as a key enzyme that bridges between the PKS and post-PKS reactions, possibly by catalyzing the hydrolysis and decarboxylation of the ACP-tethered 9 to directly form 14 (Scheme 2). Thus, this enzyme should be designated a PKS enzyme as it acts on an ACP-tethered substrate.[14b] Because of the lack of suitable reference compounds, the structures of the two minor unknown peaks could not be determined (Figure 3, trace A). These might be intermediates or shunt products of the reaction sequence ACP-hydrolysis→2-decarboxylation→2,3-dehydration. These products may be angucyclinones that are hydrolyzed but still contain a 2-carboxy group.

Figure 3.

HPLC traces of the enzymatic reactions: A) Acetyl CoA + malonyl-CoA + PKS enzymes + JadF produce prejadomycin (14). B) Prejadomycin (14) + GilOI. C) Dehydrorabelomycin (16) standard. D) Dehydrorabelomycin (16) + GilOII + GilM + GilMT + GilR produce defucogilvocarcin M 1.

To determine the fate of 14, follow-up experiments were performed in which one or more of the remaining post-PKS enzymes were interrogated by using 14 as the substrate (for details see Table S3 in the Supporting Information). These studies identified GilOI as the enzyme that is responsible for the oxidation of 14 to 16 (Figure 3, trace B), which suggests that GilOI is a bifunctional enzyme and performs a 4a,12b-dehydration as well as an oxidation at the C12-position. Identical findings and conclusions were reported previously for JadH, the homologous enzyme in the jadomycin biosynthesis pathway.[16, 17] Contrary to our previous findings in in vivo experiments, an enzyme mixture that consists of the enzymes GilOI, GilOII, GilM, GilMT, GilR, and Fre[15] was able to completely convert 16 into 1 (see Table S4 in the Supporting Information). This result confirms that 16 is a true intermediate in the gilvocarcin biosynthesis pathway (Figure 3, trace D). Further combinatorial biosynthetic enzymology revealed that the remaining four enzymes, GilOII, GilM, GilMT, and GilR, are sufficient to convert 16 into 1 (Figure 3, trace D). These experiments also showed that all of the possible combinations of these remaining enzymes failed to react with 16 in the absence of GilOII. Moreover, GilOII in combination with Fre degraded 16 into an unidentified product (see Table S4 in the Supporting Information). These results indicate that GilOII is the enzyme that is responsible for the C–C bond-cleavage reaction, which is the key reaction for establishing the characteristic dibenzochromen-6-one backbone in the gilvocarcin group of natural products. At this point, it remains ambiguous whether GilM, GilMT, or GilR may be involved in this cleavage reaction. Taken together, these results suggest an alternative explanation of GV biosynthesis to all of the earlier hypotheses that suggest GilOI and/or GilOIV in complex with GilOII as a requirement for the C–C bond cleavage.[9] Among the remaining post-PKS enzymes in the gilvocarcin biosynthesis pathway, GilM and GilMT likely catalyze the remaining two O-methyl-transfer reactions. These reactions presumably occur immediately after the oxidative ring cleavage that is performed by GilOII en route to defucopregilvocarcin M (20). So far, attempts to identify the intermediates in the remaining pathway have been unsuccessful, possibly because of the unstable nature of the proposed intermediate 19b. Compound 19b needs to be generated in situ by reduction of the immediate cleavage product, which is presumably quinone 19a. Currently we are exploring this issue through the chemical synthesis of the proposed intermediates (19a, 19b, and their decarboxylated counterparts), thereby seeking clarification of the remaining ambiguous biosynthetic steps in the GV pathway.

In conclusion, we found that 15 enzymes are necessary to efficiently biosynthesize defucogilvocarcin M (1) and used them in a one-pot enzymatic total synthesis of 1 that starts from the natural building blocks acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA. This is the longest reported sequence of an enzymatic total synthesis that involves enzymes from various sources. The enzymatic total syntheses of enterocins,[18] tetracenomycins,[19] 12,[12] and vitamin B12 [20] are previous representative examples of such an approach. Combinatorial biosynthetic enzymology also confirmed that 14 and 16 are intermediates in the GV biosynthesis pathway, whereas 10 is a shunt product. Furthermore, this study revealed that GilOIV/JadF is an important enzyme that bridges between the PKS and post-PKS reactions, but does not function as an oxygenase. These results also show that GilOI is responsible for the 12-hydroxylation of 14, and that GilOII is likely to be the enzyme that is responsible for the oxidative C–C bond-cleavage reaction. To answer the remaining questions about the gilvocarcin biosynthetic pathway, the extension of the one-pot sequence towards the total synthesis of 4 is currently under examination.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants CA102102 and CA091901 from the U.S. National Institutes of Health to J.R. The mass spectrometry and NMR facilities of the University of Kentucky are acknowledged for their services.

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201105882.

Contributor Information

Pallab Pahari, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky, 789 South Limestone Street, Lexington, KY 40536-0596 (USA).

Madan K. Kharel, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky, 789 South Limestone Street, Lexington, KY 40536-0596 (USA) Midway College School of Pharmacy, 120 Scott Perry Drive, Paintsville, KY 41240 (USA).

Micah D. Shepherd, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky, 789 South Limestone Street, Lexington, KY 40536-0596 (USA) zuChem Inc., 801 W. Main Street, Peoria, IL 61606-1877 (USA).

Steven G. van Lanen, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky, 789 South Limestone Street, Lexington, KY 40536-0596 (USA)

Jürgen Rohr, Email: jrohr2@email.uky.edu, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, University of Kentucky, 789 South Limestone Street, Lexington, KY 40536-0596 (USA).

References

- 1.a) Fischer C, Lipata F, Rohr J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:7818–7819. doi: 10.1021/ja034781q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Takahashi K, Yoshida M, Tomita F, Shirahata K. J. Antibiot. 1981;34:271–275. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.34.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Hatano K, Hagashide E, Shibata M, Kameda Y, Horii S. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1980;44:1157–1163. [Google Scholar]; d) Balitz DM, O’Herron FA, Bush J, Vyas DM, Nettleton DE, Grulich RE, Bradner WT, Doyle TW, Arnold E, Clardy J. J. Antibiot. 1981;34:1544–1555. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.34.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Sehgal SN, Czerkawski H, Kudelski A, Pandev K, Saucier R, Vezina C. J. Antibiot. 1983;36:355–361. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Weiss U, Yoshihira K, Highet RJ, White RJ, Wei TT. J. Antibiot. 1982;35:1194–1201. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Li YQ, Huang XS, Ishida K, Maier A, Kelter G, Jiang Y, Peschel G, Menzel KD, Li MG, Wen ML, Xu LH, Grabley S, Fiebig HH, Jiang CL, Hertweck C, Sattler I. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:3601–3605. doi: 10.1039/b808633h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Nakajima S, Kojiri K, Suda H, Okanishi M. J. Antibiot. 1991;44:1061–1064. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.44.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Yamashita N, Shin-ya K, Furihata K, Hayakawa Y, Seto H. J. Antibiot. 1998;51:1105–1108. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.51.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsumoto A, Hanawalt PC. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3921–3926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Elespuru RK, Gonda SK. Science. 1984;223:69–71. doi: 10.1126/science.6229029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Tse-Dinh Y-C, McGee LR. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1987;143:808–812. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) McGee LR, Misra R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:2386–2389. [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Morimoto M, Okubo S, Tomita F, Marumo H. J. Antibiot. 1981;34:701–707. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.34.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Matsumoto A, Fujiwara Y, Elespuru RK, Hanawalt PC. Photochem. Photobiol. 1994;60:225–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1994.tb05095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Hua DH, Saha S. J. Royal Netherl. Chem. Soc. 1995;114:341–355. [Google Scholar]; b) Hosoya T, Takashiro E, Matsumoto T, Suzuki K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:1004–1015. [Google Scholar]; c) Futagami S, Ohashi Y, Imura K, Hosoya T, Ohmori K, Matsumoto T, Suzuki K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:1063–1067. [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Liu T, Kharel MK, Zhu L, Bright SA, Mattingly C, Adams VR, Rohr J. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:278–286. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Shepherd MD, Liu T, Mendez C, Salas JA, Rohr J. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011;77:435–441. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01774-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) Takahashi K, Tomita F. J. Antibiot. 1983;36:1531–1535. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Carter GT, Fantini AA, James JC, Borders DB, White RJ. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:255–258. [Google Scholar]; c) Carter GT, Fantini AA, James JC, Borders DB, White RJ. J. Antibiot. 1985;38:242–248. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.38.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Liu T, Fischer C, Beninga C, Rohr J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:12262–12263. doi: 10.1021/ja0467521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kharel MK, Zhu L, Liu T, Rohr J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:3780–3781. doi: 10.1021/ja0680515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takemura I, Imura K, Matsumoto T, Suzuki K. Org. Lett. 2004;6:2503–2505. doi: 10.1021/ol049261u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shepherd MD, Kharel MK, Zhu LL, Van Lanen SG, Rohr J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010;8:3851–3856. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00036a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kharel MK, Pahari P, Lian H, Rohr J. Org. Lett. 2010;12:2814–2817. doi: 10.1021/ol1009009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Kharel MK, Pahari P, Lian H, Rohr J. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:1305–1308. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Liu T, Kharel MK, Fischer C, McCormick A, Rohr J. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:1070–1077. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Noinaj N, Bosserman MA, Schickli MA, Piszczek G, Kharel MK, Pahari P, Buchanan SK, Rohr J. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:23533–23543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.247833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Kulowski K, Wendt-Pienkowski E, Han L, Yang KQ, Vining LC, Hutchinson CR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:1786–1794. [Google Scholar]; b) Rohr J, Hertweck C. In: Comprehensive Natural Products II—Chemistry and Biology. Mander L, Liu H-W, editors. Vol. 1. Oxford: Elsevier; 2010. pp. 227–303. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin S, Van Lanen SG, Shen B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12432–12438. doi: 10.1021/ja072311g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Kharel MK, Nybo SE, Shepherd MD, Rohr J. Chem-BioChem. 2010;11:523–532. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rix U, Wang C, Chen Y, Lipata FM, Remsing Rix LL, Greenwell LM, Vining LC, Yang K, Rohr J. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:838–845. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200400395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Chen YH, Wang CC, Greenwell L, Rix U, Hoffmeister D, Vining LC, Rohr J, Yang KQ. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:22508–22514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414229200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Y, Fan K, He Y, Xu X, Peng Y, Yu T, Jia C, Yang K. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:1055–1060. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng Q, Xiang L, Izumikawa M, Meluzzi D, Moore BS. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:557–558. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen B, Hutchinson CR. Science. 1993;262:1535–1540. doi: 10.1126/science.8248801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) Roessner CA, Scott AI. Chem. Biol. 1996;3:325–330. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(96)90114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Roessner CA, Scott AI. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1996;50:467–490. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.