Abstract

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) controls gene expression to transform human B cells and maintain viral latency. High-throughput sequencing and crosslinking immunoprecipitation (HITS-CLIP) identified mRNA targets of 44 EBV and 310 human microRNAs (miRNAs) in Jijoye (Latency III) EBV-transformed B cells. While 25% of total cellular miRNAs are viral, only three viral mRNAs, all latent transcripts, are targeted. Thus, miRNAs do not control the latent/lytic switch by targeting EBV lytic genes. Unexpectedly, 90% of the 1664 human 3′-untranslated regions targeted by the 12 most abundant EBV miRNAs are also targeted by human miRNAs via distinct binding sites. Half of these are targets of the oncogenic miR-17∼92 miRNA cluster and associated families, including mRNAs that regulate transcription, apoptosis, Wnt signalling, and the cell cycle. Reporter assays confirmed the functionality of several EBV and miR-17 family miRNA-binding sites in EBV latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1), EBV BHRF1, and host CAPRIN2 mRNAs. Our extensive list of EBV and human miRNA targets implicates miRNAs in the control of EBV latency and illuminates viral miRNA function in general.

Keywords: apoptosis, EBV, HITS-CLIP, miR-17∼92, viral microRNAs

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are ∼22 nt noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression in normal development (Ambros, 2011) and cancer (Di Leva and Croce, 2010). Through binding to an Argonaute (Ago) protein (human Ago1-4) and other RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) components, miRNAs directly but imperfectly base-pair to mRNA targets and regulate translation and/or mRNA stability, resulting in modest declines in protein levels (Bartel, 2004) or in switch-like protein downregulation (Mukherji et al, 2011). Bioinformatic and biochemical studies of miRNA–mRNA base-pairing show that interactions typically occur via the ‘seed’ (minimally nts 2–7) of the miRNA (Lewis et al, 2005; Grimson et al, 2007) and that most human mRNAs are miRNA targets (Lim et al, 2005; Chi et al, 2009; Friedman et al, 2009). Global identification of regulated mRNAs is key to understanding miRNA function but this has proven challenging, especially for viral miRNAs where mRNA target sites may not be evolutionarily conserved (Thomas et al, 2010).

Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infects >90% of the world population, commonly causing self-limiting infectious mononucleosis or rarely inciting a range of malignancies (Kutok and Wang, 2006), including nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC; Tao and Chan, 2007), gastric carcinoma (GC; Fukayama, 2010), lymphoproliferative disorders in immune compromised patients (Cesarman, 2011), and Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL; Rowe et al, 2009). A gammaherpesvirus, EBV, may undergo lytic replication, releasing viral progeny, or instead initiate latency in one of three patterns (Latency I, II, III) involving limited gene expression that includes Epstein–Barr nuclear antigens (EBNA1–3), latent membrane proteins (LMP1 and 2), and the noncoding RNAs EBER1, EBER2, and EBV miRNAs (Delecluse et al, 2007). Viral miRNAs were discovered in EBV (Pfeffer et al, 2004), which expresses 44 mature miRNAs (Kozomara-Griffiths-Jones, 2011) from 25 precursor-miRNAs (pre-miRNAs), the most of any known human virus (Cai et al, 2006; Grundhoff et al, 2006; Lung et al, 2009; Zhu et al, 2009; Chen et al, 2010). EBV miRNAs are encoded in two genomic clusters (BHRF1 and BART) and are expressed at various levels in tumour samples and different cell lines during viral latency (Figure 1A) and lytic growth (Cai et al, 2006; Lung et al, 2009). Most (22/25) EBV pre-miRNAs have homologues in the closely related Rhesus lymphocryptovirus (rLCV; Cai et al, 2006; Riley et al, 2010; Walz et al, 2010), and three share sequences with human miRNAs: EBV miRNA BART1-3p exhibits seed identity (nts 1–7) with human miRNA miR-29a/b/c (Park et al, 2009), nts 2–7 are shared by BART5-5p and human miRNA miR-18a/b (Gottwein and Cullen, 2008), and nts 2–8 are identical in BART22-3p (Lung et al, 2009; Zhu et al, 2009), miR-520d-5p, and miR-524-5p (Bentwich et al, 2005; Landgraf et al, 2007). EBV can also alter host miRNA expression, notably enhancing the level of oncogenic miR-155 (Gatto et al, 2008; Lu et al, 2008; Rahadiani et al, 2008; Yin et al, 2008; Linnstaedt et al, 2010), a regulator of B-cell homeostasis (Rodriguez et al, 2007).

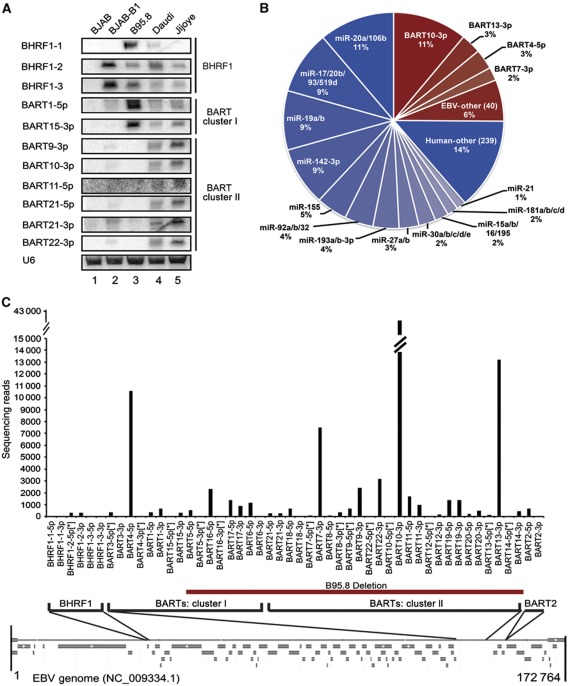

Figure 1.

HITS-CLIP analysis of EBV and human miRNAs in Jijoye cells. (A) Northern blot analysis of EBV miRNA expression in B-cell lines. BJAB is an EBV− BL; BJAB-B1 is a P3HR1 EBV+ BJAB derivative; B95.8 is a marmoset LCL line infected with B95.8 EBV, which harbours a large deletion that eliminates expression of most BART miRNAs; Daudi and Jijoye are patient-derived, EBV+ BL cell lines. All cell lines are EBV Latency III. U6 is a loading control. (B) Quality-filtered, raw sequencing reads of HITS-CLIP isolated, Ago-bound miRNAs (0 or 1 mismatch) were aligned to human (blue) or EBV (red) miRNAs in miRBASE v.17 and grouped into identical seed families. In all, 91% of total reads mapped to miRNA sequences, representing 295 unique seeds. (C) Individual miRNA sequencing reads for the 44 EBV miRNAs in miRBASE v.17 are depicted in their relative genomic locations on the Type 2 EBV RefSeq map (below). The miRNAs deleted in the B95.8 strain are noted (red bar).

Previously, specific EBV miRNAs were implicated in regulating host cell immunomodulatory targets CXCL-11 (Xia et al, 2008) and MICB (Nachmani et al, 2009), pro-apoptotic targets BBC3/PUMA and BCL2L11/BIM (Choy et al, 2008; Marquitz et al, 2011), and transport targets TOMM22 and IPO7 (Dolken et al, 2010). EBV miRNAs have also been reported to target three viral transcripts: the key transforming factor LMP1 (Lo et al, 2007), immunomodulatory protein LMP2A (Lung et al, 2009), and DNA polymerase BALF5 (Barth et al, 2008). Two phenotypic studies focusing on the BHRF1 miRNA cluster, which is highly expressed in B95.8-infected lymphoblastoid cells (LCLs), implicated EBV miRNAs in cell cycle promotion (Seto et al, 2010; Feederle et al, 2011) and/or inhibition of apoptosis during initial infection (Seto et al, 2010). Other studies characterized targets of BART miRNAs in non-B-cell cancers (NPC, GC), where they are more highly expressed than in BL (Cai et al, 2006). Little is known about the roles of BART miRNAs in B cells, in part because they are dispensable for B-cell transformation (Robertson et al, 1994); yet, they are expressed in all forms of EBV latency (Rowe et al, 2009).

Crosslinking immunoprecipitation paired with high-throughput sequencing (HITS-CLIP) identifies genome-wide Ago–miRNA–mRNA ternary complexes from a cell line or tissue. Ultraviolet (UV) crosslinking induces covalent bonding between RNAs and associated proteins inside cells. Ago is then stringently immunoprecipitated such that Ago-bound miRNAs and mRNA fragments can be separately purified and resulting cDNAs subjected to high-throughput sequencing (Chi et al, 2009). Ago HITS-CLIP can therefore interrogate host and viral miRNAs at their normal, unperturbed stoichiometries relative to each other and to mRNAs, providing a biologically relevant data set (Khan et al, 2009).

Here, we subjected unperturbed Jijoye (Latency III) BL cells to Ago HITS-CLIP. Subsequent bioinformatic analyses and luciferase reporter assays pinpointed three viral and >1500 human mRNA targets of EBV miRNAs. The Jijoye strain was selected because, unlike the B95.8 laboratory strain of EBV, it expresses all 44 EBV miRNAs reported in miRBASE (Kozomara-Griffiths-Jones, 2011), allowing the function of the full complement of EBV miRNAs to be assessed. Indeed, our complete analysis identified viral miRNAs regulating human and viral transcripts, as well as human miRNAs regulating human and viral transcripts. The 12 most highly expressed EBV miRNAs target mRNAs involved in transcription regulation, apoptosis, cell cycle control, and Wnt signalling. Only 10% of the transcripts targeted by EBV miRNAs are targeted by viral miRNAs alone. Rather, EBV miRNAs co-target mRNAs with host miRNAs, in particular with members of the miR-17∼92 miRNA cluster, a highly oncogenic group of miRNAs that induces lymphomas and inhibits apoptosis (Matsubara et al, 2007; Ventura et al, 2008; Xiao et al, 2008), and with the highly abundant immunomodulatory miRNAs, miR-142-3p and miR-155. Our study provides the first comprehensive picture of EBV miRNA function in B cells.

Results

Global analysis of Ago HITS-CLIP in Latency III B cells

To determine the role of EBV miRNAs in Latency III B cells, we first assessed EBV miRNA expression in established B-cell lines (Figure 1A). While B95.8 cells (resulting from infection with the B95.8 laboratory strain of EBV) express high levels of some EBV miRNAs (Figure 1A, lane 3; Dolken et al, 2010; Feederle et al, 2011), a well-characterized ∼12 kb deletion eliminates expression of the majority of the BART miRNAs (Pfeffer et al, 2004; Cai et al, 2006). Instead, we selected the BL cell line Jijoye, which detectably expresses all but 1 of the 44 reported EBV mature miRNAs (Cai et al, 2006) (Figure 1A, lane 5) and therefore enables a complete analysis of EBV miRNAs. Jijoye cells were initially isolated from a patient tumour, and—like most cultured BL cell lines—exhibit Latency III gene expression (Pulvertaft, 1964; Drexler and Minowada, 1998).

We applied Ago HITS CLIP (developed by Chi et al (2009); reviewed by Darnell (2010)) to Jijoye cells in six biological replicates, three experiments each with anti-Ago monoclonal antibodies 2A8 (Nelson et al, 2007) or 11A9 (Rudel et al, 2008), which co-immunoprecipitate (co-IP) UV-crosslinked Ago-miRNA–mRNA complexes (Supplementary Figure 1A). After RNase trimming, the Ago–RNA complexes were separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose, and the lower (LO∼110 kDa) and higher (HI∼118–130 kDa) molecular weight species separately isolated (Ago alone migrates at ∼100 kDa; Supplementary Figure 1B). After reverse transcription of extracted RNA and subsequent PCR, Ago-bound miRNAs (from one 11A9 co-IP) and mRNA samples (six total, three from each antibody) were subjected to Illumina high-throughput sequencing (read and alignment statistics in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The LO sample (Supplementary Figure 1B and C, lanes 3 and 4, Supplementary Table 1) yielded mainly miRNAs (∼90% of 22.6 million raw sequencing reads), while the HI sample (Supplementary Figure 1B and C, lanes 6 and 7) contained both miRNAs and longer mRNA fragments.

Of the total LO sequencing reads mapping with 0 or 1 mismatch to miRBASE v.17 (Kozomara-Griffiths-Jones, 2011) sequences, 25% were the 44 known EBV miRNAs and 75% corresponded to 310 human miRNAs (Figure 1B). The most abundant miRNA was EBV miRNA BART10 (BART10-3p), representing ∼11% of miRNA reads (Supplementary Table 3). Because miRNA functionality is based on interactions between the miRNA seed and mRNA, we grouped the miRNA sequencing reads by seed family (identity in nts 1–8; Figure 1B). The miR-20a/106b family (UAAAGUGC) comprised ∼11% of total Ago-bound miRNA reads, and the related miR-17/20b/93/519d family (CAAAGUGC) represented 9%. Together, the sum of sequencing reads for the members of the miR-17∼92 cluster (miR-17, 18a, 19a, 20a, 19b, 92a) and their associated seed families (additionally including miR-18b, 19b, 20b, 32, 92b, 93, 106a/b, and 519d) represented ∼35% of all seeds. EBV miRNAs do not group into seed families, yet BART10-3p was so abundant that its seed alone (UACAUAAC) represented the second largest seed family (also ∼11%; Figure 1B).

As in previous studies (Pfeffer et al, 2004; Cai et al, 2006), levels of different EBV miRNAs varied widely, with the most abundant being BARTs originating from both clusters (Figure 1C). The 12 most highly expressed EBV miRNAs together comprise 90% of the EBV miRNA reads and 22% of total miRNA reads (Supplementary Table 3). Thus, this group was selected for detailed analysis. While BHRF1-2 levels are equivalent in B95.8 and Jijoye cells, BHRF1-3 levels are somewhat reduced, possibly due to a 1-nt mutation 159 nts downstream of the BHRF1-3 pre-miRNA, which was identified by HITS-CLIP and confirmed by cloning (unpublished observations). BHRF1-1 is not visible in northern blots (Figure 1A) because of a Jijoye-specific point mutation in pre-BHRF1-1 (Pfeffer et al, 2004; Cai et al, 2006), but is clearly present in our HITS-CLIP data (Supplementary Table 3).

The Ago-bound mRNA sequencing reads (9.4–35.9 million raw reads in each of the six replicates) were collapsed and aligned to the human (hg18; Supplementary Tables 1 and 2A) and to the EBV genome (Dolan et al, 2006; NC_009334.1; Supplementary Table 2B). As expected for latently infected cells, many more reads (99.4% of unique mappable reads) aligned to the hg18 than the EBV (0.6%) genome. Peak height (PH) and biologic complexity (BC) are metrics assessing the quality of a given cluster (Chi et al, 2009); for our analysis we defined clusters as five overlapping reads reproduced in at least three of six experiments (PH ≥5, BC ≥3; see Supplementary Methods). Mapping these peaks to the human RefSeq database yielded a distribution of Ago binding similar to that seen previously in HeLa cells and mouse brain (Chi et al, 2009), where reproducible clusters primarily aligned to extended 3′-untranslated regions (3′UTRs; 40%) or to coding sequences (CDS; 31%); fewer 5′UTR, intron, and intergenic/noncoding RNA clusters were detected (Supplementary Figure 1D). Reproducible clusters were searched for seed base-pairing potential (minimally nts 2–7) to Jijoye miRNAs. As reported (Chi et al, 2009), the frequency of potential mRNA-binding sites for a given seed sequence loosely correlated with miRNA abundance (Supplementary Figure 2).

EBV and host miRNAs co-target three viral mRNAs in EBV Latency III

The landscape of unique sequence reads (≥25 nts, 0–2 mismatches) on the EBV genome comprises four major peaks overlapping three mRNAs and the BART noncoding RNAs (Figure 2, bottom). EBNA2 is expressed in EBV Latency III to control transcription of several host and viral genes (Zimber-Strobl and Strobl, 2001). Our HITS-CLIP results show broad clusters of Ago binding over the entire length of the EBNA2 transcript with few robust peaks (Figure 2A) or predicted miRNA-binding sites (Supplementary Figure 3). In contrast, distinct peaks reside within the 3′UTRs of BHRF1 (Figure 2B) and LMP1 (Figure 2C) mRNAs. BHRF1 (discovered by Cleary et al (1986), reviewed by Cuconati-White (2002)) encodes a homologue of the host BCL2 anti-apoptotic protein and is expressed at low levels in EBV Latency III (Kelly et al, 2009). Two large peaks on the BHRF1 3′UTR (BC=5 or 6) overlap predicted miRNA-binding sites for the most highly abundant human (miR-17 family, miR-142-3p) and EBV (BART10-3p) miRNAs (Figure 2B). Similarly, LMP1 (reviewed by Middeldorp-Pegtel (2008)), which mimics the host gene CD40 and activates multiple signalling pathways, has two distinctive 3′UTR peaks with binding sites for EBV (BARTs 19-5p and 5-5p) and human (miR-17 family) miRNAs (Figure 2C), as well as ‘orphan’ peaks containing no predicted canonical miRNA seed-binding sites near the 3′ end (Chi et al, 2009). The peak on the EBV genome-labelled ‘BARTs’ (Figure 2, below) represents Ago-bound pre-miRNAs of EBV BART miRNAs. Since the BART miRNAs are processed from noncoding transcripts (Al-Mozaini et al, 2009) and the base-pairing between the 5p and 3p miRNAs is highly bulged in most cases (Kozomara-Griffiths-Jones, 2011), it is unlikely that the BART miRNAs are self-targeting their own pre-miRNAs. Ago protein can both exist in the nucleus (Weinmann et al, 2009) and bind pre-miRNAs (Tan et al, 2009), though why these possibly nuclear pre-miRNAs bind Ago is not known.

Figure 2.

Viral and human miRNAs co-regulate EBV genes. RefSeq (NC_009334.1) map of the Type 2 EBV genome (bottom, CDS grey, coordinates noted) aligned with HITS-CLIP deep sequencing reads (0 or 1 mismatch; ≥25 nts long) from six biological replicates of Ago-bound RNAs in Jijoye BL cells (unique reads, one colour per biological replicate). The EBV pre-miRNAs from the BART region are selectively and reproducibly Ago-bound. Inset boxes are expanded, scaled views of the three major mRNA peaks (A, B, C). (A) The EBV nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA2) reads overlap the entire EBNA2 CDS (grey). The precise coordinates of the 5′ and 3′UTRs (black and white, respectively) of Jijoye EBV EBNA2 and EBNA-LP are unknown, as indicated by jagged boundaries. (B) The BHRF1 (Bam HI fragment H rightward open reading frame 1) peak (coordinates are annotated ends of the UTRs) contains several robust, validated miRNA-binding sites designated below by vertical bars. (C) The latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) reads map to the 3′UTR and indicate coordinate binding by at least two validated viral miRNAs and one human miRNA family.

To validate our HITS-CLIP findings and confirm direct miRNA–mRNA interactions, we cloned the full-length Jijoye LMP1 3′UTR (Figure 3A) into a dual-luciferase reporter vector. We first asked if inactivation of endogenous miR-17 family miRNAs upregulates the level of luciferase. Since the miR-17 family of miRNAs is highly expressed in all transfectable cell lines tested (unpublished observations), we employed tiny locked nucleic acids (tiny LNAs): 8-mer, anti-seed sequence, modified oligonucleotides (Obad et al, 2011; Supplementary Table 4) to inactivate all miR-17 family members. Indeed, expression of the luciferase-LMP1 3′UTR increased with anti-miR-17, but not a control tiny LNA, in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3B, left). Further, a control LMP1 3′UTR with point mutations in the expected miR-17 family seed-binding site (Figure 3A) did not respond to anti-miR-17 (Figure 3B, right). We then tested miRNAs with excellent base-pairing potential to the LMP1 3′UTR: EBV miRNAs BART19-5p, BART5-5p, and BART11-5p, and human miRNAs miR-17-5p and miR-18a-5p. While miR-17-5p, BART19-5p, or BART5-5p synthetic miRNAs (Supplementary Table 4) repressed the WT (but not point mutant) LMP1 3′UTR, miR-18a-5p and BART11-5p did not (Figure 3C). Both miR-18a-5p and BART11-5p efficiently repressed artificial sensor reporters (unpublished observations). Thus, regulation of LMP1 is specific to BART5-5p and not miR-18a-5p, even though these miRNAs share seed sequence identity (nts 2–7; Figure 3A). When BART19-5p and BART5-5p were co-transfected at the same total concentration of synthetic miRNA, repression was further enhanced, indicating that these viral miRNAs cooperate to repress LMP1. Jijoye cell nucleofection of tiny LNAs (Figure 3D, lanes 1 and 2) or synthetic miRNAs (Figure 3D, lanes 3–6) resulted in up- or downregulation of endogenous LMP1 protein, respectively. We conclude that LMP1 mRNA is regulated by at least two EBV miRNAs and one host miRNA family.

Figure 3.

EBV LMP1 is co-regulated by EBV and human miRNAs. (A) The full-length LMP1 3′UTR (1215 nts; top) was cloned downstream of firefly luciferase in the pmiRGLO dual-luciferase vector, with either wild-type Jijoye sequence or point mutations in putative miRNA-binding sequences (noted below, red nts). Relative locations of proposed binding sites for BART19-5p (B19), hsa-miR-18 (18), BART5-5p (B5), and BART11-5p (B11), and the human miR-17 miRNA family (17; blue) are noted. Sequences of WT LMP1 and mutants disrupting the seed-binding site for BART19-5p (B19m), BART5-5p (B5m), BART11-5p (B11m), or miR-17 family (17m) are shown with potential base-pairing of the miRNAs to the WT mRNA sequences indicated. (B) HEK293T cells were co-transfected with a luciferase-LMP1 (WT or miR-17 family point mutant 17m) reporter and either water (mock), a negative control tiny LNA (Ctl), or the anti-miR-17 family tiny LNA (anti-17) at one of two concentrations. Firefly/Renilla luciferase ratios were normalized to the 17m mock-transfected reporter. (C) HEK293T cells were co-transfected with a firefly luciferase-LMP1 (WT or point mutants from A) reporter and either 40 nM total synthetic control miRNA duplex (CTL; scrambled sequence) or 1–2 EBV miRNAs predicted to base-pair with the LMP1 3′UTR. Firefly/Renilla luciferase ratios were normalized to the same reporter transfected with the negative control miRNA (CTL). In all luciferase assays, mean values were from at least four independent transfections. Error bars, s.d. P values from two-tailed Student’s t-tests of noted sample relative to CTL, ***P<0.002. (D) Five million Jijoye cells were nucleofected with either a tiny LNA (55 pmol; lanes 1 and 2) or a synthetic miRNA duplex (10 pmol; lanes 3–6). Endogenous LMP1 was detected at 48 h post-nucleofection by western blot, and GAPDH was used as a loading control.

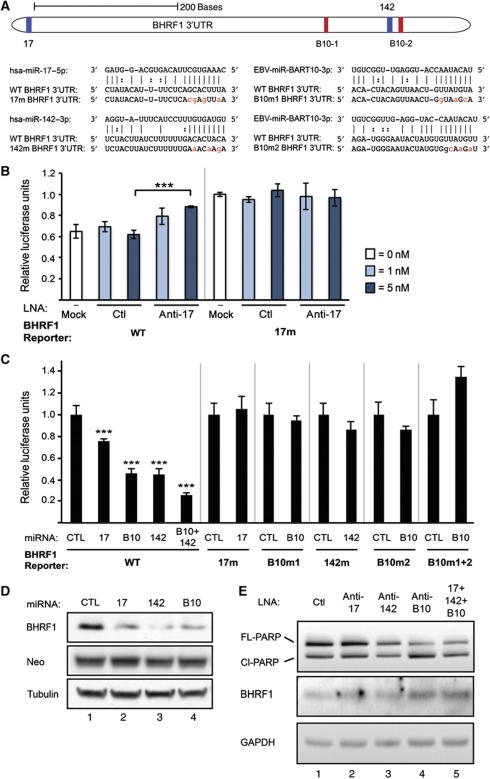

We used a similar approach to validate BHRF1 repression by miR-17 family miRNAs, miR-142-3p, and BART10-3p (Figure 4A–D). Again, we observed significant upregulation of luciferase fused to the WT full-length BHRF1 3′UTR upon treatment with anti-miR-17 but not with the control tiny LNA (Figure 4B). Repression occurred upon addition of miR-17-5p, miR-142-3p, or BART10-3p synthetic miRNAs (Figure 4C). BART10-3p targets the BHRF1 3′UTR at two sites that both contribute to downregulation (Figure 4A and C). Co-transfection of equal parts miR-142-3p and BART10-3p yielded even greater repression (Figure 4C). As expected, mutant reporters did not respond to tiny LNAs or synthetic miRNAs (Figure 4B and C). We also tested the effects of miR-17-5p, miR-142-3p, and BART10-3p on BHRF1 protein levels. These synthetic miRNAs decreased co-transfected BHRF1 relative to the negative control miRNA (Figure 4D). Moreover, tiny LNA inhibition of miR-17-5p, miR-142-3p, and BART10-3p upregulated endogenous BHRF1 protein in Jijoye cells (Figure 4E), especially when used in combination (Figure 4E, lane 5). Together, these results confirm that EBV and host miRNAs co-repress the BHRF1 mRNA, reducing protein output, and that host and viral miRNAs can have a cumulative effect on targets.

Figure 4.

EBV BHRF1 is co-regulated by EBV and human miRNAs. (A) The full-length BHRF1 3′UTR (634 nts; top) with either the wild-type Jijoye sequence or mutations in putative miRNA-binding sequences (below, red nts) was cloned downstream of firefly luciferase in the pmiRGLO dual-luciferase vector. The relative locations of binding sites for human miRNAs (17=hsa-miR-17 family, 142=hsa-miR-142-3p; blue) and two sites for EBV miRNA ebv-miR-BART10-3p (B10-1 and B10-2, red) are noted. Sequences are shown for the wild-type 3′UTR, for point mutants in the seed-binding site for miR-17-5p (17m), miR-142-3p (142m), or one of two sites for BART10-3p binding (denoted B10m1 and B10m2, assigned 5′ to 3′), and for the miRNAs. (B, C) HEK293T cells were co-transfected with a BHRF1-luciferase reporter and tiny LNAs or synthetic miRNAs as in Figure 3B and C. ‘CTL’ is synthetic BART5-5p, which does not have predicted binding sites in BHRF1. In all luciferase assays, mean values were from at least four independent transfections. Error bars, s.d. P values from two-tailed Student’s t-tests of noted sample relative to CTL, ***P<0.0001. (D) HEK293T cells were co-transfected with pcDNA3-BHRF1 (full-length WT BHRF1, coordinates in Figure 2B) and the designated host or viral miRNA. BHRF1 protein levels were determined 24 h post-transfection by western blot. Neomycin phosphotransferase (Neo) from pcDNA3 and endogenous α-tubulin were the transfection/loading controls. (E) Five million Jijoye cells were nucleofected with 55 pmol total tiny LNA (lane 5 is a 1:1:1 mix). Endogenous full-length/cleaved PARP and BHRF1 levels were determined 48 h post-nucleofection by western blot, and endogenous GAPDH was a loading control.

Lytic BHRF1 is anti-apoptotic, but little is known about its function in latency (Kelly et al, 2009); our HITS-CLIP data predict that many host apoptotic genes are also regulated by EBV miRNAs (Supplementary Table 5A). We therefore asked if miRNAs that downregulate BHRF1 protein might enhance apoptosis in latent Jijoye cells. Even though nucleofection itself induces significant apoptosis in EBV+ B cells (Hatton et al, 2011), nucleofection with tiny LNAs blocking miR-17 family miRNAs, miR-142-3p, and BART10-3p in latent Jijoye cells (Figure 4E) further increases both the low levels of endogenous BHRF1 and apoptosis, as indicated by increased PARP cleavage (Figure 4E). Thus, a phenotypic effect of BART10-3p is the inhibition of apoptosis, which could be explained by the involvement of 32 other apoptosis-associated genes predicted to be regulated by BART10-3p (Supplementary Table 5B).

EBV miRNAs target human mRNAs involved in transcription, apoptosis, Wnt signalling, and cell cycle control

The limited number of Ago HITS-CLIP peaks aligning to the EBV genome predicts that the vast majority of EBV miRNA targets are human mRNAs. Our HITS-CLIP data indeed revealed hundreds of EBV miRNA-binding sites in human 3′UTRs and coding regions (Supplementary Figure 1D), including previously validated TOMM22, IPO7, BBC3/PUMA, and BCL2L11/BIM transcripts. However, we identified additional and often more robust sites of miRNA binding in each of these 3′UTRs (Supplementary Figure 4).

One advantage of the HITS-CLIP biochemical/bioinformatic approach is the ability to identify all Ago–miRNA–mRNA ternary complexes simultaneously. For EBV, it seemed likely that the highly expressed, co-transcribed BART miRNAs might operate coordinately. Thus, we examined genes targeted by the 12 most highly expressed EBV miRNAs in Jijoye cells (Supplementary Table 3) for their assignment to particular gene families or pathways. Specifically, we subjected the 1664 human 3′UTRs with one or more canonical seed-binding sites (minimally nts 2–7; clusters PH ≥5, BC ≥3) for the highly abundant EBV miRNAs to gene ontology (GO) analysis using DAVID v.6.7 (Huang da et al, 2009a; Huang da et al, 2009b). The most enriched categories were transcription regulation (20% of annotated genes; P<9×10−13, Fisher’s exact test) and apoptosis (8% of annotated genes; P<1×10−12; Supplementary Table 5A). Other significantly enriched pathways are in Table I.

Table 1. GO term analysis.

Of 1664 genes targeted by the 12 most abundant EBV miRNAs, 1586 were identified in DAVID databases. Total number of genes per category using the GO FAT term set (#), percentage of total EBV miRNA targets (%) and P-value (Fisher's exact test) are listed.

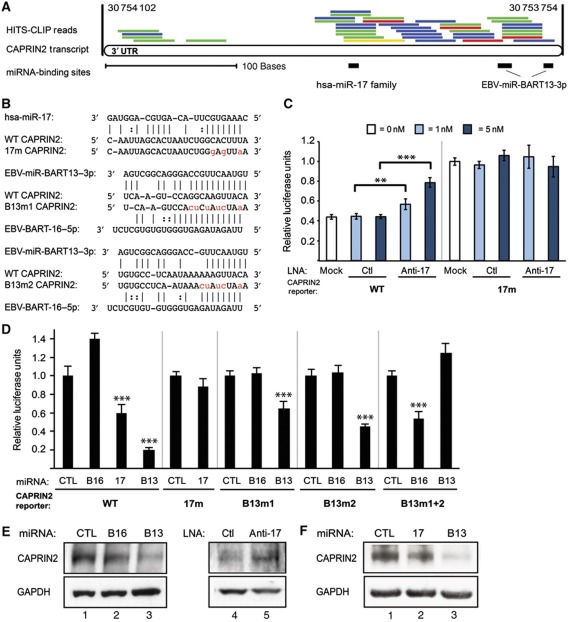

A recent report suggested (Wong et al, 2012) and our results confirm that the EBV miRNAs regulate the Wnt-signalling pathway, with 20 genes listed in Supplementary Table 6. CAPRIN2 is a Wnt-signalling enhancer (Ding et al, 2008) whose overexpression also enhances apoptosis (Aerbajinai et al, 2004). Sequencing tags overlap a binding site for miR-17 family miRNAs and two BART13-3p sites in the CAPRIN2 3′UTR (Figure 5A). Repression via these sites was confirmed in luciferase assays (Figure 5B–D) and western blot analyses (Figure 5E and F).

Figure 5.

Human gene CAPRIN2 is co-regulated by EBV and human miRNAs. (A) RefSeq (hg18) map of the human CAPRIN2 3′UTR (349 nts; chromosome 12 coordinates) aligned with HITS-CLIP deep-sequencing reads from six biological replicates of Ago-bound RNAs in Jijoye B cells (raw unique reads, one colour per biological replicate). Relative locations of binding sites for human miR-17 family miRNAs and two EBV miRNA BART13-3p sites are denoted by black bars (drawn to scale below). (B) Sequence of CAPRIN2 miRNA-target sites with point mutations (red) in the seed-binding sites for miR-17-5p (17m) or one of two sites for BART13-3p binding (B13m1 and B13m2). The mutations in the BART13-3p-binding sites convert them into binding sites for an unrelated miRNA, ebv-miR-BART16-5p. (C, D) HEK293T cells were transfected with the designated luciferase-CAPRIN2 reporters and tiny LNA or synthetic miRNA as in Figures 3B and C. In all luciferase assays, mean values were from at least four independent transfections. Error bars, s.d. P values from two-tailed Student’s t-tests of noted pairs, ***P<0.001 or **P<0.01. (E) HEK293T cells were transfected with a control or test synthetic miRNA duplex (40 nM) or tiny LNA (5 nM). Western blots of extracts prepared 24 h post-transfection were probed for endogenous proteins with anti-CAPRIN2 or anti-GAPDH antibodies. (F) Jijoye cells were transfected with a control or test synthetic miRNA duplex (100 nM) and analysed as in E.

EBV miRNAs co-target human mRNAs with human miRNAs

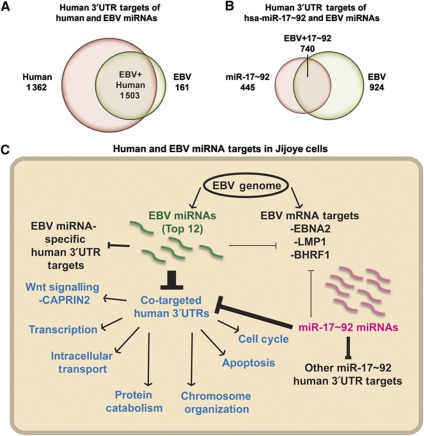

We identified 2865 human 3′UTRs that bind the 56 most highly expressed human miRNAs in Jijoye cells and compared this list to the 1664 3′UTRs targeted by EBV miRNAs. Of the latter, 90% contain one or more binding sites for human miRNAs, leaving 10% (161) of 3′UTRs with binding sites for EBV miRNAs alone (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

EBV miRNA and host miRNA targeting in EBV Latency III. (A) Overlap between the human 3′UTR targets for the 12 most highly expressed EBV miRNAs (green) and for the 56 most highly expressed human miRNAs (pink) in Jijoye cells (BC ≥3, PH ≥5 unique sequencing reads). Annotations are from RefSeq. (B) Overlap between the human 3′UTR targets for the 12 most highly expressed EBV miRNAs (green) and for the human miR-17∼92 miRNAs (pink) as in A. (C) Summary of HITS-CLIP-identified 3′UTR targets of human and EBV miRNAs in Jijoye cells. While a small fraction of the EBV miRNA sites in 3′UTRs are human transcripts targeted by EBV miRNAs alone (10% of all targets), 90% of human 3′UTR targets and at least two-third of the EBV mRNA targets of EBV miRNAs are co-targeted by one or more human miRNA. We validated co-targeting by EBV BARTs and human miR-17∼92 miRNAs of the LMP1, BHRF1, and CAPRIN2 mRNAs. Transcripts co-targeted by the miR-17∼92 and EBV miRNAs, representing 60% of all miR-17∼92 targets in Jijoye cells, are enriched in at least seven major GO categories (blue; also see Table I).

Since many targets of EBV miRNAs (LMP1, BHRF1, CAPRIN2, MICB, and BCL2L11/BIM) bind host miR-17∼92 family miRNAs, we analysed the extent of viral/host miRNA cooperation. The oncogenic miR-17∼92 cluster cooperates with c-myc in a mouse model of B-cell lymphoma (He et al, 2005) and is overexpressed in BL (Inomata et al, 2009) and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma due to amplification at 13q31-q32 (Ota et al, 2004). Our HITS-CLIP data yield 1185 human 3′UTRs targeted by members of the miR-17∼92 cluster in Jijoye cells. Comparison to the 1664 3′UTRs targeted by EBV miRNAs reveals 740 shared genes (44% of EBV targets and 62% of miR-17∼92 targets; Figure 6B and Supplementary Table 7). Thus, EBV miRNAs co-target a majority of miR-17∼92 regulated mRNAs, which are assigned to a variety of pathways, most notably regulating transcription, apoptosis, and the cell cycle (Figure 6C). Similarly, other abundant immunologically relevant miRNAs, 142-3p and miR-155, co-target with EBV miRNAs a large fraction of their Ago-bound 3′UTRs, representing ∼60% of the targets for each of these host miRNAs (Supplementary Figure 5).

Discussion

We used the highly stringent HITS-CLIP biochemical approach combined with bioinformatic analyses to identify EBV miRNA targets in 1664 human 3′UTRs and three viral mRNAs, and human miRNA targets in 2865 human 3′UTRs. The scale and depth of our data set reveal that co-targeting of 3′UTRs by human and viral miRNAs is a predominant theme underlying miRNA function for this virus.

Contribution of EBV miRNAs to viral latency

While EBV miRNAs comprise a quarter of all Ago-bound miRNA sequencing reads in Jijoye Latency III cells, only three of the ten documented EBV latent transcripts (Rowe et al, 2009) are bound by miRNAs. The largest HITS-CLIP mRNA peaks on the EBV genome (Figure 2) overlap latent genes EBNA2, BHRF1, and LMP1. This observation sharply contrasts the situation in Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV). KSHV miRNAs prevent spontaneous lytic activation by targeting a lytic transcription factor (reviewed by Boss et al (2009); Ziegelbauer (2011)), and mature miRNAs from at least a quarter of the KSHV pre-miRNAs have been shown to repress the latent-lytic switch protein Rta (Bellare and Ganem, 2009; Lu et al, 2010; Lin et al, 2011). EBV miRNAs appear not to control the latent-to-lytic transition via viral mRNA targeting (Seto et al, 2010), since no HITS-CLIP tags appeared for the EBV latent-lytic switch transcripts BZLF1 (ZEBRA, Zta) and BRLF1 (Rta) (Yu et al, 2007) in Jijoye cells (Figure 2).

Viral LMP1 was one of the first validated targets of EBV miRNAs (Lo et al, 2007). Targeting this protein may prevent it from rising to exceptionally high levels, which can induce apoptosis (Lu et al, 1996). The sequences of two EBV miRNAs previously proposed to regulate LMP1, BART16, and BART17-5p, were misannotated (Grundhoff et al, 2006; Landgraf et al, 2007). BART1-5p could play a role in LMP1 regulation, but no robust peaks over the three previously reported binding sites appear (Lo et al, 2007). Instead, we observe that LMP1 is highly targeted by both host (miR-17 family) and two other EBV (BARTs 5-5p and 19-5p) miRNAs (PH=21–37; BC=5 or 6; Figure 2).

Why BHRF1 mRNA is targeted by EBV miRNAs is more enigmatic. After EBV infection, BHRF1 protein levels spike to provide immediate inhibition of apoptosis, which is required to establish EBV infection (Altmann and Hammerschmidt, 2005) and confer a survival advantage in BL cells (Kelly et al, 2009). BHRF1 was originally classified as a lytic gene, but recent studies reveal its co-expression with EBNA-LP and EBNA2 shortly after B-cell infection, while low levels of transcript and protein persist in Latency III cells (Rowe et al, 2009). Thus, miRNAs downregulate BHRF1 during a window of viral latency when the transcript is already expressed at very low levels and the protein is nearly undetectable (Kelly et al, 2009). Our data suggest that inhibition of the miR-17 family, miR-142-3p, and BART10-3p, concurrent with BHRF1 protein upregulation in Jijoye cells, results in increased apoptosis (Figure 4E). Clearly, control of apoptosis is complex and Jijoye miRNAs regulate many apoptotic transcripts in addition to BHRF1 (Supplementary Table 5), but why EBV evolved multiple sites for viral and human miRNAs in the 3′UTR of BHRF1 and how these interact with other apoptotic regulatory mechanisms in Latency III cells require further study.

EBNA2 is a potent transcriptional activator of LMP1 (Wang et al, 1990), making it reasonable that both transcripts be targeted by miRNAs in Latency III. However, the evenly distributed pattern of peaks across the EBNA2-coding region is unusual for Ago (Chi et al, 2009), more strikingly resembling the pattern of FMRP binding to CDS (Darnell et al, 2011). Interestingly, 1285 human transcripts are predicted to be targeted in coding regions by the 12 most abundant EBV miRNAs in Jijoye cells, but base-pairing predictions yielded only several miRNA-binding sites across the EBNA-LP/EBNA2 transcript (Supplementary Figure 3). Generally, little is known about the function of Ago-CDS interactions, although many such events are predicted (Lewis et al, 2005) and human miR-148 regulates splice variants of human DNMT3b via CDS binding (Duursma et al, 2008). Two KSHV transcripts containing identical binding sites for the same miRNA in either the CDS or 3′UTR showed downregulation of protein output for the CDS site, but more potent 3′UTR-mediated repression (Lin and Ganem, 2011). A recent report details miRNA-independent Ago–mRNA interactions that attenuate translation elongation in vitro (mammalian) and in Caenorhabditis elegans (Friend et al, 2012), an explanation that would be consistent with the HITS-CLIP pattern and the lack of robust miRNA-binding sites on EBNA2.

Consistent with bioinformatic miRNA target predictions (Lewis et al, 2005; Lim et al, 2005) and previous global biochemical screens (Chi et al, 2009), we find that miRNA target sites rarely occur within 5′UTRs. One exception is in human cytomegalovirus where a viral miRNA regulates several cell cycle genes via their 5′UTRs (Grey et al, 2010). We identified only 80 genes whose 5′UTRs have potential binding sites for one or more of the 12 most highly expressed EBV miRNAs.

The miRNA targeting of EBV Latency III transcripts (BHRF1, LMP1, EBNA2) in Jijoye cells has direct implications for post-transplant and AIDS-associated lymphoproliferative disorders, which usually exhibit Latency III (Rowe et al, 2009). Comparative HITS-CLIP experiments could address intriguing questions about the function of miRNAs in different EBV-positive cell lines, tissues, and EBV life-cycle stages because EBV exhibits marked tropism (Tao and Chan, 2007; Rowe et al, 2009; Fukayama, 2010; Cesarman, 2011), and miRNA function is contextually dependent (Sood et al, 2006). For example, most freshly isolated BL tumours express just one viral mRNA, EBNA1 (Latency I; Rowe et al, 2009). HITS-CLIP data from NPC and GC (epithelial cancers) would also complement the present data set, as the BART miRNAs are generally present at higher levels in NPC and the BHRF1 miRNAs are not expressed (Cai et al, 2006). Major differences in host and viral mRNA expression are observed upon lytic induction, while EBV miRNAs continue to be expressed (Cai et al, 2006). Further afield would be analyses of rLCV miRNAs in primate B cells, since 88% of EBV miRNAs are syntenic and exhibit sequence similarity to rLCV miRNAs; yet rLCV expresses at least 20 additional mature miRNAs (Riley et al, 2010).

EBV miRNA targeting and co-targeting of the human transcriptome

We demonstrate that abundant EBV BART miRNAs likely target at least 132 apoptotic mRNAs (Supplementary Table 5A) in Latency III, greatly extending previous evidence implicating EBV miRNAs in apoptosis regulation (Choy et al, 2008; Seto et al, 2010; Marquitz et al, 2011). Upon infection of primary human B cells, deletion mutants lacking the BHRF1 miRNAs more frequently undergo spontaneous apoptosis than WT 2089 EBV (Seto et al, 2010). BARTs regulate BBC3/PUMA (Choy et al, 2008) and BCL2L11/BIM (Marquitz et al, 2011), both of which affect responses to apoptotic stimuli in epithelial cells. BCLAF1, a pro-apoptotic protein and transcriptional repressor (Sarras et al, 2010), was elegantly validated as a KSHV miRNA target (Ziegelbauer et al, 2009) and is co-targeted by at least one EBV miRNA (BART17-5p) and miR-142-3p in our data (Supplementary Figure 5B). Apoptosis is an exquisitely orchestrated cellular event involving hundreds of genes, some of which can be both pro- and anti-apoptotic, depending on their expression levels and/or cellular context. EBV miRNAs likely fine-tune specific apoptotic transcripts to tip the balance of gene expression to favour latency. Thus, teasing out the contribution of individual genes is more difficult and less meaningful than documenting their collective influence, which is demonstrated by our results (Figure 4E).

EBV joins a growing list of viruses whose mRNAs tolerate or evolve host miRNA-binding sites, including hepatitis C virus (Jopling et al, 2005; Pedersen et al, 2007) and HIV-1 (Huang et al, 2007; Ahluwalia et al, 2008; Nathans et al, 2009). EBV evolved sites in the 3′UTRs of at least two latent mRNAs (LMP1 and BHRF1) for binding the human miR-17 miRNA family, which comprises the most abundant miRNA family in Jijoye and other BL cell lines because of a well-characterized genomic amplification of the miR-17∼92 cluster, containing six pre-miRNAs (Ota et al, 2004). Inhibition of overexpressed miR-17∼92 miRNAs induces apoptosis (Matsubara et al, 2007), though only modestly in Jijoye cells (Figure 4E, lane 2). The miR-17∼92 miRNA cluster and the EBV BART miRNAs also share polycistronic expression, seed conservation between human miR-18a/b and EBV BART5-5p, and now a common pool of ≥740 co-targeted 3′UTRs (Supplementary Table 7). Thus, the EBV BART miRNAs could have evolved from expansion of the human miR-17∼92 cluster. Interestingly, we observed that miR-18a and BART5-5p, despite sharing seed sequences, do not compete for binding to LMP1 mRNA; rather, the more abundant miR-18a (Supplementary Table 3) does not repress LMP1 (Figure 3C), possibly because the predicted LMP1-miR-18 duplex is ∼20% weaker, and the seed is shifted by 1 nt (Figure 3A). We validated three co-targets of viral and human miRNAs for which the cumulative effect of viral/viral or viral/human miRNAs enhances repression of the target (Figures 3, 4, 5). Many of these co-targets would not have been identified in a subtractive HITS-CLIP approach; their miRNA-binding sites are often close enough to appear as a single cluster (Figures 2B and 5). Unlike the BART1-3p, BART5-5p, and BART22 miRNAs, which have seed sequences similar to human miRNAs and could therefore compete for binding the same sequences, miR-17∼92 and EBV miRNAs target distinct sites in the same mRNAs to exert either additive or synergistic downregulation, acting in essence as selective enhancers of miR-17∼92 miRNAs (Figures 3, 4, 5).

Like the miR-17∼92 cluster, the highly abundant, immunomodulatory host miRNAs miR-155 and miR-142-3p co-target genes with EBV miRNAs (Supplementary Figure 5). Overexpression of miR-155 produces lymphomas (Eis et al, 2005; O’Connell et al, 2009). KSHV encodes a miR-155 orthologue (Gottwein et al, 2007; Skalsky et al, 2007) and EBV upregulates human miR-155 (Yin et al, 2008). Co-targeting is seen specifically in INPP5D (SHIP1), a key miR-155 target implicated in lymphomagenesis (O’Connell et al, 2009), which is also bound by an EBV miRNA (Supplementary Figure 5D). Each host miRNA also binds a subset of 3′UTRs that are not co-targeted by EBV miRNAs (Figure 6A and C).

We now realize that even the few targets of EBV miRNAs previously reported are co-targeted by additional EBV and human miRNAs. Inhibition of BART5-5p miRNA confers susceptibility to etoposide-induced apoptosis in NPC (Choy et al, 2008) via regulation of BBC3/PUMA, a p53-induced pro-apoptotic gene with a 3′UTR-binding site for BART5-5p. We obtained a single unique sequencing read that overlaps this site, but a more robust BART19-5p site appears downstream (Supplementary Figure 4). BCL2L11/BIM, another pro-apoptotic host gene, was validated as a BART miRNA target in GC (Marquitz et al, 2011). Our data confirm some of the proposed EBV miRNA-binding sites in BCL2L11/BIM, but show larger peaks for host miRNAs of the miR-17 and miR-92a/b,32 families (Ventura et al, 2008; Xiao et al, 2008). The stress-induced immune ligand MICB was validated as a target of BART2-5p in EBV+ 721.221 B cells (Nachmani et al, 2009). We find a small cluster of HITS-CLIP sequencing reads that abuts but does not overlap this site in the MICB 3′UTR (Supplementary Figure 4) and several more robust peaks for human and EBV miRNAs, notably the miR-17 family, miR-155, miR-29, BART9-3p, and BART5-5p (Supplementary Figure 4). Intracellular transport proteins TOMM22 and IPO7 were identified as targets of BART16-5p and BART3-3p, respectively, in Jijoye cells (Dolken et al, 2010). Our data validate these findings (Supplementary Figure 4): TOMM22 is one of the 161 EBV miRNA-only targets, while IPO7 is also targeted by many less-abundant host miRNAs. We did not observe sequencing reads aligning with host CXCL-11 (Xia et al, 2008; as in another study of Jijoye cells (Dolken et al, 2010)), viral LMP2A (previously validated in NPC (Lung et al, 2009)), or viral BALF5 (Pfeffer et al, 2004; Barth et al, 2008) mRNAs. However, the EBV miRNAs implicated are all expressed at relatively low levels in Jijoye cells (Figure 1C), the siRNA-like activity proposed to regulate BALF5 might not be captured by HITS-CLIP, and crosslinking efficiency may vary for different miRNA–mRNA interactions.

To complement identification of individual EBV miRNA targets, others have studied EBV miRNAs collectively in B cells (Dolken et al, 2010; Seto et al, 2010; Gottwein et al, 2011). Seto et al assessed the influence of EBV miRNA subsets on the transformation and growth of LCLs in B95.8-based strains, including all or none of the BHRF1 or BART miRNAs. While enticing conclusions about BHRF1 miRNA function in cell cycle control and apoptosis were drawn, the recombinant virus expressed the BART miRNAs (Figure 1C, red bar) at such low levels in infected LCLs that even previously validated targets could not be confirmed (Seto et al, 2010). Dolken et al (2010) used non-crosslinked Jijoye and B95.8-infected BL cell extracts for Ago co-IPs analysed by microarray (RIP-Chip) to identify human mRNA targets of EBV miRNAs; they validated targets that we confirm (human mRNAs TOMM22 and IPO7), but together identified only 26 host and no viral mRNA targets of the 44 mature EBV miRNAs.

Collective influence of EBV miRNAs

Since EBV miRNAs comprise a significant fraction of miRNAs in Latency III cells (25%; Figure 1B), they are likely to skew overall mRNA targeting by human miRNAs. The major effect is not through direct competition, since only three EBV miRNAs possess seed sequences identical to host miRNAs. However, in EBV-infected cells both a gain of function for the viral miRNAs and a loss of function for the host miRNAs should occur due to limiting RISC protein components (Khan et al, 2009) and binding site occlusion (Chi et al, 2009). In the ‘competing endogenous RNA’ (ceRNA) model, an elaborate regulatory network involving the whole transcriptome would be perturbed since all RNAs with miRNA response elements compete for a limited pool of miRNAs and therefore coordinately influence each others’ activity (Salmena et al, 2011). Thus, EBV miRNAs probably prevent some host miRNA-targeting events that would have occurred in uninfected cells. Deep sequencing of a diverse panel of B-cell types has shown that, while B cells of various origins express a somewhat overlapping subset of ∼300 miRNAs, the relative abundance of each can vary dramatically in different B-cell contexts (Jima et al, 2010). This probably reflects different gene expression programs that modulate the miRNA population by both transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms in B cells that are uninfected or carry EBV in various states of latency.

Other unexpected observations in our data set are as follows. First, Ago binds to select BART pre-miRNAs (Figure 2), but the reason is unknown. Second, the unusual pattern of Ago binding over the entire EBNA2 CDS could represent an unprecedented number of miRNA-binding sites and/or a novel mode of regulation (Figure 2A). Third, we observed a large number of orphan peaks (e.g., LMP1, INPP5D/SHIP1), suggesting novel modes of miRNA–mRNA base-pairing. Exploration of these phenomena could shed additional light on cellular and EBV miRNA function.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

BJAB is an EBV− cell line derived from a BL tumour (Klein et al, 1974). BJAB-B1 is an EBV+ derivative generated by infection of BJAB cells with the P3HR1 EBV (Fresen et al, 1977). B95.8 cells originated from the infection of marmoset B cells with the B95.8 EBV (Miller et al, 1972). Daudi (Klein et al, 1968) and Jijoye (Pulvertaft, 1964) cells are EBV+ cell lines derived from BL tumours. All B-cell lines were maintained in supplemented RPMI (Gibco) as previously published for BJAB cells (Riley et al, 2010). HEK293T cells were grown in DMEM (Gibco) with 10% FBS, penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine.

Constructs

We cloned the full-length 3′UTRs of BHRF1 (NC_009334.1: 42 780–43 413), LMP1 (NC_009334.1: 169 187–167 973), and CAPRIN2 (hg18 chr12: 30 753 754–30 754 102) into the cloning site downstream of firefly luciferase in the pmiRGLO dual-luciferase vector (Promega). PCR primers are in Supplementary Table 4. Mutants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis at the nucleotides indicated in Figures 3, 4, 5. The expression construct for BHRF1 was generated by PCR amplification of nts 41 496–43 413 (NC_009334.1; sequence of EBV type 2 strain AG876) from Jijoye genomic DNA (PCR primers in Supplementary Table 4), which was cloned between HindIII/EcoRI of the pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) MCS behind the CMV promoter. All plasmids were verified by sequencing. Tiny LNAs (Exiqon) were designed as described and dissolved in water (Obad et al, 2011). Synthetic miRNAs (IDT) were synthesized with a 5′-phosphate on the functional strand only and 2-nts 3′ overhangs then annealed according to Tuschl (2006;Supplementary Table 4).

Ago HITS-CLIP and bioinformatics

HITS-CLIP experiments were carried out as described (Chi et al, 2009) for six biological replicates, three each with the mouse monoclonal anti-pan-Argonaute antibody 2A8 (Nelson et al, 2007; a gift from Z Mourleatos) and the rat monoclonal anti-Ago2 antibody 11A9 (Rudel et al, 2008; a gift from G Meister). High-throughput sequencing of seven samples was performed at the Yale Center for Genomic Analysis on an Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx platform. Seed searches were carried out within robust Ago clusters for all miRNA families identified from miRBASE alignments specifying perfect base-pairing for miRNA seeds to targets following 8-mer, 7mer-A1, 7mer-m8, and 6mer(2–7) pairing rules. For a full list of robust miRNA–mRNA pair predictions, refer to Supplementary Table 8. See Supplementary Methods for additional details.

Luciferase assays and statistics

HEK293T cells in 24-well plates were transfected with 1–5 nM tiny LNAs (Obad et al, 2011) or 33 nM synthetic miRNAs and 2.5 ng pmiRGLO reporter plasmid (Supplementary Table 4) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were lysed and the Dual-Luciferase Assay Reporter System (Promega) manufacturer’s protocol was performed 24 h post-transfection. Luciferase activity values were obtained using a Turner Biosystems 20/20n single-tube luminometer. Firefly luciferase activity was first normalized to the control Renilla luciferase activity, and then this ratio was normalized to the control constructs noted for each experiment. At least four independent transfections for each condition were averaged. Excel was used to calculate the standard deviation for each data point, and two-tailed Student’s t-tests were used to compare samples as noted in the figures.

Western and northern blots

HEK293T cells were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), and Jijoye cells were either nucleofected (4D-Nucleofector System, Lonza) or transfected with RNAiMax (Invitrogen) according to manufacturers’ instructions. Protein lysates were prepared from cells, and western blot analyses were performed as described (Wade and Allday, 2000) using NuPAGE 4–12% gels and associated buffers (Invitrogen). Primary antibodies were anti-pan-Ago 2A8 (Nelson et al, 2007; a gift from Z Mourleatos), anti-EBV EA-R-p17 (anti-BHRF1; Millipore), anti-Neomycin Phosphotransferase II (Millipore), anti-alpha tubulin (Sigma), anti-LMP1 (Dako), anti-PARP #9542 (detects full-length and large fragment; Cell Signaling), anti-CAPRIN2 N-19 (Santa Cruz), and anti-GAPDH 14C10 (Cell Signaling Technology). Endogenous CAPRIN2 and BHRF1 were detected using SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Scientific). All other proteins were detected with Western Lightning ECL reagent (PerkinElmer). Northern blotting of total genomic RNA was performed exactly as previously described (Riley et al, 2010; probes in Supplementary Table 4).

Note added in proof

As this paper was going to press, a complementary study of EBV miRNA targets in B95.8-LCLs was published: Skalsky et al, 2012, PLoS Path 8 (1):e1002484 (Epub) Jan 26.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Z Mourleatos (2A8) and G Meister (11A9) for anti-Ago antibodies and E Murphy for plasmid constructs. Thanks to E Guo, N Lee, K Tycowski, and M Xie for critical comments on the manuscript; A Miccinello for editorial work; and all Steitz lab members for quality discussions. KJR was supported by the American Cancer Society New England Division—Beatrice Cuneo Postdoctoral Fellowship. This work was supported in part by grant CA16038 from the NIH. JAS and RBD are investigators of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. The content of this report is solely our responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author contributions: KJR performed all experiments and wrote the manuscript. TAY and GSR helped with experiments. KJR and JML performed bioinformatic analyses. RBD and JAS wrote the manuscript and supervised the work.

Footnotes

The authors delcare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Aerbajinai W, Lee YT, Wojda U, Barr VA, Miller JL (2004) Cloning and characterization of a gene expressed during terminal differentiation that encodes a novel inhibitor of growth. J Biol Chem 279: 1916–1921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia JK, Khan SZ, Soni K, Rawat P, Gupta A, Hariharan M, Scaria V, Lalwani M, Pillai B, Mitra D, Brahmachari SK (2008) Human cellular microRNA hsa-miR-29a interferes with viral nef protein expression and HIV-1 replication. Retrovirology 5: 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mozaini M, Bodelon G, Karstegl CE, Jin B, Al-Ahdal M, Farrell PJ (2009) Epstein-Barr virus BART gene expression. J Gen Virol 90: 307–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altmann M, Hammerschmidt W (2005) Epstein-Barr virus provides a new paradigm: a requirement for the immediate inhibition of apoptosis. PLoS Biol 3: e404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros V (2011) MicroRNAs and developmental timing. Curr Opin Genet Dev 21: 511–517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP (2004) MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116: 281–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth S, Pfuhl T, Mamiani A, Ehses C, Roemer K, Kremmer E, Jaker C, Hock J, Meister G, Grasser FA (2008) Epstein-Barr virus-encoded microRNA miR-BART2 down-regulates the viral DNA polymerase BALF5. Nucleic Acids Res 36: 666–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellare P, Ganem D (2009) Regulation of KSHV lytic switch protein expression by a virus-encoded microRNA: an evolutionary adaptation that fine-tunes lytic reactivation. Cell Host Microbe 6: 570–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentwich I, Avniel A, Karov Y, Aharonov R, Gilad S, Barad O, Barzilai A, Einat P, Einav U, Meiri E, Sharon E, Spector Y, Bentwich Z (2005) Identification of hundreds of conserved and nonconserved human microRNAs. Nat Genet 37: 766–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss IW, Plaisance KB, Renne R (2009) Role of virus-encoded microRNAs in herpesvirus biology. Trends Microbiol 17: 544–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Schafer A, Lu S, Bilello JP, Desrosiers RC, Edwards R, Raab-Traub N, Cullen BR (2006) Epstein-Barr virus microRNAs are evolutionarily conserved and differentially expressed. PLoS Pathog 2: e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesarman E (2011) Gammaherpesvirus and lymphoproliferative disorders in immunocompromised patients. Cancer Lett 305: 163–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SJ, Chen GH, Chen YH, Liu CY, Chang KP, Chang YS, Chen HC (2010) Characterization of Epstein-Barr virus miRNAome in nasopharyngeal carcinoma by deep sequencing. PLoS One 5: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi SW, Zang JB, Mele A, Darnell RB (2009) Argonaute HITS-CLIP decodes microRNA-mRNA interaction maps. Nature 460: 479–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy EY, Siu KL, Kok KH, Lung RW, Tsang CM, To KF, Kwong DL, Tsao SW, Jin DY (2008) An Epstein-Barr virus-encoded microRNA targets PUMA to promote host cell survival. J Exp Med 205: 2551–2560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary ML, Smith SD, Sklar J (1986) Cloning and structural analysis of cDNAs for bcl-2 and a hybrid bcl-2/immunoglobulin transcript resulting from the t(14;18) translocation. Cell 47: 19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuconati A, White E (2002) Viral homologs of BCL-2: role of apoptosis in the regulation of virus infection. Genes Dev 16: 2465–2478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell JC, Van Driesche SJ, Zhang C, Hung KY, Mele A, Fraser CE, Stone EF, Chen C, Fak JJ, Chi SW, Licatalosi DD, Richter JD, Darnell RB (2011) FMRP stalls ribosomal translocation on mRNAs linked to synaptic function and autism. Cell 146: 247–261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell RB (2010) HITS-CLIP: panoramic views of protein–RNA regulation in living cells. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews— RNA 1: 266–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delecluse HJ, Feederle R, O’Sullivan B, Taniere P (2007) Epstein Barr virus-associated tumours: an update for the attention of the working pathologist. J Clin Pathol 60: 1358–1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Leva G, Croce CM (2010) Roles of small RNAs in tumor formation. Trends Mol Med 16: 257–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y, Xi Y, Chen T, Wang JY, Tao DL, Wu ZL, Li YP, Li C, Zeng R, Li L (2008) Caprin-2 enhances canonical Wnt signaling through regulating LRP5/6 phosphorylation. J Cell Biol 182: 865–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan A, Addison C, Gatherer D, Davison AJ, McGeoch DJ (2006) The genome of Epstein-Barr virus type 2 strain AG876. Virology 350: 164–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolken L, Malterer G, Erhard F, Kothe S, Friedel CC, Suffert G, Marcinowski L, Motsch N, Barth S, Beitzinger M, Lieber D, Bailer SM, Hoffmann R, Ruzsics Z, Kremmer E, Pfeffer S, Zimmer R, Koszinowski UH, Grasser F, Meister G et al. (2010) Systematic analysis of viral and cellular microRNA targets in cells latently infected with human gamma-herpesviruses by RISC immunoprecipitation assay. Cell Host Microbe 7: 324–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drexler HG, Minowada J (1998) History and classification of human leukemia-lymphoma cell lines. Leuk Lymphoma 31: 305–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duursma AM, Kedde M, Schrier M, le Sage C, Agami R (2008) miR-148 targets human DNMT3b protein coding region. RNA 14: 872–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eis PS, Tam W, Sun L, Chadburn A, Li Z, Gomez MF, Lund E, Dahlberg JE (2005) Accumulation of miR-155 and BIC RNA in human B cell lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 3627–3632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feederle R, Linnstaedt SD, Bannert H, Lips H, Bencun M, Cullen BR, Delecluse HJ (2011) A Viral microRNA cluster strongly potentiates the transforming properties of a human herpesvirus. PLoS Pathog 7: e1001294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresen KO, Merkt B, Bornkamm GW, Hausen H (1977) Heterogeneity of Epstein-Barr virus originating from P3HR-1 cells. I. Studies on EBNA induction. Int J Cancer 19: 317–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP (2009) Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res 19: 92–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friend K, Campbell Z, Cooke A, Kroll-Conner P, Wickens M, Kimble J (2012) A conserved PUF-Ago-eEF1A complex attenuates translation elongation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19: (2)176–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukayama M (2010) Epstein-Barr virus and gastric carcinoma. Pathol Int 60: 337–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatto G, Rossi A, Rossi D, Kroening S, Bonatti S, Mallardo M (2008) Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 trans-activates miR-155 transcription through the NF-kappaB pathway. Nucleic Acids Res 36: 6608–6619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottwein E, Corcoran DL, Mukherjee N, Skalsky RL, Hafner M, Nusbaum JD, Shamulailatpam P, Love CL, Dave SS, Tuschl T, Ohler U, Cullen BR (2011) Viral microRNA targetome of KSHV-infected primary effusion lymphoma cell lines. Cell Host Microbe 10: 515–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottwein E, Cullen BR (2008) Viral and cellular microRNAs as determinants of viral pathogenesis and immunity. Cell Host Microbe 3: 375–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottwein E, Mukherjee N, Sachse C, Frenzel C, Majoros WH, Chi JT, Braich R, Manoharan M, Soutschek J, Ohler U, Cullen BR (2007) A viral microRNA functions as an orthologue of cellular miR-155. Nature 450: 1096–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey F, Tirabassi R, Meyers H, Wu G, McWeeney S, Hook L, Nelson JA (2010) A viral microRNA down-regulates multiple cell cycle genes through mRNA 5′UTRs. PLoS Pathog 6: e1000967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimson A, Farh KK, Johnston WK, Garrett-Engele P, Lim LP, Bartel DP (2007) MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell 27: 91–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundhoff A, Sullivan CS, Ganem D (2006) A combined computational and microarray-based approach identifies novel microRNAs encoded by human gamma-herpesviruses. RNA 12: 733–750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton O, Phillips LK, Vaysberg M, Hurwich J, Krams SM, Martinez OM (2011) Syk activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt prevents HtrA2-dependent loss of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) to promote survival of Epstein-Barr virus+ (EBV+) B cell lymphomas. J Biol Chem 286: 37368–37378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Thomson JM, Hemann MT, Hernando-Monge E, Mu D, Goodson S, Powers S, Cordon-Cardo C, Lowe SW, Hannon GJ, Hammond SM (2005) A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature 435: 828–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Wang F, Argyris E, Chen K, Liang Z, Tian H, Huang W, Squires K, Verlinghieri G, Zhang H (2007) Cellular microRNAs contribute to HIV-1 latency in resting primary CD4+ T lymphocytes. Nat Med 13: 1241–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA (2009a) Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc 4: 44–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W, Sherman BT, Zheng X, Yang J, Imamichi T, Stephens R, Lempicki RA (2009b) Extracting biological meaning from large gene lists with DAVID. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics Chapter 13: Unit 13 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inomata M, Tagawa H, Guo YM, Kameoka Y, Takahashi N, Sawada K (2009) MicroRNA-17-92 down-regulates expression of distinct targets in different B-cell lymphoma subtypes. Blood 113: 396–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jima DD, Zhang J, Jacobs C, Richards KL, Dunphy CH, Choi WW, Yan Au W, Srivastava G, Czader MB, Rizzieri DA, Lagoo AS, Lugar PL, Mann KP, Flowers CR, Bernal-Mizrachi L, Naresh KN, Evens AM, Gordon LI, Luftig M, Friedman DR et al. (2010) Deep sequencing of the small RNA transcriptome of normal and malignant human B cells identifies hundreds of novel microRNAs. Blood 116: e118–e127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jopling CL, Yi M, Lancaster AM, Lemon SM, Sarnow P (2005) Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA abundance by a liver-specific MicroRNA. Science 309: 1577–1581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly GL, Long HM, Stylianou J, Thomas WA, Leese A, Bell AI, Bornkamm GW, Mautner J, Rickinson AB, Rowe M (2009) An Epstein-Barr virus anti-apoptotic protein constitutively expressed in transformed cells and implicated in burkitt lymphomagenesis: the Wp/BHRF1 link. PLoS Pathog 5: e1000341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AA, Betel D, Miller ML, Sander C, Leslie CS, Marks DS (2009) Transfection of small RNAs globally perturbs gene regulation by endogenous microRNAs. Nat Biotechnol 27: 549–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein E, Klein G, Nadkarni JS, Nadkarni JJ, Wigzell H, Clifford P (1968) Surface IgM-kappa specificity on a Burkitt lymphoma cell in vivo and in derived culture lines. Cancer Res 28: 1300–1310 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein G, Lindahl T, Jondal M, Leibold W, Menezes J, Nilsson K, Sundstrom C (1974) Continuous lymphoid cell lines with characteristics of B cells (bone-marrow-derived), lacking the Epstein-Barr virus genome and derived from three human lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 71: 3283–3286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S (2011) miRBase: integrating microRNA annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 39: D152–D157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutok JL, Wang F (2006) Spectrum of Epstein-Barr virus-associated diseases. Annu Rev Pathol 1: 375–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landgraf P, Rusu M, Sheridan R, Sewer A, Iovino N, Aravin A, Pfeffer S, Rice A, Kamphorst AO, Landthaler M, Lin C, Socci ND, Hermida L, Fulci V, Chiaretti S, Foa R, Schliwka J, Fuchs U, Novosel A, Muller RU et al. (2007) A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA library sequencing. Cell 129: 1401–1414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP (2005) Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell 120: 15–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim LP, Lau NC, Garrett-Engele P, Grimson A, Schelter JM, Castle J, Bartel DP, Linsley PS, Johnson JM (2005) Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature 433: 769–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin HR, Ganem D (2011) Viral microRNA target allows insight into the role of translation in governing microRNA target accessibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 5148–5153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Liang D, He Z, Deng Q, Robertson ES, Lan K (2011) miR-K12-7-5p encoded by Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus stabilizes the latent state by targeting viral ORF50/RTA. PLoS One 6: e16224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnstaedt SD, Gottwein E, Skalsky RL, Luftig MA, Cullen BR (2010) Virally induced cellular microRNA miR-155 plays a key role in B-cell immortalization by Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol 84: 11670–11678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo AK, To KF, Lo KW, Lung RW, Hui JW, Liao G, Hayward SD (2007) Modulation of LMP1 protein expression by EBV-encoded microRNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 16164–16169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F, Stedman W, Yousef M, Renne R, Lieberman PM (2010) Epigenetic regulation of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency by virus-encoded microRNAs that target Rta and the cellular Rbl2-DNMT pathway. J Virol 84: 2697–2706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu F, Weidmer A, Liu CG, Volinia S, Croce CM, Lieberman PM (2008) Epstein-Barr virus-induced miR-155 attenuates NF-kappaB signaling and stabilizes latent virus persistence. J Virol 82: 10436–10443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu JJ, Chen JY, Hsu TY, Yu WC, Su IJ, Yang CS (1996) Induction of apoptosis in epithelial cells by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1. J Gen Virol 77: Pt 81883–1892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lung RW, Tong JH, Sung YM, Leung PS, Ng DC, Chau SL, Chan AW, Ng EK, Lo KW, To KF (2009) Modulation of LMP2A expression by a newly identified Epstein-Barr virus-encoded microRNA miR-BART22. Neoplasia 11: 1174–1184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquitz AR, Mathur A, Nam CS, Raab-Traub N (2011) The Epstein-Barr virus BART microRNAs target the pro-apoptotic protein Bim. Virology 412: 392–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara H, Takeuchi T, Nishikawa E, Yanagisawa K, Hayashita Y, Ebi H, Yamada H, Suzuki M, Nagino M, Nimura Y, Osada H, Takahashi T (2007) Apoptosis induction by antisense oligonucleotides against miR-17-5p and miR-20a in lung cancers overexpressing miR-17-92. Oncogene 26: 6099–6105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middeldorp JM, Pegtel DM (2008) Multiple roles of LMP1 in Epstein-Barr virus induced immune escape. Semin Cancer Biol 18: 388–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G, Shope T, Lisco H, Stitt D, Lipman M (1972) Epstein-Barr virus: transformation, cytopathic changes, and viral antigens in squirrel monkey and marmoset leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 69: 383–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherji S, Ebert MS, Zheng GXY, Tsang JS, Sharp PA, van Oudenaarden A (2011) MicroRNAs can generate thresholds in target gene expression. Nat Genet 43: 854–859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachmani D, Stern-Ginossar N, Sarid R, Mandelboim O (2009) Diverse herpesvirus microRNAs target the stress-induced immune ligand MICB to escape recognition by natural killer cells. Cell Host Microbe 5: 376–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathans R, Chu CY, Serquina AK, Lu CC, Cao H, Rana TM (2009) Cellular microRNA and P bodies modulate host-HIV-1 interactions. Mol Cell 34: 696–709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PT, De Planell-Saguer M, Lamprinaki S, Kiriakidou M, Zhang P, O’Doherty U, Mourelatos Z (2007) A novel monoclonal antibody against human Argonaute proteins reveals unexpected characteristics of miRNAs in human blood cells. RNA 13: 1787–1792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obad S, dos Santos CO, Petri A, Heidenblad M, Broom O, Ruse C, Fu C, Lindow M, Stenvang J, Straarup EM, Hansen HF, Koch T, Pappin D, Hannon GJ, Kauppinen S (2011) Silencing of microRNA families by seed-targeting tiny LNAs. Nat Genet 43: 371–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connell RM, Chaudhuri AA, Rao DS, Baltimore D (2009) Inositol phosphatase SHIP1 is a primary target of miR-155. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 7113–7118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota A, Tagawa H, Karnan S, Tsuzuki S, Karpas A, Kira S, Yoshida Y, Seto M (2004) Identification and characterization of a novel gene, C13orf25, as a target for 13q31-q32 amplification in malignant lymphoma. Cancer Res 64: 3087–3095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SY, Lee JH, Ha M, Nam JW, Kim VN (2009) miR-29 miRNAs activate p53 by targeting p85 alpha and CDC42. Nat Struct Mol Biol 16: 23–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen IM, Cheng G, Wieland S, Volinia S, Croce CM, Chisari FV, David M (2007) Interferon modulation of cellular microRNAs as an antiviral mechanism. Nature 449: 919–922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer S, Zavolan M, Grasser FA, Chien M, Russo JJ, Ju J, John B, Enright AJ, Marks D, Sander C, Tuschl T (2004) Identification of virus-encoded microRNAs. Science 304: 734–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulvertaft JV (1964) Cytology of Burkitt’s tumour (African lymphoma). Lancet 1: 238–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahadiani N, Takakuwa T, Tresnasari K, Morii E, Aozasa K (2008) Latent membrane protein-1 of Epstein-Barr virus induces the expression of B-cell integration cluster, a precursor form of microRNA-155, in B lymphoma cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 377: 579–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley KJ, Rabinowitz GS, Steitz JA (2010) Comprehensive analysis of Rhesus lymphocryptovirus microRNA expression. J Virol 84: 5148–5157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson ES, Tomkinson B, Kieff E (1994) An Epstein-Barr virus with a 58-kilobase-pair deletion that includes BARF0 transforms B lymphocytes in vitro. J Virol 68: 1449–1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A, Vigorito E, Clare S, Warren MV, Couttet P, Soond DR, van Dongen S, Grocock RJ, Das PP, Miska EA, Vetrie D, Okkenhaug K, Enright AJ, Dougan G, Turner M, Bradley A (2007) Requirement of bic/microRNA-155 for normal immune function. Science 316: 608–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe M, Kelly GL, Bell AI, Rickinson AB (2009) Burkitt’s lymphoma: the Rosetta Stone deciphering Epstein-Barr virus biology. Semin Cancer Biol 19: 377–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudel S, Flatley A, Weinmann L, Kremmer E, Meister G (2008) A multifunctional human Argonaute2-specific monoclonal antibody. RNA 14: 1244–1253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmena L, Poliseno L, Tay Y, Kats L, Pandolfi PP (2011) A ceRNA hypothesis: the rosetta stone of a hidden RNA language? Cell 146: 353–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarras H, Alizadeh Azami S, Mc Phers on JP (2010) In search of a function for BCLAF1. ScientificWorldJournal 10: 1450–1461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto E, Moosmann A, Gromminger S, Walz N, Grundhoff A, Hammerschmidt W (2010) Micro RNAs of Epstein-Barr virus promote cell cycle progression and prevent apoptosis of primary human B cells. PLoS Pathog 6: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalsky RL, Samols MA, Plaisance KB, Boss IW, Riva A, Lopez MC, Baker HV, Renne R (2007) Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes an ortholog of miR-155. J Virol 81: 12836–12845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sood P, Krek A, Zavolan M, Macino G, Rajewsky N (2006) Cell-type-specific signatures of microRNAs on target mRNA expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 2746–2751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan GS, Garchow BG, Liu X, Yeung J, JPt Morris, Cuellar TL, McManus MT, Kiriakidou M (2009) Expanded RNA-binding activities of mammalian Argonaute 2. Nucleic Acids Res 37: 7533–7545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Q, Chan AT (2007) Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: molecular pathogenesis and therapeutic developments. Expert Rev Mol Med 9: 1–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas M, Lieberman J, Lal A (2010) Desperately seeking microRNA targets. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 1169–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuschl T (2006) Annealing siRNAs to produce siRNA duplexes. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura A, Young AG, Winslow MM, Lintault L, Meissner A, Erkeland SJ, Newman J, Bronson RT, Crowley D, Stone JR, Jaenisch R, Sharp PA, Jacks T (2008) Targeted deletion reveals essential and overlapping functions of the miR-17 through 92 family of miRNA clusters. Cell 132: 875–886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade M, Allday MJ (2000) Epstein-Barr virus suppresses a G(2)/M checkpoint activated by genotoxins. Mol Cell Biol 20: 1344–1360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walz N, Christalla T, Tessmer U, Grundhoff A (2010) A global analysis of evolutionary conservation among known and predicted gammaherpesvirus microRNAs. J Virol 84: 716–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Tsang SF, Kurilla MG, Cohen JI, Kieff E (1990) Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 transactivates latent membrane protein LMP1. J Virol 64: 3407–3416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinmann L, Hock J, Ivacevic T, Ohrt T, Mutze J, Schwille P, Kremmer E, Benes V, Urlaub H, Meister G (2009) Importin 8 is a gene silencing factor that targets argonaute proteins to distinct mRNAs. Cell 136: 496–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong AM, Kong KL, Tsang JW, Kwong DL, Guan XY (2012) Profiling of Epstein-Barr virus-encoded microRNAs in nasopharyngeal carcinoma reveals potential biomarkers and oncomirs. Cancer 118: 698–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia T, O’Hara A, Araujo I, Barreto J, Carvalho E, Sapucaia JB, Ramos JC, Luz E, Pedroso C, Manrique M, Toomey NL, Brites C, Dittmer DP, Harrington WJ Jr (2008) EBV microRNAs in primary lymphomas and targeting of CXCL-11 by ebv-mir-BHRF1-3. Cancer Res 68: 1436–1442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C, Srinivasan L, Calado DP, Patterson HC, Zhang B, Wang J, Henderson JM, Kutok JL, Rajewsky K (2008) Lymphoproliferative disease and autoimmunity in mice with increased miR-17-92 expression in lymphocytes. Nat Immunol 9: 405–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Q, McBride J, Fewell C, Lacey M, Wang X, Lin Z, Cameron J, Flemington EK (2008) MicroRNA-155 is an Epstein-Barr virus-induced gene that modulates Epstein-Barr virus-regulated gene expression pathways. J Virol 82: 5295–5306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Wang Z, Mertz JE (2007) ZEB1 regulates the latent-lytic switch in infection by Epstein-Barr virus. PLoS Pathog 3: e194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JY, Pfuhl T, Motsch N, Barth S, Nicholls J, Grasser F, Meister G (2009) Identification of novel Epstein-Barr virus microRNA genes from nasopharyngeal carcinomas. J Virol 83: 3333–3341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegelbauer JM (2011) Functions of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus microRNAs. Biochim Biophys Acta 1809: 623–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegelbauer JM, Sullivan CS, Ganem D (2009) Tandem array-based expression screens identify host mRNA targets of virus-encoded microRNAs. Nat Genet 41: 130–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimber-Strobl U, Strobl LJ (2001) EBNA2 and Notch signalling in Epstein-Barr virus mediated immortalization of B lymphocytes. Semin Cancer Biol 11: 423–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.